Abstract

Femoral neck (FN) bone geometry is an important predictor of bone strength with high heritability. Previous studies have revealed certain candidate genes for FN bone geometry. However, the majority of the underlying genetic factors remain to be discovered. In this study, pathway-based genome-wide association analysis was performed to explore the joint effects of genes within biological pathways on FN bone geometry variations in a cohort of 1,000 unrelated U.S. whites. Nominal significant associations (nominal p value < 0.05) were observed between 76 pathways and a key FN bone geometry variable - section modulus (Z), biomechanically indicative of bone strength subject to bending. Among them, EphrinA-EphR pathway was most significantly associated with FN Z even after multiple testing adjustments (pFWER value = 0.035). The association of EphrinA-EphR pathway with FN Z was also observed in an independent sample from Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Overall, these results suggest the significant genetic contribution of EphrinA-EphR pathway to femoral neck bone geometry.

Keywords: Bone strength, Femoral neck bone geometry, Genetic factor, Pathway-based genome-wide association analysis, EphrinA-EphR pathway

INTRODUCTION

Hip fracture occurs when the load applied to hip bone exceeds its mechanical strength. The mortality and morbidity associated with hip fracture become an ever-increasing threat to the public health [1]. Femoral neck (FN) bone geometry, an important predictor of bone strength, is under strong genetic control with heritability ranging from 30–70% [2;3]. To date, some studies have been carried out to identify the genetic basis of FN bone geometry, with certain progresses being made [4–6]. However, the majority of FN bone geometry candidate genes are still largely unknown, leaving a considerable gap in knowledge.

Recently, a pathway-based approach was proposed to further interpret genome-wide association (GWA) data at the level of gene sets [7]. Generally speaking, it is a pathway-driven gene set enrichment analysis, which focuses on groups of genes [i.e. genes sharing a biochemical or cellular function, chromosomal location or regulation, or Gene Ontology (GO) category] that make modest contributions to disease risk, rather than a few single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and/or genes with strong evidence of association. The method starts with gene ranking based on its degree of association with the studied phenotype to generate a gene list, then uses a statistic enrichment score (ES) to determine whether members of a given gene set tend to be concentrated at the top (or bottom) of the list, i.e. the gene set is related to the phenotype. The significance of ES is assessed by comparing it with the set of score obtained by 1,000 re-sampling runs, adjusting for variation in gene size and controlling for family-wise error rate (FWER). Through application to two Parkinson diseases (PD) and one amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (AMD) GWA data sets, this approach was proven to be powerful in the exploration of disease-susceptibility mechanism [7].

To identify the potential pathway underlying FN bone geometry variation, we employed this approach to analyze the GWA data from a cohort of 1,000 unrelated U.S. whites. We detected an interesting pathway for FN bone geometry – EphrinA-EphR signaling pathway, whose significant relevance to FN bone geometry was verified in an independent sample from Framingham Osteoporosis Study and some of whose gene components have been known to be important for bone. Our findings have important implications regarding the genetic regulation of bone strength and the pathogenesis of hip fracture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and phenotypes

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Missouri – Kansas City. Signed informed-consent documents were obtained from all study participants before they entered the study. The basic characteristics of the study subjects are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the subjects

| U.S. whites | Framingham sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Male (n = 501) | Female (n = 496) | Male (n = 469) | Female (n = 679) |

| Age (years) | 50.31 (18.87) | 50.20 (17.70) | 68.79 (9.91) | 68.54 (11.58) |

| Height (m) | 1.78 (0.07) | 1.64 (0.07) | 1.73 (0.07) | 1.59 (0.07) |

| Weight (kg) | 89.02 (14.94) | 71.28 (15.92) | 84.60 (15.28) | 67.72 (14.01) |

| Z (cm3) | 2.27 (0.54) | 1.49 (0.31) | 1.82 (0.44) | 1.24 (0.39) |

| CSA (cm2) | 3.20 (0.60) | 2.48 (0.45) | 2.70 (0.47) | 2.09 (0.48) |

| CT (cm) | 0.16 (0.03) | 0.15 (0.03) | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.12 (0.03) |

| BR | 12.42 (2.69) | 11.61 (2.74) | 15.38 (3.60) | 15.09 (4.28) |

Note: Data presented are unadjusted means (SD).

U.S. whites

Based on our established and expanding genetic repertoire with more than 6,000 subjects, a total of 1,000 unrelated healthy U.S. whites were selected for this study. They were normal healthy subjects defined by a comprehensive suite of exclusion criteria [8]. Briefly, efforts were made to exclude subjects with chronic diseases and conditions that might potentially affect bone metabolism so as to increase the statistical power for detecting bone candidate genes.

Areal bone mineral density (BMD, g/cm2) and bone size (cm2) of FN were measured by using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) machines (Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA, USA). The machines were calibrated daily. The coefficient of variation (CV) values of the DXA measurements for FN BMD and bone size were 1.87% and 1.97%, respectively. On the basis of FN BMD and FN bone size, hip structural or hip strength analysis (HSA) was applied to estimate four parameters, which are generally used to describe bone strength in the proximal femur. They are section modulus (Z, in cm3), an index of bone bending strength; cross-sectional area (CSA, in cm2), an indicator of bone axial compression strength; cortical thickness (CT, in cm), an estimate of mean cortical thickness; and buckling ratio (BR), an index of bone structural instability. Briefly, the method assumes that: 1) the cross-section of bone within the femoral neck region is a right circular annulus; 2) 60% of the measured bone mass is cortical; 3) the effective BMD in fully mineralized bone tissue is 1.05 g/cm3. All of these assumptions were substantiated as good approximations [9]. The formulas used to calculate the five parameters are presented below.

where W is the FN periosteal diameter and can be approximated by dividing FN bone size by the width of the region of interest (in Hologic DXA systems, the width of the FN region is standardized at 1.5cm [10]);

, where the ED (Endocortical diameter) is calculated by the formula

where the CSMI (Cross-sectional moment inertia) is calculated by the formula , p as trabecular porosity is calculated by the formula . Details of the phenotype definitions were previous reported [4;11].

