Abstract

The objective of this study is to examine the clinical features and outcomes of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) whose disease began in adolescence [juvenile-onset SLE (jSLE)] compared with adult-onset patients [adult-onset SLE (aSLE)] from a large multiethnic cohort. Systemic lupus erythematosus patients of African-American, Caucasian, or Hispanic ethnicity and ≥1 year follow-up were studied in two groups: jSLE (diagnosed at ≤18 years); aSLE (diagnosed at 19–50 years; matched for gender and disease duration at enrolment). Sociodemographic data, SLE manifestations, disease activity, damage accrual, SLE-related hospitalizations or emergency room visits, drug utilization, mortality and psychosocial characteristics and quality of life were compared. Data were analysed by univariable and multivariable analyses. Seventy-nine patients were studied (31 jSLE, 48 aSLE); 90% were women. Mean (SD) total disease duration was 6.8 (2.7) years in jSLE and 5.6 (3.3) years in aSLE (p = 0.077). Mean age at cohort entry was 18.4 (1.8) and 33.9 (9.2) years in jSLE and aSLE respectively. By univariable analysis, jSLE patients were more commonly of African-American descent, were more likely to have renal and neurological involvements, and to accrue renal damage; jSLE patients had lower levels of helplessness and scored higher in the physical component measure of the SF-36 than aSLE patients. Renal involvement [OR = 1.549, 95% CI (1.397–15.856)] and neurological involvement [OR = 1.642, 95% CI (1.689–15.786)] were independently associated with jSLE by multivariable analysis. There was a larger proportion of African-Americans within the jSLE group. After adjusting for ethnicity and follow-up time, jSLE patients experienced more renal and neurological manifestations, with more renal damage. There was a two-fold higher mortality rate in the jSLE group.

Keywords: juvenile-onset SLE, outcome

Introduction

Approximately 15% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have disease which begins in childhood.1 The short-term outcomes (5-year follow-up) of patients with SLE whose disease begins in childhood have been reported in a number of paediatric case series from paediatric rheumatology centers, documenting not only improved survival over the past 15 years, but also more severe disease onset, and a high degree of morbidity compared with adult SLE populations.2–5

It is extremely difficult to study long-term outcome of juvenile-onset SLE, and there is very little data reporting outcome in adulthood. The majority of the literature concerning outcomes of juvenile-onset SLE (jSLE) comes from groups of patients diagnosed and followed in paediatric rheumatology clinics, mainly focusing on clinical characterization of SLE course. One of the barriers to studying the long-term outcomes of juvenile-onset SLE is that the patients leave paediatric rheumatology clinics, moving to adult rheumatology care around age 18 years, thus making continuing follow-up challenging. Some children or adolescents may not be cared for by paediatric rheumatologists; they may be seen by nephrologists or adult rheumatologists. There is only one report of long-term outcomes in adulthood for jSLE patients, from a cohort of patients who had been followed at a single paediatric rheumatology center with a mean follow-up of 13.6 years (mean age at follow-up of 25.5 years).6 The study distinctively provides information about the adulthood socioeconomic outcome of patients with juvenile-onset SLE, showing a low rate of high school and university/college completion, with half of patients working and 11% receiving disability benefits.6

In this study, we are studying a unique data source, a well-established multiethnic cohort of adults with SLE, in order to try to answer questions about the outcomes of patients with juvenile-onset SLE. We hypothesized that these patients in this cohort with juvenile-onset disease, compared with those with disease onset in adulthood, would have a higher frequency of serious organ-system SLE manifestations and more active disease, resulting in more damage and a negative outcome. We also hypothesized that socioeconomic outcomes would be less favourable in patients with juvenile-onset disease. Using a nested case–control methodology, we examined the clinical and socioeconomic differences between patients in the LUMTNA (LUpus in MInorities: NAture versus nurture) study, whose disease began in childhood and adolescence, compared with those whose disease began in adulthood.

Patients and methods

Patients

The constitution of the LUMINA cohort has been previously reported.7 LUMINA is a multicentre, multiethnic longitudinal study of SLE outcome with current follow-up data of over 10 years for those who initially enrolled in the cohort.7,8 Eligible patients are ≥16 years of age, fulfil four or more of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) SLE classification criteria,9 have ≤5 years of disease duration at study entry and are of defined ethnicity [African-American, Caucasian, Hispanic (from Texas or Puerto Rico)]. LUMINA patients reside within the catchment area of participating institutions (the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus). The Institutional Review Board of each center has approved the study and written informed consent was obtained in all participating patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. At the time these analyses were made, the LUMINA cohort consisted of 617 patients.

