Abstract

Electrical stimulation is emerging as a viable alternative for epilepsy patients whose seizures are not alleviated by drugs or surgery. Its attractions are temporal and spatial specificity of action, flexibility of waveform parameters and timing, and the perception that its effects are reversible unlike resective surgery. However, despite significant advances in our understanding of mechanisms of neural electrical stimulation, clinical electrotherapy for seizures relies heavily on empirical tuning of parameters and protocols. We highlight concurrent treatment goals with potentially conflicting design constraints that must be resolved when formulating rational strategies for epilepsy electrotherapy: namely seizure reduction versus cognitive impairment, stimulation efficacy versus tissue safety, and mechanistic insight versus clinical pragmatism. First, treatment markers, objectives, and metrics relevant to electrical stimulation for epilepsy are discussed from a clinical perspective. Then the experimental perspective is presented, with the biophysical mechanisms and modalities of open-loop electrical stimulation, and the potential benefits of closed-loop control for epilepsy.

Keywords: Epilepsy, seizure, electrical stimulation, control, electrotherapy, strategy, cognitive impairment, efficacy, safety, treatment marker, surrogate

The created universe carries the yin at its back

and the yang in front;

Through the union of the pervading principles it

reaches harmony.

- from the Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, an increasing number of clinical studies have looked to electrical stimulation as a viable option for treating medically refractory epilepsy, probably because of: 1) Its perceived flexibility, including the ability to customize, reverse, and adapt treatment; 2) The impression that it is less invasive than resective surgery; and 3) The potential for specifically targeting pathological neural function beyond just a functional lesion of an anatomical target. The mechanisms of electrotherapy may be distinct from those of pharmacotherapy, and therefore of potential benefit for patients with intractable seizures; more so due to the absence of iatrogenic side-effects commonly observed with antiepileptic drugs. However, the ability to design rational strategies for epilepsy electrotherapy that take advantage of these features requires an appreciation of: 1) The etiology and pathophysiology of epilepsy; 2) The mechanisms by which electrical stimulation interacts with the nervous system and modulates function at the cellular, synaptic, and network level; and 3) The spectrum of potential hazards associated with electrical stimulation, and the limitations of the stimulation hardware. These aspects are intimately related on multiple levels, and the tensions within and across these levels—likened here to “yin-yang” interactions1—must be considered both in the big picture and in our individual pursuits toward electrotherapy design.

In this article, we do not attempt to provide an introduction to epilepsy control2,3,4,5,6, or a historical review and critique of various approaches7. Instead, we identify central challenges in the rational electrical treatment of epilepsy through different lenses summarized by the questions: 1) What are seizures and what does it mean to control them? 2) What does electrical stimulation do to neural tissue? and 3) What are the side-effects, instrumentation requirements, and safety limitations? Successful therapy depends on understanding and addressing these questions, and recognizing that they jointly determine treatment constraints.

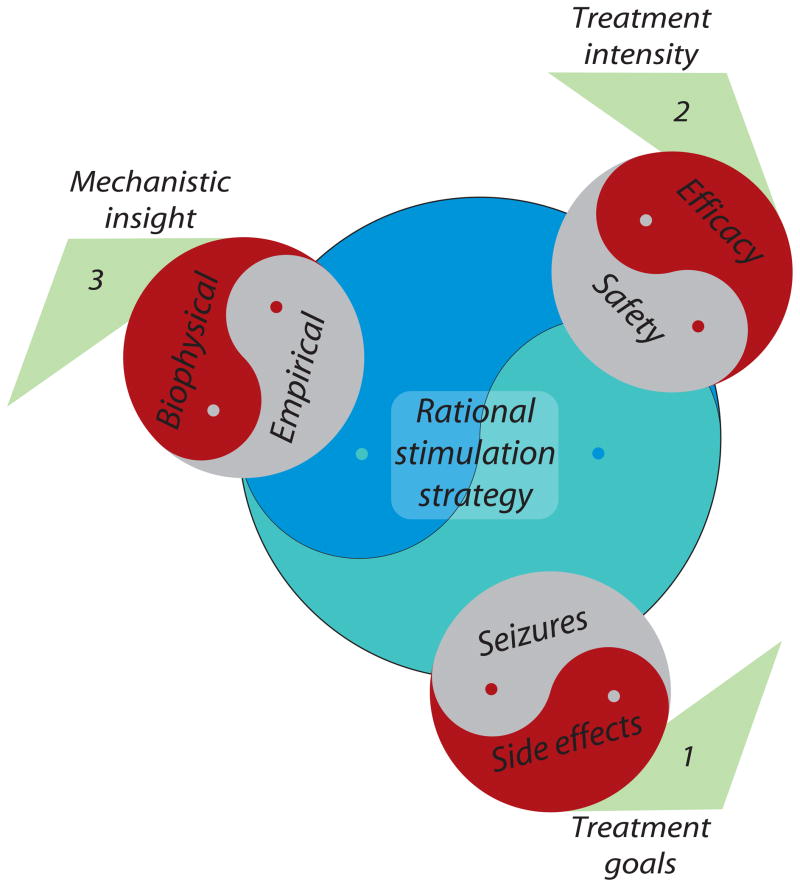

The principal considerations in the electrical treatment of epilepsy and their interrelationships may be visualized using a pinwheel structure (Figure 1) with the desired goal, an optimal strategy for electrical stimulation, at its center informed collectively by three conceptual blades. Each blade is double-edged, and symbolizes: (1) alleviation of seizures (or related dynamical markers) by stimulation, but accompanied by potentially adverse effects on cognition and behavior; (2) more effective treatment achieved by increasing stimulation invasiveness and intensity, but with an elevated risk of tissue damage; and (3) the disconnect between clinical trials, in which empirical selection of stimulation parameters is still the norm, and insight into the biophysical effects of stimulation derived from basic research studies, particularly those performed at the cellular and small network levels. The careful resolution of these various conflicts—yin-yang design—is essential for turning the wheel of therapy firmly toward the rational treatment of epilepsy.

Figure 1. Pinwheel of rational electrotherapy.

Conflicting design factors related to (1) treatment goals, (2) treatment intensity, and (3) mechanistic insight, depicted here as yin-yang interactions, that must be resolved in the formulation of a rational electrical stimulation strategy for the treatment of epilepsy.

In the absence of a comprehensive biophysical understanding of these factors, clinical efforts at electrical epilepsy treatment (reviewed by Sun et al.8; Krauss and Koubeissi9; Pollo and Villemure10; Benabid11) utilize stimulation technology and protocols that are largely empirically derived, and usually adapted from approaches to treat disparate conditions such as movement disorders. Conversely, in animal and computational studies, the effects of electrical stimulation on seizures have been studied at the cellular and network level often without appropriate regard for practical clinical factors. This review outlines some considerations required to bridge these endeavors and move the field toward a more integrated design of electrical seizure control systems. Indeed, the need to articulate such information comes in part from our own experience and naiveté in attempting to contribute on the biophysical side, often with blinders to some of the broader issues involved in a whole system solution.

2. Clinical aspects of epilepsy and objectives for electrotherapy

2.1 Seizures and epilepsy

What are seizures?

Epilepsy is characterized by recurrent episodes of paroxysmal neural discharge known as seizures. The seizures themselves are events in which normal behavior may be altered, and cognitive control or consciousness seized or taken away. Electrical recordings of brain activity—electroencephalograms (EEG)—during seizures often have stereotypical, abnormally large amplitude rhythmic patterns. The cause of seizures is commonly attributed to an “imbalance in excitation and inhibition” leading to “hyperexcitable” and “hypersynchronous” neuronal activity (see reviews by Engel12, Scharfman13, and Jefferys14) though more nuanced alternative hypotheses based on single cell electrophysiological recordings have been proposed15,16. It is recognized that human epilepsy reflects a constellation of disorders, with different underlying pathophysiologies and anatomical foci.

Seizures are a symptom of epilepsy, which has many possible etiologies: genetic abnormalities17, channelopathies18, hippocampal sclerosis19, traumatic brain injury20, and glial dysfunction21, to name a few. The combination of etiology, medical history and the part(s) of the brain affected can give rise to different epilepsy syndromes and seizure types. Apart from seizures, important consequences or comorbidities of epilepsy include cognitive impairment, depression, loss of work or driving privileges, and sleep disorders. Notwithstanding these factors, alleviation of seizures is almost always the primary endpoint of treatment (see 2.2).

