Abstract

Distraction Osteogenesis (DO) is a process which induces direct new bone formation as a result of mechanical distraction. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) is a cytokine that can modulate osteoblastogenesis. The direct effects of TNF on direct bone formation in rodents are hypothetically mediated through TNF receptor 1 and/or 2 (TNFR1/2) signaling. We utilized a unique model of mouse DO to assess the effects of 1) TNFR homozygous null gene alterations on direct bone formation and 2) rmTNF on wild type (WT), TNFR1 -/- (R1KO), and TNR2 -/- (R2KO) mice. Radiological and histological analyses of direct bone formation in the distraction gaps demonstrated no significant differences between the WT, R1KO, R2KO, or TNFR1 -/- & R2 -/- (R1&2KO) mice. R1&2KO mice had elevated levels of serum TNF but demonstrated no inhibition of new bone formation. Systemic administration by osmotic pump of rmTNF during DO (10 ug/ kg/day) resulted in significant inhibition of gap bone formation measures in WT and R2KO mice, but not in R1KO mice. We conclude that exogenous rmTNF and/or endogenous TNF act to inhibit new bone formation during DO by signaling primarily through TNFR1.

Keywords: TNF receptors, distraction osteogenesis, mouse

Introduction

Distraction Osteogenesis (DO) is a term that relates to a collection of clinical and/ or experimental protocols that can result in accelerated direct bone formation. DO, as modeled here, is induced by gradually pulling apart the edges of a tibial bone fracture, using an external fixator, to permit formation of new bone in the slowly expanding gap. New bone formation (direct, intramembranous, appositional, regenerative osteoblastogenesis) during DO is well organized and during the early phases is spatially isolated from the subsequent process of bone resorption/remodeling.

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) is an inflammatory cytokine that can play a role in modulating both osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Previous studies have demonstrated the ability of TNF to block multiple osteoblast functions in vitro as well as bone formation/repair in vivo1. Though high levels of TNF are known to inhibit osteoblastogenesis in culture and in vivo2; nevertheless, low doses can enhance osteoblast proliferation in culture and impaired osteoblastogenesis has been demonstrated in TNFR1/R2 double knockout mice3-5. This suggests that normal expression of TNF is required for optimal bone formation but that unregulated or excessive expression can contribute to skeletal pathology.

Previous studies have shown that aging, menopause, alcohol abuse, and arthritis can be correlated with osteoporosis, decreased bone mass, risk of fractures, and impaired fracture healing 1, 6-11. Two characteristics of the above osteoporotic states are a relative impairment in osteoblastogenesis and an abnormal elevation in serum TNF levels. The DO model coupled with genetically modified mouse strains provides the opportunity to study the effects of modulation of the TNF signaling axis on direct bone formation.

The above considerations have led to the investigations reported here employing a unique mouse DO model. This report presents the results from experiments on the effects of the genetic deficiency of TNFR1, TNFR2, and TNFR1&2 on DO, and on the effects of systemic administration of rmTNF on new bone formation during DO in WT, R1KO, and R2KO mice. We hypothesized that only the genetic deficiency of both TNF receptors would compromise the DO process and that only the genetic deficiency of TNFR1 would block the osteoinhibitive effects of rmTNF.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male C57BL/6 (WT, 0664), R1KO (2818), R2KO (2620), and R1&2 KO (3243) mice were purchased from Jackson Industries (Bar Harbor, ME). They were housed in individual cages in temperature (22°C) and humidity (50%) controlled rooms having a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. All mice were handled by animal care personnel for 5-7 days prior to surgery. In all studies, the mice were assigned to respective experimental groups with mean body weights equal to that of the control group (± 4 g) for the study. The following studies were performed in overlapping time intervals. All research protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Distraction Protocol

As previously described; briefly, following acclimation and under Nembutal anesthesia, each mouse underwent placement of an external fixator and osteotomy to the left tibia12. Four 27-gauge, 1.25 in needles were manually drilled through the tibia (two proximally, two distally). The titanium external fixator was then secured to the pins. A small incision was made in the skin distal to the tibia crest and the soft tissue was carefully retracted to visualize the bone. A single hole was manually drilled through both cortices of the mid-diaphysis, and surgical scissors were used to fracture the cortex on either side of the hole. The fibula was fractured by direct lateral pressure. The periosteum and dermal tissues were closed with a single suture. Finally, buprenex (1.0mg/kg) was given by intramuscular injection post surgery for analgesia. Distraction began three days after surgery (3 day latency) at a rate of 0.075 mm b.i.d. (0.15 mm/day) and continued for 14 days. After the distraction period, the mice were sacrificed and the distracted tibiae were harvested for radiographic and histological analyses.

Study Designs

Study 1: Effects of rmTNF on DO in WT mice

To replicate previous studies, 22 three month old C57BL/6 (WT) mice underwent placement of an external fixator and osteotomy to the left tibia. At the time of surgery an alzet pump (model 1002, Durect Corp., Cupertino, CA) was inserted subcutaneously on the back of each mouse. The mice in the control group (n=11) received vehicle (phosphate buffered saline [PBS] with 1% bovine serum albumin [BSA]) via alzet and those in the TNF treated group (n=11) received 10 ug/kg/day of rmTNF via alzet based on pre-surgery weights (R&D systems, cat. # 410-MT). Distraction began three days after surgery (three day latency) at a rate of 0.075 mm b.i.d and continued for 14 days. At sacrifice the distracted and contra lateral tibiae were harvested and trunk blood was collected for serum.

Study 2: Effects of rmTNF on R1KO mice

To determine how R1KO mice would respond to DO with or without rmTNF, 10 mice (3 month old) per group of R1KO's +/- rmTNF underwent placement of an external fixator and osteotomy to the left tibia. Ten additional three month old C57BL/6 (WT) mice were used as distraction controls. At the time of surgery an alzet pump (model 1002) was inserted subcutaneously on the back of each mouse. The mice in the vehicle groups received PBS via alzet and those in the TNF treated group received 10 ug/kg/day of via alzet. Distraction began three days after surgery at a rate of 0.075 mm b.i.d and continued for 14 days. At sacrifice the distracted and contra lateral tibiae were harvested and trunk blood was collected for serum.

