Abstract

The opportunistic human fungal pathogen Candida glabrata is confronted with phagocytic cells of the host defence system. Survival of internalized cells is thought to contribute to successful dissemination. We investigated the reaction of engulfed C. glabrata cells using fluorescent protein fusions of the transcription factors CgYap1 and CgMig1 and catalase CgCta1. The expression level and peroxisomal localization of catalase was used to monitor the metabolic and stress status of internalized C. glabrata cells. These reporters revealed that the phagocytosed C. glabrata cells were exposed to transient oxidative stress and starved for carbon source. Cells trapped within macrophages increased their peroxisome numbers indicating a metabolic switch. Prolonged phagocytosis caused a pexophagy-mediated decline in peroxisome numbers. Autophagy, and in particular pexophagy, contributed to survival of C. glabrata during engulfment. Mutants lacking CgATG11 or CgATG17, genes required for pexophagy and non-selective autophagy, respectively, displayed reduced survival rates. Furthermore, both CgAtg11 and CgAtg17 contribute to survival, since the double mutant was highly sensitive to engulfment. Inhibition of peroxisome formation by deletion of CgPEX3 partially restored viability of CgATG11 deletion mutants during engulfment. This suggests that peroxisome formation and maintenance might sequester resources required for optimal survival. Mobilization of intracellular resources via autophagy is an important virulence factor that supports the viability of C. glabrata in the phagosomal compartment of infected innate immune cells.

Introduction

Candida glabrata belongs to the diverse group of human fungal pathogens and is phylogenetically closely related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Kaur et al., 2005, Marcet-Houben and Gabaldon, 2009). The high similarity of C. glabrata to S. cerevisiae suggests that also for fungi, relatively small genetic changes may be sufficient for adaptation to a pathogenic lifestyle (Dujon et al., 2004). C. glabrata is a common commensal, but can turn into an opportunistic pathogen with a rising frequency of isolates among immunocompromised patients and elder people (Li et al., 2007; Pfaller and Diekema, 2007; Presterl et al., 2007). In the host environment, C. glabrata has to evade or survive attacks of the cell-mediated immune system (Nicola et al., 2008). Counterstrategies of fungal pathogens differ between species. Candida albicans destroys macrophages by hyphal outgrowth. Alternatively, Cryptococcus neoformans either lyses macrophages or escapes via phagosomal extrusion (Alvarez and Casadevall, 2006; Ma et al., 2006). C. glabrata engulfed by macrophages do not undergo morphological transitions such as C. albicans (Leberer et al., 2001). An open question concerns how C. glabrata is coping with cells of the immune system, such as macrophages.

The phagosome is a hostile environment for fungi (reviewed in Nicola et al., 2008). After internalization of microbial cells, the organelle maturates into the phagolysosome containing mature hydrolytic enzymes and a more acidic pH 4.5–5.5 (Geisow et al., 1981; Levitz et al., 1999). Additionally, the NADPH oxidase complex generates reactive oxidative species to attack internalized microorganisms (for review see Romani, 2004; Segal, 2005). Thus, commensal and pathogenic fungi are exposed to reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by polymorphonuclear leucocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells (Miller and Britigan, 1997; Missall et al., 2004; Gildea et al., 2005). On the fungal side, antioxidant defence enzymes such as catalase, superoxide dismutase, thioredoxin- and glutathione-dependent peroxidases and reductases guard against oxidative stress and are thus considered virulence factors (Johnson et al., 2002; Cox et al., 2003; Missall et al., 2004; Chaves et al., 2007). Oxidative stress as defence strategy is not restricted to combat fungal infections. Invading bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, or the malaria parasites Plasmodium sp., face ROS stress upon engulfment (Becker et al., 2004; Voyich et al., 2005). ROS sensed by microbes act also as signalling molecules. The C. albicans catalase, an enzyme which decomposes hydrogen peroxide, has been investigated more closely. C. albicans induces catalase when engulfed in neutrophils or in macrophages (Rubin-Bejerano et al., 2003; Lorenz et al., 2004; Enjalbert et al., 2007). Moreover, hydrogen peroxide promotes the morphological transition of C. albicans cells to hyphal growth, a form invading the host tissue (Nakagawa, 2008; Nasution et al., 2008). Finally, C. albicans devoid of catalase was eliminated more efficiently in a mouse infection model (Nakagawa et al., 2003). The filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus lacking the catalases expressed in the mycelium exhibited delayed infection in a rat model of invasive aspergillosis (Paris et al., 2003). In contrast, C. glabrata catalase was not a virulence determinant in an immunocompromised mouse model (Cuellar-Cruz et al., 2008). In mice infected with a C. neoformans mutant devoid of all four catalases, mortality was unchanged (Giles et al., 2006). Thus the relative importance of individual ROS scavenging enzymes varies between fungal pathogens.

Besides being exposed to oxidative stress, cells engulfed by macrophages adjust their metabolic programme (Fan et al., 2005; Barelle et al., 2006). Engulfed C. albicans cells induce many genes involved in non-fermentative carbon metabolism (Prigneau et al., 2003; Lorenz et al., 2004). Phagocytosed C. glabrata induces genes encoding enzymes involved in β-oxidation, the glyoxylate cycle and gluconeogenesis (Kaur et al., 2007). Moreover, the glyoxylate cycle, which is required to channel fatty acid-derived two carbon units into metabolism, was early recognized as a virulence determinant for C. albicans (Lorenz and Fink, 2001). Other human fungal pathogens also induce glyoxylate cycle components during infection conditions (Rude et al., 2002; Canovas and Andrianopoulos, 2006; Derengowski et al., 2008). However, A. fumigatus and C. neoformans do not require the glyoxylate cycle for virulence (Idnurm et al., 2007; Schöbel et al., 2007). Some of the enzymes of the glyoxylate cycle are localized in the peroxisomal matrix (for review see, e.g. Kunze et al., 2006). Peroxisomes are inducible, single-membrane organelles which harbour enzymes for the oxidative catabolism of fatty acids, the glyoxylate cycle and others. Generally, peroxisome number and size vary according to metabolic needs (for review see Yan et al., 2005; Platta and Erdmann, 2007).

Autophagy continuously recycles almost all constituents of the cell (for review see Mizushima and Klionsky, 2007; Kraft et al., 2009). Different types of autophagy help organisms to overcome periods of nutrient starvation by recycling intracellular components to sustain vital cellular functions. It seems to be linked to the unique niches and morphology of fungal pathogens (for review see Palmer et al., 2008). For certain pathogenic fungi, autophagy has been identified as a virulence factor. C. neoformans requires an intact autophagy pathway during infection (Hu et al., 2008). Peroxisomes and their contents are delivered to the vacuole by the pexophagy pathway, a specialized form of autophagy (Guan et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2001; Farre and Subramani, 2004). In S. cerevisiae selective pexophagy is dependent on Atg11 and partly on Atg17 which is also important for non-selective autophagy (Cheong et al., 2005; Yorimitsu and Klionsky, 2005).

Here we investigated responses of C. glabrata during its encounter with the macrophage phagosome compartment from which it cannot escape. We developed in vivo reporters to track fungal responses to this environment. To detect oxidative and glucose starvation stress of cells, we used fluorescent protein fusions of the C. glabrata orthologues of the S. cerevisiae transcription factors Yap1 and Mig1 (Kuge et al., 1997; Carlson, 1999). We found the C. glabrata catalase gene CgCTA1 and catalase activity regulated by oxidative stress and glucose starvation. Additionally, we demonstrated GFP–CgCta1 localization to peroxisomes. C. glabrata peroxisomes have not been described so far and were here defined by several independent criteria. We found that C. glabrata cells engulfed by mouse macrophages experience a mild oxidative stress and sustained carbon starvation. Additionally, peroxisomes became transiently induced in engulfed cells. We explored the role of peroxisomes with various mutants lacking peroxisome biogenesis or autophagy pathways mediating destruction of peroxisomes. We report here that autophagy and, surprisingly, pexophagy is a likely virulence factor for C. glabrata. Mutants lacking CgAtg11 and/or CgAtg17 were killed more efficiently by macrophages during engulfment. Thus, for engulfed C. glabrata cells, nutrient deprivation represents a serious challenge and mobilization of intracellular resources via autophagy is a major contributor to sustain viability.

