Abstract

Agarases are the enzymes which catalyze the hydrolysis of agar. They are classified into α-agarase (E.C. 3.2.1.158) and β-agarase (E.C. 3.2.1.81) according to the cleavage pattern. Several agarases have been isolated from different genera of bacteria found in seawater and marine sediments, as well as engineered microorganisms. Agarases have wide applications in food industry, cosmetics, and medical fields because they produce oligosaccharides with remarkable activities. They are also used as a tool enzyme for biological, physiological, and cytological studies. The paper reviews the category, source, purification method, major characteristics, and application fields of these native and gene cloned agarases in the past, present, and future.

Keywords: agar, agarase, GH-16 family, GH-50 family, oligosaccharides

1. Introduction

Agarases catalyze the hydrolysis of agar. They are classified into α-agarase (E.C. 3.2.1.158) and β-agarase (E.C. 3.2.1.81) according to the cleavage pattern. The basic structure of agar is composed of repetitive units of β-d-galactose and 3,6-anhydro-α-l-galactose [1]. α-Agarases cleave α-1,3 linkages to produce agarooligosaccharides of series related to agarobiose [2], while β-agarases cleave β-1,4 linkages to produce neoagarooligosaccharides of series related to neoagarobiose [3]. So far, several agarases have been isolated from different genera of bacteria found in seawater, marine sediments and other environments. Agarases have a wide variety of applications. They have been used to hydrolyze agar to produce oligosaccharides, which exhibit important physiological and biological activities beneficial to the health of human being [4]. Besides that, agarases also have other uses as tools to isolate protoplasts from seaweeds [5] and to recover DNA from agarose gel [6], and to investigate the composition and structure of cell wall polysaccharide of seaweeds. Recent progress in cloning and sequencing of these enzymes has led to structure-function analyses of agarase [7–10]. This information will provide valuable insights into the use of this enzyme.

2. Agar

In Japan, agar has been used as a food since several hundred years. From Japan its use extended to other oriental countries during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Nowadays, agar has a wide variety of uses due to its stabilizing and gelling characteristics [11]. Agar has been mainly used in microbiological media because it is not easy for microorganisms to metabolize as well as forms clear, stable and firm gels. It is a Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) food additive, which is used in icings, glazes, processed cheese, jelly sweets, and marshmallows.

2.1. Sources of Agar

Agar is a phycocolloid extracted from the cell wall of a group of red algae (Rhodophyceae) including Gelidium and Gracilaria. Gelidium is the preferred source for agar production, but its cultivation is difficult and its natural resource is not abundant like Gracilaria, which is being cultivated in several countries and regions in commercial scale. Thus Gracilaria became an important source for agar production because it is easily harvested and cultivated [12].

2.2. Structures of Agar

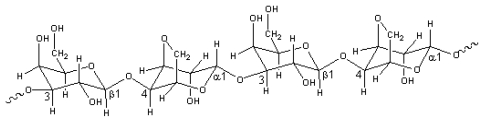

Araki showed that agar was formed by a mixture of two polysaccharides named agarose and agaropectin [1]. The main structure of agarose is composed of repetitive units of β-d-galactose and 3,6-anhydro-α-l-galactose (3,6-AG), with few variations, and a low content of sulfate esters (Figure 1). Agaropectin has the same basic disaccharide-repeating units as agarose with some hydroxyl groups of 3,6-anhydro-α-l-galactose residues replacing by sulfoxy or methoxy and pyryvate residues [13].

Figure 1.

Structure of agarose.

Agarose has a high molecular mass above 100,000 Daltons, with a low sulfate content of below 0.15%. Agaropectin has a lower molecular mass below 20,000 Daltons, with a much higher sulfate content of 5% to 8% [14]. Agar is a mixture of agarose and agaropectin fractions in variable proportions depending on the original raw material. The concentration of agaropectin is higher in Gracilaria, followed by Porphyra, and Gelidium [15] (see [11] for a more detailed review of agar).

3. Agarases

3.1. Sources of Agarases

Agarases have been isolated from many sources, including seawater, marine sediments, marine algae, marine mollusks, fresh water, and soil (see Table 1 for a complete listing and references). Agarase activity has been found in seawater from Sagami Bay in Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan [6], the Bay of San Vicente in Chile [16], North Wales in UK [17], and Mediterranean Sea in France [2]. Agarase activity has been reported in extract of marine sediment collected at Ise Bay in Japan [18], at Noma Point in Japan at a depth of 230 m [19], and from the Xiamen coast in the East China Sea [20]. Because agarases are the enzymes that hydrolyzes agar, they have been isolated from the surface of rotted red algae in the South China Sea coast in Hainan Island [21], decomposing algae in Niebla in Chile [22] and in Halifax in Canada [23], and decomposing Porphyra in Japan [24]. Some marine mollusks live on seaweed, thus the microorganisms in their digestive tract produce carbohydrate hydrolases, such as agarases. Agarase activity has been detected in the gut of a turban shell Turbinidae batillus cornutus in Kangnung coast in the East Sea of Korea [25]. Most of agarases exist in the marine environment; however, some of them come from fresh water and soil. Agarases have been isolated from the IJsselmeer Lake in Netherlands [26], and soil samples from Gifu in Japan [27], Kanto area in Japan [3], and Karnataka in India [28].

Table 1.

Agarase from marine bacteria: localization, characteristics, and products.

| Source | Localization | Category (α/β agarase) | Mr(kDa) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Optimal T (°C) | Stable up to T (°C) | Optimal pH | Stable pH | Product | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea water | ||||||||||

| Vibrio sp. JT0107 | extracellular | β | 107 | 6.3 | 30 | 40 | 8.0 | - | NA2, NA4 | [6] |

| Alteromonas sp. C-1 | extracellular | β | 52 | 234 | 30 | 30 | 6.5 | - | NA4 | [16] |

| Cytophaga sp. | extracellular | β | - | - | 40 | - | 7.2 | - | - | [17] |

| Alteromonas agarlyticus GJ1B | extracellular | α | 180 (SDS-PAGE) 360 (gel filtration) |

