Abstract

Calreticulin (CRT) is a multifunctional protein mainly localized to the endoplasmic reticulum in eukaryotic cells. Here, we present the first analysis, to our knowledge, of evolutionary diversity and expression profiling among different plant CRT isoforms. Phylogenetic studies and expression analysis show that higher plants contain two distinct groups of CRTs: a CRT1/CRT2 group and a CRT3 group. To corroborate the existence of these isoform groups, we cloned a putative CRT3 ortholog from Brassica rapa. The CRT3 gene appears to be most closely related to the ancestral CRT gene in higher plants. Distinct tissue-dependent expression patterns and stress-related regulation were observed for the isoform groups. Furthermore, analysis of posttranslational modifications revealed differences in the glycosylation status among members within the CRT1/CRT2 isoform group. Based on evolutionary relationship, a new nomenclature for plant CRTs is suggested. The presence of two distinct CRT isoform groups, with distinct expression patterns and posttranslational modifications, supports functional specificity among plant CRTs and could account for the multiple functional roles assigned to CRTs.

Calreticulin (CRT) is a highly conserved protein mainly localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in plants and to the ER/sarcoplasmic reticulum in mammals (for review, see Crofts and Denecke, 1998; Michalak et al., 1999; Hadlington and Denecke, 2000; Johnson et al., 2001). CRT is a multifunctional protein, suggested to be involved in over 40 intra- and extracellular processes in mammalian cells. However, the main focus has been on its role in calcium signaling (Camacho and Lechleiter, 1995; Nakamura et al., 2001; Arnaudeau et al., 2002) and as a chaperone (Hebert et al., 1996; Saito et al., 1999; Nakamura et al., 2001). CRT comprises three major subdomains: a highly conserved N domain, a high-affinity but low-capacity Ca2+-binding P domain, and a low-affinity but high-capacity Ca2+-binding C domain ending with an ER retention signal (Michalak et al., 1999).

Although the role of CRTs as chaperone-like proteins and in calcium signaling is well established in mammals, the functions of CRT have been elusive in plants until recently. Plant CRTs have been shown to bind calcium with similar characteristics as their mammalian homologs (Chen et al., 1994; Hassan et al., 1995; Navazio et al., 1995; Coughlan et al., 1997; Li and Komatsu, 2000) and recently also to have calcium-storing functions in the ER of plant cells (Persson et al., 2001; Wyatt et al., 2002). In contrast to most animal CRTs, glycosylation of CRTs is generally observed in plants (Navazio et al., 1995, 2002; Pagny et al., 2000). Plant CRTs are up-regulated in response to a variety of stress-mediated stimuli, e.g. pathogen-related signaling molecules (Denecke et al., 1995; Jaubert et al., 2002) and gravistimulation (Heilmann et al., 2001), and are highly expressed during mitosis (Denecke et al., 1995), embryogenesis (Borisjuk et al., 1998), and in floral tissues (Chen et al., 1994; Denecke et al., 1995; Nelson et al., 1997). In addition, CRT preferentially localizes to plasmodesmata in maize (Zea mays) root tips and is suggested to be involved in regulation of the closure of plasmodesmata (Baluska et al., 1999).

The dogma for CRT in human (Homo sapiens) and mouse (Mus musculus) has been: one gene, one mRNA, and one protein. However, recently, an additional isoform was identified (Persson et al., 2002b). The sequence of the newly discovered CRT isoform differed significantly from the previously established isoform but still contained typical CRT features. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the early duplication of the CRT genes in mammals generated two distinct CRT groups. In plants, two or more isoforms exists in several species, e.g. Arabidopsis, maize, and barley (Hordeum vulgare; GenBank accession no. 190454; Chen et al., 1994; Kwiatkowski et al., 1995; Nelson et al., 1997). With the exception of the Arabidopsis isoforms, the reported isoforms all have a high sequence similarity, implying a recent duplication of the CRT gene in these species. Of the three described CRT sequences in Arabidopsis, the CRT1 and CRT2 sequences share higher sequence homology to each other than compared with the third isoform, CRT3 (Nelson et al., 1997). In an evolutionary context, this implies that two duplications of the CRT gene in Arabidopsis took place at different times.

Here, we report that both monocotyledons and eudicotyledons contain two distinct groups of CRTs. The early duplication of the CRT gene in plants is strikingly similar to the duplication of the CRT gene in mammals (Persson et al., 2002b). The intron/exon organization of CRT genes encoding different isoforms reinforces the prediction of a common ancestry for the CRT gene. To verify the existence of the two isoform groups, we cloned a CRT3 ortholog in Brassica rapa based on the known Arabidopsis sequence characteristics. In addition, analyzes of tissue-dependent and stress-related expressions and posttranslational modifications of the different isoforms were carried out to evaluate in silica predictions and to test the proposed evolutionary model.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic Analysis of CRT Amino Acid Sequences in Plants

The Arabidopsis genome harbors three expressed CRT genes (Nelson et al., 1997). In addition, the Arabidopsis genome also contains a putative CRT pseudogene (locus At1g56390), consisting of four potential exons, corresponding to exons 1, 2, 3, and 6 of CRT1 (data not shown).

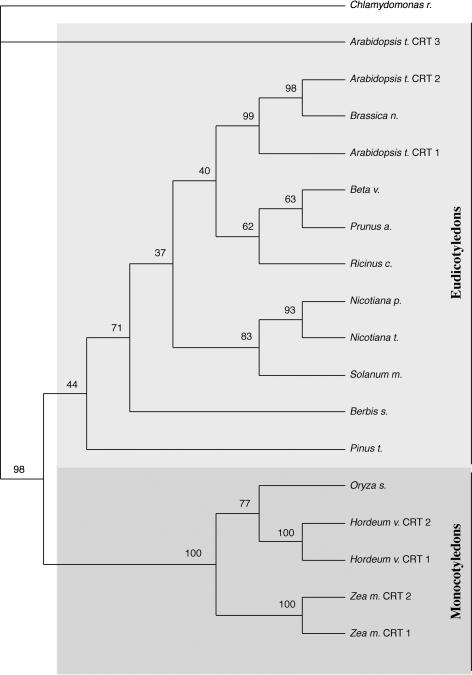

To get a more complete picture of the number of CRT isoforms identified in plants, we performed a standard BLASTP analysis at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) using CRT protein sequences corresponding to the Arabidopsis isoforms. We found 18 unique protein sequences annotated as CRT (data not shown). From these, a rooted phylogenetic tree was created (Fig. 1). In both monocotyledons and eudicotyledons, there appears to be at least two CRT isoforms with high sequence identity, e.g. CRT1 and CRT2 in maize, Arabidopsis, and barley (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of CRT protein sequences in plants. A rooted phylogenetic tree with topology representative for plant CRTs, generated with the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii CRT as outgroup. A heuristic search using the maximum parsimony method was done on the alignment of 18 unique plant CRT protein sequences. Two major groups are prominent: monocotyledons and eudicotyledons. These groups are presented in different shades of gray.

The topology of the phylogenetic tree reveals an early duplication event in the species Arabidopsis, from which the CRT1/CRT2 and the CRT3 isoforms derive, perhaps predating the evolutionary split of plants into dicots and monocots (Soltis et al., 1999). This early divergence of CRTs in Arabidopsis advocates the existence of orthologous isoforms (CRT3s) in other plant species. Therefore, a standard BLASTN with Arabidopsis CRT3 was performed at the NCBI against expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and full-length cDNAs from various plant species. Two putative full-length mRNAs (GenBank accession nos. AY105822 and AP003316), predicted from genomic sequences, were obtained from maize and rice (Oryza sativa). The sequences were denoted maize CRT3 and rice CRT3, respectively.