Study 3: DO in R2KO & R1&2KO mice

To determine how R2KO and R1&2KO mice would respond to DO, three-four month old male C57BL/6 mice (n=11), three-four month old male R1&R2 KO mice (n=11), and three-four month old male R2KO mice (n=11) underwent placement of an external fixator and osteotomy to the left tibia. Distraction began three days after surgery at a rate of 0.075 mm b.i.d and continued for 14 days. At sacrifice the distracted tibiae were harvested and trunk blood was collected for serum.

Study 4: Effects of rmTNF on R2KO mice

To determine how R2KO mice would respond to rmTNF, three month old R2KO mice underwent placement of an external fixator and osteotomy to the left tibia. At the time of surgery an alzet pump (model 1002) was inserted subcutaneously on the back of each mouse. The mice in the control group (n=11) received vehicle (PBS with 1% BSA) via alzet and those in the TNF treated group (n=11) received 10 ug/kg/day of rmTNF via alzet. Distraction began three days after surgery at a rate of 0.075 mm b.i.d and continued for 14 days. At sacrifice the distracted and contra lateral tibiae were harvested and trunk blood was collected for serum.

Radiographic and Histological Analysis

As previously described, after 48 hours of fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin the left tibiae were removed from the fixators for high-resolution single beam radiography and subsequent histological processing. For initial radiography a Xerox Micro50 closed system radiography unit (Xerox, Pasadena, CA USA) was used at 40 kilovolts (3 mA) for 20 seconds using Kodak X-OMAT film. For quantification, the radiographs were video recorded under low power (1.25 × objective) microscopic magnification and the area of mineralized new bone in the distraction gaps were evaluated by NIH Image Analysis 1.62 software/Image J software 1.30 (rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). The measured distraction gap was outlined from the outside corners of the two proximal and the two distal cortices forming a quadrilateral region of interest. The mineralized new bone area in the gap was determined by visually outlining the regions with radiodensity equivalent to or greater than an adjacent non-bone (background) area (excluding bone chips). The percentage of new mineralized bone area within the distraction gap (percent new bone) was calculated by dividing mineralized bone area by total gap area. Therefore, the percent new bone as measured by the radiograph analysis is an estimate of new “mineralized” bone in the entire gap 13-15.

After radiography, the distracted tibiae were decalcified in 5% formic acid, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Experience in our laboratory has demonstrated that this achieves good morphology in murine orthopedic tissues and does not appear to significantly impair immunological detection of many epitopes 13, 16. Five to seven micron longitudinal sections were cut on a microtome (Leitz 1512, Wetzlar, Germany) for hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E). Sections were selected to represent a central or near central gap location. A quadrilateral region of interest was outlined and recorded as follows. Both the proximal and distal endocortical (measured from the inside corners of the cortices) and the intracortical (cortical wall included) new bone matrix was outlined together from the outside edges of the cortices, and the area was recorded as new gap bone formation. This area in an organized gap appears as interconnected bone columns originating near the marrows and elongating toward the center of the gap. A fibrous interzone usually separates bone arising from the proximal versus the distal marrow. The percentage of new gap bone area within the DO gap (percent new bone) was calculated as above. The percent new bone as measured by the histological analysis is an estimate of new gap bone formation which would include non-mineralized osteoid columns, embedded new sinusoids, and maturing mineralized bone columns 13,16-22.

To be included in the analyses the DO samples had to 1) be well aligned, 2) have no broken pin sites, 3) have few bone chips within the DO gap, 4) have an intact ankle, and 5) have had no weight loss or health problems during the distraction period.

Serum mouse TNFα Bead Array

Serum samples were run on the Luminex machine in the Pediatric Endocrinology Core Facility. The Linco mouse adipokine kits were used.

Statistics

For statistical analysis, differences between group means were determined by the Student's t test. All data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. We note that the coefficient of variation varied between 1.6 and 6.9. The lower values characterize the rmTNF sensitive mice. These values are consistent with previously published work. We note that the standard error of the means all fell between 6.6 and 3.0%, which is also consistent with our previous work in young mice. We note that in aged mice the standard error of the means can increase up to 12%.

Results

Study 1

To replicate earlier studies on the effects of rmTNF on DO, C57BL/6 mice underwent placement of an external fixator and osteotomy to the left tibia. The mice in the control group received vehicle and those in the TNF group received 10 ug/kg/day of rmT-NF. The average serum TNF concentrations at harvest confirmed administration of rmT-NF by alzet pump (TNF: 32.8 ± 1.1 pg/ml vs control: 5.4 ± 0.5 pg/ml, p<.001). No significant differences were noted in body weight gains or mean final weights (TNF: 26.05 ± 0.5 g vs control: 26.05 ± 0.4 g).

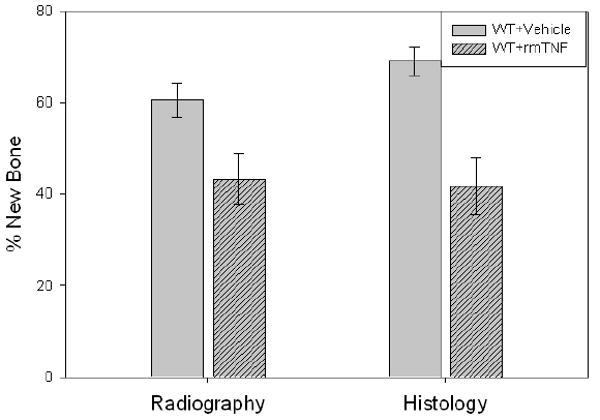

New gap bone formation after DO in rmTNF and vehicle treated mice was assessed by single beam radiography and histology. Comparison of the distracted tibial radiographs demonstrated the expected rmTNF–associated inhibition of in % new bone mineralization [TNF: 43.2% ± 5.6 vs control: 60.5% ± 3.7, p= 0.019] (Figure1). Further, analysis of histological sections supported the radiological analyses by revealing a significant decrease in new gap bone formation in rmTNF treated 41.7 ± 6.2% vs control 69.0 ± 3.0%, p< 0.001 (Figure 1). Representative H&E stained histological sections and radiographs of distracted tibial DO gaps from control and rmTNF treated mice are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

New gap bone formation after DO in rmTNF and vehicle treated mice was assessed by single beam radiography and histology. Comparison of the distracted tibial radiographs demonstrated an rmTNF–associated inhibition of in % new bone mineralization (TNF: 43.2% ± 5.6 vs control: 60.5% ± 3.7, p= 0.019). Further, analysis of histological sections supported the radiological analyses by revealing a significant decrease in new gap bone formation in rmTNF treated 41.7 ± 6.2% vs control 69.0 ± 3.0%, p< 0.001.

