Abstract

The histone-like protein HU is a highly abundant DNA architectural protein that is involved in compacting the DNA of the bacterial nucleoid and in regulating the main DNA transactions, including gene transcription. However, the coordination of the genomic structure and function by HU is poorly understood. Here, we address this question by comparing transcript patterns and spatial distributions of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli wild-type and hupA/B mutant cells. We demonstrate that, in mutant cells, upregulated genes are preferentially clustered in a large chromosomal domain comprising the ribosomal RNA operons organized on both sides of OriC. Furthermore, we show that, in parallel to this transcription asymmetry, mutant cells are also impaired in forming the transcription foci—spatially confined aggregations of RNA polymerase molecules transcribing strong ribosomal RNA operons. Our data thus implicate HU in coordinating the global genomic structure and function by regulating the spatial distribution of RNA polymerase in the nucleoid.

Keywords: RNA polymerase, DNA supercoiling, stable RNA operons, transcription foci, replication origin

Introduction

In the classical model organism Escherichia coli, the transcriptional regulatory network comprises hundreds of dedicated transcription factors expressed at low levels and binding to a few specific sites located in gene promoter regions. However, a different regulatory effect is exerted by abundant nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs), the bacterial counterparts of histones, which stabilize long-range structures by cooperative binding of multiple genomic sites (Azam & Ishihama, 1999; Dame, 2005). The unique feature of the regulatory effect of NAPs is in modulating the accessibility of free DNA supercoils to transcription machinery by modulating the state of DNA compaction (Travers & Muskhelishvili, 2005a). The nucleoprotein structures stabilized by NAPs thus engage neighbouring loci in continuous or ‘analogue' transcriptional control. This regulation converts the fluctuations in DNA supercoil energy into transcript patterns, as opposed to the ‘digital' type of control exerted by dedicated regulators targeting a few specific sites (Blot et al, 2006; Marr et al, 2008). Importantly, analogue control involves cross-talk between NAPs and DNA topoisomerases, adjusting the DNA supercoiling and instant cellular metabolism, and thus optimizing bacterial adaptation (Travers & Muskhelishvili, 2005b).

NAPs have been shown to sustain supercoiling homeostasis, and to organize dynamic topological domains and spatial transcript patterns in the genome (Hardy & Cozzarelli, 2005; Blot et al, 2006; Marr et al, 2008). The DNA binding preferences and structures stabilized by the main NAPs differ (Azam & Ishihama, 1999; Pinson et al, 1999; Dame et al, 2001). The global repressor H-NS (histone-like nucleoid structuring protein) stabilizes tight plectonemic DNA interwindings consistent with silencing (Dorman, 2004; Maurer et al, 2009), whereas the main NAP HU (histone-like protein)—which is a heterodimer of HUα and HUβ proteins in E. coli—constrains dynamic toroidal supercoils supporting transcription (Rouviere-Yaniv et al, 1979; Broyles & Pettijohn, 1986).

A previous study implicated HU in replication initiation and chromosomal partitioning (Jaffe et al, 1997). Initiation of OriC replication was shown to require both HU and high negative superhelicity (Dixon & Kornberg, 1984; Crooke et al, 1991). Recent studies have revealed alterations of the nucleoid condensation and transcription in a gain-of-function HUα mutant (Kar et al, 2005), and also a role for the supercoil-constraining capacity of HU in gene regulation (Oberto et al, 2009). However, a clear understanding of the impact of HU in coordinating genomic structure and function is still lacking. In this study, we address this question by investigating the transcript patterns and distributions of RNA polymerase (RNAP) molecules in nucleoids of wild-type and hupA/B mutant E. coli cells.