Framingham sample

A set of 1,151 unrelated Framingham subjects were chosen from Framingham Osteoporosis study [12]. The participants underwent bone densitometry by DXA with a Lunar DPX-L (Lunar Corp., Madison, WI, USA). Femoral geometry parameters was assessed noninvasively by DXA-based HSA [11;13]. The region assessed was the narrowest width of the femoral neck (NN), which overlaps or is proximal to the standard femoral neck region. FN CSA, and FN Z were measured directly from the mass profiles using a principle first described by Martin and Burr [14]. The CV values for the different variables were previously reported to range from 7.9% (CSA) to 10.4% (BR). Detail descriptions could be found in the corresponding previous reports [12;15].

Genotyping

U.S. whites

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole human blood using a commercial isolation kit (Gentra systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) following the protocols detailed in the kit. DNA concentration was assessed by a DU530 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc, Fullerton, CA, USA). Before advancing to the hybridization step, the measurements of DNA concentration were double-checked by pico-green analysis that can detect fluorescent signal enhancement of PicoGreen® dsDNA Quantitation Reagent, which selectively binds to dsDNA [16;17]. Genotyping with Affymetrix mapping 500K array (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) was performed at the Vanderbilt Microarray Shared Resource at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN using the standard protocol recommended by the manufacturer (see detailed description in [8]). Genotyping calls were determined with the dynamic model (DM) algorithm [18] as well as with the B-RLMM (Bayesian Robust Linear Model with Mahalanobis Distance Classifier) algorithm, an extention of the RLMM (Robust Linear Model with Mahalanobis Distance Classifier) [19] developed for the Mapping 500K product. DM calls were used for quality control of the genotyping experiment, and unsatisfactory arrays were subjected to re-genotyping. Eventually, 997 subjects (501 males and 496 females) who had at least one array (Nsp or Sty) reaching 93% call rate were retained. BRLMM calls were used for the following pathway-based GWA analyses, where only autosomal SNPs with per-SNP call rates (i.e. call rate for each SNP across all samples) > 95%, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) p values >= 0.001, minor allele frequencies (MAF) >= 5% and the physical distances from genes < 500 kb were evaluated. The distance setting was from the consideration that most enhancers and repressors are < 500 kb away from genes and most LD blocks are < 500 kb.

Framingham sample

Genotype (Affymetrix 500K mapping array plus Affymetrix 50K supplemental array) and phenotype information were downloaded from the dbGaP database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=gap). Data download and usage was authorized by the SHARe data-access committee. Only individuals (469 males and 679 females) with genotypic call rates > 93% and SNPs on a given pathway/gene set with per-SNP call rates > 95%, HWE p value >= 0.001 and MAF >= 5% were included in the following association study.

Pathway/gene sets database construction

We retrieved 260,190 and 380 annotated human pathways from BioCarta pathway database (http://www.biocarta.com/genes), KEGG pathway database (http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg/pathway.html) and Ambion GeneAssist™ Pathway Atlas (http://www.ambion.com/tools/pathway), respectively. In addition, we downloaded GO annotation files for human genes from the GO website (http://www.geneontology.org) to integrate the GO information into our study. Gene sets were obtained from Level 4 Biological Process and Molecular Function GO terms. Genes whose GO annotations were in level 5 or lower in the GO hierarchy were assigned to their ancestral GO annotations in level 4. In our analysis, we tested only those pathways/gene sets with 10–200 genes included in our GWA data set so as to alleviate the multiple-testing problem by avoiding testing too narrowly- or too broadly- defined functional categories. Overall, 963 pathways/gene sets were constructed by 14,585 genes/312,172 SNPs.

Routine statistical analysis

For raw FN bone geometry in both the U.S. whites and the Framingham sample, we tested their correlations with parameters like age, age2, sex, age/age2-by-sex interactions, height and weight. After adjustments for significant (p value < 0.05) terms (age, age2, sex, height and weight) in each sample, the phenotype data, if not following normal distribution, were further subjected to Box-Cox transformation. General association analyses on individual SNPs were conducted by the Wald test implemented in PLINK (version 1.03) to obtain a t-statistic for each tested SNP.

Pathway-based GWA analysis in the U.S. whites

The main procedures of pathway-based GWA analysis [7] were briefly summarized as follows:

Generation of gene-phenotype association rank: For x SNPs mapped to gene Gi (i = 1,…, N where N is the total number of genes with genotype data available in our GWA study), let ri denote the absolute value of highest SNP-phenotype association statistic. The ri was also assigned to represent the statistic value of gene-phenotype association for gene Gi. A gene list L (r1,r2,,…, rN) was generated by sorting all ri from the largest to the smallest. Mostly, SNPs were mapped to their closest genes. And in rare cases, if a SNP is located within shared regions of two overlapping genes, the SNP was mapped to both genes.

Calculation of ES: For given pathway/gene set S, composed of NS genes, ESS was used to reflect the overrepresentation of S at the top of the entire ranked gene list L. ESS was determined based on a weighted Kolmogorov-Smirnov like running-sum statistic:

| (1) |

where . From Formula (1), it is clear that ESS is calculated by walking down the list L, increasing a running-sum statistic when we encounter a gene in S and decreasing it when we encounter genes not in S. The magnitude of the increment depends on the correlation of the gene with the phenotype. In short, ESS is the maximum deviation from zero encountered in the random walk. It will be high if the association signal is concentrated at the top of list L, reflected by the significance level of observed ESS (i.e. nominal p value).

-

3.

Permutation and nominal significance assessment: The phenotype data was shuffled and permutation (per) was done to compute a through repeating steps (1) ~ (2) to estimate the nominal p value. A total of 1,000 permutations were done to create a histogram of the corresponding enrichment scores for the given pathway/gene set S. The nominal p value was estimated as the percentage of permutations whose were greater than the observed ESS.

