Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to assess whether providing a breastfeeding support team (BST) results in higher breastfeeding rates at 6, 12, and 24 weeks postpartum among urban low-income mothers.

Methods

Design: A randomized controlled trial with mother-infant dyads recruited from two urban hospitals. Participants: Breastfeeding mothers of full term infants who were eligible for Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) (n=328) were randomized to intervention (n=168) or usual care group (n=160). Intervention: The 24 week intervention included hospital visits by a breastfeeding support team (BST), home visits, telephone support, and 24 hour pager access. The usual care group received standard care. Outcome Measure: Breastfeeding status was assessed by self report at 6, 12, and 24 weeks postpartum.

Results

There were no differences in the sociodemographic characteristics between the groups: 87% were African American, 80% single, and 51% primiparous. Compared to the usual care group, more women reported breastfeeding in the intervention at 6 weeks postpartum, 66.7% vs. 56.9% OR 1.71 (95% CI 1.07, 2.76). The difference in rates at 12 weeks postpartum, 49.4% versus 40.6%, and 24 weeks postpartum, 29.2% versus 28.1%, were not statistically significant.

Conclusions

The intervention group was more likely to be breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum compared with usual care group, a time that coincided with the most intensive part of the intervention.

Keywords: breastfeeding, low-income mothers, randomized controlled trial, community intervention

The American Academy of Pediatrics1 recommends that infants be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life. Because of the nutritional and health benefits of human milk they recommend promoting breastfeeding aggressively among the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) recipients as the preferred feeding method. Healthy People 20102 and The Health and Human Services (HHS) Blueprint for Action on Breastfeeding3 also emphasized the advantages of breastfeeding and the need to direct interventions to low income, disadvantaged high-risk mothers. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with lower breastfeeding initiation (and lower rates across time). This is consistent with the inverse relationship between socioeconomic status and both infant morbidity and mortality.2-4

The most accurate breastfeeding rates currently available are found on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) website.5 Nationally, 74.2% of women from all sociodemographic groups initiate breastfeeding whereas 67.8% of WIC mothers initiate breastfeeding. At six months, 43.1% of all US women and only 34.2% of WIC mothers are still breastfeeding.

A variety of interventions have been tried, with limited success, to enhance breastfeeding rates among low income mothers.6-7 A best practice model to promote breastfeeding among low income women has not been identified, although interventions with nurses or peer counselors show promise.8 Nurses, whether in the hospital or in home, have also been shown to have a critical role in supporting breastfeeding.9-11 Community nurses have been found to be effective in promoting breastfeeding for extended intervals.9-10 Nurses have a combination of educational expertise, experience addressing psychosocial issues, treatment advice for unpleasant symptoms, and mother-baby assessment skills to enable effective assistance with breastfeeding.11-12

Initial work by the authors with a middle-income, well-educated group of breastfeeding mothers demonstrated the value of the community nurse.13 The first nursing interventions tested focused on four areas: providing psychosocial support, decreasing the unpleasant symptoms of breastfeeding (fatigue and nipple pain),14 breastfeeding education, and infant assessment and development.14-15 Community nursing support was associated with higher breastfeeding rates.13, 15-17 Concomitantly, national statistics indicated that strategies for helping low-income women breastfeed longer were important to healthier infant outcomes.2

As this research team was developing interventions to extend breastfeeding for low-income women, we hypothesized that adding a peer counselor to the nursing involvement would enhance the intervention in a way that would be culturally relevant and helpful in providing psychosocial support. Social support in the form of peer counselors and/or lay home visits has been shown to be very effective in increasing breastfeeding rates specifically for low-income women.18-19 The proposed intervention for this randomized controlled trial (RCT) combined strategies that the research team had documented as effective.13, 15-17 This unique intervention, known as the breastfeeding support team (BST) was designed to include a community nurse and a breastfeeding peer counselor. The new aspect of this intervention is that the combination of community nurse and peer counselor has not been previously studied in a large sample of low-income women. The intervention began in the hospital postpartum and continued visits and support were provided through 24 weeks postpartum. Previous pilot work with 41 women in the intervention supported its effectiveness in increasing breastfeeding though 16 weeks postpartum.17

Our hypothesis was that the BST would result in higher breastfeeding rates among low-income urban mothers at 6, 12, and 24 weeks postpartum.

