Abstract

Previous studies have shown that ubiquitination plays important roles in plant abiotic stress responses. In the present study, the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme gene GmUBC2, a homologue of yeast RAD6, was cloned from soybean and functionally characterized. GmUBC2 was expressed in all tissues in soybean and was up-regulated by drought and salt stress. Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GmUBC2 were more tolerant to salinity and drought stresses compared with the control plants. Through expression analyses of putative downstream genes in the transgenic plants, we found that the expression levels of two ion antiporter genes AtNHX1 and AtCLCa, a key gene involved in the biosynthesis of proline, AtP5CS, and the copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase gene AtCCS, were all increased significantly in the transgenic plants. These results suggest that GmUBC2 is involved in the regulation of ion homeostasis, osmolyte synthesis, and oxidative stress responses. Our results also suggest that modulation of the ubiquitination pathway could be an effective means of improving salt and drought tolerance in plants through genetic engineering.

Keywords: GmUBC2, Ubiquitination, Ubiquitin-congugating enzyme, Salt and drought tolerance, Soybean, Stress-responsive genes

Plants are frequently exposed to stressful environmental stimuli, which can have an enormous impact on plant growth and development. Drought or high salinity is responsible for dramatic reductions in crop yield worldwide (Boyer 1982). To adapt to such detrimental conditions, plants have developed a variety of defense strategies, requiring many genes regulated by abiotic stress. Although a large number of genes regulated by salt and drought stress have been identified and their functions have been verified in abiotic stress (Bray 1997; Zhu 2002), the biological functions of many genes related to abiotic stress are still largely unknown in higher plants. Therefore, it is important to study the functions of stress-related genes to improve crop tolerance to salt and drought.

Ubiquitination is an essential process found in all eukaryotic cells, from unicellular yeast to human. The ubiquitination-proteasomal pathway has been implicated in diverse aspects of eukaryotic cellular regulation because of its ability to degrade intracellular proteins (Hershko and Ciechanover 1998; Callis and Vierstra 2000). Ubiquitin (Ub), a small protein with 76 amino acid residues, is one of the most highly conserved proteins known in eukaryotes. Ubiquitination refers to the biochemical process through which Ub is covalently attached to substrate proteins. Ubiquitin binds to the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), which activates Ub and transfers the activated ubiquitin to an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (Ubc or E2) to form an E2-Ub thiolester. The Ub is further transferred to the target protein either alone or in conjunction with an Ub ligase (Ubl or E3). The protein modified by an ubiquitin chain is subsequently degraded by the 26S proteasome. In the ubiquitination system, substrate specificity is mainly determined by E3 together with E2. The ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation pathway is involved in photomorphogenesis, hormone regulation, floral homeosis, senescence, and pathogen defense (Suzuki et al. 2002; Xie et al. 2002; Hellmann and Estelle 2002; Devoto et al. 2003). Previous studies suggest that ubiquitination may also play an important role in plant tolerance against various abiotic stresses. The Arabidopsis gene AtCHIP encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase structurally similar to the animal CHIP proteins, which is up-regulated by several stress conditions such as low and high temperatures. Overexpression of AtCHIP in Arabidopsis confers more sensitivity to both low and high temperatures (Yan et al. 2003). PP2A appears to be ubiquitylated by AtCHIP in vitro and the activity of PP2A is increased in AtCHIP-overexpressing plants in the dark or under low-temperature conditions, suggesting that PP2A might be a substrate of AtCHIP (Luo et al. 2006). Arabidopsis HOS1 encodes a RING finger protein E3 ubiquitin ligase which exerts a negative control on cold response and regulates cold-responsive gene expression (Lee et al. 2001; Ishitani et al. 1998). The RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase SDIR1 is a positive regulator of ABA signaling. Overexpression of SDIR1 leads to ABA hypersensitivity and enhanced drought tolerance through ABA-induced stomatal closure (Zhang et al. 2007). These studies suggest that ubiquitination plays an important role in stress responses in plants.

E2s were originally defined as proteins capable of accepting ubiquitin from an E1 through a thioester linkage via a cysteinyl-sulfhydryl group (Glickman and Ciechanover 2002). The UBC domain also interacts with the E3 enzyme and, in some cases it also interacts with the substrate (Kalchman et al. 1996). Many genes encoding the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme have been identified in eukaryotic organism. The yeast (S. cerevisiae) genome encodes 11 ubiquitin E2s and there are approximately 50 and 37 E2s in the human and Arabidopsis genome, respectively (Bachmair et al. 2001; Jiang and Beaudet 2004; Kraft et al. 2005). The RAD6 gene in S. cerevisiae encodes a 172-amino acid, 20-kDa E2 enzyme (Ubc2) and is required for post-replication repair of UV-damaged DNA, induced mutagenesis, and sporulation (Reynolds et al. 1985). Rad6 appears to have diverse functions since rad6 mutants display a slow-growth phenotype, show defectiveness in DNA damage-induced mutagenesis and are sensitive to killing by various DNA-damaging agents such as UV, ionizing radiations, and alkylating agents. rad6 diploids are also deficient in sporulation (Prakash et al. 1993). Mouse HR6A encodes an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme highly homologous to RAD6 and mHR6A-deficient cells appear to have normal DNA damage resistance properties, but mHR6A knockout male and female mice display a small decrease in body weight (Roest et al. 2004). AtUBC2 of A. thaliana encodes a structural homologue of the RAD6 gene of S. cerevisiae with approximately 65% amino acid identity and it can partially rescue the UV sensitivity and reduced growth rate of rad6 mutants at elevated temperatures (Zwirn et al. 1997). The Atubc1-1 and Atubc2-1 double mutant shows a dramatically reduced number of rosette leaves, an early-flowering phenotype, and reduced transcript levels of a set of floral repressor genes, including Flowering Locus C (FLC), MADS Associated Flowering 4 (MAF4) and MAF5 (Xu et al. 2009).