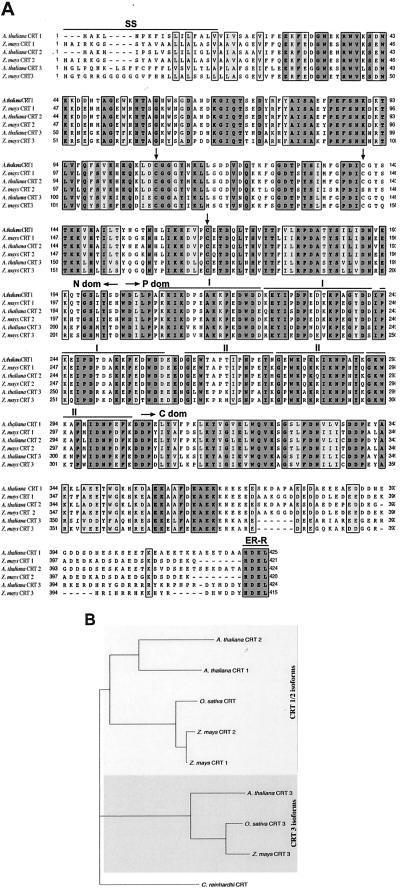

To investigate sequence homology to Crts from the two isoform groups, the maize CRT3 was translated into an amino acid sequence and aligned with Arabidopsis CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 and maize CRT1 and CRT2 (Fig. 2A). The maize CRT3 sequence consists of 415 amino acids and shows 70% identity to the Arabidopsis CRT3 isoform but only 57% and 55% identity to the maize CRT1 and CRT2 isoforms, respectively (data not shown). Several of the typical CRT sequence features, conserved among CRT proteins from different kingdoms (for review, see Michalak et al., 1999) were conserved in the maize CRT3 sequence. These include: three Cys residues important for the correct folding of CRTs (Matsuoka et al., 1994), a potential ER signal sequence located in the N terminus, two triplets of conserved regions in the P domain, and a typical ER retention motif (HDEL) in the far end of the C terminus (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Sequence comparison of CRT isoforms from Arabidopsis and maize. Comparison of the amino acid sequences from Arabidopsis CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 with maize CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 (GenBank accession nos. AAC49695, AAK74014, and AAC49697 with CAA86728, AAF01470, and AY105822, respectively) was made using a ClustalW analysis algorithm. A, Vertical alignments between the sequences for identical and similar amino acids are highlighted in different shades of gray. The black line (SS) overlaying the immediate N terminus of the CRT isoforms corresponds to a putative ER signal sequence segment. The black arrows indicate the positions of three highly conserved Cys residues. The black lines (I and II) overlaying the sequence alignment corresponds to two triplets of conserved regions in the P domain of the proteins. The black line (ER-R) overlaying the immediate C terminus corresponds to an ER retention signal. The approximate position of the three domains (N, P, and C) are indicated. B, Rooted phylogenetic tree based on the protein alignment, including CRT1/2, and CRT3 protein sequences from rice (GenBank accession nos. BAA88900, and BAC06263, respectively) and the CRT protein sequence from C. reinhardtii (GenBank accession no. CAB54526), the latter used as outgroup. Two distinct clusters can be observed: CRT1 and CRT2 isoforms versus CRT3 isoforms. Bootstrap values are indicated on respective branch.

The two triplets of conserved regions in the P domain, denoted I and II, are well conserved in maize CRT3 (Fig. 2A). Comparison of the 18 aligned plant CRT sequences gave the repeats in region I the consensus sequence of PXXIXDPXXKKPEXWDD and in region II the consensus sequence of GXWXAXXIXNPXYK (data not shown). In animal CRTs, the repeat I and II consensus sequences are PXXIXDPDAXKPEDWDE and GXWXPPXIXNPXYX, respectively (Michalak et al., 1999). Thus, the two triplet repeats are conserved but not identical in vertebrates and plants.

To verify expression of the putative maize and rice CRT3 genes, a BLASTN search was performed at NCBI against ESTs from rice and maize, respectively. We obtained six ESTs from maize, and one EST from rice with E values below 2 e-64 (score > 200), confirming that the CRT3 gene is transcribed in maize and rice (Table I).

Table I.

EST analysis of CRTs from Arabidopsis, maize, and rice

a Due to sequence similarities between the isoforms CRT1 and CRT2 in monocotyledons, ESTs correlating to respective isoforms could not be distinguished.

To corroborate that the putative maize and rice CRT3 isoforms are orthologs to the Arabidopsis CRT3 isoform, an exhaustive phylogenetic analysis of Arabidopsis, maize, rice, and C. reinhardtii CRT proteins was performed. A tree was constructed using CRT from C. reinhardtii as outgroup (Fig. 2B). Two distinct clades of CRTs, supported by high bootstrap values, were evident: a CRT1/CRT2 isoform group and a CRT3 isoform group. To emphasize the existence of the two clusters, we are using the label CRT1/CRT2 isoform group and CRT3 isoform group for CRTs belonging to the respective isoform cluster. The isoform-specific clades were similar when an analogous analysis was performed using corresponding CRT nucleotide sequences (data not shown).

CRT Gene Maps

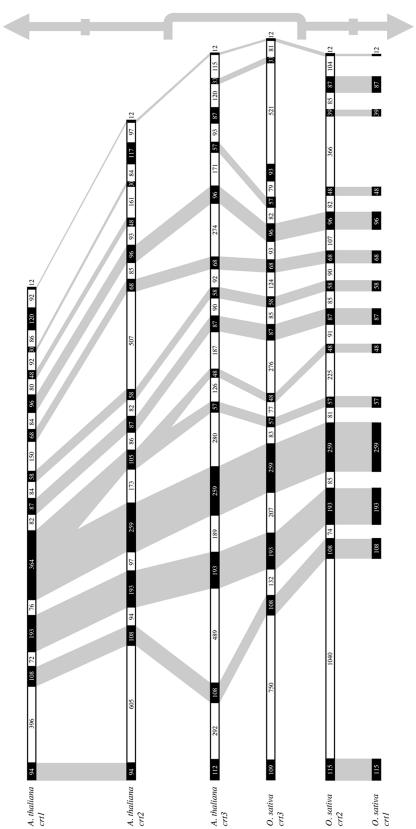

Genomic CRT sequences from the different isoforms in both monocotyledons and eudicotyledons were analyzed to obtain the exon/intron organizations for the CRT genes in higher plants. In Arabidopsis, individual CRT exon lengths were generally conserved between the genes (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Gene maps of CRT genes in Arabidopsis and rice. Black boxes, Exons; white boxes, introns. Exon and intron sizes are indicated in number of base pairs within each box. The gene names and corresponding species are listed to the left. The vertical arrows to the right indicate the potential direction of evolution. Genes best representing the most ancestral CRT genes, CRT3s, are within a gray bracket, and the direction of gene divergence is indicated with adjacent arrows. Conservation of exon size between genes is indicated by shaded areas.

