Abstract

We report two cases of band keratopathy who were treated with thick amniotic membrane that contained a basement membrane structure as a graft, after ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid chelation with trephination and blunt superficial lamellar keratectomy in the anterior stroma. In each case, basement membrane was destroyed and calcium plaque invaded into anterior stroma beneath Bowman's membrane. The calcified lesions were removed surgically, resulting in a smooth ocular surface, and the fine structures of band keratopathy were confirmed by pathologic findings. After that, amniotic membrane transplantation was performed to replace the excised epithelium and stroma. Wound healing was completed within 10 days. Stable ocular surface was restored without pain or inflammation. During the mean follow-up period of 13.5 months, no recurrence of band keratopathy was observed. This combined treatment is a safe and effective method for the removal of deep-situated calcium plaque and allowing the recovery of a stable ocular surface.

Keywords: Amnion, Band Keratopathy, Covneal Diseases, Edetic Acid

INTRODUCTION

Band keratopathy, first described by Bowman in 1849 (1) may occur secondary to chronic ocular inflammatory conditions such as anterior uveitis and dry eye syndrome. Long-term use of eye drops containing mercury, and some inherited conditions or systemic diseases associated with hypercalcemia such as chronic renal failure and bone destruction disorders also are common causes of corneal calcified lesions (2-4). Deposited calcium band is observed horizontally on the cornea and there is lesion free, lucid space between the limbus and lesion. It may cause blindness as the result of opacification of the cornea, block the visual axis and cause pain due to corneal epithelial erosions (2-4). Impacted calcium is mainly found at the level of the corneal epithelium, but in some cases, the basement membrane was destroyed and calcium deposition invaded the anterior stroma beneath Bowman's membrane. Based on the extent of basement membrane destruction and stromal invasion, band keratopathy can be divided into two subtypes: a superficial type that includes epithelial layer involvement, and a deep type where calcium is situated under Bowman's layer, and even involves the stromal layer. Conventional treatments have focused on only the removal of deposited calcium by superficial keratectomy, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) treatment, or excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) (5-10). The aim of these treatments was to remove the calcium impaction in the epithelial layer. These conventional treatments failed to completely remove the deeply situated calcium plaque. So, new treatment methods must be developed to completely remove deep-impacted calcium without any sequela, and allow no recurrence.

Amniotic membrane has many unique characteristics and it facilitates wound healing, stabilizes the ocular surface and enhances corneal re-epithelialization. Amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT) was recently reintroduced into ophthalmology (11), and has been successfully used for ocular surface reconstruction, notably facilitating epithelialization, as well as suppression of ocular surface inflammation, neovascularization, and scarring in the stroma (12-22). In addition, during the wound healing process, amniotic membrane acts as a temporary dressing to protect the corneal surface, absorbs inflammatory cytokines, and reduces pain during corneal epithelialization.

We report two cases of deep-type band keratopathy treated with AMT following EDTA chelation with trephination and blunt superficial lamellar keratectomy in the anterior stromal layer.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

