Abstract

Recruiting older adults to participate in intervention research is essential for advancing the science in this field. Developing a relevant recruitment plan responsive to the unique needs of the population before beginning a project is critical to the success of a research study. This paper describes our experiences in the process of recruitment of homebound older adults to test a community-based health empowerment intervention. In our study, the trust and partnership that existed between the research team and Community Action Agency facilitated the role of the home-delivered meal drivers as a trusted and untapped resource for study recruitment. Researchers can benefit from thinking creatively and developing meaningful partnerships when conducting research with older adults.

The number of people in the United States aged 65 and older increased tenfold in the last century and is expected to double in the first part of this century. Older adults are more likely to suffer from chronic illness, live in poverty, and be isolated from resources and services needed to maintain and promote their health (Administration on Aging, 2007). Thus, awareness of, and access to, personal resources and social contextual resources may play an important role in health promotion and management of chronic illness among older adults (Shearer, 2007; Shearer & Fleury, 2006), and represent critical areas of intervention for community health nursing. Our knowledge concerning the role of interventions to promote health and manage chronic illness in older adults, however, remains relatively limited. Further, few studies provide detail on the processes and procedures of recruitment (Dibartolo & McCrone, 2003; Jancey et al., 2006) among older adults, an at-risk and underserved population.

Recruiting older adults to participate in intervention research is essential to advance the science in this field. Guidance concerning the most effective strategies for recruiting older adults in intervention research is limited. Older adults often suffer from chronic illness and medical instability (Hawranik & Pangman, 2002), loss or limited sensory function (Gueldner & Hanner, 1989), limited cognitive capacity (Fulmer, 2001), and limited mobility (Bowsher, Bramlett, Burnside, & Gueldner, 1993). In addition, they often suffer from lack of transportation (Adams, Silverman, Musa, & Peele, 1997), unfamiliarity with research and research procedures (Crosby, Ventura, Finnick, Lohr, & Feldman, 1991), lower levels of education (Gueldner & Hanner), an unwillingness to make a time commitment to research (Resnick et al., 2003), inability to read or have access to newspapers (Gueldner & Hanner), or discomfort or concerns about safety when inviting someone unfamiliar into the home (Porter & Lanes, 2000). Any of these factors may contribute to the reluctance or refusal of older adults to participate in research (Harris & Dyson, 2001), and difficulty in access for recruitment.

Homebound older adults, those unable to leave home for reason of illness or incapacitating disability, constitute one group that is especially difficult to access within the community. Their participation in community-based research should be given priority, because they are at great risk for becoming marginalized due to a lack of essential resources and services. This paper describes our experiences in the process of recruitment of homebound older adults to test a community-based health empowerment intervention (HEI) designed to facilitate the engagement of older adults in the process of recognizing personal resources, social contextual resources, identification of desired goals, and the means to attain these goals. We first consider various approaches guiding the recruitment of older adults in community-based research; we then present an innovative combined approach used during recruitment of homebound older adults to the HEI, including the effectiveness of strategies driving the recruitment of homebound older adults. The paper is not intended to be a comprehensive work on strategies for recruiting homebound older adults, but rather a description of the process used in one research project.

Background

Subject recruitment is a major issue in gerontological research, with complications potentially leading to delays in starting the study or resulting in invalid findings if the researchers were not able to recruit subjects who met inclusion criteria (Grap & Munro, 2003). However, successful approaches to recruiting community-dwelling older adults provide encouragement. One strategy described in the literature entails no initial personal contact. Katula and colleagues (2007) reported that mass mailing was the most efficient method to recruit community-dwelling older adults for a clinical trial focusing on physical activity. Others have suggested that a two-step recruitment process, consisting of an introductory letter followed by a telephone call, was successful in recruiting community-dwelling older adults for home-based research (Taylor-Davis, Smiciklas-Wright, Davis, Jensen, & Mitchell, 1998).

Another approach focuses on recruitment of participants for community-based research prior to discharge from a hospital, rehabilitation center, or primary care office. Using this approach the researcher or recruiter implements recruitment strategies that focus on the study site staff rather than on the older adult participant. The goal is to foster staff enthusiasm for the study, which in turn fosters staff buy-in, their involvement in identifying participants (Gitlin, Burgh, Dodson, & Freda, 1995; Schulz, Wasserman, & Ostwald, 2006), and follow-up referrals to researchers (Adams et al., 1997).