-

4.

Multiple testing adjustments: In order to correct the effects of gene size, for each pathway/gene set S, we calculated the normalized ESS in the observed data and the normalized in all permutations. The calculation of normalized ESS (NESS) relied on ESS, mean and standard deviation (SD) of in all permutations for the given pathway/gene set S:

| (2) |

Then, in the context of multiple testing, FWER p value (denoted as pFWER) was calculated through a highly conservative procedure, which sought to ensure that the reported results did not include even a single false positive gene set [7;20]. The pFWER can be calculated as the fraction of all gene sets whose greatest in all permutations was higher than the NESS in the given pathway/gene set S.

Validation analyses in Framingham samples

For a certain interesting pathway, we performed multiple step-wise regressions using SAS 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), to verify the associations of pathway genes with FN Z in Framingham samples, while adjusting for significant covariates (p < 0.05). At first, raw bone geometry value was adjusted through the same procedure, described above, for the U.S. whites. Then, association analyses for all the SNPs in certain interesting pathway were performed using the PLINK software package (version 1.02). In the multiple step-wise regression analysis, each pathway gene was represented by its top significant SNP as independent variable. P value of 0.05 was set as the criteria for the entry and removal of predictive variables. F test was used to assess the significance of the overall model. R-square value as an indicator of how well the model fits the data (e.g., an R-square close to 1.0 indicates that we have accounted for almost all of the variability with the variables specified in the model) was used to evaluate the additive contributions of pathway genes to the trait.

Other analyses

For our U.S. White sample, pathway-based GWA analyses were also conducted for FN BMD in the total population and for FN Z in the sex-specific groups through the same procedure described in the above sub-sections of “Routine statistical analysis” and “Pathway-based GWA analysis in the U.S. whites”. In addition, to detect potential population stratification, which may lead to spurious association results, we used the software Structure 2.2 (http://pritch.bsd.uchicago.edu/software.html) to investigate the potential substructures of the U.S. whites sample and the Framingham sample. The program uses a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm to cluster individuals into different cryptic sub-populations on the basis of multi-locus genotype data [21]. To ensure the robustness of our results, we performed independent analyses under three assumed numbers for population strata (k = 2, 3, and 4), using 200 un-linked markers that were randomly selected across the entire genome. To confirm the results achieved through Structure 2.2, we further calculated inflation factors based on median chi-square statistic using a method of genomic control [22].

RESULTS

Pathway-based association analysis

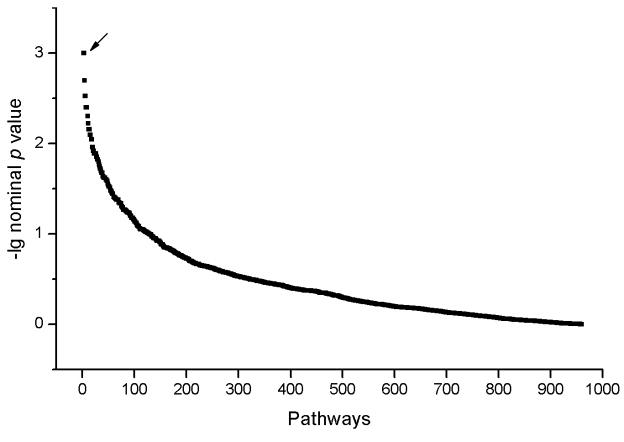

In the pathway-based association analysis for FN Z in the total U.S. whites, 76 out of the 963 tested pathways showed significant association at the nominal significance level (p value < 0.05). Among them, two pathways were significant with pFWER less than 0.05. One was 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway retrieved from KEGG database (pFWER value = 0.021) and the other was EphrinA-Eph receptors (EphR) signaling pathway queried from Ambion database (pFWER value = 0.035) (Figure 1). For the other three tested bone geometric measures (CSA, CT and BR), no significant result was found after multiple testing adjustments, consequently, no further analyses were done for them.

Figure 1.

Pathway-based genome-wide association results for FN Z in the total U.S. whites Note: Arrow points to the pathways associated with nominal p value < 0.001, including the 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway and the EphrinA-EphR pathway.

In the sex-specific pathway-based GWA analysis for FN Z, we found the EphrinA-EphR pathway was significant in the male subgroup with a nominal p value of 0.006, while the 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway was associated with FN Z in the female subgroup at a level of marginal significance (nominal p value = 0.056). However, these two correlations did not remain significant after adjusting for multiple tests. Furthermore, pathway-based GWA analysis showed that these two pathways were not associated with FN BMD (data not shown). In Table 2, basic information about the top 18 pathways associated with –lg(p)value > 2 in the pathway-based GWA analysis for FN Z in the total U.S. whites are summarized, including source database, database entry, pathway name, and association results in the total population as well as in the sex-specific groups.

Table 2.

Basic information for the top 18 pathways in the pathway-based GWA analysis for FN Z in the total U.S. whites

| Entry | Pathway name | Source | Total | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hsa00624 | 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation | KEGG | < 0.001 | - | 0.056 |

| Amb121 | EphrinA-EphR Signaling | Ambion | < 0.001 | 0.006 | - |

| GO:0051051 | Negative regulation of transport | GO | < 0.001 | - | - |

| Hsa01031 | Glycan structures - biosynthesis 2 | KEGG | 0.002 | 0.035 | - |

| StemPathway | Regulation of hematopoiesis by cytokines | BioCarta | 0.003 | - | - |

| cdc42racPathway | Role of PI3K subunit p85 in regulation of Actin Organization and Cell Migration | BioCarta | 0.003 | 0.011 | - |

| GO:0030097 | Hemopoiesis | GO | 0.004 | - | 0.081 |

| Hsa00960 | Alkaloid biosynthesis II | KEGG | 0.004 | 0.002 | - |

| Hsa04810 | Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | KEGG | 0.004 | - | - |

