Abstract

Increasing evidence suggests that acetaminophen has unappreciated anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Drugs that affect oxidant and inflammatory stress in the brain are of interest because both processes are thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disease. The objective of this study is to determine whether acetaminophen affects the response of brain endothelial cells to oxidative stress. Cultured brain endothelial cells are pretreated with acetaminophen and then exposed to the superoxide-generating compound menadione (25 µM). Cell survival, inflammatory protein expression, and antioxidant enzyme activity are measured. Menadione causes a significant (p<0.001) increase in endothelial cell death as well as an increase in RNA and protein levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1, macrophage inflammatory protein alpha, and RANTES. Menadione also evokes a significant (p<0.001) increase in the activity of the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD). Pretreatment of endothelial cell cultures with acetaminophen (25–100 µM) increases endothelial cell survival and inhibits menadione-induced expression of inflammatory proteins and SOD activity. In addition, we document, for the first time, that acetaminophen increases expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2. Suppressing Bcl2 with siRNA blocks the pro-survival effect of acetaminophen. These data show that acetaminophen has anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects on the cerebrovasculature and suggest a heretofore unappreciated therapeutic potential for this drug in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease that are characterized by oxidant and inflammatory stress.

Keywords: cerebroprotective, anti-oxidant, endothelial cells, acetaminophen

Introduction

Acetaminophen (N-acetyl-p-aminophenol) is one of the most widely used over the counter antipyretic and analgesic drugs. The molecular mechanisms of action of acetaminophen are controversial and still poorly understood. Although it is both antipyretic and analgesic, it has traditionally not been classified as a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) because of its weak anti-inflammatory properties. The conclusion that acetaminophen is a weak inhibitor of prostaglandin (PG) synthesis, and thus inflammation, is based on studies in which prostaglandin synthesis is measured in homogenized tissues. However, in cellular systems acetaminophen can inhibit prostaglandin endoperoxide H2 synthase (PGHS) with IC50 values in the range of 4–200 µM (Graham et al., 1999; Kis et al., 2005; Schildknecht et al., 2008). Acetaminophen’s mode of action is dependent on cell type and experimental condition. It can inhibit the formation of PGE2 in the central nervous system (CNS) but not in platelets (Greco et al., 2003; Lages and Weiss, 1989; Muth-Selbach et al., 1999). It can inhibit PGHS synthesis in intact cells and not in cell homogenates (Lucas et al., 2005). Also, the possible pro- and anti-inflammatory actions of acetaminophen are complex because high dose acetaminophen administration initiates a series of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cascades. For example, acetaminophen (300 mg/kg) increases expression of proinflammatory mediators, interleukin (IL) IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), macrophage inhibitory protein-1 alpha (M1P-1α), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) as well as the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-13 (Dambach et al., 2006; Gardner et al., 2003; Yee et al., 2007). It is likely that there are other, as yet, unidentified biochemical targets for both the toxic and therapeutic actions of acetaminophen.

In overdose toxicity there is early hepatic microvascular injury in response to acetaminophen toxicity. Acetaminophen-induced sinusoidal endothelial cell injury precedes hepatocellular injury, supporting the hypothesis that sinusoidal endothelial cells are an early and direct target for acetaminophen (Ito et al., 2003). However, a role for the vasculature as a target of acetaminophen in the therapeutic dose range has not been examined. The microvasculature of the brain plays an important role as a modulator of neuronal function in health and disease (Farkas et al., 2000). Thus, the effects of acetaminophen on the brain may in part be mediated by the cerebral microcirculation. In this regard, prostaglandin production, both basal and response to lipopolysaccharide stimulation, in cerebral endothelial cells is inhibited by acetaminophen (Kis et al., 2005). Also, expression of COX-3, a new acetaminophen-sensitive isoform, is very high in brain, with cerebral endothelial cells showing the highest level of COX-3 expression (Kis et al., 2003). Taken together, these data support the idea that the cerebrovasculature is an important site of action for acetaminophen.

There is considerable interest in drugs that affect oxidative homeostasis in the brain because oxidative stress is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of many neurodegenerative diseases. Increasing evidence suggests that acetaminophen has unappreciated anti-oxidant properties. For example, acetaminophen can protect dopamingeric neurons from 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+)-induced toxicity in mitochondria by scavenging reactive oxygen species (Maharaj et al., 2004). Also, administration of acetaminophen to rats significantly attenuates quinolinic acid-induced superoxide generation (Marharaj et al., 2006). Acetaminophen has been shown to be a potent scavenger of peroxynitrite (Schildknecht et al., 2008). The cerebral microvasculature is source of reactive oxygen species including nitric oxide in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (Aliev et al., 2002; Dorheim et al., 1994). However, the antioxidant effects of acetaminophen on the brain microcirculation have not been explored.

The objectives of this study are to determine the effects of acetaminophen on brain endothelial cell survival and inflammatory factor expression when exposed to oxidative stress.

Materials and methods

2.1 Brain endothelial cell cultures

Rat brain endothelial cells were obtained from rat brain microvessels, as previously described (Diglio et al., 1993). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% glutamine and 1% antibiotics in a humidified 5% CO2, 95% O2 air incubator at 37°C. The purity of the endothelial cultures was confirmed using antibodies to endothelial cell surface antigen Factor VIII. Cells (passages 7–10) were replaced with serum-free media prior to treatments.

2.2 Measurement of cell survival by MTT assay

After treatment with various agents, cells were washed with phosphate buffer (PBS) and incubated with the MTT reagent 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2–5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide. Cells were incubated with the MTT reagent (1:40 dilution) for 5–10 min at 37°C. The cells convert the MTT reagent to formazon which is quantified by colorimetric assay (Cell Titer 95 Aqueous solution cell proliferation assay, Promega, Madison, WI). The formazon product was read at 490 nm. In each experiment, the number of control cells i.e. viable cells not exposed to any treatment was defined as 100%.

2.3 Detection of cytokines and chemokines

Antibodies from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) were used for Indirect ELISA measurements to detect MIP-1 α (ab9781), RANTES (ab9783), IL-1α (ab10747), IL-1β (ab9787), and TNFα (ab10863) released into the supernatant. Supernatants (100µl) collected from brain endothelial cells after various treatments were coated in 96-well immulon 2HB (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) flat bottom plates with sodium bicarbonate buffer (0.1 M) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The plates were blocked by 1% bovine serum albumin solution and incubated at 37°C for 45 min. The plates were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (1:1,000) diluted in bicarbonate buffer and unbound antibodies removed by extensive washing. 200 µl of secondary antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA 1:1,000 dilution) was added and the reaction incubated for 45 min at 37°C, in the dark. The reaction was developed by adding 200 µl/well of o-phenylene diamine H2O2 (Pierce, Chemicon, CA, USA) for 20 min. Optical density was measured at 450 nm and quantified using a microplate ELISA reader (BIO-RAD). Samples were assayed in triplicate.

2.4 Determination of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

Endothelial cell cultures were rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), scraped and total protein extracted using lysis buffer containing 0.1% SDS, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 and 0.5% phenylmethyl sulfonylfluoride. Protein was determined by the Bradford method using Bio-Rad protein reagents. Total SOD activity was determined at 550 nm by measuring the inhibition of xanthine/xanthine oxidase-mediated reduction of 2,3,bis(2-methoxy-4nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT; 0.5 mM xanthine in 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.8, 0.1 mM EDTA, xanthine oxidase sufficient to produce a slope of 0.025, 50 µM XTT, 25°C) (Ukeda et al., 1997; Zubkova and Robaire, 2004). One unit of SOD activity is defined as the enzyme activity needed to inhibit 50% of XTT reduction. Manganese SOD activity was assessed by performing the above experiment in the presence of 50 mM NaCN to inhibit CuZnSOD. Copper-zinc SOD activity was determined by measuring the difference between total and MnSOD activities.

2.5 Bcl2 RNA silencing

Brain endothelial cells were transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) for Bcl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) or scrambled siRNA (negative control). Transfection reaction was prepared with 120 pmol/ml of Bcl2 siRNA or scrambled siRNA in 100 µl of serum free media. Xtreme gene transfection reagent (6.5 µl) (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) was also diluted in 93.5 µl of serum-free media and the two mixtures were combined and incubated for 20 min at room temperature for complex formation. Brain endothelial cells were plated at 65% confluence and after 18 h rinsed and incubated in fresh DMEM media containing 10% FBS, antibiotics and glutamine. Forty eight hours post transfection, cells were treated with 100 µM acetaminophen for 8 h and then incubated with 25 µM menadione to induce oxidative stress. After 3 h of incubation with menadione, cell survival was assayed with MTT reagent. The number of control cells i.e. viable cells not exposed to any treatment was defined at 100%. Bcl2 silencing was detected by RT-PCR. Total RNA extracted from the cells treated with siRNA was reverse transcribed with Bcl2 specific primers and PCR products visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel using UV trans-illumination.

2.6 RT-PCR analysis of mRNA

Total RNA was extracted from the treated endothelial cells using the Trizol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA (1 µg) was reverse transcribed using oligo dT primers (Roche Applied Science) and amplified by PCR (2 min-95 ° C, 35 cycles of 15 sec- 94° C and 30 sec-57 ° C) using a Mastercycler system (Eppendorf). Primers used for PCR are shown in Table 1. The PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel using UV trans-illumination. Band intensities were quantified using the Quantity-One software (BioRad) and expressed graphically as intensity units, which is the average intensity over the area of a band.

Table 1.

