Abstract

Background Quitting tobacco or alcohol use has been reported to reduce the head and neck cancer risk in previous studies. However, it is unclear how many years must pass following cessation of these habits before the risk is reduced, and whether the risk ultimately declines to the level of never smokers or never drinkers.

Methods We pooled individual-level data from case–control studies in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Data were available from 13 studies on drinking cessation (9167 cases and 12 593 controls), and from 17 studies on smoking cessation (12 040 cases and 16 884 controls). We estimated the effect of quitting smoking and drinking on the risk of head and neck cancer and its subsites, by calculating odds ratios (ORs) using logistic regression models.

Results Quitting tobacco smoking for 1–4 years resulted in a head and neck cancer risk reduction [OR 0.70, confidence interval (CI) 0.61–0.81 compared with current smoking], with the risk reduction due to smoking cessation after ≥20 years (OR 0.23, CI 0.18–0.31), reaching the level of never smokers. For alcohol use, a beneficial effect on the risk of head and neck cancer was only observed after ≥20 years of quitting (OR 0.60, CI 0.40–0.89 compared with current drinking), reaching the level of never drinkers.

Conclusions Our results support that cessation of tobacco smoking and cessation of alcohol drinking protect against the development of head and neck cancer.

Keywords: Epidemiology, head and neck cancer, cessation, alcohol drinking, tobacco smoking

Introduction

Worldwide, more than half a million cases of head and neck cancer (oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx and larynx) are estimated to occur each year, making it the seventh most common cancer in the world.1 By 2020, growth and ageing of the population will lead to a doubling of these figures to >1 million new cases and over half a million deaths every year. Head and neck cancer is the most common cancer among men aged <55 years worldwide.1 Strong time trends with increasing incidence and mortality rates have been observed in Central and Eastern Europe.2–4 In Western countries, the main risk factors for head and neck cancer are alcohol drinking and tobacco smoking, which together account for ∼75% of the disease.5

Quitting tobacco smoking has been reported to reduce the risk of head and neck cancer in previous studies. At least five cohort studies and 40 case–control studies suggested a reduction of head and neck cancer risk after the cessation of tobacco smoking to the order of 16–85%.6–14 The risk of head and neck cancer was shown to decrease with time since stopping smoking, but only eight of these studies evaluated quitting smoking for ≥20 years. Of these eight studies, three studies of laryngeal cancer reported that individuals who quit for ≥20 years still have elevated risks of laryngeal cancer compared with never smokers.15–17 The five other studies on oral and pharyngeal cancer risk reported that the risk was similar to never smokers after quitting for ≥20 years.10,18–21

In contrast to the numerous studies on smoking cessation, there have been fewer studies of head and neck cancer and quitting alcohol drinking. The results of seven case–control studies were inconsistent, with some showing increased risks or unchanged risks,7–9,16,21–23 and others showing decreased risks after quitting alcohol drinking compared with current drinkers. A risk reduction of oral cavity and pharyngeal cancers after cessation of drinking was observed in two studies,7,9 but no association was observed in two other studies.8,21 A decline in risk of laryngeal cancer was found after stopping drinking compared with current drinkers in an Uruguayan investigation23 and in the multicentre case–control study in Italy and Switzerland.16 On the other hand, in a study from the same area, Franceschi et al.22 reported a higher risk of oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer 7–10 years after cessation of drinking compared with current drinkers, which did not decrease even after more years of quitting.

To evaluate the effect of cessation of alcohol drinking and tobacco smoking, we pooled data from 18 case–control studies from around the world within the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology (INHANCE) consortium. Our aim was to estimate the number of years of quitting required to observe a reduced risk and whether the risk declines to the level of never smokers and never drinkers. In addition, we were interested in whether the risk reversal differs by head and neck cancer subsite, and by frequency of tobacco or alcohol use before quitting. A precise estimation of the beneficial effect of cessation of alcohol drinking and tobacco smoking has important public health implications since quitting these habits can be encouraged by public health intervention.

Research design and methods

A detailed description of the INHANCE consortium with characteristics of the individual studies and the pooling methods for the first data version 1.0 including 16 case–control studies was provided previously.24 Two new studies were added (Boston and Rome) for data version 1.1. The current analysis included the 18 studies with 12 282 head and neck cancer case subjects and 17 189 control subjects. Case and control subjects with missing data on age, sex or race/ethnicity, and case subjects with missing information on the site of origin of their cancer were excluded (62 case subjects and 103 control subjects). Data were available in 13 case–control studies on the cessation of alcohol (wine, beer, liquor or aperitif) drinking (9167 cases and 12 593 controls), and in 17 case–control studies on the cessation of tobacco (cigarette, cigar or pipe) smoking (12 040 cases and 16 884 controls).

Most of the INHANCE data came from hospital-based case–control studies (Milan, Aviano, France, Italy, Switzerland, Central Europe, Rome, New York, Iowa, North Carolina, Tampa, Houston, Latin America, international multicentre studies), in which the control subjects were frequency matched to the case subjects on age, sex and additional factors (such as study centre, hospital and race/ethnicity). The other studies were population-based case–control studies (Seattle, Los Angeles, Puerto Rico, Boston). The Los Angeles study individually matched the control subjects to case subjects on age decade, gender and neighbourhood, though in this analysis the matching was broken. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in all studies except for the Iowa study, in which subjects completed self-administered questionnaires.

Written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects, and the investigations were approved by the institutional review board at each study centre. Questionnaires were collected from all the individual studies to assess the comparability of the collected data and of the wording of interview questions among the studies. Data from individual studies were received at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) with personal identifiers removed. Each data item was checked for inconsistent or missing values. Queries were sent to the investigators to resolve inconsistencies.

Case subjects were included in this study if their tumour had been classified by the original study as an invasive tumour of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, oral cavity or pharynx not otherwise specified (NOS), larynx or head and neck cancer unspecified according to the International Classification of Diseases—Oncology, Version 2 (ICD-O-2) or the International Classification of Diseases, 9th or 10th Revision (ICD 9 or ICD 10, respectively).25–27 Subjects with salivary gland cancers (ICD-O-2 topography codes C07–C08) and external lip cancers (ICD-O-2 topography codes C00.0–C00.2) were excluded from our analysis because the etiologic pattern of these cancers differs from that of other head and neck cancers.28 In our data, there were 3390 case subjects with oral cavity cancer, 3875 with pharyngeal cancer (oropharyngeal or hypopharyngeal), 969 with oral cavity or pharynx not otherwise specified, 2821 with laryngeal cancer and 306 with unspecified head and neck cancers. Some studies (in France, North Carolina, Tampa and Houston) restricted eligibility to case subjects with squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). For other studies that provided the ICD-O-2 histological coding for each tumour, we used the codes to identify case subjects with SCC. Of the 7709 head and neck cancer case subjects for whom histological information was available, 7475 (97.0%) had SCC.

The questions about tobacco and alcohol use on study questionnaires were conceptually similar across studies, but because the exact wording differed, they were examined carefully for comparability before variables were created for the data analyses. In the alcohol section of the study questionnaires, subjects were asked if they had been alcohol drinkers; for those who responded that they were, variables on frequency, duration and cumulative consumption of drinking overall, and by types of alcohol beverages (beer, wine and hard liquor) were calculated. Age at stopping alcohol drinking was available from 13 studies. Former drinkers were defined as subjects who had quit drinking the following alcoholic beverages: wine, beer, liquor and aperitifs. For quitting alcohol drinking, we classified subjects who had stopped drinking for >1 year as former drinkers. The number of years that former drinkers had quit drinking was determined from age at reference date (interview or diagnosis date) and age at which he/she had stopped drinking.

