Abstract

Scaridae (parrotfishes) is a prominent clade of 96 species that shape coral reef communities worldwide through their actions as grazing herbivores. Phylogenetically nested within Labridae, the profound ecological impact and high species richness of parrotfishes suggest that their diversification and ecological success may be linked. Here, we ask whether parrotfish evolution is characterized by a significant burst of lineage diversification and whether parrotfish diversity is shaped more strongly by sexual selection or modifications of the feeding mechanism. We first examined scarid diversification within the greater context of labrid diversity. We used a supermatrix approach for 252 species to propose the most extensive phylogenetic hypothesis of Labridae to date, and time-calibrated the phylogeny with fossil and biogeographical data. Using divergence date estimates, we find that several parrotfish clades exhibit the highest diversification rates among all labrid lineages. Furthermore, we pinpoint a rate shift at the shared ancestor of Scarus and Chlorurus, a scarid subclade characterized by territorial behaviour and strong sexual dichromatism, suggesting that sexual selection was a major factor in parrotfish diversification. Modifications of the pharyngeal and oral jaws that happened earlier in parrotfish evolution may have contributed to this diversity by establishing parrotfishes as uniquely capable reef herbivores.

Keywords: diversification rate, functional morphology, Labridae, phylogenetic analysis, Scaridae, sexual selection

1. Introduction

Coral reefs are renowned for their biodiversity, an abundance that is shared across many lineages that live on reefs. However, little is known about what factors have shaped patterns of diversification of reef organisms. There is some evidence that living on coral reefs can itself spur diversification (Alfaro et al. 2007), possibly because of opportunities presented by the rich niche diversity inherent on reefs or strong community interactions among the inhabitants. Innovation and radiation of functional systems have also been implicated in lineage diversification. Toxin diversification facilitated by gene duplications and its link to trophic evolution, for example, have played an important role in the remarkable radiation of Conus gastropods (Duda & Palumbi 1999). Furthermore, factors that result in rapid reproductive isolation between populations can contribute to the diversification of reef organisms. Shifts in Conus from having planktonic dispersing larvae to direct development, for example, are associated with a recent radiation of over 30 species endemic to the Cape Verde Islands (Duda & Rolan 2005). In addition, pronounced colour differences between closely related species of reef fishes (Taylor & Hellberg 2005) and strong sexual dichromatism observed in many groups of reef fishes suggest the possibility of a link between colour, species recognition and mate choice. Taxa with stronger patterns of sexual selection have frequently been shown to be more species rich than their sister groups (Coyne & Orr 2004), but tests of the effect of sexual selection on patterns of diversification of major reef clades have not been performed.

In this paper, we explore the tempo of diversification in parrotfishes (Scaridae), a monophyletic group of 96 teleost species that are prominent inhabitants of coral reefs around the world. A series of functional innovations in their feeding mechanism allow parrotfishes to scrape algae from the surface of hard substrates and to pulverize and digest the mixture of algae, bacteria, detritus, benthic invertebrates, dead coral skeletons and sand (Clements & Bellwood 1988; Gobalet 1989; Bellwood 1994; Wainwright et al. 2004). Feeding activities make scarids some of the ecologically most important fishes on modern coral reefs (Bellwood 1995; Hughes et al. 2007; Hoey & Bellwood 2008). Scarids are phylogenetically nested within Labridae (Westneat & Alfaro 2005), a clade of about 600 species of reef fishes that exhibit an exceptional diversity in body size, shape, coloration, feeding habits, reproductive behaviours and life histories (Wainwright et al. 2004; Westneat & Alfaro 2005). While previous phylogenetic studies of parrotfishes have noted that they exhibit a high species richness that is recently derived (Streelman et al. 2002; Smith et al. 2008), the possibility of diversification rate shifts within parrotfishes has not been thoroughly investigated.

