Abstract

The eukaryotic cell cycle comprises an ordered series of events, orchestrated by the activity of cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks), leading from chromosome replication during S-phase to their segregation in mitosis. The unidirectionality of cell cycle transitions is fundamental for successful completion of this cycle. It is thought that irrevocable proteolytic degradation of key cell cycle regulators makes cell cycle transitions irreversible, thereby enforcing directionality1-3. Here, we have experimentally examined the contribution of cyclin proteolysis to the irreversibility of mitotic exit, the transition from high mitotic Cdk activity back to low activity in G1. We show that forced cyclin destruction in mitotic budding yeast cells efficiently drives mitotic exit events. However, these remain reversible after termination of cyclin proteolysis, with recovery of the mitotic state and cyclin levels. Mitotic exit becomes irreversible only after longer periods of cyclin degradation, due to activation of a double-negative feedback loop involving the Cdk inhibitor Sic1 (refs 4,5). Quantitative modelling suggests that feedback is required to maintain low Cdk activity and to prevent cyclin resynthesis. Our findings demonstrate that unidirectionality of mitotic exit is not the consequence of proteolysis but of systems level feedback required to maintain the cell cycle in a new stable state.

After completion of chromosome segregation during mitosis, the activity of the key cell cycle kinase Cdk is downregulated to promote mitotic exit and return of cells to G1. This involves ubiquitin-mediated degradation of mitotic cyclins under control of the anaphase promoting complex (APC), a multi-subunit ubiquitin ligase. Mitotic cyclins are initially targeted for degradation by the APC in association with its activating subunit Cdc20 (APCCdc20). Later, declining Cdk levels and activation of the Cdk-counteracting phosphatase Cdc14 allow a second APC activator, Cdh1, to associate with the APC (APCCdh1)6-8. Cyclin proteolysis, a thermodynamically irreversible reaction, is thought to be responsible for the irreversibility of mitotic exit1-3. However, de novo protein synthesis can counteract degradation and constitutes a likewise thermodynamically irreversible process, driven by ATP hydrolysis. In a cellular setting, therefore, protein levels are defined by reversible changes to the rates of two individually irreversible reactions, protein synthesis and degradation. These considerations have led to the hypothesis that not proteolysis itself, but systems level feedback that affects synthesis and degradation rates, makes cell cycle transitions irreversible9.

To test this hypothesis, we investigated the contribution of cyclin proteolysis to the irreversibility of budding yeast mitotic exit (Fig. 1a). We arrested budding yeast cells in mitosis with high levels of mitotic cyclins by depleting Cdc20 under control of the MET3 promoter. In these cells, we induced Cdh1 expression from the galactose-inducible GALL promoter for 30 minutes. We expressed a Cdh1 variant, Cdh1(m11), that activates the APC even in the presence of high Cdk activity due to mutation of 11 Cdk phosphorylation sites6. This led to efficient degradation of the major budding yeast mitotic cyclin Clb2 (Fig. 1b). The mitotic Polo-like kinase, another APCCdh1 target10, was also efficiently degraded, while levels of the S-phase cyclin Clb5, a preferential substrate for APCCdc20 (ref. 11), remained largely unaffected (Supplementary Fig. 1). Clb2 destruction was accompanied by dephosphorylation of known mitotic Cdk substrates, seen by their change in electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 1b). These included three proteins whose dephosphorylation contributes to spindle elongation and chromosome segregation, Sli15, Ase1, and Ask1 (refs 12-14). Their dephosphorylation depended on the activity of the mitotic exit phosphatase Cdc14 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Mitotic spindles that were present in the metaphase arrested cells disassembled as Clb2 levels declined, accompanied by outgrowth of pronounced astral microtubules (Fig 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3), reminiscent of spindle breakdown at the end of mitosis. APCCdh1(m11)-mediated destruction of the spindle stabilising factor Ase1 (Fig. 1b), in addition to its dephosphorylation, may contribute to this phenotype15.

