Abstract

Low-frequency ultrasounds (US) are used to enhance drug transdermal transport. Although this phenomenon has been extensively analyzed, information on US effects on the single skin cell components is limited. Here, we investigated the possible effects of low-frequency US on viability and immune functions of cultured human keratinocytes and dendritic cells (DC), skin cells involved in the regulation of many immune-mediated dermatoses. We demonstrated that US, employed at low-frequency (42 KHz) and low-intensity (0.15 W/cm2) values known to enhance drug and water transdermal transport, did not affect extracellular-signal-regulated-kinase (ERK)1/2 activation, cell viability, or expression of adhesion molecules in cultured keratinocytes. Moreover, US at these work frequency and intensity did not influence the keratinocyte expression and release of immunomodulatory molecules. Similarly, cultured DC treated with low-frequency low-intensity US were viable, and did not show an altered membrane phenotype, cytokine profile, nor antigen presentation ability. However, intensity enhancement of low-frequency US to 5 W/cm2 determined an increase of the apoptotic rate of both keratinocytes and DC as well as keratinocyte CXCL8 release and ERK1/2 activation, and DC CD40 expression. Our study sustains the employment of low-frequency and low-intensity US for treatment of those immune skin disorders, where keratinocytes and DC have a pathogenetic role.

1. Introduction

Skin is a very efficient barrier against external agent penetration. Low permeability is attributed to the stratum corneum, the outermost skin layer, characterized by a robust structure containing dense dead cells, corneocytes, which are embedded in a continuous matrix of lipid bilayers. The tightly packed stacks of lipid lamellae in the extracellular space make the stratum corneum a highly impermeable membrane [1]. Low permeability of the skin is also a limit for the transdermal drug delivery, which could represent a valid alternative to oral delivery and injection. A diverse spectrum of mechanical [2, 3], electrical [4], and chemical [5] techniques have been previously explored to enhance skin permeability and, consequently, to increase the transdermal drug transport. Exposure to ultrasound (US) has also been shown to greatly enhance the permeability of skin for permitting transdermal drug delivery, a phenomenon termed sonophoresis [6–8]. Based on the frequency used, three types of US can be applied to increase skin permeability: therapeutic US (from 1 to 3 MHz), high-frequency US (above 3 MHz), and low-frequency US (20–100 KHz). However, low-frequency US have been found to be more efficient than high-frequency US in inducing the transdermal transport [7, 8]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the generation of gas bubbles in the skin (cavitation) is the main mechanism responsible for sonophoresis and is better induced by low-frequency US, being inversely related to US frequency [9, 10]. The efficacy of low-frequency US in inducing skin permeation is proportional to their intensity. US intensities starting from 0.1 W/cm2 are sufficient to permit the transdermal transport across human skin of many permeants, including estradiol, salicylic acid, corticosterone, and water [7, 11–13].

Other than representing the major barrier between the body and the external environment, the skin provides a complex microenvironment for the initiation and shaping of T cell-mediated immune responses against microorganisms. Among skin cell components, keratinocytes and dendritic cells (DC), including epidermal Langerhans cells and dermal DC, are importantly involved in the induction and amplification of immune responses during inflammatory skin reactions [14–16]. In particular, DC are specialized to recognize and capture foreign antigens as well as to activate naïve T cells, and resident keratinocytes contribute to attract and retain discrete T-cell subsets into the skin. In order to test whether US application could influence the pathophysiological functions of skin cell components, we investigated on the effects of low-frequency US (42 KHz) administered at intensity ranging from 0.15 to 7 W/cm2, on cultured keratinocyte and DC populations. In particular, we examined the extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 activation, viability, and membrane molecule expression in US-treated keratinocytes, and, in parallel, their ability to produce inflammatory molecules, such as immune-modulatory membrane molecules, cytokines, and chemokines. Moreover, we explored the possible US effects on DC apoptosis, immune phenotype and functions, including activation of naïve T lymphocytes.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. US Generation and Application

The device generating low-frequency US has been realized by Teuco Guzzini technical laboratory (Montelupone, Macerata, Italy). US were produced continuously with a frequency of 42 KHz by means of piezoelectric ceramic vibrating at its own odd frequency and driven by a power supply. Piezoelectric ceramics were placed under an acrylic basement, used as a support for the cell culture plates, with an US transmission gel (Transound, EF Medica, Bolzano, Italy) film being interposed to ensure US distribution. The distance between the transducer ceramics and cell plate bottom was ~0.3 cm. US emission was measured using a calibrated hydrophone placed inside the culture medium. Treatments with US were conducted for 7–21 minutes (1–3 cycles) at intensity ranging from 0.15 to 7.0 W/cm2.

2.2. Keratinocyte Cultures and Treatments

Normal human keratinocytes were obtained from skin biopsies of healthy volunteers (n = 3), as previously reported [17]. Briefly, biopsies were disaggregated to single-cell suspensions by using six sequential treatments with 0.05% trypsin/0.02% EDTA (InVitrogen Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA, USA), each conducted for 30 minutes at 37°C. Keratinocytes were then counted and seeded in F75 flasks on a fibroblast 3T3 feeder layer previously treated with mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy). Second or third passage keratinocytes were used in all experiments, with cells cultured in 3 cm-diameter plates in serum-free medium (Keratinocyte Growth Medium, Clonetics, Walkersville, MD, USA), for at least 3–5 days before performing experiments. Keratinocytes were treated with US at a frequency of 42 KHz for 1 cycle of 7 minutes or 3 cycles (in total 21 minutes). Some keratinocyte cultures were in parallel stimulated with 200 U/mL IFN-γ plus 50 ng/mL TNF-α (R&D Systems, Abingdon, Oxon, United Kingdom) for 24 hours.

2.3. DC Preparations

DC were generated by culturing monocytes, previously obtained from the adherent fraction of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) depleted of CD2+, CD19+, and CD56+ cells by monoclonal antibody (Ab)-coated immunomagnetic beads, in complete RPMI 1640 medium (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich) in the presence of 200 ng/mL GM-CSF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and 200 U/mL IL-4 (R&D Systems) at 37°C. Medium was replaced after 3 days and cells were used at day 7 of culture. This procedure gave > 97% pure CD1a+, CD14− DC preparations. To induce maturation, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added at 50 μg/mL for the last 24 hours of DC culture.

