Abstract

While the presence of phosphoinositides in the nuclei of eukaryotes and the identity of the enzymes responsible for their metabolism have been known for some time, their functions in the nucleus are only now emerging. This is illustrated by the recent identification of effectors for nuclear phosphoinositides. Like the cytosolic phosphoinositide signaling pathway, nuclear phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate (PI4,5P2) is at the center of the pathway and acts both as a messenger and as a precursor for many additional messengers. Here, recent advances in the understanding of nuclear phosphoinositide signaling and its functions are reviewed with an emphasis on PI4,5P2 and its role in gene expression. The compartmentalization of nuclear phosphoinositide phosphates (PIPn) remains a mystery, but emerging evidence suggests that phosphoinositides occupy several functionally distinct compartments.

Keywords: Phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate, Nuclear phosphoinositide cycle

Introduction

Phosphoinositides are lipid messengers that regulate many cellular processes in eukaryotic cells. Phosphatidylinositol (PI) is a negatively charged phospholipid that can be phosphorylated on the 3, 4, and 5 hydroxyls of the myo-inositol ring in all possible combinations. The resulting phosphatidylinositol phosphate (PIP), phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2), or phosphatidylinositol trisphosphate (PIP3), collectively called phosphoinositides (PIPn), are direct messengers and precursors to messengers (Figure 1A). The PI signaling cycle was discovered in the 1950s by the Hokins (Box 1)1. In the canonical cytoplasmic phosphoinositide cycle, an extracellular stimulus triggers the generation of phosphoinositide signals via an array of kinases, phosphatases and phospholipases. The phosphoinositide kinases are integrated into signaling pathways that generate phosphoinositide signals in specific subcellular compartments that regulate effector proteins at these sites2. This distribution is regulated by specific protein-protein interactions unique to each kinase. This site specific targeting allows for the generation of lipid messengers at specific cellular compartments and results in spatial specific phosphoinositide signaling pathways2.

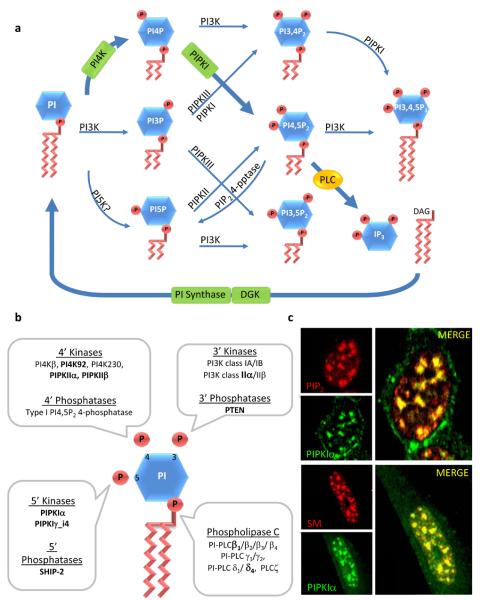

Figure 1.

Phosphoinositide kinases, phosphatases, and phospholipases. A. Canonical PI cycle. Inositol phospholipids are named according to the number and position of phosphate groups on the inositol headgroup. The singly phosphorylated PIPs (PI3P, PI4P and PI5P) are created by the phosphorylation of PI at the 3, 4 and possibly 5 positions. PI5P can also be generated by the type I PI4,5P2 4-phosphatase (type I 4-pptase). Theses PIPs act as intermediates for the synthesis of inositol bis- and tris-phosphates (PIP2 and PIP3). PIP2 is generated by phosphorylation of PI3P, PI4P or PI5P by the indicated PIP kinases and PI4,5P2 is hydrolyzed by PLC to form IP3 and DAG. PIP3 is generated by phosphorylation of PI4,5P2 by PI3K. The classical PI cycle is highlighted with bold arrows and enzymes. B. A graphic representation of PI and the kinases, phosphatases, and phospholipases that to date have been shown to be localized in the nucleus according to the position the on inositol head group where they act. Nuclear speckle targeted enzymes are indicated in bold. C. PIPKIα colocalizes with components of the mRNA-processing machinery in nuclear speckles and PIP2. Top panel: Cells were double labeled with an anti-PIPKIα polyclonal antibody and anti-PIP2 monoclonal antibody. Bottom panel: Cells were double-labeled with an anti-PIPKIα polyclonal antibody and human Sm antiserum (a nuclear speckle marker).

Box 1. Historical Perspective.

The phosphatidylinositol cycle was discovered in the 1950s by Lowell and Mabel Hokin1. Soon after, they discovered that PI could be phosphorylated sequentially on its myoinositol ring to generate PI4,5P293. While PI4,5P2 was originally thought of only as a metabolic precursor of soluble inositides, PI4,5P2 is now recognized as a potent second messenger that has been implicated in a diverse array of cellular processes2, 8, 50, 78, 94, 95. Over the last decades, evidence has accumulated indicating that there is a distinct nuclear PI cycle4, 6, 96.

The presence of lipids within the nucleus and in the nuclear membrane was described in the late 1960s79. During the 1970s and early 1980s, Manzoli and co-workers started to define the various lipid components within the nucleus and link them to nuclear processes97-99. It was first proposed by Smith and Wells (1983) that nuclear phosphoinositide generation occurred at the nuclear membrane28. They described the activities of DAG kinase, PI kinase and PIP kinase in isolated rat nuclear envelope. Cocco and colleagues showed the direct evidence of a nuclear phosphoinositide cycle in mouse erythroleukemia (MEL) cell nuclei stripped of their nuclear membrane by detergent. They reported that the detergent stripped nuclei maintained the ability to synthesize phosphoinositides and in fact, retained significant amounts of DAG, PI4P and PI4,5P2, as well as PI 4-kinase, and PI4P 5-kinase activities86. Additionally, it was determined that when MEL cells were induced to differentiate, the levels of non-membranous nuclear PI4,5P2 increased, while total cellular PI4,5P2 levels remained unchanged86 The existence of an autonomous nuclear PI cycle was also evident from further studies in 3T3 human fibroblast cells using differential cellular stimuli, bombesin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)3, 100. Stimulation by IGF-1 has been shown to cause a rapid increase in the mass of nuclear DAG along with a corresponding decrease in nuclear PI4,5P2, whereas bombesin was only able to affect DAG mass at the plasma membrane3.

Phosphatidylinositol-phosphate (PIP) kinase activity was identified by the Hokins in the early 1960's101, however, characterization of the PIP kinases was not pursued until nearly three decades later when the PIP kinases were successfully purified from erythrocytes102-104. PIP kinases are classified as type I, II, or III PIPK (PIPKI, PIPKII, PIPKIII) based on their biochemical properties, substrate specificity and sequence7. To date, PIPKIα, PIPKIγ_i4,

PIPKIIβ, and possibly PIPKIIα are found in the nucleus, in association with the nuclear matrix7, 18, 19.

