Abstract

The freshwater Dothideomycetes species are an ecological rather than taxonomic group and comprise approximately 178 meiosporic and mitosporic species. Due to convergent or parallel morphological adaptations to aquatic habitats, it is difficult to determine phylogenetic relationships among freshwater taxa and among freshwater, marine and terrestrial taxa based solely on morphology. We conducted molecular sequence-based phylogenetic analyses using nuclear ribosomal sequences (SSU and/or LSU) for 84 isolates of described and undescribed freshwater Dothideomycetes and 85 additional taxa representative of the major orders and families of Dothideomycetes. Results indicated that this ecological group is not monophyletic and all the freshwater taxa, except three aeroaquatic Tubeufiaceae, occur in Pleosporomycetidae as opposed to Dothideomycetidae. Four clades comprised of only freshwater taxa were recovered. The largest of these is the Jahnulales clade consisting of 13 species, two of which are the anamorphs Brachiosphaera tropicalis and Xylomyces chlamydosporus. The second most speciose clade is the Lindgomycetaceae clade consisting of nine taxa including the anamorph Taeniolella typhoides. The Lindgomycetaceae clade consists of taxa formerly described in Massarina, Lophiostoma, and Massariosphaeria e.g., Massarina ingoldiana, Lophiostoma breviappendiculatum, and Massariosphaeria typhicola and several newly described and undescribed taxa. The aquatic family Amniculicolaceae, including three species of Amniculicola, Semimassariosphaeria typhicola and the anamorph, Anguillospora longissima, was well supported. A fourth clade of freshwater species consisting of Tingoldiago graminicola, Lentithecium aquaticum, L. arundinaceum and undescribed taxon A-369-2b was not well supported with maximum likelihood bootstrap and Bayesian posterior probability. Eight freshwater taxa occurred along with terrestrial species in the Lophiostoma clades 1 and 2. Two taxa lacking statistical support for their placement with any taxa included in this study are considered singletons within Pleosporomycetidae. These singletons, Ocala scalariformis, and Lepidopterella palustris, are morphologically distinct from other taxa in Pleosporomycetidae. This study suggests that freshwater Dothideomycetes are related to terrestrial taxa and have adapted to freshwater habitats numerous times. In some cases (Jahnulales and Lindgomycetaceae), species radiation appears to have occurred. Additional collections and molecular study are required to further clarify the phylogeny of this interesting ecological group.

Keywords: Ascomycetes, aquatic, evolution, Jahnulales, Pleosporales

INTRODUCTION

Freshwater ascomycetes comprise a diverse taxonomic assemblage of about 577 species (Shearer et al. 2009). These fungi are mostly saprobic on submerged woody and herbaceous debris and are important in aquatic food webs as decomposers and as a food source to invertebrates (see Gessner et al. 2007, Simonis et al. 2008). Although in the early ascomycete taxonomic literature some species were reported and/or described from plants in or near aquatic habitats, little was noted about whether the fungi were on aerial or submerged parts of their hosts/substrates. For the purpose of this study, we consider freshwater ascomycetes as only those species that occur on submerged substrates; ascomycetes on aerial parts of aquatic plants are considered terrestrial and not dealt with herein.

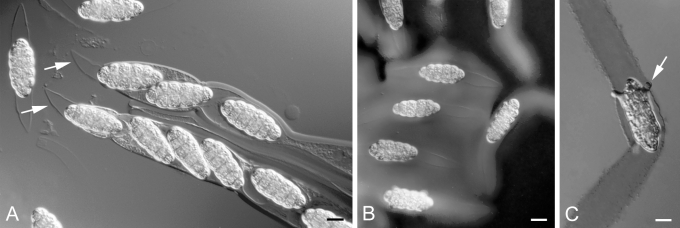

Ingold was the first to recognise that a distinctive freshwater ascomycota might exist and published a series of papers about fungi on submerged substrates in the Lake District, England (Ingold 1951, 1954, 1955, Ingold & Chapman 1952). Ingold was collecting from the submerged stems of aquatic macrophytes in the English Lake District when he discovered the magnificent freshwater Dothideomycete, Macrospora scirpicola on Schoenoplectus lacustris, the lakeshore bulrush (Ingold 1955). This fungus has ascospores equipped with a gelatinous sheath (Fig. 1A) that elongates and becomes sticky after the ascospores are discharged into water (Fig. 1B), a feature thought to improve the probability that ascospores will attach to substrates in moving water (Hyde & Jones 1989, Shearer 1993, Jones 2006). This feature is found in numerous freshwater Dothideomycetes (see species monograph, Shearer et al. 2009). The ascospores also germinate immediately upon contact with a firm substrate (Fig. 1C), which may help them adhere to substrates in moving water. Macrospora scirpicola is one of the earliest known freshwater Dothideomycete species; DeCandolle originally described it in 1832 as Sphaeria scirpicola, and Pringsheim first reported it from freshwater in 1858.

Fig. 1.

Macrospora scirpicola A27-1. A. Ascospores being discharged from bitunicate asci showing bipolar gelatinous appendages. B. Ascospores showing an outer and inner sheath when stained with India ink. C. Ascospore on a glass slide germinating within its gelatinous sheath stained with India ink. Scale Bars: = 20 μm.

The early literature dealing specifically with freshwater ascomycetes, including Dothideomycetes, has been reviewed by Dudka (1963, 1985) and Shearer (1993). Since the 1990's, interest in aquatic ascomycetes has grown and the number of species reported and/or described from freshwater habitats has increased by 370 to a total of 577 taxa (Shearer et al. 2009). For more recent reviews of the freshwater ascomycetes, see: Goh & Hyde (1996), Wong et al. (1998), Shearer (2001), Tsui & Hyde (2003), Shearer et al. (2007), and Raja et al. (2009b). Approximately 30 % of the 577 freshwater ascomycetes are Dothideomycete species, and based on morphology, belong primarily in Pleosporales or secondarily in Jahnulales. Exceptions include four species in Capnodiales (Mycosphaerellaceae) and four species in Tubeufiaceae.

Molecular studies of freshwater Dothideomycetes have been of four basic types. The first type was to determine the overall taxonomic placement of one or more undescribed taxa (e.g., Inderbitzin et al. 2001, Cai & Hyde 2007, Kodsueb et al. 2007, Cai et al. 2008, Zhang et al. 2008a, b, 2009a, c, Raja et al. 2010). In these studies one or more nuclear genes were sequenced to place a newly described fungus in an order or family within the Dothideomycetes framework. In the second type, the goal was to use single or multi-gene phylogenies to elucidate the evolutionary relationships among a group of closely related taxa, and to evaluate which suite of morphological characters might be informative for predicting evolutionary relationships and which might be misleading or homoplasious (e.g., Liew et al. 2002, Pang et al. 2002, Campbell et al. 2006, 2007, Tsui & Berbee 2006, Zhang et al. 2009a, c, Hirayama et al. 2010). The third type of molecular study was used to identify relationships between aquatic anamorphic and teleomorphic Dothideomycetes (see Baschien 2003, Belliveau & Bärlocher 2005, Baschien et al. 2006, Campbell et al. 2006, Tsui et al. 2006, 2007). Here the goal was to use sequence data to place the aquatic anamorphs within the teleomorph phylogeny to better understand the phylogenetic affinities of freshwater anamorphs. The fourth type addressed the evolution of freshwater ascomycetes (Vijaykrishna et al. 2006).

