Abstract

Purpose

To examine correlates of early initiation into sex work in two Mexico–U.S. border cities.

Methods

Female sex workers (FSWs) ≥18 years without known HIV infection living in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez who had recent unprotected sex with clients underwent baseline interviews. Correlates of initiation into sex work before age 18 were identified with logistic regression.

Results

Of 920 FSWs interviewed in Tijuana (N=474) and Ciudad Juarez (N=446), 9.8% (N=90) were early initiators (<18 years) into sex work. Median age of entry into sex work was 26 years (range: 6–58). After adjusting for age, compared to older initiators, early initiators were more likely to use inhalants (21.1% vs 9.6%, p=0.002), initiate sex work to pay for alcohol (36.7% vs 18.4%, p<.001), report abuse as a child (42.2% vs 18.7%, p<.0001), and they were less likely to be migrants (47.8% vs 62.3%, p=0.02). Factors independently associated with early initiation included inhalant use (adjOR=2.39), initiating sex work to pay for alcohol (adjOR=1.88) and history of child abuse (adjOR=2.92). Factors associated with later initiation included less education (adjOR=0.43 per 5-year increase), migration (adjOR=0.47), and initiating sex work for better pay (adjOR=0.44) or to support children (adjOR=0.03).

Conclusions

Different pathways for entering sex work are apparent among younger versus older females in the Mexico–U.S. border region. Among girls, interventions are needed to prevent inhalant use and child abuse and to offer coping skills; among older initiators, income-generating strategies, childcare, and services for migrants may help to delay or prevent entry into sex work.

Keywords: Female Sex Workers, Prostitution, Drug Use, Migration, Abuse

INTRODUCTION

Most major cities in Mexico have developed zonas de tolerancia (zones of tolerance) where sex work is quasi-legal and, in some cases, regulated. Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez are cities along the Mexico–U.S. border with large populations of female sex workers (FSWs). In 2006, it was reported that 4,850 FSWs were registered with the Municipal Health Service in Tijuana, while thousands of other FSWs were thought to work without permits [1]. Approximately 4,000 FSWs work in zones of tolerance in Ciudad Juarez [1]. Unlike Tijuana, Ciudad Juarez does not regulate sex work. In both cities, FSWs work in cantinas, bars, hotels, nightclubs, massage parlors, and on street corners.

The legal age of consent for sexual intercourse in Mexico is 18 years, yet underage sex workers are common. FSWs are vulnerable to sexually transmitted infections (STIs), unwanted pregnancy, and physical, psychological, and emotional abuse [2]. A review of child prostitution in Thailand reported detrimental physical and emotional effects and high risk for STIs, malnutrition, mental illness, substance abuse, complicated pregnancy, backstreet abortions, and violence [3]. Due to such complicating factors as human trafficking, safety concerns, ethical issues surrounding research on emancipated minors, and the clandestine nature of sex work, there are very few studies on young girls engaged in sex work [4]. Therefore, studies examining the factors that influence initiation into sex work often rely on retrospective analyses among current FSWs.

Several studies have reported associations between substance use and initiation into sex work. For example, crack use among migrants in Southern Florida was associated with entry into prostitution [5]. In a Danish study, early use of heroin and cocaine was a predictor for initiating prostitution [6]. Among US street youth, “survival sex” was strongly associated with recent substance use and lifetime injection drug use [7].

Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez are situated on major trafficking routes for heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine [8]. Among a sample of FSWs in these cities, 18% reported ever injecting drugs such as heroin, cocaine or methamphetamine, alone or in combination [9]. In an earlier study conducted in Ciudad Juarez among 75 FSWs, 59% were currently using drugs, and of those, 36% had initiated illicit drug use prior to entry into sex work, and half were injection drug users [10]. To date, studies have not established whether specific drugs are more commonly used by women who are beginning sex work or whether specific drug types are associated with initiating sex work at earlier ages.

Initiation into sex work has also been linked to childhood sexual, emotional, and physical abuse, including forced sex, domestic violence, and childhood sexual victimization [6, 7, 11, 12]. Among 1196 children processed in a criminal court in an unnamed U.S. city, early childhood abuse or neglect and sexual abuse were significantly associated with subsequent initiation into sex work. Physical abuse was marginally associated with entry into sex work as well [12]. Among homeless women and street youth in New York City, early sexual abuse was significantly associated with entry into prostitution [11].