The existence of a preseizure state has been postulated. Although the search for this preseizure state—the subject of many clinical and laboratory investigations—is yet to bear edible fruit22, it brings into focus the first main aspect of the rational electrotherapy design process that must be addressed: Epilepsy is the manifestation of a highly complex dynamical system, and seizures constitute but one of many states that the system occupies. We must ask, with what aspect of the dynamic do we intend to interact; what control laws should be used to achieve what dynamical objectives; and with what aspects do we directly or collaterally interact? These questions are especially relevant to the timing of therapy if, for instance, stimulation does not suppress an ongoing seizure but is effective when applied prior to seizure initiation.

2.2 Prerequisites for rational electrotherapy

Rational electrotherapy involves the control or titration of stimulation dosage based on a meaningful assessment of stimulation outcome—the focus of this section—and an understanding of stimulation tools and mechanisms, which we address in section 3.

The following considerations apply for rational quantitative assessment and improvement of clinical treatment: 1) Identification of a treatment marker(s), that is, the symptom, event or condition that is the focus of treatment, with associated performance goals in the form of an endpoint and/or cost function, where achieving these endpoints is the treatment objective; and 2) Formulation of treatment metrics, that is, suitable behavioral/physiological measures for use in programming and evaluating treatment that quantify relevant features of the treatment marker(s). These requirements are equally relevant to translational animal studies.

2.2.1 Treatment markers and objectives

Without question, the primary treatment marker or event of interest in epilepsy therapy is the seizure. The primary objective is the reduction of seizure frequency and severity, particularly clinical seizures.

Nevertheless, the question of what aspect of seizure dynamics should be targeted and how to interact with it is critical and non-trivial. For example, what are the consequences of modifying seizure intensity, duration or spread when complete suppression is not practical? When an epileptiform event has started or is imminent, how do we know that it will spread and become clinical? What are the consequences of treating subclinical—i.e., purely electrographic—events? How much stimulation is safe, and when should such limited resources be committed? Seizures often have distinct stages from onset to generalization23. Secondarily generalized seizures may offer some lead time before activity spreads across brain hemispheres. Is it then enough to prevent generalization without actually aborting a seizure? Is it acceptable to limit seizures to simple partial events, stopping them before they impair consciousness and/or motor control? These are factors to be considered when interacting directly with seizures through electrical stimulation.

Patients with pharmacoresistant epilepsy are often stressed artificially (sleep deprivation, drug taper) during invasive monitoring for evaluation of possible surgery to induce observable seizures. Even so, a typical recording period (2–14 days) may yield only a few seizures; outside the clinic the seizure rate is still lower. Stimulation studies require many parameters such as electrode location, waveform, frequency and amplitude to be tuned. Seizures are too infrequent in an acute clinical setting for parameters to be optimized on the basis of seizure yield for an individual24. This makes seizures—certainly those with overt behavior, which are less frequent—an impractical marker for treatment optimization.

It may be more convenient to choose a surrogate marker, a targeted event that is more readily available than seizures, and correlates reliably with seizure incidence or severity. Specifically, treatment-induced changes in the surrogate marker must meaningfully predict changes in the primary treatment marker. Only if such a predictive relationship is established is it possible for control of the surrogate marker to lead to seizure control, the primary treatment objective. Moreover, the rate at which treatment parameters are optimized is enhanced since the surrogate marker enables more frequent assessment of efficacy. Many electrophysiological markers of epilepsy are possible candidates for the surrogate marker: fast ripples, interictal spikes, preictal states, etc. Surrogates may also be derived through active probing such as with test pulses intended to evaluate brain state rather than control seizures25,26,27.

A surrogate marker that effectively tracks changes in seizure incidence or severity (primary objective) resulting from stimulation need not have any specific a priori relationship with seizure incidence or severity in the absence of stimulation. That is, a surrogate marker useful for dose titration may not be appropriate for seizure diagnosis. Nonetheless, markers used in seizure diagnosis are reasonable candidates for surrogate treatment markers: interictal spikes (IISs28) and high frequency oscillations (HFOs29) are both being investigated as markers of epileptogenic foci to predict surgical outcome in pharmacoresistant epilepsy. It seems plausible that electrical modulation of IISs or HFOs would affect a patient’s seizures as well. Although this is speculation, it illustrates how a surrogate marker could help achieve the primary goal of seizure reduction. But first, the validity of the surrogate must be firmly established through animal and clinical trials.

The notion of a preseizure or preictal state presents yet another option. The seizure prediction community has attempted—through the analysis of EEG—to identify such abnormal states, which could serve as surrogate markers to prevent or anticipate seizures. However, seizure prediction algorithms based on this premise have not withstood rigorous validation30 and are prone to false predictions. One alternative interpretation of the high false prediction rate is that a seizure-permissive state always precedes seizures but can also occur at other times without transitioning to seizure31.

Interestingly, such false predictions are sometimes correlated with time of day or the patient’s state of vigilance32,33. It is well established that in some epilepsies, certain normal states of vigilance are more conducive to seizure than others34,35,36. Seizure recurrence is also correlated with physiological rhythms24,37 and drug taper38.

As outlined in section 3.3, if an identifiable state can reliably predict seizures, it could serve as a treatment marker for closed-loop stimulation designed to avoid this preictal or seizure-permissive state, or to force a transition back to baseline to achieve a therapeutic effect.

Performance criteria/objectives specified for control of the surrogate marker and used for treatment optimization must go hand in hand with pre-specified primary treatment objectives: successful control of the surrogate is irrelevant unless seizure alleviation is accomplished. It is particularly interesting to consider in what way seizure dynamics may be affected by applying treatment based on a preseizure or seizure-permissive surrogate marker. Finally, whether we choose to titrate electrotherapy dose based on seizure control objectives (primary marker) or through surrogate markers, the event must be detectable with adequate accuracy to enable and optimize treatment.

It is evident that the first requirement for rational electrotherapy design, the selection of the targeted marker and specification of a corresponding treatment objective, involves considerations beyond that of simply reducing or alleviating seizures alone. The most relevant aspects and dynamics of seizures that constitute the stimulation target must be identified (primary marker and objective), and suitable surrogate markers considered for the titration and optimization of stimulation dose. Moving onward, the objective assessment of therapy requires quantitative and physiologically relevant metrics, the topic of the following section.

2.2.2 Treatment metrics

Treatment metrics are measures, typically derived from clinical observations or physiological measurements, that are either sensitive to the occurrence of a treatment marker (primary or surrogate) or descriptive of the marker’s salient characteristics (e.g., recurrence rate, duration, severity) in a way that is useful for treatment evaluation: we will apply the terms detection metric and evaluation metric respectively to distinguish the two in the following discussion.

Seizure frequency and severity are the principal evaluation metrics used in epilepsy therapy. In clinical practice, treatment evaluation is commonly based on patient reports, which are at best, self-reported seizure diaries. The metric of clinical seizure frequency derived from patient reports is inherently inaccurate, does not include subclinical events, and provides at most a qualitative and subjective description of seizure severity. Many other sources of error in patient-reported seizures are discussed by Litt and Krieger39.

When physiological monitoring is available, automated metrics are preferred. An automated metric is derived from recordings such as neuronal action potentials (spikes), EEG, extracellular pH, temperature, intracranial pressure, blood oxygen, etc.; either as raw data or by mathematical manipulation of a measurement (signal processing algorithms). A good clinical treatment metric enables accurate detection (verified against ground truth, usually human expert scores) of the treatment marker, and/or quantifies relevant features of the marker for evaluating and optimizing treatment outcome (e.g., effect of stimulation amplitude on seizure duration).