Results

C. glabrata catalase CgCta1 is induced by hydrogen peroxide and carbon starvation

Candida glabrata harbours one catalase gene (CgCTA1, CAGL0K10868g), related to the yeast peroxisomal catalase CTA1 gene. The two catalase genes of S. cerevisiae are regulated differently. CTT1, coding for the cytoplasmic catalase, is induced by stress conditions (Marchler et al., 1993). The CTA1 gene is expressed only during growth on non-fermentable carbon sources (Cohen et al., 1985; Hartig and Ruis, 1986). To find out the regulatory pattern of the C. glabrata catalase, we assayed its activity in crude protein extracts from cells grown either on glucose or on a non-fermentable carbon source. Cells adapting to ethanol as carbon source showed a substantial induction of catalase activity (Fig. 1A). Moreover, mild oxidative stress of 0.4 mM H2O2 induced C. glabrata catalase activity about 10-fold suggesting regulation by both glucose starvation and oxidative stress (Fig. 1B). To verify if the CgCTA1 gene encodes the only catalase activity in C. glabrata, we replaced the open reading frame (ORF) with the S. cerevisiae URA3 gene (Fig. S1). Catalase activity was undetectable in extracts derived from the mutant strain (Fig. 1A and B). A centromeric plasmid (pCgCTA1) harbouring the CgCTA1 ORF including a 1.8 kb upstream region fully restored wild-type level catalase activity to the cta1Δ mutant (Fig. 1A and B). To demonstrate that the regulation of catalase activity occurs at the level of transcription, CgCTA1 mRNA levels were analysed from cells shifted to medium lacking glucose or exposed to 0.4 mM H2O2. Glucose-starved cells displayed a continuous increase of CgCTA1 mRNA immediately after shift to glucose-free medium (Fig. 1C). Hydrogen peroxide stress caused a rapid increase within 10 min. Taken together, regulation of the C. glabrata catalase gene CgCTA1 by carbon source availability and oxidative stress combines elements of both S. cerevisiae catalases.

Fig. 1.

Oxidative stress and carbon source stress regulate C. glabrata catalase CgCTA1. A. To measure catalase activity upon glucose depletion, cells were grown to log phase in YPD and shifted to medium with 2% or 0.1% glucose and grown for 4 h. Catalase activity was determined as described in Experimental procedures. B. Cells were incubated in YPD with 0.4 mM H2O2 for 45 min. Crude cell extracts were prepared and then assayed for catalase activity. C. Northern blot analysis of CgCTA1 mRNA levels from wild type, ARCg cta1Δ mutant and complemented mutant strain was performed under stress conditions (glucose starvation, 0.4 mM H2O2). Samples were taken at the indicated time points. CgACT1 mRNA levels were used as loading control. mRNA levels were visualized by hybridization of radioactive probes and autoradiography. The pCgC–GFP–CgCTA1 construct with GFP inserted at the N-terminus is illustrated. D. C. glabrata ARCg cta1Δ mutant complemented with pGFP–CgCTA1, pCgCTA1 or an empty plasmid was grown in synthetic medium to log phase, adjusted to 105 cells ml−1 and exposed to indicated doses of hydrogen peroxide. Optical density after 24 h of incubation at 37°C is indicated.

CgCta1 confers hydrogen peroxide stress resistance

The similarity of the CgCTA1 gene to the S. cerevisiae CTA1 gene suggested its peroxisomal localization. To clarify the intracellular localization, we fused a green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the CgCta1 N-terminus (GFP–CgCTA1) to preserve the putative peroxisomal targeting sequence 1 (PTS1) (Fig. 1C, lower panel). The preceding 1.8 kb of the CgCTA1 5′ untranslated region conferred a wild type-like expression pattern in hydrogen peroxide-stressed cells (Fig. 1C). Basal catalase activity of GFP–CgCta1 was detectable in unstressed cells, whereas hydrogen peroxide stress-induced activity was reduced to about 20% of the wild-type level (Fig. 1B).

We assessed if the reduced activity of GFP–Cta1 interferes with hydrogen peroxide stress resistance. C. glabrata cta1Δ mutant cells transformed with either pGFP–CgCTA1, pCgCTA1 or the empty plasmid (pACT) were grown in synthetic medium, the cultures were split and one part treated with 0.4 mM H2O2. Both were subsequently exposed to higher doses of hydrogen peroxide. Growth was scored after 24 h (Fig. 1D). The cta1Δ mutant cells containing the empty plasmid failed to grow in medium containing 5 mM H2O2. In contrast, the strain carrying the pCgCTA1 plasmid was resistant to medium supplemented with up to 20 mM H2O2, whereas pre-incubation with 0.4 mM H2O2 pushed the growth limit to 40 mM H2O2, similar to the wild-type parent strain (ΔHTU). Cells expressing the GFP–CgCta1 derivative displayed lower basal resistance. However, naïve cells without pre-treatment tolerated 5 mM H2O2 and failed to grow only at about 20 mM H2O2. Pre-treatment with 0.4 mM H2O2 shifted tolerance to about 30 mM H2O2. Thus, the GFP-tagged CgCta1 derivative, when compared with the untagged version, conferred resistance to oxidative stress to reduced but overall high level. These results suggested that H2O2 stress resistance of strains carrying the plasmid-encoded catalase derivatives encompasses the oxidative stress load of 0.4 mM H2O2 determined for the in vivo situation (Enjalbert et al., 2007). Our data also showed that the C. glabrata strains tolerated a substantial higher oxidative stress load compared with S. cerevisiae laboratory strains, which failed to grow at concentrations higher than 3 mM H2O2 (Davies et al., 1995; Cuellar-Cruz et al., 2008).

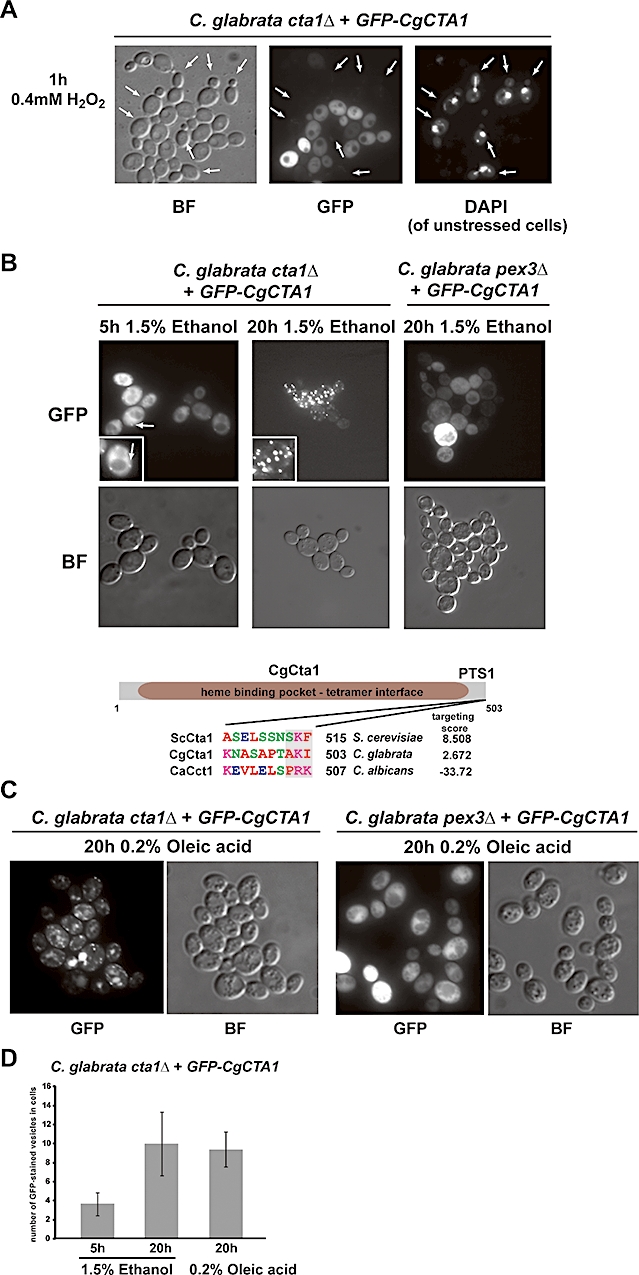

Localization of GFP–CgCta1 is dependent on the carbon source

Cells expressing GFP–CgCTA1 were exposed to different stress conditions. In rich medium, GFP–CgCta1 fluorescence was hardly detectable, reflecting its low basal expression of CgCTA1. Oxidative stress caused induction of the GFP–CgCta1 fluorescence signal. To compare different expression levels directly, unstressed cells were marked by staining their nucleic acids with DAPI. For microscopy these marked unstressed cells were mixed to cells from the same culture treated for 1 h with 0.4 mM H2O2. The micrograph demonstrates induction of the fusion protein by oxidative stress and its initial localization in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A). GFP–CgCTA1 became also induced after the glucose concentration in the growth medium dropped below 0.03% (Fig. S2A). We then investigated GFP–CgCta1 distribution in cells growing on non-fermentable carbon sources. Cells expressing GFP–CgCTA1 were grown in medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose and 1.5% ethanol. After 5 h, glucose was exhausted, and cells were switching to the non-fermentable carbon source. (Fig. 2B, left panel). Although the vast majority of GFP–CgCta1 was still located in the cytoplasm, small vesicles accumulating catalase became visible (see insert). After 20 h, almost all GFP–CgCta1 was accumulated in vesicular structures (Fig. 2B, middle panel).

Fig. 2.

