Abstract

Salt-tolerant landscape plants are needed for arid and semiarid regions where the supply of quality water is limited and soil salinization often occurs. This study evaluated growth, chloride (Cl) and sodium (Na) uptake, relative chlorophyll content, and chlorophyll fluorescence of three rose rootstocks [Rosa ×fortuniana Lindl., R. multiflora Thunb., and R. odorata (Andr.) Sweet] irrigated with saline solutions at 1.6 (control), 3.0, 6.0, or 9.0 dS·m −1 electrical conductivity in a greenhouse. After 15 weeks, most plants in 9.0 dS·m −1 treatment died regardless of rootstock. Significant growth reduction was observed in all rootstocks at 6.0 dS·m −1 compared with the control and 3.0 dS·m −1, but the reduction in R. ×fortuniana was smaller than in the other two rootstocks. The visual scores of R. multiflora at 3.0 and 6.0 dS·m−1 were slightly lower than those of the other rootstocks. Rosa odorata had the highest shoot Na concentration followed by R. multiflora; however, R. multiflora had the highest root Na concentration followed by R. odorata. All rootstocks had higher Cl accumulation in all plant parts at elevated salinities, and no substantial differences in Cl concentrations in all plant parts existed among the rootstocks, except for leaf Cl concentration in R. multiflora, which was higher than those in the other two rootstocks. The elevated salinities of irrigation water reduced the relative chlorophyll concentration, measured as leaf SPAD readings, and maximal photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) and minimal fluorescence (F0)/maximum fluorescence (Fv/Fm), but the largest reduction in Fv/Fm was only 2.4%. Based on growth and visual quality, R. ×fortuniana was relatively more salt-tolerant than the other two rootstocks and R. odorata was slightly more salt-tolerant than R. multiflora.

Additional index words: garden rose, salinity tolerance, water reuse

The supply of high-quality water has become increasingly limited in many areas of the world, especially in arid and semiarid regions. With a rapid increase in the urban population, the intense competition for high-quality water among agriculture, industry, and recreational users has promoted the use of alternative water sources for irrigation. These sources include recycled water, treated effluents, and saline ground (well) waters that contain relatively high levels of soluble salts. Soil salinity is already a problem in arid and semiarid areas where irrigation is practiced. Over 50% of all irrigated lands are affected by salinity, yet the water used in these lands is seldom saline (Pasternak and Malach, 1994). Because low-quality water has been or will be used for irrigation as a result of limited supply of high-quality water, soil salinization will increase in these areas.

Rose (Rosa spp.) is one of the most economically important ornamental crops in the world. Rose has been traditionally categorized as a salt-sensitive species with salt injury reported within a range of 0.5 to 3 dS·m−1 electrical conductivity (EC) depending on species, cultural medium, leaching fraction, and environmental conditions (Urban, 2003). However, other researchers reported that yield and quality of roses did not decrease when irrigated with drainage recycled water at EC of 3.5 dS·m−1, provided that an appropriate rootstock and aerated medium were used (Cabrera, 2003; Raviv et al., 1998). Although a certain amount of information on salt tolerance is available for greenhouse cut roses (Bernstein et al., 2006; Cabrera, 2003; de Vries, 2003; Fernandez Falcon et al., 1986; Hughes and Hanan, 1978; Wahome et al., 2001), little research has been conducted on garden roses.

Most garden roses are produced by grafting using the T-budding technique (Pemberton, 2003). Different rootstocks are used in various areas in the world in accordance with climatic and soil conditions. For example, R. multiflora is used in the south–central United States, Canada, and Japan (Pemberton, 2003) and is the most popular rose rootstock in Scandinavia (Stougaard, 1984), where R. ×fortuniana is used in areas with year-round temperate climate (Morrell, 1983). In the United States, R. ×fortuniana is mainly used in Florida and in the southwestern region (Martin, 2008). Rosa odorata is one of the most popular rose rootstocks for greenhouse cut flower, but is also used for garden roses (Cabrera, 2002; Singh and Chitkara, 1982, 1987).

