Abstract

c-Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) is a signaling molecule that is activated by proinflammatory signals, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and other environmental stressors. Although JNK has diverse effects on immunological responses and insulin resistance in peripheral tissues, a functional role for JNK in feeding regulation has not been established. In this study, we show that central inhibition of JNK activity potentiates the stimulatory effects of glucocorticoids on food intake and that this effect is abolished in mice whose agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons are degenerated. JNK1-deficient mice feed more upon central administration of glucocorticoids, and glucocorticoid receptor nuclear immunoreactivity is enhanced in the AgRP neurons. JNK inhibition in hypothalamic explants stimulates Agrp expression, and JNK1-deficient mice exhibit increased Agrp expression, heightened hyperphagia, and weight gain during refeeding. Our study shows that JNK1 is a novel regulator of feeding by antagonizing glucocorticoid function in AgRP neurons. Paradoxically, JNK1 mutant mice feed less and lose more weight upon central administration of insulin, suggesting that JNK1 antagonizes insulin function in the brain. Thus, JNK may integrate diverse metabolic signals and differentially regulate feeding under distinct physiological conditions.

c-Jun-N-terminal kinase 1 regulates feeding by antagonizing functions of glucocorticoids and insulin in hypothalamic neurons.

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are now considered chronic inflammatory conditions that involve regulatory machinery of the immune system. It is generally accepted that conditions associated with obesity such as increased fatty acids, microhypoxia, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and cytokines activate proinflammatory responses in peripheral insulin target tissues by activating the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and inhibitor of nuclear factor κB kinase (IKK)/nuclear factorκB pathways, which in turn down-regulate insulin signaling (1). In contrast, the central role of inflammatory pathways in the regulation of energy homeostasis is not well understood. Previous studies have shown that many proinflammatory cytokines inhibit feeding when administered centrally (2,3). Injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a bacterial endotoxin that stimulates synthesis and release of multiple cytokines, also causes anorexia by acting in the central nervous system (CNS) (4,5,6,7). Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that IL-1β exerts its anorexigenic effect by acting on proopiomelanocortin (Pomc) and agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons (4,6,7), key hypothalamic neurons that promote negative and positive energy balance, respectively (8). In contrast to the anorexigenic effect of proinflammatory molecules, antiinflammatory signals, such as glucocorticoids, are known to stimulate feeding. Corticosterone administration to corticosterone-deficient mice stimulates food intake (9,10,11). In addition, adrenalectomy reverses hyperphagia in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice (12). In humans, hypercortisolism, as seen in Cushing’s syndrome or by exogenous administration of glucocorticoids to treat inflammatory diseases, causes obesity (13). More recently, several studies found that exposure to high-fat diet activates IKK-β and nuclear factor-κB signaling and ER stress in the brain, causing hypothalamic leptin resistance and increased feeding (14,15,16). Taken together, the above studies suggest that activation of central inflammatory pathways in response to different physiological conditions could have diverse effects on energy balance. Elucidating the functional interactions of proinflammatory and antiinflammatory pathways, and their neuronal targets will help us understand how these pathways are integrated to affect energy homeostasis.

JNK is a serine kinase that is activated by environmental stressors and ER stress and by multiple metabolic stimuli, such as cytokines, glucocorticoids, and free fatty acids (17,18,19). Many of these signals are dynamically regulated in various nutritional states and have been shown to act on hypothalamic neurons to affect feeding. There are three isoforms of JNK, and among them, JNK1 is ubiquitously expressed. However, mice deficient for JNK1, but not other JNK isoforms, are resistant to diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance (20,21). Importantly, a recent study by Solinas et al. (22) shows that JNK1 in hematopoietically derived cells contributes to diet-induced inflammation and insulin resistance without affecting obesity, suggesting that JNK1 acts in other tissues to regulate energy homeostasis. Interestingly, in vitro biochemical studies have shown that JNK1 directly phosphorylates glucocorticoid receptor (GR) on serine residues and inhibits its function by affecting protein stability, nuclear translocation, sumoylation, and transcriptional activity (23,24,25,26). Thus, JNK, a proinflammatory signaling component, could be involved in feeding regulation by modulating the activities of antiinflammatory glucocorticoid signaling in the brain. In this study, we show that JNK1 exerts a negative role on energy balance by antagonizing glucocorticoid signaling on hypothalamic AgRP neurons. We propose a model to address the distinct roles of JNK1 in feeding regulation under specific physiological conditions.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The generation of Tg.AgRP-Cre; Gt(Rosa)26Sortm1Sor (R26R-lacZ) was described previously (27), and these mice have been validated by multiple studies (10,15,27,28,29,30,31). As described before (27), about 20–30% of Tg.AgRP-Cre/R26R-lacZ mice exhibit early embryonic expression of Cre as determined by widespread X-gal staining in somatic tissues using an ear biopsy procedure, and these mice were excluded from our study. Mice with deletion of mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam) gene specifically in the AgRP neurons (AgRP-Tfam mutants) have previously been developed and characterized in detail (10). In these mice, about 85% of AgRP neurons undergo gradual degeneration by 7 months of age. Eight-month-old female AgRP-Tfam mutants and littermate controls were used in this study. To generate AgRP-Tfam mutant and control mice, males homozygous for the floxed Tfam allele and heterozygous for the AgRP-Cre transgene were mated to females that were homozygous for the floxed Tfam allele. All mice were genotyped as previously described (10). Mice that are heterozygous for a null allele of mapk8 (mapk8+/−) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The mice obtained were on a C57BL/6 background and have been maintained on the same background. No phenotypic difference was observed in wild-type (Mapk8+/+) and heterozygous (Mapk8+/−) animals in experiments described in the study, so they were pooled together as controls. For all experiments, age- and sex-matched controls and mutants (Mapk8−/−) were used. Mice expressing humanized renilla green fluorescent protein (hrGFP) under the control of the mouse Npy promoter were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory [B6.FVB-Tg(NPY-hrGFP)1Lowl/J], and the specificity of GFP expression has been validated (32). All mice were housed in the University of California, San Francisco, mouse barrier facility in a room with 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle (0700–1900 h light). All experiments were carried out under a protocol approved by the University of California, San Francisco, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Refeeding studies

For feeding studies, mice were singly housed for at least 1 wk before food intake measurements. To measure compensatory refeeding, food was removed right before the onset of the dark cycle, and mice were fasted for 36 h with free access to water, after which time food was returned. Food intake and body weight were measured 2, 4, 6, 24, 48, and 72 h and 1 wk during refeeding.

Hypothalamic explant culture

Hypothalamic slice cultures were performed as previously described with minor modifications (33,34,35). Adult control mice were killed, and fresh coronal sections (500 μm) were cut using a brain matrix on ice in dissection medium [50% DMEM, 50% Hanks’ balanced salt solution, 25 mm HEPES buffer, 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), and 100 μg/ml penicillin-streptomycin]. Each coronal section through the hypothalamus was cut down the midline along the third ventricle to yield two identical halves. Each half was placed in Millicell CM 0.4-μm culture plate inserts and cultured at 37 C in culture medium (50% DMEM, 25% Hanks’ balanced salt solution, 25% heat-inactivated horse serum, 2 mm glutamine, and 100 μg/ml penicillin-streptomycin) in a 5% CO2 incubator. After overnight culture, one half of the slice was treated with a specific drug, and the other half was subjected to treatment with its corresponding vehicle. Drug concentrations are 50 μm SP600125 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in medium with 1% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and 10 μm RU-38486 (Sigma) in medium with 0.1% ethanol. RNA was extracted from the explants after 30 h treatment, and semiquantitative PCR was carried out. Gene expression was compared between the two halves from the same brain.

