Abstract

Hepatitis C Treatment Experiences and Decision-Making Among Patients Living with HIV Infection Abstract Hepatitis C infection is a major problem for approximately 250,000 HIV-infected persons in the United States. Although HIV infection is well controlled in most of this population, they suffer liver-associated morbidity and mortality. Conversely, HCV treatment uptake remains quite low (15–30%). Therefore, the purpose of this qualitative study was to explore HCV treatment experiences and decision-making in adults with HIV infection. The study sample included 39 co-infected adults, 16 in the HCV-treated cohort (who were interviewed up to 3 times) and 23 in the HCV-non-treatment cohort. Analysis of interviews identified 2 treatment barriers (fears and vicarious experiences) and 4 facilitating factors (experience with illness management, patient-provider relationships, gaining sober time, and facing treatment head on). Analysis of these data also revealed a preliminary model to guide intervention development and theoretical perspectives. Ultimately, research is urgently needed to test interventions that improve HCV evaluation and treatment uptake among HIV-infected patients.

Keywords: decision-making, Hepatitis C, HIV

Treatment of HIV-infected persons with combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the past decade has altered the spectrum of liver disease. Liver abnormalities in this population are now less commonly due to opportunistic infections and neoplasm; the most prevalent liver-associated problem is hepatitis C virus (HCV; Bica et al., 2001; Sulkowski, Moore, Mehta, & Chaisson, 2002). The proportion of liver-related deaths among HIV-infected adults in the United States has increased 3- to 4-fold (Selik, Byers, & Dworkin, 2002). Even more striking, more than half (54.6%) of those HIV-infected patients who died of liver-related causes appeared to have well-controlled HIV infection (e.g., undetectable HIV RNA and CD4 cell count > 200/mm3; Weber et al., 2006).

The prevalence of HIV/HCV coinfection is high. An estimated 25–40% of HIV-infected patients are also infected with HCV, and in some practices the prevalence is as high as 75–90% (Dieterich, 2004; Sherman, Rouster, Chung, & Rajicic, 2002; Thomas, 2002). Recent estimates suggest that approximately 250,000 persons are co-infected with HIV and HCV in the United States (Thomas, 2008). At least 6 distinct genotypes (numbered 1–6) and more than 30 subtypes of HCV are known (Alter, 1997). The most common genotype present in the United States, genotype 1, is also the most resistant to treatment.

HIV and HCV infections interact biologically. HIV infection is associated with higher HCV RNA levels and a more rapid progression of HCV-related liver disease (Zylberger & Pol, 1996). In a paired biopsy study, HIV infection was found to accelerate the rate of fibrosis progression by 1.4-fold and the development of advanced fibrosis 3-fold (Mohsen et al., 2003). Severity of liver fibrosis is also related to HIV infection-induced CD4 cell depletion (Puoti et al., 2001). A low CD4 cell count was independently associated with advanced HCV disease and correlated with a higher histological index (Mohsen et al., 2003). Therefore, in patients infected only with HCV, the time between infection and development of fibrosis averages 20 years, whereas in patients co-infected with HIV/HCV, liver disease may develop in 5–10 years (Benhamou et al., 1999). This factor alone illustrates the need to increase the number of HIV/HCV-co-infected patients who receive HCV treatment. HCV infection also influences the course and management of HIV disease, particularly by increasing the risk of ART-induced hepatotoxicity (Sulkowski & Benhamou, 2007).

Treatment of HCV infection has improved significantly over the past several years. The goal of HCV treatment is to achieve a sustained virologic response (SVR), which is defined as the absence of serum hepatitis C RNA for 24 weeks after treatment completion. The current standard of care for HCV treatment (ribavirin and peginterferon alfa) is based on the results of three major studies of combination therapy for hepatitis C in HIV/HCV co-infected individuals (AIDS Pegasys Ribavirin International co-infection Trial [APRICOT], AIDS Clinical Trials Group [ACTG] A5071, and RIBAVIC; Highleyman, 2004). The APRICOT included 868 patients with stable HIV disease, elevated ALT levels, compensated liver disease, and CD4 cell counts ≤ 100 cells/mL. The overall rate of SVR was significantly higher for those receiving peg interferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin (40%). Among genotype 1 patients, the SVR was 29%, and among those with genotype 2 or 3, the SVR was 62% (Torriani et al., 2004). The only two predictors of a sustained virologic response in this cohort was an HCV genotype other than 1 and a baseline HCV RNA level of ≤ 800,000 IU/mL. The ACTG A5071 study (N = 133) demonstrated a lower overall response rate (SVR = 27%; Chung et al., 2004) than in the APRICOT study, but results were similar to the French multicenter study (RIBAVIC; N = 412; Carrat et al., 2004), which demonstrated an overall SVR of 26%. In general, these studies demonstrated that the SVR rates vary between 14% and 29% in HIV/HCV co-infected patients with genotype 1 HCV.

