Abstract

Photoreceptor degenerations can trigger morphological alterations in second-order neurons, however, the functional implications of such changes are not well known. We conducted a longitudinal study, using whole-cell patch-clamp, immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy to correlate physiological with anatomical changes in bipolar cells of the rd10 mouse - a model of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Rod bipolar cells (RBCs) showed progressive changes in mGluR6-induced currents with advancing rod photoreceptor degeneration. Significant changes in response amplitude and kinetics were observed as early as post-natal day 20, and by postnatal day 45, the response amplitudes were reduced by 91%, and then remained relatively stable until six months. These functional changes correlated with the loss of rod photoreceptors and mGluR6 receptor expression. Moreover, we showed that rod bipolar cells make transient ectopic connections with cones during progression of the disease. At P45, ON-cone bipolar cells retain mGluR6 responses for longer periods than the rod bipolar cells, but by about six months, these cells also strongly down-regulate mGluR6 expression. We propose that the relative longevity of mGluR6 responses in cone bipolar cells is due to the slower loss of the cones. In contrast, ionotropic glutamate receptor expression and function in OFF-cone bipolar cells remains normal at six months despite the loss of synaptic input from cones. Thus glutamate receptor expression is differentially regulated in bipolar cells, with the metabotropic receptors being absolutely dependent on synaptic input. These findings define the temporal window over which bipolar cells may be receptive to photoreceptor repair or replacement.

Keywords: retina, rod, cone, mGluR6, synaptic remodelling

Introduction

Photoreceptor degenerations such as Retinitis Pigmentosa and Age-Related Macular Degeneration are significant causes of visual morbidity. Strategies that show promise for sight restoration in such diseases include; cell transplantation (MacLaren et al., 2006), stem cell (MacLaren and Pearson, 2007) and gene therapy (Bainbridge et al., 2006) and prosthetic retinal implants (Weiland et al., 2005). However, the potential for such interventions to restore vision is contingent on the structural and functional integrity of the neurons downstream to the photoreceptors, particularly the second-order bipolar cells.

In darkness, photoreceptors release glutamate onto postsynaptic ON and OFF bipolar cells, which respond to glutamate with opposite polarities, due to different postsynaptic glutamate receptors. Rod bipolar cells (RBCs) and ON- cone bipolar cells (ON-CBCs) express the metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR6 (Nakajima et al., 1993), which closes a non-selective cation channel and hyperpolarizes the cell (Slaughter and Miller, 1985). In OFF-cone bipolar cells (OFF-CBCs), glutamate activates depolarizing, kainate/AMPA type ionotropic receptors. There is accumulating evidence that bipolar cells undergo morphological and histochemical alterations in response to photoreceptor degeneration. Immunohistochemical studies indicate that rod and cone bipolar cells undergo dendritic retraction and remodelling, and ON bipolar cells show changes in expression of the mGluR6 receptor (Strettoi et al., 2002; Marc et al., 2003; Strettoi et al., 2003; Barhoum et al., 2008). Little is known about the functional implications of these changes, since recording of single bipolar cell light responses, or assessment of massed bipolar cell function with the electroretinogram, is confounded by functional changes in the upstream photoreceptors. Knowledge of the timing of functional changes is critical to establish the period over which the bipolar cells may be receptive to therapeutic intervention.

The most widely characterised mouse model of retinal degeneration is the Pde6brd1 (rd1) mouse, an autosomal recessive model of human RP (Bowes et al., 1990; McLaughlin et al., 1993; McLaughlin et al., 1995). Degeneration occurs rapidly, with onset of rod loss at P8 and near complete loss of rods by P21 (Carter-Dawson et al., 1978). A major limitation of this model is that rod photoreceptor degeneration begins before normal development is complete (Blanks et al., 1974). Consequently, the bipolar cell dysfunction that has been reported in the rd1 mouse may be secondary to arrested retinal development. The more recently identified Pde6brd10 (rd10) mouse, which carries a missense mutation in the same gene, has a later onset and slower rate of photoreceptor degeneration than the rd1 mouse (Chang et al., 2007). These features make it a more suitable model to study bipolar cell function, since normal retinal development appears to be complete prior to the onset of the disease-related changes. Moreover, the slower degenerative time-course makes the rd10 a more appropriate model of human RP, and presents a broader window of opportunity to test therapies for photoreceptor rescue.

In this study, we have evaluated the localization and function of glutamate receptors on RBCs as well as ON- and OFF-CBCs during advancing stages of photoreceptor degeneration in the rd10 retina.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Tissue Preparation

Homozygous C57BL/6 and rd10 (also known as Pde6brd10, Jackson Laboratories) mice aged P14 to ~6 months were used in this study. Animals had access to standard chow ad libitum and were maintained on a 12 hr light/12 hr dark cycle. The maximum light intensity in the cages was measured at ~80 lux. All animal procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. For all experiments, animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (0.1 ml, 100 mg/ml) and subsequently euthanized by cervical dislocation. Eyes were enucleated, the anterior segment and vitreous was removed and posterior eyecups were placed in fixative for histological studies or oxygenated Ames medium for electrophysiological studies. For each animal, retinal tissue from one eye was used for electrophysiological experiments and the contralateral eye was processed for either light or electron microscopy. All procedures were performed under normal visible-light illumination, and therefore the retina is expected to be well light-adapted.

Immunohistochemistry For Light Microscopy

Posterior eyecups were fixed for 30 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde (PF) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH = 7.4). The tissue was cryoprotected in graded sucrose solutions (10%, 20%, 30%), embedded in OCT cryosectioning medium and vertically sectioned at 14 μm. Non-specific binding sites were blocked with an incubation buffer containing 3% normal horse serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 0.025% NaN3 in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) for 10 minutes. Primary antibodies were diluted in the same buffer and applied to tissues overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibodies were conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, 594 or 647 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and used at a dilution of 1:800. These were applied for 1 hour at 25°C. For double-labeling experiments, sections were incubated in a mixture of primary antibodies followed by a mixture of secondary antibodies. The details of all primary antibodies used in this study are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Antigen | Host | Source | Cat. No: | Dilution | Antigen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CtBP2 (RIBEYE) |

Mouse | BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA. |

612044 | 1:5000 | Amino acids 361-445 (C- terminus) of mouse CtBP2 |

|

| |||||

| GluR1 | Rabbit | Millipore, Billerica, MA. |

AB1504 | 1:1000 | C-terminal peptide of rat GluR1 conjugated to KLH with glutaraldehyde (SHSSGMPLGATGL) |

|

| |||||

| GluR2 | Mouse | Millipore, Billerica, MA. |

MAB397 | 1:500 | Recombinant fusion protein TrpE-GluR2 (putative N- terminal portion, amino acids 175-430) |

|

| |||||

| GluR4 | Rabbit | Millipore, Billerica, MA. |

AB1508 | 1:800 | C-terminal peptide of rat GluR4 conjugated to BSA with glutaraldehyde (RQSSGLAVIASDLP) |