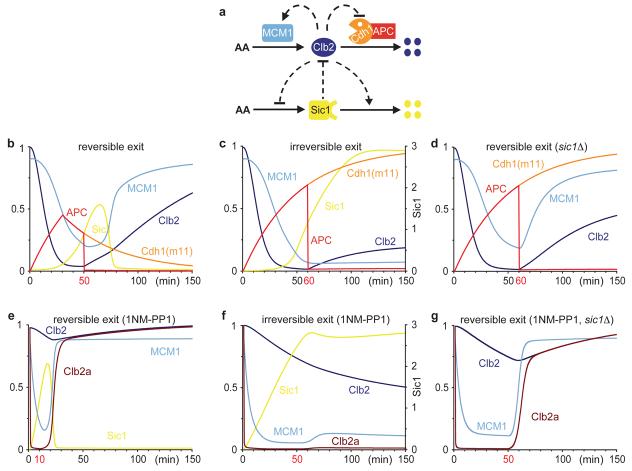

Figure 1. Clb2 destruction promotes reversible mitotic exit events.

a, Scheme depicting the experimental design and the predicted outcomes if cyclin proteolysis does, or does not, make mitotic exit irreversible. b, APCCdh1(m11)-driven Clb2 destruction is reversible and leads to reversible Cdk substrate dephosphorylation. Cdh1(m11) was induced in metaphase arrested cells for 30 minutes, and APCCdh1(m11) activity terminated after 50 minutes by inactivation of the cdc16-123 allele at 37°C. Cdh1(m11) was detected by Western blotting against its N-terminal HA epitope, Sli15, Ask1 and Ase1 were detected via C-terminal Pk6 epitopes. Tub1 served as a loading control. c, Clb2 degradation and re-accumulation are accompanied by spindle breakdown and re-assembly. As b, but cells were processed for indirect immunofluorescence to visualise the spindle pole body (SPB) component γ-tubulin (Tub4), mitotic spindles (tubulin) and nuclear DNA (stained with DAPI). Scale bar, 5 μm. d, FACS analysis of DNA content of the cells in c confirms their mitotic arrest throughout the timecourse.

After 50 minutes, when Clb2 levels became almost undetectable, we turned off APCCdh1(m11) by inactivating a temperature sensitive APC core subunit encoded by the cdc16-123 allele16. Strikingly, in response to APCcdc16-123 inactivation, Clb2 levels recovered and Sli15, Ase1, and Ask1 re-appeared in their mitotic hyperphosphorylated forms. Mitotic spindles formed again, suggesting that cells had re-entered a mitotic state. Spindles appeared morphologically intact, but were longer after cyclin re-accumulation (3.9±0.8 μm; mean ± s.d.) compared to metaphase spindles at the beginning of the experiment (2.1±0.6 μm). A likely reason for this lies in compromised sister chromatid cohesion after some, albeit inefficient, inactivation of the anaphase inhibitor securin by APCCdh1(m11) (Supplementary Fig. 4)17. FACS analysis of DNA content confirmed that cells maintained a 2c DNA content throughout the experiment (Fig. 1d). This demonstrates that cyclin destruction promotes mitotic exit events, but is not sufficient to render them irreversible. Cyclin re-synthesis can reverse mitotic exit. Note that reversibility of mitotic exit under these conditions did not depend on persistence of the S-phase cyclin Clb5 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

If not cyclin destruction, what makes mitotic exit irreversible? When we repeated the above experiment, but continued Cdh1(m11) induction and inactivated APCcdc16-123 only after 60 minutes, Clb2 did not re-accumulate and over half of the cells subsequently completed cytokinesis and entered G1 (Fig. 2a). This suggests that after longer times of Clb2 destruction mitotic exit becomes irreversible. Western blotting revealed that around the time when Clb2 loss turned irreversible, the Cdk inhibitor Sic1 accumulated4,5. We therefore asked whether Sic1 accumulation was responsible for the irreversibility of mitotic exit. When we repeated the above experiment using a sic1Δ strain, Clb2 re-appeared after APCcdc16-123 inactivation and only a minority of cells proceeded to cytokinesis (Fig. 2a). In the absence of Sic1, mitotic exit remained reversible even after prolonged Clb2 destruction for 90 minutes (Supplementary Fig. 5). Sic1 is part of a double-negative feedback loop in which Cdk downregulation allows the Cdc14 phosphatase to dephosphorylate Sic1, as well as its transcription factor Swi5, to increase expression and stability of the Cdk inhibitor5,9. As Clb2 positively regulates its own synthesis18,19, Clb2 inhibition by Sic1 may be required to prevent Clb2 re-synthesis.

