Abstract

Cardiolipin (CL) is an essential phospholipid component of the inner mitochondrial membrane. In the mammalian heart, the functional form of CL is tetralinoleoyl CL [(18:2)4CL]. A decrease in (18:2)4CL content, which is believed to negatively impact mitochondrial energetics, occurs in heart failure (HF) and other mitochondrial diseases. Presumably, (18:2)4CL is generated by remodeling nascent CL in a series of deacylation-reacylation cycles; however, our overall understanding of CL remodeling is not yet complete. Herein, we present a novel cell culture method for investigating CL remodeling in myocytes isolated from Spontaneously Hypertensive HF rat hearts. Further, we use this method to examine the role of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) in CL remodeling in both HF and nonHF cardiomyocytes. Our results show that 18:2 incorporation into (18:2)4CL is: a) performed singly with respect to each fatty acyl moiety, b) attenuated in HF relative to nonHF, and c) partially sensitive to iPLA2 inhibition by bromoenol lactone. These results suggest that CL remodeling occurs in a step-wise manner, that compromised 18:2 incorporation contributes to a reduction in (18:2)4CL in the failing rat heart, and that mitochondrial iPLA2 plays a role in the remodeling of CL's acyl composition.

Keywords: linoleic acid, phospholipid remodeling, phosphatidylglycerol, bromoenol lactone

Cardiolipin (CL, 1,3-bis[1′,2′-diacyl-3′-phosphoryl-sn-glycerol]sn-glycerol) is a unique tetra-acyl phospholipid found in energy-transducing biological membranes (1). In mammals, CL accounts for approximately 15% of mitochondrial phospholipid mass and localizes largely to the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), although it has also been identified in the outer mitochondrial membrane (2–4). Within the IMM, CL physically associates with a number of proteins involved in mitochondrial energetics, including cytochrome c oxidase and the F1F0 ATPase (5–7).

A substantial body of evidence supports the presence of CL as essential for mitochondrial respiratory function. Paradies et al. (8) reported that cytochrome c oxidase activity was restored only when delipidated mitochondrial membranes were reconstituted in the presence of CL, and Sedlak and Robinson (9) have shown that a loss of CL destabilizes the noncovalent connections between cytochrome c oxidase subunits VIa and VIb. In addition to its role in IMM protein activity, CL also serves as a proton trap (10), cytochrome c anchor (11, 12), is involved in protein import (13, 14), and is important for imparting a specific three-dimensional structure on the IMM (15).

The acyl composition and molecular symmetry of CL have received attention for their importance in proper CL function (6, 16, 17). In mammals, the majority of cardiac CL is enriched with the essential ω-6 fatty acid, linoleic acid (18:2) (2, 6, 16). Tetralinoleoyl CL [(18:2)4CL] accounts for 75–80% of total CL content in both rat and human cardiac mitochondria (2, 16). The notion that 18:2 is essential for CL's function in the mammalian heart is based on three independent observations. First, the vast majority of CL is remodeled from its de novo form to (18:2)4CL subsequent to its biosynthesis. Second, the high prevalence of (18:2)4CL over other CL species is unlikely if one considers the remodeling process to be random with respect to acyl selection, which suggests that the loading of CL with 18:2 is purposeful. Lastly and most importantly, a loss of (18:2)4CL, along with an increase in 18:2-deficient CL species, occurs in a number of cardiac disease states (6, 18). The disease most directly associated with a loss of (18:2)4CL is Barth syndrome, caused by an X-linked mutation in the tafazzin gene (19–22). Levels of 18:2 in cardiac CL also decline in congestive heart failure (HF) (16), ischemic HF (23, 24), and diabetes (25). Because (18:2)4CL seems to be important for myocardial energy homeostasis, a complete understanding of the CL remodeling process is essential in designing future treatments for patients with HF and other mitochondrial diseases.

The formation of (18:2)4CL is dependent on the coupling of CL biosynthesis and remodeling. The biosynthesis of CL occurs within the IMM (26–29), where nascent CL is formed from the condensation of phosphatidylglycerol (PG) and cytidinediphosphate-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG) in a reaction catalyzed by CL synthase (CLS) (for review, see 30, 31). Neither the acyl composition of PG and CDP-DAG nor the acyl specificity of CLS results in an enrichment of CL with 18:2 de novo; thus, nascent CL must be converted to (18:2)4CL through an acyl remodeling cycle. Presumably, the remodeling of CL occurs through a series of deacylation-reacylation reactions, though the details of CL remodeling in vivo remain in question (18, 30). To date, three enzymes have been identified that are capable of adding 18:2 to a monolysoCL (MLCL): tafazzin (32), MLCL-acyltransferase (MLCL-AT, 33), and acylCoA-lysocardiolipin acyltransferase (ALCAT-1, 34). None of these enzymes, however, possess phospholipase activity. In fact, very little research has examined the role of endogenous phospholipases in CL remodeling.

To the best of our knowledge, there are only two reports examining the role of mitochondrial phospholipases in CL remodeling. Mancuso et al. (35) created a murine model deficient in the functional form of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) γ (iPLA2γ, also PLA2GVIB), and a decrease in (18:2)4CL in these animals occurred concomitantly with symptoms of myocardial energetic disequilibrium. More recently, Malhotra et al. (36) examined the role of iPLA2β (also PLA2GVIA), reporting that iPLA2β is not necessary for CL remodeling, but does increase the MLCL/CL ratio in tafazzin-deficient Drosophila melanogaster. Because these two reports are the first of their kind, much is still unknown about iPLA2 in CL remodeling. As such, the purpose of this study was to first develop a method to examine CL remodeling at the level of the isolated rat cardiomyocyte, and thereafter, use this method to investigate potential alterations in CL remodeling in the Spontaneously Hypertensive HF (SHHF) rat as well as the potential remodeling role of iPLA2 in this model of cardiac stress. We report that the incorporation of 18:2 into (18:2)4CL in SHHF cardiomyocytes: a) occurs singly over time, b) is attenuated with the development of HF, and c) is partially sensitive to inhibition of iPLA2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All materials used in this study were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Co. with the following exceptions: Type-2 collagenase was purchased from Worthington, racemic bromoenol lactone (BEL) and the iPLA2γ-specific enantiomer R-BEL were purchased from Cayman Chemical Co., and carbon stable isotope linoleic acid (13C18-18:2, >98% isotope enrichment, abbreviated in the text as 13C-18:2) was purchased from Spectra Stable Isotopes (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories).

Animals

The SHHF rat is a model of human HF that is genetically predisposed to death from hypertrophic followed by dilated cardiomyopathy, the etiology of which has been described by McCune et al. (37). Briefly, female SHHF rats become hypertensive by approximately 3 months of age and this development progresses to overt hypertension by 5 months. Secondary to this hypertension, myocardial hypertrophy begins around 17 months of age and progresses to dilated cardiomyopathy between 23–25 months (38, 39). Female SHHF rats (colony kept at the University of Colorado by S.A.M.) were designated as nonHF or HF based on age (2–3 months and 21–23 months, respectively), left ventricular (LV) function as assessed by echocardiography, and the absence or presence, respectively, of at least one of the following symptoms: labored breathing, piloerection, or orthopnea. Aged-matched (3 months and ≥22 months) female Fisher Brown Norway (Fischer 344 x Brown Norway F1, FBN) rats (Harlan) were used in select experiments as an aging control. The FBN rat was chosen as an aging control, rather than the Fischer 344, Wistar, or Sprague Dawley rat, because the documented incidence of cardiovascular dysfunction and disease is milder and of later onset in FBN rats relative to the other strains (40–42). All animals were housed in groups of 2–3 on a 12:12 h light:dark cycle with ad libitum access to chow and water. The n values for each experiment are located within figure legends. All animal treatment was conducted in conformity with the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Use and Care of Laboratory Animals and in accordance with guidelines set forth on animal care at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Echocardiographic analysis

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed on all rats 2–5 days prior to euthanasia under inhaled isoflurane anesthesia (5% initial, 2% maintenance) using a 12 MHz pediatric transducer connected to a Hewlett Packard Sonos 5500 Ultrasound system. Short axis M-mode echocardiograms on the LV were obtained for measurement of LV internal diameters at diastole (LVIDd) and systole (LVIDs), fractional shortening (FS), ejection fraction (EF), anterior wall thickness in diastole (AWTd), and posterior wall thickness in diastole (PWTd) as previously described (43).