Migration has also been linked to entry into sex work among women, and migration supplies workers for the sexual tourism industry in countries such as South Africa, China, and Thailand [13–15]. In China, the prevalence of casual and commercial sex among female temporary migrants was several-fold higher compared to female non-migrants [14]. Rural-to-urban migration in the developing world exposes migrant laborers to long absences from home, family breakdown, increased numbers of sexual partners, and sexual abuse [13, 16]. In Mexico, migration is associated with acquisition of HIV and other STIs [17]. The Mexico–U.S. border region attracts migrants from throughout Mexico and Central America who seek employment in foreign-owned maquiladoras or jobs in the U.S. [18]. Baja California and Chihuahua remain popular destinations for Mexico’s internal migrants, possibly because of the tourism and manufacturing industries in those states, which increasingly employ women as well as young men [19].

Half of Baja California’s population lives in Tijuana, and 8.2% of the state’s population have migrated from other parts of Mexico in the last five years [20]. Ciudad Juarez is home to one-third of Chihuahua’s population, and 3% of Chihuahua’s population has migrated from other parts of Mexico within the last five years [20]. Young women who lack local social networks may be particularly vulnerable to becoming sex workers. A study of FSWs in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez found that only 21% to 30% had been born in the city where they now work [21]. The association between entry into sex work and migration within Mexico has not yet been examined.

We cannot disregard that some of the FSW on these border region could be victims of human trafficking. The United Nations estimates that human trafficking is the third largest source of income for organized crime, after arms and drugs [22]. Worldwide, 800,000 to 900,000 people are trafficked across international borders each year, of whom 17,500 to 18,500 cross U.S. borders [23]. It is estimated that 80% of victims are women and girls, 70% are forced into sexual servitude, and up to 50% are minors [24].

Studies examining sex work initiation among the large population of FSWs in the Mexico–U.S. border region are lacking. Drug use, history of abuse, and migration may all play a role in sex work initiation; however, it is unclear if they affect initiation into sex work at younger ages. We hypothesized that pathways into sex work might differ for girls and younger women versus older women because of the additional legal barriers to sex work for women under 18.

METHODS

Study Population

As described elsewhere [25], FSWs were recruited at municipal clinics, through personal referrals, NGOs, or using street outreach. For this analysis, we used data from baseline assessments in Tijuana (N=474) and Ciudad Juarez (N=450), which occurred between March 2004 and March 2006. Eligible participants were women 18 years or older who self-identified as FSWs (having traded sex for drugs, money, or other material benefit), reported unprotected vaginal or anal sex with a client at least once during the previous four weeks, and reported being HIV-negative. Women were excluded if they practiced consistent use of condoms or a dental dam with all clients during the previous two weeks or if they had worked as a sex worker for less than 4 weeks.

Data Collection

Data were collected during a private, 45-minute interview. Areas examined by the questionnaire were: i) sociodemographics; ii) factors influencing initiation into sex work; iii) drug use before initiating sex work; and iv) experiences of abuse before initiating sex work.

Sociodemographics

These data included age, years working as a FSW, marital status, living situation, number of children, and migrant status.

Influences for Entering Sex Work

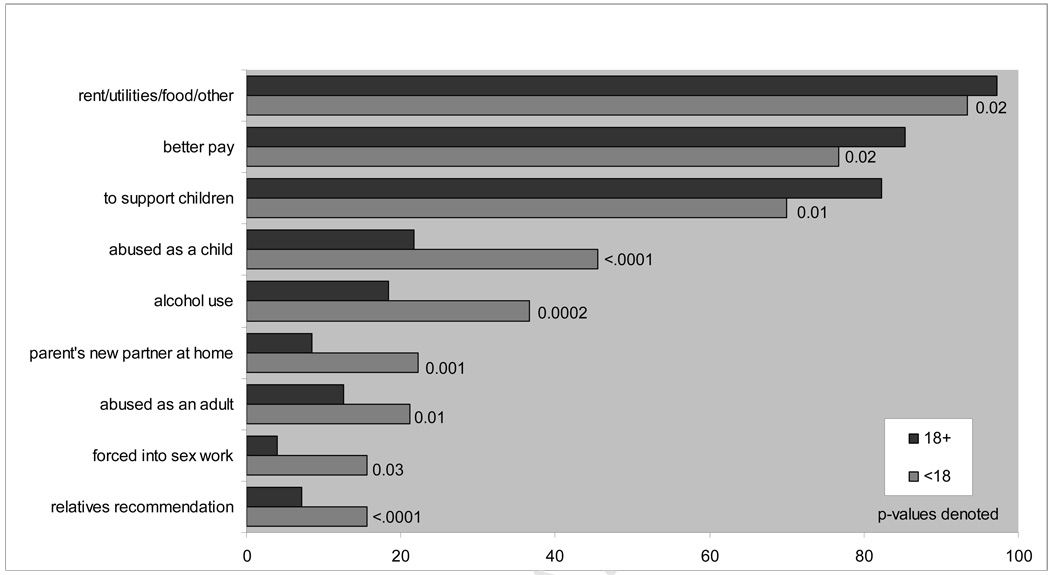

Participants were presented with a list of 23 factors that might have influenced their initiation into sex work. Items were derived from the literature and a prior qualitative study conducted among FSWs in Tijuana [26]. Concerning the list, participants were asked, “Did any of the following influence you to be a sex worker?” Possible responses are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Factors Influencing Initiation into Sex Work among Women in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, by Age Group of Initiation, % (N=924)

Drug Use before Initiating Sex Work

Frequency and modes of use for marijuana, ecstasy, inhalants, cocaine, tranquilizers, methamphetamine, heroin, and combinations were assessed with the following questions: “Have you ever used [drug type] (yes, no)?”; “How old were you when you first used [drug type]?”; “What ways did you use this drug (ingested, injected, smoked/sniffed, other)?”