Each study subject was asked whether he/she had ever been a cigarette, cigar or pipe smoker. Variables on the frequency, duration and pack-years (PYs) of tobacco smoking were available in all studies. Age at stopping tobacco smoking was available from 17 studies. We classified former smokers as individuals who had quit smoking these tobacco products: cigarette, cigar and pipe. For quitting tobacco smoking, we defined subjects who had stopped smoking for >1 year as former smokers. Time since cessation of tobacco smoking was calculated from age at reference date (interview or diagnosis date) and age at which the individual stopped smoking any type of tobacco (cigarette, cigar, pipe).

Information about snuff use and chewing habits was collected by the Puerto Rico study, the international multicentre studies and all studies in North America. Snuff use and chewing are not common behaviours in Europe or Latin America, except in specific populations (e.g. Norway and Sweden), which were not included in the pooled dataset. For the Indian component of the international multicentre study, information on betel quid and areca nut chewing was collected. Frequency and duration variables for chewing and snuff use habits were pooled across relevant studies. For this study, never users of tobacco were defined as individuals who had not used cigarettes, cigars, pipes, snuff or chewing products during their lifetimes.

Other potential confounders considered included involuntary smoking and family history of head and neck cancer. Data on involuntary smoking exposure at home and at work (never/ever), which were available in six studies, were pooled (Central Europe, Tampa, Los Angeles, Houston, Puerto Rico and Latin America studies). A variable on the number of first-degree relatives who had head and neck cancer was also pooled across the 12 studies that had assessed this information (Milan, Aviano, Italy multicentre, Switzerland, Central Europe, North Carolina, Tampa, Los Angeles, Houston, Puerto Rico, Latin America and international multicentre studies).

Statistical methods

We estimated the effect of quitting tobacco smoking or alcohol drinking on the risk of head and neck cancer, by calculating odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using unconditional logistic regression models for each case–control study. The adjusted models included sex, age (categories shown in Table 1), education level (categories shown), race/ethnicity (categories shown) and study centre (categories shown), tobacco PYs (as a continuous variable) and frequency of alcohol drinking (as a continuous variable). In addition, we adjusted for body mass using the body mass index (BMI) at age 30 years (<18.5 kg/m2, 18.5 to <25 kg/m2, 25 to <30 kg/m2, ≥30 kg/m2), status of involuntary tobacco smoking (never, ever) or status of family history of head and neck cancer (yes/no) in selected models. To calculate summary estimates of associations, the study-specific estimates were included in a two-stage random-effects logistic regression model using the maximum likelihood estimator, which allows for unexplained sources of heterogeneity among studies. Pooled ORs were also estimated with a fixed-effects logistic regression model that adjusted for age, sex, education level, race/ethnicity and study centre. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of head and neck cancer case and control subjects

|

Analysis of alcohol drinking |

Analysis of tobacco smoking |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases |

Controls |

Cases |

Controls |

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 9167 | 12 593 | 12 040 | 16 884 | ||||

| Study | ||||||||

| Europe | ||||||||

| Milan, Italy | – | – | 416 | 3.5 | 1531 | 9.1 | ||

| Aviano, Italy | – | – | 482 | 4.0 | 855 | 5.1 | ||

| France | 323 | 3.5 | 234 | 1.9 | 323 | 2.7 | 234 | 1.4 |

| Italy | 1058 | 11.5 | 2579 | 20.5 | 1058 | 8.8 | 2579 | 15.3 |

| Switzerland | 516 | 5.6 | 883 | 7.0 | 516 | 4.3 | 883 | 5.2 |

| Central Europe | – | – | 762 | 6.3 | 907 | 5.4 | ||

| Rome, Italy | – | – | 275 | 2.3 | 294 | 1.7 | ||

| North America | ||||||||

| New York city, NY | – | – | 1118 | 9.3 | 906 | 5.4 | ||

| Seattle, WA | 407 | 4.4 | 607 | 4.8 | 407 | 3.4 | 607 | 3.6 |

| Iowa, IA | 546 | 6.0 | 759 | 6.0 | 546 | 4.5 | 759 | 4.5 |

| North Carolina, NC | 180 | 2.0 | 202 | 1.6 | – | – | ||

| Tampa, FL | 207 | 2.3 | 897 | 7.1 | 207 | 1.7 | 897 | 5.3 |

| Los Angeles, CA | 417 | 4.5 | 1005 | 8.0 | 417 | 3.5 | 1005 | 6.0 |

| Houston, TX | 829 | 9.0 | 865 | 6.9 | 829 | 6.9 | 865 | 5.1 |

| Boston, MA | 584 | 6.4 | 659 | 5.2 | 584 | 4.9 | 659 | 3.9 |

| Latin/Central America | ||||||||

| Puerto Rico | 350 | 3.8 | 521 | 4.1 | 350 | 2.9 | 521 | 3.1 |

| Latin America | 2191 | 23.9 | 1706 | 13.5 | 2191 | 18.2 | 1706 | 10.1 |

| International | ||||||||

| multicentre | 1559 | 17.0 | 1676 | 13.3 | 1559 | 12.9 | 1676 | 9.9 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| <40 | 376 | 4.1 | 816 | 6.5 | 472 | 3.9 | 1114 | 6.6 |

| 40–44 | 545 | 5.9 | 964 | 7.7 | 690 | 5.7 | 1267 | 7.5 |

| 45–49 | 1050 | 11.5 | 1439 | 11.4 | 1326 | 11.0 | 1874 | 11.1 |

| 50–54 | 1409 | 15.4 | 1999 | 15.9 | 1850 | 15.4 | 2606 | 15.4 |

| 55–59 | 1724 | 18.8 | 2154 | 17.1 | 2247 | 18.7 | 2916 | 17.3 |

| 60–64 | 1471 | 16.0 | 1931 | 15.3 | 2053 | 17.1 | 2621 | 15.5 |

| 65–69 | 1197 | 13.1 | 1551 | 12.3 | 1643 | 13.6 | 2145 | 12.7 |

| 70–74 | 821 | 9.0 | 1115 | 8.9 | 1070 | 8.9 | 1533 | 9.1 |

| ≥75 | 574 | 6.3 | 624 | 5.0 | 689 | 5.7 | 808 | 4.8 |

| Race/Ethnicitya | ||||||||

| White | 5661 | 61.8 | 9175 | 72.9 | 8488 | 70.5 | 13 418 | 79.5 |

| Black | 391 | 4.3 | 513 | 4.1 | 432 | 3.6 | 560 | 3.3 |

| Hispanic | 158 | 1.7 | 349 | 2.8 | 164 | 1.4 | 349 | 2.1 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 625 | 6.8 | 666 | 5.3 | 629 | 5.2 | 667 | 4.0 |

| Latin American | 2191 | 23.9 | 1706 | 13.5 | 2191 | 18.2 | 1706 | 10.1 |

| Others | 141 | 1.5 | 184 | 1.5 | 136 | 1.1 | 184 | 1.1 |

| P-value for chi-square heterogeneity test | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 2023 | 22.1 | 3759 | 29.8 | 2544 | 21.1 | 4817 | 28.5 |

| Male | 7144 | 77.9 | 8834 | 70.2 | 9496 | 78.9 | 12 067 | 71.5 |

| Education | ||||||||

| No formal education | 437 | 4.8 | 285 | 2.3 | 448 | 3.7 | 307 | 1.8 |

| Less than junior high school | 3642 | 39.7 | 4478 | 35.6 | 4561 | 37.9 | 6417 | 38.0 |

| Some high school | 1197 | 13.1 | 1420 | 11.3 | 1563 | 13.0 | 1891 | 11.2 |

| High school graduate | 1153 | 12.6 | 1657 | 13.2 | 1739 | 14.4 | 2141 | 12.7 |

| Vocational school, some college | 1077 | 11.7 | 2020 | 16.0 | 1355 | 11.3 | 2511 | 14.9 |

| College graduate/ postgraduate | 967 | 10.5 | 2269 | 18.0 | 1394 | 11.6 | 2836 | 16.8 |

| Missing | 694 | 7.6 | 464 | 3.7 | 980 | 8.1 | 781 | 4.6 |

| P-value for chi-square heterogeneity test | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

aInformation on ethnicity were not collected in the Central Europe, France, Rome and Latin America studies. In the Central Europe, France and Rome studies, all subjects were classified as non-Hispanic White, since the large majority of these populations are expected to be White. In the Latin American study, we categorized subjects as ‘Latin American’. We adjusted for study centre in all logistic regression models as a proxy variable for race/ethnicity since each centre has an expected predominant ethnic group distribution.