2.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis

Keratinocyte expression of membrane ICAM-1, HLA-DR, and integrins was evaluated using fluorescein isothiocyanate- (FITC-) conjugated anti-CD54 (clone 84H10; Immunotech, Marseille, France), anti-HLA-DR (clone L243, BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), anti-human α6β4 integrin (clone JB1a, Chemicon, Temecula, CA), and anti-human β1 integrin (clone S341) monoclonal Abs. Apoptosis and necrosis of keratinocytes and DC were evaluated using the Genzyme TACS Annexin V apoptosis detection kit (R&D Systems). Activation of caspase 9 in keratinocytes was revealed using the carboxyfluorescein FLICA assay kit (B-Bridge International, Sunnyvale, CA). Mature DC previously treated or not with US were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD80 (MAB104, IgG1, Immunotech), -CD83 (HB15e, IgG1, BD PharMingen) -CD86 (2331, IgG1, BD PharMingen), -CD40 (5C3, IgG1, BD PharMingen), -HLA-DR (clone L243, BD PharMingen), -CD1a (HI149, IgG1, BD PharMingen) Abs. In control samples, staining was performed using isotype-matched control Abs. Cells were analyzed with a FACScan equipped with Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Cell-free supernatants from resting or stimulated keratinocyte cultures were tested for CXCL10 content using the Ab pair, the purified monoclonal Ab 4D5/A7/C5 for coating and the biotinylated 6D4/D6/G2 (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). CCL2 and CXCL8 were measured with OptEIA kits (BD PharMingen), as per the manufacturer's protocol. TNF-α and IL-6 were assayed with DuoSet ELISA kits (R&D Systems). DC supernatants collected from cultures 24 hours after the US and LPS treatments were assayed for IL-12 p70 subunit, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 contents using the DuoSet ELISA kits (R&D Systems). The plates were analyzed in an ELISA reader (model 3550 UV, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Keratinocyte and DC cultures were performed in triplicate for each condition. Results are given as mean ng or pg/106 cells ± SD.

2.6. Mixed Lymphocytes Reaction (MLR) Proliferation Assay

In order to obtain responder population for the primary MLR assay, T naïve lymphocytes were purified from allogeneic PBMC nonadherent fraction by using CD45RA immunomagnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany), according to the manufacturer' instructions. At day 5 of culture, immature DC were left untreated or were treated with US at a frequency of 42 KHz for 1–3 cycles before adding LPS for the next 24 hours. Untreated or US-treated mature DC were then washed and cocultured in 96-well flat bottomed microplates in serial dilutions (0.625 to 10 × 103/well) together with purified allogeneic T naïve lymphocytes (2 × 105/well) in complete RPMI medium. Cocultures were pulsed at day 5 with 2 μCi/mL [3H]-thymidine (Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK) for about 16 hours and then harvested onto fiber-coated 96-well plates. Radioactivity (counts per minute, CPM) was measured in a β-counter (Topcount; Packard, Groningen, The Netherlands) and results were given as the mean counts per minute ± SD of triplicate cultures.

2.7. Western Blotting and Densitometry

Protein extracts were prepared by solubilizing cells in RIPA buffer (1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium dehoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, SDS) containing a mixture of protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The latter were blocked, and probed with anti-ERK1/2 (C16; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (E4; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or with anti-β-actin (C11; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) Abs diluted in PBS containing 5% nonfat dried milk. Filters were developed using the ECL-plus detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK), and, then, subjected to densitometry using an Imaging Densitometer model GS-710 (Bio-Rad) supported by the Molecular Analyst software, and band intensities were evaluated in three independent experiments. The densitometry values of phopsho-ERK1/2 were divided by the values of total ERK1/2 and, then, to β-actin bands, and expressed as -fold induction (F. I.) ± SD in experimental relative to untreated samples, to which were given a value of 1.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The Wilcoxon's signed rank test was used (SigmaStat, Jandel Co., San Rafael, CA) to compare the apoptosis rate as well as the expression levels of membrane molecules, phospho-ERK1/2, chemokines, and cytokines between unstimulated and US-treated cells. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. ERK1/2 Activation, Viability, and Membrane Molecule Expression Is Not Altered in Human Keratinocytes Treated with US at a Frequency of 42 KHz and Intensity of 0.15 W/cm2