A third approach focuses on study team members’ involvement in the community to recruit subjects. Recruitment of community-dwelling adults has been shown to be effective if strategies are tailored to the population of interest. For example, in their community-based influenza health study, Gonzalez, Gardner, and Murasko (2007) found that working collaboratively with leaders in the community to understand the needs of racially diverse older adults improved recruitment of diverse, healthy older adults. Moreover, face-to-face recruitment (Austin-Wells, McDougal, & Becker, 2006; Gonzalez et al.), endorsement from community leaders, personal contact, and monetary incentives produced the most responses from older adults in the community, regardless of ethnicity (Gonzalez et al.). Adams and colleagues (1997) found that face-to-face contact was more effective than recruiting from other sources and helped to reduce the uncertainty that older adults felt about participating. Another study took advantage of existing social networks by recruiting community members to serve as hostesses for “health parties” that involved social interaction, education, and recruitment for a breast cancer study. This strategy involved the hostesses inviting family and friends to their homes, where the study project recruiter organized the evening’s activities (Saddler et al., 2006).

Some researchers have found a combination of approaches to be useful. For example, Gill and colleagues used strategies for recruiting community-dwelling frail older adults for a home-based physical activity intervention including: (a) recruiting from a primary care practice, in which the older adults were identified and screened for physical frailty during office visits, and (b) recruiting from computerized patient rosters generated by primary care physicians, from which older adults were identified, contacted and interviewed via the telephone for eligibility, and then screened for physical frailty in their homes (Gill, McGloin, Gahbauer, Shepard, & Bianco, 2001).

An emerging strategy to foster participation of older adults in research is the use of community involvement in the recruitment and research process, which allows the community and its leaders to have a voice in the overall research and intervention methods (Coleman et al., 1997; Gorelick et al., 1996). This approach helps to facilitate recruitment success by developing collaborative and working relationships between researchers and community members to achieve consensus on goals and objectives (Levkoff, Levy, & Weitzman, 2000; Sinclair et al., 2000). The importance of partnerships between researchers and communities, with community participation contributing to the success of research and health promotion programs, has been well described (Gorelick et al., 1996; Levine, Becker, & Bone, 1992). Reed and colleagues (2003) describe a process of community involvement and partnership with the older African American community. A Community Research Advisory Board was developed, with the intent that members use their collective knowledge of the community to guide the scientific process, and effectively acknowledge the community’s diversity. With the guidance and support of the Community Research Advisory Board, community participation was fostered, and recruitment was successfully conducted through community churches.

Researchers attempting to recruit community-dwelling older adults have focused primarily on healthier older adults who are able to move about in the community. Homebound older adults are often frail, have one or more chronic diseases, and suffer from fatigue and pain that can prevent them from participating in research studies (Bowsher, Bramlett, Burnside, & Guelner, 1993; Harris & Dyson, 2001; Hawranik & Pangman, 2002). Further, few researchers have described the process of designing and implementing a plan to recruit these older adults for intervention research. Different strategies for recruitment may be needed to address the unique situation and concerns of homebound older adults (Shearer, 2007). To pursue research with these older adults, we incorporated a variety of approaches, implemented in partnership with a Community Action Agency serving homebound older adults. This partnership was essential in fostering community input into the research methods, as well as recognized contributions from all interested parties.

Recruitment Procedures

An essential aspect of developing recruitment procedures included acknowledging the need for trust among homebound older adults, who may fear for their safety, have limited understanding of the research process, or be disadvantaged by illness and frailty. Thus, an initial step in framing recruitment included endorsement from community leaders, characterized by a partnership with a local Community Action Agency that had spanned more than 10 years. The Community Action Agency, a major social service agency located in a southwestern metropolitan city, assists low-income individuals and families of every age group. It has been suggested that such partnerships may reduce the disparity in power between investigator and participant and improve the pertinence and design of research, with anticipated improvement in recruitment procedures and increased numbers of people willing to participate (Harris & Dyson; 2001; Porter & Lanes, 2000).

