Abstract

Monochamus alternatus is the longicorn beetle notorious as a vector of the pinewood nematode that causes the pine wilt disease. When two populations of M. alternatus were subjected to diagnostic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of four Wolbachia genes, only the ftsZ gene was detected from one of the populations. The Wolbachia ftsZ gene persisted even after larvae were fed with a tetracycline-containing diet for six weeks. The inheritance of the ftsZ gene was not maternal but biparental, exhibiting a typical Mendelian pattern. The ftsZ gene titres in homozygotic ftsZ+ insects were nearly twice as high as those in heterozygotic ftsZ+ insects. Exhaustive PCR surveys revealed that 31 and 30 of 214 Wolbachia genes examined were detected from the two insect populations, respectively. Many of these Wolbachia genes contained stop codon(s) and/or frame shift(s). Fluorescent in situ hybridization confirmed the location of the Wolbachia genes on an autosome. On the basis of these results, we conclude that a large Wolbachia genomic region has been transferred to and located on an autosome of M. alternatus. The discovery of massive gene transfer from Wolbachia to M. alternatus would provide further insights into the evolution and fate of laterally transferred endosymbiont genes in multicellular host organisms.

Keywords: Wolbachia, Monochamus alternatus, lateral gene transfer, pine wilt disease, cerambycid beetle, nematode

1. Introduction

Lateral, or horizontal, gene transfer is the exchange of genetic materials between phylogenetically distant, and reproductively and genetically isolated, organisms. Recent microbial genomic studies have established that lateral gene transfers are universally occurring among diverse bacteria and archea, contributing to the dynamic evolution of prokaryotic genomes (Ochman et al. 2000; Koonin et al. 2001). By contrast, lateral gene transfers in eukaryotes have been regarded as relatively rare. However, as more and more genomic sequences from diverse eukaryotes become available, it has become apparent that lateral gene transfers have also occurred in diverse eukaryotes (Andersson 2005; Keeling & Palmer 2008). Microbial endosymbionts form one of the principal sources of laterally transferred genes in eukaryotes. Some endosymbiotic bacteria inhabit host eukaryotic cells, enter into the germline, and are maternally transmitted to the next host generation through ooplasm. The constant and intimate contact between the eukaryotic host cells and inhabiting bacterial associates may predispose the exchange of genetic materials between the partners. Among insects and nematodes, Wolbachia endosymbionts have been identified as a major source of laterally transferred genes in their genomes (Kondo et al. 2002b; Fenn et al. 2006; Dunning Hotopp et al. 2007; Nikoh et al. 2008; Klasson et al. 2009; Nikoh & Nakabachi 2009; Woolfit et al. 2009).

The members of the genus Wolbachia are rickettsial endosymbitic bacteria belonging to the α-Proteobacteria, whose infections are prevalent among arthropods, including over 60 per cent of insects and some filarial nematodes. They are vertically transmitted through the maternal germline of their host, and are capable of manipulating host reproduction by causing cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), parthenogenesis, male killing or feminization. The ability of Wolbachia to cause these reproductive phenotypes drives their efficient and rapid spread into the host populations (Bourtzis & Miller 2003; Hilgenboecker et al. 2008).

Recently, possibilities for Wolbachia-mediated pest control and management have been proposed. Some medical and hygienic pest insects, such as tsetse flies and mosquitoes, which vector devastating human pathogens, often also carry Wolbachia infections. In theory, if maternally transmitted genetic elements that co-inherit with a CI-inducing Wolbachia, such as the Wolbachia itself or other co-infecting endosymbionts, are transformed with a gene of interest, such as a gene that confers resistance of the insect against the pathogen infection, the genetic trait is expected to be spread and fixed in the insect population, driven by the symbiont-induced reproductive phenotype (Beard et al. 1993; Durvasula et al. 1997; Sinkins et al. 1997; Dobson 2003; Sinkins & Gould 2006; McMeniman et al. 2009). Mass introduction of males infected with CI-inducing Wolbachia has been proposed as a means for suppressing agricultural and medical pest insect populations (Zabalou et al. 2004; Xi et al. 2006). In this context, Wolbachia infections in pest insects are potentially of practical utility.

The Japanese pine sawyer Monochamus alternatus (Insecta : Coleoptera : Cerambycidae) is the longicorn beetle notorious as a vector of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Aphelenchia: Parasitaphelenchidae), which causes pine wilt disease (Zhao et al. 2008). In Japan, the disease has devastated the native pine forests consisting of Pinus thunbergii, Pinus densiflora and Pinus luchuensis (Kishi 1995), annual pine loss having reached a peak of 2 430 000 m3 in 1979 and since then remaining between 600 000 m3 and 1 000 000 m3 (Forest Agency 2008). Monochamus alternatus is also distributed in China, Taiwan and South Korea, vectoring the pine wilt disease there (Kishi 1995; Zhao et al. 2008). The insect is therefore rated among the most important forestry pests in Eastern Asia.