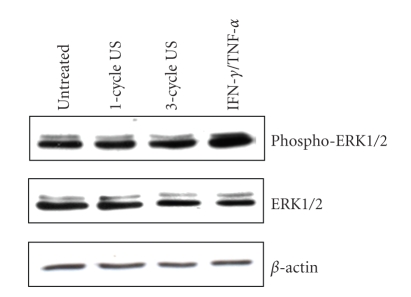

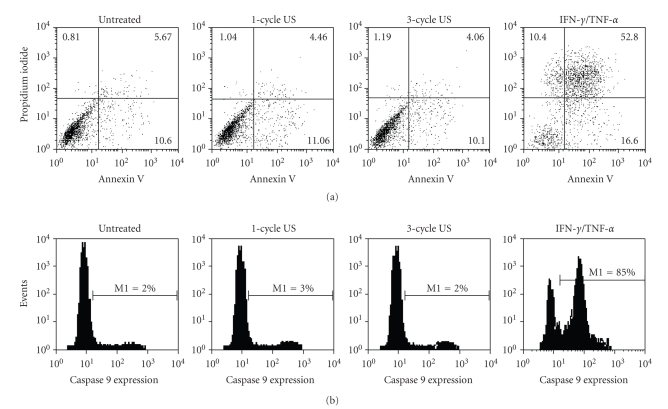

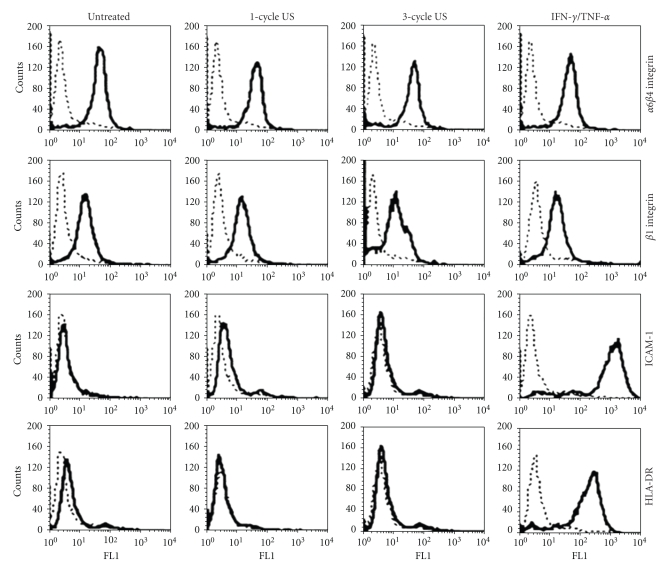

Although several studies have examined the effects of US application on whole skin [9, 11], evidence of US-induced responses on the single cell components of the skin is still limited. To this end, the effects of low-frequency US were analyzed on keratinocyte cultures established from skin biopsies of healthy donors. US were employed on cell cultures at frequency (42 KHz) and intensity (0.15 W/cm2) values known to be effective in enhancing human skin permeation in vivo [12]. We firstly investigated on the US effects on keratinocyte expression and activation of ERK1/2 proteins, which sustain proliferative and self-protective programs in keratinocytes [18]. As shown in Figure 1, the phosphorylation status of ERK1/2 did not vary between untreated and US-treated keratinocytes, although it was upregulated upon IFN-γ and TNF-α treatment, as previously described [18]. Consistently, the levels of ERK1/2 total proteins were unaffected by US irradiation. We, then, analyzed keratinocyte viability by evaluating annexin V exposure on plasmamembrane and propidium iodide (PI) incorporation into DNA or caspase 9 expression. As positive control of apoptosis, keratinocyte cultures were in parallel stimulated with IFN-γ plus TNF-α. As shown in Figure 2(a), upon 1-cycle or 3-cycle US stimulation the number of apoptotic cells (lower and upper right quadrants) or necrotic cells (upper left quadrant) was comparable to that observed in untreated cultures. In contrast, an high number of apoptotic and necrotic cells were induced by the IFN-γ plus TNF-α treatment. The keratinocyte apoptotic rate was also assessed by measuring the level of active caspase 9, a proteolytic enzyme involved in the early phase of apoptotic processes, whose expression was revealed using the fluorescein-labeled inhibitor FAM-LEHD-FMK. Stained apoptotic cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and, as shown in Figure 2(b), only IFN-γ plus TNF-α treatments were able to induce an high percentage (85%) of caspase 9-positive cells. In contrast, both 1-cycle and 3-cycle US did not modify viability of cells (Figure 2(b)). Moreover, treatment of keratinocytes with 1 or 3 cycles of US at 42 KHz did not alter the surface expression of the β1 and α6β4 integrins, essential components of hemidesmosomes involved in the cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix adhesion of keratinocytes in the epidermis [19] (Figure 3). Similarly, ICAM-1 and HLA-DR, two membrane molecules involved in the retention and activation of T lymphocytes during skin inflammatory responses were also unaffected by US treatment, whereas they were highly upregulated by IFN-γ and TNF-α, as previously reported [14].

Figure 1.

US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 do not influence ERK1/2 levels in keratinocytes. Keratinocyte cultures treated with 1–3 cycles of US or left untreated or activated with IFN-γ and TNF-α were analyzed by Western blotting analysis performed with an Ab specific for both p42 and p44 ERK phosphorylated at Tyr 204 residue (phospho-ERK1/2). Filters were stripped and reprobed with an anti-ERK1/2 Ab. Equal loading of the samples was assayed probing the filters using an Ab against the β-actin protein.

Figure 2.

US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 do not alter keratinocyte viability. (a) Keratinocyte cultures treated with 1–3 cycles of US or left untreated were stained with annexin V and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. As expected, IFN-γ plus TNF-α treatment induced a high percentage of necrotic (10.4%) and apoptotic (52.8%) cells. The x-axis and y-axis indicate the fluorescence intensities of annexin V binding and PI incorporation, respectively. (b) The keratinocyte apoptotic rate was also assessed by measuring caspase 9 expression, whose levels were measured using the fluorescein-labeled inhibitor FAM-LEHD-FMK and cytofluorimetric analysis. Treatment of cultures with IFN-γ plus TNF-α was able to induce a high percentage (85%) of caspase 9-positive cells (M1). The x-axis and y-axis indicate the relative cell number and fluorescence intensity, respectively. Representative experiment of five performed is shown.

Figure 3.

US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 do not alter membrane molecule expression in human keratinocytes. Keratinocytes were analyzed for β1 and α6β4 integrins, ICAM-1 and HLA-DR expression by flow cytometry after 1–3 cycles of US or treatment with IFN-γ plus TNF-α. Dotted lines represent staining with matched isotype immunoglobulins. The x-axis and the y-axis indicate the relative cell number and fluorescence intensity, respectively.

3.2. Chemokine and Cytokine Release by Human Keratinocytes Is Not Modified by US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2