Primers

| Gene | Orientation | Sequence | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bcl2 | Left primer Right primer |

GTCACCAACTGGGACGATA TCTCAGCTGTGGTGGTGAAG |

331 |

| MIP-1α | Left primer Right primer |

CAGAACATTCCTGCCACCTGCAAA AGGAATGTGCCCTGAGGTCTTTCA |

197 |

| RANTES | Left primer Right primer |

AGTGTGTGCCAACCCAGAGAAGAA TAGCATCTATGCCCTCCCAGGAAT |

191 |

| IL-1α | Left primer Right primer |

ACGGCTGAGTTTCAGTGAGACCTT AGGTGTAAGGTGCTGATCTGGGTT |

98 |

| IL-1β | Left primer Right primer |

AGCAGCTTTCGACAGTGAGGAGAA TCTCCACAGCCACAATGAGTGACA |

182 |

| TNF-α | Left primer Right primer |

ATGATCCGAGATGTGGAACTGGCA AATGAGAAGAGGCTGAGGCACAGA |

98 |

| β-actin | Left primer Right primer |

GTCACCAACTGGGACGATA TCTCAGCTGTGGTGGTGAAG |

380 |

| GAPDH | Left primer Right primer |

TCTGCATCTGGCAAAGTGGAGACT TTGAACTTGCCGTGGGTAGAGTCA |

101 |

2.7 Protein expression

Protein was extracted from brain endothelial cells using lysis buffer containing 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100 and 0.5% phenylmethyl sulfonylfluoride. Equal amounts of protein were run on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, transferred on to a PVDF membrane, blocked with 5% milk solution (non-fat dry milk in TBST for 2h) and immuno-blotted with Bcl2 (1:500) and GAPDH (1:1000) for 2h. The blots were washed extensively, followed by the addition of respective IgG coupled with horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA 1/5,000 dilution). Membranes were developed with chemiluminescence reagents (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

2.8 Statistical analysis

Data from each experiment are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests for multiple samples were performed. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05.

Results

3.1 Acetaminophen increases cell survival in cultured brain endothelial cells

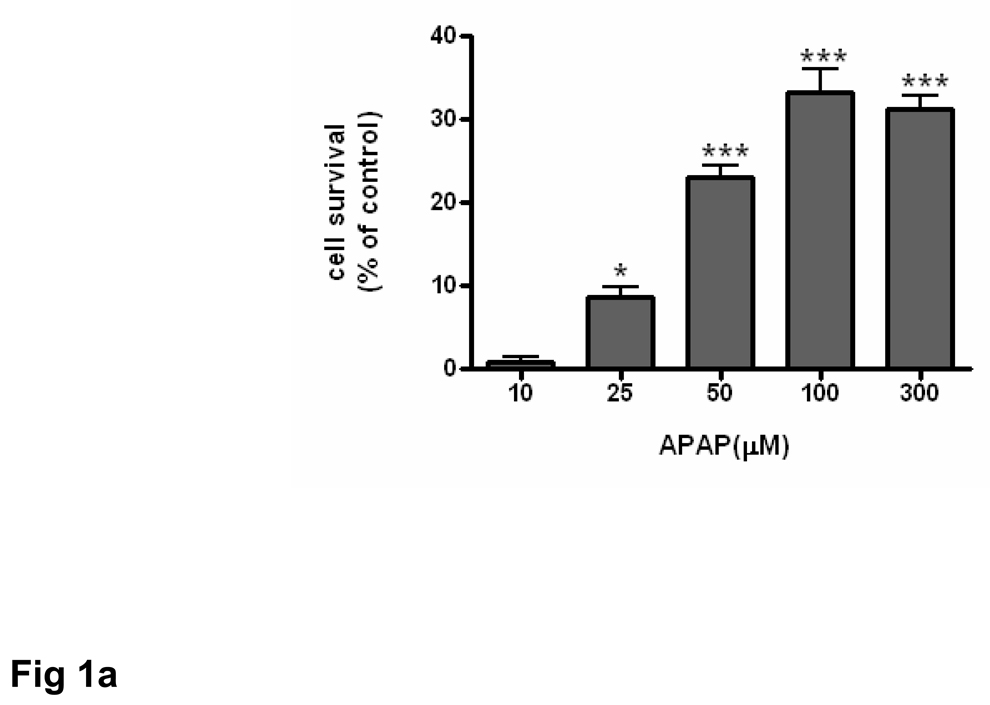

The ability of acetaminophen to affect the viability and proliferation of brain endothelial cells in culture was evaluated by MTT assay. Brain endothelial cells were incubated with varying concentrations (10 –300 µM) of acetaminophen for 8 h. There was a dose-dependent increase in cell number that was significant (p<0.05) at 25 µM acetaminophen and highly significant (p<0.001) at concentrations of 50 µM acetaminophen or higher (Fig. 1a).

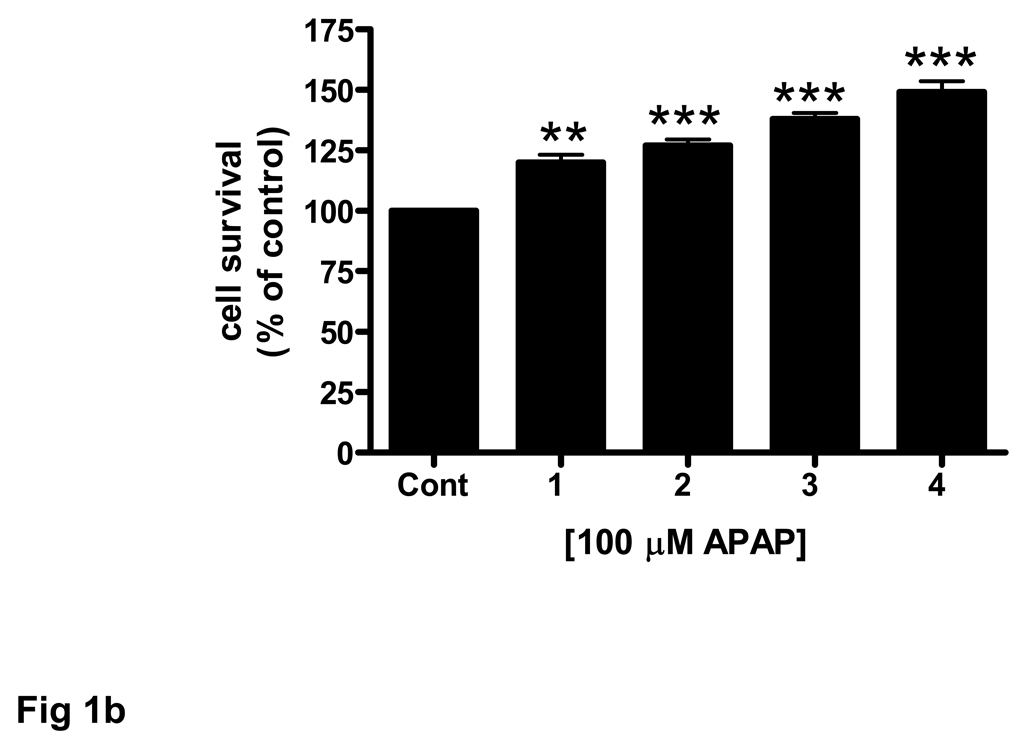

Fig. 1. Acetaminophen increases endothelial cell survival.

Brain endothelial cells (passages 7–10) were treated with acetaminophen (APAP) and cell survival was evaluated by MTT assay. In each experiment, the number of control cells i.e. viable cells not exposed to any treatment, was defined as 100%. (a) Endothelial cells were incubated with 0–300 µM of acetaminophen and cell survival measured.

*p<0.05 vs. control; ***p<0.001 vs. control.

(b) Brain endothelial cells were incubated with 100 µM APAP for 1 to 4 pretreatment periods. Each treatment period was 8 h. The number of control cells i.e. viable cells not exposed to any treatment, was defined as 100%.

**p<0.01 vs. control; ***p<0.001 vs. control.

Data are mean ± SD from 3 separate experiments.

The effect of acetaminophen on endothelial cell cultures was enhanced when cells were exposed to multiple drug pretreatments. Compared to a single 8 h acetaminophen treatment two (16 h) to four (32 h) pretreatments significantly (p<0.001) increased endothelial cell number (Fig. 1b).

3.2 Oxidative stress and oxidative-induced cell death of cultured endothelial cells is decreased by acetaminophen

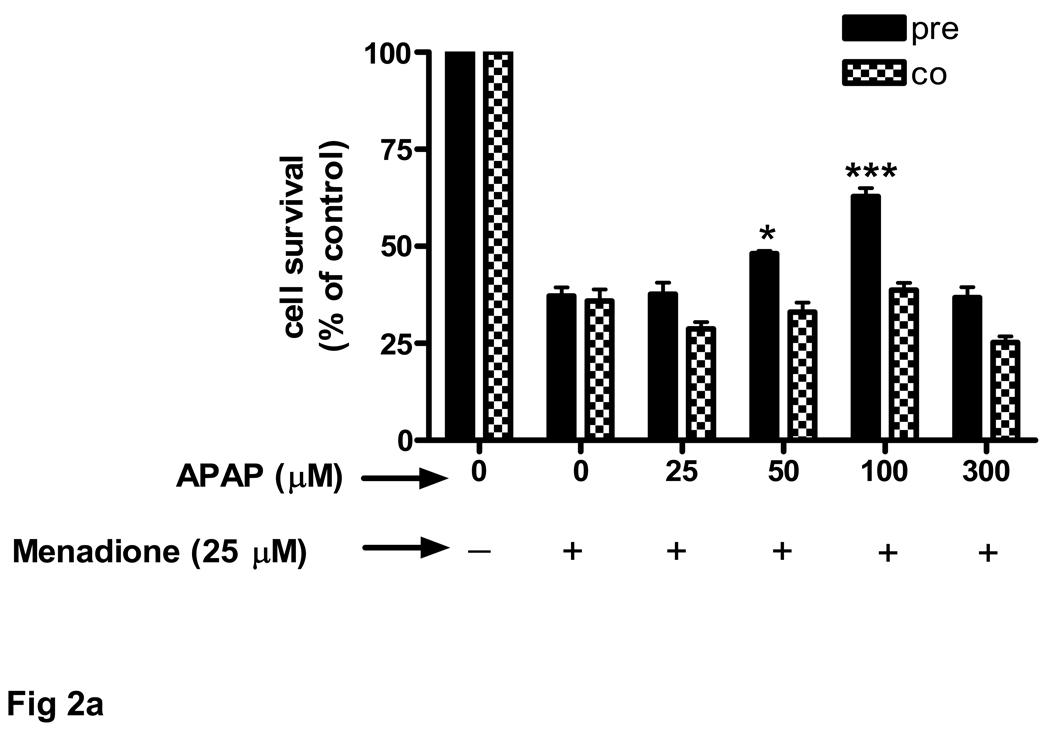

Cultured brain endothelial cells were treated with menadione to induce oxidative stress. Menadione in vitro releases reactive oxygen species, including superoxide. Incubation of cultured endothelial cells with 25 µM menadione for 3 h caused a 63% decrease in cell survival (Fig. 2a). Pretreatment of endothelial cells (24 h) with acetaminophen significantly (p<0.05) increased cell survival at 50 µM and further at 100 µM (p<0.001). At 300 µM acetaminophen showed toxicity. Interestingly, acetaminophen was ineffective at improving cell survival when administered at the same time as menadione (Fig. 2a).