We focus on a series of questions about the diversification of parrotfishes. First, we examine scarid diversification in the greater context of labrid diversity. To this end, we perform a supermatrix analysis that combines published and unpublished DNA sequence data sampled across and within labrid clades. The resulting phylogenetic hypothesis includes by a factor of three the largest number of labrid taxa sampled in an analysis and better represents the diversity of the group at all phylogenetic levels. We employ existing fossil and biogeographical calibrations to estimate divergence times of labrid lineages. Using this time-calibrated phylogeny, we scan Labridae for clades that are significantly more diverse than expected, given the age of the clade and a net diversification rate that we calculate for labrids as a whole. This analysis shows that some scarid clades exhibit significantly greater diversity than expected and raises the possibility of a diversification rate shift within parrotfishes. Then we ask whether and where this shift has occurred within Scaridae, which could reveal if high parrotfish diversity is most closely tied to one of three key transitions that have happened in parrotfish history: (i) the origin of the modified pharyngeal jaw apparatus that distinguishes scarids from the rest of labrids and allows them to pulverize the mixture of algae and rock that they feed on; (ii) the origin of the beak-like jaw and modified dental and muscular structures that enable some parrotfish to feed on rocky substrates; or (iii) the origin of strong sexual dichromatism that characterizes a large scarid subclade.

2. Material and methods

(a). Phylogenetic analysis

Parrotfishes, along with Odacidae (weed-whitings), are phylogenetically nested within Labridae (Clements et al. 2004; Westneat & Alfaro 2005). Accordingly, the ingroup of our study consists of representatives of all these groups. We estimated phylogenetic relationships among 252 species of labrids and an outgroup set of 24 species representing Cichlidae, Pomacentridae, Embiotocidae and other perciform groups using both published and unpublished DNA sequence data. We downloaded published sequences of nuclear genes RAG2, TMO-4C4 and S7, mitochondrial genes COI and cytb and ribosomal RNA genes 16S and 12S from GenBank (table S1, electronic supplementary material) using Phyutility (Smith & Dunn 2008). With novel S7 sequences from 10 wrasse species and COI sequences from 26 wrasse and two parrotfish species (table S1, electronic supplementary material), about 54 per cent of all species–marker combinations in the supermatrix are sampled (table S2, electronic supplementary material). To obtain novel sequences, we isolated DNA from tissues of field-collected specimens following the standard protocol of QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit. Using isolated DNA as a template, we amplified COI and S7 genes in separate polymerase chain reactions (PCRs). We cleaned PCR products with QIAGEN PCR Purification Kit and used it as a template in DNA sequencing reactions. In PCR and DNA sequencing reactions, we used universal primers for S7 (Chow & Hazama 1998) and COI (Folmer et al. 1994).

We aligned sequences from each marker separately using Muscle (Edgar 2004) and omitted sequences that could not be unambiguously aligned with the rest of sequences after controlling for GenBank errors (e.g. reverse-complemented nucleotides). In the case of multiple sequences from the same species, we used the sequence with greatest overlap with the rest of sequences. We trimmed flanking regions that contained sequences from less than about 50 per cent of taxa in the alignment. Finally, we concatenated nucleotide marker datasets into a supermatrix using Phyutility (Smith & Dunn 2008). The supermatrix alignment is available as electronic supplementary material. We partitioned the supermatrix by individual molecular markers and performed a maximum-likelihood (ML) analysis implemented in RAxML (Stamatakis 2006). Adopting different data partitioning schemes resulted in trees that differed only in species-level relationship that are poorly resolved and did not affect the results significantly. We performed both a bootstrap analysis under a GTR + CAT model with 500 pseudoreplicates and 200 independent ML estimates under a GTR + MIX model and used the phylogenetic tree with the best likelihood score for further analyses (electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

(b). Node calibrations

Labridae is characterized by an overall paucity of fossil taxa that can reliably be used to calibrate molecular phylogenies. Our examination of the literature pointed out three fossil labrid taxa that are phylogenetically resolved, as well as a biogeographical calibration point. We present the details of these calibrations as electronic supplementary material.

(c). Divergence date estimates

We estimated labrid divergence dates using two methods that accommodate molecular evolutionary rate variation among lineages. In both analyses, we used the ML tree inferred by RAxML (Stamatakis 2006), but excluded the outgroup to estimate divergence times only for sampled labrid, scarid and odacid lineages. The non-parametric rate smoothing (NPRS) method, implemented in r8s v. 1.70 (Sanderson 2003), relaxes the assumption of a molecular clock by a least squares smoothing of substitution rates (Sanderson 1997). Estimating divergence dates using the NPRS method requires at least one hard age constraint. Therefore, in addition to minimum age constraints of fossil data, we assumed that the closure of the Isthmus of Panama caused the split of geminate species Halichoeres dispilus and Halichoeres pictus and constrained minimum and maximum ages for the most-recent common ancestor (MRCA) of these species to 3.1 and 3.5 Myr ago, respectively.