- | - | 45 | 7.2 | >6.5 | A4 | [2] |

| Marine sediment | ||||||||||

| Vibrio sp. PO-303 | extracellular | β | 87.5 115 57 |

7.54 28.4 20.8 |

38–55 | - | 6.5–7.5 | - | NA4, NA6 NA2 - |

[18] |

| Thalassomonas sp. JAMB-A33 | intracellular | α | 85 | 40.7 | 45 | 40 | 8.5 | 6–11 | A2, A4 (main), A6 | [19] |

| Agarivorans sp. HZ105 | extracellular | β | 58 54 |

76.8 57.45 |

- | 25 | 6.0–9.0 | - | - | [20] |

| Marine algae | ||||||||||

| Alteromonas sp. SY37-12 | extracellular | β | 39.5 | 83.5 | 35 | 50 | 7.0 | - | NA4, NA6 (main), NA8 | [21] |

| Pseudoalteromonas antarctica N-1 | extracellular | β | 33 | 292 | - | 30 | 7 | - | NA4, NA6 | [22] |

| Pseudomonas atlantica | intracellular | β | 32 | - | - | 30 | 7.0 | 6.5–7.5 | NA2 | [23] |

| Vibrio sp. AP-2 | extracellular | β | 20 | - | - | 45 | 5.5 | 4.0–9.0 | NA2 | [24] |

| Marine mollusks | ||||||||||

| Agarivorans albus YKW-34 | extracellular | β | 50 | 25.54 | 40 | 50 | 8.0 | 6.0–9.0 | NA2 (main), NA4 | [25] |

| Fresh water | ||||||||||

| Cytophaga flevensis | extracellular | β | 26 | - | 35 | 40 | 6.3 | 6.0–9.0 | NA2, NA4, NA6…NA16 | [26] |

| Soil | ||||||||||

| Bacillus sp. MK03 | extracellular | β | 92 (SDS-PAGE) 113 (gel filtration) |

14.2 | 40 | 35 | 7.6 | 7.1–8.2 | NA2, NA4(main) | [27] |

| Alteromonas sp. E-l | intracellular | β | 82 (SDS-PAGE) 180(gel filtration) |

34 | 40 | 40 | 7.5 | 7–9 | NA2 | [3] |

| Acinetobacter sp. AGLSL-1 | extracellular | β | 100 | 397 | 40 | 45 | 6.0 | 5.0–9.0 | NA2 | [31] |

| Unknown | ||||||||||

| Pseudomonas-like bacteria | extracellular | β | 210 63 |

- | 38 43 |

- - |

6.7 6.7 |

- - |

NA2, NA4, NA6 NA4 |

[29] |

| Pseudomonas atlantica | intracellular | β | - | - | - | - | - | - | NA4, NA6, NA8, NA10 | [30] |

Agarase activity has been reported in a wide range of microorganisms isolated from the above environments, including Alteromonas sp. [2,3,16,21], Pseudomonas sp. [23,29,30], Vibrio sp. [6,18,24], Cytophaga sp. [17,26], Agarivorans sp. [20,25], Thalassomonas sp. [19], Pseudoalteromonas sp. [22], Bacillus sp. [27], and Acinetobacter sp. [31], etc. All of the microorganisms are gram negative bacteria. Most agarases are produced extracellularly (see Table 1), except a few agarases are produced intracellularly [3,19,23,30].

3.2. Cleavage Pattern

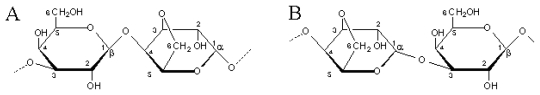

Agarases are characterized as α-agarases and β-agarases according to the cleavage pattern. The basic units of the products of α-agarases and β-agarases are agarobiose (Figure 2A) [2] and neoagarobiose (Figure 2B), respectively [3]. Identified β-agarases are more abundant than α-agarases in both the database (http://www.cazy.org/fam/acc_GH.html) and published reports. There are only two α-agarases described in the above database and literatures, i.e., agarases produced by Alteromonas agarlyticus GJ1B from seawater [2] and Thalassomonas sp. JAMB-A33 from marine sediment [19].

Figure 2.

Structure of agarobiose (A) and neoagarobiose (B).

3.3. Families of Agarase

Two α-agarases produced by Thalassomonas sp. JAMB-A33 and Alteromonas agarlyticus GJ1B belong to the glycoside hydrolase (GH) family 96 (http://www.cazy.org/fam/acc_GH.html). The amino acid sequences of the two α-agarases have been identified, with GeneBank accession number of BAF44076.1 (JAMB-A33) and AAF26838.1 (GJ1B), respectively. However, there is no publication available on the catalytic domain in α-agarase. The two α-agarases feature a type-VI cellulose-binding domain by the alignment of amino acid sequence in the NCBI protein database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/6724084?report=genpept).

Amino acid sequence similarity indicates that catalytic domains of β-agarases reported up to date have been mainly classified into three GH families, i.e., GH-16, GH-50, and GH-86 (http://www.cazy.org/fam/acc_GH.html). GH-16 family has most abundant members, including agarase, carrageenase, glucanase, galactosidase, laminarinase, etc., while agarase is the only member of GH-50 and GH-86 families. On the other hand, most β-agarases belong to GH-16 family, while only a few β-agarases belong to GH-50 and GH-86 families (see Table 2 for a complete listing and references). Agarases from these three families carry conserved glycoside hydrolase modules that function in catalysis, and some also carry carbohydrate binding modules (CBM) [32,34].

Table 2.

Recombinant agarases from engineered microorganisms: localization, characteristics, products, and accession number.