At the suggestion of Community Action Agency leaders, the home-delivered meal program was chosen as the vehicle for recruitment of homebound older adults, as this program is a primary point of contact for these older adults. Further, the home-delivered meal program provides approximately 400 meals to homebound adults living in its service area around the agency’s headquarters, fostering access for recruitment. Our work with the Community Action Agency and previous work with homebound older women guided our understanding of the unique role of the home-delivered meal driver as a trusted source of community access (Shearer, 2007). For many homebound older adults, the drivers were the only regular contact they had with the outside world, and the drivers were often a trusted contact and source for help. With the support of the Community Action Agency, we met with the home-delivered meal drivers, to talk about their role and how the needs of homebound older adults might best be addressed during recruitment. The drivers voiced their support for the HEI program and, based on their in-depth knowledge of these older adults and their community, outlined strategies for recruitment.

In designing our recruitment strategies with the Community Action Agency, we followed recommendations stated by Locher and colleagues (2006) regarding ethical issues involving research conducted with homebound older adults. The study team developed a close relationship with both Agency directors and home-delivered meal drivers, those with direct contact with homebound older adults, who would be presenting initial study information. This relationship included regular face-to-face interaction, to ensure that drivers understood the study, in order to convey information accurately to potential participants.

The drivers used face-to-face contact in their role as trusted service provider by distributing flyers describing the study to homebound older adults. The flyers described the HEI, inclusion criteria, and provided the research office telephone number. Providing this initial information is consistent with the need to orient or prepare older adults to receive information from the researcher prior to more formal explanation of the research (Tymchuk & Ouslander, 1990). Approximately one week later, study team members accompanied the drivers on their delivery route; drivers made introductions among team members and the older adult to facilitate personal contact and trust in recruitment. Our approach acknowledged respect for individual autonomy, and emphasized the right of the older adult to make an informed choice about participation in the research. Care was taken to limit coercion in recruitment, particularly given the potential for perceived role conflict on the part of the home-delivered meal driver serving in the roles of service provider and research partner (Locher et al., 2006). Home-delivered meal drivers were very clear that their first priority was the well-being of the older adults; this was communicated to the older adults at each contact. Given the role of the home-delivered meal driver as a trusted contact, older adults felt comfortable both in declining to participate, as well as inviting the PI into their home to learn more about the study.

Enrollment Procedures

In order to eliminate a common barrier to participation in research among older adults, namely, concerns about home safety and inviting a stranger into their home, the research team recognized that strategies for enrollment might best be individualized to meet the needs of each potential participant (Table 1). Once an older adult expressed an interest in learning more about the study, the PI made an appointment to meet with them at their convenience, to return to explain the study in more detail. When arriving for the face-to-face meeting, the PI re-introduced herself at the doorway and reminded the older adult why she was there. After the older adult invited the PI into their home, the PI and older adult were seated in a location as directed by the potential participant. The PI then took the opportunity to share general information in an unrushed manner regarding her role as a nurse and a nurse researcher. The face-to-face unrushed meeting allowed the older adult time to share some of their life story; building trust between the PI and older adult. In addition to the information provided regarding the PI and study, a flyer with pictures of the research team and introductory paragraphs about the PI, nurse intervener (NI), and the data collector were shared. This introductory information was provided as a strategy to alleviate the fear of strangers coming to their door and into their home, as well as provided further building of trust between the research team and the older adults.

Table 1.

Recruitment and Enrollment of Homebound Older Adults in Research

| Issues | Solutions |

|---|---|

| Trust |

|

| Limited Understanding of Research Process |

|

| Safety |

|

| Frailty |

|

Strategies for building trust in relationship to the potential limited understanding of the research process included development of rapport, assessment of understanding, a clear explanation of the study, and participant decision-making (Harris & Dyson, 2001). Short, clear, explanations were offered, including an overview of the purpose of the study. The potential participant was frequently asked if they had any questions about the study or their involvement. As the PI spoke, the sharing of stories and experiences regarding their health was often shared; rapport was established as the PI listened to and learned about each participant. If the older adult expressed that they would feel more comfortable having a son or daughter present to hear the details of the study, a meeting was rescheduled at the convenience of the potential participant and their family member.