| GO:0016776 | Phosphotransferase activity, phosphate group as acceptor | GO | 0.005 | - | - |

| Amb1 | 14-3-3 and Cell Cycle Regulation | Ambion | 0.006 | - | - |

| GO:0016616 | Oxidoreductase activity, acting on the CH-OH group of donors, NAD or NADP as acceptor | GO | 0.007 | 0.004 | - |

| GO:0008285 | Negative regulation of cell proliferation | GO | 0.007 | 0.069 | 0.088 |

| Amb285 | PDGF Pathway | Ambion | 0.007 | 0.053 | - |

| Edg1Pathway | Phospholipids as signalling intermediaries | BioCarta | 0.008 | - | - |

| GO:0016799 | Hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing N-glycosyl compounds | GO | 0.008 | 0.004 | - |

| Amb265 | Oct4 in Mammalian ESC Pluripotency | Ambion | 0.009 | - | - |

| Hsa00350 | Tyrosine metabolism | KEGG | 0.009 | 0.061 | - |

Note: All: association results for FN Z in the total sample; Male, Female: association results for FN Z in the male and female subgroups, respectively. “-” denotes nominal p value > 0.01.

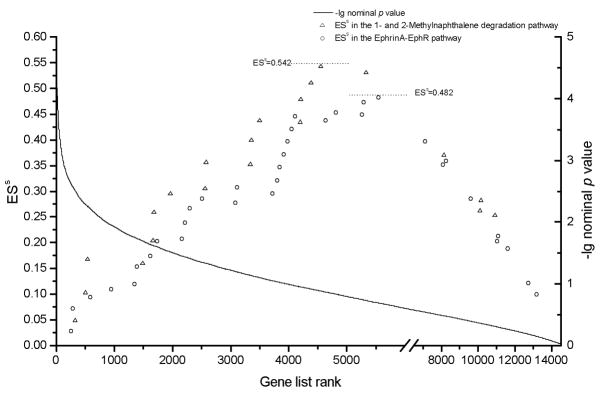

1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway and EphrinA-EphR pathway are composed of 25 genes and 40 genes, respectively. Most of their pathway genes are covered by our genotype platform. Tables 3 and 4 individually list the information of SNPs representing the 21 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway genes, and the 35 EphrinA-EphR pathway genes. A total of 15 genes in the 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway and 21 genes in the EphrinA-EphR pathway were associated with FN Z at the nominal significance level (p value < 0.05). The most significant SNP in PAK gene, rs2105803, achieved a p value of 0.001 for FN Z. Figure 2 depicts running-sum plots for the two pathways (“Gene list rank” versus “ESs”) and a plot for –lg(p)values of all the 14,585 pathway genes (“Gene list rank” versus “-lg nominal p value”) to describe the results of pathway-based GWA analysis for FN Z in the total U.S. whites sample. We observed that most of these two pathway genes were ranked at the top significance level among the 14,585 gene lists. Accordingly, the 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway and EphrinA-EphR pathway achieved high ESs of 0.542 and 0.482, respectively.

Table 3.

Genes in the 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway

| Gene | Max_SNP | Allele | MAF | Chr | Phy_loc | Role | p_max_snp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHRS2 | rs12894928 | G/T | 0.46 | 14 | 23266975 | Upstream | 0.002 |

| MYST3 | rs13270574 | C/T | 0.44 | 8 | 42121063 | Upstream | 0.003 |

| MYST4 | rs11001246 | C/T | 0.05 | 10 | 76450308 | Upstream | 0.003 |

| ADH1C | rs1229979 | C/T | 0.31 | 4 | 100474976 | Upstream | 0.011 |

| ADHFE1 | rs2465983 | C/T | 0.17 | 8 | 67526166 | Downstream | 0.012 |

| DHRS3 | rs4394668 | C/T | 0.21 | 1 | 12593816 | Downstream | 0.012 |

| ADH7 | rs1154436 | C/T | 0.29 | 4 | 100504374 | Upstream | 0.015 |

| LYCAT | rs6742360 | G/T | 0.05 | 2 | 30639989 | Upstream | 0.021 |

| NAT5 | rs6081840 | C/T | 0.43 | 20 | 19956581 | Upstream | 0.022 |

| SH3GLB1 | rs12097397 | C/G | 0.05 | 1 | 86987942 | Upstream | 0.031 |

| PNPLA3 | rs16991187 | A/C | 0.10 | 22 | 42672731 | Upstream | 0.032 |

| ADH4 | rs17817958 | G/T | 0.30 | 4 | 100280268 | Upstream | 0.034 |

| ACAD8 | rs473041 | A/G | 0.34 | 11 | 133631822 | Upstream | 0.045 |

| ADH5 | rs2602891 | C/T | 0.30 | 4 | 100262307 | Upstream | 0.045 |

| ADH6 | rs6837311 | A/T | 0.39 | 4 | 100414296 | Upstream | 0.048 |

| DHRS1 | rs4568 | A/G | 0.25 | 14 | 23829849 | Downstream | - |

| ADH1A | rs17583753 | A/G | 0.15 | 4 | 100404687 | Upstream | - |

| ESCO2 | rs17057863 | C/T | 0.09 | 8 | 27700791 | Downstream | - |

| ESCO1 | rs16942790 | C/T | 0.16 | 18 | 17369129 | Downstream | - |

| DHRS7 | rs425565 | C/G | 0.14 | 14 | 59673636 | Downstream | - |

| ACAD9 | rs789254 | A/G | 0.29 | 3 | 130057283 | Downstream | - |

Note: “Max_SNP”: the most significant SNP; “MAF”: minor allele frequency in our sample; “Chr”: chromosome; “Phy_loc”: physical location; “-” denotes that p value > 0.05.

Table 4.