| Source | Expression strain | Name of the gene | Localization | Production |

GH Family | Mr (kDa) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Optimal T (°C) | Stable up to T (°C) | Optimal pH | Stable pH | Product | GeneBank accession number | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (U/L) | (mg/L) | ||||||||||||||

| β-agarase | |||||||||||||||

| Pseudomonas sp. W7 |

Escherichia coli JM83 |

- | extracellular | - | 16 | 59 | - | 20–40 | - | 7.8 | - | NA4 | AAF82611 | [39] | |

| Vibrio sp. PO-303 |

Escherichia coli BL21 |

agaA | intracellular | - | 16 | 106 | 16.4 | 40 | - | 7.5 | - | NA4, NA6 | BAF62129 | [7] | |

| Vibrio sp. PO-303 |

Escherichia coli DH5α |

agaD | intracellular | 620 | 10 | 16 | 51 | 63.6 | 40 | 45 | 7.5 | 4–9 | NA4(main), NA2, NA6 | BAF34350 | [40] |

| Vibrio sp. PO-303 |

Escherichia coli BL21 |

agaC | intracellular | 7130 | 22 | 86 | 51 | 329 | 35 | 37 | 6.0 | 4–8 | NA4, NA6, NA8(main) | BAF03590 | [47] |

| Agarivorans sp. JA-1 |

Escherichia coli DH5α |

- | intracellular | 554 | 3 | 50 | 109 | 167 | 40 | 60 (70%) | 8.0 | - | NA2, NA4 | ABK97391 | [42] |

| Saccharophagus degradans 2–40 |

Escherichia coli EPI300 |

aga50A | intracellular | - | 50 | 87 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ABD80438 | [34] | |

| aga16B | 16 | 64 | ABD80437 | ||||||||||||

| aga86C | 86 | 86 | ABD81910 | ||||||||||||

| Aga50D | 50 | 89 | ABD81904 | ||||||||||||

| aga86E | 86 | 146 | ABD81915 | ||||||||||||

| Microbulbifer-like JAMB-A94 | Bacillus subtilis | agaO | extracellular | 7816 | 80 | 86 | 127 | 98 | 45 | 40 | 7.5 | 6–9 | NA6 (main) | BAD86832 | [35] |

| Zobellia galactanivorans |

Escherichia coli DH5α |

agaA | intracellular | 160 | 1 | 16 | 60 | 160 | - | - | - | - | NA4, NA6 | AAF21820 | [43] |

| agaB | 800 | 8 | 31 | 100 | NA2, NA4 | AAF21821 | |||||||||

| Agarivorans sp. JAMB-A11 | Bacillus subtilis | agaA11 | extracellular | 19000 | 51 | 50 | 105 | 371 | 40 | 40 | 7.5–8.0 | 6–11 | NA2 (main) | BAD99519 | [45] |

| Microbulbifer thermotolerans JAMB-A94 | Bacillus subtilis | agaA | extracellular | 45000 | 87 | 16 | 48 | 517 | 55 | 60 | 7.0 | 6–9 | NA4 (main) | BAD29947 | [46] |

| Microbulbifer sp. JAMB-A7 | Bacillus subtilis | agaA7 | extracellular | 25831 | 65 | 16 | 49 | 398 | 50 | 50 | 7.0 | 5–8 | NA4 | BAC99022 | [36] |

| Pseudomonas sp. SK38 |

Escherichia coli BL21 |

pagA | intracellular | - | 16 | 37 | 32.3 | 30 | 37 | 9.0 | 8–9 | - | AF534639 | [48] | |

| Vibrio sp. JT0107 |

Escherichia coli DH5α |

agaA | intracellular | - | 50 | 105 | - | - | - | - | - | - | BAA03541 | [50] | |

| agaB | - | 50 | 103 | BAA04744 | [49] | ||||||||||

| Vibrio sp. V134 |

Escherichia coli BL21 |

agaV | extracellular/intracellular | - | 16 | 52 | - | 40 | - | 7.0 | - | NA4, NA6 | ABL06969 | [8] | |

| Agarivorans albus YKW-34 |

Escherichia coli DH5α |

agaB34 | extracellular | 1670 | 7 | 16 | 30 | 242 | 30 | 50 | 7.0 | 5–9 | NA4 (main) | ABW77762 | [10] |

| Agarivorans sp. LQ48 |

Escherichia coli BL21 |

agaA | extracellular/intracellular | - | 16 | 51 | 349.3 | 40 | 50 | 7.0 | 3–11 | NA4, NA6 | ACM50513 | [41] | |

| Pseudoalteromonas sp. CY24 |

Escherichia coli BL21 |

agaB | extracellular | 17000 | 3 | Novel | 51 | 5000 | 40 | 35 | 6.0 | 5.7–10.6 | NA8, NA10 | - | [51] |

| α-agarase | |||||||||||||||

| Thalassomonas sp. JAMB-A33 | Bacillus subtilis | agaA33 | extracellular | 6950 | 155 | 96 | 87 | 44.7 | 45 | - | 8.5 | 6.5–10.5 | NA4 (main) | BAF44076.1 | [44] |

The conserved domain of agarases in the GH-16 family has been well studied. In the characterized GH-16 enzymes, the location of GH-16 module is directly adjacent to the signal peptide, and the CBM-6 module is in the C-terminal. Such as the agarase AgaA produced by Vibrio sp. PO303 comprises of a typical N-terminal signal peptide of 29 amino acid residues, followed by a 266 amino acid sequence which is homologous to the catalytic module of GH-16 family, a bacterial immunoglobulin group 2 domain of 52 amino acid residues, and a 131 and a 129 amino acid sequences which are homologous to the CBM-6 family [7]. The agarase AgaV produced by Vibrio sp. V134 comprises of a signal peptide of 23 amino acid residues, followed by a 277 amino acid sequence of GH-16 family module, and a 152 amino acid sequence of CBM-6 family module [8]. The agarase AgaB34 produced by Agarivorans albus YKW-34 comprises of a signal peptide of 23 amino acid residues, followed by a 273 amino acid sequence of GH-16 family module, and a 137 amino acid sequence of CBM-6 family module [10]. As the three dimensional structure of a GH-16 family agarase has been revealed, the mechanism of catalysis and substrate binding of this family has been well understood [9,33]. The amino acid residues involving in the active site and the calcium binding site which act catalytic behavior, and those involving in the Q-X-W(F) motif and the sugar binding site which bind with the substrate are highly conserved in enzymes of this family [10].

Six β-agarases belonging to GH-50 family have been reported up to date (see Table 2 for a complete listing and references). These agarases carry partially conserved amino acid sequences of GH-50 family module extending for at least 375 amino acid residues [34]. Contrary to the GH-16 family module, the GH-50 module is located in the C-terminal end of the polypeptides.

AgrA (AAA25696) is reported to be the first agarase classified in the GH-86 family [35], however, there is no related published data. Only three agarases belonging to GH-86 family have been described in publications, i.e., Aga86C and Aga86E, from Saccharophagus degradans 2-40 and AgaO from Microbulbifer-like JAMB-A94. These proteins are modular proteins consisting of CBM-6 family module and GH-86 family catalytic module [34,35]. Though the sequences are highly divergent, the critical amino acid residues (Glu, Asp) which are essential for their activity are conserved in them [35]. An interesting phenomenon is that Saccharophagus degradans 2-40 derived from marine algae has been reported to produce five β-agarases belonging to three different families which form a complex agarolytic system [34].