Intracerebroventricular (icv) injection

For implantation of the guide cannula, mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine (Ketaset; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, Iowa) and 5 mg/kg xylazine (Akorn Inc., Lincolnshire, IL) with 0.5% isoflurane used as needed to maintain a surgical plane of anesthesia. Custom 5.7-mm guide cannulas (Plastics One, Wallingford, CT) were implanted using a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) into the third ventricle (x, 0.0; y, bregma −2.0; z, −5.7). Buprenorphine (Buprenex; Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare Ltd., Slough, UK) 0.1 mg/kg was used immediately after surgery and as needed. Mice were singly housed and allowed 1 wk to recover before checking placement with drinking response to angiotensin II (Sigma; 100 μg/ml, 1 μl per mouse). Cannula placement was also verified by postmortem histochemical examination. For icv injection, a custom 5.9-mm injector (Plastics One) was used. Mice were allowed free movement within a limited area while 1 μl was infused at a rate of 10 nl/sec using a micropump (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Mice were injected with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF), consisting of 150 mm NaCl, 3.0 mm KCl, 1.4 mm CaCl2, 0.8 mm MgCl2, 1 mm NaH2PO4 (pH 7.4), once daily for 3 d, and 1 or 5 mU insulin (Humalin R; Hospira, Inc., Morgan Hill, CA) or 250 ng dexamethasone (water soluble; Sigma) on the fourth day. For SP600125 treatment, SP600125 (264 ng/mouse in aCSF with 33% DMSO) and its corresponding vehicle (33% DMSO in aCSF) was injected with or without dexamethasone. All injections were done at 1800–1900 h, and 24-h food intake was measured after injection and compared with average food intake during the corresponding period of vehicle treatment.

LPS injection, leptin sensitivity test, and ip injection of corticosterone

For LPS injection, each mouse was injected ip with saline for 3 d, once daily (1000 h) and then injected with 20 or 50 μg/kg LPS (Sigma) on the fourth day, and 24-h food intake was measured after injection and compared with average food intake during saline treatment. For leptin sensitivity measurement, each mouse was injected ip with saline for 3 d, twice daily (0830 and 1830 h) and then injected with leptin (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) twice at a dose of 1.5, 2, or 3 mg/kg on the fourth day. Food intake was calculated as the average of the 3-d saline treatment and compared with the 24-h leptin treatment period. For ip injection of corticosterone, control and mutant animals were injected ip once daily for 3 d with vehicle (4, 8, or 16% ethanol in saline) and one of three different doses of 2, 4, or 8 mg/kg corticosterone on the fourth day. Daily food intake was measured over a 4-h period (1000–1400 h).

Hormonal measurements

Blood was collected from fed, fasted (36 h), and refed mice via mandibular vein puncture. Plasma insulin and leptin were measured with an insulin ELISA kit (Alpco Inc., Salem, NH) and a leptin ELISA kit (Crystal Chem, Downer’s Grove, IL) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. To measure blood corticosterone levels, fed and 36-h-fasted, singly housed mice were acclimatized to the procedure room for several hours (1000–1200 h) and then quickly killed and decapitated. Truck blood was collected, and plasma corticosterone levels were measured using a corticosterone EIA kit (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI).

mRNA expression analysis using real-time RT-PCR

Measurements of mRNA levels were carried out by quantitative RT-PCR on RNA extracted from dissected hypothalamic tissue. Total RNA from each hypothalamus was purified using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and an RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and quantified by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). One microgram of each total RNA sample was reverse transcribed and then PCR amplified using the 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and SYBR green to measure relative cDNA levels. β-Actin was used as the internal control to normalize expression. Agrp, Pomc, Npy, lepr, and β-actin primers were the same as previously published (36). Later experiments were performed using commercial TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems) for Agrp, Npy, Pomc, Crh, NR3C, and β-actin according to the manufacturer’s protocol and measured as above. Some assays were performed using both SYBR green and TaqMan, and no difference was detected between the two methods.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Mice were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed, placed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 C overnight, and then transferred to 30% sucrose in PBS for 24 h at 4 C. Then 10-μm frozen sections were prepared and mounted on Superfrost/Plus slides. X-gal staining was carried out as previously described (10,27,37). Bright-field images were captured using a Zeiss Axioscope imaging system equipped with an AxioCam color digital camera. For immunofluorescence, sections were washed in PBS and unmasked as necessary using either 10 min 0.3% glycine, 10 min 0.3% SDS, or 30 min boiling 0.1% sodium citrate solution and then stained using methods described previously (10,37). Polyclonal anti-GR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; 1:500 dilution), NeuroTrace red fluorescent Nissl stain (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; 1:100 dilution), monoclonal anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (Sigma; 1:500 dilution), polyclonal anti-neuropeptide Y (anti-NPY) (Peninsula Laboratories, LLC, Sa Carlos, CA; 1:500 dilution), and polyclonal anti-p-c-Jun (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:100 dilution) were used. Goat antirabbit Alexa488, goat antirabbit Alexa555, and goat antimouse Alexa488 (Molecular Probes) were used for secondary antibody detection. Sections were mounted using Vectashield with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), Hard Mount (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Fluorescence images were captured using a Zeiss Axioscope2 imaging system equipped with an AxioCam black and white digital camera.

Cell counting

Images to be counted were captured as above using the same exposure time for each and no enhancement. Images were first examined for position and sections within the range bregma −1.90 to −2.30 were included in counting. Images were then modified using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for background subtraction. Sections were then blinded, an intensity threshold was set, and cells within the arcuate nucleus were counted independently by two different people.

Statistics

Analysis was performed by two-tailed Student’s t test, and groups being compared are described in the figure legends. Values are presented as mean ± sem. For feeding studies that involved treating the same animals with vehicle and various doses of experimental reagents, repeated-measures ANOVA was employed using SPSS version 14.0 software. Multiple pairwise comparisons were computed using estimated marginal means with least significant different adjustment.

Results

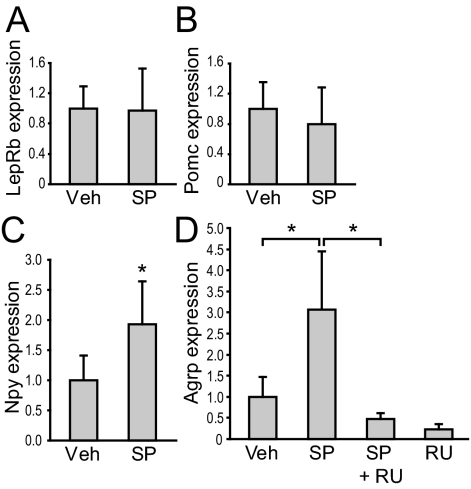

Inhibition of JNK activity in hypothalamic explants stimulates Agrp and Npy expression