Cardiomyocyte isolation

Cardiomyocytes were isolated from whole hearts with modifications to methods previously described (44, 45). Animals received 2,000 units/kg body mass heparin and after 12 min were deeply anesthetized with 35 mg/kg sodium pentabarbitol, both through intraperitoneal injection. Hearts were rapidly excised, immersed in ice-cold saline, and cannulated by the aorta on a modified Langendorff perfusion apparatus. Hearts were perfused in a retrograde manner for 5 min with “buffer B” (described in refs. 44, 45), after which the perfusate was changed to a digestion buffer identical to the first, except containing 1.30 or 1.50 mg/ml type-2 collagenase (for nonHF and HF hearts, respectively), 1.30 mg/ml hyaluronidase, 100 μg/ml dialyzed albumin, and 55 μM CaCl2. When sufficiently digested (as determined by increases in coronary flow and softness to touch), hearts were cut from the cannula and the right ventricular free wall was removed. Remaining LV and septal tissue was cut into smaller pieces and teased apart with blunted glass pipette tips. Cells were washed once with a buffer identical to buffer B, except containing 100 μM CaCl2, and twice with medium 199 (37°C, pH 7.4, with 100 units/ml penicillin and 5 μg/ml gentamycin). After the final wash, cells were seeded on laminin-coated glass microscope coverslips in Springhorn medium (medium 199 with the addition of 2 mg/ml BSA, 100 nM insulin and (in mM): 2 carnitine, 5 creatine, 5 taurine, 1.3 glutamine, 2.5 sodium pyruvate, 10 2,3- butane dione monoxime; pH 7.70 before equilibration with 5% CO2) and incubated at 37°C for 2–3 h.

Cardiomyocyte treatment

For each experimental group, three laminin-coated glass coverslips plated with cardiomyocytes were bathed in Springhorn medium in 100 × 15 mm sterile Petri dishes (final volume 12 ml). The first group served as a control and was incubated with 0.17 mM fatty acid-free BSA and 0.1% DMSO vehicle. The second group of cells was incubated with BSA-bound 13C-18:2 such that the final concentrations were 1 mM 13C-18:2 and 0.17 mM BSA (a 6:1 18:2:BSA ratio), with 0.1% DMSO vehicle. The third group of cells was treated in a manner similar to the second group, but was incubated for 30 min with 10 μM BEL in 0.1% DMSO prior to the addition of BSA-bound 13C-18:2 (13C-18:2 + BEL). The final group was treated exactly the same as the third group, except 5 μM of the iPLA2γ-specific BEL enantiomer, R-BEL, was used instead of the racemic BEL mixture (13C-18:2 + R-BEL). Data was not shown for a fifth, “BEL control” group (10 μM BEL in 0.1% DMSO, 0.17 mM BSA), because this treatment did not result in any measurable effects. In the event that incubations lasted longer than 24 h, Springhorn medium and all necessary chemicals were replaced every 24 h. Myocytes were photographed preceding and subsequent to each treatment period using a Sony Cybershot DSC-S75 digital camera with a VAD-S70 adaptor ring under an inverted light microscope at 100× magnification.

Cardiomyocyte harvest and lipid extraction

Following treatment, myocytes were scraped from coverslips and centrifuged at 1600 g for 5 min at room temperature. Pelleted myocytes were resuspended in HPLC-grade methanol and stored at −20°C until lipid extraction. Lipids were extracted according to Bligh and Dyer (46) and subject to ESI-MS for phospholipid content analysis.

Phospholipid analysis

Singly-ionized CL and PG species were quantified by ESI-MS as described by Sparagna et al. (46). Tetramyristoyl CL [(14:0)4CL] was included as an internal standard to verify the quality of the spectra. Differences in cell yield between groups were controlled for by expressing each analyte as a fraction of its total respective phospholipid content. The specific acyl compositions, mass to charge ratios (m/z), and text abbreviations for all phospholipids presented can be found in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin species measured using ESI mass spectrometry

| Phospholipid Species | Mass to Charge Ratio (m/z) | Abbreviation in Text |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylglycerol | ||

| 1-, 2-di-13C-linoleoyl phosphatidylglycerola | 805.5 | (13C-18:2)2PG |

| 1-13C-linoleoyl-2-oleoyl phosphatidylglycerol | 789.5 | (13C-18:2)(18:1)PG |

| 1-13C-linoleoyl-2-palmitoyl phosphatidylglycerol | 763.5 | (13C-18:2)(16:0)PG |

| 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl phosphatidylglycerol | 747.5 | (16:0)(18:1)PG |

| 1-13C-linoleoyl-2-linoleoyl phosphatidylglycerol | 787.5 | (13C-18:2)(18:2)PG |

| Cardiolipin | ||

| 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-tetralinoleoyl cardiolipin | 1448.0 | (18:2)4CL |

| 1-13C-linoleoyl, 2-, 3-, 4-trilinoleoyl cardiolipin | 1466.0 | (13C-18:2)(18:2)3CL |

| 1-, 2-di-13C-linoleoyl, 3-, 4-dilinoleoyl cardiolipin | 1484.0 | (13C-18:2)2(18:2)2CL |

| 1-, 2-, 3-tri-13C-linoleoyl, 4-linoleoyl cardiolipin | 1502.0 | (13C-18:2)3(18:2)CL |

| 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-tetra-13C-linoleoyl cardiolipinb | 1520.0 | (13C-18:2)4CL |

| 1-, 2-, 3-trilinoleoyl, 4-docosahexaenoyl cardiolipinb | 1496.0 | (18:2)3(22:6)CL |

Singly-ionized CL and PG species were quantified using ESI mass spectrometry. 16:0, palmitoyl; 18:1, oleoyl; 18:2, linoleoyl; 13C-18:2, carbon stable isotope linoleoyl; 22:6, docosahexaenoyl.

In all phospholipids presented, acyl composition is arbitrary with respect to sn- position.

The atomic mass of this phospholipid is shared with phospholipids containing alternate acyl-compositions (see ref. 46). The acyl composition presented here represents the most common species.

CL

In the first experiment, cardiomyocytes were incubated under control conditions for 48 h to verify that the CL composition in cell culture matched typical cardiac CL in the intact SHHF rat heart (16). To do this, we quantified the two predominant CL species in isolated SHHF cardiac mitochondria: (18:2)4CL and (18:2)3(22:6)CL (46). In the second experiment, we wished to examine the incorporation of 13C-18:2 into CL over a period of 72 h. As such, we quantified five different species of tetra-18:2 CL: (18:2)4CL, (13C-18:2)(18:2)3CL, (13C-18:2)2(18:2)2CL, (13C-18:2)3(18:2)CL, and (13C-18:2)4CL. Each tetra-18:2 CL species contained a different number of 18:2 and 13C-18:2 moieties; thus, we were able to monitor the replacement of endogenous 18:2 in (18:2)4CL with 13C-labeled 18:2. In the final experiment, cardiomyocytes were incubated in 10 μM BEL or 5 μM R-BEL for 30 min preceding the addition of 13C-18:2 to solution. Myocytes remained in culture for up to 24 h, after which we examined 13C-18:2 uptake into (18:2)4CL by expressing (13C-18:2)(18:2)3CL as a fraction of total CL content, or by determining the initial rate of (13C-18:2)(18:2)3CL formation using the linear coefficient of a best-fit quadratic equation. For all experiments, total CL was calculated as previously described (16).

PG

To determine whether our method monitors the incorporation of 13C-18:2 into (18:2)4CL at the level of CL remodeling or CL biosynthesis, we examined 13C-18:2 content in PG following up to 72 h of incubation with 13C-18:2 or 24 h of incubation with 13C-18:2 plus BEL or R-BEL. For these experiments, we quantified five different species of PG (listed in Table 1) and expressed each as a fraction of their sum, which accounts for the vast majority of PG detected in the mass spectra.

Statistical analysis

For echocardiography data, data corresponding to control CL composition, and data involving the incorporation of 13C-18:2 into PG, a multivariate ANOVA was used to test for an omnibus F-ratio. Rates of CL remodeling in the presence of BEL or R-BEL were evaluated with a two-factor repeated measures ANOVA. A two-factor ANOVA was used to examine differences in remodeling between young and aged SHHF and FBN cardiomyocytes. In the event of a statistically significant F-ratio, post hoc multiple comparisons were made using Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference or simple comparisons. Where necessary, absolute p-values were adjusted with a Bonferroni correction. In all cases, α = 0.05 was set as the marker for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Cardiac function and cardiomyocyte viability

Cardiac function.