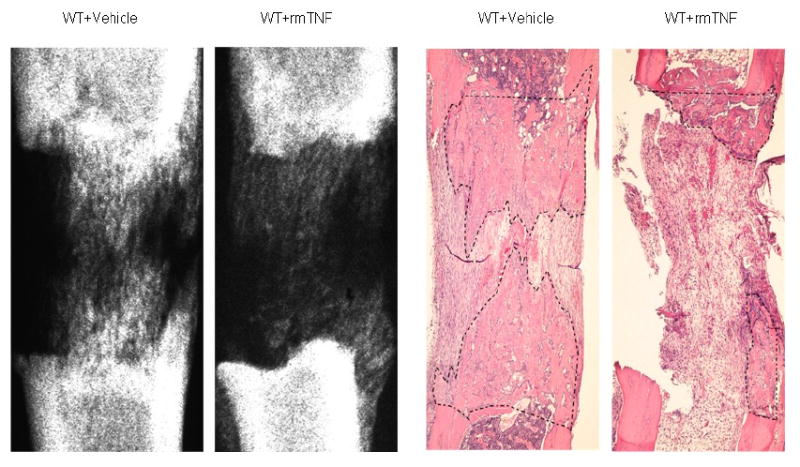

Figure 2.

Representative H&E stained histological sections and radiographs of distracted tibial DO gaps from vehicle and rmTNF treated mice are shown. The area of new gap bone formation in the histological sections is roughly outlined with dashed lines for clarification. Notice the significant reduction in the % area of new bone formation in the rmTNF specimen in comparison to the vehicle control.

Study 2

To determine how R1KO mice would respond to DO with or without rmTNF, R1KO mice underwent the standard DO protocol with the addition of the placement of alzet pumps subcutaneously mid back. C57BL/6 mice were used as distraction controls. The pumps delivered 10 ug/kg/day rmTNF or vehicle over the first 14-15 days of the 17 day distraction protocol. The average serum TNF concentrations at harvest confirmed administration of rmTNF by alzet pump (TNF: 148.4 ± 28.3 pg/ml vs R1KO vehicle: 14.7 ± 1.6 pg/ml vs WT vehicle 4.8 ± 0.7 pg/ml, p=.002). No significant differences were noted in body weight gains or mean final weights (TNF: 25.29 ± 0.4 vs R1KO vehicle: 25.54 ± 0.4 g vs WT vehicle: 25.13 ± 0.3).

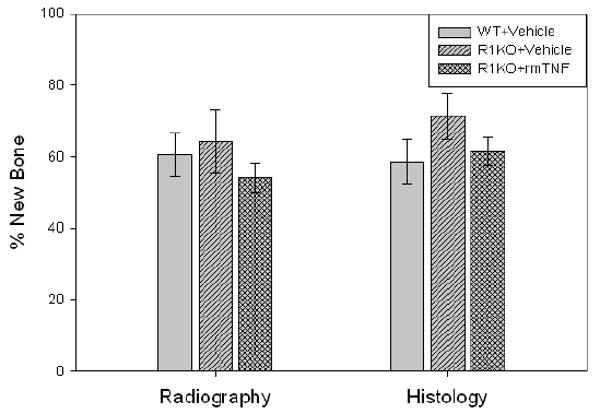

Comparison of the distracted tibial radiographs demonstrated the percent of mineralized new bone per gap was equivalent in the rmTNF treated, vehicle treated R1KO mice, and control mice (WT: 60.5% ± 6.0 vs R1KO/vehicle: 64.4% ± 8.9 vs R1KO/TNF: 54.2 ± 4.2, p=0.63) (Figure 3). Comparison of the distracted tibial histology supported the radiographic results by demonstrating no significant differences between the three groups (WT: 58.6 ± 6.3 vs R1KO/vehicle: 71.3 ± 6.6%, vs R1KO/TNF: 61.6 ± 4.0%p=0.36) (Figure 3). Representative H&E stained histological sections and radiographs of distracted tibial DO gaps from rmTNF treated, vehicle treated, and control mice are shown in Figure 4. These results suggest that TNFR1 mediates a significant portion of the rmTNF–associated inhibition of new direct bone formation in WT mice.

Figure 3.

New gap bone formation after DO in 1) rmTNF treated versus vehicle treated TNFR1 KO mice and in 2) control mice was assessed by single beam radiography and histology. Comparison of the distracted tibial radiographs demonstrated the percent of mineralized new bone per gap was equivalent in the rmTNF treated, vehicle treated R1KO mice, and control mice (WT: 60.5% ± 6.0 vs R1KO/vehicle: 64.4% ± 8.9 vs R1KO/TNF: 54.2 ± 4.2, p=0.63). Comparison of the distracted tibial histology supported the radiographic results by demonstrating no significant differences between the three groups (WT: 58.6 ± 6.3 vs R1KO/vehicle: 71.3 ± 6.6%, vs R1KO/TNF: 61.6 ± 4.0%p=0.36).

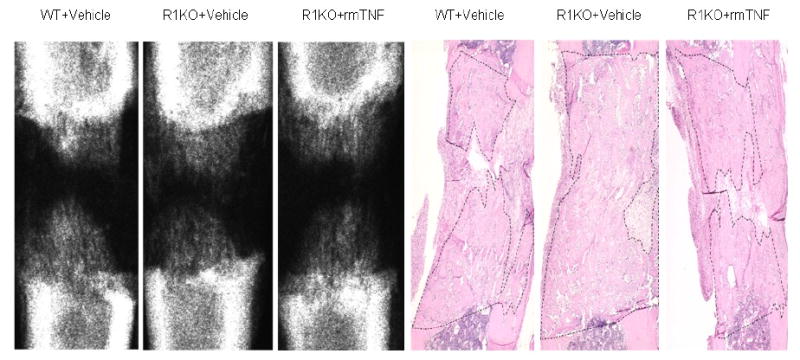

Figure 4.

Representative H&E stained histological sections and radiographs of distracted tibial DO gaps from control, vehicle treated, and rmTNF treated mice are shown. The area of new gap bone formation in the histological sections is roughly outlined with dashed lines for clarification. Notice the lack of significant changes in the % area of new bone formation among the three groups.

Study 3

To determine how R2KO and R1&2KO mice would respond to DO, C57BL/6 (WT) mice, R2KO mice, and R1&R2KO mice underwent placement of an external fixator and osteotomy to the left tibia. No significant differences were noted in body weight gains or final weights (R2KO: 24.83 ± 0.6 vs R1&2KO 25.93 ± 0.6 vs WT: 25.91 ± 0.6 g).