For subjects with a missing education level [694 case subjects (7.6%) and 464 control subjects (3.7%) for analyses of cessation of alcohol drinking, 980 case subjects (8.1%) and 781 control subjects (4.6%) for analyses of cessation of tobacco smoking], we applied a multiple imputation with a logistic regression method for a single missing data item. We assumed that the education data were missing at random; that is, whether or not education level was missing did not depend on the unobserved or missing values of education.29 We used a logistic regression model to predict education level for each of the geographic regions separately using age, sex, race/ethnicity, study centre and case–control status as the covariates.30 The logistic regression results to assess summary estimates for cessation of tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking for five imputations were combined with the PROC MIANALYZE procedure.31

We tested for heterogeneity among the study ORs by using a likelihood ratio test comparing a model including the product terms between each study (other than the reference study) with the variable of interest and a model without the product terms. We report the random-effects estimates, because heterogeneity was detected in almost all models. We confirmed that the magnitude of the effect from the two-stage random-effects model and from the fixed-effect logistic regression model were comparable with each other. We also conducted influence analysis, in which each study was excluded one at a time to assure that the association and the magnitude of the overall summary estimate was not dependent on any one study.

Analyses were stratified by cancer site (oral cavity, oro-/hypopharynx and larynx), age (<44, 45–54, 55–64, ≥65 years), sex, education level (categories shown in Table 1), race/ethnicity (categories shown), geographic region (Europe, North America, South/Central America, others), source of control subjects (hospital-based vs population-based), study year (before 2000, 2000 or later) and study sample size (500 cases or less, more than 500 cases). In addition, we stratified the results for quitting tobacco smoking by frequency of smoking (categories shown in Table 3), duration of smoking and status of alcohol drinking. For cessation of alcohol drinking, we additionally stratified the results by frequency of drinking (categories shown), duration of drinking and status of tobacco smoking. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Table 3.

Cessation of alcohol drinking or tobacco smoking and the risk of head and neck cancer subsites stratified by frequencya,b

|

Oral cavity |

Oropharynx/Hypopharynx |

Larynx |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI | |

| Cessation of alcohol drinking | ||||||||||||

| <1 drinks/day and never drinkers | ||||||||||||

| Current drinkers | 256 | 2250 | 1.00 | Ref.c,d | 338 | 2444 | 1.00 | Ref.c,d,e,f | 207 | 2138 | 1.00 | Ref.c,g,h |

| >1–4 years | 30 | 144 | 1.51 | (0.80–2.87) | 29 | 144 | 2.02 | (1.07–3.80) | 23 | 87 | 2.38 | (1.11–5.11) |

| 5–9 years | 22 | 204 | 1.06 | (0.39–2.88) | 28 | 205 | 1.44 | (0.65–3.16) | 18 | 97 | 1.47 | (0.70–3.11) |

| 10–19 years | 40 | 307 | 0.80 | (0.37–1.75) | 67 | 309 | 1.49 | (0.96–2.34) | 33 | 181 | 1.26 | (0.73–2.19) |

| ≥20 years | 57 | 338 | 0.98 | (0.54–1.77) | 60 | 338 | 1.16 | (0.65–2.05) | 34 | 200 | 0.99 | (0.56–1.74) |

| Never drinkers | 727 | 3238 | 0.86 | (0.39–1.89) | 406 | 3693 | 0.97 | (0.59–1.58) | 243 | 2668 | 0.86 | (0.48–1.55) |

| Missing | 0 | 9 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 9 | ||||||

| P for heterogeneityi | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 | |||||||||

| 1–2 drinks/day and never drinkers | ||||||||||||

| Current drinkers | 234 | 1539 | 1.00 | Ref.c,d,e | 355 | 1808 | 1.00 | Ref.e | 213 | 1479 | 1.00 | Ref.c,e,g,h |

| >1–4 years | 24 | 149 | 0.67 | (0.33–1.35) | 38 | 152 | 1.09 | (0.65–1.82) | 37 | 102 | 1.81 | (1.01–3.24) |

| 5–9 years | 36 | 154 | 1.22 | (0.43–3.43) | 33 | 156 | 1.09 | (0.55–2.16) | 15 | 94 | 0.91 | (0.39–2.11) |

| 10–19 years | 30 | 205 | 0.34 | (0.15–0.80) | 55 | 205 | 1.06 | (0.67–1.68) | 33 | 136 | 1.00 | (0.53–1.89) |

| ≥20 years | 29 | 186 | 0.59 | (0.22–1.57) | 45 | 186 | 0.80 | (0.47–1.37) | 28 | 126 | 0.78 | (0.39–1.55) |

| Never drinkers | 717 | 3144 | 0.58 | (0.26–1.28) | 400 | 3599 | 0.49 | (0.30–0.81) | 233 | 2574 | 0.67 | (0.28–1.57) |

| Missing | 0 | 11 | 3 | 11 | 0 | 10 | ||||||

| P for heterogeneityi | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| ≥3 drinks/day and never drinkers | ||||||||||||

| Current drinkers | 589 | 1554 | 1.00 | Ref.c,e | 926 | 1554 | 1.00 | Ref.c,e | 751 | 1395 | 1.00 | Ref.g,h |

| >1–4 years | 77 | 206 | 0.79 | (0.54–1.14) | 141 | 206 | 1.05 | (0.69–1.59) | 85 | 164 | 0.70 | (0.34–1.44) |

| 5–9 years | 90 | 207 | 0.85 | (0.51–1.41) | 174 | 207 | 1.12 | (0.60–2.08) | 80 | 164 | 0.91 | (0.50–1.66) |

| 10–19 years | 102 | 279 | 0.82 | (0.50–1.34) | 213 | 279 | 1.15 | (0.73–1.81) | 132 | 234 | 0.78 | (0.42–1.44) |

| ≥20 years | 69 | 232 | 0.43 | (0.28–0.67) | 115 | 232 | 0.77 | (0.45–1.30) | 94 | 184 | 0.28 | (0.09–0.86) |

| Never drinkers | 727 | 3580 | 0.19 | (0.09–0.39) | 397 | 3580 | 0.19 | (0.10–0.37) | 249 | 2687 | 0.26 | (0.12–0.57) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| P trend | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| P for heterogeneityi | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| Cessation of tobacco smoking | ||||||||||||

| <5 cigarettes/day and never smokers | ||||||||||||

| Current smokers | 347 | 426 | 1.00 | Ref.j,k | 111 | 437 | 1.00 | Ref.c,d,j,l | 40 | 268 | 1.00 | Ref.c,d,g,h,k,l,m,n,o |

| >1–4 years | 17 | 38 | 3.94 | (1.15–13.53) | 5 | 42 | 2.41 | (0.50–11.55) | 5 | 25 | 6.69 | (0.69–65.14) |

| 5–9 years | 6 | 54 | 0.69 | (0.12–3.85) | 13 | 52 | 1.75 | (0.55–5.58) | 5 | 38 | 0.59 | (0.10–3.53) |

| 10–19 years | 14 | 128 | 0.47 | (0.18–1.19) | 16 | 133 | 0.61 | (0.18–2.04) | 3 | 77 | 0.62 | (0.10–4.07) |

| ≥20 years | 19 | 261 | 0.29 | (0.11–0.75) | 31 | 269 | 0.50 | (0.25–1.01) | 6 | 163 | 0.29 | (0.05–1.69) |