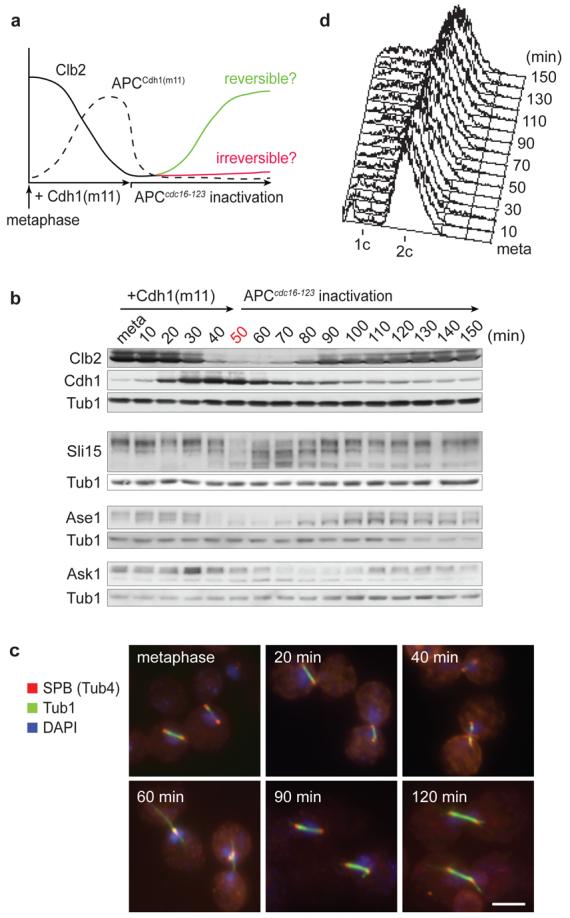

Figure 2. Irreversibility of mitotic exit requires feedback loop activation.

a, Irreversible mitotic exit after longer periods of APCCdh1(m11) activity depends on Sic1. As Fig. 1, but Cdh1(m11) expression was not terminated and cdc16-123 was inactivated after 60 minutes. Mating pheromone α-factor (5 μg/ml) was added to prevent progression through the next cell cycle. FACS analysis of DNA content reveals completion of cytokinesis in cells containing Sic1. b-c, Limited activation of feedback loop components during reversible mitotic exit. b, Swi5 retains cytoplasmic localisation and c, Sic1 accumulation is incomplete during reversible APCCdh1(m11)-driven mitotic exit. For comparison, cells were released from metaphase arrest into synchronous mitotic exit by Cdc20 re-induction. Swi5 was visualised by indirect immunofluorescence. Levels of Clb2 and Sic1 were analysed by Western blotting. Scale bar, 5 μm.

The above suggests that mitotic exit remained reversible up to 50 minutes because the Sic1 feedback loop had not yet been sufficiently activated. Consistent with this possibility, dephosphorylation-dependent translocation of Swi5 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, indicative of Swi5 activation during mitotic exit5,20, was inefficient under these conditions (Fig. 2b). Likewise, the levels of Sic1 that became detectable remained below those observed in cells undergoing mitotic exit after release from the metaphase block by re-induction of Cdc20 (Fig. 2c). If irreversibility of mitotic exit is due to activation of the Sic1-dependent feedback loop, irreversibility should be advanced by increasing Cdc14 phosphatase activity, or by directly enhancing Sic1 levels. As predicted, ectopic expression of either Cdc14, or of a version of Sic1 that is stable in the presence of high Cdk activity due to mutation of 3 Cdk phosphorylation sites21, Sic1(m3), made Clb2 destruction irreversible under conditions that otherwise permit Clb2 re-synthesis (Fig. 3a). This confirms that activation of the Sic1-dependent feedback loop limits the irreversibility of mitotic exit.

