Abstract

Background

Recent evidence suggests that there is a link between metabolic diseases and bacterial populations in the gut. The aim of this study was to assess the differences between the composition of the intestinal microbiota in humans with type 2 diabetes and non-diabetic persons as control.

Methods and Findings

The study included 36 male adults with a broad range of age and body-mass indices (BMIs), among which 18 subjects were diagnosed with diabetes type 2. The fecal bacterial composition was investigated by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and in a subgroup of subjects (N = 20) by tag-encoded amplicon pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. The proportions of phylum Firmicutes and class Clostridia were significantly reduced in the diabetic group compared to the control group (P = 0.03). Furthermore, the ratios of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes as well as the ratios of Bacteroides-Prevotella group to C. coccoides-E. rectale group correlated positively and significantly with plasma glucose concentration (P = 0.04) but not with BMIs. Similarly, class Betaproteobacteria was highly enriched in diabetic compared to non-diabetic persons (P = 0.02) and positively correlated with plasma glucose (P = 0.04).

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that type 2 diabetes in humans is associated with compositional changes in intestinal microbiota. The level of glucose tolerance should be considered when linking microbiota with metabolic diseases such as obesity and developing strategies to control metabolic diseases by modifying the gut microbiota.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is a metabolic disease which primary cause is obesity-linked insulin resistance. However, some other factors like mental stress, infection and genetic predisposition might lead to diabetes as well [1]-[4]. Both obesity and diabetes are characterized by a state of chronic low-grade inflammation with abnormal expression and production of multiple inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor and interleukins [5]. Recent studies based on large-scale 16S rRNA gene sequencing and more limited techniques, based on quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), have shown a relationship between the composition of the intestinal microbiota and metabolic diseases like obesity and diabetes. For example, levels of Bifidobacterium significantly and positively correlated with improved glucose-tolerance and low-grade inflammation in prebiotic treated-mice [1], [6]. Furthermore, the development of diabetes type 1 in rats was reported to be associated with higher amounts of Bacteroides ssp. [7]. It has been proposed that the gut microbiota directed increased monosaccharide uptake from the gut and instructed the host to increase hepatic production of triglycerides associated with the development of insulin resistance [8].

Several studies on mice models and in humans provided evidence that increase in body weight was associated with a larger proportion of Firmicutes and relatively less Bacteroidetes [9]-[11]. In accordance with these results, Zhang and coworkers [12] demonstrated that Firmicutes were significantly decreased in post-gastric-bypass individuals, and Prevotellaceae highly enriched in obese individuals. The differences in microbial composition were explained by an increased capacity of the obesity-associated microbiome to harvest energy from the diet [13]. Controversial data were recently reported by Schwiertz and colleagues [14]. They determined lower ratios of Firmicutes to Bacterodetes in overweight human adults compared to lean controls. Another study, using weight loss diets, found no proof of the link between the proportion of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes and human obesity [15]. Consequently, the composition of obese microbiome is still questionable and more scientific evidence is needed to elucidate the relationship between the gut microbial composition and metabolic diseases.

Most of the published studies describe the differences between gut microbiota in obese compared to lean persons, while type 2 diabetes is generally considered as an attribute to obesity and thus far left behind as the focus of research. The objective of this study was to characterize the composition of fecal microbiota in adults with diabetes type 2 as compared to non-diabetic controls using tag-encoded amplicon pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene and qPCR.

Results

Subjects

Subjects with type 2 diabetes (N = 18) and non-diabetic controls (N = 18) were all males at age 31 to 73 years and body mass indices (BMIs) ranging from 23 to 48 (Table 1). The diabetic group had elevated concentration of plasma glucose as determined by a fasting oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Subject C17, though having high plasma glucose, was referred to the non-diabetic group based on the measurements of baseline glucose and biochemical analysis of blood samples. The two groups were comparable with regard to their characteristics.

Table 1. Characteristics of the diabetic subjects and controls in the study: age, body mass index (BMI) and plasma glucose concentration measured by oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).

| Subjects with diabetes type 2 (N = 18) | Control group (N = 18) | ||||||

| Subject ID | Age, Years | BMI Kg/m2 | OGTT glucose mmol/l | Subject ID | Age, Years | BMI Kg/m2 | OGTT glucose mmol/l |

| D1 | 40 | 24 | 25.8 | C1 | 34 | 25 | 4.8 |

| D2 | 51 | 48 | 27.9 | C2 | 54 | 27 | 4.2 |

| D3 | 69 | 25 | 13.3 | C3 | 60 | 24 | 3.8 |

| D4 | 62 | 27 | 20.6 | C4 | 68 | 39 | 3.5 |

| D5 | 42 | 34 | 20.5 | C5 | 39 | 31 | 5.5 |

| D6 | 72 | 23 | 22.1 | C6 | 58 | 33 | 4.7 |

| D7 | 53 | 23 | 24.7 | C7 | 55 | 39 | 4.6 |

| D8 | 31 | 43 | 20.6 | C8 | 52 | 24 | 5.4 |

| D9 | 54 | 33 | 19.0 | C9 | 58 | 27 | 5.3 |

| D10 | 52 | 25 | 18.1 | C10 | 72 | 27 | 5.1 |

| D11 | 36 | 36 | 8.8 | C11 | 70 | 29 | 6.5 |

| D12 | 64 | 22 | 12.1 | C12 | 43 | 25 | 3.2 |

| D13 | 76 | 27 | 19.3 | C13 | 59 | 23 | 5.2 |

| D14 | 61 | 28 | 15.0 | C14 | 68 | 28 | 5.6 |

| D15 | 60 | 32 | 22.0 | C15 | 74 | 23 | 4.5 |

| D16 | 65 | 27 | 8.8 | C16 | 65 | 32 | 4.2 |

| D17 | 49 | 31 | 17.4 | C17 | 64 | 24 | 9.2 |

| D18 | 73 | 23 | 18.7 | C18 | 63 | 24 | 4.0 |

| Mean (s.d.) | 56 (13) | 30 (7) | 18.6 (5.4) | Mean (s.d.) | 59 (11) | 28 (5) | 5.0 (1.3) |