These studies made significant contributions to understanding HCV treatment in HIV/HCV-co-infected patients. Results consistently demonstrated that patients with an early virologic response to treatment were more likely to achieve SVR. In addition, results indicated that some histologic improvement may occur among those patients who do not achieve an SVR, suggesting that aggressive efforts to treat HIV/HCV-co-infected patients may provide some benefit even when an SVR is not achieved. However, only a minority of HIV/HCV-co-infected patients (approximately 15%) have been treated for HCV (Alberti et al., 2005).

The problem of HCV treatment within the context of HIV infection is very complex in the presence of HIV comorbidity (mental and physical), substance abuse, and co-occurring toxicity associated with HCV- and HIV-treatment regimens (Lo Re, Kostman, & Amorosa, 2008). Additionally, limited data have suggested that this population infrequently accepts and completes treatment. Therefore, we need to know more about the experiences of HCV treatment decision-making from the perspective of HIV/HCV-co-infected patients.

Without HCV treatment, increasing numbers of HIV-infected patients will die either from end-stage liver disease or from HIV-related complications because of the inability to use antiretroviral agents due to their hepatotoxicity. Despite major advances in understanding HCV treatment in this population within the past several years, only a small proportion of co-infected patients receive HCV treatment. Moreover, few studies have explored how co-infected patients make decisions related to HCV treatment. A major gap in knowledge is how best to help patients make decisions about beginning or deferring HCV treatment. Indeed, several prominent HIV/HCV clinical scientists have called for the development of innovative strategies to increase the number of HIV/HCV-co-infected patients potentially eligible for HCV treatment (Mehta et al., 2005; Strathdee & Patterson, 2006; Sulkowski & Thomas, 2003, 2005; Sulkowski et al., 2002). Therefore, the purpose of this qualitative study was to develop a clear understanding of HIV-infected patients’ decision-making experiences with HCV treatment. The specific aims of this study were to describe the experiences of HIV-infected patients as they made decisions to begin or defer HCV treatment and to develop a model to guide the development of future interventions to support HCV-treatment efforts in co-infected patients.

Methods

Sample

Patients with HIV and HCV infection were recruited from three HIV specialty clinics in central and western Massachusetts. Potential study participants were identified by clinic staff and by flyers posted in the clinics. Co-infected patients expressing interest in the study were given the option to call the research team directly (password-protected phone) or to be contacted by the research staff (after the patient provided written consent for release of name and telephone number). Purposive sampling (Patton, 1990) was used to achieve maximum variation in gender and HCV-treatment status (treated and non-treated cohorts). This sampling method was changed during data analysis; as themes emerged, we moved to theoretical sampling (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) where sampling was based on evolving ideas about treatment refusal and deferral rather than treatment completion. For example, after the first 12 interviews, data analysis indicated a need to actively recruit more participants who chose not to be treated for HCV.

Patients were included in the study if they met the following criteria: age 18 years or older, HIV/HCV-co-infected (detectable HCV viral load and positive HIV antibody test or HIV viral load documented in the medical record), and able to speak English. Of the 40 patients initially recruited, 1 female participant was excluded from analysis because she was found to be HCV mono-infected. The final sample included 39 participants (16 HCV treated, 23 HCV non-treated).

Procedures

All procedures related to this study were reviewed and approved by an institutional review board. All study participants were informed about the purpose, methods, and their rights as study participants before beginning interviews. Written informed consent was then obtained and study participants received a $25 stipend after completing each interview. Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted with 39 different study participants between May 2003 and January 2005. Interviews were conducted by the first author and a research assistant (RA). The RA participated in two initial training meetings. The first meeting reviewed the purpose and study-related procedures, data collection forms as well as the interview questions. The second meeting focused on interviewing techniques, recording equipment, sequence of data collection and population-specific issues (e.g., literacy, substance use). After the RA completed the first interview, the first author reviewed the audio recording and transcript and discussed with the RA ways to enhance interviewing procedures. The first author reviewed every interview (audio recording and transcript) completed by the RA and any concerns were discussed with the RA at regular intervals.

Data were first collected on demographic, clinical, mental health, and symptom information using a structured questionnaire. Symptom experience data have been reported previously (Bova, Jaffarian, Himlan, Mangini, & Ogawa, 2008). Data were next collected on HCV treatment and decision-making experiences using a semi-structured interview guide to conduct qualitative interviews. All interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist. The interviews lasted 30 to 60 minutes and were conducted in private offices by two interviewers. Participants in the HCV-treated cohort were interviewed up to 3 times (before treatment, 8–12 weeks into treatment, and at treatment completion). The same interviewer conducted all follow-up interviews. Participants who chose not to be treated were interviewed only once. This process resulted in 61 transcribed interviews (507 single-spaced pages of text).

