Abstract

Whereas it is believed that the pancreatic duct contains endocrine precursors, the presence of insulin progenitor cells residing in islets remain controversial. We tested whether pancreatic islets of adult mice contain precursor β-cells that initiate insulin synthesis during aging and after islet injury. We used bigenic mice in which the activation of an inducible form of Cre recombinase by a one-time pulse of tamoxifen results in the permanent expression of a floxed human placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) gene in 30% of pancreatic β-cells. If islets contain PLAP− precursor cells that differentiate into β-cells (PLAP−IN+), a decrease in the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells per total number of IN+ cells would occur. Conversely, if islets contain PLAP+IN− precursors that initiate synthesis of insulin, the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells would increase. Confocal microscope analysis revealed that the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells in islets increased from 30 to 45% at 6 months and to 60% at 12 months. The augmentation in the level of PLAP in islets with time was confirmed by real-time PCR. Our studies also demonstrate that the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells in islets increased after islet injury and identified putative precursors in islets. We postulate that PLAP+IN− precursors differentiate into insulin-positive cells that participate in a slow renewal of the β-cell mass during aging and replenish β-cells eliminated by injury.

Cell lineage analysis reveals that progenitor cells in mouse islets generate new insulin cells in vivo during aging and following islet injury.

The autoimmune destruction of β-cells and the ensuing hyperglycemia are hallmarks of type 1 diabetes. There is currently an active search for approaches to replenish the β-cell population from embryonic stem cells and progenitor cells present in situ to circumvent the need of heterologous islets for transplantation. However, the presence of endocrine precursor cells in adult pancreas has been a controversial issue. The report that the maintenance and growth of the β-cell mass that occur during aging or after partial pancreatectomy are due to replication of preexisting β-cells rather than to β-cell neogenesis (1,2,3) suggested that adult pancreas lack an endogenous β-cell precursor population. Yet other studies suggest an early involvement of neogenesis during recovery of β-cell mass after partial pancreatectomy (4,5) and islet injury (6,7). In particular, the pancreatic duct has long been considered to contain islet precursor cells with the ability to generate new β-cells in adults (5,8,9). Recent studies indicated that partial pancreatectomy induced the appearance of duct cells expressing neurogenin-3 (ngn3), the earliest islet cell-specific transcription factor in development and that these ngn3+ cells initiated insulin synthesis in vitro (10). Moreover, genetic tracing experiments demonstrated that ductal cells contribute to new acinar and islet cell growth during postnatal life and after ductal ligation (11). A recent study conclusively demonstrates that ductal precursors differentiate into glucagon cells and that the expression of the transcription factor paired box (Pax)-4 induces the conversion of α into β-cells (12).

In this study, we examined whether islets contain a progenitor cell compartment that participates in β-cell neogenesis during aging and after islet injury. Previous reports from our laboratory (6,7) suggested the presence of progenitor cells in islets and that these cells differentiate into insulin cells after elimination of preexisting β-cells by streptozotocin (STZ), a β-cell toxin. Because our earlier studies did not distinguish old from the new β-cells, the possibility remained that β-cells that appear after STZ and insulin therapy were old cells that recovered from the STZ treatment rather than newly differentiated cells. We have now reexamined whether adult islets contained precursor β-cells. We used transgenic mice generated by Dor et al. (2), which harbor a transgene comprised of the rat insulin promoter (RIP) linked to an inducible Cre recombinase-estrogen receptor (RIP-CreER) construct. The Cre-estrogen receptor fusion gene is expressed in the cytoplasm of β-cells but is excluded from the nucleus. RIP-CreER mice were crossed with a strain (Z/AP) containing a floxed reporter gene encoding for human placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP). Injection of tamoxifen (TM) into bigenic (RIP-PLAP) mice results in a rapid translocation of the Cre protein to the nucleus, which permits Cre recombination and the expression of PLAP. Cells that do not contain an active RIP-CreER transgene at the time of TM injection lack PLAP, whereas cells in which PLAP is induced by TM permanently retain the expression and transmit it to their progeny. In this study we sought to determine whether the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells changes with time and/or after islet injury. Our results indicate that the ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑IN+ cells increased during aging, participating in the normal turnover of the β-cell mass. We also determined that β-precursors contribute to replace β-cells that are destroyed by chemically induced islet injury. Finally, we identified PLAP+IN− cells in islets. We propose that these cells are precursor β-cells that initiate insulin synthesis and therefore are responsible for the generation of the new β-cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals

RIP-CreER and Z/AP reporter mice were kind gifts from D. A. Melton (Harvard University, Boston, MA). RIP-CreER Z/AP (RIP-PLAP) double-transgenic mice were generated by crossing single heterozygous transgenics. Tamoxifen (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in sterile corn oil at 10 mg/ml, and 0.5 ml was injected ip for 5 d into 2-month-old mice. For the injury experiments, RIP-PLAP mice were injected ip for 5 d with 50 mg/kg STZ (Sigma) dissolved in 0.1 m citrate buffer (pH 4.5) 4 wk after the end of the TM treatment. The day of the first STZ injection was considered d 1. Mice became hyperglycemic after the last injection of STZ (350–400 mg/dl or higher). Blood glucose levels were determined using a Precision QID monitor (MediSense; Abbott Labs, Bedford, MA). Fourteen STZ-treated mice were anesthetized with Nembutal (50 mg/kg; Abbott Labs, Chicago, IL) 7 d after STZ and received two to three insulin implants (Linßit; Linshit Canada Inc., Ontario, Canada) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Animals with blood glucose levels between 40 and 130 mg/dl were considered normoglycemic. Variations in glycemic levels were common in mice receiving insulin implants. This group of normoglycemic RIP-PLAP mice was examined at d 31 after STZ. A second group of mice (×6) did not receive insulin treatment and remained hyperglycemic. Hyperglycemic mice survived for few days after STZ and were not examined. A third group of 20 RIP-PLAP mice were injected with a subdiabetogenic dose of 20 mg/kg STZ for 5 d. These mice remained normoglycemic throughout the study. Control mice were RIP-PLAP mice that received TM and eluent (citrate buffer) but not STZ or insulin therapy. Mice were perfused through the heart with 4% paraformaldehyde buffered to pH 7.4 with 0.1 m PBS. The fixed tissues were infiltrated overnight in 30% sucrose and mounted in embedding matrix (Lipshaw Co., Pittsburgh, PA), and 20-μm cryostat sections were collected onto gelatin-coated slides. All animal protocols were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Mouse genotyping