The vigor and yield of flower production of the grafted plants are affected by rootstock selection (Pivetta et al., 2004). Wang (1992) found that R. × ‘Queen Elizabeth’ budded onto R. odorata had a much higher survival rate than when budded onto R. multiflora after several years in an alkaline soil and irrigated with moderately saline water in a hot subtropical climate. Similarly, salt tolerance of grafted or budded plants is affected by rootstock selection in many woody plants (Cid et al., 1989). The salt tolerance of ‘Bridal White’ roses was relatively high when grafted onto R. manetti and R. × ‘Natal Brial’ compared with R. odorata (i.e., R. indica ‘Major’), R. multiflora ‘Rum 9’, and R. × ‘Dr. Huey’ (Cabrera, 2003). The root-stock–scion relationship may affect the response of the grafted or budded plants to salinity. However, the relative salt tolerance of these rootstocks alone (without grafting) remains unknown. The objectives of this study were: 1) to investigate the relative salt tolerance of three rose rootstocks, R. ×fortuniana, R. multiflora, and R. odorata, by comparing the responses of growth, ion uptake, relative chlorophyll concentration, and chlorophyll fluorescence of these rose rootstocks to a range of salinity of irrigation water; and 2) to understand the general mechanism of salt tolerance.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and culture

Unrooted cuttings of R. ×fortuniana, R. multiflora, and R. odorata were received from a commercial company on 22 June 2006 and were treated with Hormex (Brooker Chemical Corp., Chatsworth, CA) at 3000 mg·L−1 indole-3-butyric acid before being inserted into a 1:1 (by volume) rooting mix of coarse perlite and Sunshine Mix No. 4 (SunGro Hort., Bellevue, WA). Rooted cuttings were transplanted on 11 Aug. to 1.8-L round plastic pots containing a 1:1 mix (by volume) of Sunshine Mix No. 4 and composted mulch (Western Organics, Inc., Tempe, AZ). Plants were grown in a greenhouse from August to the end of October and irrigated with a nutrient solution containing 0.5 g·L−1 of 20N–8.6P–16.7K (Peters 20–20–20; Scotts, Allentown, PA). All plants were pruned to two shoots and uniform heights before treatment initiation. During the experimental period, the average air temperature in the greenhouse was 21 ± 2.0 °C during the day and 17 ± 1.5 °C at night. The average daily light integral (photosynthetically active radiation) was 12.0 ± 1.2 mol·m−2·d−1. The instantaneous light intensity was measured by a quantum sensor (Model QSO-SUN; Apogee Instruments, Logan, UT) and the hourly average was recorded by a 21X data logger (Campbell Scientific, Logan, UT).

Treatments

Saline solutions were prepared by adding sodium chloride (NaCl), magnesium sulfate (MgSO4·7H2O), and calcium chloride (CaCl2) at 87%, 8%, and 5%, respectively, on a weight basis to a nutrient solution. The nutrient solution was made by adding 0.5 g·L−1 of 20N–8.6P–16.7K (Peters 20–20–20; Scotts) to tap water. The major ions in the tap water were Na, Ca, Mg, CI, and SO4 at 184, 52.0, 7.5, 223.6, and 105.6 mg·L−1, respectively. The composition of the treatment saline solutions was similar to that of the reclaimed municipal effluent of the local water utilities. Four salinity levels, EC at 1.6 (nutrient solution, control), 3.0, 6.0, or 9.0 dS·m−1, were created. A 100-L tank of saline solution was prepared each time with confirmed EC for each treatment. The saline solution irrigation was initiated on 1 Nov. 2006 and ended on 15 Feb. 2007 (15 weeks). Rootstocks were randomly placed on greenhouse benches. Plants were irrigated manually with 600 mL treatment solution for all plants in the same treatment, which resulted in a leaching fraction of ≈45%, when the substrate surface started to dry to avoid water stress and overwatering. Irrigation frequency varied with climate, growth stage (biomass), and treatment. All plants were pruned on 13 Dec. to uniform heights when shoots were over 35 cm long and the pruned fresh weights were recorded in the greenhouse immediately.

Measurement

Visual foliar salt damage was assessed on all plants at the end of the experiment. Each plant was given a score of 1 to 5, in which 1 = over 50% foliar damage (salt damage: burning and discoloring) or dead; 2 = moderate (25% to 50%) foliar damage; 3 = slight (less than 25%) foliage damage; 4 = good quality with acceptable growth reduction and little foliar damage (acceptable as landscape performance); and 5 = excellent with no foliar damage.

Leaf greenness or relative chlorophyll concentration (measured as the optical density, SPAD reading) was recorded at the end of the experiment on three leaves per plant at similar middle positions of shoots for all plants in each treatment using a portable SPAD chlorophyll meter (Minolta Camera Co., Osaka, Japan). Although SPAD readings do not give an absolute measure of chlorophyll concentration, they do provide a useful relative index, which is closely related to leaf chlorophyll concentration (Markwell et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2005).

Leaf osmotic potential (ψs) was determined according to Ball and Oosterhuis (2005). Specifically, leaves were sampled from the middle section of the shoots in the early morning at the end of the experiment, sealed in a plastic bag, and immediately stored in a freezer until analysis. Frozen leaves were thawed in a plastic bag at room temperature before sap was pressed with a Markhart leaf press (LP-27; Wescor, Logan, UT) and analyzed using a vapor pressure osmometer (Vapro Model 5520; Wescor). Osmometer readings (mmol·kg−1) were converted to MPa using the van’t Hoff equation at 25 °C (Nobel, 1991).

