Abstract

Hydroethanolic and aqueous extracts of leaf and stem bark of Parkia biglobosa (Jacq) Benth. (Mimosaceae) were tested against clinical isolates Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhi, Shigella dysenteriae and Enterococcus faecalis, and corresponding collection strains E. coli CIP 105 182, Salmonella enterica CIP 105 150, Shigella dysenteriae CIP 54-51 and Enterococcus faecalis CIP 103 907. Discs of Gentamicin, a broad spectrum antibiotic were used as positive controls. The results showed that all the extracts possess antimicrobial activities. A comparative study of the antibacterial activity of the leaves and that of the bark showed that for all the tested microorganisms, the hydroalcoholic extract of the bark is more active than the aqueous extract of the leaf. The hydroethanolic extract of the leaves is as effective as the aqueous extract of the stem bark prescribed by the traditional healer, suggesting it is possible to use leaves other than the roots and bark. The phytochemical screening showed that sterols and triterpenes, saponosides, tannins, reducing compounds, coumarins, anthocyanosides, flavonosides are present in both bark and leaf but in different concentrations.

Keywords: Parkia biglobosa, Phytochemical, Microorganism, Antimicrobial

Introduction

IUCN (2004) reported that Burkina Faso is a country dangerously threatened by deforestation and that huge quantity of plant materials are used every year in the country for medicinal purposes. The parts of the tree mostly prescribed in traditional medicine are the roots and the barks, the removal of which is traumatizing for the tree if it does not kill it. Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) Benth., a widespread savana tree over the sahelo-sudanian region (Guinko, 1984; Adjanohoun, et al., 1991; Ouédraogo, 1995) was largely prescribed in traditional medicine for its multiple medicinal virtues. It was also reported that its stem bark was successfully used for the treatment of many infectious diseases: dental caries, pneumonia, bronchitis, violent stomachaches, severe cough, diarrhoea, wounds, otitis, dermatosis, amoebiasis, bilharziosis, leprosis, ankylosis, tracheitis, and conjunctivitis (Kerharo and Adam, 1973; Maydell, 1981; Nacoulma 1996, Arbonnier, 2002). The bark was also successfully used against jaundice, haemorrhoids and hypertension while the seeds were prescribed for the treatment of arterial hypertension and the leaves, against piles, amoebiasis, bronchitis, cough, burn, zoster, and abcess. In combination with the roots the leaves were reported to be active against dental caries, conjunctivitis. Most of these infectious diseases are caused by enterobacteriaceae including Escherichia, Shigella, Salmonella and Enterococcus. These microorganisms are among the more commonly met bacteria in human pathology along with Staphylococci and Streptococci (Brooks et al, 1998; Stucke, 1993). Some microorganisms like E. coli are known as part of normal flora but incidentally may cause diseases: urinary tract infection, diarrhoea and hemorrhagic colitis (Berche et Gaillard, 1988). Others like Salmonella and Shigella are regularly pathogenic for humans (Hans, 1993). Salmonella are virulent enterobacteriae causing typhoid fever in humans (Berche and Gaillard, 1988; Edelman and Levine, 1986; Jones and Falkow, 1996). The genus Shigellae is constituted by highly infectious organisms causing bacillary dysentery (Blaser et al., 1983). Enterococcus faecalis is a normal inhabitant of the gut but may cause infective endocarditis (Berche and Gaillard, 1988).

The aim of our study was to check the antimicrobial effects of the bark and that of the leaf against enterobacteria, in order to determine whether the leaves could be used instead of the bark. For the removal of the bark is harmful for the tree.

Material and Methods

The stem bark and leaves of Parkia biglobosa (voucher No. 01) were harvested on May, 2003 at Yako, central zone of Burkina Faso. A voucher specimen has been deposited at the Herbarium of the University of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso and identified by Prof Jeanne Millogo. The plant materials (bark and leaf) were dried at room temperature (25–28°C) and finely grounded using a dry blender. The aqueous extracts (of bark and leaf), the form prescribed in traditional medicine, were obtained by boiling 20 g of plant material in 100 ml of distilled water for 20 min and then filtered through Whatman N°1 filter paper. The hydroalcoholic extracts were obtained by pouring 100 ml of boiling ethanol - water 70% (i.e water - ethanol 3:7) onto 20 g of dry material, according to Harborne J. B's method (1973). The mixture was allowed to cool and then filtered through Whatman N°1 filter paper, and then freeze-dried. Different concentrations of these extracts were obtained by dilutions. Solvents of increasing polarities (chloroform, ethanol and water) were used for fractionation of the extract. The phytochemical screening was carried out according to the standard method. The total phenolics in the ethanolic extracts were evaluated in equivalent tannic acid by a spectrophotodensitometer at 280 nm.

