Abstract

Insect herbivores are considered vulnerable to extinctions of their plant hosts. Previous studies of insect-damaged fossil leaves in the US Western Interior showed major plant and insect herbivore extinction at the Cretaceous–Palaeogene (K–T) boundary. Further, the regional plant–insect system remained depressed or ecologically unbalanced throughout the Palaeocene. Whereas Cretaceous floras had high plant and insect-feeding diversity, all Palaeocene assemblages to date had low richness of plants, insect feeding or both. Here, we use leaf fossils from the middle Palaeocene Menat site, France, which has the oldest well-preserved leaf assemblage from the Palaeocene of Europe, to test the generality of the observed Palaeocene US pattern. Surprisingly, Menat combines high floral diversity with high insect activity, making it the first observation of a ‘healthy’ Palaeocene plant–insect system. Furthermore, rich and abundant leaf mines across plant species indicate well-developed host specialization. The diversity and complexity of plant–insect interactions at Menat suggest that the net effects of the K–T extinction were less at this greater distance from the Chicxulub, Mexico, impact site. Along with the available data from other regions, our results show that the end-Cretaceous event did not cause a uniform, long-lasting depression of global terrestrial ecosystems. Rather, it gave rise to varying regional patterns of ecological collapse and recovery that appear to have been strongly influenced by distance from the Chicxulub structure.

Keywords: Palaeocene, Europe, herbivory, plant–insect interactions, end-Cretaceous extinction

1. Introduction

The Palaeogene was a time of profound reorganization of the biosphere, following the catastrophic Cretaceous–Palaeogene (we use the traditional acronym K–T) bolide impact at 65.5 Ma (e.g. Jablonski & Raup 1995; Alroy 1999; Pearson et al. 2002; MacLeod et al. 2006; Benton & Harper 2009). Among the many consequences was substantial turnover for North American plants and herbivorous insects (Tschudy et al. 1984; Wolfe & Upchurch 1986; Johnson et al. 1989; Hotton 2002; Labandeira et al. 2002a,b; Nichols 2002; Wilf & Johnson 2004), expressed in a general pattern of low-diversity floras throughout the 10 Myr of the Palaeocene and a nearly complete loss of specialized insect-feeding damage on leaves until the last approximately 1 Myr of the Palaeocene (Wing et al. 1995; Labandeira et al. 2002a,b; Wilf et al. 2006; Currano et al. 2008).

There are two known exceptions to the general Palaeocene depression: an extremely diverse (used here synonymously with rich, speciose) flora with little insect damage, from Castle Rock, Colorado, and a typically depauperate flora with extremely rich and abundant insect damage, from Mexican Hat, Montana (Johnson & Ellis 2002; Ellis et al. 2003; Wilf et al. 2006). However, at no time during the Palaeocene was there a diverse flora together with diverse insect damage in North America, indicating either depressed or decoupled development of plants and insect herbivores in perhaps unbalanced ecosystems (Wilf et al. 2006; Currano et al. 2008; Wilf 2008). These patterns have been recorded and quantified as a certain range of feeding-type diversity and specialized damage (e.g. insect mining) on Maastrichtian through Eocene floras in the Western Interior of North America (Labandeira et al. 2002b; Wilf et al. 2006).

The extent of this ecological catastrophe in terrestrial ecosystems outside the Western Interior remains poorly known because the quantity and stratigraphic resolution of continental sequences with abundant plant or insect fossils covering the relevant time intervals diminishes dramatically elsewhere (Nichols & Johnson 2008). Palaeogene floristic patterns for the Northern Hemisphere outside North America have been described by various authors (e.g. Wolfe 1985; Mai 1995; Collinson 2000; Tiffney & Manchester 2001; Collinson & Hooker 2003; Akhmetiev & Beniamovski 2009). Herein, we present the first analysis of fossil plant–insect interactions from the Palaeocene of Europe. Our data derive from the middle Palaeocene Menat fossil site (Menat Basin, Puy-de-Dôme, France; approx. 60–61 Ma), which has the European macroflora that is stratigraphically closest to the K–T event (Piton 1940; Mai 1995; we note that there are no suitable macrofloras known from the European terminal Cretaceous). In sharp contrast to the US data, we find high values of insect-feeding damage coupled with elevated floral richness. These results, though from a single site, are the first evidence for more robust, undepressed plant–insect systems during the Palaeocene.