Data Analysis

Qualitative descriptive methods (Sandelowski, 2000; Sullivan-Bolyai, Bova, & Harper, 2005) and qualitative content analysis were used to analyze within and across the interview data. The first author reviewed individual participant data line by line, summarizing thoughts and ideas. Descriptive codes (Miles & Huberman, 1994) were developed by categorizing text into themes and categories. Case comparisons were also made to identify variations in themes and categories. Memoing (a written form of thinking about the data) and diagramming (graphic representation of relationships between themes and concepts) were performed throughout data collection and analysis (Miles & Huberman, 1994). As coding proceeded, a codebook was developed to increase intra-analyst reliability. Data reflecting the HCV-treatment experience at each time point (before treatment, 8–12 weeks into treatment, and at treatment completion) were isolated, coded, and categorized. As a validity check, codes and categories were discussed and verified with the RA who was familiar with these data. Next, cases were compared to see how the categories varied according to HCV-treatment decisions. From these case comparisons, preliminary hypotheses were developed and tested with respect to how the categories were linked to participants’ HCV-treatment experiences. Based on these hypotheses, the sampling scheme was changed to capture more information about the experiences of those who chose not to be treated. Particular attention was paid to how variations in magnitude and types of experiences affected HCV-treatment outcomes and how subjects’ experiences helped or hindered their movement through treatment. Member checks (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) were performed by asking 2 study participants (1 who began HCV treatment and 1 who decided not to be treated) to review the major themes and preliminary model. Their feedback suggested that the themes and model presented below adequately reflected their experiences with HCV treatment.

Results

The study sample included 39 HIV/HCV-co-infected adults, 54% male, 51% minority, 36% without a high school diploma or Graduate Education Equivalent (GED), 87% with a history of mental illness, 95% with a history of substance abuse, and 59% with HCV subtype 1. The mean age of the sample was 45.1 years (range = 34–56 years) and 36% had AIDS. The demographic, clinical, mental health, and substance use characteristics of this sample are summarized by HCV-treatment status at baseline (16 treated vs. 23 non-treated) in Table 1. Participants in the non-treated cohort chose to defer or refuse HCV treatment at the baseline interview. Table 2 summarizes the age, length of time with HIV, and CD4 cell count by treatment status. Table 3 outlines the number of interviews completed at each time point. In the treated cohort, which was interviewed over the course of treatment, the attrition rate was 31% (5 participants did not show for either the 8–12 week or treatment completion interviews). Of the 16 participants in the treatment cohort, 11 (69%) were confirmed by electronic medical record review to have completed 48 weeks of treatment (but only 9 participated in a treatment completion interview).

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, Mental Health, and Substance Use Characteristics (N = 39)

| HCV-Treated Cohort (n = 16) | Non-Treated Cohort (n = 23) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n (% in cohort) | n (% in cohort) | n (%) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 13 (81.2) | 8 (34.8) | 21 (53.8) |

| Female | 3 (18.8) | 15 (65.2) | 18 (46.2) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 9 (56.2) | 10 (43.5) | 19 (48.7) |