Results

Using DNA microarrays, we compared the genomic expression patterns of E. coli CSH50 wild-type and hupA/B mutant strains. Notably, while the growth defect observed in the hupA/B mutant depends on the growth medium and oxygen availability (Oberto et al, 2009), under our conditions cells grew at similar rates, but the mutant demonstrated a prolonged lag phase (data not shown). Clustering of the differentially expressed genes in gene ontology (GO) groups revealed that, despite differences in experimental conditions and applied analyses, affected functions are largely consistent with a recent report (Oberto et al, 2009), that indicated a global reorganization of transcription (supplementary Tables S1 and S2 online). However, the genomic distribution of differentially expressed genes also revealed a striking spatial asymmetry. In a wild-type background, upregulated genes—that is, genes with positive log ratios—were predominantly clustered in a large chromosomal region comprising the replication terminus (Ter). However, upregulated genes in the mutant were clustered in a comparable region comprising OriC with ribosomal RNA operons (rrn), and were apparently delimited by distal operons rrnG and rrnH on both replichores (Fig 1A). We ruled out the effects of gene dosage on the observed pattern because, consistent with previous findings (Jaffe et al, 1997), the OriC/Ter DNA ratios in wild-type and hupA/B mutant cells were similar (supplementary Fig S1 online).

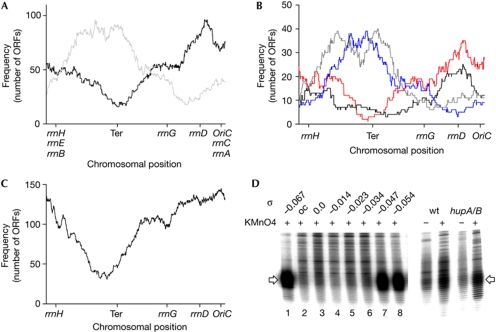

Figure 1.

Spatial reorganization of transcription in cells lacking the histone-like protein HU. (A) Frequency distribution of gene transcripts upregulated in wild-type (grey) and hupA/B (black) backgrounds. (B) Frequency distributions of upregulated transcripts associated with DNA relaxation (grey) and high negative supercoiling (blue) in wild-type and hupA/B mutant cells (black and red, respectively). (C) Genomic distribution of gyrase-binding sites (Jeong et al, 2004). All frequency distributions were obtained by averaging, using a sliding window of 200 ORFs. Chromosomal positions of ribosomal RNA operons, OriC and Ter are indicated. (D) Dependence of cruciform formation (arrows) in (AT)34 reporter plasmids on the superhelical density (σ) in vitro (left panel, lanes 1–8). The indicated σ values are within 15% of precision. Detection of cruciforms in exponentially growing wild-type and hupA/B mutant cells (right panel). 0.0, fully relaxed DNA template; oc, open circular form; ORFs, open reading frames; OriC, replication origin; rrn, ribosomal RNA operons; Ter, replication terminus; wt, wild type.

Analyses of the supercoiling dependence of the transcripts using a published data set (Blot et al, 2006) showed that hupA/B mutant upregulated genes preferentially use high negative superhelicity (Fig 1B; it should be noted that for technical reasons rrn genes are not included in our transcript patterns). Importantly, this pattern correlated with genomic distribution of DNA-binding sites for gyrase, the main enzyme introducing negative supercoils into the DNA (Fig 1C; Jeong et al, 2004).

As on prolonged cultivation, the cells lacking HU can acquire suppressor mutations in gyrase genes (Malik et al, 1996), we sequenced gyrA/B genes in hupA/B mutant and isogenic CSH50 wild-type parent, and also in the wild-type E. coli W3110 strain. In all three backgrounds, we found a C-to-G transversion at position 1,153 of the gyrB ATPase domain, substituting Pro 385 by alanine (data not shown). We believe this substitution represents a natural variation and consider it irrelevant to our observations. The cellular levels of GyrA and GyrB proteins in wild-type and mutant cells were also similar (supplementary Fig S2 online).