To explore the role of JNK in feeding regulation, we first examined whether inhibition of JNK activity in hypothalamic neurons affects expression of leptin receptor (lepr) long form, Pomc, Npy, or Agrp. Coronal hypothalamic slices were cut along the third ventricle to yield two identical halves, which were then cultured. One half of the slice was treated with an SP600125, a JNK inhibitor at a dose previously shown to be effective (38), and the other half was treated with its corresponding vehicle. RNA was extracted from the explants after 30 h treatment and semiquantitative PCR was carried out to measure gene expression. Gene expression from two halves of the same brain was compared. Although SP600125 treatment did not affect the expression of leptin receptor long form or Pomc (Fig. 1, A and B), it caused a significant increase in Npy and Agrp mRNA expression compared with vehicle treatment (Fig. 1, C and D).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of JNK activity in hypothalamic explants leads to an increase in Agrp expression that can be blocked by GR inhibition. Coronal hypothalamic slices (500 μm) from wild-type mice were dissected into two identical halves and cultured in vitro. One half was treated with JNK inhibitor SP600125 (SP) (50 μm, n = 8) and the other with vehicle (Veh). RNA was extracted after 30 h, and Lepr long form (A), Pomc (B), Npy (C), and Agrp (D) expression was analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR using β-actin as an internal control. In a separate experiment, we examined whether inhibitory effect of JNK on Agrp expression could be antagonized by GR inhibition. One half of the slice was treated with SP, and the other was treated with SP and a GR inhibitor, RU-38486 (10 μm) (SP+RU, n = 5). RU by itself (n = 3) was compared with vehicle (D). Statistics were done using Student’s paired t test comparing the two different treatments of identical halves. *, P < 0.05. Agrp expression in different vehicle and SP groups was indistinguishable, so data were pooled for graph presentation but not for statistical comparison.

Because JNK is known to phosphorylate GR in vitro, and glucocorticoids have been shown to stimulate Agrp and Npy expression (11,33,39), we examined whether JNK would play a role in mediating glucocorticoids’ effect on Agrp expression. Treatment with a GR inhibitor, RU-38486, abolished the ability of SP600125 to stimulate Agrp expression (Fig. 1D). The apparent effect of JNK inhibition on Agrp expression in the absence of exogenous glucocorticoids is likely due to the presence of glucocorticoids in the serum that was used in the culture (40). Taken together, these results indicate that JNK and glucocorticoids have opposing effects on Agrp expression in hypothalamic cells and that the effect of JNK inhibition on Agrp expression is GR dependent.

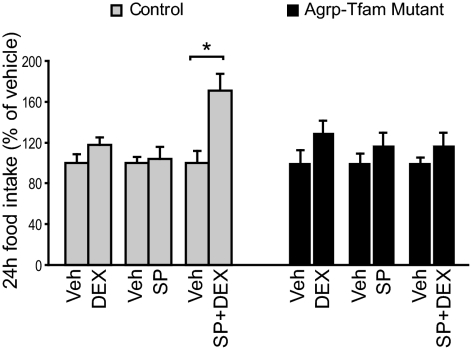

Central inhibition of JNK activity potentiates glucocorticoids’ orexigenic effects in controls but not in mutant mice with degenerated AgRP neurons

Our above results suggest that JNK inhibits Agrp and Npy expression via antagonizing the effects of glucocorticoids. We next investigated whether JNK would alter the effects of glucocorticoids on food intake. It is well known that Agrp and Npy are coexpressed from the same neurons within the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (41). Thus, we employed a transgenic mouse model previously developed in which 85% of AgRP neurons gradually degenerated due to deletion of mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam) gene from the AgRP neurons (10). Due to the progressive nature of AgRP neurodegeneration, AgRP-Tfam mutant mice have normal food intake and body weight on a regular diet (10). AgRP-Tfam mutant mice were generated by crossing a Tfam floxed allele with Tg.AgRPCre mice, in which Cre recombinase was specifically expressed in the AgRP neurons, as previously described (10). The specificity of the Tg.AgRPCre animals has been previously characterized and validated by a number of independent research groups (10,15,27,28,29,30,31). Guide cannulas were implanted into the third ventricle in control and AgRP-Tfam mutant mice. SP600125 (264 ng) or dexamethasone (250 ng), a synthetic glucocorticoid, was administered icv into the brain of control and weight-matched AgRP-Tfam mutant mice. This dose of icv dexamethasone has been shown to restore food intake in adrenalectomized leptin-deficient ob/ob mice but has no effect on wild-type mice (42,43). Although this dose of SP600125 or dexamethasone treatment alone did not affect feeding, combined treatment of SP600125 and dexamethasone significantly stimulated feeding in the control but not in AgRP-Tfam mutant animals (Fig. 2). This result strongly suggests that the effect of JNK on food intake is via modulation of glucocorticoid function in the AgRP neurons.

Figure 2.

Central inhibition of JNK activity potentiates glucocorticoids’ hyperphagic effect in controls but not in mutant mice lacking AgRP neurons. To measure the effect of central JNK inhibition in vivo, aCSF was injected icv via third ventricle cannula once daily for 3 d into control and weight-matched Tg.AgRPCre-Tfamflox/flox (AgRP-Tfam) mice. Then dexamethosone (DEX, 250 ng), SP600125 (SP, 264 ng), or SP+DEX was injected on the fourth day. Each treatment group had a corresponding vehicle (Veh) control. Food intake was measured over a 24-h period. n = 5–6. *, P < 0.05 between treatment and mean vehicle values, as determined by Student’s t test.

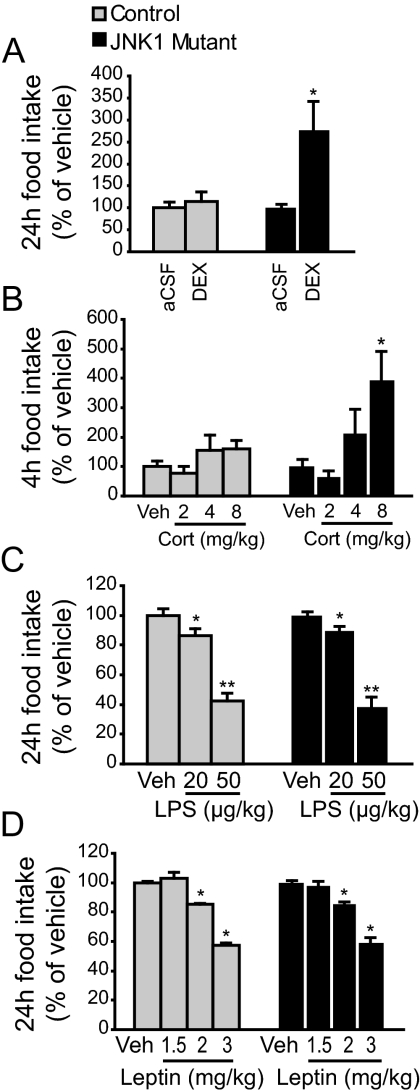

JNK1-deficient mice feed more in response to central administration of glucocorticoids

We next investigated whether glucocorticoids differentially affect feeding in mice that are deficient in JNK1. Consistent with results described previously (20), adult JNK1 mutant mice (Mapk8−/−) are slightly smaller and feed slightly less. However, feeding is comparable to the controls when normalized to body weight (supplemental Fig. 1, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). Guide cannulas were implanted into the third ventricle in control and JNK1 mutant mice. Vehicle or dexamethasone (250 ng/mouse) was icv injected, and 24-h food intake was measured. We found that dexamethasone injection did not affect food intake in controls but stimulated feeding more than 2-fold in JNK1 mutants (Fig. 3A). Intraperitoneal injection of corticosterone (8 mg/kg) similarly stimulated feeding in the mutants but not in the controls (Fig. 3B). This result further supports our notion that JNK1 acts centrally to inhibit glucocorticoids’ effect on food intake.

Figure 3.