DNA was extracted from the tail using DNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). For Cre, the following oligonucleotides were used: forward, AACCTGGATAGTGAAACAGGGGC, reverse, TTCCATGGAGCGAACGACGAGACC, which amplified a 400-bp product. Primers were obtained from Eurofino MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL). PCR was performed using Hot Start Taq DNA polymerase (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD). PCR conditions were: 95 C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of 95 C for 1 min, 55 C for 1 min, 72 C for 1 min, and a final extension step at 72 C for 10 min. Lac-Z activity was determined in tail biopsies using the biochemical detection method described elsewhere (13) as modified by Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME).

Immunostaining

Sections were incubated sequentially in an empirically derived optimal dilution of control serum or primary antibody raised in species X overnight and with a 1:200 dilution of the secondary antibodies. For PLAP immunostaining, sections were processed for antigen retrieval (Retrievagen A; BD PharMingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ) before incubation with primary antibody. For multiple label experiments, antibodies produced in different hosts were used. The source and dilution of antibodies is provided in the supplemental information, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org.

Islet isolation and cytospin preparation

Mice were anesthetized with Nembutal (50 mg/kg) and pancreas perfused through the bile duct with 10 ml of a collagenase solution (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ; 2 mg/ml in Hanks’ balanced salt solution) dissociated, islets were handpicked under a dissecting microscope and were incubated in a papain solution [30 U/ml in Earle’s basal salt solution (Worthington] for 60 min at 37 C with gentle agitation. Then islets were washed with Earle’s basal salt solution and triturated using a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. The samples were subjected to cytocentrifugation on pretreated glass slides for 5 min at 125 g (Cytospin 3; Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA). The cytospin preparations were fixed in Zamboni’s solution and processed for immunostaining.

Histochemistry

Sections were washed in buffer (1 m Tris HCl; 1 m NaCl; 1 m MgCl in 0.1 m PBS) for 10 min, overlayed with incubation media (7.5 ml distilled water containing 2.5 ml incubation media, 0.1 mg sodium deoxycholate, 2 μl Nonidet P-40 + 3.4 mg Nitro blue tetrazolium chloride, 1.7 mg 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate) for 20–60 min at room temperature in the dark. At the end of the incubation period, slides were washed and coverslipped with glycerin.

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling

Mice were given BrdU (Sigma) dissolved in water at a concentration of 0.8 mg/ml for 1 wk. The solution was changed every other day. Mice were perfused and the pancreas sectioned as described above. Sections were incubated with 2 n HCl for 20 min and 0.1 n HCl containing 0.5% pepsin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min at 37 C and processed for immunostaining. Rate of proliferation is defined as the number of BrdU+IN+PLAP− cells per total number of IN+PLAP− cells scored and the number of BrdU+IN+PLAP+ per total number of IN+PLAP+ cells scored. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem. Number of scored cells is indicated in the individual experiments.

RNA isolation and semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from islets, using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and further purified with RNAeasy kit (QIAGEN), treated with recombinant deoxyribonuclease-1 (Ambion, Houston, TX). Total RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). PCR conditions were as follows: one cycle of 95 C for 15 min, followed by 28–35 cycles of 94 C for 30 sec, 55 C for 30 sec, and 72 C for 45 sec. The number of cycles was optimized, depending on the particular mRNA abundance and chosen to select PCR amplification on the linear portion of the curve to avoid saturation effect. Aliquots were analyzed by electrophoresis. Information about genes is as follows: human (h) PLAP (35 cycles, annealing: 62 C) (GenBank accession no. NM_001632), amplicon size 205 bp, sense, GAA ACG GTC CAG GCT ATG TG and antisense, ATG ACG TGC GCT ATG AAG GT; 18s rRNA, GenBank accession no. BK000964, amplicon size 68 bp, forward primer, AGT CCC TGC CCT TTG TAC ACA, reverse primer, GAT CCG AGG GCC TCA CTA AAC; cyclophylin A (GenBank accession no. NM_008907, band 150 bp), 5′-GGT GGA GAG CAC CAAG ACA GA-3′ (forward), 5′-GCC GGA GTC GAC AAT GAT G-3′ (reverse). Primers for Ins1 (GenBank accession no. NM_008386, product size: 156 bp) were purchased from SA Biosciences (Frederick, MD). All semiquantitative RT-PCR experiments were confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR using SybrGreen mix (SA Biosciences, Frederick, MD) run on a StepOnePlus cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Apoptosis

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine 5-triphosphate-biotin nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining was carried out as indicated in the manufacturer’s instructions (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). After completion of this step, the slides were processed for visualization of glucagon to mark the perimeter of the islet. The number of apoptotic cells was expressed as the percentage of the total number of islet cells scored. Results were expressed as the mean values of all animals examined for each time point ± sem.

Relative β-cell mass

The relative number of β-cells per section was determined in sections immunostained for insulin by the point-sampling method using a 300-point ocular grid at a total magnification of ×400. The relative IN+ cell mass per section was calculated by dividing the number of points over immunostained cells over the number of points scored for that section. Similar sections through the pancreatic duct were selected for counting. Five thousand points were scored per animal, three mice per stage. Results were expressed as mean values of all animals at each time point ± sem.

Confocal microscopy

A laser-scanning confocal microscope (BioRad radiance 2000; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), fitted with a Zeiss Axioskop Z upright microscope (Carl Zeiss). Typically, 0.7-μm vertical steps were used with a vertical optical resolution of less than 1.0 μm.

Determination of percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells

Confocal microscope images were processed using Photoshop. Images (8 × 10 in.) were first printed using all three color channels (blue, red, and green). To clearly visualize the PLAP+ (green) cells, the blue and red channels were eliminated and a second printout was done of cells immunostained with the green fluorophore. The number of IN+ cells and PLAP+IN+ cells in the islet was counted in the first print. The number of PLAP+ (green only) cells was counted in the second print. The number of PLAP+ IN+ of the first print and of PLAP+ of the second print was identical except for the occasional PLAP+IN− cells.