Our observation that upregulated genes in the hupA/B mutant preferentially use high negative superhelicity was intriguing because in this mutant the DNA-relaxing activity was seen to have increased in parallel with reduced overall negative superhelicity (Bensaid et al, 1996; Malik et al, 1996). However, whether the unconstrained supercoiling is also altered in the hupA/B mutant remains unknown. To clarify this point, we used plasmid constructs containing 34 bp AT tracts, adopting cruciform geometries under conditions of high negative superhelicity, as reporters to measure unconstrained negative supercoiling in vivo (Bowater et al, 1994). Probing of (AT)34 cruciforms in vitro over a range of superhelical densities (σ) by potassium permanganate reactivity assay showed a sharp transition in local DNA geometry between σ=−0.034 and σ=−0.047, and cruciform stabilization at σ >−0.047 (Fig 1D). In vivo, the (AT)34 cruciform formation could be detected in both hupA/B mutant and wild-type cells, indicating high levels of free superhelicity in both cases (σ at least >−0.034, as approximated from our in vitro data; Fig 1D). Thus, although global negative superhelicity is reduced in the hupA/B mutant (Malik et al, 1996), a high level of free superhelicity is sustained that is consistent with homeostatic regulation (Blot et al, 2006). These findings suggest a global readjustment of nucleoid structure and transcription in the hupA/B mutant.

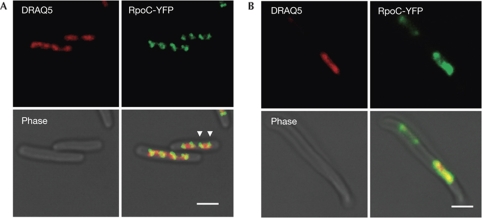

The most prominent structures associated with bacterial transcription are the transcription foci, representing local accumulations of RNAP transcribing the exceptionally strong ribosomal RNA (rRNA) operons (Cabrera & Jin, 2003, 2006). To test whether the spatial reorganization of transcription in the hupA/B mutant had any effect on the formation of transcription foci, we fused the rpoC gene encoding the β-subunit of RNAP with a yfp (yellow fluorescent protein) gene to produce a fluorescent protein and substituted the rpoC allele in both the wild-type and hupA/B cells. Laser scanning microscopy investigations of RpoC-YFP signal distribution in nucleoids revealed a regular pattern of transcription foci located close to nucleoid poles in exponentially growing wild-type cells (Fig 2A; supplementary Fig S3A online). By contrast, in hupA/B cells the RpoC-YFP signal was distributed more evenly throughout the nucleoid (Fig 2B; supplementary Fig S3B,C online). Unlike the HU mutant, cells lacking either H-NS, DNA protection during starvation or integration host factor were proficient in transcription foci formation (supplementary Fig S3D–F online). Unfortunately, we could neither delete the fis gene in the rpoC-yfp background, nor introduce the rpoC-yfp allele in a fis mutant. However, mutations of the main NAPs, including factor for inversion stimulation, did not induce transcription asymmetry similar to hupA/B (Blot et al, 2006; G.M., unpublished data).

Figure 2.

Exponentially growing hupA/B mutant cells are impaired in foci formation. (A) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of wild-type cells showing RNAP-dense areas (foci) at the poles of the nucleoid (white arrowheads; only two positions are indicated). (B) Representative image of a hupA/B mutant cell. It should be noted that RNAP is more evenly distributed in the nucleoid. Fluorescence images of RpoC-YFP (RNAP), DRAQ5 (nucleoid) and phase-contrast images are shown. In the merged images, green is the RpoC-YFP fluorescence signal, and red is the DRAQ5 fluorescence signal. Scale bars, 2 μm. RNAP, RNA polymerase; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