| Hispanic | 6 (37.5) | 8 (34.8) | 15 (38.5) |

| African American | 1 (6.2) | 5 (21.7) | 5 (12.8) |

| Education: HS/GED | |||

| Yes | 11 (68.8) | 14 (60.9) | 25 (64.1) |

| No | 5 (31.2) | 9 (39.1) | 14 (35.9) |

| Partner status | |||

| Married/partnered | 5 (31.2) | 3 (13.0) | 8 (20.5) |

| Single | 11 (68.8) | 20 (87.0) | 33 (79.5) |

| HIV illness stagea | |||

| Asymptomatic | 6 (37.5) | 11 (47.9) | 17 (43.6) |

| Symptomatic | 5 (31.2) | 3 (13.0) | 8 (20.5) |

| AIDS | 5 (31.2) | 9 (39.1) | 14 (35.9) |

| Undetectable HIV viral load | |||

| Yes | 7 (43.8) | 4 (17.4) | 11 (33.3) |

| No | 8 (50.0) | 14 (60.9) | 22 (56.4) |

| Unknown | 1 (6.2) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (15.4) |

| On ART | |||

| Yes | 12 (75.0) | 19 (81.6) | 31 (79.5) |

| No | 4 (25.0) | 4 (17.4) | 8 (20.5) |

| HCV subtype | |||

| 1 | 12 (75.0) | 11 (47.8) | 23 (59.0) |

| 2 or 3 | 3 (18.8) | 3 (13.0) | 6 (15.4) |

| 4 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (5.1) |

| Unknown | 1 (6.2) | 7 (30.5) | 8 (20.5) |

| Liver biopsy done | |||

| Yes | 16 (100.0) | 6 (26.1) | 22 (56.4) |

| No | 0 (0.0) | 17 (73.9) | 17 (43.6) |

| Mental health problem | |||

| Yes | 11 (68.8) | 23 (100.0) | 34 (87.2) |

| No | 5 (31.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (12.8) |

| Depression diagnosis | |||

| Yes | 9 (56.2) | 17 (73.9) | 26 (67.7) |

| No | 7 (43.8) | 6 (26.1) | 13 (33.3) |

| Hospitalized to treat mental illness | |||

| Yes | 5 (31.2) | 5 (21.7) | 10 (25.6) |

| No | 11 (68.8) | 18 (78.3) | 29 (74.4) |

| Suicide attempted | |||

| Yes | 5 (31.2) | 8 (34.8) | 13 (33.3) |

| No | 11 (68.8) | 15 (65.2) | 26 (67.7) |

| Taking mental health medications | |||

| Yes | 9 (56.2) | 16 (69.6) | 25 (64.1) |

| No | 7 (43.8) | 7 (30.4) | 14 (35.9) |

| Substance abuse problem | |||

| Yes | 15 (93.8) | 22 (95.7) | 37 (94.9) |

| No | 1 (6.2) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (5.1) |

| Active substance abuse (≤ 1 month) | |||

| Yes | 1 (6.2) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (15.4) |

| No | 15 (93.8) | 18 (78.3) | 33 (84.6) |

| Problematic substances (multiple responses possible) | |||

| Heroin | 13 (81.2) | 20 (87.0) | 33 (84.6) |

| Cocaine | 13 (81.2) | 17 (73.9) | 30 (76.9) |

| Alcohol | 13 (81.2) | 16 (69.6) | 29 (75.0) |

| Crack | 5 (31.2) | 12 (52.2) | 17 (43.6) |

Note. HS = high school; GED = Graduate Education Equivalent; ART = antiretroviral therapy

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1992). The 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 41(RR-17).

Table 2.

Sample Age, Time with HIV, and CD4 cell count (N =39)

| HCV-Treated Cohort | Non-Treated Cohort | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Age (years) | 46.2 (4.8) | 44.2 (5.1) | 45.1 (5.0) |

| Time with HIV (years) | 13.6 (6.4) | 13.5 (4.1) | 13.6 (5.1) |

| CD4 cell count (at baseline) | 466 (258) | 418 (230) | 439 (240) |

Table 3.

Interviews Completed at Each Time Point (N =39)

| Interviews (n) |

Total interviews (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV Treatment | Baseline | 8–12 weeks of treatment | Treatment completion | |

| Treated | 16 | 13 | 9 | 38 |

| Non-Treated | 23 | -- | -- | 23 |

| 61 | ||||

The major findings indicated that the HCV evaluation and treatment process went smoothly for most participants in the HCV-treated cohort. Successful treatment was facilitated at all three clinics by significant monitoring (for depression, substance abuse relapse, and side effects) and support. Depression and suicidality were not a major problem for this group of subjects. All who chose treatment were already on or were started on antidepressants before treatment began. Among the 16 treated participants, only 1 relapsed to substance use during treatment (6.3% relapse rate).

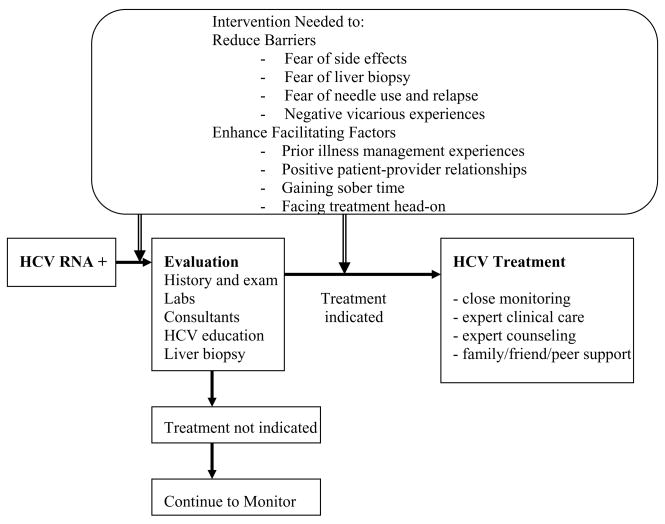

Analysis of qualitative data from the entire sample resulted in six major themes. These themes were further categorized into treatment barriers or treatment facilitating factors. The two treatment barriers were (a) treatment fears (associated with side effects, liver biopsy, substance abuse relapse, and needle use) and (b) vicarious experiences. The four facilitating factors were (a) experience with illness management, (b) patient-provider relationships, (c) gaining sober time, and (d) facing treatment head on. Each theme is described below.

Treatment Barriers

Participants in both the treated and non-treated cohorts described treatment barriers. Barriers included concerns that caused participants to delay, defer, or refuse treatment (either presently or in the past).