A primary strategy for addressing the frailty of homebound older adults during enrollment in the study was to clearly communicate what was expected of them if they were eligible and agreed to participate in the study. For example, the commitment of time was emphasized, as all participants would have three one-hour visits from a research team member, to complete a questionnaire packet. In addition to the minimum of three hours, participants in the HEI would have an approximately one hour long visit each week for six weeks. In order to minimize participant burden, the research team encouraged older adults to schedule appointments at a time and location that was convenient to them. Contact information for study team members were given to each potential participant, in the event that they needed to cancel or reschedule an appointment. Before returning for the first scheduled visit, a telephone call was made as a reminder, and to give the participant an option to reschedule if they were not feeling up to the visit. Reminders also served to address any concerns about home safety related to unannounced visitors. In addition, before beginning the recruitment visit, the potential participant was told how long the visit should take and that they could stop the session at any time.

Documents printed in small font may be difficult for visually impaired older adults to read. In order to alleviate this concern, the consent form was written in larger font and divided into sections in order to make it easier for the older adult to follow as the PI read the consent form aloud. Terms or phrases were used to enhance understanding of certain terms; for example, “random assignment” included an explanation of randomization as flipping a coin. While reading the consent form, if reference was made to a team member, the older adult was shown the photo flyer of the research team and the role of each team member in the study. Throughout the consent process and in the written consent form, participation was stressed as being voluntary; explained as being able to choose to not participate in any part of the study or choosing to stop participating in the study at any time. After each section of the form the potential participant was asked if they had any questions and if they wanted to continue. While signing the consent form, many participants stated that they had decided to participate in the study as they hoped the findings of the study would help other older adults. At the end of the enrollment session, the PI again reminded the potential participant that even though they had signed the consent form, their participation was their decision and they could stop at any time. At the conclusion of the face-to-face meeting, hard copies of consent form, photo flyer, and the PI’s business card with phone number were left with the homebound older adult to review and/or share with family members; a strategy viewed as a way to continue the establishment of trust.

Evaluating the Recruitment Process

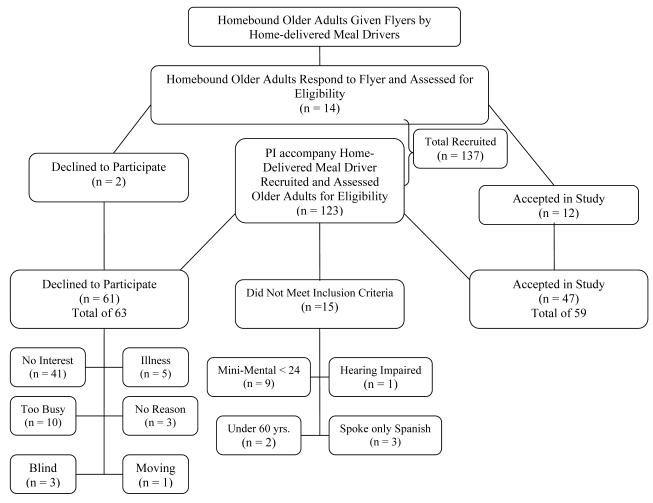

The study team accompanied the home-delivered meal drivers and introduced the study to a total of 137 homebound older adults. Of the 137 older adults, 15 (11%) did not meet eligibility criteria. Of the remaining 122 older adults, 63 (46%) declined to participate; 4 dropped out of the study before the first scheduled data collection. Fifty-nine (43%) were successfully recruited into the study. Of those enrolled, the majority were women (n = 42), aged 75 years and older (n = 38), and white, non-Hispanic (n = 55). Fourteen homebound older adults directly contacted the study office in response to the initial information flyer left by the home-delivered meal drivers; all met eligibility criteria and 12 agreed to participate in the study. Refer to Figure 1 for recruitment flow.

Figure 1.

Recruitment Flow Chart

Our refusal rate is similar to other studies of frail and homebound older adults (Harris & Dyson, 2001; Ritchie & Dennis, 1999; Taylor-Davis et al., 1998). However, the use of innovative strategies and development of community partnerships furthered our understanding of sustainable resources for reaching homebound older adults, and the implications of these resources for translation to practice. A primary goal was to recruit homebound older adults in a way that was acceptable to them; thus, success in recruitment might be evaluated in terms of those older adults who felt safe in speaking with the study team and clearly understood the study as explained, rather than only those who chose to participate (Harris & Dyson, 2001).