Although E2s have been studied in regulating various aspects of plant growth, development, and cell process in eukaryotes, little is known about its role in abiotic stress responses. In this study, we identified a soybean gene GmUBC2 encoding an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Expression of GmUBC2 is induced by salt and drought stress. Our molecular and physiological results suggest that GmUBC2 is involved in the regulation of ion homeostasis, osmolyte synthesis, oxidative stress and abiotic stress responses. We demonstrate that overexpression of GmUBC2 in Arabidopsis conferred improved salt and drought tolerance by regulating the expression of a set of important stress-responsive genes.

Materials and methods

Isolation of GmUBC2

Seeds of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) cultivar WF7 were first germinated in vermiculite irrigated with water. After opening of the first trifoliate, the seedlings were transferred into Hoagland’s solution supplemented with 200 mM NaCl for 6 h. Total RNAs were extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). A full-length cDNA homologous to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme was isolated from our salt-induced cDNA library. Specific primers (5′-CATCATTCTCATATCCTCAATC-3′) and (5′-ACCTTGATGAAATCATAACCAG-3′) were synthesized and the full-length cDNA fragment was amplified from the salt-induced first-strand cDNA by RT-PCR. The conditions for amplification were 94°C for 5 min, then 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, followed by incubating at 72°C for 10 min. The amplified fragments were purified and cloned into pMD18-T vector for sequencing.

Localization of the EGFP-GmUBC2 fusion protein

The open reading frame of GmUBC2 was amplified from the cDNA by RT-PCR with the 5′-primer (5′-CGGCGAATTCATGTCGACTCCTGCTAGGAA-3′) and the 3′-primer (5′-GCCGAAGCTTTTAATCTGCTGTCCAACTCTGC-3′), which include an EcoRI and a HindIII restriction site at their 5′ end, respectively. The amplified DNA fragment was cloned into the EcoRI/HindIII sites of the pEGAD vector, to generate EGFP-GmUBC2 fusion gene driven by the 35S cauliflower mosaic virus promoter. The resulting construct was introduced into the A. tumefaciens strain C58C1 and transformed into Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Columbia) plants using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent 1998). Fifteen independent transgenic lines were selected and used to investigate the localization of the fusion protein. Three independent Arabidopsis lines expressing the single EGFP gene under the control of 35S promoter were also examined. EGFP was visualized using a Bio-Rad 1024 confocal scanning head attached to a Nikon (Tokyo, Japan) Optiphot 2 microscope.

Real time RT-PCR analyses

Two micrograms of total RNAs were used to reverse transcribe target sequences using a cDNA synthesis kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Gene-specific primers were designed according to the GmUBC2 cDNA sequence for real time RT-PCRs. The forward primer is 5′-CTCACATCTATCCAGTCATTGCTTT-3′ and the reverse primer is 5′-ACTAAACATTCGAGCTGCTTCA-3′. The soybean Actin gene (GenBank accession no. V00450) was used as an internal control. The Actin gene primers were RA3F (5′-CAGAGAAAGTGCCCAAATCATGT-3′) and RA3R (5′-TTGCATACAAGGAGAGAACAGCTT-3′). The sequences of the primers used for comparing the abiotic stress-responsive gene expression levels between 35S-GmUBC2 line and wild type (WT) plants are given in Table 1. PCRs were performed in the presence of Power SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Amplification was monitored in real time with the Prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). All reactions were performed in triplicate.

Table 1.

Primers used in Real time PCR

| Gene name | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| AtNHX1 | F: 5′-CCGTGCATTACTACTGGAGACAAT-3′ |

| R: 5′-GTACAAAGCCACGACCTCCAA-3′ | |

| SOS1 | F: 5′-TCGTTTCAGCCAAATCAGAAAGT-3′ |

| R: 5′-TTTGCCTTGTGCTGCTTTCC-3′ | |

| AtCLCa | F: 5′-CACAGAGCTCCATGGTCTGA-3′ |

| R: 5′-CCGGTGTGAACTTTTCCCTA-3′ | |

| AtCCS | F: 5′-GCCATGCCTCAGCTTCTTAC-3′ |

| R: 5′-ATTGGACAAATCCACCTCCA-3′ | |

| AtP5CS | F: 5′-GAGGGGGTATGACTGCAAAA-3′ |

| R: 5′-AACAGGAACGCCACCATAAG-3′ | |

| DREB2A | F: 5′-GTGACCTAAATGGCGACGAT-3′ |

| R: 5′-GCGGATCAAAACCACTTTGT-3′ | |

| RD29B | F: 5′-GACAAGGACGCGAAGAAGAC-3′ |

| R: 5′-TCCATCCCAGCTTTTGATTC-3′ |

F forward primer; R reverse primer

Generation of transgenic plants overexpressing GmUBC2

The open reading frame of GmUBC2 was amplified by PCR using 5′-ATCGGGGATCCAATGTCGACTCCTGCTAGGAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGCGAGCTCTTAATCTGCTGTCCAACTCTGC-3′ (reverse) primers containing BamHI and SacI sites, respectively. The resulting product was digested with BamHI and SacI, and inserted into the BamHI/SacI site of the pBI121 vector under the control of 35S promoter. The pBI121-GmUBC2 construct was transferred into A. tumefaciens (strain C58C1) by electroporation. Arabidopsis plants (Col ecotype) were transformed by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent 1998). T1 generation seeds were harvested and screened on MS medium containing 50 mg/L kanamycin. Fifty independent 35S-GmUBC2 transgenic plants were obtained. Fifteen homozygous transgenic lines were selected by screening the transgenic seeds on MS agar plates containing 50 mg/L kanamycin.