Fears

The major concern discussed by most participants (n = 32, 82%) was fear of HCV treatment side effects. One participant in the non-treated cohort said, “There are too many risks: heart attack, loss of hair, too many things. They [doctors and nurses] scare me when they told me these things could happen.” Another participant discussed his fear of side effects in relationship to his worry about delaying HCV treatment:

I’m afraid to put my foot through the door because the fears that you are going to get sick from those side effects … then if I look back 6 months, 6 years, saying all that time I was half stepping, wasting time, and I could have gone through the door….. I just stay standing in that same place because of that fear that people never talk about.

Fear of the liver biopsy was specifically mentioned by 14 (36%) participants. One participant stated,

I think the only thing between me and the medication is that biopsy, and just thinking about it scares me, and sometimes I can’t sleep when I’m thinking about it…if they bypasses that whole procedure or puts me to sleep maybe then…

A participant who began HCV treatment described his negative experience with the liver biopsy. He mentioned that he would never have another biopsy. He stated,

It was torture. They showed me what they were going to use – that was a biggest mistake – don’t ever show anyone what you’re going to stick in ‘em – that made me more afraid – felt like I got kicked in the chest by a horse.

It is also important to note that 7 (18%) participants had no major problems with the liver biopsy. For example, one woman said, “Everyone kept telling me how bad it was going to be. I was real nervous. But it only took a short time and it was over… it was no big deal.” Another participant stated, “It only hurt for a little while after … once I had something to eat it was better.”

Many participants were aware of the potential risk of HCV treatment to their sobriety. One male participant stated, “I work hard on my sobriety … don’t want nothing causing me to fall … heard those effects can make you feel like you’re kicking … don’t want that, now do I?” Seven participants expressed concerns about the need to use needles to administer the interferon component of the HCV-treatment regimen. Some were concerned about the “feeling of self-injecting,” while others were more worried about having needles around the house. One female participant discussed her fears about needle use and making plans to come to the clinic for all her injections. She stated,

…last time I did heroin it was like 10 months ago, and I decided to become sober – then I built up a fear of needles. I’ve gotten to the point where I don’t even want to touch a needle – it makes me sick to my stomach – so I’m having the nurse give me the shots.

Another participant stated that she “wouldn’t want to keep the needles in the house, because it would be a constant reminder.” In contrast, one male participant stated that his “sobriety was solid” and that “needles don’t bother me – spiritually, I’m connected” so he chose to administer his own medication and did very well throughout treatment. Another participant indicated, “It took me about 2 months of coming in for the needle when I realized I could handle the needles now.”

Vicarious experiences

Many participants (n = 11) discussed seeing others going through HCV treatment or hearing the stories of others who had been treated. They said they formed their opinions about beginning treatment based on these vicarious experiences. One participant expressed her fear of HCV treatment even though her partner had a successful outcome. “I’m scared of that stuff. I watched ____ [partner]; he went through hell, some days no appetite, he never could sleep, insomnia was a big thing, those pills are bad, but it made him undetectable.” One female participant described her vicarious experience as follows:

I heard from this friend that the side effects are awful – nausea, headaches, just sick, and feel lousy all of the time – he always looked terrible and kept saying how sick he was. But there were a few others – some were sick and some didn’t get bothered. So I am hoping I am one of the lucky ones.

In comparison, another participant stated, “I have talked to 7 friends who got treated and none of them had major problems… they just dealt with the bad days.” This participant decided to defer treatment because she was not ready to deal with the bad days.

Facilitating factors

Four themes were identified that facilitated movement toward HCV treatment. These themes were identified by participants who had chosen to begin HCV treatment and included experience with illness management, patient-provider relationships, gaining sober time, and facing treatment head on.

Experience with illness management

Study participants (n = 7) discussed their experiences managing HIV and many other illnesses (including cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and asthma). They discussed using strategies developed over time to manage these chronic conditions as a way to manage HCV and subsequent treatment. Several participants had type 2 diabetes and had experience with insulin injections. Another participant stated, “This [HCV treatment] is similar to starting HIV medications; I know the experience, I get side effects in the beginning, and then get general discomforts, but I don’t dwell on it.” Another participant described his experience with illness management as follows:

I used to give my grandmother her insulin – so I know certain areas, and living all these years with HIV, I understand side effects. I went on AZT in the beginning – on a trial – that was rough stuff – you get side effects in the beginning and then it gets better. I just don’t dwell on it and push myself through it.

Two other participants had experienced cancer treatment. They saw HCV treatment as similar to chemotherapy because “there is an end to it and you know one way or the other if it worked.”

Patient-provider relationships

Participants also spoke about the importance of patient-provider relationships as a means to help them get through HCV treatment. They discussed the positive aspects of their relationships with various health care providers and how these relationships were integral to evaluation and treatment acceptance. For example, one participant stated, “They [doctor and nurse practitioner] explained everything, I was very comforted. I felt taken care of and would give them an A.” Two participants discussed the effect of negative relationships, and one participant stated that he “stopped treatment” due to this negative relationship.

