Abstract

Purpose

We report the development of a patient-derived, health related quality of life (HRQOL) questionnaire for adults with strabismus.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Participants

29 patients with strabismus in a first phase, and 32 patients with strabismus, 18 patients with other eye diseases, and 13 visually normal adults in a second phase.

Methods

Individual patient interviews generated 181 questionnaire items. For item reduction, we asked 29 patients with strabismus to complete the 181-item questionnaire, analyzed responses, and performed factor analysis. Two prominent factors were identified, and the 10 items with the highest correlation with each factor were selected. The final 20-item questionnaire (10 ‘psychosocial’ items, 10 ‘function’ items) was administered to an additional 32 patients with strabismus (22 with diplopia, 10 without diplopia), 13 visually normal adults, and 18 patients with other eye diseases. A 5-point Likert-type scale was used for responses (‘never’=100, ‘rarely’=75, ‘sometimes’=50, ‘often’=25, and ‘always’=0). Median overall questionnaire scores and psychosocial and function sub-scale scores, ranging from 0 (worst HRQOL) to 100 (best HRQOL), were compared across groups.

Main Outcome Measures

HRQOL questionnaire response scores.

Results

Median overall scores were statistically significantly lower (worse quality of life) for patients with strabismus (56) compared to visually normal adults (95; P<0.001) and patients with other eye diseases (86; P<0.001). Median scores on the psychosocial sub-scale were significantly lower for strabismus patients (69) compared to visually normal adults (99; P<0.001) and patients with other eye diseases (94; P<0.001). For the function sub-scale, median scores were again significantly lower for strabismus patients (43) compared to visually normal adults (91; P<0.001) and patients with other eye diseases (78; P<0.001).

Conclusions

We have developed a 20-item, patient-derived HRQOL questionnaire specific for adults with strabismus, with sub-scales to assess psychosocial and function concerns. This 20-item, condition specific questionnaire will be useful for assessing HRQOL in individual strabismus patients and also as an outcome measure for clinical trials.

Introduction

Evaluation of health related quality of life (HRQOL) is increasingly recognized as an important aspect of strabismus management.1–6 Strabismus is known to impact HRQOL in adults,1, 2, 4–9 but formal assessment of HRQOL is not typically performed in clinical practice. In a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology, formal assessment from the patient’s perspective was recommended as being “more likely to reflect …visual function, social interactions and self-esteem.”3 HRQOL assessment may be performed using either condition-specific or generic instruments. Condition-specific questionnaires address concerns that are important to a particular patient population, and this may lead to better detection of change than a generic instrument.10, 11 Currently there are few well developed, validated HRQOL instruments that may be appropriate for use in patients with strabismus.12 We previously reported13 identification of specific HRQOL concerns in adults with strabismus by means of individual patient interviews. In this present study we report the use of these patient-derived concerns13 in the development of a condition specific questionnaire for adults with strabismus.

Patients and Methods

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained and each patient gave informed consent before participating. All procedures and data collection were conducted in a manner compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Items for the questionnaire were identified from individual patient interviews undertaken in a previous phase of the study.13 Each unique statement or phrase from the interviews was converted into a question, generating a 181-item questionnaire. We aimed to refine this 181-item questionnaire to a more feasible number of items. Our present study was conducted in two phases: firstly, ‘development of final questionnaire,’ and secondly, ‘testing of final questionnaire.’

Development of final questionnaire

Twenty-nine consecutive adult patients (median age 51, range 25 to 85 years) with any type of strabismus (18 [62%] with diplopia; 11 [38%] without diplopia) were recruited from outpatient clinics. Nineteen (66%) of 29 were female and 27 (93%) patients self-reported their race as ‘White.’ Thirteen (45%) of 29 patients had undergone surgery in a previous episode of care, but symptomatic strabismus was still present at the time of assessment. An additional two (7%) of the 29 patients were interviewed within 6 weeks of successful surgery but were able to clearly recall how strabismus had affected them before surgery. For the 18 patients with diplopia, strabismus types were: 4th nerve palsy (4), Graves eye disease (3), 6th nerve palsy (2), consecutive strabismus (2), and one each with divergence insufficiency, decompensated esotropia, residual esotropia, post cataract surgery strabismus, sensory exotropia, post scleral buckle strabismus, and a combined 6th and 4th nerve palsy. Four (22%) of 18 were of childhood onset. For the 11 patients without diplopia, strabismus types were: consecutive strabismus (4), sensory exotropia (2), and one each with intermittent exotropia, residual esotropia, 4th nerve palsy, Brown syndrome, and post scleral buckle strabismus. All 11 were of childhood onset.

