Abstract

Whether insulin or IGFs regulate glycogen synthesis in the fetal liver remains to be determined. In this study, we used several knockout mouse strains, including those lacking Pdx-1 (pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1), Insr (insulin receptor), and Igf2 (IGF-II) to determine the role of these genes in the regulation of fetal hepatic glycogen synthesis. Our data show that insulin deficiency does not alter hepatic glycogen stores, whereas Insr and Igf2 deficiency do. We found that both insulin receptor isoforms (IR-A and IR-B) are present in the fetal liver, and their expression is gestationally regulated. IR-B is highly expressed in the fetal liver; nonetheless, the percentage of hepatic IR-A isoform, which binds Igf2, was significantly higher in the fetus than the adult. In vitro experiments demonstrate that Igf2 increases phosphorylation of hepatic Insr, insulin receptor substrate-2, and Akt proteins and also the activity of glycogen synthase. Igf2 ultimately increased glycogen synthesis in fetal hepatocytes. This increase could be blocked by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor LY294008. Taken together, we propose Igf2 as a major regulator of fetal hepatic glycogen metabolism, the insulin receptor as its target receptor, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase as the signaling pathway leading to glycogen formation in the fetal liver.

The importance of IGF-II and the insulin receptor in the regulation of fetal hepatic glycogen stores is demonstrated by in vivo and in vitro studies.

It has been more than 80 yr since the discovery of insulin (1), but until now the role of this hormone in fetal carbohydrate metabolism remains unclear. The fetus expresses insulin early in gestation; however, it is not normally secreted from the pancreas until just before birth (2). Because fetal glucose is mainly obtained from the mother, fetal insulin does not appear to be essential to maintain fetal euglycemia (2). The fetus begins to accumulate hepatic glycogen during the second half of gestation. These glycogen stores are important right after birth when the glucose supply from the mother is interrupted, the infant has not yet begun to suckle, and the newborn is suddenly in a fasting state. During this time, glucose must quickly be generated from endogenous fuel sources by breaking down hepatic glycogen stores and initiating the process of gluconeogenesis (3,4).

Some studies have shown that glucose use and fetal glycogen levels are not insulin dependent (2,5,6). It has also been demonstrated that some of the enzymes involved in fetal glycogen synthesis are not insulin dependent (6). Many studies, however, established the importance of insulin after birth. For example, mice carrying insulin 1 (Ins1) and insulin 2 (Ins2) gene deletions die a few days after birth due to acute complications of diabetes mellitus (7), and mice born with pancreatic agenesis due to a mutation in the pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1 gene (Pdx-1−/−) similarly die after birth (8,9). Likewise, mice with a complete disruption of the insulin receptor (Insr−/−) develop severe diabetes and die a few days after birth apparently from ketoacidosis (10,11). The phenotypes of both the insulin null and the Insr−/− mice are very similar, with the exception that the diabetes in insulin-deficient mice appears to be more severe than that of Insr−/− mice.

The fetal liver expresses high levels of IGF 2 (Igf2) during gestation (12,13). We previously reported that the absence of Igf2 gene expression (Igf2−/−) during the perinatal period is associated with a marked reduction in hepatic glycogen concentrations and higher mortality after fasting (4). Igf2−/− livers have not only lower hepatic glycogen stores but also lower glycogen synthase activity (4). Thus, it is possible that Igf2 might be a key anabolic hormone capable of regulating hepatic glycogen synthesis in the fetus. Igf2 mediates its biological effects via the type 1 IGF receptor (Igf1r) and the insulin receptor (14). These two receptors are highly homologous, especially in their tyrosine kinase domain and in the way their intracellular signaling is mediated (14). The Insr, however, consists of two isoforms that result from an alternative splicing of exon 11. The isoform A (IR-A) lacks exon 11, is thought to be mainly expressed in the fetus, and binds Igf2 with high affinity; the isoform B (IR-B), on the other hand, contains exon 11, is expressed mainly postnatally and has 10 times lower affinity for Igf2 than the IR-A isoform (15).

In this study, we wanted to determine whether the absence of insulin and/or other members of this family of genes had any effect on the regulation of hepatic glycogen in the fetus. We obtained livers from mice carrying Pdx-1, Insr, Igf2, and Igf1r (8,10,16,17) targeted deletions and determined their glycogen content and further examined the intracellular signaling that leads to fetal glycogen in the fetal liver. Defining the roles of insulin-like proteins and its effects on the fetal liver will further our understanding of factors involved in the regulation of fetal carbohydrate metabolism. Given that our studies show that Igf2 regulates fetal glycogen stores, it is possible that differences in Igf2 expression, which may vary in individual newborns, may result in different levels of glycogen synthesis and storage within the liver and therefore in differences in their ability to withstand fasting during the neonatal period. Thus, better understanding of the regulation and mechanisms involved in fetal carbohydrate metabolism may help us better understand the basis of normal and pathologic neonatal hepatic adaptations to extrauterine life.