Partnership with community leaders through the Community Action Agency and home-delivered meal drivers strengthened trust between the homebound older adults and research team. Further, this partnership fostered a participatory approach to the development and implementation of recruitment methods, best meeting the needs of homebound older adults from the perspective of those who cared for them. Several authors have suggested that an effective recruitment strategy includes personal contact with an older adult in their home, and an introduction of the researcher by a familiar and trusted person (Bowsher, Bramlett, Burnside, & Gueldner, 1993; Gueldner & Hanner, 1989). The role of the home-delivered meal driver as a trusted source of community access to facilitate recruitment was significant. In this study, home-delivered meal drivers may have functioned as intermediaries in recruitment, those both supportive of the project goals and acquainted with older persons living in the community (Porter & Lanes, 2000). Intermediaries including Meals on Wheels affiliates were noted as effective in recruiting homebound older adults in a qualitative study which included homebound older women (Porter & Lanes, 2000).

The research team eliminated a common barrier to participation, namely, concerns about home safety and inviting a stranger into their home, by meeting face-to-face and distributing a photo flyer and an introduction to the research team during the enrollment process. Referring to the photo flyer and the names of team members helped to familiarize the older adults with the research team prior to their meeting.

Conclusion

Developing a relevant recruitment plan responsive to the unique needs of the population is critical to the success of a research study. In our study, the trust and partnership that existed between the research team and Community Action Agency facilitated the role of the home-delivered meal drivers as a trusted and untapped resource for study recruitment. The support of the home-delivered meal staff, along with the face-to-face recruitment to diminish fear and build trust, addressing issues specific to frailty, and the need to clearly understand the research process fostered participant recruitment in this study. Researchers can benefit from thinking creatively and developing meaningful partnerships when conducting research with older adults, particularly those who are underserved, isolated from traditional resources, and who do not frequent the usual venues from which research participants are drawn.

Despite innovative and individualized recruitment and enrollment strategies, our study refusal rate was similar to other studies with older adults. Future research in this population may be enhanced through greater intensity in meeting with home delivered meal drivers as an essential point of contact with older adults. While the PI had regular face-to-face interaction with the home-delivered meal drivers, perhaps more frequent meetings would have helped in the recruitment of newly enrolled home-delivered meal clients. For example, occasionally when the PI and NI accompanied the home-delivered meal driver to the home of a new client on the route, the older adult stated that they had not received a study flyer and was not interested in hearing more about the study. Upon further questioning, it became apparent that the home-delivered meal driver had forgotten to give the new client a study flyer. More frequent meetings with the home-delivered meal drivers may have reinforced their understanding of the study, the importance of distributing the flyers, and the valued role they played in the recruitment process.

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Nursing Research: R15 NR009225-01A2

Contributor Information

Nelma B. Crawford Shearer, Associate Professor and Co-Director Hartford Center of Geriatric Nursing Excellence College of Nursing & Healthcare Innovation Arizona State University Phoenix, AZ.

Julie D. Fleury, Hanner Professor Associate Dean for Research Director, PhD Program College of Nursing & Healthcare Innovation Arizona State University.

Michael Belyea, Research Professor College of Nursing & Healthcare Innovation Arizona State University.