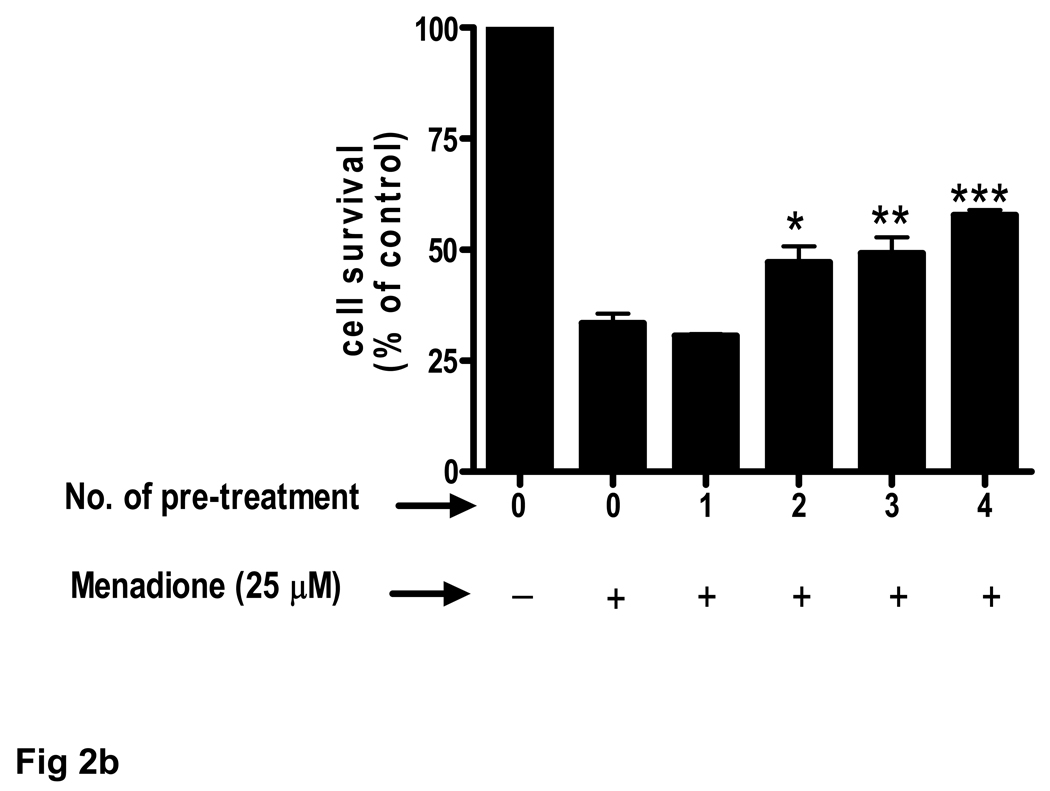

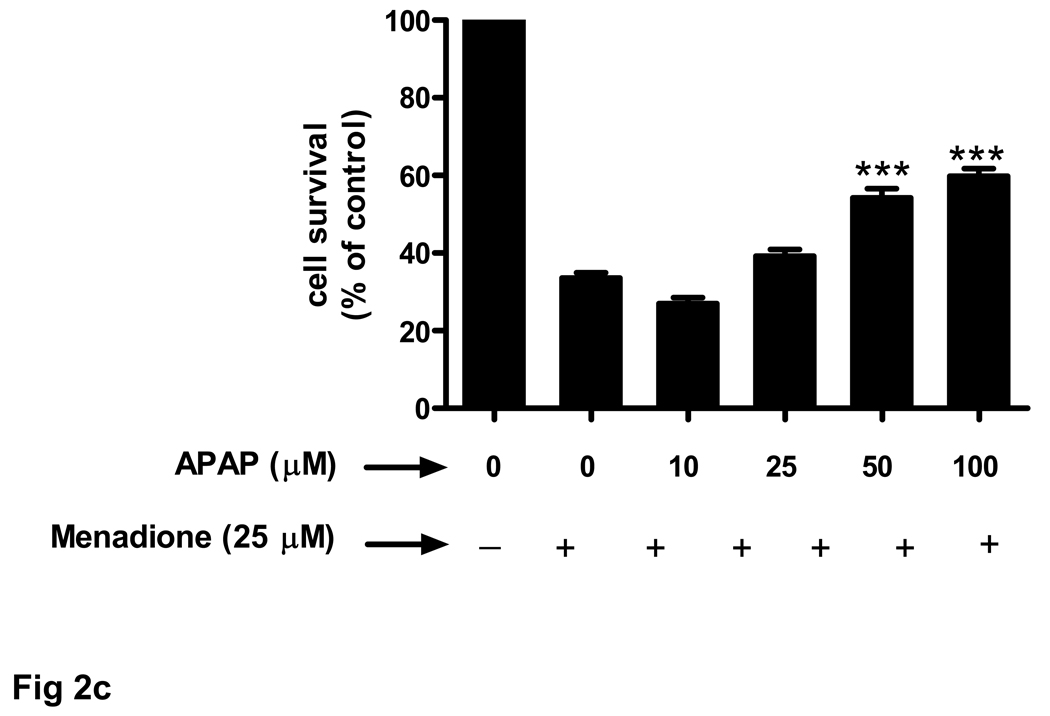

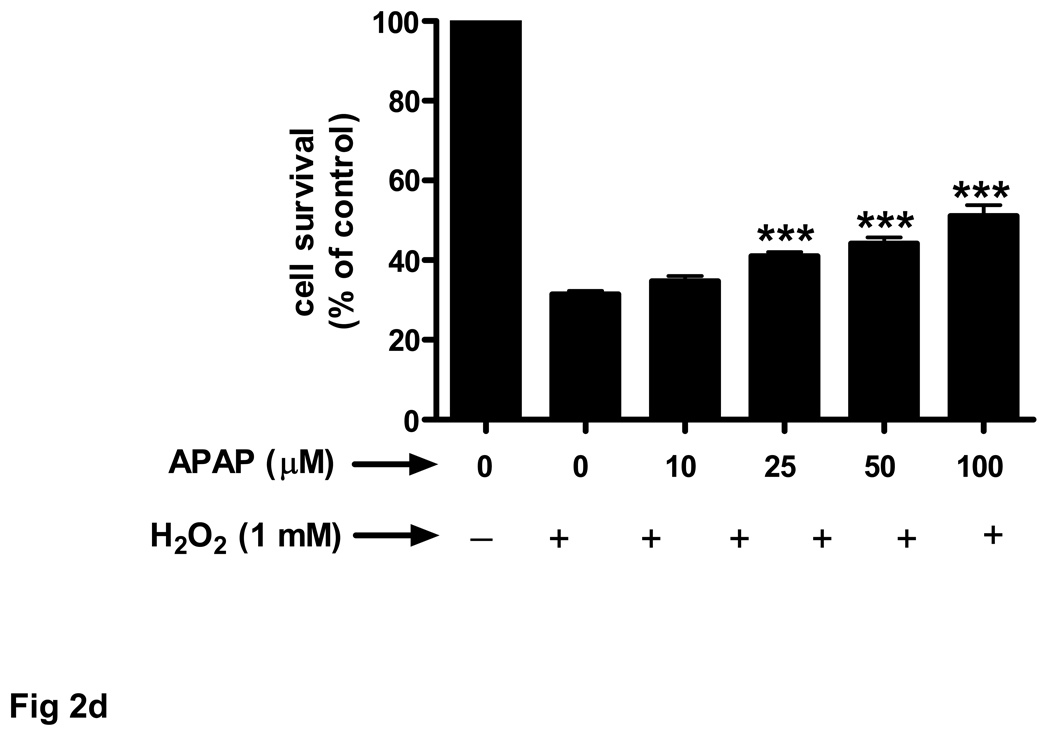

Fig. 2. Endothelial cell survival in response to oxidative stress increases with acetaminophen pre-incubation.

Brain endothelial cells were oxidatively challenged with 25 µM menadione for 3 h and cell viability was determined with MTT assay. The number of control cells i.e. viable cells not exposed to any treatment, was defined as 100%. (a) Brain endothelial cells were either pre-treated for 24 h ( ) with acetaminophen (APAP) (0–300 µM) and then exposed to menadione or co-incubated (

) with acetaminophen (APAP) (0–300 µM) and then exposed to menadione or co-incubated ( ) with APAP and menadione.

) with APAP and menadione.

*p<0.05 vs. menadione alone; ***p<0.001 vs. menadione alone.

(b) Brain endothelial cells received 1 to 4 pretreatments of 100 µM acetaminophen (APAP) prior to 3 h exposure to menadione (25 µM). Each treatment period was 8 h.

*p<0.05 vs. menadione alone; **p<0.01 vs. menadione alone; ***p<0.001 vs. menadione alone.

(c) Rat brain endothelial cells were exposed to 4 pretreatments (32 h) of varying doses (10–100 µM) of acetaminophen (APAP) and then incubated with 25 µM of menadione for 3 h.

***p<0.001 vs. menadione alone.

(d) Rat brain endothelial cells were exposed to 4 pretreatments (32 h) of varying doses (10–100 µM) of acetaminophen and then incubated with 1 mM H2O2 for 3 h.

***p<0.001 vs. H2O2 alone.

Data are mean ± SD from 3 separate experiments.

The ability of acetaminophen to improve cell survival upon exposure to menadione was enhanced when cells were exposed to multiple drug pretreatments. Compared to a single 8 h acetaminophen treatment two (16 h) to four (32 h) pretreatments significantly (p<0.001) increased endothelial cell number (Fig. 2b). The protective effect of a 32 h pretreatment was dose-dependent and highly significant (p<0.001) at 50 and 100 µM acetaminophen (Fig. 2c).