| mGluR6 | Sheep | Gift from Dr C. Morgans, OHSU, OR. |

1:100 | C-terminal 19 amino acids of rat mGluR6 |

|

| PKC | Mouse | Sigma, St Louis, MO. |

P5704 | 1:400 | Amino acids 296-317 of PKC |

|

| |||||

| PKC-α | Rabbit | Sigma, St Louis, MO. |

094K4810 | 1:40,000 | C-terminal V5 region of rat PKCa; amino acids 659-672 |

|

| |||||

| PNA-488 | Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA |

L21409 | 1:1000 | lectin PNA from Arachis hypogaea conjugated to Alexa-488 |

|

Pre-Embedding Immuno-electron Microscopy

The pre-embedding immuno-electron microscopy method has been described in detail previously (Puthussery and Fletcher, 2004). Posterior eyecups were placed in a fixative containing 4% PF, 0.01% glutaraldehyde (GA) and 1 mM CaCl2 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) for 30 minutes and then fixed for a further 30 minutes in the same fixative without GA. Incubation buffers were the same as that used for light microscopy except for the exclusion of Triton X-100. Seventy micrometer thick agar-embedded retinal sections were blocked for 2 hours and then incubated in anti-PKCα primary antibody (1:10000) for 6 nights at 4°C. A biotin-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit secondary antibody was applied for 2 hours at 25°C. The signal was amplified with a Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) and visualised with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine-H202. Sections were post-fixed for one hour in 2.5% GA before silver intensification, gold toning and further post-fixation in 0.05% OsO4. Vibratome sections were dehydrated and embedded in EmBed Resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) for ultramicrotomy. Ultrathin sections (90 nm) were collected on uncoated copper grids and contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate solutions before viewing with the electron microscope.

Microscopy

Confocal images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope with a 63×/1.40 oil-immersion objective. All images were from a single image plane (optical section thickness 0.41 μm), unless otherwise indicated.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed on a Tecnai 12 microscope using an operating voltage of 80kV. Digital images were acquired with an AMT 542 camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, MA).

Further image processing was confined to adjustment in the brightness, contrast and sharpness of TEM and confocal images with Adobe Photoshop 7.0. In all cases, such procedures were applied equally across the whole image.

Electrophysiology

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma unless otherwise stated. Posterior eyecups were placed in oxygenated Ames medium at 25°C. The retina was isolated, mounted ganglion cell side down on a 0.8 μm cellulose membrane filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and vertically sliced (~300 μm) using a custom-made tissue slicer as described previously (Berntson and Taylor, 2000). Slices were transferred to a recording chamber, which was perfused at a rate of ~2 ml/min with bicarbonate-buffered Ames medium continuously bubbled with 95% O2, 5% CO2. For ON bipolar cell recordings the chamber was heated to 31-33°C, and the medium was supplemented with 4 μM DL-AP4 (DL-aminophosphonobutyric acid; Tocris, Ballwin, MO) to maximally activate mGluR6 receptors, and therefore chemically simulate darkness. For recording agonist responses from iGluR receptors, the preparation was maintained at room temperature (~22-24°C). Slices were viewed with an Olympus BX upright microscope fitted with a 40x water immersion objective and infrared gradient contrast optics (Dodt et al., 2002).

Patch electrodes were fabricated from thick-walled borosilicate glass to have a resistance of 10-15 MΩ. The electrodes were filled with an intracellular solution comprising (in mM): 135 K-methylsulfonate, 6 KCl, 2 Na2-ATP, 1 Na-GTP, 1 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 5 Na-HEPES. Solutions were adjusted to pH 7.4 with KOH. Alexa 488 hydrazide (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) was added at a concentration of 100 μM for morphological identification of bipolar cell types. In order to save time in the face of rapid run-down of the mGluR6 responses upon obtaining a whole-cell recording, series resistance compensation was not implemented. However, 5 mV voltage pulses were routinely applied at the end of the recording to obtain an estimate of the series resistance. In a sample of 21 cells across all ages, series resistance averaged 24±16 MΩ (range = 8.6 to 78 MΩ, ±standard deviation), and the average maximum voltage error calculated for the peaks of the simulated light responses was 3.2±2.2 mV (±standard deviation). Such errors will result in peak current errors of less than 4%, and since such errors were small compared to the variability in the response amplitudes, they were ignored.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed with a HEKA EPC-9 patch-clamp amplifier. Bipolar cell responses were elicited at all ages by pressure application of glutamtergic agonists and antagonists. The puff-electrode comprised a standard patch-pipette with a resistance of ~5 MΩ and filled with extracellular solution supplemented with either; 600 μM of the mGluR6 antagonist, CPPG ((RS)-α-cyclopropyl-4-phosphonophenylglycine; Tocris) for RBC and ON-CBC recordings, or a mixture of 200 μM kainate + 200 μM AMPA for OFF-CBC recordings. Pulses were delivered onto bipolar cell dendrites for 1 sec at ~10 psi using a Picospritzer II (Parker Instrumentation, Fairfield, NJ). Stimulation of bipolar cells has the potential to indirectly activate nearby amacrine cells, which could provide inhibitory feedback onto the axon terminals of the recorded bipolar cell. In order to obviate possible contamination of the recorded currents from GABAergic or glycinergic amacrine cell feedback, we set the holding potential to −70mV, close to the predicted chloride equilibrium potential. Current responses were digitally sampled at 5 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz. Currents were further filtered off-line with a −3 dB amplitude cut-off of 100 Hz. OFF-line filtering and analysis was performed using Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR).

Analysis

The amplitude and kinetics of the agonist-induced responses were characterized by measuring four parameters; the 10-90% rise-time of the response, the decay time-constant, the peak amplitude and the amplitude at the end of the puff stimulus. The 10-90% rise-time was estimated from a sigmoidal fit to the activation phase of the response (Fig. 1D). The decay time-constant was estimated by fitting a single exponential function to the decay phase after the peak of the response. The peak was estimated as the difference between the initial baseline current level, averaged over a 0.5 sec interval, and the maximum inward current, averaged over a 20 ms interval. The amplitude at the end of the puff application was determined as the average current over a 50 ms interval.

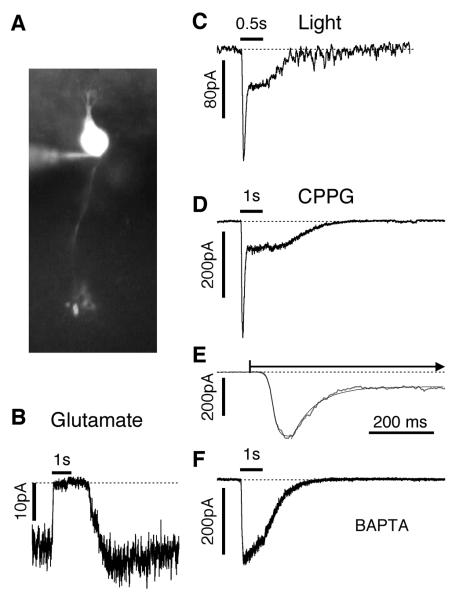

Figure 1.

Agonist and light responses in wild-type rod bipolar cells. Holding potential in B-D is −70 mV. Duration of drug application is 1 sec. A. Fluorescence image of a typical RBC filled with Alexa-488 during a recording. B. Membrane current in response to a saturating 0.5 sec light flash in a RBC in a wt retina. C. Outward current elicited by puffing 1 mM glutamate onto the dendrites of a RBC in a bleached retinal slice. Note the suppression in membrane noise levels as the tonic mGluR6 current is reduced. D. Simulated light response in a wt RBC elicited by puffing 600 μM CPPG onto the dendrites in the presence of 4 μM APB. Middle panel: Simulated light response on an expanded time-scale showing the fit of a sigmoidal function to the rising phase, and an exponential function to the decay phase. Bottom panel: Simulated light response with 20 mM BAPTA in the recording electrode. The response is sustained and lacks the inactivation seen in the two panels above.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 4.0a for Macintosh (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA). Two-tailed student’s t-test was performed, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant for normally distributed data. Where multiple comparisons were made, an adjusted P value of P < 0.025 was deemed significant.