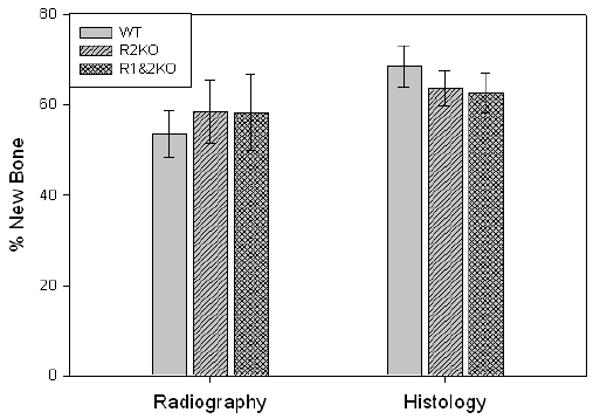

Comparison of the distracted tibial radiographs demonstrated the percent of mineralized new bone per gap was equivalent in all the groups: WT, R2KO and R1&2 KO mice (WT: 53.6% ± 5.2 vs R2KO: 58.5% ± 7.0 vs R2&1KO 58.3 % ± 8.4, p=0.85) (Figure 5). Comparison of the distracted tibial histology supported the radiographic results by demonstrating equivalent robust new gap bone formation in all groups (WT: 68.5% ± 4.6 vs R2KO: 63.5% ± 3.8, vs R2&1KO: 62.5 % ± 4.4, p=0.60) (Figure 5). Representative H&E stained histological sections and radiographs of distracted tibial DO gaps from WT, R2KO and R1&2 KO mice are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

New gap bone formation after DO in WT, R2KO and R1&2 KO mice was assessed by single beam radiography and histology. Comparison of the distracted tibial radiographs demonstrated the percent of mineralized new bone per gap was equivalent in all the groups: WT, R2KO and R1&2 KO mice (WT: 53.6% ± 5.2 vs R2KO: 58.5% ± 7.0 vs R2&1KO 58.3 % ± 8.4, p=0.85). Comparison of the distracted tibial histology supported the radiographic results by demonstrating equivalent robust new gap bone formation in all groups (WT: 68.5% ± 4.6 vs R2KO: 63.5% ± 3.8, vs R2&1KO: 62.5 % ± 4.4, p=0.60).

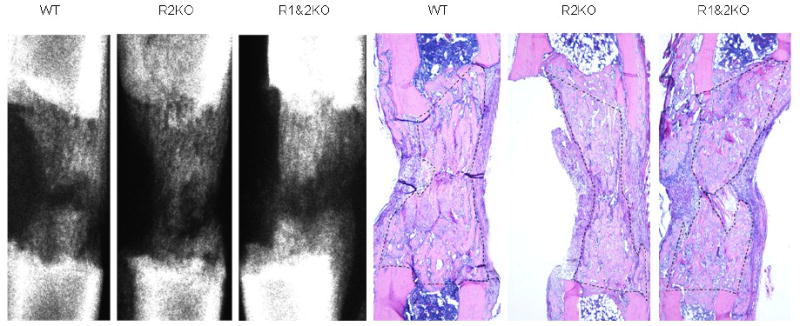

Figure 6.

Representative H&E stained histological sections and radiographs of distracted tibial DO gaps from WT, R2KO and R1&2 KO mice are shown. The area of new gap bone formation in the histological sections is roughly outlined with dashed lines for clarification. Notice the lack of significant changes in the % area of new bone formation among the three groups.

Serum TNF analyses demonstrated relatively higher endogenous levels of TNF in the R1&2 KO mice (30.2 ± 2.2 pg/ml vs WT and R2KO both below sensitivity @ < 12.2 pg/ml), which were not associated with any decrement in new bone formation.

Study 4

To determine how R2KO mice (R1 replete) would respond to rmTNF, these mice underwent placement of an external fixator and osteotomy to the left tibia. At the time of surgery an alzet pump (model 1002) was inserted subcutaneously on the back of each mouse. The mice in the control group received vehicle (PBS) and those in the TNF group received 10 ug/kg/day of rmTNF. No significant differences were noted in body weight gains or final weights (TNF: 26.78 ± 0.4 vs vehicle: 26.69 ± 0.7 g).

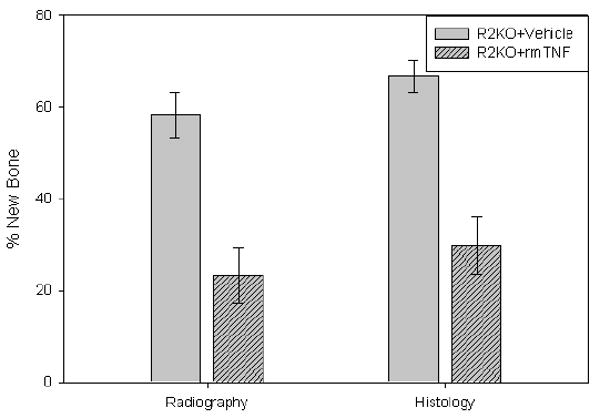

Comparison of the distracted tibial radiographs demonstrated that the percent of mineralized new bone per gap was significantly decreased in the R2KO mice treated with rmTNF vs the vehicle controls (TNF: 23.3% ± 6.2 vs vehicle: 58.3% ± 5.0, p<.001) (Figure 7). Comparison of the distracted tibial histology supported the radiographic results by demonstrating decreased new gap bone formation in the R2KO treated mice (TNF: 29.8% ± 6.3 vs vehicle: 66.9% ± 3.5, p<.001) (Figure 7). Representative H&E stained histological sections and radiographs of distracted tibial DO gaps from vehicle and rmTNF treated R2KO mice are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

New gap bone formation after DO in TNF R2KO mice treated with rmTNF vs vehicle was assessed by single beam radiography and histology. Comparison of the distracted tibial radiographs demonstrated that the percent of mineralized new bone per gap was significantly decreased in the R2KO mice treated with rmTNF vs the vehicle controls (TNF: 23.3% ± 6.2 vs vehicle: 58.3% ± 5.0, p<.001). Comparison of the distracted tibial histology supported the radiographic results by demonstrating decreased new gap bone formation in the R2KO treated mice (TNF: 29.8% ± 6.3 vs vehicle: 66.9% ± 3.5, p<.001).