| Never smokers | 457 | 5336 | 0.19 | (0.08–0.47) | 429 | 5023 | 0.35 | (0.19–0.64) | 102 | 3320 | 0.19 | (0.09–0.41) |

| Missing | 53 | 175 | 16 | 171 | 6 | 85 | ||||||

| P heterogeneityi | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.23 | |||||||||

| 5–9 cigarettes/day and never smokers | ||||||||||||

| Current smokers | 352 | 332 | 1.00 | Ref.c,d,f,h,j,k,l,n,o,p | 196 | 709 | 1.00 | Ref | 93 | 430 | 1.00 | Ref.c,d,f,g,h,m,o,p |

| >1–4 years | 17 | 35 | 1.24 | (0.42–3.65) | 22 | 69 | 1.83 | (0.84–3.99) | 10 | 49 | 1.04 | (0.34–3.22) |

| 5–9 years | 10 | 38 | 0.82 | (0.24–2.87) | 16 | 83 | 1.62 | (0.71–3.68) | 14 | 58 | 1.72 | (1.62–1.82) |

| 10–19 years | 8 | 93 | 0.26 | (0.08–0.84) | 18 | 175 | 0.51 | (0.20–1.32) | 14 | 123 | 0.39 | (0.37–0.42) |

| ≥20 years | 17 | 157 | 0.28 | (0.10–0.81) | 38 | 310 | 0.42 | (0.19–0.91) | 19 | 215 | 0.40 | (0.39–0.42) |

| Never smokers | 263 | 2399 | 0.16 | (0.07–0.36) | 467 | 6186 | 0.23 | (0.13–0.42) | 107 | 3507 | 0.20 | (0.19–0.20) |

| Missing | 47 | 122 | 21 | 194 | 9 | 96 | ||||||

| P for heterogeneityi | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| ≥10 cigarettes/day and never smokers | ||||||||||||

| Current smokers | 2102 | 4288 | 1.00 | Ref. | 2378 | 4288 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1987 | 3367 | 1.00 | Ref.g,h,m |

| >1–4 years | 133 | 513 | 0.61 | (0.48–0.79) | 185 | 513 | 0.70 | (0.53–0.94) | 170 | 421 | 0.65 | (0.51–0.82) |

| 5–9 years | 116 | 704 | 0.42 | (0.3–0.57) | 176 | 704 | 0.47 | (0.36–0.61) | 167 | 550 | 0.51 | (0.41–0.64) |

| 10–19 years | 130 | 1326 | 0.23 | (0.18–0.30) | 246 | 1326 | 0.34 | (0.25–0.45) | 186 | 1046 | 0.32 | (0.23–0.43) |

| ≥20 years | 115 | 1469 | 0.15 | (0.11–0.20) | 228 | 1469 | 0.23 | (0.16–0.35) | 115 | 1172 | 0.15 | (0.11–0.19) |

| Never smokers | 463 | 6186 | 0.13 | (0.09–0.19) | 467 | 6186 | 0.17 | (0.11–0.27) | 130 | 4815 | 0.06 | (0.04–0.08) |

| Missing | 182 | 437 | 147 | 437 | 67 | 185 | ||||||

| P trend | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| P for heterogeneityi | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 | |||||||||

aCa = Cases; Co = Controls.

bAdjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, study centre, education level, additionally alcohol drinking are adjusted for PYs and tobacco smoking for drinking frequency.

cDoes not include the France study.

dDoes not include the Switzerland study.

eDoes not include the North Carolina study.

fDoes not include the Italy study.

gDoes not include the international multicentre study.

hDoes not include the Seattle and Puerto Rico studies.

iTwo-sided test for heterogeneity among studies.

jDoes not include the Milan study.

kDoes not include the Aviano study.

lDoes not include the Rome study.

mDoes not include the New York study.

nDoes not include the Iowa study.

oDoes not include the Tampa study.

pDoes not include the Houston study.

Results

The distributions of case and control subjects for selected characteristics are shown in Table 1. Subjects with head and neck cancer were slightly less educated, compared with control subjects. Overall, 26.0% of case subjects and 20.1% of control subjects were former alcohol drinkers, and 19.6% of case subjects and 29.1% of control subjects were former tobacco smokers.

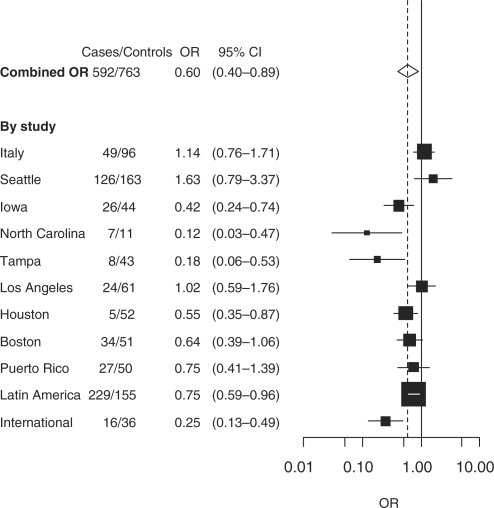

Cessation of alcohol drinking

Quitting alcohol drinking was associated with a 40% decreased risk of head and neck cancer (OR 0.60; 95% CI 0.40–0.89) after ≥20 years of cessation compared with current drinkers (Table 2). The beneficial effect of quitting alcohol drinking ≥20 years compared with current drinkers was estimated in eight studies, of which six showed an association, whereas three studies reported no association between drinking cessation and the reversal of head and neck cancer risk (Figure 1). The risk reversal of head and neck cancer after quitting alcohol drinking for ≥20 years was observed across all subsites of head and neck cancer, but an inverse trend with the years of quitting alcohol was apparent only for oral cavity cancer (Table 2).

Table 2.

|

Head and neck |

Oral cavity |

Oropharynx/Hypopharynx |

Larynx |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI | |

| Drinking status | ||||||||||||||||

| Current drinkers | 4668 | 5915 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1131 | 5715 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1703 | 5915 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1103 | 4961 | 1.00 | Ref.c |

| Former drinkers | 2521 | 2646 | 0.85 | (0.63–1.14) | 610 | 2644 | 0.60 | (0.43–0.84) | 1014 | 2646 | 0.98 | (0.69–1.39) | 609 | 1778 | 0.79 | (0.57–1.08) |

| Never drinkers | 1602 | 3693 | 0.73 | (0.51–1.06) | 737 | 3674 | 0.64 | (0.36–1.15) | 406 | 3693 | 0.64 | (0.41–1.00) | 243 | 2668 | 0.67 | (0.42–1.07) |

| Missing | 376 | 339 | 137 | 326 | 96 | 339 | 51 | 148 | ||||||||

| P for heterogeneityd | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Cessation of alcohol drinking | ||||||||||||||||

| Current drinkers | 4668 | 5915 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1131 | 5715 | 1.00 | Ref.e | 1703 | 5915 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1103 | 4961 | 1.00 | Ref.c,e |

| >1–4 years | 564 | 505 | 0.99 | (0.69–1.43) | 132 | 504 | 0.81 | (0.61–1.07) | 213 | 505 | 1.04 | (0.73–1.48) | 141 | 353 | 1.16 | (0.82–1.63) |

| 5–9 years | 575 | 576 | 0.90 | (0.62–1.30) | 149 | 576 | 0.77 | (0.52–1.15) | 240 | 576 | 0.95 | (0.61–1.49) | 112 | 358 | 0.88 | (0.65–1.19) |

| 10–19 years | 790 | 802 | 0.94 | (0.75–1.18) | 174 | 801 | 0.66 | (0.47–0.92) | 340 | 802 | 1.15 | (0.92–1.43) | 199 | 553 | 0.93 | (0.64–1.36) |

| ≥20 years | 591 | 762 | 0.60 | (0.40–0.89) | 155 | 763 | 0.45 | (0.26–0.78) | 221 | 763 | 0.74 | (0.50–1.09) | 157 | 514 | 0.69 | (0.52–0.91) |