Gaining sober time

An important concern mentioned by 6 study participants was gaining sober time. In addition, many participants discussed the role of substance use in making their treatment decisions. Participants agreed that a certain amount of sober time was needed before starting HCV treatment; the sober time mentioned ranged from 6 months to 2 years. One participant stated, “… need to deal with addictions first.” Many participants provided in-depth accounts of how substance use entered and influenced their lives and how the struggle to get and stay sober influenced their decisions to move forward with treatment. These data are described elsewhere (Ogawa & Bova, 2009).

Facing treatment head on

The last theme involved facing treatment head on. Participants described how they reframed all the negative issues associated with HCV treatment and established a “mind-set” that helped them move forward. One male participant, who had struggled with the decision to begin HCV treatment, articulated this theme best. Using the metaphor “going in like a soldier,” he described how he felt just before treatment: “I heard horror stories about the biopsy, the side effects, the effect on me emotionally, but eventually I go – it’s my turn – I’m going in like a soldier.” Other participants described the way they reframed negative messages, rallied support, and set up safeguards to achieve success. One participant stated, “I’ve prepared my mind to go through it … I try not to focus on the bad and think of the positives, set everything up, see my counselor, follow my nurse’s advice, know where to call, not have needles around.”

Model Development

From these data, we developed a preliminary model to outline factors that influenced the HCV evaluation and treatment process among HIV-infected adults (Figure 1). Most of these factors are amenable to behavioral intervention. However, it is unclear from our data which interventions would be best placed before or after HCV evaluation. Therefore, we have placed them both before and after evaluation in the figure.

Figure 1.

Preliminary Model to Guide Interventions to Improve HCV Evaluation and Treatment Uptake

Discussion

HIV-infected patients have many problems associated with HCV treatment. For example, current treatment has a high side-effect burden, low response rates, threatens sobriety, can accentuate existing mental health problems, and requires intensive monitoring and follow-up. One may indeed ask why patients should be put through such a process. HIV-infected patients are dying from liver-related complications while having an undetectable HIV viral load. This knowledge creates a tremendous need to reduce the risk imposed by liver disease in HIV-infected patients (Thomas, 2008). Results of this study highlight three important issues. First, patients who accept HCV treatment differ in some way from those who refuse or defer treatment. Patients who begin treatment do reasonably well when significant supports are put in place. They tend to use strategies that help them prepare and begin treatment based on prior illness experiences. Our data are consistent with other reports that pre-existing psychiatric illness was not a major barrier to HCV treatment (Mehta et al., 2006). Effective pre-evaluation and support strategies were in place that helped facilitate HCV treatment.

On the other hand, those who do not begin treatment tend to be fearful and use other patients’ negative experiences as a reason to hold off on HCV treatment. Fear associated with treatment has been reported in other studies examining HCV treatment barriers among mono-infected and HIV-co-infected patients (Khokhar & Lewis, 2006; Mehta et al., 2008). For example, generalized fear was identified as a major theme and barrier to HCV testing and treatment among an HCV mono-infected cohort (Grow & Christopher, 2008).

Second, results of this study shed light on possible theoretical orientations that might be useful for developing HCV-treatment interventions. For example, the finding that participants used vicarious experiences to make decisions about moving forward with HCV treatment implies that Bandura’s social learning theory (Bandura, 1986) might be useful for intervention development. Bandura (1986) indicated that different types of information could influence a person’s self-efficacy to perform certain behaviors (e.g., deciding to be treated for HCV infection). Vicarious experience is a form of learning that occurs when patients watch those similar to themselves take part in a certain behavior or activity. If HIV-infected patients have the opportunity to watch others master HCV treatment, they may be more likely to decide to move forward with HCV treatment. Likewise, an appraisal-centered theoretical orientation may be useful for intervention development. For example, the cognitive appraisal model (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) focuses on the appraisal or meaning of an event (i.e., HCV infection) to one’s personal well-being. An intervention that helps patients reframe the negative meaning associated with HCV treatment may be useful for helping them make HCV treatment decisions. Other models that focus on the evaluation of perceived risks and benefits (e.g., Health Belief Model, Self Regulation) may also be useful for guiding HCV intervention development.

Third, our results suggest a gender disparity in HCV treatment uptake. Although our sample is too small for formal quantitative analyses, men appeared to far outnumber women (by 4 to 1) in the treated cohort. This finding is consistent with female, HCV mono-infected patients declining therapy significantly more often than their male counterparts (Khokhar & Lewis, 2006). Similarly, men were found to be twice as likely to be treated for HCV as women (McNally, Temple-Smith, Sievert, & Pitts, 2006). The reasons why women decline HCV treatment more often than men is unclear and requires further investigation.