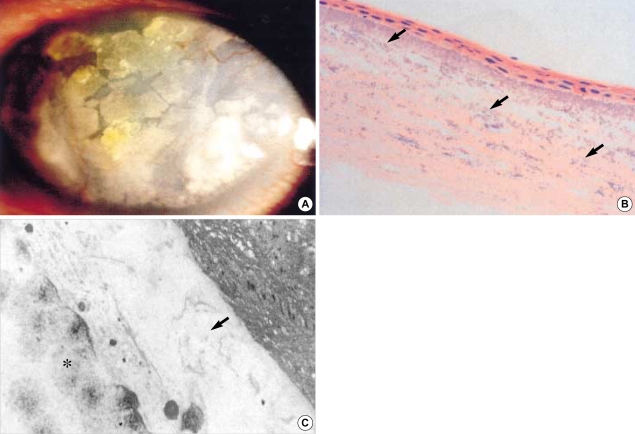

A 64-yr-old female patient with calcified corneal lesions on the cornea was referred to Chung-Ang University Hospital. She had a history of extracapsular cataract extraction and intraocular lens (IOL) implantation in the left eye 20 yr ago. Recently, the patient's visual condition was aggravated in both eyes, after the first ocular surgery. Corneal opacity had continued to progress and foreign body sensation and blurring had developed in both eyes over the past 10 yr. Slit lamp examination revealed corneal opacity, and calcium plaque (Fig. 1A), but limbal deficiency was not observed. She had light perception vision and intraocular pressures, that were checked by Pro-view® (BAUSCH & LOMB, Tampa, FL, U.S.A.) were in normal ranges in both eyes. Serum levels of Ca++, BUN, and creatinine were all normal (8.7, 13, and 0.9 mg/dL, respectively). The diagnosis of band keratopathy, pseudophakia and Vogt-Koyanaki-Harada syndrome was made.

Fig. 1.

(A) Calcium is deposited on the cornea (visual acuity: light perception). (B) Multiple calcium impactions and calcium deposit are observed in the stromal layer (H&E, ×200). (C) Deposited calcium is seen in stromal layer (asterisk). Destroyed basement membrane is observed in the degenerated stromal space (arrow) (×4,100).

The patient underwent surgery to remove the calcified band keratopathy. First, trephination to the anterior stromal layer was performed by using 6 mm size punch (Stortz, Denver, CO, U.S.A.) in both eyes. Then EDTA (0.125 M) was applied for 2.5 min until it adequately infiltrated the space between the destroyed stroma and dissolved the calcium impaction. Then, the superficial keratectomy with a round blade and #15-0 Bard-Parker blade was done and the transplantation of the basement membrane-containing thick amniotic membrane (preserved in DMEM and glycerol 2:1 mixed media, -70℃) was performed epithelial side up. Amniotic membrane was sutured into place using interrupted and continued bite secondary with #10-nylon for replacement of the defective stroma. Subsequently, the temporary amniotic membrane patch (TAMP) with epithelial side down was done to protect the ocular surface.

Postoperatively, the patient was treated with 20% autologous serum and ofloxacin (Tarivid®, Santen, Osaka, Japan) 4 times a day from the second day after the operation. On the 5th post-operative day, neomycin/polymixin-B/dexamethasone mixed eye drops (Maxitrol®, Alcon, Ft. Worth, TX, U.S.A.) were administered for 3 days and then changed to flouromethorone (Ocumethrone®, Shin-Il, Seoul, Korea) for 2 weeks. After removal of TAMP on the 5th day, the epithelium was healed to a pinpoint-like defect in the right eye and one-third part of a defect in the left eye upon slit lamp examination. The patient did not complain of any ocular pain, but only did foreign body sensation. Corneal epithelialization was confirmed on the 2nd postoperation day, and when completed, the ocular surface was stable in the both eyes on the 10th postoperation day. Pathologic findings of biopsy specimen revealed impacted calcium in the epithelium and anterior stroma. Destroyed basement membrane and superficial stromal degeneration were also observed in the electron micrographic figure (Fig. 1C). After discharge, during outpatient department follow up, the patient did not complain of ocular pain but only the condition of cornea remained stable. On the last follow up after 17 months, visual acuity had improved to finger count at 70 cm, and intraocular pressure was 10/12 torr in both eyes. Macular degenerations and hypertensive retinopathy (Keith-Wagener, grade 2) were observed in the both eyes. Because of these lesions, visual outcome was poor in spite of the removal of calcified lesions with stabilized corneal surface.