2. Geological setting and locality information

The geological setting, stratigraphy, depositional environment and age of the middle Palaeocene fossil-lagerstätte Menat are reviewed in detail elsewhere (Vincent et al. 1977; Kedves & Russell 1982) and summarized here and in the electronic supplementary material. The Menat Pit fossil site is located within the Department Puy-de-Dôme, France, near the town of Gannat in the northwestern part of the Massif Central (46°06′ N, 02°54′ E). It represents a fossil lake with sedimentary infill, interpreted as a maar lake, created by volcanic activity (Vincent et al. 1977). The geology, geochemistry and composition of the fossil assemblages clearly indicate a warm palaeoclimate and a forested palaeo-environment in the lake catchment, dominated by Lauraceae, Platanaceae and Fagales (Fritel 1903; Laurent 1912, 1919; Piton 1940), the same higher groups that are common at nearly all of the US sites (e.g. Wilf et al. 2006). Plants from Menat are preserved as impressions and compressions in thinly laminated, bituminous shales (spongo-diatomite). The typical leaf assemblage is shown in Mai (1995, fig. 134) and in figs S3–S7 in the electronic supplementary material. There is no evidence for climate being an important factor affecting the interpretation of results from Menat (see fig. S2 and table S1 in the electronic supplementary material).

3. Material and methods

(a). Databases

We compare the Menat flora with the pre-existing dataset of latest Cretaceous through earliest Eocene insect-feeding damage on fossil leaves in the US Western Interior basins; the US data have provided abundant information regarding how extinction, as well as climate change, affects plant–insect systems (Wilf & Labandeira 1999; Johnson 2002; Labandeira et al. 2002a,b; Wilf et al. 2006; Currano et al. 2008). With Menat included, the total dataset considered here comprises a total of 16 846 fossil leaves from 16 sites with well-resolved stratigraphic ages, spanning approximately 11 Myr from the latest Cretaceous (66.5 Ma, terminal Maastrichtian) to the Palaeocene–Eocene boundary (55.8 Ma, Ypresian, Palaeocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum; see table S1 in the electronic supplementary material).

(b). Data acquisition

European fossil plants were examined from field collections done by the Musées Association Rhinopolis, Gannat, in 2006 and 2007, and every identifiable dicot leaf with at least half of the blade preserved was collected. Field collections, used in the statistical analyses, were supplemented with relevant historical collections from the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris (Coll. Piton, Coll. Saporta, Coll. Giniès). A total of 1130 specimens of leaves, fruits and flowers were preserved (figure 1). As for the US sites, all specimens of leaves, or leaflets in the case of compound leaves, thought to be from woody, non-monocot (‘dicot’) angiosperms, were identified to species when possible (or to morphotypes when taxonomy was ambiguous), and non-angiosperm plants were not included in the analysis. Unidentified specimens (15.7% of the collections) had poor preservation and/or a lack of diagnostic characteristics. These were excluded from analysis, resulting in a total of 792 applicable dicot leaves. Piton's (1940) monograph and subsequent taxonomic revisions of the flora (Knobloch & Kvaček 1965; Jones et al. 1988; Kvaček & Walther 1989; Manchester 1989; Hably 2006; Wang et al. 2007) were used to identify the plants. In our opinion, this taxonomy remains slightly oversplit, especially for Lauraceae, and there is the possibility of collection bias in the historical samples. All specimens are housed in the palaeobotanical collections of the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. We recorded the presence and absence of 39 discrete morphologies of insect damage, or ‘damage types’ (DTs), within four functional feeding groups (FFGs: external foliage feeding, mining, galling and piercing-and-sucking). We used the scoring system of Labandeira et al. (2007; see also the electronic supplementary material), which was also used on the US sites.

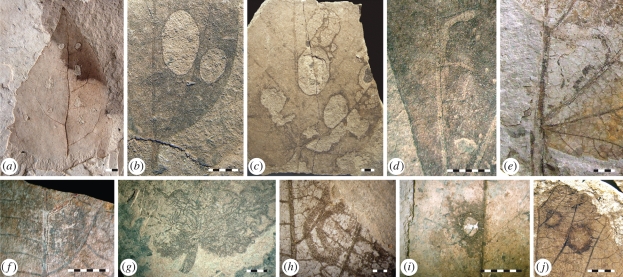

Figure 1.