Genes in the EphrinA-EphR signaling pathway

| Gene | Max_SNP | Allele | MAF | Chr | Phy_loc | Role | p_max_snp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAK1 | rs2105803 | A/G | 0.21 | 11q14.1 | 76911659 | Upstream | 0.001 |

| FAK1 | rs11167023 | A/G | 0.18 | 8q24.3 | 142175410 | Upstream | 0.002 |

| EphA7 | rs6941459 | C/T | 0.44 | 6q16.1 | 94593345 | Upstream | 0.003 |

| PIK3CG | rs10953518 | A/G | 0.14 | 7q22.3 | 106187118 | Upstream | 0.006 |

| PAK7 | rs742452 | C/G | 0.23 | 20p12.2 | 9684363 | Intron | 0.009 |

| RASA1 | rs3827607 | A/G | 0.42 | 5q14.3 | 86712976 | Intron | 0.010 |

| FYN | rs2182644 | A/G | 0.09 | 6q21 | 112245575 | Intron | 0.012 |

| RAC1 | rs836472 | C/T | 0.25 | 7p22.1 | 6401429 | Intron | 0.013 |

| EFNA5 | rs17159152 | C/T | 0.27 | 5q21.3 | 106206807 | Downstream | 0.017 |

| CDC42 | rs17837965 | A/G | 0.05 | 1p36.12 | 22267212 | Intron | 0.017 |

| PTPN11 | rs7132204 | A/G | 0.39 | 12q24.13 | 111688424 | Downstream | 0.018 |

| EphA3 | rs6797260 | A/T | 0.32 | 3p11.2 | 89385176 | Intron | 0.021 |

| EphA1 | rs7800937 | A/G | 0.08 | 7q35 | 142803429 | Intron | 0.028 |

| EphA5 | rs1514271 | C/G | 0.34 | 4q13.1 | 65799362 | Downstream | 0.028 |

| EphA4 | rs17349283 | A/G | 0.46 | 2q36.1 | 221798041 | Downstream | 0.037 |

| LIMK2 | rs2267171 | C/T | 0.07 | 22q12.2 | 29979632 | Intron | 0.038 |

| ROCK2 | rs6716817 | A/G | 0.47 | 2p25.1 | 11303285 | Intron | 0.039 |

| ADAM10 | rs4775085 | A/G | 0.06 | 15q22.1 | 56737283 | Intron | 0.040 |

| CFL1 | rs3903072 | A/C | 0.48 | 11q13.1 | 65339642 | Downstream | 0.042 |

| ACTG2 | rs1721241 | C/G | 0.22 | 2p13.1 | 73981899 | Intron | 0.043 |

| EphA8 | rs12128121 | A/G | 0.10 | 1p36.12 | 22804749 | Downstream | 0.044 |

| ACTB | rs1474445 | C/T | 0.18 | 7p22.1 | 5563375 | Upstream | - |

| NGEF | rs895432 | C/T | 0.05 | 2q37.1 | 233465941 | Coding exon | - |

| FAK2 | rs2251430 | A/G | 0.14 | 8p21.2 | 27364766 | Intron | - |

| PAK2 | rs843530 | C/T | 0.46 | 3q29 | 197965421 | Intron | - |

| ACTA2 | rs1937330 | A/T | 0.08 | 10q23.31 | 90844025 | Upstream | - |

| PAK6 | rs8035733 | A/G | 0.18 | 15q15.1 | 38330232 | Intron | - |

| PAK4 | rs513053 | A/G | 0.38 | 19q13.2 | 44332986 | Intron | - |

| CFL2 | rs17453240 | C/G | 0.09 | 14q13.2 | 34248919 | 3′ near gene | - |

| ACTG1 | rs9907460 | G/T | 0.38 | 17q25.3 | 77066757 | Downstream | - |

| LIMK1 | rs2855726 | A/G | 0.33 | 7q11.23 | 73155050 | Intron | - |

| EphA2 | rs904107 | A/G | 0.05 | 1p36.13 | 16361410 | Promoter | - |

| ROCK1 | rs1552110 | A/G | 0.05 | 18q11.1 | 16924725 | Intron | - |

| EFNA3 | rs7368345 | A/G | 0.50 | 1q22 | 153346714 | Downstream | - |

| ACTA1 | rs499689 | C/T | 0.40 | 1q42.13 | 227632355 | Downstream | - |

Note: “Max_SNP”: the most significant SNP; “MAF”: minor allele frequency in our sample; “Chr”: chromosome; “Phy_loc”: physical location; “-” denotes that p value > 0.05.

Figure 2.

Association results for the whole 14,585 genes and observed ESS values for 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway and EphrinA-EphR pathway genes Note: Gene list rank: rank in association significance in the whole gene list.

Multiple step-wise regression analysis in Framingham samples

To validate our findings, we conducted multiple step-wise regression analyses for 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway and EphrinA-EphR pathway in Framingham samples. After adjustment for age, age2, sex, height and weight, 2 main-effect genes (ADH6 and ADH1A) were chosen out of 21 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway genes (p value < 0.05). They composed the final model that had an overall p value of 0.0021 and could explain 1.24% of FN Z variation. While 8 main-effect genes (EphA1-2, EphA7-8, EFNA3, PAK1, PIK3CG and LIMK2) were chosen out of the 35 EphrinA-EphR pathway genes as predictive variables (p value < 0.05). They composed the final model that had an overall p value < 0.0001 and could explain 6.06% of FN Z variation.

Potential population stratification analyses

With 200 randomly selected unlinked SNPs, all the subjects in the U.S. whites sample were consistently clustered together under all the three assumed number of population strata, so were the subjects in the Framingham sample. Moreover, the inflation factors were estimated to be 1.030 (BR), 1.009 (Z), 1.035 (CSA) and 1.071 (CT) for U.S. whites sample, and 1.022 (BR), 1.013 (Z), 1.018 (CSA) and 1.047 (CT) for the Framingham sample, suggesting no significant population substructure in the two samples.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used the genomic-wide based pathway approach to explore the joint effects of different gene variants in common pathways on FN bone geometry variations. Two pathways were identified as the most statistical promising pathways for FN Z after multiple testing adjustments, 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway and EphrinA-EphR signaling cascade.