Results

The aim of this study was to evaluate changes in bipolar cell function in rd10 mice and to correlate them with key anatomical markers. Due to the progressive loss of the rod and cone photoreceptors, we needed to use a physiological assay that was independent of photoreceptor function. To this end, we used pharmacological methods to simulate light activation (Snellman and Nawy, 2002; Nawy, 2004). In a dark-adapted preparation, a rod-bipolar cell (RBC, Fig. 1A) responds to a saturating light step with a rapid inward current, that reaches a transient peak and decays to a steady current level (Fig. 1C; Berntson and Taylor, 2000). In a bleached preparation, such as we are using, direct application of glutamate to a RBC produces a small outward current, and a concomitant decrease in membrane noise levels (Fig. 1B; Yamashita and Wässle, 1991). This result suggests that glutamate release from rods in the bleached preparation is insufficient to saturate the mGluR6 receptors in the RBCs, with the result that there is a tonic mGluR6 receptor mediated inward cation current. We simulated darkness in the bleached preparations by including 4 μM APB in the bath solution to completely suppress the tonic mGluR6-sensitive current and thus to simulate the high receptor occupancy that occurs in a dark-adapted retina.

Light responses were simulated by applying the mGluR6 antagonist, CPPG (600 μM), via a puffer electrode positioned immediately above the bipolar cell dendrites in the OPL. The CPPG rapidly displaced the APB and generated an inward current, thereby mimicking the reduced receptor activation that occurs as glutamate release is suppressed during a light flash (Fig. 1D). Such pharmacological responses were almost invariably obtained in wt cells in which intact dendrites could be visualized. In adult preparations the simulated responses activated rapidly, with 10-90% activation-times of 59±3 ms (n=13, Fig. 1E). By comparison, saturating light responses in dark-adapted rod-bipolar cells showed a 10-90% activation-time of 35±5 ms (n=5), only about a factor of two faster than the pharmacologically elicited responses. Moreover, the peak amplitudes generated pharmacologically were similar to saturating light-evoked responses (Fig. 2, cf Berntson and Taylor, 2000). Previous work showed that the transient component of the response was due to calcium-dependent feedback, which suppressed the mGluR6-gated current, most likely due to calcium influx through the mGluR6-gated channels themselves (Berntson et al., 2004). Similar to true light responses, the simulated light-responses became more sustained when intra-cellular calcium ions were rapidly chelated by internal BAPTA (Fig. 1F).

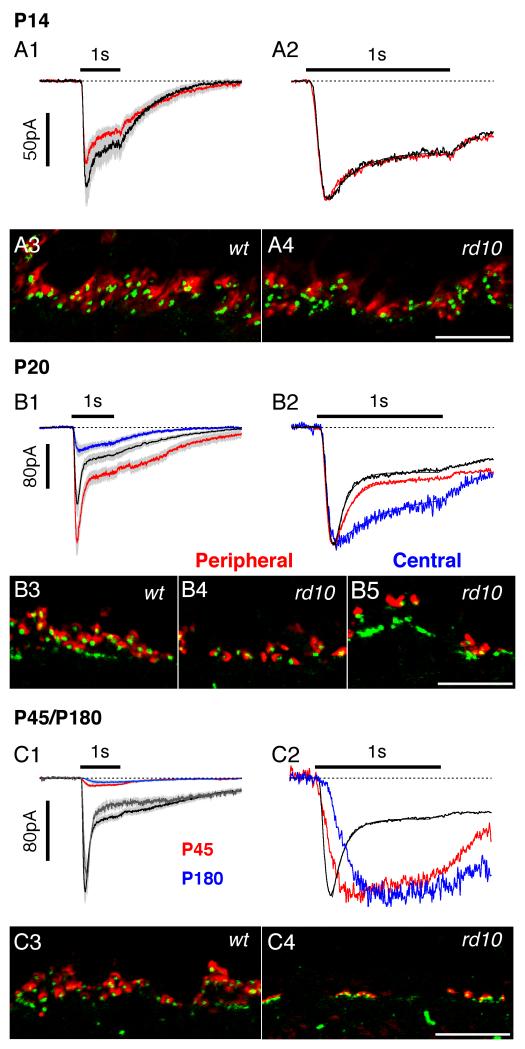

Figure 2.

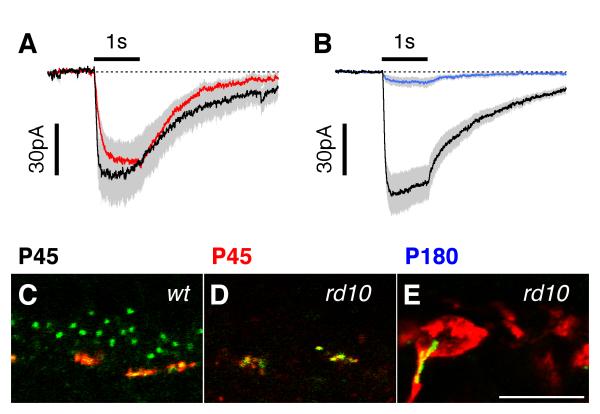

Function and localisation of the mGluR6 receptor in RBCs in wt and rd10 retinas at four developmental time points. Holding potential is −70 mV. Traces show averages for several cells with standard errors shown by grey shading. In panels A2-C2, exponential functions fitted to the decay phase are superimposed on the traces. In order to compare the time-courses of the responses, the amplitudes of traces in panels A2-C2 are normalized from the corresponding panels on the left. The immunohistochemical panels show vertical sections through the outer plexiform layer, with photoreceptors up. Vertical sections were labelled for mGluR6 (green) and the ribbon synapse marker, RIBEYE (red). Scale bar in all panels is 10 μm. P14: A1. Simulated light responses are characterized by a rapid increase to a peak followed by decay to a steady level. Responses are the average of 7 cells (wt, black lines) and 10 cells (rd10, red lines). A2. Normalized traces from A1 on an expanded time-scale, demonstrating that the kinetics of the responses in the two groups were essentially identical. The time-constants of the decay phases were 190 and 220 ms for the wt and rd10 traces respectively. A3, A4: mGluR6 puncta are closely associated with ribbon synapses in both the wt (A3) and rd10 (A4) retina. P20: Eccentricity dependent alterations in mGluR6 receptor function and localisation during peak rod apoptosis. B1. wt (black line, n=13) and rd10 simulated light responses. At less degenerated peripheral locations (rd10 red line, n=7) the response amplitudes were similar to control, while at more degenerated central regions (rd10 blue line, n=8) responses were smaller. B2: The superposition demonstrates that the kinetics of the rd10 responses in non-degenerated regions was similar to control, while responses in degenerated regions were more sustained. The time-constants of the exponential fits to the decay were (to the nearest 5 ms) 90, 125 and 385 ms for the wt, rd10 peripheral and rd10 central responses respectively. B3-5: There is a concomitant reduction in the number of ribbon synapses and mGluR6 receptor puncta in the rd10 retina, however, the residual mGluR6 receptor puncta remain associated with ribbon synapses. P45 & P180: Loss of mGluR6 receptor function and expression in RBCs in the late-stage rd10 retina. C1. Average simulated light responses from P45 wt (black, n=29), P45 rd10 (red, n=33), P180 wt (gray, n=6) and P180 rd10 (blue, n=6) retina. No measurable response was observed in 7 of the 33 rd10 cells from P45 and 2 of the 6 rd10 cells from P180. C2. The superposition demonstrates that the rd10 responses were slower to activate and much more sustained than the wt responses. The time-constant for the exponential fit to the decay phase (to the nearest 5 ms) was 100 ms C3,4: In the rd10 retina, residual mGluR6 expression is seen primarily in clusters at the inner aspect of the outer plexiform layer, a pattern consistent with expression on ON-cone bipolar cells.