In an attempt to examine the possibility that such control strategies could be applicable to the nematode-vectoring forestry pest, we surveyed Wolbachia infections in Japanese populations of M. alternatus. We detected a number of Wolbachia genes from the longicorn beetle, but, unexpectedly, they turned out to be located on the insect chromosome.

2. Material and methods

(a). Insect materials

Dead trees of P. thunbergii and P. luchuensis infested with larvae of M. alternatus were cut into logs in Kasumigaura City, Ibaraki Prefecture, and in Miyako Island, Okinawa Prefecture, respectively, in the winter of 2004. These two groups of logs were transported to the Forestry and Forest Product Research Institute in Tsukuba City, Ibaraki Prefecture, and separately placed in two outdoor cages from January to September in 2005, where emerging adult beetles were collected.

(b). DNA extraction

Ovaries, testes and midleg muscles were dissected from adult insects, and fat bodies were prepared from larvae. These tissues were individually subjected to DNA extraction. Each of the samples was placed in a 0.6 ml plastic tube with 200 µl of 8 per cent Chelex solution (Chelex 100, Bio-Rad Laboratories) and homogenized using a disposal microtube pestle, to which 10 µl of 10 mg ml−1 proteinase K solution was added. The mixture was incubated at 55°C for 1 h and then 94°C for 10 min. After a brief centrifugation, the supernatant was used as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) template.

(c). PCR detection and sequencing of Wolbachia genes

The following Wolbachia genes were amplified by PCR from the insect DNA samples: a 0.75 kb fragment of the ftsZ gene with the primers ftsF (5′-GTA TGC CGA TTG CAG AGC TTG-3′) and ftsR (5′-GCC ATG AGT ATT CAC TTG GCT-3′) (Kondo et al. 2002a); a 0.6 kb fragment of the wsp gene with the primers 81F (5′-TGG TCC AAT AAG TGA TGA AGA AAC-3′) and 691R (5′-AAA AAT TAA ACG CTA CTC CA-3′) (Zhou et al. 1998); a 0.89 kb fragment of the 16S rRNA gene with the primers 99F (5′-TTG TAG CCT GCT ATG GTA TAA CT-3′) and 994R (5′-GAA TAG GTA TGA TTT TCA TGT-3′) (O'Neill et al. 1992); and a 0.8 kb fragment of the groEL gene with the primers groEfl (5′-TGT ATT AGA TGA TAA CGT GC-3′) and groErl (5′-CCA TTT GCA GAA ATT ATT GCA-3′) (Masui et al. 1997). PCR was performed using the HotStar Taq Mater Mix Kit (Qiagen) under a temperature profile of 95°C for 15 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 52°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min, and a final elongation step of 72°C for 2 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed in agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and observed on an ultraviolet trans-illuminator. Sequencing of the PCR products was conducted with a BigDye Terminator v. 3.1 cycle sequencing kit using the ABI 3100 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

(d). Molecular phylogenetic analysis

Multiple alignments of nucleotide sequences were generated using the program Clustal W (Thompson et al. 1994). For the ftsZ gene, maximum likelihood (ML) and neighbour-joining (NJ) trees were constructed using the programs TreeFinder version of October 2008 (Jobb 2008) and Phylip 3.6 (Felsenstein 2005). A TrN + G substitution model selected by the program Modeltest v. 3.7 (Posada & Crandall 1998) was used for the ML analysis. In addition, amino-acid sites consisting of partial sequences of 11 genes were also subjected to ML and NJ analyses. The JTT + G substitution model selected by the program ProtTest v. 1.4 (Abascal et al. 2005) was used for the ML analysis. Bootstrap values were obtained by generating 1000 bootstrap replications.

(e). Antibiotic treatment

A mixture of 5.9 g of Silk Mate 2M (Norsan Co.), 0.7 g of EBIOS (Asahi food & Healthcare Co.) and 2.8 g of milled inner bark of P. densiflora was kneaded with 8.6 ml of distilled water, and 18.0 g of food clod was prepared in a 50 ml flask. The flask was autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min and, after cooling down, 2 ml of 10 per cent or 5 per cent tetracycline solution was added to the flask. In this way, artificial diets containing 1 per cent or 0.5 per cent (wt/wt) tetracycline were prepared. First instar larvae of M. alternatus were obtained from crosses between ftsZ+ males and ftsZ+ females. A male and a female were placed in a plastic container with branches of P. densiflora as food for the adult insects and a fresh bolt of P. densiflora (3 cm in diameter, 15 cm long) as substrate for oviposition. Each of the insect pairs was transferred to a fresh rearing container every 3 or 4 days. After removal of the adult insects, the oviposited bolt was peeled with a knife and forceps, from which eggs were harvested. The collected eggs were incubated on wet Kimwipe paper in a 9 cm Petri dish at 25°C and monitored daily for egg hatching. First instar larvae, just after hatching, were individually placed on the artificial diet containing either 1 per cent or 0.5 per cent antibiotic in the flask, and reared at 25°C for two, four or six weeks. After rearing, the larvae were dissected with fine forceps, and the fat bodies were individually subjected to DNA extraction and diagnostic PCR of the ftsZ gene as described above.