METHODS

Design

This randomized controlled trial was designed to determine the effect the BST had on breastfeeding outcomes during the first 24 weeks postpartum. Breastfeeding mothers of full term infants who were eligible for WIC (n=328) were recruited from two urban hospitals. Following informed consent, baseline data were gathered by the community nurse who was blind to group assignment. The study statistician generated random assignments to groups using an SPSS algorithm and each mother was randomly assigned to the intervention or usual care group using the sealed envelope technique. Recruitment took place within 24 hours of vaginal birth and 48 hours of Cesarean birth. Inclusion criteria included: 1) singleton infant at least 37 weeks gestation; 2) breastfeeding intention by the mother; 3) English speaking mother; 4) WIC eligible family (determined by maternal self-report using the WIC questions regarding financial information); 5) available telephone access; and 6) geographically feasible address defined as within 25 miles of the birth hospital. Exclusion criteria included: 1) cranio-facial abnormalities in the infant, 2) positive drug screen for mother or infant, and 3) NICU admission immediately after birth. Breastfeeding subjects were identified from postpartum units of two urban hospitals, Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH), a university hospital, and Mercy Medical Center (MMC), a community hospital, in Baltimore, Maryland between October 2003 and December 2005. Johns Hopkins Hospital has approximately 1800 total births per year (65% are to low-income women). Mercy Medical Center has approximately 2550 births per year (80% to low income women). Both of these hospitals have excellent reputations for maternal/newborn care, but neither hospital was officially designated as one of the 79 Baby Friendly hospitals in the US.20 Subjects were randomized in blocks of ten within each hospital, which resulted in 168 mother-infant dyads in the intervention group, 160 in the usual care group.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university/hospital and the community hospital. A data safety and monitoring board was formed and met semi-annually. The data safety and monitoring board evaluated adverse events and found none attributable to the intervention.

Description of intervention

The BST provided a prescribed program of support and education for the first 24 weeks postpartum. The primary objective was to increase breastfeeding rates at 6, 12, and 24 weeks postpartum. This was supported by strategies designed to 1) strengthen maternal competence and commitment to breastfeeding; 2) provide parental education regarding breastfeeding; 3) provide/identify social support needed for continued breastfeeding; 4) emphasize ways to decrease fatigue and breast discomfort; and 5) foster linkages to community services and pediatric care that facilitated the maintenance of breastfeeding. The intervention was most intensive for the first four weeks postpartum, with continuing support through 24 weeks postpartum. The intervention group received daily hospital visits by both members of the BST until discharge. The BST also visited the intervention group two times in the home during the first week and a third visit at four weeks postpartum. The intervention group received telephone support through a scheduled telephone call (by the peer counselor) at least every two weeks through 24 weeks postpartum. Participants could reach the nurse by a pager 24 hours per day seven days a week (through 24 weeks postpartum). This schedule represents the minimum number of contacts. If in the community nurse's professional judgment, the mother warranted more support than prescribed, additional home visits or telephone support were provided. The professional nurse judgment was considered an integral part of the intervention, so flexibility in provision of nursing care via home visits or nursing telephone support based on professionally identified need was considered important and weekly team meetings were held in an effort to monitor and standardize the intervention across subjects.

Home visits by the BST lasted 45 – 60 minutes. Activities included education to facilitate successful breastfeeding, symptom management (fatigue, nipple pain, depressive feelings, and anxiety), and problem solving for psychosocial issues (partner and other support, return to work or school). Infants were weighed, measured, and professionally assessed at every home visit. If any concern was uncovered, the primary care provider was notified and mothers were encouraged to seek follow-up. Scheduled telephone support calls were provided by the peer counselor and averaged 20 minutes in duration. The calls consisted of discussing infant feeding, providing encouragement, assessing maternal wellbeing, and trouble-shooting potential problems.