Most of our knowledge of phosphoinositide signaling is derived from cytosolic signaling pathways, yet over the past several decades much evidence has established the existence of a nuclear phosphoinositide cycle. Although the roles played by phosphoinositides in the nucleus are only now emerging, it is clear that some aspects of nuclear phosphoinositide signaling are regulated differentially from that in the cytosol and on the plasma membrane3. This is emphasized by reports showing phosphoinositides in the inner nuclear envelope and also in nuclear compartments that are separate from known membranes4-7. The presence of phosphoinositides in the nucleus itself raises several questions: what are the functional implications attributed to the different phosphoinositides in the nucleus?; how is their function and metabolism regulated?; and how is their subnuclear localization achieved? Several functions have been proposed for nuclear phosphoinositides in regulating nuclear signaling processes. However, there is little mechanistic data defining how phosphoinositides regulate nuclear events. To date, nuclear phosphoinositides and derived inositol phosphates have been implicated in a wide range of functions including differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, stress responses, and gene expression4-6, 8, 9. This review will focus on functions attributed to nuclear phosphoinositides with an emphasis on PIPn effectors and mechanisms.

Nuclear phosphoinositide kinases

Nuclear and cytoplasmic phosphoinositide signaling share common enzymes. The phosphoinositide cycle involves the ordered phosphorylation of PI by PI kinase and PIP kinases forming all possible PIP2 isomers and PIP3 (Figure 1A). Specific isoforms of phosphoinositide kinases, phosphatases, and phospholipase C (PLC) are located within the nucleus (Figure 1B)10-14. Some of these enzymes are imported into the nucleus upon stimulation of cells, and in this context the roles of PI-PLCs, diacylglycerol (DAG), and PI3K have been reviewed extensively 5, 10, 13, 15.

Nuclear phosphoinositide signaling revolves around the generation of PI4,5P2 by phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases (PIPK). There are three classes of PIPKs, types I, II and III, and of these type I and II both generate PI4,5P2 although by utilizing different substrates, PI4P and PI5P, respectively16, 17. At least four members of this family of kinases, type Iα phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase (PIPKIα), type Iγ isoform 4 phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase (PIPKIγ_i4) and type II and IIβ phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase (PIPKIIα and PIPKIIβ) are localized to the nucleus7, 18, 19. These kinases are not exclusively localized to the nucleus and appear to have cytoplasmic functions as well7, 18, 20. The presence of type I and type II PIPKs in the nucleus suggest that different pools of PI4,5P2 are generated and these may regulate distinct nuclear functions as discussed below.

The targeting of phosphoinositide metabolizing enzymes to the nucleus is achieved by a number of mechanisms. While some of the enzymes contain defined nuclear localization sequences (NLS), others do not. For example, PIPKIIβ lacks a NLS, but is targeted to the nucleus through the “kinase insert region”, a nonhomologous sequence that separates the kinase domain of type I and II PIPKs7, 16, 19. PIPKIIβ is associated with the nuclear protein SPOP (speckle-type POZ domain protein) via the insert sequence and this interaction may modulate nuclear localization 21. Nuclear localization of the PI3,4,5P3 3-phosphatase PTEN depends upon a putative NLS and major vault protein-mediated import. However, PTEN has also been shown to diffuse through the nuclear pore. Importation of PTEN is regulated by monoubiquitinylation and by other pathways including oxidative stress22, 23. As a group the import of PI3K and PI-PLC isoforms is diverse occurring through an NLS or associated proteins and is modulated by growth factors and other stimuli5, 10.

In nuclei, both type I and II PIPKs are targeted to structures called interchromatin granule clusters or nuclear speckles7. Speckles are separated from known membrane in the interchromatin regions of the nucleoplasm. Yet, significantly, PI4,5P2 appears to be present at these sites, shown in Figure 1C7, 24. Nuclear speckles are also enriched in pre-messenger RNA processing factors suggesting a role in pre-mRNA processing7, 12, 24-26. Other enzymes involved in the nuclear PI cycle are localized at nuclear speckles or are diffuse throughout the nucleus8, 27. There is also evidence that phosphoinositides are generated on the inner nuclear envelope28-30 and are highly concentrated on nuclear envelope remnants31. The combined data indicate that there are distinct PI cycles within the nucleus both associated with and separate from membranes and this will be discussed in more detail below.

Role of Nuclear Type II PIP Kinase Isoforms in Stress Signaling

In response to oxidative and UV damage in mammalian cells PI5P, PI3,5P2 and PI3,4,5P3 are generated depending on the cell type and specific stimulus, indicating the activation of specific pathways32-34. PIPKIIβ and its substrate PI5P have been linked to nuclear stress response pathways34, 35. PIPKIIβ signaling within the nucleus putatively connects PI5P and type I PI4,5P2 4-phosphatase (type I 4-pptase) to p38-mediated stress response signaling34. As depicted in Figure 2, in response to oxidative or UV stress, PIPKIIβ is phosphorylated by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). This phosphorylation inhibits PIPKIIβ, resulting in the accumulation of nuclear PI5P34. Upon cellular stress, type I 4-pptase translocates to the nucleus and creates PI5P by dephosphorylation of PI4,5P2, indicating that PIPKIIβ and type I 4-pptase work together to regulate PI5P levels36, 37. Increased PI5P causes translocation of ING2, a nuclear PI5P binding protein to a chromatin-enriched fraction38. ING2 associates with and modulates the activity of histone acetylases and deacetylases, and induces apoptosis through p53 acetylation38, 39. Additionally, it was shown that ING2 regulation of p53 acetylation and apoptosis required both PI5P generation and an intact PI5P binding domain in ING2. The accumulation of nuclear PI5P facilitates the ING2-p53 apoptotic pathway by promoting ING2-dependent p53 acetylation38 (Figure 2).

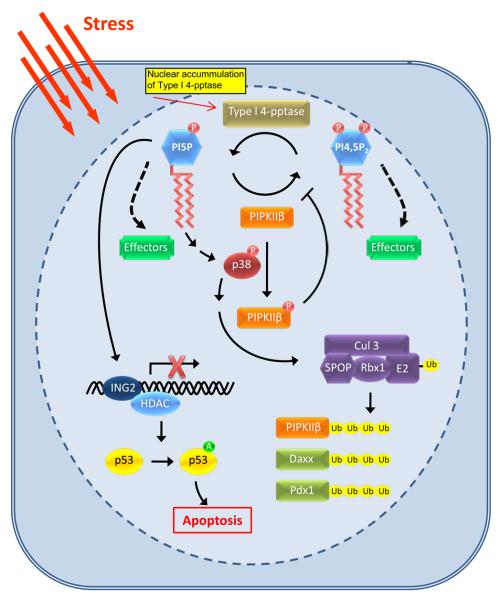

Figure 2.

