Abstract

Recent case law and social science both have claimed that the developmental limitations of adolescents affect their capacity for control and decision making with respect to crime, diminishing their culpability and reducing their exposure to punishment. Social science has focused on two concurrent adolescent developmental influences: the internalization of legal rules and norms that regulate social and antisocial behaviors, and the development of rationality to frame behavioral choices and decisions. The interaction of these two developmental processes, and the identification of one domain of socialization and development as the primary source of motivation or restraint in adolescence, is the focus of this article. Accordingly, we combine rational choice and legal socialization frameworks into an integrated, developmental model of criminality. We test this framework in a large sample of adolescent felony offenders who have been interviewed at six-month intervals for two years. Using hierarchical and growth curve models, we show that both legal socialization and rational choice factors influence patterns of criminal offending over time. When punishment risks and costs are salient, crime rates are lower over time. We show that procedural justice is a significant antecedent of legal socialization, but not of rational choice. We also show that both mental health and developmental maturity moderate the effects of perceived crime risks and costs on criminal offending.

I. Introduction

Adolescence is a sustained period of psychological, social, and biological development and change, and also a transitional period when risks of crime and other antisocial behaviors are greatest. Recent case law (Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005)) has noted that the developmental limitations of adolescents affect their capacity for control and decision making with respect to crime, diminishing their culpability and reducing their exposure to punishment. These developments in case law have relied both on psychological research and neuroscience (cf. Steinberg & Scott 2003). The intersection of these two disciplines suggests that adolescents think and behave differently from adults, and that the deficits of teenagers in judgment and reasoning are the result of psychosocial immaturity, possibly owing to a far longer process of organic development of essential neuropsychological capacities.

Each research stream concludes that adolescent development is probably most fluid for teenagers at 16 and 17 years of age, and that the psychological functions of social judgment, autonomy, control, and rationality stabilize during early adulthood. Developmental change also leads to variable responses—both within and between individuals—to legal sanctions and other social influences, as well as uneven capacities for internal regulation and control that are requisites for avoiding crime.

Recognizing the influence of development and change during adolescence, criminologists have focused recently on two concurrent developmental influences on the relationship between legal sanctions and criminal activity. One developmental process results in the internalization of legal rules and norms that regulate social and antisocial behaviors, and that create a set of obligations and social commitments that restrain motivations for law violation. This process of legal socialization has been studied intermittently over the past quarter-century (see, e.g., Easton 1965; Tapp & Levine 1977; Cohn & White 1990; Fagan & Tyler 2005), and rarely with population groups most heavily involved in violence or other criminal law violations. The effect of legal sanctions for law violations on the development of these norms among adolescents has never been studied.

A concurrent developmental process is based on the emergence of rationality to frame behavioral choices and decisions. This construction of deterrence is closely attuned to experiences with both the social and personal costs and payoffs of offending, as well as punishment costs associated with legal sanctions. The interaction of these two developmental processes, and the identification of one domain of socialization and development as the primary source of motivation or restraint in adolescence, is the focus of this article.

According to the deterrence doctrine, the imposition of punishment costs, to the extent that they are swift, certain, and severe, should inhibit criminal activity (Beccaria [1764] 1963; Gibbs 1975; Tittle 1980; Zimring & Hawkins 1973). The second source of influence comes from developmental theories that are broadly concerned with the development, over time and within persons, of personal capital. Developmental theories suggest that a process of legal socialization, that is, the process through which individuals acquire attitudes and beliefs about the law, influences the relationships of adolescents to the law, and influences the effects of legal sanctions on future criminal activity. These two theoretical domains, deterrence and legal socialization, interact to influence both the effects of sanctions and decisions to persist in or desist from criminal activity.