Description of usual care

Immediately after delivery, all breastfeeding mothers admitted to each of these hospitals had access to an inpatient visit by a lactation consultant (LC). After discharge, a hospital-based LC was also available via a telephone “warm-line” (an answering machine checked at least every 24 hours). Once home, the participant could request an office visit with the LC.

Sample Size

This study was based on team's pilot work17 where participants were intensively followed for 12 weeks and followed for breastfeeding status until breastfeeding was terminated. Of the 41 participants enrolled, exclusive breastfeeding at 12 weeks postpartum occurred in 45% of the intervention group and 25% of the usual care group. We assumed that breastfeeding rates in both groups would drop by an additional 5% by 24 weeks (to 40% and 20% respectively). At these levels with an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 90%, the sample size needed to detect differences would be 119 in each group. Although we had very little attrition in the pilot work, allowing for 25% attrition, 160 in each group was necessary for adequate power at 24 weeks.

MEASURES

Data Collection and Management

Baseline data from the mother-infant dyads were collected by the community nurse prior to randomization. Longitudinal data were collected by telephone or during home visits either by the research assistant (usual care group) or peer counselor (intervention group). After recruitment, staff were no longer blinded to group assignment. During the postpartum period, the protocol was developed to reduce recall bias, maximize ability to maintain a relationship with subjects, and insure measurement of the outcome variable. Per schedule, attempts to collect data were made at biweekly intervals through 12 weeks and every fourth week through 24 weeks. An attempt consisted of a minimum of three phone calls to existing phone numbers. When phone attempts were unsuccessful, a home visit was made. Continued attempts were made to contact each participant to maximize our ability to follow these vulnerable hard to reach mothers. Even if attempts were repeatedly unsuccessful, staff continued to attempt to contact participants at least biweekly until a final determination of the outcome variable (when stopped breastfeeding) was made.

Breastfeeding Outcome Variable

Breastfeeding was a dichotomous variable (no=0, yes=1) identified in relation to data points at 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 24 weeks postpartum. To meet the definition of breastfeeding, the mothers had to have breastfed at least once within the previous 24 hours. In both recruitment hospitals, most infants were fed formula in the nursery before enrollment. Thus, there was never an opportunity to establish exclusive breastfeeding.

Computation of breastfeeding rates

Routine contact with the mother at prescribed intervals provided the basis for computing breastfeeding rates. When a mother reported that she had terminated breastfeeding, the breastfeeding stop date was elicited and documented.

For 34 mothers (10.4%) no breastfeeding information after enrollment was obtained. These mothers were assigned as having “not breastfed at all” and coded as not breastfeeding at all data points. There were no statistically significant demographic or baseline psychosocial variable differences between these 34 mothers and the other 294 mothers who provided breastfeeding data after baseline. If other breastfeeding mothers were lost to follow-up, the stop date was imputed based on the last contact. When there were missing data on breastfeeding information at a given contact point, retrospective data obtained at the next successful contact were substituted. For example, by 24 weeks, 234 mothers had stopped breastfeeding while 94 were still breastfeeding. Of these mothers, 140 (59.8%) had provided a breastfeeding stop date. For the remaining 94 mothers (51 in the intervention group and 43 in the usual care group), breastfeeding status at 6, 12, and 24 weeks was imputed by using the last contact date as breastfeeding discontinuation – another conservative approach. This approach effectively assumed that those who were most difficult to follow were least likely to breastfeed. The analysis of breastfeeding rates was based on an intention to treat model and represents the most conservative calculations and results for breastfeeding rates at measurement intervals.

