Abstract

Objective

To review which domains somatically ill persons nominate as constituting their QoL. Specific objective is to examine whether the method of enquiry affect these domains.

Methods

We conducted two literature searches in the databases PubMed/Medline, CINAHL and Psychinfo for qualitative studies examining patients’ self-defined QoL domains using (1) SEIQoL and (2) study-specific questions. For each database, two researchers independently assessed the eligibility of the retrieved abstracts and three researchers subsequently classified all QoL domains.

Results

Thirty-six eligible papers were identified: 27 studies using the SEIQoL, and nine presenting data derived from study-specific questions. The influence of the method of enquiry on patients’ self-nominated QoL domains appears limited: most domains were presented in both types of studies, albeit with different frequencies.

Conclusions

This review provides a comprehensive overview of somatically ill persons’ self-nominated QoL domains. However, limitations inherent to reviewing qualitative studies (e.g., the varying level of abstraction of patients’ self-defined QoL domains), limitations of the included studies and limitations inherent to the review process, hinder cross-study comparisons. Therefore, we provide guidelines to address shortcomings of qualitative reports amenable to improvement and to stimulate further improvement of conducting and reporting qualitative research aimed at exploring respondents’ self-nominated QoL domains.

Keywords: Quality of life, SEIQoL, Review, Individualized measures, Cancer

Introduction

It has long been understood that somatic illnesses and their treatment may have a considerable influence on patients’ health-related quality of life (QoL). Since the 1980s a range of generic and disease-specific QoL measures have been developed in efforts to gain an understanding of this influence [1]. Consequently, patient-reported QoL measures have increasingly been included in randomized clinical trials to demonstrate the effect of treatment beyond clinical efficacy and safety [2].

The majority of these QoL questionnaires are based on domains formulated by researchers and health policy makers [3]. However, a repeated finding is that externally defined domains may not reflect the domains that patients consider relevant for their QoL [e.g., 4–6]. For example, Morris et al. [4] compared the health-related QoL domains identified by patients undergoing major surgery with seven commonly used HRQoL instruments. While the domains’ ‘concern about quality of care’, ‘cognitive preparation’ and ‘spiritual wellbeing’ were frequently mentioned as constituting patients’ QoL, these were not assessed by most of the instruments.

While the usefulness of standardized QoL questionnaires has been repeatedly demonstrated and is beyond doubt, we lack a comprehensive overview of QoL domains that patients themselves nominate as constituting their QoL. Such insight is needed to ensure that the relevant domains are addressed and to guide questionnaire selection. We therefore undertook a literature review of qualitative studies that asked patients to identify domains constituting their QoL. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to provide a comprehensive overview of patients’ self-nominated QoL domains.

Two types of studies are relevant for this review. First, studies using the Schedule for Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life (SEIQoL) [7, 8] are relevant, as they make the perspective of the individual central to defining relevant QoL domains. This widely used individualized measure [9] requires that patients nominate five domains they consider most relevant to their QoL. When patients have difficulty nominating five domains, a prompt list can be used consisting of the cues: family, relationships, health, finances, living conditions, work, social life, leisure activities and religion/spiritual life [10]. The SEIQoL generates an overall index score that is the result of the individual’s rating of his/her functioning in and importance of each self-nominated QoL domain. The SEIQoL thus provides a wealth of qualitative data about the content of the nominated domains, although most studies only report the quantitative results related to the overall index scores. We specifically excluded individualized measures that did not directly ask for life domains relevant for patients’ QoL. For example, the Patient-Generated Index (PGI) [11] was excluded because it asks patients to nominate the five most important areas of life or activities that are affected by their condition as was Cantrill’s ladder [12] that asks patients to describe their worst imaginable and best imaginable life satisfaction. Individualized measures such as the Audit of Diabetes-Dependent Quality of Life (ADDQoL) [13] and the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQoL) [14] were excluded, since they only allow for individual weighting of predefined QoL domains. All of these measures thus have a slightly different scope than that in the current review.

A second cluster of studies is also relevant; these explore somatically ill patients’ self-generated QoL domains to evaluate the content validity of existing, standardized QoL questionnaires or to improve the quality of care. The interview question(s) used to elicit patients’ self-defined QoL domains vary per study, e.g., respondents are explicitly asked what their personal perception of quality of life is, how they would describe quality of life, or what the term quality of life means to them. To differentiate these studies from those using the SEIQoL, we refer to this group of studies as those using study-specific questions.

This review thus includes studies reporting qualitative data originating from the use of the SEIQoL and from studies employing study-specific questions. The domains that patients report and/or researchers aggregate and present may be influenced by several factors. We will address one of these in examining whether the method of enquiry is related to generation of different domains. The use of the SEIQoL prompt list is likely to result in the presentation of QoL domains similar to the prompt list, whereas the use of study-specific questions may result in different QoL domains. We therefore compare the QoL domains presented in studies using the SEIQoL with those in studies using study-specific questions (Appendix 2).

Methods

Literature searches

We conducted two systematic literature searches in the databases PubMed/Medline, CINAHL and PsychInfo for papers published from 1980 on using (1) SEIQoL and (2) study-specific quality-of-life questions. We conducted consecutive literature searches employing the following search terms: SEIQoL, SEIQoL-DW and patient(s) as search terms (literature search 1) and quality of life, QoL, content, definition, item generation, content generation and patient(s) (literature search 2). The literature searches were initiated in March 2007, and updated until March 2008.

Study selection

Two researchers independently assessed the eligibility of all abstracts retrieved by our literature searches in PubMed/Medline and PsychInfo (ETB, MK) and CINAHL (ETB, MV). The researchers involved discussed their findings, and decided on each abstract’s eligibility based on mutual consensus. All studies included in this review met the following criteria: (1) The study presents QoL domains qualitatively generated by respondents residing in Anglo-Saxon (i.e., English speaking) or non-English speaking European countries, which are somatically ill (in contrast to having a psychiatric illness) or have symptoms as the result of their illness at the time of study. (2) The study was published in English between 1980 and September 2008 in an internationally peer-reviewed journal. In addition, the studies met the following methodological quality criteria: (3) The formulation of the interview question(s) is provided. (4) The original data are sufficiently presented to demonstrate the relation between the data and the researchers’ interpretation, i.e., via patients’ quotations or detailed categorization schemes. (5) In studies using multiple assessment points, QoL domains nominated at one separate assessment point are discernible. (6) In studies using study-specific questions, data-analysis is carried out inductively, i.e., without a pre-determined framework for the categorization of nominated QoL domains. In case of multiple publications based on the same patient sample, we only included the paper with the most comprehensive presentation of the qualitative data. Due to the different nature of psychiatric illnesses as opposed to somatic illnesses, and its potential implications for patients’ self-defined QoL domains, we only included studies conducted among somatically ill patients. Reviews and case studies were also excluded.

Categorization of QoL domains

Three researchers (ETB, MS, MV) classified all QoL domains presented in the selected papers in two steps based on mutual consensus. First, most studies reporting data originating from the SEIQoL categorized the self-nominated domains according to the nine domains included in the prompt list. We therefore initially used these same nine domains (e.g., family) or closely related QoL domains (e.g., family-related) for categorization (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Categorization of QoL domains included in and highly related to the SEIQoL prompt list

| QoL domains included in SEIQoL prompt list | QoL domains related to SEIQoL prompt list | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Family-related | ||

| SEIQoL | Study-specific question | SEIQoL | Study-specific question |

| Family [7, 8, 15–17, 19, 21, 23, 26, 28, 29, 31–36, 39, 41–45] | Family [48, 53] | Family life [24] | Family life [55] |

| Contact with my grandchildren [18]; Ability to enjoy my family [18]; Maintaining good contacts with family [38] | Associate with family [50]; Relationships with relatives/family [52] | ||

| Children [8, 15, 22, 29, 35, 45]; My children [18]; Grandchildren [18, 22, 42]; Becoming a granny [18]; Parent [22]; Family tree [22]; Family not directly related [18] | |||

| Good care for family [38] | |||

| Support from my family [18] | |||

| Relationships | Relationships-related | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SEIQoL | Study-specific question | SEIQoL | Study-specific question |