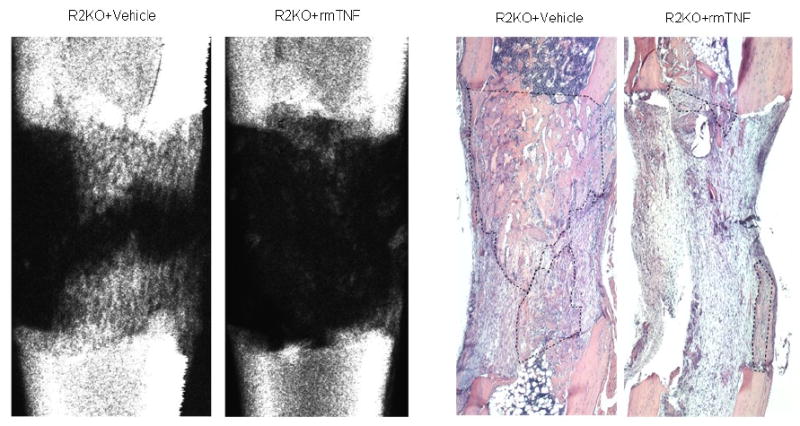

Figure 8.

Representative H&E stained histological sections and radiographs of distracted tibial DO gaps from vehicle and rmTNF treated R2KO mice are shown. The area of new gap bone formation in the histological sections is roughly outlined with dashed lines for clarification. Notice the significant reduction in the % area of new bone formation in the rmTNF specimen in comparison to the vehicle control.

The average serum TNF concentrations at harvest confirmed administration of rmTNF by alzet pump (TNF: 60.4 ± 6.7 pg/ml vs vehicle: 25.6 ± 4.5 pg/ml, p<.001). As above, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that TNFR1 mediates a significant portion of the rmTNF–associated inhibition of new direct bone formation in WT mice.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that normal expression of TNF is required for optimal bone formation, but that unregulated or excessive expression can contribute to skeletal pathology 1-5. This report demonstrates the effects of the genetic deficiency of TNFR1, TNFR2, and TNFR1&2 on DO and the effects of systemic administration of recombinant mouse TNFα (rmTNF) on new bone formation during DO in WT, R1KO, and R2KO mice. We hypothesized 1) that DO would be impaired in the R1&2 KO mice but not in the R1KO or R2KO mice, and 2) that the genetic deficiency of TNFR1 would block the osteoinhibitive effects of rmTNF, while rmTNF would inhibit direct bone formation during DO in WT and R2KO mice.

In Study 1, where the effects of rmTNF on DO in WT male mice were determined, we confirm the previously reported significant inhibition of new bone formation. Also, the lack of weight loss in the rmTNF treated mice suggests the lack of confounding nutritional effects in both the rmTNF treated mouse and rat DO models 11, 23, 24.

In Study 2 we demonstrated that bone formation during DO in mice without the TNFR1 gene is equivalent to that seen in WT mice; however, the osteoinhibitory effects of rmTNF were not seen in the R1KO mice. Also, the serum TNF levels were elevated in the R1KO mice over the WT and unusually elevated in the R1KO mice given rmTNF. This may suggest that TNFR1 is involved in normal turnover of serum TNF levels. This is consistent with a study on sepsis in mice which reported elevated serum TNF levels in both R1KO and R2KO mice 25. These results 1) implicate TNFR1 as a primary mediator in the osteoinhibitory effects of rmTNF in this model of direct bone formation, and 2) suggest that the TNFR1 is not required for accelerated direct bone formation when measured after the 17 day protocol. TNFR1 may still be required for optimal completion of various earlier stages of bone regeneration such as during initial inflammation, or resolution of the inflammation, or the development of granulation tissue; however, these results suggest that if earlier stages are delayed either redundancy, alternate contingency loops, or catch up growth occurs over the time studied. The findings that TNFR1 appears to mediate the effects of rmTNF are in agreement with in vitro studies on the inhibitory effects of TNF on the conversion of marrow stromal cells into osteoblasts 26. Another study of both intramembranous and endochondral ossification in R1KO mice demonstrated no effects on intramembranous, but stimulated endochondral bone formation 27. We note that though the bone formation during DO in the R1KO mice reported here was not significantly different from that in the WT mice, nevertheless there was a trend toward better average bone formation and the SEM was smaller in the KO mice. We speculate that with more stringent conditions (increased age, decreased latency period, increased distraction rate) we might uncover an advantage for new bone formation in R1KO mice over WT mice.

In Study 3 we demonstrated that bone formation during DO in mice without the TNFR2 gene or without both TNFR1 and R2 genes is equivalent to that seen in WT mice. The endogenous serum TNF levels were elevated in the R1&R2KO mice suggesting a state of “TNF resistance” in these mice. The result in the R1&R2KO mice might be considered to be in contrast with the previous results of marrow ablation and fracture healing in these mice 3-5. These studies demonstrated that TNF functions at several stages in these models. We note that though it is likely that the three separate bone regeneration protocols (marrow ablation, fracture healing, DO) share similar features of intramembranous bone formation; they also have distinct characteristics (i.e. continuous tension in DO only). Also as noted above, we caution that the results reported here were derived only from the 17 day end point of the DO protocol. Further time course studies involving DO in R1&2KO mice will be required to better compare the above studies with those reported here. We note that in another study muscle regeneration was compromised in R1&R2KO mice 34.

In Study 4 we demonstrate that rmTNF given during DO produced equivalent osteoinhibitory effects in R2KO mice as those seen in WT. These results are consistent with a crucial role of TNFR1 in mediating the rmTNF effects but do not rule out either 1) a less significant role for TNFR2 in increasing the sensitivity of cells to TNF as reported previously for necrosis and LPS toxicity, or 2) a protective role for TNFR2 as reported in cardiac myocytes 35-37. The possible complexity of the responses mediated by either of the TNF receptors is evident in a recent paper which studied marrow stem cells from R1KO and R2KO mice and their responses to TNF, LPS and hypoxia 38.