The 29 adult strabismus patients were asked to answer all 181 questionnaire items. The questionnaire was administered under direct supervision by the same investigator (SRH) to maintain a standard procedure for instructing the patients and to minimize errors and omissions. Patients were asked to comment if they didn’t understand an item or were confused about the wording, and these comments were recorded. For each item, a 5-point Likert type scale (‘never,’ ‘rarely,’ ‘sometimes,’ ‘often,’ and ‘always’) was used for responses, as well as the option to rate the item ‘not applicable.’

For each item, responses were analyzed overall and by sub-groups of patients with and without diplopia. To identify the final items, we excluded items in the following steps: 1) removed items where >10% of either diplopic or non diplopic patients rated the item as ‘not applicable;’ 2) removed items where >80% of either diplopic or non-diplopic patients responded ‘never’ or ‘rarely’ or responded ‘often’ or ‘always’ (indicating a ‘floor’ or ‘ceiling’ effect);’ 3) removed items where there was one or more negative comment regarding the wording or clarity of the item; 4) removed items that would not be expected to be responsive to intervention or would not apply after treatment for strabismus; 5) removed items that were considered likely to discriminate between patients based on socio-economic, cultural, or educational status; 6) removed items that did not explicitly measure HRQOL (but were more descriptive of symptoms); 7) performed factor analysis, replacing any remaining ‘not applicable’ responses (32 (2%) of the 1421 total responses) with the response of the best correlated item and calculating loading thresholds. A loading threshold of ≥0.5 was used to identify items that correlated well to the underlying factors. 8) Since we had a large number of remaining items for each factor, the number of desired items for each factor was set at 10 to yield a convenient final questionnaire. For each factor, the 10 items with the highest loading were selected. 9) Cronbach’s alpha14 was used to assess the internal consistency reliability of remaining items in each factor. If Cronbach’s alpha increased when an item was removed (indicating poor correlation with remaining items), we planned to remove the item from the scale. All statistical analyses were done using SAS computer software version 9.1.3.

Testing of final questionnaire

To test the ability of the final 20-item questionnaire to discriminate between subjects with and without strabismus, the questionnaire was administered to 32 additional patients with strabismus, 13 visually normal adults (without experience in the clinical management of strabismus), and 18 patients with eye diseases other than strabismus.

For the 32 strabismus patients (median age 46.5, range 21 to 81 years), diagnoses were: 4th nerve palsy (6), intermittent or decompensated exotropia (4), consecutive exotropia (4), post scleral buckle strabismus (3), infantile esotropia (3), 4th plus 3rd nerve palsies (2), decompensated esotropia (2), 6th nerve palsy (2), 3rd nerve palsy (2), and one each with convergence spasm, convergence insufficiency, exotropia with Parinaud’s syndrome, and post scleral plaque strabismus. Twenty-two (69%) of 32 had diplopia and 10 (31%) did not. Visual acuity ranged from 20/15 to 20/50 (median 20/20) for the better eye and 20/15 to 20/60 (median 20/20) for the worse eye. For the 7 patients with a primary esodeviation, median angle of deviation by prism and alternating cover test (PACT) at distance was 20 prism diopters (pd) (range 0 to 30 pd; the patient with 0 in primary position had esotropia on right gaze). For the 14 patients with a primary exodeviation, median PACT at distance was 27 pd (range 7 to 52 pd), and for the 11 patients with a primary vertical deviation, median PACT at distance was 14 pd (range 1 to 35 pd; the patient with 1 pd of vertical deviation also had significant excyclotorsion).