Sociodemographic, Baseline, and Psychosocial Variables

At baseline, sociodemographic, behavioral and psychosocial measures were assessed by self-report. These data were used to describe the sample, compare groups, and provide co-variates for the logistic regression. Psychosocial variables (satisfaction with partner and other persons,21 depressive symptoms,22 state anxiety23) were useful in understanding the mothers, identifying patient safety issues, and determining similarity among the groups. All variables were measured with well-established instruments that had established support for reliability and valididy.21-23

ANALYTIC STRATEGY

At baseline, intervention and usual care group differences in sociodemographic, behavioral, health characteristics were compared using Chi-square statistics for categorical measures (age categories, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment, parity & breastfeeding experience, type of delivery). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test differences in mean maternal age, infant gestation age, and infant Apgar scores between intervention and usual care groups. Breastfeeding rates at the three follow-up periods were also compared to evaluate group differences using Chi-square statistics.

Bivariate analysis (using Chi-square statistics) compared breastfeeding rates with covariates, e.g. age categories, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment, parity and breastfeeding experience, and type of delivery. Finally, multiple logistic regression, adjusting for individual covariates at baseline was used to assess the relationship between the intervention and breastfeeding at 6, 12, and 24 weeks postpartum. The decision to include covariates in the multiple regression was based upon a significant association of the covariate with breastfeeding rate (p<0.05) or covariates that are traditionally associated with breastfeeding initiation rates and were gathered as study variables.

RESULTS

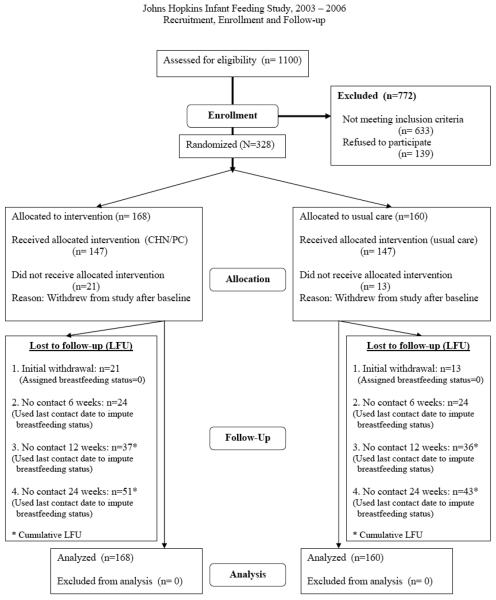

A total of 328 breastfeeding mothers were eligible and agreed to participate in this study (see Figure 1). The final sample reflected a 70.2% participation rate of the 467 eligible mothers who were approached (Figure 1). The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act prevented the authors from collecting information on those who did not consent to participate. Table 1 presents baseline sociodemographic characteristics. Participants were predominantly young (mean, 23 years), of African American or African descent, (87.2%) and single (79.6%). There was approximately equal distribution between primiparity (50.6%) and multiparity and the majority delivered vaginally (73.5%). Most (73.5%) had at least a high school education. At baseline, 64.4% described themselves as employed and 67.7% identified themselves as having no breastfeeding experience. Table 1 displays the sociodemographic characteristics at baseline in the total sample and by group. There were no significant differences between the two groups on sociodemographic characteristics at baseline. Further, there were no differences in psychosocial variables at baseline (satisfaction with partner and other persons, depressive symptoms, state anxiety). There was no difference in length of hospital stay between the groups (total sample mean 2.4 days, SD=0.9).

Figure 1.

Trial enrollment flow chart

Table 1.

Sociodemographics of Participants by Group at Baseline*

| Characteristics | Total (N=328) (JHU=210) (MMC=118) |

Intervention (n=168) |

Usual Care (n=160) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Participants | |||||||

| Age | 13-17 years | 33 | 10.1 | 20 | 11.9 | 13 | 8.1 |

| 18-19 years | 56 | 17.1 | 26 | 15.5 | 30 | 18.8 | |

| 20-24 years | 137 | 41.8 | 70 | 41.7 | 67 | 41.9 | |

| 25-34 years | 91 | 27.7 | 48 | 28.6 | 43 | 26.9 | |

| 35-43 years | 11 | 3.4 | 4 | 2.4 | 7 | 4.4 | |

| Mean age, years (± s.d.) | 23.1 (5.3) | 23.1 (5.3) | 23.2 (5.3) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | African American | 286 | 87.2 | 150 | 89.3 | 136 | 85.0 |

