Abstract

Biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex 1 (BLOC-1) is a protein complex formed by the products of eight distinct genes. Loss-of-function mutations in two of these genes, DTNBP1 and BLOC1S3, cause Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome, a human disorder characterized by defective biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles. In addition, haplotype variants within the same two genes have been postulated to increase the risk of developing schizophrenia. However, the molecular function of BLOC-1 remains unknown. Here, we have generated a fly model of BLOC-1 deficiency. Mutant flies lacking the conserved Blos1 subunit displayed eye pigmentation defects due to abnormal pigment granules, which are lysosome-related organelles, as well as abnormal glutamatergic transmission and behavior. Epistatic analyses revealed that BLOC-1 function in pigment granule biogenesis requires the activities of BLOC-2 and a putative Rab guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor named Claret. The eye pigmentation phenotype was modified by misexpression of proteins involved in intracellular protein trafficking; in particular, the phenotype was partially ameliorated by Rab11 and strongly enhanced by the clathrin-disassembly factor, Auxilin. These observations validate Drosophila melanogaster as a powerful model for the study of BLOC-1 function and its interactions with modifier genes.

INTRODUCTION

Endosomes comprise a series of dynamic intracellular compartments that serve as major sorting stations for a wide variety of proteins; in turn, this active sorting has profound effects on key cellular functions such as signaling and morphogenesis (1). Several components of the endosomal protein sorting machinery were described first through basic cell biological studies and later found associated with genetic defects that cause human disease; conversely, others were first identified through their association with genetic disorders in humans or mice (2,3). To the first group belongs adaptor protein (AP)-3 (4), and to the second biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex (BLOC)-1 and BLOC-2 (5). The three are biochemically stable, multimeric protein complexes that contain as subunits the products of genes mutated in various forms of Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome (HPS), an autosomal recessive disorder in which defective biogenesis of melanosomes and platelet dense granules results in the combined clinical manifestations of oculocutaneous albinism and platelet storage pool deficiency (6,7). AP-3 is a hetero-tetramer containing δ, β3, μ3 and σ3 subunits; mutations in the AP3B1 gene encoding one of two alternative isoforms of the β3 subunit cause HPS-2 disease (8). BLOC-1 appears to exist as an octamer formed by one molecule each of pallidin, muted, dysbindin, cappuccino, snapin and BLOC subunit (BLOS)1, BLOS2 and BLOS3; mutations in the DTNBP1 gene encoding dysbindin and the BLOC1S3 gene encoding BLOS3 underlie HPS-7 and -8 diseases, respectively (9,10). BLOC-2 is considered a hetero-trimer containing the HPS3, HPS5 and HPS6 proteins, which are encoded by the genes mutated in HPS-3, -5 and -6 diseases (11,12). The three protein complexes are ubiquitously expressed, and can be found in the cytoplasm in soluble form as well as associated to endosomal membranes (4–6).

The cellular mechanisms by which mutations causing deficiency in AP-3, BLOC-1 or BLOC-2 lead to hypopigmentation in HPS patients and mouse models of the disease have begun to be unraveled. Melanosomes are specialized compartments of the endosomal–lysosomal system, and despite their unique morphology and function they are considered lysosome-related organelles (LROs), at least in what pertains to the key role of endosomes in the biogenesis of both types of organelles (reviewed in 6, see also 13). In most cell types, AP-3 is involved in membrane budding and cargo recognition events required for vesicle-mediated trafficking of integral membrane proteins (4). In melanocytes, AP-3 is known to mediate the trafficking of the key melanin-synthesizing enzyme, tyrosinase, from early endosomes to maturing melanosomes (14,15). Abnormal trafficking of various melanosomal membrane proteins through endosomes has been observed in melanocytes deficient in BLOC-1 or -2 (16–20). These observations support the idea that AP-3 and BLOC-1 and -2 are all components of a molecular machinery that mediates protein targeting to melanosomes. Although not formally demonstrated, it is likely that analogous functions for these complexes in platelet-producing megakaryocytes may account for the fact that mutations in subunits of these complexes also result in defective platelet dense granules, which like melanosomes are LROs (6,7). However, the molecular functions of BLOC-1 and -2 remain obscure. Accumulating evidence suggests that AP-3 and BLOC-2 may function independently of each other (16–18,21). Whether BLOC-1 functions only with BLOC-2 in an AP-3-independent pathway (18) or also in concert with AP-3 (17,22,23) remains to be determined.

It has long been recognized that AP-3 is physiologically important in the brain (24,25), and accumulating evidence argues for the same to be the case of BLOC-1 (26). In the mammalian brain, expression of alternative isoforms of the β3 and μ3 subunits results in the assembly of at least two types of AP-3 complexes; one of them is thought to regulate protein trafficking to lysosomes and the other to synaptic vesicles (27–29). Consistent with this idea, neurological phenotypes such as locomotor hyperactivity and spontaneous seizures, as well as abnormal synaptic transmission, have been documented for mice deficient in the unique δ subunit (common to all forms of AP-3) or upon targeted disruption of the brain-specific isoforms of β3 and μ3 (reviewed in 27,28). However, no genetic association between AP-3 and any human neurological or psychiatric disorder has been demonstrated to date (30,31). In contrast, allelic variations in the DTNBP1 gene encoding the dysbindin subunit of BLOC-1 have been proposed to increase the genetic risk of developing schizophrenia (32,33), which is a genetically complex, common psychiatric disorder with poorly understood pathophysiology (34). The potential association between DTNBP1 haplotypes and schizophrenia stemmed from family-based analyses on a region of chromosome 6p where genetic linkage to the disease had been noted (32). This initial work was followed by a large number of genetic association studies (33), and predated demonstration that the gene product is a subunit of BLOC-1 in several tissues (9), including brain (35), and that a mouse strain carrying a spontaneous mutation in Dtnbp1 displays, besides the typical manifestations of HPS (9), abnormal glutamatergic transmission (36,37) and various behavioral phenotypes (37–42). In addition, reduced levels of dysbindin protein were observed in postmortem brain samples from schizophrenic patients (43,44). A second gene encoding a BLOC-1 subunit, BLOC1S3, was also associated with schizophrenia in a case–control study (45). While the potential roles of DTNBP1 and BLOC1S3 as genetic risk factors of schizophrenia, like those of virtually every other candidate susceptibility gene for this disease, have yet to be confirmed (46), a provocative pathogenesis model has been put forth whereby endosomes could serve as a common cellular ‘arena’ for epistatic interactions between multiple susceptibility genes to translate into biological effects of relevance to brain development and function (26).

The fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, is widely used as a relatively simple yet powerful model organism for the study of many aspects of human biology and disease, among other things because of its suitability for forward genetic screening. Relevant to the above-mentioned disorder of LROs, HPS, is the fact that mutations in fly orthologues of the human genes defective in HPS-2 and -5 resulted in eye pigmentation defects (47–50). The cellular basis for these eye pigmentation defects appears to mirror that for the hypopigmentation associated with HPS: while fly eye pigments are chemically unrelated to mammalian melanins, the pigment granules where they are synthesized and stored are, like mammalian melanosomes, LROs (51). Hence, the endosome-associated protein sorting machinery may be important for efficient trafficking of integral membrane proteins involved in pigmentation, such as the ABC transporter encoded by the white gene (52), to maturing pigment granules, and at least some components of this machinery are likely to be conserved between flies and mammals.

The fruit fly has also been successfully used to model some aspects of more complex human disorders, including Parkinson's and other neurodegenerative diseases (53), and recent work has raised the possibility of generating fly models of relevance to schizophrenia (54). Here, one major strategy is to obtain a visible phenotype that would allow exploiting the power of fly genetics to identify novel modifier genes of physiological or medical relevance; this strategy has already yielded significant new insights into the mechanisms of various neurodegenerative diseases (reviewed in 53).

In this work, we sought to generate a fly model of BLOC-1 deficiency with which to test for genetic interactions with modifier genes. Our long-term goals are 2-fold: first, the phenotypic and genetic interaction data could potentially help us to understand the molecular function of this protein complex, which as mentioned above remains obscure (5–7). Second, the genetic interactions observed in flies could guide the formulation of hypotheses for the analysis of epistasis in association studies of schizophrenia, which owing to the multiple-test problem can become overwhelming if attempted indiscriminately without any prior biological information (55). We herein report the generation of mutant flies carrying null alleles in the most conserved BLOC-1 subunit, Blos1, and eye pigmentation phenotypes that are consistent with a role of fly BLOC-1 in pigment granule biogenesis. We also report abnormal electrophysiology of glutamatergic terminals and behavioral phenotypes, thus implying neuronal functions for fly BLOC-1. Using the eye pigmentation phenotype as a biological readout, we provide genetic evidence suggesting that the function of BLOC-1 in flies requires the activities of BLOC-2 and a putative Rab guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor named Claret (56), and that the phenotype elicited by BLOC-1 deficiency can be modified by altered expression of various proteins involved in endosomal protein trafficking, such as Rab11 and the clathrin-disassembly factor, Auxilin (57–59).