The second model of diversification rate heterogeneity, the uncorrelated lognormal (UCLN) model, samples substitution rates independently from a lognormal distribution (Drummond et al. 2006) and is implemented in BEAST v. 1.4.8 (Drummond & Rambaut 2007). We assumed that the UCLN model best explains the diversification rate heterogeneity in labrids. A BEAST analysis where we used the same partitioning scheme as the RAxML analysis failed to converge despite multiple runs of at least 10 million generations each, possibly owing to the high amount of missing data in some partitions. Therefore, we estimated the posterior probability density of divergence times by an unpartitioned BEAST analysis using a GTR + GAMMA nucleotide substitution model with four rate categories, and a birth–death process as the prior for speciation. As the RAxML analysis produced a tree topology that is highly congruent with previous phylogenetic hypotheses on labrids, we fixed the topology and used BEAST to estimate divergence times only. We performed eight separate runs of the BEAST analysis for 30 million generations each, and combined the results using the accompanying program, BEAUti.

Because a diversification event is most likely to have occurred some time before the age of the oldest fossil dating the node, we used lognormal priors for fossil calibrations (Ho 2007), with zero offset values reflecting conservative estimates of fossil ages. We present details of these priors in the supplementary material.

(d). Analyses of diversity and diversification rates

First, we examined parrotfish diversity within the greater radiation of Labridae. Here, we used Magallon and Sanderson's method (2001), implemented in the R programming language (R Development Core Team 2005) package ‘geiger’ (Harmon et al. 2008), to calculate a net diversification rate for labrids as a whole, given an extant diversity and the estimated age of Labridae. We used this diversification rate to determine the 95 per cent confidence interval (CI) around the expected species diversity for a clade of a given stem age that has diversified with a constant rate. We plotted species richness of various labrid clades as a function of their stem ages and compared their diversities to the 95 per cent CI for the corresponding stem age. As many labrid species were not sampled in this study, we analysed only those clades where we can confidently assign the unsampled extant diversity. We assigned species totals to clades following FishBase (http://www.fishbase.org). Specifically, we included genera with no evidence for paraphyly (e.g. Scarus) and clades that consist of monophyletic genera (e.g. Scarus + Chlorurus). We also analysed some strongly supported clades that contain paraphyletic genera, but only if all sampled species of those genera are grouped in the clade (e.g. Thalassoma + Gomphosus). Furthermore, we placed diversities of several unsampled labrid genera according to available phylogenetic information. Six genera with a total of six species where no reliable information was available regarding their phylogenetic placement were excluded from the analysis (table S3, electronic supplementary material).

Second, we tested whether and where a shift in diversification rate has occurred within parrotfishes by comparing the likelihood of observing the data under a constant-rate model to the likelihood under a rate-shift model. Here, we used a genus-level phylogeny of Scaridae by excluding all non-scarid lineages from the time-calibrated labrid phylogeny and trimming all but one representative species from each scarid genus. As all scarid genera appear to be monophyletic, we assigned the number of extant species to each genus following FishBase (http://www.fishbase.org). We used the R package ‘LASER’ (Rabosky 2006) to fit a constant-rate and two-rate diversification model on the time-calibrated, genus-level scarid phylogeny. The two-rate model creates tree bipartitions using each node in turn and finds the ML estimate of the rate for each partition using taxonomic and phylogenetic data (Rabosky et al. 2007). The bipartitioning scheme that gives the highest likelihood denotes the estimated location of the rate shift. Furthermore, we predicted an increase in the diversification rate at the base of the clade consisting of Scarus and Chlorurus, and also tested the alternative hypothesis of an ancestrally increased diversification rate and a subsequent decrease in some other scarid clade or clades. To this end, we used a constrained version of the two-rate model (‘rate-decrease model’), where the highest diversification rate must occur in the tree bipartition containing the root node, and therefore, in this case, no rate increase is allowed on the path from the root to the Scarus + Chlorurus clade (Rabosky et al. 2007).