Prior to entry into the LUMINA cohort, patient eligibility was confirmed through review of available medical records. At enrolment and each subsequent visit, a study physician interviewed each patient, and a physical examination and laboratory tests were performed. A complementary chart review was also performed to document clinical information for the interval preceding the study visit. Clinical characterization of the disease at diagnosis (TD) was obtained from review of medical records at the recruitment visit (T0). For patients with adolescent-onset disease, there were no paediatric rheumatology records as these patients were not followed in paediatric clinics. Follow-up visits were held every 6 months during the first year (T0.5 and T1), and yearly thereafter (T2, T3, etc.) until the last available visit (TL). Clinical information of missed study visits was completed through review of medical records.

There were two patient groups of interest for these analyses: the jSLE group defined as being <18 years of age at TD, whereas the adult-onset SLE (aSLE) group defined as being 19–49 years of age at TD. All juvenile-onset patients were randomly matched for gender and disease duration (±6 months) in a 1:2 ratio with the adult-onset patient group. Patients with late-onset disease (diagnosis at ≥50 years) were not included in the pool of patients, from which the control patients were drawn, due to previous data which has shown that older lupus patients have increased disease damage and mortality than younger onset patients.10 All patients were cared for by adult rheumatologists at the time of enrolment into the LUMINA cohort.

Variables

As previously described,7,11 the LUMINA database comprises variables from the following domains: socioeconomic–demographic, clinical, immunological, genetic, behavioural and psychological. Only variables included in these analyses will be described.

Sociodemographic variables included were: age at T0 and at disease onset, gender, ethnicity, years of education, marital status, health insurance, receiving disability benefits, current occupation and poverty (as per the US Federal Government definition, adjusted for the number of household members).12 Education, marital status, insurance and disability status, occupation and poverty level were measured at last study follow-up (TL).

Behavioural and psychosocial variables included in this study (TL) were unhealthy behaviours (smoking, alcohol consumption, not exercising), helplessness as per the Rheumatology Attitudes Index,13 social support as per the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL)14 and coping skills as per the Illness Behaviour Questionnaire (IBQ).15 Health-related quality of life was assessed with the physical and mental component summary measures (PCS and MCS respectively) of the SF-36.16

Selected clinical features included disease duration, defined as the time elapsed between TD (time when the ACR criteria were fulfilled) and T0; follow-up time, defined as the interval between T0 and TL; disease onset, considered acute if criteria accrual occurred within 4 weeks or less and insidious, if otherwise; disease activity ascertained at TD, T0, TL and on average with the Systemic Lupus Activity Measure-Revised (SLAM-R)17 and through physician and patient global estimation of lupus activity by using 10-cm visual analogue scales; damage accrual, ascertained with the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology (SLICC/ACR) Damage Index (SDI)18 at T0 and TL; number of ACR criteria accrued at TL and ACR criteria manifestations at T0. Renal involvement was defined as lupus nephritis, WHO Class II-V and/or proteinuria (>0.5 g/24 h or 3+) attributable to SLE and/or abnormal urinary sediment, proteinuria 2+, elevated serum creatinine/decreased creatinine clearance twice, 6 months apart. Total number of SLE-related hospitalizations or emergency room (ER) visits during the follow-up interval were also recorded. Coexistent cardiovascular comorbidities (i.e. ischaemic heart disease, stroke, thrombosis), antiphospholipid antibodies positivity (a lupus anticoagulant or antiphospholipid antibody positive test ever) and drug utilization (use and average dose of corticosteroids, use of hydroxychloroquine, cyclophosphamide or other immunosuppressive drugs) were noted as well. Deaths were recorded.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). To better account for long-term disease effects between patients with adolescent-onset SLE and aSLE, only patients with more than 1 year follow-up were included in the analyses. Patients with <1 year follow-up would not provide adequate data for analysis. Differences between the two groups were examined initially using Student’s t-test for continuous variables, and Chi-square (or Fisher’s exact test, when appropriate) for categorical variables. Logistic and linear regression analyses were performed subsequently to adjust for differences in ethnic distribution and the effect of follow-up time; p-values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Multivariable analyses were performed to determine the association of adolescent-onset SLE with variables that were significant in the univariable analyses, and with those felt to be clinically important. A binary logistic regression using a backward selection method was employed, with adolescent-onset SLE as the dependent variable.