Intracellular localization of C. glabrata catalase. A. Localization of GFP–CgCta1 was determined by fluorescence microscopy in ARCg cta1Δ cells transformed with pCgCTA1–GFP–CgCTA1. Cells were incubated for 1 h after induction of oxidative stress with 0.4 mM H2O2. Unstressed cells were stained with DAPI (2 μg ml−1) for 10 min. Aliquots of both cultures were pooled prior to microscopy. White arrows indicate unstressed cells. B. ARCg cta1Δ and ARCg pex3Δ mutant strains transformed with pCgC–GFP–CgCTA1 were grown in synthetic medium with 0.5% glucose and 1.5% ethanol for 20 h. White arrows indicate vesicular structures. Inserts show enlarged pictures of single cells. Possible peroxisomal targeting signals 1 (PTS1) detected at the C-terminus of CgCta1, ScCta1 and CaCct1 (Q6FM56, P15202, Q5AAT2; Neuberger et al., 2003). C. Fluorescence signals of strains as in (B) after growth in medium with 0.2% oleic acid for 20 h. D. Number of peroxisomes in C. glabrata cells during growth with ethanol (1.5%) and oleic acid (0.2%) as main carbon source.

CgCta1 can localize to peroxisomes

We suspected that the vesicles accumulating GFP–CgCta1 were peroxisomes. The PTS1 of CgCta1 was a boundary case compared with S. cerevisiae Cta1 (Fig. 2B, lower panel). To interfere with C. glabrata peroxisome assembly, we chose to eliminate the CgPEX3 gene (CAGL0M01342g). The S. cerevisiae orthologue Pex3 has an essential function for peroxisome biogenesis (Hohfeld et al., 1991). The CgPEX3 ORF was replaced with the ScURA3 gene and the correct integration was tested by Southern blot (Fig. S1). In these pex3Δ mutant cells, GFP–CgCta1 remained distributed in the cytoplasm, even in 1.5% ethanol grown cells (Fig. 2B, right panel). With oleic acid as sole carbon source, S. cerevisiae cells increase number and size of peroxisomes (Thieringer et al., 1991). GFP–CgCta1 accumulated in vesicles in cells growing in medium containing 0.2% oleic acid, whereas in pex3Δ mutant cells fluorescence was dispersed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2C). The number of stained vesicles also increased substantially in cells growing on a non-fermentative carbon source (1.5% ethanol) (Fig. 2D). These data suggest that C. glabrata accumulates GFP–CgCta1 in CgPex3-dependent structures resembling peroxisomes.

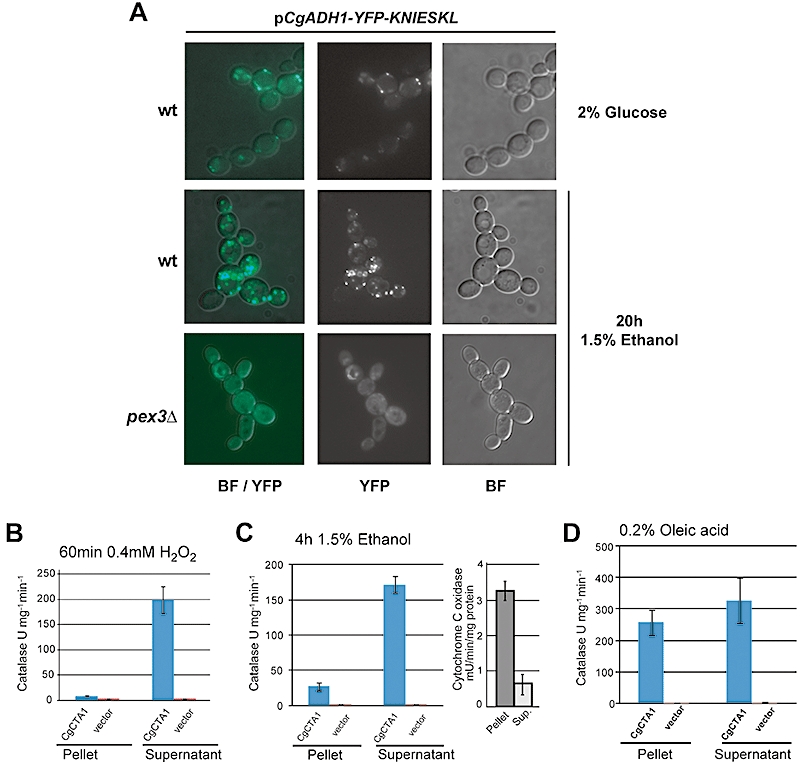

To visualize peroxisomal structures in C. glabrata, we fused a generic peroxisomal targeting signal peptide (KNIESKL) derived from the S. cerevisiae citrate synthase to the C-terminus of YFP (Lewin et al., 1990; Kragler et al., 1993). The YFP–KNIESKL fusion gene expression was driven by the strong CgADH1 promoter. YFP fluorescence marked peroxisomes, which increased their number during growth on ethanol (Fig. 3A, upper panel) and were absent in pex3Δ mutant cells (Fig. 3A, lower panel). This result confirmed the requirement of CgPex3 for C. glabrata peroxisome biogenesis.

Fig. 3.

CgCta1 localizes to peroxisomes upon glucose depletion. A. C. glabrataΔHTU and ARCg pex3Δ mutant cells expressing YFP–KNIESKL driven by the CgADH1 promoter were grown in synthetic medium with 2% glucose or 1.5% ethanol for 20 h. Localization of YFP was recorded by fluorescence microscopy and bright field (BF) microscopy. An overlay of YFP and BF microscopy is shown in the left panel. B. The ARCg cta1Δ strain carrying pCgC–CgCTA1 was exposed for 1 h to oxidative stress (0.4 mM H2O2). Pellets containing mitochondria and small organelles and post-mitochondrial supernatants were assayed for catalase activity. C. The same strain was grown in synthetic medium with 1.5% ethanol for 20 h. Catalase activity was measured in pellets and supernatants. Activity of cytochrome c oxidase was measured in pellet and supernatant fractions as described in Experimental procedures (right panel). D. Catalase activity in pellets and supernatant fraction collected from ARCg cta1Δ containing pCgC–CgCTA1 grown in synthetic medium with 0.2% oleic acid for 20 h.

The above results indicated a partial organellar localization of catalase, depending on the type of carbon source. To show this, we prepared cell extracts of cta1Δ mutant cells expressing CgCTA1. We separated these in an organellar pellet and a cytosolic supernatant fraction by centrifugation and tested the fractions for catalase activity. After oxidative stress, the entire induced catalase activity was found in the cytoplasmic supernatant (Fig. 3B). In extracts from cells growing with ethanol as main carbon source, catalase activity was found in the cytosolic supernatant, but about one-fourth of total activity was present in the pellet fraction (Fig. 3C, left panel). To confirm that the pellet fraction contained organelles, we used cytochrome c oxidase activity as marker enzyme for mitochondria. Most of the cytochrome c oxidase activity was found in the pellet fraction (Fig. 3C, right panel). Separation of extracts derived from cells grown in medium containing 0.2% oleic acid showed a further shift of catalase activity towards the pellet fraction (Fig. 3D). Activity of CgCta1 in the various fractions was distributed corresponding to the previously observed intracellular localization of GFP–CgCta1. Together, these results showed a dual localization of C. glabrata catalase depending on the presence of peroxisomes.

Phagocytosis induces GFP–CgCta1 expression

Fungal pathogens are exposed to a stressful environment, when they come into contact with phagocytic cells (Nicola et al., 2008). The regulation and localization of GFP–CgCta1 made it useful to report the environmental conditions during phagocytosis. C. glabrata cta1Δ mutant cells expressing GFP–CgCTA1 grown to exponential phase were used for infection of primary mouse macrophages. We used time-lapse live microscopy to follow the fate of individual engulfed cells (Fig. 4A). Freshly phagocytosed C. glabrata cells reacted to this environment with a detectable GFP–CgCta1 fluorescence signal within 40 min (Fig. 4A and Fig. S2C). Furthermore, during prolonged phagocytosis, GFP–CgCta1 accumulated in peroxisomes. To support the idea of peroxisome proliferation during phagocytosis, we followed localization of the YFP–KNIESKL fusion protein during infection of macrophages. Cells were fixed and stained for microscopy immediately after infection and after 2.5, 5, 10 and 24 h (Fig. 4B). We counted cells with visible peroxisomes per macrophage at various time points (Fig. 4C, left panel; Fig. S3). The number of cells with peroxisomes and the number of peroxisomes within these cells transiently increased, reaching a peak after 5 h (Fig. 4C). After 24 h, the vast majority of cells displayed a cytoplasmic/vacuolar YFP–KNIESKL fluorescence signal. Thus, engulfed cells show transient proliferation of peroxisomes.

Fig. 4.

GFP–CgCTA1 is induced upon phagocytosis and is located in both cytoplasm and peroxisomes. A. C. glabrata cells before and after being phagocytosed. Exponentially growing ARCg cta1Δ cells transformed with pCgC–GFP–CgCTA1 were washed in PBS containing 0.1% glucose and added to macrophages in a 4:1 ratio at 37°C. Still pictures at the indicated times are shown as overlay of bright-field and fluorescence signals. B. Exponentially growing wild-type cells transformed with pCgADH1–YFP–KNIESKL1 were washed in PBS containing 0.1% glucose and added to macrophages in a 4:1 ratio at 37°C. Cells were fixed and stained with Phalloidin Texas-Red after 0, 2.5, 5, 10 and 24 h for fluorescence microscopy. C. Percentage of phagocytosed C. glabrata cells with visible peroxisomes per macrophage from the total cell number of C. glabrata cells per macrophage after 0, 2.5, 5, 10 and 24 h (left panel). Number of visible peroxisomes within phagocytosed C. glabrata cells after 0, 2.5, 5, 10 and 24 h (right panel).