Finally, we used SymmeTree (Chan & Moore 2005) to scan the parrotfish tree topology for significantly imbalanced partitions and to locate a shift in diversification rate. We incorporated the true parrotfish diversity into the analysis by coding incompletely sampled parrotfish genera as a polytomy of the complete diversity and resolving it with the taxon-size sensitive equal-rates Markov model using 107 random resolutions. Again, we assigned extant diversity to parrotfish clades following FishBase (http://www.fishbase.org). Finally, we used 106 simulated trees to build a null distribution and test for significance of the results.

Except for the SymmeTree analysis, we repeated all diversification rate analyses for both NPRS and BEAST divergence date estimates and under extreme relative extinction rates (ε; extinction rate/speciation rate), ε = 0 and ε = 0.9. Changes in ε are irrelevant to SymmeTree.

3. Results

(a). Phylogenetic relationships and divergence date estimates of Labridae

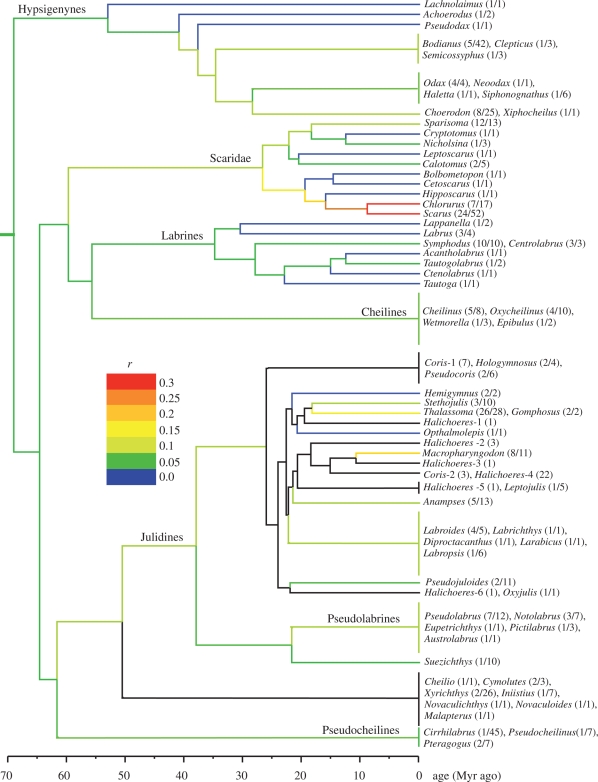

The analysis of 252 labrids plus outgroup taxa resulted in a phylogenetic tree and divergence date estimates that are mostly congruent with recent hypotheses for Labridae (figure 1). All major clades presented in figure 1, with the exception of Xyrichthys and related genera, are resolved with moderate to well support. To focus on parrotfish diversification, we present phylogenetic relationships and date estimates that are novel or differ from those presented in past studies, as well as a phylogenetic tree with bootstrap support, as electronic supplementary material.

Figure 1.

The genus-level phylogenetic hypothesis for Labridae, time-calibrated using the NPRS method. The width of vertical lines at the tips of the tree does not correspond to species richness of clades. Diversification rates for black clades are not calculated, as their extant diversities could not be confidently assigned. Tip labels denote genus names with the proportion of sampled species in brackets (sampled/total). A single number in brackets given for some paraphyletic genera denotes the number of sampled species. r is the lineage diversification rate calculated using Magallon and Sanderson's method (2001) at ε = 0.

(b). Parrotfishes within the greater labrid radiation

Diversification rate estimates suggest that Scaridae represents a major diversification event within Labridae (figure 1). Accordingly, among labrid lineages we investigated, we found the highest diversification rate within reef-associated parrotfishes, especially in the clade that consists of two of the most diverse parrotfish genera, Scarus and Chlorurus (figure 1). We estimate that the diversification rate increased twofold (ε = 0.9) to about threefold (ε = 0) in this clade compared with that calculated for Labridae as a whole (table 1) using Magallon and Sanderson's method (2001). Similarly, we find that Scarus and Scarus + Chlorurus are significantly more diverse than expected under the diversification rate calculated for labrids, although the significance of the latter disappears at high extinction using BEAST divergence date estimates (figure 2).

Table 1.