Materials and Methods

Animals and tissue collection

Mice carrying the inactivated Pdx-1, Insr, Igf1r, and Igf2 genes (8,10,16,17) were maintained as separate colonies. Knockout and wild-type (WT) mice of each gene mutation were derived from the same progenitors, using heterozygous matings. Mice were maintained on a 12-h light, 12-h dark schedule and allowed free access to food and water. Six- to 8-wk-old females were housed with adult male mice and examined daily for vaginal plugs. The presence of a vaginal plug was designated d 0 of pregnancy. Tissue was collected between 1000 and 1200 h and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were stored at −80 C until used. The use of animals was approved by the Children’s Hospital Animal Care and Use Committee.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from tails or fetuses as described previously (18). PCR was used to determine the genotype of the Insr, Pdx-1, and Igf1r mutant mice, as previously described (19,20,21), and Southern blot hybridizations to determine whether mice contained the Igf2 knockout allele (18).

Glycogen determination

Glycogen concentration was measured in fetal hepatocytes as previously described (22). Briefly, hepatocytes were digested with in 0.05 m NaOH at 95 C for 30 min. The glycogen was precipitated with 1.1 volume 95% ethanol. The glycogen precipitates were dissolved in water and analyzed by the phenolsulfuric acid colorimetric method (22). To determine glycogen levels in hepatocytes, cells were lysed in 0.5 m NaOH and then treated with 30% KOH saturated with Na2SO4 as mentioned above. Protein concentration was determined using a protein assay reagent kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Hepatocyte culture

Igf2+/+ and Igf2−/− hepatocytes were isolated and cultured from fetuses as described previously (23) with some modifications. Briefly, fetuses were removed from their mothers on d 18 of gestation under sterile conditions. Livers were minced and incubated with collagenase, followed by deoxyribonuclease-1 in a 37 C shaking water bath. Cells were filtered through 150- and 62-nm nylon meshes, centrifuged at 4 C, and resuspended in NCTC 109 medium supplemented with 0.2% BSA, 20 mm HEPES, 0.008 μm insulin, 0.66 μm transferrin, 0.01 μm sodium selenite, 10−7 m dexamethasone, and 0.26 μm proline and gentamicin (23). Hepatocytes were plated at a density of 7.5 × 106/ml in six-well plates and incubated at 37 C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2-95% air. After 4 h in culture, media were changed to remove nonattached cells. Both Igf2+/+ and Igf2−/− hepatocytes were treated 48 h after plating and treated with 100 nm Igf2 (Gropep, Adelaide, Australia), vehicle, or 25 μm LY294008 (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA). Results shown are those obtained from Igf2−/− hepatocytes but similar results were obtained using Igf2+/+ hepatocytes.

Glycogen synthase activity assay

Glycogen synthase activity was measured as previously described (4,24). Briefly, hepatocytes were homogenized in nine volumes of chilled homogenization buffer [50 mm Tris, 100 mm NaF, 10 mm EDTA, 0.5% glycogen, and 5 mm dithiothreitol (pH 6.8)]. Twenty-five microliters of cell homogenate were be added to 50 μl of reaction mixture [50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mm EDTA, 1% glycogen, 15 mm Na2SO4, 1.5 mm uridine diphosphoglucose, and 14C-labeled UDPG (10,00–15,000 dpm/tube)]. The mixture was then incubated for 20 min and then passed through an anion-exchange resin column to isolate labeled glycogen. One unit of glycogen synthase activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that incorporates 1 μmol of substrate (UDPG) into product per minute at 30 C. Protein concentration was determined using a protein assay reagent kit (Pierce).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Hepatocytes were lysed in 2.69 mm Na4P2O7, 54.6 mm HEPES, 28.6 mm NaF, 360 mm NaCl, 4.8 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm vanadate, 10 μg/ml apoptotin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin. Protein extracts were incubated with anti-Insr and anti-insulin receptor substrate-2 (Irs-2) antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) in lysis buffer (500 μl) overnight at 4 C, followed by the addition of protein A-conjugated beads (50 μl) and 2 h incubation at 4 C. Beads containing bound antibodies were washed with lysis buffer and pelleted by centrifugation. Antibody-protein complexes were eluted with a sample buffer [300 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 50% glycerol, 100 μm dithiothreitol] at 95 C for 5 min. Immunoprecipitated proteins were electrophoresed on 8% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blotted with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (Cell Signaling) and with anti-INSR and anti-IRS-2 antibodies overnight at 4 C. After washing with Tris-buffered saline [0.1%Tween 20, 20 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl (pH7.4)] and incubated for 1 h with antigoat IgG horseradish peroxidase (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Phospho-Akt antibodies (Cell Signaling) were used to detect total levels of Akt phosphorylation. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Enhanced chemiluminescence-exposed films were digitalized and densitometric quantification of immunoactive bands was carried out using Image 1.6 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