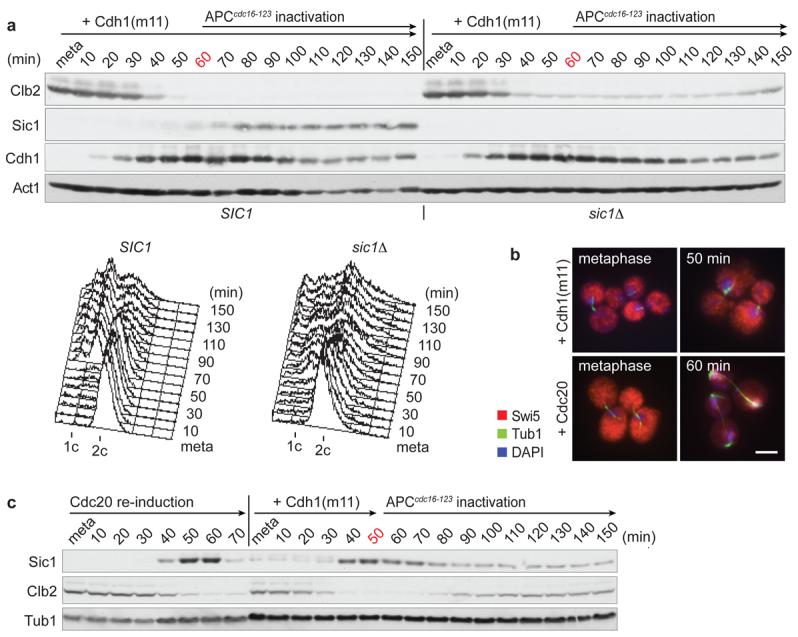

Figure 3. Sic1 turns mitotic exit irreversible.

a, Ectopic expression of Cdc14 or Sic1(m3) advances irreversibility of mitotic exit. Cdh1(m11) was expressed without or together with Cdc14 or Sic1(m3) for 30 minutes, before APCcdc16-123 was inactivated after 50 minutes. α-factor was added as in Fig. 2a. b, Sic1 promotes irreversible mitotic exit in the absence of APC activity after chemical Cdk inhibition. Cdk (cdc28-as1) was inhibited by addition of 5 μM 1NM-PP1 in metaphase arrested SIC1 and sic1Δ cells, depleted for Cdc20 and APCcdc16-123 inactivated at 37°C. After 10 or 50 minutes, 1NM-PP1 was washed out while APCcdc16-123 remained inactive. Levels and gel mobility of the indicated proteins were analysed by Western blotting. Tub1 or Act1 served as loading controls.

It has been shown that mammalian mitotic exit can be driven in the absence of cyclin proteolysis by chemical inhibition of Cdk activity. After short, but not after longer times of Cdk inhibition, mitotic exit remained reversible3. We repeated these experiments in budding yeast cells carrying the ATP analog (1NM-PP1)-sensitive Cdk allele cdc28-as1 (ref. 22). As in mammalian cells, we observed reversible mitotic exit events, exemplified by dephosphorylation of the Cdk substrate Orc6 (ref. 23), after transient Cdk inhibition for 10 minutes. After 50 minutes of inhibitor treatment, Orc6 dephosphorylation turned irreversible. Irreversibility again correlated with, and depended on, accumulation of Sic1 (Figure 3b). This suggests that feedback loop activation is responsible, and that cyclin destruction is not required, for irreversible mitotic exit. In the presence of cyclin destruction, a shorter period of Cdk inhibition was sufficient to render mammalian mitotic exit irreversible3. While this was taken to demonstrate a requirement for cyclin destruction, we suggest that activation of a feedback loop correlated with cyclin destruction that made mitotic exit irreversible.