(f). Inheritance of Wolbachia gene

Reciprocal crosses between ftsZ+ insects and ftsZ− insects of M. alternatus were performed. In each of the plastic containers, a ftsZ+ male and a ftsZ− female were coupled (defined as the G0 generation), and first instar larvae of the offspring (defined as the G1 generation) were harvested as described above. Opposite crosses between a ftsZ− male and a ftsZ+ female were also performed. The larvae were individually placed on the artificial diet without antibiotic (5.9 g of Silk Mate 2M, 0.7 g of EBIOS, 2.8 g of milled inner bark of P. densiflora and 10.6 ml of distilled water) prepared in 50 ml flasks. After rearing for three months at 25°C, the final instar larvae in the flasks were kept at 10°C for diapause termination. Two months later, the larvae were maintained at 25°C to allow growth, pupation and adult emergence. After 3 or 4 days of emergence, a midleg was removed from each of the adult insects, which was subjected to DNA extraction and diagnostic PCR detection of the ftsZ gene as described above. After the diagnosis, each of the ftsZ+ females of the G1 generation was individually mated with each of the ftsZ− males to obtain the next offspring (defined as the G2 generation). The G2 insects were reared in the same way as the G1 generation, and a midleg of the adult insects was subjected to DNA extraction and diagnostic PCR as described above.

(g). Quantitative PCR

Adult insects were individually dissected with fine forceps under a binocular microscope in a Petri dish filled with a phosphate-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (PBT) (1.9 mM NaH2PO4, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 175 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20 (pH 7.4)). Isolated tissues were briefly washed with PBT and immediately subjected to DNA extraction using QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen). The DNA samples were quantified by OD260, diluted appropriately, and subjected to a real-time fluorescence detection quantitative PCR procedure using SYBR Green and the Mx3000P QPCR system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Copy numbers of the ftsZ gene in the samples were quantified using the primers QMonoFtsZ-F (5′-TTA TGA GCG AGA TGG GCA AAG-3′) and QmonoFtsZ-R (5′-TCC GCA GCA CTA ATT GCT GT-3′) under a temperature profile of 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 20 s and 72°C for 20 s. The ftsZ gene titres in the samples were normalized by the DNA content in terms of ftsZ gene copies per nanogram of DNA.

(h). Exhaustive PCR detection of Wolbachia genes

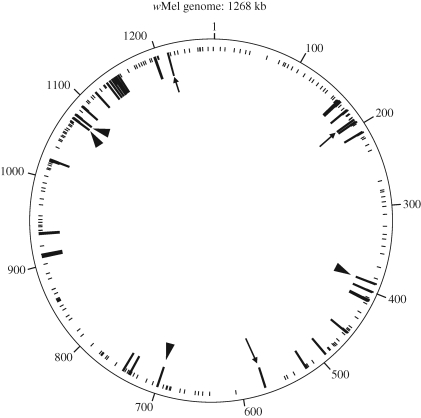

Dissected ovaries from an ftsZ+ adult female were subjected to DNA extraction and used for exhaustive PCR detection of Wolbachia genes. We designed 214 pairs of PCR primers for specific amplification of 214 Wolbachia genes that cover the whole genome of wMel (figure 4, table S1 in the supplementary electronic material), with which PCR reactions were conducted using AmpliTaqGold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, USA). The amplified products were directly sequenced, and the sequences were subjected to BLAST searches to confirm their sequence identity against corresponding Wolbachia genes. Dissected ovaries from an ftsZ− adult female were also subjected to PCR detection of the 214 Wolbachia genes.

Figure 4.

Wolbachia genes detected by PCR from M. alternatus, mapped on the whole genome of the Wolbachia strain wMel from D. melanogaster. Long and short lines indicate PCR-positive and PCR-negative genes, respectively. Arrowheads and arrows indicate the transferred genes that were only detected from the Kasumigaura population and the Miyako population, respectively.