Results

One-hundred and twelve patients were identified (40 with jSLE and 72 with aSLE). Of these, 79 (31 with juvenile-onset and 48 with adult-onset disease) had follow-up >1 year and thus were included in these analyses. For 14 juvenile-onset patients, there was only one appropriate match. The vast majority of patients were women (90%). Thirty-seven per cent of patients were African-Americans, 23% were Caucasians, 24% were Hispanics from Texas and 16% were Hispanics from Puerto Rico. Disease duration at enrolment was 1.6 (1.4) years [mean (standard deviation)], and total follow-up time was 4.4 (2.9) years. Among the juvenile-onset group, in this study, the age at diagnosis of SLE ranged from 13.2 to 18 years (mean 16.7, SD 1.7); therefore, this group is more accurately referred to as ‘adolescent-onset’ SLE.

Univariable analyses

Demographic and socioeconomic features

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics are shown in Table 1. There was a higher proportion of patients of African-American descent in the adolescent-onset group than the adult-onset group (p = 0.031); the converse was true for Caucasians and Hispanics from Puerto Rico. As expected, years of education at T0 were higher in the adult-onset group than patients with adolescent-onset disease; however, this difference disappeared when compared at last follow-up. Patients with disease onset in adulthood were more likely to be married at last available visit, probably due to the age difference between the groups. No significant difference was observed in the percentage of patients working or receiving disability benefits at TL between the two groups. Likewise, a similar proportion of patients in the two groups had health insurance. Interestingly, poverty was more common among patients with adolescent-onset lupus (48.3%) when compared with adult-onset disease (28.3%), although the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.082).

Table 1.

Baseline socioeconomic, demographic and behavioural features as a function of age at last available visit*

| Feature | Adult SLE (n = 48) | Adolescent SLE (n = 31) | p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | |||

| At diagnosis | 32.3 (9.2) | 16.7 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Range | 19.0–49.8 | 13.2–18.9 | |

| Baseline | 33.9 (9.2) | 18.4 (1.8) | <0,001 |

| Range | 19.7–51,9 | 14,0–22.5 | |

| Women, n (%) | 43 (89,6) | 28 (90,3) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| African-American | 13 (27.1) | 16 (51.6) | 0.031 |

| Caucasian | 14 (29.2) | 4 (12.9) | |

| Hispanic-Texan | 10 (20.8) | 9 (29.0) | |

| Hispanic-Puerto Rican | 11 (21.2) | 2 (6.5) | |

| Education, years, mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 13.4 (3.1) | 11.1 (2.1) | 0.001 |

| At last available visit | 13.5 (2.9) | 13.3 (2.6) | |

| Married/living together, n (%) | 19 (39.6) | 1 (3.2) | 0.006 |

| Working, n (%) | 16 (33.3) | 10 (32.3) | |

| On disability, n (%) | 16 (33.3) | 6 (22.6) | |

| Health insurance, n (%) | 37 (77.1) | 23 (74.2) | |

| Poverty, below line n (%) | 13 (28.3) | 14 (48.3) | |

| Sedentary lifestyle, n (%) | 21 (47.7) | 11 (37.9) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | 5 (11.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | 8 (18.2) | 2 (7.1) | |

| ISEL score, mean (SD) | 7.6 (1.7) | 8.3 (1.6) | |

| Helplessness, mean (SD) | 40.8 (6,1) | 37.7 (6.2) | 0.037 |

| IBQ, mean (SD) | 18.1 (6.9) | 19,8 (7.7) | |

| SF-36, MCS, mean (SD) | 41.5 (10.0) | 42.7 (11.7) | |

| SF-36, PCS, mean (SD) | 35.8 (9.6) | 40.0 (10.1) | 0.006 |

Abbreviations: ISEL: Interpersonal Support Evaluation List; IBQ: Illness Behaviours Questionnaire; MCS: mental component summary; PCS: physical component summary.

Unless otherwise specified.

Only p-values <0.05 are shown.

Psychosocial profile and health-related quality of life

There was a tendency towards better social support as determined by higher ISEL scores [8.3 (1.6) vs. 7.6 (1.7), p = 0.087] among patients with adolescent-onset SLE when compared with patients with adult-onset disease; they also experienced significantly lower levels of helplessness than the adult-onset group [37.7 (6.2) vs. 40.8 (6.1), p = 0.037]. Ability to cope with illness as determined by IBQ scores was comparable in both patient groups, These data are shown in Table 1.

A significantly higher SF-36 PCS was observed among patients with adolescent-onset disease when compared with their adult-onset counterparts; however, MCS was comparable between the groups.