RESULTS

Homologues of BLOC-1 subunits in Drosophila melanogaster

Previous work had suggested the existence of fly homologues for several subunits of mammalian BLOC-1, including dysbindin but notably excluding BLOS3 (5,49). In contrast, a recent study concluded that the dysbindin-encoding gene originated in chordates after divergence from invertebrates (60). To address the question of whether a full complement of genes encoding BLOC-1 subunits exists in D. melanogaster, we carried out systematic homology searches using the sensitive PSI-BLAST algorithm (61). Starting from the sequences of human BLOC-1 subunits as ‘queries,’ a single homologue encoded by the genome of D. melanogaster was identified for each of BLOS1, BLOS2, cappuccino, dysbindin, pallidin and snapin upon the first PSI-BLAST iteration, which is equivalent to a standard gapped-BLASTP search (61). The resulting E-values of 0.001 or less (Table 1) were considered significant given the large effective search space, which ranged from 6.3 × 1011 to 9.7 × 1012. A second PSI-BLAST iteration was required to identify one homologue for each of the remaining two subunits, BLOS3 and muted, again with significant E-values (Table 1). As judged from pairwise sequence alignment, homology between each pair of human and fly proteins extended through most of the molecules, although some of the proteins had amino- or carboxyl-terminal extensions that were absent from their counterparts (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). Additional PSI-BLAST searches, this time using each fly protein as the query, yielded the corresponding BLOC-1 subunit as the only human homologue with significant E-value—upon a single iteration for six of the subunits and two iterations for BLOS3 and muted. Although the BCAS4 gene is considered a paralogue of human cappuccino (62), the product of CG14149 from D. melanogaster is clearly more similar to the latter, such that using the fly protein as the query only cappuccino was identified with significant E-value (3 × 10−6) upon a standard BLASTP search. In addition, the proteins encoded by the human DBNDD1 and DBNDD2 genes bear a discrete region with homology to dysbindin; however, only the similarity between human dysbindin and the fly CG6856 gene product was high enough to allow their identification as homologues of each other by means of standard BLASTP searches. Based on these analyses, we propose that the products of the fly genes listed in Table 1 represent the orthologues of the eight subunits of mammalian BLOC-1. Except for snapin, these Drosophila genes are still referred to using a preliminary ‘CG’ nomenclature. The names that we propose (Table 1) match those of the human BLOC-1 subunits except for CG14149, which encodes the homologue of human cappuccino. Unfortunately, the name ‘cappuccino’ is already used for a fly gene encoding an actin nucleator factor (63) unrelated to mammalian cappuccino, and the gene symbol ‘cno’ (similar to that of the human CNO gene encoding cappuccino) is already used for the fly gene canoe, which encodes an unrelated PDZ protein (64). To avoid confusion, and consistent with the names blos1, blos2 and blos3 given to three of the genes listed in Table 1, we propose the name blos4 for CG14149.

Table 1.

Homologues of human BLOC-1 subunits encoded by the fruit fly genome

| Human subunit |

Drosophila gene |

E-valuea | Amino acid identityb (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current name | Proposed name | |||

| BLOS1 | CG30077 | blos1 | 6 × 10−31 (1) | 55 |

| BLOS2 | CG14145 | blos2 | 7 × 10−16 (1) | 40 |

| BLOS3 | CG34255 | blos3 | 9 × 10−6 (2) | 22 |

| Cappuccino | CG14149 | blos4 | 2 × 10−4 (1) | 25 |

| Dysbindin | CG6856 | dysbindin | 6 × 10−15 (1) | 38 |

| Muted | CG34131 | muted | 2 × 10−7 (2) | 18 |

| Pallidin | CG14133 | pallidin | 1 × 10−3 (1) | 24 |

| Snapin | snapin | snapin | 3 × 10−13 (1) | 33 |

aHomology searches were carried out using the PSI-BLAST algorithm and the amino acid sequences of human BLOC-1 subunits as ‘queries.’ Numbers between parentheses indicate iteration number; the first iteration of PSI-BLAST is equivalent to a standard BLASTP search.

bCalculated from the alignments shown in Fig. 1A and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1.

Figure 1.

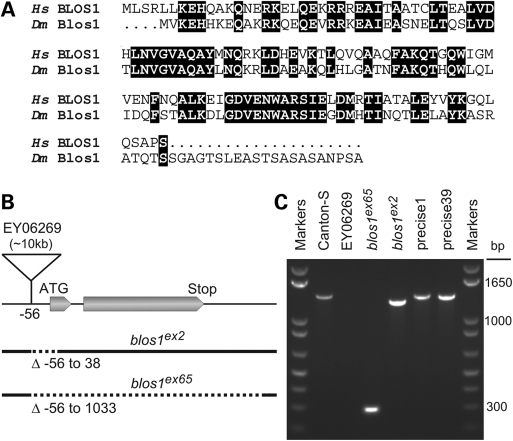

Sequence analysis and mutant alleles of the fly orthologue of human BLOS1. (A) Alignment of the primary sequences of BLOS1 from Homo sapiens (Hs) and the product of the blos1 gene from Drosophila melanogaster (Dm). Identical amino acid residues are highlighted. (B) Schematic representation of the organization of the blos1 gene, indicating the two exonic regions that compose the ORF, the insertion site of a P-element in the fly line EY06269 and the segments deleted (dotted lines) in the blos1ex2 and blos1ex65 mutant alleles. (C) Analysis by agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products obtained by amplification of genomic DNA from the indicated fly lines, using primers derived from sequences about 206 bp upstream and 1156 bp downstream of the P-element insertion site. Molecular size markers were run on both sides of the gel. Notice the reduced sizes of the PCR products obtained from homozygous blos1ex2 and blos1ex65 flies. Due to the large size of the inserted P-element (∼10 kb), no PCR product was obtained under these conditions for the EY06269 line.

The yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) system was previously used to map binary inter-subunit interactions within human BLOC-1 (65). Although this methodology is considered prone to false positives and negatives, there is growing consensus that Y2H interactions observed for pairs of orthologous proteins from different species are likely to be ‘real’ (66,67). Bearing this in mind, we used the Y2H system to test 35 combinations of fly orthologues of BLOC-1 subunits fused to the DNA-binding and activation domains of the yeast Gal4 transcription factor. The choice of testing these 35 construct combinations, which included 13 of the 17 combinations analogous to those that had yielded positive interactions between human BLOC-1 subunits (65), was solely based on the availability of Y2H constructs that did not yield false positives in combination with control constructs (e.g. empty vector). Because most BLOC-1 subunits contain regions with predicted propensity to fold into coiled coils, as negative controls we included Y2H constructs comprising coiled-coil-forming domains from the unrelated protein Dp71, which in turn interacted specifically with those of α-dystrobrevin (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). We detected six interactions analogous to those previously observed between human BLOC-1 subunits, thus linking Drosophila Pallidin with Blos1, Blos4 and Dysbindin as well as Snapin with Blos2 and Dysbindin (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). Another conserved interaction, between Blos1 and Blos2, was not detected in our assay but was recently reported as part of a large-scale Y2H project (67). Although the resulting interaction network bears fewer connections than that reported for human BLOC-1 (65) and fails to include Drosophila Muted or Blos3 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2), together our findings support the existence of a fly counterpart of mammalian BLOC-1.

Eye pigmentation phenotype of BLOC-1-deficient flies

We next sought to generate a fly model of BLOC-1 deficiency by following a reverse-genetics approach. We focused on the Blos1 subunit, not just because of its evolutionary conservation (55% identical amino acid residues between the human and fly proteins; Fig. 1A) but also because of the availability of a fly line carrying a P-element transposon inserted 56 bases upstream of the translation initiation codon (Fig. 1B). Upon excision of the P-element through the action of Δ2-3 transposase (68), we screened for fly lines in which the excision event had resulted in a genomic deletion at the blos1 locus without deleting any of the two flanking genes. Out of 210 homozygous lines screened by PCR, two mutant alleles were identified: one of them (blos1ex2) had lost a 94 bp segment including the only possible translation initiation codon, and the other (blos1ex65) was devoid of the entire open-reading frame (ORF) encoding Blos1 (Fig. 1B and C).

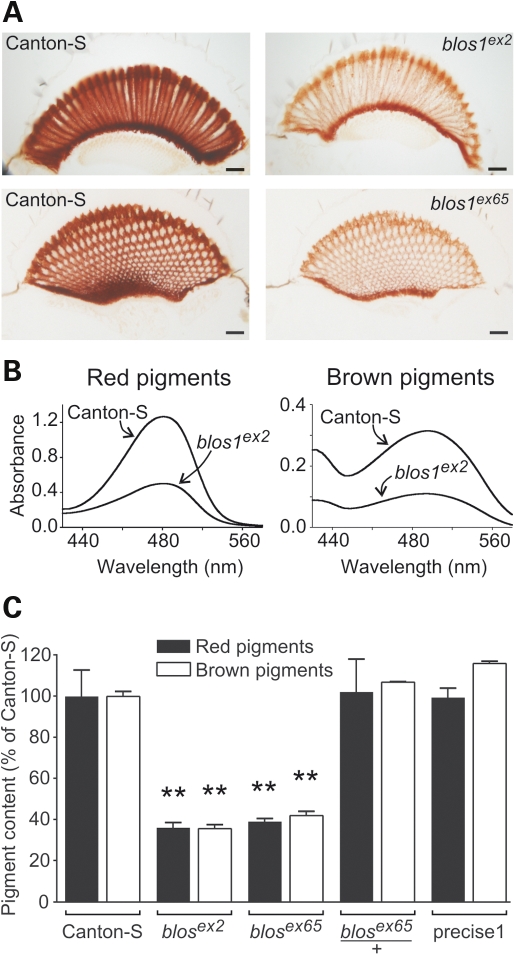

To examine the biological consequences of disrupting blos1 in flies, both mutant alleles were made isogenic with Canton-S by successive outcrosses. Homozygous mutant flies were viable and fertile. The most obvious phenotype of these ‘cantonized’ Blos1-mutant lines was abnormal eye color, which was somewhat dull when compared with the bright red color of Canton-S flies. That such abnormal eye color was a consequence of a generalized reduction in pigment content became apparent upon microscopic observation of unstained eye sections (Fig. 2A) and chemical extraction and quantification of red and brown pigments (Fig. 2B and C). The phenotypes of flies homozygous for either blos1ex2 or blos1ex65 were virtually identical: pigmentation was decreased homogeneously throughout the retina in the absence of any gross anatomical abnormality (Fig. 2A), and both red and brown pigment contents were reduced to 35–40% of the levels of Canton-S flies of matched gender and age (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, heterozygous flies (e.g. blos1ex65/+), and homozygous flies resulting from ‘precise’ excision of the P-element without disruption of blos1, displayed normal eye pigmentation (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Eye pigmentation defects of blos1 mutant flies. (A) Representative light microscopic images of unstained eye sections obtained from adult wild-type (Canton-S) and homozygous blos1ex2 and blos1ex65 mutants. Images pairs were selected to show longitudinal and cross-sections of the ommatidia, and were acquired under identical illumination and digital camera settings. Scale bars: 20 μm. (B) Absorption spectra of red and brown pigments extracted from the heads of 2–3-day-old males of the Canton-S and blos1ex2 fly lines. (C) Quantification of the contents of brown pigments (open bars) and red pigments (filled bars) in the eyes of males of the indicated genotypes. Values are expressed as percentages of the pigment content of Canton-S flies and represent means ± SD. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's tests comparing each sample versus the corresponding Canton-S control: **P < 0.01.