Statistical analysis

All values are shown as mean ± sem. For comparison between two groups, the unpaired t test (two tail) was used. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Slow renewal of pancreatic β-cells

We first tested the specificity of PLAP expression to β-cells. Confocal microscopic analysis of sections of pancreas of RIP-PLAP mice revealed that a subset of IN cells of islets expressed PLAP (supplemental Fig. S1A). In agreement with Dor et al. (2) and using a similar dose of TM, 30.1 ± 1.16% IN+ cells expressed PLAP (PLAP+IN+cells, a total of 5321 IN+ cells from four 3 month old mice were scored). In contrast, α- and δ-cells did not express PLAP (supplemental Fig. S1, B and C, respectively).

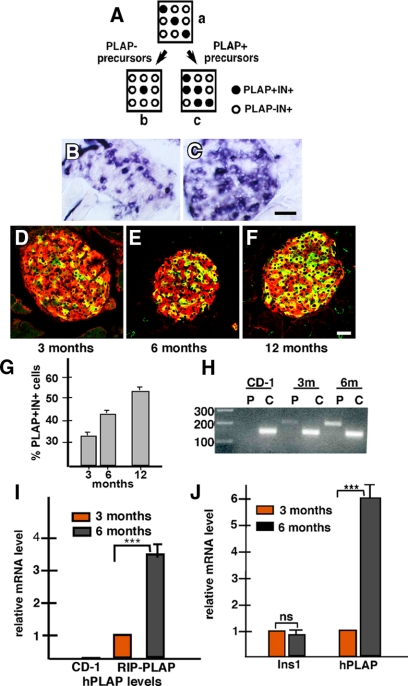

We then sought to determine whether the ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑IN+ cells changed with time. We speculated that if islets contain PLAP− precursor cells that differentiate into β cells (PLAP−IN+), a decrease in the ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑IN+ cells would occur (Fig. 1, A–b). Conversely, if islets contain PLAP+ precursors that do not express the endogenous insulin gene and if these PLAP+IN− cells later become insulin positive (PLAP+IN+), the ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑IN+ cells present in the islet would increase (Fig. 1, A–c).

Figure 1.

β-Cell neogenesis during aging. Panel A, Possible islet cell composition after β-cell neogenesis. Squares represent islets; open and filled circles represent PLAP−IN+ and PLAP+IN+ β-cells, respectively. In a, it is assumed that the efficiency of PLAP expression by IN+ cells is 30%. If PLAP− precursors differentiate into β-cells, these cells will lack PLAP expression and the ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑IN+ cells will decrease (b). Conversely, if islets contain PLAP+IN− cells that initiate insulin expression, the ratio will increase (c). Panels B and C, Histochemical visualization of AP activity in islets of 3- (panel B) and 12-month-old (panel C) RIP-PLAP mice. Note the increase in the number of positive (blue) cells. Panels D–F, Immunohistochemical visualization of PLAP (green) and insulin (red) in islets from 3- (panel D), 6- (panel E), and 12-month-old (panel F) RIP-PLAP mice, respectively. Note the increase in the number of PLAP+IN+ cells (yellow) with age. Bar, 30 μm. Panel G, The percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells was determined in islets of 3- (four mice), 6- (two mice), and 12-month-old (one mouse) RIP-PLAP mice. A total of 5321, 4378, and 1554 IN+ cells were scored at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively. Results from all mice examined per stage were pooled and the mean ± sem obtained. Panel H, Semiquantitative PCR analysis of hPLAP in control CD-1-, 3-, and 6-month-old RIP-PLAP mice. P, hPLAP; C, cyclophylin. Molecular weight size in base pairs are indicated. Note the absence of hPLAP expression in islets of CD-1 mice and the significant increase in islets of 6-month-old RIP-PLAP mice compared with 3-month-old mice. Panel I, Histogram summarizes results of three independent experiments. Relative mRNA levels were normalized against cyclophylin; bands were quantified by densitometric analysis. Panel J, Confirmation of semiquantitative results by real-time PCR. The level of hPLAP mRNA in islets increases with age of the mice. Relative gene expression quantification, normalized to cyclophylin, of three independent experiments performed on RNA samples isolated from 3- and 6-month-old RIP-PLAP mice. There was nonsignificant change in the relative expression of Ins1 and a 6.1 ± 0.5-fold increase in hPLAP in 6-month-old RIP-PLAP compared with 3-month-old mice. ***, P < 0.001, highly significant. ns, Not significant.

Islets of RIP-PLAP mice were examined at 3, 6, and 12 months. We found the number of cells positive for alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity was higher in islets of the older than islets of the younger group (Fig. 1, B and C). To determine whether the cells expressing AP were β-cells, sections were immunostained for visualization of PLAP and insulin. This analysis revealed an increase in the number of IN+PLAP+ double-labeled cells with time (Fig. 1, D–F). Morphometric analysis of immunostained sections indicated that the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells rose from 30 to 45% at 6 months and to near 60% at 12 months (Fig. 1G). Comparison of islets from 3- and 6-month mice by semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis confirmed the increase in PLAP mRNA levels in islets from the older stage (Fig. 1, H and I). Real-time PCR analysis confirmed the increase in hPLAP mRNA levels in older mice (Fig. 1J). In contrast to hPLAP, the levels of insulin mRNA was similar in islets from both ages of mice (Fig. 1J). These findings suggest that islets contain PLAP+IN− precursors that initiate insulin synthesis, resulting in an increase of the proportion of PLAP+IN+ cells. To exclude the possibility that the increase in the ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑IN+ cells was due to selective proliferation of PLAP+IN+ cells, islets of 3-month-old RIP-PLAP mice that received BrdU for 1 wk were examined. We found that PLAP+IN+ and PLAP−IN+ cells had similar rates of proliferation (3.5 ± 0.17% PLAP+IN+ cells and 3.1% ± 0.22 PLAP−IN+ cells were BrdU+; a total of 150 PLAP+IN+ cells and 500 PLAP−IN+ cells from three mice were scored).