Rats were subjected to echocardiography to assess LV function preceding sacrifice. SHHF echocardiography data clearly demonstrate significant LV hypertrophy and systolic dysfunction in HF compared with nonHF animals (Table 2), consistent with the late stages of hypertensive heart disease and early HF in this animal model (47). In contrast, aged FBNs exhibited neither LV thickening nor functional deficits when compared with young FBNs, and the LV morphological and functional values reported here are consistent with previously reported values for this animal strain (48).

TABLE 2.

Analysis of left ventricular function in young and aged SHHF and FBN rats

| Group | LVIDd (mm) | LVIDs (mm) | FS (%) | EF (%) | AWTd (mm) | PWTd (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHHF | Non-HF | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 39 ± 2 | 77 ± 2 | 1.4 ± 0.1# | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| HF | 8.0 ± 0.2 | 6.1 ± 0.2 | 24 ± 2 | 56 ± 3 | 1.9 ± 0.1* | 1.8 ± 0.1* | |

| FBN | Young | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 54 ± 3 | 89 ± 3 | 1.5 ± 0.04 | 1.5 ± 0.06 |

| Aged | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 54 ± 3 | 89 ± 2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.06* |

Data for various markers of LV morphology and function are presented as mean ± SE (n = 8 per group SHHF, n = 4–6 per group FBN). LVIDd, left ventricular internal diameter in diastole; LVIDs, left ventricular internal diameter in systole; FS, fractional shortening; EF, ejection fraction; AWTd, left ventricular anterior wall thickness in diastole; PWTd, left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole. *P < 0.05 versus SHHF nonHF; #P < 0.05 versus SHHF HF; †P < 0.05 versus FBN young; ‡P < 0.05 versus FBN aged within same column.

Cardiomyocyte viability.

Isolated myocytes were photographed preceding and subsequent to each treatment period. No large differences in myocyte viability were witnessed between the pre- and post-treatment time points (representative micrographs shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Cardiomyocyte viability. Cardiomyocytes were isolated and seeded on glass microscope coverslips. Isolated cells from either nonHF or HF rats were photographed preceding (Pre-) and subsequent to (Post-) each treatment period.

Cardiolipin composition in isolated myocytes

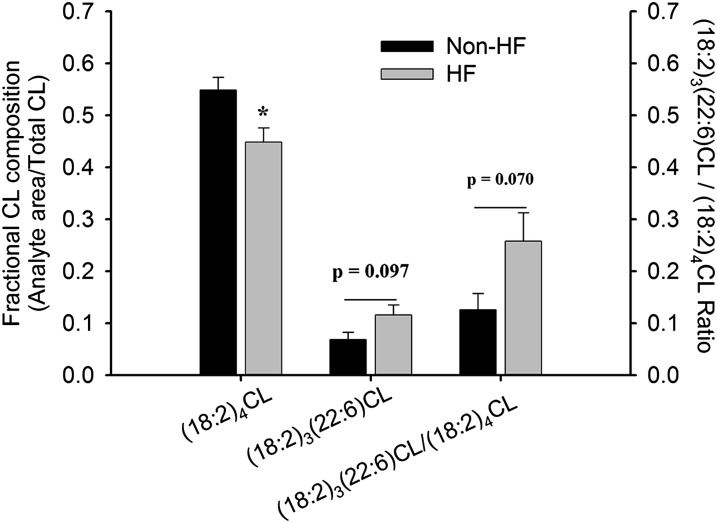

Figure 2 shows (18:2)4CL, (18:2)3(22:6)CL, and the ratio of the two species in SHHF nonHF and HF myocytes after 48 h under control conditions. Consistent with CL composition in mitochondria isolated from whole hearts (16), (18:2)4CL is depressed with the development of HF (P < 0.05), along with trends for statistically significant increases in (18:2)3(22:6)CL and the (18:2)3(22:6)CL / (18:2)4CL ratio (P = 0.097 and 0.070, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Cardiolipin composition in isolated cardiomyocytes. Isolated cardiomyocytes from either nonHF or HF SHHF rats were incubated under control conditions for 48 h. Following incubation, (18:2)4CL and (18:2)3(22:6)CL content were analyzed and expressed as a fraction of total CL. Data presented as mean ± SE (n = 4 nonHF, n = 4 HF). * P < 0.05 versus nonHF.