IR-A and IR-B RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from embryonic day (e) 13, e15, e18, and adult mouse liver using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Approximately 100 mg of tissue were homogenized in 1 ml of Trizol using a motor-driven tissue homogenizer. RNA samples were treated with deoxyribonuclease (6.8 Kunitz units/sample; QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) to eliminate genomic DNA contamination and were purified using the RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was reverse transcribed using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Fifty nanograms RNA equivalent-cDNA were amplified for 35 cycles using the following primers, which were designed to discriminate the A and B forms of the two splice variants of mouse IR mRNA: IR sense, 5′-TTC AGG AAG ACC TTC GAG GAT TAC CTG CAC-3′; IR antisense, 5′-AGG CCA GAG ATG ACA AGT GAC TCC TTG TT-3′. Equivalence of the quantity and the quality was validated by PCR at 20 cycles using the following primers to target mouse rRNA as an internal control; 18S sense, 5′-AGT CCC TGC CCT TTG TAC ACA-3′, 18S antisense, 5′-CGA TCC GAG GGC CTC ACT A-3′. PCR product underwent electrophoresis on 3.0% agarose gel added with ethidium bromide, and the digital imaging and densitometric analysis was carried out using Kodak GEL LOGIC 100 imaging system and Kodak 1D version 3.6.1 software (Kodak Scientific Imaging Systems, New Haven, CT). After percentage of IR-A (or IR-B) was calculated as 100 × IR-A (or IR-B) density/(IR-A density + IR-B density) in each animal, mean values of percentage were compared between Igf2+/+ and Igf2−/− in each time point (e13, e15, e18, adult) using ANOVA. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using an unpaired nonparametric Student’s t test to determine differences between two groups. Data were also analyzed by a two-way ANOVA, followed by Fisher’s posttest using StatView 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) when comparing two different groups at different times in gestations. All data were expressed as the mean ± sem, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Lower hepatic glycogen concentrations are found in livers of Insr−/− and Igf2−/− fetuses but not those carrying Pdx-1 mutations

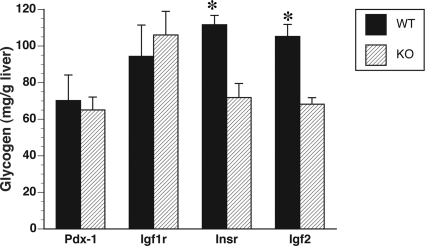

To determine whether insulin deficiency leads to any alteration in glycogen concentrations, we measured glycogen content in livers of insulin-deficient (Pdx-1−/−) fetuses and their WT littermates (Pdx-1+/+) on d 18 of gestation. It is during this time of gestation when peak glycogen levels are observed in the fetal liver in preparation for birth (4). Our data showed that the glycogen concentrations in Pdx-1−/− livers were similar to those of Pdx-1+/+ littermates (P = 0.75, Fig. 1), suggesting that insulin is not essential for glycogen synthesis to take place in the fetus. Hepatic glycogen concentrations in Insr−/− fetuses, on the other hand, were significantly lower than those of Insr+/+ controls (P < 0.01, Fig. 1). These results show that the insulin receptor promotes fetal glycogen synthesis, potentially via other insulin-like hormones. Consequently, we measured glycogen levels in livers from Igf2−/− fetuses and found that as in previous studies (4) they were significantly lower than Igf2+/+ controls (P < 0.01, Fig. 1). Because Igf2 mediates some of its functions via the Igf1r, we also measured glycogen levels in Igf1r−/− fetuses and their respective WT littermates and found no differences (P = 0.63, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Glycogen concentrations in livers of Pdx-1−/−, Igf1r−/−, Insr−/−, and Igf2−/− fetuses on d 18 of gestation expressed as a percentage of their respective WT controls (n = 3–5/genotype from three different litters). Notice that there are significant differences in glycogen levels in livers of Insr−/− and Insr+/+ fetuses and Igf2−/− and Igf2+/+ controls. Data are expressed as means ± sem. *, P < 0.001.