As we known, 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene are components of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) present in cigarette smoke. A recent in vivo study showed PAHs may function as ligand for aryl-hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) a transcription factor that regulates gene expression, to cause the loss of bone mass and strength [23]. However, there has been little direct research into the effects of methylnaphthalene and its metabolites on bone and no biological correlation has been made thereof. In the present study, validation analysis in the Framingham sample demonstrated a significant but modest effect of 1- and 2-Methylnaphthalene degradation pathway genes (R-square=1.24%).

EphR and their cell-surface-bound ephrin ligands, including A- and B-subclass, constitute the largest subfamily of receptor protein-tyrosine kinases. EphrinA can activate EphA receptors and their downstream molecules (as reviewed in [24]). EphrinA-EphR pathway is known to function in reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton through Rho family GTPases. Rho family GTPases, including RhoA, Rac1 and Cdc42, have been implicated in the contraction of actin cytoskeletal systems, promoting the formation and elongation of lamellipodia and filopodia, respectively [25]. Since actin cytoskeleton including lamellipodia and filopodia are involved in the biological processes of osteoblastic adhesion and migration that are closely related to the bone geometry qualities, it is reasonable to hypothesize that EphrinA-EphR pathway may contribute to the genetic architecture underlying the variation of bone geometry.

In addition, the potential role of EphrinA-EphR pathway was revealed in the skeletal patterning (as reviewed in [26]). Several molecules such as ephrin A5 and EphA2-5 were expressed on the surface of osteoblasts or pre-osteoblasts [27–29]. Besides, the functions of EFNB2 in osteoclasts and EphB4 in osteoblasts were found to associate with the switch from bone resorption to bone formation [30]. In previous studies, crosstalks were detected between EFNB2 with both EphA3 and EphA4 [31–33], and between EphB2 and ephrinA5 [34]. These cross-talks may bridge A- and B-subclass Eph receptors/ephrins signaling, which suggested more complex regulation of EphrinA-EphR pathway in normal and pathological bone remodeling.

In this study, the pathway-based association analysis in U.S. whites demonstrated that 21 genes in this pathway were associated with FN Z at the nominal significance level (p value < 0.05). These genes included an ephrin (EPNA5) gene and 5 EphR genes (EphA1, EphA3-5 and EphA7), 2 Rho family member genes (Rac1 and cdc42) and their downstream p21-activated kinase genes (PAK1 and PAK7), 4 RhoA downstream genes (ROCK2, LIMK2, CFL1 and ACTG2), 3 adaptor molecular of EphR genes (PIK3CG, FAK1 and PTPN11), and others. Some of the identified pathway genes have been known to be important for bone, especially for osteoblasts. For example, RhoA-ROCK cascade was found to mediate the differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) to osteoblast and then promote osteogenesis, specifically via its effects on cytoskeletal tension [35]. GTPases Cdc42 and Rac were also suggested to communicate with receptor of advanced glycation end products to regulate the osteoblast motility [36]. PIK3CG, as an important modulator of extracellular signals, was found to be important for osteoblastic differentiation, recruitment, migration and survival [37–40]. In addition, activated EphA receptors can transmit signals to focal adhesion kinase (FAK), which is protein tyrosine kinase acting as a regulator of the integrin signaling cascade. This kinase was found to be important for mechanotransduction in osteoblasts [41]. Subsequent validation study confirmed our findings were by demonstrating the significant genetic effects of the same EphrinA-EphR pathway genes (EphA7, PAK1, PIK3CG and LIMK2) and the whole pathway on FN Z in the Framingham sample (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results for the multiple step-wise regression analysis for EphrinA-EphR pathway in the Framingham sample

| Intercept/Gene | Max_SNP | Parameter Estimate | Standard Error | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | - | 1.721 | 0.138 | < 0.0001 |

| EphA1 | rs12703526 | −0.007 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| PIK3CG | rs6958639 | −0.006 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| EphA2 | rs4661717 | 0.026 | 0.009 | 0.006 |

| EphA8 | rs209693 | −0.008 | 0.003 | 0.006 |

| EphA7 | rs6935730 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.011 |

| LIMK2 | rs2106294 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.021 |

| PAK1 | rs568309 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.024 |

| EFNA3 | rs7368345 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.033 |

Note: “Max_SNP” denotes the most significant SNP.

On the whole, the evidences from multiple aspects (pathway-base GWA analyses, validation analyses and functional relevance to bone) strongly supported the importance of EphrinA-EphR pathway for FN Z. Nevertheless, this pathway was associated with FN Z but not with either the other three FN bone geometry parameters or FN BMD in the total U.S. whites. Besides, in the sex-stratified analysis, this pathway was shown to be associated with FN Z only in the male subgroup at a nominal significance level. These results may reflect site-specific effect due to genetic heterogeneity at different skeletal sites and sex-specific effect only present in male subjects. On the other hand, they might also be treated with caution because of the inflated false-positive and/or false-negative rates caused by increased multiple comparisons and insufficient power in individual subgroups. In this study, efforts like permutation-based adjustments have been taken to alleviate it.

Notably, no one EphrinA-EphR pathway gene attained GWA significance (4.2×10−7) in our conventional GWA studies on FN bone geometry [42]. That is, pathway-based GWA approach may incorporate information from markers with moderate significance levels so as to detect novel genetic risk factors, which can serve as candidates for further replication studies. This approach has the merit of high-throughput in comparison with traditional candidate pathway association strategy, which may only figure out a very small fraction of the whole genetic architecture of complex diseases/traits. Besides, this approach provides an opportunity to systematically study a large number of pathways without assumptions about the causal pathways, and thus may have the higher power to identify new candidate genetic factors. However, a potential limitation of this study is that some of pathway genes were not covered by our genotype platform. For example, the genome coverage for EphrinA-EphR pathway was only 87.5%.