| Relationships [7, 34–36, 44] | Friends [8, 15, 17, 18, 22–24, 26, 28, 29, 39, 41–44]; Friendship [34, 45]; Relations [18]; Specific relationships [44]; Relations to other people [16]; Social contacts [18, 45]; Ability to enjoy other relations [18]; Maintaining good contacts with others [38]; Neighbors [17, 26]; Contacts in my living environment [18] | Associate with friends [50]; Friends [53]; Social network [46]; Essential networks [47]; Relationships that work [48]; Relationships with other people-general [52] | |

| Support from my colleagues [18] | Support [51]; Needing of support/understanding [52]; Social support/functional services [53]; Supportive relations [56] | ||

| Marriage [17, 23, 24, 28, 32, 34, 35, 41, 44]; Spouse [8, 22, 43]; Partner [8, 42, 43, 45]; Wife [15]; My wife [18]; My husband [18]; Relation to partner [16]; Relationship with a partner [21]; Relationship with spouse [26]; Partnership [39, 41]; Lover [8] | |||

| Spousal welfare/health [17]; Loss of spouse [17]; Dealing with the loss of relative or spouse [38] | |||

| To sort things out with my wife [18] | |||

| Love [26] | |||

| Carer [26] | |||

| Grow closer/more distant through crisis [51] | |||

| Making others happy [56] | |||

| Health | Health-related | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SEIQoL | Study-specific question | SEIQoL | Study-specific question |

| Health [7, 8, 15, 17–19, 21, 23, 24, 26, 28, 32–35, 38, 39, 41, 42, 44] | Health [50, 53] | Personal health [36, 43]; Own health [45] | My own health [52]; Own health [55] |

| Physical limitations [16]; Feeling physically well [18]; Being able to do what I want to do [18]; Feeling good [18]; Physical ability [24]; Physical functioning [38] | Physical well-being [47]; Physical functioning [51]; Physical capacity [48] | ||

| Fatigue/loss of energy [16]; Fatigue [18]; Physical fitness [22]; Energy [22] | Feel fit and rested [46]; Not experiencing fatigue [50]; Physical condition [51]; Feeling strong [56] | ||

| Pain [15]; Pain free [34] | No pain [46]; Freedom from pain [48]; Not experiencing pain in the abdomen [50]; Feeling no pain [56] | ||

| Drugs/access to Physeptone [8]; Pain control [22]; Symptom control [35] | Personal strategies to relieve pain [47] | ||

| Urinary symptoms [15]; Diet [15]; ALS-related [31] | Get rid of bowel symptoms [46]; Not having diarrhea [50]; Eat everything [51]; Good appetite [50]: Find explanation for bowel symptoms [46]; Knowledge about IBS [46] | ||

| Health in general [16] | |||

| Activity [21]; Physical activity [35]; Being physically active [38] | |||

| Walking [15]; Walking/mobility/getting around [17]; Mobility [22, 24, 26, 28, 34, 38]; Being mobile [18] | |||

| To be cured [18]; Becoming healthier [18]; Not to get too ill [18]; Disease progression [29]; Reversal of illness [38] | |||

| Functioning—senses [38] | |||

| Family health [36]; Health of partner [45] | |||

| Feeling healthy [56] | |||

| Healthy way of living [52] | |||

| Wellness [53] | |||

| Living longer [55] | |||

| Pain-positive effect [56] | |||

| Finances | Finances-related | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SEIQoL | Study-specific question | SEIQoL | Study-specific question |

| Finances [8, 16, 17, 22–24, 29, 31, 32, 34–36, 38, 39, 41, 43, 44] | Financial security [21, 28] | Financial security [55]; Good economics [46]; Economic security [48]; Financial welfare [52]; Sufficient income [53] | |

| Money [8, 17, 26, 42]; Finance [15]; Financial affairs [7] | |||

| Not being restricted in budget to enjoy life [18]; Financial resources [33] | |||

| Keeping control of my finances [18] | |||

| My wife’s budget after my death [18] | |||

| Living conditions | Living conditions-related | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SEIQoL | Study-specific question | SEIQoL | Study-specific question |

| Living conditions [7, 8, 17, 18, 35, 36, 44] | House [17, 42]; Housing [15, 16, 38]; Home [15, 17, 18, 23, 24, 26, 28]; Home/dwelling [43]; Home life/environment [32]; Having somewhere to live/a home [8]; Housing conditions [18]; Good living conditions [38]; Living environment [24] | House/home/living environment [53] | |

| Improving surroundings [56] | |||

| Work | Work-related | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SEIQoL | Study-specific question | SEIQoL | Study-specific question |

| Work [7, 8, 15–19, 22, 23, 26, 29, 32–36, 39, 42–45] | Work [53] | Business [18]; Employment [28]; Occupation [31, 41]; Profession [41] | Good work [46]; Employment [48]; Work and pursue daily activities [50] |

| Being able to get to work [8] | Ability to do what one wants to do/work [55]; Able to work [56] | ||

| Dealing with issues at work [38] | Conditions at work/job satisfaction [52] | ||

| Own shop [18]; Moving firm [18]; Working in alternative medicine [18]; My work as baby-sit [18] | |||

| Working as a volunteer at the cemetery [18]; Work-related activity since retirement [32] | |||

| Social life | Social life-related | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SEIQoL | Study-specific question | SEIQoL | Study-specific question |

| Social life [8, 17, 18, 24, 28, 31–35, 41] | Social life [55] | Communication [39] | Resonance in communication [47]; Social intercourse [48]; Communication [51]; Communicating [56] |

| Social activities [26, 34, 36, 44]; Club life [18] | |||

| Social [19] | |||

| Community [15]; Helping community [35] | |||

| Leisure activities | Leisure activities-related | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SEIQoL | Study-specific question | SEIQoL | Study-specific question |

| Leisure activities [17, 18, 26, 33, 35, 36, 43] | Leisure activities [55] | Hobby [21]; Hobbies [17, 26, 31, 32, 38, 41, 44, 45]; Leisure activity [24]; Leisure [7, 8, 15, 16, 19, 23, 28, 32, 44]; Activities (recreation) [29]; Recreation [22, 44]; Pastime [38]; Pastimes [41]; Leisure time [39] | Hobbies/cultural activities [53]; Leisure time [48]; Active leisure time [46]; Pursue hobbies/leisure time activities [50] |

| Food [28, 32, 42] | Good food/eating [56] | ||

| Exercise [22, 32]; Sports [8, 18, 43, 45]; Sport [42]; Sport/fitness [28]; Sports/motion [39]; Football [18] | |||

| Gardening [15, 22, 28]; Garden [18, 39, 42]; My garden [18]; Sewing [18, 22]; Music [17, 28, 42]; Playing cards and fishing [18]; Computer [22]; Television [42]; Art [22]; Reading [39, 42]; Bingo [42]; Photography [42]; Craft [42] | |||

| Pet [22]; Pets [15, 18, 26, 28, 32, 42]; Animals [42] | |||

| Getting out [17]; Going out everywhere [18]; Going out [42]; Holidays [15, 17, 23, 32, 42, 45]; Having a holiday [18]; Travel [22, 32]; Driving [17]; Car [42]; Transportation [45]; Caravan [42] | |||

| Fun [22] | |||

| Religion/spiritual life | Religion/spiritual life-related | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SEIQoL | Study-specific question | SEIQoL | Study-specific question |

| Religion [15, 17, 22, 23, 26, 28, 29, 34–36, 38, 39, 41] | Religion [52] | Faith [17]; Belief [22]; Religious aspects of life [7]; Religious life [44] | |

| Spiritual life [17, 31, 34, 41, 44] | Spiritual life [52] | Spirituality [8, 39]; Spiritual [19, 35] | Spirituality [51] |

| Church [17, 42] | |||

| Existential well-being, facing death [51] | |||

| Spiritual support [56] | |||

| Confirmation [46] | |||

Second, two researchers (ETB, MV) independently classified the QoL domains that could not be grouped according to the SEIQoL prompt list domains, into new domains. They discussed the formulation of the domains and the classification with MS until consensus was reached. This iterative process resulted in eight additional domains; psychological functioning, coping/positive attitude, independence, role functioning, feeling of self, cognitive functioning, quality of care, sexuality, and a miscellaneous category (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Categorization of QoL domains according to additional, inductively generated domains