Dothideomycetes possess freshwater hyphomycetous anamorphs rather rarely. Approximately only 10 % of 86 aquatic hyphomycete species, which are at least tentatively assigned to an ascomycete family, order or class, have affinity to Dothideomycetes. Four of them are connected to known teleomorphs via cultural studies: Tumularia aquatica to Massarina aquatica (Webster 1965), Anguillospora longissima to Massarina sp. (Willoughby & Archer 1973), Clavariopsis aquatica to Massarina sp. (Webster & Descals 1979), and Aquaphila albicans to Tubeufia asiana (Tsui et al. 2007). Four connections are published on the basis of molecular phylogenetic rather than cultural studies, but some of these connections are controversial and require further molecular study using additional genes and/or cultural studies. These connections include: Anguillospora rubescens in Dothideales (Belliveau & Bärlocher 2005), Lemonniera pseudofloscula and Goniopila monticola in Pleosporales (Campbell et al. 2006), and Mycocentrospora acerina to Mycosphaerellaceae (Stewart et al. 1999). (Note: Data on affinity of Mycocentrospora is not explicitly given in the text, but is in the GenBank entry AY266155).

Most of the above-mentioned molecular studies have used limited taxon sampling of various orders and families currently in the Dothideomycetes, as well as a single gene (either nuc SSU rDNA or nuc LSU rDNA) to understand the phylogenetic affinities of the freshwater taxa. A review of past molecular phylogenetic studies of freshwater Dothideomycetes revealed that very few of the approximately 170 freshwater Dothideomycete species have been sequenced. In addition, different genes and different regions of the same genes have been sequenced for different taxa making any comprehensive molecular analysis impossible. Clearly more sequences are needed for taxa already studied and more taxa need to be sequenced if we are to understand the phylogeny of the freshwater Dothideomycetes.

The purpose of this study, therefore, was to obtain two gene sequences (nuc SSU rDNA & nuc LSU rDNA) for as many freshwater Dothideomycetes (teleomorphs and anamorphs) as possible to conduct molecular sequence analyses to place these taxa within a phylogenetic framework comprised of a broader taxonomic and ecological taxon sampling from major orders and families using the most current classification system proposed for the Dothideomycetes (Schoch et al. 2006, Hibbett et al. 2007).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Taxon sampling

The species used in this study, their isolate numbers, sources and GenBank accession numbers are listed in Table 1 - see online Supplementary Information. The datasets contained 156 taxa for the SSU and 160 taxa for LSU, while the combined dataset consisted of 169 taxa with some missing data. Twenty-two aquatic taxa were newly sequenced for the SSU gene and/or the LSU gene, while sequences of several other aquatic taxa included in the analyses were obtained from very recently published or unpublished phylogenetic studies of freshwater fungi (Zhang et al. 2008a, b, 2009a, c, Hirayama et al. 2010, Raja et al. 2010). Sequences of a wide array of taxa representing various orders and families within the Dothideomycetes based on Schoch et al. (2006) were included in this study. In addition to taxa from the Dothideomycetes, members of Arthoniomycetes, Lecanoromycetes, Sordariomycetes and Leotiomycetes were also included in the analyses. Members of the Pezizomycetes were used as outgroup taxa.

Table 1.

Species used in this study.

| Species | Isolate number | Source | GenBank No. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSU | LSU | |||

| Aliquandostipite crystallinus* | F83-1 | Raja & Shearer | GU266221 | GU266239 |

| AF007 | — | EF175631 | EF175652 | |

| R76-1 | — | EF175630 | EF175651 | |

| Aliquandostipite khaoyaiensis | F89-1 | Raja & Shearer | EF175625 | EF175647 |

| SS2961 | BCC 15577 | EF175626 | EF175648 | |

| SS3028 | BCC 23986 | EF175627 | EF175649 | |

| SS3321 | BCC 18283 | EF175628 | EF175650 | |

| Aliquandostipite separans | — | AF438179 | — | |

| Aliquandostipite siamensiae | SS81.02 | BCC 3417 | EF175645 | EF175666 |

| Allewia eureka | DAOM 195275 | DQ677994 | DQ678044 | |

| Alternaria alternata | CBS 916.96 | DQ678031 | DQ678082 | |

| Alternaria sp. (as Clathrospora diplospora) | CBS 174.51 | DQ678016 | DQ678068 | |