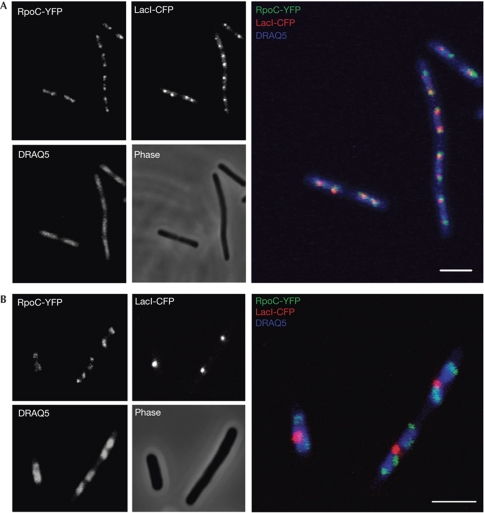

As the transcription asymmetry features a large region comprising OriC and rRNA operons, whereas the transcription foci confine these operons, we asked whether the transcription foci are associated with OriC. We used lac operator arrays inserted in the vicinity of either OriC or Ter as markers, and visualized them by expressing a fluorescent Lac repressor-CFP (cyan fluorescent protein) fusion from the pLAU53ÄtetR plasmid construct (Lau et al, 2003). These cells also carried a chromosomal rpoC-yfp allele, which enabled us to co-localize the LacR-CFP and RpoC-YFP signals in the nucleoid. We found that in exponentially growing wild-type cells the pattern of RpoC-YFP signals was similar to that of OriC, but not of Ter (compare Fig 3A and Fig 3B). From these data, we infer that the OriC and transcription foci are located in close vicinity in wild-type cells, whereas in the hupA/B mutant, which exhibits a more even distribution of RNAP in the nucleoid, this organizational capacity is lost (Fig 2B; supplementary Fig S4 online).

Figure 3.

Transcription foci localize near OriC at opposite poles of the nucleoid. (A) Fluorescence microscopy image of wild-type cells carrying the rpoC-yfp fusion allele and 240 tandem lac operator insertions at position 3,908 kb close to OriC (Lau et al, 2003). Fluorescence images of RpoC-YFP (RNAP), LacI-CFP (OriC), DRAQ5 (nucleoid) and phase-contrast images are shown in greyscale on the left. Merge images are shown on the right: green is the RpoC-YFP fluorescence signal; red is LacI-CFP; and blue is DRAQ5 fluorescence signal. Scale bar, 2 μm. (B) Images of wild-type cells carrying the rpoC-yfp fusion allele and 240 tandem lac operator insertions at position 1,801 kb close to Ter. CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; RNAP, RNA polymerase; Ter, replication terminus; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

Discussion

Here, we show that the formation of transcription foci as confined structures of the nucleoid is dependent on HU, and the absence of foci in the hupA/B mutant correlates with a spatially rearranged transcript pattern. The boundaries of this pattern closely coincide with distal rrn operons on both replichores, delimiting a chromosomal domain of >2 Mb in extent, which we denote as the rrn macrodomain for convenience. The spatial organization of the rrn macrodomain is in keeping with chromosomal macrodomains identified previously by an approach based on measurements of site-specific recombination events in the chromosome (Valens et al, 2004). An initial estimate is that the extent of the rrn macrodomain corresponds to the previously defined OriC macrodomain, including either large parts or most of the two flanking less-structured domains (Fig 4A). Concomitant segregation of OriC with flanking less-structured macrodomains observed in a recent study (Espeli et al, 2008) is consistent with this idea. As rrn operons are transcribed coordinately (French & Miller, 1989), it is possible that they are all involved in foci formation. The impaired foci formation in the hupA/B mutant on the one hand, and spatial vicinity of the foci and OriC in the wild-type cells on the other, suggests a loss of the structural–organizational integrity of the rrn macrodomain in the hupA/B mutant. The corollary is that HU coordinates rRNA production and OriC replication.

Figure 4.

Domain organization of the genome. (A) Approximate spatial arrangement of the rrn macrodomain with respect to the chromosomal macrodomains determined by Valens et al (2004). (B) A model of nucleoid structure organization by HU. At stable RNA operons, the negative twist introduced into the DNA by more than 50 transcribing polymerases (French & Miller, 1989) constrains, in a closed topological domain of about 5 kb in size, a high negative superhelical density (at −σ=∼0.1) with compensatory increase in positive superhelicity. Constraint of these positive supercoils (+) by HU acts as a ‘topological sink' buffering the diffusion of positive superhelicity and stabilizing transcription (left panel). In the absence of HU, the increased accessibility of gyrase-binding sites in the rrn macrodomain imposes an imbalance on supercoil distribution and asymmetry on genomic transcription (right side). NS, non-structured macrodomains; rrn, ribosomal RNA; Ter, replication terminus; wt, wild type.