Let us first discuss the role of detection metrics in treatment marker detection. Seizures, the primary marker, are most commonly detected by filtering the EEG signal on the basis of spectral content or morphology so as to retain mostly epileptiform activity, and comparing the output to baseline (seizure-free) EEG activity; this contrast then reflects the relative “seizure content” of the EEG40,41 and constitutes a detection metric. The filtered signal may be decimated or filtered further to produce a smooth output; when this metric crosses a preselected threshold it marks the onset of a seizure. The filter may be tuned specifically to respond to the seizure onset characteristics, thereby improving early seizure detection42,43. A duration constraint may be applied to the detector output to ignore brief interictal events (e.g., polyspikes) that share the onset characteristics of true seizures—the marker of interest here—but are deemed irrelevant for triggering or evaluating treatment. Before deployment in a real-time application, the detection parameters (threshold, minimum duration, filter coefficients) may be manipulated to construct a receiver operating characteristic (ROC). In ROC analysis the detector’s sensitivity, i.e., the proportion of true events correctly identified, are compared against its specificity, a measure of the proportion of false detections avoided, as a function of one or more detection parameters. These parameters are then optimized to strike a balance between sensitivity and specificity. A detector with good sensitivity and specificity is critical for a closed-loop seizure control system. A poor detector would prompt indiscriminate stimulation. The trade-off between sensitivity and specificity depends on the cost of uncontrolled seizures versus the cost/side-effects of stimulation in the absence of a seizure. When surrogate markers (e.g., HFOs, seizure-permissive states) are employed, the cost of surrogate detection errors must be weighed in proportion to the ultimate effects on the primary marker, i.e., changes in seizure activity.

Once a detectable treatment marker has been selected, how should the effect of treatment be evaluated? Clinical evaluation metrics are needed to accurately quantify the marker’s features: for example, seizure frequency (i.e., detection rate), intensity, duration and spread. The duration and severity of the post-ictal recovery period may also be of interest as clinical evaluation metrics: for instance, anecdotal results suggest that these may be improved by vagus nerve stimulation44.

Since a good detection metric is, by definition, sensitive to the presence of the treatment marker of interest, it seems logical that it could then be manipulated to derive secondary measures that serve as treatment evaluation metrics. When seizures are targeted, the rate at which the detection metric repeatedly crosses a preset threshold value gives the seizure frequency, and the duration that it stays above the threshold for each event gives the seizure duration: two evaluation metrics derived from a single detection metric. Nevertheless, a good detection metric is not necessarily suited for treatment evaluation, and vice versa. For example, a metric specifically attuned to seizure onset facilitates early seizure detection and therefore closed-loop stimulation, but may be insensitive to later stages of seizure and therefore underestimates the seizure duration, a useful metric for assessing treatment effect. It may also produce poor contrast between brief interictal events and true seizures, the differentiation of which is important in treatment evaluation. Hence, different metrics may be desirable for marker detection and marker quantification.

A detection metric that exceeds the detection threshold for the entire seizure could be used to quantify seizure intensity and duration. The number of recording contacts that detect the seizure captures its spread. A combination of intensity, duration and spread often suffices to convey seizure severity and distinguish between different events such as interictal discharges, complex partial seizures and generalized seizures; but may not capture subtle effects, for instance neural entrainment45 or phase resetting46 achieved by tuning stimulation parameters. Also important is the ability to quantify behavioral or motor manifestations of seizure. Other descriptive dynamical metrics47,23 may be derived from studies that relate computational models to experimental observations of seizure dynamics.

Similar considerations apply to surrogate markers such as HFOs and IISs. Methods must be available for accurate marker detection and quantification using clinical metrics with high sensitivity and specificity, and enable the titration of stimulation parameters that have graded effects on the marker’s characteristics.

2.3 Considerations for rational treatment design

2.3.1 Collateral effects of treatment

Although the goal of electrotherapy is to prevent the impairment associated with certain types of seizures, electrical stimulation itself has the capacity to overwrite or overwhelm the information processing in the brain in ways that may be undesirable. For any therapy, the side effects should be minimized or at least be less intrusive than the morbidity to be controlled. Apart from potentially adverse collateral effects of stimulation on behavior and cognition, implant damage must be considered when designing electrode configurations and implant trajectories. Charge passing capacity and electrochemical considerations add additional constraints, as do battery life, ease of repair, thermal effects, and processor limitations. These translational design factors are generally not adequately addressed in computational and animal studies. Simultaneously, due in part to practical regulatory and safety concerns limiting innovation, many clinical technologies appear not to “intelligently” factor in the full range of safety concerns, nor do clinical therapeutic approaches draw on design strategies optimized in basic research studies. In this review, we emphasize that all the above considerations are integrated and often antagonistic: there is no ‘free lunch’ in epilepsy electrotherapy.

Balancing therapeutic effect and behavioral change

First yin-yang of epilepsy electrotherapy

Successful epilepsy therapy strikes a balance between seizure control and the disruption of cognitive function or mood (side effects). Given that the same neuronal networks and systems are often responsible for both, in the absence of a simple magic bullet for pathological activity, intelligent and rational therapy approaches must consider effects on both pathological and normal brain functions.

In the cautionary tale, Terminal Man48, a patient is implanted with a closed-loop electrical stimulation device to control his seizures, which are accompanied by violent psychosis. In an (un)expected twist, the patient experiences pleasurable sensations during stimulation; he quickly learns to auto-induce seizures and thereby repeatedly activates his stimulator. The adverse effects of repeated seizures and stimulation complement the patient’s preexisting paranoia, with disastrous consequences. This story was inspired in part by the discovery49 in the 1950s that rats become addicted to self-stimulation of their nucleus accumbens, which activates the dopamine pleasure pathway of the brain.

It is hard to imagine an electrical therapy which, though sufficient to alter the progress of an electrical seizure in a brain region, does not in any manner interrupt or modify normal function in the same neuronal population. Such modifications of normal brain function are an inevitable side effect, and may be subclinical or perhaps seem minor compared to the disruption caused by the seizures themselves; nonetheless it is important to recognize them as a limitation of epilepsy electrotherapy. This is also true of pharmacological and surgical approaches. Behavioral side-effects could be produced as a direct result of electrical stimulation, or indirectly, for example via control of seizures, a debated phenomenon known as paradoxical or “forced” normalization50. However electrical stimulation, by virtue of its flexibility (choice of waveform parameters), reversibility (the ability to turn it off), and potential for closed-loop implementation, offers a unique opportunity to optimize the first yin-yang aspect.

The clinical endpoint of epilepsy treatment should be relief from seizures without discomfort, comorbidity, cognitive impairment, or adverse effects on behavior. Adverse effects noted in instances of long-term deep brain stimulation (DBS) for Parkinson’s disease have included depression, aggression, psychosis and even suicidal tendency51. Pronounced mood and cognitive changes—anorexia, lethargy, hallucinations, paranoid ideation, decline in verbal and visual memory task performance—have been observed during titration of thalamic DBS parameters for epilepsy52,53. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), an FDA-approved treatment for intractable epilepsy that has shown some promise in seizure reduction, is sometimes associated with throat pain, tingling sensations or shortness of breath, and may have long-term effects on sleep54. VNS may also have a beneficial effect on mood, and its use for the treatment of depression is being debated55,56.

Pronounced effects are usually dealt with by manipulating stimulation parameters. Although uncontrollable pronounced effects occur only in a minority of patients undergoing electrical stimulation, undoubtedly a larger number may experience undocumented cognitive, functional or behavioral impairment at some (subclinical) level57,58. What is not actively monitored will remain unquantified.

Seizure reduction must be balanced against alterations in cognition, sleep disturbances, discomfort, and other effects. Management of behavior and cognition is mainly done during hospital visits through functional and psychological evaluation. Although due effort is made to assess changes in behavior and cognition following implantation, inpatient evaluations are naturally intermittent and not conducted in the patient’s normal environment. This may be remedied through functional testing and automated baseline state of vigilance monitoring. State of vigilance for humans59 or animals60,61 is typically determined using EEG criteria in conjunction with auxiliary measurements (e.g., EMG, EOG, or accelerometers) to improve discriminative performance.

Automatic sleep and behavioral staging works reasonably well, but has limitations: (1) Performance is training-dependent, i.e., limited by the subjectivity inherent in human scoring; (2) Signal quality, noise and other characteristics of a state can change over time in response to physiological or external processes; and (3) Conventional sleep scoring guidelines (Rechtschafen and Kales) for polysomnograms from human EEG do not readily translate to individuals with epilepsy62 where epileptiform activity can confound the diagnosis of normal sleep states. Natural definitions of states of vigilance, relatively independent of subjective human interpretation, must be identified for use in epilepsy along with computational models to track dynamical changes in behavior over time in continuous, chronic monitoring.