Finally, our preliminary model was developed with the assumption that an intensive intervention would be needed to move HIV/HCV-co-infected patients toward informed decision-making about HCV treatment. On the other hand, a decision aid alone has been suggested for development and use in helping HCV mono-infected patients make HCV treatment decisions (Schackman, Teixeira, Weitzman, Mushlin, & Jacobson, 2008). However, it is clear that the treatment decision in patients with HIV coinfection is more complex and may require an intervention that matches the complexity of the decision. For example, Rifai (2006) suggested that it would be unwise to expect patients to fully understand the complex nature of HCV infection and factors that go into making a treatment decision, especially when patients have comorbid mental and substance abuse disorders. Rifai suggested that for patients to make a truly informed treatment decision, primary care providers, specialty care providers (e.g., hepatology, psychiatry), patients, and their families need to engage in a “dynamic dialogue” (Rifai, 2006, p. 541). We concur and believe that interventions with the best chance of success in helping co-infected patients make this complicated treatment decision will be theoretically based, intense enough, and include interprofessional involvement.

Limitations

The descriptive nature of the study and sample size limits the generalizabilty of the study findings. In addition, study attrition might have biased the treated cohort results in a more positive direction. Three participants did not return for the 8–12 week interview, and 7 participants did not return for the final treatment completion interview. Those who did not return might have had more negative experiences associated with HCV treatment. Finally, we did not collect data on the time since HCV diagnosis or length of time on ART. We made an attempt to collect liver biopsy reports; however these data were often difficult to retrieve and were incomplete or missing for many of the study participants. Therefore, we could not compare findings by length of time with HCV, length of time on ART, or liver disease severity.

Conclusion

HCV treatment decision-making among HIV-co-infected adults is complex. Results of this study have uncovered some important treatment barriers and facilitating factors that are amenable to behavioral intervention. In addition, several theoretical perspectives emerged from the qualitative findings and suggest that cognitive behavioral theories (e.g., social learning theory, cognitive appraisal model of stress and coping) might be useful to guide intervention development. Clearly, HCV treatment uptake remains low among HIV-infected patients. Future research is needed on how best to help patients make informed decisions about HCV treatment, as well as interventions that reduce HCV treatment barriers. The issue of gender disparity in treatment acceptance also needs further investigation. Finally, the advent of new HCV antiviral therapies increases the importance that research efforts focus on improving HCV evaluation and treatment rates to reduce liver-associated morbidity and mortality among the large cohort of HIV/HCV-co-infected patients.

Clinical Considerations

The following are important clinical considerations from these data:

Nursing interventions that reduce the fear associated with HCV treatment side effects, liver biopsy, needle use, and substance abuse relapse are needed.

Nursing interventions that help patients recognize the usefulness of prior illness management techniques as a way to manage HCV treatment challenges are needed.

Negative HCV treatment experiences of others may influence patient’s HCV treatment decision-making.

Positive patient/health care provider relationships are essential to improve HCV uptake among HIV-infected patients.

Helping patients gain more sober time through substance use treatment referrals and support is an important first step to increasing the number of co-infected patients who are ready to begin HCV treatment.

Assisting patients to reframe the negative meaning associated with HCV treatment may help patients face HCV treatment with a more optimistic attitude.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (R15 NR008341) and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NINR. The authors would also like to recognize the support of Community Research Initiative of New England, Nancy Madru, and the late Anne B. Morris, MD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Carol Bova, Associate Professor of Nursing and Medicine, University of Massachusetts Worcester, 55 Lake Avenue North Worcester, MA 01655 (508) 856-1848, carol.bova@umassmed.edu.

Lisa Fink Ogawa, Assistant Professor of Nursing, University of Massachusetts Worcester, 55 Lake Avenue North Worcester, MA 01655 (508) 856-3621, lisa.ogawa@umassmed.edu.

Susan Sullivan-Bolyai, Associate Professor of Nursing and Pediatrics, University of Massachusetts Worcester, 55 Lake Avenue North Worcester, MA 01655, (508) 856-4185, susan.sullivan-bolyai@umassmed.edu.