Case 2

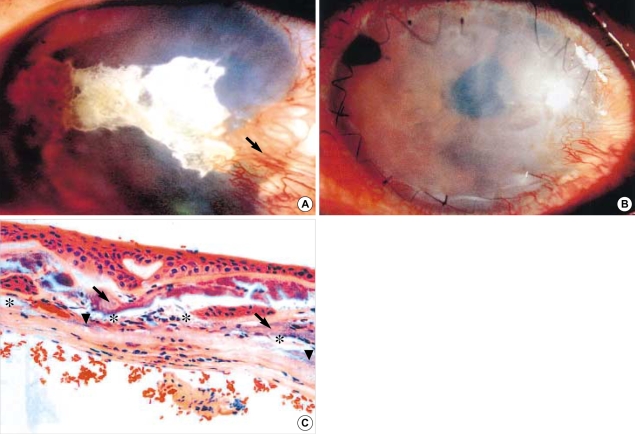

A 60-yr-old male patient visited our clinic because of ocular pain and severe foreign body sensation in the right eye. He had undergone intra-capsular cataract extraction and anterior chamber lens (ACL) implantation in the right eye under diagnosis of presenile cataract 19 yr ago. Severe pain and blurring had developed since the 8 yr after the operation; and symptoms had been increasingly exacerbated thereafter. Visual acuity was perceptive to hand motion in the involved right eye and 0.9 in the normal left eye. Slit lamp examination revealed corneal opacity and horizontal calcified corneal lesions in the palpebral fissure. Partial limbal deficiency and pseudopterygium with neovascularization were also seen at the 4 o'clock position (Fig. 2A). Because of calcified corneal lesions, it was impossible to examine full details, but a dislocated anterior chamber lens (ALC) and iridotomy hole on the peripheral iris in the anterior chamber. Intraocular pressures (IOP) were measured at the level of 33 torr in the right side and 20 torr in the left eye by Pro-view®. Serum levels of Ca++, BUN, and creatinine were in normal ranges (8.5, 14 and 1.1 mg/dL, respectively) and no systemic disorders were found. We diagnosed him as ACL dislocation, secondary glaucoma, and possibly anterior uveitis and band keratopathy. Patient was given β-blocker and carbonic anhydrase inhibitor mixed eye drop (Cosopt®, MSD, Whitehouse Station, NJ, U.S.A.) twice a day, acetzolamide 250 mg (Diamox®, Wyeth, Madison, NJ, U.S.A.), twice a day, p.o. for IOP control. After confirming the normalized IOP, the patient underwent trephination with 6 mm size punch into the potent pathologic space beneath Bowman's layer to instill EDTA. After that, EDTA chelation (0.125 M) to dissolve the calcium plaque was performed for 2.5 min until enough had spread into the space. Then, superficial keratectomy with blunt spatula was done without any excision or scraping, because the instilled EDTA had already dissolved the calcium impaction and the space between the destroyed stroma and Bowman's membrane had separated clearly without any scar. After removal of pseudopterygium and ACL, AMT was performed with epithelial side up to replace the removed stromal matrix and enhance wound healing. Then, TAMP with epithelial side down was done under local anesthesia. Amniotic membrane graft was sutured in place interruptedly and continuously with #10-0 nylon after removal of the calcium-impacted epithelium and anterior stroma. IOL re-implantation was not done. Postoperatively, the patient was treated with the same drug regimen as described in case 1. On the 2nd day, corneal reepithelialization had started and was nearly completed after 9 days. When discharged on the 12th day, the visual outcome was noted at finger count of 60 cm and the IOP was 9 torr under aphakic conditions by Pro-view®. Pathologic findings of the cornea showed impacted calcium, broken basement membrane and separated Bowman's membrane due to calcium deposition with degenerative changes (Fig. 2C). The pain and severe inflammation were not revealed until the last follow up at 10 months after the operation. Final visual outcome was recorded as 0.06 in the right eye with aphakic state and the corrected visual acuity was 0.4.

Fig. 2.

(A) Calcified plaque and pseudopterygium is seen (arrow) (visual acuity: perceptive to hand motion). (B) On postoperative 4 months, permanent amniotic membrane graft and clear cornea is seen. (C) Impacted calcium was seen over (arrow) and below (arrow head) the Bowman's membrane. And degenerated and destroyed stroma was observed (asterisk). (H&E, ×200).