4. Methods for Detecting Agarase Activity

4.1. Qualitative Assays

Lugol’s iodine solution has been used to visualize agarase activity both for screening the agarase production by microorganism on a culture plate and for identification of protein band of agarase activity after electrophoresis [27]. It stains polysaccharide of agar into a dark brown color, while it can’t stain the degraded oligosaccharides of agar. Thus, a bright clear zone shows around the colony produce agarase and around the protein band possesses agarase activity, while other places are dark brown area.

After electrophoresis, in situ detection of agarase is performed on one gel, and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining is performed on the other gel [25]. SDS in one gel is removed by rinsing the gel three times with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) for each 10 min. Thereafter, the gel is overlaid onto a plate sheet containing 2% agar and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. Finally, the gel is stained by Lugol’s iodine solution (5% I2 and 10% KI in distilled water). A clear zone is formed around the agarase band. To determine the molecular mass by electrophoresis, the other gel is stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue after electrophoresis. The molecular mass of the agarase can be determined by comparing the two gels.

4.2. Quantitative Assays for Agarase Activity

Agarases degrade agar in α-1,3 or β-1,4 glycosidic bonds and from reducing ends. The agarase activity is commonly quantified by spectrophotometric determination of the increase in the concentration of reducing sugars by Nelson method [38] or DNS method [39] using d-galactose as a standard. Enzyme activity (U/mL) was defined as the amount of enzyme required to liberate 1 μmol d-galactose per min.

4.3. Agarase Isolation and Purification

The purification procedure of ammonium sulfate fractionation followed by anion exchange chromatography and gel filtration chromatography has often been used in purification of several agarases [3,6,18,21,22,27,31]. Ammonium sulfate fractionation may be omitted [25] or replaced by acetone precipitation [39] in this procedure. Exchangers have been used in all the above reports for capturing agarase are anion exchanger, which indicates that agarases reported are proteins with pI values lower than 7.

Hydroxyapatite has been successfully used for purification of a few agarases [19,35,36]. The agarase from Thalassomonas sp. JAMB-A33 has been purified by hydroxyapatite, followed by anion exchange chromatography, column purification by hydroxyapatite, anion exchange chromatography, and gel filtration chromatography [19]. Column purification by hydroxyapatite has been used in other cases [35,36]. Besides that, hydrophobic chromatography has been used in purification of rAgaA cloned from Vibrio sp. PO303 [7].

Three kinds of affinity chromatography media have been used in agarase purification up to date. The first kind of medium is the cross-linked agarose such as agarose CL-6B, which results in a marked increase of agarase specific activity based on the specific affinity of enzyme and substrate. This kind of affinity chromatography has been used cooperating with anion exchange chromatography [2,39] or gel filtration chromatography [29]. The second kind of medium is Ni2+ Sepharose which is commonly used to trap the 6-His tagged recombinant protein. It is used for one-step purifications of rAgaD cloned from Vibrio sp. PO-303 [40], five recombinant agarases cloned from S. degradans 2-40 [34], rAgaA from Agarivorans sp. LQ48 [41], and rAgaB34 cloned from Agarivorans sp. YKW-34 [10]. The third kind of medium is chitin bead which is used to trap intein-chitin binding domain. It is successfully applied in a one-step purification of recombinant agarase cloned from Agarivorans sp. JA-1 [42].

Most native and cloned agarases have been purified to high purity with a satisfactory yield. Two agarases AgaA and AgaB from the marine bacterium Zobellia galactanivorans have been highly purified [43], and the enzymes have been used in the growth of crystals for X-ray diffraction studies [33].

5. Characterization of Agarase

5.1. Native Agarase from Marine Environment

Various agarases from marine microorganisms derived from seawater, marine sediments, marine algae, and marine mollusks have been purified and characterized. Their important properties are listed in Table 1. Their molecular masses are highly divergent ranging from 20 to 360 kDa. The smallest agarase is produced by Vibrio sp. AP-2 from marine algae with a Mr of 20 kDa [24], while the largest agarase is produced by Alteromonas agarlyticus GJ1B from seawater with a Mr of 360 kDa [2]. As shown in Table 1, most of the agarases are composed of a single polypeptide, except the agarase produced by Alteromonas agarlyticus GJ1B. Using SDS-PAGE, this purified agarase has been detected as a single band with a molecular mass of 180 kDa. After the affinity-chromatography step, however, the native molecular mass was approximately 360 kDa, suggesting that the native enzyme is a dimer [2].

As shown in Table 1, the specific activities ranging from 6.3 to 292 U/mg. The reported data indicate that agarases purified from genus of Vibrio have lower specific activities, which are 7.54 and 20.8 U/mg from strain PO303 [18] and 6.3 U/mg from strain JT0107 [6]. Agarases from genus Agarivorans show medium specific activities, which are 57.45 and 76.8 U/mg from strain HZ105 [20] and 25.54 U/mg from strain YKW-34 [25]. Agarases from genus Alteromonas and Pseudoalteromonas exhibit high specific activities, which are 83.5 U/mg from Alteromonas sp. SY37-12 [21], 234 U/mg from Alteromonas sp. C-1 [16], and 292 U/mg from Pseudoalteromonas antarctica N-1 [22].

The optimal temperatures for the activity of agarases are similar. The gelling temperature of agar is around 38 °C, and most of reported agarases show optimal activity at temperature above this level (Table 1). Except agarases produced by two kinds of seawater derived bacteria, i.e., Vibrio sp. JT0107 and Alteromonas sp. C-1, possess optimal activity at temperature of 30 °C [6,16], which indicates their potential application in industrial production of neoagarooligosaccharide directly from marine algae under economic conditions. Because the derivation of marine environment, most agarases are not stable in high temperature. Only agarases from Alteromonas sp. SY37-12 and Agarivorans YKW-34 have been reported to be stable up to temperature of 50 °C, others are stable up to 45 °C [2,24], 40 °C [6,19], 30 °C [16,22,23], and 25 °C [20].