The four extracts were tested against clinical isolated enterobacteria: Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhi, Shigella dysenteriae and Enterococcus faecalis collected from different patients and isolated from blood, urines, pus, stools. Sex and age were not taken into account. The same extracts were also tested against collection (serotyped) strains: E. coli CIP 105 182, Salmonella enterica CIP 105 150, Enterococcus faecalis CIP 103 907, Shigella dysenteriae CIP 54-51. All the strains were cultured overnight at 37°C in Müller-Hinton broth. Discs of Gentamicin, a broad spectrum antibiotic were used as positive controls. The antimicrobial activities were determined by measuring the growth inhibitory zones through the agar-well diffusion method (Perez et al., 1990). The results were read 24 hrs later and the cumulative results emanating from the tests were noticed.

Results

Both stem bark and leaf contained sterols and triterpens, identified in the chloroform extract, saponosides, tannins, reducing compounds, coumarinic derivatives, anthocyanosides and flavonosides in the ethanol-water extract (Table 1). More sterols and triterpens, more anthracenosides and more saponosides were found in the bark. These results also revealed that leaves contained more tannins and more flavonosides than the bark. Alkaloids were absent.

Table 1.

Phytochemical screening

| Chemical compounds | Stem bark | Leaf |

| Steroids and triterpenoids | +++ | ± |

| Saponosides | +++ | ++ |

| Tannins | ++ | +++ |

| Reducing compounds | +++ | +++ |

| Coumarins | + | ++ |

| Alkaloids | − | − |

| Anthocyanins | +++ | +++ |

| Flavonosides | ± | +++ |

| Emodols | − | − |

| Anthracenosides | + | ± |

− : absent ++: abundant

+ : present +++: very abundant ±: traces

The bark contains 2.59 ± 0.201% equivalent tannic acid against 4.01 ± 0.07% for the leaves.

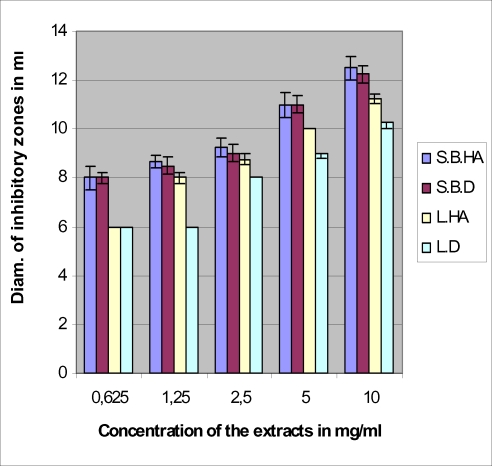

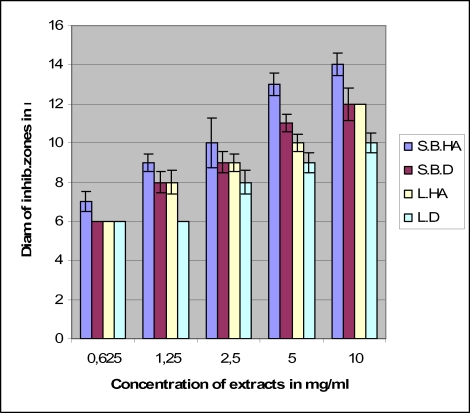

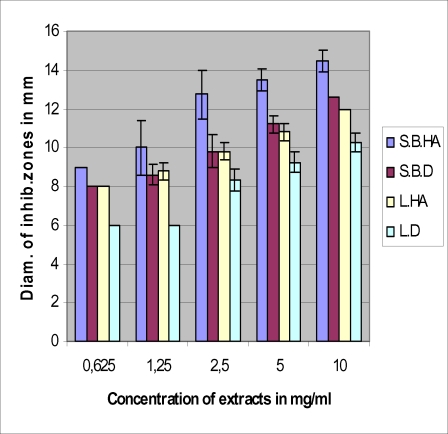

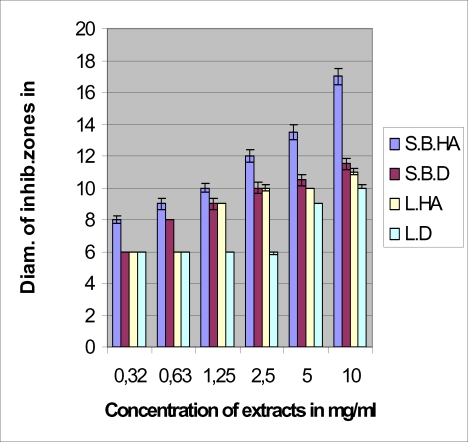

The antimicrobial tests with the four extracts against bacteria gave the results consigned in Figures 1–4. The hydroalcoholic extract of the stem bark was the most active of the four extracts against all the tested microorganisms and the aqueous extract (decoction) of the leaf possessed very moderate inhibitory activity. The hydroalcoholic extract of the leaf was as active as the stem bark aqueous extract prescribed by the traditional healer. However, the hydroalcoholic extract and the aqueous extract of the stem bark have the same effectiveness against E. coli.