| Inductively derived QoL domains | |

|---|---|

| SEIQoL | Study-specific question |

| Psychological functioning | |

| Emotional well-being [8]; Psychosocial impact [16]; Mental well-being [44] | Psychological well-being [47, 48]; Psychological state [51]; Psychological well-being-general [52]; Sense of well-being [46] |

| Happiness [7, 17, 18, 34, 36, 42] | Happiness [55]; Feeling happy/happiness [56] |

| Contentment [17, 23, 34] | Contentment [48]; Feeling satisfied [56] |

| Freedom [18]; Freedom/relaxation/harmony [39]; Relaxation [45] | Experienced freedom [48] |

| Emotional issues [16]; Feelings [45] | |

| Psychological [19] | |

| Good mood [46] | |

| Feel relaxed [46]; Feeling calm and relaxed [52]; Inner peace [56] | |

| Being without anxiety [46]; No stress [46]; Stress and anxiety [52] | |

| Feeling secure [56] | |

| Coping/positive attitude | |

| Sense of control [8] | Command of life [46]; To be in charge of the situation [47]; Uncertainty/control [51] |

| Positive thinking [18]; Positivity [22]; Awareness/positivity [28] | Optimism/pessimism [52]; Positive mental attitude [56] |

| Hope [22, 42] | Hope [51]; Feeling hopeful [52] |

| That a cure is found for the virus/AIDS [8] | Hoping in science [52] |

| Future [17] | Make future plans [52] |

| To enjoy life [18] | Being able to find some joy in life [51]; Being able to enjoy things [52]; Enjoyment of life [55]; Enjoying life [56] |

| Putting everything into perspective [18] | |

| Coping [51]; Coping strategies [52]; Adapting/adjusting [56] | |

| Independence | |

| Independence [7, 8, 17, 19, 21, 23, 24, 28, 31, 32, 35, 36, 42, 43, 45]; Being independent [18, 38]; Being physically and mentally independent [18]; Self-sufficiency [33]; Autonomy [21] | Independence [53]; Physical independence [48]; Feeling independent [56]; Autonomy (physical and psychological) [52] |

| Hospitalization/dependence [16]; Dependence [29] | |

| Choice [8] | |

| Do it yourself [42] | |

| My car, my freedom [18] | |

| Continuing my former independent life [18] | |

| Being a burden [51] | |

| Role functioning | |

| Daily living [15]; Getting back to my former daily routine [18]; Household [39]; Daily hassles [44]; Activities of daily life [45] | Appreciation of normal things [47]; Having a normal life [56] |

| Feeling functional [47]; Functional status [52]; Feeling of being needed [47] | |

| Change in role [51]; Fulfilling one’s role [56] | |

| Feeling of self | |

| Personal achievement [44] | Attain goals [46] |

| Self acceptance [8]; Self esteem [8] | Self-perception [52]; Integrity/identity [53]; Live one’s life in accordance with one’s desire [50] |

| Feeling wanted [8] | |

| View of life and oneself [16] | |

| Feeling successful [56] | |

| Good appearance [50]; Body image [52] | |

| Cognitive functioning | |

| Intellectual function [36] | Cognitive capacity [48]; Cognitive functioning [51] |

| Feeling mentally well [18]; Mental health [23]; Mental functioning [38] | |

| Able to concentrate [56] | |

| Quality of care | |

| Quality of care and attention [38]; Being treated honestly and sincerely [38] | |

| Support from healthcare professionals [46]; Feeling cared for/treated with respect [51]; Relationships with health care team (trust, esteem, support) [52]; Continuity of care/staff [51]; Availability/acceptance of limitations of health care staff [51]; Feeling secure/vulnerable (quality of palliative care) [51]; Health care professionals’ skills [52]; Spiritual care [51]; Health care institutions general organization [52]; Health care institutions physical environment [52] | |

| Sexuality | |

| Sex [8, 26, 42]; Sexuality [8, 21]; Sex life [44]; Sexual ability [15] | |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Enjoying pleasant memories [38]; Reminiscence [42] | Keeping memories alive [47] |

| Nature [22, 39] | Outdoors (access to nature, weather) [51]; Environment [52] |

| Time left [8]; Issues to be faced [8]; Having things sorted out before I die [8] | |

| Educational aspects of life [7]; Education [43] | |

| Time all to yourself [18]; Doing something on my own [18] | |

| A quiet and peaceful well-organized life [18] | |

| Norms and values in society [18] | |

| Miscellaneous [8, 16, 23, 31, 32, 36, 41, 43]/Other [39, 45] | |

| Chance and fortune [52] | |

| Taking care of one’s needs [52] | |

| To be reflective [47] | |

| Right place to be: home/hospital [51]; Indoors (does/does not meet psychosocial/physical/functional needs) [51] | |

In order to classify all QoL domains according to the afore-mentioned categorization scheme, we had to tease apart the QoL domains originally presented in 22 papers [8, 17, 18, 24, 26, 28, 29, 32, 34, 36, 38, 39, 41, 43–45, 48, 50–53, 55]. For example, we have separated the single QoL domain family/friends presented in a study by Archenholtz et al. [53] into two QoL domains: family (according to the SEIQoL prompt list) and friends (related to the SEIQoL prompt list cue relationships).

Additionally, we only classified the QoL domains that were presented at the lowest level of abstraction in the articles, since these are closest to the patients’ own definition of QoL. This meant that in 12 papers [8, 16, 18, 22, 38, 46–52, 56] we ignored the overarching themes that authors used to group the self-nominated QoL domains. For example, Cohen and Leis [51] classified the QoL domains ‘physical condition’, ‘physical functioning’, ‘psychological state’ and ‘cognitive functioning’ into the overarching theme ‘own state’. We used the four QoL domains for classification rather than the more abstract construction ‘own state’.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

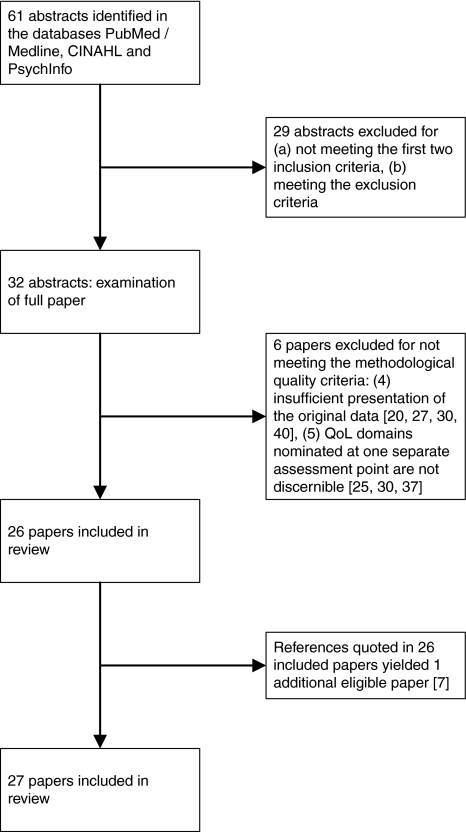

The literature search for papers using SEIQoL resulted in 61 abstracts (see Fig. 1). Twenty-nine abstracts were excluded based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented earlier. The remaining 32 papers [8, 15–45] were examined with regard to our methodological quality criteria, resulting in the further exclusion of six papers [20, 25, 27, 30, 37, 40]. Examination of the references included in the 26 selected papers resulted in one additional paper eligible for this review [7]. Literature search 1 thereby resulted in 27 eligible papers.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the selection of eligible papers resulting from literature search 1 (studies using the SEIQoL)