Emotional, Physical, and Sexual Abuse

Participants were asked if they had ever been abused emotionally (through harsh words, humiliation, manipulation), physically (experienced actual or threatened physical harm), or sexually (through unwanted sexual advances or non-consensual sexual acts), and the age at which any of these first occurred. Victimization and trauma were measured using items from the family and social relationships section of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI-F) [27].

Statistical Analysis

Age of initiation into sex work was defined as a binary variable: “early initiators” who had initiated sex work before the age of 18. Drug use before sex work (yes/no) was determined by comparing the age of first use for each drug and the age of initiation into sex work. “Any drug use” includes marijuana, inhalants, ecstasy, tranquilizers, barbiturates, heroin, methamphetamines, cocaine, crack, speedball (heroin and cocaine injected simultaneously), or methamphetamine and heroin. Physical, emotional, and sexual abuse before initiation into sex work were defined by a similar comparison of reported dates. Participants’ places of origin (birth states) within Mexico were classified according to a scheme that was used in previous analyses [21] and that consists of three regions: Northern (9 states), Central (15 states), and Southern (8 states).

Crude and age-adjusted bivariate associations were examined between age of initiation into sex work and each risk factor. Group means of continuous data were compared with two-sided t-tests. Frequencies of categorical data were compared with Pearson chi-square tests. Logistic regression models were conducted to examine correlates of early initiation into sex work. Correlations among independent variables were assessed with Spearman correlation coefficients; variables with r>0.5 were not included in the same model. Variables attaining p<0.10 in bivariate models were considered in stepwise logistic regression, and those with p<0.05 were retained. Tolerance tests on final models were performed to assess multicollinearity. No significant differences were observed between age of initiation into sex work and site (Tijuana vs. Ciudad Juarez); hence the data for both sites were pooled.

RESULTS

Of 924 FSWs interviewed, 920 reported their age initiation into sex work; of those, 90 (9.8%) had initiated sex work before the age of 18 and hence were considered early initiators. Median age of entry into sex work was 26 years (range: 6–58); for early initiators it was 16 (range: 6–17), and for later initiators it was 27 (range: 18–58). At baseline, almost all women currently had children, while approximately half were single. Over half of the women had used some drug prior to initiation into sex work. The following proportions of participants reported histories of the different categories of abuse prior to their initiations into sex work: emotional (13%), physical (11%), and sexual (7%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bivariate associations§ by age of initiation into sex work (<18 vs 18+) among Female Sex Workers in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico (N=920)

| Age at Initiation into Sex Work | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | <18 | 18+ | |||||

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | N | % | N | % | N | % | p-value |

| Age at initiation into sex work | 90 | 9.8 | 830 | 90.2 | -- | ||

| Median age at initiation into sex work (IQR) | 26 | (21, 32) | -- | ||||

| Median age (IQR) | 32 | (26, 40) | 27 | (20, 34) | 33 | (27, 40) | <.0001 |

| Median highest year of school completed (IQR) | 6 | (4, 8) | 6 | (4, 8) | 6 | (4, 8.5) | 0.03 |

| Site | 0.10 | ||||||

| Tijuana | 481 | 51.7 | 41 | 45.6 | 433 | 52.2 | |

| Ciudad Juarez | 450 | 48.3 | 49 | 54.4 | 397 | 47.8 | |

| Marital Status | 0.04 | ||||||

| Married or Cohabiting | 222 | 24.0 | 31 | 34.4 | 191 | 23.1 | |

| Single | 460 | 49.7 | 44 | 48.9 | 411 | 49.6 | |

| Other | 243 | 26.3 | 15 | 16.7 | 226 | 27.3 | |

| Currently have children | 868 | 93.7 | 80 | 88.9 | 783 | 94.5 | 0.47 |

| Median number of Children (IQR) | 3 | (2,4) | 2 | (1,3) | 3 | (2,4) | 0.68 |

| Had a child before initiating sex work | 749 | 86.9 | 22 | 27.5 | 727 | 93.0 | <.0001 |