Plant materials, growth conditions, and stress tolerance analyses

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col) was used as WT for phenotypic assays of 35S-GmUBC2 plants in all the experiments. Root elongation assay was performed as described (Stone et al. 2006). Briefly, wild-type and transgenic seedlings were germinated and grown vertically on MS plates for 4 days. Seedlings were then transferred to vertical MS plates containing different concentrations of NaCl (0, 100, or 150 mM), and subsequent root growth was measured after 5 days. For the plant survival test, seeds of homozygous transgenic plant were sown on MS agar medium and grew for 5 days, and then transferred to MS agar medium containing 200 mM NaCl and cultured for 7 days. Plants survived were counted.

For the drought tolerance test, 3-week-old WT and 35S-GmUBC2 plants were water withheld for 15 days, after which the plants were re-watered for 1 day. The number of plants that survived 1 day after re-watering was determined. For water-loss analyses, rosette leaves of 5-week-old WT and 35S-GmUBC2 plants were detached and placed abaxial side up in open Petri dishes on the laboratory bench. The leaves were weighed at different times to determine the rate of water loss.

Determination of superoxide dismutase activity, content of proline, Na+, and K+

To determine the Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, 3-week-old WT and transgenic plants were treated with 150 mM NaCl for 0 and 4 days. The rosette leaves were collected and homogenized in 0.05 M Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4 solution (pH 7.8) at 4°C and SOD activity was measured by the nitrio blue tetrazolium (NBT) method. For proline determination, 3-week-old control and transgenic plants were treated with 150 mM NaCl for 0 and 6 h, then the rosette leaves were collected for proline determination. Proline contents were measured as previously described (Bates et al. 1973). For Na+ and K+ determination, 3-week-old control and transgenic plants were treated with 150 mM NaCl for 0 and 6 days and the rosette leaves were collected and dried at 80°C for at least 2 days and weighed. The samples were digested with HNO3, then Na+ and K+ concentrations were determined with an atomic absorption spectrometer (model 3100; Perkin–Elmer, Norwalk, CT). Plant ion content data are presented as averages with standard deviations. Student’s t-test was performed using SAS general linear models (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

GmUBC2 encodes an E2 protein conserved in higher plants

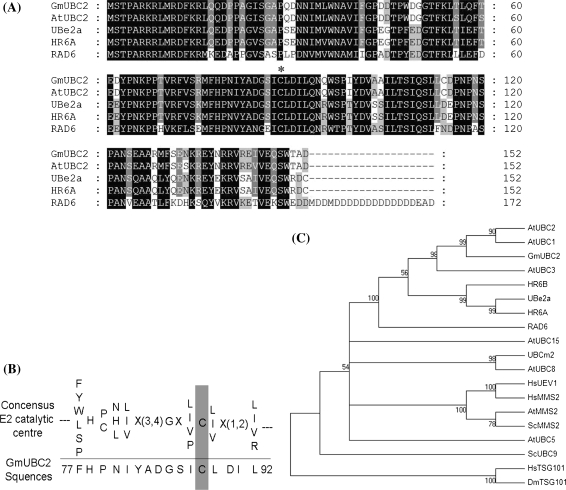

To identify salt stress-related genes in soybean, a full-length cDNA library was constructed from salt-treated soybean cultivar WF7 seedling. A full-length cDNA encoding an Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 was selected for further study. This gene was named GmUBC2 due to its homology to other E2 genes. GmUBC2 encodes a polypeptide of 152 amino acid residues and shares high sequence similarities with AtUBC2 from Arabidopsis (Zwirn et al. 1997), Ube2a from Mus musculus (Roest et al. 2004), RAD6 from S. cerevisiae (Reynolds et al. 1985), and HR6A from Homo sapiens (Koken et al. 1991; Fig. 1a). As predicted by the Scanprosite program, GmUBC2 contains a conserved active-site cysteine required for E2 enzymes catalytic activity (Fig. 1b). Although the cysteine residue of canonical E2 catalytic site is invariant in many E2 enzymes, it is replaced by other amino acid residues in some ubiquitin-conjugating E2 enzyme variant (UEV) proteins (Koonin and Abagyan 1997; Sancho et al. 1998; Thomson et al. 1998). UEV proteins are themselves inactive E2 variant enzymes that appear to function together with bona fide E2 enzymes (Hofmann and Pickart 1999). GmUBC2 is phylogenetically closer to yeast RAD6 and Arabidopsis UBC1/UBC2 than to the TSG101 or MMS2 (UEV1) families of UEVs (Fig. 1c). The results suggest that GmUBC2 likely function as an active ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme homologous to yeast RAD6 and Arabidopsis UBC1/UBC2.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of GmUBC2 and ubiquitin conjugation enzyme E2-related proteins. a Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of soybean GmUBC2 with Arabidopsis AtUBC2 (P42745), Mus musculus Ube2A (NP_062642), Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD6 (AAA34952) and human HR6A (P49459). Fully and partially conserved amino acids were shaded in black and gray, respectively. The asterisk symbol above the alignment denotes the active-site cysteine of E2 enzymes. b Sequence comparison between consensus catalytic sites from UBC (PROSITE: PS000183) and soybean GmUBC2. The catalytic cysteine is highlighted. c Phylogenetic analyses of GmUBC2 and other representative E2-related enzymes. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using CluxtalW and the polygenetic tree was constructed via the Mega 4.1 program. Tree topology was calculated by the neighbor-joining method and 1,000 replicates were used for bootstrap test. The accession numbers for the proteins are given below in parentheses: A. thaliana AtUBC2 (P42745), AtUBC1 (P25865), AtUBC3 (P42746), AtUBC5 (P42749), AtUBC8 (P35131), AtUBC15 (AAC39324), and AtMMS2 (AAK68786); S. cerevisiae RAD6 (AAA34952), ScUBC9 (S52414), and ScMMS2 (AAC24241); M. musculus Ube2A (NP_062642); H. sapiens UbcM2 (AAD40197), HR6A (P49459), HR6B (P63146), HsUEV1 (AAB72016), HsMMS2 (CAA66717), and HsTSG101 (AAC52083); D. melanogaster DmTSG101 (AAG29564)