Most agarases have been reported to show maximum activity at a neutral [21–23] or a week alkaline pH [2,6,17,19,25]. As we know, the natural seawater is of a week alkaline pH, thus it is reasonable that the marine derived agarase show maximum activity in this condition. Only the agarase from Alteromonas sp. C-1 and Vibrio sp. AP-2 has been reported to possess maximum activity at pH 6.5 [16] and pH 5.5 [24], respectively.

The products are totally different between different categories of the agarase. Two α-agarases derived from marine environment have been reported, i.e., Alteromonas agarlyticus GJ1B and Thalassomonas sp. JAMB-A33, which produce agarotetraose as the main product. Other β-agarases have been reported to produce NA2 [23–25], NA4 [16,22] and NA6 [21] as the predominant product. Agarase from Vibrio sp. JT0107 has been reported to produce the mixture products of NA2 and NA4, however, NA2 is not detected when NA4 is used as a substrate [6]. Three kinds of agarases, i.e., agarase-a, agarase-b, and agarase-c, secrete by a marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain PO-303, have been reported to exhibit different action patterns against agarose. Agarase-a hydrolyzed agarose into NA4 and NA6, agarase-b hydrolyzed agarose into NA2, and agarase-c produced NA6 and NA8 from agarose [18].

5.2. Native Agarase from Fresh Water and Terrestrial Environments

Most agarases are from marine environment, except four agarases have been reported deriving from other environments (Table 1). The molecular mass of the agarase produced by a fresh water bacteria Cytophaga flevensis is 26 kDa [26], while that of soil derived agarase is much higher, which is 100 kDa from Acinetobacter sp. AGLSL-1 [31], 113 kDa from Bacillus sp. MK03 [27] and 180 kDa from Alteromonas sp. E-l [3], respectively. The latter two kinds of agarases are reported to be dimers based on data comparison of SDS-PAGE and gel filtration. It is remarkable that the agarase from Acinetobacter sp. AGLSL-1 show a specific activity of 397 U/mg [31], which is the highest among the native agarases have been reported up to date. There are no special properties as comparing the above four agarases with marine derived agarases in pH and temperature properties. These four agarases are all β-agarases. It is noteworthy that agarases from Alteromonas sp. E-l [3] and Acinetobacter sp. AGLSL-1 [31] have been reported to hydrolyze agarose, NA4, and NA6 to NA2 as the only final product.

5.3. Cloned α-Agarase

rAgaA33 has been cloned from a deep sea sediment bacterium Thalassomonas sp. JAMB-A33 [44]. Two native α-agarases have been reported up to date [2,19], while rAgaA33 is the first and the only α-agarase has been reported to be recombinant produced (Table 2). It has been extracellularly produced using Bacillus subtilis as a host with an extraordinary production of 6950 U/L [44], whereas the native agarase has been intracellularly produced with a low production [19]. As comparing with its native agarase, its enzymatic properties including the molecular mass, the specific activity, temperature and pH activity and stability, and the final products have no significant difference with those of the native one [19,44]. Thus the recombinant α-agarase is successfully produced with a high production and maintains its native properties.

5.4. Cloned β-Agarases

Beside the above one α-agarase, other recombinant agarases are belonging to β-agarases. Escherichia coli is commonly used as a host for recombinant production of agarases (Table 2), while Bacillus subtilis is used for extracellular expression of recombinant β-agarases from Microbulbifer-like JAMB-A94, Agarivorans sp. JAMB-A11, Microbulbifer thermotolerans JAMB-A94, and Microbulbifer sp. JAMB-A7 [35,36,45,46]. Agarases have been intracellularly produced by Escherichia coli in most cases [7,34,40,42,43,47–50]. However, some agarases have been reported to be extracellularly secreted into culture media under the control of their own signal peptide in a few cases [10,39,51]. Agarases cloned from Vibrio sp. V134 and Agarivorans sp. LQ48 have been reported to exist in both culture media and cell pellets. To maintain the bioactivities, the recombinant agarases have been purified from the culture supernatant under native conditions [8,41].

A high level of extracellular production of agarase has been achieved when using B. subtilis as a host [35,36,45,46]. The production of recombinant agarase cloned from Microbulbifer-like JAMB-A94, Agarivorans sp. JAMB-A11, Microbulbifer thermotolerans JAMB-A94, and Microbulbifer sp. JAMB-A7 in the supernatant of the culture medium has been reported to be 7816 U/L [35], 19000 U/L [45], 19000 U/L [46], and 25831 U/L [36], which is calculated to be 80, 51, 87, and 65 mg/L, respectively. When E. coli has been used as a host, the production of agarase is lower than that by B. subtilis when calculate by mg of agarase per L of culture medium (Table 2). These reports indicate that B. subtilis is an efficient engineering strain which can be used for the extracellular over-expression of recombinant agarase.

The molecular mass of cloned β-agarases is ranging from 30 to 147 kDa (Table 2). Each of them has been reported to be single polypeptide with coincident molecular mass determining by SDS-PAGE and deducing from the amino acid sequence. The specific activity of them is divergent (Table 2). It is noticeable that the rAgaB cloned from a seawater derived bacterium Pseudoalteromonas sp. CY24 has been reported to possess a remarkable specific activity of 5,000 U/mg toward agarose [51].

As shown in Table 2, the optimal temperature for the activity of recombinant agarases is mostly around 40 °C, except those cloned from Pseudomonas sp. SK38 and Agarivorans albus YKW-34 which possess optimal activity at temperature of 30 °C [10,48] and that cloned from Microbulbifer sp. JAMB-A7 and Microbulbifer thermotolerans JAMB-A94 which exhibits optimal activity at temperature of 50 °C [36] and 55 °C [46], respectively. Most recombinant agarases are stable up to temperature of 35 °C [47,48,51], 40 °C [40,35,45] and 50 °C [10,36,41], while those cloned from Agarivorans sp. JA-1 and Microbulbifer thermotolerans JAMB-A94 are thermo-tolerant agarases which stable up to 60 °C [42,46].