| Amniculicola immersa | — | KD Hyde | GU456295 | FJ795498 |

| Amniculicola lignicola | — | KD Hyde | EF493863 | EF493861 |

| Amniculicola parva | KD Hyde | GU296134 | FJ795497 | |

| Anguillospora longissima* | CS869-1D | Shearer | GU266222 | GU266240 |

| Aquaticheirospora lignicola | — | AY736377 | AY736378 | |

| Aquaphila albicans | BCC 3543 | DQ341093 | DQ341101 | |

| Ascochyta pisi var. pisi | CBS 126.54 | DQ678018 | DQ678070 | |

| Ascorhombispora aquatica | — | — | EU196548 | |

| Bimuria novae-zelandiae | CBS 107.19 | AY016338 | AY016356 | |

| Botryosphaeria dothidea | CBS 115476 | DQ677998 | DQ678051 | |

| “Botryosphaeria” tsugae | CBS 418.64 | AF271127 | DQ767655 | |

| Botryotinia fuckeliana | OSC 100012 | AY544695 | AY544651 | |

| Brachiosphaera tropicalis | E192-1 | Shearer | GU266223 | EF175653 |

| Byssothecium circinans | CBS 675.92 | AY016339 | AY016357 | |

| Caloscypha fulgens | OSC 100062 | DQ247807 | DQ247799 | |

| Capnodium coffeae | CBS 147.52 | DQ247808 | DQ247800 | |

| Capnodium salicinum | CBS 131.34 | DQ6779977 | DQ678050 | |

| Capronia pilosella | DAOM 216387 | DQ823106 | DQ823099 | |

| Coccomyces strobi | CBS 202.91 | DQ471027 | DQ470975 | |

| Cheirosporium triseriale | — | — | EU413954 | |

| Cochliobolus heterostrophus | CBS 134.39 | AY544727 | AY544645 | |

| Cochliobolus sativus | DAOM 216378 | DQ677995 | DQ678045 | |

| Coniothyrium obiones | CBS 453.68 | DQ678001 | DQ678054 | |

| Coniothyrium palmarum | CBS 400.71 | DQ678008 | DQ767653 | |

| Cucurbitaria elongata | CBS 171.55 | DQ678009 | DQ678061 | |

| Delitschia winteri | CBS 225.62 | DQ678026 | DQ678077 | |

| Dendryphiella arenaria | CBS 181.85 | DQ471022 | DQ470971 | |

| Dendyphiopsis atra | DAOM 231155 | DQ677996 | DQ678046 | |

| Dermea acerina | CBS 161.38 | DQ247809 | DQ247801 | |

| Didymella cucurbitacearum | IMI 373225 | AY293779 | AY293792 | |

| Dothidea insculpta | CBS 189.58 | DQ247810 | DQ247802 | |

| Dothidea sambuci | DAOM 231303 | AY544722 | AY544681 | |

| Dothiora cannabinae | CBS 373.71 | DQ479933 | DQ470984 | |

| Elsinoë phaseoli | CBS 165.31 | DQ678042 | DQ678095 | |

| Elsinoë veneta | CBS 164.29 | DQ678007 | DQ678060 | |

| Gloniopsis praelonga | CBS 112415 | FJ161134 | FJ161173 | |

| Gloniopsis smilacis | CBS 114601 | FJ161135 | FJ161174 | |

| Guignardia bidwelli | CBS 237.48 | DQ678034 | DQ678085 | |

| Helicascus kanaloanus | ATCC 18591 | AF053729 | — | |

| Helicomyces roseus | CBS 283.51 | DQ678032 | DQ678083 | |

| Herpotrichia diffusa | CBS 250.62 | DQ678019 | DQ678071 | |

| Herpotrichia juniperi | CBS 200.31 | DQ678029 | DQ678080 | |

| Jahnula appendiculata* | AF285-3 | Shearer | GU266224 | GU266241 |

| Jahnula aquatica | R68-1 | Raja & Shearer | EF175633 | EF175655 |

| R68-2 | Raja & Shearer | EF175632 | NA | |

| Jahnula bipileata | F49-1 | MYA 4173 | EF175635 | EF175657 |

| AF220-1 | Shearer | EF175634 | EF175656 | |

| Jahnula bipolaris | SS44 | BCC 3390 | EF175637 | EF175658 |

| A421 | Shearer | EF175636 | — | |

| Jahnula granulosa | SS1562 | BCC24222 | EF175638 | EF175659 |

| Jahnula potamophila* | F111-1 | Raja & Shearer | GU266225 | GU266242 |

| Jahnula rostrata | F4-3 | MYA4176 | GU266226 | EF175660 |

| Jahnula sangamonensis | A482-1B | MYA4174 | EF175640 | EF175662 |

| A402-1B | Shearer | EF175639 | EF175661 | |

| F81 | MYA4175 | EF175641 | EF175663 | |

| Jahnula seychellensis | SS2133.1 | BCC 14207 | EF175644 | EF175665 |

| SS2113.2 | BCC 12957 | EF175643 | EF175664 | |

| A492 | Shearer | EF175642 | GU266243 | |

| Kirschsteiniothelia aethiops | CBS 109.53 | AY016344 | AY016361 | |

| Kirschsteiniothelia elaterascus | A22-11B-/ | — | AF053728 | — |

| — | AY787934 | |||

| Lecanora hybocarpa | DUKE 03.07.04-2 | DQ782883 | DQ782910 | |

| Lentithecium aquaticum | CBS 123099 | FJ95477 | FJ795434 | |

| Lentithecium arundinaceum | CBS 619.86 | DQ813513 | DQ813509 | |

| Lemonniera pseudofloscula | CCM F-0484 | — | DQ267631 | |

| CCM F-43294 | — | DQ267632 | ||

| Leotia lubrica | OSC100001 | AY544687 | AY544644 | |

| Lepidopterella palustris* | F32-3 | Raja & Shearer | GU266227 | GU266244 |

| Leptosphaeria maculans | DAOM 229267 | DQ470993 | DQ470946 | |

| Lepidosphaeria nicotiae | CBS 101341 | — | DQ678067 | |

| Lindgomyces cinctosporae | R56-1 | AB522430 | AB522431 | |

| R56-3 | Raja & Shearer | GU266238 | GU266245 | |

| Lindgomyces breviappendiculatus | KT 215 | JCM 12702/MAFF 239291 | AB521733 | AB521748 |

| KT 1399 | JCM 12701/MAFF 239292 | AB521734 | AB521749 | |

| Lindgomyces ingoldianus | A39-1 | ATCC200398 | AB521719 | AB521736 |

| KH 100 | JCM 16479 | AB521720 | AB521737 | |

| Lindgomyces sp. | KH 241 | JCM16480 | AB521721 | AB521738 |

| Lindgomyces rotundatus | KT 966 | JCM 16481/MAFF 239473 | AB521722 | AB521739 |