To test whether these eye pigmentation defects could be rescued by transgenic expression of wild-type Blos1, we used a binary expression system whereby the transcription factor encoded by the yeast GAL4 gene was expressed in the developing eye under the control of the glass multimer reporter (GMR), and expression of Blos1 was controlled by GAL4-responsive upstream activating sequences (UAS). A practical issue that needed to be addressed, however, was that the best GMR-GAL4 drivers available to us carried as genetic marker a ‘mini-white’ construct (w+mC) causing misexpression of White, which at high expression levels could potentially modify on its own the pigmentation phenotype of Blos1-mutant flies. To address this issue, we used the Δ2-3 transposase to modify a pre-existing GMR-GAL4 driver inserted into the third chromosome (69), and obtained a GMR-GAL4 variant that was devoid of mini-white activity while retaining its ability to drive robust expression of a reporter gene controlled by UAS (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3). We also generated the UAS-blos1 construct using a modified vector, pCarUSVyr, which lacks mini-white and instead uses a body color gene, yellow, as the genetic marker. Using three separate UAS-blos1 transgenic lines, we observed robust GAL4-dependent rescue of the eye pigmentation phenotype of Blos1-mutant flies (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4), indicating that the eye color phenotype was a direct consequence of disruption of the blos1 gene.

Next, we tested whether similar eye pigmentation phenotypes could be observed upon interference with the function of other fly orthologues of mammalian BLOC-1 subunits. To this end, we took advantage of the availability (70) of fly lines carrying transgenic constructs for GAL4-dependent expression of ‘hairpin’ RNA interference (RNAi) targeting various BLOC-1 subunit orthologues. Three of them, predicted to silence the products of dysbindin, pallidin and blos4, elicited eye pigmentation defects depending upon the presence of the GMR-GAL4 driver (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5). The resulting phenotypes, however, were milder than those of blos1ex2 and blos1ex65 flies, likely due to residual activity of the complex upon incomplete RNAi-mediated silencing. Consequently, the experiments described thereafter were carried out using the Blos1-mutant flies generated by imprecise excision.

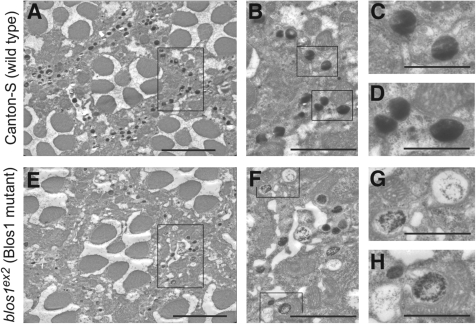

Given that the enzymatic pathways for biosynthesis of red and brown pigments are independent of each other, a simultaneous reduction in both types of pigments is characteristic of mutations in white, which encodes an ABC transporter required for transport of precursors for both types of pigments into pigment granules (71), and in genes of the so-called ‘pigment granule group,’ which are involved in pigment granule biogenesis (51). To explore the possibility of blos1 representing a previously unrecognized member of the pigment granule group, the morphology of granules was examined by electron microscopy on serial sections of Epon-embedded fly eyes. The phenotypes of blos1ex2 and blos1ex65 mutant retinas were, once again, indistinguishable from each other. Figure 3 shows representative images, corresponding to ommatidia cross-sections approximately 35 μm away from the lenses, for wild-type and one of the two mutants. While no defects in the organization of the ommatidia, including the number of photoreceptors, were noted, both blos1ex2 and blos1ex65 mutant retinas displayed reduced number of electron-dense granules within pigment cells. Abnormal morphology of the remaining pigment granules could be appreciated at high magnification (Fig. 3G and H). Although we cannot rule out that these morphological abnormalities might have been generated or exacerbated during processing of the retinas for electron microscopy, the phenotype was consistently observed on sections of blos1ex2 and blos1ex65 mutant retinas in which the morphology of other cellular structures (e.g. mitochondria, rough endoplasmic reticulum) was well preserved, and very rarely observed on sections of wild-type retinas.

Figure 3.

Representative transmission electron micrographs of eye sections from adult wild-type and blos1 mutant flies. (A–H) Cross-sections of ommatidia, each of them containing seven photoreceptors and separated from the others by a sheath of pigment cells. In wild-type flies (A–D), the cells of the sheath contain numerous electron-dense pigment granules. In homozygous blos1ex2 flies (E–H), the ommatidia appear normal in size and number of photoreceptors, but the number and electron density of pigment granules in the sheath cells are significantly reduced. Rectangles in (A) and (E) denote areas shown at higher magnification in (B) and (F), respectively. Likewise, the regions highlighted in (B) and (F) are shown at higher magnification in (C and D) and (G and H), respectively. Scale bars: 5 μm (A and E), 2.5 μm (B and F) and 1 μm (C, D, G and H).

Taken together, these observations suggest that Blos1 is required for normal pigment granule biogenesis.

Abnormal electrophysiology and behavior of Blos1-mutant flies

Recent studies have revealed abnormalities in glutamatergic transmission (36,37) and behavior (37–42) in sandy mice, which carry a mutation in the gene encoding the dysbindin subunit of BLOC-1 (9). To test whether disruption of blos1 in flies might lead to related phenotypes, two sets of experiments were performed.

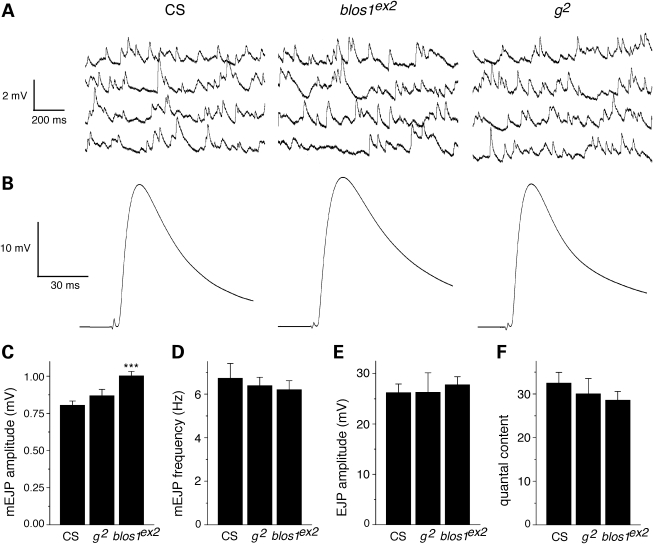

In the first set, spontaneous miniature excitatory junction potentials (mEJPs) and evoked junction potentials (EJPs) were measured in glutamatergic neuromuscular junctions from third-instar larvae homozygous for blos1ex2, and compared with those of age-matched larvae of the Canton-S control line or homozygous for a mutant allele in a pigment granule group gene—the garnet (g) gene encoding the δ subunit of the AP-3 complex. Representative mEJP and EJP traces are shown in Figure 4A and B, respectively. As shown in Figure 4C, the average amplitude of mEJPs measured in the neuromuscular junctions from Blos1-mutant larvae was ∼24% larger than that of the corresponding wild-type samples, whereas that of AP-3-deficient preparations was not significantly different from the control. Although differences in muscle resting potential were noted (−68 ± 2, −75 ± 1 and −76 ± 2 mV for Canton-S, blos1ex2 and g2, respectively), these differences were too small to account for those observed in mEJP amplitude. Thus, upon correction of mEJP amplitudes by non-linear summation, the difference between Canton-S (0.81 ± 0.02 mV) and blos1ex2 (1.01 ± 0.03 mV) remained essentially unaltered and statistically significant (P < 0.001). No significant differences were observed in terms of average muscle input resistance (5.6 ± 0.2, 5.8 ± 0.2 and 5.4 ± 0.3 MOhm for Canton-S, blos1ex2 and g2, respectively), the frequency or mEJP events (Fig. 4D), the average amplitude of EJPs (Fig. 4E) or the estimated quantal content (EJP/mEJP amplitude ratio; Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

Electrophysiological analyses of glutamatergic neuromuscular junctions from larvae of the wild-type line Canton-S (CS) or homozygous for mutations in the genes encoding BLOC-1 subunit 1 (blos1ex2) or the δ subunit of AP-3 (g2). (A) Representative traces of spontaneous miniature excitatory junction potentials (mEJPs). (B) Representative evoked junction potentials (EJPs). (C and D) Recordings like those shown in (A) were used to measure the amplitude (C) and frequency (D) of 70 consecutive mEJP events per experiment. (E) EJP amplitude was measured for the last 75 events of a series of 100 stimulations at 2 Hz. (F) The quantal content was estimated as the average amplitude of EJPs divided by the mean amplitude of mEJPs. Bars represent means ± SEM of at least seven independent experiments. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test: ***P < 0.001 versus CS.