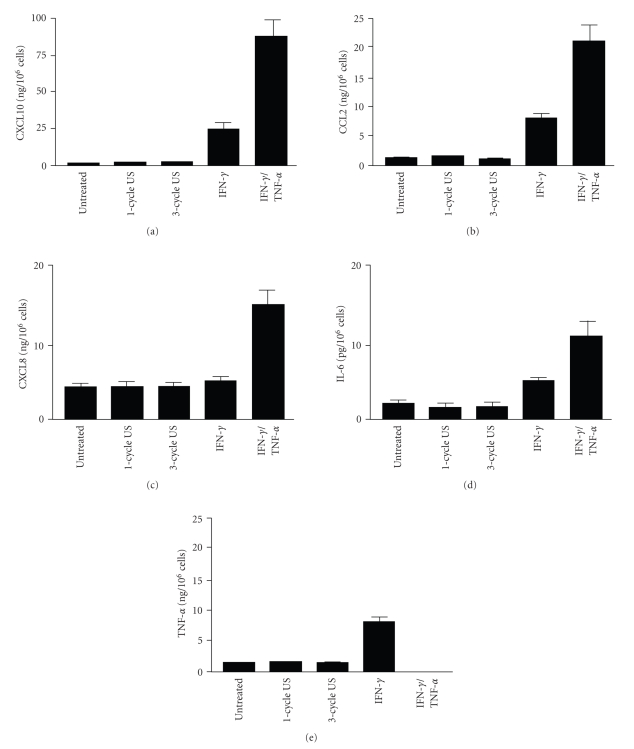

Keratinocytes can be activated by a variety of stimuli to produce chemokines and cytokines important for the recruitment and activation of immune cells and for the formation of a T cell-rich infiltrate during skin diseases [14, 15]. In the next series of experiments we tested whether US stimulation could influence the release of chemokines, such as CXCL10, CCL2, and CXCL8, abundantly expressed by keratinocytes activated by IFN-γ and mostly by IFN-γ plus TNF-α. US-treated keratinocytes cultures were also analyzed for the release of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α. Figure 4 shows that both 1-cycle and 3-cycle US at a frequency of 42 KHz did not influence the release of the proinflammatory chemokines CXCL10, CCL2 CXCL8 (Figures 4(a)–4(c)) and the cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α (Figures 4(d) and 4(e)), all abundantly upregulated by keratinocytes when activated with IFN-γ or IFN-γ plus TNF-α.

Figure 4.

Chemokine and cytokine release by keratinocytes treated with US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2. CXCL10 (a), CCL2 (b), CXCL8 (c), IL-6 (d), and TNF-α (e). Concentrations were estimated by ELISA in supernatants of keratinocyte cultures treated with US or left untreated. Soluble factor contents were also measured in supernatants of cells treated with IFN-γ alone or with IFN-γ plus TNF-α. Data are expressed as mean nanograms or picograms per 106 cells ± SD of triplicate cultures.

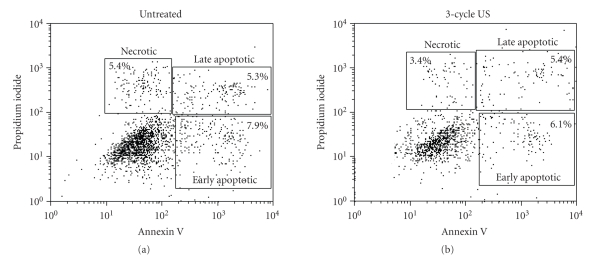

3.3. Treatment with US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 Does Not Induce Apoptosis and Necrosis of DC

The effects of the low-frequency US were also examined on DC, the skin cell component representing the main mediator of inflammatory responses during skin diseases [20]. DC can be generated in vitro from peripheral blood or bone marrow progenitors. In particular, circulating CD14+ monocytes, cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4, can acquire many phenotypical features of primary DC, such as an increased expression of immune membrane molecules, and become able to evoke potent T cell responses [16]. To investigate whether US application could influence the viability of DC population, we analyzed monocyte-derived DC irradiated with US at 42 KHz frequency and 0.15 W/cm2 intensity by performing the trypan blue exclusion test or using the annexin V apoptosis detection system. Trypan blue assay demonstrated that both 1 cycle and 3 cycles of US stimulation did not significantly vary the number of viable cultured DC (viability superior to 93%; data not shown). Similar results were obtained by performing annexin V and PI stainings. As shown in Figure 5, after 3-cycle US stimulation, the number of annexin V+ or annexin/PI+ apoptotic cells was similar to that observed for untreated cells (6.1% and 5.4% versus 7.9% and 5.3%, resp.). Similarly, no significant difference between US-treated and untreated cells was detected in the number of necrotic cells (5.4% versus 3.4%, resp.). These data exclude any deleterious effect of US treatment on DC viability and apoptosis.

Figure 5.

US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 do not alter DC viability. DC cultures treated with 3 cycles of US or left untreated were stained with annexin V and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. The x-axis and y-axis indicate the fluorescence intensities of annexin V binding and PI incorporation, respectively. Annexin+ or annexin/PI+ DC represented early and late apoptotic DC, whereas PI+ DC were necrotic DC. Representative experiment of five performed is shown.

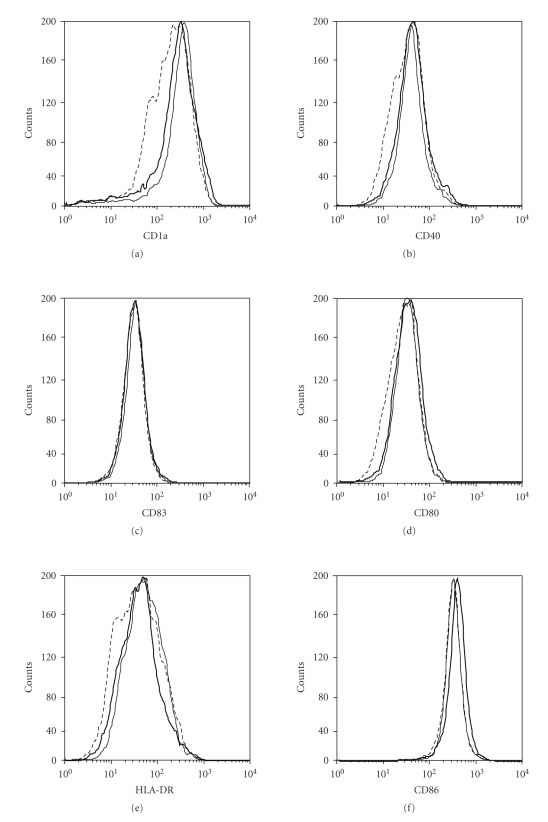

3.4. Treatment with US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 Does Not Affect Phenotype Nor Functional Maturation of DC