New β-cells populate islets after islet injury

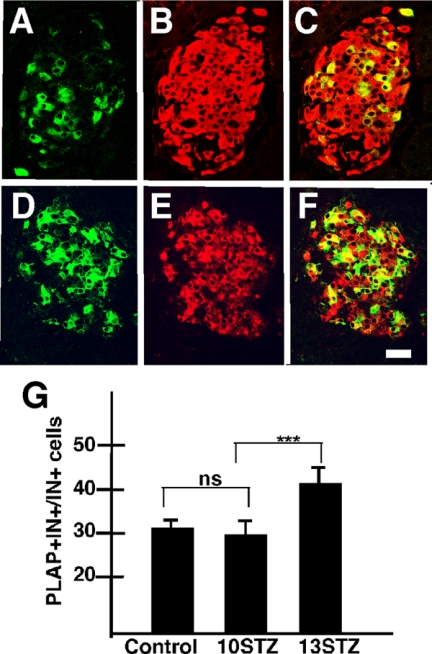

To ascertain whether PLAP+ precursor participate in β cell neogenesis after islet injury, RIP-PLAP mice that were injected with 50 mg/kg STZ and received insulin pellets to restore normoglycemia were examined. RIP-PLAP mice injected with eluent (citrate buffer) were considered controls. Immunohistochemical (Fig. 2, A–F) and morphometric analysis was performed at 31 d after STZ. At this time the ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑IN+ cells was higher (41 ± 2.28%) in islets of normoglycemic RIP-PLAP (+50 mg/kg STZ and IN therapy) mice than in islets of control RIP-PLAP mice (29.3 ± 2.1%; P < 0.001; three mice per group and more than 2000 cells examined per mouse).

Figure 2.

β-Cell neogenesis after injury. Photomicrograph illustrates an islet of control RIP-PLAP mice (A–C) and a mouse injected with 50 mg/kg and examined at 31 d after STZ (D–F), respectively. Both sections were processed for immunostaining for PLAP (green, A and D) and insulin (red, B and E). C = A + B; F = D + E. In C and F, PLAP+IN+ cells are yellow. Note that the relative number of PLAP+IN+ cells is higher in the islet from normoglycemic than the islet from control (no STZ) RIP-PLAP mice. Bar, 30 μm. Comparable results were obtained with mice injected with a subdiabetogenic dose of STZ (not shown). G, The ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑IN+ cells was determined in pancreatic islets of RIP-PLAP mice injected with 20 mg/kg STZ at 10, 11, and 13 d after the first injection of the toxin. Note that the ratio increased more than 30% between d 11 and 13. Results are the mean ± sem of values obtained from four mice per stage; more than 2000 IN+ cells scored per mouse. ***, P < 0.001. ns, Not significant.

To determine whether the rapid increase in the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells is elicited only by acute injury to the islet, RIP-PLAP mice injected with a multiple subdiabetogenic dose of STZ (20 mg/kg for 5 d) were examined at 10, 11, and 13 d after the onset of the treatment. We found that the ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑IN+ cells in islets of STZ-treated RIP-PLAP mice was similar to controls (no STZ) 10 d after the initiation of STZ treatment and increased significantly 3 d later, at 13 d after STZ (Fig. 2G). This increase was similar to that present in mice that received 50 mg/kg of STZ, suggesting that mild injury also activated β-cell neogenesis. Taken together, these observations suggest that new β-cells may differentiate during the initial stages of type I diabetes before the appearance of severe islet damage and hyperglycemia.

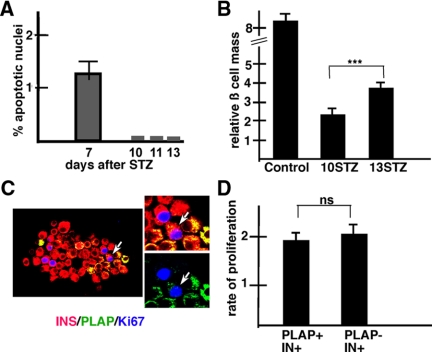

To exclude that the increase in the ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑ IN+ cells was due to selective death of PLAP−IN+ cells after STZ treatment, we processed pancreas of mice injected with 20 mg/kg STZ for visualization of apoptotic nuclei using the TUNEL technique. The frequency of apoptotic nuclei decreased from d 7 to a nadir at d 10, 11, and 13 (from the first injection of STZ), the last stage examined (Fig. 3A). As a result of apoptosis, the β-cell mass at d 10 was 30% lower than in controls (Fig. 3B). However, the mass of IN+ cells increased significantly between d 10 and 13 (Fig. 3B). This increase is mostly due to the active β-cell proliferation in STZ mice (Fig. 3C). Significantly, PLAP−IN+ and PLAP+IN+ cells had similar rates of proliferation at d 10 after STZ (Fig. 3D). Collectively, these findings suggest that the increase in the ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑IN+ was not due to selective cell death of PLAP−IN+ or selective proliferation of PLAP+IN+ cells.

Figure 3.

Role of apoptosis and proliferation. A, Apoptosis. The rate of apoptosis was determined at different time points after the administration of 20 mg/kg STZ. The high rate of apoptosis found at 7 d after STZ decreased to almost undetectable levels at d 10–13. Results show the mean ± se of the percentage of TUNEL+ per number of IN+ cells. A total of 6310 IN+ cells from three mice per stage were scored. B, β-Cell mass. Injection of 20 mg/kg STZ induced a decrease in β-cell mass. The β-cell mass in control (no STZ) mice and in mice at 10 and 13 days STZ is compared. Note that the β-cell mass at d 10 was lower than in controls and increased significantly between d 10 and 13. ***, P < 0.001, highly significant. C, The rate of β-cell proliferation increases after a subdiabetogenic dose of STZ. Islets removed from RIP-PLAP mice were cytospun onto slides and immunostained for visualization of insulin (red) PLAP (green), and Ki67 (blue). One PLAP+IN+Ki67+ cell, indicated with an arrow, is shown magnified. D, Proliferation. The rate of proliferation was measured in cytospun preparations from three mice. The percentage of PLAP+IN+Ki67+/PLAP+IN+ and PLAP−IN+Ki67+/PLAP−IN+ cells scored was determined, respectively. Note that PLAP+IN+ and PLAP−IN+ cells have similar rates of proliferation. A total of 1575 PLAP−IN+ and 341 IN+PLAP+ cells were scored per mouse. ns, Not significant.