Analogous information from monocotyledons were obtained using BLASTN searches of the rice genome (for draft descriptions, see Goff et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2002) at the NCBI with cDNAs corresponding to the CRT1/CRT2 isoform group (GenBank accession no. AB021259) and the CRT3 isoform group. A 100% sequence identity was obtained when aligning the CRT3 cDNA with the corresponding genomic clone (GenBank accession no. AAAA01001172). However, when aligning the CRT1/CRT2 cDNA with the reverse complement of the only genomic sequence hit obtained (GenBank accession no. AAAA01007283), we discovered that the hit only showed 98% sequence identity with the query entry and, thus, harbored a novel CRT isoform. The genomic sequence corresponding to the rice CRT used in the initial BLASTN search is currently not available. Hence, it appears that the evolution of CRT isoforms in rice is similar to the isoform evolution in maize and barley, yielding two closely related paralogs for the CRT1/CRT2 isoform group and a more distantly related CRT3 isoform (Fig. 1).

The obtained genomic clones from rice were used to generate individual exon lengths for the CRT isoforms. Although only one genomic clone corresponding to the CRT1/CRT2 isoform group was found, a 100% sequence identity in the splice regions to both CRT1 and CRT2 in maize gave the exon lengths for both isoforms (Fig. 3). Although exons encoding the C terminus vary considerably for different isoforms and species, both in lengths and splice codons, all exons encoding the N and P domains of the proteins are conserved, with splice sites located in the same corresponding regions (Fig. 3).

Evolution of the CRT Gene in Higher Plants

In silica mapping of the Arabidopsis CRTs reveals that the CRT2 and CRT3 genes are located closely together on chromosome 1 at loci At1g09210 (GenBank accession no. AY045656) and At1g08450 (GenBank accession no. U66345), respectively. The CRT1 gene is also located on chromosome 1 at locus At1g56340 (GenBank accession no. U66343). To investigate potential relationships between major duplication events in the Arabidopsis genome and the evolution of the CRT gene, we examined if any of the CRT loci were situated in known duplicated genomic segments. Although the CRT1 and CRT2 genes were found in a region that was duplicated approximately 50 million years ago (Vision et al., 2000; blocks 8a and 8b in Fig. 1), the CRT3 gene locus is located in a region without any major duplication activity reported (data not shown).

The evolutionary split between the monocotyledons maize and rice has been estimated to be 52 ± 15 million years ago (Bremer, 2002). When comparing CRT1/CRT2 sequences for these species, an identity of approximately 85% is observed. Because the sequence identity between CRT1 and CRT2 in Arabidopsis is 83%, the predicted time of the genomic duplication of the Arabidopsis CRT locus appears probable.

A close examination of the exon/intron patterns of CRTs in different species revealed an apparent pattern of evolution. Overall, the sizes of exons, including exon fusion products, are conserved among isoforms and species investigated, with the exception of exons 1 and 11 to 13 (exon nos. for the CRT3 isoforms; Fig. 3). The CRT3 gene has 14 exons in Arabidopsis, rice, and maize, with exon sizes highly conserved except for exon 1 and 12 (Fig. 3). A comparison of genes from the CRT1/CRT2 isoform groups among species revealed that CRT1 and CRT2 in both maize and rice contain 14 exons similar to the CRT3 genes, whereas CRT1 and CRT2 in Arabidopsis only contain 12 and 13 exons, respectively. This result is predicted from exon fusions of exons 4 to 6 in Arabidopsis CRT3, generating larger exons: exon 4 in CRT1 and exon 5 in CRT2 (Fig. 3). Thus, the conservation among the CRT genes is highest for the CRT3 isoforms in the investigated species, whereas the CRT1/CRT2 isoforms show evolutionary deviations among monocotyledons and eudicotyledons.

Cloning and Expression of CRT Orthologs in B. rapa

To obtain additional information regarding orthologous CRT1/2 and CRT3 isoforms, a standard BLASTN search was performed against ESTs from various plant species at the NCBI. Although several plant species were found to have ESTs corresponding to either putative CRT1/2 or CRT3 isoforms (score > 200, respectively), only B. rapa contained ESTs correlating to both isoform groups (data not shown). The ESTs corresponding to the CRT1/2 and CRT3 isoform groups from B. rapa were aligned, and the overlapping sequences were used to generate specific probes for the putative CRT1/2 and CRT3 isoforms. Both probes recognized a band at an approximate size of 1.4 kb of the total RNA from B. rapa leaves, indicating that the two isoform groups are present in B. rapa (data not shown).

Overlapping ESTs for CRT3 from B. rapa were also used to generate sequence specific primers against the 5′ end of the putative CRT3 isoform, whereas an oligo(dT15) primer was used for extension from the 3′ end. A 1,300-bp nucleotide sequence was obtained. Of these, the first 1146 were sequenced (GenBank accession no. AY336743), and an open reading frame encoding 381 amino acids was generated (Fig. 4). We were unable to obtain the sequence for the far C-terminal end, most likely due to secondary structures in the nucleotide sequence (Technical Support, MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). The deduced amino acid sequence shows high homology to the CRT3 isoforms in Arabidopsis and maize (91%, and 72% identity, respectively) but only 58%, and 57% identity to the Arabidopsis CRT1, and CRT2 isoforms, respectively. Furthermore, the B. rapa CRT3 isoform contained the typical CRT features indicated in Figure 4. The sequence was aligned with CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 from Arabidopsis and CRT from C. reinhardtii, and an exhaustive phylogenetic analysis was performed. Using the CRT from C. reinhardtii as outgroup, two distinct clusters were obtained with the putative B. rapa CRT3 sequence closely clustered with the Arabidopsis CRT3 (data not shown). These data strengthen the hypothesis advocating two distinct CRT isoform groups in both mono- and eudicotyledons.

Figure 4.

Cloning of CRT3 from B. rapa. Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of the CRT3 isoform (GenBank accession no. AY336743) in B. rapa. Several CRT characteristics are indicated in accordance with Figure 2. The transparent boxes indicate the three conserved Cys residues.

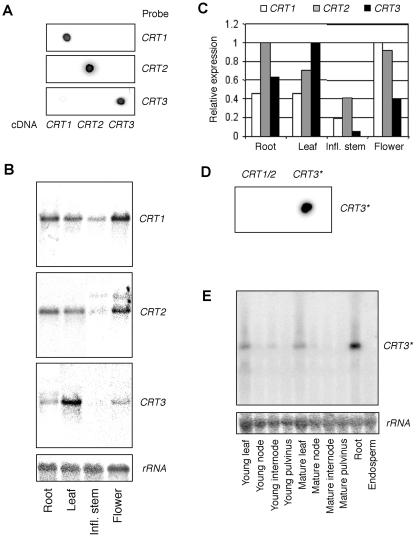

Tissue-Dependent Expression of CRT Isoforms in Arabidopsis and Maize

Northern-blot analyzes of various tissue types from both Arabidopsis and maize were performed to determine where the CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 isoforms are expressed (Fig. 5, A–F). cDNAs corresponding to CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 isoforms and CRT1/CRT2 isoforms were used as probes for Arabidopsis and maize, respectively. For the maize CRT3 isoform, a 101-nucleotide probe corresponding to the 3′-UTR was generated, and cross-reactivity among the probes was checked. None of the probes showed any cross-reactivity within respective species (Fig. 5, A and D).

Figure 5.