| Mexican Region of Birth | 0.15 | ||||||

| North | 664 | 72.4 | 73 | 81.1 | 586 | 71.5 | |

| Central | 199 | 21.7 | 14 | 15.6 | 83 | 22.4 | |

| South | 54 | 5.9 | 3 | 3.3 | 51 | 6.1 | |

| Migrated into this State | 557 | 60.7 | 43 | 47.8 | 511 | 62.3 | 0.02 |

| Drug Use Before Initiating Sex Work | |||||||

| Marijuana | 351 | 37.9 | 35 | 39.3 | 313 | 37.8 | 0.80 |

| Inhalants | 101 | 10.9 | 19 | 21.1 | 80 | 9.6 | 0.002 |

| Cocaine | 227 | 24.4 | 17 | 18.9 | 208 | 25.1 | 0.11 |

| Tranquilizers | 115 | 12.4 | 13 | 14.4 | 102 | 12.3 | 0.41 |

| Methamphetamine | 153 | 16.5 | 9 | 10.0 | 143 | 17.3 | 0.06 |

| Heroin | 110 | 11.8 | 7 | 7.9 | 102 | 12.3 | 0.21 |

| Any drug use* | 491 | 53.0 | 45 | 50.0 | 443 | 53.4 | 0.40 |

| Abuse Before Initiating Sex Work | |||||||

| Emotional abuse | 114 | 12.6 | 27 | 30.3 | 87 | 10.7 | <.0001 |

| Physical abuse | 100 | 11.0 | 26 | 28.9 | 74 | 9.1 | <.0001 |

| Sexual abuse | 63 | 6.9 | 18 | 20.0 | 45 | 5.5 | <.0001 |

Age-adjusted bivariate associations (p-values) between early versus later initiators into sex work with logistic regression

Median (IQR) reported for continuous variables

bold for p-values <0.10

Any drug use includes use of marijuana, inhalants, ecstasy, tranquilizers, barbiturates, heroin, methamphetamines, cocaine, crack, speedball (i.e. heroin+cocaine injected simultaneously), or methamphetamine+heroin.

Bivariate Associations

After adjusting for age, early initiators were significantly younger than older initiators at baseline (27 vs 33 years old), less likely to have had a child prior to initiating sex work (27.5% vs 93.0%), and less likely to have migrated into the state in which the interview was conducted (47.8% vs 62.3%; p<0.05). Median number of crude years of education was the same (6 years) for early versus older initiators, but it was significantly different after adjusting for age (p=0.03) (Table 1). Early initiators were significantly more likely to report inhalant use (21.1% vs 9.6%) and less likely to report methamphetamine use (10.0% vs 17.3%) prior to initiation into sex work compared to later initiators. After adjusting for age, early initiators reported significantly higher rates of experiencing emotional (30.3% vs 10.7%), physical (28.9% vs 9.1%), and sexual (20.0% vs 5.5%) abuse prior to initiating sex work (p<0.0001). Low to medium correlations between emotional, physical, and sexual abuse were indicated by Spearman correlation coefficients as follows: emotional vs. physical abuse: 0.57; physical vs. sexual abuse: 0.35; and sexual vs. emotional abuse: 0.37.

Factors Influencing Initiation into Sex Work

Regardless of age of initiation into sex work, over 90% of participants reported that needing money for rent, utilities, food, or other necessities was an important influence on their decision to begin sex work. This was followed in importance by a need for better pay, a need to support children, abuse experienced as a child or adult, and ongoing alcohol use. The frequency distribution of influencing factors differed significantly for younger vs older initiators into sex work; however, the order of importance was generally the same for both groups (Figure 1).

Age-Adjusted Comparisons

Factors associated with later initiation into sex work included being older (OR: 0.64 per 5-year increase), having more years of education (OR: 0.66 per 5-year increase), having migrated into the state in which the participant lived at the time of interview (OR: 0.58), and having a child prior to initiation into sex work (OR: 0.03). Participants who were single (OR: 0.59) or in non-marital relationships (OR: 0.46) were less likely to have initiated sex work early as compared to those who were married (Table 2).

Table 2.

Age-adjusted comparisons of factors by age of initiation§ into sex work in among Female Sex Workers in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico (N=920)