Although there has been much research on the role of deterrence and sanctions on future criminal activity (Nagin 1998; Smith & Gartin 1989) and somewhat less research on legal socialization (Tyler 1990), this line of inquiry has concentrated more on adult, general population samples. Unfortunately, there exists no application of these sources of influence on the future criminal activity of serious adolescent offenders (cf. Piquero et al. 2005). This is an unfortunate happenstance since knowledge about the offending patterns in terms of persistence/desistance—and their correlates—of adolescent offenders is a significant policy concern (Laub & Sampson 2001). In this article, we use data from the Research on the Pathways to Desistance (RPD) Project, a prospective study of 1,355 serious adolescent offenders from Philadelphia and Phoenix, to examine how deterrence and legal socialization relate to criminal activity over a four-year period. Before we present data on this issue, we provide a brief overview of the literatures that we combine and integrate into a model of offender decision making, legal socialization, and deterrence.

A. Legal Socialization

Legal socialization is the internalization of law, rules, and agreements among members of society, and the legitimacy of authority to deal fairly with citizens who violate society's rules. What adolescents see and experience through interactions with police, courts, and other legal actors shapes their perceptions of the relation between individuals and society. The effects of legal sanctions and punishments contribute to trajectories of legal socialization. For example, punishment can reinforce or weaken the development and internalization of legal and social norms. When sanctions are delivered fairly and proportionately, they reinforce the legitimacy of the law and can contribute to compliance and desistance. However, when punishment is delivered unfairly and/or disproportionally, it leads to cynicism about the law and can contribute to anger and persistence (e.g., Sherman 1993; Piquero et al. 2004).

Psychologists studying the development of moral values and orientations toward the legal system have emphasized the crucial role of the childhood socialization process on subsequent adolescent and adult behavior. For this reason, a great deal of attention has been focused by psychologists and other social scientists on the importance of developing and maintaining moral values in children (Hoffman 2000; Mussen & Eisenberg-Berg 1977), as well as on the childhood antecedents of a positive orientation toward political, legal, and social authorities (Easton 1965; Krislov et al. 1966; Melton 1985; Tapp & Levine 1977). This earlier focus on developing a positive social orientation has led to a number of studies of childhood socialization.

The findings of these studies provide evidence suggesting that the roots of social values lie in childhood experiences (Cohn & White 1990; Easton & Dennis 1969; Greenstein 1965; Hyman 1959; Merelman 1986; Niemi 1973; Hess & Torney 1967). In particular, early orientations toward law and government were found to be affective in nature, and characterized by idealization and overly benevolent views about authority. These early views shaped the later views of adolescents, views that were both more cognitive and less idealized in form (Niemi 1973). As a consequence, each stage of the socialization process is found to influence later, more complex, views.

The core argument underlying the legal socialization literature is that children develop an orientation toward law and legal authorities early in life, and that that orientation shapes both adolescent and adult law-related behavior. Similarly, the psychological literature on the development of moral values suggests that values develop early in life, and similarly shape adolescent and adult behavior (Blasi 1980). The studies within this literature support this argument by showing that both social orientations toward authority and moral values play a role in shaping the law-related behavior of adolescents and adults (Tyler 1990).

B. Procedural Justice

An important factor influencing the development of adults’ views about legitimacy are their judgments about the fairness of the manner in which the police and the courts exercise their authority. Such procedural justice judgments are found to both shape reactions to personal experiences with legal authorities (Paternoster et al. 1997; Tyler 1990; Tyler & Huo 2002; Piquero et al. 2004) and to be important in assessments based on the general activities of the police (Sunshine & Tyler 2003; Tyler 1990). In both cases, adults view the police and courts as less legitimate when they personally experience or vicariously become aware of instances of procedural injustice. These same studies further indicate that adults usually define the fairness of procedures by considering four factors: the degree to which they have voice and can express their opinions and concerns; the neutrality and factuality of the decision-making procedures used; the politeness and respectfulness of their interpersonal treatment; and the degree to which they believe that the authorities are acting with benevolent and caring motives.