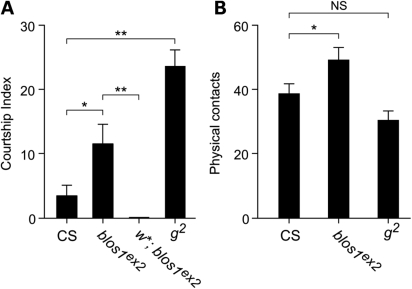

In the second set of experiments, the behavior of young adult male flies homozygous for the blos1ex2 allele was examined. Male-to-male courtship was examined because a significant increase in such behavior had been previously documented for flies carrying mutant alleles of genes of the pigment granule group, including the g2 allele causing AP-3 deficiency (52,72). As shown in Figure 5A, the number of Blos1-mutant flies engaged in male-to-male courtship behavior during a 10 min period was significantly higher than that of wild-type files, albeit lower than that of g2 flies. Because the courtship behavior of AP-3-deficient flies had been shown to require activity of the white gene product (52), it was of interest to examine the behavior of w*; blos1ex2 double mutants (where w* represents a null allele of white). No male-to-male courtship behavior was observed for double mutant flies in any of 10 independent experiments, indicating that the ABC transporter encoded by white is essential for expression of the courtship phenotype elicited by Blos1 deficiency. Besides the courtship behavior phenotype, visual inspection of homozygous blos1ex2 flies suggested a general locomotor hyperactivity, including rapid jumping and running as well as interrupted flight. To further assay for altered activity, we counted the number of physical contacts that occurred between flies during a 10 min period. As shown in Figure 5B, blos1ex2 flies engaged in more contacts with each other than Canton-S flies did among themselves. This phenotype was deemed unlikely to be secondary to vision deficits, which might have resulted from the decreased pigmentation of blos1ex2 fly eyes, because it was not observed for g2 flies with comparable eye pigmentation defects (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Abnormal behavior of blos1 mutant flies. (A and B) Adult male flies (5 ± 2 days after eclosion) of the Canton-S (CS) control line, or carrying mutant alleles that render them deficient in BLOC-1 subunit 1 (blos1ex2), the AP-3 complex subunit δ (g2) or the ABC transporter White (w*), were placed in groups of 25 in plastic Petri dishes, under conditions of high humidity and controlled temperature, and visually monitored for a 10 min period. (A) The male-to-male courtship index was calculated as the number of males displaying courting behaviors in ‘courtship chains,’ not counting the first male in each chain. (B) Physical contacts were assessed by counting the number of times that a male fly touched another during the 10 min period, regardless of the type of behavior displayed. See Materials and Methods for further experimental details. Bars represent means ± SEM of 10 independent experiments. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni comparison of selected group pairs: NS, not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

These results of our electrophysiological and behavioral analyses suggest that the activity of Drosophila Blos1 is important for both normal synaptic function and complex behavior.

Genetic interactions between blos1 and classic pigment granule group genes

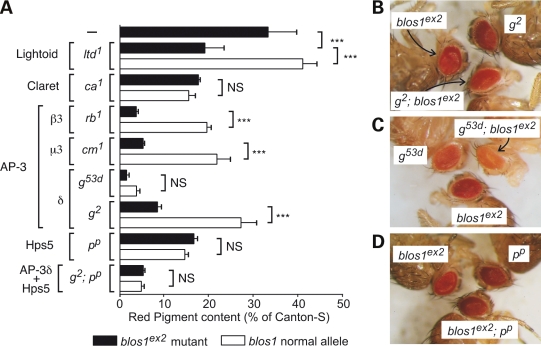

The eye pigmentation phenotype of Blos1-mutant flies appeared to us as potentially amenable to systematically testing for epistatic genetic interactions. To explore this possibility, we generated homozygous double mutants carrying blos1ex2 and mutant alleles of pigment granule group genes of interest, namely those encoding AP-3 subunits (g, rb and cm encoding δ, β3 and μ3, respectively), the fly orthologue of a mammalian BLOC-2 subunit (p encoding Hps5), the closest fly homologue of mammalian Rab32 and Rab38 (ltd encoding Lightoid) and a putative Rab guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor (ca encoding Claret). While several mutant alleles of genes encoding AP-3 subunits are considered mild-to-moderate hypomorphs, at least one of them (g53d) as well as pp, ltd1 and ca1 represent very strong hypomorphs or null mutations (49,56,73). Since blos1ex2 is a null allele, an exacerbation of the eye pigmentation phenotype in double mutants would imply that the product of the other gene can function, at least in part, independently of Blos1. Likewise, if the mutant allele of the other gene produces no functional protein, a phenotypic enhancement would imply that Blos1—and by extension BLOC-1—can function, at least in part, independently of the other gene product.

As shown in Figure 6A–C, the eye pigmentation defects of double mutant flies deficient in Blos1 and AP-3 subunits were more severe than the corresponding single mutants. This appeared to be the case also for the strong g53d allele (Fig. 6C), even when the 2-fold difference in red pigment content of g53d; blos1ex2 versus g53d flies failed to reach statistical significance upon Bonferroni's correction for multiple testing (Fig. 6A). A more severe phenotype relative to the corresponding single mutants was also observed for the homozygous blos1ex2, ltd1 double mutant line (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the eye pigmentation phenotypes of homozygous double mutants carrying blos1ex2 and either ca1 or pp were indistinguishable from the corresponding ca1 and pp single mutants (Fig. 6A and D). A related phenomenon was noted when g2; blos1ex2; pp triple mutants were compared with g2; pp double mutants: although blos1ex2 was able to exacerbate the pigmentation phenotype elicited by the g2 allele alone, it failed to modify that of g2; pp double mutants (Fig. 6A). These observations suggest that Blos1 is able to function, at least in part, independently of AP-3 and Lightoid, and that its role in pigment granule biogenesis requires the activities of Claret and Hps5.

Figure 6.

Genetic interactions between blos1es2 and mutant alleles of pigment granule group genes. Flies carrying mutant alleles of the genes encoding the Rab-family member Lightoid (ltd1), its putative guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor Claret (ca1), subunits of the AP-3 complex (rb1, cm1, g2 and g53d) or the Hps5 subunit of BLOC-2 (pp) were crossed with flies carrying the blos1es2 allele to obtain homozygous double mutants and a homozygous g2; blos1ex2; pp triple mutant. (A) Quantification of red pigments extracted from the heads of 2–3-day-old male flies homozygous for the mutant alleles indicated on the left and for normal (open bars) or mutant (filled bars) alleles of blos1. Values are expressed as percentages of the pigment content of Canton-S flies and represent means ± SD. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni comparison of selected group pairs: NS, not significant; ***P < 0.001. (B–D) Eye color phenotypes of selected double mutants in comparison with the corresponding single mutants.

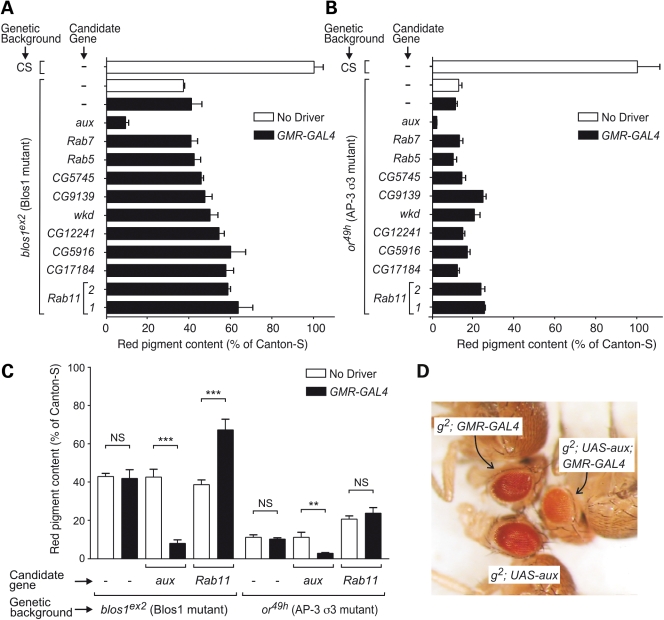

Misexpression of Auxilin enhances the eye pigmentation phenotype of Blos1-mutant flies