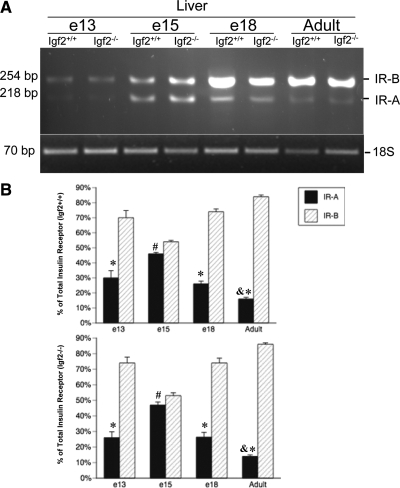

Insr expression in Igf2−/− and Igf2+/+ fetal livers

Because the Insr plays an important role in fetal glycogen synthesis before birth, we wanted to examine the expression of this receptor in the fetal liver. The IR is comprised of isoforms A and B (15). We examined the percentages of hepatic isoform IR-A vs. IR-B at different times on gestation in both WT and Igf2+/+ fetuses. Because the Igf2−/− has lower hepatic glycogen levels, we wanted to determine whether this was due to any differences in IR expression. As expected, IR-B was the predominant isoform in the adult liver (P < 0.01, Fig. 2). However, during fetal development both isoforms were expressed and this expression changed with time of gestation. On d 13 and 18 of gestation, the percentage of IR-A and IR-B expression was similar, with IR-B being the predominant isoform (P < 0.01). However, on d 15 of gestation, IR-B expression was not significantly higher but nearly alike that of IR-A expression. Thus, these results showed that IR-A is not the predominant Insr isoform in the fetal liver; however, percentages of IR-A expression were significantly higher in the fetal liver than in the adult (P < 0.01, Fig. 2). This pattern of expression was similar in both Igf2−/−and Igf2+/+ livers, suggesting that Igf2 deficiency does not affect the expression of these insulin receptor isoforms.

Figure 2.

Developmental expression of the IR-A and IR-B in livers from embryos collected on d 13, 15, and 18 of gestation and adult mice. A, Representative RT-PCR results from both Igf2−/− and Igf2+/+ livers (n = 3/genotype per age group). B, IR-A and IR-B values are expressed as percentage of total IR in both Igf2+/+ (top) and Igf2−/− (bottom) fetal livers. *, P < 0.01, differences between IR-A and IR-B percentages; #, P < 0.01, differences between IR-A percentage in e15 and e13, e18, and adult; &, P < 0.01, differences between adult IR-A percentage and fetal.

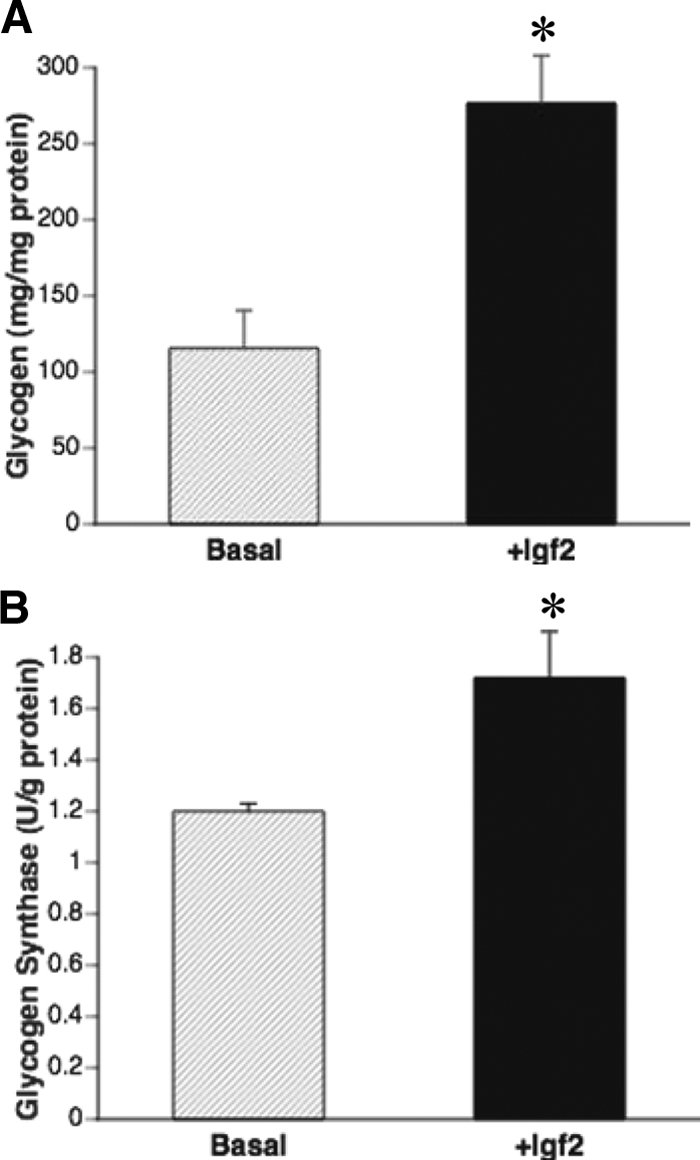

Igf2 stimulates glycogen synthesis and glycogen synthase activity in Igf2−/− primary fetal hepatocytes