DO enhances demand for blood flow and does so to a greater extent than fracture healing 39. Angiogenesis appears to be crucial to both direct and endochondral bone formation 40, 41. In fact evidence suggests that angiogenesis occurs before osteogenesis in DO. This raises the questions about the effects of TNF modulation on angiogenesis. We measure the % new sinusoid area in the developing DO gap and we can identify endothelial cells immunohistochemically. In our experience in young, old, and rmTNF treated mice after 14 days of distraction, direct bone formation is always accompanied by an equivalent area of sinusoids. Therefore, in our analyses when the % new bone formation is significantly changed, this also includes an equivalent change in the sinusoidal areas. It has been demonstrated that chronic ethanol exposure both induced TNF and inhibited proliferation in endothelial cells 29. Also, in endothelial cells TNF can activate inflammatory responses and increase pathogenic angiogenesis or can inhibit proliferation and increase apoptosis 50. As TNF can inhibit Runx2 activity in osteoblasts, it may be important to note that Runx2 can also regulate endothelial cell proliferation 51. However, contradictory results have been reported in different models. In a model of skin wound healing the R1KO mice demonstrated stimulated angiogenesis 28. For example, ischemia-initiated collateral arteriogenesis and angiogenesis were enhanced in R1KO mice 30; however, in both an implant angiogenesis model 31 and an arteriogenesis model 32, vascularization was reduced in R1KO mice. In terms of angiogenesis and in contrast to the results here, two studies have agreed that angiogenesis is compromised in R2KO mice 30, 33. In future studies, we would hypothesize, based on the results presented here, that modulation of TNF during distraction affects the coupling of both osteo and angiogenesis in a similar manner.

The effects of TNF deletion on chondrocytes and osteoclasts have been studied previously 3-5. However, in this model, we do not see chondrocytes in the developed DO gap, only in the “peripheral” callus and then only sporadically. In this regard, it would be of interest to look at earlier time points, for example day 3 of latency which is essentially day 3 of fixated fracture. We would expect delays in cartilage formation at this time; however, after 14 days of distraction these effects maybe obscured by continual distraction. In regard to osteoclasts we only see Trap+ cells if the DO gap is close to bridging, and if so they appear in the medullary canal at the outside edges of the DO gap. With the distraction period and rate used here we do not routinely see osteoclasts. In future, one could include a consolidation period which would allow for measurement of the effects of modulation of TNF on osteoclasts. In regard to osteocytes, we do see osteoblasts surrounded by slowly mineralizing osteoid in woven bone but we have not considered whether they are maturing to osteocytes. Also they are subsequently removed by reformation of the medullary canal. In future, to address this question, we are planning to test antibodies to both sclerostin (SOST) and DMP-1 to see if the most mature osteoblasts could be considered osteocytes.

A number of studies have been published on the differences between TNFR1 and R2 signaling in inflammatory response models 42-46. In general, a majority of the studies agree that TNF signaling through TNFR1 mediates pro-inflammatory effects, while TNFR2 signaling can mediate anti-inflammatory and even anabolic effects.

Most fractures heal by a combination of endochondral and direct (intramembranous, appositional) bone formation. Direct bone formation forms the hard callus in fracture healing which is often responsible for the initial bridging and stabilization of the fracture. Direct bone formation in DO and fracture share many common features at the cellular and molecular levels 52. Also, it has been reported that fatigue, stress, and minimally displaced fractures all appear to heal by direct bone formation 52, 53. The results of these studies may explain the close correspondence between DO and fracture healing demonstrated in models of chronic ethanol exposure, lead exposure, diabetes, as well as in aging 6, 9, 54, 55. We note that DO is used to treat delayed union, nonunion, and infected fractures 56, 57. Therefore, we hypothesize that deficits in fracture healing involving direct bone formation in the clinic can be modeled by DO in the lab.

Blocking the TNF pathways studied here has been shown to enhance direct bone formation in mice chronically treated with alcohol 11. Most recently TNF blockers have been demonstrated to enhance direct bone formation in aged mice 58. Blockage of TNF mediated osteoinhibitory effects could also be clinically appropriate in more orthopedic cases than just those with aging or excess alcohol consumption as major risk factors. For example, TNF has been demonstrated to mediate some cases of orthopedic implant osteolysis 59. Also, recent studies demonstrate 1) that endogenous TNF lowers maximum peak bone mass in mice and inhibits osteoblastic Smad activation, 2) that blockade of TNF increased a marker of bone formation in early post-menopausal women, and 3) that elevated inflammatory markers, including TNF, are prognostic for osteoporotic fractures 47-49. In fact, it has been hypothesized that TNF antagonists may represent novel anabolic agents and the paper cited above appears to be a successful test of this hypothesis 58, 47.