| Never drinkers | 1602 | 3693 | 0.74 | (0.51–1.06) | 737 | 3674 | 0.65 | (0.36–1.16) | 406 | 3693 | 0.65 | (0.42–1.02) | 243 | 2668 | 0.69 | (0.43–1.09) |

| Missing | 376 | 339 | 137 | 326 | 96 | 339 | 51 | 148 | ||||||||

| P trend | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.28 | ||||||||||||

| P for heterogeneityd | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Smoking statusc | ||||||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 7710 | 5183 | 1.00 | Ref.e | 2256 | 5183 | 1.00 | Ref.e | 2565 | 5183 | 1.00 | Ref.e | 2138 | 4127 | 1.00 | Ref.c,e,f |

| Former smoker | 2533 | 5009 | 0.39 | (0.33–0.46) | 583 | 5009 | 0.30 | (0.26–0.34) | 957 | 5009 | 0.41 | (0.32–0.53) | 720 | 4002 | 0.38 | (0.31–0.47) |

| Never smoker | 1271 | 6185 | 0.25 | (0.17–0.36) | 463 | 6185 | 0.20 | (0.14–0.29) | 467 | 6185 | 0.26 | (0.16–0.44) | 130 | 4814 | 0.12 | (0.08–0.16) |

| Missing | 526 | 506 | 202 | 506 | 162 | 506 | 79 | 230 | ||||||||

| P for heterogeneityd | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||||||||

| Cessation of tobacco smoking | ||||||||||||||||

| Current smokers | 7710 | 5183 | 1.00 | Ref. | 2256 | 5183 | 1.00 | Ref. | 2565 | 5183 | 1.00 | Ref. | 2138 | 4127 | 1.00 | Ref.c,f |

| >1–4 years | 624 | 620 | 0.70 | (0.61–0.81) | 156 | 620 | 0.65 | (0.52–0.80) | 206 | 620 | 0.72 | (0.52–1.00) | 186 | 510 | 0.70 | (0.56–0.87) |

| 5–9 years | 576 | 836 | 0.48 | (0.40–0.58) | 129 | 836 | 0.43 | (0.32–0.58) | 198 | 836 | 0.51 | (0.38–0.67) | 188 | 660 | 0.57 | (0.46–0.71) |

| 10–19 years | 686 | 1582 | 0.34 | (0.28–0.40) | 144 | 1582 | 0.25 | (0.21–0.31) | 272 | 1582 | 0.36 | (0.27–0.49) | 203 | 1253 | 0.36 | (0.27–0.47) |

| ≥20 years | 647 | 1971 | 0.23 | (0.18–0.31) | 154 | 1971 | 0.19 | (0.15–0.24) | 281 | 1971 | 0.29 | (0.19–0.43) | 143 | 1579 | 0.19 | (0.15–0.25) |

| Never smokers | 1271 | 6186 | 0.23 | (0.16–0.34) | 463 | 6186 | 0.19 | (0.14–0.27) | 467 | 6186 | 0.25 | (0.15–0.42) | 130 | 4815 | 0.11 | (0.08–0.16) |

| Missing | 526 | 506 | 202 | 506 | 162 | 506 | 79 | 230 | ||||||||

| P trend | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||||||||

| P for heterogeneityd | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||||||

aCa = cases; Co = controls.

bAdjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, study centre, education level, tobacco PYs and drinking frequency.

cDoes not include the Seattle, Puerto Rico and international multicentre studies.

dTwo-sided test for heterogeneity among studies.

eDoes not include the France study.

fDoes not include the New York study.

Figure 1.

Cessation of drinking ≥20 years and head and neck cancer risk compared with current drinking

Among subjects who drank one or more drinks per day, the head and neck cancer ORs for quitting drinking were 0.88 (95% CI 0.64–1.23) for 1–4 years, 0.81 (95% CI 0.54–1.22) for quitting drinking 5–9 years, 0.82 (95% CI 0.61–1.10) for quitting drinking 10–19 years, 0.44 (95% CI 0.25–0.77) for quitting drinking ≥20 years and 0.55 (95% CI 0.36–0.84) for never drinking compared with current drinking (data not shown). When results were stratified by alcohol drinking frequency, we observed an increased risk among low frequency drinkers who quit drinking 1–4 years ago for pharyngeal and laryngeal cancer (Table 3). The ORs after quitting drinking ≥20 years appeared to decrease with increasing frequency of alcohol drinking for head and neck cancer overall (<1 drink/day: OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.72–1.39; 1–2 drinks/day: OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.52–1.12; ≥3 drinks/day: OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.31–0.94; data not shown), as well as for oral cavity cancer and laryngeal cancer. The risk of pharyngeal cancer after quitting drinking ≥20 years decreased only slightly with increasing frequency. Such trends were not observed with increasing categories for duration of alcohol drinking (results not shown).

An inverse relationship between quitting drinking and the risk of oral cavity cancer and laryngeal cancer was detected among current smokers, but not among former or never smokers (Table 4). For pharyngeal cancer, we observed a less pronounced risk reduction after cessation of alcohol drinking than for the other head and neck cancer subsites. These results were essentially unchanged after stratification by PYs of tobacco smoking and frequency of alcohol drinking.

Table 4.

Cessation of alcohol drinking or tobacco smoking and the risk of head and neck cancer by status of the other main risk factora,b,c

|

Cessation of tobacco smoking |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current smokers |

>1–4 years former smokers |

5–19 years former smokers |

≥20 years former smokers |

Never smokers |

||||||||||||||||

| Drinking cessation | Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca | Co | OR | 95% CI |

| Head and Neck | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Current drinkers | 2619 | 1556 | 1.00 | Ref. | 168 | 167 | 0.75 | (0.49–1.14) | 409 | 810 | 0.40 | (0.33–0.48) | 249 | 696 | 0.27 | (0.17–0.42) | 288 | 1554 | 0.21 | (0.11–0.41) |

| >1–4 years former drinkers | 295 | 132 | 0.94 | (0.53–1.65) | 94 | 55 | 0.74 | (0.47–1.17) | 53 | 67 | 0.44 | (0.27–0.72) | 25 | 52 | 0.29 | (0.09–0.92) | 21 | 96 | 0.24 | (0.09–0.68) |

| 5–19 years former drinkers | 648 | 294 | 0.90 | (0.61–1.33) | 62 | 58 | 0.42 | (0.26–0.7) | 240 | 260 | 0.43 | (0.27–0.68) | 82 | 164 | 0.31 | (0.17–0.55) | 48 | 216 | 0.17 | (0.07–0.46) |

| ≥20 years former drinkers | 245 | 144 | 0.53 | (0.32–0.88) | 23 | 23 | 0.55 | (0.24–1.26) | 72 | 98 | 0.32 | (0.21–0.49) | 73 | 166 | 0.25 | (0.13–0.48) | 37 | 114 | 0.27 | (0.11–0.68) |

| Never drinkers | 737 | 538 | 0.74 | (0.36–1.52) | 54 | 56 | 0.57 | (0.26–1.28) | 77 | 198 | 0.28 | (0.13–0.61) | 91 | 237 | 0.26 | (0.11–0.59) | 503 | 1720 | 0.26 | (0.12–0.56) |

| Total | 7213 | 9471 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Missing | 321 | 299 | ||||||||||||||||||

| P for heterogeneityc | <0.01 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Oral cavity | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Current drinkers | 708 | 1556 | 1.00 | Ref. | 39 | 167 | 0.66 | (0.4–1.09) | 92 | 810 | 0.33 | (0.24–0.46) | 52 | 696 | 0.18 | (0.11–0.27) | 73 | 1554 | 0.17 | (0.12–0.24) |