Glycogen synthesis is carried out by the rate-limiting enzyme glycogen synthase (GS) and fetal hepatic glycogen accumulation parallels the increase in glycogen synthase activity (3). Because Igf2 is highly expressed in the fetal liver (12,13) and Igf2 deficiency leads to decreased levels of hepatic glycogen and glycogen synthase in the fetus (4), we wanted to determine the effect of this hormone in the regulation of GS synthesis in fetal hepatocytes. Our results show that Igf2 increases the activity of GS (P < 0.05, Fig. 3A) and glycogen concentrations (P < 0.05, Fig. 3B) in fetal hepatocytes compared with cells treated with just vehicle.

Figure 3.

Igf2 treatment significantly increases glycogen concentrations (A) and GS activity (B) in Igf2−/− fetal hepatocytes (black bars) when compared with those treated with only vehicle (hatched bars). Data are expressed as mean ± sem (n = 3–5/genotype). *, Significance (P < 0.01).

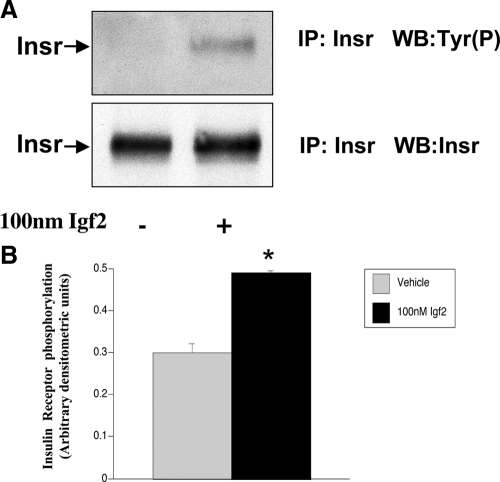

Igf2 increases IR phosphorylation

To determine whether the increase in glycogen synthesis induced by Igf2 in Igf2−/− hepatocytes was mediated via the IR, cells were treated with 100 nm Igf2 and the levels of IR phosphorylation were measured. Results show that Igf2 treatment significantly increased Insr phosphorylation (P = 0.01, Fig. 4), suggesting that Igf2 plays an important role in the activation of the IR in fetal liver cells.

Figure 4.

Igf2 significantly increases the levels of insulin receptor tyrosine phosphorylation [Tyr(P)] in fetal hepatocytes. A, Insr phosphorylation levels determined by immunoprecipitation. B, Densitometric quantification of bands was carried out using ImageJ software. Igf2−/− hepatocytes were cultured for 2 d and treated with 100 nm Igf2 or vehicle for 5 min. After hepatocytes were lysed, 600 μg of total protein were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Insr antibodies and analyzed by Western blot (WB) with antityrosine phosphate and Insr antibodies. Data shown are representative of three experiments (n = 3). Data are expressed as means ± sem. *, P < 0.01.

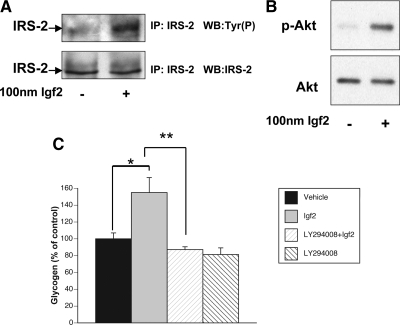

Igf2 induces the phosphorylation of Irs-2 and Akt phosphorylation in fetal hepatocytes

To determine the downstream molecular mechanism(s) by which Igf2 signals glycogen synthesis in the fetal liver, we analyzed changes in Irs-2 and Akt phosphorylation levels after Igf2 treatment. Because Irs-2 is known to play an important role in carbohydrate metabolism in adult mice (25), we investigated whether this was also the case in the fetus. When we treated fetal hepatocytes with Igf2 (100 nm), there was a significant increase in Irs-2 phosphorylation 15 min after treatment (P < 0.01, Fig. 5A). In addition, we found that phosphorylation of Akt also increased significantly after Igf2 treatment (P < 0.03, Fig. 5B), suggesting that one of the ways by which Igf2 may stimulate glycogen synthesis in the fetus is by increasing Akt activity. Because these proteins are part of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, we pretreated fetal hepatocytes with the PI3K inhibitor LY294008 for 1 h, followed by a vehicle or 100 nm Igf2 treatment. LY294008 had no effect on basal glycogen levels but inhibits Igf2 stimulated glycogen (P < 0.05, Fig. 5C), thus suggesting that Igf2 induces glycogen production via the PI3K pathway.