Characterization of the Intestinal Microbiota by Tag-Encoded Pyrosequencing

The total number of reads obtained for 20 subjects by V4 16S rRNA pyrosequencing was 1028955. After applying quality control and trimming we obtained 382229 high quality sequences from diabetic persons and 357782 sequences from healthy controls, accounting for 71.9% of the total reads (Table 2). The number of sequences varied between the subjects from 10521 to 66999 with a mean of 37000 (SD 16062). The average sequence length of trimmed sequences was 234 bp.

Table 2. The number of sequences produced and equalized; the number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and richness estimates (Chao1) at 3% distance within fecal samples of the diabetic persons (D1-D10) and controls (C1–C10) as determined by pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene.

| Sample ID | Sequences produced | Sequences equalized | OTUs | Chao1 | Confidence interval (95%) |

| D1 | 41607 | 20000 | 1416 | 2487 | 2286–2736 |

| D2 | 36644 | 20000 | 1617 | 2868 | 2650–3133 |

| D3 | 49213 | 20000 | 934 | 1494 | 1364–1663 |

| D4 | 54663 | 20000 | 1396 | 2337 | 2161–2554 |

| D5 | 66097 | 20000 | 1776 | 3023 | 2814–3274 |

| D6 | 10521 | 10521 | 1140 | 1773 | 1643–1937 |

| D7 | 26874 | 20000 | 1022 | 1605 | 1472–1777 |

| D8 | 27581 | 20000 | 1415 | 2161 | 2016–2340 |

| D9 | 27768 | 20000 | 1985 | 3127 | 2939–3352 |

| D10 | 41261 | 20000 | 1233 | 1971 | 1823–2157 |

| C1 | 28126 | 20000 | 1846 | 3049 | 2851–3286 |

| C 2 | 42207 | 20000 | 1516 | 2452 | 2279–2665 |

| C3 | 30701 | 20000 | 2473 | 4269 | 4010–4571 |

| C4 | 55678 | 20000 | 1411 | 2122 | 1981–2298 |

| C5 | 27204 | 20000 | 1079 | 1689 | 1555–1861 |

| C6 | 48719 | 20000 | 1595 | 2527 | 2360–2730 |

| C7 | 22794 | 20000 | 2254 | 3769 | 3535–4047 |

| C8 | 17080 | 17080 | 824 | 1184 | 1094–1304 |

| C9 | 18274 | 18274 | 456 | 655 | 589–755 |

| C10 | 66999 | 20000 | 1322 | 1911 | 1793–2059 |

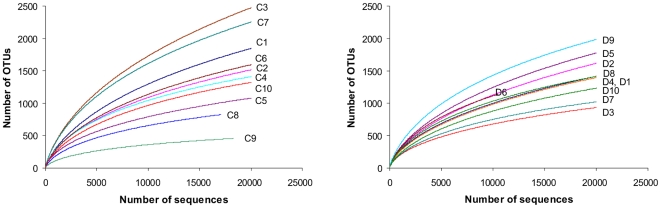

The mean bacterial diversity, as estimated by Chao1 indices from the equalized data sets (Table 2), was not different between the diabetic subjects and the controls, comprising 2287 (SD 587) and 2363 (SD 1113), respectively. However, the variability of Chao1 estimates between the diabetic subjects (Chao1 from 1364 to 2939) was lower compared to the controls (Chao1 from 589 to 4010). As shown by the rarefactions curves, bacterial diversity and richness in diabetic subjects with BMI more than 31 (Figure 1, D2, D5, D8 and D9) was somewhat higher than in lean diabetics, with the means Chao1 of 2785 (SD 436) and 1945 (SD 399), respectively. The same tendency was observed in the control group (Fig. 1, subjects C4, C6, C7 with BMI >31).

Figure 1. Rarefaction curves.

Rarefaction analysis of V4 pyrosequencing tags of the 16S rRNA gene in fecal microbiota from adults with diabetes type 2 (D1–D10) and non-diabetic controls (C1–C10). Sample codes are the same as in Table 1. Rarefaction curves were constructed at 3% distance using RDP release 10 (Pyrosequencing pipelines).