| White | 15 | 4.6 | 7 | 4.2 | 8 | 5.0 | |

| Latina | 13 | 4.0 | 5 | 3.0 | 8 | 5.0 | |

| Other | 14 | 4.3 | 6 | 3.6 | 8 | 5.0 | |

| Education | Below High School | 87 | 26.5 | 49 | 29.2 | 38 | 23.8 |

| High School/GED | 121 | 36.9 | 59 | 35.1 | 62 | 38.8 | |

| Some College | 83 | 25.3 | 47 | 28.0 | 36 | 22.5 | |

| College Grad/Grad degree | 37 | 11.3 | 13 | 7.7 | 24 | 15.0 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 56 | 17.1 | 33 | 19.6 | 23 | 14.4 |

| Single | 261 | 79.6 | 129 | 76.8 | 132 | 82.5 | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 11 | 3.4 | 6 | 3.6 | 5 | 3.1 | |

|

Employment and school status during pregnancy |

Employed & in school | 72 | 22.0 | 35 | 20.8 | 37 | 23.1 |

| Employed-NOT in school | 139 | 42.4 | 70 | 41.7 | 69 | 43.1 | |

| IN school-NOT employed | 60 | 18.3 | 33 | 19.6 | 27 | 16.9 | |

| NOT employed-NOT in School | 57 | 17.4 | 30 | 17.9 | 27 | 16.9 | |

|

Parity & Breastfeeding Experience |

Primipara, NO experience | 166 | 50.6 | 82 | 48.8 | 84 | 52.5 |

| 2nd+para, NO experience | 56 | 17.1 | 32 | 19.0 | 24 | 15.0 | |

| 2nd+para, Experience, Yes | 106 | 32.3 | 54 | 32.1 | 52 | 32.5 | |

| Delivery Type | Vaginal | 241 | 73.5 | 122 | 72.6 | 119 | 74.4 |

| Cesarean | 87 | 26.5 | 46 | 27.4 | 41 | 25.6 | |

| Infants | |||||||

| Mean gestational age | 38.9(1.2) | 38.8 (1.2) | 39.1 (1.2) | ||||

| 1 min Apgar | Mean Apgar score (± s.d.) | 8.0 (1.4) | 8.1 (1.3) | 7.8 (1.6) | |||

| 5 min Apgar | Mean Apgar score (± s.d.) | 8.9 (0.4) | 8.9 (0.4) | 8.9 (0.4) | |||

No statistical differences among groups were found.

Data were collected to describe the intervention. The modal number of hospital visits was one (median=1; range 0 - 8). The modal number of home visits was 3 (median=3; range 0 - 13). The mean number of telephone minutes spent with each mother was 83.6 (range 0 - 256). Table 2 details the number of hospital and home visits that were made. There were 13 participants who received no hospital visits (Table 2). This occurred because the participant signed the informed consent, hence enrolled, but asked the BST to return at another time. The participant may have been discharged earlier than usual or stated that she was too tired to complete the visit.

Table 2.

Hospital and Home Visits Made by the Intervention Team

| Number of Visits | Hospital Visits | Home Visits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Mothers |

Percent | Number of Mothers |

Percent | |

| 0 | 13 | 7.7% | 13 | 7.7% |

| 1 | 72 | 42.9% | 10 | 6.0% |

| 2 | 56 | 33.3% | 11 | 6.6% |

| 3 | 20 | 11.9% | 74 | 44.1% |

| 4 | 2 | 1.2% | 30 | 17.9% |

| ≥5 | 3 | 1.8% | 28 | 16.3% |

Table 3 shows the breastfeeding rates at a time period in total and by group. In comparing the intervention with the usual care group, 66.7% of the intervention group vs. 56.9% reported any breastfeeding at 6 weeks postpartum (p=0.05). In the intervention group, the rate of breastfeeding at 12 weeks postpartum was higher than in the usual care group (49.4% vs. 40.6%), a non-significant difference. Rates at 24 weeks postpartum were almost identical, 29.2% vs. 28.1%.