A nuclear phosphoinositide-mediated stress response pathway. Under resting conditions, PIPKIIβ controls PI5P levels by its synthesis of PI4,5P2. Upon cellular stress, PIPKIIβ activity is attenuated via type 1 PI4,5P2 4-phosphatase and p38 MAPK activity resulting in the accumulation of PI5P. Specifically, in response to cellular stress, such as oxidative stress or UV irradiation, type 1 PI4,5P2 4-phosphatase translocates to the nucleus where it hydrolyzes PI4,5P2 into PI5P. Concurrently, PIPKIIβ is phosphorylated by activated p38 MAPK, inhibiting its lipid kinase activity and resulting in increased nuclear levels of PI5P. The accumulation of PI5P recruits ING2 to chromatin and promotes ING2-dependent p53 acetylation. Acetylation of p53 enhances its activity and stability and therefore increases apoptotic death. PI5P also may modulate an upstream activator of p38 MAPK, resulting in the activation of the Cul3-SPOP ubiquitin ligase complex toward multiple substrates, including PIPKIIβ. Represented are the defined functions of PI5P and PI4,5P2; however, both PI5P and PI4,5P2 may bind as of yet unidentified effectors (green boxes), which could play diverse roles in nuclear signaling. Ub = ubiquitin; A = acetylation

Recently, a novel mechanism has been revealed by which PIPKIIβ and PI5P accumulation regulates a nuclear ubiquitin ligase complex21. We identified an interaction between PIPKIIβ and SPOP, an adaptor protein that recruits substrates to Cul3-based ubiquitin ligases21. Ubiquitin ligases covalently attach ubiquitin to lysine residues on proteins to target for degradation or to modify activity40. Bunce and colleagues described a mechanism where type I 4-pptase generates PI5P leading to the stimulation of a p38-MAPK pathway that activates the Cul3-SPOP ubiquitin ligase complex. The Cul3-SPOP ubiquitin ligase complex ubiquitinylates PIPKIIβ and other proteins. PIPKIIβ down-regulates this pathway by converting PI5P to PI4,5P2. The expression of a PIPKIIβ kinase dead mutant stimulated the ubiquitinylation of itself and other Cul3-SPOP targets demonstrating a dominant negative effect and supporting a model where PI5P generation leads to activation of Cul3-SPOP activity21. As both PIPKIIβ and type I 4-pptase modulate SPOP activity this may also be a mechanistic connection between PIPKIIβ and insulin signaling. The major phenotype of the PIPKIIβ knockout mouse is enhanced insulin sensitivity34. PIPKIIβ and type I 4-pptase modulate the activity of SPOP toward ubiquitinylation of Pdx121. In turn, Pdx1 is a transcription factor that plays key roles in pancreatic beta-cell function and is modulated by oxidative stress41, 42.

One physiological function for PIPKIIβ appears to be the regulation of PI5P by conversion to PI4,5P2. Consistent with this model, PIPKIIβ and type I 4-pptase work synergistically to generate PI5P which in turn modulates apoptosis36 and ubiquitinylation by the Cul3-SPOP complex21. Such a mechanism is an intriguing contrast to the type I PIPK signaling pathways in which PI4,5P2, the product of the kinase, is the key regulatory species modulating effector proteins. Although PIPKIIβ may function by removal of PI5P, PIPKIIβ is also positioned to differentially regulate effectors through the generation of PI4,5P2, as shown in Figure 2. Since PIPKIIβ and SPOP are speckle targeted, both PI5P and PI4,5P2 could be in the same compartment positioned to regulate effectors differentially, as shown in Figure 2.

Gene expression and Nuclear Phosphoinositides

In eukaryotes, the generation of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) involves a series of events from transcription to export from the nucleus. Precursor RNAs (pre-mRNAs) are co-transcriptionally capped at the 5′-end, spliced, and processed at the 3′-end before they are exported to the cytoplasm as mature mRNA43. Each step in mRNA synthesis is subjected to regulatory events and requires macromolecular complexes consisting of many proteins and enzymes. Nuclear phosphoinositide signaling has been linked to mRNA processing, including splicing, 3′-end processing and export24, 38, 44-46 (Figure 3). There is emerging evidence that some actively transcribed genes localize to the nuclear periphery (inner nuclear membrane) and nuclear pore complexes, positioning them for modulation by phosphoinositides47.

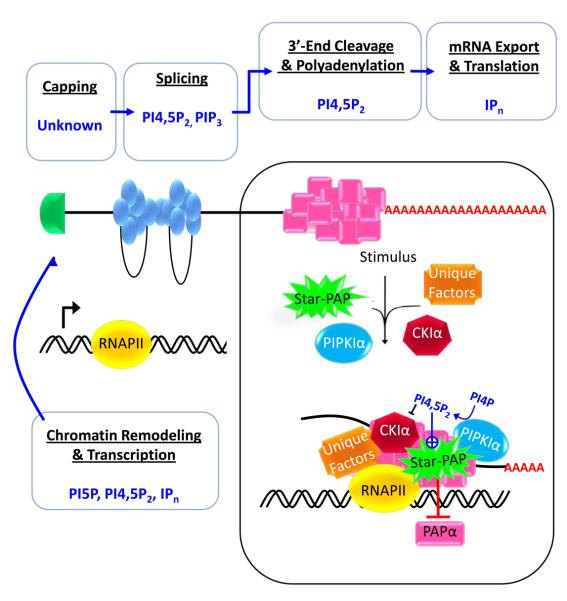

Figure 3.

Phosphoinositides in eukaryotic mRNA transcription and processing. A diagram depicting the events of mRNA generation in eukaryotes, including chromatin remodeling and transcription, mRNA processing (5′-end capping, splicing, and cleavage and polyadenylation), and mRNA export and translation, and the PIPn or IPn molecules that have been implicated in each step. Phosphoinositides have been implicated in most aspects of mRNA synthesis except for 5' capping. Phosphoinositide species and the process regulated are indicated.

This schematic also highlights the processing of mRNA at the 3′-end modulated by Star-PAP, the only nuclear effector identified to date that is directly activated by PI4,5P2. Star-PAP is a nuclear poly(A) polymerase that is required for the expression of select mRNAs. Star-PAP assembles into a complex with RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) and known 3′-processing factors, but the complex is notably devoid of canonical PAPα. The Star-PAP complex contains unique components, such as PIPKIα and the PI4,5P2 sensitive protein kinase CKIα. Star-PAP is necessary for the 3′-processing of its target mRNAs and functionally both PIPKIα and CKIα are required for the maturation of a subset of Star-PAP target mRNAs.

RNA processing and phosphoinositides

Nuclear speckles contain a number of components of the cellular pre-mRNA processing machinery including splicing factors, small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (nRNPs), and RNA polymerase II25. PI4,5P2 is present at speckles7 and the depletion of PI4,5P2 from a splicing efficient extract blocked splicing24. Reconstitution with exogenous PI4,5P2 failed to restore mRNA splicing to PI4,5P2-depleted fractions24, suggesting that factors associated with PI4,5P2 that are required for mRNA processing may also have been removed. As a result, the role of PI4,5P2 in pre-mRNA splicing remain ambiguous.

Splicing is coupled to the 3′-end processing of eukaryotic pre-mRNAs48. The 3′-end processing of pre-mRNA is key for gene expression and consists of two steps: cleavage followed by addition of a poly (A) tail43. Cleavage and polyadenylation are ordered processes involving the assembly of a large multimeric 3′-end formation complex, including poly (A) polymerase (PAP)49. The poly(A) tail of eukaryotic mRNA is required for export from the nucleus, stability, and translation43.