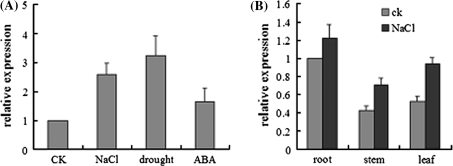

Expression analysis of GmUBC2 in soybean

We performed quantitative RT-PCR analysis to examine the expression levels of GmUBC2 in different tissues of soybean seedlings under abiotic stress conditions. GmUBC2 transcripts increased in soybean seedlings treated with a solution containing 200 mM NaCl, 20% PEG, or 100 μM ABA for 6 h (Fig. 2a). The GmUBC2 transcripts were detected in leaves, stems and roots of soybean plants without stress treatments, but the level of transcript was more abundant in roots than in stems and leaves (Fig. 2b). After the 6 h of treatment with 200 mM NaCl, the mRNA level of GmUBC2 is about twofold higher in stems and leaves than that in the control, but the level in roots only slightly increased (Fig. 2b). These results suggest that the expression of GmUBC2 is responsive to salt, osmotic stress, and exogenous ABA treatments.

Fig. 2.

Expression of GmUBC2 is regulated by salt, drought and ABA treatments. The seeds were first germinated in vermiculite irrigated with water. After opening of the first trifoliate, the seedlings were transferred into Hoagland’s solution supplemented with 200 mM NaCl, 20% polyethylene glycol (PEG), or 100 μM ABA for 6 h. Seedlings, roots, stems and leaves were collected for total RNA extraction and real time RT-PCR analysis. a GmUBC2 is response to NaCl, drought, and exogenous ABA treatments. b GmUBC2 is up-regulated in different organs under NaCl stress. The soybean actin gene was used as an internal control. Ck, untreated control. Error bars represent SD (n = 3)

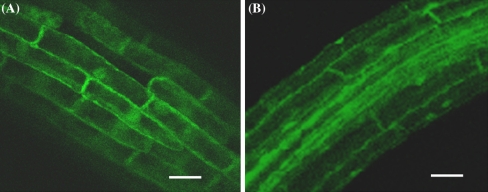

Localization of the GmUBC2 protein in plant cells

To investigate the localization of GmUBC2 in cells, the full-length coding region of GmUBC2 was fused with EGFP. Stable transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing EGFP-GmUBC2 fusion protein were generated and the subcellular localization of the fusion protein was visualized by confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3, green fluorescence was found in both the cytosol and nucleus in root cells of transgenic plants expressing EGFP-GmUBC2, which was similar to that of transgenic seedlings expressing EGFP alone. This observation suggests that GmUBC2 is localized in both the cytosol and nucleus in plant cells.

Fig. 3.

Subcellular localization of EGFP-GmUBC2 fusion protein in transgenic Arabidopsis root cells. a Localization of the EGFP protein. b Localization of EGFP-GmUBC2 protein. Scale bar, 20 μm

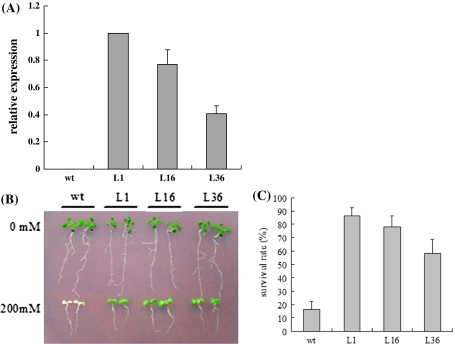

Overexpression of GmUBC2 confers enhanced salt tolerance in Arabidopsis

To examine the in vivo function of GmUBC2, transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GmUBC2 were generated. Three homozygous transgenic lines were selected for functional analysis. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that the GmUBC2 mRNA accumulated in all three 35S-GmUBC2 transgenic lines, but not in WT plants (Fig. 4a). The growth of transgenic plants was compared with that of the WT plants 2 weeks after sowing. The 35S-GmUBC2 plants grown on MS agar plates or in soil showed a phenotype similar to that of the WT plants. No morphological changes were observed in 35S-GmUBC2 plants grown either on MS agar or in soil.

Fig. 4.

Overexpression of the GmUBC2 in Arabidopsis confers improved NaCl tolerance. a The GmUBC2 transcript levels in WT and three transgenic lines (L1, L16, and L36) were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. The Arabidopsis Actin gene was used as an internal control. b 5-day-old homozygous seedlings were transferred from normal MS media to MS media supplemented with 0 mM or 200 mM NaCl for 7 days. c Survival rates of WT plants and transgenic plants under 200 mM NaCl treatment for 7 days

To evaluate the effect of GmUBC2 overexpressing on salt tolerance, 5-day-old seedlings grown on MS agar plate were kept on MS agar plate or transferred to MS agar plate supplemented with 200 mM NaCl. No significant difference was observed for transgenic seedlings grew on MS agar plate without NaCl, compared to WT plants (Fig. 4b). However, in MS media containing 200 mM NaCl, the control plants displayed growth inhibition and bleached gradually (Fig. 4a). Only 16.67% of control plants survived. However, the transgenic plants overexpressing GmUBC2 showed better growth than WT plants. The survival rates for transgenic line L1, L16 and L36 were 86.67, 78.33 and 58.18%, respectively (Fig. 4c).