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic Characteristics | ||

| Age (per 5 year increase) | 0.64 | (0.55, 0.75) |

| Site (Ciudad Juarez vs Tijuana) | 1.45 | (0.93, 2.27) |

| Education (per 5 year increase) | 0.66 | (0.45, 0.96) |

| Currently have a spouse/steady partner | 1.30 | (0.82, 2.05) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single vs Married or Cohabiting | 0.59 | (0.36, 0.98) |

| Other vs Married or Cohabiting | 0.46 | (0.24, 0.90) |

| Currently have children | 0.76 | (0.36, 1.62) |

| Had a child before initiating sex work | 0.03 | (0.02, 0.05) |

| Mexican Region of Birth | ||

| Central vs North | 0.64 | (0.35, 1.17) |

| South vs North | 0.44 | (0.13, 1.46) |

| Migrated into this State | 0.58 | (0.37, 0.91) |

| Drug Use Before Initiating Sex Work | ||

| Marijuana | 1.06 | (0.67, 1.68) |

| Inhalants | 2.47 | (1.39, 4.40) |

| Cocaine | 0.63 | (0.36, 1.11) |

| Tranquilizers | 1.30 | (0.69, 2.45) |

| Methamphetamine | 0.49 | (0.24, 1.01) |

| Heroin | 0.59 | (0.26, 1.33) |

| Any drug use* | 0.82 | (0.53, 1.28) |

| Abuse Before Initiating Sex Work | ||

| Emotional abuse | 4.06 | (2.39, 6.90) |

| Physical abuse | 4.84 | (2.80, 8.36) |

| Sexual abuse | 5.89 | (3.09, 11.20) |

| Influences for Entering Sex Work | ||

| Better pay | 0.52 | (0.30, 0.89) |

| To pay for alcohol use | 2.43 | (1.51, 3.91) |

| To support children | 0.53 | (0.32, 0.88) |

| Needed money for rent, utilities, food, or other | 0.32 | (0.12, 0.86) |

| Abused as an adult | 2.02 | (1.15, 3.54) |

| Abused as a child | 2.92 | (1.85, 4.61) |

| Forced into sex work against will | 4.15 | (2.07, 8.33) |

| Parent brought new partner into the home | 2.58 | (1.45, 4.57) |

| Relatives’ recommendation | 2.08 | (1.09, 3.98) |

Note: measure of association (OR and 95% CI) for age is not age-adjusted

initiated sex work before 18 years versus 18+ years

Any drug use includes use of marijuana, inhalants, ecstasy, tranquilizers, barbiturates, heroin, methamphetamines, cocaine, crack, speedball (i.e. heroin+cocaine injected simultaneously), or methamphetamine+heroin.

Reference category is <18 and ‘No’.

Participants who used inhalants before initiating sex work were twice as likely to be early initiators. A history of emotional (OR: 4.06), physical (OR: 4.84), or sexual (OR: 5.89) abuse prior to initiation into sex work was associated with initiating sex work at an earlier age. Better pay, needing to support children, and needing money for rent, utilities, food, or other commodities were influences for entering sex work at older ages. Factors associated with at least a two-fold greater odds of early initiation into sex work included needing to pay for alcohol, having been abused as an adult or child, having been forced into sex work, having a parent bring a new partner into the home, and having a relative recommend sex work as a profession (Table 2).

Factors Independently Associated with Initiation into Sex Work

After adjusting for age, factors independently associated with early initiation into sex work included prior emotional abuse (adjOR: 3.73), prior inhalant use (adjOR: 2.86), and history of childhood abuse (adjOR: 3.89). Later initiation into sex work was independently associated with less education (adjOR: 0.43 per 5-year increase), migrating to the state in which one now lives (adjOR: 0.47), initiating sex work for better pay (adjOR: 0.44), and initiating sex work to support one’s child (adjOR: 0.03) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors independently associated with early§ versus older initiation into sex work (N=833)

| Characteristic | Beta | SE | Wald Chi-Square | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 5 year increase) | −0.09 | 0.02 | 19.6 | <.0001 | 0.64 (0.52, 0.79) |

| Education (per 5 year increase) | −0.17 | 0.06 | 8.8 | 0.00 | 0.43 (0.25, 0.75) |

| Migrated into this State | −0.75 | 0.32 | 5.3 | 0.02 | 0.47 (0.25, 0.89) |

| Emotional abuse before initiating sex work | 1.29 | 0.38 | 11.4 | 0.001 | 3.73 (1.76, 7.89) |

| Inhalant use before initiating sex work | 1.07 | 0.40 | 7.3 | 0.01 | 2.86 (1.32, 6.21) |

| Better pay influenced sex work initiation | −1.47 | 0.72 | 4.2 | 0.04 | 0.44 (0.2, 0.96) |

| Abused as a child | 1.29 | 0.33 | 14.8 | 0.0001 | 3.89 (2.01, 7.54) |

| Had a child before initiating sex work | −3.48 | 0.34 | 103.6 | <.0001 | 0.03 (0.02, 0.06) |

initiated sex work at <18 years

SE: Standard Error

DISCUSSION

This study’s findings suggest different pathways for entering sex work between younger versus older women living in two Mexico–U.S. border cities. We found differences in sociodemographic characteristics, history of drug use, history of abuse, and influences for entering sex work between the women who initiated sex work before the age of 18 versus those who initiated sex work later in their lives. Early initiation into sex work was independently associated with history of emotional abuse, inhalant use, and child abuse, whereas lower education, migration, and initiating sex work for better pay and to support one’s children were independently associated with initiating sex work at older ages. These findings may have important implications with respect to delaying or preventing entry into sex work for women living in border communities.