DISCUSSION

Calcified band keratopathy is characterized by a grayishwhite opacity of the superficial cornea, usually in the interpalpebral area. By pathologic findings, band keratopathy is divided into two different subtypes according to the calcium-impacted layer. In the superficial type, calcium is scattered only in the epithelium and the basement membrane is preserved intact; in the deep type, however, calcium plaque invades the anterior stroma beyond Bowman's membrane and the basement membrane is destroyed, and a potent space is observed. In the cases in our report, broad and diffuse calcifications as confirmed by pathologic examination, invaded the stromal layer under the basement membrane (Fig. 1B, C, 2C). The treatment of band keratopathy has a purpose of removing the calcified plaque deposition and restoring the smooth corneal surface. In applying conventional techniques, however, several complications appeared, including severe pain, low visual acuity, and recurrence. Because these treatments mainly focused on the removal of superficial calcium deposits in the epithelial layer (5-10), the calcium plaque impacted in the stromal layer was unable to be removed completely. For complete removal of calcium deposits and to prevent recurrence, treatment must be modified according to the subtype. We reported the present cases to demonstrate a new strategy in the management of deep-situated calcium band keratopathy by combining EDTA chelation with trephination and blunt superficial lamellar keratectomy without excision followed by thick amniotic membrane transplantation for the complete removal of impacted calcium in stromaldeposited deep subtype. We trephined the cornea enough to facilitate the infiltration of the EDTA solution, and after that, we removed the calcified plaque by blunt spatula to permit a clear, smooth surface without any scraping (the second case). In the first case, we used a round blade and #15-0 Bard-Parker blade, so stromal scarring could potentially remain. By trephining enough into the stromal layer, EDTA was instilled into the pathologic potent space between the destroyed stroma by calcium plaque, and dissolved them. So, without any scraping, the calcified lesions were separated clearly and the smooth surface was preserved without scarring. This technique could restore an intact corneal surface after wound healing, with minimal refractive error or discomfort to patients.

Amniotic membrane provides a thick basement membrane and avascular stroma that replaces the removed tissue, and has been reported to facilitate corneal and conjunctival epithelialization both in vivo and in vitro (12-19). In our surgical method, calcified lesions were removed completely, but the relatively deep corneal stromal defect could potentially delay wound healing. So, to promote wound healing, we replaced the corneal defect with thick amniotic membrane that contains the basement membrane structure. Anderson et al. (10) reported that patients had a mean epithelial healing time of 15.2 days (7-60 days) and no pain or recurrence after AMT for mean follow up period of 14.6 months. Similarly, we observed complete re-epithelialization of the eye after 9-10 days, with a stable, smooth corneal surface and without inflammation and discomfort. During the mean follow-up period of 13.5 months, no patients reported any recurrence of the ocular surface pain that originally constituted the principal complaint. The lack of inflammation and the return of corneal clarity after surgery may be attributed to the complete removal of calcium without any scarring, and the action of the amniotic membrane that replaced the basement membrane and stromal matrix. Recently, it was reported that an amniotic membrane matrix can suppress transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling and the proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation of normal human corneal and limbal fibroblasts (21). This action helps explain why amniotic membrane transplantation reduces corneal haze after phototherapeutic or photorefractive keratectomy in rabbits (19, 22). We have also used the amniotic membrane in the treatment of other corneal diseases with epithelial defects. Amniotic membrane application showed many promising effects on promoting corneal epithelial healing, maintaining clarity and resulted in a lower recurrence after the removal of pterygium (18).

In conclusion, we found that amniotic membrane transplantation following EDTA chealation with punch trephination and blunt superficial lamellar keratectomy was a simple, safe and effective method to completely remove calcified lesions, and that amniotic membrane transplantation was useful to restore a stable ocular surface in band keratopathy.