Experiments to determine the effect of menadione and acetaminophen on antioxidant enzyme activity in brain endothelial cells showed that the oxidant-stressor menadione caused a significant (p<0.001) increase in the activity of both MnSOD and CuZnSOD (Table 2). Pre-treatment of endothelial cells with increasing concentrations of acetaminophen (25 µM – 300 µM) caused a dose-dependent decrease of SOD activity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of acetaminophen on antioxidant enzyme activities in brain endothelial cells exposed to oxidative stress

| Enzyme Units/mg protein |

Control | Menadione (men) |

25µM APAP + men |

50µM APAP + men |

100µM APAP + men |

300µM APAP + men |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MnSOD | 6.01±1.67 | 16.21±3.64a | 11.91±1.47 | 10.16±3.72 | 8.20±0.54b | 5.27±0.91b |

| CuZnSOD | 14.73±5.30 | 19.99±2.31 | 12.84±6.28 | 10.03±4.29 | 14.52±4.05 | 8.81±3.09 |

| TSOD | 20.74±6.16 | 36.20±4.38a | 24.75±5.19 | 20.19±2.55 | 22.73±3.72b | 14.08±2.80b |

Brain endothelial cells were pretreated (32 h) with acetaminophen (APAP) and incubated with 25 µM of menadione for 3 h. Endothelial cell cultures were washed, scraped and protein extracted. One unit is defined as the amount of SOD required to inhibit the XTT reduction 50%. Values represent mean ± SEM from 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate.

p<0.01 vs. control;

p<0.001 vs. menadione alone.

We also evaluated the effects of another oxidant stressor, H2O2, on endothelial cell survival. Treatment of brain endothelial cell cultures with 1 mM H2O2 for 3 h evoked a 69% decrease in cell survival (Fig. 2d). Pretreatment with acetaminophen (25–100 µM) for 32 h prior to H2O2 resulted in a significant (p<0.001), dose-dependent increase in cell survival compared to cells treated with H2O2 alone (Fig. 2d).

3.3 Acetaminophen regulates cytokine and chemokines secretion in brain endothelial cells

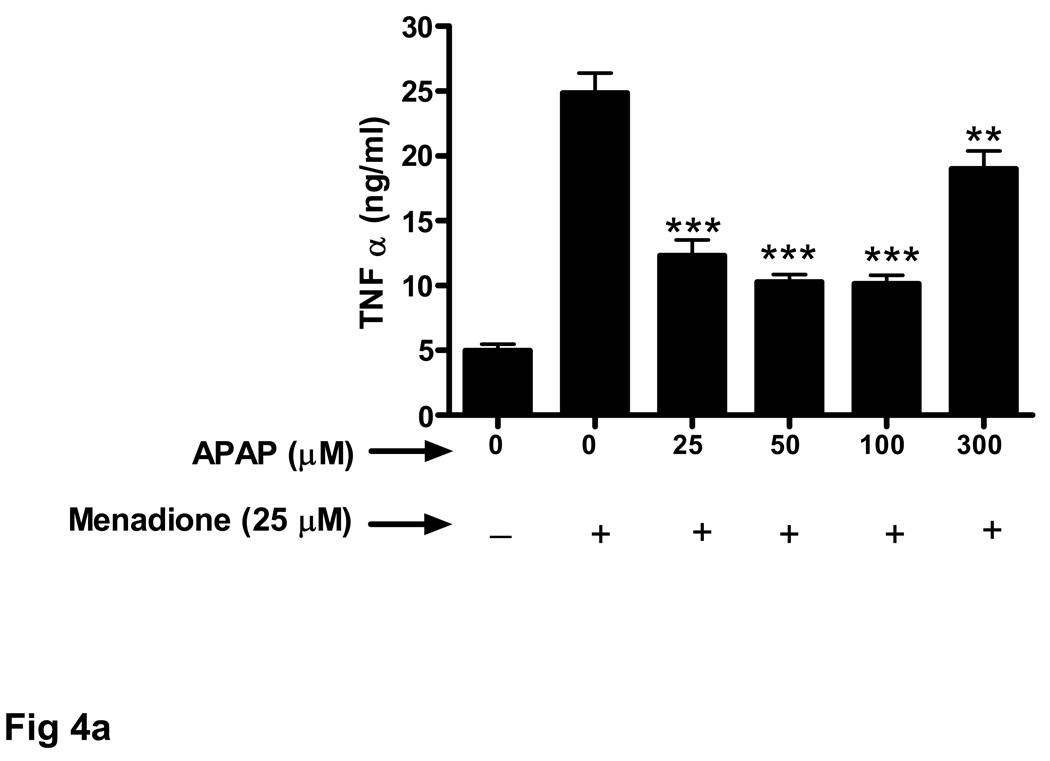

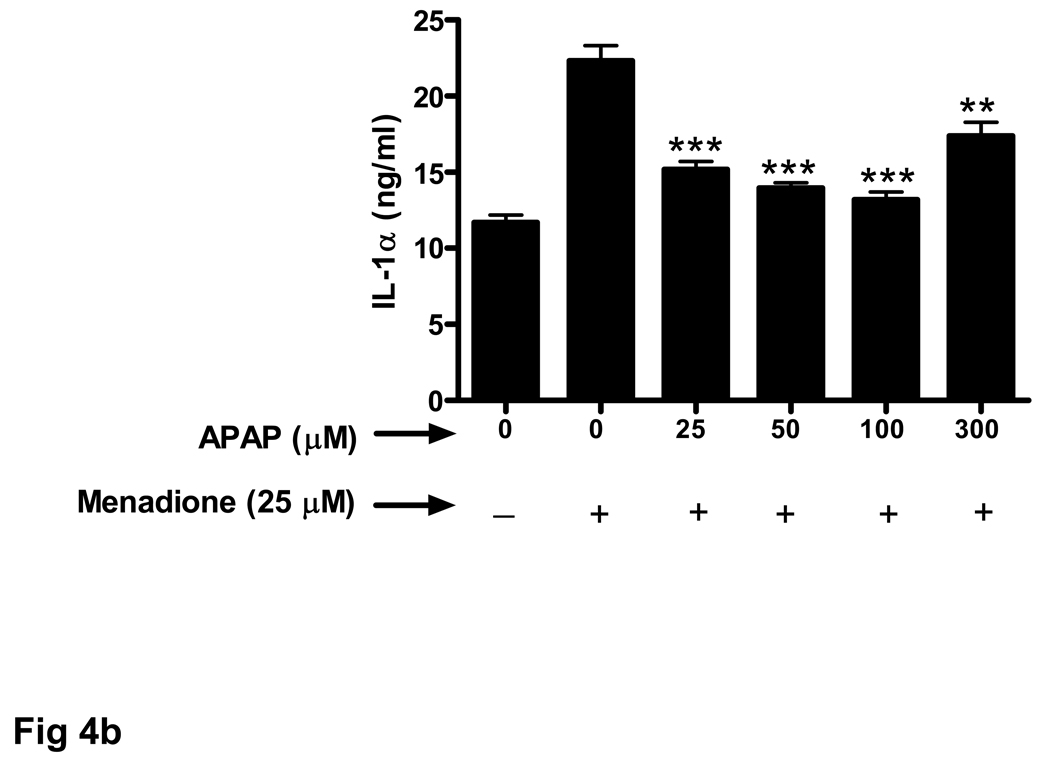

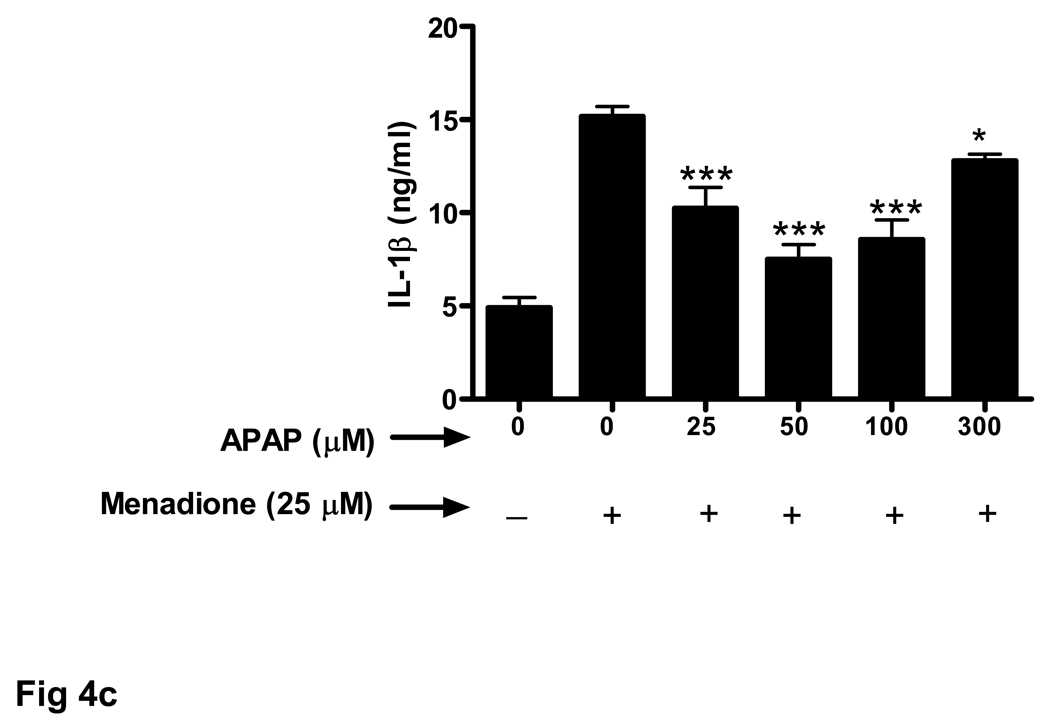

Endothelial cells release a variety of cytokines and chemokines when challenged with inflammatory proteins or other noxious stimuli including oxidant stress. Exposure of brain endothelial cells to 25 µM menadione for 3 h resulted in a large increase (5 fold) in release of TNFα (Fig. 3a). Pretreament (32 h) of endothelial cells with acetaminophen (25–100 µM) significantly decreased expression of TNFα.

Fig. 3. Oxidative stress-related increase in cytokine secretion is decreased by acetaminophen.