As shown in Table 2, most recombinant agarases show maximum activity at a neutral or a week alkaline pH, except rAgaC cloned from Vibrio sp. PO-303, and rpagA cloned from Pseudomonas sp. SK38 possesses maximum activity at pH 6.0 [47] and pH 9.0 [48], respectively. Each recombinant agarase has a reasonable pH stability range (Table 2), except a novel agarase cloned from Agarivorans sp. LQ48 which is stable over a wide pH range of 3–11. Further studies by its researchers on the three-dimensional structure of this agarase will provide more information for the mechanism [41].

Agarases belonging to a same GH family display similar digestion profile toward agarose. Generally, the smallest end product or the main product is NA4 by agarases of GH-16 family, NA2 by those of GH-50 family, and NA6 or NA8 by agarases of GH-86 family (Table 2). Recombinant agarases belonging to GH-16 family are abundant, most of which have been reported to produce NA4 as the smallest end product [7,8,10,36,39,41,46], except rAgaA cloned from Vibrio sp. PO303 [40] and rAgaB cloned from Zobellia galactanivorans [43] have been reported to produce NA2 in little amount.

However, the latter two recombinant agarases cannot degrade NA4 into NA2 [40,43]. Six GH-50 family agarases have been recombinant produced, while the products of only two of them have been demonstrated, i.e., agarase clone from Agarivorans sp. JA-1 [42] and rAgaA11 cloned from Agarivorans sp. JAMB-A11 [45]. These two agarases have been reported to hydrolyze not only agarose, but also NA4, to yield NA2 as the main end product [42,45].

Agarases belonging to GH-86 family are seldom found, and only two of them have been detailed described. The main product of rAgaC cloned from Vibrio sp. PO303 [47] and rAga86O cloned from Microbulbifer-like JAMB-A94 [35] is NA8 and NA6, respectively. It is noteworthy that the agaB gene of Pseudoalteromonas sp. CY24 has no significant sequence similarity with that of any known protein and the produced rAgaB hydrolyzes agarose forming NA8 and NA10 as the main end products. It has been concluded that this recombinant agarase belongs to be an unknown GH family [51].

6. Applications of Agarases

6.1. Recovery of DNA from Agarose Gel

Agarases have been widely used to recover DNA bands from the agarose gel. They are indispensable tools used in biological research field. Takara Company produces agarose gel DNA purification kit by using a β-agarase with thermo-stability up to 60 °C [52]. The agarase produced by Vibrio sp. JT0107 recovered 60% of the applied DNA from the gel by heating at 65 °C for 5 min [50]. Gold has reported the use of a novel gel-digesting enzyme preparation which provides an easy, rapid, and convenient method to recover PCR-amplified DNA from low melting point agarose gels [53].

6.2. Production of Agar-Derived Oligosaccharides

Agarases have been used for agar-derived oligosaccharides production. Comparing to the traditional acid degradation method, the enzyme degradation method has a lot of remarkable advantages, such as tender reaction condition, excellent efficiency, controllable products, simple facilities, low energy cost, little environment pollution. A simple method of preparing diverse neoagaro-oligosaccharides has been established using recombinant AgaA and AgaB cloned from Pseudoaltermonas sp. CY24 [51], in which agarose has been hydrolyzed into NA4, NA6, NA8, NA10, and NA12 [54].

The agar-derived oligosaccharides include agarooligosaccharides and neoagarooligosaccharides. Various reports indicated their high economic values due to their physiological and biological activities. Oligosaccharides have been prepared from agar by crude agarase from Vibrio QJH-12 isolated from the South China Sea coast [4]. The oligosaccharides mixture exhibit antioxidative activities in scavenging hydroxyl free radical, scavenging superoxide anion radical, and inhibiting lipid peroxidation. The oligosaccharides with the sulfate group or with higher molecular masses show stronger antioxidative activities than that without the sulfate group or with smaller molecular masses [4]. In a later report, the products mixture containing NA4 and NA6, which digested from algal polysaccharide by crude agarase products from MA103 strain, have shown high anti-oxidative properties by five in vitro methods [55,56]. The result indicates that neoagarooligosaccharide may have potential application in health food. Neoagarooligosaccharides have been reported to inhibit the growth of bacteria, slow down the degradation of starch, and used as low-calorie additives to improve food qualities [57]. The low polymerization degree (DP) product, such as NA2, has been reported to have a moisturizing effect on skin and a whitening effect on melanoma cells [58]. Furthermore, the higher molecular mass product, such as NA6, has been reported to exhibit as a more efficient moisturizer on skin than smaller oligosaccharides, because the viscosity of NA6 is higher than that of NA4 and NA2 [35]. Owning to these characteristics, neoagarooligosaccharides have potential applications in food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries.

6.3. Research on Seaweed Bio-Substances and Preparation of Seaweed Protoplasts

Agarases have potential application in degrade the cell wall of red algae for extraction of labile substances with biological activities such as unsaturated fatty acids, vitamins, carotenoids from algae. Yaphe has used the agarase from Pseudomonas atlantic [23] in the identification of agar in marine algae (Rhodophyceae) [59]. Agarases have also been used to prepare of protoplasts. Protoplasts isolated from marine algae are useful experimental materials for physiological and cytological studies, and excellent tools for plant breeding by cell fusion and gene manipulation [60]. Araki has succeeded in the isolation of protoplasts from Bangia atropurpurea (Rhodophyta) by using three kinds of enzymes, i.e., β-1,4-mannanase, β-1,3-xylanase, and agarase prepared from three marine bacteria, i.e., Vibrio sp. MA-138, Alcaligenes sp. XY-234, and Vibrio sp. PO-303 [18], respectively [61]. The rAgaA, rAgaC, and rAgaD cloned from Vibrio sp. PO303 [7,40,47] have been reported to hydrolyze not only agarose and agar but also porphyran. Porphyran is a unique polysaccharide composing of a linear chain of alternating residues of 3-O-linked β-d-galactopyranose and 4-O-linked 3,6-anhydro-α-l-galactose. It is contained in the cell wall of Porphyra which is an important edible red seaweed. Hence, by combination with β-1,4-mannanase and β-1,3-xylanase, these agarases might be a useful tool for isolation of protoplasts from Porphyra.