Future effort at chronic management of epilepsy using implanted stimulators must be directed toward continuous and automated systems that integrate behavioral monitoring with electrical stimulation. Metrics that quantify behavior and cognition on a regular basis63 must be derived for balancing seizure alleviation against potential behavioral impairment caused by electrical stimulation. This will make possible an integrated quantitative strategy for treatment optimization that balances seizure alleviation with collateral neuropsychological effects.

Some comments on safety and tissue damage

Second yin-yang of epilepsy electrotherapy

The desire to interface with the nervous system as directly as possible by increasing spatial specificity of action (focality) is accompanied by an increase in the potential for tissue damage (invasiveness). A comprehensive understanding of the potential mechanisms of damage is thus as critical to designing effective stimulation as understanding the therapeutic mechanisms.

Tissue Damage

There are five generally recognized mechanisms for potential tissue damage involved in electrotherapy: electrochemical, thermal, mechanical, electroporation, and excitotoxicity. Each mechanism must be addressed independently for any technology. For rational and safe electrotherapy two points need to be emphasized: Firstly, existing safety data for the many potential mechanisms of damage are incomplete; nor can general safety metrics (e.g. charge per phase, current density, etc.) be extrapolated across distinct applications/technologies64. For example, electrochemical safety data from rat cortex for a particular waveform does not necessarily extend to human deep brain stimulation using a different waveform. Secondly, distinct safety criteria may need to be established for interaction with epileptic tissue, especially given that safety data for normal tissue is itself insufficient.

Though each stimulation technology is associated with a particular set of risks and complications, the following generality summarizes the second yin-yang balance as it relates to stimulation electrode location: Electric fields decay rapidly with distance, in units of the electrode size, from the electrode. Therefore, for spatial specificity, it is desirable to be (implanted) close to the target. But increased invasiveness also increases risk of damage and reduces flexibility. Conversely, as the stimulation electrode is placed further away from the target region, for example to the periphery or skin, the risk of tissue damage nominally decreases but spatial specificity is compromised. Thus, the potential to electrically interact with other brain regions and interfere with normal brain function increases. In this last aspect, our first yin-yang, the balance between seizure control and undesired cognitive effects, also comes into play.

Thus the first and second yin-yang aspects of electrotherapy convey the integrated tensions in therapy design (Figure 1). For example, an additional safety consideration for implanted stimulation controllers is circuit power consumption, which imposes constraints related to heating and battery life. A balance must be drawn between complexity of the controller in terms of computational analysis (which may enhance the specificity of therapy) and the need for a low power device that produces minimal heat and minimizes the need for battery recharging or replacement.

Mechanical Damage

An often unrecognized agency of damage is the implantation of electrodes in brain. A recent retrospective study of deep brain stimulation (DBS) electrodes in over 500 patients by Benabid et al.65, reports overall implantation-induced complication rates of 14% for temporary confusion and 13% for bleeding. In addition to these overt complications, more subtle functional changes independent of stimulation are regularly observed and reported in clinical settings from Parkinson’s disease (PD) to epilepsy66.

Electrodes are routinely implanted for presurgical evaluation and deep brain stimulation, and there has been an increasing awareness and quantification in the clinical literature of measurable effects attributed to microlesions67,68,69,70,71.

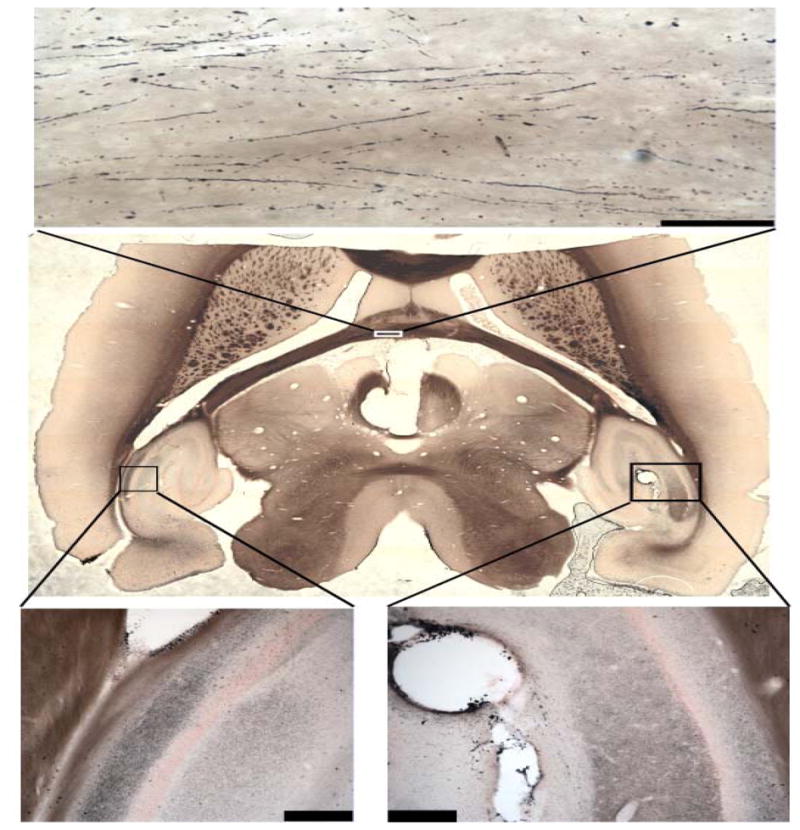

Recently, we set out to study stimulation safety limits with novel electrode materials. We implanted electrodes into the ventral hippocampus of rats, and, after a predetermined period of stimulation or no stimulation, sacrificed the animals and stained for neurodegeneration72. We found that even in unstimulated animals, any penetration led to extensive neurodegeneration both near and remote from the electrode tract and as far as the contralateral hippocampus (Figure 2). More specifically, the severed neurites degenerated wherever they projected. Given the dense micro-architecture of neurons and their projections, their sensitivity to the local environment, and the density and sensitivity of brain vasculature, it is ludicrous to presume that electrode implantation causes no collateral damage.

Figure 2.

Implant damage as measured by amino-cupric silver stain for neural degeneration in rat brain. Degenerating cells and cell processes appear black. Damage due to an electrode placed in right hippocampus (lower right) can be observed as far away as the left hippocampus (lower left), as well as fibers in the fimbria (upper). (Mason et al., unpublished results).

2.3.2 Concerning the empirical tuning of stimulation parameters

Third yin-yang of epilepsy electrotherapy

A conceptual balance is needed between cellular level research and clinical therapy; on the one hand to ensure that animal research is relevant to and mindful of clinical challenges and limitations, and on the other to ensure that treatment manipulation is based on biophysical mechanisms and rational design decisions rather than empiricism alone. Limitations, as much as accomplishments, in the one case, inform the overall approach taken in the other.

A growing number of clinical trials have used intracranial stimulation for epilepsy over the last thirty years. Most have employed continuous (e.g., Velasco et al.73) or cyclic (e.g., Andrade et al. 52) open-loop (preprogrammed) stimulation, including the multicenter SANTE trial (Stimulation of the Anterior Thalamic Nucleus for Epilepsy) in the United States; a few have attempted automated seizure detection and closed-loop/responsive stimulation74,75,8. Detailed reviews of these studies are available elsewhere76,77. Many of these trials employ one or more standard combinations of stimulation parameters, and assess changes in patient-reported or algorithm-detected seizure frequency with respect to a baseline value. The success of the trial is predicated on seizure rate reduction in a cohort of patients, or anecdotal visual evidence of termination of seizure activity upon stimulation. A favorable outcome implies that the set of stimulation parameter values used is somehow optimal for every patient: a magic combination that just works.

But average treatment success for a cohort does not guarantee success in the individual case. In truth, some parameter tuning is usually performed for each patient to increase safety, tolerability and efficacy. Stimulation parameter “optimization” is a trial-and-error endeavor, and assumes a relatively smooth dose-response curve. The prevailing procedure is to vary the duration, pulse width, amplitude and frequency of the waveform in an empirical manner during inpatient monitoring—or over repeated outpatient visits—so as to avoid patient discomfort, after-discharges or other side-effects, while observing safety limits for charge passage as specified by device manufacturers64.