Clinical features

Disease duration at study entry in the adolescent-onset patients vs. adult-onset patients was 1.7 (1.5) and 1.6 (1.4) years respectively (Table 2). Total follow-up time was somewhat longer in the adolescent group than in the adult-onset group [5.1 (3.0) vs. 4.0 (2.8) years], but this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.089).

Table 2.

Baseline clinical features as a function of age at diagnosis*

| Adolescent | ||

|---|---|---|

| Adult SLE | SLE | |

| Feature | (n = 48) | (n = 31) |

| Disease duration at enrolment, years, mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.5) |

| Total follow-up time, years, mean (SD) | 4.0 (2.8) | 5.1 (3.0) |

| Acute disease onset† n (%) | 7 (14.6) | 8 (25.8) |

| Number of ACR criteria, mean (SD) | 5.4 (1.5) | 5.8 (1.3) |

| SLAM score, mean (SD) | ||

| Baseline | 9.1 (5.7) | 9.7 (4.7) |

| At diagnosis | 11.4 (6.0) | 12.7 (6.9) |

| At last available visit | 7.6 (4.7) | 8.3 (4.3) |

| Average | 8.9 (3.6) | 9.2 (2.9) |

| Patient global assessment of disease activity‡, mean (SD) | ||

| Baseline | 3.6 (2.6) | 3.0 (2.8) |

| At last available visit | 3.2 (2.8) | 2.4 (2.8) |

| Physician global assessment of disease activity‡ mean (SD) | ||

| Baseline | 2.0 (1.7) | 2.7 (2.0) |

| At last available visit | 1.7 (1.7) | 2.1 (1.7) |

| Physician-patient assessment of disease discrepancy, mean (SD) | ||

| Baseline | 1.6 (2.7) | 0.4 (2.8) |

| At last available visit | 1.5 (2.8) | 0.3 (2.9) |

| Vascular events, n (%) | ||

| Arterial | 2 (4.2) | 1 (3.2) |

| Venous | 5 (10.4) | 1 (3.2) |

Abbreviations: AC: American College of Rheumatology; SLAM: Systemic Lupus Activity Measure.

None of the comparisons are statistically significant.

Over <4 weeks.

On a 10-cm visual analogue scale.

Adolescent-onset SLE patients had more active disease at all time-points (TD, T0, TL and on average over the entire study period) when compared with adult-onset patients, as quantified by the SLAM-R scores and physician visual analogue Scale (VAS); however, these differences did not reach statistical significance. However, patients with adolescent-onset disease perceived their disease to be less active than the adult-onset patients both at TO and TL, although the difference was again not significant (Table 2). Interestingly, the discrepancy between patient and physician global assessment of disease activity at TO was 0.4 (2.8) for adolescent-onset patients, vs. 1.6 (2.7) for adult-onset patients (p = 0.172). This discrepancy between patient and physician disease activity rating persisted at last study follow-up: 0.3 (2.9) for adolescent-onset vs. 1.5 (2.8) (p= 0.070) for adult-onset patients.