GFP–CgYap1 and CgMig1–CFP localization changes in phagocytosed cells

The localization of CgCta1 suggested that engulfed C. glabrata cells might experience oxidative stress and/or carbon source starvation. To confirm this independently, we created additional fluorescent reporter constructs. In S. cerevisiae, the glucose-regulated transcriptional repressor Mig1 is rapidly exported from the nucleus in cells starved for glucose (De Vit et al., 1997). S. cerevisiae Yap1 accumulates rapidly in the nucleus of cells exposed to mild oxidative stress (Kuge et al., 1997). To preserve the localization signals of the orthologous transcription factors, CgYap1 was N-terminally fused to GFP whereas CgMig1 was C-terminally fused to CFP. To be detectable, both fusion genes were expressed from centromeric plasmids and driven by the CgADH1 promoter. Nuclear localization was confirmed by simultaneous staining of nucleic acids with DAPI (Fig. 5A and B).

Fig. 5.

Localization of GFP–CgYap1 and CgMig1–CFP during early stage of phagocytosis. A. C. glabrata wild-type cells transformed with pCgADH1–GFP–CgYAP1 were grown in synthetic medium. Cells were stressed by addition of 0.4 mM H2O2 for 10 min. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. An overlay of GFP and DAPI staining is shown in the right panel. GFP–CgYap1 visualized by fluorescence microscopy under phagocytosis conditions (lower panel). Cells were washed in PBS 0.1% glucose and added to macrophages in a 4:1 ratio and incubated at 37°C for 10 min to follow the route of tagged transcription factors. Samples were fixed and stained with Phalloidin Texas-Red. Percentage of cells with nuclear GFP–Yap1 was calculated after 30 min, 1 h and 5 h. White arrows point to nuclear GFP–CgYap1 in yeast inside the phagosome. B. C. glabrata wild-type cells transformed with pCgADH1–CgMIG1–CFP were grown in synthetic medium until glucose depletion. Cells were incubated in fresh medium containing 2% glucose for 10 min or 1× DMEM. Lower panel depicts localization of CgMig1–CFP under phagocytosis conditions. Cells were treated as described in (A).

GFP–CgYap1 was located in the cytoplasm in unstressed C. glabrataΔHTU cells. Upon exposure to mild oxidative stress (0.4 mM H2O2), GFP–CgYap1 rapidly accumulated in the nucleus (Fig. 5A, upper panel). The fusion gene could complement the transcription defects of the corresponding deletion mutant (our unpublished observation). Within the first hour upon engulfment, cells with nuclear GFP–CgYap1 were visible (Fig. 5A, middle panel). We determined the percentage of yeast cells with nuclear GFP–Yap1 per macrophage after 30 min, 1 h and 5 h (Fig. 5A, lower panel) and found a peak at about 1 h. The CgMig1–CFP fluorescence signal accumulated in the nucleus after addition of glucose (2%) to the medium of glucose-starved cells, and was also nuclear in the glucose-rich environment of the macrophage culture medium (DMEM) (Fig. 5B, upper panel). Immediately after phagocytosis, CgMig1–CFP accumulated in the cytoplasm and remained there constantly, indicating glucose starvation (Fig. 5B, lower panel). These data showed that within the phagosome oxidative stress is transient, whereas macrophages are highly effective in depriving the carbon source.

Peroxisomes are transiently induced during phagocytosis

Peroxisome numbers declined at later stages of engulfment (Fig. 4B). In S. cerevisiae, key factors for pexophagy are Atg11 (Yorimitsu and Klionsky, 2005) and Atg17, which is also essential for non-selective autophagy (Cheong et al., 2005). We deleted the C. glabrata CgATG11 and CgATG17 homologues (CAGL0H08558g, CAGL0J04686g) in wild-type (ΔHTU) and pex3Δ cells (Fig. S1). We investigated engulfed C. glabrata cta1Δ, pex3Δ, atg11Δ, atg17Δ, pex3Δatg17Δ, pex3Δatg11Δ and atg11Δatg17Δ mutant cells expressing GFP–CgCta1 after 5 and 24 h (Fig. 6A and E). After 5 h, GFP–Cta1 was located in peroxisomes in the cta1Δ, atg11Δ and atg17Δ mutant cells. In contrast it accumulated in the cytoplasm of pex3Δ, pex3Δatg11Δ and pex3Δatg17Δ mutant cells. However, after 5 h, wild type, atg11Δ and atg17Δ had similar numbers of cells with peroxisomes, whereas after 24 h, peroxisomes were more abundant in atg11Δ and atg17Δ mutants (Fig. 6B). In atg11Δ mutants, peroxisome numbers remained constant between 5 and 24 h engulfment. C. glabrata atg17Δ cells displayed a slight reduction of peroxisomes after 24 h of engulfment, similar to S. cerevisiae atg17Δ cells during prolonged starvation conditions (Cheong et al., 2005), Upon internalization, the cytoplasmic localization of CgMig1–CFP demonstrated the same glucose starvation status in the atg11Δ, pex3Δatg11Δ mutants and wild type (Fig. S2B).

Fig. 6.

Induction and pexophagy of peroxisomes upon phagocytosis. A. Log-phase C. glabrata ARCg cta1Δ, ARCg pex3Δ, ARCg atg11Δ, ARCg pex3Δatg11Δ, ARCg atg17Δ and ARCg pex3Δatg17Δ mutant cells transformed with pGFP–CgCTA1 were used to infect mouse macrophages in a 4:1 ratio at 37°C. Cells were fixed for microscopy after 5 and 24 h. B. Percentage of cells with visible peroxisomes after phagocytosis in macrophages after 5 and 24 h. C. Log-phase C. glabrata ARCg cta1Δ, ARCg pex3Δ, ARCg atg11Δ, ARCg pex3Δatg11Δ, ARCg atg17Δ and ARCg pex3Δatg17Δ and ARCg atg11Δatg17Δ mutant cells were used to infect mouse macrophages in a 1:2 ratio at 37°C. The viability of the engulfed cells was assessed by hypotonic lysis of the macrophages and quantification of colony formation (cfu) on rich medium. Assays were performed in triplicate. A one-way anova was performed and P-values were calculated comparing the numbers of recovered colonies of the indicated strains (**P< 0.005). D. C. glabrata wild type, ARCg atg11Δ, ARCg pex3Δatg11Δ, ARCg atg17Δ, ARCg pex3Δatg17Δ and ARCg atg11Δatg17Δ mutant cells were grown to exponential phase in rich medium; after washing with PBS supplemented with 0.1% glucose, 2 × 105 cells were incubated in selective medium without nitrogen sources and glucose and pH 3.5 at 37°C. After 24 h colony formation (cfu) of mutant cells was determined. Percentage of viable cells was calculated relative to 2 h treatment. E. Log-phase ARCg atg11Δatg17Δ mutant cells transformed with pGFP–CgCTA1 were used to infect mouse macrophages in a 4:1 ratio at 37°C. Cells were fixed for microscopy after 5 h. Overlay of GFP/Texas-Red and BF is shown.

We investigated if the turnover of peroxisomes and mobilization of internal resources are relevant for survival during engulfment. Indeed, the atg11Δ and atg17Δ mutants had a significantly reduced viability after 24 h compared with wild type, cta1Δ and pex3Δ strains. Furthermore, in pex3Δatg11Δ and pex3Δatg17Δ double mutants, the absence of pexophagy might be compensated by absence of peroxisome biogenesis. Consistently, we found that the loss of Pex3 partially reversed the effect of atg11Δ with respect to survival during engulfment (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the double mutant pex3Δatg17Δ did not show this phenotype, indicating a broader function for CgAtg17-dependent non-selective autophagy during engulfment. Strikingly, the atg11Δatg17Δ double mutant, lacking both selective and non-selective autophagy, was highly sensitive to phagocytosis.

To simulate the phagosome environment in vitro we combined nutrient starvation and acidic pH. We incubated C. glabrata wild type, atg11Δ, pex3Δatg11Δ, atg17Δ, pex3Δatg17Δ and atg11Δatg17Δ mutant cells in medium lacking nitrogen and carbon sources at pH 3.5 at 37°C for 24 h. The survival was determined by counting colony-forming units (cfu) after 24 h relative to 2 h treatment (Fig. 6D). In comparison with the wild type, all mutants showed diminished survival. Intriguingly, the pex3Δatg11Δ strain survived better than the atg11Δ strain. Furthermore, the double mutant atg11Δatg17Δ displayed the lowest survival rate, similar to the macrophage model. In the macrophage, after 24 h, most of the engulfed atg11Δatg17Δ cells had lost GFP–CgCta1 fluorescence presumably due to cell death (not shown). However, after 5 h the GFP–CgCta1 fluorescence signal indicated numerous peroxisomes (Fig. 6E). These results indicated that autophagy is beneficial for survival of C. glabrata during engulfment in macrophages, possibly counteracting acute nutrient starvation.