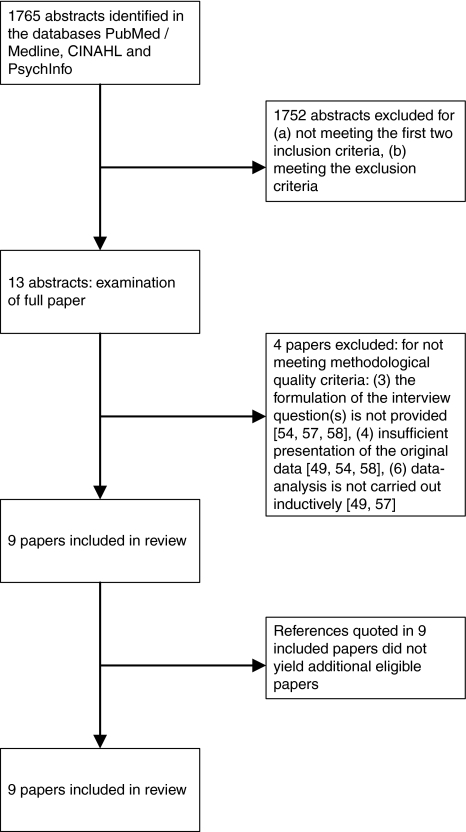

The literature search for papers using study-specific questions yielded a total of 1,765 abstracts (Fig. 2). From these studies, 1,752 were excluded based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The remaining 13 papers [46–58] were examined with regard to our methodological quality criteria, which led to the further exclusion of four papers [49, 54, 57, 58]. Additionally, all references quoted in the selected nine papers were examined for eligibility, which did not lead to the inclusion of new papers. Overall, the literature searches yielded a total of 36 eligible papers [27 papers (literature search 1) + 9 papers (literature search 2)] (See Tables 5 and 6 in the Appendices for a summary of the design and results of the included papers).

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of the selection of eligible papers resulting from literature search 2 (studies using study-specific questions)

Table 5.

Summary of eligible papers derived from literature search 1—studies using SEIQoL

| Reference paper | Country | Objective | Sample | Design | Description of 1st step | Qualitative analysis | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McGee et al. [7] | Ireland | To apply the SEIQoL to a patient population and to provide information regarding the impact of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and peptic ulcer disease (PUD) on an individual measure of QoL |

N = 20 IBS patients N = 20 PUD patients Mean age 35 years (range 17–65) Forty-two consecutive patients at a gastro-intestinal clinic with either IBS or PUD were asked to participate |

SEIQoL Face-to-face interview administered at the hospital T1 |

Nomination of the five areas of life considered most important by each subject in assessing his/her overall QoL |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

Nominated cues (not ranked in any order): Leisure Family Work Relationships Happiness Independence Financial affairs Living conditions Health Educational aspects of life Religious aspects of life |

| Hickey et al. [8] | Ireland | To describe the first clinical application of the SEIQoL-DW, assessing the QoL of a cohort of patients with HIV/AIDS managed in general practice |

N = 52 patients known to be HIV positive Mean/median age: not specified Cohort of patients with HIV/AIDS who were being managed in general practice, primarily recruited through two Dublin inner city general practices and receiving some form of ambulatory care. |

SEIQoL-DW Place where the face-to-face interview was administered: not specified T1 |

What are the five most important aspects of your life at the moment? |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 4 individual patient profiles |

Domains nominated as important to overall QoL (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Health Family Money, finances Drugs, access to physeptone Children Spouse or partner Friends, social life Psychological factors: emotional well-being; sense of control; self acceptance; self esteem; feeling wanted Independence, choice Issues relating to death: time left; issues to be faced; having things sorted out before I die; that a cure is found for the virus/AIDS Living conditions Spirituality Sports, leisure Work Having somewhere to live, a home Sex, lover, sexuality Being able to get to work Miscellaneous |

| Pearcy et al. [15] | UK | To assess the ability of clinicians and partners to make proxy judgments on behalf of patients with prostate cancer relating to selection of life priorities and QoL |

N = 25 newly diagnosed patients with adenocarcinoma and partners N = 18 newly diagnosed patients with adenocarcinoma and physicians (same patients) Mean/median age: not specified 47 consecutive newly diagnosed patients with histologically proven adenocarcinoma were recruited. All stages and proposed treatments were included. |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interview administered at the hospital Participants additionally administered the Functional Assessment of Cancer-Therapy-Prostate (FACT-P) questionnaire and an overall QoL score using a VAS T1 |

Nomination of the five most important areas of life that were central to the patient’s QoL |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

Cues nominated more than once (not ranked in any order): Pets Urinary symptoms Pain Diet Housing Religion Children Community Holidays Walking Home Daily living Finance Work Friends Gardening Health Leisure Wife Family Sexual ability |

| Wettergren et al. [16] | Sweden | To prospectively measure QoL in patients with malignant blood disorders following stem cell transplantation (SCT) |

22 patients with malignant blood disorders Median age: 50 years (range 31–66) During a 2-year period patients listed for autologous SCT at two university hospitals in Stockholm were asked to participate in the study. |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interview administered at the hospital Participants additionally administered a disease-related version of the SEIQoL-DW and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) T1–T2 |

If you think about your life as a whole, what are the most important things in your life at present—both good and bad- that are crucial for your QoL? |

One of the authors carried out the analysis of the transcripts. The list of categorized statements was read by one of the co-authors. The two researchers achieved mutual consensus. The list of domains previously obtained in long-term survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma was used as an initial framework for categorization [65] Illustration of findings with individual statements |

Domains nominated as important in life at T1 (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Health in general Relations to other people Health concerns/problems: fatigue/loss of energy; physical limitations; psychosocial impact Work Leisure Housing Relation to partner Finances Emotional issues View of life and oneself Hospitalization/dependence Miscellaneous |

| Lee et al. [17] | UK | To compare the PDQ-39 with the SEIQoL-DW in patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD) |

N = 123 IPD patients Median age 75,4 years (range 51–89) Eligible patients were included if they were under the care of the Parkinson’s disease service in North Tyneside on 31 December 2003 |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interview administered at the patient’s home Participants additionally administered the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39), the Mini Mental State examination, Beck Depression Inventory, a qualitative pain assessment and the Palliative care assessment tool T1 |

Nomination of five life areas or cues that are important to the patient |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

The authors selected the 21 most mentioned domains out of a total of 87 domains mentioned (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Health Leisure activities/ hobbies Marriage Friends Independence Walking/mobility/getting around Getting out Home/house/living conditions Social life Money/finances Happiness/contentment Faith/church/religion/spiritual life Holidays Future Work Spousal welfare/health Music Loss of spouse Neighbors Driving |

| Westerman et al. [18] | The Netherlands | To examine how patients choose and define the five areas they consider important for their quality of life and to describe the problems in the elicitation of cues |

N = 31 patients diagnosed with small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) Mean/median age: not specified. (range 39–82) Consecutive sample of SCLC patients, beginning their first-line chemotherapy, were recruited from five outpatient clinics for chest diseases in The Netherlands. |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interviews. All but two interviews were administered at the patient’s home Participants additionally administered the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) and it’s lung cancer module (QLQ-CL13) T1 |

Nomination of five areas of life that the individual considers to be important for his/her overall QoL |

Information on the analysis of the interviews to investigate the administration process. Illustration of findings with individual interview extracts |

Domains considered to be important for patient’s overall QoL (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family (my husband; my wife; my children, becoming a granny, grandchildren; contact with my grandchildren; support from my family; to sort things out with my wife; ability to enjoy my family and other relations) Health (fatigue; health; to be cured; feeling physically and mentally well; being able to do what I want to do; becoming healthier; feeling good; not to get too ill; being mobile; getting back to my former daily routine) Social life (social contacts; social life; contacts in my living environment; friends; relations; support from my colleagues; club life; family not directly related) Leisure (leisure activities; sports; football; playing cards and fishing; sewing; my garden; working as a volunteer at the cemetery) Enjoying life (having a holiday; to enjoy life; time all to yourself; freedom and happiness; going out everywhere) Living conditions (living conditions; home, garden and pets; housing conditions; a quiet and peaceful well-organized life; norms and values in society) Autonomy (being independent; my car, my freedom; being physically and mentally independent; doing something on my own; continuing my former independent life) Work (own shop; moving firm; business; work; working in alternative medicine; my work as baby-sit) Finance (keeping control of my finances; my wife’s budget after my death; not being restricted in budget to enjoy life) Attitudes toward life (positive thinking; putting everything into perspective) |

| Sharpe et al. [19] | Australia | To investigate the relationship between response shift and adjustment |

