Abstract

In this study, we report the development of a new dual reporter vector system for the analysis of promoter activity. This system employs green fluorescence emitting protein, EGFP, as a reporter, and uses red fluorescence emitting protein, DsRed, as a transfection control in a single vector. The expression of those two proteins can be readily detected via flow cytometry in a single analysis, with no need for any further manipulation after transfection. As this system allows for the simultaneous detection of both the control and reporter proteins in the same cells, only transfected cells which express the control protein, DsRed, can be subjected to promoter activity analysis, via the gating out of all un-transfected cells. This results in a dramatic increase in the promoter activity detection sensitivity. This novel reporter vector system should prove to be a simple and efficient method for the analysis of promoter activity.

Keywords: Dual reporter vector system, Transcription activity, Promoter assay, FACS

INTRODUCTION

The expression of a gene is controlled by trans-acting transcription factors and by cis-acting elements on the genome, including promoters and enhancers (1). Serially deleted fragments of the putative promoter region of fairly bulky size can be fused with the same reporter gene, in order to compare their transcriptional promotion abilities.

These series of expression vectors must be transfected into cells in which the target promoter can be operated, but the reporter protein itself should not be endogenously expressed. The expression of chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) as a reporter can be detected in a variety of ways, and has been the reporter of choice in reporter vector systems for a long time (2). Luciferase is also a common reporter protein currently in use (3). The notable disadvantage of these systems, however, is that the expressed reporter protein must be assayed via enzymatic reactions using whole cell extracts into which the reporter vector has been transfected. This method is both time- and labor-intensive. As the transfection efficiency can never reach 100%, any extracts from the reporter vector-transfected cells are actually a mixture of transfected and un-transfected cells, the exact ratio of which cannot be calculated. Thus, it is impossible to conduct direct comparisons of the activity between different extracts. In order to circumvent this problem, a control vector which is able to direct the expression of another indicative protein, such as beta-galactosidase, under the control of a fixed promoter, is usually co-transfected. This necessitates an additional round of laborious enzymatic assays for the expression of the control gene (4). Although this control protein is a good compensation indicator for transfection efficiency, the possibility always exists for a disparity between the transfection efficiency of separately prepared plasmid vectors. Some commercial dual reporter vector systems (Dual-Glo™ or Chroma-Glo™ Luciferase assay systems, Promega, Madison, WI) have been developed in an attempt to solve these problems. However, these systems still require extra enzymatic assay steps, and the systems are still vulnerable to the problem of unequal transfection efficiency among samples. Another approach to the solution of these problems is the simultaneous transfection of both reporter and control genes, using different fluorescent proteins for the determination of promoter activities (5,6). However, this method also requires the separate preparation of both the reporter and control plasmids, and the accuracy of this method is inferior to that of a system utilizing a single vector harboring both genes. This is true in practice, as a significant portion of the cells in such a system receive only one of the reporter or control vectors.

We attempted to obviate all of these problems via the development of a single reporter vector system, in which the reporter gene and the control gene are expressed in a single plasmid vector, thus eliminating the possibility of unequal transfections of the reporter and the control. Another consideration in this attempt was that the transfected and un-transfected cells in the system needed to be readily differentiated. By defining only the transfected cells (which, in effect, gives this system a consistent transfection efficiency of practically 100%), the detection sensitivity can be dramatically augmented, considering that normal cell transfection efficiency tends to be relatively low, although the cell lines and methods used can go a long way toward increasing transfection efficiency as well.

The last consideration in our attempt was the ease of detection of the expression of the reporter and control genes. The expression of fluorescence emitting proteins (7,8) in live cells can be detected via flow cytometry without any enzymatic pretreatment, and this is a very simple and easy technique (9). In distinguishing between transfected and un-transfected cells, the cells also must remain intact. The flow cytometric detection of fluorescence emitting reporter and control gene products fulfills this criterion as well. Although the GFP obtained from Aequorea victoria is a standard genetic marker which is used extensively in the monitoring of cellular events, DsRed, a red fluorescence-emitting protein obtained from Discosoma sp., has recently been used successfully for the same purpose (5,6). Thus, we elected to employ both EGFP and DsRed proteins for the construction of our dual reporter vector.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nucleic acids

pEGFP-N1 and pDsRed1-N1, the mother vectors used in the construction of the reporter system described herein, were obtained from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). Chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) reporter vector pCAT®3series and pSV-β-Galactosiase vector were acquired from Promega (Madison, WI). The mouse CD1d1 promoter region was isolated from the mouse genomic P1 vector library (Genome Systems Inc., St. Louis, MO).