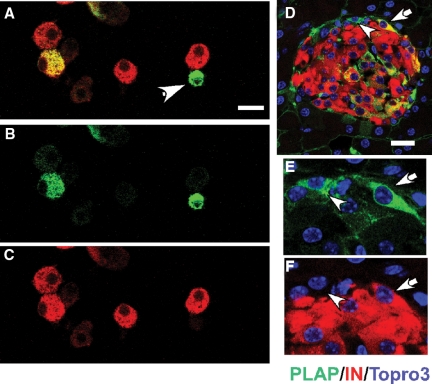

Putative precursor cells

The increase in the ratio of PLAP+IN+/∑IN+ cells suggested to us that islets contained precursors expressing PLAP but not insulin and that these cells differentiated into PLAP+IN+ cells after aging or STZ-induced islet injury. Detailed examination of tissue sections revealed the presence of PLAP+ cells in islets of control (no STZ) RIP-PLAP mice that did not contained insulin (Fig. 4) or C-peptide (not shown). PALP+IN− cells lacked the glucose transporter 2 (supplemental Fig. S2), and nestin (not shown), an intermediate filament that labels putative adult endocrine stem cells (14). PLAP+IN− cells were observed using mouse, goat, or rabbit PLAP sera and were not seen in sections in which the primary antibody was replaced by buffer (supplemental Fig. S3A). Sections of the pancreatic exocrine tissue, pancreatic duct, liver, kidney, or heart of RIP-PLAP mice injected with TM (not shown) or RIP-PLAP mice not injected with TM lacked cells immunostained for PLAP (supplemental Fig. S3B). This excludes any detectable leakage of the transgene. In addition, islets of CD-1 mice injected with STZ did not contain PLAP+ cells, indicating that the presence of PLAP immunoreactivity was not due to a nonspecific action of STZ (supplemental Fig. S3, C and D). The percentage of PLAP+IN− cells per total number of IN+ cells in cytospin preparation of a total of 800 islets from four 3-month-old control (no STZ) mice was 0.1 ± 0.008%, and their size (913 ± 85 μm3) was almost 2-fold smaller than that of IN+ cells (1985 ± 200 μm3).

Figure 4.

Islets contain PLAP+IN− cells. A–C, Identification of PLAP+IN− cells in cytospin preparations. Islets of control RIP-PLAP mice were dissociated and processed for immunocytochemical visualization of PLAP (green) and insulin (red). Staining for A, PLAP+IN; B, PLAP; C, insulin. Cells indicated with arrowhead in A express only PLAP. Nuclei are visualized with Topro 3, a nuclear stain. Bar, 20 μm. D and E, Identification of PLAP+IN− cells in a tissue section of control RIP-PLAP mouse Photomicrographs illustrate an islet stained for IN (red) and PLAP (green) obtained with a confocal microscope. Cell identified with an arrow in D is shown magnified in E (PLAP) and F (IN). Note the lack of insulin staining in the position of the PLAP+ cell. Bar (D), 20 μm.

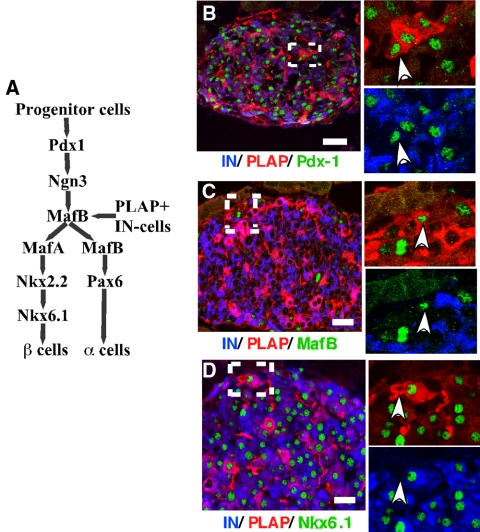

Then we investigated whether the transcription factor (TF) profile of PLAP+IN− cells was similar to that reported for precursor β-cells in embryos. Recent studies identified the molecular signals that control the stepwise program of islet cell differentiation in embryos (15,16). An initial group of TF (Fig. 5A) includes the homeodomain protein pancreatic duodenal homeobox (Pdx)-1 or insulin promoter factor, which establishes the pancreatic fate of the embryonic endoderm and the basic helix loop helix factor ngn3, a transcription factor that drives the differentiation of embryonic and adult pancreatic epithelial cells to the endocrine fate (10,17,18,19,20). Another group of TF, required for α- and β-cell differentiation and maturation, comprise Nkx2.2 and Nkx6.1 (15), Pax6 (15), and the members of the V-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog (avian) (Maf) family of regulators MafA and MafB (21,22,23,24) (Fig. 5A). MafB is expressed by endocrine precursors and mature α-cells (25,26) whereas MafA is a TF characteristic of the β-cell lineage (23).

Figure 5.

Molecular analysis of PLAP+IN− cells. A, Proposed model representing some of the transcription factors implicated in the specification of the α- and β-cell lines during embryonic development. Transcription factor analysis suggests that PLAP+IN− cells express a molecular phenotype similar to that of cells expressing Pdx-1 and MafB. Our results also suggest that transcription factors that appear after the divergence of the α- and β-cell lineages are expressed in PLAP+IN− cells concomitantly with the initiation of expression of the endogenous insulin gene [modified from other publications (15,16,27)]. B–D, Progenitor β-cells of control mice express transcription factors characteristic of early precursor β-cells. Photomicrograph obtained using a confocal microscope illustrates islet of RIP-PLAP mice immunostained for visualization of insulin (blue), PLAP (red), and different transcription factors (green). Insets on the right are high magnification of the area indicated with a dotted rectangle. B, Insulin, PLAP, and PDX-1. Inset, Cell indicated with an arrowhead is PLAP+IN−Pdx-1+; C, IN, PLAP, and MafB. Inset, Cell indicated with arrowhead is PLAP+IN−MafB+; D, IN, PLAP, and NKx6.1. Inset, Cell indicated with an arrowhead is PLAP+IN−NKx6.1−. At least 30 islets/mouse per three mice per antibody combination were examined. Bars, 20 μm.