(i). Fluorescent in situ hybridization

Testes were dissected from ftsZ+ males in a phosphate-buffered saline (1.9 mM NaH2PO4, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 175 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), swollen for 30 min in a hypotonic solution (75 mM KCl), and fixed, crushed and suspended in methanol-acetic acid (3∶1) by pipetting. The suspended cells were spread and dried on clean glass slides. A 5.5 kb DNA segment containing Wolbachia genes priN, petA and gyrA was amplified by long PCR with the primers priNF (5′-CGC TTR ATC GGA ATA GTT TGG AA-3′) and gyrA2F (5′-TAT CAC CCA CAT GGT GAT GCA GC-3′) using LA Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa) under a temperature profile of 94°C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min and 68°C for 5 min, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. The DNA was labelled by CyDye 3-dUTP (Amersham Biosciences) by nick translation for use as a probe and hybridization was carried out at 37°C overnight. After hybridization and stringent washes, the chromosomes were stained by DAPI, and the hybridization signals were visualized using a fluorescent microscope (Leica DMRA2) and image analysis software (Leica CW4000).

(j). Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The nucleotide sequences determined in this study have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession numbers AB478999 to AB479029 (see table S1 in the supplementary electronic material).

3. Results

(a). Detection of Wolbachia gene from M. alternatus populations

In total, 22 adults of M. alternatus (9 males and 13 females) from the Kasumigaura population and three adults (two males and one female) from the Miyako population were subjected to diagnostic PCR detection of Wolbachia genes. Of four Wolbachia genes (ftsZ, wsp, groEL and 16S rRNA) examined, only the ftsZ gene was detected from testes and ovaries of all adults of the Kasumigaura population (figure S1 in the supplementary electronic material), whereas no gene was detected from those of the Miyako population (data not shown). The PCR product was also detected from somatic tissues such as brain and muscle of the adult insects from the Kasumigaura population, but not from those from the Miyako population (data not shown).

(b). Phylogenetic placement of Wolbachia gene

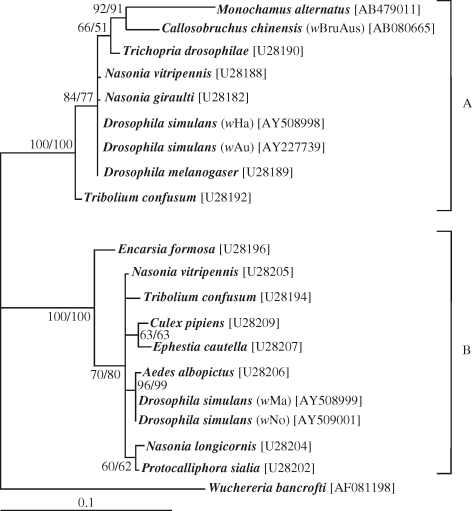

The ftsZ gene sequences were determined for two males and two females from the Kasumigaura population. Direct sequencing of the PCR products yielded unambiguous sequences, indicating that a single type of ftsZ sequence dominated in the insects. The sequences from different samples were identical to each other. DNA database searches using the sequence as a query retrieved Wolbachia ftsZ gene sequences as the highest hits (data not shown). Molecular phylogenetic analysis placed the ftsZ gene of M. alternatus in the Wolbachia supergroup A. The sequence was the most closely related to the ftsZ gene sequence of wBruAus from the adzuki bean beetle Callosobruchus chinensis, which was shown as a Wolbachia genome fragment laterally transferred to the X chromosome of the insect (Kondo et al. 2002b) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the ftsZ gene sequence identified from M. alternatus, together with representatives of the Wolbachia supergroups A and B. A supergroup D sequence (Wuchereria bancrofti) was used as an outgroup. A total of 523 aligned nucleotide sites were subjected to the analysis. A maximum likelihood (ML) tree is shown, and a neighbour-joining (NJ) tree exhibited the same topology. Bootstrap probabilities (ML/NJ) no less than 50 per cent are shown at the nodes. Accession numbers are in brackets.

(c). Persistence of Wolbachia gene against antibiotic treatment

In an attempt to establish a cured line of M. alternatus, a total of 60 first instar larvae derived from ftsZ+ adult females were reared on artificial diets containing either 0.5 per cent or 1 per cent tetracycline. The larvae developed well on the artificial diets. Despite the continuous exposure to the antibiotic, the Wolbachia gene persisted in the larvae throughout the experimental period for six weeks (table 1).

Table 1.

Proportion of M. alternatus larvae whose Wolbachia were removed by antibiotic treatment.

| tetracycline concentration |

||

|---|---|---|

| 0.5% |

1.0% |

|

| rearing period (week) | proportion of ftsZ-negative individuals (%) (mean weight of larvae ± s.d. in mg) [n]a | |

| 2 | 0 (445 ± 92)[9] | 0 (218 ± 132) [7] |

| 4 | 0 (916 ± 340) [9] | 0 (818 ± 333) [8] |

| 6 | 0 (1168 ± 89) [7] | 0 (1087 ± 268) [8] |

aEach treatment was administered to 10 larvae of the first instar and only living larvae at the end of rearing period were used in this analysis.