Incorporation of 13C-18:2 into (18:2)4CL

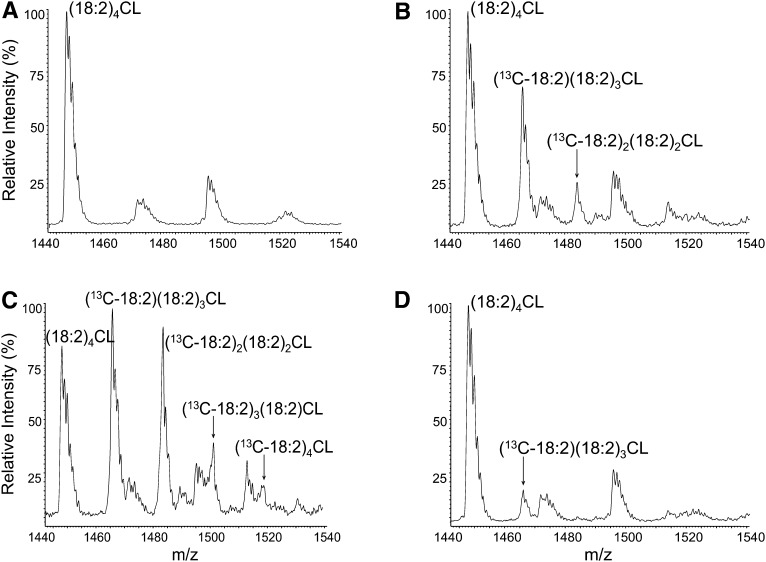

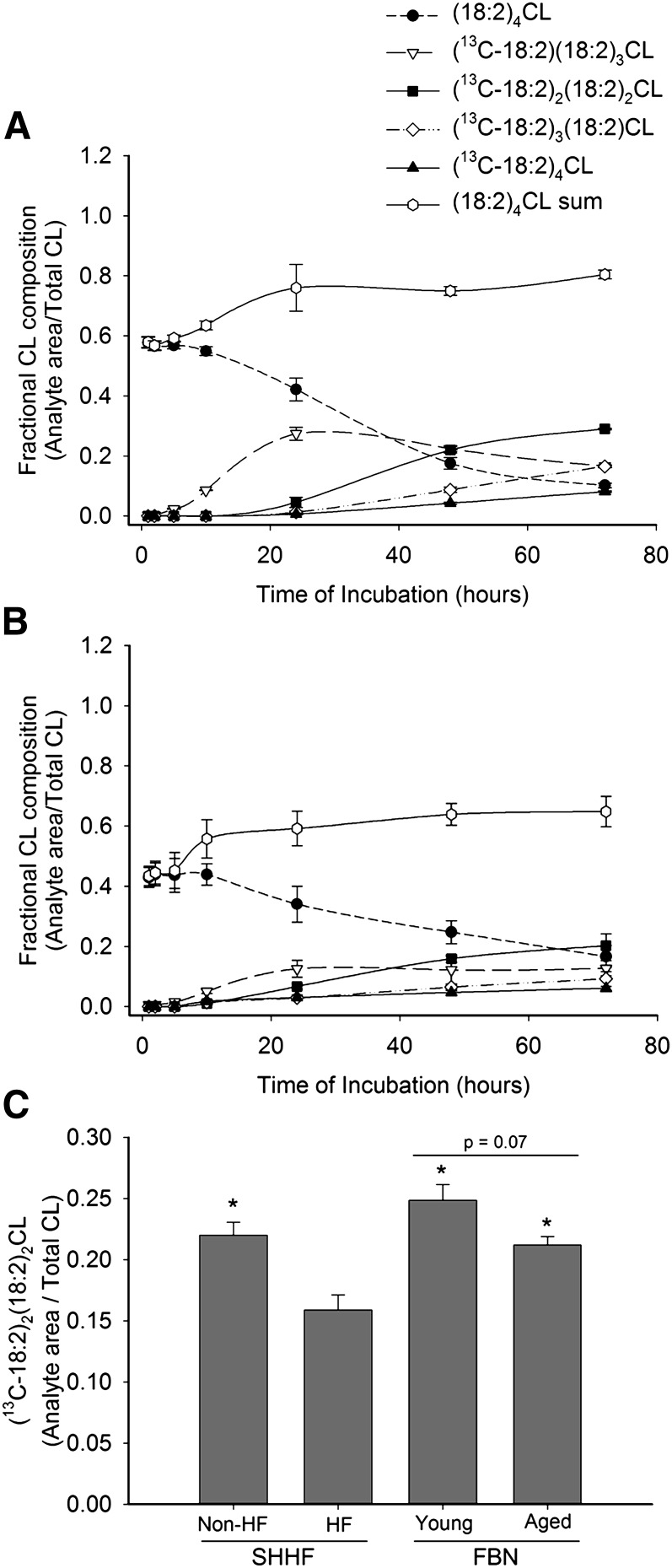

In a time-course experiment, we incubated SHHF cardiomyocytes in 13C-18:2 for up to 72 h, monitoring the incorporation of 13C-18:2 into (18:2)4CL via the formation of 13C-labeled CL species. The results from these experiments are presented in Figs. 3 and 4. Figure 3 shows representative ESI mass spectra from nonHF myocytes under varying conditions. As shown, 13C-labeled (18:2)4CL peaks not present under control conditions (Fig. 3A) appear after 24 h and 48 h incubations with 13C-18:2 (Figs 3B and 3C, respectively), and this appearance is partially prevented by preincubation with BEL (Fig. 3D). Figure 4 shows the quantitative results from these spectra for nonHF (Fig. 4A) and HF (Fig. 4B) cardiomyocytes. In addition to 13C-labeled (18:2)4CL species, Fig. 4A and 4B also display the levels of endogenous (18:2)4CL and the sum of all labeled and nonlabeled (18:2)4CL species throughout the incubation period. With added 13C-18:2, nonHF SHHF myocytes were able to raise and sustain total (18:2)4CL levels to 80.4 ± 1.5% of total CL, whereas levels in myocytes isolated from HF animals peaked at 64.8 ± 5.1%. Furthermore, the rate of 13C-18:2 incorporation into (18:2)4CL is attenuated in HF myocytes, as all 13C-labeled (18:2)4CL species peak at higher values in nonHF SHHF myocytes as compared with HF myocytes.

Fig. 3.

Cardiolipin mass spectra in isolated cardiomyocytes. Lipids were extracted from nonHF SHHF myocytes and detected using ESI-MS. A–D show representative spectra for the following conditions: (A) Control, 48 h; (B) 13C-18:2, 24 h; (C) 13C-18:2, 48 h; (D) 13C-18:2 + BEL, 24 h.

Fig. 4.

Incorporation of 13C-18:2 into (18:2)4CL. Isolated cardiomyocytes from nonHF and HF SHHF rats were incubated in 13C-18:2 for up to 72 h. At different time intervals after the initial incubation, cells from (A) nonHF and (B) HF SHHF rat hearts were harvested and five different species of (18:2)4CL, as well as their sum, were analyzed and expressed as a fraction of total CL. Data presented as mean ± SE. n = 3–8 for each time point for both nonHF and HF. (C) Levels of (13C-18:2)2(18:2)2CL after 48 h of incubation in 13C-18:2 were taken from the graphs in (A) and (B) and plotted against one another, along with corresponding data from young and aged FBN myocytes. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 4 nonHF SHHF, 3 HF SHHF; 4 young FBN, 6 aged FBN). * P < 0.05 versus SHHF HF.

To examine whether the decreased rate of 13C-18:2 incorporation into (18:2)4CL was caused by HF per se or due to aging, we quantified the amount of doubly-labeled CL [(13C-18:2)2(18:2)2CL] in cardiomyocytes isolated from both young and aged FBNs after 48 h of incubation in 13C-18:2. Figure 4C shows that nonHF SHHF, young FBN, and aged FBN myocytes produced significantly more (13C-18:2)2(18:2)2CL than HF SHHF myocytes (all pair-wise P < 0.05). Young FBN myocytes had the highest absolute content of doubly-labeled CL after 48 h (24.9% of total CL), whereas aged FBN and nonHF SHHF myocytes had intermediate values (21.2% and 22.0%, respectively) compared with HF SHHF myocytes (15.9%). Notably, there was a trend for decreased (13C-18:2)2(18:2)2CL content in aged FBN animals when compared with young FBN animals (P = 0.07).

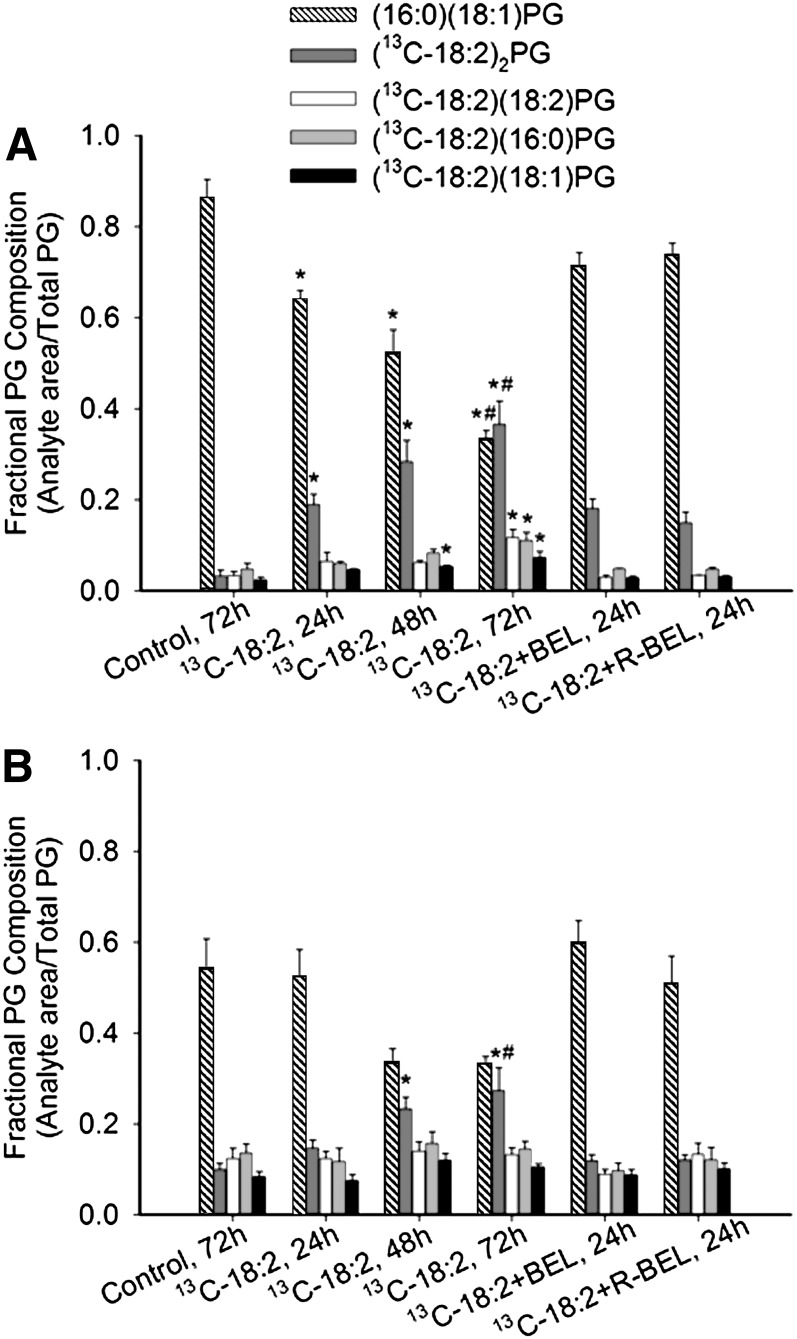

Incorporation of 13C-18:2 into PG

To verify that the measured incorporation of 13C-18:2 into (18:2)4CL was due to CL remodeling and not an artifact of 13C-18:2 content in the biosynthetic pathway, we examined 13C-18:2 incorporation into PG in nonHF and HF SHHF myocytes. Levels of the predominant species of endogenous PG, (16:0)(18:1)PG (49), progressively declined throughout 72 h of incubation with 13C-18:2 in nonHF (P < 0.05; Fig. 5A), and trended to decline after 48 h and 72 h in HF (Fig. 5B). Doubly-labeled PG [(13C-18:2)2PG] increased in cells from both nonHF and HF animals over time; furthermore, (13C-18:2)(18:2)PG, (13C-18:2)(16:0)PG, and (13C-18:2)(18:1)PG levels were elevated in nonHF, but not HF, myocytes after 72 h. In both nonHF and HF myocytes, the addition of neither BEL nor R-BEL to the 13C-18:2-containing medium resulted in any significant changes (all pair-wise P > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Incorporation of 13C-18:2 into phosphatidylglycerol. Cardiomyocytes isolated from (A) nonHF and (B) HF SHHF rat hearts were incubated in 13C-18:2, 13C-18:2 + BEL, or 13C-18:2 + R-BEL for up to 72 h. Incorporation of 13C-18:2 into PG was measured by quantifying different species of PG with either 16:0, 18:1, 18:2, or 13C-18:2. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 4). * P < 0.05 versus control value within analyte; # P < 0.05 versus 13C-18:2, 24 h value within analyte.