References

- Alberti A, Clumeck N, Collins S, Gerlich W, Lundgren J, Palu G, et al. Short statement of the first European Consensus Conference on the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and C in HIV co-infected patients. Journal of Hepatology. 2005;42:615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter MJ. Epidemiology of Hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1997;26(supplement):62S–65S. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Benhamou Y, Bochet M, DiMartino V, Charlotte F, Azria F, Coutellier A, et al. Liver fibrosis progression in human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfected patients. Hepatology. 1999;30:1054–1058. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bica I, McGovern B, Dhar R, Stone D, McGowan K, Scheib R, et al. Increasing mortality due to end-stage liver disease in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;32:492–497. doi: 10.1086/318501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bova C, Jaffarian C, Himlan P, Mangini L, Ogawa L. The symptom experience of HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected adults. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19:170–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrat F, Bani-Sadr F, Pol S, Rosenthal E, Lunel-Fabiani F, Benzekri A, et al. Pegylated interferon alfa-2b vs. standard interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin, for chronic hepatitis C in HIV-infected patients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:2839–2848. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung R, Andersen J, Volberding PA, Robbins GK, Liu T, Sherman KE, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin versus interferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C in HIV-coinfected persons. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:451–459. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich DT. Hepatitis C infection in HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2004;18:127–130. doi: 10.1089/108729104322994801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Grow JM, Christopher SA. Breaking the silence surrounding Hepatitis C by promoting self-efficacy: Hepatitis C public service announcements. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:1401–1412. doi: 10.1177/1049732308322603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highleyman L. Focus on hepatitis. Final APRICOT, ACTG A5071 results. International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Monthly. 2004;10(9):356–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhar OS, Lewis JH. Reasons why patients infected with chronic hepatitis C virus choose to defer treatment: Do they alter their decision with time? Digestive Disease Science. 2006;52:1168–1176. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9579-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Re V, Kostman JR, Amorosa VK. Management of complexities of HIV/Hepatitis C virus coinfection in the twenty-first century. Clinics in Liver Disease. 2008;12:587–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally S, Temple-Smith M, Sievert W, Pitts MK. Now, later or never? Challenges associated with hepatitis C treatment. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2006;30:422–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2006.tb00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SH, Thomas DL, Sulkowski M, Safaein M, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA. A framework for understanding factors that affect access and utilization of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection among HCV-mono-infected and HIV/HCV co-infected injection drug users. AIDS. 2005;19(suppl 3):S179–S189. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000192088.72055.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SH, Lucas GM, Mirel LB, Torbenson M, Higgins Y, Moore RD, et al. Limited effectiveness of antiviral treatment for hepatitis C in an urban HIV clinic. AIDS. 2006;20:2361–2369. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801086da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SH, Genberg BL, Astemborski J, Kavasery R, Kirk G, Vlahov D, et al. Limited uptake of hepatitis C treatment among injection drug users. Journal of Community Health. 2008;33:126–133. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9083-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mohsen AH, Easterbrook PJ, Taylor C, Portmann B, Kulasegarem R, Murad S, et al. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection on the progression of liver fibrosis in hepatitis C virus infected patients. Gut. 2003;52:1035–1040. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa LF, Bova C. Substance use experiences and hepatitis C treatment decision- making among HIV/HCV coinfected adults. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:915–933. doi: 10.1080/10826080802486897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Puoti M, Bonacini M, Spinetti A, Putzolu V, Govindariajan S, Zaltron S, et al. Liver fibrosis progression is related to CD4 cell depletion in patients coinfected with hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2001;183:134–137. doi: 10.1086/317644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifai MA. Ethical impasses in the care of patients with hepatitis C. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:540–541. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schackman BR, Teixeira PA, Weitzman G, Mushlin AI, Jacobson IM. Quality of life tradeoffs for hepatitis C treatment: Do patients and providers agree? Medical Decision-Making. 2008;28:233–242. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07311753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selik RM, Byers RH, Dworkin MS. Trends in diseases reported in U.S. death certificates that mentioned HIV infection, 1987–1999. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;29:378–387. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200204010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C virus prevalence among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: A cross-sectional analysis of the US adults AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;34:831–837. doi: 10.1086/339042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Patterson TL. Behavioral interventions for HIV-positive and HCV-positive drug users. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:115–130. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski M, Thomas DL. Hepatitis C in the HIV-infected person. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;128:197–207. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski M, Thomas DL. Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis C virus infection in injection drug users: Implications for treatment. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;40(Supplement 5):S263–S269. doi: 10.1086/427440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski M, Benhamou Y. Therapeutic issues in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 2007;14:371–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00816.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski MS, Moore RD, Mehta SH, Chaisson RE. Hepatitis C and progression of HIV disease. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Bolyai S, Bova C, Harper D. Developing and refining interventions in persons with health disparities: The use of qualitative description. Nursing Outlook. 2005;53:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DL. Hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Hepatology. 2002;36:S201–S209. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DL. The challenge of hepatitis C in the HIV-infected person. Annual Review of Medicine. 2008;59:473–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.081906.081110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torriani FJ, Rodriguez-Torres M, Rockstroh J, Lissen E, Gonzalez-Garcia J, Lazzarin A, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:438–450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber R, Sabin CA, Friis-Moller N, Reiss P, El-Sadr W, Kirk O, et al. Liver-related deaths in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:1632–1641. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylberger H, Pol S. Reciprocal interactions between human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1996;23:1117–1125. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.5.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]