JNK1 mutant mice feed more upon hypothalamic administration of glucocorticoids. A, Central glucocorticoid sensitivity was measured by once-daily icv (via third ventricle cannula) injection of aCSF for 3 d and dexamethasone (DEX, 250 ng) on the fourth. Food intake was measured over a 24-h period. n = 5–6. B, Mice were ip injected with vehicle once daily for 3 d, and one of three doses of corticosterone (Cort; 2, 4, or 8 mg/kg) on the fourth. Food intake was measured over a 4-h period. n = 7–8. C, LPS-induced anorexia was measured by once-daily ip injection of saline for 3 d and one of two doses of LPS (20 or 50 μg/kg) on the fourth. Food intake was measured over a 24-h period. n = 7–9. D, To measure leptin sensitivity, mice were ip injected with saline twice daily for 3 d and one of three doses of recombinant leptin (1.5, 2, or 3 mg/kg) on the fourth. Food intake was measured over a 24-h period after the first leptin injection. n = 7–8. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 between vehicle and treatment as determined by repeated-measures ANOVA. Multiple pairwise comparisons were computed using estimated marginal means with least significant different adjustment. Veh, Vehicle.

JNK1-deficient mice respond normally to the anorexigenic effects of proinflammatory cytokines or leptin

We next investigated whether JNK1 was required for the anorexigenic effect of LPS, which stimulates the synthesis and release of multiple cytokines. Control and JNK1 mutant mice were injected ip with saline or LPS (20 or 50 μg/kg), and food intake was measured 24 h after injection. We found that LPS inhibited food intake in a dose-dependent manner, and to the same degree in controls and mutants (Fig. 3C), suggesting that JNK1 signaling is not required for LPS-mediated anorexia.

Because leptin receptor belongs to the cytokine receptor family, we examined whether leptin sensitivity is altered in JNK1 mutant mice (44). Control and mutant animals were injected ip with saline or leptin (1.5, 2, or 3 mg/kg) twice daily, and daily food intake was measured. Leptin inhibited food intake in a dose-dependent manner, and to the same extent in controls and mutants (Fig. 3D), suggesting that leptin sensitivity is normal in the mutants.

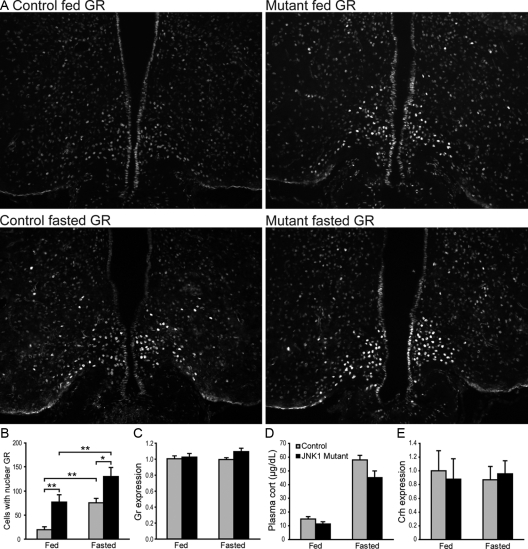

JNK1-deficient mice show enhanced nuclear GR immunoreactivity in the AgRP neurons

Upon glucocorticoid binding, GR translocates from the cytoplasm into the nucleus, where it acts as a transcription factor to regulate gene expression. Fasting is known to cause elevation of circulating corticosterone in mice, which we have confirmed (Fig. 4D). Consistent with increased glucocorticoid levels, we found that fasting induced a 3-fold increase in GR immunoreactivity in the medial-basal hypothalamus of the control animals compared with the fed state (Fig. 4, A and B). The GR immunoreactivity was nuclear, evident by their colocalization with DAPI, which marks nuclei. Furthermore, a nearly 2-fold increase of the GR-positive neurons was detected in the mutants compared with the controls (Fig. 4, A and B). No difference in GR gene (NR3C1) mRNA expression was detected (Fig. 4C), suggesting that increased nuclear GR signal is due to increased nuclear translocation of GR or its increase is confined to only a small subset of cells. In addition, no significant difference in circulating corticosterone levels or hypothalamic CRH (Crh) gene expression was detected in the mutants (Fig. 4, D and E). Together these results suggest that glucocorticoid production is normal in mutant animals.

Figure 4.

Nuclear GR immunoreactivity is enhanced in the hypothalamus of JNK1-deficient mice. A and B, Immunofluorescence analysis of GR-positive cells (A) in fed and 36-h-fasted controls and JNK1 mutants and its quantification (B). Hypothalamic sections were selected from Bregma −2.06 to −2.30. n = 10–16 sections from three mice per group. C, mRNA expression of GR gene (NR3C1) was measured by semiquantitative RT-PCR from fed (n = 5–6) and 36-h-fasted (n = 4–8) mice. β-Actin was used as an internal control. Expression was normalized to control fed value. D, Plasma corticosterone (cort) levels from fed and 36-h-fasted mice were measured by enzyme immunoassay. Control n = 8; mutant n = 6. E, mRNA expression of hypothalamic Crh was measured by semiquantitative RT-PCR from fed and 36-h-fasted mice. n = 5–6. β-Actin was used as an internal control. Expression was normalized to control fed value. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 as determined by Student’s t test.

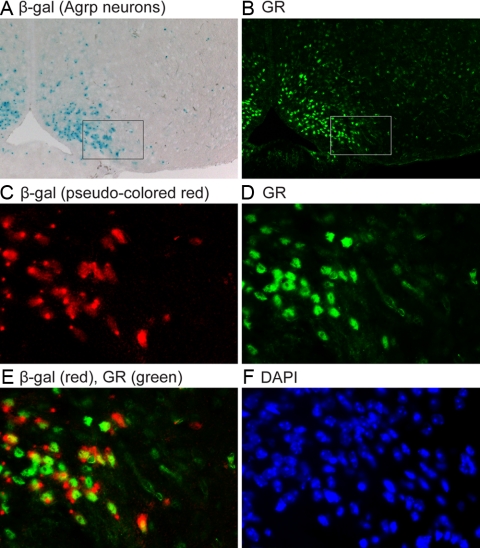

To verify the identity of these GR-positive neurons, we used the Tg.AgRPCre transgenic mice as described above and crossed them to a Rosa26 Cre reporter line that expresses the LacZ gene in a Cre-dependent manner. Thus, AgRP neurons could be identified by their expression of β-galactosidase, the LacZ gene product (Fig. 5). We found that about half of the AgRP neurons were positive for GR (409 of 853 AgRP neurons); likewise, a significant number of GR-positive neurons were AgRP neurons (409 of 919). Taken together, these data suggest that glucocorticoid function is enhanced in AgRP neurons of the mutant animals, and it is not due to increased circulating ligand levels. This result is consistent with our notion that JNK1 negatively regulates GR function in the AgRP neurons.

Figure 5.

Colocalization of GR immunoreactivity with AgRP neurons. A, Hypothalamic sections from 36-h fasted control mice containing Tg.AgRP-Cre and the Cre-reporter R26R-LacZ were stained with X-gal to identify AgRP neurons, as marked by expression of β-galactosidase (β-gal, blue staining in cell bodies with characteristic perinuclear dots). B, GR immunoreactivity in the same section as shown in A. C–E, The zoomed image of the boxed area in A was taken with the fluorescent microscope’s bright-field lamp to ensure colocalization and pseudo-colored to red (C). Fluorescent GR signal from the same field (D) and merged image (E) are shown. F, DAPI stain reveals nuclei of all cells in the same field. GR immunoreactivity was nuclear as evident by its colocalization with DAPI. The 15 sections (bregma −2.18 to −2.30) were from five mice.