In order to characterize changes in rod-bipolar cell function as the disease progressed, we measured the 10-90% rise-time, peak amplitude, and relative amplitude of the sustained component in wt and rd10 mice at four different ages; at eye-opening (~P14), at the peak of photoreceptor apoptosis (~P20), after complete degeneration of rod photoreceptors (~P45), and after complete degeneration of cone photoreceptors (~6 months).

Although changes in mGluR6 expression have been documented previously in the rd10 model (Gargini et al., 2007, Barhoum et al., 2008), the rate of photoreceptor degeneration can vary markedly depending on the lighting conditions in the animal housing environment (Pang et al., 2008). In light of this, we used immunohistohemistry to monitor the distribution of the mGluR6 receptor relative to the location of ribbon synapses (RIBEYE labelling) in contralateral eyes from the group of animals used for the physiological experiments. In this way, we could more accurately compare the physiological changes with the loss of mGluR6.

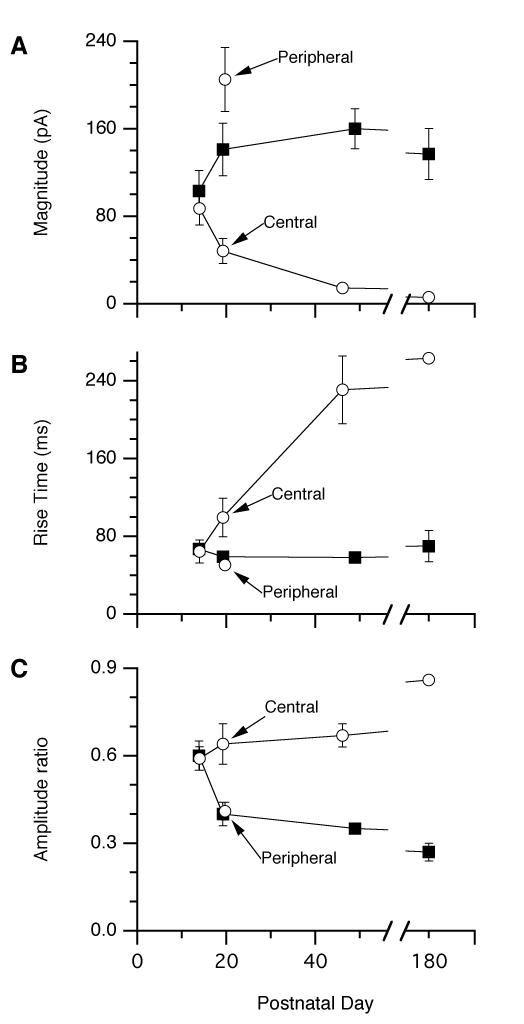

P14: Eye-opening

The rod-to-RBC synapse appears fully developed in the P14 mouse retina, showing invagination of RBC dendrites into the rod spherule at the ultrastructural level (Olney, 1968) and maturation of the ribbon synaptic complex (Sherry et al., 2003; von Kriegstein and Schmitz, 2003). Photoreceptor apoptosis has not commenced in the rd10 retina at this time, and we would therefore predict that synaptic function and organisation would be normal. Indeed, at P14, simulated light responses obtained in two wt retinas and in three rd10 retinas were statistically indistinguishable (Fig. 2A1, Fig. 3). Peak amplitudes were −101±19 pA (wt, n=7, range −41 to −173 pA) and −87±15 pA (rd10, n=8, range −12 to −186 pA). The corresponding 10-90% rise-times were 67±5 ms (wt) and 64±12 ms (rd10), and the relative amplitude of the sustained inward current was 0.60±0.05 (wt) and 0.59±0.04 (rd10). After normalization of the peak amplitude, the time-course of the responses were remarkably similar (Fig. 2A2), including the decay phase, which followed a single exponential time-course (superimposed lines, Fig. 2A2) with time constants of 190 ms (wt) and 220 ms (rd10).

Figure 3.

Summary data showing changes to in the magnitude of the RBC responses (A), the 10-90% rise time (B) and ratio of the sustained to the peak response amplitude (C) as a function of postnatal age in wt (black squares) and rd10 (open circles) retinas. Parameters were measured separately for each cell and averaged together. The error bars show the standard-error of the mean. Due to the small sizes of the individual responses, the data points for the rd10 P180 data in A, B & C were obtained from analysis of the averaged response for all cells, as shown by the blue trace in Fig. 5C.

At P14, double labelling with the ribbon synapse marker, RIBEYE, and mGluR6 showed crescent-shaped RIBEYE labelling immediately adjacent to the mGluR6 receptor puncta in both the rd10 and wt (Fig. 2 A3, A4), suggesting normal localisation of the rod bipolar cell dendritic tips at the ribbon synapse complex. These morphological data are consistent with the physiological responses, which show that prior to the onset of photoreceptor apoptosis, outer retinal synaptic function in the rd10 retina is essentially normal.

P20: Peak Apoptosis

In the rd10 retina, the peak period of photoreceptor apoptosis occurs between P18-P25 and follows a central-to-peripheral gradient (Gargini et al., 2007; Barhoum et al., 2008). We studied retinas at around P20, where we could identify central areas of severe degeneration and peripheral areas that were relatively unaffected. Within the same retinal preparation, we found marked changes in the physiological responses depending on the number of overlying photoreceptor cell bodies, which we used to gauge the degree of degeneration. We divided 15 RBCs from three rd10 retinas into two groups; the first group, labelled as “peripheral” included seven cells from regions with at least 6-7 layers of overlying photoreceptor somata. The second group, labelled as “central”, included eight RBCs from regions with less than six layers of overlying photoreceptor somata. The control group comprises 13 RBCs sampled randomly from central and peripheral regions in five retinas. The RBC responses recorded from the non-degenerated peripheral regions were statistically indistinguishable from wt, while the responses from the central group were significantly different for all parameters (Fig. 2 B1, B2; Fig. 3). Peak amplitudes of the simulated light-responses were −141±24 pA (wt, n=13, range −41 to −300 pA), −205±29 pA (rd10 peripheral, n=7, range −56 to −312 pA) and −48±11 pA (rd10 central, n=8, range −21 to −110 pA). The corresponding 10-90% rise-times were 59±3 ms (wt), 51±3 ms (rd10 peripheral) and 99±20 ms (rd10 central), and the relative amplitude of the sustained inward current was 0.40±0.04 (wt), 0.41±0.03 (rd10 peripheral) and 0.64±0.07 (rd10 central). Thus, while the responses in central retina were significantly smaller, they were also more sustained than those in wt or peripheral rd10 preparations, and the time-course appeared more similar to that seen early in development (Fig. 2A2). Thus these physiological results indicate that along with the frank loss of synaptic contacts, there are more subtle functional changes within the synapses that support the residual mGluR6 responses.