Figure 1.

Antimicrobial activities of extracts against Escherichia coli S.B.HA = Stem Bark hydroalcoholic extract S.B.D = Stem bark aqueous extract (decoction) L.HA = Leaf hydroalcoholic extract L.D = Leaf aqueous extract (decoction

Figure 4.

Antimicrobial activities of leaf and stem bark extracts against Enterococcus faecalis

Figure 2.

Antimicrobial activities of leaf and stem bark extracts against Salmonella typhi

Figure 3.

Antimicrobial activities of leaf and stem bark extracts against Shigella dysenteriae

The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) obtained with these extracts against serotyped collected strains are presented in Table 3. The MICs consigned in this table are comparable to those in Tables 1 – 3 and ranged from 0.625 mg.ml−1 to 2.5 mg.ml−1.

Table 3.

Sensitivity of strains to the stem bark hydroalcoholic extracts

| Strains | MIC in mg/ml |

| Escherichia coli CIP 105 182 | 1,25 |

| Salmonella enterica CIP 105 140 | 2,5 |

| Shigella dysenteriae CIP 54 - 51 | 1,25 |

| Enterococcus faecalis CIP 103 907 | 0,625 |

In Table 2, all the strains are very sensitive to gentamicin, showing very large diameters of inhibitory zones. The effect of gentamicin is much more effective than that of the crude extracts.

Table 2.

Sensitivity to gentamicin of the different strains

| Strains | Diameters of inhibitiory zones in mm |

| Salmonella typhi | 29 ± 0.35 |

| Escherichia coli | 33 ± 2.15 |

| Shigella dysenteriae | 26 ± 0.2 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 35 ± 1.25 |

Discussion

The phytochemical screening (Table 1) revealed that the stem bark is rich in steroids and triterpenoids, saponins, tannins, reducing compounds and anthocyanins but that the leaf contained more tannins, coumarins and flavonosides than the bark. These results are consistent with those obtained by Ajaiyeoba (2002) by studying the phytochemical and antibacterial properties of Parkia biglobosa and Parkia bicolor leaf extracts, in Nigeria. Also, these results are in agreement with those obtained by Hall et al. (1997) and those presented in Dossiers Santé (2006). However, alkaloids in Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) Benth. demonstrated by Ajaiyeoba were not determined, while the presence of tannins in appreciable amount in the leaf was largely recognized. Indeed, in the book “Plantes tinctoriales et plantes à tannins du Burkina Faso”, Nacro et Millogo (1993) ranked Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.)Benth. among the richest plants in tannins.

The stem bark extracts were very active against all tested microorganisms (the MIC ranged from 0.312 to 1.25 mg.mL−1). The leaf extracts were also effective but at higher concentrations, the MICs ranging from 2.5 to 5 mg.mL−1. Aqueous extract of the stem bark and hydro-ethanolic extract of the leaf presented similar activities. Through an antimicrobial screening, Ajaiyeoba (2002) conducted with different leaf extracts of Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) Benth., she demonstrated that only at high concentrations (from 50 to 100 mg/ml) would ethyl acetate extract, ethanolic and aqueous extracts be active against Bacillus cereus and Staphylococcus aureus and that none of these extracts had inhibitory effect against Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The insensitivity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to Parkia biglobosa (harvested in Nigeria), aqueous and ethanolic extracts was earlier demonstrated by Millogo et al. (2001).

But, the richness of the leaf in phenolic compounds indicate that it might have antimicrobial effects. Indeed, in Burkina Faso, even if the bark is the most commonly used, the traditional practitioners also use effectively the leaf for the treatment of some infectious diseases. Nacoulma (1996) and Arbonnier (2002) reported that leaves of Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) Benth. were used externally for the treatment of bronchitis, dermatosis, filariosis and per os for the treatment of stomachaches and parasitosis. The results of this investigation gave support to the recent use of the local beer, very rich in ethanol, for the maceration of stem bark and leaf as a prescription by some traditional healers. Patients seem to have more rapid satisfactory effects when used this way. If the maceration of the leaf in local beer is adopted by more traditional healers notably for some prescriptions for adults (considering the religious aspect and the age of the patients) that could reduce tremendously the quantity of raw material used to obtain the same pharmacological effect.