To determine whether development of the hypothalamic feeding center was altered in JNK1 mutant mice, we examined the projection patterns of AgRP neurons in the control and mutant hypothalamus. Agrp is known to coexpress with Npy in neurons within the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, and neuronal projections from these neurons were revealed by immunofluorescent analysis using an NPY antibody. No gross difference in the projection patterns was detected (supplemental Fig. 2). We also showed that control and JNK1 mutant mice had a similar number of Nissl-positive cells (382 ± 14 per section in controls vs. 375 ± 10 in mutants) and glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive cells (97 ± 14 per section in controls, 106 ± 8 in mutants) within the arcuate nucleus, suggesting that the JNK1 mutants do not have gross alteration in number of neuronal and glial cell populations within the hypothalamic feeding center (supplemental Fig. 3).

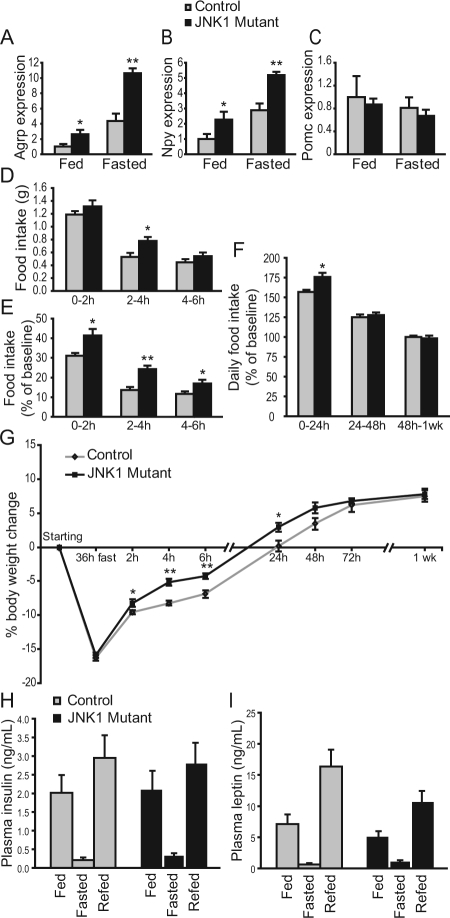

JNK1 mutant mice have increased Agrp and Npy expression, heightened hyperphagia, and weight gain during refeeding

We have previously shown that inhibition of JNK activity in hypothalamic explants led to a significant increase in Agrp and Npy expression (Fig. 1). We thus examined whether Agrp and Npy expression was also altered in JNK1 deficiency in vivo. mRNA expression of Agrp, Npy, and Pomc from hypothalamic tissues was examined by semiquantitative real-time RT-PCR. We found that Agrp and Npy expression was significantly elevated in the mutants compared with the controls but that Pomc expression was similar (Fig. 6, A–C).

Figure 6.

JNK1-deficient mice exhibit increased Agrp expression, heightened hyperphagia, and weight gain during refeeding. A–C, mRNA expression was analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR from hypothalamic tissues of 16- to 19-wk-old male mice that were fed or fasted for 36 h. β-Actin was used as an internal control. Expression was normalized to control fed value. Control n = 6; mutant n = 5. D–F, Mice were fasted for 36 h and then allowed free access to food. Food intake was measured during the refeeding period (D) and compared with the prefasted 24-h food intake of the same mouse (E and F). G, Body weight change of control and JNK1 mutant mice after fasting and during the refeeding period. Control n = 12; mutant n = 11. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 between controls and mutants as determined by Student’s t test (A–G). H and I, Plasma insulin and leptin levels were measured by ELISA under fed, 36 h fasting, and 6 h refed conditions. Insulin n = 15 each for control and mutant under fed and refed conditions; control n = 6, and mutant n = 9 under fasting condition. Leptin control n = 13–14, and mutant n = 15 under fed and refed conditions; control n = 7, and mutant n = 8 under fasting condition.

Because JNK1 mutant mice are hypersensitive to hypothalamic administration of glucocorticoids, we wished to determine whether mutant animals would show altered feeding under physiological conditions in which glucocorticoid levels are high. Fasting is one such condition where glucocorticoid levels are significantly elevated and adrenalectomy blunts the refeeding response (45). To this end, mice were fasted for 36 h and then allowed free access to food. Weight loss was similar in both genotypes during the fast (Fig. 6G), suggesting that energy expenditure was similar. Food intake during refeeding was measured and compared with prefasted food intake of the same mouse, so each mouse served as its own control. As expected, a hyperphagic response was observed in both genotypes during refeeding; however, mutants ate significantly more than the controls during refeeding, and this increased feeding persisted for 24 h (Fig. 6, D–F). Food intake in the mutants gradually reduced thereafter and returned to their prefasted levels within 48 h (Fig. 6F). Consistent with the increase in food intake, mutant mice regained their weight significantly faster than the controls, and the heightened weight gain persisted for almost 2 d refeeding (Fig. 6G). Examination of insulin and leptin levels revealed that they changed appropriately in controls and mutants after fasting and under different feeding conditions (Fig. 6, H and I). Blood glucose levels also changed appropriately in controls (115.3 ± 2.7 mg/dl fed, 65 ± 2.0 mg/dl 16 h fasted, 123 ± 6.9 mg/dl 2 h refed, mean ± sem) and in mutants (114.8 ± 5.3 mg/dl fed, 67 ± 2.6 mg/dl 16 h fasted, 148 ± 12.9 mg/dl 2 h refed). Thus, as predicted, JNK1 deficiency results in heightened hyperphagia and weight gain during refeeding and that this phenotype is specific to the refeeding period.

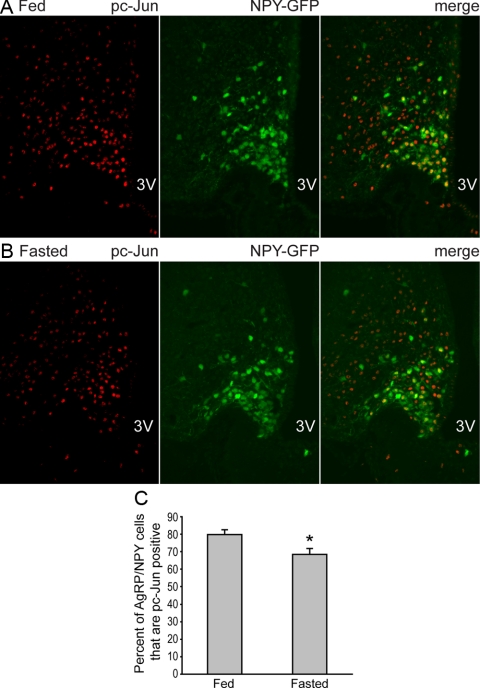

JNK activity is reduced during fasting

We next investigated whether JNK activity in the AgRP neurons could be modulated by fasting by examining phosphorylation of serine-73 at the N terminus of the c-Jun protein, a site that is predominantly phosphorylated by JNK (46). Because Agrp and Npy are coexpressed by the same neurons within the arcuate nucleus, we used transgenic mice in which hrGFP was specifically expressed in the AgRP/NPY neurons such that these neurons could be readily identified by GFP expression (32). Immunofluorescence analysis was performed to visualize phosphorylation of c-Jun in AgRP/NPY neurons from mice that were either fed or fasted for 25 h. The percentage of AgRP/NPY neurons that were positive for phospho-Ser73-c-Jun was moderately decreased in fasting compared with the fed condition, and this decrease was statistically significant (Fig. 7). The reduction of JNK activity during fasting is consistent with our notion that reduced JNK activity during fasting removes a negative tone on the GR, which in turn stimulates Agrp expression and sets the stage for hyperphagic refeeding.