Consistent with these physiological results, double labelling of mGluR6 with RIBEYE showed that as in the wt retina, the mGluR6 receptors in peripheral rd10 retinas are closely associated with the ribbon synapses (Fig. 2 B3, B4), while in the degenerated central areas, the loss of dendrites is evident from the loss of mGluR6 receptor puncta associated with ribbon synapses (Fig. 2B5).

P45 and P180: Late Stage Disease

Only a single layer of putative cone photoreceptor nuclei remain in the ONL of the rd10 retina around P45. Simulated light responses obtained from 29 RBCs in ten wt retinas and 33 RBCs in eight rd10 retinas differed significantly for all parameters (Fig. 2C1, Fig. 3). Peak amplitudes were −160±18 pA (wt, n=29, range −25 to −426 pA) and −14±2 pA (rd10, n=26, range −3 to −52 pA, seven cells produced no detectable response). The corresponding 10-90% rise-times were 58±3 ms (wt) and 191±30 ms (rd10), and the relative amplitude of the sustained inward current was 0.35±0.02 (wt) and 0.67±0.04 (rd10). After normalization of the peak amplitude, it is clear that the residual responses in the rd10 cells are much more sustained than the wt control (Fig. 2C2, red).

At 6 months (~P180), both rod and cone photoreceptors were completely degenerated, but in a sample of six cells a small CPPG response remained in the RBCs (Fig. 2C1 blue line, peak amplitude −10±0.5pA, range −2 to −27pA, 2 cells showed no response), which was not different to that observed at P45 (Fig. 2C2, red line). The wt responses (peak amplitude −137±23pA, range −50 to −218pA), were also unchanged from the P45 time-point (Fig. 2C1, black & grey lines, Fig. 3). The corresponding 10-90% rise-times were 71±10 ms (wt) and 260 ms (rd10), and the relative amplitude of the sustained inward current was 0.27±0.03 (wt) and 0.86 (rd10); the rd10 parameters were measured from the average response (Fig. C1, blue line).

Consistent with these physiological findings, at P45, residual mGluR6 expression was associated with RIBEYE-immunoreactive ribbon synapses (Fig. 2 C3, C4), however, most of the residual staining was confined to thin horizontal profiles in the proximal OPL, consistent with localisation at cone pedicles. In the following section we examined the evidence for continued cone-bipolar cell function at late in the degenerative process.

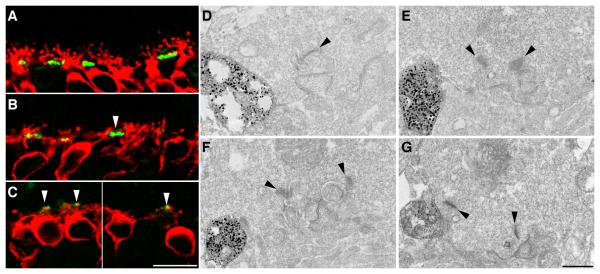

Rod bipolar cell dendrites are targeted to cone pedicles in the rd10 retina

In the wt retina, rod bipolar cell dendrites extend from the soma, and bypass the cone pedicles to invaginate the rod spherules (Fig. 4A). In rd10 retinas, we observed retraction and remodelling of rod bipolar cell dendrites as early as P20 as has been described previously (Gargini et al., 2007). To investigate the targets of these remodelled dendrites, we double labelled for PKC and the cone-specific marker, peanut agglutinin (PNA). Within degenerated regions at P20, the normal bushy appearance of RBC dendrites became sparser and some processes appeared to be associated with the base of cone pedicles (Fig. 4B, arrow-head). By P45, the density of RBC dendrites was further reduced and remaining dendrites appeared to be directed towards cone pedicles (Fig. 4C, arrow-heads).

Figure 4.

Rod bipolar cells send ectopic processes to cone pedicles in the rd10 retina. A-C: Confocal micrographs of vertical sections of the rd10 retina labelled for PKC (red) and PNA (green). Rod bipolar cell dendrites are not seen to make contacts at the base of the cone pedicles in the wild-type retina (A). At P20 (B), bipolar cell dendrites have lost their typical bushy appearance and show some straightened processes that appear to be targeted to cone pedicles (white arrowheads). By P45 (C), there is further loss of bipolar cell dendrites and the residual bipolar cell processes appear to be directed towards cone pedicles. D-G: Transmission electron micrographs of cone pedicles of the P20 rd10 retina after immunolabelling with PKC. PKC stained rod bipolar cell dendrites make contacts at the base of cone pedicles. Ribbon synapses are indicated with black arrowheads. Scale Bar A-C: 10 μm, D-G: 0.5 μm.

To confirm the aberrant localization of RBC dendrites at cone pedicles, we labelled RBCs with an antibody against PKCα and used pre-embedding immunoelectron microscopy to examine the synaptic localization of the dendrites. In wt tissue we occasionally noted labeled processes at the lateral aspect of the cone pedicles and these were presumed to be dendrites en route to the rod spherules (data not shown). By contrast, in the rd10 retina, we found numerous examples of PKCα immunoreactive processes that made direct contacts with the base of cone pedicles, often in very close proximity to a ribbon synapse (Fig. 4D-G). In many cases, these contacts were associated with a membrane density reminiscent of that seen at the site of OFF-CBC flat contacts with cone pedicles. Such aberrant RBC contacts were not observed in the wt retina. These data suggest that during the peak period of photoreceptor degeneration, RBCs retract their dendrites from the rod spherules and re-model to form some aberrant contacts with cone pedicles.

The cone photoreceptors survive considerably longer than the rods in the rd10 retina, and therefore we expected any functional deficits in postsynaptic CBC function to be delayed relative to the RBCs. To test this idea, we used identical techniques to measure postsynaptic responses in ON- and OFF-CBCs in wt and rd10 retinas before (~P45) and after (~P180) complete degeneration of the cone photoreceptors.

ON-CBC function is altered after degeneration of cones

At P45, recordings from eight ON-CBCs in four wt retinas and 11 ON-CBCs in six rd10 retinas produced quite variable responses, both in amplitude and time-course. The peak amplitudes for the wt and rd10 groups were −67±18pA (n=8) and −57±11pA (n=11), and overall the two groups did not differ significantly in amplitude or time-course (Fig. 5A). In contrast, by ~P180, the amplitudes of the rd10 responses (−6±3pA, n=8) were markedly reduced compared to wt (−72±12pA, n=9, Fig. 5B), suggesting that cone survival is necessary for normal functioning of the mGluR6 receptors on ON-CBCs.