Encouraged by the results described in the previous section, we embarked upon the search for novel modifiers of Blos1 function. A GAL4-dependent misexpression strategy was appealing given our success in using a modified GMR-GAL4 driver to rescue the pigmentation phenotype of Blos1-mutant flies (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4) and the availability of a wide variety of fly lines carrying P-element transposons engineered for misexpression of either cloned ORFs or the products of endogenous genes located in the vicinity of the insertion sites (74). One practical limitation, however, was the need to perform two successive fly crosses per candidate, owing to the behavior of blos1ex2 as a recessive allele. Hence, we chose to restrict our initial screening to fly lines predicted to misexpress candidate gene products implicated in protein trafficking within the endosomal–lysosomal system—the proposed site of action of mammalian BLOC-1 (17,18,20,23,29). Figure 7A shows quantitative results obtained in a secondary analysis of a subset of these candidates, which included several Rab GTPases (Rab5, Rab7 and Rab11), a putative Rab guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor homologous to mammalian Rabex-5 (CG9139), four putative Rab GTPase-activator proteins (wkd, CG5745, CG5916 and CG12241), a putative effector of Rho and Arf GTPases (CG17184), and a clathrin-disassembly factor (aux). The same candidates were also tested in parallel for their ability to modify the eye pigmentation phenotype of the or49h allele of the AP-3 σ3-encoding gene, which like blos1 resides on the fly second chromosome (Fig. 7B). A striking phenotypic enhancement effect on both blos1ex2 and or49h was observed upon misexpression of Drosophila Auxilin (aux gene product). In contrast, misexpression of the other candidate genes elicited partial amelioration of eye pigmentation defects or no effect at all (Fig. 7A and B). Additional control experiments verified that the phenotypic enhancement effect of aux was strictly dependent upon the presence of the GMR-GAL4 driver; GAL4-dependence was also verified for the partial suppression effect of Rab11 on the phenotype of blos1ex2 flies but not for that of the same candidate on the phenotype of or49h flies (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Screening for genetic modifiers of the eye pigmentation phenotypes of fly mutants deficient in BLOC-1 subunit 1 (blos1ex2) or in AP-3 subunit σ3 (or49h). (A and B) Quantification of red pigments extracted from the heads of male flies homozygous for the mutant alleles blos1ex2 (A) and or49h (B) and carrying P-element insertions for GAL4-dependent misexpression of the products of the indicated candidate genes. Two independent P-element insertions nearby Rab11, labeled as ‘1’ and ‘2’, were used. Controls included Canton-S (CS) flies and homozygous mutant flies devoid of P-elements for GAL4-dependent misexpression (–) and either lacking (open bars) or carrying (filled bars) the GMR-GAL4 driver. Values are expressed as percentages of the pigment content of Canton-S flies and represent means ± SD. (C) Additional analyses were performed as in (A) and (B) to test whether the effects observed for the constructs targeting auxilin and Rab11 (P-element insertion 1) were dependent on the presence of the GMR-GAL4 driver. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni comparison of selected group pairs: NS, not significant; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (D) Eye color phenotypes of g2 mutant male flies carrying the UAS-aux transgene for misexpression of Auxilin, the GRM-GAL4 driver, or both. See Supplementary Materials, Table S1 for the corresponding quantitative analysis.

The phenotypic enhancement effect of Auxilin was unexpected, and hence it was further investigated. Using a transgenic UAS-aux construct for expression of the full-length protein without any epitope tags, strong GAL4-dependent effects were observed not only for blos1ex2 and or49h but also for mutant alleles of genes encoding other AP-3 subunits (Fig. 7D and Supplementary Material, Table S1). In comparison, the GAL4-dependent effect of the UAS-aux transgene on eye pigmentation was less pronounced in the context of the ltd1 mutation and significantly milder in the genetic background of Canton-S flies (Supplementary Material, Table S1). We considered the possibility of the effects of Auxilin misexpression resulting from interference with the activity of the endogenous Auxilin protein, for instance, by competition with binding partners (clathrin, Hsc70) that may need to interact in a concerted fashion. While null mutations in aux had been previously shown to result in early lethality, various hypomorphic alleles had been characterized and shown to elicit abnormal eye morphology, e.g. rough eye, in part due to the role of Auxilin in endocytic events that are critical for Delta/Notch signaling (57–59). In contrast, we observed neither rough eye phenotype nor any other obvious alteration in eye morphology upon GMR-GAL4-driven misexpression of Auxilin in Canton-S or mutant flies. Conversely, when three hypomorphic alleles, auxG257E, auxL78H and auxI670K (57,58), were transferred by standard crosses into the genetic backgrounds of Canton-S and g2 (the latter being a background in which the enhancement effect of misexpressed Auxilin was most severe; Fig. 7D and Supplementary Material, Table S1), for each of them we observed rough eye phenotype but no significant effect on eye pigmentation (data not shown). Hence, the phenotypic enhancement effect caused by Auxilin misexpression was deemed unlikely to arise from a dominant-negative mechanism.

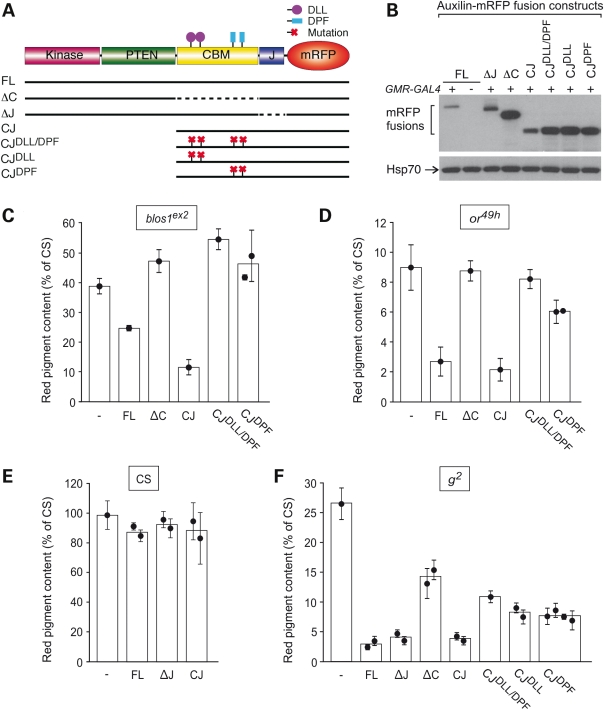

Compared with the effects of misexpressing untagged Auxilin (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Materials, Table S1), those elicited by full-length Auxilin fused at its carboxyl terminus to monomeric red fluorescence protein (mRFP) were less dramatic in the context of the blos1ex2 mutation and minimal in Canton-S flies; however, they were essentially unaltered in the context of the AP-3 subunit mutations or49h and g2 (see for example Fig. 8C–F, construct ‘FL’). These observations raised the possibility of differential structural requirements in Auxilin—at least at its carboxyl terminus—for eliciting phenotypic enhancement effects on Blos1- and AP-3-mutant alleles. To examine this possibility in detail, structure-function analyses were undertaken. As previously described (57–59), Drosophila Auxilin comprises kinase and PTEN domains separated from the carboxyl terminal ‘J’ domain by a long flexible region; the flexible region is often referred to as ‘clathrin-binding’ owing to the presence of pairs of conserved DLL and DPF motifs for binding to clathrin and the clathrin-associated AP-2 complex, respectively (see scheme in Fig. 8A). Transgenic fly lines carrying a series of Auxilin-mRFP constructs with deleted domains and point mutations (Fig. 8A) were generated. We chose to perform these analyses in the context of Auxilin-mRFP fusions because of the availability of antibodies against mRFP, which allowed us to verify GMR-GAL4-driven expression of each mutant variant by immunoblotting analysis of fly head extracts (for example, see Fig. 8B). The transgenic lines were subjected to standard crosses to obtain male flies carrying each of the transgenes encoding Auxilin-mRFP fusion constructs and the GMR-GAL4 driver in the genetic backgrounds of blos1ex2 (Fig. 8C), or49h (Fig. 8D), Canton-S (Fig. 8E) and g2 (Fig. 8F). Owing to the location of both blos1 and or genes to the second chromosome, transgenes that were inserted into that chromosome were only tested in the genetic contexts of Canton-S and g2. In all cases, controls without any Auxilin-mRFP fusion construct (labeled as ‘–’ in Fig. 8C–F) or lacking GMR-GAL4 were analyzed in parallel. The controls lacking GMR-GAL4 were used to correct for effects of the mini-white marker carried by the Auxilin-mRFP transgenes; such effects were minimal in all cases except for the ‘ΔJ’ construct, which ranged from 11 to 25% of the pigmentation levels of controls lacking Auxilin-mRFP transgene. Neither the kinase domain nor the PTEN domain was required for the phenotypic enhancement caused by Auxilin misexpression; in fact, a truncated construct comprising only the clathrin-binding region and the J domain (CJ) effectively enhanced the phenotypes of blos1ex2, or49h and g2 (Fig. 8C, D and F). On the other hand, deletion of the clathrin-binding region (in the ΔC construct) abrogated the ability of Auxilin-mRFP to enhance the phenotypes caused by the blos1ex2 and or49h mutations (Fig. 8C and D) and reduced but not eliminated the effect on g2 (Fig. 8F). In the cases of blos1ex2 and or49h, simultaneous mutation of the two DLL and the two DPF motifs yielded an Auxilin-mRFP-fusion protein that, like the ΔC variant, was unable to enhance the eye pigmentation defects elicited by either allele. However, a differential effect was observed for a construct variant in which only the DPF motifs were mutated: while this construct was unable to enhance the phenotype of blos1ex2 flies, it did elicit a small but statistically significant effect on or49h flies (Fig. 8C and D, and Supplementary Material, Table S2). A complex picture emerged from the structure-function analyses carried out in the context of the hypomorphic g2 allele. There, all of the mutations in the DLL and DPF motif pairs, alone or combined, resulted in Auxilin-mRFP-fusion variants that were less active than the full-length or CJ versions but nonetheless more active than the ΔC variant, as if both types of motifs contributed to the enhancement effect but were not the only active elements in the clathrin-binding region. In addition, while deletion of the clathrin-binding region resulted in a construct with partial activity, removal of the conserved J domain had no effect on the ability of Auxilin-mRFP to enhance the phenotype of g2 (Fig. 8F and Supplementary Materials, Table S2). Importantly, none of these Auxilin-mRFP constructs elicited, upon misexpression driven by GMR-GAL4, any significant decrease in the eye pigmentation of Canton-S flies (Fig. 8E and data not shown) thus arguing for the specificity of the genetic modifier effects observed in the contexts of Blos1- and AP-3-mutant alleles.