Representative insect damage from the Palaeocene of Menat, France. (a) Characteristic large, circular hole feeding (DT4 of Labandeira et al. 2007) on unidentified dicot sp. (Morphotype I; MNT 06 3493); (b) large, circular hole feeding (DT4) on Cinnamomum sp. (Lauraceae; 20 909); (c) skeletonization (DT16) and large, circular hole feeding (DT4) on Corylus macquarrii (20 816); (d) serpentine mine, parallel-sided, thin reaction rim (DT41) on Luheopsis vernieri (21 209); (e) serpentine lepidopteran mine with thick, initially intestiniform but subsequently looser frass trail (DT41) on C. macquarrii (Betulaceae; 15 083); (f) serpentine mine on C. macquarrii with confined, linear, median frass trail (DT41; 20 847); (g) sinusoidal mine, probably lepidopteran (Nepticulidae; DT92), on C. macquarrii with frass trail of dispersed rounded pellets oscillating across the full mine width (MNHN-LP-R 63 913); (h) undulating lepidopteran mine on C. macquarrii with pelleted frass trail (DT95; 20 747); (i) circular galling structure, surrounded by thick, dense, reaction tissue (DT11) on Fraxinus sp. (MNT 05 115.1); (j) circular galls on 3° veins, central chamber sharply separated from a wide, thick carbonized brim on C. macquarrii (DT110; MNHN-LP-R 63 917). Scale bars, 5 mm. MNT, collection number from the Musées Association Rhinopolis; MNHN-LP-R, collection number from the Laboratoire de Paléontologie, Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France.

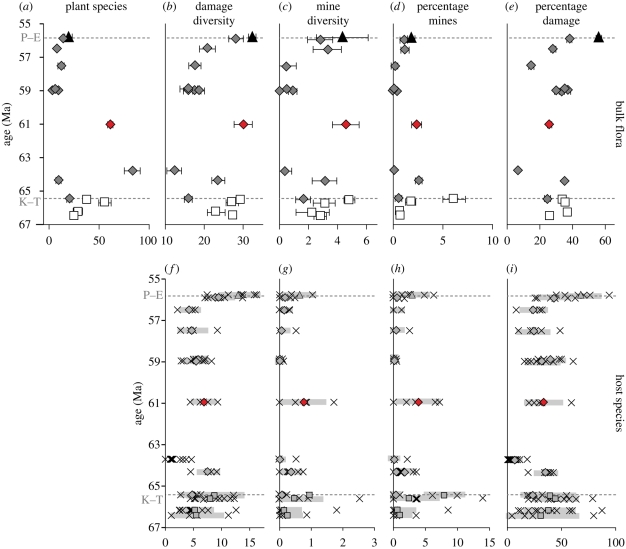

We also considered insect herbivory on individual host plants (figure 2f–i). Species-level damage data should be less affected by the overall floral richness and by the increased spatial and temporal averaging at Menat (see Currano 2009 and also Novotny et al. 2007 for limited beta diversity of herbivores over large host-plant ranges). Therefore, although we present both, we feel that species-level herbivory data are more suitable for comparison than bulk floral data.

Figure 2.

Insect damage on (a–e) bulk floral assemblages and (f–i) individual plant hosts from Menat compared with US Western Interior floras. (a) Number of dicot species at each site rarefied to 400 leaves; error bars represent the standard error of Heck et al. (1975). (b) Total damage diversity (number of DTs) on each flora standardized to 400 leaves by averaging damage diversity for 5000 random subsamples of 400 leaves without replacement. Error bars represent ±1σ of the mean of the resamples. (c) Sampling-standardized mine diversity on the bulk floras, calculated as in (b). (d) Percentage of leaves at each site with mines. Error bars represent ±1σ, based on a binomial sampling distribution. (e) Percentage of leaves with damage at each site with damage; error bars as in (d). (f) Damage diversity on individual species at each site, standardized to 25 leaves. Each × represents a single plant host, which was randomly resampled without replacement as in (b). The filled symbols are the among-species means for the site, and the thick grey lines delineate one standard deviation. (g) Sampling standardized mine diversity on individual host plants, as in (f). (h) Percentage of leaves of each species (with at least 25 leaves in the flora) with mines. Symbols as in (f). (i) Percentage of leaves of each species with damage, as in (h). P–E, Palaeocene–Eocene boundary; K–T, Cretaceous–Palaeogene boundary. (a–e) Bulk flora: black triangle, Eocene; grey diamond, Palaeocene; red diamond, Menat; white square: Cretaceous. (f–i) Host species: triangle, diamonds and square, site average; cross, single host.