To theoretically investigate the contribution of feedback to the irreversibility of budding yeast mitotic exit, we used a mathematical model24 to describe the cell cycle control network that operates during mitotic exit (Fig. 4a, a detailed description is found in Supplementary Fig. 6). In our experiments, Cdk downregulation begins by Cdh1(m11)-mediated Clb2 degradation, or 1NM-PP1 addition, which causes Sic1 accumulation due to the double-negative feedback loops. If Clb2 proteolysis is terminated by inactivating APCcdc16-123, or 1NM-PP1 is removed, before Sic1 reaches a threshold, Sic1 accumulation becomes transient and Cdk activity will recover (Fig.4b,e). In the absence of Sic1, mitotic exit will therefore always remain reversible (Fig. 4d,g). Clb2 destruction becomes irreversible only if Sic1 levels have reached a threshold that maintains Cdk activity low enough to prevent Clb2 re-synthesis (Fig. 4c). Mitotic exit after chemical Cdk inhibition turns irreversible when Sic1 levels are sufficient to maintain Cdk inhibition independently of 1NM-PP1 (Fig. 4f). Note that during normal mitotic exit, Cdk downregulation is initiated by APCCdc20-mediated Clb2 destruction, and APCCdh1 activation by the decreasing Cdk/Cdc14 ratio forms an additional double-negative feedback loop that maintains low Cdk activity redundantly with Sic1. In mammalian cells, the antagonistic relationship between Cdk and Cdh1, and between Cdk and its inhibitory tyrosine phosphorylation25,26, create double-negative feedback loops of Cdk inactivation that likely contribute to irreversibility of mitotic exit.

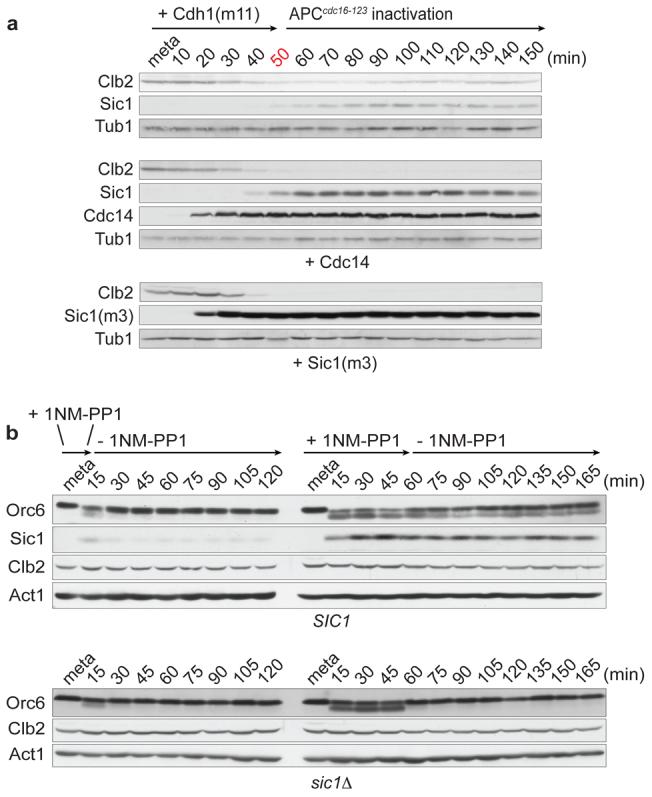

Figure 4. Computational analysis of mitotic exit.

a, Wiring diagram for Clb2/Cdk (abbreviated Clb2) and Sic1 regulation during budding yeast mitotic exit. AA, amino acids. b-d, Numerical simulations of protein levels and activities with a mathematical model (see Supplementary Fig. 6) during Cdh1(m11)-induced mitotic exit and e-g, after chemical Cdk inhibition. Clb2 represents the total level of Clb2/Cdk complexes, including inactive complexes bound to Sic1, Clb2a its associated kinase activity, MCM1 the active form of the Clb2 transcription factor complex Fkh2/Ndd1/Mcm1, APC the level of active APCCdh1(m11). b,e, Reversible exit: APCCdh1(m11) activity is terminated after 50 minutes, or Cdk inhibition by 1NM-PP1 released after 10 minutes. c,f, Irreversible exit: APCCdh1(m11) activity continues for 60 minutes, or Cdk inhibition for 50 minutes. d,g, Reversible exit in sic1Δ cells: as c,f, but Sic1 synthesis is zero.