N = 56 patients with metastatic cancer Mean age 64 years (range 46–82) Consecutive patients who had been diagnosed with metastatic cancer within the last 3 months and being treated with palliative intent were recruited from three Medical Oncology Departments in Sydney, Australia |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interview administered at the patient’s home Participants additionally administered the Functional assessment for Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) T1–T3 |

Nomination of five most important domains that a subject indentifies as contributing to his/her QoL |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

Domains mentioned as the most important contributor to QoL at T1 (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Health Family Independence Social Leisure Psychological Work Spiritual |

| Willener and Hantikainen [21] | Switzerland | To examine the individual QoL of men following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer |

N = 11 men with prostate cancer who had undergone a radical prostatectomy 3–4 months earlier Mean age 66 years (range 58–70) Purposive sample |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interview administered at the hospital T1 |

Nomination of five areas of life which are most important to the patient’s overall QoL |

Categorization of QoL areas by 2 researchers Illustration of findings with 3 individual patient profiles Findings illustrated with patients’ quotes |

55 QL areas are grouped into 9 categories (not ranked in any order): Only the 3 categories considered the most impact on QoL are divided in subthemes: Health (e.g. inner peace resulting from the certainty that you are no longer ill; certainty that health will remain stable; getting rid of the uncertainty about the cancer) Activity Family (e.g. good understanding with children; (grand)children; wife) Relationship with a partner (harmony with wife; relationship with wife; not living alone) Autonomy Independence Hobby Financial security Sexuality |

| Carlson et al. [22] | Canada | To investigate individualized QoL of patients participating in a Phase 1 trial of the novel therapeutic reovirus (Reolysin) |

N = 16 patients with incurable metastatic cancer Median age 53 years (range 32–76) Sample: not specified. Patients were recruited according to the protocol of the Phase 1 trial. |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interview administered at the hospital Participants additionally administered the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30), the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Spiritual Health Inventory (SHI) and a semi-structured expectations interview T1 |

Nomination of five most important domains of QoL |

Only areas identified by all 16 patients are presented in a table. No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 2 individual patient profiles |

Domains nominated (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family (children, spouse, grandchildren, parent, family tree) Activities (exercise, gardening, sewing, recreation, travel) Friends Health (mobility, physical fitness, energy) Faith (religion, belief, hope) Work Finances Pet Computer Pain control Art Fun Positivity Nature |

| Gribbin et al. [23] | UK | To assess the effect of pacemaker mode on individualized QoL by comparing an individualized evaluation with a generic health index and disease specific symptom scale |

N = 73 patients randomized to VVI(R) or atrial-based pacing modes Mean age 76 years (range 55–88) All patients recruited to either of two multi-centre pacemaker trials between January 1997 and May 1999 were invited to participate |

SEIQoL Face-to-face interview administered at the hospital Participants additionally administered the 36-item Medical Outcomes Study Short-form General Health Survey (SF36) and a modified version of the Karolinska Cardiovascular Symptomatology Questionnaire (KCSQ) T1–T4 |

Nomination of five domains of life which are considered to be most important |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

Domains nominated at T1; grouped into broader categories (in descending percentage of the total number of cues nominated at T1): Leisure Family Health Friends Marriage Finances Home Miscellaneous Independence Religion Holidays Work Mental health Contentment |

| Levack et al. [24] | UK | To report QoL of patients shortly after the diagnosis of malignant cord compression (MCC), its relation to physical ability and to emotional well-being |

N = 180 patients diagnosed with MCC Mean/median age: not specified Patients diagnosed with MCC at any of three oncology centers in Scotland between 1 January 1998 and 14 April 1999 were recruited to the Scottish Spinal Cord Compression Audit. Following diagnosis, patients were asked whether they would be willing to participate in the interview component of the study. |

SEIQoL-DW Place where the face-to-face interview was administered: not specified Participants additionally administered the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) T1–T5 |

Nomination of five areas of life which contribute most to their QoL |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 1 individual patient profile |

Domains nominated at T1 (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family life Leisure activity Health Marriage Social life Friends Home/living environment Mobility/physical ability Independence Finances |

| Mountain et al. [26] | UK | To examine whether the current disease-based clerking could be supplemented in older people with QoL information |

N = 60 subjects subjects ≥ 65 years acutely admitted to a Medicine for the Elderly service Mean age 81 years (range 65–95) Study population was drawn from a cohort of patients admitted non-electively to an assessment ward in a Department of Medicine for the elderly |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interview administered at the Department of Medicine for the elderly Participants additionally administered the 36-item Medical Outcomes Study Short-form General Health Survey (SF36), the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Controlled Oral Word Association (COWA) T1 |

Nomination of five life areas that subjects consider important in determining their QoL |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

Domains nominated as important to the patients’ QoL (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Health Hobbies/leisure activities Home Money Relationship with spouse Friends Work Religion Mobility Social activities Neighbors Pets, sex, love, carer |

| Montgomery et al. [28] | UK | To evaluate the clinical usefulness of the SEIQoL-DW to quantify the impact on patients living with a diagnosis of lymphoma or leukemia |

N = 51 patients with lymphoma and leukemia Mean age 54 years (range not specified) A sample of 57 in-patients and out-patients in the hematology department at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital were approached during a 4 month period in 1998. |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interview was administered at the hospital Patients additionally administered the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) T1 |

Nomination of five areas of life which are most important to the subject’s overall QoL |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 2 individual patient profiles |

Important life areas nominated (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Friends Health Leisure Home Marriage Employment Financial security Mobility/independence Awareness/positivity Sport/fitness Religion Social life Gardening Music Pets Food |

| Bromberg and Forshew [29] | USA | To compare the SEIQoL-DW, ALSFRS and SIP/ALS-19 instruments in patients with ALS |

N = 25 ALS patients Mean age 56 years (range 43–76) 25 consecutive patients with definite or probable ALS |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interview was administered at the hospital Patients additionally administered the ALS Functioning Rating Scale (ALS-FRS) and the ALS-related subset of the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP/ALS19) T1 |

What are the five most important aspects of your life at this moment? |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

Domains nominated as most important to QoL (in descending order of number of occurrences): Activities (recreation) Finances Dependence Family and children Friends Disease progression Work Religion |

| Clarke et al. [31] | Ireland | To assess the internal consistency reliability and validity of the SEIQoL, to provide a brief description of QoL in ALS, and to examine the relationships between QoL, illness severity and psychological distress in this patient group |

N = 26 ALS patients Median age 63 years (range 34–86) All patients were recruited through the Irish Register for ALS/motor neurone disease. The first eligible 26 patients consenting to take part were included. |

SEIQoL (N = 21) SEIQoL-DW (N = 5) Face-to-face interview was administered at the patient’s home (majority), in a hospital setting (3) and in a nursing home (1) Participants additionally administered the ALS Functioning rating Scale (ALSFRS) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) T1 |

Nomination of five areas of life being of greatest importance to the subject’s overall QoL |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 1 individual patient profile |

Domains nominated in SEIQoL and SEIQoL-DW (in descending percentage of total number of cues): ALS-related Family Hobbies Social life Occupation Independence Finances Spiritual life Miscellaneous |

| Smith et al. [32] | UK | To compare the sensitivity of four measures when used in a groups of cardiac patients undergoing the same intervention |

N = 16 patients after myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) Mean age 61 years (range 43–73) Consecutive patients referred to the Royal Devon and Exeter Health Care Trust for cardiac rehabilitation between January and April 1998 were asked to participate |

SEIQoL Face-to-face interviews were administered at the Royal Devon and Exeter Health Care Trust Participants additionally administered the 36-item Medical Outcomes Study Short-form General Health Survey (SF36), the Quality of life index-cardiac version (QLI), and the Quality of life after myocardial infarction questionnaire (QLMI) T1–T2 |