Expression of CRT isoforms in Arabidopsis and maize. A and D, Examination of cross-hybridization of the Arabidopsis CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 (A) and maize CRT1/2 and CRT3 (D) isoform probes. One hundred nanograms of each probe was applied to the membrane and subsequently probed with radiolabeled CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 probes corresponding to respective species. The cross-hybridization was performed in parallel with northern-blot hybridizations. B and E, Northernblot analyses of total RNA (Arabidopsis, 10 μg lane–1; and maize, 14 μg lane–1) from various tissues in Arabidopsis (B) and maize (E). Membranes were probed with radiolabeled CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 probes (Arabidopsis) and a CRT3 probe (maize) within respective species. Radiolabeled rRNA was used as a control. Arabidopsis experiments were performed independently three times and gave similar expression profiles. Maize experiments were performed once to confirm Arabidopsis patterns. C, Visualization of relative expression of CRT isoforms in various tissues for Arabidopsis. Asterisk, Maize CRT3 probe corresponds to a 101-nucleotide 3′-untranslated region (UTR) segment.

The Arabidopsis CRT1 and CRT2 isoforms were mainly expressed in leaves, roots, and flowers, with a lower expression in the inflorescence stem (Fig. 5, B and C). On the other hand, the Arabidopsis CRT3 isoform was predominantly expressed in leaves and roots and was only detected at very low levels in the inflorescence stem (Fig. 5, B and C). A similar expression pattern was observed in maize, where the CRT1/CRT2 isoforms were present in all investigated tissues (data not shown), and the CRT3 isoform was most abundant in leaves and roots (Fig. 5E). Because the northern-blot analysis only revealed relative expression levels within each isoform group, we performed an EST analysis for the Arabidopsis, maize, and rice CRT cDNAs at the NCBI. Substantially more ESTs corresponding to the CRT1/CRT2 isoform group than to the CRT3 isoform group were obtained, suggesting that CRT1 and CRT2 are expressed in higher abundance in higher plants (Table I).

Stress Induction of the CRT Genes in Arabidopsis

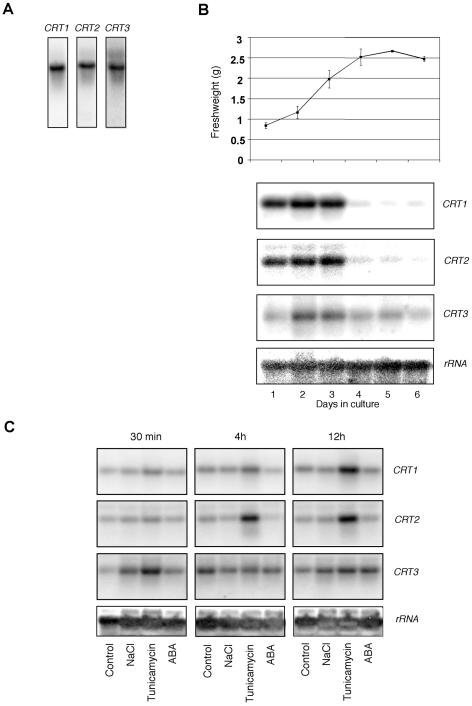

To obtain information about the regulation of the different CRT isoforms, we used Arabidopsis cell suspension cultures. All three CRT isoforms were expressed in the suspension cells (Fig. 6A). We also investigated the expression of the different isoforms during different phases of the growth period. Although both CRT1 and CRT2 showed a high expression during the 3 first d, corresponding to a rapid phase of growth, the CRT3 expression was more evenly distributed over the growth period examined (Fig. 6B). Because high initial expression of the CRT isoforms would diminish putative up-regulations of the genes in response to certain stresses, we chose to perform stress experiments on 4-d-old cell cultures. We used salt, tunicamycin (an inhibitor of N-linked glycosylation processes), and ABA as stress mediators and monitored changes in the expression for CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 after 30-min and 4- and 12-h treatments (Fig. 6C). CRT3 showed a fast response to salt and tunicamycin, with a severalfold increase in expression for both treatments (30 min in Fig. 6C). In contrast, both CRT1 and CRT2 showed no major increase in expression in response to 30-min treatments. However, after 4 h of stress exposure, both the CRT1 and CRT2 expression increased severalfold in response to tunicamycin (4 h in Fig. 6C). The induction of CRT1 and CRT2 was maintained and further increased after 12 h of tunicamycin treatment (12 h in Fig. 6C). On the other hand, the increased CRT3 expression observed at 30 min was no longer evident.

Figure 6.

Analysis of CRT expression in Arabidopsis suspension cell cultures. Northern-blot analyses of total RNA (5 μg lane–1) from Arabidopsis cell suspension cultures. Membranes were probed with radiolabeled CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 probes. Radiolabeled rRNA was used as a control. A, Untreated material probed with the different isoform probes. B, Upper, Fresh weight for the Arabidopsis cell suspension cultures at different days in culture. Lower, Relative expression of the isoforms corresponding to different days in culture. C, Arabidopsis suspension culture cells treated with either 150 mm NaCl, 15 μg mL–1 tunicamycin, or 100 μm abscisic acid (ABA). Cells were either treated for 30 min, 4 h, or 12 h. Radiolabeled rRNA was used as a control. Experiments were performed twice and gave similar expression patterns.

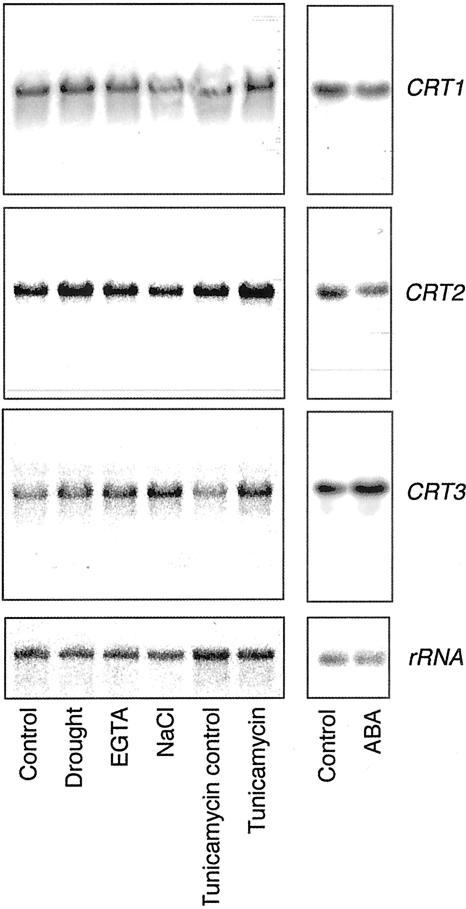

To investigate if a similar induction of the CRT genes occurs in whole plants, we performed stress experiments with Arabidopsis plants grown on liquid medium. In addition to the treatments described above, plants were subjected to drought and EGTA treatments. CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 transcripts all increased in whole plants after 2 h of tunicamycin treatment (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the CRT3 expression was increased in response to salt stress, similar to what was observed in the cell cultures (compare Figs. 6C and 7). Hence, in addition to differences in tissue-dependent expression, differences are seen in stress-induced expression among the Arabidopsis CRT isoforms.

Figure 7.

Stress induction of CRT expression in Arabidopsis plants. Northern-blot analyses of total RNA (10 μg lane–1) from Arabidopsis plants grown on liquid medium. Membranes were probed with radiolabeled CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 probes. Radiolabeled rRNA was used as a control. Plants were treated with 150 mm NaCl, 15 μg mL–1 tunicamycin, 10 mm EGTA, and 100 μm ABA or exposed to drought stress. Plants were harvested after 2-h treatments. The ABA treatment was performed as a separate experiment. Experiments were performed twice and gave similar expression patterns.