(c). Taphonomic bias

Previous studies indicate that the depositional environment has an effect on recovered floral diversity (Wing & DiMichele 1995). Menat represents a more or less isolated lacustrine system that originated in a deep maar lake with a highly diverse taphocoenosis trapped (Piton 1940). In contrast, the studied North American sites are more or less parautochthonous and were formed in a range of fluvial depositional settings (abandoned channel beds, floodplain ponds, flooded forest floors or river channels in the case of the Cretaceous sites; Wing et al. 1995; Johnson 2002). The North American floras are not analogous to Menat in that they represent low-relief, floodplain palaeo-environments and perhaps less than 100 years of accumulation, whereas lacustrine assemblages such as Menat represent significantly more temporal averaging than all the US sites and more spatial averaging than the US Palaeocene and Eocene sites (e.g. Wing & DiMichele 1995).

(d). Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed from census data using the R statistical environment (R Development Core Team 2008). The complete census data for the Menat megafloral site and further details on the statistical analyses are provided in the electronic supplementary material.

4. Results

The Menat megaflora had 76 dicot-leaf species, which represent a much higher diversity than any of the sites studied here from the Western USA, except the Castle Rock rainforest site (Johnson & Ellis 2002; Ellis et al. 2003). Menat's richness may be inflated relative to that of the USA owing to the differing depositional environments and, to some extent, from taxonomic splitting, but the difference is nevertheless obvious and highly significant (see figs S3–S7 in the electronic supplementary material). To underscore this point, we note that the richest Palaeocene or Eocene lacustrine leaf flora known from the USA is the early Eocene Republic flora from Washington State (Wolfe & Wehr 1987; Pigg et al. 2007). When sampled using very similar collecting methods, Republic yielded a much lower total of 58 dicot-leaf species from approximately 1000 specimens, equivalent to 51.6 ± 4.3 species when rarefied to the sample size of Menat (Wilf et al. 2005).

Total damage and mine-damage diversity on the Menat bulk flora parallel the high plant diversity (figure 2a–e), making Menat outstanding in comparison with all the North American Palaeocene floras. Total frequency shows little pattern throughout the dataset, whereas mine frequency shows the same general pattern as the diversity data. If the sites are split into two groups based on damage diversity, mine diversity and mine frequency, the Cretaceous sites, Mexican Hat, Menat and the latest Palaeocene and Palaeocene Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) sites fall in a high-diversity and high-frequency group (figure 2b–d), whereas the remaining early and middle Palaeocene sites show only depressed insect damage.

The species-level data reveal an unexpectedly high degree of host specialization for Menat (e.g. mining; figure 2g,h), in sharp contrast to the conspicuous drop following the K–T boundary at the US sites (Labandeira et al. 2002b; Wilf et al. 2006). Unlike most of the Palaeocene US sites, mining at Menat occurs on more than one host lineage. The only other sites in which this pattern is observed are the Cretaceous suite, Mexican Hat and the PETM site (figure 2f,h). The betulaceous Corylus macquarrii (figures 1b,c,h,i and 2g,h) is particularly rich in mines, with four mine DTs and 12 occurrences. The species-damage diversity data indicate that the bulk data (in which damage diversity at Menat is higher than all the early to early–late US Palaeocene sites) reflect a true diversity pattern, even though overall floral richness can be taphonomically influenced (vide infra). The diversity and prevalence of host-specialized mining morphotypes on so many different host plants is especially striking, indicating well-developed specialized feeding associations on a broad spectrum of host lineages (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of plant hosts from Menat with at least 25 leaves; errors represent the 95 percent prediction intervals. dam., damaged; DT, damage type.