While the goal of titrating parameters to improve therapeutic efficacy is reasonably clear, the parameter search procedures are hindered by various limitations; a few are discussed below:

Marker availability: The variable and intermittent nature of seizures makes the empirical titration of stimulation dose difficult, particularly when relying only on seizures—the primary marker—as the quantifying metric (seizure rate); more so when automated EEG analysis is not available (e.g., Andrade et al.52) since the physician must rely on patient reporting, which is inherently inaccurate. In a limited monitoring period, each set of parameters must be applied over a minimum number of events before any effect can be investigated with reasonable statistical power: i.e., the probability of detecting an effect in a finite random sample when there really is one78. It is considerably harder to correlate parametric changes with clinical response if the therapeutic benefit of electrotherapy takes weeks to months to materialize, which may be the case with vagus nerve stimulation. This is in contrast to diseases such as Parkinson’s where the primary marker, tremor or dyskinesia, is continuous and readily quantified, therefore providing immediate feedback on efficacy. But without knowledge of the biophysical mechanisms, there is no rational basis for assuming that waveforms optimized for other diseases/anatomical targets would be effective in epilepsy control.

Confounding factors: Drug taper38, physiological rhythms37, sleep stage34, stress, and various other factors are known to influence seizure rate and/or severity, and thereby interfere with the quantitative assessment of treatment effects.

Device constraints: Clinical studies are generally restricted to a limited stimulation parameter set and related technology. Given that this technology is developed with a limited understanding of the underlying biophysics, it is highly unlikely that the current set of devices/waveforms tested is optimal across cases. Setbacks in initial clinical trial outcomes should be reinterpreted in this context. Moreover, many medical devices offer a limited choice of testable waveforms; often, changing one parameter (e.g., frequency) automatically changes another (e.g., pulse width). While such constraints may be based on reasonable safety/efficacy factors, any resulting changes in clinical outcome cannot be attributed to a single parameter alone.

Dose-response nonlinearity: Clinical empirical optimization often follows unstated assumptions about the relationship between therapy outcome and waveform that may not be biophysically sound. The response of the brain to electrical stimulation is not monotonic or linear: for instance, doubling pulse width at one frequency may not produce quantitatively (or even qualitatively) the same outcome as at a different frequency. As another example, increasing stimulation amplitude at one frequency may aggravate seizures even as it ameliorates symptoms at another frequency. Stimulation duration, waveform, and intensity thus interact in a complex, nonlinear manner to produce distinct functional changes. And the dependence on waveform may differ fundamentally across metrics and patients. Since every waveform combination cannot be tested on each patient, any insight into the biophysical mechanisms of stimulation will greatly facilitate rational clinical screening protocols, even if therapeutic effects cannot be fully explained.

Stimulation artifact effects: Stimulation artifact may corrupt the EEG and, by extension, the metrics in use. Artifact reduction or objective blanking procedures must therefore be employed to compensate for tainted signals before further analysis, especially when comparing stimulated and unstimulated events75. Not being able to record and stimulate at the same time with pulsed stimulation can give ambiguous results: did the seizure terminate by itself or in response to stimulation? Anecdotal evidence is not in itself proof of efficacy, especially if stimulation is repeated at intervals until the seizure has stopped.

These points emphasize the pitfalls of empirical parameter optimization, as a consequence of which the flexibility and potential of electrical stimulation as a therapy are underutilized. However, because of patient variability in response and pathophysiology, and our limited understanding of biophysical mechanisms of stimulation, some empirical tuning is unavoidable. This limitation also applies to pharmacological and resection approaches; however, electrical stimulation, by virtue of allowing reprogramming across a wide range of open or closed loop parameters after deployment, offers special potential, and thus challenges, for patient-specific optimization. But purely empirical optimization across a wide parameter set is not practical for each individual patient and so must be based on a rational tuning strategy that balances the third yin-yang (the mechanisms/clinical gap), and the first two as well (Figure 1).

We recommend a two-stage approach for identifying safe and efficacious stimulation parameters in the individual case: First, a good initial guess must be formulated based on biophysical knowledge of stimulation mechanism for a particular combination of waveform, target, etiology, and seizure syndrome (see Section 3). Then, this estimate can be refined through statistical analysis using objective quantitative measures of marker response to stimulation such as seizure intensity, duration or spread.

The refinement stage could proceed using a statistical modeling framework, such as the one proposed by Osorio et al.24 for the objective retrospective analysis of data from acute clinical trials to identify a locally optimal stimulation parameter set. This model shows how the efficacy of stimulation parameters, varied in a step-wise manner to improve seizure blockage during a closed-loop stimulation trial, can be assessed. Apart from effects due to different trial parameter sets, the model corrects for potential effects of drug taper and circadian variation on seizure frequency and severity. When such models are developed and used, a realistic treatment goal must be specified and statistical power analysis78 performed both a priori and in retrospect to fix the minimum required sample size and monitoring duration for testing hypothetical treatment effects. The development of objective design and analysis methods that incorporate the features discussed above will greatly facilitate rational epilepsy electrotherapy.

2.3.3 Bridging the clinical-research gap

Treating the symptom or the cause?

We have remarked previously that seizures are a symptom of epilepsy (see 2.1); which means that they reflect some underlying disorder that produces or promotes seizures but is more than the seizure itself. As with other forms of therapy, there is the option with electrical stimulation of optimizing treatment protocols using either a symptomatic or a mechanistic approach. In the symptomatic approach, electrotherapy dosage is determined based on empiricism alone with prevention or interruption of individual seizures as the primary marker, and with the objective of reducing overall seizure frequency and/or severity.

The alternative mechanistic approach—i.e. to treat the underlying cause or mechanism—involves consideration of the cellular/molecular events or conditions known to promote seizures in a specific type of epilepsy and then developing a therapeutic strategy to attack this mechanism. We use the term mechanistic in a general sense to include molecular/kinetic mechanisms that promote seizure but are not necessarily the underlying cause of epilepsy. Mechanistic approaches require knowledge of the biophysics of electrical stimulation derived from experimental and/or computational models which, in turn, facilitate the design of rational clinical treatment strategies. In the mechanistic approach, overall efficacy is still evaluated by the primary objective of reducing seizure severity, though surrogate markers and metrics may be adopted to accelerate dose titration. In this section, we examine the consequences of these approaches.

The basic rationale for attempting electrical stimulation for epilepsy control is sound. Various mechanisms proposed in experimental research are cited in the clinical literature75,76 as justification for using electrical stimulation in clinical seizure control trials: the importance of targeted anatomical structures as gateways to generalization of seizure activity in the brain2; elevation of the seizure threshold79; regulation of glutamic acid decarboxylase and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gene expression80; and short or long-term synaptic depression81.

But these mechanisms are implicated in a very general sense: possibly because of its apparently diverse modes of action, the exact mechanism by which electrical stimulation may control seizure generation and propagation is unclear. And so, in purely symptomatic approaches, stimulation parameters are set empirically and seizure reduction is targeted as the primary endpoint of therapy. Parameters are empirically tweaked to avoid adverse effects and improve seizure control. In the absence of a rational therapy strategy, symptomatic approaches are generally restricted to a “familiar” set of stimuli, without true optimization and with little a priori consideration of individual epilepsy etiology.

The mechanistic approach involves identifying cellular/molecular/physiological mechanisms and related markers of epilepsy that can be targeted by electrical stimulation, formulating surrogate metrics of treatment efficacy if necessary based on these markers, and developing suitable therapeutic strategies through experimental/computational studies; though the ultimate goal remains a reduction in seizure frequency (primary metric). The mechanistic approach to treatment is gaining ground in pharmacotherapy82, in which one may target an aberrant ion current in an experimental disease model with a known channelopathy, and then evaluate the potential reduction in seizure frequency through clinical trials. Similarly, in mechanistic electrotherapy, a range of stimulation waveforms could first be explored in experimental and computational studies to customize therapy to individual epilepsy etiology.

Because of the potential for adapting stimulation waveform, electrical stimulation offers significant flexibility compared to pharmacological approaches. In pharmacological treatment, due to the slow transport kinetics and poor spatial specificity of action, drug development must focus on mechanistic factors and contend with undesired effects across the brain. With electrical stimulation these constraints are less significant. Greater control can be exerted over spatial specificity of the targeted structure and the effectively instantaneous current delivery to the brain allows temporal specificity and even implementation of adaptive feedback. Hence, stimulation dose can be rapidly titrated in a manner that potentially improves treatment efficacy. This potential for targeting seizure mechanisms with electrotherapy must be utilized better.