To examine the influence of increased salinity on leaf photosynthetic apparatus among the rootstocks, leaf chlorophyll fluorescence values, minimal fluorescence (Fo), maximum fluorescence (Fm), and the maximal photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) (Fv/Fm, Fv = Fm − Fo) were measured in the morning on young, fully expanded leaves 1 week before the end of the experiment using a Plant Efficiency Analyzer (Hansatech Instruments Ltd., Kings Lynn, UK). Before measuring, the leaves were dark-adapted for 10 min by attaching to the light-exclusion clips.

At the end of the experiment, leaf and stem fresh weights were determined by severing the main stem at the substrate surface and separating the leaves and stems. Roots were washed free of substrate and fresh weights were recorded. Leaves, stems, and roots were oven-dried at 70 °C to constant weights and dry weights (DW) were determined. To monitor the root zone salinity, leachate was collected every 2 to 3 weeks during the experiment on three containers per treatment per rootstock. The EC of leachate was determined using a salinity meter (Model B-173; Horiba, Ltd., Kyoto, Japan).

To analyze sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl) concentrations, three of the 10 samples of roots, stems, and leaves per treatment were randomly selected. Dried tissue was ground with a stainless Wiley mill and the samples were submitted to the Soil, Water, and Air Testing laboratory (Las Cruces, NM) for Na and Cl analyses. Na concentrations were determined by EPA method 200.7 [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, 1983)] and analyzed on an ICAP Trace Analyzer (Thermo Jarrell Ash, Franklin, MA). Cl was determined by EPA method 300.0 (U.S. EPA, 1983) and analyzed using an ion chromatograph (Dionex, Sunnyville, CA).

Experimental design and data analysis

The experiment was a split-plot design with the salinity of the irrigation water as the main plot and rootstock as subplots with 10 replications. All data were analyzed by a two-way analysis of variance using PROC GLM. When main effect (the salinity of irrigation) was significant, linear or quadratic regression was calculated using PROC REG. When the interaction between the salinity of irrigation water and rootstock was not significant, data were pooled across salinity treatments or rootstock. The effect of rootstock was analyzed by Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison at P = 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.1.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results and Discussion

Survival rate, visual score, pruned fresh weight, and leachate electrical conductivity

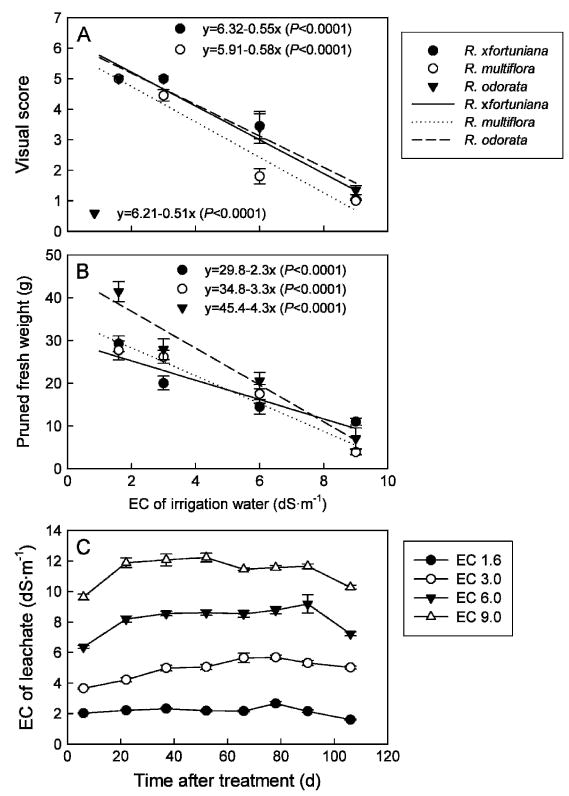

All plants survived at 3.0 dS·m−1 and in the control (1.6 dS·m−1)regardless of rootstock (data not shown). The survival rates of R. ×fortuniana, R. multiflora, and R. odorata were 60%, 60%, and 80% at 6.0 dS·m−1 and 10%, 0%, and 30% at 9.0 dS·m−1, respectively. All rootstocks in the control had an excellent score without visible foliar salt damage (Fig. 1A). At 3.0 dS·nr−1, a few plants of R. multiflora had slight salt damage on lower leaves. The foliar salt damage became more severe as salinity of the irrigation water increased. Similar salt damage symptoms were observed on lower leaves of R. odorata in the 6.0 dS·m−1 and 9.0 dS·m−1 treatments as early as 3 weeks after the treatment initiation. However, the survival rate of this rootstock was slightly higher than the other two rootstocks at the end of the experiment. Rosa multiflora had lower visual scores than the other two rootstocks at 3.0 and 6.0 dS·m−1. The pruned fresh weight decreased linearly as salinity of the irrigation water increased with sharper reduction slope in R. odorata compared with the other two rootstocks (Fig. 1B). The significant reductions in pruned fresh weights at elevated salinities indicate the early negative effect of salinity treatments on these rootstocks.