The 13 visually normal adults (median age 47, range 25 to 59 years) with no history of strabismus or amblyopia were orthotropic and had no more than 10 pd of horizontal and 1 pd of vertical heterophoria by PACT. For all normal subjects, stereoacuity was 40 seconds of arc using the Frisby test, and best corrected visual acuity was at least 20/25 in each eye (median 20/20 in each eye).

The 18 patients with other eye diseases (median age 72.5, range 27 to 84 years) were consecutively recruited from cataract, cornea, and glaucoma clinics. Diagnoses were cataract (7), corneal disease (4), glaucoma (3), retinal disease (3), and ocular trauma (1). All patients had no history of strabismus or amblyopia, were orthotropic, and had no more than 10 pd of horizontal and 1 pd of vertical heterophoria by PACT. In these subjects with other eye diseases, visual acuity ranged from 20/20 to 20/40 (median 20/20) for the better eye and from 20/20 to 20/70 for the worse eye (median 20/30).

For each questionnaire item, a 5-point Likert scale was used for responses: ‘never’ (score 100), ‘rarely’ (score 75), ‘sometimes’ (score 50), ‘often’ (score 25), and ‘always’ (score 0). Questionnaires were self-administered, with simple written and verbal instructions. For each patient, we calculated a mean overall questionnaire score (mean of 20 items), mean psychosocial sub-scale, and mean function sub-scale scores (mean of 10 items for each sub-scale). Individual patient scores were then used to calculate median overall and sub-scale scores for each group (strabismus, normal, other eye diseases), yielding scores from 0 (worst HRQOL) to 100 (best HRQOL). Median overall and sub-scale scores were compared using Kruskal-Wallis and Wilcoxon tests. For strabismus patients, scores were compared between patients with and without diplopia.

Results

Development of final questionnaire

Of the 181 items, 56 were removed because they were rated ‘not applicable’ by >10% of either diplopic or non diplopic patients. An additional 42 items were removed as they were rated ‘never’ or ‘rarely’ by more than 80% of either diplopic or non-diplopic patients; none were removed due to more than 80% rating ‘often’ or ‘always.’ A further 26 items were removed because there was one or more negative comment regarding the wording or clarity. No additional items were removed due to being unlikely to respond to treatment. Four additional items were removed because of their potential to discriminate between patients based on socio-economic, cultural, or educational status, and four items were removed because they did not explicitly measure HRQOL. In total, 132 (73%) of 181 items were removed, leaving 49 items for factor analysis.