Discussion

Phagocytic cells internalize microbial cells and attack them with a range of microbicidal strategies (Chauhan et al., 2006; Nicola et al., 2008). Microbial pathogens have developed a number of strategies to improve their survival in the host environment (Urban et al., 2006). Here we used three reporters (CgCta1, CgYap1 and CgMig1) to visualize aspects of the response of the human fungal pathogen C. glabrata to macrophage engulfment. We found that C. glabrata cells engulfed by primary mouse macrophages suffer from transient oxidative stress, show signs of carbon source starvation, and transiently induce peroxisomes. Our results revealed that the recycling of internal resources, especially peroxisomes, plays an important protective role for C. glabrata during engulfment in the phagosome.

The presence and/or proliferation of peroxisomes in fungal cells points to adjustment of carbon metabolism. We demonstrated accumulation of peroxisomes in C. glabrata during growth on non-fermentable carbon sources and during engulfment in macrophages. Peroxisomes were visualized using two fluorescent reporter constructs GFP–CgCta1 and YFP–KNIESKL and further confirmed by other criteria. They were induced on medium containing ethanol and oleic acid as carbon source. Furthermore, peroxisomes were dependent on the CgPEX3 gene, a peroxisomal integral membrane protein, whose orthologue in S. cerevisiae is essential for peroxisomal biogenesis (Hohfeld et al., 1991). Peroxisomal catalases such as S. cerevisiae Cta1 (Simon et al., 1991) are scavengers of hydrogen peroxide generated during peroxisomal β-oxidation. We find that C. glabrata catalase expression is regulated by oxidative stress and carbon source, and its intracellular localization correlates with the presence of peroxisomes. This combines the regulation of both yeast catalases. The CgCTA1 gene lacks synteny with the yeast CTA1 gene and other fungal catalases (Gordon et al., 2009). It is tempting to speculate that the shuffling of the C. glabrata genome fostered the accumulation of regulatory elements for oxidative stress and carbon source response.

In a phagocytosis model using bone marrow-derived mouse macrophages, GFP–CgCta1 expressed under the control of the CgCTA1 promoter was induced in the earliest stages after internalization. This could be due to oxidative stress or acute carbon starvation. Intracellular localization of two other fluorescent reporters (CgYap1 and CgMig1) supported rather low oxidative stress load and starvation for glucose of engulfed C. glabrata cells. High-level expression was necessary for detection of GFP–transcription factor fusions and could potentially interfere with signalling. However, both factors are tightly regulated by post-translational modifications and thus buffered for expression level. We found that in a population of engulfed cells a minor fraction displayed signs of acute oxidative stress. This is consistent with other reports. Only a small portion of C. albicans cells derived from mouse kidneys displayed an acute oxidative stress response when examined for CaCTA1 expression (Enjalbert et al., 2007).

The C. glabrata transcriptional response might have been selected to the specific conditions of phagocytosis. Microarray data indicated induction of a group of about 30 genes by both oxidative stress and glucose starvation (Roetzer et al., 2008). Moreover, phagocytosed C. glabrata cells induce genes involved in gluconeogenesis, β-oxidation, glyoxylate cycle, and transporters for amino acids and acetate (Kaur et al., 2007). Induction of peroxisomes after internalization by macrophages indicated adjustment of metabolism within the phagosome. Cells utilizing non-fermentable carbon sources, e.g. fatty acids or ethanol, require peroxisomal β-oxidation and the partly peroxisomal glyoxylate cycle. The induction of non-fermentative carbon metabolism genes is beneficial for the survival of C. albicans (Lorenz et al., 2004; Barelle et al., 2006). In a mouse infection model, Fox2, the second enzyme of the β-oxidation pathway, and isocitrate lyase (Icl1) an enzyme of the glyoxylate cycle, were required for C. albicans virulence (Lorenz and Fink, 2001; Piekarska et al., 2006). However, C. albicans mutants defective in the import receptor of PTS1-targeted peroxisomal proteins, CaPex5, displayed no attenuation of virulence (Piekarska et al., 2006). The survival of C. glabrata devoid of peroxisomes in a pex3Δ mutant was not compromised in our infection model. Also, C. neoformans pex1Δ deletion mutants were not attenuated for virulence (Idnurm et al., 2007). These data support the view that peroxisomes are not a major virulence determinant. Instead, the peroxisomal metabolic pathways, which can function to sufficient extent in the cytosol, appear to contribute to virulence.

In engulfed C. glabrata cells peroxisome numbers declined at later time points. Also at later time points GFP–CgCta1 accumulated partly in the cytosol. Peroxisomes are not known to export proteins, thus the cytosolic fluorescence was most probably due to de novo synthesis or peroxisome turnover. Peroxisomes are degraded by pexophagy, a selective autophagic pathway (Hutchins et al., 1999; Farre and Subramani, 2004). In S. cerevisiae, mutants lacking Atg11 and Atg17 had a severe delay of pexophagy (Kim et al., 2001; Cheong et al., 2005; 2008). In C. glabrata, we found that mutants lacking atg11Δ or atg17Δ had reduced survival in macrophages and in vitro during starvation. Moreover, the C. glabrata double mutant atg11Δatg17Δ displayed a striking additive decrease of survival. In S. cerevisiae, the atg11Δatg17Δ double mutant strain did not contain any detectable autophagic bodies and had a severe autophagy defect (Cheong et al., 2008). We suggest that C. glabrata atg11Δatg17Δ is unable to induce autophagic processes in order to sustain prolonged phagocytosis. Notably, homologues of proteins of the autophagy core machinery have been found from yeast to mammals, but both Atg11 and Atg17 are not conserved and might be a target for antifungal drugs (reviewed by Xie and Klionsky, 2007).

Autophagy is required for C. neoformans virulence (Hu et al., 2008). Furthermore, C. neoformans genes involved in autophagy, peroxisome function and lipid metabolism became also induced during infection (Fan et al., 2005). C. neoformans could escape from macrophages through extrusions of the phagosome, without killing the phagocytic cell (Alvarez and Casadevall, 2006). It has been suggested that this is a pathway for dissemination within the host. Therefore, survival in the macrophage indirectly contributes to virulence. A C. albicans mutant lacking CaATG9 was defective for autophagy, but nevertheless was able to kill macrophages (Palmer et al., 2007). In contrast to C. albicans, C. glabrata is trapped inside the phagosome. In C. glabrata pex3Δatg11Δ cells, we found the sensitivity of atg11Δ partially reversed. We suggest from this genetic observation that autophagy of peroxisomes is beneficial for engulfed C. glabrata cells. C. glabrata pex3Δatg17Δ mutants did not display this effect. Selective pexophagy, which is affected in both atg11Δ and atg17Δ mutants, might help to mobilize intracellular resources during prolonged engulfment. S. cerevisiae uses autophagy to recycle proteins to overcome nitrogen starvation (Onodera and Ohsumi, 2005). Autophagic processes, such as pexophagy, are contributing to virulence of important fungal plant pathogens (Veneault-Fourrey et al., 2006; Asakura et al., 2009). However, an A. fumigatus mutant strain lacking Atg1 also remained virulent (Richie et al., 2007). Thus the role of autophagy for fungal pathogens is also dependent on their morphology (Palmer et al., 2008).

Beside the carbon and nitrogen starvation conditions inside the phagosome, other restrictions, such as pH, hydrolytic enzymes and antimicrobial peptides, might act in a synergistic manner. We infer from the phenotype of our autophagy mutants that macrophage engulfment is essentially a starvation situation in combination with acidic pH. Acidification of the phagosome aids the destruction of some microbes, but it might also contribute to the escape of others. For example, lysosomal acidification induced germ tube formation of C. albicans and therefore contributed to its escape from the macrophage (Kaposzta et al., 1999). The observed oxidative stress response of C. glabrata might result from a switch of metabolism rather than a macrophage-derived oxidative burst. It has been reported that in S. cerevisiae, a shift to oleic acid as carbon source induced a specific Yap1-dependent subset of oxidative stress response genes (Koerkamp et al., 2002). However, we believe that the importance of autophagy for survival suggests a starvation situation. Furthermore, in our model system, the transient induction and degradation of peroxisomes is not supporting substantial metabolism in the phagosome.

Our results demonstrate that monitoring of the intracellular localization of proteins tagged with fluorescent reporters is a highly informative tool to reveal intracellular signalling and metabolic conditions. Here we show that the macrophage is efficiently depriving engulfed C. glabrata cells from nutrient sources. Autophagic processes, prolonging the survival of engulfed cells, are potentially aiding the dissemination of C. glabrata and the establishment of infection.