Fig. 1.

Visual quality (A) and pruned fresh weight (B) in the middle of the experiment of rose rootstocks Rosa ×fortuniana, R. multiflora, and R. odorata grown in the greenhouse irrigated with saline solutions at various salinities for 15 weeks and (C) the time course of electrical conductivity (EC) of leachate during the experiment. Vertical bars indicate SES.

Rootstock did not affect leachate EC. Therefore, data were pooled across rootstocks (Fig. 1C). The leachate EC was 0.5 to 3.0 dS·m−1 higher than that of the irrigation solutions 3 weeks after the initiation of treatment and were stable during the experiment, possibly as a result of the high leaching fraction and well-aerated substrate that prevented excessive salt accumulation. In addition to leaching fraction, type of substrate affected leachate EC when plants were irrigated with saline solutions (Bernstein et al., 2006; Niu and Rodriguez, 2006a). Lower leaching fraction and poor-aerated substrate such as peat-based substrate led to salt accumulation in root zones.

Final growth

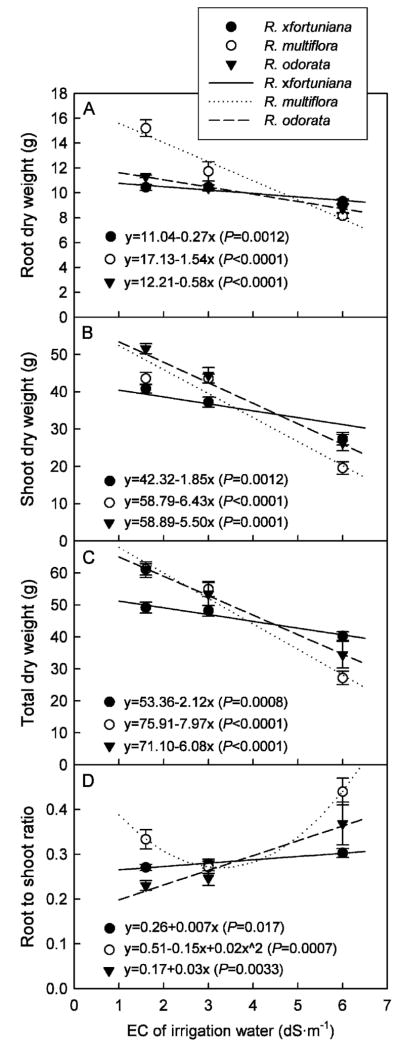

There were interactive effects of salinity and rootstock on DW of shoots and roots and root to shoot ratio, indicating that plant growth responses to salinity differed among rootstocks. Because most plants did not survive at 9.0 dS·m−1, this treatment was excluded in data analysis. DW of roots, shoots, and total decreased linearly with salinity of the irrigation water in all rootstocks (Fig. 2A–C). Total DW decreased by 18%, 44%, and 56% and shoot DW decreased by 33%, 49%, and 55% in R. ×fortuniana, R. odorata, and R. multiflora, respectively, when the salinity of the irrigation water increased from 1.6 to 6.0 dS·m−1. The shoot DW of R. multiflora was similar at 1.6 and 3.0 dS·m−1. The reductions in DW of roots, shoots, and total were lowest in R. ×fortuniana and highest in R. multiflora at elevated salinities.

Fig. 2.

Dry weight of roots (A), shoots (B), and total (C), and root to shoot ratio (D) of rose rootstocks Rosa ×fortuniana, R. multiflora, and R. odorata grown in the greenhouse irrigated with saline solutions at various salinities for 15 weeks. Vertical bars indicate SES.

Root to shoot ratio increased linearly in R. ×fortuniana and R. odorata and quadratically in R. multiflora as salinity of the irrigation water increased (Fig. 2D). Root to shoot ratio increased by 11% and 60% in R. ×fortuniana and R. odorata, respectively, when salinity of the irrigation water increased from 1.6 to 6.0 dS·m−1. The increased salinity of irrigation water resulted in more growth reduction in shoots than in roots in R. ×fortuniana and R. odorata. Root to shoot ratio in R. multiflora was lowest at 3.0 dS·m−1 and highest at 6.0 dS·m−1. This suggests that R. multiflora grew better shoots at 3.0 dS·m−1.