What are the five most important aspects of your life at the moment? |

Cues nominated by only 1 patient are labeled miscellaneous No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 1 individual patient profile |

Domains nominated as most important to overall QoL at T1 (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Health Leisure/hobbies Marriage Work Exercise Home life/environment Social life Independence Food Finances Miscellaneous Holidays/travel Pets Work related activity since retirement |

| Bayle et al. [33] | France | To determine whether patients change their selected items from one SEIQoL evaluation to the next. |

N = 30 patients scheduled to undergo total hip arthroplasty Mean age 57 years (range 22–74) The study included 47 eligible patients scheduled to undergo total hip arthroplasty in 1995 at the orthopedics department of the R. Salengo Teaching Hospital, Lille, France. Thirty patients completed the SEIQoL at T1 and T2. |

SEIQoL Face-to-face interview administered at the hospital T1–T2 |

Nomination of five items that have the greatest impact on the subject’s QoL at the time of the interview |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

Domains nominated at T1 (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Health Family Self-sufficiency Work Leisure activities Social life Financial resources |

| Waldron et al. [34] | Ireland | To determine whether the SEIQoL and SEIQoL-DW are valid, reliable and acceptable measures of QoL |

N = 80 patients with incurable cancer Median age 62 years (range 34–87) Forty patients were recruited from a weekly outpatient program held at the Irish National radiotherapy Center at St Luke’s Hospital in Dublin, and 40 were recruited as inpatients admitted to Our Lady’s Hospice in Dublin. |

SEIQoL (N = 62) SEIQoL-DW (N = 80) Face-to-face with inpatients administered at the hospital Place where the face-to-face interview with the patients from the outpatient program was administered: not specified T1 |

Nomination of five areas of life the subject considers to be central to his or her QoL |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 2 individual patient profiles |

The ten most frequently nominated domains in SEIQoL and SEIQoL-DW (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Health Social life/activities Spiritual life/religion Friendships/relationships Contentment/happiness Work Finances Marriage Mobility Pain free |

| Campbell and Whyte [35] | Scotland | To examine the QoL of cancer patients participating in phase I clinical trials |

N = 15 cancer patients participating in phase 1 clinical trials Mean/median age: not specified Fifteen patients were identified as eligible for this study during the 4-week period of data collection in March/April 1997 |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interview administered at the hospital T1 |

Nomination of five areas which are most important to the overall QoL of the subject |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 4 individual patient profiles |

Domains nominated as most important to overall QoL (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Health Leisure activities Social life Relationships Independence Finances Work Living conditions Physical activity Spiritual Religion Marriage Children Helping community Symptom control |

| O’Boyle et al. [36] | Ireland | To determine the sensitivity of SEIQoL to the impact of a surgical procedure by comparison with measures that do not include the patients’ perspective |

N = 20 patients undergoing unilateral total hip-replacement surgery Mean age 65 years (range 43–78) Consecutive patients from the greater Dublin area aged 40 and over attending Cappagh Hospital, Dublin with unilateral osteoarthritis of the hip were invited to participate |

SEIQoL Face-to-face interview administered at the hospital Patients additionally administered the McMaster health index questionnaire, the arthritis impact measurement scales and the life experiences survey T1–T2 |

Nomination of five areas of life the subject judges to be most important to his or her overall QoL |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 1 individual patient profile |

Domains nominated as essential to overall QoL at T1 (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Social/leisure activities Family Personal health Relationships Religion Work Finances Family health Independence Living conditions Miscellaneous Intellectual function Happiness |

| Echteld et al. [38] | The Netherlands | To determine to what extent patients admitted to palliative care units (PCU) in The Netherlands maintained good levels of individual quality of life |

N = 20 terminal patients admitted to a PCU N = 16 cancer patients (variety in cancer site) N = 3 cardiac patients N = 1 renal condition Mean age 73 years (range 52–93) Selection of a sample of 355 patients who were participating in a study in 10 PCUs in nursing homes in The Netherlands between January 2001 and July 2002. The condition of only 20 patients allowed interviewing. |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interviews administered at the PCU Participants additionally administered the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS). T1–T3 |

Nomination of five areas of life that are considered central to the subject’s QoL |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

Results of 17 complete sets of SEIQoL data (T1). Domains mentioned as important life areas at T1 (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Maintaining good contacts with family Maintaining good contacts with others Health Hobbies, pastime Religion Quality of care and attention Being physically active Functioning (physical, senses, mental) Good living conditions and housing Finances Good care for family Mobility Reversal of illness Being treated honestly and sincerely Dealing with the loss of relative or spouse Being independent Enjoying pleasant memories Dealing with issues at work |

| Fegg et al. [39] | Germany | To evaluate the relationship between personal values and individual quality if life (iQoL) in palliative care patients |

N = 64 patients treated for advanced cancer or ALS Median age 63 years (range 18–81) Seventy-five patients treated for advanced cancer or ALS at the Interdisciplinary Center for Palliative Medicine and the Outpatient Clinic of the Dept. of Neurology, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany were asked to participate |

SEIQoL-DW Place where the face-to-face interview was administered: not specified Patients additionally administered the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ) T1 |

Nomination of the life areas which are most important to the subjects’ individual QoL |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

Domains mentioned as important life areas (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Health Leisure time Friends Sports/motion Household Work Finances Partnership Nature, garden Freedom, relaxation, harmony Reading Religion Spirituality Communication Other |

| Frick et al. [41] | Germany | To compare the SEIQoL-DW with the EORTC QLQ-C30 in tumor patients before Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation (PBSCT) |

N = 79 patients suffering from various hematological malignancies undergoing high-dose therapy with PBSCT and participating in a psycho-oncologic psychotherapy program Mean/median age: not specified Sample: not specified |

SEIQoL-DW Place where the face-to-face interview was administered: not specified Patients additionally administered the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) T1 |

Nomination of five areas of life important to the subject’s overall QoL |

Cues nominated are grouped to 15 ‘aggregated cues’ [30] No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 1 individual patient profile |

The 9 most frequently nominated cue groups (aggregated cues) (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Hobbies, pastimes Health Profession, occupation Social life, friends Miscellaneous Marriage, partnership Finances Spiritual life, religion |

| Smith et al. [42] | UK | To evaluate the 6-month health outcomes of patients diagnosed with coronary heart disease (CHD) who were discharged from the chest pain service |

N = 57 patients diagnosed with CHD Mean age female patients 64 years Mean age male patients 61 years Overall range 40–79 Consecutive sample of patients admitted over a 4-month period with chest pain and a confirmed diagnosis of CHD |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interview was administered at the hospital Patients additionally administered the Seattle Angina Questionnaire, the Cardiovascular Limitations Profile (CLASP), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) T1 |

Nomination of five areas comprising the ‘quality’ parts of the subject’s life |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

Domains mentioned as important to patients’ quality of life (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Health Partner Sport Garden Work Friends Money House Car Church Grandchildren Holidays Television Craft Music Reading Pets Happiness Going out Animals Bingo Independence Sex Hope Food Reminiscence Do it yourself Caravan Photography |

| Ramström et al. [43] | Sweden | To evaluate the quality of life of cystic fibrosis patients with indications for home intravenous antibiotic treatment (HIVAT) |

N = 18 cystic fibrosis patients with indications for HIVAT Mean age 29 years (range 21–41) Patients treated at the University Hospital in Lund were recruited to participate in a clinical randomized cross-over study. Additionally they were invited to participate in this part of the study directed toward QoL |

SEIQoL-DW Questionnaire T1 |

Nomination of the 5 most important aspects of life |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 1 individual patient profile |

Domains nominated as important life areas (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Personal health Leisure activities Work Finances Friends Partner, spouse Sports Education Independence Home, dwelling Miscellaneous |

| Broadhead et al. [44] | Canada | To evaluate the feasibility of SEIQoL with an oncology sample and to compare the SEIQoL with a standards measure, the EORTC QLQ-C30 |

N = 15 patients with early stage prostate cancer Mean age 65 years (range 49–78) Men with early stage prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy at a cancer treatment center in a large western Canadian city who expressed an interest in participating |

SEIQoL Face-to-face interview administered at the cancer treatment center T1 |

Nomination of five domains the subject believes are most important to his/her QoL at the moment |