The role of HU in stabilizing transcription foci

HU is evenly distributed in the nucleoid and binds equally well to the DNA sites in the OriC and Ter regions in vivo (Azam et al, 2000; Wery et al, 2001; Preobrajenskaya et al, 2005; supplementary Fig S5 online), making it difficult to implicate differential binding of HU in generating spatial asymmetry. Similarly, this asymmetry cannot be explained by gene dosage effects or by altered gyrase content in the hupA/B mutant (supplementary Figs S1 and S2 online). A previous study proposed the association of HU with RNAP in the nucleoid (Dürrenberger et al, 1988), but we do not necessarily infer direct interactions. It is noteworthy that the supercoils constrained by HU are highly dynamic (Broyles & Pettijohn, 1986). In a co-crystal structure, the HU dimer introduces a positive twist into the DNA (Swinger et al, 2003) and an octamer of HU presumably constrains left-handed toroidal coils (Guo & Adhya, 2007), whereas hyperactive HUα can constrain right-handed supercoils (Kar et al, 2006). We propose, therefore, that constraint of free DNA supercoils generated during the transcription of rrn operons by HU generates metastable structures that maintain the integrity of the foci and any dependent higher-order structures that—by virtue of spatial proximity—might contain OriC. The constraint of DNA supercoils by HU could act as a ‘topological sink' preventing the diffusion of positive superhelicity and stabilizing the transcription foci (Fig 4B, left side). This metastable structure would thus function as a counting device and, therefore, its extent and also the presence of the foci themselves will depend on continuing transcription. This model is fully consistent with the properties of the hyperactive HUα mutant that not only increases growth rate but also has an enhanced ability to constrain positive supercoils (Kar et al, 2005, 2006).

In the absence of HU, the negative supercoils generated during transcription are probably more accessible to DNA-relaxing topoisomerases (Bensaid et al, 1996). However, in the rrn macrodomain, this relaxation could be counterbalanced both by strong transcription of rrn operons and by enrichment of binding sites for gyrase relaxing the positive supercoils. Both these effects would maintain free negative superhelicity available for transcription in the rrn macrodomain as opposed to the comparable region comprising Ter, which is devoid of strong rrn operons and is also less rich in gyrase-binding sites (Fig 4B, right side). Notably, an asymmetrical distribution of topoisomerase I sites has been implicated in spatial coordination of the replication complex and topoisomerase action in simian virus 40 DNA (Porter & Champoux, 1989).

We propose that perturbation of topological homeostasis due to the loss of HU is compensated by accessibility of DNA-binding sites to gyrase, which not only sustains high negative superhelicity required for optimal rRNA transcription and OriC replication (Crooke et al, 1991; Travers & Muskhelishvili, 2005b), but also imposes a spatial pattern on transcription (Jeong et al, 2004). Such increased dependency on gyrase explains both the occurrence of gyrase suppressors of HU deficiency and also the hypersensitivity of the HU mutant to gyrase inhibitor novobiocin (Malik et al, 1996). We are now designing genetic reporters to test this hypothesis.

Methods

Strains and plasmids. The wild-type and mutant CSH50 E. coli K12 strains were grown in 2 × YT medium at 37°C, all samples were taken at an absorbance of A600=0.4–0.6. Genotype and construction details of all strains and plasmids are provided in the supplementary information online.

DNA microarray analysis. Transcript profiling for wild-type and hupA/B strains were carried out using E. coli DNA microarrays (Ocimum Biosolutions, Hyderabad, India) as described previously (Blot et al, 2006). The GOstat programme was used to generate statistics on GO terms overrepresented in the transcript profiles (supplementary information online). To visualize the chromosomal distributions of transcript profiles and gyrase-binding sites, positional bins were counted using a sliding window of 200 open reading frames. Two publicly available data sets were used to identify supercoiling sensitive gene transcripts and distributions of gyrase-binding sites (Jeong et al, 2004; Blot et al, 2006). For details, see the supplementary information online. The ArrayExpress accession number is E-MEXP-1742.