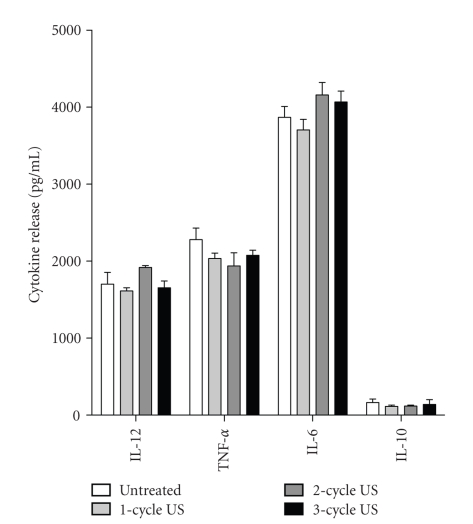

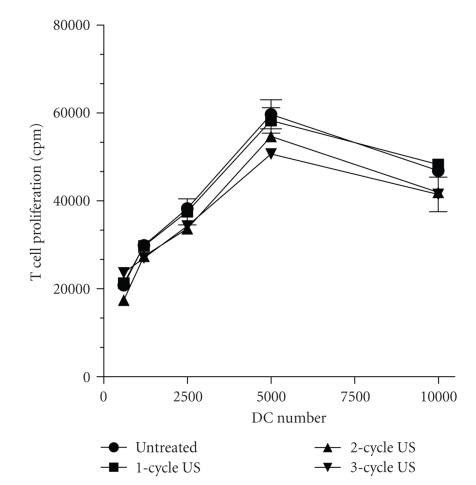

DC are professional antigen presenting cells able to generate primary immune responses. Under normal conditions, they reside as immature DC in peripheral tissues where, after antigen uptake and exposure to proinflammatory cytokines, undergo maturation and migrate to local lymph nodes [16]. This process is accompanied by functional and immunophenotypic changes characterized by the upregulation of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules, including CD80, CD86, and CD40, as well as by a substantial neoexpression of CD83, a key marker of DC maturation [16]. Mature DC enhance priming and activation of T lymphocytes and vigorously stimulate antigen-specific T cell responses. Due to the important role of DC on skin immune responses, we examined the potential effects of US on DC maturation, evaluated in terms of CD40, CD80, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR, and CD1a expression as well as their IL-12, TNF-α, Il-6 and IL-10 release. To this end, 5-day cultured DC were exposed or not to 3-cycle US, and then 24 hours treated with LPS, a potent stimulus for DC maturation. US treatment of mature DC (LPS-treated) did not alter the expression of the immune membrane molecule examined nor it modified their cytokine release profile (Figures 6 and 7). Finally, US influence on antigen presentation ability of DC was evaluated by analyzing the proliferation rate of naïve T lymphocytes in allogeneic MLR assay. Thus, increasing amounts of untreated or US-treated mature DC were cocultured with purified naive T cells, and proliferation evaluated in terms of [3H]-thymidine incorporation. As shown in Figure 8, 1–3 cycle US stimulation did not influence the alloantigen-presentation function of mature DC, which induced proliferation rate in T cells similar to that observed for untreated cells. As a whole, these data indicate that DC phenotype and function are not altered by US stimulation.

Figure 6.

Treatment with US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 does not change phenotypic maturation of DC. DC were generated from peripheral blood monocytes cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 for 6 days. At day 5, immature DC were treated or not with 3 cycles of US, and LPS (50 μg/mL) was added to promote maturation. After 24 hours incubation, DC were stained with FITC-conjugated Abs against the indicated surface molecules. Thin and bold black lines indicate US-treated or untreated mature DC, respectively. Dotted lines represent staining with matched isotype immunoglobulins. The x-axis and the y-axis indicate the relative cell number and fluorescence intensity, respectively.

Figure 7.

Treatment with US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 does not alter cytokine release from mature DC. 1–3 cycle US treatment was performed on mature DC cultures, whose supernatants were tested for IL-12, TNF-a, IL-6, and IL-10 content in ELISA. Results are expressed as mean picograms per 106 cells per mL ± SD of triplicate cultures.

Figure 8.

DC treated with US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 efficiently induce naïve T cell responses. Mature DC were treated with 1-cycle (square), 2-cycle (dot), or 3-cycle (triangle) US treatment or left untreated. Graded numbers of DC (x-axis) were cocultured in 96-well flat bottomed microplates with 2 × 105/well purified CD45RA+ allogenic T cell, whose [3H]-thymidine incorporation (y-axis) was measured after 5 days. Data are expressed as mean CPM ± SD of triplicates cultures.

3.5. Enhancement of Intensity of Low-Frequency US Alters the Survival and Immune Responses of Keratinocytes and DC

Previous studies demonstrated that the transdermal transport rate across skin is proportional to US intensity, although high-intensity US can produce significant thermal effects leading to erythema and dermal necrosis [9]. In order to identify a threshold value of US intensity at which cell viability and immunological functions of cultured keratinocytes and DC were altered and/or compromised, we treated cells with low-frequency US at intensity ranging from 0.15 to 7 W/cm2. US-treated keratinocytes were, then, analyzed for the exposure of apoptotic markers, ERK1/2 activation and the expression of immune mediators. DC treated with US at different intensities were also examined for apoptosis and immune phenotype. As shown in Table 1, US applied at intensities up to 2.3 W/cm2 did not substantially vary the apoptotic rate nor the levels of ERK1/2 activation in cultured keratinocytes. In contrast, at the intensity value of 5.0 W/cm2, the number of apoptotic cells started to increase (1.93-fold increase of apoptotic cell percentage versus untreated samples, Table 1), and at 7.0 W/cm2 cell viability was greatly compromised (3.54-fold increase of apoptotic cell percentage versus untreated samples, Table 1). In parallel, we could observe a slight, but significant, increase of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and α6β4 integrin, but not of HLA-DR in keratinocytes treated with US at the highest intensity values (Table 1). Of note, keratinocytes treated with US at 5 and 7 W/cm2 showed an increase of CXCL8 release as well as phospho-ERK1/2 expression (Table 1). In addition, no substantial differences of CXCL10, CCL2, IL-6, and TNF-α production could be observed in US-treated compared to unstimulated cells (Table 1). Similarly to keratinocytes, DC showed an enhanced cell mortality when treated with US at the highest intensities. In particular, apoptotic DC started to accumulate upon treatment with US at 5 W/cm2 (1.94-fold increase compared to untreated DC, Table 1), and substantially increase at 7.0 W/cm2 (3.21-fold increase compared to untreated DC, Table 1). Irradiation with US at intensity of 5.0 and 7.0 W/cm2 also determined a slight but significant increase of CD40 co-stimulatory molecule (Table 1). In contrast, we could not detect any variations in the expression of membrane CD1a, CD83, CD80, HLA-DR, and CD86 by US-irradiated compared to untreated DC (Table 1). Finally, the enhancement of intensity values of low-frequency US did not influence the release of the cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 by both immature (Table 1) and mature DC (data not shown).