A recent link has been established between 3′-end processing and nuclear phosphoinositide signaling12. PIPKIα and its product PI4,5P2 localize at nuclear speckles7. Based on the hypothesis that PI4,5P2 signaling specificity is dependent on the interaction of PIPKs with PIP effectors2, 16, a yeast two-hybrid screen was performed to identify PIPKIα interacting proteins that may be PI4,5P effectors50. One interacting protein was a poly (A) polymerase that was named Star-PAP (Speckle Targeted PIPKIα Regulated-Poly(A) Polymerase) and this enzyme functions with PIPKIα to regulate pre-mRNA processing12.

Star-PAP is distinct from other members of the PAP family in domain architecture12. Unlike other PAPs, Star-PAP contains a polymerase domain that is split by a proline rich sequence and also has two nucleotide recognition motifs - a zinc finger and an RNA binding domain. Star-PAP and PIPKIα directly interact in vitro and in vivo and PI4,5P2 stimulated both recombinant and cell purified Star-PAP activity greater than 10-fold12. PI4,5P2 stimulated both the initiation (short poly(A) tails) and elongation (longer poly(A) tails) steps in polyadenylation. Thus, PI4,5P2 stimulated Star-PAP's ability to increase the length of the poly(A) tail by enhancing processivity of Star-PAP12.

Microarray analysis demonstrated that Star-PAP was required for the expression of a subset of mRNAs, many of which encode proteins involved in oxidative stress responses. Star-PAP and PIPKIα function together to control expression of these mRNAs12. However, Star-PAP is required for 3′-end cleavage, but PIPKIα is not. Star-PAP assembles into a stable 3′-end processing complex that also contains unique signaling components, such as PIPKIα and the PI4,5P2 sensitive protein kinase CKIα, but lack other PAPs12, 26. Functionally, PIPKIα and CKIα are required for the expression of specific Star-PAP target mRNAs12, 26. CKIα directly phosphorylates Star-PAP26, indicating that this kinase controls Star-PAP's ability to process target pre-mRNAs. These data indicate a phosphoinositide pathway that controls expression of specific mRNAs via 3′-end processing.

There is emerging evidence that the localization of genes to the nuclear periphery modulates the transcriptional activity of these genes47, 51, 52. Although the nuclear periphery is often associated with gene repression, in yeast some genes activated by cellular stress pathways are localized near the nuclear pore complex 47. In mammalian cells, it remains unclear if activation of these stress response pathways results in gene expression at the nuclear pore. However, such a system could be extrapolated to a mammalian system if Star-PAP-dependent genes where localized near the nuclear pore resulting in PI4,5P2-stimulated polyadenylation at the envelope. This would in turn position these inducible genes for rapid export of their mRNAs.

Star-PAP activity is specifically regulated by PI4,5P2 binding. Only a few nuclear proteins have been identified that bind nuclear phosphoinositides, including ING2, histone H1, BAF complex, the nuclear export factor Aly, and the nuclear receptors SF-1 and LRH-138, 45, 46, 53. These proteins are regulated by PI4,5P2 indicating that they are PI4,5P2 effectors. For example, PI4,5P2 binds histone H1 and H3 and contributes to chromatin unfolding and transcription45. PI4,5P2 binding to histone H1 reversed histone H1-mediated repression of RNA polymerase II transcription in vitro45. Further, the nuclear receptors SF-1 and LRH-1 require phosphoinositide binding for maximal activity54. These are emerging examples of phosphoinositide nuclear effectors, however to date, Star-PAP is the only enzyme identified that is specifically activated by PI4,5P2.

RNA export and phosphoinositides

In eukaryotes, mRNAs are exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm for translation. Like other nuclear trafficking events, mRNA export is a multi-step process that involves the generation of carrier-cargo complexes in the nucleus, transportation through the nuclear pore complex (NPC), and recycling of the carrier55, 56. In yeast, Mex67, (TAP in the mammalian system) acts as the primary mRNA nuclear export factor55. Mex67 heterodimerizes with Mtr2 and facilitates the export of mature nRNPs through the NPC55.

In addition to acting as a direct lipid messenger, PI4,5P2 serves as a precursor for the generation of higher inositol phosphates. PI4,5P2 is hydrolyzed PI-PLC to generate DAG and IP3. IP3 makes the direct precursor for higher inositol polyphosphates (IPs) such as inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphosphate (IP4), inositol 1,3,4,5,6-pentakisphosphate (IP5) and inositol 1,2,3,4,5,6- hexakisphosphate (IP6). In yeast, an in vivo role for IP6 and Gle1, a component of the cytoplasmic filament of the NPC, in mRNA export has been identified57. Mutation in PLC displayed defects in mRNA export and IP6 synthesis demonstrating the requirement for PI4,5P2 cleavage57. Similarly, inositol polyphosphate kinase 2 (Ipk2) or inositol polyphosphate kinase 1 (Ipk1) which convert IP3 to IP6 also have mRNA export defects57. IP6 was proposed as a positive regulator of Gle1-mediated mRNA export. Recent studies suggested that Gle1 and IP6 act together to stimulate the ATPase activity of Dbp5, a DEAD-box helicase that binds to Gle1 and remodels nRNP proteins58, 59. Mutations of ARGIII (Ipk2) that lowered the conversion of IP3 to IP6 also impaired mRNA export60. Thus, higher IPn messengers are generated from products of PI4,5P2 hydrolysis indicating its central role.

In yeast, the nuclear export factor Yra1 interacts with Mex67 and is required for mRNA export61, 62. The Yra1 mammalian isoform, Aly, is regulated by nuclear PI3K signaling and interacts with PI4,5P2 and PI3,4,5P3, which is required for its localization to nuclear speckles53. Disruption of the PI3,4,5P3 association with Aly diminished speckle association and mRNA export, making Aly a putative PI3,4,5P3 target in regulating mRNA export53. This positions nuclear phosphoinositides for regulation of mRNA export directly through a target export factor or indirectly via hydrolysis of PI4,5P2 and generation of IPns.

Nuclear Actin and Phosphoinositides

Actin has been identified as a central component of the nuclear matrix and is present as both G- and F-actin63-65. Nuclear actin has been implicated in transcription, chromatin remodeling, mRNA processing, regulation of transcription factors and intranuclear motility66, 67. Actin is a key cytoplasmic component of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton and is critical for cell motility, membrane dynamics, cytokinesis, organelle transport, and many other processes. It is not clear how actin gets into the nucleus as is does not have a classical NLS, and specific import receptors have not been reported. It is postulated that actin binds to nuclear actin binding proteins such as cofilin, CapG, and MAL, which contain NLS motifs, and that these proteins piggy-back actin into the nucleus66.

Phosphoinositides are key regulators of actin dynamics in the cytoplasm68. PI4,5P2 modulates the activity of many regulatory proteins that control actin polymerization and association with other proteins. For example, PIP2 activates N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex-induced actin filament nucleation and inhibits the actin-binding activity of cofilin66, 67. PI4,5P2 also mediates uncapping of actin where PI4,5P2 induces capping proteins, such as those in the gelsolin family and CapZ, to disassociate from the actin filaments66, 67. Considering that PI4,5P2 is a major regulator of actin in the cytoplasm, one could speculate the nuclear actin binding proteins would be prime PI4,5P2 targets in the nucleus66, 67.