Diversification rates for Labridae and the clade consisting of Scarus and Chlorurus, estimated with Magallon & Sanderson's method (2001), at low (ε = 0) and high (ε = 0.9) extinction rates and using both BEAST and NPRS age estimates.

| Labridae |

Scarus + Chlorurus |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPRS | BEAST | NPRS | BEAST | |

| ε = 0 | 0.084 | 0.104 | 0.267 | 0.261 |

| ε = 0.9 | 0.060 | 0.074 | 0.130 | 0.127 |

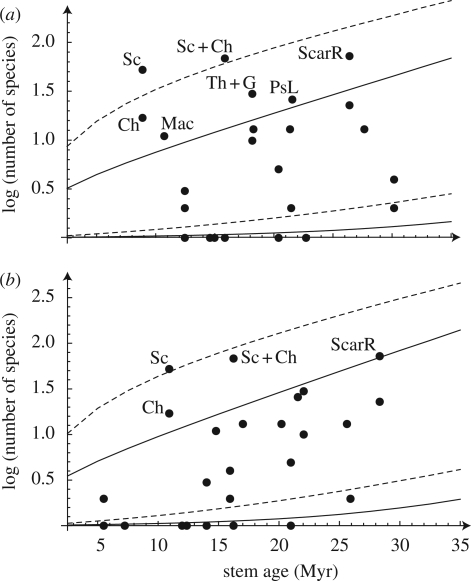

Figure 2.

Diversities of all terminal clades in figure 1, to which extant diversity could be assigned, compared with the 95 per cent CI of expected diversity for a clade of a given stem age diversifying under a constant diversification rate. Diversification rates are calculated using Magallon and Sanderson's method (2001) at ε = 0 (solid line) and ε = 0.9 (dashed line) for (a) NPRS age estimates and (b) BEAST age estimates. The reef clade and the seagrass clade of parrotfishes, in which terminal parrotfish clades are nested, are also included in the analysis. Diversities of terminal clades that are older than 35 Myr and found to be non-significant (e.g. Lachnolaimus) are not shown. Labels correspond to: Sc, Scarus; Ch, Chlorurus; Sc + Ch, the clade consisting of Scarus and Chlorurus; ScarR, reef clade of parrotfishes; Th + G, the clade consisting of Thalassoma and Gomphosus; PsL, Pseudolabrines; Mac, Macropharyngodon. Diversities of clades that are not labelled are found to be non-significant.

(c). Patterns of diversification within parrotfishes

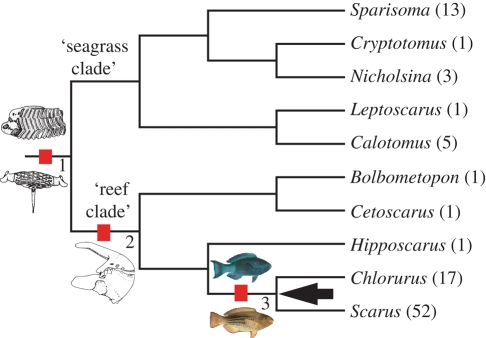

We find that a two-rate model of diversification fits the data significantly better, and thus reject the null hypothesis that parrotfishes diversified at a constant rate (p < 0.001; table 2). Furthermore, the MRCA of Scarus and Chlorurus is the ML estimate of the diversification rate shift point (figure 3), for both NPRS and BEAST age estimates and at low and high extinction rates (table 2). Our estimates indicate that Scarus and Chlorurus diversified at a rate that is about four (ε = 0) to nine (ε = 0.9) times greater than the rest of parrotfishes, using NPRS estimates (table 2) and a rate estimator that combines taxonomic and phylogenetic data (Rabosky et al. 2007). We did not find support for the alternative hypothesis that Scarus and Chlorurus retained an ancestrally high rate of diversification, while some other clade or clades experienced a decreased rate, as indicated by the high Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) score of the rate-decrease model relative to the two-rate model (table 2). Finally, analysis of the tree topology using SymmeTree confirmed these results and pointed to the MRCA of Scarus and Chlorurus as the location of the rate shift (p < 0.01; figure 3).

Table 2.