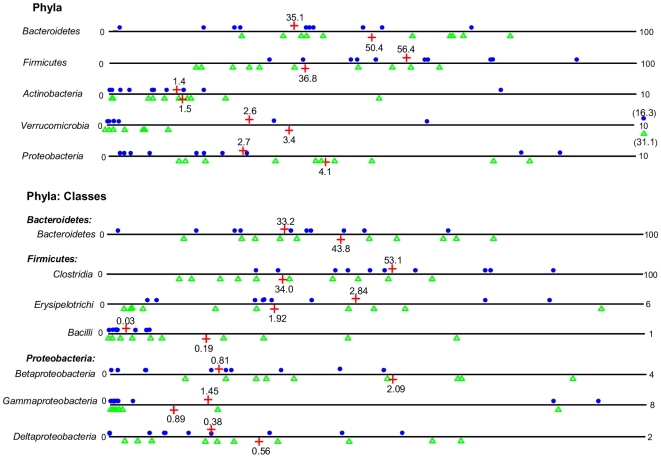

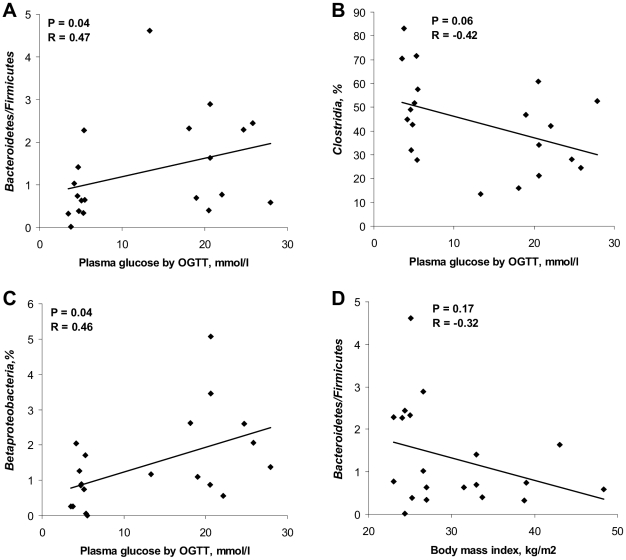

Sequences were distributed among 5 bacterial phyla including Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, together harboring on average up to 90% of sequences, as well as phyla Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria and Verrumicrobia, each accounting for 1–4% of the sequences (Figure 2). The proportion of Firmicutes was significantly higher (P = 0.03) in the controls (mean 56.4%) compared to the diabetic group (mean 36.8%). Accordingly, phylum Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria were somewhat but not significantly enriched in the diabetic group. Furthermore, ratios of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes correlated positively and significantly with the values of plasma glucose determined by OGTT (R = 0.47, P = 0.04) and negatively, though not significantly, with BMI (R = −0.32, P = 0.17; Figure 3A, D). Relative abundances of Actinobacteria and Verrumicrobia were not significantly different between the groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Relative abundances of bacterial phyla and classes.

Relative abundances (%) of bacteria were determined in feces from human adults with type 2 diabetes (green triangles, N = 10) and non-diabetic controls (blue dots, N = 10) by pyrosequencing analysis of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. Mean values are denoted by red crosses and numbers. Values out of scale are shown in brackets.

Figure 3. Correlation between OGTT or BMI and bacterial estimates by pyrosequencing.

Correlation between OGTT plasma glucose and (A) ratios of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes, (B) relative abundance of Clostridia, (C) relative abundance of Betaproteobacteria. (D) Correlation between body mass indices and ratios of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes. The Spearman Rank probability (P) and correlation (R) are shown in the graphs. Bacterial abundances were determined by pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene in fecal bacterial DNA from human adults with type 2 diabetes (N = 10) and non-diabetic controls (N = 10).

Phylum Bacteroidetes was primarily presented by class Bacteroidetes that was on average slightly increased in diabetics (44%) compared to controls (33%; Figure 2). Most of the sequences from Firmicutes belonged to the class Clostridia, varying from 14 to 72% between the subjects. Other classes included Erysipelotrichi and Bacilli, accounting for less than 6% and 1% of the sequences, respectively. The proportion of Clostridia in diabetics was significantly lower than in controls (P = 0.03; means of 53% versus 34%, respectively) and showed a tendency to decrease with higher levels of plasma glucose (R = −0.42, P = 0.06; Figure 3B). The relative abundance of class Bacilli was increased in diabetics at close to significant levels (mean 0.19% versus 0.03% in controls, P = 0.06; Figure 2). Similarly, class Betaproteobacteria, belonging to Proteobacteria, was highly enriched in subjects with diabetes (mean 2.09% versus 0.81% in controls; P = 0.02) and positively correlated (R = 0.46, P = 0.04) with plasma glucose (Fig. 3C). The relative abundances of bacterial genera (see SI Figure S1) were not significantly different between the groups. However, the proportion of genus Roseburia negatively correlated with plasma glucose at levels close to significance (R = −0.52, P = 0.06; data not shown), whereas the opposite trend was observed for the genus Prevotella (R = 0.32, P = 0.15; data not shown).