Figure 8.

Structural requirements for the phenotypic enhancement effects caused by misexpression of Auxilin in the eyes of flies deficient in subunits of BLOC-1 or AP-3. (A) Schematic representation of the domain organization of Auxilin from Drosophila melanogaster fused to monomeric red fluorescence protein (mRFP), and of transgenic constructs used in this study. FL, full length; CBM or C, clathrin-binding-motif-containing region. Dashed segments denote deleted regions. The approximate locations of pairs of DLL and DPF motifs, which in some constructs were mutated to DAA and APA respectively, are indicated. (B) The heads of transgenic flies carrying the Auxilin-mRFP fusion constructs depicted in (A), with (+) or without (−) the GMR-GAL4 driver, were homogenized and processed for immunoblotting using antibodies to the mRFP domain or to the endogenous Hsp70 protein (the latter as a loading control). (C–F) Quantitative analyses of the effects of Auxilin-mRFP contruct misexpression on the red pigment content of 2–3-day-old male flies of the wild-type (CS) genetic background (E) as well as homozygous for the BLOC-1 subunit mutant allele blos1ex2 (C) or the AP-3 subunit mutant alleles or49h (D) and g2 (F). Each data point represents the mean ± SD of red pigment values obtained per Auxilin-mRFP contruct transgene in the presence of the GMR-GAL4 driver, normalized to those obtained for the same transgene in the absence of the driver. Data points labeled as ‘−’ represent red pigment values obtained for flies carrying the GMR-GAL4 driver without any Auxilin-mRFP construct. In cases where two or more independent insertions of the same Auxilin-mRFP construct were available for analysis, bars represent the overall weighted averages. One-way ANOVA analysis: P < 0.0001 for the data sets shown in (C), (D) and (F); not significant differences between the data groups shown in (E). See Supplementary Materials, Table S2 for the results of post hoc statistical tests.

DISCUSSION

As stated in the Introduction section, recessive mutations in two of the eight genes encoding BLOC-1 subunits are known to cause HPS-7 and -8 disease in humans. However, only one HPS-7 patient (9) and six HPS-8 patients from a single family (10) have been described in the literature. Consequently, most of what we know so far about the function of BLOC-1 has resulted from the study of mutant mouse lines and derived cell cultures (6,7). In this work, we describe the first non-mammalian model of BLOC-1 deficiency. Flies homozygous for null mutations in blos1, the best conserved of the genes encoding BLOC-1 subunits, displayed phenotypes that relate to those documented for BLOC-1-deficient mice, namely: reduced pigmentation caused by impaired biogenesis of LROs, altered glutamatergic transmission and abnormal behavior. Furthermore, we describe the use of Blos1-mutant flies to uncover genetic modifiers of BLOC-1 function.

Among the several mouse models of HPS, those expressing little or no BLOC-1 activity display the most severe coat pigmentation defects (5,21). These phenotypes, consistent with ultrastructural analyses showing accumulation of pre-melanosomes with little or no melanin (75,76), have led to the notion that BLOC-1 plays a key role in protein trafficking to melanosomes (and presumably other LROs), with this role being relatively more important than those of other HPS-associated complexes such as AP-3 and BLOC-2 (5,21,76). On the other hand, an alternative view has stemmed from the findings that a significant pool of tyrosinase, a major determinant of pigmentation in mammals, reaches melanosomes despite the lack of BLOC-1 function (18), and that poor melanogenesis in BLOC-1-deficient cells can be explained instead by specific missorting of a copper transporter required for tyrosinase activation (20). Because pigment synthesis in the fly eye is independent of tyrosinase activity (and, to our knowledge, of copper transport), our results offer quite another perspective on how critical BLOC-1 function may be for LRO biogenesis. We found that Blos1-mutant fly eyes display a significant decrease in content of both red and brown pigments, which together with the observed defects in number and morphology of pigment granules imply that the function of BLOC-1 in flies is, like in mammals, required for normal LRO biogenesis. However, the eye color phenotype of these null mutant flies was clearly less severe than those of flies deficient in AP-3 (carrying strong alleles such as g53d and or49h) or BLOC-2 (null pp allele), thus arguing against the notion that BLOC-1 would be more important than these two complexes for LRO biogenesis—at least in the fly eye. Similarly to what had been reported for mice (17,21), the color phenotype of double mutant flies simultaneously deficient in BLOC-1 and AP-3 was more severe than those of the corresponding single mutants, further supporting the idea that these two complexes can function, at least in part, independently of each other. It should be noted, however, that these results do not exclude the possibility of BLOC-1 and AP-3 acting together under some physiological conditions, nor they imply that their independent functions must occur in distinct organelles or trafficking routes. With regards to the functional relationship between BLOC-1 and -2, contrasting views have arisen from interpretation of the phenotypes of double mutant mice. One view, based on the semi-dominant exacerbation of the phenotype of homozygous Bloc1s3rp mice by a null allele of the gene encoding a subunit of BLOC-2, is that BLOC-1 and -2 can function independently of each other (77). A caveat of this interpretation, however, is that Bloc1s3rp mice express residual BLOC-1 activity due to the existence of a small pool of assembled complex (65). On the other hand, the phenotypes of double mutant mice carrying the Pldnpa mutation (thought to express no BLOC-1 activity) and null mutations in either of two BLOC-2 subunit genes were virtually identical to that of homozygous Pldnpa mice (17,21). These observations led to the alternative interpretation that BLOC-1 and -2 function together in the same pathway, although the severe pigmentation phenotype of Pldnpa mice and the relatively milder phenotype of BLOC-2-deficient mice represent a potential confounding factor. Again, our analyses using flies offer a different perspective, among other things because none of the eye color phenotypes of single mutant flies deficient in BLOC-1 or -2 is severe enough to raise a similar concern. While our results are consistent with the idea that BLOC-1 and -2 function in a common pathway, surprisingly the observed epistatic effect is the reverse of that observed in mice. Here, the pigmentation phenotype of double mutants flies carrying null alleles of blos1 (affecting BLOC-1) and p (BLOC-2) was indistinguishable from that of BLOC-2 single mutants, and so was that of triple mutants affecting BLOC-1, BLOC-2 and AP-3 from that of double mutants affecting BLOC-2 and AP-3. These results underscore the need of investigating more than one model system before drawing general conclusions about the functions of these protein complexes.

In addition to the eye pigmentation phenotype, we report that Blos1-mutant flies display abnormal glutamatergic transmission and complex behavior. Specifically, the average amplitude of mEJPs was increased in neuromuscular junctions of Blos1-mutant larvae, and adult mutant flies behaved abnormally in two assays that examined interactions between flies, including male-to-male courtship. Abnormal glutamatergic synaptic transmission has been documented for hippocampal (36) and prefrontal cortical neurons (37) from sandy mice, which carry an in-frame mutation in the dysbindin-encoding gene, as well as for isolated cortical neurons from mice obtained by targeted disruption of the snapin-encoding gene (78). In addition, a number of complex behavioral phenotypes have been described for sandy mice (37–42). Granted, drawing analogies between these phenotypes in flies and mice is not straightforward. Nevertheless, our results indicate that, like its mammalian counterpart, fly BLOC-1 is required, directly or indirectly, for normal synaptic function in glutamatergic terminals and is physiologically important for complex behavior. It is plausible that effects of BLOC-1 deficiency on glutamatergic transmission in the central nervous system, similar to those observed in the neuromuscular junction, could relate mechanistically to the behavioral phenotypes. Along these lines, it is noteworthy that misexpression of the fly counterpart of vesicular glutamate transporter 1, which in mammals was tentatively linked to dysbindin/BLOC-1 function (43), was reported to increase the amplitude of mEJPs in larval neuromuscular junctions (79) as well as male-to-male courtship in adult flies (80), two phenotypes that we herein report for BLOC-1-deficient flies. However, alternative mechanisms must be considered. For example, given that misexpression of White is sufficient to exacerbate male-to-male courtship behavior (72,81) and that of Blos1-mutants was suppressed by lack of White function, one possible scenario is that male-to-male courtship, like reduced eye pigmentation, was a consequence of mislocalization of the White protein in BLOC-1-deficient flies. Future research exploiting the genetic tools available for D. melanogaster should help to elucidate the mechanism(s) of neuronal BLOC-1 function.

In addition to having used Blos1-mutant flies to examine genetic interactions between BLOC-1 and AP-3 or BLOC-2, which as discussed above had been first studied in mammals, we have taken advantage of this genetic tool to uncover novel functional interactions, such as those with Claret, Rab11 and Auxilin.

Claret is encoded by a classic eye color gene of the pigment granule group, and predicted to act as a guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor to activate GTPases of the Rab family (56). A likely substrate of Claret is Lightoid, a Rab that is encoded by another pigment granule group gene and capable of binding to Claret in vitro (56). However, the eye color phenotype of flies devoid of Lightoid function (null ltd1 allele) is milder than that of flies lacking Claret (null ca1 allele) (Fig. 6A, open bars) (56), thus arguing for the existence of one or more additional Rabs that can act downstream of Claret—at the very least as a compensatory mechanism in Lightoid-mutant flies. Our results from epistatic analyses suggest that BLOC-1 functions in a Claret-dependent pathway, and that BLOC-1 and Lightoid can act—at least in part—independently of each other. While the identity of an alternative Rab for this pathway, with which BLOC-1 could interact functionally, remains to be ascertained, our screening for genetic modifiers of BLOC-1 function revealed that Rab11, but not Rab5 or Rab7, can partially suppress the phenotype of Blos1-mutant flies upon misexpression. So far, our attempts to demonstrate a direct functional relationship between Rab11 and Lightoid have been unsuccessful; for example, misexpression of a dominant-negative form of Rab11 under the control of GMR-GAL4 resulted in flies with very small eyes, likely as a consequence of the role of Rab11 in tissue development (82), and attempts to manipulate the expression levels of endogenous Rab11 in Lightoid-mutant flies resulted in early lethality (data not shown, see also 83). Nevertheless, even if fly Rab11 turns out not to overlap functionally with Lightoid, the finding that it can act as a modifier of BLOC-1 function is significant and deserves future investigation, particularly in light of recent work describing human Rab11 as a potential binding partner of the dysbindin subunit of BLOC-1 (83,84) and demonstrating a direct role for Rab11-positive endosomes in protein trafficking to mammalian melanosomes (85).