Figure 5.

mGluR6 receptor function and localization in ON-cone bipolar cells. Holding potential is −70 mV. Traces show averages for several cells with standard errors shown by grey shading. A. At P45, prior to complete cone degeneration, wt (black, n=8) and rd10 (red, n=11) simulated light responses have similar amplitudes and time-courses. B. At P180, rd10 response amplitudes (blue, n=8) are markedly reduced compared to wt (black, n=9). C-E: Double labelling for mGluR6 (green) and the cone pedicle marker, peanut agglutinin (red). In the rd10 retina at P45 (D), all residual mGluR6 receptor puncta colocalise with the PNA stained cone pedicles (yellow), indicating that the remaining mGluR6 receptors are expressed by ON-cone bipolar cell dendrites. E: By P180, mGluR6 immunoreactivity (green) is completely lost from the OPL and is restricted to the soma and axons of rod bipolar cells (red). Scale Bar C-E = 10 μm.

In contralateral eyes, we double labelled for mGluR6 and the cone photoreceptor marker PNA, and found that clusters of residual mGluR6 receptor puncta were exclusively associated with the base of cone pedicles in the P45 rd10 retina (Fig. 5 C,D). This pattern is consistent with the continued sensitivity of the ON-CBCs to APB/CPPG application. By ~P180, no punctate mGluR6 immunoreactivity was evident in the OPL of the rd10 retina, however, some sparse residual labeling was observed on rod bipolar cell somata and axons (Fig. 5E).

OFF- CBCs maintain functional expression of KA/AMPA receptors

Signal transmission from cone photoreceptors to OFF-CBCs is driven by activation of kainate and AMPA type ionotropic glutamate receptors. We assessed the postsynaptic responsiveness of OFF-CBCs of the rd10 retina before and after complete degeneration of cone photoreceptors (~P45 and ~P180 respectively). The application techniques were identical to the preceding experiments except that the puff-electrode contained a combination of 200 μM kainate and 200 μM AMPA. At both time-points, we encountered two types of responses in the group of cells sampled; those that responded with small transient inward currents and those that responded with larger sustained currents. We averaged sustained KA/AMPA responses from three OFF-CBCs in wt retina (−155±64pA; Fig. 6A, black) and four OFF-CBCs in rd10 retina at P45 (−200±42pA; Fig. 6A, red). The time-course and amplitude of the responses were similar. Similarly, at P180, average sustained responses obtained from four OFF-CBCs in wt (−265±80pA; Fig. 6B, black), and three OFF-CBCs in rd10 retinas (−230±54pA; Fig. 6B, blue), were very similar to the P45 data. A second group of OFF-CBCs produced transient responses, characterized by an initial peak followed by an inactivating phase. The peak amplitudes of these responses were systematically smaller than for the sustained CBCs, however, like the sustained responses the peak amplitudes of the wt and rd10 responses at P45 (wt: −56±11pA; rd10: −31±7pA) were similar to each other and did not change dramatically at P180 (wt: −54±23pA; rd10: −29±18pA) (Fig. 6 C,D).

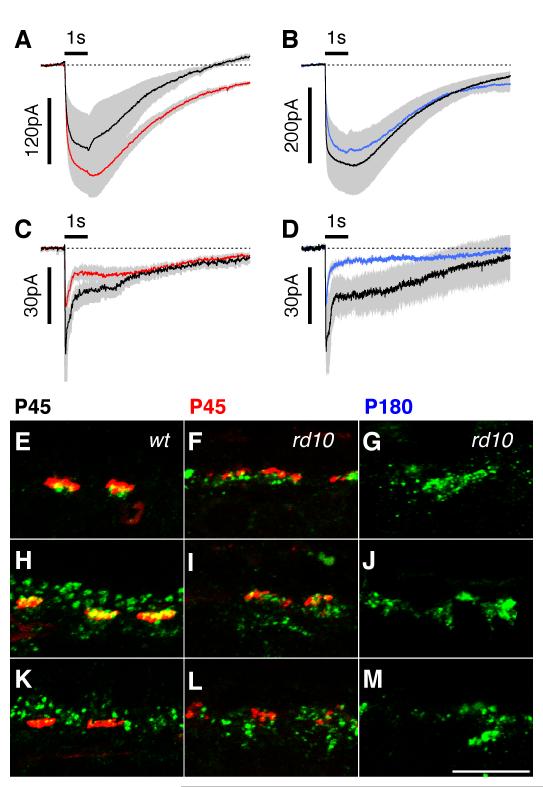

Figure 6.

Function and expression of ionotropic glutamate receptors in OFF bipolar cells. Holding potential is −70 mV. Traces show averages for several cells with standard errors shown by grey shading. A. At P45, responses to puff application of KA/AMPA have similar amplitudes and time-courses in wt (black, n=3 cells in one retina) and rd10 (red, n=4 cells in 2 retinas). B. Similarly, at P180, responses to KA/AMPA are indistinguishable in wt (black, n=4 cells in 2 retinas) and rd10 (blue, n=3 cells in 2 retinas) retinas. C,D: A second group of cells display more transient response kinetics under identical agonist application conditions. C: Average KA/AMPA responses in OFF-CBCs from P45 preparations; wt, black, n=4 cells in two retinas, and rd10, red, n=4 cells in two retinas. D Average KA/AMPA responses in OFF-CBCs from P180 preparations; wt, black, n=3 cells in two retinas, and rd10, blue, n=3 cells in two retinas. E-G. Double labelling of GluR1 (green) with PNA (red). In the wt retina (E), GluR1 is associated with cone pedicles and expression of GluR1 is seen at P45 (F) and P180 (G) in the rd10 retina. H-J. Double labelling of GluR2 (green) with PNA (red) in wt (H) and rd10 (I,J) retinas. K-M. Continued expression of GluR4 is seen at P45 and P180 in the rd10 retina. Scale Bar E-M = 10 μm.

The absence of degeneration in the OFF-CBC responses stands in sharp contrast to the mGluR6 responses in the ON-CBCs, which show dramatic degeneration from P45 to P180 (Fig. 5). This result implies that OFF-CBCs do not require the presence of cone photoreceptors to maintain their complement of postsynaptic glutamate receptors. In order to account for this preservation of postsynaptic function we evaluated the immunohistochemical localisation of three different AMPA receptor subunits that are expressed by OFF-CBCs in the mouse retina (Hack, 2001; Fig. 6E-M). In the wt retina, GluR1 appeared to be associated exclusively with PNA labeled cone pedicles (Fig. 6E), and this pattern of labeling was largely preserved in the degenerated rd10 retina (Fig. 6F). The GluR2 receptor subunit is associated with both rod and cone synaptic terminals in the wt retina (Fig. 6H). In the rd10 retina, there was a large reduction in rod spherule-associated GluR2 expression, however, clusters of residual expression of GluR2 remained at cone pedicles (Fig. 6I). Residual clusters of GluR4 receptor expression were also noted in the rd10 retina, with clusters of GluR4 immunoreactivity associated with cone pedicles (cf Figs 6 K, L). The pattern of GluR2 and GluR4 labelling was less punctate in the rd10 retina compared with the wt.

We also evaluated GluR receptor localization at ~P180. Consistent with previous reports (Gargini et al., 2007), we found no evidence for the presence of cone photoreceptors in the rd10 retina at this time (labeling for PNA and recoverin, data not shown). Despite the absence of cone photoreceptors, we noted robust expression of clusters of GluR1, 2 and 4 in the rd10 retina, similar to that observed at ~P45 (Figs. 6 G,J,M). It should be noted that GluR1, 2 and 4 are also expressed by horizontal cells (Hack et al., 2001), and therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that some or all of the remaining iGluR expression in the rd10 retina was associated with horizontal cells. However, given the preservation of functional responses in the OFF-CBCs of the rd10 retina, it seems likely that these cells maintain some level of iGluR expression.