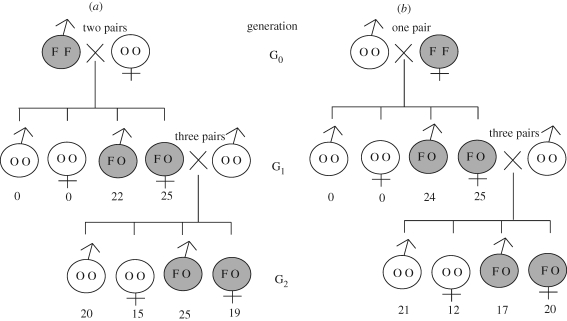

(d). Biparental and Mendelian inheritance of Wolbachia gene

To examine the inheritance mode of the Wolbachia gene in M. alternatus, two pairs of ftsZ+ males and ftsZ− females, and a single pair of ftsZ− males and ftsZ+ females, were coupled. In the G1 generation of the reciprocal crosses, all the offspring were ftsZ-positive. When the ftsZ-positive G1 females were mated with ftsZ-negative males, both G2 males and G2 females derived from the reciprocal crosses consistently segregated into ftsZ-positives and ftsZ-negatives (figure 2). Hence, the Wolbachia gene was passed to the next host generation biparentally, although Wolbachia and other endosymbionts are generally subject to maternal inheritance. It should be noted that these patterns are in agreement with the typical Mendelian inheritance, as if the Wolbachia gene is associated with an autosome of the host insect.

Figure 2.

Inheritance patterns of the Wolbachia ftsZ gene in M. alternatus. (a) Cross between ftsZ+ male and ftsZ− female. (b) Cross between ftsZ− male and ftsZ+ female. Shade indicates the presence of the ftsZ gene. Letters in each circle of male or female symbol mean homozygous ftsZ (FF), homozygous no ftsZ (OO) or heterozygous ftsZ (FO). Numbers beneath each male or female symbol show the number of offspring obtained.

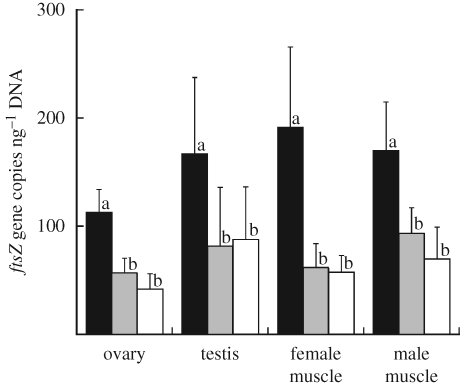

(e). Quantification of Wolbachia gene titres

If the Wolbachia gene is actually located on an autosome of the insect, it is expected that the gene titre in homozygotic positive insects should be twice as much as the gene titre in heterozygotic positive insects (see figure 2). Quantitative PCR assays of the ftsZ gene confirmed the expectation: irrespective of tissues and sexes of the insects, the offspring of ftsZ+–ftsZ+ crosses contained gene titres nearly twice as great as the offspring of ftsZ+–ftsZ− crosses (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Titres of the ftsZ gene in M. alternatus evaluated by quantitative PCR in terms of ftsZ gene copies per nanogram of total DNA in each sample. Solid columns show the adult individuals produced by the cross between a ftsZ+ male and a ftsZ+ female, shaded columns show those produced by the cross between a ftsZ− male and a ftsZ+ female, and open columns show those produced by the cross between a ftsZ+ male and a ftsZ− female. The means and standard deviations of 10 measurements are shown for the ovary, testis, female thoracic muscle and male thoracic muscle. Different letters (a and b) indicate statistically significant differences (Mann–Whitney U-test: p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction).

(f). How many Wolbachia genes are located on the insect genome?

Of 214 Wolbachia genes that were subjected to PCR detection with a series of specific primer sets (see table S1 in the supplementary electronic material), 31 genes gave amplified products of expected sizes in an ftsZ+ insect from the Kasumigaura population (figure 4). DNA sequencing confirmed that all these PCR products certainly represent Wolbachia genes. Of the 31 genes sequenced, 24 genes contained premature stop codon(s) and/or frame shift(s) (table S1 in the supplementary electronic material), indicating that most of the Wolbachia genes in M. alternatus have been inactivated by structural disruptions. From an ftsZ− insect from the Miyako population, 30 of the 214 genes were detected. Of the PCR-positive genes, 27 genes were commonly detected from both the populations, while four genes (aspS, ftsZ, wd1129 and topA) and three genes (araD, cog0863 and ftsI) were identified only from the Kasumigaura population and the Miyako populations, respectively (figure 4, table S1 in the supplementary electronic material).