The regulation of nuclear actin has been linked with PI signaling. The nuclear equivalent of the cytoskeleton, i.e. the nuclear matrix, and nuclear cytoskeletal proteins bind to PI4,5P266, 67. Profilin I, a regulatory component of actin organization in the nucleus, is required for efficient mRNA synthesis and is regulated by PI4,5P266, 67. Profilin I localizes to nuclear speckles along with PI4,5P2 and has also been implicated in pre-mRNA splicing69. The Arp2/3 complex is regulated by PI4,5P2 in the cytoplasm and localizes to the nucleus, where it appears to directly interact with RNA polymerase II and participate in transcription70. In addition, myosin I regulates transcription by RNA polymerase I and II71. Most recently, the p53-cofactor JMY was discovered to be a multifunctional actin nucleation factor72. A theme among these processes is that many nuclear actin-binding proteins are regulated by PI4,5P2 or indirectly by PI signaling.

Chromatin remodeling complexes, such as the BAF (Brahma related gene association factor) and INO80 complexes contain β-actin as an integral component73. PI4,5P2 modulates chromatin remodeling possibly through regulation of the PI4,5P2 actin binding site on the chromatin remodeling protein BRG174, suggesting that one function of PI4,5P2 could be to stabilize these complexes within the nuclear matrix and contribute to gene expression75. In resting T-lymphocytes, the chromatin remodeling complex BAF is primarily soluble. Upon stimulation, the BAF complex translocates to an insoluble fraction by association of the complex with chromatin46. Association with chromatin is mediated by PI4,5P2 levels in T lymphocytes46. Association of the BAF complex with the nuclear matrix requires BRG1 (a SWI/SNF2-like ATPase core subunit), β-actin and BAF53, an actin-related protein76, 77. BRG1, has two actin binding domains one of which contains a lysine-rich region that is required for function and can bind PI4,5P274, 77. It was proposed that the actin monomer is bound to both domains and PI4,5P2 association disrupts actin binding to one domain, allowing a previously occluded site of actin to interact with components of the nuclear matrix74. This mechanism is analogous to PI4,5P2-mediated uncapping of actin during actin polymerization78. PI4,5P2 binding to BRG1 may facilitate recruitment to chromatin and stabilize the chromatin remodeling complex by an increased interaction with matrix. Alternatively, PI4,5P2 could stimulate the interaction of BRG1 with other BAF components, or by engaging actin as a bridge for the remodeling complex to the chromatin through its increased interaction with nuclear matrix. This could lead to the stable association of the remodeling complex with an active promoter on a condensed chromatin.

The initial identification of chromatin associated lipid molecules was by Rose and colleagues in 196579. Since then various studies have suggested the regulation of chromatin remodeling by IPns that are derived from IP380. Ipk2 phosphorylates IP3 to generate IP4 and IP557, 81 and strikingly Ipk2 acts as a transcriptional regulator known as Arg8281. In an arg82 deficient yeast strain, chromatin remodeling at PHO5, a phosphate responsive promoter, is impaired. In a complementary study, various ATP dependent chromatin remodeling complexes including NURF, ISWI, SWI-SNF, and INO80 were shown to be sensitive to various IPns82, 83. In addition, the SWI-SNF and INO80 chromatin remodeling factors were not recruited to the phosphate responsive promoters suggesting the role of IPns in chromatin organization84. Actin is required for efficient DNA binding, ATPase activity, and nucleosome mobilization in the INO80 complex, as INO80 complexes lacking actin were deficient in these activities77. It appears that a major function of actin is to allosterically regulate remodeling of the chromatin remodeling assemblies that are sensitive to IPns82. The presence of actin in the chromatin remodeling complexes and the regulation of chromatin remodeling by IPns supports a triangular relation between IPns, chromatin and nuclear actin82.

The Compartment Conundrum

Nuclear phosphoinositides and their synthetic enzymes regulate nuclear processes, but the mechanisms and the organization of phosphoinositides in the nucleus is poorly understood (Table 1). PI4,5P2 has long been considered a membrane anchored precursor of soluble inositol phosphates (IP3 and higher IPns)85. However, the retention of PI4,5P2 in detergent stripped nuclei86 and the evidence that phosphoinositides and their synthetic enzymes are localized at speckles and other sub-nuclear sites lacking defined membranes insinuates a unique compartment7, 12, 24. If nuclear phosphoinositides are not in a membrane, there must be a mechanism to shield the hydrophobic acyl chains from solvent. The amphipathic structure of PI4,5P2 is suited for membrane anchorage, but renders it energetically and thermodynamically unfavorable to freely move within the nucleus. The differential localization of PI4,5P2 within nuclei suggests that there are different pools and these could be used to regulate diverse nuclear functions. The data suggest that there are at least two pools of phosphoinositides: a nuclear envelope pool and another within the nucleus that is separate from known membrane (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Nuclear targeted phosphoinositides: Location, Effectors, and Proposed Function.

| Inositol molecules |

PI Enzymes | Nuclear Location |

Effectors | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI3P | PI3-kinase | Nucleolus Nuclear Matrix |

Unknown | Cell cycle regulation | 10, 105 |

| PI4P | PI4-kinase | Nuclear Matrix | Unknown | Cell cycle, Precursor of PI4,5P2 |

11 |

| PI5P | PI5-kinase | Nuclear Matrix Chromatin |

ING2 Others? |

Chromatin organization, Apoptosis, DNA damage |

38 |

| PI3,4P2 | SHIP-2, PIP Kinase IIβ |

Membrane Nuclear Speckle |

Unknown | Pre-mRNA splicing | 14, 106 |

| PI4,5P2 | PIP Kinase Iα, PIP Kinase IIβ |

Membrane Nuclear Speckle Nuclear Matrix Chromatin |

Star-PAP, ING2, Aly, BRG1 |

3′-end processing, Splicing, Chromatin organization, precursor for IP3 |

12, 24 |

| PI3,4,5P3 | PIP Kinase I, PIP3 Kinase |

Nuclear Matrix | PIP3BP Others? |

Cell cycle, Differentiation, proliferation |

107, 108 |

| DAG | PI-PLC | Nuclear Matrix | Unknown | Cell cycle, Differentiation, Proliferation |

13 |

| Ins1,4,5P3 | PI-PLC, | Nuclear Matrix | Unknown | Calcium signaling | 87 |

| IPn (IP3, IP4, IP5, IP6) |

IPn kinases | Nuclear Matrix Chromatin |

Unknown | mRNA export, Chromatin structure |

84, 109 |

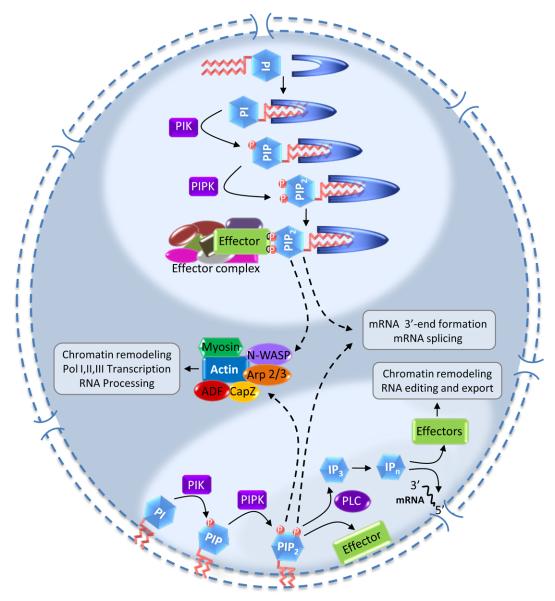

Figure 4.