References

- 1.Bowman W. Lectures on the parts concerned in the operations on the eye, and on the structure of the retina. 1st ed. Vol 1. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans; 1849. pp. 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smolin G. Corneal dystrophies and degenerations. In: Smolin G, Thoft RA, editors. The Cornea. New York: Bobcock Mary; 1994. pp. 499–534. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starck T, Hersh PS, Kenyon KR. Corneal dysgeneses, dystrophies, and degenerations. In: Albert DM, Jakobiec FA, editors. Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: Power Susan M; 2000. pp. 695–755. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JH, Kim HB. Degeneration of cornea and conjuntiva. In: Kim JH, Kim HB, editors. Cornea. Seoul: Ilchogak; 2000. pp. 245–264. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bokosky JE, Meyer RF, Sugar A. Surgical treatment of calcific band keratopathy. Ophthalmic Surg. 1985;16:645–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park JW, Choi SK. The efficacy of EDTA chelation on band keratopathy. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1997;38:1712–1719. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SH, Lee TS. EDTA Treatment of secondary band keratopathy. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1981;22:413–418. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maloney RK, Thompson V, Ghiselli G, Durrie D, Waring GO, 3rd, O'Connell M. A prospective multicenter trial of excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy for corneal vision loss. The Summit Phototherapeutic Keratectomy Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:149–160. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brart DP, Gartry DS, Lohmann CP, Patmore AL, Kerr Muir MG, Marshall J. Treatment of band keratopathy by excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy: Surgical Techniques and Long Term Follow Up. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:702–708. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.11.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson DF, Prabhaswat P, Alfonso E, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation after the primary surgical management of band keratopathy. Cornea. 2001;20:354–361. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JC, Tseng SC. Transplantation of preserved human amniotic membrane for surface reconstruction in severely damaged rabbit corneas. Cornea. 1995;14:473–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tseng SC, Prabhasawat P, Lee SH. Amniotic membrane transplantation for conjunctival surface reconstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:765–774. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71693-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tseng SC, Prabhasawat P, Barton K, Gray T, Meller D. Amniotic membrane transplantation with or without limbal allografts for corneal surface reconstruction in patients with limbal stem cell deficiency. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:431–441. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pires RT, Tseng SC, Prabhasawat P, Puangsricharern V, Maskin SL, Kim JC, Tan DT. Amniotic membrane transplantation for symptomatic bullous keratopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1291–1297. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.10.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azuara-Blanco A, Pillai CT, Dua HS. Amniotic membrane transplantation for ocular surface reconstruction. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:399–402. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.4.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SH, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation for persistent epithelial sefects with ulceration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:303–312. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dua HS, Azuara-Blanco A. Amniotic membrane transplantation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:748–752. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.6.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prabhasawat P, Barton K, Burkett G, Tseng SC. Comparison of conjunctival autografts, amniotic membrane grafts, and primary closure for pterygium excision. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:974–985. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi YS, Kim JY, Wee WR, Lee JH. Effect of the application of human amniotic membrane on rabbit corneal wound healing after excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy. Cornea. 1998;17:389–395. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199807000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meller D, Pires RT, Tseng SC. Ex vivo preservation and expansion of human limbal epithelial stem cells on amniotic membrane cultures. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:463–471. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.4.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tseng SC, Li DQ, Ma X. Suppression of transforming growth factor-beta isoforms, TGF-β receptor type II, and myofibroblast differentiation in cultured human corneal and limbal fibroblasts by amniotic membrane matrix. J Cell Physiol. 1999;179:325–335. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199906)179:3<325::AID-JCP10>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang MX, Gray TB, Park WC, Prabhasawat P, Culbertson W, Forster R, Hanna K, Tseng SC. Reduction in corneal haze and apoptosis by amniotic membrane matrix in excimer laser photoablation in rabbits. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:310–319. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00467-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]