Table 3.

Breastfeeding rates at 6, 12, and 24 weeks postpartum

| Total (N=328) |

Intervention (Total Sample=168) |

Usual Care (Total Sample=160) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Breastfeeding |

% | Number Breastfeeding |

% | Number Breastfeeding |

% | p value | |

| At six week | 202 | 61.6 | 111 | 66.7 | 91 | 56.9 | 0.05 |

| At 12 week | 148 | 45.1 | 83 | 49.4 | 65 | 40.6 | 0.07 |

| At 24 week | 94 | 28.7 | 49 | 29.2 | 45 | 28.1 | 0.46 |

Table 4 displays the results from multiple logistic regression analyses for comparing breastfeeding rates at 6, 12, and 24 weeks postpartum between the two groups after adjusting for baseline factors associated with enhanced breastfeeding rates in the literature (maternal age, race, education, parity, and breastfeeding experience). At six weeks postpartum, the odds of breastfeeding in the intervention group were 1.72 times greater than those for mothers in the usual care group (p<.05). At 12 weeks, the odds of breastfeeding were in the intervention group were 1.58 times greater than those for mothers in the usual care group (p=.05). The differences were not statistically significant in comparing the two groups at 12 or 24 weeks postpartum.

Table 4.

Multiple logistic regressionA for intervention effects on breastfeeding rates at 6, 12 and 24 weeks postpartum

| Any breastfeeding | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 weeks | 1.72 | 1.07; 2.76 | 0.03 |

| 12 weeks | 1.58 | 1.00; 2.49 | 0.05 |

| 24 weeks | 1.14 | 0.69; 1.87 | NS |

Adjusted for baseline: maternal age, race, education, parity, and breastfeeding experience

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that breastfeeding rates in low-income mothers can be increased by an intensive community nurse peer counselor intervention. At 6 weeks postpartum, the intervention group had significantly higher breastfeeding rates. At 12 weeks postpartum, a greater proportion of mothers in the intervention group were breastfeeding, but group differences were not significant. At 24 weeks postpartum, breastfeeding rates in the two groups were similar. The findings of increased rates in this sample are similar to findings in earlier studies providing peer support to low income breastfeeding mothers.6-7 These results are less robust than the authors' earlier work which demonstrate that the BST increased breastfeeding rate from birth through the first 16 weeks postpartum.15-17

The significant difference in breastfeeding rates at 6 weeks postpartum may have related to intensity of treatment. The BST intervention was most intensive through the first weeks postpartum. During this period, mothers received frequent telephone calls and home visits. Anecdotally mothers shared information revealing that the complexity of their lives increased between four and six weeks postpartum. Just as mothers became more difficult to reach due to increased life's stressors, the intensity of the intervention decreased. The mothers may have had the desire to continue breastfeeding, but mothers told peer counselors that they had issues related to housing, returning to school or work, and lack of helper support. They often described settings that were not conducive or supportive to pumping and/or storing milk.

Healthy People 2010 included the goal of increasing breastfeeding rates so that 50% of all mothers would be breastfeeding at six months. Further, the goals specifically focus on the 50% target for low-income mothers.2 Even with an extensive intervention, it was difficult to meet the ambitious Healthy People 2010 goals. The significant increase at six weeks postpartum suggests that intensive early interventions can be effective, but is not sufficient to meet the Healthy People 2010 goals for low-income mothers. However, six weeks postpartum of breastfeeding especially for this vulnerable group is an important milestone; as literature suggests that every additional week of breastfeeding is associated with a 4% decrease in the likelihood of an illness that requires health care provider contact.24 Even two weeks of breastfeeding is associated with fewer infant respiratory problems and enteric problems by six weeks postpartum25 and less diarrhea, coughing, and wheezing in racial minority infants.26 The plethora of advantages of breastfeeding include improved infant health, improved bonding, and maternal benefits such as fewer diagnoses of breast cancer and ovarian cancer, and better social interactions.26-30