After adjusting for age, we found that early initiation into sex work was independently associated with a history of emotional abuse and being abused as a child. In other countries, a relationship has been established between history of various forms of abuse and engaging in sex work [11, 28]. Childhood abuse has been linked with entry into the juvenile criminal system, suicide attempts, diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder, alcohol abuse, and decreased quality of interpersonal relations, such as frequent divorce and partner separation, which may reflect an inability to cope with severe childhood trauma [28, 29]. Programs aimed at preventing young girls from entering sex work must consider that those most at risk are those who have experienced parental substance abuse, absence of parental supervision, early sexual debut, or sexual or physical abuse [6, 7, 11, 12, 28].

A unique finding from our study was that early inhalant use was independently associated with early initiation into sex work. In Mexico, the most commonly abused inhalants are easily accessible solvents such as paint thinner, glues, and sprays [30, 31]. Inhalants are often used by children working or living on the streets, by delinquent minors, school drop-outs, and those with no family ties [31]. Among Mexican juvenile offenders (N=626), inhalant users were at increased odds of having been abused by their parents [32]. Hence, inhalant use might serve as a coping mechanism for girls who have run away from home to avoid abuse. A national school survey conducted in 1998 in Mexico City found that among female adolescents between 12 and 17 years old, inhalants were the most common drug used after marijuana [30]. During the same year and in the same city, a national household survey of residents aged 12–65 indicated that among those who had initiated drug use between 12–17 years old, inhalants were the drug most commonly used; 65.2% of inhalant users began using these substances at between 12 and 17 years old [30, 31]. Beyond the association with early initiation into prostitution, inhalant users are also at increased risk of initiating injection drug use, acquiring HIV, and developing psychiatric disorders [33]. Hence, intervening on inhalant use among high-risk children and adolescents living in Mexico and providing age-appropriate mental health care may aid them in addressing the histories of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse that may predispose them to prostitution.

Our study found that less education, dependent children, and other economic needs were associated with older initiation into sex work, which is consistent with the literature. Other studies have shown that women who had pregnancies at an early age [34] or who had dependent children were likelier to enter sex work at a later age [35]. In Australia, where sex work can be practiced legally, most FSWs indicate that their primary motivation for entering (76%) or staying in (61%) the sex trade is financial, yet 55% said they wanted to leave the industry [36]. These findings indicate a strong need for alternative sources of income for women with children and other dependents.

Sex work in the border region has been shaped by numerous policy decisions and historical events. Prohibition in the U.S. in the 1920s and 1930s, the development of U.S. military bases along the border, and demand for Mexican labor stimulated the growth of border cities such as Tijuana. These cities, in turn, offered social opportunities to U.S. residents that were not as readily available in the U.S., such as drinking, gambling, and prostitution [37]. Since the 1960s, employment in maquiladoras (foreign- owned manufacturing plants) has also stimulated migration Mexico’s interior to its northern border [37]. However, there is some evidence that women have trouble supporting themselves and their families on the maquiladoras’ low wages, whereas prostitution may offer a more viable income to some [38]. We found that migration was independently associated with initiating sex work at older ages independent of other social factors, a finding that merits further exploration to determine whether familial or environmental vulnerabilities are influencing older women’s trajectories into sex work. These results suggest a need for supportive social services for female migrants, whether newly arrived or of longer standing.

Female migrants to the border region may be at risk for sexual harassment, violence, and exploitation from employers [15]. It is plausible that some young FSWs living in the border region are victims of human trafficking (forced migration) or sex trafficking (forced sex work). However, such activities are extremely challenging to assess, since victims are difficult to identify and reach [2, 39]. Further, the human-subjects requirements governing our research forced us to exclude FSWs who were under 18 at the baseline interview, which may limit the generalizability of our findings and our assessment of the avenues into sex work for young women. Nevertheless, this remains an important area of investigation; we expect that young FSWs are likely to experience a unique set of vulnerabilities that may influence their health behaviors and health status.

Our interpretation of the results has several limitations. While we could infer temporality based on the age at which participants reported engaging in sex work relative to other exposures, the cross-sectional nature of the data precludes definitive causal inferences. Another important limitation is the small proportion of women who reported initiating sex work before the age of 18 (9.8%), which affected the power to detect significant associations. It is possible that some FSWs who initiated sex work prior to the legal age were reluctant to report doing so, which would tend to underestimate the odds ratios we observed. Recall bias may have influenced the results given that the participants were asked to recall information about drug use and other life events that occurred years prior.