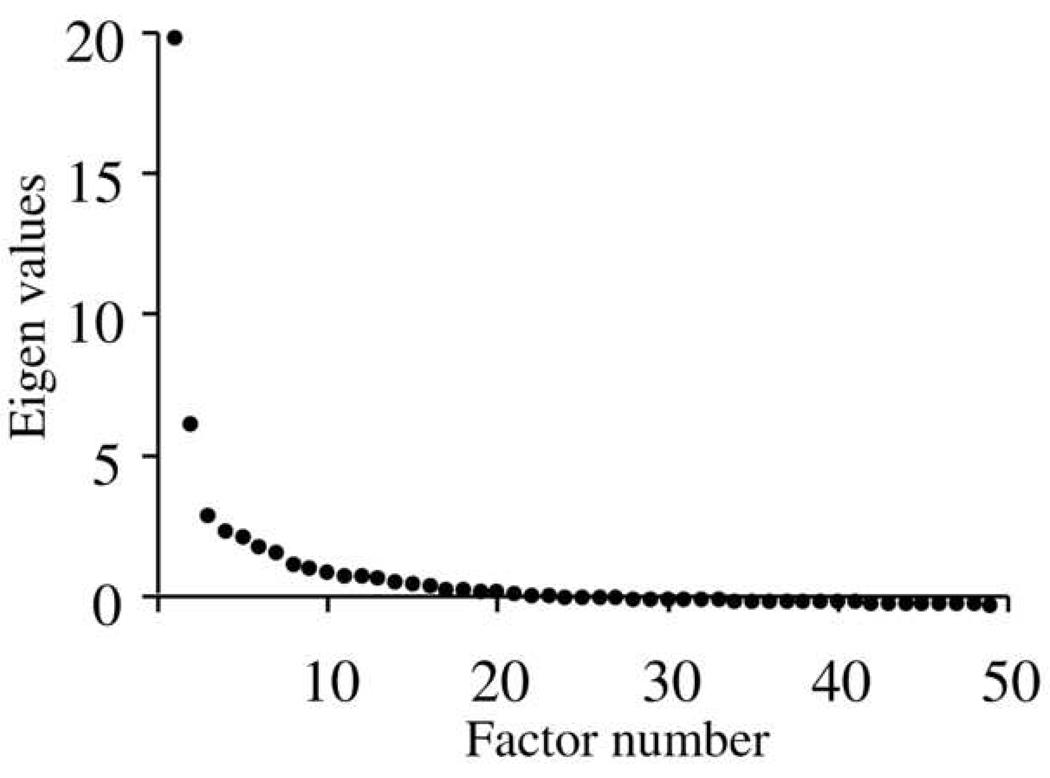

Reviewing the scree plot (Figure 1, available at http://aaojournal.org), two prominent factors were evident on the steep phase of the curve, accounting for 68.8% of the overall variance. The proportion of variance attributable to the first factor was 52.6% and to the second factor was 16.2%. Two factors were forced for remaining analyses. Reviewing the items within each factor, it was apparent that the first factor contained items relating to psychosocial functioning and self awareness, and the second factor contained items relating to physical and emotional functions. We therefore designated the two factors as sub-scales labeled ‘psychosocial’ and ‘function’ respectively. Because these factors address very different concerns that may differentiate between patients with and without diplopia, we aimed to equally represent each factor by selecting the 10 items in each factor with the highest loading (i.e., correlation between the item and underlying factor). Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each subscale. Removing each item in turn resulted in no increase in Cronbach’s alpha, indicating that all items within each subscale correlated well with each other, and therefore no items were removed. This process resulted in a final questionnaire containing a total of 20 items, 10 in the psychosocial factor and 10 in the function factor (Table 1. See Appendix 1 for questionnaire with user instructions, available at http://aaojournal.org). Overall Cronbach’s alpha for the final 20-item questionnaire was 0.94. For the psychosocial sub-scale, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95, and for the function sub-scale was 0.94.

Figure 1.

Scree plot showing eigen values for main factor analysis. Two strong factors are evident on the steep phase of the curve.

Table 1.

Twenty items selected for the final questionnaire, divided into psychosocial and function sub-scales.

| Psychosocial sub-scale: |

| 1) I worry about what people will think about my eyes |

| 2) I feel that people are thinking about my eyes even when they don’t say anything |

| 3) I feel uncomfortable when people are looking at me because of my eyes |

| 4) I wonder what people are thinking when they are looking at me because of my eyes |

| 5) People don’t give me opportunities because of my eyes |

| 6) I am self conscious about my eyes |

| 7) People avoid looking at me because of my eyes |

| 8) I feel inferior to others because of my eyes |

| 9) People react differently to me because of my eyes |

| 10) I find it hard to initiate contact with people I don’t know because of my eyes |