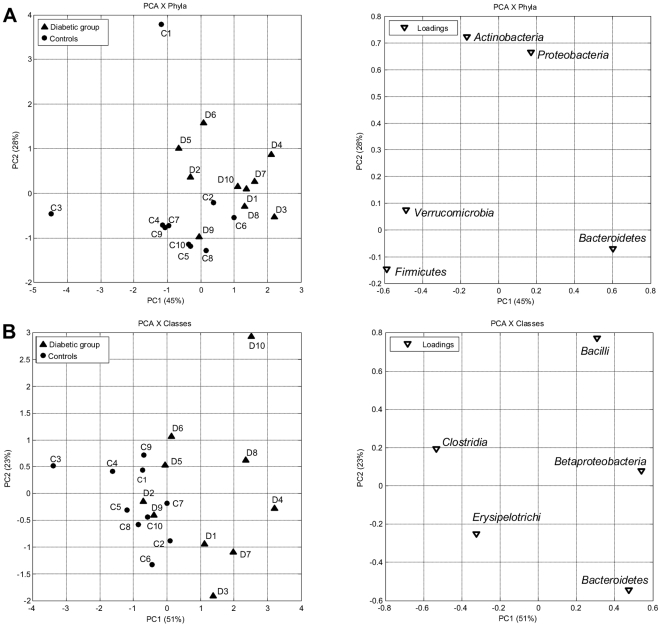

As seen from principal component analysis (PCA), a separation between the diabetic group and the control group at the level of bacterial phyla could be best observed from PC1 and PC2 (Figure 4A; 45% and 28% of explained variance, respectively). It was attributed to Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria in the second direction (PC2) in combination with Bacteroides versus Firmicutes and Verrumicrobia in the first direction (PC1). At the level of bacterial classes the variation was predominantly linked to a higher positive score for Betaproteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Bacilli in the diabetic group, versus Clostridia and Erysipelotrichi in the control group (Figure 4B). The PCA plots of bacterial families generally indicated low levels of systematic variation where only 20–30 percent of the variation was explained by successive PCs, and no distinct clustering was observed (see SI Figure S2A). No association of the diabetic group with particular bacterial genera was apparent. Nevertheless, some of the diabetic persons (see SI Figure S2B, subjects D1, D3, D4, D6, D8, D10) could be discriminated from most of the controls by genus Prevotella versus the combination of genera Lachnospiraceae IS, Roseburia and Subdoligranulum (PC1 50%). PCA of multiple genera showed no clear grouping of the subjects with diabetes probably due to the high individual differences masking the systematic variation (data not shown).

Figure 4. PCA plots of bacterial phyla and classes.

PCA plots showing the grouping of human adults with type 2 diabetes (▴, D1–D10) and non-diabetic controls (•, C1–C10) according to the abundances of bacterial phyla (A) and classes (B) in the fecal bacterial DNA as determined by pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene.

Quantification of the Intestinal Microbiota by qPCR

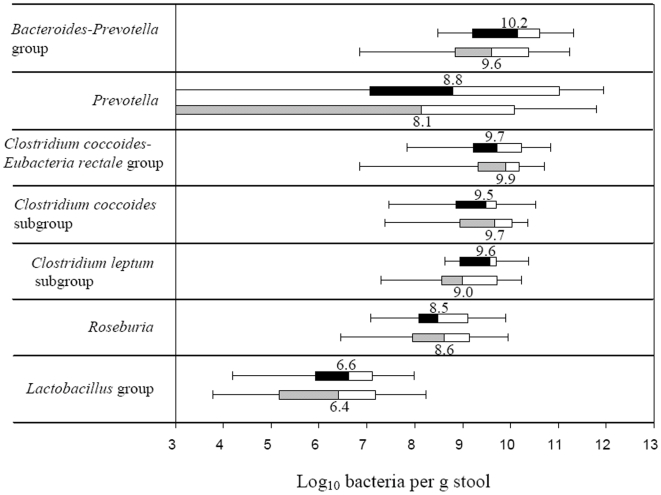

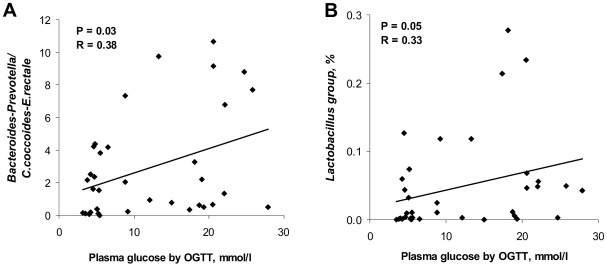

The total bacterial counts were similar in the diabetic and the control group having a median values of 10.6 (quartile ranges (QR) 10.1–11.3) and 10.5 (QR 10.0–11.3) log10 bacteria per g stool, respectively. The estimates of bacterial groups and genera by qPCR are presented in Figure 5. In diabetic group the median counts of Bacteroides-Prevotella group (10.2, QR 9.2–10.6), genus Prevotella (8.8, QR 7.6–11.5) and C. leptum subgroup (9.6, QR 9.0–9.7) were slightly but not significantly increased compared to the controls by approximately 0.7 log10 bacteria. Genus Prevotella was assessed in 25 (14 diabetic subjects and 11 controls) out of 36 samples analysed, whilst for the remaining samples it was below the detection limit of the applied qPCR assay. The difference in median counts of C. coccoides-E. rectale, C. coccoides and Lactobacillus groups, and genus Roseburia between the diabetic persons and controls was less than 0.2 log10 bacteria per g stool. The estimates of Prevotella and Bacteroides-Prevotella group were in some qPCR assays higher that the counts of total bacteria. The explanation might be that the primers, used for quantification of total bacteria, were not universal enough to amplify all bacterial populations, or alternatively that the group-specific primers amplified other targets as well. To overcome this limitation and to assess the differences between the groups of subjects we used ratios of bacterial counts. The ratios of Bacteroides-Prevotella to C. coccoides-E. rectale group correlated significantly and positively (R = 0.38; P = 0.03) with plasma glucose (Figure 6A) but not with BMI (R = 0.06, P = 0.71). Likewise, a positive correlation with plasma glucose was found for the ratios of Bacteroides-Prevotella to C. coccoides subgroup (R = 0.46, P<0.01; data nor shown) and for the proportion of the Lactobacillus group (R = 0.33, P = 0.05; Figure 6B). Higher ratios were in general related to a reduction in the C. coccoides-E. rectale and C. coccoides groups.