Table 1.

Effects of low-frequency US at 0.15–7 W/cm2 intensity range on cultured keratinocytes and DC. Keratinocyte and DC cultures were treated with 42 KHz US at the indicated intensities for 7 minutes (1 cycle). Apoptotic cells were determined by annexin V/PI staining and FACS analysis. Apoptotic cell percentage (%) includes PI+, Ann V/PI+, as well as Ann V+ subpopulations. The expression of surface markers was revealed by performing staining with specific Abs and FACS analysis. Membrane molecule positivity is expressed as ΔMFI, which represents the mean fluorescence intensity of samples stained with specific Abs subtracted of the fluorescence of Ig-stained controls. Supernatants from keratinocyte and DC cultures were tested by ELISA to measure chemokine and cytokine contents. Phospho-ERK1/2 were revealed by Western blotting on lysates obtained from US-treated keratinocytes. Phopho-ERK1/2 amounts were calculated by densitometry and are expressed as fold induction (F.I.) in experimental relative to untreated samples, to which were given a value of 1.

| Keratinocytes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US intensity (W/cm2) | Apoptotic cells (%) | ICAM-1 (ΔMFI) | HLA-DR (ΔMFI) | α6β4 integrin (ΔMFI) | CXCL10 (pg/106 cells) | CCL2 (pg/106 cells) | CXCL8 (ng/106 cells) | Phopho-ERK1/2 (F.I.) | IL-6 (pg/106 cells) | TNF-α (pg/106 cells) |

| 0 (untreated) | 15.1 ± 1.9% | 5 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 | 61 ± 4 | 75 ± 9 | 61 ± 5 | 3 ± 0.02 | 1 | 0 | 71 ± 9 |

| 0.15 | 14.6 ± 2.3% | 5 ± 3 | 4 ± 1.5 | 62 ± 6 | 95 ± 10 | 70 ± 4 | 3.3 ± 0.17 | 0.9 ± 0.15 | 0 | 66 ± 8.5 |

| 0.66 | 16.05 ± 1.3% | 7 ± 2 | 5 ± 1.5 | 66 ± 3 | 100 ± 11 | 45 ± 7 | 3.4 ± 0.33 | 1.1 ± 0.08 | 0 | 83 ± 7 |

| 1.4 | 15.6 ± 2.2% | 8 ± 3 | 5 ± 3 | 62 ± 3.5 | 85 ± 9.5 | 77 ± 6 | 3.5 ± 0.32 | 1.1 ± 0.09 | 0 | 85 ± 9.5 |

| 2.3 | 16.6 ± 1.7% | 8 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 61 ± 5 | 77 ± 22 | 66 ± 9 | 3.70 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0 | 69 ± 5 |

| 5 | 29.1 ± 2.65%§ | 16 ± 3.5# | 6 ± 0.5 | 75 ± 3§ | 81 ± 8.5 | 39 ± 6 | 6.66 ± 0.7# | 1.6 ± 0.07§ | 0 | 79 ± 6.5 |

| 7 | 53.5 ± 4.1%# | 18.5 ± 2# | 4 ± 1 | 81 ± 5§ | 110 ± 13 | 81 ± 11 | 7.5 ± 0.5* | 1.9 ± 0.08# | 0 | 64 ± 9 |

| DC | ||||||||||

| US intensity (W/cm2) | Apoptotic cells (%) | CD1a (ΔMFI) | CD40 (ΔMFI) | CD83 (ΔMFI) | CD80 (ΔMFI) | HLA-DR (ΔMFI) | CD86 (ΔMFI) | IL-12 (pg/mL) | IL-6 (pg/mL) | TNF-α (pg/mL) |

| 0 (untreated) | 19.1 ± 2.05% | 201 ± 7 | 19 ± 0.9 | 15 ± 0.7 | 30 ± 2.3 | 117 ± 6 | 201 ± 16 | 0 | 5 ± 0.1 | 105 ± 10 |

| 0.15 | 17.1 ± 2.5% | 199 ± 9 | 16 ± 1 | 13 ± 0.8 | 31 ± 2.2 | 112 ± 13 | 203 ± 18 | 0 | 7 ± 0.3 | 85 ± 9 |

| 0.66 | 20.2 ± 2.1% | 210 ± 11 | 18 ± 0.9 | 17 ± 0.9 | 40 ± 2.7 | 114 ± 9.5 | 197 ± 19 | 0 | 6 ± 1.6 | 80 ± 9.1 |

| 1.4 | 19.9 ± 2.4% | 200 ± 12 | 20 ± 1.1 | 11 ± 1.1 | 38 ± 2.5 | 110 ± 11.5 | 210 ± 11 | 0 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 78 ± 7.1 |

| 2.3 | 23.1 ± 2.9% | 198 ± 15 | 23 ± 1.4 | 10 ± 1.1 | 31 ± 3 | 101 ± 8 | 204 ± 14 | 0 | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 125 ± 11 |

| 5 | 37.1 ± 2.8%§ | 170 ± 13 | 35 ± 2.1§ | 16 ± 0.9 | 37 ± 3.1 | 100 ± 16 | 201 ± 19 | 0 | 2 ± 0.9 | 78 ± 9.1 |

| 7 | 61.3 ± 3.8%# | 180 ± 9 | 37 ± 6§ | 18 ± 0.7 | 39 ± 3.1 | 120 ± 9.7 | 173 ± 16 | 0 | 10 ± 1.1 | 92 ± 8.1 |

§P < 0.05, versus untreated cells, #P < 0.01, versus untreated cells, *P < 0.001, versus untreated cells.