Plants typically respond to salinity stress by reduced shoot and root growth with shoot growth reduction occurring earlier (Munns, 2002). Most crops tolerate salinity up to a threshold level above which growth or yield decreases as salinity increases (Maas, 1986). This threshold varies with species (Pasternak and Malach, 1994). In this study, R. ×fortuniana had smaller growth reduction in roots and shoots compared with R. multiflora and R. odorata at elevated salinities. Bernstein et al. (2006) reported that growth and cut flower yield did not decrease for R. hybrida ‘Long Mercedes’ grafted on the rootstock R. indica when irrigated with treated wastewater at EC of 2.5 dS·m−1 (leachate EC up to 3.5 dS·m−1). As the salinity of irrigation water increased, visible foliar salt damage occurred in rose rootstocks R. chinensis ‘Major’ and R. rubiginosa (Wahome et al., 2001), herbaceous perennials (Niu and Rodriguez, 2006a, 2006b), and woody shrubs (Wu et al., 2001) in addition to reducing growth. Similarly, we observed foliar damage in all rootstocks at 6.0 and 9.0 dS·m−1 with more severe damage in R. multiflora at 3.0 and 6.0 dS·m−1 compared with the other two rootstocks. For landscape ornamental plants, visual quality is more important than maximum growth. Based on growth and visual quality, R. ×fortuniana was more tolerant to salinity followed by R. odorata.

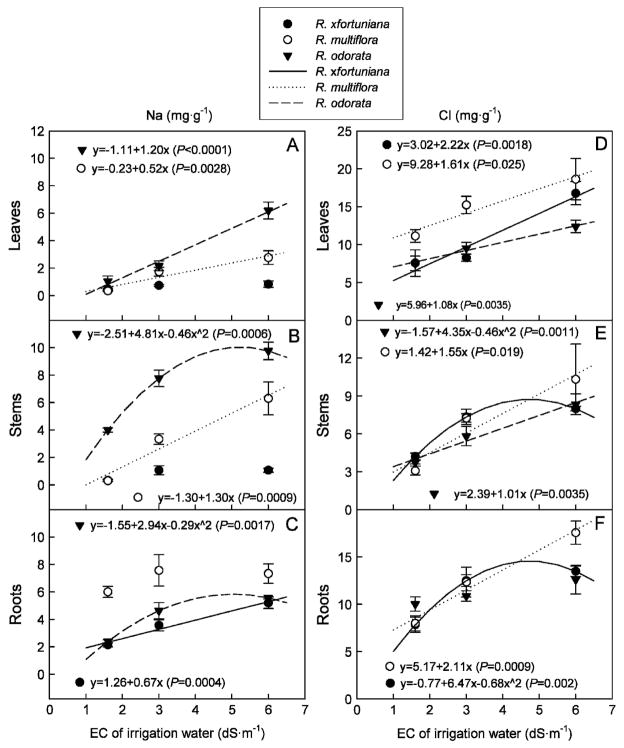

Sodium and chloride uptake

There were interactive effects of salinity of the irrigation water and rootstock on tissue Na and Cl concentrations, indicating that salinity effect on Na and Cl uptake varied with rootstock. In R. ×fortuniana, no differences in Na concentrations in stems and leaves were found among the salinity treatments (Fig. 3A–B). However, root Na concentrations increased linearly with salinity of the irrigation water in R. ×fortuniana (Fig. 3C). In R. multiflora, leaf and stem Na concentrations increased linearly with salinity of the irrigation water (Fig. 3A–B). Leaf Na concentration in R. odorata increased linearly; Na concentrations at 3.0 and 6.0 dS·m−1 increased by 117% and 520%, respectively compared with that at 1.6 dS·m−1. Stem and root Na concentration in R. odorata increased quadratically as salinity of the irrigation water increased. Root Na concentrations in R. multiflora were one to two times higher than those in R. ×fortuniana and R. odorata. However, stem Na concentrations in R. odorata were 1.5 to 10 times higher than those in R. multiflora across the treatments. Also, leaf Na concentration in R. odorata at 6.0 dS·m−1 was 2.2 times that in R. multiflora.

Fig. 3.

Sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl) concentrations leaves (A, D), stems (B, E) and roots (C, F) of three rose rootstocks, Rosa ×fortuniana, R. multiflora, and R. odorata grown, in the greenhouse irrigated with saline solutions at various salinities for 15 weeks. Vertical bars indicate SES.