| Function sub-scale: |

| 11) I cover or close one eye to see things better |

| 12) I avoid reading because of my eyes |

| 13) I stop doing things because my eyes make it difficult to concentrate |

| 14) I have problems with depth perception |

| 15) My eyes feel strained |

| 16) I have problems reading because of my eye condition |

| 17) I feel stressed because of my eyes |

| 18) I worry about my eyes |

| 19) I can’t enjoy my hobbies because of my eyes |

| 20) I need to take frequent breaks when reading because of my eyes |

Testing of final questionnaire

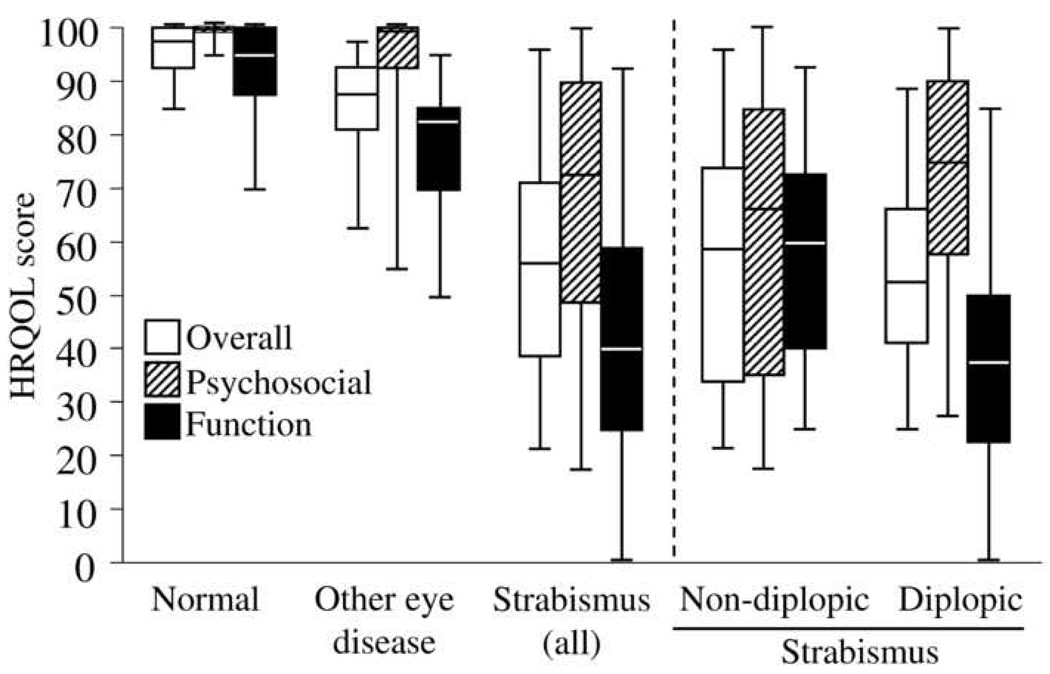

Overall scores ranged from 21 to 96 for strabismus patients, 85 to 100 for normal subjects, and 63 to 98 for patients with other eye diseases (Figure 2). Psychosocial sub-scale scores ranged from 18 to 100 for strabismus patients, 95 to 100 for normal subjects, and 55 to 100 for patients with other eye diseases. Function sub-scale scores ranged from 0 to 93 for strabismus patients, 70 to 100 for normal subjects, and 50 to 95 for patients with other eye diseases (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overall, psychosocial subscale and function subscale health related quality of life (HRQOL) scores on the AS-20 for visually normal adults, patients with other eye diseases, and patients with strabismus. Scores are also shown separately for strabismus patients with and without diplopia. Medians are shown as the central line, quartiles as boxes, and extremes as whiskers.

Strabismus versus normal and other eye diseases

Analysis of median overall scores for strabismus patients, visually normal adults, and patients with other eye diseases showed a significant difference between groups (Kruskal-Wallis; P<0.001). Comparisons between groups showed that median overall questionnaire scores were statistically significantly lower (worse HRQOL) for patients with strabismus (56) compared to both visually normal adults (98; P<0.001) and patients with other eye diseases (88; P<0.001, Figure 2). For patients with other eye diseases, overall scores were significantly lower compared to visually normal adults (88 versus 98; P=0.001). Although this difference between other eye diseases and visually normal adults was significant, the magnitude of the difference was much smaller than between strabismus patients and visually normal adults.

Median scores on the psychosocial sub-scale were significantly lower for strabismus patients (73) compared to both visually normal adults (100; P<0.001) and patients with other eye diseases (100; P<0.001, Figure 2).