Construction of the vector

Multi cloning sites from the NheI to AgeI of the pDsRed2-N1 vector were removed in order to avoid unwanted multiple digestion sites. This was accomplished via the ligation of NheI and AgeI-digested vector after the the cohesive ends had been filled-in with Klenow fragments. The vector was digested with AflII, and again the cohesive ends were filled in with Klenow fragments. pEGFP-N1 was digested with NheI and AflII, and a 1048 bp-fragment harboring EGFP and a multicloning site immediately upstream of the EGFP structural gene was processed to construct blunt ends with Klenow polymerase. This was then inserted into the end-filled AflII site of pDsRed2-N1, from which the MCS had previously been removed in the construction of the dual reporter vector, pRedEGFP. The orientation of each of the components was verified via restriction enzyme digestion. The promoter region of mouse CD1d1 was inserted into the BamHI site of pRedEGFP, and the KpnI and SacI sites upstream of the inserted promoter region were utilized for serial deletion using exonuclease III (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The same promoter regions were also re-cloned into the pCAT®3-enhancer vector, which utilizes chloramphenicol acetyl transferase as a reporter, for the comparison of the promoter activity of both reporter systems.

Transfection and flow cytometry and CAT assay

The plasmid vectors, each harboring different sections of the promoter region, were isolated using a Qiagen (Valencia, CA) Maxi column, and were electro-transfected to Bcl-1, a mouse B lymphocyte, at 960 µfi/300 V. For transfection, 20 µg (microgram) of each plasmid DNA was transfected into 800 µl (microliter) of 2×107 cells/ml of Bcl-1. After transfection, the cells were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Gene expression was monitored at the 48th and 72nd hours after transfection using a FACSCalibur flow cytometry system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells harvested at each time point were washed once in potassium buffered saline (PBS), then re-suspended in an appropriate volume of PBS, and immediately subjected to flow cytometry. Cells transfected with EGFP and DsRed vectors alone were used for the FL1 and FL2 compensations, respectively. Live cells in the forward and side scattering fields were gated in for data acquisition, and the dead cells were gated out during data collection. In each analysis, 104 events of live population were acquired, and the data were analyzed with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). CAT and beta-galactosidase assays were conducted in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We assembled a DsRed gene under the CMV promoter and an EGFP gene without a promoter, but with a multicloning site in which the target promoter could be cloned. The NheI and AflII fragments of the pEGFP-N1 were cloned into the AflII sites of pDsRed1-N1, and the orientations of these components were verified in order to ensure that the EGFP gene harbored all the components necessary for gene expression, with the exception of the promoter region (Fig. 1). The DsRed gene was expressed only in the transfected cells, and these cells could be separated from the majority of the un-transfected cells via flow cytometry. Using this simple flow cytometric separation technique, we hoped that different promoter activities would be compared only using the transfected cells, all of which would manifest DsRed expression. For the transcription activity assay using the dual reporter system, we inserted approximately 1.3 kb of the 5'-untranslational region of mouse CD1d1 into the multicloning site of the pRedEGFP, and serial deletion was conducted after SacI and KpnI digestion in order to generate plasmid vectors harboring different lengths of the promoter region (Fig. 2A). Each of the constructs was then transfected into the CD1d expressing Bcl-1, a mouse B cell lymphoma, via electro-transfection, and these cells were incubated from between 48 hours to 72 hours prior to the performance of flow cytometry analysis. Cells harvested after the incubation periods were washed once in PBS, and were subjected directly to flow cytometry analysis in PBS, without any need for additional steps.

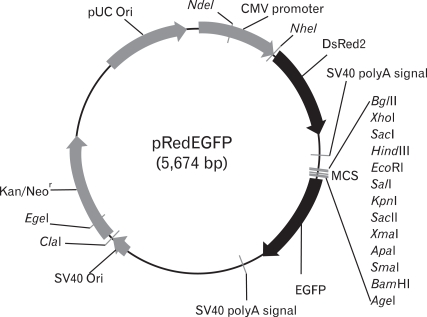

Figure 1.