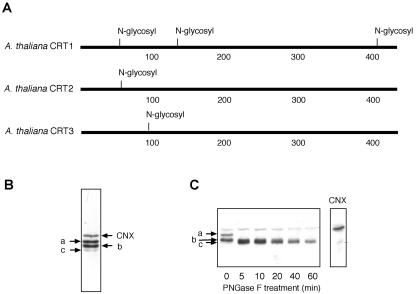

Variation in Glycosylation Status among CRT Isoforms in Arabidopsis

Potential differences in posttranslational modifications among CRT isoforms were analyzed using the MacVector 7.0 software (Oxford Molecular Group Plc, Oxford). The two isoform groups differ in the number of negatively charged amino acids in the C-terminal region (data not shown). In addition, we found three potential glycosylation sites in the CRT1 sequence but only one in the CRT2 and CRT3 sequences, respectively (Fig. 8A). Putative differences in the number of attached glycans were also suggested by western blots, where three bands (a–c in Fig. 8B), corresponding to CRTs, were obtained. To confirm that the size differences of the bands were due to attached glycans, an Arabidopsis homogenate was treated with the glycosidase PNGase F, which removes N-linked glycans. Figure 8C shows that the upper band disappears after a brief PNGase F treatment, indicating that glycans attached to this CRT was easily accessible for the glycosidase. Furthermore, one band showed remarkable resistance to the glycosidase and disappeared only after prolonged treatment (band termed b in Fig. 8C). Thus, the different CRT isoforms harbor differences in attached N-linked glycans, potentially in numbers of attached glycans, which show variations in resistance toward glycosidase PNGase F.

Figure 8.

Differences in N-linked glycosylation status among different CRT isoforms in Arabidopsis. A, Analysis of CRT protein sequences predicted three potential glycosylation sites in CRT1 and one in CRT2 and CRT3, respectively. Analysis was performed using MacVector 7.0 Software. B, Arabidopsis homogenate was analyzed by 10% (w/v) SDS-PAGE (15 μg protein lane–1), blotted, and immunostained with polyclonal antibodies against maize CRT (1:5,000 [v/v]). Bands (a–c) next to lanes correspond to CRTs with differences in glycosylation status. C, Arabidopsis homogenate treated with N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) for 5 to 60 min under native conditions. The panel to the right shows lane probed with polyclonal antibodies against Arabidopsis calnexin (CNX; 1:1,000 [v/v]).

DISCUSSION

CRTs have been implicated in a variety of cellular processes, spanning from a mediator of cellular adhesion in the extracellular matrix to regulation of calcium signaling and protein folding in the ER lumen (Johnson et al., 2001). The functional diversity of the protein has lead to a search for additional CRT isoforms, resulting in the discovery of a second isoform (Crt2), present in several mammalian species (Persson et al., 2002b). To further corroborate diversity among plant CRT proteins, we report here the existence of two distinct CRT isoform groups among higher plant species.

Several investigations have established that plants contain two or more CRT isoforms (Chen et al., 1994; Kwiatkowski et al., 1995; Nelson et al., 1997). The present nomenclature for plant CRTs suggests that duplication events resulted in two or several orthologs. However, it now appears that plant CRT1 and CRT2 isoforms rather represent paralogous isoforms within respective species, whereas the CRT3 isoform appears to have orthologs (Figs. 1 and 2B). Therefore, we have used the label CRT1/CRT2 isoform group and CRT3 isoform group for CRTs belonging to the respective isoform cluster. To avoid future misunderstandings regarding functional aspects of CRT isoforms, we suggest a reevaluation of the CRT nomenclature within the Viridiplantae kingdom. Proposed names should be in accordance with current ontology, i.e. CRT1a and CRT1b for the CRT1/CRT2 isoforms and CRT3 remaining as CRT3.

Alignment of the putative maize CRT3 isoform with other plant CRT isoforms revealed that the sequence contains several features typical for CRT proteins, e.g. an ER signal sequence in the N terminus, three Cys residues important for the proper folding of the protein, the three tandem repeats in the P domain, and the ER retrieval signal in the C terminus (Fig. 2A; Michalak et al., 1999). Although the signal sequence for the maize CRT3 isoform is distinctly different compared with the other aligned isoforms (Fig. 2A), it does contain typical features for ER localization, i.e. positively charged amino acid(s) in close proximity of the N terminus, an aliphatic/hydrophobic stretch downstream of the positively charged amino acid(s), and a few polar amino acids together with an Ala/Leu immediately upstream of the cleavage site (von Heijne, 1985), suggesting proper ER targeting.

Examining the genomic organization of the CRT genes in Arabidopsis and rice showed that the structure of the gene is highly conserved (Fig. 3). The CRT3 genes in both Arabidopsis and rice have 14 exons, with high similarity in exon sizes. In contrast, the CRT1 and CRT2 in Arabidopsis consist of 12 and 13 exons, respectively, whereas the CRT1/CRT2 isoforms in rice consist of 14 exons. The best representation of an ancestral CRT gene, therefore, is provided by the CRT3 gene in higher plants. From the genomic sequences, it is also evident that the regions corresponding to the N and P domains of the protein show a high degree of conservation. In contrast, exons corresponding to the C domain are less well conserved. The rate of conservation among the exons is also reflected in the amino acid sequences, where the C domain is less conserved than the other domains. Apparently, the selection pressure is higher for the N and P domains, possibly due to structural or functional importance, compared with the C terminus.

It is believed that the main Ca2+-binding capacity of CRT proteins is given by the number of negatively charged amino acids in their C-terminal region (Baksh and Michalak, 1991). The differences in size and sequence among exons corresponding to the C terminus of the CRTs, therefore, imply differences in the efficiency of Ca2+ binding. When comparing the number of negatively charged amino acids in the C domain for the different isoforms, it is apparent that the CRT3 isoforms contain less acidic residues than both the CRT1 and CRT2 isoforms in all investigated species (37%, 35%, and 26% for Arabidopsis CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3, respectively). If the negatively charged residues truly correspond to the amount of Ca2+ that CRT can withhold, the CRT3 isoforms should have less overall effect on the ER Ca2+ levels. In addition, there are more ESTs corresponding to the isoforms in the CRT1/CRT2 isoform group. This supports CRT1 and CRT2 as being the major isoforms, possibly due to an enhanced Ca2+-binding efficiency, and may indicate a less dominant role for the CRT3 isoform in Ca2+ homeostasis.

Implications of the C domain sequence and length variations might also lie in its sensitivity to proteolytic activity. Earlier reports have shown that the C domain is sensitive to degradation, which might affect the subcellular location and functionality of CRTs (Corbett et al., 2000; Persson et al., 2002a). Therefore, the differences observed in the domain could affect both the stability of the protein, possibly functioning as a turnover mechanism, or as a switch for other subcellular localizations and interacting components of CRTs.

A close examination reveals that the last exon, containing 12 coding nucleotides, corresponds to the ER retrieval signal, important for the retention/retrieval of resident ER proteins (Gomord et al., 1999). Because the CRT protein also is suggested to be involved in processes occurring outside the ER, mechanisms to escape the ER retrieval machinery have been suggested (Baldan et al., 1996; Eggleton and Llewellyn, 1999). Also, as mentioned above, the sensitivity of the C domain to proteolytic activity could alter the localization of CRTs (Corbett et al., 2000). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate whether an alternative splice variant, lacking the HDEL signal, exists.