| KT 1096 | JCM 16482 | AB521723 | AB521740 | |

| KH 114 | JCM 16484 | AB521725 | AB521742 | |

| KT1107 | JCM 16483 | AB521724 | AB521741 | |

| Lophiostoma arundinis | CBS 269.34 | DQ782383 | DQ782384 | |

| Lophiostoma crenatum | CBS 629.86 | DQ678017 | DQ678069 | |

| Lophiostoma glabrotunicatum | IFRD 2012 | FJ795481 | FJ795438 | |

| Lophiostoma macrostomum | KT 635 | JCM 13545 | AB521731 | AB433273 |

| KT 709 | JCM 13546 MAFF 239447 | AB521732 | AB433274 | |

| SSU | LSU | |||

| Lophium mytilinum | CBS 269.34 | DQ678030 | DQ678081 | |

| Massaria platani | CBS 221.37 | DQ678013 | DQ678065 | |

| Massarina australiensis | — | AF164364 | — | |

| Massarina bipolaris | — | AF164365 | — | |

| Massarina eburnea | H 3953 | JCM 14422 | AB521718 | AB521735 |

| — | AF164366 | — | ||

| — | AF164367 | |||

| Massariosphaeria typhicola | KT 667 | MAFF 239218 | AB521729 | AB521746 |

| KT 797 | MAFF 239219 | AB521730 | AB521747 | |

| Megalohypha aqua-dulces* | AF005-2a | — | GU266228 | EF175667 |

| AF005-2b | — | — | EF175668 | |

| Melanomma radicans | ATCC 42522 | U43461 | U43479 | |

| Montagnula opulenta | CBS 168.34 | AF164370 | DQ678086 | |

| Mycosphaerella graminicola | CBS 292.38 | DQ678033 | DQ678084 | |

| Myriangium duriaei | CBS 260.36 | AY016347 | DQ678059 | |

| Mytilinidion andinense | EB 0330 (CBS 123562 | FJ161159 | FJ161199 | |

| Mytilinidion mytilinellum | CBS 303.34 | FJ161144 | FJ161184 | |

| Neofusicoccum ribis | CBS 115475 | DQ678000 | DQ678053 | |

| Neurospora crassa | BROAD | X04971 | AF286411 | |

| Ocala scalariformis* | F121-1 | Raja & Shearer | GU266229 | — |

| Ophiosphaerella herpotricha | CBS 620.86 | DQ678010 | DQ678062 | |

| CBS 240.31 | DQ767650 | DQ767656 | ||

| Phaeodothis winteri | CBS 182.58 | DQ678021 | DQ678073 | |

| Phaeosphaeria avenaria | DAOM 226215 | AY544725 | AY544684 | |

| Phaeosphaeria eustoma | CBS 573.86 | DQ678011 | DQ678063 | |

| Phoma herbarum | CBS 276.37 | DQ678014 | DQ678066 | |

| Piedraia hortae | CBS 480.64 | AY016349 | AY016366 | |

| Pleomassaria siparia | CBS 279.74 | DQ678027 | DQ678078 | |

| Pleospora herbarum var. herbarum | CBS 714.68 | DQ767648 | DQ678049 | |

| CBS 514.72 | DQ247812 | DQ247804 | ||

| Preussia terricola | DAOM 230091 | AY544726 | AY544686 | |

| Pseudocercospora fijiensis | OSC 100622 | DQ767652 | DQ678098 | |

| Pyrenophora phaeocomes | DAOM 222769 | DQ499595 | DQ499596 | |

| Pyrenophora tritici-repentis | OSC 100066 | AY544716 | AY544672 | |

| Pyronema domesticum | CBS 666.98 | DQ247813 | DQ247805 | |

| Quintaria lignatilis | — | QLU43462 | — | |

| Ramularia endophylla | CBS 113265 | DQ471017 | DQ470920 | |

| Roccellographa cretacea | DUKE 191Bc | DQ883705 | DQ883696 | |

| Schismatomma decolorans | DUKE 0047570 | AY548809 | AY548815 | |

| Semimassariosphaeria typhicola** | GU296174 | FJ795504 | ||

| Spencermartinsia viticola | CBS 117009 | DQ678036 | DQ678087 | |

| Sporormiella minima | CBS 524.50 | DQ678003 | DQ678056 | |

| Sporidesmium sp. | FH14 | — | GU266230 | — |

| Taeniolella typhoides | CCM F-10198/extype | GU266231 | — | |

| Tingoldiago graminicola | KH 68 | JCM 16485 | AB521726 | AB521743 |

| KT 891/ | MAFF 239472 | AB521727 | AB521744 | |

| KH 155/ | JCM 16486 | AB521728 | AB521745 | |

| Trematosphaeria hydrophila | IFRD 2037 | GU261721 | — | |

| Trematosphaeria heterospora | CBS 644.86 | AY016354 | AY016369 | |

| Trematosphaeria pertusa | CBS 400.97 | DQ678020 | DQ678072 | |

| Trematosphaeria wegeliniana | CBS 123124 | GU261720 | GU261722 | |

| SSU | LSU | |||

| Tubeufia cerea | CBS 254.75 | DQ471034 | DQ470982 | |

| Tubeufia helicomyces | — | DQ767649 | DQ767654 | |

| Tumularia aquatica | CCM F-02081 | AY357287 | — | |

| Ulospora bilgramii | CBS 110020 | DQ678025 | DQ678076 | |

| Verruculina enalia | CBS 304.66 | DQ678028 | DQ678079 | |

| Westerdykella cylindrica | CBS 454.72 | AY016355 | AY004343 | |

| Wicklowia aquatica* | F76-2 | CBS 125634 | GU266232 | GU045445 |

| Xylaria hypoxylon | OSC 100004 | AY544719 | AY544676 | |

| Xylomyces chlamydosporus* | H58-4 | GU266233 | EF175669 | |

| Xylomyces elegans* | H80-1 | GU266234 | — | |

| Undescribed taxon A25-1* | Shearer | — | GU266246 | |

| Undescribed taxon R60-1* | Raja & Shearer | GU266235 | GU266247 | |

| Undescribed taxon F65-1 | Shearer | GU266236 | GU266248 | |

| Undescribed taxon A369-1* | Raja & Shearer | — | GU266249 | |

| Undescribed taxon F80-1* | Shearer | GU266237 | GU266250 | |

| Undescribed taxon A164-1C* | Shearer | — | GU266251 | |

| Undescribed taxon A164-1D* | Shearer | — | GU266252 | |

| Undescribed taxon A183-1C* | Shearer | — | GU266253 | |

| Undescribed taxon A183-1D* | Shearer | — | GU266254 | |

| Undescribed taxon A273-1C* | Shearer | GU266255 | ||

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

For extraction of genomic DNA, mycelium from axenic cultures was scraped with a sterile scalpel from nutrient agar in plastic Petri dishes and ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle. Approximately 400 μL of AP1 buffer from the DNAeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, California) was added to the mycelial powder and DNA was extracted following the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA was finally eluted in 30 μL distilled water. Fragments of SSU and LSU nrDNA were amplified by PCR using PuReTaq™ Ready-To-Go PCR beads (Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, New York) according to Promputtha & Miller (2010). Primers NS1 and NS4 for SSU (White et al. 1990) and LROR and LR6 for LSU (Vilgalys & Hester 1990, Rehner & Samuels 1995) were used for PCR reactions in addition to 2.5 μL of BSA (bovine serum albumin, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and/or 2.5 μL of DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). PCR products were purified to remove excess primers, dNTPs and nonspecific amplification products with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, California). Purified PCR products were used in 11 μL sequencing reactions with BigDye Terminators v. 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California) in combination with the following SSU primers: NS1, NS2, NS3, NS4 (White et al. 1990), and LSU primers: LROR, LR3, LR3R, LR6 (Vilgalys & Hester 1999, Rehner & Samuels 1995). Sequences were generated on an Applied Biosystems 3730XL high-throughput capillary sequencer at the UIUC Biotech facility. Sequences were also obtained using other methods outlined in Hirayama et al. (2010) and Zhang et al. (2009c).

Sequence alignment

Each sequence fragment obtained was subjected to an individual blast search to verify its identity. Individual fragments were edited and contigs were assembled using Sequencher v. 4.9 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor Michigan). Newly obtained sequences were aligned with sequences from GenBank using the multiple sequence alignment program, MUSCLE® (Edgar 2004) with default parameters in operation. MUSCLE® was implemented using the programs Seaview (Galtier et al. 1996) and Geneious Pro v. 4.7.6 (Biomatters) (Drummond et al. 2006). Sequences were aligned in MUSCLE using a previous (trusted) alignment made by eye in Sequencher v. 4.9, based on a method called “jump-starting alignment” (Morrisson 2006). The final alignment was again optimised by eye and manually corrected using Se-Al v. 2.0a8 (Rambaut 1996) and McClade v. 4.08 (Maddison & Maddison 2000).

Phylogenetic analyses

Separate alignments were made for SSU and LSU sequences. The aligned SSU and LSU datasets were first analysed separately and then the individual datasets were concatenated into a combined dataset. Prior to combining the datasets, the possibility of clade conflict was explored. Independent maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were run with a GTR model including invariable sites and discrete gamma shape distribution and 100 bootstrap replicates were performed using the program Seaview (Galtier et al. 1996). The individual SSU and LSU phylogenies were then examined for conflict by comparing clades with bootstrap support (Wiens 1998). If clades were < 50 % they were considered weakly supported, whereas 70–100 % indicated a strong support. We combined the datasets since there was no obvious clade conflict for 90 % of the taxa included in our study. Subsequent analyses were then performed on the combined SSU + LSU dataset. In the final combined dataset, 13 ambiguously aligned regions were delimited and excluded from all further analyses.

Modeltest v. 3.7 (Posada & Crandall 1998) was used to determine the best-fit model of evolution for the dataset. ML analyses were performed using RAxML v. 7.0.4 (Stamatakis 2006) with 100 successive searches and the best-fit model, which was the (GTR) model with unequal base frequencies (freqA = 0.2666, freqC = 0.2263, freqG = 0.2664, freqT = 0.2407), a substitution rate matrix (A<–>C = 0.9722, A<–>G = 2.7980, A<–>T = 1.1434, C<–>G = 0.6546, C<–>T = 5.1836, G<–>T = 1.0000), a proportion of invariable sites (– 0.2959) and a gamma distribution shape parameter (– 0.4649). For the ML analyses constant characters were included and again 13 ambiguously aligned regions were excluded. Each search was performed using a randomised starting tree with a rapid hill climbing option. One thousand fast bootstrap pseudoreplicates (Stamatakis et al. 2008) were run under the same conditions.

Bayesian Metropolis Coupled Markov Chain Monte Carlo (B-MCMCMC) analyses were performed with MrBayes v. 3.1.2 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003) as an additional means of assessing branch support. Constant characters were included. A comparable model to the ML analyses was used to run 10 million generations with trees sampled every 1 000th generation resulting in 10 000 total trees. The first 1 000 trees which extended beyond the burn-in phase in each analysis were discarded and the remaining 9 000 trees were used to calculate posterior probabilities. The consensus of 9 000 trees was viewed in PAUP v. 4.0b10 (Swofford 2002). The analysis was repeated twice each with four Markov Chains for the dataset starting from different random trees.

RESULTS

Sequence alignment

The complete dataset (combined SSU and LSU alignment) along with intron regions and ambiguous characters had 169 taxa and 7 264 characters. The dataset consisted of 169 taxa and 3 641 characters after removal of intron regions. We then delimited and removed 548 ambiguous characters from the final alignment along with characters from the 5' and 3' end regions due to missing information in most taxa included in the alignment. The final dataset after removal of all the intron regions and 13 ambiguous regions along with missing data from the 5' and 3' ends consisted of 1816 characters. There were no significant conflicts among the clades in the separate SSU and LSU analyses in either SSU or LSU datasets (data not shown) therefore we used all 169 taxa in the combined SSU and LSU analyses.