4. Discussion

The skin represents an advantageous portal for drug delivery, and its exposure to US is considered as an useful tool to enhance the transdermal transport by increasing cutaneous permeability to a variety of therapeutics [6–8]. Although sonophoresis has been a topic of extensive research in the last 15 years, information on US biological effects on the single skin cell components is limited. In this study, we investigated whether application of low-frequency US influenced the physiological and immune functions of human keratinocytes and DC in vitro. Low-frequency US were used at frequency (42 KHz) and intensity (0.15 W/cm2) values known to be effective in enhancing human skin permeation in vivo [12]. It has been widely documented that, during inflammatory skin reactions, following exposure to lymphokines, especially IFN-γ and TNF-α, epidermal keratinocytes become an important source of inflammatory molecules [14, 15]. For instance, activated keratinocytes can express very high levels of membrane molecules, including MHC Class II and ICAM-1, as well as cytokines and chemokines, such as CXCL8, responsible for the intraepidermal collection of neutrophils, and CXCL10 and CCL2, both aimed at T-cell recruitment [14]. In association to resident skin cells, migrating immune cells play a central role, especially in the initiation of cutaneous inflammatory responses [16]. Among them, dermal DC, together with resident skin Langerhans cells, can generate strong primary immune responses. DC reside in an immature form inside unperturbed skin, where they are adapted for capturing pathogens and processing antigens, eventually becoming able to stimulate naïve T cell proliferation and to promote T helper or cytotoxic responses [16, 20].

In this study, we demonstrated that application of US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 on cultured human keratinocytes did not perturb their normal viability nor induce the activation of ERK1/2 proteins, which are known to sustain proliferative and self-protective programs in keratinocytes [18]. In fact, the apoptotic and necrotic cell percentage as well as the ERK1/2 phosphorylation status did not vary between untreated and US-irradiated samples. In addition, we demonstrated that US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 did not alter their phenotype, evaluated in terms of surface expression of the β1 and α6β4 integrins, two proteins importantly involved in the formation of the epidermal structure [20], and of ICAM-1 and HLA-DR, two typical markers of immune-activated keratinocytes [14]. Moreover, US administered at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 did not influence the release of the chemokines CXCL10, CCL2, and CXCL8, abundantly secreted by IFN-γ plus TNF-α-activated keratinocytes, as well as the release of the cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α. However, we could also demonstrate that irradiation of keratinocytes with low-frequency US set at intensity values higher that 0.15 W/cm2, namely, at 5 and 7 W/cm2, determined substantial changes in survival and immune molecule expression in these cells. In fact, in these conditions, keratinocytes increased the apoptotic process and also the expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and α6β4 integrin. Of note, at the US intensity value of 5 and 7 W/cm2, CXCL8 and phospho-ERK1/2 were also upregulated in keratinocytes. Since both CXCL8 and phospho-ERK1/2 sustain keratinocyte growth and proliferation [14, 15, 18], the observed increase of these proteins could be evoked to counteract the proapoptotic/necrotic effects induced by US at high intensities. All these data support and are consistent with previous findings showing the safety of the low-frequency US at low intensity values. In fact, Boucaud et al. using optical and electron microscopy, showed that human skin samples exposed to US at intensities lower than 2.5 W/cm2 were morphologically similar to untreated skin, and that histological alterations, such as detachment of the epidermis and dermal necrosis, were detectable only after an exposure to continuous US at 4 W/cm2 [21]. In addition, no substantial structural changes and modifications were found in skin treated with US to enhance the topical delivery of tetanus toxoid [22] and antisense oligonucleotides [23]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that there is no difference in morphology and in mitogenic activities between US-treated and untreated skin-derived fibroblasts [24]. On the other hand, the enhancement of intensity of low-frequency US did not alter either the expression of HLA-DR, CXCL10, CCL2 or the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α. Indeed, previous findings demonstrated that US at a frequency of 1 MHz could upregulate both IL-1α and TNF-α in mouse epidermal keratinocytes in vivo, through a mechanism involving the enhancement of local calcium release [25]. This cytokine upregulation can also be due to the fact that mice skin is extremely sensitive to US, even at a low frequency, and responds to US with important structural damages, including the detachment of the outer layer of the stratum corneum and pore formation [26], in their whole responsible for the epidermal upregulation of inflammatory cytokines [27].

Similar to human keratinocytes, DC showed unaffected viability, immune function, and phenotype in response to US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2. In fact, annexin V/PI analysis allowed us to exclude any cytotoxic or proapoptotic effect of US on DC. In parallel, we found that low-frequency low-intensity US treatment did not influence the DC expression of the membrane molecules CD40, CD80, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR, and CD1a, or release of cytokines involved in DC maturation. The latter include IL-6, TNF-α, IL-12, and IL-10, which are crucial for driving differentiation of naïve T cells toward the IFN-γ-producing type 1 phenotype [20]. DC maturation correlates with their ability to present antigens to T lymphocytes, and, indeed, we demonstrated that the treatment with US at 42 KHz and 0.15 W/cm2 did not impair the DC immunostimulatory activity, as assessed by analysing the proliferation of allogeneic T lymphocytes in MLR assay. To our knowledge, these findings are the first demonstration that low-frequency US do not potentially alter the immune responses induced by DC and sustain the employment of US as neutral transducer for the transcutaneous immunization [21]. In fact, US have been used as physical adjuvant to enhance the delivery of vaccines (i.e., tetanus toxoid) into the mouse skin and, thus, to generate potent systemic immune responses [21]. In this vaccination system, other than facilitating immunogen penetration, US appeared to activate Langerhans cells, the antigen professional DC residing in the epidermis. Indeed, Langerhans cells could be induced to undergo maturation by the apoptotic bodies locally released by dying cells rather than a direct effect of US. Consistently, another study reported that barrier disruption induced Langerhans cell activation without migration to regional lymph nodes [28]. By contrast, the enhancement of US intensity to 5 and 7 W/cm2 caused a substantial increase of DC apoptotic rate. In these conditions, DC also showed a slight but significant increase of the expression of the co-stimulatory molecule CD40, and no changes in the levels of membrane CD1a, CD80, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR, nor of secreted IL-12, IL-6, and TNF-α. The upregulation of CD40 on DC membrane, not accompanied by the increase of the other stimulatory and co-stimulatory molecules, might not significantly influence T cell activation. However, further studies are needed to definitively establish whether low-frequency US at high intensities can influence DC-mediated immune responses.