Accordingly, experiences with the law and legal actors will shape and modify trajectories of legal socialization. These subjective evaluations of fair and respectful treatment are not simply cold cognitions or judgments; rather, these experiences carry with them an affective or emotional component that animates views about the legitimacy of the law, cynicism toward it, or a disengagement from the law's moral underpinnings. Although fair treatment may enhance evaluations of the law, poor treatment may arouse negative reactions or even anger, leading to defiance of the law's norms (Sherman 1993; Paternoster et al. 1997; Piquero et al. 2004). This would suggest that procedural justice exerts both direct effects on compliance with the law as well as indirect effects by shaping evaluations of the law's legitimacy.

C. Rational Choice

In criminology, the deterrence/rational choice framework offers that behavior is determined, in part, by a weighing of the costs and benefits associated with criminal offending (Clarke & Cornish 1985; Piliavin et al. 1986; Nagin 1998; McCarthy 2002). Classic depictions of the deterrence doctrine anticipates that swift, certain, and severe sanctions from formal systems of social control create costs that will deter future criminal activity (Gibbs 1975; Tittle 1980; Zimring & Hawkins 1973). Additionally, formal sources of social control may spur concurrent informal sanctions from peers, families, and other social relationships, sanctions that may ultimately lead to deterrence (Williams & Hawkins 1986). These costs subsume several domains, including social, legal, and personal costs of offending. Costs compete with the returns from offending. Individuals may value and seek social (status, material) and personal (affective, emotional, visceral) rewards from involvement in criminal activity (Katz 1988; Nagin & Paternoster 1993). For example, some enjoy the thrill or rush that arises from crime or the defiance of social or legal norms, and take pleasure in the social status, recognition, and deference from others that criminal involvement can produce.

Much of the research dealing with deterrence/rational choice has been conducted with population samples, primarily high school (Paternoster 1987) and college students (Nagin & Paternoster 1993; Piquero & Tibbetts 1996; Pogarsky 2002) and community samples of adults (Grasmick & Bursik 1990). These studies tend to indicate that the certainty of sanction is a small, but significant, deterrent to more minor forms of criminal activity (Nagin 1998). Additionally, in most studies, individuals are sensitive to the rewards of criminal activity such that the perceived thrill/benefit associated with offending serves to increase the likelihood of crime above and beyond sanction threats (Nagin & Paternoster 1993; Piquero & Tibbetts 1996).

At the same time, several investigations have been conducted among high-risk juvenile (Matsueda et al. 2006) and adult offender samples, including incarcerated and active offenders (Apospori et al. 1992; Decker et al. 1995; Piquero & Rengert 1999; Tunnell 1992; Wright & Decker 1994, 1997). Although some may suggest that the use of an offender-based sample can offer little to a complete understanding of criminal activity (i.e., by offending, these individuals have already shown that they are insensitive to sanction threats), evidence does suggest that sanction threats are still important considerations among offenders. For example, even among active offenders, interviewed in the community, deterrent considerations—especially in the certainty domain—operate as important determinants of criminal activity. Offenders are sensitive to the likelihood of detection such that they are likely to select different (i.e., “easier”) targets based on the probability of detection as well as the probability of reward (see Decker et al. 1995; Piquero & Rengert 1999).

However, there also are several reasons active offenders, whether adolescents or adults, may evidence lower sensitivity to sanction threats. First, their immaturity alone may attenuate their perceptions of risk and their evaluations of the consequences of criminal behavior. Second, they may discount, or deliberately devalue, sanction threats that tend to be more future than present oriented. For example, Nagin and Pogarsky have linked discounting to various deterrence concepts (Nagin & Pogarsky 2001, 2003) as well as future-related problem behavior (Nagin & Pogarsky 2004), while Pogarsky and Piquero (2003) found that the presence of the gambler's bias1 corresponded with lower sanction certainty estimates. Third, the spatial concentration of serious youth crime in disadvantaged neighborhoods may lower the perceived costs of punishment while inflating its social rewards of status and material gains (Fagan & Wilkinson 1998a, 1998b; Anderson 1999). High-crime neighborhoods often have high unemployment rates, lower human capital, and lower wages, economic barriers that may influence how young offenders evaluate the returns from conforming behavior (Fagan & Freeman 1999). Accordingly, if punishment is discounted by perceptions that compliance may not “pay,” then incentives to avoid crime are compromised. Fourth, the contingent effect of sanction threats may be reduced by the high rates of punishment in these neighborhoods. Stigma costs are reduced, as is its contingent probability, when would-be teenage offenders perceive sanctions as inevitable, widespread, and not stochastically tied to criminal activity (Nagin 1998; Fagan & Freeman 1999).