The concentrations of Cl in plant tissue were much higher than those of Na (Fig. 3D– F). In R. ×fortuniana, leaf Cl concentration increased linearly, and Cl concentrations in stems and roots increased quadratically as salinity of the irrigation water increased. In R. multiflora and R. odorata, Cl concentrations in leaves, stems, and roots increased linearly with increasing salinity of the irrigation water. In leaves, Cl concentrations were higher in R. multiflora than in the other two rootstocks in all treatments. There were no substantial differences in Cl concentrations in stems in all treatments among the three rootstocks. However, Cl concentrations in roots at 6.0 dS·m−1 was higher in R. multiflora than in the other two rootstocks.

Minimizing the entry of salt in plant (salt exclusion) is an important mechanism of salt tolerance (Munns, 2002). In this study, R. ×fortuniana had higher Na exclusion ability than R. multiflora and R. odorata evidenced by lower Na concentrations in stems and leaves. Rosa multiflora had higher ability than R. odorata to restrict Na transport from roots to shoots. However, R. multiflora had higher tissue Cl concentrations, especially in the leaves, than the other two rootstocks, which may be the cause of lower visual scores. Wahome et al. (2001) compared the mechanisms of salt tolerance of two rose rootstocks: R. chinensis ‘Major’ and R. rubiginosa. They found that the lower leaves of less salt-tolerant R. chinensis ‘Major’ had higher Na concentration than in all other parts, whereas R. rubiginosa had higher concentrations of Na in the roots than in all other parts. Wu et al. (2001) also reported that salt-tolerant ornamental shrubs tended to accumulate less Na and Cl in leaves than salt-sensitive plants. Restriction of the uptake of Cl and Na in the roots and retaining these ions in roots thereby preventing the accumulation of these ions in stems and leaves are important mechanisms of salt tolerance. Selection of rose rootstocks affects the salt tolerance of grafted plants (Cabrera, 2003). The accumulation of Na and Cl in leaves of scions is affected by rootstock selection (Cabrera, 2003). For example, the leaf Cl concentrations of ‘Bridal White’ plants grafted on R. odorata and R. multiflora ‘Rum 9’ were 1.5 times higher than in the other rootstocks (Cabrera, 2003).

Physiological response

There was no interactive effect between salinity and rootstock on leaf ψs. Also, there were no differences in leaf ψs among rootstocks. Therefore, data were pooled across rootstocks. The leaf ψs at the end of the experiment were −1.6 MPa, −1.9 MPa, and −2.0 MPa for the control, 3.0 dS·m−1, and 6.0 dS·m−1, respectively (data not shown). No statistical differences in leaf ψs were found between the control and 3.0 dS·m−1 or between 3.0 and 6.0 dS·m−1. However, leaf ψs in 6.0 dS·m−1 was higher than that in the control, possibly as a result of the accumulation of Na and Cl in leaves. Accumulation of Na and Cl in plant tissues under salinity has been associated with osmotic adaptation (Heuer and Nadler, 1998; Pardossi et al., 1999) and improvement of water status in Vaccinium ashei Rehd. (Wright et al., 1995) and Pistacia spp. (Picchioni and Miyamoto, 1990).

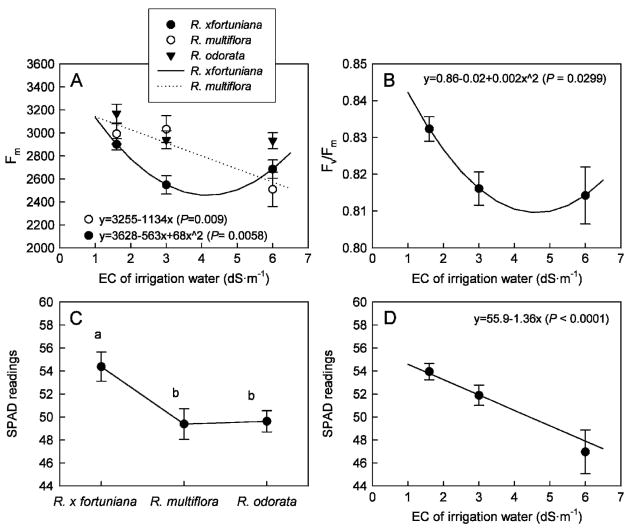

Salinity and rootstock interactively affected Fm but not Fv/Fm. For R. ×fortuniana, Fm decreased quadratically and was ≈10% higher in the control than those at 3.0 and 6.0 dS·m−1 (Fig. 4A). In R. multiflora, Fm decreased linearly as salinity of the irrigation water increased and Fm in R. odorata did not change with salinity of the irrigation water. There was no difference in Fv/Fm among rootstocks (Fig. 4B). Although, Fv/Fm decreased quadratically as salinity of the irrigation water increased, the reduction was only 2.4% at 3.0 and 6.0 dS·m−1 compared with that in the control. Photochemical damage is reflected in either an increase in Fo or decreases in Fm or Fv/Fm (Thomas and Turner, 2001). In this study, we did observe decreases in Fm and Fv/Fm resulting from elevated salinities, but the magnitude is rather small, especially in Fv/Fm.