Despite these limitations, our study suggests different pathways for entry into sex work for younger versus older Mexican girls and women. These findings highlight the need for interventions among younger girls, particularly those living on the street, to prevent inhalant use and provide coping skills for abuse. Interventions for inhalant use should consider that adolescents perceive inhalant use as low-risk and that the use of inhalants is associated with problems in social or family networks [40]. Identification of adolescents who were victims of childhood and emotional abuse is necessary to provide healthy coping strategies, which may help to deter or delay initiation of sex work, drug use, and other high-risk behaviors. For older initiators into sex work, alternative income-generating strategies (e.g., microfinancing), childcare, and migrant-oriented services (e.g., housing, employment) may help to delay or prevent entry into sex work.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible with support from NIH Grants R01 MH065849 (T.L. Patterson, P.I.), R01 DA023477 (S.A. Strathdee, P.I.), and Diversity Supplements R01 DA019829-02S1 and DA019829-02S2 (S.A. Strathdee, P.I.). The authors gratefully acknowledge the cooperation of the staff and participants of Proyecto Mujer Segura (NIH R01 MH065849) and of the following organizations: the Municipal and State Health Departments of Tijuana, Baja California and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua; Salud y Desarollo Comunitario de Ciudad Juárez A.C. (SADEC), Patronato Pro-COMUSIDA and Federación Mexicana de Asociaciones Privadas (FEMAP); the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (UABC); and the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez (UACJ). O. Loza also gratefully acknowledges her dissertation committee: S. A. Strathdee, T. L. Patterson, and V.D. Ojeda from the University of California at San Diego and S. Lindsay and M. Ji from San Diego State University.

Human Participant Protection

The protocol for the research study on which this article is based was reviewed and approved by UCSD’s Human Research Protection Program (HRPP). The HRPP is a federally accredited Institutional Review Board (IRB) whose Federal-wide Assurance Number is FWA00004495.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Fraga M, Bucardo J, de la Torre A, Salazar J, et al. Comparison of sexual and drug use behaviors between female sex workers in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(10–12):1535–1549. doi: 10.1080/10826080600847852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller E, Decker MR, Silverman JG, Raj A. Migration, sexual exploitation, and women's health: a case report from a community health center. Violence Against Women. 2007 May;13(5):486–497. doi: 10.1177/1077801207301614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau C. Child prostitution in Thailand. J Child Health Care. 2008 Jun;12(2):144–155. doi: 10.1177/1367493508090172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Willis BM, Raj A. HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women. JAMA. 2007 Aug 1;298(5):536–542. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weatherby NL, McCoy HV, Metsch LR, Bletzer KV, McCoy CB, de la Rosa MR. Crack cocaine use in rural migrant populations: living arrangements and social support. Subst Use Misuse. 1999 Mar-Apr;34(4–5):685–706. doi: 10.3109/10826089909037238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishoy T, Ishoy PL, Olsen LR. Street prostitution and drug addiction. Ugeskr Laeger. 2005 Sep 26;167(39):3692–3696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene JM, Ennett ST, Ringwalt CL. Prevalence and correlates of survival sex among runaway and homeless youth. Am J Public Health. 1999 Sep;89(9):1406–1409. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brouwer KC, Case P, Ramos R, Magis-Rodriguez C, Bucardo J, Patterson TL, et al. Trends in production, trafficking, and consumption of methamphetamine and cocaine in Mexico. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(5):707–727. doi: 10.1080/10826080500411478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strathdee SA, Philbin MM, Semple SJ, Pu M, Orozovich P, Martinez G, et al. Correlates of injection drug use among female sex workers in two Mexico-U.Sborder cities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008 Jan 1;92(1–3):132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valdez A, Cepeda A, Kaplan C, Codina E. Office for Drug and Social Policy Research, Graduate School of Social Work. Houston, TX: University of Houston; 2002. Sex work, high-risk sexual behavior and injecting drug use on the U.S.-Mexico border: Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simons RL, Whitebeck LB. Sexual Abuse as a Precursor to Prostitution and Victimization Among Adolescent and Adult Homeless Women. Journal of Family Issues. 1991;12:361. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Widom CS, Kuhns JB. Childhood victimization and subsequent risk for promiscuity, prostitution, and teenage pregnancy: a prospective study. Am J Public Health. 1996 Nov;86(11):1607–1612. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh G. Paradoxical payoffs: migrant women, informal sector work, and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. New Solut. 2007;17(1–2):71–82. doi: 10.2190/7166-6QV1-1503-9464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang X, Xia G. Gender, migration, risky sex, and HIV infection in China. Stud Fam Plann. 2006 Dec;37(4):241–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2006.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carballo M, Grocutt M, Hadzihasanovic A. Women and migration: a public health issue. World Health Stat Q. 1996;49(2):158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt CW. Migrant labor and sexually transmitted disease: AIDS in Africa. J Health Soc Behav. 1989 Dec;30(4):353–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strathdee SA, Magis-Rodriguez C. Mexico's evolving HIV epidemic. JAMA. 2008 Aug 6;300(5):571–573. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orrenius PM, Zavodny M, Lukens L. Why Stop There? Mexican Migration to the U.S. Border Region. [Accessed January 13, 2009];Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas RD. ed. 2008 Dallas: http://www.dallasfed.org/research/papers/2008/wp0803.pdf.