Construction of the dual reporter vector, pRedEGFP. The CMV promoter-driven DsRed gene, which is expressed constitutively in most mammalian cells, and the promoter-less EGFP gene are delineated within a single vector. The region upstream of EGFP includes multicloning sites for promoter cloning.

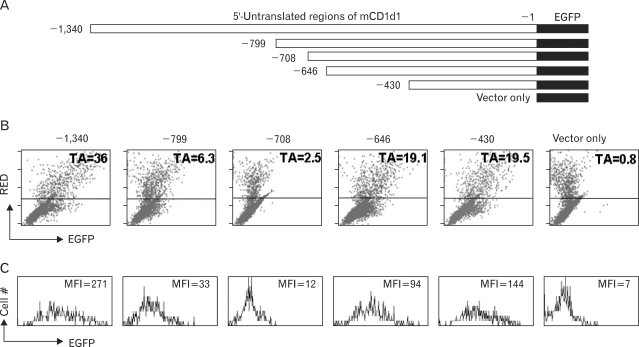

Figure 2.

Expression of EGFP in DsRed-positive cells. (A) Promoter regions of mouse CD1d1 were cloned into the MCS of pRedEGFP and transfected into the Bcl-1 lymphoma cell line. Cells were harvested 72 hours after transfection. (B, C) In flow cytometric analyses, transfected cells, which evidence constitutive DsRed expression (above the horizontal line of each panel), were gated (B), and their EGFP expression is presented in histograms (C). EGFP expression was readily detectable among the DsRed-positive population, although the transfection efficiency was rather low (~5%, the ratio of DsRed-positive cells). The TA (transcription activity) of the DsRed-positive cells was calculated as follows: (MFI of EGFP/MFI of DsRed)×100%. The X and Y-axes of the dot-plot and the X-axis of the histogram-plot were represented on a log scale, from 100 to 104. The Y-axis of histogram-plot is shown as a linear scale.

Although the overall transfection efficiency was low (less than 5% of the total cells were DsRed positive), all of the DsRed positive cells transfected with the full-length promoter were shown to express EGFP. The expression levels and patterns at the 48-hour and 72-hour time points were similar. The levels of DsRed and EGFP expression in the DsRed-positive cells evidenced an exact linear relationship, although the ratio of MFI (mean fluorescence intensity) varied considerably among different constructs (Fig. 2B, C). As each of the plasmid vectors had been separately prepared, the quality and quantity of these preparations could vary, resulting in different MFI values for DsRed expression among the constructed vectors. However, these variations should affect the expression of the reporter EGFP gene in a similar and consistent manner, owing to the fact that the two genes were located within a single vector. Thus, the transcription activity (TA, 100%×(MFI of EGFP/MFI of DsRed)) should already have compensated for any extraneous factors, with the exception of promoter activity itself. The CD1d1 promoter region harboring up to -1,340 (p-1,340) exhibited TA 36, but p-708 and p-799, which contained the promoter regions of up to -708 and -799 respectively, evidenced relative activities of 2.5 and 6.3 among cells within the region in which only the DsRed positive cells had been gated. However, p-430 evidenced a recovery of relative activity, of 19.5, in the same region (Fig. 2B). This suggests that the promoter region up to -430 harbors essential promoter regions of mouse CD1d1, and that the region encompassing -430 to -708 harbors negatively regulating elements. The results also suggest that the region spanning -708 to -1,340 harbors elements that can compensate for the negatively controlling elements. The complete expression pattern and its regulatory elements will be evaluated and published elsewhere.