Experimental procedures

Yeast strains and plasmids

Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Rich medium (YPD), synthetic medium (SC) and yeast nitrogen base medium (YNB) without amino acids and ammonium sulfate were prepared as described elsewhere (Current Protocols in Molecular Biology; Wiley). All strains were grown at 30°C or 37°C as indicated. Oleate medium contained 0.2% oleic acid, 0.3% yeast extract, 0.5% peptone and 0.5% KH2PO4 (pH 6). Oleate plates were incubated at 37°C for 7 days. Glucose concentration between 0.5% and 0.03% (w/v) was determined using the Freestyle mini (Abbott). To assess viability of cells during starvation (Fig. 6D), cfu were determined by spreading on rich medium, usually after 2 h of incubation at 37°C and after the indicated time (24 h). Oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table S1. C. glabrata strains ARCg cta1Δ, ARCg pex3Δ, ARCg atg11Δ, ARCg pex3Δatg11Δ, ARCg atg17Δ, ARCg pex3Δatg17Δ and ARCg atg11Δatg17Δ were obtained by replacing the ORFs with the S. cerevisiae URA3 gene or HIS3 gene generated by genomic integration. Knockout cassettes were synthesized using fusion PCR according to Noble (Noble and Johnson, 2005) from the plasmids pRS316 and pRS313 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989) with the oligonucleotides CTA1-1 to 6, PEX3-1 to 6, ATG11-1 to 6 and ATG17-1 to 6. Correct genomic integration was verified by genomic PCR (primer series Ctrl) followed by Southern analysis using probes generated with primers CTA1-4/CTA1-6, PEX3-1/PEX3-3, ATG11-4/ATG11-6 and ATG17-1/ATG17-3 or ATG17-4/ATG17-6. Probes for Southern and also for Northern analysis (CTA1-5/CTA1-3 and ACT1-5/ACT1-3) were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study.

| C. glabrata strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| ΔHTU | his3Δtrp1Δura3Δ | Kitada et al. (1996) |

| ΔHT6 | his3Δtrp1Δ | Kitada et al. (1996) |

| ARCg cta1Δ | his3Δtrp1Δura3Δcta1Δ::ScURA3 | This study |

| ARCg pex3Δ | his3Δtrp1Δura3Δpex3Δ::ScURA3 | This study |

| ARCg atg11Δ | his3Δtrp1Δura3Δatg11Δ::ScURA3 | This study |

| ARCg pex3Δatg11Δ | his3Δtrp1Δura3Δpex3Δ::ScURA3 atg11Δ::ScHIS3 | This study |

| ARCg atg17Δ | his3Δtrp1Δura3Δatg17Δ::ScURA3 | This study |

| ARCg pex3Δatg17Δ | his3Δtrp1Δura3Δpex3Δ::ScURA3 atg17Δ::ScHIS3 | This study |

| ARCg atg11Δatg17Δ | his3Δtrp1Δura3Δatg11Δ::ScURA3 atg17Δ::ScHIS3 | This study |

Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. To generate pGEM–ACT–CgCTA1, 1800 base pairs of the CgCTA1 promoter were inserted as a SphI/NotI PCR product obtained with primers CTAPro-up and CTAPro-down into the plasmid pGEM–ACT (Gregori et al., 2007). The coding sequence for CgCTA1 was amplified from genomic DNA using primers CTA-up-Not and CTA-down-Nsi, cut and inserted as a NotI/NsiI fragment. GFP was inserted as a NotI/NotI fragment at the N-terminus of CgCTA1. To generate pYFP–KNIESKL YFP was inserted as a NotI/NotI fragment obtained by PCR with primers YFP–Not-Start and YFP–SKL-Stop into the plasmid pGEM–ACT–CgADH1 (Roetzer et al., 2008). CgYAP1 was amplified using primers CgYap5/CgYap3 containing a NotI or a NsiI site; GFP was inserted as NotI/NotI fragment into the plasmid pGEM–ACT–CgADH1 at the N-terminus of CgYAP1. CgMIG1 was amplified using primers Mig1-5sac/Mig1-3nco and inserted into NcoI and SacII cut pGEM–ACT–CgADH1–MSN2–CFP (Roetzer et al., 2008). All cloned PCR fragments used in this study were controlled by sequencing.

Table 2.

Plasmids used in this study.

| Plamid | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pRS316 | CEN6, ARSH4, ScURA3 | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) |

| pRS313 | CEN6, ARSH4, ScHIS3 | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) |

| pACT14 | ARS, CEN and TRP1 marker from C. glabrata | Kitada et al. (1996) |

| pGEM–ACT | ARS, CEN and TRP1 marker from C. glabrata | Gregori et al. (2007) |

| pCgC–GFP–CgCTA1 | CgCTA1–GFP–CgCTA1 (CgCTA1p: SphI/NotI, CgCTA1 ORF NotII/NsiI, GFP NotI/NotI) CgTRP1 | This study |

| pCgC–CgCTA1 | CgCTA1–CgCTA1 (SphI/NotI and NotII/NsiI); CgTRP1 marker | This study |

| pCgCADH1–YFP–KNIESKL | CgCADH1–YFP–KNIESKL (NotI/NotI fragment); CgTRP1 | This study |

| pCgADH1–CgMSN2–CFP | CgADH1–CgMSN2–CFP (CgADH1p: SphI/SacII and CgMSN2: SacII/NsiI); CgTRP1 | Roetzer et al. (2008) |

| pCgADH1–CgMIG1–CFP | CgADH1–CgMIG1–CFP (CgMIG1: SacII/NcoI); CgTRP1 | This study |

| pCgADH1–GFP–CgYAP1 | CgADH1–GFP–CgYAP1 (CgYAP1: NotII/NsiI); CgTRP1 | This study |

Catalase and cytochrome c oxidase assay

Crude extracts were prepared by breakage of yeast cells with glass beads. Catalase activity was assayed spectrophotometrically at 240 nm as described in Durchschlag et al. (2004); protein concentrations were assayed at 280 nm. For the cytochrome c oxidase assay, 0.5 g l−1 Sodium dithionite was added to reduce cytochrome c (0.1 mg ml−1) solution. Cytochrome c has a sharp absorption band at 550 nm in the reduced state. Absorption spectra of cytochrome c were recorded between 410 and 570 nm. Five minutes after addition of crude extracts, spectra were measured to determine the oxidized state of cytochrome c (Lemberg, 1969).

Separation of organelles

Cells were re-suspended in washing buffer (20 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 0.6 M sorbitol), incubated with protease inhibitor PMSF and broken using glass beads. The supernatant was centrifuged for 12 min at 6900 rcf to separate (post-mitochondrial) supernatant and the organellar pellet.

Northern and Southern blot analysis

RNA extraction and separation followed essentially the described protocol (Current Protocols in Molecular Biology; Wiley). Hybridization of [α-32P]-dATP-labelled probes occurred overnight in hybridization buffer (0.5 M Sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.2/7% SDS/1 mM EDTA) at 65°C. For DNA extraction, 10 ml yeast cells (grown to an OD600 = 6) were collected, washed once and re-suspended in Lysis buffer (2% Triton X-100/1% SDS/100 mM NaCl/10 mM Tris pH 8/1 mM EDTA). Genomic DNA was isolated by PCI (phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol) extraction. Digestion of 10 μg of genomic DNA was performed overnight with XcmI for CgPEX3, EcoRV for CgCTA1 and ClaI/NcoI for CgATG11 (5 U μg−1 DNA). The labelled probes were hybridized overnight in hybridization buffer at 65°C. Signals were visualized by autoradiography.

Microscopy

GFP-fluorescence microscopy was performed as described previously (Görner et al., 1998). GFP was visualized in live cells without fixation. All cells were monitored using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope. Images were captured with a Spot Pursuit (Sony) CCD camera using Spotbasic software. Time-lapse microscopy was performed on an Olympus cell-imager system (IX81 inverted microscope) equipped for cell culture observation. Cells were incubated in a glass chamber at 37°C connected to an active gas mixer (Ibidi, Martinsried, Germany). Pictures were taken with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera and analysed using cellM&cellR software (Olympus). Nomarski contrasted, bright-field microscopy pictures are indicated as BF. Quantification and statistical analysis of peroxisomes in C. glabrata cells (Figs 2D, 4C and 6B) have been added in Fig. S3.