Conclusion

Thehe leaves of P. biglobosa less frequently prescribed in traditional medicine for the treatment of infectious diseases could be as effective as the stem bark prescribed by the traditional healer if extracted with ethanol. Research works should be oriented towards leaves where roots and barks are prescribed by the traditional healers. This could be an important contribution to the fight against deforestation; a way to protect the environment.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assistance of Mr. Yaro Boubacar of the Department of Traditional Medecine and Pharmacopoeia and the following laboaratories: Laboratoire National d'Elevage, Laboratoire de l'Hôpital Yalgado OUEDRAOGO Ouagadougou - BURKINA FASO, Hôpital Pédiatrique de Ouagadougou - Burkina Faso, Laboratoire du Centre and Laboratoire de Saint Camille

References

- 1.Adjanohoun E, Ahiyi MRA, Aké Assi L, Dramane K, Elewude JA, Fadoju S O. Traditional Medecine and Pharmacopoeia - Contribution to ethnobotanical and floristic studies in Western Nigeria. 1991. p. 191. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ajaiyeoba E. Phytochemical and antibacterial properties of Parkia biglobosa and Parkia bicolor leaf extracts. Afr J Biomed Res. 2002;5:125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbonnier M. Arbres, arbustes et lianes des zones sèches d'Afrique de l'Ouest. CIRAD , Muséum national d'histoire naturelle. 2002;2:392. (Fre). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berche P, Gaillard JL. Bactériologie. Les bactéries des infections humaines. Médecine - Sciences Flammarion. 1988:93–99. (Fre). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaser MJ, Pollard RA, Feldman RA. Shigella infections in the United States, 1974–1980. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:771. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.4.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks G F, Butel J S, Morse S A. Medical Microbiology. Vol. 21. Lange Medical books/McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 224–230. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dossiers santé Contribution à l'étude des plantes médicinales utilisées dans le traitement des affections bucco-dentaires (3ème partie) 2006. (Fre). www.google.com du 23 février 2006.

- 8.Edelman R, Levine MM. Summary of an international workshop on typhoid fever. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:329. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guinko S. Végétation de la Haute Volta. Université de Bordeaux III; 1984. pp. 195–198. (Fre). Thèse de Doctorat d'Etat. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall J B, Tomlinson H F, Oni P I, Buchy M, Aebischer DP. Parkia Biglobosa a Monograph. Bangor, UK: School of Agriculture and Forest , Sciences, University of Wales; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hans GS. Formic acid fermentation and Enterobacteriacea, General Microbiology. Cambridge Low Price Editions. 1993;7:311–319. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harborne JB. Phytochemical methods. Fakenham. 1973:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones BD, Falkow S. Salmonellosis : host responses and bacterial virulence. Ann Rev Immunol. 1996;14:533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerharo J, Adam JG. La pharmacopée sénégalaise traditionnelle. Plantes médicinales et toxiques, Vigot frères. 1973:579–580. (Fre). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maydell HJ von. Arbres et arbustes du Sahel : leurs caractérisations et leurs utilisations. 1981:312–315. (Fre). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millogo H, Guissou IP, Idika N, Adepoju-Bello A, Coker HAB, Agomo PU. Identification of phenolic acids and free phenols of the stem barks of Parkia biglobosa (Jacq)Benth (Mimosacées) : comparative study of the activity of the total and hydroalcoholic extracts with that of the gentamicin against pathogenic bacteria. West Afr J Pharm. 2001;15:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nacoulma O. Plantes médicinales et pratiques médicales traditionnelles au B.F. - Cas du Plateau Central. 1996;2:179–180. (Fre). Thèse de Doctorat d'Etat. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nacro M, Millogo-Rasolodimbi J. Plantes tinctoriales et plantes à tannins du Burkina Faso. ScientifikA. 1993:106. (Fre). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouedraogo AS. Parkia biglobosa (Leguminosae) en Afrique de l'Ouest: Biosystématique et amélioration. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Institute for forestry and Nature Research IBN-DLO; 1995. pp. 74–75. (Fre). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez C, Pauli M, Bazerque P. An antibiotic assay by the agar-well method. Acta Biologiae et Medecine experimentalis. 1990;15:113–115. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stucke V A. Microbiology for nurses. Low Price Edition. 1993;7:210. 195. [Google Scholar]

- 22.UICN, author. Programme quadriennal (2005 – 2008) de l'IUCN pour le Burkina Faso. 2004. [Google Scholar]