Beyond rational discounting, the assumptions of rationality in most deterrence frameworks also are contradicted by the co-morbidity of mental health and drug dependence among active offenders (Kessler et al. 1994; Loeber et al. 1998; Huizinga & Jakob-Chien 1999). Both conditions can potentially impair or skew rational calculations of risk and reward and generate motivations that may skirt the calculus of offending based on a narrower risk-reward model of decision making. For example, Goldstein (1985, 1989) identifies motivations for aggression tied to both the psychoactive effects of drugs and involvement in drug violence (Fagan 1994), while Link et al. (1998, 1999) show that irrationally perceived threats among the mentally ill can override their internal controls to produce aggression. Even when these impairments are absent, strong emotional arousal (via fear or anger) often trumps control and reasoning in violent interactions between teenagers and young adults in high-crime settings (Fagan & Wilkinson 1998a; Wilkinson & Fagan 2000). Recently, Maroney (2006) has suggested that cognitive and emotional influences also affect rational decision making. Specifically, she argues that severe psychiatric mood disorder and organic brain damage interfere with decision-relevant criteria (perception, processing, and expression), and that a movement away from “rationality” toward a perspective that focuses on cognitive and emotional influences on decision making offers a more useful view of decision making.

D. Theoretical Integration

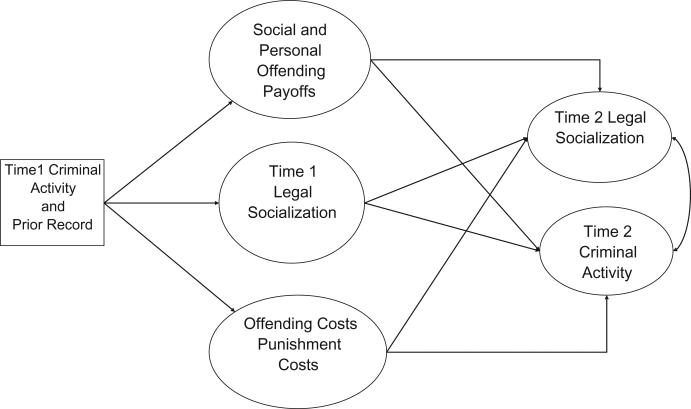

In this article, we combine the rational choice and legal socialization frameworks into an integrated, developmental model of criminal activity. This integrated model may be found in Figure 1. The model assumes that individuals bring with them a stock of personal and vicarious experiences with regard to deterrence and legal socialization. Over time, these concepts operate to influence further criminal activity. We suspect that sanction threats and punishment costs will curtail crime, while rewards and benefits will increase crime. Additionally, we suspect that legal cynicism will increase crime, while legitimacy will reduce crime. Finally, we expect that “good” experiences with the criminal justice system, specifically the police and the judge, will lead to reduced criminal activity.

Figure 1.

Rational choice and developmental influences on recidivism.

We also predict that many of these concepts will interact with time to influence criminal activity in important ways. For example, with each offending episode—and its eventual outcomes, such as punishment or punishment avoidance—offenders acquire information that may be used to update both their sanction risk estimate as well as more general orientations and perceptions about the law, legal system, and its social control actors. This Bayesian learning model of perceived risk formation has only recently been assessed and supported in the more general criminological literature on offender decision making (e.g., Lochner 2005; Matsueda et al. 2006; Pogarsky et al. 2004), but with nonoffending populations. Finally, because of the nature of our sample, and the documented mental health problems among correctional populations, we conduct additional, exploratory analyses where we examine the extent to which mental health impairments compromise both the influence of rational choice and legal socialization on recidivism.