Phylogenetic analyses

The combined matrix analysed in this study produced 852 distinct alignment patterns and the most likely tree (Fig. 2) had a log likelihood of -17187.0385 compared to the average (100 trees) of -17191.7927. Several major clades presented in the multi-gene phylogeny of Schoch et al. (2006) were recovered in our combined SSU and LSU phylogeny. Leotiomycetes was not monophyletic in our analyses, but this relationship was not supported.

Fig. 2.

Freshwater Dothideomycetes phylogeny. The most likely tree (Ln L =

-17187.0385) after 100 replicates of a RAxML analysis of combined SSU and LSU

data. Orders, classes, and families are indicated on the tree. ML bootstrap

support values greater than 70 % are indicated along with Bayesian posterior

probabilities ≥ 95 % for nodes. Members of Pezizomycetes are used

as outgroup taxa. Freshwater lineages are labeled as Clades A–D and are

shaded in blue and taxa isolated and described from freshwater habitats are

indicated with Fresh W. Ascospore modifications are indicated by:

= greatly elongating

sheath;

= greatly elongating

sheath;  = thin to thick

non-elongating sheath;

= thin to thick

non-elongating sheath;  =

apical appendages;

=

apical appendages;  = no

sheath;

= no

sheath;  = gelatinous pads.

Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site.

= gelatinous pads.

Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site.

Eighty-four Dothideomycete isolates from freshwater habitats, including meiosporic and mitosporic representatives, were included in this study. The majority of freshwater Dothideomycetes had phylogenetic affinities to taxa in Pleosporales (Fig. 2). Four major clades (A–D) of freshwater fungi were recovered, of which three clades received ≥ 70 % Maximum Likelihood Bootstrap (MLB) support and ≥ 90% Bayesian Posterior Probability (BPP) (Fig. 2). Lentitheciaceae (Clade A) included six taxa, together with undescribed taxon A369-2B but was not supported by either MLB or BPP. Amniculicolaceae (Clade B) was well supported with 97 % ML bootstrap support and 100 % BPP. Lindgomycetaceae (Clade C) was also supported with 77 % MLB and 100 % BPP values. Jahnulales (Clade D) received 100 % MLB and 100 % BPP support and formed a strong monophyletic group.

Eight undescribed freshwater Dothideomycetes were dispersed throughout the Pleosporomycetidae as follows: A369-2B in Lentitheciaceae; F80-1 as sister taxon to K. elaterascus; A164 and A183 in Lophiostomataceae 1; A-25-1, F-60, and F-65 in Lindgomycetaceae; and A273-1c in Jahnulales. A few singletons such as Lepidopterella palustris and Ocala scalariformis are on single lineages without any relationships to known groups included in the analyses.

The anamorph genus Xylomyces was polyphyletic, with one species, X. elegans, placed with Massarina species in the Pleosporales, and the other, X. chlamydosporus, placed within Jahnulales (Fig. 2). The affinity of Anguillospora longissima (CS869-1D, Shearer isolate) to Amniculicola lignicola, A. immersa and A. parva (Fig. 2) confirms this relationship reported previously for a different isolate of A. longissima (Zhang et al. 2009a). Tumularia aquatica, originally assigned to Massarina aquatica (Webster 1965) was placed with Lophiostoma glabrotunicatum, an aquatic fungus collected in mountain streams in France on submerged wood of Alnus glutinosa, Fagus sylvatica and Salix sp. (Zhang et al. 2009c). Taeniolella typhoides occurred in a well-supported group with members of Lindgomycetaceae in Pleosporales. Lemonniera pseudofloscula isolates occurred among terrestrial taxa as a highly supported sister taxon to a clade of Alternaria alternata, Alternaria sp. and Allewia eureka. This placement is somewhat controversial and a more detailed study with additional isolates and more gene regions should be carried out.

DISCUSSION

Within Dothideomycetes, the freshwater species occur in Pleosporomycetidae but not Dothideomycetidae. It is interesting to speculate on possible reasons for this pattern. First, overall there are more taxa in the Pleosporomycetidae than Dothideomycetidae resulting in a numerical imbalance between subclasses in most ecological and taxonomic groups. Second, many of the orders in Dothideomycetidae contain specialised plant pathogens, e.g., Capnodiales, Myriangiales, and Botryosphaeriales, many of which grow on leaves. It is possible that such specialised fungi have lost the genetic potential to adapt to a submerged, saprobic lifestyle. Third, the absence of pseudoparaphyses in Dothideomycetidae taxa may limit survival in aquatic habitats with fluctuating water levels. Pseudoparaphyses of aquatic species in Pleosporomycetidae are often abundant and surrounded by gel, which may protect the asci from desiccation during dry conditions. There is currently no experimental evidence, however, to support this idea.

Freshwater Dothideomycete species are distributed throughout the Pleosporomycetidae (Fig. 2). Several clades, however, contain numerous freshwater species and merit discussion. Clade A (Lentitheciaceae), which consists entirely of freshwater taxa, is not well supported in this study (Fig. 2). Reasons for this lack of support are not clear at this time. For a discussion of this clade, see Zhang et al. (2009b; this volume). The well-supported Clade B (Amniculicolaceae) consists of four freshwater teleomorph species and one aquatic hyphomycete anamorph species. This family is established and described in detail by Zhang et al. (2009b; this volume).

A third exclusively freshwater lineage is Clade C (Lindgomycetaceae) (Fig. 2). This well supported clade was first revealed during a recent molecular sequence-based study of Massarina ingoldiana Shearer & Hyde s. l. (Hirayama et al. 2010). A number of dothideomycetous aquatic species that have 1-septate, hyaline ascospores surrounded by a prominent gelatinous sheath that elongates greatly in water were included in this study. Analyses of a combined dataset of SSU and LSU sequences for a number of aquatic isolates of M. ingoldiana and other morphologically similar fungi along with the type specimens of Massarina and Lophiostoma were conducted. Their results showed that none of the aquatic taxa belonged in Massarina or Lophiostoma and that convergent evolution in ascospore morphology had occurred, confounding systematic placement based on ascospore morphology. Our results support the study by Hirayama et al. (2010) which found that taxa with 1-septate, hyaline ascospores with a large, elongating gelatinous sheath have evolved independently in several lineages within Dothideomycetes (Lentitheciaceae, Lindgomycetaceae, and Aliquandostipitaceae) (Fig. 2). Thus in freshwater Dothideomycetes, this form of the gelatinous sheath is not taxonomically informative at the family or genus level.

Clade D (Jahnulales) contains the greatest number of freshwater species (Fig. 2). The type species of Jahnula, J. aquatica, was described as Amphisphaeria aquatica by Plöttner and Kirschstein in 1906 from Salix wood in a wet ditch in Germany. Kirschstein (1936) subsequently changed the name of this fungus to Jahnula. The genus remained monotypic until 1999, when Hyde & Wong (1999) described five new tropical species based on morphological data. Currently, Jahnula and Aliquandostipite, a genus morphologically similar to Jahnula that was established by Inderbitzen et al. (2001), represent a well-supported lineage in Dothideomycetidae based on molecular and morphological data (Inderbitzen et al. 2001, Pang et al. 2002, Campbell et al. 2007, Suetrong et al. 2009, 2010). Pang et al. (2002) established a new order, Jahnulales, for this group. Jahnulales now contains numerous species representing four meiosporic genera and two mitosporic genera from freshwater habitats (Hyde 1992, Hyde & Wong 1999, Pang et al. 2002, Pinruan et al. 2002, Raja et al. 2005, 2008, Ferrer et al. 2007, Raja & Shearer 2006, 2007). Manglicola guatemalensis, collected from mangroves, was recently confirmed to belong in Jahnulales (Suetrong et al. 2010). There appear to be four, possibly five, separate lineages within Jahnulales, but further molecular work is needed to confirm these lineages. Species in this clade are well adapted for aquatic habitats with large-celled pseudothecia and ascospores filled with lipid guttules and equipped with a variety of gelatinous appendages, pads and sheaths (Fig. 2). Thus far, all members in the order have broad vegetative hyphae (10–40 μm) that attach the fungi to softened, submerged wood.