References

- Adams J, Silverman M, Musa D, Peele P. Recruiting older adults for clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1997;18:14–26. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(96)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Administration on Aging. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . A profile of older Americans: 2007. Author; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Austin-Wells V, McDougal GJ, Becker H. Recruiting and retaining an ethnically diverse sample of older adults in a longitudinal intervention study. Educational Gerontology. 2006;32:159–170. doi: 10.1080/03601270500388190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowsher J, Bramlett M, Burnside IM, Gueldner SH. Methodological considerations in the study of frail elderly people. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1993;18:873–879. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18060873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman EA, Tyll L, LaCroix AZ, Allen C, Leveille SG, Wallace JI, et al. Recruiting African-American older adults for a community-based health promotion intervention: Which strategies are effective? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1997;13(6 Sup):51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby F, Ventura MR, Finnick M, Lohr G, Feldman MJ. Enhancing subject recruitment for nursing. Clinical Nurse Specialist. 1991;5(1):25–30. doi: 10.1097/00002800-199100510-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibartolo M, McCrone S. Recruitment of rural community-dwelling older adults: Barriers, challenges, and strategies. Aging & Mental Health. 2003;7(2):75–82. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000072295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer T. Recruiting older adults in our studies. Applied Nursing Research. 2001;14(2):63. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2001.24332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill TM, McGloin JM, Gahbauer, Shepard DM, Bianco LM. Two recruitment strategies for a clinical trial of physically frail community-living older persons. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2001;49(8):1039–1045. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Burgh D, Dodson C, Freda N. Strategies to recruit older adults for participation in rehabilitation research. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 1995;11(1):10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez EW, Gardner EM, Murasko D. Recruitment and retention of older adults in influenza immunization study. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2007;14(2):81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick PB, Richardson D, Hudson E, Perry C, Robinson D, Brown N, et al. Establishing a community network for recruitment of African Americans into a clinical trial. The African-American antiplatelet stroke Prevention Study (AAASPS) experience. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1996;88(11):701–704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grap MJ, Munro CL. Subject recruitment in critical care nursing research: A complex task in a complex environment. Heart & Lung. 2003;32(3):162–168. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(03)00031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueldner SH, Hanner MB. Methodological issues related to gerontological nursing research. Nursing Research. 1989;38:183–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R, Dyson E. Recruitment of frail older people to research: lessons learnt through experience. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;36(5):643–651. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawranik P, Pangman V. Recruitment of community-dwelling odler adults for nursing research: A challenging process. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;33(4):171–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jancey J, Howat P, Lee A, Clarke A, Shilton T, Fisher J, et al. Effective recruitment and retention of older adults in physical activity research: PALS study. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2006;30:626–635. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2006.30.6.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katula JA, Kritchevsky SB, Guuralnik JM, Glynn NW, Pruitt L, Wallace K, et al. Lifestyle interventions and independence for elders pilot study: Recruitment and baseline characteristics. American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:674–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkoff SE, Levy BR, Weitzman PF. The matching model of recruitment. In: Levkoff SE, Prohaska TR, Weitzman PF, Ory MG, editors. Recruitment and retention of minority populations. Springer; New York: 2000. pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Levine DM, Becker DM, Bone LR. Narrowing the gap in health status of minority populations: a community-academic medical center partnership. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1992;8(5):319–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locher JL, Bronstein J, Robinson CO, Williams C, Ritchie CS. Ethical issues involving research conducted with homebound older adults. The Gerontologist. 2006;46:160–164. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.2.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter EJ, Lanes TI. Targeting intermediaries to recruit older women for qualitative, longitudinal research. Journal of Women & Aging. 2000;12(12):63–75. doi: 10.1300/J074v12n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed PS, Foley KL, Hatch J, Mutran EJ. Recruitment of older African Americans for survey research: A process evaluation of community and church-based strategy in the Durham Elders Project. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:52–61. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B, Concha B, Burgess JG, Fine ML, West L, Baylor K, et al. Recruitment of older women. Nursing Research. 2003;52(4):269–273. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie CS, Dennis CS. Research challenges to recruitment and retention in a study of homebound older adults: Lessons learned from the Nutrition and Dental Screening Program. The Case Management Journals. 1999;1:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saddler GR, York C, Madlensky L, Gibson K, Wasserman L, Rosenthal E, et al. Health parties for African American study recruitment. Journal of Cancer Education. 2006;21(2):71–76. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2102_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz CH, Wasserman J, Ostwald SK. Recruitment and retention of stroke survivors: The CAReS experience. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2006;25(1):17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer NBC. Toward a nursing theory of health empowerment in homebound older women. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2007;33(12):38–45. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20071201-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer NBC, Fleury J. Social support promoting health in older women. Journal of Women & Aging. 2006;18(4):3–17. doi: 10.1300/J074v18n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S, Hayes-Reams P, Meyers HF, Allen W, Hawes-Dawson J, Kington R. Recruiting African Americans for health studies: Lessons from the Drew-RAND Center on Health and Aging. In: Levkoff SE, Prohaska TR, Weitzman PF, Ory MG, editors. Recruitment and retention of minority populations. Springer; New York: 2000. pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Davis S, Smiciklas-Wright H, Davis AC, Jensen GL, Mitchell DC. Time and cost for recruiting older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1998;46(6):753–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb03812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tymchuk AJ, Ouslander JG. Optimizing the informed consent process with elderly people. Educational Gerontology. 1990;16(3):245–257. doi: 10.1080/0380127900160302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]