(g). Phylogenetic affinity to laterally transferred Wolbachia genes in C. chinensis

Of the 31 Wolbachia genes detected from M. alternatus, 11 genes (fabF, gltP, mpp2, ftsH, gyrA, qor, ftsZ, hslU, thy1, priN and petA) were also found in laterally transferred Wolbachia genes from the adzuki bean beetle C. chinensis (Nikoh et al. 2008). Molecular phylogenetic analyses revealed that, as with the ftsZ gene alone (figure 1), the Wolbachia genes from M. alternatus consistently exhibited phylogenetic affinity to the laterally transferred Wolbachia genes in C. chinensis (figure S2 in the supplementary electronic material).

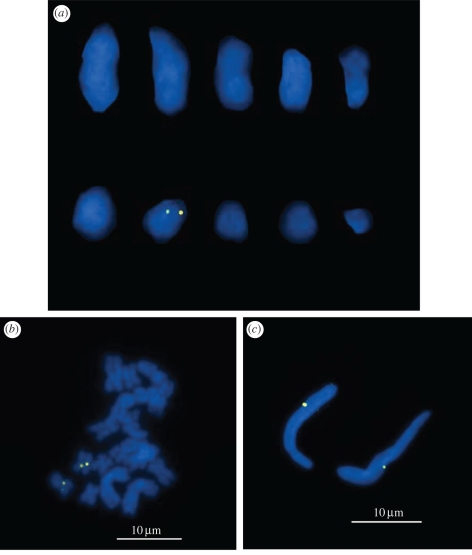

(h). In situ hybridization of Wolbachia genes on insect chromosomes

Fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis, using a 5.5 kb region containing Wolbachia genes priN, petA and gyrA as a probe, was performed on the chromosome preparations of the ftsZ+ insects. The karyotype of M. alternatus was 2n = 20. Among the 10 chromosomes, a pair of hybridization signals was reproducibly detected on the seventh longest chromosome (figure 5a). The chromosome was metacentric, on which a region proximal to the centromere exhibited the hybridization signals (figure 5b). The dual signals owing to sister chromatids reflected the homozygosity of the ftsZ+ insects for the Wolbachia genes (see figures 2 and 3). Meanwhile, each sperm nucleus, containing a haploid set of the insect genome, exhibited a single hybridization signal (figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization of Wolbachia genes on the chromosomes of M. alternatus. (a) Male chromosomes in metaphase II arranged in the order of size. (b) Male chromosomes in the meiotic metaphase I. (c) Sperm nuclei. Wolbachia genes are visualized in yellow, and insect chromosomes are in blue.

4. Discussion

On the basis of these results, we conclude that many laterally transferred Wolbachia genes are present on an autosome of the longicorn beetle M. alternatus. An exhaustive PCR survey detected around 14 per cent (31/214) of the Wolbachia genes examined in the ftsZ+ insects (table S1 in the supplementary electronic material). Here it should be noted that the value of 14 per cent might be an underestimate, on account of possible PCR primer mismatches leading to detection failure. Considering that the wMel genome is 1268 kb in size and encodes 1195 open reading frames (Wu et al. 2004), we expect that, although it is a very rough estimate, a Wolbachia genomic region, which may exceed 180 kb in size and encode more than 170 genes, is located on the insect chromosome.

The ftsZ+ insects and the ftsZ− insects of M. alternatus examined in this study were derived from two distant localities in Japan: Kasumigaura, Ibaraki, is located on mainland Japan, whereas Miyako, Okinawa, is a southwestern island of the Ryukyu Archipelago approximately 2000 km away from Kasumigaura. The laterally transferred Wolbachia genes were definitely detected from both insect populations, but the gene repertoire differed between the populations (table S1 in the supplementary electronic material). To understand the prevalence and variation of the laterally transferred Wolbachia genes in M. alternatus, a broader survey of natural insect populations covering Japan and other Asian countries is needed. In addition to the laterally transferred Wolbachia genes, if CI-inducing Wolbachia infections should be discovered in some populations of M. alternatus, such endosymbionts are potentially of practical use in controlling the notorious forestry pest.