Model-based analysis of diversification rates in parrotfishes shows that the two-rate model explains the data best. MRCA of Scarus and Chlorurus is found as the ML estimate of the location of the rate shift. ΔAIC denotes the difference between the AIC score of a model and the overall best-fitting model. rR and rNR are the diversification rates of the tree partition that does and does not include the root, respectively. Diversification rates are estimated with a method that combines taxonomic and phylogenetic data (Rabosky et al. 2007).

| constant-rate log L (ΔAIC) |

two-rate log L (ΔAIC) |

rate-decrease log L (ΔAIC) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| model | NPRS | BEAST | NPRS | BEAST | NPRS | BEAST |

| ε = 0 | −62.8 (26.3) | −59.4 (19.7) | −47.7 (0) | −47.6 (0) | −56.8 (18.3) | −54.1 (13.1) |

| parameters | rR = 0.193 | rR = 0.171 | rR = 0.093; rNR = 0.4 | rR = 0.088; rNR = 0.324 | rR = 0.254; rNR = 0.1 | rR = 0.224; rNR = 0.092 |

| ε = 0.9 | −59.1 (13.5) | −58.0 (11.0) | −50.4 (0) | −50.5 (0) | −53.7 (6.6) | −53.3 (5.7) |

| parameters | rR = 0.062 | rR = 0.054 | rR = 0.018; rNR = 0.168 | rR = 0.017; rNR = 0.134 | rR = 0.074; rNR = 0.001 | rR = 0.063; rNR = 0.001 |

Figure 3.

A phylogeny of Scaridae. Tip labels denote genus names with species totals in brackets. The arrow points to the inferred location of the rate shift. Pictures on branches represent important transitions in the evolutionary history of parrotfishes, rather than hypothesized ancestral states. These are: (i) modified pharyngeal jaw apparatus (from Leptoscarus vaigiensis) shared by all parrotfishes; (ii) modifications in the oral jaw and teeth structure (from Scarus psittacus) shared by the reef scarids; and (iii) pronounced sexual dichromatism (male and female Scarus frenatus) characterizing a subclade of reef scarids. Drawings of pharyngeal and oral jaws and pictures of S. frenatus are taken with permission from Bellwood (1994) and FishBase (www.fishbase.org), respectively.

4. Discussion

The high diversification rate within parrotfishes compared with the rest of labrids (figure 1) and diversity observed in some parrotfish clades that is greater than expected under a constant rate (figure 2), raise the possibility of a significant diversification rate shift in Scaridae. Accordingly, we confirm a significantly increased diversification rate in parrotfishes, specifically, at the node that corresponds to the MRCA of the reef-associated genera Scarus and Chlorurus (table 2; figure 3). Members of Scarus and Chlorurus, which account for about 75 per cent of all parrotfishes, are characterized by territorial and haremic behaviour, diandry and pronounced sexual dichromatism (Robertson & Warner 1978; Streelman et al. 2002), factors that may contribute to reproductive isolation and lead to accelerated diversification (Panhuis et al. 2001; Coyne & Orr 2004; Mank 2007). Consequently, inferred location of the rate shift suggests that strong sexual selection, rather than key morphological innovations, has played the major role in parrotfish diversification (figure 3).

It is important to note, however, that morphological modifications in pharyngeal and oral jaws, teeth and its associated musculature (Gobalet 1989; Bellwood 1994) that occurred earlier in parrotfish history (figure 3) may also have indirectly contributed to the burst of diversification in Scarus and Chlorurus. These morphological transitions manifest themselves as specialized feeding habits and, consequently, a strong preference for reef habitats in some parrotfish (Bellwood & Schultz 1991). Growing evidence suggests that habitat can strongly influence patterns of speciation through sexual selection (Orr & Smith 1998). In this case, a reef habitat may have offered greater opportunities for territorial and haremic behaviour and, consequently, stronger sexual selection, owing to its greater habitat complexity (Gratwicke & Speight 2005) and the high abundance of structures that can be used as territory landmarks or specific spawning locations that can be monopolized (Petersen & Warner 2002).