In summary, our results suggested that the polymorphisms in EphrinA-EphR pathway genes may affect FN bone geometry variations. Future molecular studies as well as validation studies with customized pathway array are necessary to further investigate this pathway in order to clarify its role in bone biology.

Acknowledgments

Investigators of this work were partially supported by grants from NIH (R01 AR050496, R21 AG027110, R01 AG026564, P50 AR055081 and R21 AA015973). The study also benefited from grants from National Science Foundation of China, Xi’an Jiaotong University, and the Ministry of Education of China. We also thank all contributors to the Framingham Heart Study. The Framingham Heart Study and the Framingham SHARe project are conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with Boston University. The Framingham SHARe data used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained through dbGaP. This manuscript was not prepared in collaboration with investigators of the Framingham Heart Study and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Framingham Heart Study, Boston University, or the NHLBI.

Abbreviations

- PAK1

p21-activated kinase 1

- FAK1

PTK2 protein tyrosine kinase 2

- EphA7

Eph receptor A7

- PIK3CG

phosphoinositide-3-kinase, catalytic, gamma

- PAK7

p21-activated kinase 7

- RASA1

RAS p21 protein activator 1

- FYN

FYN oncogene related to SRC, FGR, YES

- RAC1

ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1

- EFNA5

ephrinA5

- CDC42

cell division cycle 42

- PTPN11

protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 11

- EphA3

Eph receptor A3

- EphA1

Eph receptor A1

- EphA5

Eph receptor A5

- EphA4

Eph receptor A4

- LIMK2

LIM domain kinase 2

- ROCK2

Rho-associated, coiled-coil containing protein kinase 2

- ADAM10

ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10

- CFL1

cofilin 1 (non-muscle)

- ACTG2

actin, gamma 2, smooth muscle, enteric

- EphA8

Eph receptor A8

- ACTB

beta actin

- NGEF

neuronal guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- FAK2

PTK2B protein tyrosine kinase 2 beta

- PAK2

p21-activated kinase 2

- ACTA2

actin, alpha 2, smooth muscle, aorta

- PAK6

p21-activated kinase 6

- PAK4

p21-activated kinase 4

- CFL2

cofilin 2 (muscle)

- ACTG1

actin, gamma 1

- LIMK1

LIM domain kinase 1

- EphA2

Eph receptor A2

- ROCK1

Rho-associated, coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1

- EFNA3

ephrinA3

- ACTA1

actin, alpha 1, skeletal muscle

- EFNB2

ephrinB2

- DHRS2

dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR family) member 2

- MYST3

MYST histone acetyltransferase (monocytic leukemia) 3

- MYST4

MYST histone acetyltransferase (monocytic leukemia) 4

- ADH1C

alcohol dehydrogenase 1C (class I), gamma polypeptide

- ADHFE1

alcohol dehydrogenase, iron containing, 1

- DHRS3

dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR family) member 3

- ADH7

alcohol dehydrogenase 7 (class IV), mu or sigma polypeptide

- LYCAT

lysocardiolipin acyltransferase 1

- NAT5

N-acetyltransferase 5 (GCN5-related, putative)

- SH3GLB1

SH3-domain GRB2-like endophilin B1

- PNPLA3

patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3

- ADH4

alcohol dehydrogenase 4 (class II), pi polypeptide

- ACAD8

acyl-Coenzyme A dehydrogenase family, member 8

- ADH5

alcohol dehydrogenase 5 (class III), chi polypeptide

- ADH6

alcohol dehydrogenase 6 (class V)

- DHRS1

dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR family) member 1

- ADH1A

alcohol dehydrogenase 1A (class I), alpha polypeptide

- ESCO2

establishment of cohesion 1 homolog 2 (S. cerevisiae)

- ESCO1

establishment of cohesion 1 homolog 1 (S. cerevisiae)