A model illustrating the compartmentalization of phosphoinositide signaling in the nucleus. Current data suggests two compartments for the nuclear phosphoinositide cycle: One associated with the nuclear envelope and another in a subnuclear compartment separate from known membrane structures. In both compartments, PI is sequentially phosphorylated by PI kinases (PIK) and PIP kinases (PIPK) to generate PIP2, which could then be metabolized by PLC to generate IP3 and then higher inositol phosphates (IPn) or phosphorylated by PI 3-kinase creating PIP3. In subnuclear compartments, phosphoinositides are hypothesized to be associated with carrier or effector proteins. Such proteins could be specific for certain functions and/or could present phosphoinositides to other effectors. In addition, regulation of nuclear actin polymerization and actin binding proteins, such as N-WASP, CapZ and ADF (actin/cofilin depolymerising factor), either from envelope-bound or endonuclear phosphoinositides (shown by dashed arrows) has been shown to affect many aspects of gene expression.

A fraction of nuclear PIP2 is present in the inner envelope and it is reasonable to assume that a component of PI4,5P2 hydrolysis by nuclear PLCs would also occur within the nuclear envelope generating DAG and IP329. Echevarria and colleagues demonstrated that the inner face of the nuclear envelope and invaginations of the envelope contain IP3 receptors that release Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope87. This location is consistent with the release of Ca2+ into the nucleus via the IP3 receptor channel4, 5, 30, 87. At the inner nuclear envelope the generation of DAG could activate PKC and PI3K may generate 3-phosphorylated phosphoinositides.

PI4,5P2 and phosphoinositide generating enzymes that are present at nuclear speckles are separate from known membrane structures2, 7-9, 37. The motifs of PI4,5P2 binding proteins contain charged residues that the head group of inositol lipids interact with69. This would leave the hydrophobic tails free; however it seems unlikely that the acyl chains would be solvent exposed. There are other lipids in the nucleus such as phosphatidylcholine88 and it is possible that the phosphoinositides and other lipids form a mixed micelle structure, thus eluding the unfavorable constraints of free acyl chains. Such structures would have to be resistant to detergents and would not be detectable by current electron microscopy approaches.

Another possibility is that the phosphoinositides are associated with carrier proteins in the nucleus that contain phosphoinositide acyl chain binding pockets. Such proteins would integrate the hydrophobic acyl chain in the binding cleft exposing only the charged inositol head group. These proteins could move freely in the nucleus to deliver PI specifically to the effector protein complex. It has been previously suggested that phosphoinositide transfer proteins (PITPs) are involved in nuclear import of PI in mammalian cells89-91 and hypothetical carrier proteins may function similar to the PITPs (Figure 4). Solution of the crystal structure for the yeast PITP Sec14p revealed a large hydrophobic pocket into which PI is inserted92. The incorporation of phosphoinositides into individual binding proteins may modulate folding or structure and the bound phosphoinositide could be modified by kinases, phosphatases or phospholipases leading to changes in binding protein activity or localization. The existence of such a system will provide solutions to both the energetic constraints and the functioning of PI4,5P2 at non-membranous sites in the nucleus. A similar presentation has been considered for the soluble inositides, in which IP6 bound to Gle1 was proposed to act as co-effector for Dbp5 in a Dbp5:Gle1 complex during RNA export56, 59. Additionally, a PIPn carrier protein could itself be a PIPn effector. Such a model would be similar to the nuclear receptors SF-1 and LRH-1 that integrate phosphoinositides into a hydrophobic pocket where the lipid is required for activity54. This model is attractive, as the bound PIPn could be phosphorylated or hydrolyzed which could control functional changes in the effector protein (Figure 4). Such a paradigm could be important for proteins that perform multiple functions in gene expression.

Future perspectives and concluding remarks

It is evident from current literature that nuclear phosphoinositides and in particular PI4,5P2 regulate aspects of gene expression and other functions. Despite increasing information from chromatin remodeling, mRNA splicing, and recently mRNA 3′-end processing, there remain many questions. Additional PIPn effectors, like Star-PAP, will be key to unraveling the intricate mechanisms involved in the regulation of the nuclear PI cycle. Identification of the PI-sensitive components of nuclear signaling pathways will reveal insights of phosphoinositide function in the nucleus. The identification of putative PIPn carrier/effector proteins will be central for understanding how phosphoinositides regulate nuclear events.