Discussion

Retinal degeneration is marked by the progressive loss of photoreceptors, and a concomitant loss of visual function. Our study is the first to track the in situ responses of bipolar cells during the progression of retinal degeneration, and provides the first direct electrophysiological evidence for bipolar cell dysfunction in the rd10 model of retinal degeneration.

Rod bipolar cell function

ERG studies have documented alterations in the timing and amplitude of the b-wave of the scotopic ERG as early as postnatal day 18 (Chang et al., 2007; Gargini et al., 2007), however, it has not been firmly established whether these changes simply reflected loss of input from rod photoreceptors, or whether there are changes in postsynaptic sensitivity in the second-order neurons (Gargini et al., 2007). In this study, changes in RBC response amplitude and kinetics were seen in the central retina as early as P20, where rod-photoreceptor degeneration had caused a marked reduction in the thickness of the outer nuclear layer. As expected, in these regions mGluR6 expression was also reduced. These findings indicate that the localization and function of mGluR6 receptors in RBCs is critically dependent on the presence of viable rod photoreceptors.

Along with the marked changes in the amplitude of the mGluR6 responses, there were also alterations in the time-course of the responses. In the wt controls at the time of eye opening (P14), the simulated light-responses were much more sustained than at P20 and beyond, and a similar pattern was evident for cells in non-degenerated regions of the rd10 retinas at P20. We have shown here that intracellular BAPTA renders the pharmacological responses more sustained (Fig. 1D), and in line with previous studies of light-evoked RBC responses in the mouse (Berntson et al., 2004), we propose that increased postsynaptic calcium concentration also produces the transient component of pharmacologically-generated responses. The finding that the responses are more sustained at P14 indicates that the mechanisms mediating this calcium feedback are not fully developed at P14. Moreover, the finding that mGluR6 responses become more sustained in degenerated retinas raises the possibility that the mechanisms that mediate the calcium feedback are down-regulated sooner than other elements in the transduction pathway.

Degeneration also affected the activation rate of the responses. In rd10 retinas, the slower 10-90% activation time at P20 in central versus peripheral retina was significant and became more marked at later times (Fig. 6B). A reduced concentration of mGluR6 receptors could slow the activation rate, however, it is possible that changes in other elements of the mGluR6 signal transduction pathway, such as regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) proteins, could contribute to the slowed activation (Dhingra et al., 2004; Morgans et al., 2007).

It is important to acknowledge that a previous study of responses to exogenously applied glutamate in wt and rd10 mouse retinas at P60 produced rather different results (Barhoum et al., 2008). These authors found that in both wt and rd10 retinas about 50% of the recorded RBCs responded, but that there was no difference in the average amplitudes of the responses, despite there being a severe down-regulation of the mGluR6 receptors in the rd10 preparations. Perhaps our use of more specific pharmacological agents might be a factor in accounting for the differences between the two studies.

Cone bipolar cell function

ON-CBCs maintained normal mGluR6 receptor localisation and functional responses prior to cone photoreceptor degeneration (P45), but, by six months, there was a marked reduction in response amplitudes that correlated with loss of mGluR6 receptor expression. The relative longevity of ON-CBC function seems likely to reflect the delayed degeneration of the cones, supporting the notion that mGluR6 function is dependent on photoreceptor input. To our knowledge, the single-cell function of ON-CBCs has not been directly examined previously in any model of retinal degeneration. However, previous ERG studies have reported deficits in the b-wave of the cone-isolated ERG around P20-30 (Chang et al., 2007; Barhoum et al., 2008). Since our results show normal localization and function of mGluR6 on ON-CBCs at this time, the reported ERG deficits probably reflect abnormal cone photoreceptor signaling or reduced efficiency of cone to ON-CBC transmission.

In contrast to the ON-CBCs, OFF-CBC functional responses were preserved at six months, suggesting that the loss of cones does not down-regulate ionotropic glutamate receptor expression. Previous studies have indicated that OFF-CBCs in the rd10 retina show dendritic retraction at 4-5 months of age (Gargini et al., 2007; Barhoum et al., 2008), however, our data demonstrate the persistence of iGluR expression and function despite this remodeling. Although direct electrophysiological recordings have not been previously made from OFF-CBCs in degenerated retina, relative preservation of OFF ganglion cell responses compared to ON ganglion cell responses has been reported in the rd1 retina (Stasheff, 2008). The function of OFF-CBCs has also been investigated using agmatine, a tracer of cation channel activity. Using this approach, preservation of OFF-CBCs responses has been reported in human retina, and in some animal models where there are remnant clusters of surviving cone photoreceptors, but not in models that show complete cone decimation such as the rdcl mouse (Marc et al., 2007). It is worth noting here that while previous work has proposed an up-regulation of iGluRs on RBCs in a rabbit and human retina (Marc et al., 2007), we found no electrophysiological evidence for such ectopic expression in the rd10 mouse.

Two different iGluR mediated responses were observed in the OFF-CBCs; transient and sustained. It seems likely that these two response types reflect the expression of different iGluR receptors, with sustained responses most likely originating from kainate preferring receptors, and the transient responses from the rapidly desensitizing AMPA preferring receptors (DeVries, 2000).

Rod bipolar cell re-modeling

We observed progressive alterations in the dendritic structure of rod bipolar cells in the rd10 retina (data not shown) as have been reported previously (Gargini et al., 2007; Barhoum et al., 2008). Although the typical bushy dendritic branching of RBCs is lost in the rd10 by P45, dye-filling during electrophysiological recordings revealed clear evidence of sparse residual processes. Using confocal and electron microscopy, we showed that these new or remodeled processes are targeted to cones, where they appear to make flat contacts at the base of the pedicles as early as P20. Such aberrant connectivity of RBCs to cones has been reported in other animal models of rod photoreceptor degeneration including the P347L pig (Peng et al., 2000), P23H rat model (Cuenca et al., 2005) and Rho-/- mouse (Haverkamp et al., 2006), however, it is not clear whether such contacts result in functional synaptic connections. Our physiological data show that residual postsynaptic responses are present in RBCs, and therefore ectopic connections could, in principle, support signaling from remaining cone photoreceptors to RBCs.

Implications for disease

Owing to its later onset of photoreceptor degeneration, the rd10 mouse is an excellent model for testing a variety of neuroprotective and restorative interventions for retinal degenerations. This study confirms that RBC functional development is normal in the rd10 retina, making it a more suitable model of human RP than the rd1 mouse, which shows abnormal development of the rod-to-rod bipolar cell synapse. Our results define the temporal window over which the bipolar cells of the rd10 retina remain responsive and thus may be more amenable to photoreceptor rescue. The relatively early loss of RBC function raises the possibility that late-stage replacement of rod photoreceptors might be less viable. However, our results indicate that CBC function is relatively preserved in the rd10 retina, with ON-CBCs maintaining functional mGluR6 expression until at least P45, whilst OFF-CBCs retain functional expression of ionotropic glutamate receptors for at least six months. These findings suggest that appropriately timed strategies targeting cone photoreceptor protection or replacement have a greater potential for success than rod-targeted therapies, which would require reestablishment of functional mGluR6 receptors on RBCs in order to be effective. These timelines are promising for the treatment of human RP, given that there is typically significant cone photoreceptor survival at the time of diagnosis, whilst substantial rod photoreceptor death may have already occurred.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NHMRC CJ Martin (Australia) and American Australian Association Fellowships (T.P.) and NEI grants EY09534 (R.M.D.) and EY017095 (W.R.T.).