For the function sub-scale, median scores were again significantly lower for strabismus patients (40) compared to visually normal adults (95; P<0.001) and patients with other eye diseases (83; P<0.001, Figure 2).

Strabismus with and without diplopia

For the 22 patients with diplopia, median overall, psychosocial, and function scores (53, 75, and 38 respectively) were significantly lower than for visually normal adults and patients with other eye diseases (P<0.001 for all comparisons). For the 10 patients without diplopia, median overall, psychosocial, and function scores (59, 66, and 60 respectively) were also significantly lower than for visually normal adults and patients with other eye diseases (P<0.009 for all comparisons, Figure 2).

Comparing strabismus patients with and without diplopia, the median overall score for the 22 patients with diplopia was not significantly different from the median overall score for the ten patients without diplopia (53 versus 59, P=0.5). Median scores on the function sub-scale were significantly lower (worse HRQOL) for diplopic patients than for non-diplopic patients (38 versus 60, P=0.03, Figure 2). For the psychosocial sub-scale, median scores were similar for patients without diplopia compared to patients with diplopia (66 versus 75; P=0.3).

Discussion

Using specific, patient-derived concerns, we have developed a 20-item Adult Strabismus questionnaire (AS-20) for assessing HRQOL in adults with strabismus. By following recognized processes for refining and testing the questionnaire, we have identified 20 questionnaire items in two sub-scales (psychosocial and function) specifically for patients with strabismus. Patients with strabismus, whether with or without diplopia, scored lower (worse HRQOL) using the AS-20 than both visually normal subjects and patients with other eye diseases.

Formal assessment of HRQOL in adults with strabismus provides a more precise understanding of the effects of strabismus for an individual patient. Other strabismus-specific HRQOL instruments have been designed for use in adults,1, 2, 4, 5, 7 but only one, the Amblyopia and Strabismus Questionnaire,7, 15 reports using some patient input in the derivation of questionnaire items. Using patient-derived concerns as the basis for developing a HRQOL instrument has been strongly suggested as more appropriate than using only physician-derived concerns.12, 16–18 Nevertheless, testing of the English translation of the Amblyopia and Strabismus Questionnaire (ASQE) in American adults with strabismus15 showed that two of the final 26 items were rated ‘not relevant’ by 44% (‘I have difficulties finding my way in a train station’) and 37% (‘I have difficulties playing ball games’) of patients.15 The scoring system for the ASQE allocates the highest possible score (best HRQOL) for unanswered or ‘not relevant’ responses (an option on 6 items relevant to strabismus patients), reflecting better HRQOL (http://www.retinafoundation.org/pdf/questionnaire/asqe.pdf, accessed August 5, 2008). We chose to avoid potential ‘not relevant’ responses by selecting items that were generalisable to the adult population, but still specific to strabismus.

Whether or not generic instruments such as the NEI-VFQ-2519 are useful in patients with strabismus is the focus of an ongoing study by our research group. Nevertheless, the AS-20 appears specific to strabismus in that scores for patients with other eye diseases were more similar to scores for normal adults than they were to scores of patients with strabismus.