Based on extensive literature review, the BST comprised of a community nurse and peer counselor is unique. It shows potential for making a difference in breastfeeding rates, at least for the early weeks of an infant's life. This study adds to what is known about support and education in the form of community nurses and peer counselors both of which have been studied individually as a strategy to increase breastfeeding specifically for low-income mothers.17-18 Critical and unique elements of the BST were that the community nurse and peer counselor worked as a team. They were accessible to the mother and infant continuously (twenty-four hours, seven days a week) to assist mothers with problems during the first few weeks of the newborn's life. This team provided social support, an important issue for low-income mothers. Several research studies report that lack of support hinders the process of breastfeeding in a low-income minority sample.31-35 In addition to not having support for breastfeeding, the presence of negative support from family, peers, or professionals also hinders establishment and maintenance of successful breastfeeding in low-income mothers.32 The BST may have buffered the low support reported by mothers.

This study had several limitations. Generalization is limited to English-speaking women from two urban hospitals in Baltimore, Maryland. In spite of creative approaches to tracking, mothers were difficult to follow. The most difficult to follow were identified as not breastfeeding (as discussed in the methods section). It is possible that our conservative approach to assigning breastfeeding status may have underestimated successful breastfeeding. Due to the heavy involvement and multiple contacts of the BST team with the mother, the authors chose to have the data collection performed by the BST team who were not blinded to group assignment. This may have biased the results. Intervention effects were not maintained beyond the initial period of an intense intervention and this represents an important lesson for future program development. Finally, our sample size calculation was based on a difference at 12 weeks postpartum, so may not have had an adequate sample to show a difference beyond that time period.

In summary, mothers exposed to the BST demonstrated a significant increase in breastfeeding rates through the first six weeks postpartum. This was a time during which the intervention was very intensive and included home visiting and frequent telephone contact. These findings demonstrate the effort it takes to effectively promote breastfeeding in low-income mother's lives. To increase breastfeeding, health care resources should be focused on promotion of early breastfeeding support for low-income mothers. As mothers' lives get more complex after the early postpartum period, creative strategies for ways to sustain breastfeeding, possibly such as ambulatory clinic support, have yet to be determined.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant (1RO1NR007675) from the National Institute of Health – National Institute of Nursing Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There was no conflict of interest by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Linda C. Pugh, York College of Pennsylvania 441 Country Club Road York, PA 17403.

Janet R. Serwint, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine Baltimore, Maryland.

Kevin D. Frick, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health Department of Health and Policy Management Baltimore, Maryland.

Joy P. Nanda, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health Department of Population, Family, and Reproductive Health Sciences Baltimore, Maryland.

Phyllis W. Sharps, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing Baltimore, Maryland.

Diane L. Spatz, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Renee A. Milligan, George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics Work Group on Breastfeeding Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;100:1035–1039. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy People 2010. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: Nov, 2000. Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. [Google Scholar]

- 3.USDHHS . HHS Blueprint for Action on Breastfeeding. U. S. Department of Health and Human Resources, Office on Women's Health; Washington, D.C.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Breastfeeding. 2009 April 20; Retrieved April 23, 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/NIS_data/index.htm.