Figure 5. Box-and-whisker plots of bacterial groups quantified by qPCR.

Bacterial groups quantified by SYBR Green qPCR and expressed as Log10 bacteria per g stool in human adults with type 2 diabetes (black and white boxes; N = 18) and non-diabetic controls (grey and white boxes; N = 18). The median counts are presented by numbers. Boxes show the upper (75%) and the lower (25%) percentiles of the data. Whiskers indicate the highest and the smallest values.

Figure 6. Correlation between OGTT and bacterial estimates by qPCR.

Correlation between OGTT plasma glucose and (A) ratios of the Bacteroides-Prevotella group to C.coccoides-E.rectale group, (B) relative abundance of the Lactobacillus group determined by SYBR Green qPCR assay in feces from human adults with type 2 diabetes (N = 18) and non-diabetic controls (N = 18). The Spearman Rank probability (P) and correlation (R) are shown in the graphs.

Discussion

In this study we hypothesized that intestinal microbiota in humans with type 2 diabetes is different from non-diabetic persons. The hypothesis was tested on adults with a broad range of ages and BMIs, using pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene and qPCR. To our knowledge no related studies on humans with diabetes type 2 have been published so far.

We demonstrated in this research that type 2 diabetes is associated with compositional changes in the intestinal microbiota mostly apparent at phylum and class levels. The relative abundance of Firmicutes was significantly lower, while the proportion of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria was somewhat higher in diabetic persons compared to their non-diabetic counterparts. Accordingly, the ratios of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes significantly and positively correlated with reduced glucose tolerance. Assuming that diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance are linked to obesity, our results are in agreement with the recent evidence obtained for overweight persons by Schwiertz and colleagues [14], though contradict with other studies [11]. Furthermore, based on the assumption above, a positive correlation between ratios of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes and BMI could be expected. However, the reverse tendency was observed (Figure 3D), indicating that overweight and diabetes are associated with different groups of the intestinal microbiota.

Bacterial groups that distinguished the diabetic from the non-diabetic microbiome included Bacteroides-Prevotella group versus class Clostridia and C. coccoides-E.rectale group, which ratios were significantly higher in diabetic persons. These results are supported by previous studies showing reduction in Bacteroides-Prevotella spp. related to a strong decrease of metabolic endotoxemia and inflammation in type 2 diabetes mice [6]. Accordingly, a significant reduction in Clostridium ssp, C. coccoides and an increase in the Bacteroides-Prevotella group along with body weight loss have been observed in human studies [16], [17]. The significantly higher levels of Bacilli and the Lactobacillus group in diabetic subjects compared to controls in the present study, have recently been reported in relation to type 2 diabetes in mice models [6] and to obesity in human adults [17], [18]. Genus Lactobacillus represents a heterogeneous group with well documented immunomodulating properties [19] and might potentially contribute to chronic inflammation in diabetic subjects.

The tendency of increased Chao1 diversity concurrently with BMI observed in this study, might be related to the negative correlation between BMI and Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratios (Figure 3D) as Firmicutes is a highly diverse division [12]. This observation is, however, in disagreement with recently published data on the obese twin pairs showing reduced bacterial diversity in obese individuals [11]. The reduced individual variation in diversity of the fecal microbiota observed in the diabetic group compared to the controls probably reflected the differences in diet, lifestyle or other factors [20] which are not possible to specify in the present study.

In an obesity study, using mice models, Cani and coworkers [21] proposed a hypothesis connecting metabolic diseases with the presence of Gram-negative bacteria in the gut, also offering a likely explanation of the differences between the diabetic and non-diabetic microbiomes in this study. The intestinal microbiota across the subjects with type 2 diabetes was relatively enriched with Gram-negative bacteria, belonging to the phyla Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria. The main compounds of outer membranes in gram-negative bacteria are lipopolysaccharides (LPS), known as potent stimulators of inflammation, which can exhibit endotoxaemia [22]. Consequently, LPS will continue to be produced within the gut, which might trigger an inflammatory response and play a role in the development of diabetes.

In conclusion, our data suggest that the levels of glucose tolerance or severity of diabetes should be considered while linking microbiota with obesity and other metabolic diseases in humans. It is especially important for developing the strategies to modify the gut microbiota in order to control metabolic diseases, since obesity and diabetes might be associated with different bacterial populations.

Methods

Subjects and Sample Collection

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg Municipalities (KF 01-320695) and performed according to the declaration of Helsinki. Both written and verbal consent was obtained from the subjects of the study. The study included 36 males, diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (N = 18) or as being non-diabetic (N = 18) by their general practitioner confirmed by OGTT. The OGTT included the measurements of plasma glucose (mmol/l) at baseline and two hours after administration of 75 g glucose diluted in 500 ml of water. The BMIs were calculated from the formula: weight (kg)/height (m)2. Subjects' ages, BMIs (kg/m2) and 2-hour plasma glucose concentrations are presented in Table 1. Fecal samples were kept at 5°C immediately after defecation, brought to the laboratory within 24 hours and stored at −80°C before analysis.

Extraction of Bacterial DNA from Fecal Samples

Total bacterial DNA was extracted from the fecal samples using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini kit (QIAGEN, GmbH, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol for pathogen detection with slight modifications [23]. DNA concentration and quality in the extracts was determined by agarose gel electrophoresis (1% wt/vol agarose in Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer) and with a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer Thermo Scientific (Saveen Werner ApS, Denmark).