7. Concluding Remarks

From the collective information on agarases, we conclude that agarases are important enzymes naturally purified and cloned from variety of microorganisms. They are characterized into two categories with more than four families which can produce various oligosaccharides with different DP values. A few agarases have a remarkable production and possess excellent properties such as high specific activity, excellent temperature and pH stability, which enlighten their widely potential applications.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the grant (No. RTI05-01-02) of the Regional Technology Innovation Program of the Ministry of Knowledge Economy (MKE), Korea. X.T. Fu was the recipient of a graduate fellowship provided by the Brain Korea (BK21) program sponsored by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Korea.

References

- 1.Araki CH. Acetylation of agar like substance of Gelidium amansii. J Chem Soc. 1937;58:1338–1350. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potin P, Richard C, Rochas C, Kloareg B. Purification and characterization of the α-agarase from Alteromonas agarlyticus (Cataldi) comb. nov., strain GJ1B. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirimura K, Masuda N, Iwasaki Y, Nakagawa H, Kobayashi R, Usami S. Purification and characterization of a novel β-agarase from an alkalophilic bacterium, Alteromonas sp. E-1. J Biosci Bioeng. 1999;87:436–441. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(99)80091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J, Jiang X, Mou H, Guan H. Anti-oxidation of agar oligosaccharides produced by agarase from a marine bacterium. J Appl Phycol. 2004;16:333–340. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Araki T, Lu Z, Morishita T. Optimization of parameters for isolation of protoplasts from Gracilaria verrucosa (Rhodophyta) J Mar Biotechnol. 1998;6:193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugano Y, Terada I, Arita M, Noma M. Purification and characterization of a new agarase from a marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain JT0107. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1549–1554. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1549-1554.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong J, Tamaru Y, Araki T. A unique β-agarase, AgaA, from a marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain PO-303. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;74:1248–1255. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang WW, Sun L. Cloning, characterization and molecular application of a beta-agarase gene from Vibrio sp. V134. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:2825–2831. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02872-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allouch J, Helbert W, Henrissat B, Czjzek M. Parallel substrate binding sites in a beta-agarase suggest a novel mode of action on double-helical agarose. Structure. 2004;12:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu XT, Pan CH, Lin H, Kim SM. Gene cloning, expression, and characterization of a β-Agarase, AgaB34, from Agarivorans albus YKW-34. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;19:257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armisén R, Galatas F, Hispanagar SA. Agar. In: Phillips GO, Williams PA, editors. Handbook of Hydrocolloids. Woodhead Publishing Ltd; Cambridge, UK: 2000. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ji MH. Agar. In: Ji MH, editor. Seaweed Chemistry. Science Press; Beijing, China: 1997. pp. 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamer GK, Bhattacharjee SS, Yaphe W. Analysis of the enzymic hydrolysis products of agarose by 13C-n.m.r. spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res. 1977;54:7–l0. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armisen R, Galatas F. Production, properties and uses of agar. In: McHugh DJ, editor. Production and Utilization of Products from Commercial Seaweeds, FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Rome, Italy: 1987. pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Liu L, Wang YM, Yuan QY, Li ZE, Xu ZH. Comparative research on the structures and physical-chemical properties of agars from several agarophyta. Oceanologia Etlimnologia Sinica. 2001;36:658–664. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leon O, Quintana L, Peruzzo G, Slebe JC. Purification and properties of an extracellular agarase from Alteromonas sp. strain C-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:4060–4063. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.4060-4063.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duckworth M, Turvey JR. An extracellular agarase from a Cytophaga species. Biochem J. 1969;113:139–142. doi: 10.1042/bj1130139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Araki T, Hayakawa M, Zhang L, Karita S, Morishita T. Purification and characterization of agarases from a marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. PO-303. J Mar Biotechnol. 1998;6:260–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohta Y, Hatada Y, Miyazaki M, Nogi Y, Ito S, Horikoshi K. Purification and characterization of a novel α-agarase from a Thalassomonas sp. Curr Microbiol. 2005;50:212–216. doi: 10.1007/s00284-004-4435-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu Z, Lin BK, Xu Y, Zhong MQ, Liu GM. Production and purification of agarase from a marine agarolytic bacterium Agarivorans sp. HZ105. J Appl Microbiol. 2008;106:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang JX, Mou HJ, Jiang XL, Guan HS. Characterization of a novel β-agarase from marine Alteromonas sp. SY37–12 and its degrading products. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;71:833–839. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vera J, Alvarez R, Murano E, Slebe JC, Leon O. Identification of a marine agarolytic Pseudoalteromonas isolate and characterization of its extracellular agarase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4378–4383. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4378-4383.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrice LM, McLean MW, Williamson FB, Long WF. beta-agarases I and II from Pseudomonas atlantica. Purifications and some properties. Eur J Biochem. 1983;135:553–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aoki T, Araki T, Kitamikado M. Purification and characterization of a novel β-agarase from Vibrio sp. AP-2. Eur J Biochem. 1990;187:461–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu XT, Lin H, Kim SM. Purification and characterization of a novel β-agarase, AgaA34, from Agarivorans albus YKW-34. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;78:265–273. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van der Meulen HJ, Harder W. Production and characterization of the agarase of Cytoplaga flevensis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1975;41:431–447. doi: 10.1007/BF02565087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki H, Sawai Y, Suzuki T, Kawai K. Purification and characterization of an extracellular β-agarase from Bacillus sp. MK03. J Biosci Bioeng. 2003;93:456–463. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(02)80092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakshmikanth M, Manohar S, Souche Y, Lalitha J. Extracellular β-agarase LSL-1 producing neoagarobiose from a newly isolated agar-liquefying soil bacterium, Acinetobacter sp., AG LSL-1. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;22:1087–1094. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malmqvist M. Purification and characterization of two different agarose degrading enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;537:31–43. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(78)90600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groleau D, Yaphe W. Enzymatic hydrolysis of agar: purification and characterization of beta-neoagarotetraose hydrolase from Pseudomonas atlantica. Can J Microbiol. 1977;23:672–679. doi: 10.1139/m77-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lakshmikanth M, Manohar S, Lalitha J. Purification and characterization of β-agarase from agar-liquefying soi bacterium Acinetobacter sp., AG LSL-1. Process Biochem. 2009;44:999–1003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henshaw J, Horne-Bitschy A, van Bueren AL, Money VA, Bolam DN, Czjzek M, Ekborg NA, Weiner RM, Hutcheson SW, Davies GJ, Boraston AB, Gilbert HJ. Family 6 carbohydrate binding modules in beta-agarases display exquisite selectivity for the non-reducing termini of agarose chains. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17099–17107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allouch J, Jam M, Helbert W, Barbeyron T, Kloareg B, Henrissat B, Czjzek M. The three-dimensional structures of two beta-agarases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47171–47180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ekborg NA, Taylor LE, Longmire AG, Henrissat B, Weiner RM, Hutcheson SW. Genomic and proteomic analyses of the agarolytic system expressed by Saccharophagus degradans 2–40. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:3396–3405. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3396-3405.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohta Y, Hatada Y, Nogi Y, Li Z, Ito S, Horikoshi K. Cloning, expression, and characterization of a glycoside hydrolase family 86 β-agarase from a deep-sea Microbulbifer-like isolate. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;66:266–275. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1757-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohta Y, Hatada Y, Nogi Y, Miyazaki M, Li Z, Akita M, Hidaka Y, Goda S, Ito S, Horikoshi K. Enzymatic properties and nucleotide and amino acid sequences of a thermostable β-agarase from a novel species of deep-sea Microbulbifer. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;64:505–514. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1573-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson N. A photometric adaptation of the somogyi method for the determination of glucose. J Biol Chem. 1944;153:375–380. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernfeld P. Amylases, α and β. In: Colowick SP, Kaplan ND, editors. Methods Enzymol. Academic Press; New York, NY, USA: 1955. pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ha JC, Kim GT, Kim SK, Oh TK, Yu JH, Kong IS. beta-agarase from Pseudomonas sp. W7: purification of the recombinant enzyme from Escherichia coli and the effects of salt on its activity. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 1997;26:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong J, Tamaru Y, Araki T. Molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of a β-agarase gene, agaD, from a marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain PO-303. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71:38–46. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Long MX, Yu ZN, Xu X. A Novel β-Agarase with high pH stability from marine Agarivorans sp. LQ48. Mar Biotechnol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10126-009-9200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee DG, Park GT, Kim NY, Lee EJ, Jang MK, Shin YG, Park GS, Kim TM, Lee JH, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Lee SH. Cloning, expression, and characterization of a glycoside hydrolase family 50 β-agarase from a marine Agarivorans isolate. Biotechnol Lett. 2006;28:1925–1932. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9171-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jam M, Flament D, Allouch J, Potin P, Thion L, Kloareg B, Czjzek M, Helbert W, Michel G, Barbeyron T. The endo-β-agarases AgaA and AgaB from the marine bacterium Zobellia galactanivorans: two paralogue enzymes with different molecular organizations and catalytic behaviours. Biochem J. 2005;385:703–713. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatada Y, Ohta Y, Horikoshi K. Hyperproduction and application of alpha-agarase to enzymatic enhancement of antioxidant activity of porphyran. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:9895–9900. doi: 10.1021/jf0613684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohta Y, Hatada Y, Ito S, Horikoshi K. High-level expression of a neoagarobiose-producing β-agarase gene from Agarivorans sp. JAMB-A11 in Bacillus subtilis and enzymic properties of the recombinant enzyme. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2005;41:183–191. doi: 10.1042/BA20040083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohta Y, Nogi Y, Miyazaki M, Li Z, Hatada Y, Ito S, Horikoshi K. Enzymatic properties and nucleotide and amino acid sequences of a thermostable β-agarase from the novel marine isolate JAMB-A94. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2004;68:1073–1081. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dong J, Hashikawa S, Konishi T, Tamaru Y, Araki T. Cloning of the novel gene encoding beta-agarase C from a marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain PO-303, and characterization of the gene product. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:6399–6401. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00935-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang NY, Choi YL, Cho YS, Kim BK, Jeon BS, Cha JY, Kim CH, Lee YC. Cloning, expression and characterization of a beta-agarase gene from a marine bacterium, Pseudomonas sp. SK38. Biotechnol Lett. 2003;25:1165–1170. doi: 10.1023/a:1024586207392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sugano Y, Matsumoto T, Noma M. Sequence analysis of the agaB gene encoding a new beta-agarase from Vibrio sp. strain JT0107. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1218:105–108. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugano Y, Matsumoto T, Kodama H, Noma M. Cloning and sequencing of agaA, a unique agarase 0107 gene from a marine bacterium, Vibrio sp. strain JT0107. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3750–3746. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3750-3756.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma C, Lu X, Shi C, Li J, Gu Y, Ma Y, Chu Y, Han F, Gong Q, Yu W. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel beta-agarase, AgaB, from marine Pseudoalteromonas sp. CY24. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3747–3754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.TaKaRa Agarose Gel DNA Purification Kit product protocol.