Protein destruction is a commonly used mechanism controlling key cell cycle transitions. The rise in Cdk activity at the G1/S transition is accompanied by the degradation of Cdk inhibitors. The irreversibility of this transition, however, probably stems from positive feedback during Cdk activation27. Likewise, even though the G2/M transition in the vertebrate cell cycle involves proteolysis of the Cdk inhibitory kinase Wee1, this transition shows the characteristics of a bistable switch, driven by feedback between Cdk, Wee1 and the Cdk-activating phosphatase Cdc25 (refs 28,29). While not irreversible in a cellular context, protein degradation, and in particular protein resynthesis, occur at a time scale slower than addition or removal of posttranslational modifications. Proteolysis thereby introduces an element of distinct dynamic nature into the cell cycle control network, the consequences of which merit further investigation.

Methods summary

Yeast strains

A list of strains used in this study is found in Supplementary Table 1. Epitope tagging of endogenous genes and gene deletions were performed by gene targeting using polymerase chain reaction products. Integrative expression vectors for Cdh1(m11) and Cdc14 under control of the GALL and GAL1 promoters, respectively, were as described6,13, the YIplac211GAL1-SIC1(m3)-HA vector was a gift from E. Schwob.

Experimental procedures

Cells were grown at 25°C in SC medium lacking methionine, with 2% raffinose as carbon source, and arrested in metaphase by depletion of Cdc20 under control of the MET3 promoter by addition of 2 mM methionine for 5 hours. Expression of Cdh1(m11), Sic1(m3) or Cdc14 was induced by addition of 2% galactose. Induction was terminated by addition of 2% glucose, and APCcdc16-123 inactivated by shifting the culture to a waterbath at 37°C. Alternatively, metaphase arrested cells were released into synchronous mitotic progression by Cdc20 re-induction after filtration and resuspension in methionine-free medium. Protein extracts were prepared using the TCA method30. Antibodies used for Western blotting and immunostaining were: α-HA 12CA5, α-myc 9E10, α-Orc6 SB49 (a gift from B. Stillman), α-Clb2 (y-180), α-Clb5 (yN-19), and α-Sic1 antisera (FL-284, all Santa Cruz Biotechnology), α-Tub1 YOL1/34 (Serotec), α-actin N350 (Amersham), α-Tub4 serum (a gift from J. Kilmartin), and an antiserum raised against recombinant Cdc14 purified after overexpression in E. coli.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Bouchoux, J. Kilmartin, E. Schwob and W. Zachariae for antibodies and constructs, and members of our laboratory for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a European Commission Marie Curie Individual Fellowship to S.L.-A. and the EC FP7 (O.K.).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on www.nature.com/nature.

Reprints and permissions information is available at npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions.