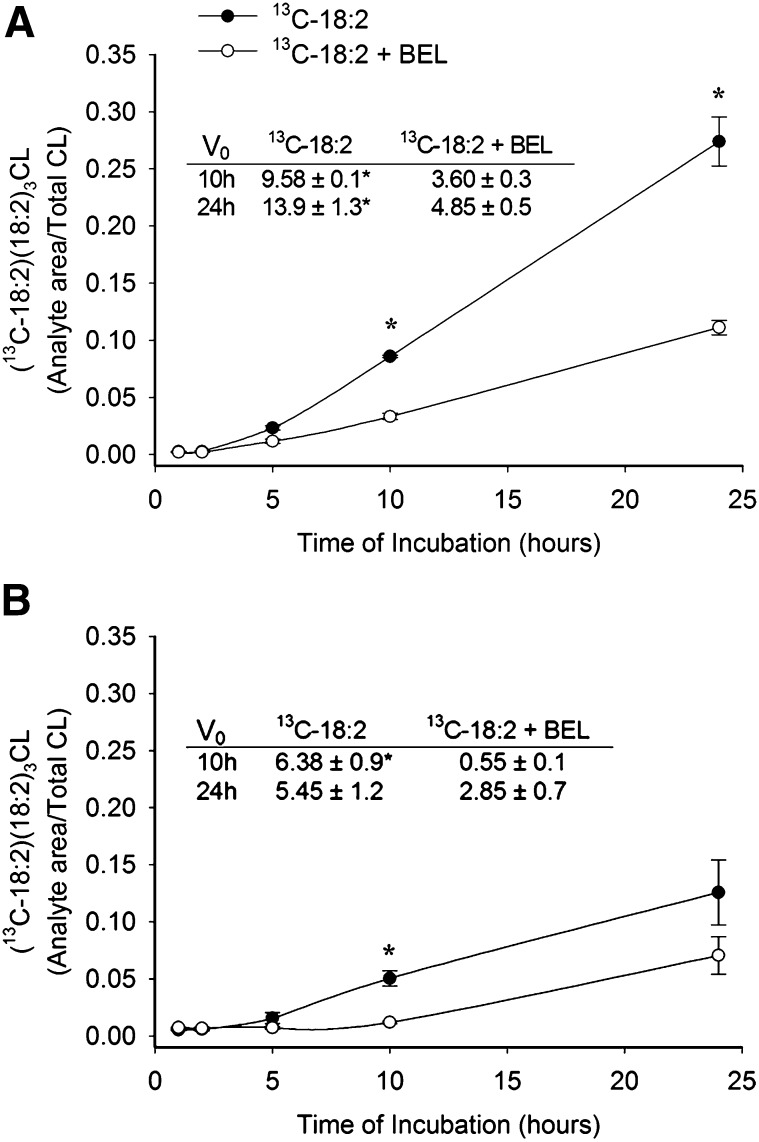

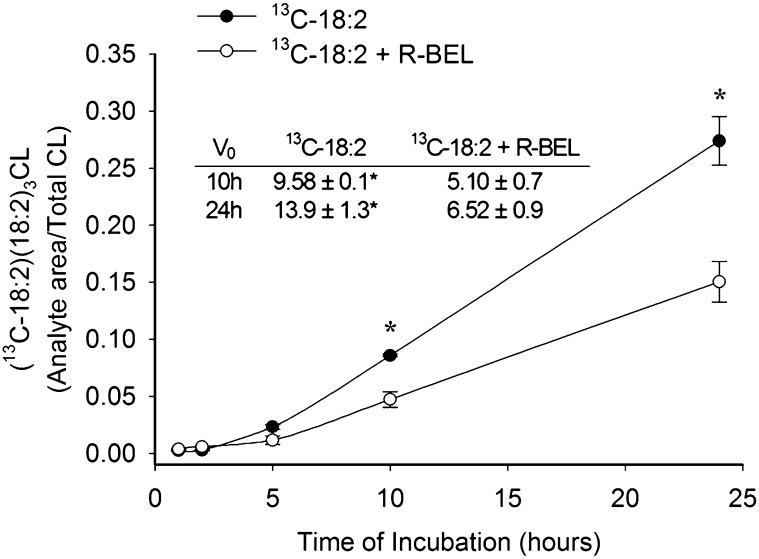

Incorporation of 13C-18:2 into (18:2)4CL is partially iPLA2-dependent

We examined 13C-18:2 incorporation into singly-labeled CL [(13C-18:2)(18:2)3CL] in the presence of the iPLA2 inhibitor, BEL. Preincubation with 10 μM BEL attenuated 13C-18:2 incorporation in myocytes isolated from both nonHF and HF rat hearts for up to 10 h of incubation (Fig. 6A, B). Interestingly, the percent of total 13C-18:2 incorporation inhibited by BEL after 10 h was significantly less in nonHF versus HF (61.2 ± 2.9% and 79.6 ± 2.3%, respectively, P < 0.01). After 24 h of incubation, 13C-18:2 incorporation was still sensitive to BEL in nonHF myocytes; however, BEL sensitivity was diminished in myocytes isolated from HF SHHF rats. To further quantify the differential effects of BEL treatment in nonHF and HF, we measured the initial rates of singly-labeled CL formation after 10 h and 24 h of incubation in 13C-18:2 with and without BEL. In both nonHF and HF, the rate of singly-labeled CL formation was significantly reduced by BEL throughout the first 10 h of incubation; however, this incorporation was sensitive to BEL after 24 h in only nonHF myocytes (Fig. 6 table inserts). Finally, because data from Mancuso et al. (35) suggested a role of iPLA2γ in CL remodeling, we examined 13C-18:2 incorporation in the presence of the iPLA2γ-specific enantiomer, R-BEL. R-BEL had very similar effects on CL remodeling when compared with BEL in nonHF myocytes, and was capable of significantly preventing 13C-18:2 incorporation into singly-labeled CL following up to 24 h of incubation with respect to both total incorporation over 24 h and the initial rate of incorporation (Fig. 7). Racemic BEL and R-BEL had the same effects on the initial rates of incorporation and resulted in similar rates of 18:2 incorporation after both 10 h and 24 h of incubation (P > 0.05). Neither 10 μM BEL nor 5 μM R-BEL had an effect on cardiomyocyte viability during the 24 h treatment period (micrographs not shown).

Fig. 6.

Effect of iPLA2 inhibition on incorporation of 13C-18:2 into (13C-18:2)(18:2)3CL. Myocytes from either (A) nonHF or (B) HF SHHF rat hearts were incubated with 13C-18:2 following 30 min preincubation with 10 μM BEL. Cells were harvested at select time points and (13C-18:2)(18:2)3CL was quantified and expressed as a fraction of total CL. Table inserts show initial rates of (13C-18:2)(18:2)3CL formation after 10 h and 24 h periods of incubation with 13C-18:2. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 4–8). * P < 0.05 versus 13C-18:2 + BEL at same time point.

Fig. 7.