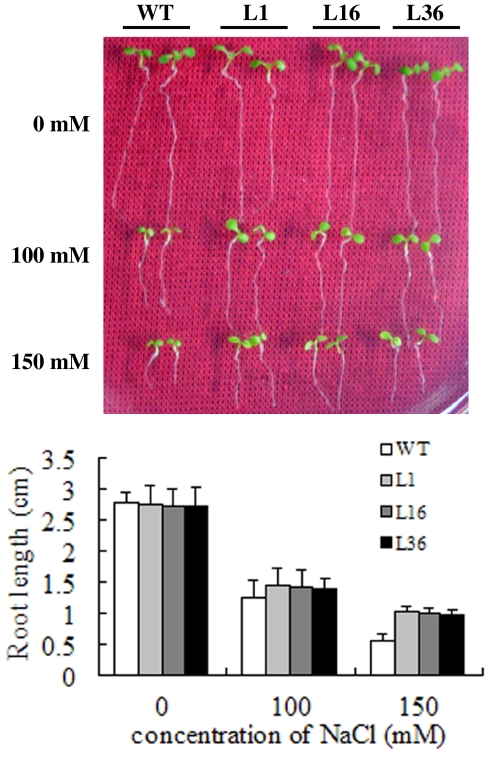

To determine whether the transgenic plants overexpressing GmUBC2 have enhanced salt tolerance for postgerminative seedling growth, 4-day-old seedlings grown on MS medium were transferred to medium containing different concentration of NaCl for 5 days. When the seedlings were growth in the medium without NaCl, the root length of transgenic seedlings did not show significant difference from WT plants. In contrast, root growth of both transgenic seedlings and WT seedlings was inhibited under NaCl stress, but root length of transgenic seedlings were significantly longer than that that of WT seedlings (Fig. 5). For example, in the medium containing 150 mM NaCl, the root length of the three transgenic lines L1, L16 and L36 were 1.02, 0.99, and 0.96 cm respectively, whereas the root length of the WT plants only reached 0.55 cm.

Fig. 5.

Seedling growth of GmUBC2 transgenic plants under different concentration levels of NaCl. 4-day-old WT and 35S-GmUBC2 seedlings grown on MS medium were transferred to MS medium supplemented with 1% sucrose containing 0, 100 and 150 mM NaCl for 5 days. The graph shows root length after 5 days under different levels of NaCl for WT and transgenic seedlings (n = 15)

Overexpression of the GmUBC2 confers enhanced drought tolerance in Arabidopsis

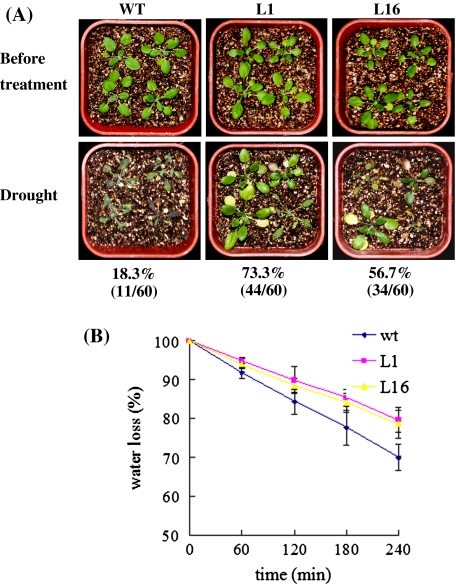

To evaluate the drought stress tolerance of 35S-GmUBC2 plants, 3-week-old WT and 35S-GmUBC2 plants grew in soil were withheld from water for 15 days. After resumption of watering for 1 day, 73.3 and 56.7% of transgenic lines L1 and L16 survived, whereas only 18.3% of WT plants recovered (Fig. 6a). We also quantified the loss of fresh weight (FW) in detached leaves. The leaves from WT plants lost about 30% of their FW in 4 h, while leaves from 35S-GmUBC2 plants had a much reduced water loss (approximately 20%) (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Drought tolerance of the 35S-GmUBC2 transgenic plants. a Three-week-old plants were grown in soil in the same container withheld from water for 15 days and then re-watered. The photographs were taken 1 day after re-watering. Percentages of surviving plants and numbers of surviving plants per total number of tested plants are indicated under the photographs. b Quantification of water loss in 3-week-old WT, L1 and L16 transgenic plants. Leaves of the same developmental stages were excised and weighed at various time points after detachment. Data represent average values ± SD (n = 8)

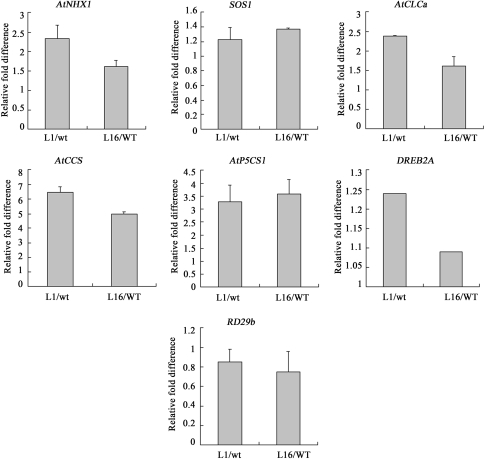

The expression of stress responsive genes in 35S-GmUBC2 plants

To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the enhanced tolerance to salt and drought by 35S-GmUBC2 plants, we examined transcript levels of a set of selected abiotic stress-responsive genes in WT and 35S-GmUBC2 plants grew under normal conditions by real time PCR. Because plants reestablish ion homeostasis under salt stress, several genes modulating ion homeostasis were selected. As shown in Fig. 7, expression of several genes were elevated in the 35S-GmUBC2 transgenic plants compared to wild type plants, including the vacuolar antiporter gene AtNHX1, AtCLCa gene encoding a NO3 −/H+ exchanger (Angeli et al. 2006), AtP5CS1 encoding a rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of Proline and AtCCS encoding a copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase(Strizhov et al. 1997; Chu et al. 2005). However, the levels of SOS1 encoding a plasma membrane antiporter (Shi et al. 2002) and the stress-responsive transcription factor DREB2A and its target genes RD29b appear to be insensitive to GmUBC2 abundance under normal growth conditions (Sakuma et al. 2006).

Fig. 7.