In conclusion, the data suggest that osteogenesis in both rats and mice respond to rmTNF exposure in a similar manner and that this model can be used in mice to study the underlying mechansims. Further, we hypothesize that the principal osteoinhibitory effects on DO due to excess exogenous or endogenous TNF are mediated through TNFR1. These and other studies set the stage for using the ever widening array of genetically altered mouse strains to study the negative effects of rmTNF on direct bone formation during DO and fracture healing. A situation which may be common to several pathologies including rheumatoid arthritis, chronic ethanol exposure, and aging. For future studies, we postulate that chronic high rmTNF levels inhibit osteoblastogenesis at multiple stages during DO. Together, these results support future testing of pharmacological interventions that modulate TNF activities and we speculate that use of TNF blockers could become standard of care for various orthopedic procedures in several patient populations.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grant AA12223 (CKL), by NIH National Center for Research Resources Grant # 1CORR16517-01, and by Arkansas Biosciences Institute (CKL) funded by the Arkansas Tobacco Settlement Plan and administered by Arkansas Children's Hospital Research Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nanes MS. Tumor necrosis factor-α: molecular and cellular mechanisms in skeletal pathology. Gene. 2003;321:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00841-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frost A, Jonsson K, Nilsson O, Ljunggren O. Inflammatory cytokines regulate proliferation of cultured human osteoblasts. Acta Ortho Scand. 1997;68:91–96. doi: 10.3109/17453679709003987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerstenfeld L, Cho T, Kon T, Aizawa T, Cruceta J, Graves B, Einhorn T. Impaired intramembranous bone formation during bone repair in the absence of tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169:285–294. doi: 10.1159/000047893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerstenfeld LC, Cho TJ, Kon T, Aizawa T, Tsay A, Fitch J, Barnes GL, Graves DT, Einhorn TA. Impaired fracture healing in the absence of TNF-alpha signaling: the role of TNF-alpha in endochondral cartilage resorption. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1584–92. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmann W, Edgar CM, Wang K, Cho TJ, Barnes GL, Kakar S, Graves DT, Rueger JM, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA. TNF alpha coordinately regulates the expression of specific matrix metalloproteinases and angiogenic factors during fracture healing. Bone. 2005;36:300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aronson J, Gao GG, Shen X, McLaren SG, Skinner RA, Badger TM, Lumpkin CK., Jr Effect of aging on distraction osteogenesis in the rat. J Ortho Res. 2001;19:421–427. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown EC, Perrien DS, Fletcher TW, Irby DJ, Aronson J, Gao GG, Hogue WR, Skinner RA, Feige U, Suva LJ, Ronis MJJ, Badger TM, Lumpkin CK., Jr IL-1 and TNF antagonists attenuate ethanol-induced inhibition of bone formation in a rat model of distraction osteogenesis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:904–908. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.039636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holden C. Alcoholism and the medical cost crunch. Science 1987. 1987;235:1132–33. doi: 10.1126/science.3823872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perrien DS, Wahl EC, Hogue WR, Feige U, Aronson J, Ronis MJJ, Badger TM, Lumpkin CK., Jr IL-1 and TNF antagonists prevent inhibition of fracture healing by ethanol in rats. Toxicol Sci. 2004;82:656–660. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purohit V. Introduction to the alcohol and osteoporosis symposium. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:383–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wahl EC, Perrien DS, Aronson J, Liu Z, Fletcher TW, Skinner RA, Feige U, Suva LJ, Badger TM, Lumpkin CK., Jr Ethanol-induced inhibition of bone formation in a rat model of distraction osteogenesis: A role for the tumor necrosis factor signaling axis. Alcohol Clin Ex Res. 2005;29:1466–1472. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000174695.09579.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aronson J, Liu L, Liu Z, Gao GG, Perrien D, Brown E, Skinner RA, Thomas JR, Morris KD, Suva LJ, Badger TM, Lumpkin CK., Jr Decreased endosteal membranous bone formation accompanies aging in a mouse model of distraction osteogenesis. e-biomed: J Regenerative Med. 2002;3:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aronson J, Shen X, Gao GG, Miller F, Quattlebaum T, Skinner RA, Badger TM, Lumpkin CK., Jr Sustained proliferation accompanies distraction osteogenesis in the rat. J Orthop Res. 1997a;15:563–569. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aronson J, Shen X, Skinner RA, Badger TM, Lumpkin CK., Jr Rat model of distraction osteogenesis. J Orthop Res. 1997b;15:221–226. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skinner RA, Fromowitz FB. Tech Sample HT-5. ASCP Press; Chicago, Il: 1989. Faxitron X-ray unit in histologic evaluation of breast biopsies. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perrien D, Brown EC, Aronson J, Skinner RA, Montague DC, Badger TM, Lumpkin CK., Jr Immunohistochemical study of osteopontin expression during distraction osteogenesis in the rat. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:567–574. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perrien DS, Liu Z, Wahl EC, Bunn RC, Skinner RA, Aronson J, Fowlkes J, Badger TM, Lumpkin CK., Jr Chronic ethanol exposure is associated with a local increase in TNFα and decreased proliferation in the rat distraction gap. Cytokine. 2003;23:179–189. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(03)00225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skinner RA, Nicholas R. Tech Sample HT2. ASCP Press; Chicago, IL: 1990. Preparing superior quality slides of orthopedic tissue using previously decalcified material. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skinner RA, Nicholas RW, Stewart CL, Vireday C. Resected allograft bone containing an implanted expanded polytetrafluoroethylene prosthetic ligament: comparison of paraffin, glycolmethacrylate, and exakt grinding techniques. J Histotech. 1993;16:129–137. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skinner RA, Hickmon SG, Lumpkin CK, Jr, Aronson J, Nicholas RW. Decalcified bone: twenty years of successful specimen management. J Histotech. 1997;20:267–277. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wahl EC, Liu L, Perrien DS, Aronson J, Hogue WR, Skinner RA, Hidestrand M, Ronis MJJ, Badger TM, Lumpkin CK., Jr A novel mouse model for the study of the inhibitory effects of chronic ethanol exposure on direct bone formation. Alcohol. 2006a;39:159–67. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahl EC, Aronson J, Skinner RA, Lumpkin CK., Jr Brdu Tracking Of Pre-Osteoblasts In Formalin Fixed, Decalcified Regenerating Bone. J Histotechnol. 2006b;29:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashimoto J, Yoshikawa H, Takaoka K, Shimizu N, Masuhara K, Tsuda T, Miyamoto S, Ono K. Inhibitory effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha on fracture healing in rats. Bone. 1989;10:453–457. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(89)90078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wahl EC, Aronson J, Liu L, Liu Z, Perrien DS, Skinner RA, Badger TM, Ronis MJ, Lumpkin CK., Jr Chronic ethanol exposure inhibits distraction osteogenesis in a mouse model: role of the TNF signaling axis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;220:302–10. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebach DR, Riehl TE, Stenson WF. Opposing effects of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and 2 in sepsis due to cecal ligation and puncture. Shock. 2005;23:311–8. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000157301.87051.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert LC, Rubin J, Nanes MS. The p55 TNF receptor mediates TNF inhibition of osteoblast differentiation independently of apoptosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E1011–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00534.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukic IK, Grcevic D, Kovacic N, Katavic V, Ivcevic S, Kalajzic I, Marusic A. Alteration of newly induced endochondral bone formation in adult mice without tumour necrosis factor receptor 1. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;139:236–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori R, Kondo T, Ohshima T, Ishida Y, Mukaida N. Accelerated wound healing in tumor necrosis factor receptor p55-deficient mice with reduced leukocyte infiltration. FASEB J. 2002;16:963–74. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0776com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luedemann C, Bord E, Qin G, Zhu Y, Goukassian D, Losordo DW, Kishore R. Ethanol modulation of TNF-alpha biosynthesis and signaling in endothelial cells: synergistic augmentation of TNF-alpha mediated endothelial cell dysfunctions by chronic ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:930–8. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171037.90100.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo D, Luo Y, He Y, Zhang H, Zhang R, Li X, Dobrucki WL, Sinusas AJ, Sessa WC, Min W. Differential functions of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and 2 signaling in ischemia-mediated arteriogenesis and angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1886–98. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barcelos LS, Talvani A, Teixeira AS, Vieira LQ, Cassali GD, Andrade SP, Teixeira MM. Impaired inflammatory angiogenesis, but not leukocyte influx, in mice lacking TNFR1. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:352–8. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1104682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoefer IE, van Royen N, Rectenwald JE, Bray EJ, Abouhamze Z, Moldawer LL, Voskuil M, Piek JJ, Buschmann IR, Ozaki CK. Direct evidence for tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling in arteriogenesis. Circulation. 2002;105:1639–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014987.32865.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goukassian DA, Qin G, Dolan C, Murayama T, Silver M, Curry C, Eaton E, Luedemann C, Ma H, Asahara T, Zak V, Mehta S, Burg A, Thorne T, Kishore R, Losordo DW. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor p75 is required in ischemia-induced neovascularization. Circulation. 2007;115:752–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.647255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen SE, Gerken E, Zhang Y, Zhan M, Mohan RK, Li AS, Reid MB, Li YP. Role of TNF-{alpha} signaling in regeneration of cardiotoxin-injured muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C1179–87. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00062.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erickson SL, de Sauvage FJ, Kikly K, Carver-Moore K, Pitts-Meek S, Gillett N, Sheehan KC, Schreiber RD, Goeddel DV, Moore MW. Decreased sensitivity to tumour-necrosis factor but normal T-cell development in TNF receptor-2-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;372:560–3. doi: 10.1038/372560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Defer N, Azroyan A, Pecker F, Pavoine C. TNFR1 and TNFR2 signaling interplay in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2007 Oct 2; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704003200. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monden Y, Kubota T, Inoue T, Tsutsumi T, Kawano S, Ide T, Tsutsui H, Sunagawa K. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is toxic via receptor 1 and protective via receptor 2 in a murine model of myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H743–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00166.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markel TA, Crisostomo PR, Wang M, Herring CM, Meldrum DR. Activation of individual tumor necrosis factor receptors differentially affects stem cell growth factor and cytokine production. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G657–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00230.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tay B, Le A, Gould S, Helms J. Histochemical And Molecular Analyses Of Distraction Osteogenesis In A Mouse Model. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:636–642. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carvalho R, Einhorn T, Lehmann W, Edgar C, Al-Yamani A, Apazidis A, Pacicca D, Clemens T, Gerstenfeld L. The Role Of Angiogenesis In A Murine Model Of Distraction Osteogenesis. Bone. 2004;34:849. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Towler DA. The osteogenic-angiogenic interface: novel insights into the biology of bone formation and fracture repair. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6:67–71. doi: 10.1007/s11914-008-0012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amar S, Van Dyke TE, Eugster HP, Schultze N, Koebel P, Bluethmann H. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced cutaneous necrosis is mediated by TNF receptor 1. J Inflamm. 19951996;47:180–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Modzelewski B. Soluble TNF p55 and p75 receptors in the development of sepsis syndrome. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2003;14:69–72. Review. Polish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masli S, Turpie B. Anti-inflammatory effects of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha are mediated via TNF-R2 (p75) in tolerogenic transforming growth factor-beta-treated antigen-presenting cells. Immunology. 2009;127:62–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hussain Mian A, Saito H, Alles N, Shimokawa H, Aoki K, Ohya K. Lipopolysaccharide-induced bone resorption is increased in TNF type 2 receptor-deficient mice in vivo. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26:469–77. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0834-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Wang M, Abarbanell AM, Weil BR, Herrmann JL, Tan J, Novotny NM, Coffey AC, Meldrum DR. MEK mediates the novel cross talk between TNFR2 and TGF-EGFR in enhancing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion from human mesenchymal stem cells. Surgery. 2009;146:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Y, Li A, Strait K, Zhang H, Nanes MS, Weitzman M. Endogenous TNFalpha Lowers Mazimum Peak Bone Mass and Inhibits Osteoblastic Smad Activation Through NF-kappaB. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:646–55. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Charatcharoenwitthaya N, Khosla S, Atkinson E, McCready L, Riggs B. Effect of Blockade of TNF-alpha and Interleukin-1 Action on Bone Resorption in Early Postmenopausal Women. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:724–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cauley J, Danielson M, Boudreau R, Forrest K, Zmuda J, Pahor M, Tylavsky F, Cummings S, Harris T, Newman A. Health ABC Study. Inflammatory Markers and Incident Fracture Risk in Older Men and Women; the Health Aging and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1088–95. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kishore R, Qin G, Luedemann C, Bord E, Hanley A, Silver M, Gavin M, Yoon Ys, Goukassian D, Losordo DW. The Cytoskeletal Protein Ezrin Regulates Ec Proliferation And Angiogenesis Via TNF-Alpha-Induced Transcriptional Repression Of Cyclin A. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1785–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI22849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiao M, Shapiro P, Fosbrink M, Rus H, Kumar R, Passaniti A. Cell Cycle-Dependent Phosphorylation Of The Runx2 Transcription Factor By Cdc2 Regulates Endothelial Cell Proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7118–28. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silva MJ, Touhey DC. Bone formation after damaging in vivo fatigue loading results in recovery of whole-bone monotonic strength and increased fatigue life. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:252–61. doi: 10.1002/jor.20320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wohl GR, Towler DA, Silva MJ. Stress fracture healing: fatigue loading of the rat ulna induces upregulation in expression of osteogenic and angiogenic genes that mimic the intramembranous portion of fracture repair. Bone. 2009;44:320–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ronis MJJR, Aronson J, Gao GG, Hogue WR, Skinner RA, Badger TM, Lumpkin CK., Jr Skeletal effects of developmental lead exposure in rats. Toxicol Sci. 2001;62:321–329. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/62.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thrailkill KM, Liu L, Wahl EC, Bunn RC, Cockrell GE, Perrien DS, Skinner RA, Fowlkes JF, Aronson J, Lumpkin CK., Jr Bone formation is impaired in a model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:2875–2881. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanellopoulos AD, Soucacos PN. Management of nonunion with distraction osteogenesis. Injury. 2006;37 1:S51–5. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jain AK, Sinha S. Infected nonunion of the long bones. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;431:57–65. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000152868.29134.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wahl EC, Aronson J, Liu L, Fowlkes JL, Thrailkill KM, Bunn RC, Skinner RA, Miller MJ, Cockrell GE, Clark LM, Ou Y, Isales CM, Badger TM, Ronis MJ, Sims J, Lumpkin CK. Restoration of Regenerative Osteoblastogenesis in Aged Mice: Modulation of TNF. J Bone Miner Res. 2009 Jul 6; doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090708. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Merkel KD, Erdmann JM, Mchugh KP, Abu-Amer Y, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Mediates Orthopedic Implant Osteolysis. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:203–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65266-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]