Macrophage cell culture

Primary bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were obtained from the femur bone marrow of 6- to 10-week-old C57Bl/6 mice. Cells were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS in the presence of L cell-derived CSF-1 as described (Baccarini et al., 1985). Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. For infection assays, BMDMs were seeded at 5 × 105 cells per dish in 3.5 cm dishes containing medium without antibiotics. Log-phase C. glabrata cells were washed with PBS supplemented with 0.1% glucose and added to macrophages in a 4:1 ratio and incubated at 37°C. For microscopy, cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde for 5 min. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated in 1% Triton X-100 for 1 min. After washing with PBS, cells were dyed with Phalloidin Texas-Red for 30 min. Coverslips were fixed to slides with Mowiol. For cfu assays, BMDMs were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per dish. Exponentially growing C. glabrata cells were washed with PBS supplemented with 0.1% glucose and added to macrophages in a 1:2 ratio and incubated at 37°C. After 45 min, cells were washed three times with PBS to remove not phagocytosed yeast cells and fresh medium was added. At the indicated times, deionized water was added to lyse macrophage cells. C. glabrata cells were spread on YPD plates, colonies were counted after incubation at 37°C for 2 days.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andreas Hartig, Fabian Rudolf, Claudine Kraft, Christa Gregori, Tobias Schwarzmüller and especially Wolfgang Reiter for discussions and advice, Christophe d'Enfert for critical reading, Josef Gotzmann and Doris Mayer for technical support. C.S. wishes to dedicate this article in memory of his father. C.S. was supported by the Herzfelder Foundation, and the Vienna Hochschuljubiläumsstiftung. This work was supported by the Austrian Research Foundation (FWF) through Grants P16726-B14, I27-B03 and SFB F28 to P.K., Grant I031-B from the University of Vienna (to C.S. and P.K.), and P19966-B12 to C.S.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Fig. S1. Southern blot analysis of cta1Δ, pex3Δ, atg11Δ and pex3Δ atg11Δ deletion strains. Both CgCTA1 and CgPEX3 were replaced by ScURA3. CgATG11 was replaced by ScURA3 in the single mutant and by ScHIS3 in the double mutant ARCg pex3Δ atg11Δ. CgATG17 was replaced by ScURA3 in the single mutant and by ScHIS3 in the double mutants ARCg pex3Δ atg17Δ and ARCg atg11Δ atg17Δ. Amplified probes and chromosomal restriction enzyme locations are indicated. Chromosomal DNA derived from ARCg cta1Δ digested with EcoRV and ARCg pex3Δ with XcmI resulted in shortened fragments relative to wild type. Digestion of chromosomal DNA from the ARCg atg11Δ strain with NcoI and from the ARCg pex3Δ atg11Δ double mutant strain with ClaI led to shorter fragments in both cases, since CgATG11 contains neither a NcoI site nor a ClaI site. Picture is a composite of two exposures of the same blot, due to different amounts of DNA (lower panel). Chromosomal DNA derived from ARCg atg17Δ digested with AflIII and ARCg pex3Δ patg17Δ or ARCg atg11Δ atg17Δ with NdeI resulted in shortened fragments.

Fig. S2. Glucose depletion leads to induction of GFP–CgCTA1 and cytoplasmic localization of CgMig1–CFP.

A. GFP–CgCTA1 is induced upon glucose depletion and is located in the cytoplasm. C. glabrata ARCg cta1Δ cells transformed with pCgC–GFP–CgCTA1 were grown in rich medium with glucose to exponential phase and washed twice and incubated in rich medium including 0.5% glucose. Every 10 min concentration of glucose was determined (see Experimental procedures) and samples were fixed for microscopy. GFP fluorescence was visible at about 40 min after glucose exhaustion.

B. Localization of CgMig1–CFP in ARCg atg11Δ and ARCg pex3Δ atg11Δ mutants during internalization by macrophages. CgMig1–CFP was visualized by fluorescence microscopy under phagocytosis conditions. C. glabrata wild-type cells transformed with pCgADH1–CgMIG1–CFP were grown to exponential phase, washed in PBS 0.1% glucose and added to macrophages in a 4:1 ratio and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Samples were fixed and stained with Phalloidin Texas-Red.

C. GFP–CgCTA1 is induced upon phagocytosis. Still pictures from time-lapse analysis are shown as overlay of bright-field and fluorescence signals. Exponentially growing ARCg cta1Δ cells transformed with pCgC–GFP–CgCTA1 were washed in PBS containing 0.1% glucose and added to macrophages in a 4:1 ratio at 37°C.

Fig. S3. Quantification details.