No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains Illustration of findings with 1 individual patient profile |

Domains initially nominated as important to patients’ quality of life (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Family Health Finances Leisure, hobbies, recreation Marriage Spiritual/religious life (experiential aspect; service aspect) Work Specific relationships Living conditions Social activities Friends/relationships Personal achievement Sex life Daily hassles Mental well-being |

| Stiggelbout et al. [45] | The Netherlands | To assess the feasibility and the validity of the adaptive conjoint analysis (ACA) to derive weights for individual QoL. Furthermore, agreement of the weighting procedures performed by the ACA and the direct weighting (DW) are assessed |

N = 27 cancer patients N = 20 patients with rheumatoid arthritis Mean age 61 years (range not specified) Convenience sample of outpatients with rheumatoid arthritis or cancer who were treated at the Leiden University Medical Center. |

SEIQoL-DW Face-to-face interviews administered at the hospital or at home T1 |

Nomination of five areas of live considered most important by the subject to his/her overall QoL |

Only domains that were mentioned by at least five patients are presented. The remaining domains are grouped together as ‘other’ No information on the analysis conducted to derive the presented QoL domains No illustration of findings with individual patients’ profiles |

Domains nominated by five or more patients T1 (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Other Own health Hobbies and relaxation Partner Social contact and friendship Work Family Partner and children Children Sports and holidays Transportation Health of partner Independence Feelings Activities of daily life |

Table 6.

Summary of eligible papers derived from literature search 2—studies using study-specific questions

| Reference paper | Country | Objective | Sample | Design | Self-rated question | Qualitative analysis | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bengtsson et al. [46] | Sweden | To explore what women with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) consider a good QoL |

N = 30 women experiencing IBS Median age 38,5 years Sample: all women who had received a diagnosis of IBD between January 1, 1998 and August 31, 2002 were asked to participate. |

The self-rated question was sent to the participants by mail for completion at home | What is your perception of a good quality of life? |

Content analysis—Burnard’s method for thematic content analysis [66] Analysis by 2 researchers Findings illustrated with patients’ quotes Patients could not verify the final list of categories |

18 subheadings were grouped into 5 categories (in descending frequency of answers in which the cue is mentioned): Physical and mental health (get rid of bowel symptoms; find explanation for bowel symptoms; knowledge about IBS; eat everything; no pain; sense of well-being; being without anxiety; good mood) Social well-being (social network; support from healthcare professionals; active leisure time) Welfare (good work; good economics) Strength and energy (feel fit and rested; feel relaxed; no stress) Self-fulfillment (command of life; confirmation; attain goals) |

| Johansson et al. [47] | Sweden | To explore the perceptions of QoL of incurably ill cancer patients |

N = 5 participants with incurable cancer living at home Median age 65 years Purposive sample |

Three focus group meetings in the hospital. Three meetings; purpose of the 3rd meeting was to elicit patients’ perceptions of the concept of QoL. |

When you hear the word quality of life what is the first thing you think of? |

Content analysis—Krippendorff [67] Analysis performed by 1st author, 2nd and 3th author examined the analysis Findings illustrated with patients’ quotes Analysis of all 3 focus groups for relevant information Patients could not verify the final list of categories |

5 categories related to QoL are identified (not in any order): Valuing ordinariness in daily life (appreciation of normal things; feeling functional) Alleviated suffering (physical well-being; psychological well-being; personal strategies to relieve pain) Maintaining a positive life (keeping memories alive; feeling of being needed) Significant relationships (essential networks; resonance in communication) Managing life when ill (to be in charge of the situation; to be reflective) |

| Widar et al. [48] | Sweden | To describe HRQoL in persons with long-term pain after a stroke |

N = 41 participants suffering from long-term pain after a stroke. Mean age 66 years Sample based on an inpatient register at a neurological clinic in a university hospital in Sweden. |

Face-to-face interview administered in the participant’s home Participants additionally administered the Short Form 36 (SF-36) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) within 2 weeks after the interview |

How would you describe your quality of life, especially in relation to your pain? |

Content analysis Discussion of categories among co-authors Findings illustrated with patients’ quotes Patients could not verify the final list of categories |

Four categories defining QoL are identified (not in any order): Physical aspects (freedom from pain; physical and cognitive capacity; physical independence) Psychological aspects (well-being; contentment; experienced freedom) Occupation (employment; leisure time) Social and economic aspects (family and relationships that work; social intercourse; economic security) |

| Larsson et al. [50] | Sweden | To examine what constitutes a good QoL for patients with carcinoid tumors. |

N = 19 patients with a carcinoid tumor. Median age 69 years Sample: 56 patients were eligible, of which 37 were excluded or not approached |

Face-to-face interview administered in the hospital Participants were presented the interview questions a few days before the interview. Participants were asked 3 other questions concerning distress and strategies to ‘keep a good mood’ |

What is important for you to perceive that you have a good quality of life? |

Content analysis Discussion of categories with co-authors Independent second assessor (none of the authors) assigned the text fragments to the categories Findings illustrated with patients’ quotes Three patients with carcinoid tumors could reflect upon the categories mentioned |

10 themes defining a good QoL are grouped in 3 categories (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Social (pursue hobbies/leisure time activities; associate with family and friends; live one’s life in accordance with one’s desire; work and pursue daily activities) Physical (health; good appetite; not experiencing fatigue; not experiencing pain in the abdomen; not having diarrhea) Emotional (good appearance) |

| Cohen and Leis [51] | Canada | To identify aspects cancer patients receiving palliative care consider important to their QoL. |

N = 60 palliative care cancer patients; half of them receiving home care and half from palliative care units. Mean age 68 years Sample: ? |

Face-to-face interviews either at home or in a palliative care unit | What is important to your quality of life? |

Content analysis in the editing style Analysis was carried out by multiple researchers, discussion of categories with co-authors Findings illustrated with patients’ quotes Patients could not verify the final list of categories |

50 themes are grouped into 5 categories (not in any order): Own state (physical condition; physical functioning; psychological state; cognitive functioning) Quality of palliative care (feeling secure/vulnerable; feeling cared for/treated with respect; spiritual care: continuity of care/continuity of staff; availability/acceptance of limitations of health care staff) Physical environment (right place to be: home/hospital; outdoors (access to nature, weather); indoors (does/does not meet psychosocial/physical/functional needs) Relationships (support; communication; change in role; being a burden; grow closer/more distant through crisis) Outlook (existential well-being/spirituality /facing death; hope; coping/being able to find some joy in life; uncertainty/control) |

| Constantini et al. [52] | Italy | To identify the content of QoL in a general cancer population. |

N = 248 cancer patients Mean age 53 years Sample: stratified by place of residence, primary cancer site and stage of disease. |

Questionnaire with open-ended questions, completed in the out-patient clinic or at home Participants additionally kept a diary Interview questions are in part derived from a study by Padilla et al. [56] |

What does the term quality of life mean to you? |

Content analysis Analysis was carried out by 3 people (research nurse, oncologist and psychologist), discussion of categories by the 3 raters For the categorization of the domains mentioned, an initial framework identified by the Consensus Conference of the Italian Society for Psycho-Oncology (SIPO) was used. Any (sub)domain not represented in the list was added to it. Findings illustrated with patients’ quotes Patients could not verify the final list of categories |

43 content domains of QoL are grouped into 15 categories. Aspects defining QoL (1st question) (in descending frequency of patients nominating the cue): Psychological well-being (feeling calm and relaxed; general; autonomy (physical and psychological); optimism/pessimism; coping strategies; being able to enjoy ‘things’; feeling hopeful; hoping in ‘science’; stress and anxiety; make future plans; body-image; self perception; taking care of one’s needs) ‘My own health’ Relationships with other people (with relatives/family; general; needing of support/understanding) Healthy way of living Financial welfare Conditions at work/job satisfaction Health care institutions (general organization; physical environment; health care professionals’ skills) Environment Functional status (general) Relationships with health care team (trust/esteem/support) Spiritual life/religion Chance and fortune |

| Archenholtz et al. [53] | Sweden | To examine what aspects of life Swedish women with chronic rheumatic disease found to be most important for their QoL |