- 53.Gold P. Use of a novel agarose gel-digesting enzyme for easy and rapid purification of PCR-amplified DNA for sequencing. Biotechniques. 1992;13:132–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li J, Han F, Lu X, Fu X, Ma C, Chu Y, Yu W. A simple method of preparing diverse neoagaro-oligosaccharides with beta-agarase. Carbohydr Res. 2007;342:1030–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu SC, Pan CL. Preparation of algal-oligosaccharide mixtures by bacterial agarases and their antioxidative properties. Fish Sci. 2004;70:1164–1173. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu SC, Wen TN, Pan CL. Algal-oligosaccharide-lysates prepared by two bacterial agarases stepwise hydrolyzed and their anti-oxidative properties. Fish Sci. 2005;71:1149–1159. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giordano A, Andreotti G, Tramice A, Trincone A. Marine glycosyl hydrolases in the hydrolysis and synthesis of oligosaccharides. Biotechnol J. 2006;1:511–530. doi: 10.1002/biot.200500036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kobayashi R, Takimasa M, Suzuki T, Kirimura K, Usami S. Neoagarobiose as a novel moisturizer with whitening effect. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61:162–163. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yaphe W. The use of agarase from Pseudomonas atlantica in the identification of agar in marine algae (Rhodophyceae) Can J Microbiol. 1957;3:987–993. doi: 10.1139/m57-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carlson PS. The use of protoplasts for genetic research. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1973;70:598–602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.2.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Araki T, Lu Z, Morishita T. Optimization of parameters for isolation of protoplasts from Gracilaria verrucosa (Rhodophyta) J Mar Biotechnol. 1998;6:193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]