Here, we show that CRT1 and CRT2 were most abundant in floral, root, and leaf tissues, with a lower expression in stem tissues for both Arabidopsis and maize (Fig. 5B; data not shown). In contrast, CRT3 from Arabidopsis and maize showed highest expression in leaves and roots (Fig. 5, B and E). The higher relative expression of maize CRT3 in roots might be because the plants were soil grown, whereas the Arabidopsis plants were grown on liquid medium (compare Fig. 5, B with E). Earlier reports have shown that CRT, although present in various tissues in curled-leaf tobacco (Nicotiana plumbaginifolia; Borisjuk et al., 1998), Arabidopsis (Nelson et al., 1997), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; Denecke et al., 1995), and barley (Chen et al., 1994), was most abundant in floral tissues. Although none of the latter investigations have performed expression studies for the full set of CRT isoforms, the overall expression patterns reported here are consistent with these reports.

Members of the different isoform groups respond differently to applied external stimuli. Although the CRT3 was induced already after 30 min in response to salt or tunicamycin treatments, the CRT1 and CRT2 isoforms showed a slower induction in Arabidopsis. The faster response of the CRT3 isoform could be due to an overall low expression level of this isoform, implied by the small number of reported ESTs, and, therefore, lead to a compensatory upregulation of CRT3. Another plausible explanation would be that the different CRTs participate in different regulatory pathways and would support functional diversity among the CRT isoforms. A several-fold induction of the CRT2 gene was reported recently in response to both tunicamycin and dithiothreitol in Arabidopsis (Martinez and Chrispeels, 2003), supporting the up-regulation reported here.

Examining the amino acid sequences for potential posttranslational modifications revealed that the members from the two isoform groups in Arabidopsis contain different numbers of negatively charged amino acids and that there might be a difference in numbers of attached glycans in the CRTs. Here, we show that Arabidopsis CRTs contain differences in attached N-linked glycan moieties, potentially due to differences in numbers of N-linked glycans (Fig. 8). Both plant and mammalian CRTs can be glycosylated (Jethmalani et al., 1994; Navazio et al., 2002). Although the function of glycosylation of CRTs remains elusive, a potential role could be to mediate a redistribution of CRTs to other cellular compartments (Jethmalani et al., 1997). Furthermore, the structural composition of the attached glycans also corresponds to which compartments CRT has been translocated through, i.e. the complexity of the glycan is enhanced when modified by enzymes associated with the Golgi apparatus (Crofts et al., 1999; Pagny et al., 2000; Navazio et al., 2002). Therefore, the structures of the glycan moieties have been used to monitor if CRT can escape out of the ER in plants (Navazio et al., 2002). Because the glycosidase used in this study, PNGase F, removes N-linked glycans that lack a core α-(1,3) Fuc residue, it seems likely that the investigated CRTs did not translocate beyond the ER or cis-Golgi compartments (Pagny et al., 2000; Navazio et al., 2002).

In conclusion, together with the establishment of a second CRT isoform (Crt2) in animals (Persson et al., 2002b), the data presented here show that two distinct CRT forms are generally present in both animals and higher plants. In addition, differences in expression patterns, regulation, and posttranslational modifications support multifunctional roles of CRTs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Computational Analysis of CRT Protein Sequences

Protein sequences corresponding to different CRT isoforms were obtained from the Swissprot and GenBank databases via the NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, using BLASTP; Altschul et al., 1997). Sequences were compared within each species to eliminate incorrect or redundant entries. Multiple alignment of 18 CRT protein sequences was performed using ClustalW, the MacVector 7.0 software package. The alignment was carried out using the Blossum series matrix, with an open gap penalty of 10 and an extend gap penalty of 0.05, followed by manual adjustments. Heuristic searches using the maximum parsimony method were performed on the aligned sequences using the PAUP 4.0b8a software (Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers, Sunderland, MA), with tree bisection-reconnection branch-swapping algorithm and gaps treated as missing data. Alleloforms and protein sequences under 100 amino acids in length were excluded from the phylogenetic analysis. The CRT amino acid sequence from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (GenBank accession no. CAB54526) was used as the outgroup (phylum Chlorophyta). Support of the phylogeny was estimated using bootstrap analysis of 100 replicates with heuristic searches.

The Arabidopsis CRT2 and CRT3 sequences were used to obtain corresponding Brassica rapa ESTs using a BLASTN analysis (Altschul et al., 1997) via the NCBI. Only ESTs with scores higher than 200 and E values lower than 6e-65 were considered ESTs for putative CRT2 and CRT3 isoforms.

Sequence Comparison of CRT Proteins

Protein sequences corresponding to Arabidopsis CRT1, Arabidopsis CRT2, Arabidopsis CRT3, maize (Zea mays) CRT1, maize CRT2, and maize CRT3 (GenBank accession nos. AAC49695, AAK74014, AAC49697, CAA86728, AAF01470, and translated from nucleotide sequence AY105822, respectively), obtained from the GenBank database via the NCBI, were used for sequence analysis. A ClustalW multiple alignment of protein sequences was carried out as described above. The two conserved triplet regions, denoted I and II in the alignment (Fig. 2A), were obtained from Michalak et al. (1999) and correspond to PXXIXDPDAXKPEDWDE (three times) and GXWXPPXIXNPXYX (three times).

Exon/Intron Organization

Arabidopsis CRT exons were obtained at the NCBI. BLAST analyzes using Arabidopsis ESTs against the Arabidopsis genome at the NCBI were performed to retrieve genomic clones harboring the corresponding gene. The exon/intron organization was obtained by ClustalW pair-wise alignment of each CRT mRNA with corresponding genomic clone and subsequent manual adjustment. The same CRT mRNA sequences were used to confirm the genomic localization.

A rice (Oryza sativa) cDNA corresponding to CRT3 (GenBank Accession no. AP003316) was obtained performing BLASTN analysis at NCBI with the Arabidopsis CRT3 sequence against the nonredundant database with a rice limit. The obtained rice CRT1/CRT2 and CRT3 sequences were used to BLAST search the rice genome. Obtained genomic sequences (CRT1/CRT2, GenBank accession no. AAAA01007283; and CRT3, GenBank accession no. AAAA01001172) were aligned against available mRNA sequences and manually adjusted to obtain corresponding intron and exon organizations. Gene maps were drawn manually based on obtained exon and intron sizes.

Plant Material

B. rapa subsp. pekinensis plants were grown in a growth chamber with a 14-h-light/10-h-dark photoperiod at 22°C and 70% relative humidity until 5 weeks after germination. Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia-0 were grown on soil with a 10-h-light/14-h-dark photoperiod at 22°C and 70% humidity until 6 weeks after germination. The Arabidopsis plants were then transferred to a greenhouse with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod until flowering was obtained. Arabidopsis roots and Arabidopsis plants for stress-related experiments were obtained from Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia-0 and grown on Murashige and Skoog liquid medium with a 14-h-light/10-h-dark photoperiod at 22°C and 70% relative humidity until 6 weeks after germination. Arabidopsis cell cultures were maintained in 25 mL of liquid culture medium (Gamborg B5 salts, 15 g L–1 Suc, 0.1 mg L–1 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, 1 mg L–1 kinetin, and 2 mm KH2PO4 [pH 5.7]) at 22°C with gyratory shaking at 150 rpm in continuous light. Cells were subcultured weekly with a 10% (v/v) inoculum. Maize cv Pioneer 3183 plants were grown in soil in a greenhouse supplemented with lights as previously described (Perera et al., 1999). Six-week-old plants were used for RNA isolation. For endosperm samples, variety W64A+ kernels were harvested 18 d after pollination during the summer of 2002.