Figure 5.

Igf2 significantly increases Irs-2 (A) and Akt (B) phosphorylation (p-Akt) levels in fetal hepatocytes. IP, Immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot. C, LY294008, a PI3K inhibitor, blocks (**) the glycogenic effect of Igf2 (*) in fetal hepatocytes. Fetal hepatocytes from e18 Igf2−/− fetus were pretreated with 25 μm LY294008 for 1 h and then treated with either vehicle or 100 nm Igf2 for 16 h. Inhibitors remained in the media for the entire period of treatment. Data shown are representative of three experiments (n = 3). Data are expressed as means ± sem. * and **, P < 0.05.

Discussion

During late gestation, most mammals synthesize large quantities of glycogen and store it in tissues such as the liver and lung (3). Whereas glycogen in the lung is used as a substrate for surfactant synthesis, hepatic glycogen is used during the perinatal period to maintain levels of glycemia. As the newborn enters the extrauterine environment, many stresses are encountered, including a variable period of fasting before the initiation of suckling. It is known that glycogen reserves at birth last only a limited time if food is not supplied. In the rat, glycogen alone is sufficient to provide energy for 2–6 h after birth, whereas in humans, glycogen can provide energy for a maximum of 24 h (26). If hepatic glycogen stores are low at birth, as seen in some cases of intrauterine growth retardation, the newborn is in danger of hypoglycemia due to depletion of hepatic glycogen (5).

In this study, we analyzed different knockout strains to determine the role of insulin and other insulin-related proteins in the regulation of hepatic glycogen synthesis in the fetus. Our data suggest that the IR, but not insulin, plays an important role in hepatic glycogen synthesis in the fetus. We found that livers from insulin-deficient fetuses obtained via a global Pdx-1 mutation, an insulin transcription factor essential for normal pancreatic development, have glycogen stores similar to their WT littermates. Because insulin mediates glycogen synthesis postnatally, it is possible that another insulin-like peptide may take over this role before birth. An early study demonstrated the presence of a different form of insulin in the fetal circulation, capable of regulating fetal hepatic glycogenesis (27,28). This different insulin was perhaps an insulin-like protein such as Igf2, which has high homology to insulin, binds to the IR and is abundantly expressed in the fetal liver (12,13,14,29).

Although insulin deficiency does not appear to have an essential role in the formation of glycogen stores in the fetal liver, our data show that the ablation of the IR gene does. Livers from Insr−/− fetuses contained significantly lower glycogen stores than those of Insr+/+ fetuses. A possible ligand for the IR in the fetal liver is Igf2 because Igf2 deficiency also leads to lower hepatic glycogen stores and to lower GS activity (4). Igf2 is also known to bind the IR to stimulate cell proliferation (30). It has higher affinity to the IR-A isoform than to the IR-B (15). When we analyzed both IR-A and IR-B isoforms in the fetal liver, we found that the IR-B isoform was present in higher percentage than the IR-A isoform at the beginning and end of gestation. During late midgestation (e15), however, the percentages of the two isoforms were similar. The pattern of expression that we found suggests a specific function for these isoforms at different times in gestation. Because Igf2 has higher affinity for IR-A than for IR-B, but Igf2 is highly expressed in the fetal liver, it is possible that Igf2 may be working through both receptor isoforms by saturating them to mediate glycogen synthesis. No differences were found between Igf2+/+ and Igf2−/− with regard to isoform expression patterns, suggesting that the glycogen deficiency seen in the Igf2−/−fetus is not due to alterations in InsR isoform expression. Unlike the livers of Insr−/− fetuses, livers from Igf1r−/− have similar glycogen concentrations than those of Igf1r+/+ fetuses, suggesting that the Igf1r receptor does not play an essential role in fetal hepatic glycogen metabolism. This receptor, nonetheless, is involved in cell proliferation and growth during this time. Indeed, Igf1r−/− mice are born significantly smaller than their normal littermates (17).