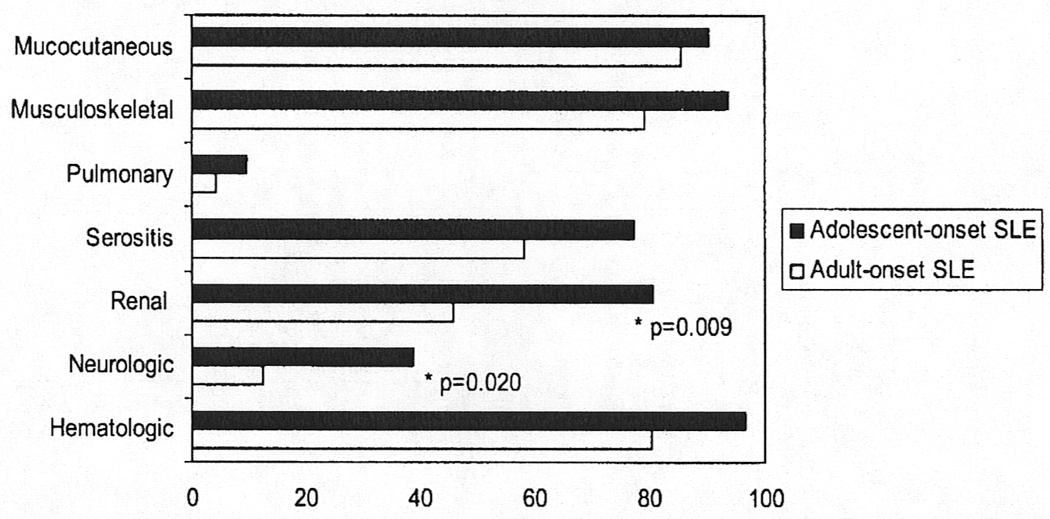

Systemic lupus erythematosus–related manifestations at study entry (T0) are shown in Figure 1. At T0, renal involvement was significantly more common in the adolescent-onset group compared with the adult-onset group (80.6% vs. 45.8%, p = 0.009). Likewise, neurological involvement at T0 as significantly more frequent in the adolescent group (38.7%) when compared with the adult group (12.5%),p = 0.020. Overall, patients with adolescent-onset lupus tended to have more SLE manifestations at T0 than those with adult-onset disease, such as haematological manifestations (96.8% vs. 80.4%, p = 0.066) and serositis (77.4% vs. 58.3%, p = 0.081).

Figure 1.

ACR criteria manifestations at baseline in 31 adolescent-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and 48 adult-onset SLE patients matched for gender and disease duration. Renal and neurological involvements are significantly increased in adolescent-onset patients. Renal involvement defined as WHO Class II-V and/or proteinuria (>0.5 g/24 h or 3+) attributable to SLE and/or abnormal urinary sediment, proteinuria 2+, elevated serum creatinine/decreased creatinine clearance twice, 6 months apart. Data are presented as percentage of patients.

The proportion of patients who had hospitalizations due to SLE-related causes was greater in the adolescent-onset patients than patients with adult-onset disease (67.7% vs. 37.5%); similarly, ER visits secondary to SLE-related causes were more likely to occur among adolescent lupus patients (54.8%) than those with adult disease (39.6%), although in both cases the observed differences were not statistically significant (data not shown). There were four strokes during the follow-up period; one in the adolescent and three in the adult-onset patient group. No ischaemic heart events occurred. Seven thromboses (two arterial, five venous) were observed in the adult-onset patients when compared with only two (one of each type) thrombotic events in the adolescent-onset group. Of interest, the proportion of patients with positive anti-phospholipid antibodies was similar between the adolescent-onset and adult-onset groups (35.5% vs. 31.1%, respectively, p = 0.858) (data not shown).

Damage accrual

Damage accrual in adolescent-onset and aSLE patients is shown in Table 3. SDI scores at T0 were not different between patients with adolescent-onset lupus [0.7 (1.1)] and those with adult-onset disease [0.5 (1.0)]. However, cumulative damage over the follow-up time was higher in the adolescent-onset group than the adult-onset group [2.3 (2.5) vs. 1.6 (2.0)], although not statistically significant, Renal damage was significantly more frequent in the adolescent-onset group (45.2%) than in the adult-onset group of patients (17.4%) (p = 0.023); end-stage renal disease (ESRD) occurred in one (2.1%) patient with adult-onset disease and in six (19.4%) patients in the adolescent-onset group (p=0.013).

Table 3.

Damage accrual at last available visit as a function of age at SLE diagnosis

| SLE diagnosis at <18 years | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No (n = 48) | Yes (n = 31) | p-value* |

| SL1CC/ACR Damage Index score, mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.7 (1.1) | |

| At last available visit | 1.6 (2.0) | 2.3 (2.5) | |

| Accrued any damage, n (%) | 32 (66.7) | 20 (64.5) | |

| SLICC/ACR Damage Index domain | |||

| Ocular, n (%) | 3 (4.3) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Neuropsychiatric, n (%) | 9 (19.6) | 9 (29.0) | |

| Renal, n (%) | 8 (17.4) | 14 (45.2) | 0.023 |

| Pulmonary, n (%) | 3 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Cardiovascular, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (6.5) | |

| Peripheral vascular, n (%) | 4 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Gastrointestinal, n (%) | 5 (10.9) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Musculoskeletal, n (%) | 7 (15.2) | 6 (19.4) | |

| Integument, n (%) | 7 (15.2) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Gonadal, n (%) | 5 (10.9) | 4 (12.9) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4 (8.7) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | |

Abbreviation: SLICC/ACR: Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology.

Only p-values <0.l0 are shown.

Similarly, neuropsychiatric damage was more common among adolescent-onset patients (29.0% vs. 19.6%), although the difference was not statistically significant. Gonadal failure occurred at a similar rate in both groups (12.9% in adolescent when compared with 10.9% in adult lupus onset). Likewise, avascular necrosis occurred at a similar rate in both groups (10.4% and 16.1% in aSLE vs. adolescent-onset SLE respectively). The rest of the damage index domains and items were comparable between the two groups.