| >1–4 years former drinkers | 61 | 132 | 0.65 | (0.42–1.01) | 25 | 55 | 0.57 | (0.29–1.14) | 11 | 67 | 0.94 | (0.38–2.3) | 5 | 52 | 0.45 | (0.12–1.72) | 4 | 96 | 0.34 | (0.09–1.32) |

| 5–19 years former drinkers | 133 | 294 | 0.72 | (0.52–1.01) | 12 | 58 | 0.35 | (0.11–1.14) | 38 | 260 | 0.24 | (0.11–0.52) | 16 | 164 | 0.19 | (0.09–0.39) | 8 | 216 | 0.15 | (0.06–0.39) |

| ≥20 years former drinkers | 44 | 144 | 0.40 | (0.18–0.88) | 5 | 23 | 0.44 | (0.08–2.38) | 10 | 98 | 0.21 | (0.08–0.56) | 16 | 166 | 0.15 | (0.07–0.31) | 8 | 114 | 0.34 | (0.12–0.93) |

| Never drinkers | 391 | 538 | 0.52 | (0.19–1.45) | 17 | 56 | 0.32 | (0.14–0.75) | 22 | 198 | 0.24 | (0.06–0.91) | 33 | 237 | 0.21 | (0.12–0.37) | 243 | 1720 | 0.26 | (0.12–0.6) |

| Total | 2066 | 9471 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Missing | 127 | 299 | ||||||||||||||||||

| P for heterogeneityd | <0.01 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Oropharynx/Hypopharynx | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Current drinkers | 690 | 1355 | 1.00 | Ref. | 43 | 139 | 0.73 | (0.22–2.39) | 101 | 650 | 0.41 | (0.21–0.8) | 76 | 487 | 0.36 | (0.11–1.13) | 106 | 1305 | 0.29 | (0.07–1.27) |

| >1–4 years former drinkers | 74 | 99 | 0.90 | (0.34–2.36) | 23 | 45 | 1.01 | (0.14–7.08) | 13 | 49 | 0.46 | (0.16–1.28) | 7 | 36 | 0.61 | (0.04–10.31) | 4 | 73 | 0.69 | (0.05–8.78) |

| 5–19 years former drinkers | 193 | 213 | 1.19 | (0.64–2.22) | 23 | 39 | 0.73 | (0.29–1.85) | 76 | 184 | 0.77 | (0.36–1.67) | 26 | 105 | 0.59 | (0.21–1.67) | 15 | 156 | 0.29 | (0.07–1.16) |

| ≥20 years former drinkers | 66 | 117 | 0.82 | (0.42–1.6) | 6 | 18 | 0.75 | (0.17–3.29) | 13 | 77 | 0.37 | (0.1–1.39) | 22 | 104 | 0.63 | (0.16–2.45) | 13 | 84 | 0.51 | (0.07–3.73) |

| Never drinkers | 118 | 465 | 0.56 | (0.2–1.52) | 13 | 46 | 0.95 | (0.15–5.91) | 16 | 151 | 0.24 | (0.09–0.61) | 17 | 165 | 0.27 | (0.07–0.99) | 110 | 1407 | 0.26 | (0.07–0.97) |

| Total | 1864 | 7569 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Missing | 63 | 262 | ||||||||||||||||||

| P for heterogeneityd | <0.01 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Larynxf | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Current drinkers | 639 | 1181 | 1.00 | Ref. | 44 | 123 | 0.83 | (0.46–1.49) | 122 | 655 | 0.44 | (0.31–0.62) | 52 | 576 | 0.23 | (0.14–0.36) | 35 | 1284 | 0.13 | (0.06–0.32) |

| >1–4 years former drinkers | 80 | 92 | 1.25 | (0.41–3.86) | 21 | 36 | 0.72 | (0.3–1.7) | 16 | 49 | 0.50 | (0.2–1.22) | 7 | 36 | 0.33 | (0.08–1.31) | 4 | 71 | 0.16 | (0.04–0.68) |

| 5–19 years former drinkers | 184 | 213 | 1.05 | (0.69–1.6) | 13 | 44 | 0.47 | (0.17–1.34) | 53 | 185 | 0.41 | (0.25–0.68) | 13 | 117 | 0.21 | (0.07–0.71) | 8 | 159 | 0.15 | (0.05–0.44) |

| ≥20 years former drinkers | 89 | 116 | 0.74 | (0.46–1.2) | 10 | 18 | 0.84 | (0.24–2.95) | 26 | 82 | 0.37 | (0.18–0.76) | 13 | 114 | 0.14 | (0.06–0.34) | 6 | 85 | 0.24 | (0.07–0.85) |

| Never drinkers | 118 | 263 | 1.21 | (0.45–3.25) | 16 | 41 | 0.77 | (0.24–2.47) | 17 | 124 | 0.25 | (0.11–0.58) | 18 | 152 | 0.24 | (0.1–0.58) | 24 | 873 | 0.10 | (0.02–0.51) |

| Total | 1628 | 6689 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Missing | 45 | 125 | ||||||||||||||||||

| P for heterogeneityd | 0.02 | |||||||||||||||||||

Ca = cases; Co = controls.

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, study centre, education level, tobacco PYs and drinking frequency.

Does not include the Milan, Aviano, France, Switzerland, Central Europe, New York, Seattle, North Carolina, Tampa and Rome studies.

Two-sided test for heterogeneity among studies.

Does not include the Iowa, Puerto Rico and Boston studies.

Does not include the Iowa, Puerto Rico and international multicentre studies.

The ORs for quitting alcohol drinking did not change substantially after adjustment for BMI, for passive smoking or for family history of head and neck cancer (results not shown). The risk estimates after cessation of drinking were also not affected by excluding subjects with chewing or snuff use habits (results not shown).

When the analysis was stratified separately by age, sex, education level, race/ethnicity, region, study year and study sample size, the effect of quitting alcohol drinking was consistent (results not shown). On the other hand, we observed differences after stratification by study type. Regardless of how many years a subject had quit drinking, the risk reduction of head and neck cancer was more pronounced in the seven hospital-based studies (≥20 years quitting OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.25–0.81; never OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.39–0.81, data not shown) than in the four population-based studies (≥20 years quitting: OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.54–1.45; never: OR 1.39, 95% CI 0.60–3.18, data not shown).

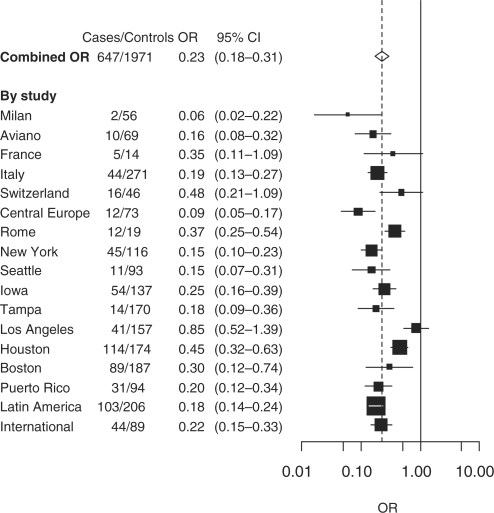

Cessation of tobacco smoking

The risk of head and neck cancer decreased among persons who had stopped tobacco smoking 1–4 years previously (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.61–0.81; Table 2). The reduced risk of head and neck cancer after quitting smoking for ≥20 years (OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.18–0.31) was similar to that of never smokers (OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.16–0.34). Current and former tobacco smokers had a higher relative risk of laryngeal cancer than oral or pharyngeal cancer. The inverse relationship was observed for the risk of all head and neck cancer subsites for quitting tobacco smoking (P for trend <0.01). After quitting smoking ≥20 years, the ORs were similar to that of never smokers for oral and pharyngeal cancers, but not for laryngeal cancer.