Our in vitro studies show that treating fetal hepatocytes with Igf2 leads to both an increase in glycogen synthase activity and glycogen synthesis. These experiments provide direct evidence for the role of Igf2 in the regulation of glycogen synthesis in fetal hepatocytes. Although it is known that insulin can increase glycogen synthesis in rat fetal hepatocytes (31), we believe that Igf2 is likely to be the main glycogen mediator because it is highly expressed in the fetus, and in our studies we found that Igf2 but not insulin deficiency leads to lower hepatic glycogen stores. The activity of glycogen synthase is regulated by phosphorylation; whereas low levels of phosphorylation leads to higher activity, high levels decrease it (32). Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) phosphorylates and lowers GS activity (33). Akt, on the other hand, decreases GSK-3 activity via phosphorylation and enhances glycogen synthesis production (34). In our studies, we found that Igf2 increased Akt phosphorylation in fetal hepatocytes, suggesting that Akt activation may lead to GSK-3 inactivation and ultimately an increase in glycogen production. We also found that Igf2 induces Irs-2 phosphorylation, a key mediator of carbohydrate metabolism in insulin-sensitive tissues (35,36). Thus, our data suggest the possibility that Igf2, like insulin, may mediate some of its metabolic effects (or even proliferative effects) via Irs-2 in the fetal liver. Further studies using LY294008 blocked the glycogenic effect of Igf2 in fetal hepatocytes, thus supporting the involvement of the PI3K signaling pathway in hepatic glycogen synthesis in the fetus.

In summary, our in vivo studies indicate Igf2 and the Insr play an important role in fetal hepatic glycogen synthesis. Livers from Igf2−/− and Insr−/− fetuses have significantly lower glycogen stores compared with their respective WT controls. In addition, our in vitro studies show that Igf2 treatment to primary mouse fetal hepatocytes leads to phosphorylation of the IR and other intracellular signaling molecules, such as Irs-2 and Akt, and eventually to an increase in GS activity and glycogen synthesis. Thus, we propose Igf2 as the main regulator of glycogen metabolism in the fetal liver, the IR as its target receptor and PI3K as the main signaling pathway, leading to hepatic glycogen formation in the fetus. Better understanding of the regulation and mechanisms involved in fetal carbohydrate metabolism may help us better understand the basis of many neonatal hepatic adaptations and metabolic disorders.

Acknowledgments

Mice carrying the inactivated Igf2, Ig1r, insr, and Pdx-1 were kindly provided by Drs. Argiris Efstratiadis (through the courtesy of Dr. Lydia Villa-Komaroff), Domenico Accili, and Christopher V. E. Wright, respectively.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM071046 (to M.F.L.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online December 23, 2009

Abbreviations: e, Embryonic day; GS, glycogen synthase; GSK, GS kinase; IR, insulin receptor; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; WT, wild type.

References

- Simoni RD, Hill RL, Vaughan M 2002 The discovery of insulin: the work of Frederick Banting and Charles Best. J Biol Chem 277:31–32 [Google Scholar]

- Sperling M 1994 Carbohydrate metabolism: insulin and glucagons. In: Tulchinsky D, Little AB, eds. Maternal-fetal endocrinology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co.; 380–400 [Google Scholar]