Lupus treatment

The majority of patients in both groups received glucocorticoids as part of their management (96.8% and 85.4% in the adolescent and adult-onset patients); maximum and average doses were higher in the adolescent-onset group [49.1 (34.0) and 13.4 (8.0) mg/day] than in the adult-onset patients [34.9 (31.6) and 9.1 (9.3) mg/day)], although these differences did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.061 and p = 0.080 respectively). The proportion of patients who received intravenous cyclophosphamide during the course of their disease was four times higher in patients with adolescent-onset lupus than in patients with adult-onset disease (16.1% vs. 4.2%), however, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.088). Hydroxychloroquine and other immunosuppressive drugs were used at similar rates in the two groups (data not shown).

Mortality

Eleven deaths had occurred, six in the adolescent-onset and five in the adult-onset patients. Mortality was almost two-fold higher among adolescent-onset patients than among adult-onset patients (19.4% vs. 10.4%, p = 0.337). Causes of death included infectious (three patients with sepsis, one patient with pneumonia), pulmonary hypertension (one patient) and stroke (one patient) in the adolescent-onset patients, and stroke (three patients) and sepsis (one patient) in the adult-onset group. The cause of death could not be determined in one patient from the adult-onset group, although an intentional drug overdose was strongly suspected.

Multivariable analysis

A model was constructed to identify variables having an independent association with adolescent-onset SLE, as the dependent variable. Two clinical variables were significantly associated with adolescent-onset SLE; renal involvement (OR =1.642, 95% CI 1.689–15.786) and neurological involvement (OR = 1.549, 95% CI 1.397–15.856).

Discussion

The majority of studies reporting the long-term outcome of jSLE have examined data collected from patients attending paediatric rheumatology clinics, with no direct comparison with adult-onset patients. Although, some of these studies report 5- and 10-year outcomes at the time of last follow-up, most patients in these studies still remain in late adolescence at the time the data had been analysed. This study is a unique description of outcome of adolescents with SLE, who have been followed up in adulthood. Using a nested case-control study design, we examined a multiethnic longitudinal cohort of adult lupus patients and assessed whether there were differences in clinical course and outcomes when SLE begins in adolescence. These adult patients were not taken from paediatric rheumatology clinical programmes, but rather were followed by adult rheumatologists at the time of study entry and thus represent an exceptional study population. There were no patients in the childhood-onset group whose disease began prior to age 13 years. In the LUMINA study, patients have to be 16 years of age to enter the cohort, and cannot have more than 5 years of disease prior to entry; therefore, the earliest age at disease onset could have been 11 years. Patients with a younger onset of SLE would likely have been referred to paediatric programmes and are, therefore, not represented in this study.

In this study, we found that patients with adolescent-onset SLE had more active disease during the entire follow-up period as measured by the SLAM-R and physician rating of disease activity, although these differences were not statistically significant. Moreover, patients with adolescent-onset SLE were found to have significantly higher occurrence of renal and neurological involvements at time of diagnosis when compared with adult-onset lupus patients. These findings are consistent with other studies of paediatric SLE cohorts.19,20 Font, et al.19 described a higher proportion of patients with renal involvement at diagnosis in childhood-onset SLE patients as compared to patients with adult disease (20% vs. 9%); in contrast, they found neurological involvement to be more frequent among patients with adult-onset lupus. Increased SLE activity is likely to result in greater requirement of aggressive treatments to control disease, and in the longer term more disease damage. Our findings substantiate this with significantly higher rates of renal damage and ESRD amongst SLE patients with adolescent-onset disease. In our study, adolescent-onset lupus patients were almost two times more likely to be hospitalized due to SLE-associated causes and four times more likely to receive intravenous cyclophosphamide when compared with adult-onset patients; these findings demonstrate the significant persistent impact of SLE on the health of affected youth.

In our study, patients with adolescent-onset SLE accrued more damage with significantly more renal damage within the first years of their disease when compared with adult-onset disease. In a multicentre, multinational cross-sectional study from paediatric rheumatology centers in Europe, USA, Mexico and Japan where disease damage in 387 patients with SLE was examined, patients had a mean damage score of 1.1 after mean follow-up of 5.7 years.21 An extension of this multicentre study to include 1015 patients showed a mean damage score of 0.8 (mean follow-up 4.0 years), with a progressive increase in damage score over time with increasing disease duration.22 Three smaller single institution studies from paediatric rheumatology centers in Norway, USA and Canada showed similar results with mean damage scores of 1.3,23 1.84 and 2.13. Although, the mean damage scores of patient groups in these studies are similar to damage scores reported for aSLE patients, it is difficult to compare these results taken from very different cohorts. The comparison of adolescent-onset to adult-onset patients from the same cohort in this study showed a trend towards higher damage scores in the adolescent-onset SLE patients at last follow-up. Longer follow-up and larger patient numbers may help to further clarify this issue. Of interest, the mean damage index of our adolescent-onset patients in this study was 2.3, which is higher than that reported in all other paediatric rheumatology clinic population studies. This may be explained by factors, such as patient ethnicity, access to care, compliance, or socioeconomic factors which impact disease outcome in the LUMINA cohort, because the length of patient follow-up in our study is similar to the other paediatric studies.