Expression of stress-responsive genes in 35S-GmUBC2 lines. Relative RNA levels of stress-responsive genes were determined by Real time PCR using total RNAs isolated from the shoots of 3-week-old plants grown under normal conditions in soil. Two independent assays were performed and similar results were obtained (each n = 3). The Arabidopsis ACT3 (ATU39480) gene was used as a loading control

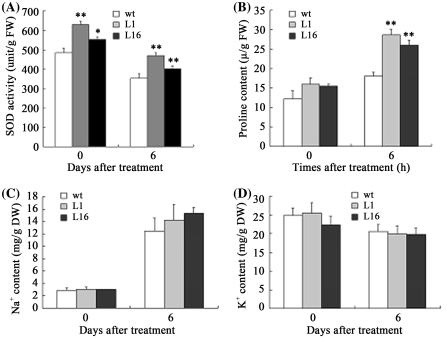

35S-GmUBC2 plants exhibit enhanced SOD activity, proline and Na+ content, but not K+ content

Because the transcripts of P5CS and AtCCS genes increased in transgenic plants overexpressing GmUBC2, we determined the SOD activity and proline content in rosette leaves of WT and transgenic plants. Without NaCl treatment, the SOD activity in L1 and L16 plants was 29.8 and 14.0%, respectively, higher than that in WT plants. After 4 days of 150 mM NaCl treatment, the SOD activity in L1 and L16 plants was 32.2 and 13.3% higher, respectively, than that in WT plants (Fig. 8a). The proline content in L1 and L16 plants was relatively higher than that of control plants without NaCl treatment. After 6 h of 150 mM NaCl treatment, the proline contents in both L1 and L16 plants and control plants increased, but the proline content in L1 and L16 were 58.7 and 44.0% higher, respectively, than that in control plants (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

Measurement of SOD activities, proline contents, and ion contents in wild type (WT) and two transgenic lines (L1 and L16) overexpressing GmUBC2. (A and B) SOD activity (a) and proline content (b) in WT and two transgenic lines (L1 and L16) overexpressing GmUBC2 grown at various salt concentrations. Na+ (C) and K+ (D) contents of WT and transgenic plants (n = 3). DW, dry weight. FW, fresh weight. Asterisks represent significant differences between the WT and transgenic plants (** and * represent P < 0.01 and P < 0.05 respectively, Student’s t test)

Because the AtNHX1 gene expression is affected in 35S-GmUBC2 plants under normal growth conditions, we determined the Na+ and K+ contents of the rosette leaves of WT and transgenic plants grown under control and high-NaCl conditions. Under normal growth conditions, the Na+ contents in both L1 and L16 lines was similar to that in control plants. However, the Na+ contents of both L1 and L16 plants and control plants dramatically increased under 150 mM NaCl treatment for 6 days, and a higher Na+ content in the transgenic plants was observed (Fig. 8c). The K+ contents in both L1 and L16 and control plants decreased slightly after 150 mM NaCl treatment for 6 days, but there was no significant difference between plants with or without NaCl treatment (Fig. 8d). These results suggest that the improved salt tolerance of 35S-GmUBC2 plants could be partially due to increased compartmentation of Na+ into the tonoplast.

Discussion

In this study, we identified a soybean ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme gene, GmUBC2, which contains a conserved consensus E2 catalytic site with an invariant active-site cysteine of E2 enzymes (Fig. 1b). Previous phylogenetic analyses of UBC proteins in Arabidopsis, S. cerevisiae, and H. sapiens have classified AtUBC1 and AtUBC2 as well as AtUBC3 together with RAD6 (also named ScUBC2) and HsUBC2 as members of group III (Kraft et al. 2005). GmUBC2 has high sequence similarity to AtUBC2 and RAD6 and phylogenetically clusters together with AtUBC2 and RAD6. These sequence analyses suggest that GmUBC2 could be an active ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme as RAD6 and AtUBC2, further biochemical analysis is needed to further confirm whether GmUBC2 binds ubiquitin via a thiol ester linkage. Previous studies have demonstrated that AtUBC1 and AtUBC2 have E2 activity in vitro (Sullivan and Vierstra 1993), that AtUBC2 could rescue the UV-sensitive phenotype of the yeast rad6 mutant (Zwirn et al. 1997), and that AtUBC1 and AtUBC2 have redundant functions in suppression of flowering (Xu et al. 2009). Here, we showed that GmUBC2 played an important role in salt and drought stress responses by regulating stress-responsive genes.

Accumulating evidences suggest that ubiquitination may play an important role in plant tolerance against abiotic stresses (Yan et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2001; Lopez-Molina et al. 2003; Luo et al. 2006; Stone et al. 2006). The mRNA level of GmUBC2 increased after exposure to salt and drought stress, suggesting that GmUBC2 might be involved in plant tolerance against salt and drought stress. As a prove-of-concept study, we overexpressed the GmUBC2 under the control of 35S CaMV promoter to examine its role in salt and drought stress in Arabidopsis given the technical difficulty of transforming soybean. The transgenic Arabidopsis plants were more tolerant to NaCl during the seedling stage. As shown in Fig. 4, seedlings expressing GmUBC2 grew in MS medium containing 200 mM NaCl for 7 days exhibited higher survival rates compared with the control plants. The root length of transgenic seedlings is longer than that of WT seedlings (Fig. 5). In addition, our data indicated that plants overexpressing GmUBC2 were more tolerant to drought compared to control plants (Fig. 6). These results strongly suggest that GmUBC2 is a positive regulator of salt and drought tolerance.

Our gene expression analysis suggests that GmUBC2 is involved in the regulation of ion homeostasis, osmolyte synthesis, and oxidative stress responses. We found that expression of several abiotic stress-related genes increased in the GmUBC2 overexpressing plants under normal growth conditions. Among them, the Na+/H+ antiporter AtNHX1 is a vacuolar antiporter (Gaxiola et al. 1999) and represents a mechanism of sequestering Na+ into vacuoles to adapt to higher NaCl condition in plants (Apse et al. 1999). We also found that the Na+ content in transgenic plants is higher than that in control plants. Consistent with our observation, overexpressing plants of AtNHX1 or a rice vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter exhibited higher vacuolar antiport activity and Na+ content than WT plants under high NaCl condition (Apse et al. 1999; Fukuda et al. 2004). Our result strongly suggests that GmUBC2 enhances salt tolerance by affecting AtNHX1 expression to sequester Na+ in plants. In addition, we observed an increased expression of the anion channel gene AtCLCa in the 35S-GmUBC2 plants. The tonoplast-localized AtCLCa is able to accumulate specific nitrate in the vacuole and behaves as a NO3 −/H+ exchanger (Angeli et al. 2006). Together, our results suggested that GmUBC2 is involved in regulation of ion homeostasis in plant cells.