- Margolis RN, Seminara D 1988 Glycogen metabolism in late gestation in fetuses of maternal diabetic rats. Biol Neonate 54:133–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MF, Dikkes P, Zurakowski D, Villa-Komaroff L, Majzoub J 1999 Regulation of hepatic glycogen in the insulin-like growth factor-deficient mouse. Endocrinology 140:1442–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon RK, Sperling MA 1991 Role of insulin in the fetus. Indian J Pediatr 58:21–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruppuso PA, Brautigan DL 1989 Induction of hepatic glycogenesis in the fetal rat. Am J Physiol 256:E49–E54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvillié B, Cordonnier N, Deltour L, Dandoy-Dron F, Itier JM, Monthioux E, Jami J, Joshi RL, Bucchini D 1997 Phenotypic alterations in insulin-deficient mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:5137–5140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offield MF, Jetton TL, Labosky PA, Ray M, Stein RW, Magnuson MA, Hogan BL, Wright CV 1996 PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development 122:983–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson J, Carlsson L, Edlund T, Edlund H 1994 Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature 371:606–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accili D, Drago J, Lee EJ, Johnson, MD, Cool MH, Salvatore P, Asico LD, Jose PA, Taylor SI, Westphal H 1996 Early neonatal death in mice homozygous for a null allele of the insulin receptor gene. Nat Genet 12:106–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi RL, Lamothe B, Cordonnier N, Mesbah K, Monthioux E, Jami J, Bucchini D 1996 Targeted disruption of the insulin receptor gene in the mouse results in neonatal lethality. EMBO J 15:1542–1547 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AL, Graham DE, Nissley SP, Hill DJ, Strain AJ, Rechler MM 1986 Developmental regulation of insulin-like growth factor II mRNA in different rat tissues. J Biol Chem 261:13144–13150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han VKM, Lund PK, Lee DC, D'Ercole AJ 1988 Expression of somatomedins/ insulin like growth factor mRNA in the human fetus: identification, characterization and tissue distribution. J Clin Endorinol Metab 66:422–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rother KI, Accili D 2000 Role of insulin receptors and Igf receptors in growth and development. Pediatr Nephrol 14:558–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca F, Pandini G, Scalia P, Sciacca L, Mineo R, Costantino A, Goldfine ID, Belfiore A, Vigneri R 1999 Insulin receptor isoform A, a newly recognized, high-affinity insulin-like growth factor II receptor in fetal and cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol 19:3278–3288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChiara TM, Efstratiadis A, Robertson EJ 1990 A growth deficiency phenotype in heterozygous mice carrying an insulin-like growth factor II gene disrupted by targeting. Nature 345:78–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JP, Baker J, Perkins AS, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A 1993 Mice carrying null mutations of genes encoding insulin-like growth factor I (Igf-1) and type 1 IGF receptor (Igf1r). Cell 75:59–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MF, Dikkes P, Zurakowski D, Villa-Komaroff L 1996 Insulin-like growth factor II affects the appearance and glycogen content of glycogen cells in the murine placenta. Endocrinology 137:2100–2108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cola G, Cool MH, Accili D 1997 Hypoglycemic effect of insulin-like growth factor-1 in mice lacking insulin receptors. J Clin Invest 99:2538–2544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner JA, Ye J, Schubert M, Burks DJ, Dow MA, Flint CL, Dutta S, Wright CV, Montminy MR, White MF 2002 Pdx1 restores β cell function in Irs2 knockout mice. J Clin Invest 109:1193–1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SL, Shaffer AL, Staudt LM, Amde S, Manney S, Terry C, Weisz K, Nissley P 2006 Transformation of late passage insulin-like growth factor-I receptor null mouse embryo fibroblasts by SV40 T antigen. Cancer Res 66:4233–4239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo S, Russell JC, Taylor AW 1970 Determination of glycogen in small tissue samples. J Appl Physiol 28:234–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Q, Levitsky LL, Fan J, Ciletti N, Mink K 1992 Glycogenesis in the cultured fetal and adult rat hepatocyte is differently regulated by medium glucose. Pediatr Res 32:714–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorburn A, Andrikopoulos S, Proietto J 1995 Defects in liver and muscle metabolism in neonatal and adult New Zealand obese mice. Metabolism 44:1298–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withers DJ, Gutierrez JS, Towery H, Burks DJ, Ren JM, Previs S, Zhang Y, Bernal D, Pons S, Shulman GI, Bonner-Weir S, White MF 1998 Disruption of IRS-2 causes type 2 diabetes in mice. Nature 391:900–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley HJ, Neligan GA 1966 Neonatal hypoglycemia. Br Med Bull 22:34–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix JM, Sutter-Dub MT, Legrele C 1975 Studies on the different forms of material reacting with antiinsulin antibodies in the fetal and adult rat. Horm Met Res 7:394–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattts C, Gain KR 1984 Insulin in the rat fetus. A new form of circulating insulin. Diabetes 33:50–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randhawa R, Cohen P 2005 The role of the insulin-like growth factor system in prenatal growth. Mol Genet Metab 86:84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrione A, Valentinis B, Xu SQ, Yumet G, Louvi A, Efstratiadis A, Baserga R 1997 Insulin-like growth factor II stimulates cell proliferation through the insulin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:3777–3782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menuelle P, Plas C 1993 Glycogenic effect of insulin, insulin-like growth factors II and I and association to their specific receptors in culture fetal rat hepatocytes. Endocrine 1:527–533 [Google Scholar]

- Pugazhenthi S, Khandelwal RL 1995 Regulation of glycogen synthase activation in isolated hepatocytes. Mol Cell Biochem 149–150:95–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Pandey SK 1998 Potential mechanism(s) involved in the regulation of glycogen synthesis by insulin. Mol Cell Biochem 182:135–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA 1995 Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 378:785–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previs SF, Withers DJ, Ren JM, White MF, Shulman GI 2000 Contrasting effects of IRS-1 versus IRS-2 gene disruption on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in vivo. J Biol Chem 275:38990–38994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde AM, Burks DJ, Fabregat I, Fisher TL, Carretero J, White MF, Benito M 2003 Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in IRS-2-deficient hepatocytes. Diabetes 52:2239–2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]