Potassium permanganate assay. The preparation of plasmid topoisomers, high-resolution DNA electrophoresis and determinations of σ were carried out as described by Schneider et al (2000). Potassium permanganate reactivity assays in vitro and in vivo were carried out according to Schneider et al, (1999) and Hatoum & Roberts (2008), respectively.

Confocal scanning microscopy. Cells were fixed with formaldehyde as described previously (Cabrera & Jin, 2003), but in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and incubated on ice for 5 min before being transferred to 18°C for 1 h. Fixed cells were re-suspended in phosphate buffered saline and fluorescent DNA dye DRAQ5 was added to 50 μM before mounting the suspension on glass slides. Cells were viewed with a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 510 Meta, Carl Zeiss Jena GmbH, Jena, Germany) equipped with argon and helium–neon mixed-gas lasers at excitation wavelengths of 458, 514 or 633 nm. Scans were taken at a resolution of 1,024 pixels × 1,024 pixels in the line-averaging mode. Image analysis was performed using the LSM 510 software release 3.0 (Carl Zeiss Jena GmbH).

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank David Sherratt for providing bacterial strains for the fluorescent repressor-operator assay, David Lilley for the (AT)34 constructs, Sebastian Maurer for help with model drawing and Frank-Oliver Glöckner for providing a platform for microarray analysis. This study was financially supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to G.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Azam TA, Ishihama A (1999) Twelve species of the nucleoid-associated protein from Escherichia coli. Sequence recognition specificity and DNA binding affinity. J Biol Chem 274: 33105–33113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam TA, Hiraga S, Ishihama A (2000) Two types of localization of the DNA-binding proteins within the Escherichia coli nucleoid. Genes Cells 5: 613–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensaid A, Almeida A, Drlica K, Rouviere-Yaniv J (1996) Cross-talk between topoisomerase I and HU in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 256: 292–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blot N, Mavathur R, Geertz M, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G (2006) Homeostatic regulation of supercoiling sensitivity coordinates transcription of the bacterial genome. EMBO Rep 7: 710–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowater RP, Chen D, Lilley DM (1994) Elevated unconstrained supercoiling of plasmid DNA generated by transcription and translation of the tetracycline resistance gene in eubacteria. Biochemistry 33: 9266–9275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broyles SS, Pettijohn DE (1986) Interaction of the Escherichia coli HU protein with DNA. Evidence for formation of nucleosome-like structures with altered DNA helical pitch. J Mol Biol 187: 47–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera JE, Jin DJ (2003) The distribution of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli is dynamic and sensitive to environmental cues. Mol Microbiol 50: 1493–1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera JE, Jin DJ (2006) Active transcription of rRNA operons is a driving force for the distribution of RNA polymerase in bacteria: effect of extrachromosomal copies of rrnB on the in vivo localization of RNA polymerase. J Bacteriol 188: 4007–4014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooke E, Hwang DS, Skarstad K, Thöny B, Kornberg A (1991) E. coli minichromosome replication: regulation of initiation at oriC. Res Microbiol 142: 127–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dame RT (2005) The role of nucleoid-associated proteins in the organization and compaction of bacterial chromatin. Mol Microbiol 56: 858–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dame RT, Wyman C, Goosen N (2001) Structural basis for preferential binding of H-NS to curved DNA. Biochimie 83: 231–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon NE, Kornberg A (1984) Protein HU in the enzymatic replication of the chromosomal origin of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 424–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman CJ (2004) H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat Rev Microbiol 2: 391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dürrenberger M, Bjornsti MA, Uetz T, Hobot JA, Kellenberger E (1988) Intracellular location of the histonelike protein HU in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 170: 4757–4768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeli O, Mercier R, Boccard F (2008) DNA dynamics vary according to macrodomain topography in the E. coli chromosome. Mol Microbiol 68: 1418–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SL, Miller JR (1989) Transcription mapping of the Escherichia coli chromosome by electron microscopy. J Bacteriol 171: 