Sexual selection may have contributed to the diversification of other labrid lineages as well. An interesting case is the parrotfish genus Sparisoma that is nested within the seagrass clade (figure 3). This group represents a separate origin of the beak-like jaw formed from coalesced teeth that is similar to reef scarids (Streelman et al. 2002). Members of Sparisoma exhibit both reef and seagrass association and feeding modes of scraping, excavating and browsing (Bellwood 1994). In addition, some Sparisoma species resemble reef scarids through their territorial and haremic behaviour and pronounced sexual dichromatism (Robertson & Warner 1978). As Sparisoma is the only scarid genus, other than Scarus and Chlorurus, that has more than a few species, it is possible that sexual selection has contributed to the diversity of this clade. However, Sparisoma exhibits neither a significant diversification rate (figure 1) nor diversity (figure 2), suggesting that the effect of sexual selection has been weaker in this clade than in Scarus and Chlorurus. Furthermore, differences in the evolutionary histories of these clades that, according to our estimates, have diverged about 30 Myr ago, may also have contributed to patterns of diversity. For example, in contrast to Scarus and Chlorurus that have probably originated in the Indo-Pacific (Streelman et al. 2002), parrotfishes of Sparisoma are found mainly in the Caribbean, a region with a very different history such as a recent mass extinction (Jackson et al. 1996).

Several caveats need to be kept in mind while interpreting our findings. First, the phylogenetic placement of species that we have not sampled could possibly alter stem age estimates and species richness of some labrid clades. Second, the amount of missing data in the supermatrix could introduce branch length variation and, consequently, further affect divergence date and diversification rate estimates. Parrotfish clades, however, are fairly well sampled and strongly resolved as monophyletic. Furthermore, our divergence date estimates of both BEAST and NPRS are mostly congruent with previous studies on Labridae. Consequently, despite possible effects of taxonomic sampling and missing data, we expect our central conclusions on parrotfish diversification to be robust.

In summary, we showed that parrotfishes represent a major diversification event within Labridae. Furthermore, the location of this increase in diversification rate is consistent with a major impact of strong sexual selection, but we also suggest that morphological innovations in scarid feeding mechanisms may have caused strong habitat preferences and worked synergistically to make parrotfish particularly successful on reefs, while strong patterns of mate choice increased the rate of reproductive isolation, and hence, diversification. In a group such as Labridae with impressive biological diversity and complex biogeographical history, it may not be uncommon that multiple factors work together to result in observed patterns of diversification. The phylogenetic framework and results we present in this paper represent an important step to elucidate these patterns and to understand the underlying complex evolutionary processes.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript. This research was supported by Yale University EEB Chair's Discretionary Fund to E.K. and NSF awards DEB-0717009 to T.J.N. and DEB-0716155 to P.C.W.

References

- Alfaro M. E., Santini F., Brock C. D.2007Do reefs drive diversification in marine teleosts? Evidence from the pufferfish and their allies (order Tetraodontiformes). Evolution 61, 2104–2126 (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00182.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellwood D. R.1994A phylogenetic study of the parrotfishes family Scaridae (Pisces : Labroidei), with a revision of genera. Rec. Aust. Mus. 20(Suppl.), 1–86 [Google Scholar]

- Bellwood D. R.1995Carbonate transport and within reef patterns of bioerosion and sediment release by parrotfishes (family Scaridae) on the Great Barrier reef. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 117, 127–136 (doi:10.3354/meps117127) [Google Scholar]

- Bellwood D. R., Schultz O.1991A review of the fossil record of the parrotfishes with a description of a new Calotomus species from the Middle Miocene of Austria. Annalen Naturhistorisches Museum Wien 92, 55–71 [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. M. A., Moore B. R.2005SymmeTree: whole-tree analysis of differential diversification rates. Bioinformatics 21, 1709–1710 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti175) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow S., Hazama K.1998Universal PCR primers for S7 ribosomal protein gene introns in fish. Mol. Ecol. 7, 1255–1256 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements K. D., Bellwood D. R.1988A comparison of the feeding mechanisms of two herbivorous labroid fishes, the temperate Odax pullus and the tropical Scarus rubroviolaceus. Aust. J. Mar. Freshwater Res. 39, 87–107 (doi:10.1071/MF9880087) [Google Scholar]

- Clements K. D., Alfaro M. E., Fessler J. L., Westneat M. W.2004Relationships of the temperate Australasian labrid fish tribe Odacini (Perciformes: Teleostei). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 32, 575–587 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.02.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne J. A., Orr H. A.2004Speciation Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J., Rambaut A.2007BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-214) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J., Ho S. Y. W., Phillips M. J., Rambaut A.2006Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 4, 699–710 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda T. F., Palumbi S. R.1999Developmental shifts and species selection in gastropods. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 10 272–10 277 (doi:10.1073/pnas.96.18.10272) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda T. F., Rolan E.2005Explosive radiation of Cape Verde Conus, a marine species flock. Mol. Ecol. 14, 267–272 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02397.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C.2004MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (doi:10.1093/nar/gkh340) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer O., Black M., Hoeh W., Lutz R., Vrijenhoek R.1994DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 3, 294–299 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobalet K. W.1989Morphology of the parrotfish pharyngeal jaw apparatus. Am. Zool. 29, 319–331 [Google Scholar]