II. Research Methods

A. Participants

Participants in this study were 1,355 adolescents (1,171 males and 184 females) enrolled in the Pathways to Desistance study, a prospective study of serious juvenile offenders in Phoenix (N = 654) and Philadelphia (N = 701) (Mulvey et al. 2004). Study methods and procedures are described by Schubert et al. (2004). Participants were adolescents 14–18 years of age at the time of the initial interview.2

Most participants were recruited from the juvenile court (82.1 percent) after being adjudicated delinquent for a serious felony offense; the remainder were transferred to criminal court and convicted of any of the same offenses. Subjects were sentenced for a range of offenses: 41 percent for violent crimes against persons (e.g., murder, rape, robbery, assault), 26 percent for property crimes (e.g., arson, burglary, receiving stolen property), 10 percent for weapons, 4 percent for sex crimes, and 4 percent for other crimes (e.g., conspiracy, intimidation of a witness). About half (50.1 percent) were incarcerated in a prison or jail at the time of the initial interview. Participants had appeared in court 2.69 times (SD = 1.12) in the past year on a total of 4.19 charges (SD = 2.92), including 0.43 drug charges (SD = 0.99).

Cases were randomly sampled in the juvenile court, with three exceptions. First, because drug law violations represent an especially large and perhaps disproportionate proportion of the offenses committed by this age group (Stahl 2003), the proportion of juvenile males with drug offenses was capped at 15 percent of the sample at each site. Second, to ensure adequate participation by females for statistical power, all females meeting the age and charge requirements were enrolled in the study. Similarly, all youths whose cases were being considered for trial in the adult system were eligible for enrollment. The sample includes approximately one in three adolescents adjudicated on the enumerated charges in these two locales during the recruitment period. The final sample included more than one in three (36 percent) eligible youths during the enrollment period. The participation rate was 67 percent (Schubert et al. 2004).3

Social and legal characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Participants were predominantly male (86.4 percent), African American (41.5 percent) or Hispanic (33.5 percent), and between 14 and 17 years of age at recruitment. Most participants came from families that were socially and economically disadvantaged, with low human capital and limited family resources. Fewer than 6.3 percent had parents with a four-year college degree, and 33 percent had parents with less than a high school education. Employment rates were low: while nearly two in three (63.7 percent) of the respondents’ mothers were working, fewer than half (48.2 percent) had fathers working outside the home. Nearly four in ten come from single-parent households headed either by mothers (33.6 percent) or fathers (4.6 percent). Single-mother households were headed by a biological mother who had either never been married (18.4 percent), or was divorced, separated, or widowed (15.4 percent); 13.6 percent of the participants lived with both their biological mother and father; 19.6 percent lived with a biological parent and stepparent; the remainder of the participants had other living arrangements (e.g., lived with other adult relatives), including 4.7 percent who lived with no adults in the home.

Table 1.

Respondent Demographic Characteristics and Legal Histories

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Site | ||

| Philadelphia | 701 | 51.7 |

| Phoenix | 654 | 48.3 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1,171 | 86.4 |