An inverse association between quitting tobacco smoking for ≥20 years and the risk of head and neck cancer was reported in all studies (Figure 2). The risk of head and neck cancer after quitting smoking decreased with increasing frequency (Table 3) and duration of tobacco smoking (data not shown). We observed an increased risk among former low frequency smokers who recently stopped smoking for oral cavity and laryngeal cancer.

Figure 2.

Cessation of smoking ≥20 years and head and neck cancer risk compared with current smoking

After cessation of tobacco smoking, current and former alcohol drinkers showed a reduced risk for every head and neck cancer subsite (Table 4). Among never alcohol drinkers, we observed a risk reduction due to quitting smoking only for laryngeal cancer, but not for oral cavity cancer or pharyngeal cancer. Table 4 was replicated within sub-strata of frequency of drinking and PY of tobacco smoking. The results were similar to the overall results.

The reversal of head and neck cancer risk after quitting smoking did not change when subjects with chewing or snuff use habits were excluded (results not shown). In addition, exclusion of the Indian centres of the international multicentre study did not change our results for the cessation of tobacco smoking or alcohol drinking. Adjustment for BMI at age 30 years or for family history of head and neck cancer also did not change the inverse association between smoking cessation and head and neck cancer risk substantially (data not shown). Strong differences in the association between smoking cessation and head and neck cancer were not observed after stratification by age, sex, race/ethnicity, geographic region, education level, study type, study year and study sample size (results not shown).

Discussion

The results of our pooled analysis showed a beneficial effect on the risk of all head and neck cancer subsites after quitting tobacco smoking within as little as 1–4 years. In contrast, we only estimated a benefit on the risk of head and neck cancer after ∼20 years of quitting alcohol drinking; the beneficial effect of drinking cessation was not as substantial as that of smoking cessation. However, for both cessation of drinking and cessation of smoking, the risk was reduced to the level of never users after 20 years of quitting these habits.

Consistent with the results from previous studies, a reduced risk of head and neck cancer after drinking cessation was detected mainly for oral cavity cancer7,9 and laryngeal cancer.16,23 On the other hand, regardless of drinking frequency and smoking status, risk reduction of pharyngeal cancer after stopping drinking was not as strong. These results are also in accordance with published results of the study from Uruguay,23 and the multicentre study from Italy and Switzerland.22 Furthermore, individuals needed to quit drinking for ≥20 years to show a 40% risk reduction of head and neck cancer. This may be due to either a longer time between intake of alcohol and increase of head and neck cancer risk, or a certain amount of irreversible damage associated with drinking that are with long-lasting effect. Additionally, it is possible that the effect of alcohol drinking may act directly or indirectly in an early phase of the multistep process of head and neck cancer development.16,22,32 However, such interpretations are difficult to make based on these data alone, since underlying mechanisms are complicated and mostly unknown.33

The risk to ex-smokers was similar to the risk of never smokers after ∼20 years for oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer,10,18–21 but not for laryngeal cancer,15–17 consistent with previous studies. This persistent increased risk for laryngeal cancer compared with never smokers was also reported for lung cancer after a long interval of smoking cessation,12 consistent with the notion that laryngeal cancer shares a closer a etiology with lung cancer than with oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer.

The inverse association between head and neck cancer and smoking cessation was stronger than with drinking cessation. These results are in agreement with most previous studies of drinking and smoking cessation and the risk of head and neck cancer.7–10,12,16,23 In addition, our results did not show a benefit of quitting drinking among former and never tobacco smokers. A possible explanation may be that the risk conferred by alcohol drinking is lower than that conferred by tobacco smoking or by the joint effect of both, and thus it may be difficult to detect a risk reduction due to cessation of alcohol drinking among former and never smokers in epidemiological studies.

The lack of influence of drinking duration has been noted in previous studies.18,22 Perhaps there is a correlation of long-term drinking with a less intensive pattern of alcohol drinking (e.g. occasional drinking, only with meals). We observed a benefit after quitting alcohol drinking only for subjects who drank one drink or more per day. On the other hand, the great risk reduction of head and neck cancer after quitting tobacco smoking among short- and long-term smokers, as well as among light and heavy smokers underscores the importance of preventing head and neck cancer by encouraging individuals to quit smoking.

After stratification by study design, we observed a less pronounced risk reduction of head and neck cancer after cessation of alcohol drinking in the population-based studies than in the hospital-based studies. The statistical power of the population-based studies was less than that of the hospital-based studies, since the majority of our data were from the latter design. This may explain our weak association for drinking cessation in the population-based studies.

Our results should be interpreted carefully, since this pooled analysis of case–control studies has the limitation that the exposure assessment could have been subject to recall bias. Hospitalized cases (regardless of study design) and hospitalized controls may tend to report inaccurately that they have stopped alcohol drinking before they came to the hospital, whereas healthy controls from the general population may be less likely to do so. This may decrease the proportion of current drinkers among cases who are hospitalized, which may cause a bias towards the null of drinking cessation among the population-based case–control studies. Among the hospital-based studies, the number of current drinkers may decrease among cases and controls, and thus the effect of such a bias is difficult to predict. However, we observed a lower risk of head and neck cancer after ≥20 years quitting alcohol drinking among hospital-based case–control studies compared with population-based case–control studies.

Given this possibility of recall bias in our analysis of case–control studies, results from cohort studies would be important to confirm the effect of drinking cessation on head and neck cancer risk. Recent cohort studies showed greater risk of head and neck cancer due to alcohol drinking than case–control studies.34 Thus, the risk reduction of head and neck cancer may also be greater after cessation of alcohol drinking in cohort studies, since the ORs were lower after quitting ≥20 years if the baseline risk of current alcohol drinking was higher. However, most cohort studies only have baseline information on alcohol consumption and do not measure detailed drinking habits beyond baseline. Thus, it may not be possible to evaluate time since quitting drinking over a follow-up time of ≥30 years in cohort studies.

The increased risk of head and neck cancer in the first 2 years of quitting tobacco or alcohol use that we observed in some sub-groups may be due to the fact that some cases could have stopped drinking or smoking because of early symptoms of the disease, which adds cases to the former users and causes an underestimation of the reversal in risk after quitting (exposure misclassification among cases). This seems especially true for drinking cessation because in contrast to major policies on tobacco, there is no general public health intervention for quitting drinking (i.e. higher taxes). Quitting alcohol drinking could be motivated by other harmful circumstances caused by alcohol consumption, e.g. social consequences like dependence or the diagnosis of other diseases. Some smokers may also not believe that their smoking pattern is unhealthy or may have been unable to stop prior to having a cancer diagnosis and may stop smoking only because of early signs and symptoms of head and neck cancer, which may also increase the risk of head and neck cancer in the first years after quitting smoking.

Potential confounders of our results include other known risk factors of head and neck cancer that could be associated with quitting drinking or smoking, such as chewing tobacco or snuff use,8,35 low BMI36 and low vegetable and fruit consumption. However, adjustment for BMI did not materially affect the estimates of the beneficial effects of cessation. The reduced risk of head and neck cancer after quitting was also not different when subjects with chewing and snuff use were excluded. High fruit and vegetable consumption could be associated with drinking cessation or smoking cessation and could also reduce the risk of head and neck cancer, but we believe that this alone could not explain the strong beneficial effect after quitting smoking or drinking.

Another possible limitation of our study is the use of different combinations of studies for different sub-analyses and the heterogeneity between specific estimates from the individual studies. This may be partly due to regional variation of tobacco and alcohol types and variation of smoking and drinking pattern, as well as differences in study design. To account for other unknown sources of heterogeneity in the analysis, we treated the study effects on a second level as random variations around a population mean. In this mixed model, studies were weighted more equally with increasing heterogeneity by giving smaller weights to larger studies than in a fixed effect model.

On the contrary, our pooled analysis has many strengths. The heterogeneity of the study population allowed us to evaluate the beneficial effect of cessation of alcohol drinking and tobacco smoking in different subgroups, e.g. stratification by geographical region and sex. Furthermore, the large number of subjects increased the statistical power for analysing finer categories, such as cessation of ≥20 years, which was especially important for estimating a beneficial effect after quitting of alcohol drinking and after quitting of tobacco smoking among never drinkers.