Stress Experiments

Arabidopsis plants, grown on liquid medium, were treated with either 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm EGTA, 15 μg mL–1 tunicamycin, and 100 μm ABA or subjected to drought (plants removed from liquid medium). To avoid responses to fresh medium, respective treatments were added to medium that had been changed 4 d earlier. Treatments were terminated after 2 h, and plants were harvested into liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C. Water or methanol (solvent for tunicamycin and ABA) were used as control treatments.

For the Arabidopsis suspension cultures, cells were harvested 4 d after inoculation into new medium and treated with 150 mm NaCl, 15 μg mL–1 tunicamycin, or 100 μm ABA. Flasks contained approximately 8 g of cells per 50 mL of inoculum when treatments were initiated. Five milliliters was removed after 30-min and 4- and 12-h treatments from each flask. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (250g) for 2 min, immersed into liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80°C.

Cloning and Northern-Blot Analysis

B. rapa leaves were harvested 5 weeks after germination, and total RNA was prepared using a conventional phenol/chloroform extraction. Total RNA was used as template for reverse transcriptase-PCR, using a primer designed against putative CRT3 ESTs for the 5′ end (5′-ATGAGATTAA CCCAAAACAAGC-3′) and an oligo(dT15) primer (Boehringer Mannheim Scandinavia AB, Bromma, Sweden) for the 3′ end. A QIAGEN OneStep RT-PCR kit (QIAGEN, Merck Eurolab AB, Spånga, Sweden) was used for the first strand synthesis and subsequent PCR step. Obtained products were separated on a 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel. The putative CRT3 fragment was excised and sequenced for identification.

Total RNA was obtained using a conventional chloroform/phenol extraction from either 5-week-old leaves from B. rapa or various tissues from Arabidopsis grown for 10 weeks and from Arabidopsis cell cultures. During total RNA preparation from Arabidopsis flowers, 2 mm dithiothreitol was included during the extraction step. The RNA was separated using an agarose/formaldehyde gel and blotted to a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala). For maize, tissues were excised from 6- to 7-week-old maize plants. The upper portions of the maize plants were harvested and frozen in liquid N2. Then, roots were removed from the soil, washed in water, excised, and frozen in liquid N2. Samples were stored at –80°C, and total RNA was extracted by using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The RNAs were separated in a formaldehyde-containing gel (1.5% [w/v] agarose, 40 mm triethanolamine, and 2 mm Na2EDTA). The RNAs were transferred from the gel to a nylon membrane (Osmonics, Minnetonka, MN) and immobilized on the membrane using UV cross-linking (UV Stratalinker, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). cDNA clones harboring Arabidopsis CRT1, CRT2, CRT3, and maize CRT1/2 were used as full-length probes. A 101-nucleotide sequence corresponding to the 3′ UTR for maize CRT3 (corresponding to 5′-CTATAAAAGTCCCCAAATATTGCATTCCTCAAAAGCATAAGCTGGAAGTTGCTTCGGACATTGTGGGTGCTTTTCAATAATAATAATTGATTCGCCTGGTCAGAA-3′) was obtained from MWG Biotech and used as isoform-specific probe. Because the maize CRT1 and CRT2 isoforms are 98% identical on a nucleotide level (UTRs included), we were unable to generate specific probes for these isoforms. Probes were radiolabeled using the Rediprime II kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Cross-hybridizations among probes were investigated by dot-blotting 100 ng of either probe, or for the B. rapa control, 100 ng of the cloned CRT3 isoform, onto a Hybond-N+ membrane. The membranes were subsequently hybridized with each probe in parallel with the membranes containing the separated RNA to be investigated. Hybridization was carried out using ExpressHyb Hybridization Solution (CLONTECH Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA), essentially according to the manufacturer's protocol. A radiolabeled cDNA corresponding to 26S rRNA was used as a control.

Analysis of N-Linked Glycans

Arabidopsis CRT1, CRT2, and CRT3 protein sequences were analyzed using the MacVector 7.0 software. Six-week-old greenhouse-grown Arabidopsis plants were homogenized using a tight-fitting glass-glass homogenizer in 200 mm Suc, 25 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.0), 3 mm EGTA, 1 mm MgSO4, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 mm dithiothreitol. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was used for glycosidase analysis, SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting. Recombinant PNGase F (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) was used for the N-linked glycosidase treatment. Deglycosidation was carried out essentially according to the manufacturer's protocol under native conditions.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

The Arabidopsis homogenate was solubilized by the addition of one-third of 3.33× sample buffer (250 mm Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 6% [w/v] SDS, 33% [v/v] glycerol, 15% [v/v] β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.02% [w/v] bromphenol blue). Equal amounts of solubilized proteins were separated on a 10% (w/v) Laemmli SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Gels were either stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or transferred to a hydrophobic polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Immobilon-P Transfer membrane, Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA). Proteins were wet blotted at 100 V for 1 h. After transfer, the blotting membranes were blocked with 4% (w/v) blocking reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) in Tris-buffered saline with 0.2% (v/v) Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were incubated with either an antiserum against CRT from maize diluted 1:5,000 (v/v) or an antiserum against calnexin from Arabidopsis diluted 1:1000 (v/v). Polyclonal antibodies were raised against a purified deglycosylated maize CRT, essentially described by Pagny et al. (2000). Immunodecoration was visualized with chemiluminescent detection of horseradish peroxidase according to the ECL western detection reagent protocol (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Distribution of Materials

Upon request, all novel materials described in this publication will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Donald P. Shepley and Hans Bohnert for supplying us with the Arabidopsis CRT1 and CRT3 clones. We thank Dr. Neil E. Hoffman for supplying the Arabidopsis calnexin antibodies, Dr. Steve Huber for supplying the maize plants, Drs. Rebecca S. Boston and Jeff Gillikin for the maize endosperm. and Dr. Eric Ruelland for supplying us with Arabidopsis suspension cells. We also thank Mrs. Adine Karlsson for supplying hydro-ponic Arabidopsis material and Mr. Magnus Alsterfjord and Drs. Urban Johanson and Jenny Xiang for valuable suggestions.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.103.024943.

This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento CientR fico e Tecnológico, Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologica (Brazil; fellowship to R.G.), in part by The Swedish Research Council (grant to M.S.), and in part by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the National Science Foundation (grant to W.F.B.).