| Female | 184 | 13.6 |

| Race | ||

| White | 274 | 20.2 |

| Black | 562 | 41.5 |

| Hispanic | 454 | 33.5 |

| Other | 65 | 4.8 |

| Age at Intake | ||

| ≤14 | 162 | 12.0 |

| 15 | 255 | 18.8 |

| 16 | 412 | 30.4 |

| 17 | 413 | 30.5 |

| ≥18 | 112 | 8.3 |

| Family Structure | ||

| Both parents | 184 | 13.6 |

| Single mother | 458 | 33.8 |

| Mother/stepfather | 224 | 16.5 |

| Single father | 63 | 4.6 |

| Father/stepmother | 42 | 3.1 |

| Other adult relatives | 267 | 19.7 |

| Other | 117 | 8.7 |

| Mother's Education | ||

| <HS graduate | 433 | 33.0 |

| HS graduate | 357 | 27.2 |

| Other | 565 | 41.7 |

| Court Record | Mean | SD |

| Prior court appearances—past year | 2.69 | 1.12 |

| Prior court appearances—ever | 3.13 | 2.45 |

| Total charges on current petition | 4.19 | 2.92 |

| Total drug charges on current petition | 0.43 | 0.99 |

B. Procedures

Eligible youths were identified from a daily review of court record information at each site. Adolescents and their parents (or a participant advocate in situations where parental or guardian contact was unobtainable) provided informed consent to participate in the study, with 20 percent of those approached (either the adolescent or the parent) declining to participate. Participants and their parents were informed about the federal confidentiality shields that prohibited our disclosure of any personally identifiable information to anyone outside the research staff. Participants were also told that we were legally obligated to report any cases of suspected child abuse, or instances where an individual was believed to be in imminent danger either from a stranger or himself or herself.

Baseline interviews were conducted 36.9 days (SD = 20.6) after their adjudication in juvenile court or, for those in the adult courts, their arraignment hearing upon transfer from juvenile court. In most cases, the baseline interview took place immediately after the sentencing or disposition hearing (62 percent); in the majority of the remaining cases, the disposition hearing occurred before the six-month follow-up interview. Subsequent interviews were conducted at six-month intervals over two years.

Interviews were completed at the participants’ homes, institutional placement, or in a secure but private location such as a library. Interview conditions emphasized privacy, often taking place in settings that were out of hearing range of others. Trained interviewers read each item aloud and respondents generally answered aloud. However, in situations or in sections of the interview where privacy was a concern, a portable keypad was provided as an option to obtain a nonverbal response. Interviews after the baseline took about two hours to complete. Participants were paid $75 for their participation. The initial interview was completed in two two-hour sessions, and subsequent interviews each took two hours.

Retention across waves has been very high: about 92 percent of the scheduled interviews at each time point were completed on time. As a result, after 24 months, 77 percent of the participants did not miss any interviews (they have a baseline and four time-point interviews) and 89 percent have three or four of the time-point interviews. Overall, 2.5 percent of participants dropped out of the study and 2 percent died during the follow-up period.

C. Measures

Measures were developed in several domains: self-reported and official offending, costs and rewards of offending, legal socialization, procedural justice. In addition, we included measures of psychosocial maturity, substance abuse, and mental health to control for individual differences among participants. Measures were collected at each wave. Scale means and standard deviations are reported in Table 2, and their psychometric properties are shown in Table 3. Correlation matrices for all variables are shown in Appendices A and B. Scale properties were computed from confirmatory factor analyses and reliability analyses that generated Chronbach's alpha coefficients. Results show that measures for both the theoretical variables and the covariates are reliable and strong.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Theoretical Variables at Baseline

| Variable | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legal cynicism | 2.1 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 4.0 |

| Legitimacy | 2.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 4.7 |

| Social rewards | 5.8 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 11.6 |

| Punishment costs | 7.8 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 18.0 |

| Material costs | 5.9 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 13.0 |

| Freedom costs | 3.5 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| Personal rewards | 2.3 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| Punishment certainty—you | 5.2 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| Punishment certainty—others | 5.4 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| Social costs of punishment | 3.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| Procedural justice | ||||

| Interactions with police | 2.8 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 4.6 |

| Interactions with judge | 3.1 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 4.9 |

| Global severity index | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 3.2 |

| Psychosocial maturity index | 3.1 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 4.0 |

| Drug dependence | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0 | 10 |

Table 3.