References

- 1.King RW, Deshaies RJ, Peters J-M, Kirschner MW. How proteolysis drives the cell cycle. Science. 1996;274:1652–1659. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reed SI. Ratchets and clocks: the cell cycle, ubiquitylation and protein turnover. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:855–864. doi: 10.1038/nrm1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potapova TA, et al. The reversibility of mitotic exit in vertebrate cells. Nature. 2006;440:954–958. doi: 10.1038/nature04652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donovan JD, Toyn JH, Johnson AL, Johnston LH. P40SDB25, a putative CDK inhibitor, has a role in the M/G1 transition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1640–1653. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.14.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visintin R, et al. The phosphatase Cdc14 triggers mitotic exit by reversal of Cdk-dependent phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:709–718. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zachariae W, Schwab M, Nasmyth K, Seufert W. Control of cyclin ubiquitination by CDK-regulated binding of Hct1 to the anaphase promoting complex. Science. 1998;282:1721–1724. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaspersen SL, Charles JF, Morgan DO. Inhibitory phosphorylation of the APC regulator Hct1 is controlled by the kinase Cdc28 and the phosphatase Cdc14. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeong FM, Lim HH, Padmashree CG, Surana U. Exit from mitosis in budding yeast: Biphasic inactivation of the Cdc28-Clb2 mitotic kinase and the role of Cdc20. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:501–511. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novak B, Tyson JJ, Gyorffy B, Csikasz-Nagy A. Irreversible cell-cycle transitions are due to systems-level feedback. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:724–728. doi: 10.1038/ncb0707-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shirayama M, Zachariae W, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K. The Polo-like kinase Cdc5p and the WD-repeat protein Cdc20p/fizzy are regulators and substrates of the anaphase promoting complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1998;17:1336–1349. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirayama M, Toth A, Galova M, Nasmyth K. APCCdc20 promotes exit from mitosis by destroying the anaphase inhibitor Pds1 and cyclin Clb5. Nature. 1999;402:203–207. doi: 10.1038/46080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira G, Schiebel E. Separase regulates INCENP-Aurora B anaphase spindle function through Cdc14. Science. 2003;302:2120–2124. doi: 10.1126/science.1091936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higuchi T, Uhlmann F. Stabilization of microtubule dynamics at anaphase onset promotes chromosome segregation. Nature. 2005;433:171–176. doi: 10.1038/nature03240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khmelinskii A, Lawrence C, Roostalu J, Schiebel E. Cdc14-regulated midzone assembly controls anaphase B. J. Cell Biol. 2007;177:981–993. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juang Y-L, et al. APC-mediated proteolysis of Ase1 and the morphogenesis of the mitotic spindle. Science. 1997;275:1311–1314. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irniger S, Piatti S, Michaelis C, Nasmyth K. Genes involved in sister chromatid separation are needed for B-type cyclin proteolysis in budding yeast. Cell. 1995;81:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwab M, Neutzner M, Möcker D, Seufert W. Yeast Hct1 recognizes the mitotic cyclin Clb2 and other substrates of the ubiquitin ligase APC. EMBO J. 2001;20:5165–5175. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds D, et al. Recruitment of Thr 319-phosphorylated Ndd1p to the FHA domain of Fkh2p requires Clb kinase activity: a mechanism for CLB cluster gene activation. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1789–1802. doi: 10.1101/gad.1074103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pic-Taylor A, Darieva Z, Morgan BA, Sharrocks AD. Regulation of cell cycle-specific gene expression through cyclin-dependent kinase-mediated phosphorylation of the forkhead transcription factor Fkh2p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:10036–10046. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.10036-10046.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moll T, Tebb G, Surana U, Robitsch H, Nasmyth K. The role of phosphorylation and the CDC28 protein kinase in cell cycle-regulated nuclear import of the S. cerevisiae transcription factor SWI5. Cell. 1991;66:743–758. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90118-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verma R, et al. Phosphoregulation of Sic1p by G1 Cdk required for its degradation and entry into S phase. Science. 1997;278:455–460. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bishop AC, et al. A chemical switch for inhibitor-sensitive alleles of any protein kinase. Nature. 2000;407:395–401. doi: 10.1038/35030148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen VQ, Co C, Li JJ. Cyclin-dependent kinases prevent DNA re-replication through multiple mechanisms. Nature. 2001;411:1068–1073. doi: 10.1038/35082600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Queralt E, Lehane C, Novak B, Uhlmann F. Downregulation of PP2ACdc55 phosphatase by separase initiates mitotic exit in budding yeast. Cell. 2006;125:719–732. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kramer ER, Scheuringer N, Podtelejnikov AV, Mann M, Peters J-M. Mitotic regulation of the APC activator proteins CDC20 and CDH1. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:1555–1569. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pomerening JR, Ubersax JA, Ferrell JE. Rapid cycling and precocious termination of G1 phase in cells expressing CDK1AF. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:3426–3441. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cross FR, Archambault V, Miller M, Kolvstad M. Testing a mathematical model of the yeast cell cycle. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:52–70. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novak B, Tyson JJ. Numerical analysis of a comprehensive model of M-phase control in Xenopus oocyte extracts and intact embryos. J. Cell Sci. 1993;106:1153–1168. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.4.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pomerening JR, Sontag ED, Ferrell JE., Jr. Building a cell cycle oscillator: hysteresis and bistability in the activation of Cdc2. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:346–351. doi: 10.1038/ncb954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foiani M, Marini F, Gamba D, Lucchini G, Plevani P. The B subunit of the DNA polymerase α-primase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae executes an essential function at the initial stage of DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:923–933. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.