4207–4216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Adhya S (2007) Spiral structure of Escherichia coli HUαβ provides foundation for DNA supercoiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 4309–4314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy CD, Cozzarelli NR (2005) A genetic selection for supercoiling mutants of Escherichia coli reveals proteins implicated in chromosome structure. Mol Microbiol 57: 1636–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatoum A, Roberts J (2008) Prevalence of RNA polymerase stalling at Escherichia coli promoters after open complex formation. Mol Microbiol 68: 17–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe A, Vinella D, D'Ari R (1997) The Escherichia coli histone-like protein HU affects DNA initiation, chromosome partitioning via MukB, and cell division via MinCDE. J Bacteriol 179: 3494–3499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong KS, Ahn J, Khodursky AB (2004) Spatial patterns of transcriptional activity in the chromosome of Escherichia coli. Genome Biol 5: R86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar S, Edgar R, Adhya S (2005) Nucleoid remodeling by an altered HU protein: reorganization of the transcription program. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 16397–16402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar S, Choi EJ, Guo F, Dimitriadis EK, Kotova SL, Adhya S (2006) Right-handed DNA supercoiling by an octameric form of histone-like protein HU: modulation of cellular transcription. J Biol Chem 281: 40144–40153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau IF, Filipe SR, Søballe B, Økstad OA, Barre FX, Sherratt DJ (2003) Spatial and temporal organization of replicating Escherichia coli chromosomes. Mol Microbiol 49: 731–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik M, Bensaid A, Rouviere-Yaniv J, Drlica K (1996) Histone-like protein HU and bacterial DNA topology: suppression of an HU deficiency by gyrase mutations. J Mol Biol 256: 66–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr C, Geertz M, Hütt MT, Muskhelishvili G (2008) Dissecting the logical types of network control in gene expression profiles. BMC Syst Biol 2: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer S, Fritz J, Muskhelishvili G (2009) A systematic in vitro study of nucleoprotein complexes formed by bacterial nucleoid associated proteins revealing novel types of DNA organization. J Mol Biol 387: 1261–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberto J, Nabti S, Jooste V, Mignot H, Rouviere-Yaniv J (2009) The HU regulon is composed of genes responding to anaerobiosis, acid stress, high osmolarity and SPOS induction. PLoS ONE 4: e4367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinson V, Takahashi M, Rouviere-Yaniv J (1999) Differential binding of the Escherichia coli HU, homodimeric forms and heterodimeric form to linear, gapped and cruciform DNA. J Mol Biol 287: 485–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter SE, Champoux JJ (1989) Mapping in vivo topoisomerase I sites on Simian virus 40 DNA: asymmetric distribution of sites on replicating DNA molecules. Mol Cell Biol 9: 541–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preobrajenskaya OV, Starodubova ES, Karpov VL, Rouviere-Yaniv J (2005) Assays on comparing the local concentration of HU protein in the different regions of Escherichia coli genomic DNA. Mol Biol (Mosk) 39: 678–686 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouviere-Yaniv J, Yaniv M, Germond JE (1979) E. coli DNA binding protein HU forms nucleosome-like structure with circular double-stranded DNA. Cell 17: 265–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R, Travers A, Kutateladze T, Muskhelishvili G (1999) A DNA architectural protein couples cellular physiology and DNA topology in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 34: 953–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R, Travers A, Muskhelishvili G (2000) The expression of the Escherichia coli fis gene is strongly dependent on the superhelical density of DNA. Mol Microbiol 38: 167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinger KK, Lemberg KM, Zhang Y, Rice PA (2003) Flexible DNA bending in HU–DNA cocrystal structures. EMBO J 22: 3749–3760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers A, Muskhelishvili G (2005a) Bacterial chromatin. Curr Opin Genet Dev 15: 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers A, Muskhelishvili G (2005b) DNA supercoiling—a global transcriptional regulator for enterobacterial growth? Nat Rev Microbiol 3: 157–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valens M, Penaud S, Rossignol M, Cornet F, Boccard F (2004) Macrodomain organization of the Escherichia coli chromosome. EMBO J 23: 4330–4341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wery M, Woldringh CL, Rouviere-Yaniv J (2001) HU–GFP and DAPI co-localize on the Escherichia coli nucleoid. Biochimie 83: 193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information