Pyrosequencing

Tag-encoded amplicon pyrosequencing of fecal DNA was conducted for 10 persons with type 2 diabetes and 10 controls, matching in BMI and age. A selection criterion for diabetic persons was high severity of diabetes as evaluated by OGTT plasma glucose (Table 1). The primers used for pyrosequencing were a modified 530F-mod (GCCAGCMGCNGCGGTA; [24]) and 1061R (CRRCACGAGCTGACGAC; [25]) amplifying a 562 bp DNA fragment flanking the V4, V5 and V6 regions of the 16S rRNA gene ([26]; see SI Table S1). Modification of the primer 530F included two bases (TA) added to 3′-end in order to increase primer specificity. The sequence coverage of the forward and reverse primers was tested using the Probe Match feature at the Ribosomal Database Project release 10 (RDP 10; http://rdp.cme.msu.edu; [27]). The DNA concentration was measured with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and adjusted to 5 ng/µl for all samples. PCR amplification (in a volume of 40 µl) was performed using 1x Phusion HF buffer, 2.5 mM magnesium chloride, 0.2 mM dNTP mixture, 0.8 U Phusion Hot Start DNA Polymerase (Finnzymes Oy, Espoo, Finland), 0.5 µM of each primer (TAG Copenhagen A/S, Denmark) and 1 µl diluted DNA sample. PCR was performed using the following cycle conditions: an initial denaturation at 98°C for 30 s, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 5 s, annealing at 53°C for 20 s, elongation at 72°C for 20 s, and then a final elongation step at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were run on an agarose gel and purified using the QIAEX II Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN). Second round of PCR was performed as described above, except that the primers with adapters and tags were used, the number of cycles was reduced to 10 and the annealing temperature was increased to 56°C. Addition of adapter and tags specific to each sample was done using the custom primers with adapter A and 10 tags (see SI Table S1) required for pyrosequencing [24]. The concentration of the tagged PCR product was determined by qPCR. The standard DNA used in qPCR was prepared from Pseudomonas putida and quantified against a standard concentration of 200 base ssDNA oligo (TAG Copenhagen A/S, Denmark). The qPCR was performed in a 25 µl volume, using 1x Brilliant buffer (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, Texas, USA), 0.5 µM of each primer FLX (forward: GCCTCCCTCGCGCCATCAG and reverse: GCCTTGCCAGCCCGCTCAG) and 1 µl of diluted PCR products with tags and adapters. Amplification was conducted using a Mx-3000 thermocycler (Stratagene) at the following conditions: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 60 s. Amplicons were then mixed in approximately equal concentration (5×107 copies per µl) to ensure equal representation of each sample. A two-region 454 sequencing run was performed on a GS FLX Standard PicoTiterPlate (70X75) by using a GS FLX pyrosequencing system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche).

Analysis of sequencing data was conducted using Pyrosequencing Pipeline tools at RDP 10 (http://pyro.cme.msu.edu/index.jsp). The RDP Classifier was used to assign 16S rRNA gene sequences to taxonomical hierarchy with a confidence threshold of 80%. Bacterial diversity was determined by sampling-based analysis of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and showed by rarefaction curves. Comparison of bacterial richness across the samples was performed by Chao1 estimate at the distance of 3%, usually applied to characterize richness at species level [12], [28]. As the Chao1 estimates are dependent on the size of the sequence libraries, the sample sizes from the different subject we equalized by random subtraction.

Real-Time qPCR

Bacterial groups in fecal samples from 18 subjects with type 2 diabetes and 18 controls were quantified by qPCR using the 7500 Fast Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) and the primers shown in Table 3 (TAG Copenhagen A/S, Denmark). Genus-specific primers for amplification of Prevotella and Roseburia were designed using 16S rRNA gene sequences from the RDP 10. Sequences were aligned by the ClustalW software provided by the European Bioinformatics Institute (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html). The target-specific sites were assessed by “Oligo” Primer Analysis Software version 6.71 (Molecular Biology Insights, Inc., USA). Specificity of the primers was evaluated in silico using the nucleotide BLAST, blastn algorithm (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Prevotella-specific primers were targeting Prevotella falsenii, P. copri, P. nigrescens, P. intermedia, P. pallens, P. maculosa and P. oris. Primers targeting Roseburia were specific for species Roseburia faecis, R. hominis, R. intestnalis and R. cecicola.

Table 3. Primers used in the study for real-time qPCR and size of PCR products.

| Target organism | Primer a | Sequence (5′to 3′) | PCR productbp | Reference |

| Clostridium coccoides-Eubacteria rectale group | ClEubF | CGGTACCTGACTAAGAAGC | 429 | [31] |

| ClEubR | AGTTTYATTCTTGCGAACG | |||

| Clostridium leptum subgroup | CleptF | GCACAAGCAGTGGAGT | 239 | [32] |

| CleptR | CTTCCTCCGTTTTGTCAA | |||

| Clostridium coccoides subgroup | CcocF | AAATGACGGTACCTGACTAA | 440 | |

| CcocR | CTTTGAGTTTCATTCTTGCGAA | |||

| Roseburia b | RosF | TACTGCATTGGAAACTGTCG | 230 | This study |

| RosR | CGGCACCGAAGAGCAAT | |||

| Bacteroides-Prevotella group | BacF | GAAGGTCCCCCACATTG | 410 | [33] |

| BacR | CAATCGGAGTTCTTCGTG | |||

| Prevotella c | PrevF | CACCAAGGCGACGATCA | 283 | This study |

| PrevR | GGATAACGCCYGGACCT | |||

| Lactobacillus group | LacF | AGCAGTAGGGAATCTTCCA | 341 | [34] |

| LacR | CACCGCTACACATGGAG | |||

| Bifidobacterium | BifF | GCGTGCTTAACACATGCAAGTC | 126 | [35] |

| BifR | CACCCGTTTCCAGGAGCTATT | |||

| All bacteria | UnivF | TCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGT | 466 | [36] |

| UnivR | GACTACCAGGGTATCTAATCCTGTT |

Primers F (forward) and R (reverse) targeting the 16S rRNA gene.