To retain generalisable items and avoid item bias,20 we excluded questions that may discriminate between individuals based on differences such as economic status or cultural background. Similar rigorous item selection processes are described for the development of other HRQOL instruments, including the NEI-VFQ-25.17–19 We also excluded items that rated purely the presence or severity of symptoms (e.g. ‘I have double vision’) rather than the effect those symptoms may have on HRQOL (e.g. ‘I cover or close one eye to see things better,’ Question 11, Table 1). As a result, some topic areas mentioned frequently in the previous interview phase of the study13 were not represented in the final AS-20. For example, during interviews, ‘Driving’ was mentioned by 82% of patients with diplopia and 69% of patients without diplopia.13 Nevertheless, in the item selection process in this present study, questions related to driving were excluded because driving is not an experience common to all adults. The US Department of Transportation reported that, in some states in the USA, up to 27% of adults of driving age did not hold a drivers license in 2005 (http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/ohim/hs05/htm/dl1c.htm accessed August 5, 2008). In the UK, for the same year, the UK government reported that 37% of women and 19% of men did not hold a driving license (http://www.statistics.gov.uk/cci/nugget.asp?id=1093 accessed August 5, 2008). In addition, legal restrictions for driving with diplopia vary considerably between countries; for example, in Canada driving is not permitted if diplopia occurs within the central 40 degrees (http://www.cma.ca/multimedia/CMA/Content_Images/Inside_cma/WhatWePublish/Drivers_Guide/Section11_e.pdf accessed August 5, 2008), whereas in the USA there are no restrictions regarding diplopia (http://www.icoph.org/standards/drivingapp2.html accessed August 5, 2008). Removing driving questions therefore makes the AS-20 more universally applicable. We removed questions related to ‘Work’ (mentioned by 65% of patients with diplopia and 54% of patients without diplopia during interviews13) for similar reasons, as they are not relevant to adults who are retired or unemployed. In contrast, reading is almost universal in developed countries; the US literacy rate has been estimated to be 99% (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/print/us.html accessed August 5, 2008).

The choice of items in each subscale was determined by factor analysis. Although two of the questions in the function sub-scale (‘I feel stressed about my eyes’ and ‘I worry about my eyes;’ Table 1) might ostensibly belong in the psychosocial sub-scale, factor analysis revealed strong correlation with the other questions that formed the function sub-scale. Even though our final questionnaire contained only 20 items there is likely to be some redundancy since the Cronbach’s alpha values exceeded 0.9 for the two sub-scales. Despite the possibility of some redundancy, the testing burden of 20 items is minimal and reliability is desirable.21

To evaluate the instrument’s discriminative validity, we compared AS-20 scores for strabismus patients with scores for visually normal adults and patients with other eye diseases. The questionnaire showed good discriminative validity, with significantly lower overall, psychosocial, and function scores (indicating worse HRQOL) for both diplopic and non-diplopic strabismus patients. While overall and sub-scale scores for patients with other eye diseases were significantly lower (indicating worse HRQOL) than scores for visually normal adults, they were still significantly higher than scores for strabismus patients, suggesting that the AS-20 targets HRQOL concerns pertinent to patients with strabismus rather than concerns of patients with other eye conditions. Consistent with the design of our questionnaire, there was a ceiling effect for visually normal adults, of whom a large proportion had the maximum score of 100 on the psychosocial and function sub-scales. Such ceiling effects may lead to reduced sensitivity when comparing those with strabismus to normals. Nevertheless, we designed our instrument to be used to compare those with varying degrees of, or changes in, strabismus.

One might have predicted that the concerns of patients with diplopia would primarily relate to function, but we also found high levels of psychosocial concerns in some patients with diplopia. For example, 11 (50%) of 22 patients with diplopia rated question 2, ‘I feel that people are thinking about my eyes even when they don’t say anything’ (Table 1), either ‘sometimes,’ ‘often,’ or ‘always.’ For some patients with diplopia, psychosocial concerns may be due to socially obtrusive, manifest strabismus; nevertheless, we found notable exceptions, e.g. a 53 year old male with an acquired 10 pd decompensated esotropia who had a median psychosocial subscale score of 38. We speculate that the presence of diplopia may cause a patient to feel self-conscious of misalignment even when the strabismus is not particularly noticeable.

For strabismus patients without diplopia, one might expect to find psychosocial concerns, but interestingly we also found a high level of function-related concerns. For example, of the 10 patients without diplopia, 6 (60%) responded either ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’ to question 20, ‘I need to take frequent breaks when reading because of my eyes’ (Table 1). Function-related HRQOL concerns in patients without diplopia were also reported in a study by Beauchamp et al,5 who found that some strabismic patients without diplopia rated difficulties with everyday tasks such as reading. Together with the data from our present study, these findings suggest that function-related HRQOL concerns may be prevalent in non-diplopic strabismus. Evidence of difficulties with everyday visual functioning may have important implications for the rehabilitation of non-diplopic strabismus in adults, and highlights the need for formal assessment of HRQOL in adult strabismus, using instruments such as the AS-20.