In conclusion, the data collected in this paper demonstrate that US at low-frequency (42 KHz) and low-intensity (0.15 W/cm2) do not influence cell viability and immune functions of both keratinocytes and DC in vitro. Therefore, our results sustain the safety of the in vivo application of US having these physical parameters, as well as their employment for the transdermal delivery of drugs active in those immune-mediated skin disorders where keratinocytes and DC have a pathogenetic role. However, the enhancement of the intensity of low-frequency US determines an increase of the apoptotic rate of both keratinocytes and DC as well as of keratinocyte self-protective responses and DC CD40 expression. We identify at 5 W/cm2 the intensity value of low-frequency US at which the viability and immune functions of both keratinocytes and DC are altered in vitro. In order to guarantee the safety of US application in vivo, further studies, performed by irradiating whole human skin with low-frequency US at increasing intensities, and aimed at analyzing keratinocyte and DC expression of cell viability markers and immune-modulatory molecules, should be conducted.

Acknowledgment

The first two Authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Elias PM. Epidermal lipids, barrier function, and desquamation. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1983;80(supplement):44–49. doi: 10.1038/jid.1983.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee S, McAuliffe DJ, Flotte TJ, Kollias N, Doukas AG. Photomechanical transcutaneous delivery of macromolecules. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1998;111(6):925–929. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAllister DV, Wang PM, Davis SP, et al. Microfabricated needles for transdermal delivery of macromolecules and nanoparticles: fabrication methods and transport studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(24):13755–13760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2331316100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prausnitz MR, Lau BS, Milano CD, Conner S, Langer R, Weaver JC. A quantitative study of electroporation showing a plateau in net molecular transport. Biophysical Journal. 1993;65(1):414–422. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81081-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AC, Barry BW. Penetration enhancers. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2004;56(5):603–618. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tachibana K, Tachibana S. Transdermal delivery of insulin by ultrasonic vibration. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 1991;43(4):270–271. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1991.tb06681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitragotri S, Blankschtein D, Langer R. Ultrasound-mediated transdermal protein delivery. Science. 1995;269(5225):850–853. doi: 10.1126/science.7638603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith NB, Lee S, Maione E, Roy RB, McElligott S, Shung KK. Ultrasound-mediated transdermal transport of insulin in vitro through human skin using novel transducer designs. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2003;29(2):311–317. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00706-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitragotri S, Kost J. Low-frequency sonophoresis: a review. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2004;56(5):589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paliwal S, Mitragotri S. Ultrasound-induced cavitation: applications in drug and gene delivery. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 2006;3(6):713–726. doi: 10.1517/17425247.3.6.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushner J, IV, Blankschtein D, Langer R. Heterogeneity in skin treated with low-frequency ultrasound. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2008;97(10):4119–4128. doi: 10.1002/jps.21308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novario R, Tanzi F, Goddi A, et al. A new sonographic method for the evaluation of skin permeability changes after irradiation with low-frequency ultrasound. In: Medical Imaging: Ultrasonic Imaging and Signal Processing, vol. 6513; February 2007; San Diego, Calif, USA. pp. 1–7. Proceedings of SPIE. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitragotri S, Blankschtein D, Langer R. Transdermal drug delivery using low-frequency sonophoresis. Pharmaceutical Research. 1996;13(3):411–420. doi: 10.1023/a:1016096626810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albanesi C, Scarponi C, Giustizieri ML, Girolomoni G. Keratinocytes in inflammatory skin diseases. Current Drug Targets: Inflammation and Allergy. 2005;4(3):329–334. doi: 10.2174/1568010054022033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albanesi C, De Pità O, Girolomoni G. Resident skin cells in psoriasis: a special look at the pathogenetic functions of keratinocytes. Clinics in Dermatology. 2007;25(6):581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toebak MJ, Gibbs S, Bruynzeel DP, Scheper RJ, Rustemeyer T. Dendritic cells: biology of the skin. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60(1):2–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Federici M, Giustizieri ML, Scarponi C, Girolomoni G, Albanesi C. Impaired IFN-γ-dependent inflammatory responses in human keratinocytes overexpressing the suppressor of cytokine signaling 1. Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(1):434–442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pastore S, Mascia F, Mariotti F, Dattilo C, Mariani V, Girolomoni G. ERK1/2 regulates epidermal chemokine expression and skin inflammation. Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(8):5047–5056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Luca M, Pellegrini G, Zambruno G, Marchisio PC. Role of integrins in cell adhesion and polarity in normal keratinocytes and human skin pathologies. Journal of Dermatology. 1994;21(11):821–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1994.tb03296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corinti S, Fanales-Belasio E, Albanesi C, Cavani A, Angelisova P, Girolomoni G. Cross-linking of membrane CD43 mediates dendritic cell maturation. Journal of Immunology. 1999;162(11):6331–6336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boucaud A, Montharu J, Machet L, et al. Clinical, histologic, and electron microscopy study of skin exposed to low-frequency ultrasound. Anatomical Record. 2001;264(1):114–119. doi: 10.1002/ar.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tezel A, Paliwal S, Shen Z, Mitragotri S. Low-frequency ultrasound as a transcutaneous immunization adjuvant. Vaccine. 2005;23(29):3800–3807. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tezel A, Dokka S, Kelly S, Hardee GE, Mitragotri S. Topical delivery of anti-sense oligonucleotides using low-frequency sonophoresis. Pharmaceutical Research. 2004;21(12):2219–2225. doi: 10.1007/s11095-004-7674-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai J, Pittelkow MR. Physiological effects of ultrasound mist on fibroblasts. International Journal of Dermatology. 2007;46(6):587–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.02914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi EH, Kim MJ, Yeh B-I, Ahn SK, Lee SH. Iontophoresis and sonophoresis stimulate epidermal cytokine expression at energies that do not provoke a barrier abnormality: lamellar body secretion and cytokine expression are linked to altered epidermal calcium levels. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2003;121(5):1138–1144. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamashita N, Tachibana K, Ogawa K, Tsujita N, Tomita A. Scanning electron microscopic evaluation of the skin surface after ultrasound exposure. Anatomical Record. 1997;247(4):455–461. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199704)247:4<455::AID-AR3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood LC, Stalder AK, Liou A, et al. Barrier disruption increases gene expression of cytokines and the 55 kD TNF receptor in murine skin. Experimental Dermatology. 1997;6(2):98–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1997.tb00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strid J, Hourihane J, Kimber I, Callard R, Strobel S. Disruption of the stratum corneum allows potent epicutaneous immunization with protein antigens resulting in a dominant systemic Th2 response. European Journal of Immunology. 2004;34(8):2100–2109. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]