References

- Bainbridge JW, Tan MH, Ali RR. Gene therapy progress and prospects: the eye. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barhoum R, Martinez-Navarrete G, Corrochano S, Germain F, Fernandez-Sanchez L, de la Rosa EJ, de la Villa P, Cuenca N. Functional and structural modifications during retinal degeneration in the rd10 mouse. Neuroscience. 2008;155:698–713. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson A, Taylor WR. Response characteristics and receptive field widths of on-bipolar cells in the mouse retina. J Physiol. 2000;524(Pt 3):879–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson A, Smith RG, Taylor WR. Postsynaptic calcium feedback between rods and rod bipolar cells in the mouse retina. Vis Neurosci. 2004;21:913–924. doi: 10.1017/S095252380421611X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanks JC, Adinolfi AM, Lolley RN. Photoreceptor degeneration and synaptogenesis in retinal-degenerative (rd) mice. J Comp Neurol. 1974;156:95–106. doi: 10.1002/cne.901560108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes C, Li T, Danciger M, Baxter LC, Applebury ML, Farber DB. Retinal degeneration in the rd mouse is caused by a defect in the beta subunit of rod cGMP-phosphodiesterase. Nature. 1990;347:677–680. doi: 10.1038/347677a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Dawson LD, LaVail MM, Sidman RL. Differential effect of the rd mutation on rods and cones in the mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1978;17:489–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Hawes NL, Pardue MT, German AM, Hurd RE, Davisson MT, Nusinowitz S, Rengarajan K, Boyd AP, Sidney SS, Phillips MJ, Stewart RE, Chaudhury R, Nickerson JM, Heckenlively JR, Boatright JH. Two mouse retinal degenerations caused by missense mutations in the beta-subunit of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase gene. Vision Res. 2007;47:624–633. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca N, Pinilla I, Sauve Y, Lund R. Early changes in synaptic connectivity following progressive photoreceptor degeneration in RCS rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1057–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH. Bipolar cells use kainate and AMPA receptors to filter visual information into separate channels. Neuron. 2000;28:847–856. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra A, Faurobert E, Dascal N, Sterling P, Vardi N. A retinal-specific regulator of G-protein signaling interacts with Galpha(o) and accelerates an expressed metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 cascade. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5684–5693. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0492-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodt HU, Eder M, Schierloh A, Zieglgansberger W. Infrared-guided laser stimulation of neurons in brain slices. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:PL2. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.120.pl2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargini C, Terzibasi E, Mazzoni F, Strettoi E. Retinal organization in the retinal degeneration 10 (rd10) mutant mouse: a morphological and ERG study. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:222–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.21144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack I, Frech M, Dick O, Peichl L, Brandstatter JH. Heterogeneous distribution of AMPA glutamate receptor subunits at the photoreceptor synapses of rodent retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp S, Michalakis S, Claes E, Seeliger MW, Humphries P, Biel M, Feigenspan A. Synaptic plasticity in CNGA3(-/-) mice: cone bipolar cells react on the missing cone input and form ectopic synapses with rods. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5248–5255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4483-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLaren RE, Pearson RA. Stem cell therapy and the retina. Eye. 2007;21:1352–1359. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLaren RE, Pearson RA, MacNeil A, Douglas RH, Salt TE, Akimoto M, Swaroop A, Sowden JC, Ali RR. Retinal repair by transplantation of photoreceptor precursors. Nature. 2006;444:203–207. doi: 10.1038/nature05161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marc RE, Jones BW, Watt CB, Strettoi E. Neural remodeling in retinal degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:607–655. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(03)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marc RE, Jones BW, Anderson JR, Kinard K, Marshak DW, Wilson JH, Wensel T, Lucas RJ. Neural reprogramming in retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3364–3371. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin ME, Sandberg MA, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Recessive mutations in the gene encoding the beta-subunit of rod phosphodiesterase in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 1993;4:130–134. doi: 10.1038/ng0693-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin ME, Ehrhart TL, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Mutation spectrum of the gene encoding the beta subunit of rod phosphodiesterase among patients with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3249–3253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgans CW, Wensel TG, Brown RL, Perez-Leon JA, Bearnot B, Duvoisin RM. Gbeta5-RGS complexes co-localize with mGluR6 in retinal ON-bipolar cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:2899–2905. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Iwakabe H, Akazawa C, Nawa H, Shigemoto R, Mizuno N, Nakanishi S. Molecular characterization of a novel retinal metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR6 with a high agonist selectivity for L-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11868–11873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawy S. Desensitization of the mGluR6 transduction current in tiger salamander ON bipolar cells. J Physiol. 2004;558:137–146. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW. An electron microscopic study of synapse formation, receptor outer segment development, and other aspects of developing mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1968;7:250–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang JJ, Boye SL, Kumar A, Dinculescu A, Deng W, Li J, Li Q, Rani A, Foster TC, Chang B, Hawes NL, Boatright JH, Hauswirth WW. AAV-mediated gene therapy for retinal degeneration in the rd10 mouse containing a recessive PDEbeta mutation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4278–4283. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YW, Hao Y, Petters RM, Wong F. Ectopic synaptogenesis in the mammalian retina caused by rod photoreceptor-specific mutations. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1121–1127. doi: 10.1038/80639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthussery T, Fletcher EL. Synaptic localization of P2X7 receptors in the rat retina. J Comp Neurol. 2004;472:13–23. doi: 10.1002/cne.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry DM, Wang MM, Bates J, Frishman LJ. Expression of vesicular glutamate transporter 1 in the mouse retina reveals temporal ordering in development of rod vs. cone and ON vs. OFF circuits. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:480–498. doi: 10.1002/cne.10838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter MM, Miller RF. Characterization of an extended glutamate receptor of the on bipolar neuron in the vertebrate retina. J Neurosci. 1985;5:224–233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-01-00224.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snellman J, Nawy S. Regulation of the retinal bipolar cell mGluR6 pathway by calcineurin. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1088–1096. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasheff SF. Emergence of sustained spontaneous hyperactivity and temporary preservation of OFF responses in ganglion cells of the retinal degeneration (rd1) mouse. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:1408–1421. doi: 10.1152/jn.00144.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strettoi E, Porciatti V, Falsini B, Pignatelli V, Rossi C. Morphological and functional abnormalities in the inner retina of the rd/rd mouse. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5492–5504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05492.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strettoi E, Pignatelli V, Rossi C, Porciatti V, Falsini B. Remodeling of second-order neurons in the retina of rd/rd mutant mice. Vision Res. 2003;43:867–877. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00594-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kriegstein K, Schmitz F. The expression pattern and assembly profile of synaptic membrane proteins in ribbon synapses of the developing mouse retina. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;311:159–173. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0674-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiland JD, Liu W, Humayun MS. Retinal prosthesis. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;7:361–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.060804.100435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M, Wassle H. Responses of rod bipolar cells isolated from the rat retina to the glutamate agonist 2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (APB) J Neurosci. 1991;11:2372–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-08-02372.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]