Scale Properties at Baseline

| Scale | Alpha | Chi-Squared | CFI§ | RMSEAδ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanction likelihood—others | 0.822 | 143.2 | 0.954 | 0.069 |

| Sanction likelihood—you | 0.893 | 95.7 | 0.985 | 0.069 |

| Social costs of offending | 0.679 | 442.0 | 0.950 | 0.069 |

| Personal rewards of offending (thrills) | 0.874 | 349.9 | 0.944 | 0.093 |

| Social rewards of offending* | 0.75–0.82 | na | 0.94–0.98 | 0.07–0.08 |

| Punishment costs—freedom† | na | na | na | na |

| Punishment costs—material† | na | na | na | na |

| Procedural justice—police/you | 0.740 | 30.8 | 0.925 | 0.059 |

| Procedural justice—police/others | 0.570 | 22.6 | 0.966 | 0.056 |

| Procedural justice—judge/you | 0.748 | 279.5 | 0.925 | 0.059 |

| Procedural justice—judge/others | 0.652 | 90.6 | 0.939 | 0.078 |

| Legitimacy | 0.786 | 297.7 | 0.921 | 0.070 |

| Legal cynicism | 0.572 | 14.3 | 0.990 | 0.028 |

| Self-reported offending: total | 0.884 | 62.6 | 0.969 | 0.053 |

| Self-reported offending: aggressive | 0.774 | 108.0 | 0.956 | 0.041 |

| Self-reported offending: income | 0.798 | 122.2 | 0.954 | 0.056 |

| Brief symptom inventory—GSI | 0.953 | 8945.5 | 0.733 | 0.065 |

| Psychosocial maturity index | 0.890 | 1415.1 | 0.866 | 0.044 |

| Substance dependence† | na | na | na | na |

Social rewards is sum of three separate scales: fighting, stealing, robbery.

Punishment costs and substance abuse dependence are counts.

Comparative fit index. See Bentler (1990).

Root mean square of error of approximation. See Kline (1998).

1. Self-Reported Offending and Criminal History

a. Delinquent Activity

A 24-item self-reported offending scale was adapted from Huizinga et al. (1991) to measure involvement in antisocial and illegal activities. The 24-item additive scale included items about any participation in each type of delinquent behavior over the past six months. Variety scores were computed as a rate of the total number of items endorsed (Thornberry & Krohn 2000). We computed offending variety scores to measure each of three different types of behaviors in the past year: total offending (24 items, α = 0.884), aggressive offending (11 items, sample item: “Have you ever beaten up, threatened, or physically attacked someone?” α = 0.744), and income offending (11 items, sample item: “Have you ever entered or broken into a building to steal something?” α = 0.798).

b. Court History

From court records, we computed the number of prior court cases, the number of prior charges, and the number of prior drug charges for each participant.

2. Costs and Rewards of Offending

a. Social and Personal Rewards and Costs of Offending

Measures for personal and social costs and rewards were adapted for this study to measure the adolescent's perceived likelihood of detection and punishment for any of several types of offenses (Nagin & Paternoster 1993), the social and personal costs of punishment (Williams & Hawkins 1986; Grasmick & Bursik 1990), and the social and personal rewards of offending (Fagan & Wilkinson 1998b; Anderson 1999). Separate scales were developed along five dimensions: certainty of punishment (others & you) (e.g., “How likely is it that kids in your neighborhood would be caught and arrested for fighting?”), social costs of punishment (e.g., “If the police catch me doing something that breaks the law, how likely is it that I would be suspended from school?” α = 0.679), social rewards of crime (stealing, fighting, & robbery) (e.g., “If I take things, other people my age will respect me more”),4 and personal rewards of crime (e.g., “How much ‘thrill’ or ‘rush’ is it to break into a store or home?” α = 0.874).

b. Punishment Costs

For this project, we developed original scales to measure the extent to which the deprivation of liberty associated with correctional punishment is a personal burden that weighs cognitively and emotionally on young offenders and that in turn might influence their decisions to engage in crime once they obtain their freedom. Separate scales were developed for deprivation of everyday freedoms (e.g., “Has your court sentence kept you from hanging out with your friends as much as you used to?”), and material costs (e.g., “Has your court sentence kept you from buying things that you want, like music or videos?” Has your court sentence stopped you from being in a warm or comfortable place?”). An additive scale was computed based on the total number of items endorsed.