In addition to clinical outcomes, SLE has broad impact on socioeconomic, educational and behavioural functioning of patients. Patients whose disease begins during childhood and adolescence are at risk of having interference with the normal developmental tasks of late adolescence and young adulthood, and this may result in problems in establishing healthy independent adult behaviour. 24 There have been very few long-term prospective studies of children with SLE examining these types of outcomes. Candell Chalom, et al.6 described the long-term educational, vocational and socioeconomic status and quality of life of 64 lupus patients with disease onset in childhood from their paediatric rheumatology center, followed up after a mean of 13 years. These authors found that most patients were living on relative low incomes (< $30 000 USD per year), and many still lived with their parents. Our study also shows that patients with adolescent SLE were more likely, although not significantly, to be living below the poverty line than the matched adult-onset group. This finding may be partially explained by younger age individuals being less established in permanent jobs or just beginning in pay scales of their careers. However, this may indicate a potential risk factor for juvenile lupus patients which should have further follow-up, because poverty has been identified as a negative long-term prognostic factor in SLE by us and others.25,26

A two-fold increase in mortality of adolescent-onset SLE patients seen in this study was unexpected and disturbing. Overall survival for children and adolescents with SLE has improved from 5- and 10-year survival of 60–78%27,28 in the 1970s, to 94–100% 5-year and 85% 10-year survival3,6 in 2000. However, these data come from patient cohorts cared for in paediatric rheumatology multidisciplinary clinics, which provide coordinated careful patient routine follow-up, patient education and transition to adult healthcare services; this type of care may have a positive impact on long-term survival. In contrast, Levy, et al.29 studied the outcome of 118 children with SLE followed in paediatric units of public hospitals in Paris and suburbs as well as some children seen in adult medical units. They found that 23 (19%) of these patients died, a mean of 7.6 years after disease onset. The authors suggest that the higher rate of mortality in their study may be related to poor socioeconomic status and treatment non-compliance among patients who died. A more recent study of 31 children with SLE from Chandigarh, India, demonstrated a very high mortality rate of 32% after 10 years of follow-up, related to late referrals and delay in diagnosis of disease.30 The issue of increased mortality amongst children and adolescents with SLE is concerning, and deserves further study in larger cohorts, with consideration of factors of healthcare services, socioeconomic background and continuity of care through adolescent transition.

This study has a number of limitations. Due to the inclusion criteria of the LUMINA study (age ≥16 years and ≤5 years of disease duration at entry) and the fact that all the LUMINA patients were seen in adult rheumatology clinics, we were not able to study children with SLE onset prior to 11 years of age, thus the data focus on adolescent-onset disease. The numbers of adolescent-onset patients in the LUMINA study were relatively small, which represents an issue of power for some of the analyses presented. The higher number of African-American patients in the adolescent-onset SLE patients may influence the results, as some studies have indicated differences in outcomes based on patient ethnicity. The current patient follow-up time among studied patients is relatively short [4.4 (2.9) years overall], preventing a more comprehensive assessment of longer term outcomes. We would hope to continue to capture these patients as the LUMINA study continues, allowing for 10- and 15-year follow-ups.

In conclusion, the severity of adolescent-onset SLE, as shown by persistence of active disease over long periods of time, results in more frequent disease damage, an increase in renal morbidity and may impact mortality. Young adults with adolescent-onset SLE were two times more likely to be living in poverty, which may represent an important negative prognostic factor for these patients. These findings suggest that an aggressive approach to the treatment of adolescent-onset SLE, coupled with educational, vocational and transition support might be important measures to improve outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants from the Child and Family Research Institute, BC Children’s Hospital (salary support for L Tucker), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases #R01-AR42503, the General Clinical Research Center Grants #M01-RR02558 (UTH-HSC) and M01-RR00032 (UAB), the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR/NIH) RCMI Clinical Research Infrastructure Initiative (RCRII) award 1P20RR11126 (UPR-MSC) and a Fellowship from Rheuminations, Inc. (UAB).