Primers targeting Roseburia species: R. faecis, R. hominis, R. intestnalis and R. cecicola.

Primers targeting Prevotella species: P. falsenii, P. copri, P. nigrescens, P. intermedia, P. pallens, P. maculosa and P. oris.

The qPCR reaction mixture (20 µl) was composed of 0.3 µM of each universal primer or 0.5 µM of each specific primer, 1x Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Calif., USA), and 4 µl fecal DNA added in 10-fold serial dilutions starting from 100-fold dilution to diminish the effect of inhibitors. The amplification program consisted of one cycle of 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 1 min. Standard curves were constructed for each experiment using 10-fold serial dilutions of bacterial genomic DNA of known concentration. Genomic DNA from L. acidophilus NCFM (ATCC 700396) and from Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis (B. lactis) Bi-07 (ATCC SD5220) was extracted with the use of GenElute Bacterial Genomic DNA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) according to the manufacture's instructions. DNA from Roseburia intestinalis DSM14610, Prevotella copri DSM18205, Clostridium leptum DSM 753, Clostridium coccoides DSM935, Clostridium nexile DSM1787 and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron DSM 2079 was purchased from DSM collection (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Germany). Standard curves were created according to Applied Biosystems tutorials (http://www3.appliedbiosystems.com) and normalized to the copy number of the 16S rRNA gene for each species. For the species which copy number of 16S rRNA operon was not published, it was calculated by averaging the operon numbers of the closest bacterial taxa from the ribosomal RNA database rrnDB (http://ribosome.mmg.msu.edu/rrndb/index.php; [29]). Cell numbers of bacteria in fecal samples were calculated from the threshold cycle values (Ct) and expressed as quantity of bacteria per gram feces [30].

Statistical Analysis

PCA plots were generated by Matlab 2008b using in-house algorithms (http://www.mathworks.com). Differences in bacterial populations between the diabetic and control groups were assessed using the two-sided Wilcoxon Rank Sum test (Statistics Online Computational Resource (SOCR), http://www.socr.ucla.edu/SOCR.html). Correlation between the variables was computed by Spearman Rank correlation provided by Free Statistics Software (version 1.1.23-r4, Office for Research Development and Education, http://www.wessa.net/). The qPCR results were graphically presented by Box and Whisker charts (Microsoft Office Excel 2007) and expressed as medians with quartile ranges (QR).

Supporting Information

Relative abundances of bacterial genera. Relative abundances (%) of bacterial genera in feces from human adults with type 2 diabetes (green triangles, N = 10) and non-diabetic controls (blue dots, N = 10) determined by pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. Mean values are denoted by red crosses and numbers. Values out of scale are shown in brackets.

(0.28 MB TIF)

PCA plots of bacterial families and genera. PCA plots showing the grouping of human adults with type 2 diabetes (triangles, D1-D10) and non-diabetic controls (dots, C1-C10) according to the abundances of bacterial families (A) and genera (B) in fecal bacterial DNA as determined by pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16s rRNA gene.

(0.32 MB TIF)

Primers, adaptor and sample-specific barcodes used in the study for tag-encoded amplicon pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene.

(0.03 MB DOC)