- 19.De la OME. Trayectorias laborales en obreros de la industria maquiladora en la frontera norte de Mexico: un recuento para los anos noventa [Job Trajectories of Workers in the Maquiladora Industry on Mexico's Northern Border: A Review for the 1990s] Revista Mexicana de Sociología. 2001;63(2):27–62. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Instituto Nacional de Estadistica Geografia e Informatica (INEGI) [Accessed Mar 3, 2009];Resultados Definitivos Del II Conteo De Población y Vivienda 2005 para el Estado de Baja California y Chihuahua [Definitive Results of 2005 Census for State of Baja California and Chihuahua] http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/espanol/sistemas/conteo2005/Default.asp.

- 21.Ojeda VD, Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Rusch ML, Fraga M, Orozovich P, et al. Associations between migrant status and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Tijuana, Mexico. Sex Transm Infect. 2009 Feb 10; doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.032979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keefer SL, Johnson DV. USAWC Strategy Research Project. Carlisle, PA: 2006. Human Trafficking and the Impact on National Security for the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Human Smuggling and Trafficking Center (HSTC) [Accessed May 14, 2009];FACT SHEET: Distinctions Between Human Smuggling and Human Trafficking. 2005 January; http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/crim/smuggling_trafficking_facts.pdf.

- 24.U.S. Department of State. [Accessed May 14, 2009];Trafficking in Persons Report. 2005 http://www.state.gov/g/tip/rls/tiprpt/2005/46606.htm.

- 25.Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Fraga M, Bucardo J, Davila-Fraga W, Strathdee SA. An HIV prevention intervention for sex workers in Tijuana, Mexico: A pilot study. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2005;27:82–100. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucardo J, Semple SJ, Fraga-Vallejo M, Davila W, Patterson TL. A qualitative exploration of female sex work in Tijuana, Mexico. Arch Sex Behav. 2004 Aug;33(4):343–351. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000028887.96873.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Brunschot EG, Brannigan A. Childhood maltreatment and subsequent conduct disorders. The case of female street prostitution. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2002 May-Jun;25(3):219–234. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(02)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Widom CS. Childhood victimization: Early adversity, later psychopathology. Institute of Juvenile Justice Journal. 2000 January;:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medina-Mora ME, Cravioto P, Villatoro J, Fleiz C, Galvan-Castillo F, Tapia-Conyer R. Drugs use among adolescents: results from the National Survey on Addictions, 1998. Salud Publica Mex. 2003;45 Suppl 1:S16–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medina-Mora ME, Berenzon S. Epidemiology of inhalant abuse in Mexico. NIDA Res Monogr. 1995;148:136–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tapia-Conyer R, Cravioto P, De La Rosa B, Velez C. Risk factors for inhalant abuse in juvenile offenders: the case of Mexico. Addiction. 1995 Jan;90(1):43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medina-Mora ME, Real T. Epidemiology of inhalant use. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008 May;21(3):247–251. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282fc9875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez Figueroa J, Irizarry Castro A, Alegria M, Vera M, Perez Perdomo R. Sociodemographic profile of a group of sex workers in Puerto Rico. P R Health Sci J. 1999 Mar;18(1):53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cwikel J, Chudakov B, Paikin M, Agmon K, Belmaker RH. Trafficked female sex workers awaiting deportation: comparison with brothel workers. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004 Oct;7(4):243–249. doi: 10.1007/s00737-004-0062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groves J, Newton DC, Chen MY, Hocking J, Bradshaw CS, Fairley CK. Sex workers working within a legalised industry: their side of the story. Sex Transm Infect. 2008 Oct;84(5):393–394. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.030668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson T. Economic and Social Impacts of Tourism in Mexico. Latin American Perspectives. 2008;35:37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curtis J, Arreola D. Zonas de Tolerancia on the Northern Mexico Border. Geographical Review. 1991;81(3):333–346. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saunders P. Traffic violations: determining the meaning of violence in sexual trafficking versus sex work. J Interpers Violence. 2005 Mar;20(3):343–360. doi: 10.1177/0886260504272509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perron BE, Howard MO. Perceived risk of harm and intentions of future inhalant use among adolescent inhalant users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008 Sep 1;97(1–2):185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]