Brain endothelial cells were pretreated (32 h) with acetaminophen (APAP) and incubated with 25 µM of menadione for 3 h. Supernatants of endothelial cell cultures were analyzed by ELISA for the presence of cytokines (a) TNFα, (b) IL-1α, and (c) IL-1β.

*p<0.05 vs. menadione alone; **p<0.01 vs. menadione alone; ***p<0.001 vs. menadione alone.

Data are mean ± SD values from 3 separate experiments.

Treatment with a high dose of acetaminophen (300 µM) was much less effective at reducing TNFα secretion (Fig. 3a). The effect of acetaminophen on menadione-induced release of cytokines was similar for IL-1α (Fig. 3b) and IL-1β (Fig. 3c).

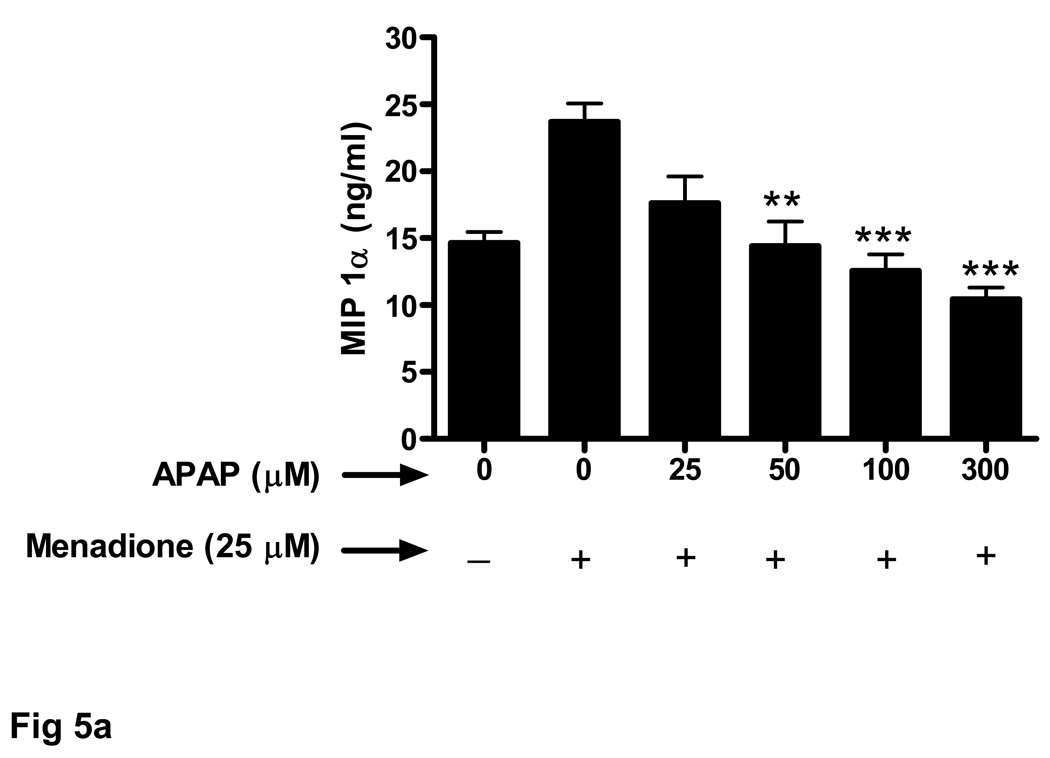

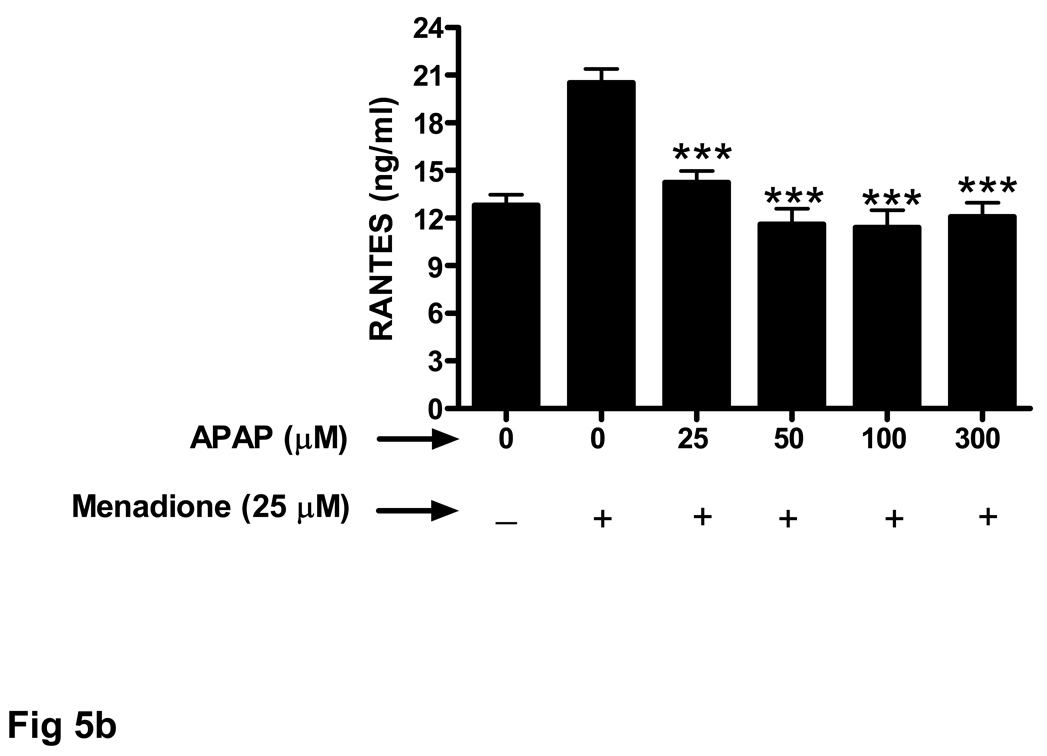

The ability of acetaminophen pretreatment to also decrease chemokine secretion from endothelial cells exposed to menadione was evaluated. Similar to the results obtained for the cytokines (TNFα, IL-1α, IL-1β) mendione exposure increased release of chemokines MIP-1α (Fig. 4a) and RANTES (Fig. 4b). Increasing doses of acetaminophen (25 –300 µM) decreased menadione-induced chemokine secretion. In contrast, to the effect of 300 µM acetaminophen on cytokine release shown in Figure 3, the same dose of acetaminophen was effective at decreasing the amount of MIP-1α (Fig. 4a) and RANTES (Fig. 4b) released in response to menadione.

Fig. 4. Oxidative stress-related increase in chemokine secretion is decreased by acetaminophen.

Brain endothelial cells were pretreated (32 h) with acetaminophen (APAP) and incubated with 25 µM of menadione for 3 h. Supernatants of endothelial cell cultures were analyzed by ELISA for the presence of chemokines (a) MIP-1α and (b) RANTES.

**p<0.01 vs. menadione alone; ***p<0.001 vs. menadione alone.

Data are mean ± SD values from 3 separate experiments.

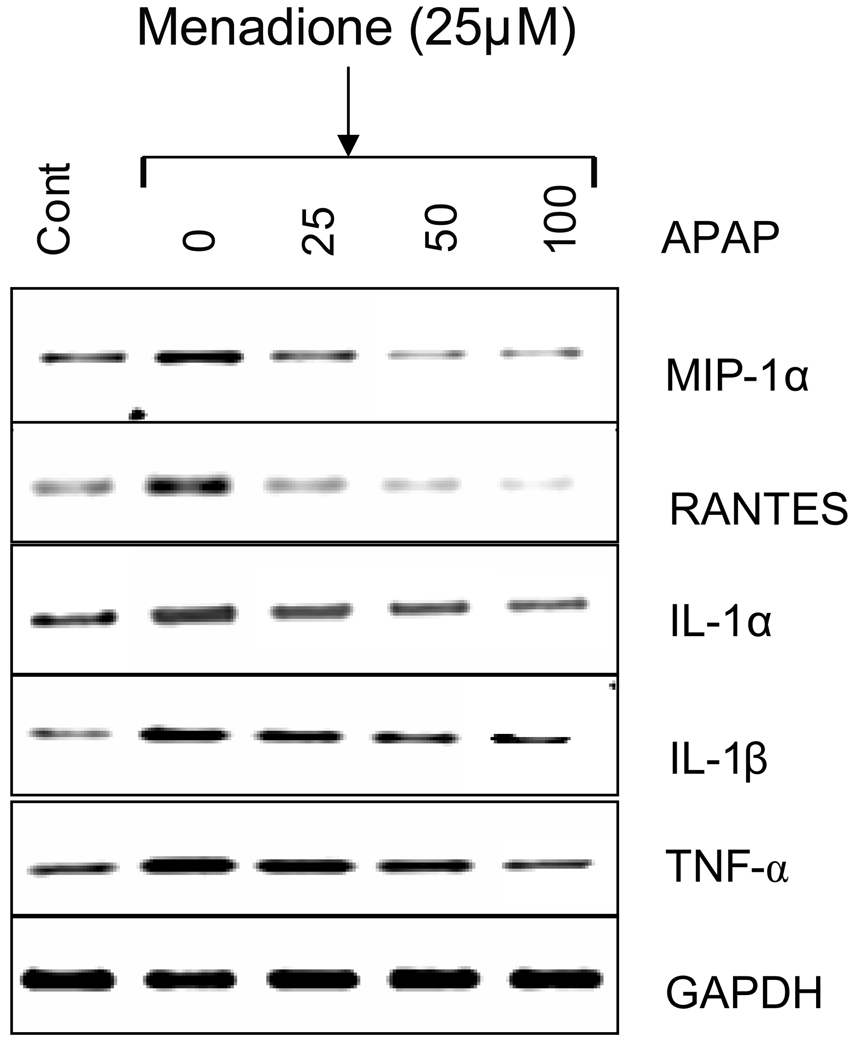

The effect of acetaminophen pretreatment on menadione-induce cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression was evaluated. Similar to the data obtained at the protein level, menadione exposure significantly (p<0.05–0.001) increased (1.84 to 4.23 fold) expression of MIP-1α, RANTES, IL-1α, IL-1β, TNFα in brain endothelial cell cultures compared to untreated cells (Fig. 5). Pretreatment (32 h) of cultures with acetaminophen (25 –300 µM) decreased menadione-induced expression. The fold change in mRNA expression is shown in Table 3.