Clade Lophiostomataceae 1 was well supported as a whole in this study and studies by Tanaka & Hosoya (2008) and Zhang et al. (2009c), but relationships within this clade were not well resolved. Several taxa within this clade are undescribed and additional morphological and molecular data are needed to further resolve relationships within this group.

Two interesting freshwater taxa in Dothideomycetidae included in this study, Ocala scalariformis and Lepidopterella palustris, did not show strong phylogenetic affinities with any of the major families and orders included in the Dothideomycetes (Fig. 2). These so called singletons each has a distinctive combination of morphological characteristics that perhaps make them unique among other Dothideomycetes taxa included in the phylogeny. Ocala scalariformis possesses morphological characters that include superficial to erumpent, globose to subglobose, hyaline perithecial ascomata with an ostiole; cellular pseudoparaphyses; fissitunicate asci; and hyaline, 1-septate, thick-walled ascospores with appendages (Raja et al. 2009a). However, based on the combined SSU and LSU phylogeny, Ocala scalariformis is placed as basal to the Jahnulales, without any statistical support. Lepidopterella palustris has black, cleistothecial ascomata appearing as raised dome-shaped structures on the substrate; hamathecium of hyaline, septate, narrow pseudoparaphyses not embedded in a gel matrix; thick-walled, globose to subglobose, broadly rounded, fissitunicate asci; and brown butterfly shaped ascospores (Shearer & Crane 1980, Raja & Shearer 2008). Based on our phylogeny it forms a single branch by itself, basal to the Mytilindiales with moderate bootstrap support (Fig. 2). It is possible that these singletons represent new lineages currently unknown in the Dothideomycetes.

Belliveau & Baerlocher (2005) showed that aquatic hyphomycetes have multiple origins within the ascomycetes. In this study, we included some hyphomycete taxa that had phyologenetic affinities to the Dothideomycetes based on previous studies (Belliveau & Bärlocher 2005, Campbell et al. 2006, 2007, Zhang et al. 2009c). These taxa are: Anguillospora longissima, Lemonniera pseudofloscula, Taeniolella typhoides, Tumularia aquatica, and Brachiosphaera tropicalis. Previous studies showed that Anguillospora longissima had a strong affinity to Pleosporales and was a sister species to Kirschsteiniothelia maritima (Baschien 2003, Belliveau & Bärlocher 2005). In contrast, Voglmayr (2004) reported a close relationship between an aeroaquatic fungus, Spirosphaera cupreorufescens, and A. longissima. Baschien et al. (2006) confirmed the close relationships of the five isolates of A. longissima to Spirosphaera cupreorufescens. Zhang et al. (2009c) in a maximum parsimony tree generated from partial 28S rDNA gene sequences showed a 91 % bootstrap support for a clade formed by A. longissima, Spirosphaera cupreorufescens, Repetophragma ontariense and three species of Amniculicola. In our analyses, A. longissima is placed in the new aquatic family Amniculicolaceae (Clade B) Fig. 2 (See Zhang et al. 2009b; this volume).

Taeniolella typhoides was described without a teleomorph. Here it forms a well-supported sister clade with Massariosphaeria typhicola. The epithet of T. typhoides may indicate some relationship to Typha, but this is a casual coincidence only as “typhoides” is for “similar to Typha”. The teleomorph of Taeniolella is Glyphium, Mytilinidiales (Kirk et al. 2008).

Tumularia aquatica is the type species of Tumularia and was connected by Webster (1965) to the teleomorph, Massarina aquatica. Massarina aquatica was later recombined on the basis of morphology in Lophiostoma as L. aquatica (Hyde et al. 2002). In this study, T. aquatica is placed with Lophiostoma glabrotunicatum in the Lophiostomataceae 2/Melannomataceae Clade, but lacks significant bootstrap support (Fig. 2).

Brachiosphaera tropicalis has conidia very similar to those of Actinosporella megalospora and the two species are sometimes confused with each other. On the basis of pure culture studies Descals et al. (1976) pointed out the essentially different conidiogenesis (blastic sympodial in Brachiosphaera vs. retrogressive thallic in Actinosporella) and also subtle differences in conidial morphology (constricted appendage insertion in Brachiosphaera vs. unconstricted in Actinosporella). The placement of Brachiosphaera within Jahnulales (Campbell et al. 2007) confirms its unrelatedness to Actinosporella, which has been connected to the Pezizales by Descals and Webster (1978).

The genus Lemonniera is characterised by tetraradiate conidia with long arms, phialidic conidiogenesis, and formation of minute dark sclerotia in culture. Previously, it has been shown to be polyphyletic and different species of Lemonniera are placed in two distinct clades, namely the Leotiomycetes and the Dothideomycetes (Campbell et al. 2006). In our study we used two isolates of L. pseudofloscula previously sequenced by Campbell et al. (2006). These isolates form a strongly supported monophyletic group within the Pleosporaceae.

More recently, Prihatini et al. (2008) have shown that Speiropsis pedatospora (Tubaki 1958) has phylogenetic affinities within the Jahnulales based on ITS rDNA data. Also, in another recent study by Jones et al. (2009), Sigmoidea prolifera and Pseudosigmoidea cranei, two aquatic hyphomycetes were shown to have phylogenetic affinities with the Phaeotrichaceae, Pleosporales based on SSU data. Sequencing of additional aquatic hyphomycete taxa in the future will continue to shed light on the evolutionary relationships of freshwater aquatic hyphomycetes to different lineages within the Dothideomycetes.

CONCLUSIONS

The freshwater Dothideomycetes occur primarily in the Pleosporomycetidae as opposed to the Dothideomycetidae and appear to have adapted to freshwater habitats numerous times, often through ascospore adaptations, and sometimes, through anamorph conidial adaptations. Ascospores and conidiospores of freshwater fungi are under strong selective pressure to disperse and attach to substrates in freshwater habitats in order for the fungi to complete their life cycles. Thus ascospore features that facilitate dispersal and attachment may not be as reliable as other morphological features such as ascomata and hamathecia in interpreting phylogenetic relationships among freshwater Dothideomycetes. This idea is supported by the presence of similar ascospore modifications such as the presence of gelatinous ascospore sheaths in phylogenetically distant taxa. Further support is the presence of tetraradiate conidia present in widely separated clades.

The presence of morphologically unique singletons within the molecular-based phylogenetic tree of Dothideomycetes suggests that we need to further sample the freshwater ascomycetes to identify close relatives of these taxa.

We expect that future collections from freshwater habitats will modify the phylogeny presented in this paper by increasing the size and support values of existing clades containing freshwater species and in increasing the number of exclusively freshwater clades.

Acknowledgments

We thank Conrad Schoch for his helpful comments on the taxon sampling as well as for his assistance with the RAxML analysis. This work was partially supported by a foundation from the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka (IFO). Participation of L. Marvanová on this study was partly supported by the project (MSM00216222416) of the Czech Ministry of Education Youth and Sports. Financial support from the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health (NSF No. DEB 03-16496, NSF DEB 05-15558, NSF DEB 08-44722 and NIH No. R01GM-60600) helped make this research possible. We are grateful to the curator of IMI for the loan of a specimen. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health.