N = 100 women with chronic rheumatic diseases; 50 women with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and 50 women with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Mean age SLE patients 44 years Mean age RA patients 45 years Representative sample of the female population in Gothenburg, Sweden |

Telephone interview | What does quality of life mean to you? |

Content analysis Analysis was carried out by 2 researchers, discussion of categories by the 2 researchers No illustration of findings with patients’ quotes Patients could not verify the final list of categories |

9 categories were identified defining QoL (not in any order): Health/wellness Family/friends Work House/home/living environment Social support/functional services Hobbies/cultural activities Sufficient income Independence Integrity/identity |

| Montazeri et al. [55] | UK | To examine what QoL means to patients with lung cancer |

N = 108 patients with lung cancer (cases) Mean age 67 years Consecutive random sample of patients with lung cancer attending a chest clinic N = 92 patients with chronic respiratory disease (controls) Mean age 64 age years Consecutive random sample of patients with chronic respiratory disease |

Face-to-face interview administered in the hospital Patients additionally completed the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) and the European Organization of Research and Treatment for Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) |

What is quality of life? What is a good quality of life for you? |

Content analysis Numbers of researchers analyzing the data is unknown No illustration of findings with patient’s quotes Patients could not verify the final list of categories |

8 categories defining QoL and a good QoL are identified. Aspects defining QoL (cases): Health (own health) Enjoyment of life Happiness Family life Ability to do what one wants to do/work Financial security Social life/leisure activities Living longer |

| Padilla et al. [56] | USA | To identify the attributes cancer patients with pain use in defining QoL. |

N = 41 cancer patients with chronic pain; 38 patients were hospitalized, 3 were outpatients Mean age 49 years, median age 51 years Convenience sample |

Face-to-face interview administered in the hospital Patients selected the time when they wished to be interviewed |

What does the term, quality of life, mean to you? For you, what contributes to a good/bad or poor quality if life? |

Content analysis using the nine-step procedure as described by Waltz et al. [68] Analysis was carried out by 5 researchers, discussion of categories by the 5 researchers Two additional researchers coded a sample of responses (interrater reliability 90%) No illustration of findings with patients’ quotes Patients could not verify the final list of categories |

3 categories defining good and poor QoL are identified. Aspects defining good QoL (in descending order of attributes mentioned): Physical well-being: General functioning (feeling healthy; feeling independent; having a normal life; able to work; feeling strong; good food/eating) Disease/treatment-specific attributes (feeling no pain) Psychological well-being: Affective-cognitive attributes (enjoying life; spiritual support; feeling happy/happiness; inner peace; able to concentrate; communicating) Coping ability (feeling secure; adapting/adjusting; positive mental attitude) Accomplishments (feeling successful; feeling satisfied; improving surroundings) Meaning of pain and cancer (Pain/CA-positive effect) Interpersonal well-being: Social support (supportive relations) Social/role functioning (making others happy; fulfilling one’s role) |

Half of the included studies were conducted among patients with cancer [15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24, 28, 34, 35, 41, 44, 47, 50–52, 55, 56], whereas the other studies included patients with a range of other somatic illnesses (see Table 3). In three studies, the patient sample consisted of a combination of both patients with cancer and patients with another somatic illness [38, 39, 45].

Table 3.

Patient classification according to somatic illness and method of enquiry for literature searches 1 and 2

| Disease cluster | Disease category | SEIQoL | Study-specific question |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Cancer | [38 a, 45 a] | |

| General cancer population | [52] | ||

| Advanced cancer | [39]a | ||

| Palliative | [51] | ||

| Metastatic cancer | [19] | ||

| Incurable metastatic cancer | [22] | ||

| Incurable cancer | [34] | [47] | |

| Carcinoid tumors | [50] | ||

| Prostate cancer | [15, 21, 44] | ||

| Lung cancer | [18] | [55] | |

| Hematological malignancies | [16, 41] | ||

| Lymphoma and leukemia | [28] | ||

| Malignant cord compression | [24] | ||

| Cancer patients with pain | [56] | ||

| Patients with cancer participating in Phase 1 clinical trials | [35] | ||

| Cerebrovascular/neurological conditions | ALS | [29, 31, 39]a | |

| Parkinson’s disease | [17] | ||

| Cardiovascular conditions | Coronary heart disease | [42] | |

| Heart failure | [38]a | ||

| Patients randomized to VVI(R) or atrial based pacing modes | [23] | ||

| Patients after myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass craft | [32] | ||

| Persons with long-term pain after a stroke | [48] | ||

| Gastro-intestinal conditions | Irritable bowel syndrome | [7] | [46] |

| Musculoskeletal conditions | Patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty | [33] | |

| Patients undergoing total hip replacement | [36] | ||

| Chronic rheumatic diseases | [45]a | [53] | |

| Renal conditions | Kidney function | [38]a | |

| Autosomal recessive disorders | Cystic fibrosis | [43] | |

| Infectious diseases | HIV/AIDS | [8] | |

| Other | Patients admitted to a medicine for the elderly service | [26] |

aMixed patient sample

In most studies, a face-to-face interview was conducted to elicit patients’ QoL domains [7, 8, 15–19, 21–24, 26, 28, 29, 31–37, 39, 41, 42, 44, 45, 48, 50, 51, 55, 56]. In the remaining studies, QoL domains were identified by means of a telephone interview [53], focus groups [47], or a questionnaire employing open-ended questions [43, 46, 52].

Studies using SEIQoL presented a median of 16 QoL domains (range 7–62), and studies using study-specific questions presented a median of 13 QoL domains (range 9–29) (Appendix 1).

Elicited QoL domains

QoL domains categorized according to the SEIQoL prompt list

Table 1 provides the QoL domains categorized according to the 9 domains included in or highly related to the SEIQoL prompt list, as derived from the studies using the SEIQoL and studies using study-specific questions, separately. As the first two columns of Table 1 illustrate, SEIQoL studies are unique in presenting the prompt list domains relationships, finances, and living conditions, whereas family, health, work, social life, leisure activities and religion/spiritual life are also reported by one to two studies using study-specific questions. More interestingly, both types of studies report domains related to the SEIQoL prompt list (see last two columns of Table 1). These domains entail more specific information as opposed to the SEIQoL prompt list domains. For example, we classified the presented domains friends, neighbors, associate with family, lover, and marriage, into the domain relationships-related.

All studies using SEIQoL and study-specific questions report a domain referring to health, either by presenting the SEIQoL prompt list domain health, or in presenting a health-related domain. The majority of the studies employing the SEIQoL report other QoL domains included in or highly related to the SEIQoL prompt list (63–100%), whereas fewer studies using study-specific questions do so (22–89%). SEIQoL studies are unique in presenting the domains marriage and/or partnership and spousal welfare (relationship-related), activity and mobility (health-related) and in presenting specific hobbies (leisure activity-related). Irrespective of the method of enquiry, the domain presented least often is living conditions.

QoL domains categorized inductively

Table 2 displays the classification of the QoL domains that could not be grouped according to the domains included in or highly related to the SEIQoL prompt list. These QoL domains are classified into 8 inductively generated, additional domains. Interestingly, ‘independence’ is mentioned in 74% of the studies using the SEIQoL and is thus more frequently reported than the SEIQoL prompt list domains religion/spiritual life (70%), social life (63%) and living conditions (63%). The other inductively generated domains are less frequently reported in studies using the SEIQoL (4–48%) than in studies using study-specific questions (33–78%). The latter group of studies have more elaborate presentations of domains related to psychological functioning (e.g., the domains relaxation and being without anxiety) and coping/positive attitude (e.g., the domains coping strategies and being able to enjoy things). Conversely, only studies using the SEIQoL (N = 6) present the QoL domain sexuality. Irrespective of the method of enquiry, the domain quality of care is presented least often.

Discussion

Perhaps, one of the most important aspects of patients’ QoL is their evaluation of important life domains. Domains that patients consider important are preferably elicited by qualitative interviews. This information is indirectly captured in standardized questionnaires that use patient-generated item content.