Fig. 4.

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, maximum fluorescence (Fm) (A), maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) (B), and leaf SPAD readings (C, D) of three rose rootstocks, Rosa ×fortuniana, R. multiflora, and R. odorata, grown in the greenhouse irrigated with saline solutions at various salinities for 15 weeks. Vertical bars indicate SES.

There was no interactive effect on leaf SPAD readings between salinity and root-stock. Rosa ×fortuniana had higher leaf SPAD readings compared with the other two rootstocks, indicating that R. ×fortuniana had greener leaves (Fig. 4C), which agreed with visual observation. Also, SPAD readings were lower at 6.0 dS·m−1 compared with 1.6 and 3.0 dS·m−1 (Fig. 4D). Leaf discoloration is one of the typical initial foliar salt damage symptoms (Devitt et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2001), which may be reflected by decreased SPAD readings. This is in agreement with our previous study in which leaf SPAD readings were reduced by elevated salinity of irrigation water in some of the herbaceous species (Niu et al., 2007). Although no relationships between chlorophyll concentrations and SPAD readings for these rose species have been previously established, measuring leaf SPAD readings have been shown to be an efficient method to rapidly and nondestructively quantify the initial or mild salt damage in tomato (Montesano and van Iersel, 2007) and cherry rootstocks (Sotiropoulos et al., 2006).

It is important to note that the results of the relative salt tolerance of the three rose rootstocks obtained from this study may be used as a reference for selecting rose rootstocks. The salinity threshold for acceptable performance when grown in the field or in seasons other than winter needs to be confirmed, because plant response to salinity may be altered by factors such as climate, substrate, or soil conditions and irrigation. Also, further research is needed to investigate if the relative salt tolerance of the scions grafted or budded onto these rose rootstocks would be consistent with that obtained in this study.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture under Agreement No. 2005-34461-15661, the MBRS-RISE Program at EPCC, Grant No. R25 GM060424, El Paso Water Utilities, and Texas Agricultural Experiment Station. We also thank Jackson & Perkins Wholesale for donating the plant materials.

Contributor Information

Genhua Niu, Texas AgriLife Research and Extension Center at El Paso, Texas A&M University, 1380 A&M Circle, El Paso, TX 79927.

Denise S. Rodriguez, Texas AgriLife Research and Extension Center at El Paso, Texas A&M University, 1380 A&M Circle, El Paso, TX 79927

Lissie Aguiniga, El Paso Community College, Research Initiative for Scientific Enhancement Program, El Paso, TX 79925.

Literature Cited

- Ball RA, Oosterhuis DM. Measurement of root and leaf osmotic potential using the vapor-pressure osmometer. Environ Exp Bot. 2005;53:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein N, Asher BT, Haya F, Pini S, Ilona R, Amram C, Marina I. Application of treated wastewater for cultivation of roses (Rosa hybrida) in soil-less culture. Scientia Hort. 2006;108:185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera RI. Rose yield, dry matter partitioning and nutrient status responses to rootstock selection. Scientia Hort. 2002;95:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera RI. Demarcating salinity tolerance in greenhouse roses. Acta Hort. 2003;609:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cid MC, Caballero M, Reimann-Philipp R. Rose rootstock breeding for salinity tolerance. Acta Hort. 1989;246:345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Devitt DA, Morris RL, Fenstermaker LK. Foliar damage, spectral reflectance, and tissue ion concentrations of trees sprinkle irrigated with waters of similar salinity but different chemical composition. HortScience. 2005;40:819–826. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries DP. Rootstock. In: Robert AV, Debener T, Gudin S, editors. Encyclopedia of rose science. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2003. pp. 633–638. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Falcon M, Alvarez Gonzalez CE, Garcia V, Baez J. The effect of chloride and bicarbonate levels in the irrigation water on nutrient content, production and quality of cut roses ‘Mecedes’. Scientia Hort. 1986;29:373–385. [Google Scholar]

- Heuer B, Nadler A. Physiological responses of potato plants to soil salinity and water deficit. Plant Sci. 1998;137:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes H, Hanan J. Effect of salinity in water supplies on greenhouse rose production. J Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1978;103:694–699. [Google Scholar]