References

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaudeau S, Frieden M, Nakamura K, Castelbou C, Michalak M, Demaurex N (2002) Calreticulin differentially modulates calcium uptake and release in the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. J Biol Chem 277: 46696–46705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baksh S, Michalak M (1991) Expression of calreticulin in Escherichia coli and identification of its Ca2+ binding domains. J Biol Chem 266: 21458–21465 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldan B, Navazio L, Friso A, Mariani P, Meggio F (1996) Plant calreticulin is specifically and efficiently phosphorylated by protein kinase CK2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 221: 498–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluska F, Samaj J, Napier R, Volkmann D (1999) Maize calreticulin localizes preferentially to plasmodesmata in root apex. Plant J 19: 481–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisjuk N, Sitailo L, Adler K, Malysheva L, Tewes A, Borisjuk L, Manteuffel R (1998) Calreticulin expression in plant cells: developmental regulation, tissue specificity and intracellular distribution. Planta 206: 504–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer K (2002) Gondwanan evolution of the grass alliance of families (Poales). Evol Int J Org Evolution 56: 1374–1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho P, Lechleiter JD (1995) Calreticulin inhibits repetitive intracellular Ca2+ waves. Cell 82: 765–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Hayes PM, Mulrooney DM, Pan A (1994) Identification and characterization of cDNA clones encoding plant calreticulin in barley. Plant Cell 6: 835–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett EF, Michalak KM, Oikawa K, Johnson S, Campbell ID, Eggleton P, Kay C, Michalak M (2000) The conformation of calreticulin is influenced by the endoplasmic reticulum luminal environment. J Biol Chem 275: 27177–27185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan SJ, Hastings C, Winfrey R Jr (1997) Cloning and characterization of the calreticulin gene from Ricinus communis L. Plant Mol Biol 34: 897–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofts AJ, Denecke J (1998) Calreticulin and calnexin in plants. Trends Plant Sci 3: 396–399 [Google Scholar]

- Crofts AJ, Leborgne-Castel N, Hillmer S, Robinson DG, Phillipson B, Carlsson LE, Ashford DA, Denecke J (1999) Saturation of the endoplasmic reticulum retention machinery reveals anterograde bulk flow. Plant Cell 11: 2233–2248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denecke J, Carlsson LE, Vidal S, Hoglund AS, Ek B, van Zeijl MJ, Sinjorgo KM, Palva ET (1995) The tobacco homolog of mammalian calreticulin is present in protein complexes in vivo. Plant Cell 7: 391–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggleton P, Llewellyn DH (1999) Pathophysiological roles of calreticulin in autoimmune disease. Scand J Immunol 49: 466–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan TH, Presting G, Wang R, Dunn M, Glazebrook J, Sessions A, Oeller P, Varma H et al. (2002) A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica). Science 296: 92–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomord V, Wee E, Faye L (1999) Protein retention and localization in the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus. Biochimie 81: 607–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadlington JL, Denecke J (2000) Sorting of soluble proteins in the secretory pathway of plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 3: 461–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan AM, Wesson C, Trumble WR (1995) Calreticulin is the major Ca2+ storage protein in the endoplasmic reticulum of the pea plant (Pisum sativum). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 211: 54–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert DN, Foellmer B, Helenius A (1996) Calnexin and calreticulin promote folding, delay oligomerization and suppress degradation of influenza hemagglutinin in microsomes. EMBO J 15: 2961–2968 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann I, Shin J, Huang J, Perera IY, Davies E (2001) Transient dissociation of polyribosomes and concurrent recruitment of calreticulin and calmodulin transcripts in gravistimulated maize pulvini. Plant Physiol 127: 1193–1203 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaubert S, Ledger TN, Laffaire JB, Piotte C, Abad P, Rosso MN (2002) Direct identification of stylet secreted proteins from root-knot nematodes by a proteomic approach. Mol Biochem Parasitol 121: 205–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jethmalani SM, Henle KJ, Gazitt Y, Walker PD, Wang SY (1997) Intracellular distribution of heat-induced stress glycoproteins. J Cell Biochem 66: 98–111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jethmalani SM, Henle KJ, Kaushal GP (1994) Heat shock-induced prompt glycosylation: identification of P-SG67 as calreticulin. J Biol Chem 269: 23603–23609 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Michalak M, Opas M, Eggleton P (2001) The ins and outs of calreticulin: from the ER lumen to the extracellular space. Trends Cell Biol 11: 122–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski BA, Zielinska-Kwiatkowska AG, Migdalski A, Kleczkowski LA, Wasilewska LD (1995) Cloning of two cDNAs encoding calnexin-like and calreticulin-like proteins from maize (Zea mays) leaves: identification of potential calcium-binding domains. Gene 165: 219–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Komatsu S (2000) Molecular cloning and characterization of calreticulin, a calcium-binding protein involved in the regeneration of rice cultured suspension cells. Eur J Biochem 267: 737–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez IM, Chrispeels MJ (2003) Genomic analysis of the unfolded protein response in Arabidopsis shows its connection to important cellular processes. Plant Cell 15: 561–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka K, Seta K, Yamakawa Y, Okuyama T, Shinoda T, Isobe T (1994) Covalent structure of bovine brain calreticulin. Biochem J 298: 435–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak M, Corbett EF, Mesaeli N, Nakamura K, Opas M (1999) Calreticulin: one protein, one gene, many functions. Biochem J 344: 281–292 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Zuppini A, Arnaudeau S, Lynch J, Ahsan I, Krause R, Papp S, De Smedt H, Parys JB, Müller-Esterl W et al. (2001) Functional specialization of calreticulin domains. J Cell Biol 154: 961–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navazio L, Baldan B, Dainese P, James P, Damiani E, Margreth A, Mariani P (1995) Evidence that spinach leaves express calreticulin but not calsequestrin. Plant Physiol 109: 983–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navazio L, Miuzzo M, Royle L, Baldan B, Varotto S, Merry AH, Harvey DJ, Dwek RA, Rudd PM, Mariani P (2002) Monitoring endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi traffic of a plant calreticulin by protein glycosylation analysis. Biochemistry 41: 14141–14149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D, Glaunsinger B, Bohnert HJ (1997) Abundant accumulation of the calcium-binding molecular chaperone calreticulin in specific floral tissues of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 114: 29–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagny S, Cabanes-Macheteau M, Gillikin JW, Leborgne-Castel N, Lerouge P, Boston RS, Faye L, Gomord V (2000) Protein recycling from the Golgi apparatus to the endoplasmic reticulum in plants and its minor contribution to calreticulin retention. Plant Cell 12: 739–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera IY, Heilmann I, Boss WF (1999) Transient and sustained increases in inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate precede the differential growth response in gravistimulated maize pulvini. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 5838–5843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson S, Love J, Tsuo PL, Robertson D, Thompson WF, Boss WF (2002a) When a day makes a difference: interpreting data from endoplasmic reticulum-targeted green fluorescent protein fusions in cells grown in suspension culture. Plant Physiol 128: 341–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson S, Rosenquist M, Sommarin M (2002b) Identification of a novel calreticulin isoform (Crt2) in human and mouse. Gene 297: 151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson S, Wyatt SE, Love J, Thompson WF, Robertson D, Boss WF (2001) The Ca2+ status of the endoplasmic reticulum is altered by induction of calreticulin expression in transgenic plants. Plant Physiol 126: 1092–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Ihara Y, Leach MR, Cohen-Doyle MF, Williams DB (1999) Calreticulin functions in vitro as a molecular chaperone for both glycosylated and non-glycosylated proteins. EMBO J 18: 6718–6729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Chase DW (1999) Angiosperm phylogeny inferred from multiple genes as a tool for comparative biology. Nature 402: 402–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vision TJ, Brown DG, Tanksley SD (2000) The origins of genomic duplications in Arabidopsis. Science 290: 2114–2117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G (1985) Signal sequences, The limits of variation. J Mol Biol 184: 99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt SE, Tsou PL, Robertson D (2002) Expression of the high capacity calcium-binding domain of calreticulin increases bioavailable calcium stores in plants. Transgenic Res 11: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Hu S, Wang J, Wong GK, Li S, Liu B, Deng Y, Dai L, Zhou Y, Zhang X et al. (2002) A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica). Science 296: 79–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]