We have observed a strong phenotypic enhancement effect upon misexpression of Auxilin in the eye of Blos1-mutant flies. This effect was not unique to BLOC-1; Auxilin misexpression also enhanced the eye pigmentation defect of flies deficient in AP-3 and, to a lesser extent, of those devoid of Lightoid function. Auxilin is the only fly counterpart of two human proteins named auxilin and cyclin G associated kinase (also known as auxilin 2). Mammalian auxilin was initially isolated as a factor that can promote in vitro the assembly of clathrin, a conserved scaffolding protein that is critical for multiple protein trafficking routes originating at the plasma membrane, trans-Golgi network and endosomes. It was later demonstrated, however, that the main (albeit probably not the only) biological role of the auxilins is to promote clathrin disassembly and recycling (reviewed in 86). Because this recycling process is critical to ensure the availability of enough molecules for additional rounds of clathrin-coated vesicle formation, strong depletion or complete removal of auxilin function in vivo has profound effects on clathrin-dependent trafficking and causes early lethality in various animals (86), including flies (57). We have considered the possibility of Auxilin misexpression eliciting an incomplete dominant-negative effect on the endogenous protein; however, the effects of Auxilin misexpression (enhancement of hypopigmentation phenotypes in the absence of gross defects in eye morphology) were in marked contrast with those of hypomorphic mutations (rough eye phenotype with no detectable enhancement of pigmentation defects). At least two alternative mechanisms should be considered. One possibility is that the phenotypic enhancement effect was a consequence of excessive Auxilin function, e.g. clathrin disassembly, in a sensitized background where trafficking to the pigment granule was already compromised due to deficiencies in BLOC-1 or AP-3. Another possibility is that the effect was a consequence of interference with the function of one or more Auxilin-binding partners. These two alternatives are not mutually exclusive. Furthermore, our results using Auxilin mutant variants revealed instances in which the structural determinants for Auxilin to enhance the phenotypes caused by BLOC-1 and AP-3 deficiency were not identical, implying the existence of more than one mechanism and/or site of action. Thus, a free carboxyl terminus and the two DPF motifs seemed to be more critical for the effects elicited in BLOC-1-deficient flies than for those in AP-3-deficient flies. Although mutations of the DPF motifs are predicted to impair interaction with the AP-2 complex involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis (87), it should be noted that in mammals one of the DPF motifs in auxilin 2 overlaps with a binding site for the related AP-1 complex (88), which like AP-3 has been implicated in LRO biogenesis (15,85). Hence, a conservative conclusion from our results is that the ability of Auxilin to interact with one or more AP complexes may be required for its function as a modifier of BLOC-1 function.

Could any of these genetic interactions involving BLOC-1 in flies be of relevance to its postulated role in schizophrenia? While it is not yet clear which human protein represents the orthologue of Claret (56), there are two human genes (RAB11A and RAB11B) encoding counterparts of fly Rab11 and two (DNAJC6 and GAK) encoding counterparts of fly Auxilin. To our knowledge, none of these genes has been investigated specifically as a genetic risk factor for the disease. However, a recent proteomics analysis of post-mortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reported elevated levels of brain auxilin (DNAJC6 gene product) in samples from schizophrenic patients (89), which we find intriguing considering another recent report of reduced dysbindin protein in the same region (44) and our finding of phenotypic enhancement elicited by increased Auxilin levels in BLOC-1-deficient flies. In principle, the functions reported for Rab11 and mammalian auxilin in brain would be compatible with some of the roles postulated for BLOC-1/dysbindin. For example, Rab11 has been implicated in brain development through its role in polarized neurite outgrowth (90), a process in which mammalian BLOC-1 has been implicated as well (35). In addition, brain auxilin is best known for its role in clathrin-dependent recycling of synaptic vesicles (91), and accumulating evidence argues for a role of mammalian BLOC-1 in synaptic vesicle biogenesis and/or dynamics (29,36). Given these considerations, it seems clear that these genetic interactions should deserve further research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein sequence analyses

Homology searches were performed by means of the PSI-BLAST algorithm (61) available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information server (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), using the non-redundant protein sequences database and default parameters, except for the threshold E-value required to include new sequences in subsequent iterations, which was conservatively lowered to 9 × 10−4. Initial ‘queries’ consisted in full-length amino acid sequences of the following human BLOC-1 subunits (RefSeq accession numbers provided in parentheses): BLOS1 (NP_001478), BLOS2 isoform 1 (NP_776170), BLOS3 (NP_997715), cappuccino (NP_060836), dysbindin isoform a (NP_115498), muted (NP_958437), pallidin (NP_036520) and snapin (NP_036569). Potential orthologues encoded by the genome of Drosophila melanogaster were subsequently used as queries in PSI-BLAST searches aimed at verifying that the initial query sequence represented the closest human protein sequence. Amino acid sequence alignment was carried out using the MULTIALIN algorithm (92) as available at the Network Protein Sequence Analysis server of the Pòle Bioinformatique Lyonnais (http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_multalin.html).

DNA constructs

The pCarUSVyr vector was derived from a modified Carnegie 4 vector (kindly provided by Pamela K. Geyer) that carries intronless yellow as the genetic marker (93). The majority of the polylinker of the modified Carnegie 4 vector was removed and replaced with a BamHI fragment containing the UAS-MCS-SV40 module of pUAST (94), which was added by blunt-end ligation. For transgenic expression of Blos1 in flies, the complete ORF of Blos1 from Drosophila melanogaster (GenBank NM_166060) plus the five nucleotides upstream of the translation initiation codon were amplified by reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT–PCR) from total RNA isolated from Canton-S flies, and engineered for cloning into the NotI–XbaI sites of the pCarUSVyr vector. For Y2H analyses, the resulting plasmid was used as a template for PCR engineering of the ORF (without upstream nucleotides) and cloning into the EcoRI–SalI sites of the pGBT9 and pGAD424 vectors (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). Other Y2H constructs generated in both pGBT9 and pGAD424 comprised the complete ORFs of the following Drosophila melanogaster proteins: Blos2 (GenBank NM_140170; PCR from Canton-S genomic DNA; cloned into EcoRI–BamHI), Pallidin (GenBank NM_140237; RT–PCR from S2 cell total RNA; cloned into EcoRI–SalI), Snapin (GenBank NM_164499; PCR from Canton-S genomic DNA; cloned into EcoRI–SalI), Blos4 (GenBank NM_140157; engineered from BDGP Gold cDNA RE17115; cloned into EcoRI–SalI), Dysbindin (GenBank NM_140807; engineered from BDGP Gold cDNA RE09163; cloned into SalI–BamHI) and Muted (GenBank NM_001043279; engineered from BDGP Gold cDNA RE40914; cloned into EcoRI–SalI). The control Y2H constructs Dp71(CC) and α-DBN(CC) in both pGBT9 and pGAD424 vectors were described previously (95). For the generation of constructs encoding mutant forms of the Drosophila Auxilin CJ fragment, the CJ fragment fused to mRFP (58) was first cloned into the pGEX-6p-1 vector (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ, USA) and subjected to multiple rounds of mutagenesis using the QuikChange® II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) to replace two DLL motifs (comprising residues 802–804 and 831–833) to DAA and/or two DPF motifs (comprising residues 868–870 and 920–922) to APA. Each of the mutated fragments was then subcloned as EcoRI–NotI fragments into pUAST (94). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Yeast-two-hybrid assay

Co-transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109 with pairs of Y2H constructs, selection of double transformants and growth assay were carried out as described elsewhere (96).

Fly stocks

The following fly stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN, USA): cm1 (AP-3 μ3 mutant), rb1 (AP-3 β3 mutant), ca1 (Claret mutant), y1 w67c23; P{EPgy2}EY06269 (referred herein to as ‘EY06269’), y1 w67c23; P{EPgy2}EY16920 (for potential misexpression of the product of CG5745), w1118; P{EP}CG9139EP681a P{EP}slmbEP681b (for potential misexpression of the product of CG9139). y1 w67c23; P{EPgy2}EY00704 (for potential misexpression of the product of CG12241), y1 w67c23; P{EPgy2}CG5903EY11938 (for potential misexpression of the product of CG5916) and y1 w67c23; P{EPgy2}CG17184EY11874 (for potential misexpression of the product of CG17184). The following stocks were obtained from the Exelixis Collection at Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA, USA): PBac{WH}CG5342f05247 (for potential misexpression of the product of wkd), P{XP}Rab11d01994 (for potential misexpression of Rab11; referred herein to as ‘P-element insertion 1’) and P{XP}Rab11d04643 (for potential misexpression of Rab11; referred herein to as ‘P-element insertion 2’). Transgenic flies carrying UAS-w were kindly provided by Paul T. Tarr and Peter A. Edwards (71). Flies carrying the GMR-GAL4 driver on the third chromosome were kindly provided by George R. Jackson (69). The following transgenic flies carrying RNAi constructs under the control of UAS (70) were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (Vienna, Austria): Transformant ID 34354 (to target CG6856), Transformant ID 23322 (to target CG14133) and Transformant ID 24851 (to target CG14149). The sources of all other fly stocks were described elsewhere (49,57,58,73,83).