One barrier that remains is the reliance on a primary marker (i.e., seizures) for evaluating treatment, which sets the delay for information feedback to much longer than the typical interseizure interval. If instead, a more accessible surrogate treatment marker were available (e.g., IIS, HFO)—and the effect of stimulation and parametric variation on this marker established through a combination of experimental and computational analysis—stimulation parameters could be optimized during a clinical monitoring session over a much shorter period of time with an equal or greater potential for success. At present, surrogate markers that fill this need are yet to be identified, in part due to our limited understanding of seizure mechanisms. For instance, a better understanding of the preseizure cascade will facilitate mechanistic targeting of seizure generation, as well as the identification of physiological surrogate markers of seizure-permissive states (2.2.1) or suitable control signals for feedback control. Ongoing work is adding to the list of brain state measurements with quantitites such as impendance83, temperature84 and extracellular ion85 and neurotransmitter86,87 concentrations, any combination of which may lead to useful surrogates.

Limitations of experimental epilepsy models in translational electrotherapy

A majority of the mechanistic insights cited in this review were developed using brain slices where continuous epileptiform activity was induced by a convulsant or ionic imbalance. The word epileptiform is carefully used in much of the literature to convey that electrical activity is only similar in form to electrical activity observed during seizures; but without an intact brain and body with a cognitive behavioral correlate, these events are still different from seizures.

In research on isolated tissue preparations, insufficient consideration is given to brain activity distant from the particular ‘region of interest’, the clinical relevance of the epilepsy model in the context of electrical control, or the role of trauma and network isolation caused by slice preparation. Despite these inherent limitations, in vitro epilepsy models remain useful tools for rapid prescreening and mechanistic characterization of seizure control protocols.

In the context of electrical control of seizures, several special aspects confound the interpretation and translation of in vitro results (see 3.2). As an example, localized modulation of spontaneous epileptiform field activity in such studies is often cited as sufficient evidence for a clinically beneficial effect. In the case of low frequency and high frequency pulse trains, the effects of stimulation are often changes in activity patterns rather than complete suppression. For example, in Su et al.88, disorganized high amplitude electrographic seizures were replaced with population spikes in phase with stimulation. Though stimulation changes activity away from the spontaneous epileptiform pattern, this does not necessarily reflect a net decrease in average firing rate or synchrony, nor does it reflect an improvement in the network’s performance of its normal cognitive computations. Conversely, in other experimental studies, all neuronal firing was suppressed, for example by neuronal hyperpolarization, depolarization block, or membrane resistance decreases. There is no clear relationship between robust entrainment or suppression of neurophysiological activity and clinical benefits or side-effects.

Brain function is not a simple sliding scale of excitability, nor is the see-saw cartoon of epilepsy as an imbalance between excitation and inhibition likely to produce therapies that are specific only to epileptic activity. Thus the notion that any stimulation that “reduces excitability” in vitro is of potential clinical benefit remains to be validated. Moreover, acute brain slice studies by nature explore only the relatively short-term (few hours) effects of stimulation, while clinical studies are concerned with chronic benefits.

3. What can electrical stimulation accomplish?

A fundamental challenge in bridging the gap between basic research and clinical application lies in understanding how electrically induced neurophysiological changes at the synaptic, cellular and network levels can produce the desired clinical outcome. Only the former are available in brain slices and animal models.

In clinical trials, taking advantage of automated metrics of primary and surrogate markers requires an understanding of what physiological changes are beneficial, specific, and safe. It is not yet apparent what the (clinically) desirable acute effects of stimulation on tissue are: namely, what neurophysiological outcomes (metrics) of electrical stimulation (e.g. changing unit firing rate/coherence) can be monitored during stimulation to optimize electrical stimulation protocols, either intra-operatively or thereafter. Conversely, understanding which neurophysiological outcomes of electrical stimulation are clinically relevant, will guide animal and computational studies (2.3.3).

In this section, we review the general biophysical mechanisms of action of electrical stimulation starting from the cellular level (3.1), and articulate and classify epilepsy-related findings from the basic research arena (3.2).

3.1 Biophysical mechanisms of action

Electrical stimulation for epilepsy can be applied to the peripheral nervous system (PNS) or the central nervous system (CNS). In either application we must consider the system-level functional outcome of electrical modulation which reflects the aggregate effects on cellular processes such as action potential triggering. Bridging the gap between cellular and network responses and ultimate changes in symptoms/behavior is a necessary step toward rational electrotherapy.

PNS Cellular Targets

Direct electrical stimulation of the peripheral nervous system (PNS), using implanted or surface electrodes near peripheral axon fibers, is relatively easy to fathom: supra-threshold electrical pulses trigger action potentials in fibers. The pulses are typically < 1 ms in duration and applied in repetitive trains. The direct mechanism of action is that currents driven within individual cells converge at a point within the axon until they are sufficient to locally push its transmembrane potential over threshold. Typically, these action potentials are conducted bidirectionally along the axon toward both the periphery where, for instance, they may activate muscle fibers, and towards the CNS, where they are received as orthodromic or antidromic input.

Functionally there is a spectrum of stimuli and outcomes: (a) Intermittently applied pulses can supplement or increase the overall firing rate with, simplistically, each pulse triggering one action potential in selected axons; (b) More frequently applied pulses can overwrite the information content of the source cells, with—in the extreme case—axonal firing bearing a one-to-one relationship with the applied pulses; and (c) High frequency/intensity pulses can trigger secondary processes such as depletion of neurotransmitters, accumulation of extracellular potassium (e.g., in the axon hillock), and even functional lesioning of nerve fibers89.

In functional electrical stimulation applications, where orthodromic activation of muscles is the desired outcome—for example, in patients with spinal injuries—the behavioral effects are relatively straightforward. In cases where therapeutic effects such as epilepsy control are mediated by presumed action potential propagation from the periphery into the brain—for instance, vagus nerve stimulation—the process linking axon activation and behavioral change is substantially more complicated.

CNS Cellular Targets

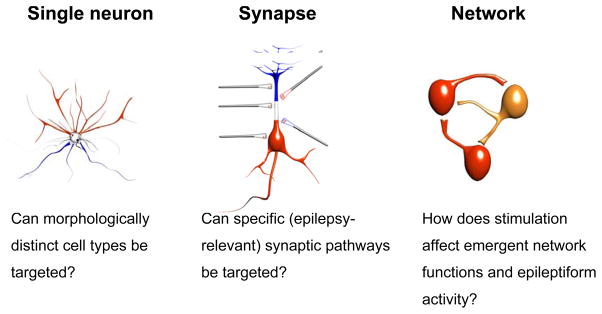

The effects of direct stimulation of the central nervous system (CNS), using surface or implanted electrodes near the brain or spinal cord, are still more complex. During CNS stimulation it is necessary to consider relevant properties of each anatomical target (see 3.2.1) as well as the morphological/biophysical diversity of neurons in each target. Indeed, a fundamental challenge is to understand which neuronal elements are activated by a specific electrical stimulation protocol (Figure 3). Potential targets include excitatory or inhibitory neurons, synaptic terminals, axons of passage, glia, etc. Depending on electrode geometry and orientation, waveform shape, frequency content, and application timing, a broad range of effects can be achieved that preferentially stimulate different targets and pathways. Knowledge of these relationships can be used to optimize custom electrical therapies.

Figure 3.

Some important questions relating to the potential specificity of action of electrical stimulation in the brain.

In CNS, the direct mechanism of action for short (< 1 ms) pulses may be similar to that in PNS, with each extracellular pulse triggering action potentials in targeted neurons; however the diversity of targeted cell types (notably excitatory and inhibitory neurons) and their complex interconnectivity (e.g., positive/negative feedback), will ultimately determine changes in firing rate and pattern. For longer duration (lower frequency) waveforms, the biophysics of electrical stimulation are better understood by considering the induced polarization along the entire neuronal membrane including soma and dendrites. For example, the main trunk dendrite and soma of pyramidal neurons will polarize during low-frequency sinusoidal stimulation yielding a shift in somatic transmembrane potential and therefore an effective shift in excitability90. The timescale for such polarizations in hippocampal pyramidal neurons is of the order of 20 ms91,92.

On longer timescales, other pathways may be activated. For example, the glia, through their gap junctions, form a large syncytium responsible for transporting metabolites and ions between the vascular system and the neurons. Quasi-DC electric fields applied on the timescale of seconds will polarize this structure and drive the potassium spatial buffering system93,94,95.