- Maas EV. Salt tolerance of plants. Appl Agr Res. 1986;1:12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Markwell J, Osterman JC, Mitchell JL. Calibration of the SPAD-502 leaf chlorophyll meter. Photosynth Res. 1995;46:467–472. doi: 10.1007/BF00032301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. An overview of Rosa fortuniana rootstock. Pacific Southwest District of the American Rose Society; 2008. Jan. 2008. < http://www.pswdistrict.org/text/articles/rosaFortunianaRootstock.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Montesano F, van Iersel M. Calcium can prevent toxic effects of Na+ on tomato leaf photosynthesis but does not restore growth. J Amer Soc Hort Sci. 2007;132:310–318. [Google Scholar]

- Morrel DL. The roots of fortuniana (R. ×fortuniana) The American Rose Annual. 1983:55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Munns R. Comparative physiology of salt and water stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2002:239–250. doi: 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu G, Rodriguez DS. Relative salt tolerance of five herbaceous perennials. Hort-Science. 2006a;41:1493–1497. [Google Scholar]

- Niu G, Rodriguez DS. Relative salt tolerance of selected herbaceous perennials and groundcovers. Scientia Hort. 2006b;110:352–358. [Google Scholar]

- Niu G, Rodriguez DS, Aguiniga L. Growth and landscape performance of ten herbaceous species in response to saline water irrigation. J Environ Hort. 2007;25:204–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobel PS. Physiochemical and environmental plant physiology. Academic Press Inc; San Diego, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pardossi A, Malorgio F, Tognomi F. Salt tolerance and mineral relations for celery. J Plant Nutr. 1999;22:151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak D, Malach YD. Crop irrigation with saline water. In: Pessarakli M, editor. Handbook of plant and crop stress. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY: 1994. pp. 599–622. [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton HB. Overview of roses and culture. In: Robert AV, Debener T, Gudin S, editors. Encyclopedia of rose science. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2003. pp. 570–573. [Google Scholar]

- Picchioni GA, Miyamoto S. Salt effects on growth and ion uptake of Pistacia rootstock seedlings. J Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1990;115:647–653. [Google Scholar]

- Pivetta KFL, Pizetta PUC, Pedrinho DR. Morphologic characterization and evaluation of the productivity of nine rootstocks of rose bush (Rosa spp.) Acta Hort. 2004;630:213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Raviv M, Krasnovsky A, Medina S, Reuveni R. Assessment of various control strategies for recirculation of greenhouse effluents under semi-arid conditions. J Hort Sci Biotechnol. 1998;73:485–491. [Google Scholar]

- Singh BP, Chitkara SD. Effect of different salinity and sodicity levels on establishment and bud take performance of various rose rootstocks. Haryana J Hort Sci. 1982;11:204–207. [Google Scholar]

- Singh BP, Chitkara SD. Effect of different salinity levels on water potential and proline content in leaves of various rose rootstocks. Indian J Hort. 1987;44:265–267. [Google Scholar]

- Sotiropoulos TE, I, Therios N, Almaliotis D, Papadakis I, Dimassi KN. Response of cherry rootstocks to boron and salinity. J Plant Nutr. 2006;29:1691–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Stougaard B. Analysis of variation in progeny from Rosa multiflora crosses. Tidsskrift for Planteavl. 1984;88:287–297. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DS, Turner DW. Banana (Musa sp.) leaf gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence in response to soil drought, shading and lamina folding. Scientia Hort. 2001;90:93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Urban I. Influences of abiotic factors in growth and development. In: Robert AV, Debener T, Gudin S, editors. Encyclopedia of rose science. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2003. pp. 369–374. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Methods of chemical analysis of water and wastes (EPA-600/4-79-020) U.S. Gov. Print. Office; Washington, DC: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Wahome PK, Jesch HH, Grittner I. Mechanisms of salt stress tolerance in two rose rootstocks: Rosa chinensis ‘Major’ and R. rubiginosa. Scientia Hort. 2001;87:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Chen J, Stamps RH, Li Y. Correlation of visual quality grading and SPAD reading of green-leaved foliage plants. J Plant Nutr. 2005;28:1215–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Wang YT. A new rootstock and container size affect propagation and subsequent growth of rose bushes in an alkaline soil. HortScience. 1992;27:607. [Google Scholar]

- Wright GC, Patten KD, Drew MC. Labeled sodium (22Na+) uptake and translocation in rabbiteye blueberry exposed to sodium chloride and supplemental calcium. J Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1995;120:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Guo X, Harivandi A. Salt tolerance and salt accumulation of landscape plants irrigated by sprinkler and drip irrigation systems. J Plant Nutr. 2001;24:1473–1490. [Google Scholar]