Phosphoinositides are components of the nuclear interior but the environment of nuclear phosphoinositides remains ambiguous. The localization of nuclear phosphoinositides has been mapped by a variety of techniques. From these approaches, phosphoinositides and their metabolizing enzymes have been found in the nuclear envelope. However, many studies have localized nuclear phosphoinositides and the enzymes that synthesize or metabolize phosphoinositides at nuclear speckles, cajal bodies, nucleoli, nuclear matrix, and chromatin8, 9. The current evidence supports a model where nuclear phosphoinositide signaling is compartmentalized into either the nuclear envelope or a unique subnuclear protein-lipid compartment(s). A clear objective for the field is to characterize how the distinct pools of phosphoinositides and PI metabolizing enzymes are maintained in separate compartments in the nucleus and define the function of the lipid messengers in these compartments.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank members of the Anderson lab, past and present. We apologize to the authors of numerous studies whose work had to be omitted from the discussion due to space limitations. This work is supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health grant R01 GM051968 to R.A.A, NIH fellowship F32 GM082005 to C.A.B., and AHA fellowship # 0920072G to R.S.L.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hokin MR, Hokin LE. Enzyme secretion and the incorporation of P32 into phospholipides of pancreas slices. J Biol Chem. 1953;203:967–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heck JN, et al. A conspicuous connection: structure defines function for the phosphatidylinositol-phosphate kinase family. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42:15–39. doi: 10.1080/10409230601162752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Divecha N, et al. The polyphosphoinositide cycle exists in the nuclei of Swiss 3T3 cells under the control of a receptor (for IGF-I) in the plasma membrane, and stimulation of the cycle increases nuclear diacylglycerol and apparently induces translocation of protein kinase C to the nucleus. Embo J. 1991;10:3207–3214. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04883.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irvine RF. Nuclear lipid signaling. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:RE13. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.150.re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irvine RF. Nuclear lipid signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:349–360. doi: 10.1038/nrm1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cocco L, et al. Nuclear inositol lipid signaling. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2001;41:361–384. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(00)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boronenkov IV, et al. Phosphoinositide signaling pathways in nuclei are associated with nuclear speckles containing pre-mRNA processing factors. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3547–3560. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunce MW, et al. Nuclear PI(4,5)P(2): a new place for an old signal. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzales ML, Anderson RA. Nuclear phosphoinositide kinases and inositol phospholipids. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:252–260. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Visnjic D, Banfic H. Nuclear phospholipid signaling: phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C and phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Pflugers Arch. 2007;455:19–30. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Payrastre B, et al. A differential location of phosphoinositide kinases, diacylglycerol kinase, and phospholipase C in the nuclear matrix. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5078–5084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellman DL, et al. A PtdIns4,5P2-regulated nuclear poly(A) polymerase controls expression of select mRNAs. Nature. 2008;451:1013–1017. doi: 10.1038/nature06666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goto K, et al. Diacylglycerol, phosphatidic acid, and the converting enzyme, diacylglycerol kinase, in the nucleus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deleris P, et al. SHIP-2 and PTEN are expressed and active in vascular smooth muscle cell nuclei, but only SHIP-2 is associated with nuclear speckles. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38884–38891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalhoub N, Baker SJ. PTEN and the PI3-kinase pathway in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:127–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson RA, et al. Phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases, a multifaceted family of signaling enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9907–9910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.9907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rameh LE, et al. A new pathway for synthesis of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Nature. 1997;390:192–196. doi: 10.1038/36621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schill NJ, Anderson RA. Two novel phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type Igamma splice variants expressed in human cells display distinctive cellular targeting. Biochem J. 2009;422:473–482. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciruela A, et al. Nuclear targeting of the beta isoform of type II phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase (phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase) by its alpha-helix 7. Biochem J. 2000;346(Pt 3):587–591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doughman RL, et al. Membrane ruffling requires coordination between type Ialpha phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase and Rac signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23036–23045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunce MW, et al. Coordinated activation of the nuclear ubiquitin ligase Cul3-SPOP by the generation of phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8678–8686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang CJ, et al. PTEN nuclear localization is regulated by oxidative stress and mediates p53-dependent tumor suppression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3281–3289. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00310-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalhoub N, et al. Cell type specificity of PI3K signaling in Pdk1- and Pten-deficient brains. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1619–1624. doi: 10.1101/gad.1799609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osborne SL, et al. Nuclear PtdIns(4,5)P2 assembles in a mitotically regulated particle involved in pre-mRNA splicing. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2501–2511. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.13.2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spector DL. Macromolecular domains within the cell nucleus. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:265–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzales ML, et al. CKIalpha is associated with and phosphorylates star-PAP and is also required for expression of select star-PAP target messenger RNAs. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12665–12673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800656200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cocco L, et al. Nuclear inositides: PI-PLC signaling in cell growth, differentiation and pathology. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith CD, Wells WW. Phosphorylation of rat liver nuclear envelopes. II. Characterization of in vitro lipid phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:9368–9373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran D, et al. Cellular distribution of polyphosphoinositides in rat hepatocytes. Cell Signal. 1993;5:565–581. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(93)90052-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malviya AN, et al. Stereospecific inositol 1,4,5-[32P]trisphosphate binding to isolated rat liver nuclei: evidence for inositol trisphosphate receptor-mediated calcium release from the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9270–9274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garnier-Lhomme M, et al. Nuclear envelope remnants: fluid membranes enriched in sterols and polyphosphoinositides. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones DR, et al. The identification of phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate in T-lymphocytes and its regulation by interleukin-2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18407–18413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halstead JR, et al. A novel pathway of cellular phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-trisphosphate synthesis is regulated by oxidative stress. Curr Biol. 2001;11:386–395. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones DR, et al. Nuclear PtdIns5P as a transducer of stress signaling: an in vivo role for PIP4Kbeta. Mol Cell. 2006;23:685–695. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamia KA, et al. Increased insulin sensitivity and reduced adiposity in phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase beta−/− mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5080–5087. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.5080-5087.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou J, et al. Type I phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 4-phosphatase regulates stress-induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16834–16839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708189104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bunce MW, et al. Stress-ING out: phosphoinositides mediate the cellular stress response. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:pe46. doi: 10.1126/stke.3602006pe46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gozani O, et al. The PHD finger of the chromatin-associated protein ING2 functions as a nuclear phosphoinositide receptor. Cell. 2003;114:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00480-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng X, et al. Different HATS of the ING1 gene family. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:532–538. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pintard L, et al. Cullin-based ubiquitin ligases: Cul3-BTB complexes join the family. EMBO J. 2004;23:1681–1687. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaneto H, et al. PDX-1 functions as a master factor in the pancreas. Front Biosci. 2008;13:6406–6420. doi: 10.2741/3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaneto H, et al. PDX-1 and MafA play a crucial role in pancreatic beta-cell differentiation and maintenance of mature beta-cell function. Endocr J. 2008;55:235–252. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k07e-041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore MJ, Proudfoot NJ. Pre-mRNA processing reaches back to transcription and ahead to translation. Cell. 2009;136:688–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Macbeth MR, et al. Inositol hexakisphosphate is bound in the ADAR2 core and required for RNA editing. Science. 2005;309:1534–1539. doi: 10.1126/science.1113150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu H, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate reverses the inhibition of RNA transcription caused by histone H1. Eur J Biochem. 1998;251:281–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao K, et al. Rapid and phosphoinositol-dependent binding of the SWI/SNF-like BAF complex to chromatin after T lymphocyte receptor signaling. Cell. 1998;95:625–636. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akhtar A, Gasser SM. The nuclear envelope and transcriptional control. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:507–517. doi: 10.1038/nrg2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rigo F, Martinson HG. Polyadenylation releases mRNA from RNA polymerase II in a process that is licensed by splicing. RNA. 2009;15:823–836. doi: 10.1261/rna.1409209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mandel CR, et al. Protein factors in pre-mRNA 3′-end processing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1099–1122. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7474-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doughman RL, et al. Phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases put PI4,5P(2) in its place. J Membr Biol. 2003;194:77–89. doi: 10.1007/s00232-003-2027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruault M, et al. Re-positioning genes to the nuclear envelope in mammalian cells: impact on transcription. Trends Genet. 2008;24:574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taddei A. Active genes at the nuclear pore complex. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okada M, et al. Akt phosphorylation and nuclear phosphoinositide association mediate mRNA export and cell proliferation activities by ALY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8649–8654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802533105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krylova IN, et al. Structural analyses reveal phosphatidyl inositols as ligands for the NR5 orphan receptors SF-1 and LRH-1. Cell. 2005;120:343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cole CN, Scarcelli JJ. Transport of messenger RNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stewart M. Ratcheting mRNA out of the nucleus. Mol Cell. 2007;25:327–330. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.York JD, et al. A phospholipase C-dependent inositol polyphosphate kinase pathway required for efficient messenger RNA export. Science. 1999;285:96–100. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lund MK, Guthrie C. The DEAD-box protein Dbp5p is required to dissociate Mex67p from exported mRNPs at the nuclear rim. Mol Cell. 2005;20:645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alcazar-Roman AR, et al. Inositol hexakisphosphate and Gle1 activate the DEAD-box protein Dbp5 for nuclear mRNA export. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:711–716. doi: 10.1038/ncb1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saiardi A, et al. Inositol polyphosphate multikinase (ArgRIII) determines nuclear mRNA export in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2000;468:28–32. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strasser K, Hurt E. Yra1p, a conserved nuclear RNA-binding protein, interacts directly with Mex67p and is required for mRNA export. Embo J. 2000;19:410–420. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.3.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zenklusen D, et al. The yeast hnRNP-Like proteins Yra1p and Yra2p participate in mRNA export through interaction with Mex67p. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4219–4232. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4219-4232.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rando OJ, et al. Searching for a function for nuclear actin. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:92–97. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01713-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakayasu H, Ueda K. Association of actin with the nuclear matrix from bovine lymphocytes. Exp Cell Res. 1983;143:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(83)90108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakayasu H, Ueda K. Ultrastructural localization of actin in nuclear matrices from mouse leukemia L5178Y cells. Cell Struct Funct. 1985;10:305–309. doi: 10.1247/csf.10.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vartiainen MK. Nuclear actin dynamics--from form to function. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2033–2040. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gieni RS, Hendzel MJ. Actin dynamics and functions in the interphase nucleus: moving toward an understanding of nuclear polymeric actin. Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;87:283–306. doi: 10.1139/O08-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mao YS, Yin HL. Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton by phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5 kinases. Pflugers Arch. 2007;455:5–18. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Skare P, Karlsson R. Evidence for two interaction regions for phosphatidylinositol(4,5)-bisphosphate on mammalian profilin I. FEBS Lett. 2002;522:119–124. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02913-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoo Y, et al. A novel role of the actin-nucleating Arp2/3 complex in the regulation of RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7616–7623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ye J, et al. Nuclear myosin I acts in concert with polymeric actin to drive RNA polymerase I transcription. Genes Dev. 2008;22:322–330. doi: 10.1101/gad.455908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zuchero JB, et al. p53-cofactor JMY is a multifunctional actin nucleation factor. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:451–459. doi: 10.1038/ncb1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zheng B, et al. Nuclear actin and actin-binding proteins in the regulation of transcription and gene expression. FEBS J. 2009;276:2669–2685. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rando OJ, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-dependent actin filament binding by the SWI/SNF-like BAF chromatin remodeling complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2824–2829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032662899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Olave IA, et al. Nuclear actin and actin-related proteins in chromatin remodeling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:755–781. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eisen JA, et al. Evolution of the SNF2 family of proteins: subfamilies with distinct sequences and functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2715–2723. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.14.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shen X, et al. Involvement of actin-related proteins in ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Mol Cell. 2003;12:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yin HL, Janmey PA. Phosphoinositide regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:761–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rose HG, Frenster JH. Composition and metabolism of lipids within repressed and active chromatin of interphase lymphocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1965;106:577–591. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(65)90073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jones DR, Divecha N. Linking lipids to chromatin. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Odom AR, et al. A role for nuclear inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate kinase in transcriptional control. Science. 2000;287:2026–2029. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shen X, et al. Modulation of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes by inositol polyphosphates. Science. 2003;299:112–114. doi: 10.1126/science.1078068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rando OJ, et al. Second messenger control of chromatin remodeling. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:81–83. doi: 10.1038/nsb0203-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Steger DJ, et al. Regulation of chromatin remodeling by inositol polyphosphates. Science. 2003;299:114–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1078062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alcazar-Roman AR, Wente SR. Inositol polyphosphates: a new frontier for regulating gene expression. Chromosoma. 2008;117:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cocco L, et al. Synthesis of polyphosphoinositides in nuclei of Friend cells. Evidence for polyphosphoinositide metabolism inside the nucleus which changes with cell differentiation. Biochem J. 1987;248:765–770. doi: 10.1042/bj2480765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Echevarria W, et al. Regulation of calcium signals in the nucleus by a nucleoplasmic reticulum. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:440–446. doi: 10.1038/ncb980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hunt AN, et al. Highly saturated endonuclear phosphatidylcholine is synthesized in situ and colocated with CDP-choline pathway enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8492–8499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hunt AN, et al. Use of mass spectrometry-based lipidomics to probe PITPalpha (phosphatidylinositol transfer protein alpha) function inside the nuclei of PITPalpha+/+ and PITPalpha−/− cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:1063–1065. doi: 10.1042/BST0321063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rubbini S, et al. Phosphoinositide signalling in nuclei of Friend cells: DMSO-induced differentiation reduces the association of phosphatidylinositol-transfer protein with the nucleus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;230:302–305. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.5950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Snoek GT. Phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins: emerging roles in cell proliferation, cell death and survival. IUBMB Life. 2004;56:467–475. doi: 10.1080/15216540400012152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sha B, et al. Crystal structure of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae phosphatidylinositol-transfer protein. Nature. 1998;391:506–510. doi: 10.1038/35179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hokin LE. Receptors and phosphoinositide-generated second messengers. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:205–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.001225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Czech MP. PIP2 and PIP3: complex roles at the cell surface. Cell. 2000;100:603–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McLaughlin S, et al. PIP(2) and proteins: interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:151–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ye K, Ahn JY. Nuclear phosphoinositide signaling. Front Biosci. 2008;13:540–548. doi: 10.2741/2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Manzoli FA, et al. Role of chromatin phospholipids on template availability and ultrastructure of isolated nuclei. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1982;20:247–262. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(82)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Manzoli FA, et al. Chromatin lipids and their possible role in gene expression. A study in normal and neoplastic cells. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1978;17:175–194. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(79)90013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Manzoli FA, et al. Chromatin phospholipids in normal and chronic lymphocytic leukemia lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1977;37:843–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Martelli AM, et al. Temporal changes in intracellular distribution of protein kinase C in Swiss 3T3 cells during mitogenic stimulation with insulin-like growth factor I and bombesin: translocation to the nucleus follows rapid changes in nuclear polyphosphoinositides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;177:480–487. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)92009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hokin LE, Hokin MR. The Incorporation of 32p from Triphosphate into Polyphosphoinositides (Gamma-32p)Adenosine and Phosphatidic Acid in Erythrocyte Membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1964;84:563–575. doi: 10.1016/0926-6542(64)90126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bazenet CE, et al. The human erythrocyte contains two forms of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase which are differentially active toward membranes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18012–18022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jenkins GH, et al. Type I phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase isoforms are specifically stimulated by phosphatidic acid. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11547–11554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ling LE, et al. Characterization and purification of membrane-associated phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate kinase from human red blood cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5080–5088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gillooly DJ, et al. Localization of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in yeast and mammalian cells. Embo J. 2000;19:4577–4588. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yokogawa T, et al. Evidence that 3′-phosphorylated polyphosphoinositides are generated at the nuclear surface: use of immunostaining technique with monoclonal antibodies specific for PI 3,4-P(2) FEBS Lett. 2000;473:222–226. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01535-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tanaka K, et al. Evidence that a phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-binding protein can function in nucleus. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3919–3922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Neri LM, et al. Proliferating or differentiating stimuli act on different lipid-dependent signaling pathways in nuclei of human leukemia cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:947–964. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-02-0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.York JD, Majerus PW. Nuclear phosphatidylinositols decrease during S-phase of the cell cycle in HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7847–7850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]