| species | plant group | number of leaves | % of flora | total DTs | % dam. | % mined | total DTsa | mine DTsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corylus macquarrii | Betulaceae | 139 | 14.8 | 22 | 28.8 (±3.84) | 8.6 (±2.19) | 7.4 (±2.29) | 1.7 (±0.92) |

| Dryophyllum dewalquei | Fagales | 99 | 10.6 | 12 | 24.2 (±4.30) | 2.0 (±1.41) | 4.4 (±1.37) | 0.5 (±0.62) |

| Salix lamottei | unknown | 38 | 4.1 | 8 | 31.6 (±7.54) | 0 | 6.2 (±1.13) | 0 |

| Cinnamomum sp. | Laurales | 31 | 3.3 | 8 | 19.4 (±7.10) | 3.2 (±4.43) | 6.8 (±1.49) | 0.8 (±0.39) |

| Fraxinus sp. | unknown | 29 | 3.1 | 10 | 58.6 (±9.15) | 3.4 (±3.37) | 9.3 (±0.87) | 0.9 (±0.35) |

aStandardized to 25 leaves.

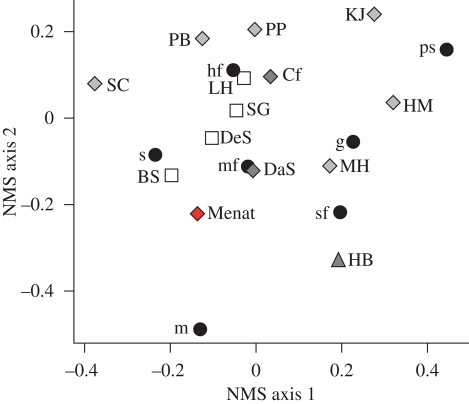

As expected, ordinations using non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (NMS) emphasize the exceptional position of Menat (figure 3). The points closest to it are the two most highly diverse Cretaceous floras (Battleship and Dean Street) and the latest Palaeocene Daiye Spa, which, as shown in figure 2, reflects some rebound from the extinction related to climatic warming (Currano et al. 2008). Menat has greater mining richness and frequency than Daiye Spa, which, in turn, has a high mining percentage for the Western Interior.

Figure 3.

Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (NMS) ordination of the insect damage on the bulk floras. The 14 sites were ordinated in NMS using a matrix of the percentage of leaves at each site with each FFG; FFGs were also ordinated based on their occurrences at the sites, and they are plotted on the same axis. Castle Rock and Lur'd leaves are not included in the analysis because their extremely low damage frequencies turn NMS axis 1 into a measure of damage frequency, thus limiting comparisons among sites based on damage composition. Dark grey triangle, Eocene site; dark grey diamond, late–late Palaeocene site; light grey diamond, early–late Palaeocene site; white square, Cretaceous site; black circle, FFG. For abbreviations of sites and FFGs, see the electronic supplementary material.

Because the Menat plant species are not found in North America, we estimated leaf mass per area (LMA) to test whether the US sites have significantly different leaf properties that may affect herbivores. Leaves with high LMA are thicker, tougher and generally have lower nutrient concentrations (Wright et al. 2004). These leaves are therefore less palatable to insect herbivores and have less insect damage (Coley & Barone 1996; Royer et al. 2007). We estimated LMA for plant species from Menat and five North American sites using the methodology of Royer et al. (2007). An ANOVA of LMA by site yielded an F-value of 0.16 and p = 0.97 (five d.f.), indicating no significant differences in leaf properties (see table S2 and fig. S1 in the electronic supplementary material).

5. Discussion

Previous studies indicate that, in the majority of cases, plant and insect-feeding diversity on a per-leaf basis were high during the Cretaceous and low during the Palaeocene in the US Western Interior (e.g. Labandeira et al. 2002a,b; Wilf et al. 2006). The two remarkable exceptions, Mexican Hat and Castle Rock, show either rich and abundant insect feeding (in the former) or high floral diversity (in the latter), but not both. This indicates severe ecosystem depression and ecological imbalance throughout much of the Palaeocene in the US Western Interior. The exceptionally high floral diversity and DT richness at Menat argue for a balanced and fully functional middle Palaeocene ecosystem completely unlike any known from the US Palaeocene, even for Castle Rock, which grew under tropical rainforest-like conditions (Johnson & Ellis 2002; Ellis et al. 2003; Wilf et al. 2006). Furthermore, the high mining diversity is indicative of extensive host specialization on many different host species, such as C. macquarrii, which has 22 DTs coupled with an elevated mining activity.