Effect of iPLA2γ inhibition on incorporation of 13C-18:2 into (13C-18:2)(18:2)3CL. NonHF myocytes were incubated in 5 μM R-BEL for 30 min prior to the addition of 13C-18:2 to solution. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 4). * P < 0.05 versus 13C-18:2 + R-BEL at the corresponding time point.

DISCUSSION

The maintenance of cardiac (18:2)4CL levels appears to be extremely important in mitochondrial energetics; however, the exact mechanism by which CL is remodeled to contain 18:2 remains to be determined. We conducted this study, first, to develop a method for monitoring CL remodeling in the isolated rat cardiomyocyte, and next, to use this method to examine both changes in CL remodeling in the context of HF and the role of iPLA2 in CL remodeling. We presented data that show CL is remodeled singly with respect to its fatty-acyl moieties; the rate of 18:2 incorporation into CL is depressed in HF; and iPLA2 is partly involved in the incorporation of 13C-18:2 into (18:2)4CL in SHHF cardiomyocytes.

In this report, we presented a new method for studying the remodeling of CL at the level of the individual cardiomyocyte. Although we argue that our method monitors the incorporation of 13C-18:2 at the level of CL remodeling rather than CL biosynthesis, we reported 13C-containing PG species in our cultures following up to 72 h exposure to 13C-18:2. Because it is CL's precursor, an isotopic enrichment of PG suggests that our method monitors not CL remodeling, but the formation of isotopic CL from isotopic PG. We believe this data is misleading and that our method does monitor CL remodeling for the following reasons: first, the only species of PG containing 13C-18:2 after 24 h was doubly-labeled PG, and this phospholipid could not condense with CDP-DAG to form the major isotopic CL species at 24 h, (13C-18:2)(18:2)3CL. We believe the increase of doubly-labeled PG, which occurs concomitantly with a loss of endogenous (16:0)(18:1)PG, represents a remodeling of PG by mass-action. The accumulation of (13C-18:2)2PG suggests that it may not be a substrate for CLS. Although human CLS expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae can use (18:2)2PG to synthesize CL (50), rat cardiomyocyte CLS exhibits different substrate specificity than human CLS (51). Thus, it is possible that rat CLS cannot use (13C-18:2)2PG in the condensation reaction. Second, the 13C-labeled PG species that could give rise to singly- or triply-labeled CL did not increase until 72 h, whereas these CL species were detected before 72 h. Finally, the incorporation of 13C-18:2 into CL was sensitive to inhibition of iPLA2, whereas the incorporation of 13C-18:2 into PG was not. Therefore, the incorporation of 13C-18:2 into (18:2)4CL in this method appears to occur largely through remodeling CL and not simply by increasing 13C-18:2 content in CL de novo.

Presumably, the remodeling of nascent CL to (18:2)4CL occurs through a series of four discreet deacylation-reacylation cycles, such that MLCL is the only necessary intermediate. In fact, dilysoCL is not readily acylated to CL in isolated mitochondria (52). As far as we know, however, there is no direct evidence for a step-wise incorporation of 18:2 into CL. The results from our time-course experiment are the first to show that CL is remodeled in this step-wise manner. Rather than the sporadic appearance of 13C-labeled CL with one, two, three, or four 13C-18:2 moieties, the incorporation of 13C-18:2 into (18:2)4CL occurs singly over time.

There exists a large descriptive precedent documenting abnormal CL composition in the context of disease (6, 16, 20, 53); however, aside from Barth syndrome, no research has resulted in a mechanism for this decline. In this report, we have shown that 18:2 incorporation into CL is attenuated in myocytes isolated from failing rat hearts. Total (18:2)4CL levels peaked at approximately 65% of total CL in HF myocytes, which was much lower than the corresponding value (80%) in nonfailing myocytes. These observations show that the failing myocardium has an attenuated ability to traffic and/or incorporate 18:2 into CL. Interestingly, the incorporation of 18:2 into PG was also lower in HF myocytes, indicating that acyl-chain remodeling abnormalities are not limited to CL in the failing rat heart.

In a recent two-part publication, Schlame and colleagues (54, 55) provided evidence that the acyl composition of CL depends more on the composition of the local lipid environment than the acyl specificity of CL remodeling enzymes (e.g., tafazzin). We have previously reported a 97% reduction in tafazzin transcript in the failing SHHF rat heart (56) and have shown here that, even in the presence of ample substrate, HF cardiomyocytes are unable to raise (18:2)4CL levels to those of nonHF myocytes or values reported in healthy rat and human cardiac mitochondria (6, 16). Thus, it appears that the decline in tafazzin transcript may explain the inability of HF myocytes to load CL with 18:2. In our previous publication, we also reported a 5-fold increase in MLCL-AT activity in HF (56), which may represent a compensatory response to the reduction in tafazzin content. Regardless of this, HF myocytes were still unable to properly remodel CL; therefore, we postulate that in the absence of tafazzin, the bioavailability of 18:2-CoA for MLCL-AT acyl transfer may be regulated by an additional, currently unknown mechanism.

In addition to alterations in CL acyl composition during disease states, data also exist demonstrating declines in 18:2 content in CL with age (57). To investigate a potential aging effect on CL remodeling, we measured 18:2 incorporation into (18:2)4CL in a nonpathological model of aging, the FBN rat. Both young and aged FBN myocytes incorporated 18:2 into CL more readily than HF SHHF myocytes. Although these data suggest that attenuated CL remodeling is associated only with HF, we also noted a trend for lower 18:2 incorporation with age in FBN myocytes. Overall, our data suggest that both aging and the development of HF may impact CL remodeling, although the relative reduction due to aging alone is only half that due to the development of HF (14.7% and 27.7% reductions in aged FBN and HF SHHF myocytes, respectively).

The experiments in which we inhibited iPLA2 in the presence of 13C-18:2 yielded a number of novel results. First, our data suggest CL remodeling is partially iPLA2-dependent for up to 10 h in both nonHF and HF SHHF rat hearts, which is consistent with data put forth by Mancuso et al. (35). Interestingly, the percent of (13C-18:2)(18:2)3CL formation that is inhibited by BEL after 10 h of incubation is significantly greater in HF versus nonHF myocytes. These results indicate a potential increase in the quantity or activity of iPLA2 in the failing myocardium. Theoretically, increased phospholipase activity would be cytoprotective by preventing an accumulation of lipid peroxidation end products; however, prior research on the role of iPLA2 in models of cellular stress have yielded conflicting results. Williams and Gottlieb (58) reported that inhibition of iPLA2 during ischemia reduced mitochondrial phospholipid loss and was cardioprotective, whereas Seleznev et al. (59) reported that the presence of iPLA2 was cytoprotective during apoptotic induction by staurosporine. In our model of HF, increased iPLA2 activity may be beneficial to the mitochondrial membrane in the absence of other abnormalities; however, when coupled with a lack of lysophospholipid reacylation (e.g., reduction in tafazzin) increased iPLA2 activity may result in the net degradation of CL or other mitochondrial phospholipids. Pretreatment of cardiomyocytes with BEL was more potent in HF myocytes for the first 10 h, but after 24 h of incubation, BEL-sensitive CL remodeling disappears in HF, but not in nonHF. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their derivatives are known ligands for nuclear receptors (60–62) and the apparent loss of iPLA2-dependent CL remodeling may be caused by upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor binding and alterations in cellular levels of lipid-metabolizing enzymes.

Because Mancuso et al.'s ablation of the γ-isoform of iPLA2 resulted in CL abnormalities, we also treated myocytes with R-BEL in the presence of 13C-18:2. Specific inhibition of iPLA2γ resulted in similar effects on 18:2 incorporation in nonHF myocytes with respect to total isotope incorporation and the initial rate of 18:2 incorporation, consistent with the notion that iPLA2γ is the calcium-independent phospholipase isozyme involved in remodeling CL. Although iPLA2γ seems to be involved in CL remodeling, its specific role in the process is still unknown. Namely, does iPLA2γ directly hydrolyze CL to MLCL for acylation, or is it involved in the remodeling of other glycerophospholipids that act as 18:2 donors for CL remodeling? We have shown that iPLA2γ does not remodel PG; however, its potential role in remodeling 18:2 donors such as phosphatidylcholine or phosphatidylethanolamine (32) remains to be determined.