In summary, cessation of tobacco smoking and cessation of drinking was associated with a reduction in the risk of head and neck cancer.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (NIH) US, National Cancer Institute (NCI) [R03 CA113157]. The individual studies were funded by the following grants: Milan study: Italian Association for Research on Cancer (AIRC); Aviano and Italy multicentre studies: Italian Association for Research on Cancer (AIRC), Italian League Against Cancer and Italian Ministry of Research; France study: Swiss League against Cancer [KFS1069-09-2000], Fribourg League against Cancer [FOR381.88], Swiss Cancer Research [AKT 617] and Gustave-Roussy Institute [88D28]; Swiss study: Swiss League against Cancer and the Swiss Research against Cancer/Oncosuisse [KFS-700, OCS-1633]; Central Europe study: World Cancer Research Fund and the European Commission's INCO-COPERNICUS Program [Contract No. IC15-CT98-0332]; New York study: National Institutes of Health (NIH) US [P01CA068384 K07CA104231]; Seattle study: National Institutes of Health (NIH) US [R01CA048896, R01DE012609]; Boston study: National Institutes of Health (NIH) US [R01CA078609, R01CA100679]; Iowa study: National Institutes of Health (NIH) US [NIDCR R01DE11979, NIDCR R01DE13110, NIH FIRCA TW01500] and Veterans Affairs Merit Review Funds; North Carolina study: National Institutes of Health (NIH) US [R01CA61188], and in part by a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [P30ES010126]; Tampa study: National Institutes of Health (NIH) US [P01CA068384, K07CA104231, R01DE13158]; Los Angeles study: National Institute of Health (NIH) US [P50CA90388, R01DA11386, R03CA77954, T32CA09142, U01CA96134, R21ES011667] and the Alper Research Program for Environmental Genomics of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center; Houston study: National Institutes of Health (NIH) US [R01ES11740, R01CA100264]; Puerto Rico study: jointly funded by National Institutes of Health (NCI) US and NIDCR intramural programs; Latin America study: Fondo para la Investigacion Cientifica y Tecnologica (FONCYT) Argentina, IMIM (Barcelona), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa no Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) [No 01/01768-2], and European Commission [IC18-CT97-0222]; IARC Multicenter study: Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS) of the Spanish Government [FIS 97/0024, FIS 97/0662, BAE 01/5013], International Union Against Cancer (UICC), and Yamagiwa-Yoshida Memorial International Cancer Study Grant.

Acknowledgement

M.M. received a Special Training Award from the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

KEY MESSAGES.

The main risk factors for head and neck cancer are alcohol drinking and tobacco smoking, which together account for ∼75% of the disease.

Our results support that tobacco and alcohol cessation protect against the development of head and neck cancer.

Quitting tobacco smoking showed a beneficial effect on the risk of all head and neck cancer subsites within as little as 1–4 years, whereas cessation of alcohol drinking only provides a benefit after ∼20 years of quitting.

For cessation of both smoking and drinking, the risk was reduced to the level of never users after 20 years of quitting these habits.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Bray F, Pisani P, Parkin D. GLOBOCAN 2002: Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide IARC CancerBase No. 5. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franceschi S, Bidoli E, Herrero R, Munoz N. Comparison of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx worldwide: etiological clues. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:106–15. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(99)00070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Silverman S., Jr Trends in oral cancer rates in the United States, 1973–1996. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:249–56. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.280402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.La Vecchia C, Lucchini F, Negri E, Levi F. Trends in oral cancer mortality in Europe. Oral Oncol. 2004;40:433–39. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blot W, McLaughlin J, Devesa S, Fraumeni J. Cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx. In: Schoffenfeld D, Fraumeni J, editors. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 666–80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franceschi S, Talamini R, Barra S, et al. Smoking and drinking in relation to cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and esophagus in northern Italy. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6502–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrote LF, Herrero R, Reyes RM, et al. Risk factors for cancer of the oral cavity and oro-pharynx in Cuba. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:46–54. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balaram P, Sridhar H, Rajkumar T, et al. Oral cancer in southern India: the influence of smoking, drinking, paan-chewing and oral hygiene. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:440–45. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castellsague X, Quintana MJ, Martinez MC, et al. The role of type of tobacco and type of alcoholic beverage in oral carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:741–49. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Stefani E, Boffetta P, Deneo-Pellegrini H, et al. The effect of smoking and drinking in oral and pharyngeal cancers: a case-control study in Uruguay. Cancer Lett. 2007;246:282–89. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosetti C, Garavello W, Gallus S, La Vecchia C. Effects of smoking cessation on the risk of laryngeal cancer: an overview of published studies. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:866–72. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IARC. IARC Handboods of Cancer Prevention, Tobacco Control, Vol. 11. Reversal of Risk After Quitting Smoking. Lyon: IARC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosetti C, Gallus S, Peto R, et al. Tobacco smoking, smoking cessation, and cumulative risk of upper aerodigestive tract cancers. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:468–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Colditz GA. Smoking and smoking cessation in relation to mortality in women. JAMA. 2008;299:2037–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.17.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlecht NF, Franco EL, Pintos J, Kowalski LP. Effect of smoking cessation and tobacco type on the risk of cancers of the upper aero-digestive tract in Brazil. Epidemiology. 1999;10:412–18. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199907000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altieri A, Bosetti C, Talamini R, et al. Cessation of smoking and drinking and the risk of laryngeal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:1227–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menvielle G, Luce D, Goldberg P, Bugel I, Leclerc A. Smoking, alcohol drinking and cancer risk for various sites of the larynx and hypopharynx. A case-control study in France. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2004;13:165–72. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000130017.93310.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Winn DM, et al. Smoking and drinking in relation to oral and pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3282–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day GL, Blot WJ, Austin DF, et al. Racial differences in risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer: alcohol, tobacco, and other determinants. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:465–73. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.6.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabat GC, Chang CJ, Wynder EL. The role of tobacco, alcohol use, and body mass index in oral and pharyngeal cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:1137–44. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.6.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes RB, Bravo-Otero E, Kleinman DV, et al. Tobacco and alcohol use and oral cancer in Puerto Rico. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:27–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1008876115797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franceschi S, Levi F, Dal Maso L, et al. Cessation of alcohol drinking and risk of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:787–90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000315)85:6<787::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Stefani E, Brennan P, Boffetta P, et al. Comparison between hyperpharyngeal and laryngeal cancers: I-tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking. Cancer Therapy. 2004;2:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Benhamou S, et al. Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:777–89. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Ninth Revision. 9th. Geneva: WHO; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Percy C, Van Holten V, Muir C. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 2nd. Geneva: WHO; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision. 10th. Geneva: WHO; 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun EC, Curtis R, Melbye M, Goedert JJ. Salivary gland cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:1095–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenland S, Finkle WD. A critical look at methods for handling missing covariates in epidemiologic regression analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1255–64. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harel O, Zhou XH. Multiple imputation: review of theory, implementation and software. Stat Med. 2007;26:3057–77. doi: 10.1002/sim.2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan YC. Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Annual SAS Users Group International Conference. Paper 267; 2000. Multiple imputation for missing data: concepts and new development; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Day NE, Brown CC. Multistage models and primary prevention of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980;64:977–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen OM, Paine SL, McMichael AJ, Ewertz M. Alcohol. In: Schottenfeld MD, Fraumeni JR, editors. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 290–318. [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington DC: AICR; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warnakulasuriya S, Trivedy C, Peters TJ. Areca nut use: an independent risk factor for oral cancer. BMJ. 2002;324:799–800. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bosetti C, Gallus S, Franceschi S, et al. Cancer of the larynx in non-smoking alcohol drinkers and in non-drinking tobacco smokers. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:516–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]