The origin of the laterally transferred Wolbachia genes in M. alternatus is of evolutionary interest. Considering that many Wolbachia genes are present (table S1 in the supplementary electronic material), the genes are phylogenetically coherent (figure 1 and figure S2 in the supplementary electronic material), and the genes are located on a specific region of the chromosome (figure 5), it appears plausible that a large Wolbachia genome fragment was integrated into the chromosome in an ancestor of M. alternatus as a single evolutionary event.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the ftsZ gene indicated that the laterally transferred Wolbachia gene of M. alternatus is, interestingly, the most closely related to the laterally transferred Wolbachia gene previously identified from the adzuki bean beetle C. chinensis (figure 1). Analyses on the basis of 11 genes also supported the phylogenetic affinity between the laterally transferred Wolbachia genes of M. alternatus and those of C. chinensis (figure S2 in the supplementary electronic material). The beetle families Cerambycidae and Bruchidae do not form sister groups (Hunt et al. 2007), which argues against the possibility that the transferred Wolbachia genes were acquired in the common ancestor of M. alternatus and C. chinensis. It seems likely that closely related strains of Wolbachia endosymbionts have jumped into the nuclear genomes of the longicorn beetle and the bean beetle independently. A plausible explanation for the phylogenetic relatedness of the transferred endosymbionts is just a chance coincidence. An alternative explanation is that, although speculative, particular genetic strains of Wolbachia may exhibit higher frequencies of integration into the host insect genomes, although the mechanisms involved in the process are obscure. In this context, it is of great interest to discover extant Wolbachia endosymbionts phylogenetically allied to the transferred genes and to investigate their biological aspects. Worldwide surveys of M. alternatus and C. chinensis might lead to the discovery of such relict bacterial Wolbachia endosymbionts, which would shed light on the evolutionary origin and process of host–symbiont gene transfers.

Thus far, lateral gene transfers from Wolbachia endosymbionts have been reported from a variety of insects and nematodes. In the adzuki bean beetle C. chinensis (Coleoptera : Bruchidae), a large genome fragment of Wolbachia, estimated as about 380 kb in size, was identified on the X chromosome (Kondo et al. 2002b; Nikoh et al. 2008). In the fruitfly Drosophila ananassae (Diptera : Drosophilidae), a nearly complete Wolbachia genomic region was found on the second chromosome (Dunning Hotopp et al. 2007). A small number of Wolbachia genes were detected in the genomes of parasitoid wasps of the genus Nasonia (Hymenoptera : Pteromalidae) and filarial nematodes of the genera Onchocerca, Brugia and Dirofilaria (Spirurida : Onchocercidae) (Fenn et al. 2006; Dunning Hotopp et al. 2007). In the mosquito Aedes aegypti, a Wolbachia-allied gene was shown to be expressed in salivary glands (Klasson et al. 2009; Woolfit et al. 2009). In the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum (Hemiptera : Aphididae), a Wolbachia-like gene was found to be expressed in the symbiotic organ called the bacteriome (Nikoh & Nakabachi 2009). These cases seem to represent different evolutionary phases and stages of the laterally transferred endosymbiont genes. Initially a Wolbachia genome region, which may be as large as the whole genome or as small as a few genes, was transferred to the host chromosome. Most of the transferred genes have degenerated and been lost by mutations, recombinations and/or deletions. Occasionally, some of the transferred genes may survive, acquiring novel expression patterns and playing biological roles, thereby assimilating into the gene repertoire of the host organism. In addition to the cases of C. chinensis and D. ananassae, the massive gene transfer from Wolbachia to M. alternatus will provide insights into the evolution and fate of laterally transferred endosymbiont genes in multicellular host organisms.

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Nakamura, M. Akiba and H. Kosaka for assisting in the collection of dead pine trees, N. Kanzaki for advising on phylogenetic analysis, and K. Nikoh for technical assistance. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Science (B) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (no. 19780126) to T.A.

References

- Abascal F., Zardoya R., Posada D.2005ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics 21, 2104–2105 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J. O.2005Lateral gene transfer in eukaryotes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62, 1182–1197 (doi:10.1007/s00018-005-4539-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard C. B., O'Neill S. L., Tesh R. B., Richards F. F., Aksoy S.1993Modification of arthropod vector competence via symbiotic bacteria. Parasitol. Today 9, 179–183 (doi:10.1016/0169-4758(93)90142-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis K., Miller T. A.2003Insect symbiosis Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- Dobson S. L.2003Reversing Wolbachia-based population replacement. Trends Parasitol 19, 128–133 (doi:10.1016/S1471-4922(03)00002-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning Hotopp J. C., et al. 2007Widespread lateral gene transfer from intracellular bacteria to multicellular eukaryotes. Science 317, 1753–1756 (doi:10.1126/science.1142490) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durvasula R., Gumbs A., Panackal A., Kruglov O., Aksoy S., Merrifield R. B., Richards F. F., Beard C. B.1997Prevention of insect-borne disease: an approach using transgenic symbiotic bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 3274–3278 (doi:10.1073/pnas.94.7.3274) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J.2005Phylip(Phylogeny Inference Package) version 3.6. Distributed by the author.Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA [Google Scholar]