The use of BEL as an inhibitor of iPLA2 is somewhat controversial. Although BEL's selective nature for iPLA2 over cytosolic PLA2 or secretory PLA2 is well accepted (63–65), previous investigators have warned against the use of BEL as a specific inhibitor of iPLA2. These reports suggest that BEL inhibits the magnesium-dependent, cytosolic isoform of a lipid phosphate phosphatase, PAP-1, thereby perturbing cellular lipid homeostasis (by inhibiting the formation of DAG from phosphatidate) and promoting apoptosis in prolonged cell culture (66, 67). Indeed, we have unpublished observations that concentrations of BEL at or exceeding 30 μM are toxic to SHHF cardiomyocytes after 10 h, which is consistent with observations published by these researchers. However, investigation by Gross et al. (68) showed that BEL neither diminishes whole cell lipid phosphate phosphatase activity at concentrations up to 100 μM, nor the activities of either PAP-1 or its membrane-bound relative, PAP-2, at concentrations up to 200 μM in purified subcellular fractions. In our study, we used a concentration of BEL (10 μM) below that which was previously reported to promote apoptosis or attenuate PAP-1 activity (25 μM) (66, 67). The role of PAP-1 as a phosphomonoesterase is unlikely to influence the remodeling of CL's acyl chains; furthermore, the concentration of BEL used herein was not toxic to myocytes after 24 h of incubation. Though we cannot entirely discount the possibility that BEL is affecting the activity of PAP-1 in our cell culture, we do not believe it seriously confounds the interpretation of our results.

In closing, we have used a novel cell culture method to generate data suggesting a necessary but partial role of iPLA2γ in CL remodeling in the SHHF rat heart. Further, 18:2 incorporation into (18:2)4CL is decreased largely in HF and may decrease slightly during nonpathological aging, CL is remodeled singly with respect to its acyl moieties, and iPLA2-dependent CL remodeling accounts for a greater percentage of total CL remodeling in HF versus nonHF after 10 h of observation. To the best of our knowledge, the current body of literature suggests that nascent CL may be remodeled to (18:2)4CL by a number of interacting deacylation-reacylation enzyme pairs, and that they all proceed through the intermediate MLCL. Future research examining the specific role of iPLA2γ and the path of 18:2 through the cell are necessary if we are to fully understand the remodeling of this unique phospholipid.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ALCAT