Figure 7.

Phosphorylation of serine-73 at the c-Jun N-terminal domain is reduced in the AgRP/NPY neurons during fasting. A and B, Mice expressing NPY-GFP were either fed (A) or fasted for 25 h (B). Immunofluorescence analysis was performed on hypothalamic sections to detect phosphorylation of serine-73 (red, nuclear signal) at the c-Jun N terminus, a site that is predominantly phosphorylated by JNK (46). Direct GFP fluorescence (green, in both cytoplasm and nucleus) marks the AgRP/NPY neurons. C, Quantification of colocalized cells shows reduced phospho-c-Jun (pc-Jun) at serine-73 in the AgRP/NPY neurons in the fasted state. n = 10 sections from three fed mice, and n = 9 sections from three fasted mice. *, P < 0.05 between controls and mutants as determined by Student’s t test. 3V, Third ventricle.

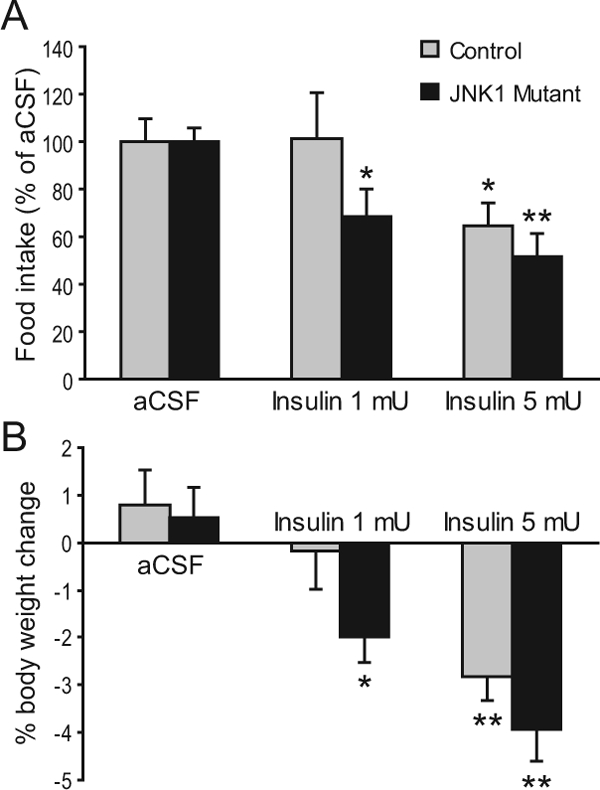

JNK1-deficient mice are hypersensitive to the anorexigenic effects of insulin

The above results suggest that JNK1 acts as a negative regulator of energy balance. However, this presents a paradox because JNK1-deficient mice are resistant to diet-induced obesity (20), suggesting that JNK1 acts as a positive regulator of energy balance. Because JNK1 is known to inhibit insulin signaling in peripheral tissues, we investigated whether JNK1 would inhibit insulin function in the brain. To this end, insulin was administered into the brain of control and JNK1 mutant mice via third ventricle cannula. A high dose of insulin (5 mU/mouse) caused a significant decrease in food intake and body weight in both controls and mutants, consistent with the anorexigenic effects of insulin. However, a low dose of insulin (1 mU/mouse) had no effect on food intake and body weight in the controls but caused a significant decrease in food intake and body weight in the mutants (Fig. 8). This result indicates that JNK1 acts in the brain to antagonize the effects of insulin on food intake, suggesting that central JNK1 deficiency could enhance the anorexigenic effects of insulin and prevent diet-induced obesity. This notion is consistent with the findings by De Souza and colleagues (47) that central inhibition of JNK activity enhances insulin signaling and decreases food intake in diet-induced obese rats.

Figure 8.

JNK1-deficient mice are hypersensitive to insulin’s anorexigenic effects. A and B, aCSF was injected icv once daily for 3 d, followed by insulin (1 or 5 mU) injection into control and JNK1 mutant mice via third ventricle cannula. Food intake (A) and body weight change (B) were measured over a 24-h period. n = 5–6. Food intake after insulin treatment was compared with value obtained during vehicle treatment, such that each mouse served as its own control. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 as determined by Student’s paired test.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the function of JNK1 in feeding regulation. We provide evidence that JNK1, a proinflammatory signaling molecule, plays a novel role in feeding regulation by acting on hypothalamic neurons. JNK1 exerts an inhibitory effect on glucocorticoid signaling in the AgRP neurons, thereby reducing Agrp expression and feeding. The lack of response of AgRP-Tfam mutant mice to central JNK inhibition suggests that AgRP neurons are essential mediators of JNK1 function. It should be noted that both AgRP and NPY functions in the arcuate nucleus are disrupted in the AgRP-Tfam mutant mice due to the coexpression of these two genes. So it is currently unclear whether JNK1 differentially regulates AgRP or Npy within the same neurons, although glucocorticoids have been shown to affect the expression of both genes (33,39). Both AgRP and NPY are potent orexigenic neuropeptides, and overexpression of AgRP leads to profound hyperphagia and obesity (48). Situated in the mediobasal hypothalamus and adjacent to the median eminence, a circumventricular organ, AgRP neurons are in constant communication with blood-borne metabolic and hormonal signals. We have previously shown that AgRP neurons mediate both leptin and insulin signaling (27,49). In addition, AgRP neurons have been shown to be direct targets of IL-1β (4). Thus, AgRP neurons are key neuronal targets to sense and integrate diverse metabolic, proinflammatory, and antiinflammatory signals. Our study shows that JNK, a canonical proinflammatory signaling molecule, functionally interacts with an antiinflammatory pathway in these neurons to regulate food intake.

The heightened hyperphagia and excess weight gain during refeeding observed in JNK1 deficiency is unique. The ability to regulate feeding in response to environmental and physiological challenges such as starvation is essential for survival. Compensatory refeeding is robustly regulated to ensure that shrunken fat stores can be quickly replenished. To date, a few mouse mutations have been identified with attenuated refeeding (10,37,50,51,52), whereas other models show normal refeeding despite being lean (53) or obese (54). The JNK1 mutant mouse, to our knowledge, represents a unique genetic model with heightened refeeding, indicating that JNK1 plays a unique role in regulating energy balance in times of energy deficit. The fasting-induced reduction of JNK-mediated phosphorylation in the AgRP/NPY neurons lends support to our notion that reduced JNK activity during fasting removes a negative tone on the GR, which in turn stimulates Agrp expression and set the stage for hyperphagic refeeding. Conversely, JNK activity has been shown to increase in the hypothalamus of diet-induced obese rodents (47). Thus, it is possible that hypothalamic JNK is regulated by hormones that reflect the abundance of the body’s energy stores, and future studies will be needed to identify these upstream regulators.