There are potential weaknesses to our current study. For both the development and testing phases of this study, we recruited consecutive eligible strabismus patients to select an unbiased sample. This sampling method resulted in a diverse range of strabismus diagnoses, but also resulted in a racially homogeneous study sample. It is possible that lack of racial heterogeneity may have influenced the selection of the final 20 items. Nevertheless, we considered cultural, social, economic, and educational factors, and we excluded items that may be discriminatory. Another potential weakness of our study is that some comparisons between patients with and without diplopia may not have reached statistical significance due to small sample size. In planned future studies, we will assess test-retest reliability of the AS-20 and responsiveness to treatment.

We have developed a patient-derived 20-item HRQOL questionnaire specifically for adults with strabismus, with sub-scales assessing psychosocial and function concerns (see online supplemental material for full questionnaire with instructions). We anticipate that the AS-20 will not only prove a valuable tool for assessing the impact of strabismus in an individual’s everyday life, but also for measuring outcomes from treatment in clinical practice and in clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY015799 (JMH), EY013844 (EAB), Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY (JMH as Olga Keith Weiss Scholar and an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology, Mayo Clinic), and Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN.

Footnotes

None of the funding organizations had any role in the design or conduct of this research.

No conflicting relationships exist.

References

- 1.Satterfield D, Keltner JL, Morrison TL. Psychosocial aspects of strabismus study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:1100–1105. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090080096024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke JP, Leach CM, Davis H. Psychosocial implications of strabismus surgery in adults. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1997;34:159–164. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19970501-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills MD, Coats DK, Donahue SP, Wheeler DT. Strabismus surgery for adults: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1255–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menon V, Saha J, Tandon R, et al. Study of the psychosocial aspects of strabismus. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2002;39:203–208. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-20020701-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beauchamp GR, Black BC, Coats DK, et al. The management of strabismus in adults--III. The effects on disability. J AAPOS. 2005;9:455–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson S, Harrad RA, Morris M, Rumsey N. The psychosocial benefits of corrective surgery for adults with strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:883–888. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.089516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Graaf ES, van der Sterre GW, Polling JR, et al. Amblyopia & Strabismus Questionnaire: design and initial validation. Strabismus. 2004;12:181–193. doi: 10.1080/09273970490491196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coats DK, Paysse EA, Towler AJ, Dipboye RL. Impact of large angle horizontal strabismus on ability to obtain employment. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:402–405. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olitsky SE, Sudesh S, Graziano A, et al. The negative psychosocial impact of strabismus in adults. J AAPOS. 1999;3:209–211. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(99)70004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:622–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patrick DL, Deyo RA. Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Med Care. 1989;27(suppl):S217–S232. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margolis MK, Coyne K, Kennedy-Martin T, et al. Vision-specific instruments for the assessment of health-related quality of life and visual functioning: a literature review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20:791–812. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200220120-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatt SR, Leske DA, Kirgis PA, et al. The effects of strabismus on quality of life in adults. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:643–647. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felius J, Beauchamp GR, Stager DR, Sr, et al. The Amblyopia and Strabismus Questionnaire: English translation, validation and subscales. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:305–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calman KC. Quality of life in cancer patients - an hypothesis. J Med Ethics. 1984;10:124–127. doi: 10.1136/jme.10.3.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guyatt GH, Bombardier C, Tugwell PX. Measuring disease-specific quality of life in clinical trials. CMAJ. 1986;134:889–895. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost NA, Sparrow JM, Durant JS, et al. Development of a questionnaire for the measurement of vision-related quality of life. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1998;5:182–210. doi: 10.1076/opep.5.4.185.4191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangione C, Lee P, Gutierrez P, et al. National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionniare Field Test Investigators. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1050–1058. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.7.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cole SR, Kawachi I, Maller SJ, Berkman LF. Test of item-response bias in the CES-D scale: experience from the New Haven EPESE study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:285–289. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fayers PM, Machin D. Quality of life: assessment, analysis, and interpretation. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.