The cause of the observed pattern is probably complex. Possible factors include reduced impact effects as distance from the Chicxulub crater in Mexico (Hildebrand & Boynton 1991) increases, a higher Cretaceous floral diversity in Europe, or higher Palaeocene immigration or origination rates. Further investigations of potential Palaeocene floras (e.g. Sézanne, Gelinden; Collinson & Hooker 2003) will be necessary to better characterize plant–insect associations following the K–T boundary in Europe, especially with respect to the specialized feeding groups. Suitable latest Cretaceous floras for comparison are not yet known. However, the Menat data are consistent with palaeobotanical findings from the early Palaeocene in Chubut, Argentina (7700 km modern distance from Chicxulub), and West Coast, New Zealand (12 300 km). Like Menat (8500 km), these areas are far from the impact site and show higher Palaeocene plant diversity (Iglesias et al. 2007) or a more rapid ecosystem recovery (Vajda et al. 2001) than occurring in the Western Interior USA (e.g. southwestern North Dakota, 3100 km) or is indicated by approximately 58 Ma Cerrejón flora of northern Colombia (2100 km; Wing et al. in press). Thus, the diversity of plants and plant–insect associations at Menat contributes to an emerging global pattern of more robust Palaeocene terrestrial ecosystems at great distance from the Chicxulub structure.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Carlos A. Jaramillo and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. This research received support from the SYNTHESYS Project (http://www.synthesys.info), which is financed by European Community Research Infrastructure Action under the Structuring the European Research Area Program (to T.W.), and a grant from the German Science Foundation (RU 665/4-1, 4-2, to J.R. and T.W.). Additional support was provided by the American Philosophical Society and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation (to P.W.) and by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (to E.D.C.). We especially thank Beth Ellis and Kirk Johnson for their untiring work on Cretaceous and Palaeogene floras in the Western Interior, supported by NSF grant EAR-0345910, to acquire data cited here.

References

- Akhmetiev M. A., Beniamovski V. N.2009Paleogene floral assemblages around epicontinental seas and straits in Northern Central Eurasia: proxies for climatic and paleogeographic evolution. Geol. Acta 7, 297–309 (doi:10.1344/105.000000278) [Google Scholar]

- Alroy J.1999The fossil record of North American mammals: evidence for a Paleocene evolutionary radiation. Syst. Biol. 48, 107–118 (doi:10.1080/106351599260472) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton M. J., Harper D. A. T.2009Introduction to paleobiology and the fossil record. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons [Google Scholar]

- Coley P. D., Barone J. A.1996Herbivory and plant defense in tropical forests. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 27, 305–335 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.305) [Google Scholar]

- Collinson M. E.2000Cenozoic evolution of modern plant communities and vegetation. In Biotic response to global change: the last 145 million years (eds Cluver S. J., Rawson P. F.), pp. 223–243 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Collinson M. E., Hooker J. J.2003Paleogene vegetation of Eurasia: framework for mammalian faunas. Deinsea 10, 41–83 [Google Scholar]

- Currano E. D.2009Patchiness and long-term change in early Eocene insect feeding damage. Paleobiology 35, 484–498 [Google Scholar]

- Currano E. D., Wilf P., Wing S. L., Labandeira C. C., Lovelock E. C., Royer D. L.2008Sharply increased insect herbivory during the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1960–1964 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0708646105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis B., Johnson K. R., Dunn R. E.2003Evidence for an in situ early Paleocene rainforest from Castle Rock, Colorado. Rocky Mount. Geol. 38, 73–100 (doi:10.2113/gsrocky.38.1.173) [Google Scholar]

- Fritel P. H.1903Histoire naturelle de la France, paléobotanique, 24 Paris, France: Les Fils d’Émile Deyrolle [Google Scholar]

- Hably L.2006Catalogue of the Hungarian Cenozoic leaf, fruit and seed floras from 1856 to 2005. Studia Bot. Hung. 37, 41–129 [Google Scholar]

- Heck K. L., van Belle G., Simberloff D.1975Explicit calculation of the rarefaction diversity measurement and the determination of sufficient sample size. Ecology 56, 1459–1461 (doi:10.2307/1934716) [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand A. R., Boynton W. V.1991Cretaceous ground zero. Nat. Hist. 6, 46–53 [Google Scholar]