Supra- and sub-threshold stimulation

Supra-threshold or activating stimulation conventionally indicates electrical stimulation that directly triggers action potentials. Sub-threshold or neuromodulating stimulation conventionally indicates weaker stimulation intensities that are not sufficient to trigger action potentials in a quiescent neuron, but may nonetheless modulate ongoing action potential generation.

Repetitive supra-threshold stimulation, particularly of epileptic tissue, may also excite secondary cumulative changes such as extracellular ion concentration changes that then modulate brain function without triggering action potentials96. Conversely, application of nominally sub-threshold AC or DC fields to epileptic tissue, where neurons are near or regularly passing AP threshold, may directly modulate action potential generation or timing97. The activation threshold of a neuron to electrical stimulation is strongly modulated by the activity of afferent neurons98. As such, the interpretation of ‘sub-threshold’ and ‘supra-threshold’ stimulation depends as much on the state of the network as on the stimulation intensity.

Extracellular molecular/ionic dynamics and role of non-neuronal cells

Changes in the activity of extracellular ions and neuromodulators, on a scale that encompasses a small neuronal network, have been linked to the neuromodulatory effects of electrical stimulation99. For example, high-frequency stimulation of sufficient intensity leads to extracellular potassium transients, which in turn can affect a range of cellular processes96.

Glial cells are considered to play an important role in the regulation of the extracellular environment, including potassium93,94,95,100 and glutamate regulation101,102. Their role in seizure dynamics and generation has also been investigated103,104. The glial syncytium can be polarized with very low electrical fields to modulate potassium spatial buffering93,94,95.

Other non-neuronal cells that may be affected by electrical stimulation include endothelial cells that form the blood-brain barrier and tightly regulate the extracellular environment.

Acute and plastic changes

It is also convenient to distinguish the acute and plastic effects of electrical stimulation. Acute effects may be considered as those stimulation-induced changes in neuronal activity that are immediately or rapidly reversed after termination of stimulation. Plastic changes indicate changes in neuronal activity or state that outlast the termination of stimulation by hours or days (see also 3.2.2).

Networks and timing

It has been shown that network responses to electrical stimulation can be more sensitive than the detectable sensitivity of member neurons. For example, Francis et al.105 demonstrated detected sensitivity of hippocampal networks to electric fields with waveform packets of frequency content below 20 Hz at a level of 295 V/mm, while the average sensitivity of the single neurons in the network was 33 % higher. Likewise, Deans et al.92 demonstrated similar network sensitivity to DC packets. In these works, the statistical modulation of the activities of individual neurons was enhanced through coupling with other similarly modulated neurons; indeed the nature of macroscopic stimulation is such that a population of neurons receives coherent input. Additional enhancements were observed when the stimulation frequency was at natural oscillation frequencies of the network.

It is increasingly recognized that functional effects of electrical stimulation may be mediated by a change in firing time/waveform rather than an increase/decrease in average firing rate of specific neuronal elements; moreover, the effects may be completely state and pathway specific. It has long been established that neuronal firing rate (timing) is sensitive to applied fields106,107, and this has recently been addressed quantitatively97. Electric fields modulate synaptic information processing in a highly pathway (axon bundle) and state dependent manner91. The waveforms of normal and epileptiform neuronal and neuronal network activity manifest high sensitivity to electric fields108,92,105,109 that is likely both due to coherent effects of fields on many neurons as well as state-specific network amplification/adaptation mechanisms110. At the single cell, synapse, and network level, the effects of electric fields on neuronal function will vary across specific pathways and the functional state of the system. Thus, the design of clinical seizure control therapies based simply on vague and global generalities such as decreased cellular “excitability” may be fundamentally misguided.

Especially in the context of supra-threshold fields, we note that because most microscopic cellular processes are linked, one could argue that essentially any cellular process that is dynamic can be affected by stimulation. For example, repetitive action potential initiation with pulse stimuli will result in ion concentration changes that lead to a spectrum of signaling cascades. Thus, if one goes on a fishing expedition for electrical stimulation-induced cellular changes, one is guaranteed a good catch. Countless examples are available in the vast literature on Long Term Potentiation/Depression (LTP/LTD); and specifically for LTP induced by tetanic supra-threshold extracellular electrical stimulation. From the perspective of rational electrotherapy design, the important question is not simply which cellular level processes—firing rate, neurotransmitter function/plasticity, etc.—are changed. What is critical is how these cellular level changes result in meaningful therapeutic outcomes at the system and ultimately behavioral levels, and what functional and cognitive effects the interim stimuli induce.

3.2 Open-loop stimulation: anatomical targets and classification of waveforms

In this section we review findings from open-loop stimulation in an attempt to address the mechanistic question, by what biophysical pathways does electrical stimulation modulate brain function and nervous system dynamics at the cellular, synaptic, and network level; and where possible, the translational question of how these findings result in cognitive or behaviorally relevant effects. It is quite possible that a stimulation protocol that appears excitatory at the cellular level may turn out to be clinically beneficial if seizures are reduced with minimal side-effects. This highlights the difficulty involved in translating basic research findings into something of ultimate therapeutic value, and further reiterates the yin-yang tension between cellular mechanisms and clinical realities.

Integration of outcomes from animal and clinical studies

A majority of biophysical insights were derived from animal studies. But in general, animal models do not reproduce the same epileptic dynamics observed in humans, though they often reproduce specific clinically relevant patterns.

Cellular mechanisms are easiest and most commonly studied using in vitro brain slice experiments. But in vitro models, even when the tissue is derived from chronic epilepsy models, manifest limited electrographic similarity to human epilepsy with dynamics that may reflect only unrelenting synchronized activity similar to status epilepticus, interictal-like activity, or episodic epileptiform activity whose recurrence is highly accelerated compared to the clinical case. Additionally, electrical stimulation is generally applied in a manner that overwhelms the neural network activity and yields either robust pacing or complete suppression of firing. In vitro, it is difficult or impossible to define a cognitive function for the network. Therefore these findings are without regard to the functional, behavioral or cognitive outcomes of electrical stimulation (our first yin-yang); nor is there a method for testing these effects.

In chronic studies, the animals are typically significantly impaired and behaviorally altered. For example, in our hands, rats treated with a focal hippocampal injection of tetanus toxin to induce a limbic model of epilepsy are highly aggressive and nervous, and would make difficult subjects for use in subtle cognitive investigations. Indeed, Heinrichs and Bromfield111 have phenotyped abnormal behaviors for various animal models of epilepsy. For all the above reasons, in what follows, we are careful to distinguish clinical therapeutic success from successful control of seizures or seizure-like activity reported in animal studies.

Clinical studies remain the final measure of electrotherapy outcome and both the efficacy and safety merits of each electrotherapy strategy. Safety considerations severely restrict the range of electrotherapy dose testable in each subject, epilepsy etiology is evidently not controlled as is the case for animal studies, and biophysical mechanisms can only be probed clinically with relatively gross tools.

Waveform-centric classification

Durand and Bikson112 reviewed the basic mechanisms of seizure control by classifying stimulation waveforms into paradigms with presumed distinct neurophysiological outcomes: 1) Quasi-DC sub-threshold waveforms; 2) Low-frequency supra-threshold pulses; and 3) High-frequency supra-threshold pulse trains.

There are difficulties in waveform-centric classification: Each class itself includes a wide range of stimulation protocols and waveform subtypes. Moreover, this classification scheme groups studies where similar waveforms were applied to different brain targets (3.2.1) and attempts to draw wide generalities across seizure etiology and semiology. It is also necessary to independently consider the acute and long-term (plastic) outcomes of each stimulation waveform (3.2.2). The use of feedback control may fundamentally change the efficacy or safety profile of each waveform subtype and is dealt with separately (3.3).

Ultimately, patient- or technology-specific factors and rational design decisions balancing efficacy and safety (our first and second yin–yang aspects) should determine optimal individualized treatment. For example, epilepsy of hippocampal origin may require an implanted electrode where electrochemical factors64 restrict waveform selection but stimulation can be applied chronically. In contrast, a noninvasive system may be used to induce antiepileptic changes in superficial cortex where electrochemical factors are not paramount but only intermittent treatment (e.g. during hospital visits) is feasible and thus plastic changes are essential.