The effect of glucocorticoids on AgRP neuronal function is most evident during refeeding. Upon food deprivation, glucocorticoid levels are dramatically elevated, which is accompanied by a marked increase in Agrp expression and a hyperphagic response upon refeeding. Consequently, adrenalectomy or acute ablation of AgRP neurons leads to reduced refeeding (45,52). The stimulatory role of glucocorticoids on Agrp expression is well established. It has been shown that adrenalectomy or genetic corticosterone deficiency blunts Agrp expression, and corticosterone replacement rescues Agrp expression and stimulates food intake (9,10,11,39). It remains to be determined whether glucocorticoids regulate Agrp expression directly by the transcriptional activity of GR. A conserved glucocorticoid-responsive element is present immediately upstream of the AgRP regulatory region as revealed by sequence analysis using the UCSC Genome Browser version 187 TFBS Conserved feature, but the functional importance of this conserved glucocorticoid-responsive element is unknown. Alternatively, a recent study shows that glucocorticoids up-regulate Agrp and Npy gene expression in the arcuate nucleus through activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase signaling (33).

Our results suggest that JNK1 acts as a negative regulator of energy balance because JNK1 deficiency results in hyperphagia and excess weight gain upon refeeding. However, this presents a paradox because JNK1-deficient mice are also shown to be resistant to diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance (20), suggesting that JNK1 acts as a positive regulator of energy balance. A recent study by Solinas et al. (22) shows that JNK1 in hematopoietically derived cells contributes to diet-induced inflammation and insulin resistance without affecting obesity, suggesting that JNK1 acts in other tissues to regulate energy homeostasis. Our current study indicates that JNK1 acts in the brain to antagonize the effects of insulin on food intake, suggesting that central JNK1 deficiency could enhance anorexigenic effects by insulin and prevent diet-induced obesity. This notion is consistent with the findings by De Souza and colleagues (47) that central inhibition of JNK activity enhances insulin signaling and decreases food intake in diet-induced obese rats.

To reconcile the opposing effects of JNK1 deficiency on feeding, we propose a model where JNK1 regulates food intake by sensing and integrating glucocorticoid and insulin signaling in hypothalamic neurons. This dichotomy stems from the differential roles of JNK on CNS insulin and glucocorticoid signaling under different nutritional status. Under conditions of positive energy balance such as normal growth or high-fat feeding, JNK acts to repress CNS insulin signaling. It has been shown that insulin directly and potently inhibits AgRP neuronal activity (30). Thus, JNK deficiency would result in enhanced insulin signaling in the hypothalamus, leading to hyperpolarization of AgRP neurons and consequently a lean phenotype. Under conditions of negative energy balance such as fasting, insulin levels decline precipitously, removing an inhibitory tone on the AgRP neurons. In the meantime, glucocorticoid levels increase, whereas JNK activities decrease. These combined effects lead to activation of GR function, increased Agrp expression, and heightened refeeding. Taken together, these results suggest that JNK1 can act as a negative or a positive regulator of feeding under different physiological conditions by integrating the relative contributions of glucocorticoids, insulin, and other metabolic signals in the brain.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the Hurlbut Johnson Foundation and the National Institutes of Health Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center Pilot and Feasibility Grant (P30 DK63720) to A.W.X. and by the Swedish Research Council to L.E.O.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online December 18, 2009

Abbreviations: aCSF, Artificial cerebrospinal fluid; AgRP, agouti-related peptide; CNS, central nervous system; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; hrGFP, humanized renilla green fluorescent protein; icv, intracerebroventricular; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NPY, neuropeptide Y; Pomc, Proopiomelanocortin; Tfam, mitochondrial transcription factor A.