References

- Baschien C (2003). Development and evaluation of rDNA targeted in situ probes and phylogenetic relationships of freshwater fungi. PhD Thesis. Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin.

- Baschien C, Marvanová L, Szewzyk U (2006). Phylogeny of selected aquatic hyphomycetes based on morphological and molecular data. Nova Hedwigia 83: 311–352. [Google Scholar]

- Belliveau MJ-R, Bärlocher F (2005). Molecular evidence confirms multiple origins of aquatic hyphomycetes. Mycological Research 109: 1407–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Guo XY, Hyde KD (2008). Morphological and molecular characterisation of a new anamorphic genus Cheirosporium, from freshwater in China. Persoonia 20: 53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Hyde KD (2007). Ascorhombispora aquatica gen. et sp. nov. from a freshwater habitat in China, and its phylogenetic placement based on molecular sequence data. Cryptogamie Mycologie 28: 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Ferrer A, Raja HA, Sivichai S, Shearer CA (2007). Phylogenetic relationships among taxa in the Jahnulales inferred from 18S and 28S nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Canadian Journal of Botany 85: 873–882. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Shearer CA, Marvanová (2006). Evolutionary relationships among aquatic anamorphs and teleomorphs: Lemonniera, Margaritispora, and Goniopila. Mycological Research 110: 1025–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descals EC, Nawawi A, Webster J (1976). Developmental studies in Actinospora and three similar aquatic hyphomycetes. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 67: 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Descals EC, Webster J (1978). Miladina lechithina (Pezizales), the ascigerous state of Actinospora megalospora. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 70: 466–472. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Kearse M, Heled J, Moir R, Thierer T, Ashton B, Wilson A, Stones-Harvas S (2006). Geneious v. 2.5, Available from htt://www.geneious.com/.

- Dudka IO (1963). Data on the flora of aquatic fungi of the Ukrainian SSR. II. Aquatic hyphomycetes of Kiev Polessye. Ukraine Botanical Journal 20: 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dudka IO (1985). Ascomycetes, components of freshwater biocoenosis. Ukraine Botanical Journal 42: 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 32: 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer A, Sivichai S, Shearer CA (2007). Megalohypha, a new genus in the Jahnulales from aquatic habitats in the tropics. Mycologia 99: 456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtier N, Gouy M, Gautier C (1996). SEAVIEW and PHYLO_WIN: two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny. Computer Applications in Bioscience 12: 543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessner MO, Gulis V, Kuehn KA, Chauvet E, Suberkropp K (2007). Fungal decomposers of plant litter in aquatic ecosystems. In: The Mycota IV. Environmental and microbial relationships . 2nd ed. (Kubicek CP, Druzhinina IS, eds). Berlin: Springer-Verlag: 301–324.

- Goh TK, Hyde KD (1996). Biodiversity of freshwater fungi. Journal of Industrial Microbiology 17: 328–345. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbett DS, Binder M, Bischoff JF, Blackwell M, Cannon PF, et al. (2007). A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi. Mycological Research 111: 509–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama K, Tanaka K, Raja HA, Miller AN, Shearer CA (2010). A molecular phylogenetic assessment of Massarina ingoldiana sensu lato. Mycologia: In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hyde KD (1992). Australian Freshwater Fungi. V. Bombardia sp., Jahnula australiensis sp. nov., Savoryella aquatica sp. nov. and S. lignicola. Australian Systematic Botany 6: 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde KD, Jones EBG (1989). Observations on ascospore morphology in marine fungi and their attachment to surfaces. Botanica Marina 32: 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde KD, Wong SW (1999). Tropical Australian freshwater fungi. XV. The ascomycete genus Jahnula, with five new species and one new combination. Nova Hedwigia 68: 489–509. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde KD, Wong SW, Aptroot A (2002). Marine and estuarine species of Lophiostoma and Massarina. In: Fungi in marine environments. (Hyde KD, ed.). Fungal Diversity Research Series 7: 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Inderbitzin P, Landvik S, Abdel-Wahab MA, Berbee ML (2001). Aliquandostipitaceae, A new family for two new tropical ascomycetes with unusually wide hyphae and dimorphic ascomata. American Journal of Botany 88: 52–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingold CT (1951). Aquatic ascomycetes: Ceriospora caudae-suis n.sp. and Ophiobolus typhae. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 34: 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold CT (1954). Aquatic ascomycetes: Discomycetes from lakes. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 37: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold CT (1955). Aquatic ascomycetes: further species from the English Lake District. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 38: 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold CT, Chapman B (1952). Aquatic ascomycetes. Loramyces juncicola Weston and L. macrospora n. sp. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 35: 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Jones EBG (2006). Form and function of fungal spore appendages. Mycoscience 47: 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Jones EBG, Zuccaro A, Mitchell J, Nakagiri A, Chatmala I, Pang K-L (2009). Phylogenetic position of freshwater and marine Sigmoidea species: introducing a marine hyphomycete Halosigmoidea gen. nov. (Halosphaeriales). Botanica Marina 52: 349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk PM, Cannon PF, David JC, Stalpers JA (2008). Ainsworth and Bisby's Dictionary of the Fungi. 10th ed. CAB International, Wallingford, U.K.

- Kirschstein V W (1936). Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Ascomyceten und ihrer Nebenformen besonders aus der Mark Brandenburg und dem Bayerischen Walde. Annales Mycologici 34: 180–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kodsueb R, Lumyong S, Ho WI, Hyde KD, McKenzie E, Jeewon R (2007). Morphological and molecular characterization of Aquaticheirospora and phylogenetics of Massarinaceae (Pleosporales). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 155: 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Liew ECY, Aptroot A, Hyde KD (2002). An evaluation of the monophyly of Massarina based on ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycologia 94: 803–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR (2000). MacClade: analysis of phylogeny and character evolution. Sinauer, Sunderland, Mass., U.S.A. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morrison DA (2006). Multiple sequence alignment for phylogenetic purposes. Australian Systematic Botany 19: 479–539. [Google Scholar]

- Pang KL, Abdel-Wahab MA, Sivichai S, El-Sharouney HM, Jones EBG (2002). Jahnulales (Dothideomycetes, Ascomycota): a new order of lignicolous freshwater ascomycetes. Mycological Research 106: 1031–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Pinruan U, Jones EBG, Hyde KD (2002). Aquatic fungi from peat swamp palms: Jahnula appendiculata sp. nov. Sydowia 54: 242–247. [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA (1998). Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 49: 817–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringsheim N (1858). Ueber das Austreten der Sporen von Sphaeria scripi aus ihren Schläuchen. Jahrbuch für Wissenschaftlichen Botanik 1: 189–921. [Google Scholar]

- Prihatini R, Nattawut B, Sivichai S (2008). Phylogenetic evidence that two submerged-habitat fungal species, Speiropsis pedatospora and Xylomyces chlamydosporus belong to the order Jahnulales incertae sedis Dothideomycetes. Microbiology Indonesia 2: 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Promputtha I, Miller AN (2010). Three new species of Acanthostigma (Tubeufiaceae, Pleosporales) from the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Mycologia: In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Raja HA, Carter A, Platt HW, Shearer CA (2008). Freshwater ascomycetes: Jahnula apiospora (Jahnulales, Dothideomycetes), a new species from Prince Edward Island, Canada. Mycoscience 49: 326–328. [Google Scholar]

- Raja HA, Ferrer A, Miller AN, Shearer CA (2010). Freshwater Ascomycetes: Wicklowia aquatica, a new genus and species in the Pleosporales from Florida and Costa Rica. Mycoscience: In press.