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This study was supported by the Danish Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, The Danish Food Industry Agency (J.nr.3304-FSE-06-0501-1; www.dffe.dk). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cani PD, Possemiers S, Van de Wiele T, Guiot Y, Everard A, et al. Changes in gut microbiota control inflammation in obese mice through a mechanism involving GLP-2-driven improvement of gut permeability. Gut. 2009;58:1091–1103. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.165886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1111–1119. doi: 10.1172/JCI25102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tilg H, Moschen AR, Kaser A. Obesity and the microbiota. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1476–1483. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsukumo DM, Carvalho BM, Carvalho MA, Saad MJA. Translational research into gut microbiota: new horizons in obesity treatment. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia e Metabologia. 2009;53:139–144. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302009000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dandona P, Aljada A, Bandyopadhyay A. Inflammation: the link between insulin resistance, obesity and diabetes. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cani PD, Rottier O, Goiot Y, Neyrinck A, Geurts L, et al. Changes in gut microbiota control intestinal permeability-induced inflammation in obese and diabetic mice through unexpected dependent mechanisms. Diabetologia. 2008;51:S34–S35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brugman S, Klatter FA, Visser JTJ, Wildeboer-Veloo ACM, et al. Antibiotic treatment partially protects against type 1 diabetes in the bio-breeding diabetes-prone rat. Is the gut flora involved in the development of type 1 diabetes? Diabetologia. 2006;49:2105–2108. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Membrez M, Blancher F, Jaquet M, Bibiloni R, Cani PD, et al. Gut microbiota modulation with norfloxacin and ampicillin enhances glucose tolerance in mice. Faseb J. 2008;22:2416–2426. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-102723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Backhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15718–15723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, et al. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11070–11075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–4U7. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang HS, DiBaise JK, Zuccolo A, Kudrna D, Braidotti M, et al. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2365–2370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1131. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwiertz A, Taras D, Schafer K, Beijer S, Bos NA, et al. Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. 2009. Obesity. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Duncan SH, Lobley GE, Holtrop G, Ince J, Johnstone AM, et al. Human colonic microbiota associated with diet, obesity and weight loss. Int J Obes. 2008;32:1720–1724. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nadal I, Santacruz A, Marcos A, Warnberg J, Garagorri M, et al. Shifts in clostridia, bacteroides and immunoglobulin-coating fecal bacteria associated with weight loss in obese adolescents. Int J Obes. 2009;33:758–767. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santacruz A, Marcos A, Warnberg J, Marti A, Martin-Matillas M, et al. Interplay between weight loss and gut microbiota composition in overweight adolescents. Obesity. 2009;17:1906–1915. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armougom F, Henry M, Vialettes B, Raccah D, Raoult D. Monitoring bacterial community of human gut microbiota reveals an increase in Lactobacillus in obese patients and methanogens in anorexic patients. Plos One. 2009;4:e7125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeuthen LH, Christensen HR, Frokiaer H. Lactic acid bacteria inducing a weak interleukin-12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha response in human dendritic cells inhibit strongly stimulating lactic acid bacteria but act synergistically with gram-negative bacteria. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:365–375. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.3.365-375.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dicksved J, Floistrup H, Bergstrom A, Rosenquist M, Pershagen G, et al. Molecular fingerprinting of the fecal microbiota of children raised according to different lifestyles. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:2284–2289. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02223-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Knauf C, Burcelin RG, et al. Selective increases of bifidobacteria in gut microflora improve high-fat-diet-induced diabetes in mice through a mechanism associated with endotoxaemia. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2374–2383. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0791-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allcock GH, Allegra M, Flower RJ, Perretti M. Neutrophil accumulation induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide: effects of dexamethasone and annexin 1. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;123:62–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01370.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen DS, Moller PL, Rosenfeldt V, Paerregaard A, Michaelsen KF, et al. Case study of the distribution of mucosa-associated Bifidobacterium species, Lactobacillus species, and other lactic acid bacteria in the human colon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:7545–7548. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7545-7548.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dowd SE, Sun Y, Secor PR, Rhoads DD, Wolcott BM, et al. Survey of bacterial diversity in chronic wounds using Pyrosequencing, DGGE, and full ribosome shotgun sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersson AF, Lindberg M, Jakobsson H, Backhed F, Nyren P, et al. Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. Plos One. 2008;3:e2836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neefs JM, Van de PY, De RP, Chapelle S, De WR. Compilation of small ribosomal subunit RNA structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3025–3049. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.13.3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cole JR, Wang Q, Cardenas E, Fish J, Chai B, et al. The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D141–D145. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schloss PD, Handelsman J. Status of the microbial census. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:686–691. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.4.686-691.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee ZMP, Bussema C, Schmidt TM. rrnDB: documenting the number of rRNA and tRNA genes in bacteria and archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D489–D493. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouwehand AC, Tiihonen K, Saarinen M, Putaala H, Rautonen N. Influence of a combination of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and lactitol on healthy elderly: intestinal and immune parameters. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:367–375. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508003097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartosch S, Fite A, Macfarlane GT, Mcmurdo MET. Characterization of bacterial communities in feces from healthy elderly volunteers and hospitalized elderly patients by using real-time PCR and effects of antibiotic treatment on the fecal microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:3575–3581. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3575-3581.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimoto J, Takada T, Tanaka R. Use of 16S rRNA gene-targeted group-specific primers for real-time PCR analysis of predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:7220–7228. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7220-7228.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadkarni MA, Martin FE, Jacques NA, Hunter N. Determination of bacterial load by real-time PCR using a broad-range (universal) probe and primers set. Microbiology-Sgm. 2002;148:257–266. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-1-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Penders J, Vink C, Driessen C, London N, Thijs C, et al. Quantification of Bifidobacterium spp., Escherichia coli and Clostridium difficile in faecal samples of breast-fed and formula-fed infants by real-time PCR. Fems Microbiol Lett. 2005;243:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rinttila T, Kassinen A, Malinen E, Krogius L, Palva A. Development of an extensive set of 16S rDNA-targeted primers for quantification of pathogenic and indigenous bacteria in faecal samples by real-time PCR. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:1166–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walter J, Hertel C, Tannock GW, Lis CM, Munro K, et al. Detection of Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Leuconostoc, and Weissella species in human feces by using group-specific PCR primers and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:2578–2585. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2578-2585.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Relative abundances of bacterial genera. Relative abundances (%) of bacterial genera in feces from human adults with type 2 diabetes (green triangles, N = 10) and non-diabetic controls (blue dots, N = 10) determined by pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. Mean values are denoted by red crosses and numbers. Values out of scale are shown in brackets.

(0.28 MB TIF)

PCA plots of bacterial families and genera. PCA plots showing the grouping of human adults with type 2 diabetes (triangles, D1-D10) and non-diabetic controls (dots, C1-C10) according to the abundances of bacterial families (A) and genera (B) in fecal bacterial DNA as determined by pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16s rRNA gene.

(0.32 MB TIF)

Primers, adaptor and sample-specific barcodes used in the study for tag-encoded amplicon pyrosequencing of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene.

(0.03 MB DOC)