Table S1. Oligonucleotides used.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Alvarez M, Casadevall A. Phagosome extrusion and host-cell survival after Cryptococcus neoformans phagocytosis by macrophages. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2161–2165. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura M, Ninomiya S, Sugimoto M, Oku M, Yamashita S, Okuno T, et al. Atg26-mediated pexophagy is required for host invasion by the plant pathogenic fungus Colletotrichum orbiculare. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1291–1304. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.060996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccarini M, Bistoni F, Lohmann-Matthes ML. In vitro natural cell-mediated cytotoxicity against Candida albicans: macrophage precursors as effector cells. J Immunol. 1985;134:2658–2665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barelle CJ, Priest CL, Maccallum DM, Gow NA, Odds FC, Brown AJ. Niche-specific regulation of central metabolic pathways in a fungal pathogen. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:961–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K, Tilley L, Vennerstrom JL, Roberts D, Rogerson S, Ginsburg H. Oxidative stress in malaria parasite-infected erythrocytes: host–parasite interactions. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:163–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canovas D, Andrianopoulos A. Developmental regulation of the glyoxylate cycle in the human pathogen Penicillium marneffei. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:1725–1738. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M. Glucose repression in yeast. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:202–207. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan N, Latge JP, Calderone R. Signalling and oxidant adaptation in Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:435–444. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves GM, Bates S, Maccallum DM, Odds FC. Candida albicans GRX2, encoding a putative glutaredoxin, is required for virulence in a murine model. Genet Mol Res. 2007;6:1051–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong H, Yorimitsu T, Reggiori F, Legakis JE, Wang CW, Klionsky DJ. Atg17 regulates the magnitude of the autophagic response. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3438–3453. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong H, Nair U, Geng J, Klionsky DJ. The Atg1 kinase complex is involved in the regulation of protein recruitment to initiate sequestering vesicle formation for nonspecific autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:668–681. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G, Fessl F, Traczyk A, Rytka J, Ruis H. Isolation of the catalase A gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by complementation of the cta1 mutation. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;200:74–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00383315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox GM, Harrison TS, McDade HC, Taborda CP, Heinrich G, Casadevall A, Perfect JR. Superoxide dismutase influences the virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans by affecting growth within macrophages. Infect Immun. 2003;71:173–180. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.173-180.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar-Cruz M, Briones-Martin-del-Campo M, Canas-Villamar I, Montalvo-Arredondo J, Riego-Ruiz L, Castano I, De Las Penas A. High resistance to oxidative stress in the fungal pathogen Candida glabrata is mediated by a single catalase, Cta1p, and is controlled by the transcription factors Yap1p, Skn7p, Msn2p, and Msn4p. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:814–825. doi: 10.1128/EC.00011-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JM, Lowry CV, Davies KJ. Transient adaptation to oxidative stress in yeast. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;317:1–6. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vit MJ, Waddle JA, Johnston M. Regulated nuclear translocation of the Mig1 glucose repressor. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1603–1618. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derengowski LS, Tavares AH, Silva S, Procopio LS, Felipe MS, Silva-Pereira I. Upregulation of glyoxylate cycle genes upon Paracoccidioides brasiliensis internalization by murine macrophages and in vitro nutritional stress condition. Med Mycol. 2008;46:125–134. doi: 10.1080/13693780701670509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujon B, Sherman D, Fischer G, Durrens P, Casaregola S, Lafontaine I, et al. Genome evolution in yeasts. Nature. 2004;430:35–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durchschlag E, Reiter W, Ammerer G, Schüller C. Nuclear localization destabilizes the stress-regulated transcription factor Msn2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55425–55432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enjalbert B, MacCallum DM, Odds FC, Brown AJ. Niche-specific activation of the oxidative stress response by the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2143–2151. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01680-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W, Kraus PR, Boily MJ, Heitman J. Cryptococcus neoformans gene expression during murine macrophage infection. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1420–1433. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.8.1420-1433.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farre JC, Subramani S. Peroxisome turnover by micropexophagy: an autophagy-related process. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisow MJ, D'Arcy Hart P, Young MR. Temporal changes of lysosome and phagosome pH during phagolysosome formation in macrophages: studies by fluorescence spectroscopy. J Cell Biol. 1981;89:645–652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.89.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gildea LA, Ciraolo GM, Morris RE, Newman SL. Human dendritic cell activity against Histoplasma capsulatum is mediated via phagolysosomal fusion. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6803–6811. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6803-6811.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles SS, Stajich JE, Nichols C, Gerrald QD, Alspaugh JA, Dietrich F, Perfect JR. The Cryptococcus neoformans catalase gene family and its role in antioxidant defense. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1447–1459. doi: 10.1128/EC.00098-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JL, Byrne KP, Wolfe KH. Additions, losses, and rearrangements on the evolutionary route from a reconstructed ancestor to the modern Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görner W, Durchschlag E, Martinez-Pastor MT, Estruch F, Ammerer G, Hamilton B, et al. Nuclear localization of the C2H2 zinc finger protein Msn2p is regulated by stress and protein kinase A activity. Genes Dev. 1998;12:586–597. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregori C, Schüller C, Roetzer A, Schwarzmüller T, Ammerer G, Kuchler K. The high-osmolarity glycerol response pathway in the human fungal pathogen Candida glabrata strain ATCC 2001 lacks a signaling branch that operates in baker's yeast. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1635–1645. doi: 10.1128/EC.00106-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan J, Stromhaug PE, George MD, Habibzadegah-Tari P, Bevan A, Dunn WA, Klionsky DJ. Cvt18/Gsa12 is required for cytoplasm-to-vacuole transport, pexophagy, and autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia pastoris. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3821–3838. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.12.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig A, Ruis H. Nucleotide sequence of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CTT1 gene and deduced amino-acid sequence of yeast catalase T. Eur J Biochem. 1986;160:487–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb10065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohfeld J, Veenhuis M, Kunau WH. PAS3, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene encoding a peroxisomal integral membrane protein essential for peroxisome biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:1167–1178. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.6.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Hacham M, Waterman SR, Panepinto J, Shin S, Liu X, et al. PI3K signaling of autophagy is required for starvation tolerance and virulenceof Cryptococcus neoformans. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1186–1197. doi: 10.1172/JCI32053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins MU, Veenhuis M, Klionsky DJ. Peroxisome degradation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is dependent on machinery of macroautophagy and the Cvt pathway. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Part 22):4079–4087. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.22.4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idnurm A, Giles SS, Perfect JR, Heitman J. Peroxisome function regulates growth on glucose in the basidiomycete fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:60–72. doi: 10.1128/EC.00214-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CH, Klotz MG, York JL, Kruft V, McEwen JE. Redundancy, phylogeny and differential expression of Histoplasma capsulatum catalases. Microbiology. 2002;148:1129–1142. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-4-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaposzta R, Marodi L, Hollinshead M, Gordon S, da Silva RP. Rapid recruitment of late endosomes and lysosomes in mouse macrophages ingesting Candida albicans. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Part 19):3237–3248. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.19.3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R, Domergue R, Zupancic ML, Cormack BP. A yeast by any other name: Candida glabrata and its interaction with the host. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R, Ma B, Cormack BP. A family of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked aspartyl proteases is required for virulence of Candida glabrata. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7628–7633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611195104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kamada Y, Stromhaug PE, Guan J, Hefner-Gravink A, Baba M, et al. Cvt9/Gsa9 functions in sequestering selective cytosolic cargo destined for the vacuole. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:381–396. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.2.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada K, Yamaguchi E, Arisawa M. Isolation of a Candida glabrata centromere and its use in construction of plasmid vectors. Gene. 1996;175:105–108. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerkamp MG, Rep M, Bussemaker HJ, Hardy GP, Mul A, Piekarska K, et al. Dissection of transient oxidative stress response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by using DNA microarrays. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2783–2794. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft C, Reggiori F, Peter M. Selective types of autophagy in yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:1404–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragler F, Langeder A, Raupachova J, Binder M, Hartig A. Two independent peroxisomal targeting signals in catalase A of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:665–673. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuge S, Jones N, Nomoto A. Regulation of yAP-1 nuclear localization in response to oxidative stress. EMBO J. 1997;16:1710–1720. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze M, Pracharoenwattana I, Smith SM, Hartig A. A central role for the peroxisomal membrane in glyoxylate cycle function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1441–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leberer E, Harcus D, Dignard D, Johnson L, Ushinsky S, Thomas DY, Schroppel K. Ras links cellular morphogenesis to virulence by regulation of the MAP kinase and cAMP signalling pathways in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:673–687. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemberg MR. Cytochrome oxidase. Physiol Rev. 1969;49:48–121. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1969.49.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitz SM, Nong SH, Seetoo KF, Harrison TS, Speizer RA, Simons ER. Cryptococcus neoformans resides in an acidic phagolysosome of human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1999;67:885–890. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.885-890.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin AS, Hines V, Small GM. Citrate synthase encoded by the CIT2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is peroxisomal. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1399–1405. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.4.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Redding S, Dongari-Bagtzoglou A. Candida glabrata: an emerging oral opportunistic pathogen. J Dent Res. 2007;86:204–215. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz MC, Fink GR. The glyoxylate cycle is required for fungal virulence. Nature. 2001;412:83–86. doi: 10.1038/35083594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz MC, Bender JA, Fink GR. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:1076–1087. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.5.1076-1087.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Croudace JE, Lammas DA, May RC. Expulsion of live pathogenic yeast by macrophages. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2156–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcet-Houben M, Gabaldon T. The tree versus the forest: the fungal tree of life and the topological diversity within the yeast phylome. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler G, Schüller C, Adam G, Ruis H. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae UAS element controlled by protein kinase A activates transcription in response to a variety of stress conditions. EMBO J. 1993;12:1997–2003. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RA, Britigan BE. Role of oxidants in microbial pathophysiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:1–18. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missall TA, Pusateri ME, Lodge JK. Thiol peroxidase is critical for virulence and resistance to nitric oxide and peroxide in the fungal pathogen, Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:1447–1458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.03921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Klionsky DJ. Protein turnover via autophagy: implications for metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:19–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y. Catalase gene disruptant of the human pathogenic yeast Candida albicans is defective in hyphal growth, and a catalase-specific inhibitor can suppress hyphal growth of wild-type cells. Microbiol Immunol. 2008;52:16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2008.00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y, Kanbe T, Mizuguchi I. Disruption of the human pathogenic yeast Candida albicans catalase gene decreases survival in mouse-model infection and elevates susceptibility to higher temperature and to detergents. Microbiol Immunol. 2003;47:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2003.tb03376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasution O, Srinivasa K, Kim M, Kim YJ, Kim W, Jeong W, Choi W. Hydrogen peroxide induces hyphal differentiation in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:2008–2011. doi: 10.1128/EC.00105-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuberger G, Maurer-Stroh S, Eisenhaber B, Hartig A, Eisenhaber F. Prediction of peroxisomal targeting signal 1 containing proteins from amino acid sequence. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:581–592. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola AM, Casadevall A, Goldman DL. Fungal killing by mammalian phagocytic cells. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble SM, Johnson AD. Strains and strategies for large-scale gene deletion studies of the diploid human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:298–309. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.2.298-309.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onodera J, Ohsumi Y. Autophagy is required for maintenance of amino acid levels and protein synthesis under nitrogen starvation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31582–31586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer GE, Kelly MN, Sturtevant JE. Autophagy in the pathogen Candida albicans. Microbiology. 2007;153:51–58. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/001610-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer GE, Askew DS, Williamson PR. The diverse roles of autophagy in medically important fungi. Autophagy. 2008;4:982–988. doi: 10.4161/auto.7075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris S, Wysong D, Debeaupuis JP, Shibuya K, Philippe B, Diamond RD, Latge JP. Catalases of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3551–3562. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3551-3562.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:133–163. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekarska K, Mol E, van den Berg M, Hardy G, van den Burg J, van Roermund C, et al. Peroxisomal fatty acid beta-oxidation is not essential for virulence of Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1847–1856. doi: 10.1128/EC.00093-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platta HW, Erdmann R. Peroxisomal dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:474–484. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presterl E, Daxbock F, Graninger W, Willinger B. Changing pattern of candidaemia 2001–2006 and use of antifungal therapy at the University Hospital of Vienna, Austria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:1072–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigneau O, Porta A, Poudrier JA, Colonna-Romano S, Noel T, Maresca B. Genes involved in beta-oxidation, energy metabolism and glyoxylate cycle are induced by Candida albicans during macrophage infection. Yeast. 2003;20:723–730. doi: 10.1002/yea.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie DL, Fuller KK, Fortwendel J, Miley MD, McCarthy JW, Feldmesser M, et al. Unexpected link between metal ion deficiency and autophagy in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:2437–2447. doi: 10.1128/EC.00224-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roetzer A, Gregori C, Jennings AM, Quintin J, Ferrandon D, Butler G, et al. Candida glabrata environmental stress response involves Saccharomyces cerevisiae Msn2/4 orthologous transcription factors. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:603–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani L. Immunity to fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:1–23. doi: 10.1038/nri1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin-Bejerano I, Fraser I, Grisafi P, Fink GR. Phagocytosis by neutrophils induces an amino acid deprivation response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11007–11012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834481100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rude TH, Toffaletti DL, Cox GM, Perfect JR. Relationship of the glyoxylate pathway to the pathogenesis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5684–5694. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5684-5694.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöbel F, Ibrahim-Granet O, Ave P, Latge JP, Brakhage AA, Brock M. Aspergillus fumigatus does not require fatty acid metabolism via isocitrate lyase for development of invasive aspergillosis. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1237–1244. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01416-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal AW. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M, Adam G, Rapatz W, Spevak W, Ruis H. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae ADR1 gene is a positive regulator of transcription of genes encoding peroxisomal proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:699–704. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieringer R, Shio H, Han YS, Cohen G, Lazarow PB. Peroxisomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: immunofluorescence analysis and import of catalase A into isolated peroxisomes. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:510–522. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.1.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban CF, Lourido S, Zychlinsky A. How do microbes evade neutrophil killing? Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1687–1696. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veneault-Fourrey C, Barooah M, Egan M, Wakley G, Talbot NJ. Autophagic fungal cell death is necessary for infection by the rice blast fungus. Science. 2006;312:580–583. doi: 10.1126/science.1124550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyich JM, Braughton KR, Sturdevant DE, Whitney AR, Said-Salim B, Porcella SF, et al. Insights into mechanisms used by Staphylococcus aureus to avoid destruction by human neutrophils. J Immunol. 2005;175:3907–3919. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Klionsky DJ. Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1102–1109. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M, Rayapuram N, Subramani S. The control of peroxisome number and size during division and proliferation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Atg11 links cargo to the vesicle-forming machinery in the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1593–1605. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.