Histological analysis revealed that 50% PLAP+IN− cells expressed Pdx-1 (Fig. 5B) and 33% MafB (Fig. 5C), respectively (n = 18 cells scored/antibody combination). All PLAP+IN− cells of control RIP-PLAP mice scored negative for Nkx6.1 (0/20 cells scored) (Fig. 5D), Pax6, MafA, and Nkx2.2 (not shown). As expected, mature β-cells (PLAP+IN+ and PLAP−IN+ cells) expressed Pdx-1 (Fig. 5B), Nkx6.1 (Fig. 5D), Pax6, MafA, and Nkx2.2 (not shown). A similar analysis performed in islets of normoglycemic RIP-PLAP mice that received 50 mg/kg STZ indicated that the percentage of PLAP+IN− cells expressing Pdx-1 and MafB was significantly higher (80% PLAP+IN− cells expressed Pdx-1 or MafB, respectively, 25 cells scored/antibody combination) than in control (no STZ) RIP-PLAP mice. However, the cells remained negative for Nkx6.1 or Nkx2.2 (18 cells scored/antibody combination) (supplemental Fig. S4). These results suggest that the position of the PLAP+IN− cells in the islet cell lineage is one associated with early β-cell differentiation. They also suggest that, after islet injury, the molecular profile of most PLAP+IN− cells did not advance further in the program of β-cell differentiation before the initiation of insulin synthesis.

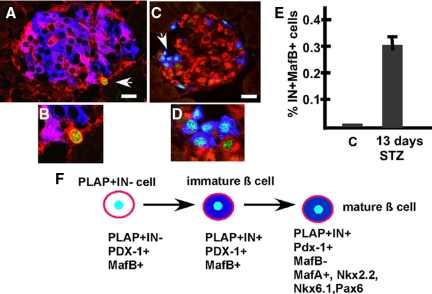

To ascertain whether PLAP+IN− cells proliferate, we analyzed tissue sections incubated with antibodies to IN, PLAP, and the proliferation marker Ki67. We found that islets of control (no STZ) RIP-PLAP mice did not contain PLAP+IN−Ki67+ cells (0/20 cells scored; 20 islets/mouse per three mice examined). In contrast, five of 25 PLAP+IN− cells of STZ-treated RIP-PLAP mice (more than 25 islets/mouse per three mice examined) expressed Ki67 (Fig. 6, A and B). These observations suggest that PLAP+IN− cells present in injured islets were proliferating, whereas those populating islets of control mice had a slow replication rate or were mitotically quiescent cells.

Figure 6.

A and B, Progenitor β-cells proliferate after islet damage. Panel A, Confocal microscope visualization of an islet of normoglycemic RIP-PLAP mice processed for visualization of PLAP (red), IN (blue), and Ki67 (green). Cell indicated with an arrow is PLAP+IN−Ki67+and is illustrated with higher magnification in panel B. Bar, 20 μm. Panels C and D, Presence of IN+MafB+ cells in islets of STZ-treated mice. Panel C, Photomicrographs of an islet of STZ-treated RIP-PLAP mice immunostained for IN (red), glucagon (blue), and MafB (green) obtained with a confocal microscope. Cell cluster identified with an arrow in panel C is shown magnified in panel D. Note the presence of MafB+IN+ and MafB+GLU+ cells. Bar (panel C), 20 μm. Panel E, The percentage of MafB+IN+ cells was determined in islets of control (20 islets per mouse per three mice examined) and RIP-PLAP mice 13 d after the injection of a subdiabetogenic dose of STZ (4351 IN+ cells per three mice scored). Panel F, Proposed model of β-cell precursor differentiation in RIP-PLAP mice. After STZ, PLAP+IN− cells expressing Pdx-1 and MafB initiate insulin synthesis. Subsequently these PLAP+ immature β-cells inhibit MafB expression and differentiate into mature β-cells expressing MafA, Nkx2.2, Nkx6.1, and Pax6 in addition to Pdx-1. C, Control (no STZ) RIP-PLAP mice.

During development, immature β-cells transiently express MafB and then initiate MafA expression when they mature (26). If PLAP+IN− precursors recapitulate this developmental sequence when they begin their differentiation into IN+ cells, it is likely that they will initially express MafB. In confirmation of previous reports (25,26,27), islets of 3-month-old control RIP-PLAP mice did not contain IN+MafB+ cells (60 islets per three mice examined, results not shown). In contrast, at 13 d after STZ, 0.7 ± 0.21% IN+ cells expressed MafB (Fig. 6E, a total of 4351 IN+ cells per three mice scored). We noted that IN+MafB+ cells were always found in the periphery of the islets (Fig. 6C), in which precursor β-cells are believed to be located (12). Presumably the presence of IN+MafB+ cells in islets after injury, but not in islet of control (no STZ) mice, may be correlated with the rate of β-cell neogenesis. In contrast to MafB, islets of RIP-PLAP mice at 10 and 13 d after the injection of STZ did not contain cells expressing ngn3 (not shown). However, this absence may reflect the low activity of the ngn3 promoter because genetic lineage analysis revealed the presence of ngn3+ cells in adult pancreas (28,29).

Discussion

The presence of precursor β-cells in pancreatic islets has been a highly controversial issue because newly differentiated β-cells could not be distinguished from the preexisting population in many experimental models. The mouse model used in this study circumvents this issue by allowing permanent genetic labeling of a subset of β-cells and their progeny at one specific time point and then examining whether the percentage of labeled cells (PLAP+IN+ cells) significantly increased during aging and after islet injury. Our results indicate that the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells doubles over a 9-month period from 30 to 60%, suggesting that there is a slow renewal of the β-cell population during aging. By this process of replacement, old PLAP+IN+ and PLAP−IN+ cells die and are gradually replaced by PLAP+IN− precursors that initiate insulin synthesis. It could be proposed that, like the mature β-cell population, 30% of the cells in the precursor pool express PLAP. If so, old PLAP+IN+ and PLAP−IN+ cells already present in islets would be replaced during aging/islet injury by newly differentiated cells without changing the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells in islets. However, the fact that the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells increased suggest that most cells of these precursor pool had an active insulin promoter at the time of TM injection, resulting in the activation of PLAP expression. Our results also suggest that PLAP+IN− cells later initiated insulin expression and contributed to the increase in percentage of this β-cell type in islets (Fig. 6F).