References

- Schenk S, Saberi M, Olefsky JM 2008 Insulin sensitivity: modulation by nutrients and inflammation. J Clin Invest 118:2992–3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan JB, Johnson RW 2007 Regulation of food intake by inflammatory cytokines in the brain. Neuroendocrinology 86:183–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delano MJ, Moldawer LL 2006 The origins of cachexia in acute and chronic inflammatory diseases. Nutr Clin Pract 21:68–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarlett JM, Zhu X, Enriori PJ, Bowe DD, Batra AK, Levasseur PR, Grant WF, Meguid MM, Cowley MA, Marks DL 2008 Regulation of agouti-related protein messenger ribonucleic acid transcription and peptide secretion by acute and chronic inflammation. Endocrinology 149:4837–4845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisse BE, Ogimoto K, Tang J, Harris Jr MK, Raines EW, Schwartz MW 2007 Evidence that lipopolysaccharide-induced anorexia depends upon central, rather than peripheral, inflammatory signals. Endocrinology 148:5230–5237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarlett JM, Jobst EE, Enriori PJ, Bowe DD, Batra AK, Grant WF, Cowley MA, Marks DL 2007 Regulation of central melanocortin signaling by interleukin-1β. Endocrinology 148:4217–4225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks DL, Butler AA, Turner R, Brookhart G, Cone RD 2003 Differential role of melanocortin receptor subtypes in cachexia. Endocrinology 144:1513–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW 2006 Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature 443:289–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll AP, Challis BG, López M, Piper S, Yeo GS, O'Rahilly S 2005 Proopiomelanocortin-deficient mice are hypersensitive to the adverse metabolic effects of glucocorticoids. Diabetes 54:2269–2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu AW, Kaelin CB, Morton GJ, Ogimoto K, Stanhope K, Graham J, Baskin DG, Havel P, Schwartz MW, Barsh GS 2005 Effects of hypothalamic neurodegeneration on energy balance. PLoS Biol 3:e415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XY, Shieh KR, Kabbaj M, Barsh GS, Akil H, Watson SJ 2002 Diurnal rhythm of agouti-related protein and its relation to corticosterone and food intake. Endocrinology 143:3905–3915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makimura H, Mizuno TM, Roberts J, Silverstein J, Beasley J, Mobbs CV 2000 Adrenalectomy reverses obese phenotype and restores hypothalamic melanocortin tone in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. Diabetes 49:1917–1923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron DC, Findling JW, Tyrrell JB 2004 Glucocorticoids and adrenal androgens. In: Greenspan FS, Gardner DG, eds. Basic and clinical endocrinology. 7th ed. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill; 366–373 [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan L, Ergin AS, Lu A, Chung J, Sarkar S, Nie D, Myers Jr MG, Ozcan U 2009 Endoplasmic reticulum stress plays a central role in development of leptin resistance. Cell Metab 9:35–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang G, Zhang H, Karin M, Bai H, Cai D 2008 Hypothalamic IKKβ/NF-κB and ER stress link overnutrition to energy imbalance and obesity. Cell 135:61–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoi T, Sasaki M, Miyahara T, Hashimoto C, Matsuo S, Yoshii M, Ozawa K 2008 Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces leptin resistance. Mol Pharmacol 74:1610–1619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RJ 2000 Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell 103:239–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS 2006 Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444:860–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS 2005 Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathways in inflammation and origin of obesity and diabetes. Diabetes 54(Suppl 2):S73–S78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirosumi J, Tuncman G, Chang L, Görgün CZ, Uysal KT, Maeda K, Karin M, Hotamisligil GS 2002 A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature 420:333–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS 2003 Inflammatory pathways and insulin action. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27(Suppl 3):S53–S55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas G, Vilcu C, Neels JG, Bandyopadhyay GK, Luo JL, Naugler W, Grivennikov S, Wynshaw-Boris A, Scadeng M, Olefsky JM, Karin M 2007 JNK1 in hematopoietically derived cells contributes to diet-induced inflammation and insulin resistance without affecting obesity. Cell Metab 6:386–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogatsky I, Logan SK, Garabedian MJ 1998 Antagonism of glucocorticoid receptor transcriptional activation by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:2050–2055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh M, Adachi M, Yasui H, Takekawa M, Tanaka H, Imai K 2002 Nuclear export of glucocorticoid receptor is enhanced by c-Jun N-terminal kinase-mediated phosphorylation. Mol Endocrinol 16:2382–2392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies L, Karthikeyan N, Lynch JT, Sial EA, Gkourtsa A, Demonacos C, Krstic-Demonacos M 2008 Cross talk of signaling pathways in the regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor function. Mol Endocrinol 22:1331–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wu H, Lakdawala VS, Hu F, Hanson ND, Miller AH 2005 Inhibition of Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) enhances glucocorticoid receptor-mediated function in mouse hippocampal HT22 cells. Neuropsychopharmacology 30:242–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu AW, Kaelin CB, Takeda K, Akira S, Schwartz MW, Barsh GS 2005 PI3K integrates the action of insulin and leptin on hypothalamic neurons. J Clin Invest 115:951–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gropp E, Shanabrough M, Borok E, Xu AW, Janoschek R, Buch T, Plum L, Balthasar N, Hampel B, Waisman A, Barsh GS, Horvath TL, Brüning JC 2005 Agouti-related peptide-expressing neurons are mandatory for feeding. Nat Neurosci 8:1289–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wall E, Leshan R, Xu AW, Balthasar N, Coppari R, Liu SM, Jo YH, MacKenzie RG, Allison DB, Dun NJ, Elmquist J, Lowell BB, Barsh GS, de Luca C, Myers Jr MG, Schwartz GJ, Chua Jr SC 2008 Collective and individual functions of leptin receptor modulated neurons controlling metabolism and ingestion. Endocrinology 149:1773–1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Könner AC, Janoschek R, Plum L, Jordan SD, Rother E, Ma X, Xu C, Enriori P, Hampel B, Barsh GS, Kahn CR, Cowley MA, Ashcroft FM, Brüning JC 2007 Insulin action in AgRP-expressing neurons is required for suppression of hepatic glucose production. Cell Metab 5:438–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, Feng Y, Kitamura YI, Chua Jr SC, Xu AW, Barsh GS, Rossetti L, Accili D 2006 Forkhead protein FoxO1 mediates Agrp-dependent effects of leptin on food intake. Nat Med 12:534–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol AN, Yao Y, Fu LY, Foo K, Huang H, Coppari R, Lowell BB, Broberger C 2009 Neuromedin B and gastrin-releasing peptide excite arcuate nucleus neuropeptide Y neurons in a novel transgenic mouse expressing strong Renilla green fluorescent protein in NPY neurons. J Neurosci 29:4622–4639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu H, Arima H, Watanabe M, Goto M, Banno R, Sato I, Ozaki N, Nagasaki H, Oiso Y 2008 Glucocorticoids increase neuropeptide Y and agouti-related peptide gene expression via adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase signaling in the arcuate nucleus of rats. Endocrinology 149:4544–4553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arima H, House SB, Gainer H, Aguilera G 2002 Neuronal activity is required for the circadian rhythm of vasopressin gene transcription in the suprachiasmatic nucleus in vitro. Endocrinology 143:4165–4171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara S, Arima H, Banno R, Sato I, Kondo N, Oiso Y 2003 Regulation of vasopressin gene expression by cAMP and glucocorticoids in parvocellular neurons of the paraventricular nucleus in rat hypothalamic organotypic cultures. J Neurosci 23:10231–10237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ML, Unger EK, Myers Jr MG, Xu AW 2008 Specific physiological roles for signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in leptin receptor-expressing neurons. Mol Endocrinol 22:751–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu AW, Ste-Marie L, Kaelin CB, Barsh GS 2007 Inactivation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons causes decreased POMC expression, mild obesity, and defects in compensatory refeeding. Endocrinology 148:72–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O'Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, Bhagwat SS, Manning AM, Anderson DW 2001 SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:13681–13686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makimura H, Mizuno TM, Isoda F, Beasley J, Silverstein JH, Mobbs CV 2003 Role of glucocorticoids in mediating effects of fasting and diabetes on hypothalamic gene expression. BMC Physiol 3:5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover CA, Rosenfeld RG, Hintz RL 1989 Serum glucocorticoids have persistent and controlling effects on insulinlike growth factor I action under serum-free assay conditions in cultured human fibroblasts. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol 25:521–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte Jr D, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG 2000 Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature 404:661–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker HC, Romsos DR 1992 Glucocorticoids in the CNS regulate BAT metabolism and plasma insulin in ob/ob mice. Am J Physiol 262:E110–E117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HL, Romsos DR 1995 A single intracerebroventricular injection of dexamethasone elevates food intake and plasma insulin and depresses metabolic rates in adrenalectomized obese (ob/ob) mice. J Nutr 125:540–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C, Yang DD, Wysk M, Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ, Flavell RA 1998 Defective T cell differentiation in the absence of Jnk1. Science 282:2092–2095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germano CM, de Castro M, Rorato R, Laguna MT, Antunes- Rodrigues J, Elias CF, Elias LL 2007 Time course effects of adrenalectomy and food intake on cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript expression in the hypothalamus. Brain Res 1166:55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G 2008 c-Jun expression, activation and function in neural cell death, inflammation and repair. J Neurochem 107:898–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza CT, Araujo EP, Bordin S, Ashimine R, Zollner RL, Boschero AC, Saad MJ, Velloso LA 2005 Consumption of a fat-rich diet activates a proinflammatory response and induces insulin resistance in the hypothalamus. Endocrinology 146:4192–4199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollmann MM, Wilson BD, Yang YK, Kerns JA, Chen Y, Gantz I, Barsh GS 1997 Antagonism of central melanocortin receptors in vitro and in vivo by agouti-related protein. Science 278:135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin CB, Gong L, Xu AW, Yao F, Hockman K, Morton GJ, Schwartz MW, Barsh GS, Mackenzie RG 2006 Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) binding sites but not STAT3 are required for fasting-induced transcription of agouti-related protein messenger ribonucleic acid. Mol Endocrinol 20:2591–2602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel HR, Qi Y, Hawkins EJ, Hileman SM, Elmquist JK, Imai Y, Ahima RS 2006 Neuropeptide Y deficiency attenuates responses to fasting and high-fat diet in obesity-prone mice. Diabetes 55:3091–3098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola A, Liu ZW, Andrews ZB, Paradis E, Roy MC, Friedman JM, Ricquier D, Richard D, Horvath TL, Gao XB, Diano S 2007 A central thermogenic-like mechanism in feeding regulation: an interplay between arcuate nucleus T3 and UCP2. Cell Metab 5:21–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luquet S, Phillips CT, Palmiter RD 2007 NPY/AgRP neurons are not essential for feeding responses to glucoprivation. Peptides 28:214–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plum L, Rother E, Münzberg H, Wunderlich FT, Morgan DA, Hampel B, Shanabrough M, Janoschek R, Könner AC, Alber J, Suzuki A, Krone W, Horvath TL, Rahmouni K, Brüning JC 2007 Enhanced leptin-stimulated Pi3k activation in the CNS promotes white adipose tissue transdifferentiation. Cell Metab 6:431–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AA, Marks DL, Fan W, Kuhn CM, Bartolome M, Cone RD 2001 Melanocortin-4 receptor is required for acute homeostatic responses to increased dietary fat. Nat Neurosci 4:605–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.