- Gratwicke B., Speight M. R.2005The relationship between fish species richness, abundance and habitat complexity in a range of shallow tropical marine habitats. J. Fish Biol. 66, 650–667 (doi:10.1111/j.0022-1112.2005.00629.x) [Google Scholar]

- Harmon L. J., Weir J. T., Brock C. D., Glor R. E., Challenger W.2008GEIGER: investigating evolutionary radiations. Bioinformatics 24, 129–131 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm538) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S. Y. W.2007Calibrating molecular estimates of substitution rates and divergence times in birds. J. Avian Biol. 38, 409–414 [Google Scholar]

- Hoey A. S., Bellwood D. R.2008Cross-shelf variation in the role of parrotfishes on the Great Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs 27, 37–47 (doi:10.1007/s00338-007-0287-x) [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T. P., et al. 2007Phase shifts, herbivory, and the resilience of coral reefs to climate change. Curr. Biol. 17, 360–365 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.049) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J. B. C., Budd A. F., Coates A. G. (eds) 1996Evolution and environment in tropical America Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press [Google Scholar]

- Magallon S., Sanderson M. J.2001Absolute diversification rates in angiosperm clades. Evolution 55, 1762–1780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mank J. E.2007Mating preferences, sexual selection and patterns of cladogenesis in ray-finned fishes. J. Evol. Biol. 20, 597–602 (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01251.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr M. R., Smith T. B.1998Ecology and speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 502–506 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01511-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panhuis T. M., Butlin R., Zuk M., Tregenza T.2001Sexual selection and speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 364–371 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02160-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen C. W., Warner R. R.2002The ecological context of reproductive behavior. In Coral reef fishes: dynamics and diversity in a complex ecosystem (ed. Sale P. F.), pp. 103–118 New York, NY: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team 2005R: a language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- Rabosky D. L.2006LASER: a maximum likelihood toolkit for detecting temporal shifts in diversification rates from molecular phylogenies. Evol. Bioinform. Online 2, 257–260 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabosky D. L., Donnellan S. C., Talaba A. L., Lovette I. J.2007Exceptional among-lineage variation in diversification rates during the radiation of Australia's most diverse vertebrate clade. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 2915–2923 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0924) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D. R., Warner R. R.1978Sexual patterns in the labroid fishes of the Western Caribbean, II: the parrotfishes (Scaridae). Smithsonian Contrib. Zool 255, 1–26 [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson M. J.1997A nonparametric approach to estimating divergence times in the absence of rate constancy. Mol. Biol. Evol. 14, 1218–1231 [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson M. J.2003r8s: inferring absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times in the absence of a molecular clock. Bioinformatics 19, 301–302 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.301) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. A., Dunn C. W.2008Phyutility: a phyloinformatics tool for trees, alignments and molecular data. Bioinformatics 24, 715–716 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm619) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L. L., Fessler J. L., Alfaro M. E., Streelman J. T., Westneat M. W.2008Phylogenetic relationships and the evolution of regulatory gene sequences in the parrotfishes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 49, 136–152 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.06.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A.2006RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streelman J. T., Alfaro M., Westneat M. W., Bellwood D. R., Karl S. A.2002Evolutionary history of the parrotfishes: biogeography, ecomorphology, and comparative diversity. Evolution 56, 961–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. S., Hellberg M. E.2005Marine radiations at small geographic scales: speciation in neotropical reef gobies (Elacatinus). Evolution 59, 374–385 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright P. C., Bellwood D. R., Westneat M. W., Grubich J. R., Hoey A. S.2004A functional morphospace for the skull of labrid fishes: patterns of diversity in a complex biomechanical system. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 82, 1–25 (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2004.00313.x) [Google Scholar]

- Westneat M. W., Alfaro M. E.2005Phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history of the reef fish family Labridae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 36, 370–390 (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.02.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]