- DHRS7

dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR family) member 7

- ACAD9

acyl-Coenzyme A dehydrogenase family, member 9

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haleem S, Lutchman L, Mayahi R, Grice JE, Parker MJ. Mortality following hip fracture: trends and geographical variations over the last 40 years. Injury. 2008;39:1157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen H, Long JR, Xiong DH, Liu YJ, Liu YZ, Xiao P, et al. Mapping quantitative trait loci for cross-sectional geometry at the femoral neck. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1973–82. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slemenda CW, Turner CH, Peacock M, Christian JC, Sorbel J, Hui SL, et al. The genetics of proximal femur geometry, distribution of bone mass and bone mineral density. Osteoporos Int. 1996;6:178–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01623944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong DH, Shen H, Xiao P, Guo YF, Long JR, Zhao LJ, et al. Genome-wide scan identified QTLs underlying femoral neck cross-sectional geometry that are novel studied risk factors of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:424–37. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivadeneira F, van Meurs JB, Kant J, Zillikens MC, Stolk L, Beck TJ, et al. Estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) polymorphisms in interaction with estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF1) variants influence the risk of fracture in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1443–56. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demissie S, Dupuis J, Cupples LA, Beck TJ, Kiel DP, Karasik D. Proximal hip geometry is linked to several chromosomal regions: genome-wide linkage results from the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Bone. 2007;40:743–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang K, Li M, Bucan M. Pathway-Based Approaches for Analysis of Genomewide Association Studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1278–83. doi: 10.1086/522374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu XG, Tan LJ, Lei SF, Liu YJ, Shen H, Wang L, et al. Genome-wide association and replication studies identified TRHR as an important gene for lean body mass. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:418–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan Y, Beck TJ, Wang XF, Seeman E. Structural and biomechanical basis of sexual dimorphism in femoral neck fragility has its origins in growth and aging. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1766–74. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.10.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivadeneira F, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Beck TJ, Janssen JA, Hofman A, Pols HA, et al. The influence of an insulin-like growth factor I gene promoter polymorphism on hip bone geometry and the risk of nonvertebral fracture in the elderly: the Rotterdam Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1280–90. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck T. Measuring the structural strength of bones with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry: principles, technical limitations, and future possibilities. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14 (Suppl 5):S81–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cupples LA, Arruda HT, Benjamin EJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Demissie S, DeStefano AL, et al. The Framingham Heart Study 100K SNP genome-wide association study resource: overview of 17 phenotype working group reports. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8 (Suppl 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khoo BC, Beck TJ, Qiao QH, Parakh P, Semanick L, Prince RL, et al. In vivo short-term precision of hip structure analysis variables in comparison with bone mineral density using paired dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans from multi-center clinical trials. Bone. 2005;37:112–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin RB, Burr DB. Non-invasive measurement of long bone cross-sectional moment of inertia by photon absorptiometry. J Biomech. 1984;17:195–201. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(84)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karasik D, Zhou Y, Cupples LA, Hannan MT, Kiel DP, Demissie S. Bivariate genome-wide linkage analysis of femoral bone traits and leg lean mass: Framingham study. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:710–8. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.081222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn SJ, Costa J, Emanuel JR. PicoGreen quantitation of DNA: effective evaluation of samples pre- or post-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2623–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.13.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singer VL, Jones LJ, Yue ST, Haugland RP. Characterization of PicoGreen reagent and development of a fluorescence-based solution assay for double-stranded DNA quantitation. Anal Biochem. 1997;249:228–38. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di X, Matsuzaki H, Webster TA, Hubbell E, Liu G, Dong S, et al. Dynamic model based algorithms for screening and genotyping over 100 K SNPs on oligonucleotide microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1958–963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabbee N, Speed TP. A genotype calling algorithm for affymetrix SNP arrays. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:7–12. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–59. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devlin B, Roeder K. Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics. 1999;55:997–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee LL, Lee JS, Waldman SD, Casper RF, Grynpas MD. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons present in cigarette smoke cause bone loss in an ovariectomized rat model. Bone. 2002;30:917–23. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00726-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lackmann M, Boyd AW. Eph, a protein family coming of age: more confusion, insight, or complexity? Sci Signal. 2008;1:re2. doi: 10.1126/stke.115re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279:509–14. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards CM, Mundy GR. Eph receptors and ephrin signaling pathways: a role in bone homeostasis. Int J Med Sci. 2008;5:263–72. doi: 10.7150/ijms.5.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allan EH, Hausler KD, Wei T, Gooi JH, Quinn JM, Crimeen-Irwin B, et al. EphrinB2 regulation by PTH and PTHrP revealed by molecular profiling in differentiating osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1170–81. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanabe S, Sato Y, Suzuki T, Suzuki K, Nagao T, Yamaguchi T. Gene expression profiling of human mesenchymal stem cells for identification of novel markers in early- and late-stage cell culture. J Biochem. 2008;144:399–408. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin-Rendon E, Hale SJ, Ryan D, Baban D, Forde SP, Roubelakis M, et al. Transcriptional profiling of human cord blood CD133+ and cultured bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in response to hypoxia. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1003–12. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao C, Irie N, Takada Y, Shimoda K, Miyamoto T, Nishiwaki T, et al. Bidirectional ephrinB2-EphB4 signaling controls bone homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2006;4:111–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lackmann M, Mann RJ, Kravets L, Smith FM, Bucci TA, Maxwell KF, et al. Ligand for EPH-related kinase (LERK) 7 is the preferred high affinity ligand for the HEK receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16521–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cerretti DP, Vanden BT, Nelson N, Kozlosky CJ, Reddy P, Maraskovsky E, et al. Isolation of LERK-5: a ligand of the eph-related receptor tyrosine kinases. Mol Immunol. 1995;32:1197–205. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(95)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kullander K, Klein R. Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:475–86. doi: 10.1038/nrm856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Himanen JP, Chumley MJ, Lackmann M, Li C, Barton WA, Jeffrey PD, et al. Repelling class discrimination: ephrin-A5 binds to and activates EphB2 receptor signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:501–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McBeath R, Pirone DM, Nelson CM, Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment. Dev Cell. 2004;6:483–95. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rauvala H, Huttunen HJ, Fages C, Kaksonen M, Kinnunen T, Imai S, et al. Heparin-binding proteins HB-GAM (pleiotrophin) and amphoterin in the regulation of cell motility. Matrix Biol. 2000;19:377–87. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujita T, Azuma Y, Fukuyama R, Hattori Y, Yoshida C, Koida M, et al. Runx2 induces osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation and enhances their migration by coupling with PI3K-Akt signaling. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:85–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SU, Shin HK, Min YK, Kim SH. Emodin accelerates osteoblast differentiation through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation and bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene expression. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:741–7. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakasaki M, Yoshioka K, Miyamoto Y, Sasaki T, Yoshikawa H, Itoh K. IGF-I secreted by osteoblasts acts as a potent chemotactic factor for osteoblasts. Bone. 2008;43:869–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.07.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X, Zanello LP. Vitamin D receptor-dependent 1 alpha,25(OH)2 vitamin D3-induced anti-apoptotic PI3K/AKT signaling in osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1238–48. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young SR, Gerard-O’Riley R, Kim JB, Pavalko FM. Focal Adhesion Kinase is Important for Fluid Shear Stress Induced Mechanotransduction in Osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:411–24. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.081102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao LJ, Liu XG, Liu YZ, Liu YJ, Papasian Christopher J, Shao BY, et al. Genome-wide association study for femoral neck bone geometry. J Bone Miner R Posted. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090726. online 13 Jul 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]