Fig. 5. Effect of acetaminophen on menadione-induced expression of cytokine and chemokine mRNA.

Brain endothelial cells were pretreated (32 h) with varying concentrations (0–100 µM) acetaminophen (APAP) and incubated with 25 µM menadione for 3 h. Total RNA was extracted and RT-PCR performed with specific primers (MIP-1α, RANTES, IL-1α, IL-1β, TNFα) and PCR amplified products visualized (n=3). The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used to confirm loading equivalency between lanes.

Data are mean ± SD from 3 separate experiments; a representative blot is shown

Table 3.

Effect of acetaminophen on menadione-induced expression of cytokines and chemokines

| Gene | Men | Men + 25 µM APAP |

Men + 50 µM APAP |

Men + 100 µM APAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIP-1α | 1.92 ± 0.29 | 1.26 ± 0.75 | 1.14 ± 0.40 | 0.77 ± 0.26 |

| RANTES | 1.84 ± 0.26 | 1.62 ± 0.27 | 1.30 ± 0.06 | 0.85 ± 0.18 |

| IL-1α | 2.3 ± 0.56 | 1.76 ± 0.28 | 1.45 ± 0.32 | 1.45 ± 0.31 |

| IL-1β | 2.93 ± 0.51 | 2.09 ± 0.29 | 1.79 ± 0.08 | 1.6 ± 0.14 |

| TNF-α | 4.23 ± 1.68 | 3.14 ± 0.63 | 2.3 ± 0.20 | 1.92 ± 0.30 |

Quantitation of RT-PCR data shown in Figure 6. Brain endothelial cells were pretreated with acetaminophen (APAP) (0-100µM) for 32 h and then incubated with 25 µM of menadione (Men) for 3 h. RNA was extracted, reverse transcribed, and amplified with gene specific primers. The PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel using UV trans-illumination. Band intensities were quantified using the Quantity-One Software (BioRad) and expressed as intensity units, which is the average intensity over the area of a band. Data show fold induction relative to control (n=3).

3.4 Acetaminophen stimulates expression of Bcl2 in cultured brain endothelial cells

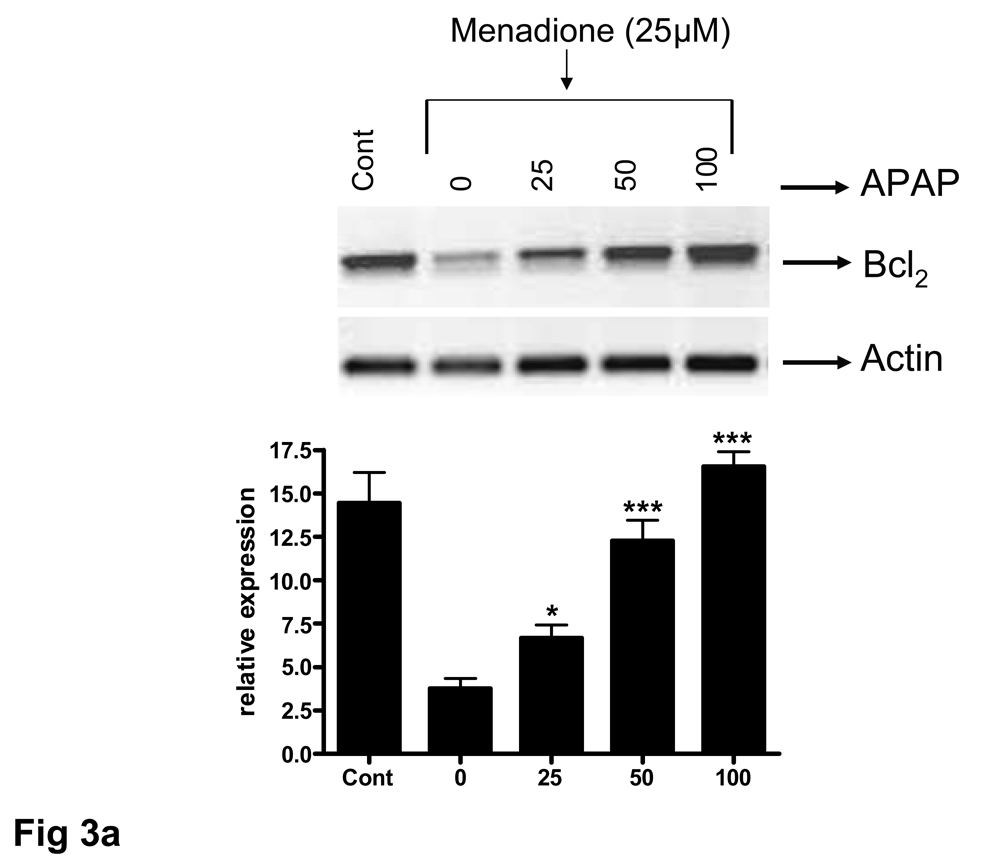

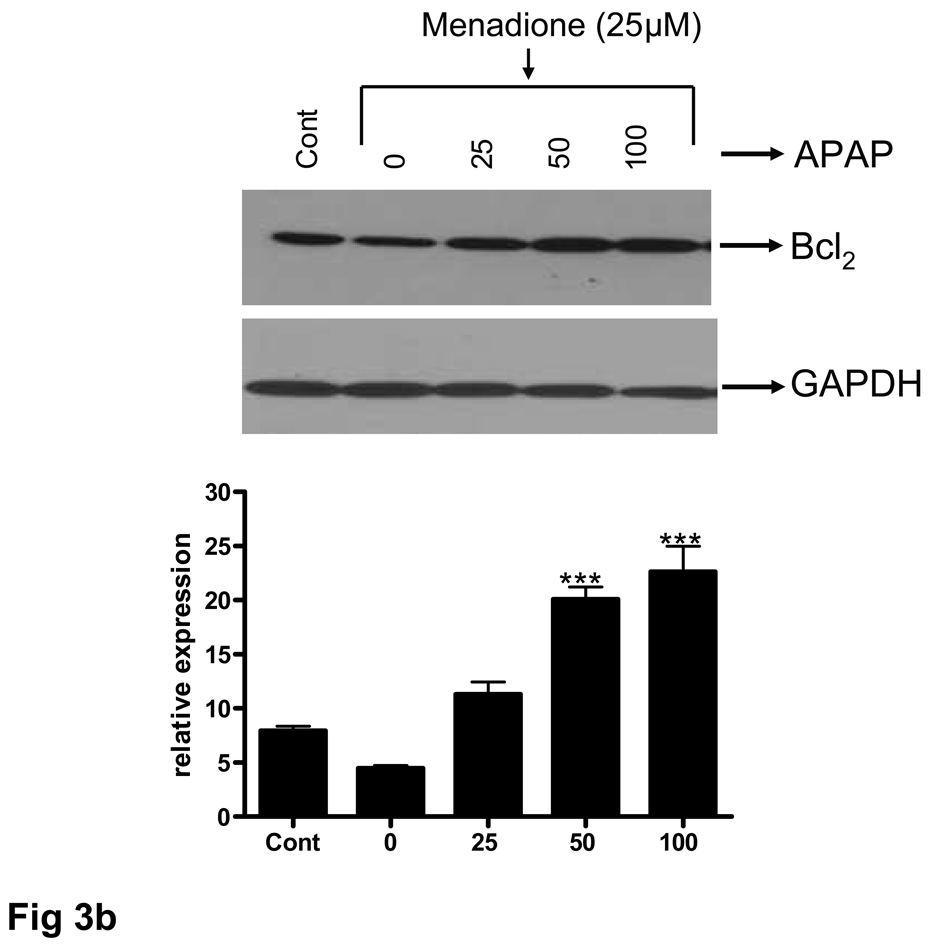

The ability of acetaminophen to affect expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 was examined at both RNA and protein levels. Brain endothelial cells were pretreated with 25–100 µM acetaminophen for 32 h, RNA extracted, and RT-PCR performed. A PCR amplified product corresponding to Bcl2 was demonstrable as a discrete band at 331 bp. There was a basal level of Bcl2 expression in untreated endothelial cell cultures that was significantly (p<0.001) reduced by a 3 h exposure to menadione (25 µM) (Fig. 6a). Pretreatment of endothelial cell cultures with acetaminophen (25 – 100 µM) resulted in a significant (p<0.0.5 – 0.001) 1.7 to 4.5 fold increase in Bcl2 expression compared to levels expressed in cells treated with menadione alone or compared to levels expressed in control cultures. (Fig. 6a). Western blot analysis of the Bcl2 expression at the protein level showed overall a similar pattern (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6. Acetaminophen induces expression of Bcl2 in brain endothelial cells.

Brain endothelial cells were pretreated (32 h) with acetaminophen (APAP) and incubated with 25 µM of menadione for 3 h. (a) Total RNA was extracted and RT-PCR performed with specific primers. PCR amplified products corresponding to Bcl2 were demonstrable as discrete bands at 331 bp. The housekeeping gene actin was used to confirm loading equivalency between lanes. Quantitation of densitometric scans from 3 separate experiments is shown in lower panel.

###p<0.001 vs. control; ap<0.001 vs. control; *p<0.05 vs. menadione alone; ***p<0.001 vs. menadione alone.

(b) Total protein was extracted and western blots performed using antibodies specific for Bcl2. A western blot representative of 3 separate experiments is shown. Antibodies to GAPDH were used to confirm loading equivalency between lanes. Quantitation of densitometric scans from 3 separate experiments is shown in lower panel.

ap<0.001 vs. control; ###p<0.001 vs. control; #p<0.05 vs. control; **p<0.01 vs. menadione alone;***p<0.001 vs. menadione alone.