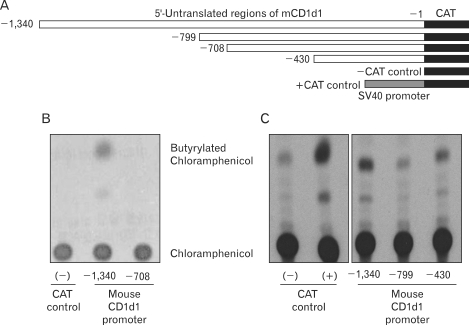

Finally, we attempted to determine whether the reporter system described herein was capable of detecting promoter activity in a manner comparable to that of conventional reporter systems, including the CAT assay system. Several promoter regions used in the dual reporter vector were re-cloned into the CAT expression vector system pCAT®3-Enhancer vector (Promega, Madison, WI), in order to ascertain whether these regions evidenced similar transcription activity in the CAT assay system (Fig. 3A). The CAT activities of each of the promoter fragments were compensated via the activity of beta-galactosidase, which was expressed by the co-transfected control vector, pSV-β-Galactosidase vector. As is shown in Fig. 3B, region -1,340 clearly evidenced CAT activity, whereas region -708 exhibited only nominal enzyme activity. However, p-430 again evidenced a recovery of CAT activity, as was also witnessed using the dual reporter system (Fig. 3C). Thus, we confirmed a pattern of CAT reporter gene expressions identical to that of the EGFP expression pattern observed in the flow cytometric assay. These results indicate that our new dual reporter system does not manifest unusual non-specific expression activity. Furthermore, the difference in the patterns of EGFP expression between constructs -1,340 and -708 was more profound than was the enzyme activity observed using the CAT assay system. This indicates that our flow cytometry assay, employing the dual reporter system, has a higher or at least a similar sensitivity to conventional reporter vector systems such as the CAT assay, in addition to its marked advantage of enhanced ease.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the dual reporter system with the conventional CAT reporter system. The same promoter regions used in the dual reporter vector system were re-cloned into the CAT reporter system, pCAT®3-Enhancer vector (A). Vectors harboring different lengths of the promoter region were cotransfected with pSV-β-Galactosidase vector. The transcriptional activities of each region were determined via Chloramphenicol acetyl transferase activity assays (B, C) after compensation with beta-galactosidase. The pCAT3 control vector without the promoter sequence (pCAT®3-Basic) and the one harboring the SV40 promoter (pCAT®3-Control) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

In a practical sense, some cell lines are quite resistant to gene transfection, and thus are associated with very low transfection efficiency. In such cases, transfection methods and conditions must be optimized for usable results. Our new dual reporter vector may obviate all of these necessary optimizing steps, via the gating in of only the transfected cell population. Furthermore, this vector system necessitates no additional enzymatic assay steps, all of which introduce possible errors, and are both time- and labor-intensive.

Most saliently, the data obtained in this analysis reveal the population dynamics of transfected cells, as each single dot in the dot-plot shows the promoter activity occurring in a single cell. In other words, the results of a single assay using the dual reporter system are commensurate with the sum of thousands of independent experiments conducted with a single cell. In this sense, the relative transcription activity of our dual reporter vector system may reflect the nature of promoter activity more accurately than reporter systems exploiting the enzymatic activity of cell extracts from a mixed population of transfected and untransfected cells.

In this study, we have designed an extremely convenient and efficient mammalian promoter reporter system, in which no enzymatic reaction steps are required for the measurement of promoter activities. This reporter system should allow for more simple and efficient promoter analysis than has been possible in the past.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2009-0062899).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- 1.Dominguez P, Ibaraki K, Robey PG, Hefferan TE, Termine JD, Young MF. Expression of the osteonectin gene potentially controlled by multiple cis- and trans-acting factors in cultured bone cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1991;6:1127–1136. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650061015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorman CM, Moffat LF, Howard BH. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alam J, Cook JL. Reporter genes: application to the study of mammalian gene transcription. Anal Biochem. 1990;188:245–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russo-Marie F, Roederer M, Sager B, Herzenberg LA, Kaiser D. Beta-galactosidase activity in single differentiating bacterial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8194–8198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dietrich C, Maiss E. Red fluorescent protein DsRed from Discosoma sp. as a reporter protein in higher plants. Biotechniques. 2002;32:286–293. doi: 10.2144/02322st02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nancharaiah YV, Wattiau P, Wuertz S, Bathe S, Mohan SV, Wilderer PA, Hausner M. Dual labeling of Pseudomonas putida with fluorescent proteins for in situ monitoring of conjugal transfer of the TOL plasmid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:4846–4852. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4846-4852.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cormack BP, Valdivia RH, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173(1 Spec No):33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross LA, Baird GS, Hoffman RC, Baldridge KK, Tsien RY. The structure of the chromophore within DsRed, a red fluorescent protein from coral. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11990–11995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey HM, Kell DB. Flow cytometry and cell sorting of heterogeneous microbial populations: the importance of single-cell analyses. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:641–696. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.4.641-696.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]