Salt and drought stress leads to accumulation of high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Borsani et al. 2001). The excessive production of ROS such as superoxide (O2 −), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH−) may disturb cellular redox homeostasis, leading to oxidative injuries. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) belongs to the enzymatic defense system against ROS and catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals to molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. The increased expression level of AtCCS suggests that SOD activity may increase in 35S-GmUBC2 plants. Indeed, we observed a higher SOD activity in transgenic plants compared with control plants with or without NaCl treatment (Fig. 8), suggesting that GmUBC2 regulates SOD activity to scavenge ROS and is involved in oxidative stress responses.

Proline is one of the osmoprotecting molecules (osmolytes), which accumulates in plants in response to water stress and salinity. Correlations between proline accumulation and osmotic stress responses indicate that proline also plays a role as osmoprotectant in higher plants (Yoshiba et al. 1995; Martinez et al. 1995). Interestingly, we found that the expression levels of P5CS1 increased significantly in 35S-GmUBC2 plants compared to WT plants. P5CS1 encodes a rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of Pro (Strizhov et al. 1997). Consistent with this, the level of proline content was higher in the 35S-GmUBC2 transgenic plants under stress-growing conditions. Our results suggest that GmUBC2 may play an important role in the synthesis of osmolytes to protect plants from water deficit.

Many abiotic-stress-inducible genes are controlled by ABA, but some are not, which indicates that both ABA-dependent and ABA-independent regulatory systems are involved in stress-responsive gene expression. The ABA-dependent signaling pathway is mediated mainly by two types of transcription factors: one is ABRE-binding factors (ABFs); the other is the transcription factor AtMYC, which activates the expression of RD22 genes (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki 2005). Although the P5CS1 gene responsive to salinity, drought, and ABA was affected in 35S-GmUBC2 transgenic plants, the expressions of ABF3, ABF4 and AtMYC2, and some of their target genes (such as RD22), were not affected in 35S-GmUBC2 plants (data not shown). A substantial number of studies have reported that overexpression of genes in the ABA signal pathway such as ABF3, ABF4, AtMYC2 and SDIR1, confer several ABA- or stress-associated phenotypes in transgenic plants, such as ABA hypersensitivity, sugar hypersensitivity, salt sensitivity and enhanced drought tolerance (Kang et al. 2002; Abe et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2007). However, 35S-GmUBC2 transgenic plants were insensitive to various ABA concentrations (data not shown) and had enhanced tolerance to salt stress at seedling stages (Figs. 4, 5). In addition, two genes of ABA-independent signaling pathway regulated by DREB2A, Rd29b, and DREB2A (Sakuma et al. 2006), showed no significant changes in 35S-GmUBC2 plants. Therefore, our results suggest that GmUBC2 could be involved in ABA-independent signaling pathway in the response to dehydration stress. However, it is also possible that the expressed levels of GmUBC2 in 35S-GmUBC2 lines might not be enough to trigger the expression of various ABA-responsive genes even though GmUBC2 could be involved in ABA-dependent pathway. Further studies are required to definitely resolve this issue.

In conclusion, our molecular and physiological data suggest that GmUBC2 may act as an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme to regulate protein degradation and abiotic stress responses. Identification and functional characterization of the substrate proteins will aid in the elucidation of the regulatory mechanisms of ubiquitination-proteasome pathway in abiotic stress responses in plants.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the State High-tech (863) (No.2006AA100104, No.2006AA10B1Z3, No.2006AA10Z1F1); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.30490251, No.30671310, No.30490250 and No.30471096), the State Key Basic Research and Development Plan of China (973) (No.2004CB117203), National Key Technologies R&D Program in the 11th Five-Year Plan (No.2006BAD13B05). We thank Professor Shouyi Chen at Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of Chinese Academy of Sciences in China for the technical assistance during analysis of stress-responsive gene expression in transgenic plants. We also thank Dr. Haiyang Wang (Cornell University) for critical reading and commenting on the manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Guo-An Zhou, Email: guoanzhou2001@yahoo.com.cn.

Li-Juan Qiu, Phone: +86-01082105843, FAX: +86-01082105840, Email: qiu_lijuan@263.net, Email: qiu_lijuan@mail.caas.net.cn.