- Raja HA, Ferrer A, Shearer CA (2005). Aliquandostipite crystallinus, a new ascomycete species from submerged wood in freshwater habitats. Mycotaxon 91: 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Raja HA, Ferrer A, Shearer CA (2009a). Freshwater ascomycetes: A new genus, Ocala scalariformis gen. et sp. nov, and two new species, Ayria nubispora sp. nov., and Rivulicola cygnea sp. nov. Fungal Diversity 34: 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Raja HA, Schmit JP, Shearer CA (2009b). Latitudinal, habitat and substrate distribution patterns of freshwater ascomycetes in the Florida Peninsula. Biodiversity and Conservation 18: 419–455. [Google Scholar]

- Raja HA, Shearer CA (2006). Jahnula species from North and Central America, including three new species. Mycologia 98: 312–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja HA, Shearer CA (2007). Freshwater ascomycetes: Aliquandostipite minuta (Jahnulales, Dothideomycetes), a new species from Florida. Mycoscience 48: 395–398. [Google Scholar]

- Raja HA, Shearer CA (2008). Freshwater ascomycetes: new and noteworthy species from aquatic habitats in Florida. Mycologia 100: 467–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A (1996). Sequence Alignment Editor. Version 2.0. Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Oxford. Available from http://evolve.zoo..ox.ac.uk/Se-Al/Se-Al.html.

- Rehner SA, Samuels GJ (1995). Molecular systematics of the Hypocreales: a teleomorph gene phylogeny and the status of their anamorphs. Canadian Journal of Botany 73 (Suppl 1): S816–S823. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch CL, Crous PW, Groenewald JZ, Barrés, Boehm EWA, et al. (2009). A class-wide phylogenetic assessment of Dothideomycetes. Studies in Mycology 64: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch CL, Shoemaker RA, Seifert KA, Hambleton S, Spatafora JW, Crous PW (2006). A multigene phylogeny of the Dothideomycetes using four nuclear loci. Mycologia 98: 1041–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer CA (1993). The freshwater ascomycetes. Nova Hedwigia 56: 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer CA (2001). The distribution of freshwater filamentous Ascomycetes. In: Trichomycetes and other fungal groups. (Misra JK, Horn BW, eds). Science Publishers, Plymouth, U.K.: 225–292.

- Shearer CA, Crane JL (1980). Taxonomy of two cleistothecial ascomycetes with papilionaceous ascospores. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 75: 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer CA, Descals E, Volkmann-Kohlmeyer B, Kohlmeyer J, Marvanova L, et al. (2007). Fungal biodiversity in aquatic habitats. Biodiversity and Conservation 16: 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer CA, Fallah PM, Ferrer A, Raja HA, Schmit JP (2009). Freshwater ascomycetes and their anamorphs. URL: www.fungi.life.uiuc.edu (accessed Nov 2009).

- Simonis JL, Raja HA, Shearer CA (2008). Extracellular enzymes and soft rot decay: Are ascomycetes important degraders in fresh water? Fungal Diversity 31: 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22: 2688–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J (2008). A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Systematic Biology 57: 758–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EL, Liu Z, Crous PW, Szabo LJ (1999). Phylogenetic relationships among some cercosporoid anamorphs of Mycosphaerella based on rDNA sequence analysis. Mycological Research 103: 1491–1499. [Google Scholar]

- Suetrong S, Sakayaroj J, Phongpaichit S, Jones EBG (2010). Morphological and molecular characteristics of a poorly known marine ascomycete, Manglicola guatemalensis (Jahnulales: Pezizomycotina; Dothideomycetes, Incertae sedis): new lineage of marine ascomycetes. Mycologia: In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Suetrong S, Schoch CL, Spatafora JW, Kohlmeyer J, Volkmann-Kohlmeyer B, et al. (2009). Molecular systematics of the marine Dothideomycetes. Studies in Mycology 64: 155–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL (2002). PAUP 4.0b10: Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, U.S.A.

- Tanaka K, Hatakeyama S, Harada Y (2005). Three new freshwater ascomycetes from rivers in Akkeshi, Hokkaido, northern Japan. Mycoscience 46: 287–293. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Hosoya T (2008). Lophiostoma sagittiforme sp. nov., a new ascomycete (Pleosporales, Dothideomycetes) from Island Yakushima in Japan. Sydowia 60: 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui CKM, Berbee ML (2006). Phylogenetic relationships and convergence of helicosporous fungi inferred from ribosomal DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 39: 587–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui CKM, Hyde KD (2003). Freshwater mycology. Fungal Diversity Research Series 10: 1–350. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui CKM, Sivichai S, Berbee ML (2006). Molecular systematics of Helicoma, Helicomyces and Helicosporium and their teleomorphs inferred from rDNA sequences. Mycologia 98: 94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui CKM, Sivichai S, Rossman AY, Berbee ML (2007). Tubeufia asiana, the teleomorph of Aquaphila albicans in the Tubeufiaceae, Pleosporales, based on cultural and molecular data. Mycologia 99: 884–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubaki K (1959). Studies on the Japenese Hyphomycetes V. leaf and stem group with discussion of the classification of Hyphomycetes and their perfect stages. Journal of Hattori Botanical Laboratory 20: 142–244. [Google Scholar]

- Vijaykrishna D, Jeewon R, Hyde KD (2006). Molecular taxonomy, origins and evolution of freshwater ascomycetes. Fungal Diversity 23: 367–406. [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R, Hester M (1990). Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. Journal of Bacteriology 172: 4238–4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr H (2004). Spirosphaera cupreorufescens sp. nov., a rare aeroaquatic fungus. Studies in Mycology 50: 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Webster J (1965). The perfect state of Pyricularia aquatica. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 48: 449–452. [Google Scholar]

- Webster J, Descals E (1979). The teleomorphs of waterborne hyphomycetes from fresh water. In: The Whole Fungus. (Kendrick B, ed.). National Museums of Canada and Kananaskis Foundation, Ottawa, 2: 419–451. [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: PCR Protocols: a guide to methods and applications (Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, California, U.S.A.: 315–322.

- Wiens JJ (1998). Combining data sets with different phylogenetic histories. Systematic Biology 47: 568–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby LG, Archer JF (1973). The fungal spora of a freshwater stream and its colonization pattern on wood. Freshwater Biology 3: 219–239. [Google Scholar]

- Wong MKM, Goh T-K, Hodgkiss IJ, Hyde KD, Ranghoo VM, Tsui CKM, Ho W-H, Wong WSW, Yuen T-K (1998). Role of fungi in freshwater ecosystems. Biodiversity and Conservation 7: 1187–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Fournier J, Crous W, Pointing SB, Hyde KD (2009a). Phylogenetic and morphological assessment of two new species of Amniculicola and their allies (Pleosporales). Persoonia 23: 48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Fournier J, Pointing SB, Hyde KD (2008a). Are Melanomma pulvis-pyrius and Trematosphaeria pertusa congeneric? Fungal Diversity 33: 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Jeewon R, Fournier J, Hyde KD (2008b). Multi-gene phylogeny and morphotaxonomy of Amniculicola lignicola: a novel freshwater fungus from France and its relationships to the Pleosporales. Mycological Research 112: 1186–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Schoch CL, Fournier J, Crous PW, Gruyter J de, et al. (2009b). Multi-locus phylogeny of the Pleosporales: a taxonomic, ecological and evolutionary reevaluation. Studies in Mycology 64: 85–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wang HK, Fournier J, Crous PW, Jeewon R, Pointing SB, Hyde KD (2009c). Towards a phylogenetic clarification of Lophiostoma/Massarina and morphological similar genera in the Pleosporales. Fungal Diversity 38: 225–251. [Google Scholar]