- Hotton C. L.2002Palynology of the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary in central Montana: evidence for extraterrestrial impact as a cause of the terminal Cretaceous extinctions. Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Pap. 361, 473–501 [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias A., Wilf P., Johnson K. R., Zamuner A. B., Cúneo N. R., Matheos S. D., Singer B. S.2007A Paleocene lowland macroflora from Patagonia reveals significantly greater richness than North American analogs. Geology 35, 947–950 (doi:10.1130/G23889A.1) [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski D., Raup D. M.1995Selectivity of end-Cretaceous marine bivalve extinctions. Science 268, 389–391 (doi:10.1126/science.11536722) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. R.2002Megaflora of the Hell Creek and lower Fort Union formations in the western Dakotas: vegetational response to climate change, the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary event, and rapid marine transgression. Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Pap. 361, 329–391 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. R., Ellis B.2002A tropical rainforest in Colorado 1.4 million years after the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary. Science 296, 2379–2383 (doi:10.1126/science.1072102) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. R., Nichols D. J., Attrep M., Orth C. J.1989High-resolution leaf-fossil record spanning the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary. Nature 340, 708–711 (doi:10.1038/340708a0) [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. H., Manchester S. R., Dilcher D. L.1988Dryophyllum Debey ex Saporta, juglandaceous not fagaceous. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 56, 205–211 (doi:10.1016/0034-6667(88)90059-0) [Google Scholar]

- Kedves M., Russell D. E.1982Palynology of the Thanetian layers of Menat. The geology of the Menat Basin, France. Palaeontographica Abt. B 182, 87–150 [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch E., Kvaček Z.1965Byttneriophyllum tiliaefolium (Al. Braun) Knobloch et Kvaček in den tertiären Floren der Nordhalbkugel. Sbor. Geol. Ved. Paleontol. 5, 123–166 [Google Scholar]

- Kvaček Z., Walther H.1989Revision der mitteleuropäischen tertiären Fagaceen nach blattepidermalen Charakteristiken. III Teil: Dryophyllum Debey ex Saporta und Eotrigonobalanus Walther & Kvaček gen. nov. Feddes Repert. 100, 575–601 [Google Scholar]

- Labandeira C. C., Johnson K. R., Lang P.2002aA preliminary assessment of insect herbivory across the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary: extinction and minimal rebound. Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Pap. 361, 297–327 [Google Scholar]

- Labandeira C. C., Johnson K. R., Wilf P.2002bImpact of the terminal Cretaceous event on plant–insect associations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2061–2066 (doi:10.1073/pnas.042492999) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labandeira C. C., Wilf P., Johnson K. R., Marsh F.2007Guide to insect (and other) damage types on compressed plant fossils, Version 3.0 Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; (http://paleobiology.si.edu/insects/index.html). [Google Scholar]

- Laurent L.1912Flore fossile des schistes de Menat (Puy-de-Dôme). Ann. Mus. Hist. Nat. Marseille 14, 1–246 [Google Scholar]

- Laurent L.1919Addition à la flore des schistes de Menat. Ann. Mus. Hist. Nat. Marseille 17, 1–8 [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod K., Whiteny D. L., Huber B. T., Koeberl C.2006Impact and extinction in remarkably complete Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary sections from Demerara Rise, tropical western North Atlantic. Geol. Soc. Am. B 119, 101–115 (doi:10.1130/B25955.1) [Google Scholar]

- Mai D. H.1995Tertiäre Vegetationsgeschichte Europas Jena, Germany: Gustav Fischer [Google Scholar]

- Manchester S. R.1989Early history of the Juglandaceae. Plant Syst. Evol. 162, 231–250 (doi:10.1007/BF00936919) [Google Scholar]

- Nichols D. J.2002Palynology and palynostratigraphy of the Hell Creek formation in North Dakota: a microfossil record of plants at the end of Cretaceous time. Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Pap. 361, 393–456 [Google Scholar]

- Nichols D. J., Johnson K. R.2008Plants and the K–T boundary. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Novotny V., et al. 2007Low beta diversity of herbivorous insects in tropical forests. Nature 448, 692–695 (doi:10.1038/nature06021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson D. A., Schaefer T., Johnson K. R., Nichols D. J., Hunter J. P.2002Vertebrate biostratigraphy of the Hell Creek formation in southwestern North Dakota and northwestern South Dakota. Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Pap. 361, 145–167 [Google Scholar]

- Pigg K. B., Dillhoff R. M., DeVore M. L., Wehr W. C.2007New diversity among the Trochodendraceae from the early/middle Eocene Okanogan Highlands of British Columbia, Canada, and northeastern Washington State, United States. Int. J. Plant Sci. 168, 521–532 (doi:10.1086/512104) [Google Scholar]