References

- Abe H, Urao T, Ito T, et al. ArabidopsisAtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) function as transcriptional activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 2003;15:63–78. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angeli A, Monachell D, Ephritikhine G, et al. The nitrate/proton antiporter AtCLCa mediates nitrate accumulation in plant vacuoles. Nature. 2006;442:939–942. doi: 10.1038/nature05013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apse MP, Aharon GS, Snedden WA, et al. Salt tolerance conferred by overexpression of a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter in Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;285:1256–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmair A, Novatchkova M, Potuschak T, et al. Ubiquitylation in plants: a post-genomic look at a post-translational modification. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:463–470. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)02080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39:205–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00018060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borsani O, Valpuesta V, Botella MA. Evidence for a role of salicylic acid in the oxidative damage generated by NaCl and osmotic stress in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:1024–1030. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.3.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer JS. Plant productivity and environment. Science. 1982;218:443–448. doi: 10.1126/science.218.4571.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray EA. Plant responses to water deficit. Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:48–54. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(97)82562-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Callis J, Vierstra RD. Protein degradation in signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2000;3:381–386. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00100-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CC, Lee WC, Guo WY, et al. A copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase that confers three types of copper/zinc superoxide dismutase activity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:425–436. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.065284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto A, Muskett PR, Shirasu K. Role of ubiquitination in the regulation of plant defense against pathogens. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:307–311. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda A, Nakamura A, Tagin A, et al. Function, intracellular localization and the importance in salt tolerance of a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter from rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:146–159. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaxiola RA, Rao R, Sherman A, et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana proton transporters, AtNhx1 and Avp1, can function in cation detoxification in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1480–1485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman MH, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin–proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:373–428. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann H, Estelle M. Plant development: Regulation by protein degradation. Science. 2002;297:793–797. doi: 10.1126/science.1072831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann RM, Pickart CM. Noncanonical MMS2-encoded ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme functions in assembly of novel polyubiquitin chains for DNA repair. Cell. 1999;96:645–653. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80575-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani M, Xiong L, Lee H, et al. HOS1, a genetic locus involved in cold-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1151–1162. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.7.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang YH, Beaudet AL. Human disorders of ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16:419–426. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000133634.79661.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalchman MA, Graham RK, Xia G, et al. Huntingtin is ubiquitinated and interacts with a specific ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19385–19394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JY, Choi H, Im M, et al. Arabidopsis basic leucine zipper proteins that mediate stress-responsive abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 2002;14:343–357. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koken M, Reynolds P, Jaspers-Dekker I, et al. Structural and functional conservation of two human homologs of the yeast DNA repair gene RAD6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8865–8869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV, Abagyan RA. TSG101 may be the prototype of a class of dominant negative ubiquitin regulators. Nat Genet. 1997;16:330–331. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft E, Stone SL, Ma L, et al. Genome analysis and functional characterization of the E2 and RING-type E3 ligase ubiquitination enzymes of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1597–1611. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.067983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Xiong L, Gong Z. The ArabidopsisHOS1 gene negatively regulates cold signal transduction and encodes a RING finger protein that displays cold-regulated nucleo-cytoplasmic partitioning. Genes Dev. 2001;15:912–924. doi: 10.1101/gad.866801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Molina L, Mongrand S, Kinoshita N, et al. AFP is a novel negative regulator of ABA signaling that promotes ABI5 protein degradation. Genes Dev. 2003;17:410–418. doi: 10.1101/gad.1055803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Shen G, Yan J, et al. AtCHIP functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase of protein phosphatase 2A subunits and alters plant response to abscisic acid treatment. Plant J. 2006;46:649–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CA, Maestri M, Lani EG. In vitro salt tolerance and praline accumulation in Andean potato (Solanum spp.) differing in frost tolerance. Plant Sci. 1995;116:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(96)04374-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S, Sung P, Prakash L. DNA repair genes and proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Genet. 1993;27:33–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds P, Weber S, Prakash L. RAD6 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a protein containing a tract of 13 consecutive aspartates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:168–172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roest HP, Baarends WM, Wit J, et al. The ubiquitin-conjugating DNA repair enzyme HR6A is a maternal factor essential for early embryonic development in Mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5485–5495. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5485-5495.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y, Maruyama K, Osakabe Y, et al. Functional analysis of an Arabidopsis transcription factor, DREB2A, involved in drought-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1292–1309. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho E, Vila MR, Sanchez-Pulido L, et al. Role of UEV-1, an inactive variant of the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, in vitro differentiation and cell cycle behavior of HT-29–M6 intestinal mucosecretory cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:576–589. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Quintero FJ, Pardo JM, Zhu JK. The putative plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter SOS1 controls long-distance Na+ transport in plants. Plant Cell. 2002;14:465–477. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone SL, Williams LA, Farmer LM, et al. Keep on going, a RING E3 ligase essential for Arabidopsis growth and development, is involved in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3415–3428. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strizhov N, Abraham E, Okresz L, et al. Differential expression of two P5CS genes controlling proline accumulation during salt stress requires ABA and is regulated by ABA1, ABI1 and AXR2 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1997;12:557–569. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan ML, Vierstra RD. Formation of a stable adduct between ubiquitin and the Arabidopsis ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, AtUBC1. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8777–8780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki G, Yanagawa Y, Kwok SF, et al. Arabidopsis COP10 is a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme variant that acts together with COP1 and the COP9 signalosome in repressing photomorphogenesis. Genes Dev. 2002;16:554–559. doi: 10.1101/gad.964602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson TM, Khalid H, Lozano JJ, et al. Role of UEV-1A, a homologue of the tumor suppressor protein TSG101, in protection from DNA damage. FEBS Lett. 1998;423:49–52. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00060-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q, Guo HS, Dallman G, et al. SINAT5 promotes ubiquitin-related degradation of NAC1 to attenuate auxin signals. Nature. 2002;419:167–170. doi: 10.1038/nature00998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Menard R, Berr A. The E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, AtUBC1 and AtUBC2, play redundant roles and are involved in activation of FLC expression and repression of flowering in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2009;57:279–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Organization of cis-acting regulatory elements in osmotic- and cold-stress-responsive promoters. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Wang J, Li Q, et al. AtCHIP, a U-box-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase, plays a critical role in temperature stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:861–869. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.020800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiba Y, Klyosue T, Katagiri T, et al. Correlation between the induction of a gene for Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase and the accumulation of praline in Arabidopsis thaliana under osmotic stress. Plant J. 1995;7:751–760. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.07050751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yang C, Li Y, et al. SDIR1 is a RING finger E3 ligase that positively regulates stress-responsive abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:1912–1929. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwirn P, Stary S, Luschnig C, et al. Arabidopsis thalianaRAD6 homolog AtUBC2 complements UV sensitivity, but not N-end rule degradation deficiency, of Saccharomyces cerevisiae rad6 mutants. Curr Genet. 1997;32:309–314. doi: 10.1007/s002940050282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]