- acylCoA-lysocardiolipin acyltransferase

- AWTd

- left ventricular anterior wall thickness in diastole

- BEL

- bromoenol lactone

- 13C-18:2

- carbon stable isotope linoleic acid

- CDP-DAG

- cytidinediphosphate-diacylglycerol

- CL

- cardiolipin

- CLS

- CL synthase

- EF

- ejection fraction

- FBN

- Fisher Brown Norway

- FS

- fractional shortening

- HF

- heart failure

- IMM

- inner mitochodrial membrane

- iPLA2

- calcium-independent phospholipase A2

- LV

- left ventrical

- LVIDd

- left ventrical internal diameter in diastole

- LVIDs

- left ventricular internal diameter in systole

- MLCL

- monolysoCL

- MLCL-AT

- MLCL-acyltransferase

- PG

- phosphatidylglycerol

- PWTd

- left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole

- SHHF

- Spontaneously Hypertensive HF

This work was supported by a research grants from the Barth Syndrome Foundation (G.C.S.) and American Heart Association (GIA 0755763Z, to R.L.M.), as well as a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association Pacific Mountain Affiliate (A.J.C.). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the American Heart Association.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mileykovskaya E., Zhang M., Dowhan W. 2005. Cardiolipin in energy transducing membranes. Biochemistry. 70: 154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatch G. M. 2004. Cell biology of cardiac mitochondrial phospholipids. Biochem. Cell Biol. 82: 99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Q., Liu J., Lu B., Feingold K. R., Shi Y., Lee R. M., Hatch G. M. 2007. Phospholipid scramblase-3 regulates cardiolipin de novo biosynthesis and its resynthesis in growing HeLa cells. Biochem. J. 401: 103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hovius R., Thijssen J., van der Linden P., Nicolay K., de Kruijff B. 1993. Phospholipid asymmetry of the outer membrane of rat liver mitochondria. Evidence for the presence of cardiolipin on the outside of the outer membrane. FEBS Lett. 330: 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musatov A. 2006. Contribution of peroxidized cardiolipin to inactivation of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 41: 238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chicco A. J., Sparagna G. C. 2007. Role of cardiolipin alterations in mitochondrial dysfunction and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292: C33–C44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang M., Mileykovskaya E., Dowhan W. 2002. Gluing the respiratory chain together. Cardiolipin is required for supercomplex formation in the inner mitochondrial membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 43553–43556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paradies G., Petrosillo G., Pistolese M., Di Venosa N., Serena D., Ruggiero F. M. 1999. Lipid peroxidation and alterations to oxidative metabolism in mitochondria isolated from rat heart subjected to ischemia and reperfusion. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 27: 42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sedlak E., Robinson N. C. 1999. Phospholipase A2 digestion of cardiolipin bound to bovine cytochrome c oxidase alters both activity and quaternary structure. Biochemistry. 38: 14966–14972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haines T. H., Dencher N. A. 2002. Cardiolipin: a proton trap for oxidative phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 528: 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown L. R., Wuthrich K. 1977. NMR and ESR studies of the interactions of cytochrome c with mixed cardiolipin-phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 468: 389–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrosillo G., Ruggiero F. M., Paradies G. 2003. Role of reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin in the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria. FASEB J. 17: 2202–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ardail D., Lerme F., Louisot P. 1992. Phospholipid import into mitochondria: possible regulation mediated through lipid polymorphism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 186: 1384–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eilers M., Endo T., Schatz G. 1989. Adriamycin, a drug interacting with acidic phospholipids, blocks import of precursor proteins by isolated yeast mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 264: 2945–2950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mannella C. A. 2006. Structure and dynamics of the mitochondrial inner membrane cristae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1763: 542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sparagna G. C., Chicco A. J., Murphy R. C., Bristow M. R., Johnson C. A., Rees M. L., Maxey M. L., McCune S. A., Moore R. L. 2007. Loss of cardiac tetralinoleoyl cardiolipin in human and experimental heart failure. J. Lipid Res. 48: 1559–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlame M., Kelley R. I., Feigenbaum A., Towbin J. A., Heerdt P. M., Schieble T., Wanders R. J. A., DiMauro S., Blanck T. J. J. 2006. Phospholipid abnormalities in children with Barth syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 42: 1994–1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sparagna G. C., Lesnefsky E. J. 2008. Cardiolipin remodeling in the heart. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauff K. D., Hatch G. M. 2006. Cardiolipin metabolism and Barth syndrome. Prog. Lipid Res. 45: 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlame M., Ren M. 2006. Barth syndrome, a human disorder of cardiolipin metabolism. FEBS Lett. 580: 5450–5455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barth P. G., Valianpour F., Bowen V. M., Lam J., Duran M., Vaz F. M., Wanders R. J. 2004. X-linked cardioskeletal myopathy and neutropenia (Barth syndrome): an update. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 126A: 349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vreken P., Valianpour F., Nijtmans L. G., Grivell L. A., Plecko B., Wanders R. J. A., Barth P. G. 2000. Defective remodeling of cardiolipin and phosphatidylglycerol in Barth syndrome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 279: 378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heerdt P. M., Schlame M., Jehle R., Barbone A., Burkhoff D., Blanck T. J. J. 2002. Disease-specific remodeling of cardiac mitochondria after a left ventricular assist device. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 73: 1216–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasa Y., Sakamoto Y., Sanbe A., Sasaki H., Yamaguchi F., Takeo S. 1997. Changes in fatty acid compositions of myocardial lipids in rats with heart failure following myocardial infarction. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 176: 179–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han X., Yang J., Yang K., Zhongdan Z., Abendschein D. R., Gross R. W. 2007. Alterations in myocardial cardiolipin content and composition occur at the very earliest stages of diabetes: a shotgun lipidomics study. Biochemistry. 46: 6417–6428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatch G. M. 1994. Cardiolipin biosynthesis in the isolated heart. Biochem. J. 297: 201–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatch G. M., McClarty G. 1996. Regulation of cardiolipin biosynthesis in H9c2 cardiac myoblasts by cytidine 5′-triphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 25810–25816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hostetler K. Y., Van Den Bosch H., Van Deenen L. L. M. 1972. The mechanism of cardiolipin biosynthesis in liver mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 260: 507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlame M., Hostetler K. Y. 1997. Cardiolipin synthase from mammalian mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1348: 207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hatch G. M. 1998. Cardiolipin: biosynthesis, remodeling and trafficking in the heart and mammalian cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 1: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatch G. M. 1996. Regulation of cardiolipin biosynthesis in the heart. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 159: 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Y., Malhotra A., Ren M., Schlame M. 2006. The enzymatic function of tafazzin. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 39217–39224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor W. A., Hatch G. M. 2003. Purification and characterization of monolysocardiolipin acyltransferase from pig liver mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 12716–12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao J., Liu Y., Lockwood J., Burn P., Shi Y. 2004. A novel cardiolipin-remodeling pathway revealed by a gene encoding an endoplasmic reticulum-associated acyl-CoA:lysocardiolipin acyltransferase (ALCAT-1) in mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 31727–31734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mancuso D. J., Sims H. F., Han X., Jenkins C. M., Guan S. P., Yang K., Moon S. H., Pietka T., Abumrad N. A., Schlesinger P. H., et al. 2007. Genetic ablation of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 gamma leads to alterations in mitochondrial lipid metabolism and function resulting in a deficient mitochondrial bioenergetic phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 34611–34622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malhotra A., Edelman-Novemsky I., Xu Y., Plesken H., Ma J., Schlame M., Ren M. 2009. Role of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 in the pathogenesis of Barth syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106: 2337–2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCune S. A., Park S., Radin M. J., Jurin J. J. 1995. The SHHF/Mcc-facp: a genetic model of congestive heart failure. In Mechanisms of Heart Failure Singal P. K., Dixon I. M. C., Kluwer M. A., Dhalla N. S., Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston: 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haas G. J., McCune S. A., Brown D. M., Cody R. J. 1995. Echocardiographic characterization of left ventricular adaptation in a genetically determined heart failure rat model. Am. Heart J. 130: 806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomez A. M., Valdiva H. H., Cheng H., Lederer M. R., Santana L. F., Cannell M. B., McCune S. A., Altschuld R. A., Lederer W. J. 1997. Defective excitation-contraction coupling in experimental cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Science. 276: 800–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y. M., Steffes M., Donnelly T., Liu C., Fuh H., Basgen J., Bucala R., Vlassara H. 1996. Prevention of cardiovascular and renal pathology of aging by the advanced glycation inhibitor aminoguanidine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93: 3902–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sample J., Cleland J. G., Seymour A. M. 2006. Metabolic remodeling in the aging heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 40: 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lipman R. D., Chrisp C. E., Hazzard D. G., Bronson R. T. 1996. Pathologic characterization of Brown Norway, Brown Norway x Fischer 344, and Fischer 344 x Brown Norway rats with relation to age. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 51: B54–B59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chicco A. J., McCune S. A., Emter C. A., Sparagna G. C., Rees M. L., Bolden D. A., Marshall K. D., Murphy R. C., Moore R. L. 2008. Low-intensity exercise training delays heart failure and improves survival in female spontaneously hypertensive heart failure rats. Hypertension. 51: 1096–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emter C. A., McCune S. A., Sparagna G. C., Radin M. J., Moore R. L. 2005. Low-intensity exercise training delays onset of decompensated heart failure in spontaneously hypertensive heart failure rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 289: H2030–H2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheung J. Y., Thompson I. G., Bonventre J. V. 1982. Effects of extracellular calcium removal and anoxia on isolated rat myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 243: C184–C190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sparagna G. C., Johnson C. A., McCune S. A., Moore R. L., Murphy R. C. 2005. Quantitation of cardiolipin molecular species in spontaneously hypertensive heart failure rats using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Lipid Res. 46: 1196–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heyen J. R. R., Blasi E. R., Nikula K., Rocha R., Daust H. A., Frierdich G., Van Vleet J. F., De Ciechi P., McMahon E. G., Rudolph A. E. 2002. Structural, functional, and molecular characterization of the SHHF model of heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 283: H1775–H1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hacker T. A., McKiernan S. H., Douglas P. S., Wanagat J., Aiken J. M. 2006. Age-related changes in cardiac structure and function in Fischer 344 X Brown Norway hybrid rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 290: H304–H311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schlame M., Rustow B., Kunze D., Rabe H., Reichmann G. 1986. Phosphatidylglycerol of rat lung. Intracellular sites of formation de novo and acyl species pattern in mitochondria, microsomes and surfactant. Biochem. J. 240: 247–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Houtkooper R. H., Akbari H., van Lenthe H., Kulik W., Wanders R. J. A., Frentzen M., Vaz F. M. 2006. Identification and characterization of human cardiolipin synthase. FEBS Lett. 580: 3059–3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ostrander D. B., Sparagna G. C., Amoscato A. A., McMillin J. B., Dowhan W. 2001. Decreased cardiolipin synthesis corresponds with cytochrome c release in palmitate-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 38061–38067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlame M., Rustow B. 1990. Lysocardiolipin formation and reacylation in isolated rat liver mitochondria. Biochem. J. 272: 589–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schlame M., Towbin J. A., Heerdt P. M., Jehle R., Dimauro S., Blanck T. J. J. 2002. Deficiency of tetralinoleoyl-cardiolipin in Barth syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 51: 634–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malhotra A., Xu Y., Ren M., Schlame M. 2009. Formation of molecular species of mitochondrial cardiolipin. 1. A novel transacylation mechanism to shuttle fatty acids between sn-1 and sn-2 positions of multiple phospholipid species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1791: 314–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schlame M. 2009. Formation of molecular species of mitochondria cardiolipin: 2. A mathematical model of pattern formation by phospholipid transacylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1791: 321–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saini-Chohan H. K., Holmes M. G., Chicco A. J., Taylor W. A., Moore R. L., McCune S. A., Hickson-Bick D. L., Hatch G. M., Sparagna G. C. 2009. Cardiolipin biosynthesis and remodeling enzymes are altered during the development of heart failure. J. Lipid Res. 50: 1600–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee H-J., Mayette J., Rapoport S. I., Bazinet R. P. 2006. Selective remodeling of cardiolipin fatty acids in the aged rat heart. Lipids Health Dis. 5: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams S. D., Gottlieb R. A. 2002. Inhibition of mitochondrial calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) attenuates mitochondrial phospholipid loss and is cardioprotective. Biochem. J. 362: 23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seleznev K., Zhao C., Zhang X. H., Song K., Ma Z. A. 2006. Calcium-independent phospholipase A2 localizes in and protects mitochondria during apoptotic induction by staurosporine. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 22275–22288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clarke S. D. 2000. Polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of gene transcription: a mechanism to improve energy balance and insulin resistance. Br. J. Nutr. 83: S59–S66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Forman B. M., Chen J., Evans R. M. 1997. Hypolipidemic drugs, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and eicosanoids are ligands for peroxisome proliferators-activated receptors alpha and delta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94: 4312–4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sampath H., Ntambi J. M. 2005. Polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of genes of lipid metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 25: 317–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Balsinde J., Dennis E. A. 1996. Distinct roles in signal transduction for each of the phospholipase A2 enzymes present in P388D1 macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 6758–6765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hazen S. L., Zupan L. A., Weiss R. H., Getman D. P., Gross R. W. 1991. Suicide inhibition of canine myocardial cytosolic calcium-independent phospholipase A2. Mechanism-based discrimination between calcium-dependent and –independent phospholipases A2. J. Biol. Chem. 266: 7227–7232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Balsinde J., Balboa M. A., Insel P. A., Dennis E. A. 1999. Regulation and inhibition of phospholipase A2. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 39: 178–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Balsinde J., Dennis E. A. 1996. Bromoenol lactone inhibits magnesium-dependent phosphatidate phosphohydrolase and blocks triacylglycerol biosynthesis in mouse P388D1 macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 31937–31941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fuentes L., Perez R., Nieto M. L., Balsinde J., Balboa M. A. 2003. Bromoenol lactone promotes cell death by a mechanism involving phosphatidate phosphohydrolase-1 rather than calcium-independent phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 44683–44690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jenkins C. M., Dianlin H., Mancuso D. J., Gross R. W. 2002. Identification of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) β, and not iPLA2γ, as the mediator of arginine vasopressin-induced arachidonic acid release in A-10 smooth muscle cells: enantioselective mechanism-based discrimination of mammalian iPLA2s. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 32807–32814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]