Data are mean ± SD from 3 separate experiments; a representative blot is shown

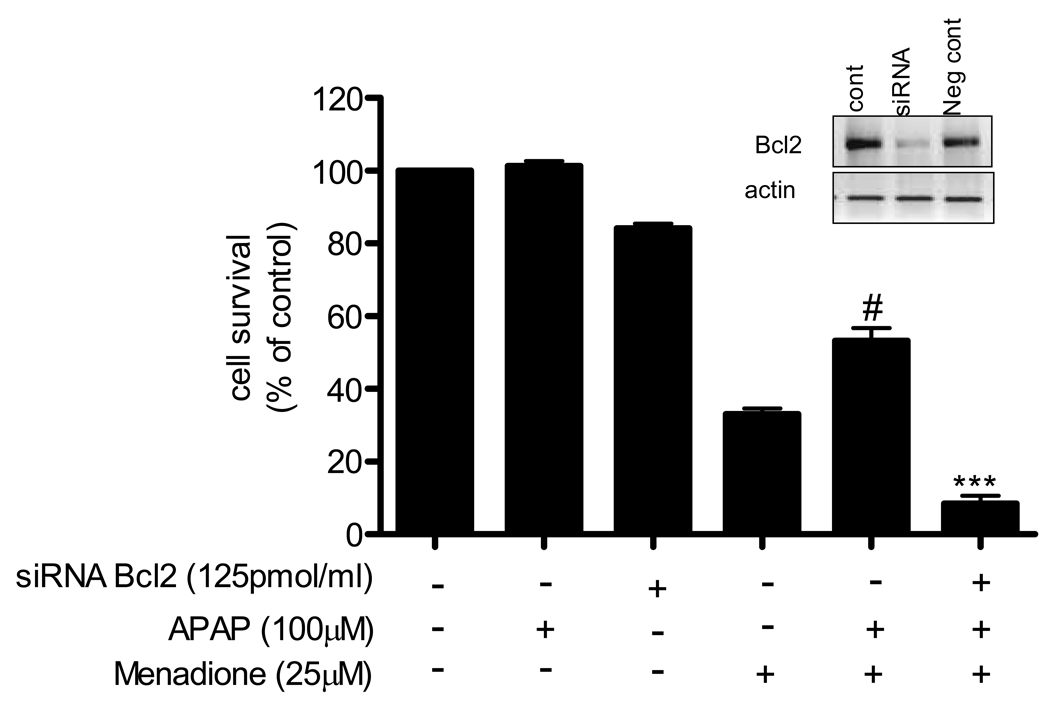

To determine if the acetaminophen-mediated increase in Bcl2 was responsible for the protective effect of acetaminophen on brain endothelial cells exposed to menadione, we silenced expression of the Bcl2 gene. The efficiency of Bcl2 siRNA in suppressing the expression of Bcl2 was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis. Transfection of cells with siRNA resulted in silencing of the gene by 70% compared to negative controls (Fig. 7, inset). Introduction of siRNA or scrambled RNA for Bcl2 reduced (p<0.001) cell survival compared to untreated controls (bars 3–9).

Fig. 7. Silencing Bcl2 expression blocks protective effect of acetaminophen.

Brain endothelial cells were transfected with siRNA for Bcl2 or scrambled siRNA for 48 h. The cells were treated with 100µM of acetaminophen for 8 h and then exposed to 25 µM menadione for 3 h. Cell survival was assayed with MTT reagent. Survival in control (i.e. untreated) cultures was defined as 100%.

#p<0.001 vs. control; ap<0.001 vs. Bcl2siRNA; bp<0.001 vs. menadione alone.

Data are means ± SD values from 3 separate experiments.

Inset: Bcl2 expression in endothelial cells transfected with siRNA for Bcl2, scrambled siRNA (neg control), or in non-transfected cells (cont).

Brain endothelial cells were transfected with Bcl2 siRNA for 48 h, treated with acetaminophen (100 µM) for 8 h and then exposed to menadione (25 µM) for 3 h. Acetaminophen treatment significantly (p<0.001) increased survival of cells exposed to menadione, and that protective effect was blocked by silencing Bcl2 (Fig.7).

Discussion

In the present study we demonstrate that pretreatment of cultured endothelial cells with acetaminophen significantly increases survival of endothelial cells exposed to menadione and reduces menadione-induced superoxide dismutase activity. Also, treatment of cultured endothelial cells with menadione causes release of several inflammatory proteins including RANTES, MIP-1α, TNFα, IL-1α and IL-1β that is diminished by pretreatment of endothelial cells with acetaminophen. Part of the protective effect of acetaminophen on brain endothelial cells appears to be due to induction of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2.

Intake of large doses of acetaminophen results in severe hepatic necrosis (Gujral et al., 2002; James et al., 2003). Oxidative stress mediated by the metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone-imine is considered the main cause of acetaminophen-induced toxicity (Liu and Kaplowitz, 2006; Olaleye and Rocha, 2008). Mice deficient in superoxide dismutase are resistant to acetaminophen toxicity due to a reduction in activity of a key acetaminophen metabolizing enzyme (cytochrome p450 2E1) (Lei et al; 2006). In the brain, overdose of acetaminophen causes a dramatic decrease of glutathione levels, ascorbic acid levels and superoxide dismutase activity (Nencini et al., 2007).

The above documented toxic effects associated with oxidative stress are elicited in response to high doses of acetaminophen. However, several studies have indirectly demonstrated acetaminophen’s capacity to function as an antioxidant. During post-ischemia-reperfusion in the heart acetaminophen attenuates the damaging effects of peroxynitrite and hydrogen peroxide and limits protein oxidation (Merrill and Golberg, 2001; Jaques-Robinson et al., 2008). Acetaminophen is a phenolic compound which produces a clear inhibitory dose-response curve with peroxynitrite in its range of clinical effectiveness (Van Dyke et al., 1998). Nanomolar concentrations of peroxynitrite increase the activity of isolated PGHS and prostacyclin formation in endothelial cells that is inhibited by therapeutic doses of acetaminophen (Schildknecht et al., 2008). Interestingly, acetaminophen is ineffective at inhibiting PGHS when a more intense oxidative insult is used, suggesting that the direct scavengering properties of acetaminophen are weak. This is consistent with the results of the current study where we show a direct protective effect of acetaminophen on brain endothelial survival (Fig. 1) but an inability of acetaminophen when co-incubated with menadione to override the toxic effects of this oxidant stressor. Furthermore, our observation that pretreatment of endothelial cell cultures with acetaminophen enhances the drug’s protective effect against menadione-evoked toxicity is consistent with reports that repeated acetaminophen dosing produces an adaptive response of key antioxidant systems (O’Brien et al., 2000).

Regarding antioxidant effects in the brain, acetaminophen inhibits superoxide generation, lipid peroxidation and cell damage in the hippocampus in response to quinolinic acid (Maharaj et al., 2006). Acetaminophen also protects dopamingeric neurons in vitro from oxidative damage evoked by acute exposure to 6-hydroxydopamine or excessive levels of dopamine (Locke et al., 2008). Amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptide-induced oxidative stress is inhibited in hippocampal neurons and PC 12 cultures through reduction of lipid peroxidation and by lowering cytoplasmic levels of peroxides (Bisaglia et al., 2002).

Numerous studies have suggested a link between oxidative stress and vascular inflammation. In the current study we document that expression of inflammatory mediators by brain endothelial cells is increased in response to oxidative stress and that pretreatment of endothelial cells with acetaminophen decreases inflammatory protein (RANTES, MIP1α, TNFα, IL-1α, IL-1β) expression. The cytokines and chemokines of inflammation are a double-edged sword exerting both toxic and protective effects depending on context, location and timing. For example, interferon γ knockout mice appear protected against acetaminophen toxicity because of reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Ishida et al., 20002). On the other hand, TNF receptor knockout mice are significantly more sensitive to the hepatotoxic effects of acetaminophen than wild-type mice. In this regard, inflammation in the liver in response to acetaminophen contributes to both tissue pathology and regeneration (Gardner et al., 2003).

Inflammation has been implicated in the pathology and acetaminophen-mediated tissue damage. Treatment of mice with high dose acetaminophen results in centrilobular necrosis that is correlated with expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and nitrotyrosine staining (James et al., 2003). IL-1β is increased early in acetaminophen-induced toxicity and is a potent inducer of iNOS. Knockout mice that are deficient in both IL-10 and IL-4 are highly sensitive to the hepatotoxic effects of acetaminophen (Bourdi et al., 2007). In these animals there are reduced levels of liver glutathione and very high levels of several pro-inflammatory factors including TNFα, MIP-1α and IL-6. A causal role for these inflammatory factors in tissue injury is supported by data showing that neutralizing antibodies to IL-6 reverse the high sensitivity of these mice to acetaminophen (Bourdi et al., 2007). Thus, high levels of injurious pro-inflammatory proteins are released in response to high doses of acetaminophen. In contrast, our data show that low doses of acetaminophen can blunt noxious inflammatory protein release from cultured brain endothelial cells. Similar results have been shown in cultured neurons where acetaminophen blunts neuronal apoptosis through reduction of the inflammatory transcription factor NF-kappaB (Bisaglia et al., 2002). Unpublished work from our laboratory also shows that low dose acetaminophen reduces inflammatory protein release from neurons. The idea that low doses of acetaminophen are beneficial in the brain is supported by a recent study showing that acetaminophen improves cognitive performance on the Morris water maze test (Ishida et al., 2007).

For both oxidative and inflammatory mediators there are distinctly different responses to low dose vs. high dose acetaminophen. The nature of the response, protective vs. toxic, to acetaminophen is due to dose level. Using Bayesian networks for quantifying linkages between gene families Toyoshiba et al. 2006 show that at lower doses of acetaminophen the genes related to the oxidative stress signaling pathway do not interact with apoptosis-related genes. In contrast, at high doses there are significant interactions between genes related to oxidative stress and those involved in apoptosis. These results suggest that the effector molecules and mechanisms evoked by low vs. high doses of acetaminophen are qualitatively different.

The mechanism of action of acetaminophen is still unclear. The hepatotoxicity of high dose acetaminophen has traditionally been associated with necrosis (Gujral et al., 2002; James et al., 2003). However, high dose acetaminophen can also evoke apoptosis. The C-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) is thought to play a central role in acetaminophen-induced liver injury and as well as in injury of glioma cells (Bae et al., 2001; Nakagawa et al., 2008). In contrast, low doses of acetaminophen appear to be protective in cardiac myocytes exposed to reperfusion injury via inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and subsequent apoptotic pathway (Hadzimichalis et al., 2007).