- Fenn K., Conlon C., Jones M., Quail M. A., Holroyd N. E., Parkhill J., Blaxter M.2006Phylogenetic relationships of the Wolbachia of nematodes and arthropods. PLoS Pathog 2, e94 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0020094) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forest Agency. 2008Damage of pine wilt disease in 2007. Forest Pests 57, 203–204 [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenboecker K., Hammerstein P., Schlattmann P., Telschow A., Werren J. H.2008How many species are infected with Wolbachia?: a statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 281, 215–220 (doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01110.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt T., Bergsten J., et al. 2007A comprehensive phylogeny of beetles reveals the evolutionary origins of a superradiation. Science 318, 1913–1916 (doi:10.1126/science.1146954) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobb G.2008Treefinder, version of October 2008. Distributed by the author at www.treefinder.de.

- Keeling P. J., Palmer J. D.2008Horizontal gene transfer in eukaryotic evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 605–618 (doi:10.1038/nrg2386) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi Y.1995The pine wood nematode and the Japanese pine sawyer Tokyo, Japan: Thomas [Google Scholar]

- Klasson L., Kambris Z., Cook P. E., Walker T., Sinkins S. P.2009Horizontal gene transfer between Wolbachia and the mosquito Aedes aegypti. BMC Genom. 10, 33 (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-33) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo N., Ijichi N., Shimada M., Fukatsu T.2002aPrevailing triple infection with Wolbachia in Callosobruchus chinensis (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). Mol. Ecol. 11, 167–180 (doi:10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01432.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo N., Nikoh N., Ijichi N., Shimada M., Fukatsu T.2002bGenome fragment of Wolbachia endosymbiont transferred to X chromosome of host insect. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14 280–14 285(doi:10.1073/pnas.222228199) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin E. V., Makarova K. S., Aravind L.2001Horizontal gene transfer in prokaryotes: quantification and classification. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55, 709–742 (doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.709) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui S., Sasaki T., Ishikawa H.1997groE-homologous operon of Wolbachia, an intracellular symbiont of arthropods: a new approach for their phylogeny. Zool. Sci. 14, 701–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMeniman C. J., Lane R. V., Cass B. N., Fong A. W. C., Sidhu M., Wang Y. F., O'Neill S. L.2009Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science 323, 141–144 (doi:10.1126/science.1165326) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoh N., Nakabachi A.2009Aphids acquired symbiotic genes via lateral gene transfer. BMC Biol. 7, 12 (doi:10.1186/1741-7007-7-12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoh N., Tanaka K., Shibata F., Kondo N., Hizume M., Shimada M., Fukatsu T.2008Wolbachia genome integrated in an insect chromosome: evolution and fate of laterally transferred endosymbiont genes. Genome Res. 18, 272–280 (doi:10.1101/gr.7144908) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochman H., Lawrence J. G., Groisman E. A.2000Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature 405, 299–304 (doi:10.1038/35012500) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill S. L., Giordano R., Colbert A. M. E., Karr T. L., Robertson H. M.199216S rRNA phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial endosymbionts associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 2699–2702 (doi:10.1073/pnas.89.7.2699) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall K. A.1998Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14, 817–818 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkins S. P., Gould F.2006Gene drive systems for insect disease vectors. Nat. Rev. Genet 7, 427–435 (doi:10.1038/nrg1870) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkins S. P., Curtis C. F., O'Neill S. L.1997The potential application of inherited symbiont systems to pest control. In Influential passengers: inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction (eds O'Neill S. L., Hoffman A. A., Werren J. H.), pp. 155–208 New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J.1994Clustal W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 (doi:10.1093/nar/22.22.4673) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolfit M., Iturbe-Ormaetxe I., McGraw E. A., O'Neill S. L.2009An ancient horizontal gene transfer between mosquito and the endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia pipientis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 367–374 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msn253) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M., Sun L. V., Vamathevan J., et al. 2004Phylogenomics of the reproductive parasite Wolbachia pipientis wMel: a streamlined genome overrun by mobile genetic elements. PLoS Biol. 2, e69 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020069) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z., Khoo C. C. H., Dobson S. L.2006Interspecific transfer of Wolbachia into the mosquito disease vector Aedes albopictus. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 1317–1322 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3405) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabalou S., Riegler M., Theodorakopoulou M., Stauffer C., Savakis C., Bourtzis K.2004Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility as a means for insect pest population control. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15042–15045 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0403853101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B. G., Futai K., Sutherland J. R., Takeuchi Y.2008Pine wilt disease Tokyo, Japan: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Rousset F., O'Neill S.1998Phylogeny and PCR-based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265, 509–515 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0324) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]