Generation of transgenic flies

Transgenic flies were generated by P-element-mediated transformation into w1118 fly embryos; microinjection of embryos with UAS-blos1 and UAS-aux constructs was performed at the Duke University Model System Genomics facility (Durham, NC, USA) and Rainbow Transgenic Flies (Newbury Park, CA, USA), respectively.

Imprecise excision mutagenesis

To generate blos1 mutant alleles, the P-element carried by the fly line EY06269 was excised with the aid of Δ2-3 transposase (68) as previously described (49). Homozygous fly lines resulting from independent excision events were screened by PCR to identify those in which imprecise removal of the P-element resulted in genomic deletions at the blos1 locus. Prior to phenotypic characterization, the resulting blos1 mutant lines were partially ‘cantonized’ by 5–10 consecutive outcrosses into the genetic background of Canton-S. A variation of this strategy was used to generate a fly line carrying the GMR-GAL4 driver without of the ‘mini-white’ (w+mC) marker. In brief, flies carrying GMR-GAL4 along with mini-white on the third chromosome (69) were crossed with flies carrying Δ2-3, and the F1 progeny was crossed with flies carrying third-chromosome balancers to select individuals lacking Δ2-3 and carrying modified third chromosomes in which excision had resulted in loss of mini-white activity (as judged by lack of eye color on a w-null mutant background); those flies were then subjected to test crosses with female flies carrying UAS-w on a w-null background, to select those that had retained GMR-GAL4 activity (as judged by complementation of eye-color phenotype through expression of White from the UAS-w transgene). Two lines carrying modified GMR-GAL4 drivers devoid of mini-white were obtained. One of them elicited a ‘patchy’ expression pattern in the retina and was discarded; the other line was able to drive a more homogeneous expression of a reporter gene in the fly eye (for example, see Supplementary Material, Fig. S3) and was chosen for the experiments described herein.

Double mutant flies

Homozygous double mutant D. melanogaster lines were generated by standard genetic crosses using appropriate balancer chromosomes, except for the blos1ex2, ltd1 line, which required a recombination event owing to the location of both blos1 and ltd on the second chromosome. Briefly, the progeny of heterozygous blos1ex2/ltd1 females was screened by test crosses for recombinants that failed to complement the eye color phenotypes of both blos1ex2 and ltd1 single mutants.

Quantification of eye pigments

Red (pteridines) and brown (ommochromes) pigments were extracted from pools of heads of adult male flies, collected 2–3 days after eclosion and quantified as previously described (49). Results were expressed as percentages of the pigment content of Canton-S flies, which in each experiment were analyzed in parallel.

Light and electron microscopy

Light microscopy of unstained fly head sections was carried out as described (49). For electron microscopy, dissected fly heads were first fixed overnight at room temperature in 3.5% (w/v) glutaraldehyde and 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde solution in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), washed with phosphate buffer, incubated for 1 h in 2% (w/v) OsO4 solution in phosphate buffer, washed with deionized H2O and stained en bloc with 2% (w/v) aqueous uranyl acetate, overnight at 4°C. Stained samples were subsequently washed in deionized H2O, dehydrated through a series of aqueous solutions of increasing ethanol concentration, treated with propylene oxide and finally embedded in Eponate 12 resin (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA). Approximately 60–70 nm thick sections were cut on a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E ultramicrotome and picked up on formvar coated copper grids. Sections were collected at 1 µm intervals starting 5 µm below the surface of the eye. The sections were stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate and Reynolds lead citrate and examined on a JEOL 100CX electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 80 kV.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiology was performed as previously described (79). Briefly, wandering third-instar larvae were dissected under HL-3 saline solution (115 mm sucrose, 70 mm NaCl, 20 mm MgCl2, 10 mm NaHCO3, 5 mm HEPES, 5 mm KCl, 5 mm trehalose, pH 7.2) containing 0.25 mm CaCl2, and then washed and recorded in the same solution containing 0.6 mm CaCl2. Intracellular recordings were made from muscle 6 in segments A3 and A4, using sharp electrodes with tip resistances of 17–27 MOhms when filled with 3 M KCl. Cells were selected for analysis if the resting membrane potential was below −60 mV and the muscle input resistance was at least 5 MOhms. Spontaneous mEJP events were measured using MiniAnal software (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA, USA). Seventy consecutive events were measured, eliminating events with slow rise times that originated from the neighboring muscles. For EJP events, the cut segmental nerve was stimulated 100 times at 2 Hz and the last 75 events were averaged for each cell.

Fly behavioral assays

Fly behavior was examined as described elsewhere (72). Briefly, groups of 25 young adult male flies (5 ± 2 days old) were placed inside plastic Petri dishes (60 × 15 mm), incubated at 37°C for 60 min and then at 22°C for 2–4 h under high humidity conditions, and then monitored visually for 10 min. The courtship index was calculated as the number of males engaged in ‘courtship chains’ (not counting the chain leader), whereby males pursuing other males displayed at least one of the following: a wing at 90 degrees from the body, sampling of genitalia with the proboscis and attempted copulation. The total number of times that a male approached another male for any reason—including aggression—was also counted.

Immunoblotting

Dissected fly heads were homogenized in Laemmli sample buffer as previously described (49) and analyzed by immunoblotting using a DsRed polyclonal antibody (Clontech) to detect mRFP-fusion proteins and a monoclonal antibody anti-HSP70, clone BRM-22 (SigmaAldrich) to detect endogenous Hsp70 as a loading control.

Statistical analyses

Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) except for electrophysiological data, which were analyzed using Origin (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported by the American Heart Association (0855092F to E.C.D.), the National Institutes of Health (NS043171 to A.D.), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (to V.K.L.) and the American Cancer Society (RSG-07-175-01-CSM to H.C.C.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to Marianne Cilluffo and colleagues at the UCLA Brain Research Institute Microscopic Techniques and Electron Microscopy core facilities for their help with the preparation of histological samples for light and electron microscopy. We also thank Pamela K. Geyer, Paul T. Tarr, Peter A. Edwards and George R. Jackson for kindly providing reagents.

Conflict of Interest statement: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perret E., Lakkaraju A., Deborde S., Schreiner R., Rodriguez-Boulan E. Evolving endosomes: how many varieties and why? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:423–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olkkonen V.M., Ikonen E. When intracellular logistics fails—genetic defects in membrane trafficking. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:5031–5045. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saksena S., Emr S.D. ESCRTs and human disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009;37:167–172. doi: 10.1042/BST0370167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dell'Angelica E.C. AP-3-dependent trafficking and disease: the first decade. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dell'Angelica E.C. The building BLOC(k)s of lysosomes and related organelles. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raposo G., Marks M.S. Melanosomes—dark organelles enlighten endosomal membrane transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:786–797. doi: 10.1038/nrm2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huizing M., Helip-Wooley A., Westbroek W., Gunay-Aygun M., Gahl W.A. Disorders of lysosome-related organelle biogenesis: clinical and molecular genetics. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2009;9:359–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dell'Angelica E.C., Shotelersuk V., Aguilar R.C., Gahl W.A., Bonifacino J.S. Altered trafficking of lysosomal proteins in Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome due to mutations in the β3A subunit of the AP-3 adaptor. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li W., Zhang Q., Oiso N., Novak E.K., Gautam R., O'Brien E.P., Tinsley C.L., Blake D.J., Spritz R.A., Copeland N.G., et al. Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome type 7 (HPS-7) results from mutant dysbindin, a member of the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex 1 (BLOC-1) Nat. Genet. 2003;35:84–89. doi: 10.1038/ng1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan N.V., Pasha S., Johnson C.A., Ainsworth J.R., Eady R.A., Dawood B., McKeown C., Trembath R.C., Wilde J., Watson S.P., et al. A germline mutation in BLOC1S3/reduced pigmentation causes a novel variant of Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome (HPS8) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;78:160–166. doi: 10.1086/499338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anikster Y., Huizing M., White J., Shevchenko Y.O., Fitzpatrick D.L., Touchman J.W., Compton J.G., Bale S.J., Swank R.T., Gahl W.A., et al. Mutation of a new gene causes a unique form of Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome in a genetic isolate of central Puerto Rico. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:376–380. doi: 10.1038/ng576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Q., Zhao B., Li W., Oiso N., Novak E.K., Rusiniak M.E., Gautam R., Chintala S., O'Brien E.P., Zhang Y., et al. Ru2 and Ru encode mouse orthologs of the genes mutated in human Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome types 5 and 6. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:145–153. doi: 10.1038/ng1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hearing V.J. Biogenesis of pigment granules: a sensitive way to regulate melanocyte function. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2005;37:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huizing M., Sarangarajan R., Strovel E., Zhao Y., Gahl W.A., Boissy R.E. AP-3 mediates tyrosinase but not TRP-1 trafficking in human melanocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:2075–2085. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.7.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theos A.C., Tenza D., Martina J.A., Hurbain I., Peden A.A., Sviderskaya E.V., Stewart A., Robinson M.S., Bennett D.C., Cutler D.F., et al. Functions of adaptor protein (AP)-3 and AP-1 in tyrosinase sorting from endosomes to melanosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:5356–5372. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richmond B., Huizing M., Knapp J., Koshoffer A., Zhao Y., Gahl W.A., Boissy R.E. Melanocytes derived from patients with Hermansky–Pudlak Syndrome types 1, 2 and 3 have distinct defects in cargo trafficking. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005;124:420–427. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23585.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]