A large number of proteins operate in concert to regulate apoptosis. Bcl2 is of particular interest as it has been reported that Bcl2 is protective against oxidative stress reducing cell death induced by reactive oxygen species (Hockenbery et al., 1993; Park and Hockenbery, 1996). In the current study, we show that pretreatment of brain endothelial cells with acetaminophen increases expression of Bcl2, at both mRNA and protein level, and is associated with increased cell survival. This is, to our knowledge, the first report of a direct effect of acetaminophen on Bcl2 expression.

Acetaminophen is a safe and effective analgesic/antipyretic drug at therapeutic doses, although its hepatotoxicity at high doses has been extensively studied and documented (Jaeschke, 2005). In contrast, few studies have explored possible cerebroprotective effects, despite increasing evidence that acetaminophen has anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties. Our in vitro studies on brain endothelial cells taken together with in vitro studies on neurons and in vivo work showing improved cognition with acetaminophen suggest a heretofore unappreciated therapeutic potential for this drug in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease that are characterized by oxidant and inflammatory stress.

Acknowledgements

Sources of support: This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG15964, AG020569 and AG028367) and McNeil Consumer and Specialty Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Grammas is the recipient of the Shirley and Mildred Garrison Chair in Aging. The authors gratefully acknowledge the secretarial assistance of Terri Stahl.

References

- Aliev G, Smith MA, Seyidov D, Neal ML, Lamb BT, Nunomura A, Gasimov EK, Vinters HV, Perry G, LaManna JC, Friedland RP. The role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of cerebrovascular lesions in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:21–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae MA, Pie JE, Song BJ. Acetaminophen induces apoptosis of C6 glioma cells by activating the c-Jun NH(2)-terminal protein kinase-related cell death pathway. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;60:847–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisaglia M, Venezia V, Piccioli P, Stanzione S, Porcile C, Russo C, Mancini F, Milanese C, Schettini G. Acetaminophen protects hippocampal neurons and PC12 cultures from amyloid beta-peptides induced oxidative stress and reduces NF-kappaB activation. Neurochem. Int. 2002;41:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(01)00136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdi M, Eiras DP, Holt MP, Webster MR, Reilly TP, Welch KD, Pohl LR. Role of IL-6 in an IL-10 and IL-4 double knockout mouse model uniquely susceptible to acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007;20:208–216. doi: 10.1021/tx060228l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambach DM, Durham SK, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Distinct roles of NF-kappaB p50 in the regulation of acetaminophen-induced inflammatory mediator production and hepatoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006;211:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diglio CA, Liu W, Grammas P, Giacomelli F, Wiener J. Isolation and characterization of cerebral resistance vessel endothelium in culture. Tissue and Cell. 1993;25:833–846. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(93)90032-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorheim MA, Tracey WR, Pollack JS, Grammas P. Nitric oxide synthase is elevated in brain microvessels in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;205:659–665. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas E, De Jong GI, Apro E, De Vos RA, Steur EN, Luiten PG. Similar ultrastructural breakdown of cerebrocortical capillaries in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson disease, and experimental hypertension. What is the functional link? Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2000;903:72–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner CR, Laskin JD, Dambach DM, Chiu H, Durham SK, Zhou P, Bruno M, Gerecke DR, Gordon MK, Laskin DL. Exaggerated hepatoxicity of acetaminophen in mice lack tumor necrosis factor receptor-1. Potential role of inflammatory mediators. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2003;192:118–130. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00273-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham GG, Day RO, Milligan MK, Ziegler JB, Kettle AJ. Current concepts of the actions of paracetamol (acetaminophen) and NSAIDs. Inflammopharmacology. 1999;7:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s10787-999-0008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco A, Ajmone-Cat MA, Nicolini A, Sciulli MG, Minghetti L. Paracetamol effectively reduces prostaglandin E2 synthesis in brain macrophages by inhibiting enzymatic activity of cyclooxygenase but not phospholipase and prostaglandin E synthase. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003;71:844–852. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujral JS, Knight TR, Farhood A, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H. Mode of cell death after acetaminophen overdose in mice: apoptosis or oncotic necrosis? Toxicol. Sci. 2002;67:322–828. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/67.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadzimichalis NM, Baliga SS, Golfetti R, Jaques KM, Firestein BL, Merrill GF. Acetaminophen-mediated cardioprotection via inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore-induced apoptotic pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;293:H3348–H3355. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00947.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenbery DM, Oltvai ZN, Yin XM, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell. 1993;75:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T, Sato T, Irifune M, Tanaka K, Nakamura N, Nishikawa T. Effect of acetaminophen, a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, on Morris water maze task performance in mice. J. Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:757–767. doi: 10.1177/0269881107076369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Kondo T, Oshima T, Fujiwara H, Iwakura Y, Mukaida N. A pivotal involvement of IFN-gamma in the pathogenesis of acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury. FASEB J. 2002;16:1227–1236. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0046com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Bethea NW, Abril ER, McCuskey RS. Early hepatic microvascular injury in response to acetaminophen toxicity. Microcirculation. 2003;10:391–400. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H. Role of inflammation in the mechanism of acetaminophen-induced hepatoxicity. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2005;1:389–397. doi: 10.1517/17425255.1.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LP, Mayeux PR, Hinson JA. Acetaminophen-induced hepatoxicity. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003;31:1499–1506. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.12.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaques-Robinson KM, Golfetti R, Baliga SS, Hadzimichalis NM, Merrill GF. Acetaminophen is cardioprotective against H2O2-induced injury in vivo. Exp. Biol. Med. 2008;233:1315–1322. doi: 10.3181/0802-RM-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kis B, Snipes JA, Isse T, Nagy K, Busija DW. Putative cyclooxygenase-3 expression in rat brain cells. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metabol. 2003;23:1287–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000090681.07515.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kis B, Snipes JA, Simandle SA, Busija DW. Acetaminophen-sensitive prostaglandin production in rat cerebral endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005;288:R897–R902. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00613.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lages B, Weiss HJ. Inhibition of human platelet function in vitro and ex vivo by acetaminophen. Thromb. Res. 1989;53:603–613. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(89)90150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei XG, Zhu JH, McClung JP, Aregullin M, Roneker CA. Mice deficient in Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase are resistant to acetaminophen toxicity. Biochem. J. 2006;399:455–461. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZX, Kaplowitz N. Role of innate immunity in acetaminophen-induced hepatoxicity. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2006;2:493–503. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke CJ, Fox SA, Caldwell GA, Caldwell KA. Acetaminophen attenuates dopamine neuron degeneration in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;439:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas R, Warner TD, Vojnovic I, Mitchell JA. Cellular mechanisms of acetaminophen: role of cyclo-oxygenase. FASEB J. 2005;19:635–637. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2437fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj DS, Saravanan KS, Maharaj H, Mohanakumar KD, Daya S. Acetaminophen and aspirin inhibit superoxide anion generation and lipid peroxidation, and protect against 1-methyl-4-phenyl pyridinium-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity in rats. Neurochem. Int. 2004;44:355–360. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(03)00170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj H, Maharaj DS, Daya S. Acetylsalicylic acid and acetaminophen protect against oxidative neurotoxicity. Metab. Brain Dis. 2006;21:189–199. doi: 10.1007/s11011-006-9012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill GF, Goldberg E. Antioxidant properties of acetaminophen and cardioprotection. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2001;96:423–430. doi: 10.1007/s003950170023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muth-Selbach US, Tegeder I, Brune K, Geisslinger G. Acetaminophen inhibits spinal prostaglandin E2 release after peripheral noxious stimulation. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:231–239. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199907000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa H, Maeda S, Hikiba Y, Ohmae T, Shibata W, Yanai A, Sakamoto K, Ogura K, Nogushci T, Karin M, Ichijo H, Omata M. Deletion of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 attenuates acetaminophen-induced liver injury by inhibiting C-Jun N-ternimal kinase activation. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1311–1321. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nencini C, Giorgi G, Micheli L. Protective effect of silymarin on oxidative stress in rat brain. Phytomedicine. 2007;14:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien PJ, Slaughter MR, Swain A, Birmingham JM, Greenhill RW, Elcock F, Bugelski PJ. Repeated acetaminophen dosing in rats: adaptation of hepatic antioxidant system. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2000;18:277–283. doi: 10.1191/096032700678815918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaleye MT, Rocha BT. Acetaminophen-induced liver damage in mice: effects of some medicinal plants on the oxidative defense system. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2008;59:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JR, Hockenbery DM. BCL-2, a novel regulator of apoptosis. J. Cell Biochem. 1996;60:12–17. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19960101)60:1<12::aid-jcb3>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildknecht S, Daiber A, Ghisla S, Cohen RA, Bachschmid MM. Acetaminophen inhibits prostanoid synthesis by scavenging the PGHS-activator peroxynitrite. FASEB J. 2008;22:215–224. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-8015com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshiba H, Sone H, Yamanaka T, Parham FM, Irwin RD, Boorman GA, Portier CJ. Gene interaction network analysis suggests differences between high and low doses of acetaminophen. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006;215:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukeda H, Maeda S, Ishii T, Sawamura M. Spectrophotmetric assay for superoxide dismutase based on tetrazolium salt 3’ -{1-[phenylamino)-carbonyl]-3,4-tetrazolium}-bis(4-methoxy-6-nitro)benzenesulfonic acid hydrate reduction by xanthine-xanthine oxidase. Anal. Biochem. 1997;251:206–209. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke K, Sacks M, Qazi N. A new screening method to detect water soluble antioxidants: acetaminophen (Tylenol ®) and other phenols react as antioxidants and destroy peroxynitrite-based luminol-dependent chemiluminescence. J. Biolumin. Chemilumin. 1998;13:339–348. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1271(199811/12)13:6<339::AID-BIO501>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee SB, Bourdi M, Masson MJ, Pohl LR. Hepatoprotective role of endogenous interleukin-13 in a murine model of acetaminophen-induced liver disease. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007;20:734–744. doi: 10.1021/tx600349f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubkova EV, Robaire B. Effect of glutathione depletion on antioxidant enzymes in the epididymis, seminal vesicles, and liver and on spermatozoa motility in the aging brown Norway rat. Biol. Reprod. 2004;71:1002–1008. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.028373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]