- Piton E.1940Paléontologie du gisement Éocène de Menat (Puy-de-Dôme), flore et faune. Mém. Soc. His. Nat. Auvergne 1, 1–303 [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team 2008R: a language and environment, v. 2.8.1 Vienna, Austria: The R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- Royer D. L., et al. 2007Fossil leaf economics quantified: calibration, Eocene case study, and implications. Paleobiology 33, 574–589 (doi:10.1666/07001.1) [Google Scholar]

- Tiffney B. H., Manchester S. R.2001The use of geological and paleontological evidence in evaluating plant phylogeographic hypotheses in the Northern Hemisphere Tertiary. Int. J. Plant Sci. 162, S3–S17 (doi:10.1086/323880) [Google Scholar]

- Tschudy R. H., Pillmore C. L., Orth C. J., Gilmore J. S., Knight J. D.1984Disruption of the terrestrial plant ecosystem at the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary, Western Interior. Science 225, 1030–1032 (doi:10.1126/science.225.4666.1030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vajda V., Raine J. I., Hollis C. J.2001Indication of global deforestation at the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary by New Zealand fern spike. Science 294, 1700–1702 (doi:10.1126/science.1064706) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent P. M., Aubert M., Boivin P., Cantagrel J. M., Lenat F.1977Découverte d'un volcanisme Paleocène en Auvergne: les maars de Menat et leurs annexes; étude géologique et géophysique. B. Soc. Géol. Fr. 19, 1067–1070 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Dilcher D. L., Lott T. A.2007Podocarpium A. Braun ex Stizenberger 1851 from the middle Miocene of Eastern China, and its palaeoecology and biogeography. Acta Palaeobot. 47, 237–251 [Google Scholar]

- Wilf P.2008Insect-damaged fossil leaves record food web response to ancient climate change and extinction. New Phytol. 178, 486–502 (doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02395.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilf P., Johnson K. R.2004Land plant extinction at the end of the Cretaceous: a quantitative analysis of the North Dakota megafloral record. Paleobiology 30, 347–368 (doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0347:LPEATE>2.0.CO;2) [Google Scholar]

- Wilf P., Labandeira C. C.1999Response of plant–insect associations to Paleocene–Eocene warming. Science 284, 2153–2156 (doi:10.1126/science.284.5423.2153) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilf P., Johnson K. R., Cúneo N. R., Smith M. E., Singer B. S., Gandolfo M. A.2005Eocene plant diversity at Laguna del Hunco and Río Pichileufú, Patagonia, Argentina. Am. Nat. 165, 634–650 (doi:10.1086/430055) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilf P., Labandeira C. C., Johnson K. R., Ellis B.2006Decoupled plant and insect diversity after the end-Cretaceous extinction. Science 313, 1112–1115 (doi:10.1126/science.1129569) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing S. L., Alroy J., Hickey L. J.1995Plant and mammal diversity in the Paleocene to early Eocene of the Bighorn Basin. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 115, 117–155 (doi:10.1016/0031-0182(94)00109-L) [Google Scholar]

- Wing S. L., DiMichele W. A.1995Conflict between local and global changes in plant diversity through geological time. Palaios 10, 551–564 (doi:10.2307/3515094) [Google Scholar]

- Wing S. L., Herrera F., Jaramillo C. A., Gómez-Navarro C., Wilf P., Labandeira C. C.In press The earliest fossil record of Earth's most diverse biome: a late Paleocene neotropical rainforest from the Cerrejón formation, Colombia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J. A.1985Distribution of major vegetational types during the Tertiary. In The carbon cycle and atmospheric CO2: natural variations Archean to present, vol. 32 (eds Sundquist E. T., Broecker W. S.), pp. 357–375 Geophysical Monography Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J. A., Upchurch G. R.1986Vegetation, climatic and floral changes at the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary. Nature 324, 148–152 (doi:10.1038/324148a0) [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J. A., Wehr W. C.1987Middle Eocene dicotyledonous plants from Republic, northeastern Washington. US Geol. Surv. B 1597, 1–25 [Google Scholar]

- Wright I. J., et al. 2004The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428, 821–827 (doi:10.1038/nature02403) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]