Our findings disagree with the observations reported by Dor et al. (2), indicating that the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells remained unchanged with time. These authors interpreted this observation as evidence that most β-cells originate from proliferation of mature β-cells without any contribution from a precursor pool. The reason for this important discrepancy is likely to be related to differences in the techniques used for double-labeling tissue sections to detect PLAP and IN. Dor et al. (2) stained sections of pancreas using the peroxidase-antiperoxidase technique and chromogens of different colors to visualize insulin (brown) and PLAP (blue). However, it is well known that this enzyme based double-staining method is not suitable for the simultaneous localization of two cytoplasmic or two nuclear proteins because the overlap of both colors in the same cellular domain does not allow to distinguish the distribution of the individual antigens (30). Use of the enzyme-based immunohistochemistry is limited for the demonstration of two proteins at different locations in the cell (i.e. cytoplasmic vs. nuclear). The use of the PAP technique probably hindered the visualization of the changes we observed using confocal analysis.

Islet injury also induced a significant increase in the percentage of PLAP+IN+ cells in islets. In mice injected with a subdiabetogenic dose of STZ, this increase took place between d 10 and 13 after STZ, after the decline in STZ-induced cell death that occurred after d 10. Presumably β-cell precursors that participate in normal β-cell renewal were activated by islet injury, accelerating the process of differentiation into insulin producing cells. The fact that 0.1% of islet cells of controls (no STZ) are PLAP+IN− cells suggests that these cells proliferated every 24–36 h, and their relative number grew exponentially from the time the mice were injected with STZ until they were examined 10–12 d later. Our observations also suggest that the accumulated PLAP+IN− cells initiated synthesis of insulin after the decline in STZ-induced cell death after d 10 after STZ.

The origin of the PLAP+IN− cells remains to be determined. It is unlikely that these cells originate from transdifferentiation of exocrine cells because PLAP+ cells were not seen in this tissue. It could be proposed that PLAP+IN− cells originate from precursors residing in the bone marrow because it has been reported that bone marrow cells transdifferentiate into functionally competent pancreatic cells (31). However, we failed to detect PLAP mRNA in the bone marrow of RIP-PLAP mice (Kedees, M. H., and G. Teitelman, unpublished data). It is also possible that PLAP+IN− cells are generated during early development and home to the islets along with the differentiated β-cells. Analysis of other mouse line harboring a transgene comprised of the same sequence of the RIP promoter (32) linked to the gene-coding sequence of a different reporter protein indicated that the RIP transgene was active in almost all glucagon and the few insulin cells found during the first wave of pancreatic differentiation (33), which is believed to extend from embryonic d 10–14. Expression of the RIP transgene became restricted to β-cells after embryonic d 14 (34). Presumably differences in the pattern of expression of the RIP transgene and endogenous insulin gene in this older line and in RIP-PLAP mice is due to the lack of regulatory regions controlling expression of the foreign gene (reviewed in Ref. 35). It can also be proposed that ductal precursors described by others (10,11,12) invade the islets of postnatal and adults mice, slowly renewing the β-cell population and that this migration is accelerated after islet injury. Whereas we did not find PLAP+IN− cells in the pancreatic duct or its periphery, it is possible they were not detected because the number of precursor cells present at any given time is small. Finally, it could be argued that PLAP+IN− cells are mature cells that expressed IN at the time of TM injection and then dedifferentiated, losing the expression of the hormone and acquiring an immature phenotype and remaining in the islets as putative precursor β-cells. Further studies are required to distinguish between these possibilities. It also remains to determine whether PLAP+IN− cells found in adult islets derive, like the embryonic β-cell precursors, from cells expressing ngn3 (18,29,36).

In conclusion, our results suggest that islets contain insulin-negative pre-β-cells and that these cells differentiate into mature IN+ cells after islet injury. These precursors could participate in β-cell neogenesis after not only STZ-induced islet injury but also the destruction of β-cells that precedes type 1 diabetes. The identification and modulation of the signals that activate proliferation and differentiation of the β-cell progenitors will also allow the expansion of the β-cell population in vitro, which would facilitate their use for transplantation therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Douglas Melton (Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA) for providing the transgenic mice.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International, and New York State Stem Cell Science Foundation.

Disclosure Summary: H.L., Y.G., M.H.K., J.W., and G.T. have nothing to declare.

First Published Online January 7, 2010

Abbreviations: AP, Alkaline phosphatase; BrdU, 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; Cre, Cre recombinase; h, human; ngn3, neurogenin-3; Pax, paired box gene; Pdx, pancreatic duodenal homeobox; PLAP, placental AP; RIP, rat insulin promoter; RIP-CreER, Cre recombinase-estrogen receptor; STZ, streptozotocin; TF, transcription factor; TM, tamoxifen; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine 5-triphosphate-biotin nick-end labeling.