There remains, however, a rational basis for independently considering waveform-centric classes based on biophysical distinctions in mechanism of action. Therefore, we present in sections 3.2.3–5, a discussion of findings of advantages and limitations of each open-loop waveform class. But first, we discuss the roles of anatomical targets (3.2.1), and the difference between acute (ON) and persistent (OFF) changes in relation to the choice of stimulus cycle (3.2.2).

3.2.1 Anatomical targets

Clinical studies are often grouped by anatomical target76,77, but target-specific factors need to play a greater role in individualizing electrotherapy strategy and characterizing its mechanisms. In this section, we summarize what is known about the diversity in anatomical target response to electrical stimulation, and outline target-specific features that may distinguish response even to identical waveforms, and should be considered in rational electrotherapy. These features will vary across individuals (e.g. anatomy) and may be affected by patient-specific epilepsy etiology.

Anatomical geometry and neuronal morphology

The macro and micro anatomy significantly influence the spatial and temporal distribution of the effects of electric fields during stimulation. Neuronal morphology also determines which neuronal compartments are polarized, in what direction, and to what degree under an applied electric field90,113. This factors into the maximal depolarization under sub-threshold fields, and in which compartments action potentials are generated during supra-threshold stimulation.

Afferent/Efferent connections

The input-output connections among different regions114,115 can influence the dynamics of neuronal populations and sensitivity to electrical stimulation. As is true of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s and functional electrical stimulation (FES), if axonal projections (axons of passage) are excited in the vicinity of the electrode, the functional target of stimulation is determined by where those axons project, and not solely by the neuronal network near the stimulation electrode(s). On the other hand, interconnections can induce a broader effect on the neuronal tissue, through the “diffusion” of excitation/inhibition to the connected regions or the generation of feedback loops. One approach to analyzing the functional outcome of stimulation is to focus on induced changes in efferent activity in the context of global network function.

Neuron-specific biophysics

Biophysical properties, for instance the types and numbers of membrane channels, influence the response of a neuron to electrical stimulation. For example, usually the neuronal membrane acts electrically like a low-pass filter (in the subthreshold voltage range) but some types of channels (e.g., a combination of persistent sodium and muscarinic potassium channels) can induce resonant behaviors of the neuronal membrane (i.e., more frequency-specific116,117). Individual neurons, even within the same target region, with different morphologies and biophysical properties, may thus have different responses to stimulation.

3.2.2 Open-loop acute ON/OFF control and plastic changes

In electrotherapy of movement disorders, continuous stimulation during therapy is standard118,119; it is thus noteworthy that in epilepsy therapy intermittent (ON-OFF) protocols are being explored120,53.

It is useful to subdivide the effects of open-loop stimulation into acute ON effects, acute OFF effects, and plastic changes. The distinction between ON and OFF effects is made when the stimulation is intermittent (e.g., repeated patterns of 5 min on, 5 min off): the ON effects occur during a functional stimulation “unit” such as a pulse train, and the OFF effects are observed transiently after each ON functional unit ends. Though OFF effects may accumulate across multiple OFF periods, they may be considered spontaneously reversible over the timescale of minutes if the stimulation is completely aborted. Examples may include extracellular and intracellular ion, metabolite, or neurotransmitter accumulation.

Plastic changes are then relatively long-lasting changes that persist after the termination of stimulation, and follow significantly slower biophysical dynamics (e.g., hours, days) than OFF effects. Examples of plastic changes may include modulation of synaptic efficacy and connectivity, neuronal morphology/biophysics, or genetic/expression molecular changes.

The acute ON effects of stimulation may be fundamentally different from acute OFF effects and plastic changes. Chronic continuous stimulation is concerned mainly with ON effects, though these may be accompanied by plastic changes, while intermittent stimulation must also consider the possibility of hazardous or beneficial acute OFF effects (ON-OFF seizure control88). Any treatment based on sporadic stimulation, for example, weekly electrical stimulation sessions, relies on plastic changes since stimulation is off most of the time. The ON effects, OFF effects, and plastic changes in brain function brought about by stimulation may be functionally distinct and potentially even antagonistic in the context of epilepsy control, safety, or side-effects. Because of differences in how waveforms are applied and outcomes are measured, it is important to elucidate these distinctions.

3.2.3 DC waveform electric fields

DC electric fields may directly hyperpolarize the cell soma or region involved in action potential initiation, thus decreasing excitability for the duration of stimulation. In brain slice epilepsy models the evidence for acute suppression of epileptiform activity during DC stimulation is incontrovertible, as there are minimal stimulation artifact confounds, and spontaneous field activity is evidently blocked108,121. Though DC fields can transiently control epileptiform activity in acute animal models, several practical issues confound the translation of this technique to clinical practice. Abrupt termination of long duration DC stimulation has been observed to lead to an anodic break-like immediate rebound of epileptic activity in vitro (OFF effects), while reversal of DC polarity may aggravate seizures108. Additionally, because monophasic charge passage during stimulation is limited at electrode-tissue interfaces before tissue or electrodes are electrochemically damaged64, true DC stimulation is not possible. For implanted electrodes, net charge passage must be averaged to zero over time. How this is accomplished must take into account the other confounding factors indicated. One solution has been the adaptive stimulation discussed below122.

Though DC fields can prevent seizure initiation or reduce seizure incidence122, they may only be able to modulate and not abort ongoing electrographic seizures after they have started15. Strong DC fields may generate seizures in normal tissue91 but only at intensities well above those needed to acutely suppress seizures121. In hyperexcitable tissue, brain slice studies have indicated that whether DC fields suppress or aggravate seizures depends on neuronal geometry relative to the sign and direction of the applied fields.

Richardson et al.123 demonstrated that a cylindrical electrode placed axially in the hippocampus, similar to the placement of a standard clinical hippocampal depth electrode, creates a radially expanding field that is aligned with the CA3 pyramidal cell neurons and can be used to polarize them and thereby modulate their activity. Though this study was performed acutely in animals, the finding has a direct clinical translation path.

To our knowledge, DC or very-low frequency stimulation through CNS-implanted electrodes has not been applied to humans, in part due to electrochemical safety concerns, though related “slow-adaptive” approaches are being developed (3.3).

DC stimulation through noninvasive electrodes is not associated with significant electrochemical concerns beyond mild skin irritation (as electrochemical products at scalp electrodes are not expected to diffuse to the brain). Noninvasive experimental studies in normal human subjects have shown that transcranial DC stimulation (tDCS) can induce lasting changes in brain function124,125 when applied for several minutes. Changes in excitability are polarity-dependent, with surface cathodal stimulation decreasing excitability and surface anodal stimulation increasing excitability, as indicated by TMS evoked motor responses126. Because it is generally impractical for patients to constantly wear a noninvasive stimulation device, noninvasive therapies are applied sporadically on an outpatient basis—for instance, brief daily sessions repeated over several days—in the hope of inducing plastic (long lasting) changes in brain function. Interestingly, in exploring transcranial DC control of seizures in an animal epilepsy model, cathodal stimulation was anticonvulsant while anodal stimulation did not aggravate seizures124.

3.2.4 Repetitive low-frequency waveform stimulation (typically < 3 Hz)

An ideal form of electrical seizure control might be a single precisely tuned pulse that resets or annihilates a developing or ongoing seizure. This approach has been explored in vitro through desynchronization of network activity, for example, by Durand and Warman127, and recently in vivo by Osorio and Frei46.

Control of epileptiform activity with low-frequency supra-threshold pulse trains has been demonstrated in brain slices. It has also been proposed that certain types of interictal activity may interfere with generation of ictal seizures128,129. Entrainment of interictal-like bursts with ~1Hz pulse trains in hippocampal slices was shown to interrupt the development of full electrographic seizures130. The network mechanism linking short bursts and seizure suppression was investigated in reentrant networks including both the trisynaptic hippocampal and entorhinal networks131, and further elucidated by D’Arcangelo et al.132.

Schiller and Bankirer133 demonstrated that in neocortical slices, the underlying mechanism for seizure suppression from low-frequency (0.1–5 Hz) sustained pulse trains was short-term synaptic depression of excitatory neurotransmission.

In chronic animal studies, low-frequency stimulation was demonstrated to foreshorten electrographic seizure duration in an acute seizure model134.