References

- 1.Petty RE, Laxer RM. Systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Cassidy JT, Petty RE, Laxer RM, Lindsley CB, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Rheumatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsiever Saunders; 2005. pp. 342–391. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tucker LB, Menon S, Schaller JG, Isenberg DA. Adult- and childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of onset, clinical features, serology, and outcome. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:866–872. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/34.9.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miettunen PM, Ortiz-Alvarez O, Petty RE, et al. Gender and ethnic origin have no effect on longterm outcome of childhood onset systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1650–1654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunner HI, Silverman ED, To T, et al. Risk factors for damage in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: cumulative disease activity and medication use predict disease damage. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:436–444. doi: 10.1002/art.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacks S, White P. Morbidity associated with childhood systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:941–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Candell Chalom E, Periera B, Cole R, et al. Educational, vocational, and socioeconomic status and quality of life in adults with childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2004;2:207–226. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alarcon GS, Roseman J, Bartolucci AA, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: II. Features predictive of activity early in its course. LUMINA Study Group. Lupus in minority populations, nature versus nurture. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1173–1180. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199807)41:7<1173::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uribe AG, McGwin G, Reveille JD, Alarcon GS. What have we learned from a 10-year experience with the LUMINA (Lupus in Minorities; Nature vs. nurture) cohort? Where are we heading? Auto-immun Rev. 2004;3:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–1277. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertoli AM, Alarcón GS, Calvo-Alén J, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic us cohort. Clinical features, course, and outcome in patients with late-onset disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1580–1587. doi: 10.1002/art.21765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alarcon GS, Friedman AW, Straaton KV, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: III. A comparison of characteristics early in the natural history of the LUMINA cohort. LUpus in Minority populations: NAture vs. Nurture. Lupus. 1999;8:197–209. doi: 10.1191/096120399678847704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Department of CommerceBureau of the Census. Current population reports, series P-23, no. 28 and series P-60. no, 68 and subsequent years. Washington, DC: Housing and Household Economic Statistics Division; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman HN. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason 1G, Sarason BR, editors. Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engle EW, Callahan LF, Pincus T, Hochberg MC. Learned helplessness in systemic lupus erythematosus: analysis using the Rheumatology Attitudes Index. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:281–286. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilowsky I. Dimensions of illness behaviour as measured by the Illness Behaviour Questionnaire: a replication study. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90123-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang MH, Socher SA, Larson MG, Schur PH. Reliability and validity of six systems for the clinical assessment of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:1107–1118. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Goldsmith CH, et al. The reliability of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:809–813. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Font J, Cervera R, Espinosa G, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in childhood: analysis of clinical and immunological findings in 34 patients and comparison with SLE characteristics in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:456–459. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.8.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruperto N, Buratti S, Duarte-Salazar C, et al. Health-related quality of life in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus and its relationship to disease activity and damage. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:458–464. doi: 10.1002/art.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravelli A, Duarte-Salazar C, Buratti S, et al. Assessment of damage in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a multicenter cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:501–507. doi: 10.1002/art.11205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutiérrez-Suárez R, Ruperto N, Gastaldi R, et al. A proposal for a pediatric version of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index based on the analysis of 1,015 patients with juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2989–2996. doi: 10.1002/art.22048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lilleby V, Flato B, Forre O. Disease duration, hypertension and medication requirements are associated with organ damage in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tucker LB, Cabral DA. Transition of the adolescent patient with rheumatic disease: Issues to consider. Ped Clin North Am. 2005;52:641–652. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Sanchez ML, et al. Systemic lupus in three ethnic groups: XIV. Poverty, wealth, and their influence on disease activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:73–77. doi: 10.1002/art.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meller S, Homey B, Ruzicka T. Socioeconomic factors in lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:242–246. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King KK, Kornreich HK, Bernstein BH, et al. The clinical spectrum of systemic lupus erythematosus in childhood. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20(2 Suppl):287–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meislin AG, Rothfield NF. Systemic lupus erythematosus in childhood: analysis of 42 cases with comparative data in 200 adult cases followed concurrently. Pediatrics. 1968;42:37–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy M, Montes de Oca M, Claude-Babron M. Unfavorable outcomes (end-stage renal failure/death) in childhood onset systemic lupus erythematosus A multicenter study in Paris and its environs. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1994;12:S63–S68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh S, Kumar L, Joshi K. Mortality patterns in childhood lupus-10 years experience in a developing country. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:462–465. doi: 10.1007/s100670200116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]