References

- Brennand K, Huangfu D, Melton D 2007 All β cells contribute equally to islet growth and maintenance. PLoS Biol 5:e163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dor Y, Brown J, Martinez OI, Melton DA 2004 Adult pancreatic β-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature 429:41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teta M, Rankin MM, Long SY, Stein GM, Kushner JA 2007 Growth and regeneration of adult β cells does not involve specialized progenitors. Dev Cell 12:817–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann Misfeldt A, Costa RH, Gannon M 2008 β-Cell proliferation, but not neogenesis, following 60% partial pancreatectomy is impaired in the absence of FoxM1. Diabetes 57:3069–3077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner-Weir S, Baxter LA, Schuppin GT, Smith FE 1993 A second pathway for regeneration of adult exocrine and endocrine pancreas: a possible recapitulation of embryonic development. Diabetes 42:1715–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes A, King LC, Guz Y, Stein R, Wright CV, Teitelman G 1997 Differentiation of new insulin producing cells is induced by injury in adult pancreatic islets. Endocrinology 138:1750–1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guz Y, Nasir I, Teitelman G 2001 Regeneration of pancreatic β cells from intra-islet precursor cells in an experimental model of diabetes. Endocrinology 142:4956–4968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner-Weir S 2000 Perspective: postnatal pancreatic β cell growth. Endocrinology 141:1926–1929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwens L, Rooman I 2005 Regulation of pancreatic β-cell mass. Physiol Rev 85:1255–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, D'Hoker J, Stangé G, Bonné S, De Leu N, Xiao X, Van de Casteele M, Mellitzer G, Ling Z, Pipeleers D, Bouwens L, Scharfmann R, Gradwohl G, Heimberg H 2008 β Cells can be generated from endogenous progenitors in injured adult mouse pancreas. Cell 132:197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada A, Nienaber C, Katsuta H, Fujitani Y, Levine J, Morita R, Sharma A, Bonner-Weir S 2008 Carbonic anhydrase II-positive pancreatic cells are progenitors for both endocrine and exocrine pancreas after birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:19915–19919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collombat P, Xu X, Ravassard P, Sosa-Pineda B, Dussaud S, Billestrup N, Madsen OD, Serup P, Heimberg H, Mansouri A 2009 The ectopic expression of Pax4 in the mouse pancreas converts progenitor cells into α and subsequently β cells. Cell 138:449–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murti JR, Schimenti JC 1991 Microwave-accelerated fixation and lacZ activity staining of testicular cells in transgenic mice. Anal Biochem 198:92–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulewski H, Abraham EJ, Gerlach MJ, Daniel PB, Moritz W, Muller B, Vallejo M, Thomas MK, Habener JF 2001 Multipotential nestin-positive stem cells isolated from adult pancreatic islets differentiate ex vivo into pancreatic endocrine, exocrine, and hepatic phenotypes. Diabetes 50:521–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collombat P, Hecksher-Sørensen J, Serup P, Mansouri A 2006 Specifying pancreatic endocrine cell fates. Mech Dev 123:501–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J 2004 Gene regulatory factors in pancreatic development. Dev Dyn 229:176–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradwohl G, Dierich A, Lemeur M, Guillemot F 2000 Neurogenin 3 is required for the development of the four endocrine cell lineages of the pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:1607–1611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu G, Dubauskaite J, Melton DA 2002 Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development 129:2447–2457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J, Heller RS, Funder-Nielsen T, Pedersen EE, Lindsell C, Weinmaster G, Madsen OD, Serup P 2000 Independent development of pancreatic α and β-cells from neurogenin-3 expressing precursors. A role for notch pathway in repression of premature differentiation. Diabetes 49:163–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Smith SB, Watada H, Lin J, Scheel D, Wang J, Mirmira RG, German MS 2001 Regulation of the pancreatic pro-endocrine gene neurogenin 3. Diabetes 50:928–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka K, Han SI, Shioda S, Hirai M, Nishizawa M, Handa H 2002 MafA is a glucose-regulated and pancreatic β-cell-specific transcriptional activator for the insulin gene. J Biol Chem 2002:49903–49910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka K, Shioda S, Ando K, Sakagami K, Handa H, Yasuda K 2004 Differentially expressed Maf family transcription factors, c-Maf and MafA, activate glucagon and insulin gene expression in pancreatic islet α- and β-cells. J Mol Endocrinol 32:9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka TA, Artner I, Henderson E, Means A, Sander M, Stein R 2004 The MafA transcription factor appears to be responsible for tissue-specific expression of insulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:2930–2933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka TA, Zhao L, Artner I, Jarrett HW, Friedman D, Means A, Stein R 2003 Members of the large Maf transcription family regulate insulin gene transcription in islet β cells. Mol Cell Biol 23:6049–6062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artner I, Le Lay J, Hang Y, Elghazi L, Schisler JC, Henderson E, Sosa-Pineda B, Stein R 2006 MafB: an activator of the glucagon gene expressed in developing islet α- and β-cells. Diabetes 55:297–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura W, Kondo T, Salameh T, El Khattabi I, Dodge R, Bonner-Weir S, Sharma A 2006 A switch from MafB to MafA expression accompanies differentiation to pancreatic β-cells. Dev Biol 293:526–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artner I, Blanchi B, Raum JC, Guo M, Kaneko T, Cordes S, Sieweke M, Stein R 2007 MafB is required for islet β cell maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:3853–3858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu G, Brown JR, Melton DA 2003 Direct lineage tracing reveals the ontogeny of pancreatic cell fates during mouse embryogenesis. Mech Dev 120:35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Jensen JN, Seymour PA, Hsu W, Dor Y, Sander M, Magnuson MA, Serup P, Gu G 2009 Sustained Neurog3 expression in hormone-expressing islet cells is required for endocrine maturation and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:9715–9720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesande F 1983 Immunohistochemical double staining techniques. In: Cuello AC, ed. Immunohistochemistry. Chichester, NY, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: John Wiley and Sons; 257–271 [Google Scholar]

- Ianus A, Holz GG, Theise ND, Hussain MA 2003 In vivo derivation of glucose-competent pancreatic endocrine cells from bone marrow without evidence of cell fusion. J Clin Invest 111:843–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D 1985 Heritable formation of pancreatic β-cell tumours in transgenic mice expressing recombinant insulin/simian virus 40 oncogenes. Nature 315:115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpert S, Hanahan D, Teitelman G 1988 Hybrid insulin genes reveal a developmental lineage for pancreatic endocrine cells and imply a relationship with neurons. Cell 53:295–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pictet R, Rutter WJ 1972 Development of the embryonic pancreas. In: Steiner DF, Frenkel N, eds. Handbook of physiology, section 7. Washington, DC: American Physiological Society; 25–66 [Google Scholar]

- Dumonteil E, Philippe J 1996 Insulin gene: organisation, expression and regulation. Diabetes Metab 22:164–173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson KA, Dursun U, Jordan N, Gu G, Beermann F, Gradwohl G, Grapin-Botton A 2007 Temporal control of neurogenin3 activity in pancreas progenitors reveals competence windows for the generation of different endocrine cell types. Dev Cell 12:457–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]