- 6.Schafer E, Vogel MK, Viegas S, Hausafus C. Volunteer peer counselors increase breastfeeding duration among rural low income women. Birth. 1998;25(2):101–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1998.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson BH, Haider SJ, Vangjel L, Bolton TA, Gold JG. A quasi experimental evaluation of a breastfeeding support program for low income women in Michigan. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2008 December; doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0430-5. published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shealy KR, Li R, Benton-Davis S, Grummer-Strawn LM. The CDC Guide to Breastfeeding Interventions. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevetion; Atlanta: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Oliveira MI, Camacho LAB, Tedstone AE. Extending breastfeeding duration through primary care: A systematic review of prenatal and postnatal interventions. Journal of Human Lactation. 2001;17(4):326–343. doi: 10.1177/089033440101700407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill SL. The little things: Perceptions of breastfeeding support. JOGNN. 2001;30:401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corbett KS. Explaining infant feeding style of low-income black women. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2000;15(2):73–81. doi: 10.1053/jn.2000.5445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kearney MH, York R, Deatrick JA. Effects of home visits to vulnerable young families. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2000;32(4):369–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pugh LC, Milligan RA. Nursing intervention to increase the duration of breastfeeding. Applied Nursing Research. 1998;11:190–194. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(98)80318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenz ER, Pugh LC, Milligan RA, Gift A, Suppe F. The middle-range theory of unpleasant symptoms: An update. Advances in Nursing Science. 1997;19:14–27. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199703000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pugh LC, Milligan RA, Brown L. The breastfeeding support team for low-income, predominantly-minority women: a pilot intervention study. Health Care for Women International. 2001;22:501–515. doi: 10.1080/073993301317094317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langston ME, Pugh LC, Franklin T, Brown LP, Milligan RA. The breastfeeding support team: A community nurse and a breastfeeding peer counselor providing care to low-income women. Journal of Perinatal Education. 1998;7(3):40–46. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pugh LC, Milligan RA, Frick KD, Spatz D, Bronner Y. Breastfeeding duration, costs, and benefits of a support program for low-income breastfeeding women. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care. 2002;29:95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bronner Y, Barber T, Vogelhut J, Resnick AK. Breastfeeding peer counseling: Results from a national survey. Journal of Human Lactation. 2001;17:119–125. doi: 10.1177/089033440101700205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossman B. Breastfeeding peer counselors in the United States: Helping to build a culture of tradition of breastfeeding. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 2007;52:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baby Friendly USA Baby Friendly hospital and birth centers. 2009 March; Retrieved April 10, 2009 from http://www.babyfriendlyusa.org/eng/03.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curry MA, Campbell RA, Christian M. Validity and reliability testing of the prenatal psychosocial profile. Research in Nursing and Health. 1994;17:127–135. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770170208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spielberger CD. Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologistists, Inc.; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettigrew MM, Khodaee M, Gillespie B, Schwartz K, Bobo JK, Foxman B. Duration of breatfeeding, daycare and physician visits among infants 6 months and younger. Annals of Epidemiologl. 2003;13:431–435. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(02)00463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stepans MB, Wilhelm SL, Hertzog M, Rodehorst TK, Blaney S, Clemens B, Polak JJ, Newburg DS. Early consumption of human milk oligosaccharides is inversely related to subsequent risk of respiratory and enteric disease in infants. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2006;1(4):207–215. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2006.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raisler J Alexander C, O'Campo P. Breastfeeding and infant illness: A dose response relationship? American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(1):25–29. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer Breast cancer and breastfeeding: Collaborative reanalysis from epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. Lancet. 2002;360:187–195. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09454-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ip S, Raman G, Chew P, Magula N, DeVine D, Trikalinos T, Lau J. Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Outcomes in Developed Countries. Rockville, MD: 2007. (AHRQ Publication No. 07-E007). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Locklin MP. Telling the world: Low income women and their breastfeeding experiences. Journal of Human Lactation. 1995;11(4):285–291. doi: 10.1177/089033449501100415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labbok MH. Health sequelae of breastfeeding for the mother. Clinics In Perinatology. 1999;26(2):491–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McIntyre E, Hiller JE, Turnbull D. Attitudes towards infant feeding among adults in a low socioeconomic community: what social support is there for breastfeeding? Breastfeeding Review. 2000;9(1):13–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barton S. Infant feeding practices of low-income rural mothers. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2001;26(2):93–97. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corbett KS. Explaining infant feeding style of low-income black women. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2000;15(2):73–81. doi: 10.1053/jn.2000.5445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sikorski J, Renfrew MJ. Support for breastfeeding mothers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001141. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gutman N, Zimmerman DR. Low-income mothers' views on breastfeeding. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;50:1457–1473. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00387-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]