3. Procedural Justice

Procedural justice represents perceived quality of interactions with legal actors, including police, school security officers, and store security staff. We adopted measures used by Lind et al. (1990 (cited in Tyler & Lind 1992), 1990) and Paternoster et al. (1997) to assess procedural justice. The subscales are based on recent encounters with legal actors (e.g., ethicality, fairness, representation, consistency, respect, correctability: “During your last contact with the police when you were accused of a crime, how much of your story did the police let you tell?” “Think back to the last time you were before a judge because of something you were accused of doing. Did the judge treat you with respect and dignity or did he/she disrespect you?”). These measures have been shown to be robust predictors of legal compliance under a wide range of sampling and measurement conditions, including general population surveys, criminal justice defendants, mediation and arbitration participants, persons filing workplace grievances, and participants in tort litigation (Tyler & Lind 1992:124–37). These measures have only more recently been extended to persons in the criminal justice system (Paternoster et al. 1997) and to adolescents (Fagan & Tyler 2005).

We disaggregated interactions between police and courts, and developed separate measures for both the respondent's experiences and his or her assessments of how similarly situated youths are treated by the police and the courts.

4. Legal Socialization

a. Legal Cynicism

Following Sampson and Bartusch (1998), we modified Srole's (1956) legal anomie scale to create a measure of legal cynicism that assesses general values about the normative basis of law and social norms. The items assess whether laws or rules are not considered binding in the existential, present lives of respondents (Sampson & Bartusch 1998). Respondents are asked to report their level of agreement with five statements, such as “laws are made to be broken” and “there are no right or wrong ways to make money.” The measure is computed as the mean of the five items. Reliability across waves was adequate (α = 0.572).

b. Legitimacy

We adapted Tyler's (1990, 1997) measure of legitimacy of law and legal actors. Items measured respondent's perception of fairness and equity of legal actors in their contacts with citizens, including both police contacts and court processing (Tyler & Lind 1992; Tyler 1997; Tyler & Huo 2002). The scales measure the experiential basis for translating interactions with legal processes into perceptions and evaluations of the law and the legal actors that enforce it. Respondents indicate their agreement with 11 statements, such as “overall, the police are honest,” and “the basic rights of citizens are protected by the courts.” The measure is computed as the mean for the 11 items; reliability across waves was high (α = 0.786).

5. Mental Health, Maturity, and Substance Dependency

We included covariates in three domains to incorporate factors that are potential modifiers of both rational choice and developmental influences on criminal behavior: mental health, substance abuse, and psychosocial maturity.

a. Mental Health

We use the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) Global Symptom Index to measure current general psychopathology and psychological distress (Derogatis & Melisara 1983). The BSI is a 53-item self-report inventory in which participants rate the extent to which they have been bothered (“not at all” to “extremely”) in the past week by various symptoms (e.g., “Having to check and double-check what you do”; “Faintness or dizziness”; “Feeling inferior to others”; “Feeling tense or keyed up”). We use the global psychological distress subscale (GSI). Reliability for the Global Severity Index (GSI) is reported as 0.953 (Derogatis & Melisara 1983).

b. Psychosocial Maturity

The Psychosocial Maturity Inventory (PSMI Form D) (Greenberger et al. 1974) has been used in previous research and shown excellent validity and psychometric properties (Greenberger & Bond 1976). The scale contains 30 items to which participants respond on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” We use the summary score for the 30 items (α = 0.890), which includes items from three domains: personal responsibility or self-reliance (i.e., feelings of internal control and the ability to make decisions without extreme reliance on others; “luck decides most things that happen to me”—reverse coded), identity (i.e., self-esteem, clarity of the self, and consideration of life goals; “I change the way I feel and act so often that I sometimes wonder who the ‘real’ me is”—reverse coded), and work orientation (i.e., pride in the successful completion of tasks; “I hate to admit it, but I give up on my work when things go wrong”—reverse coded).

c. Substance Abuse

We use the Substance Abuse Dependency Scale, part of the Substance Use/Abuse Inventory developed by Chassin et al. (1991) in a study of children of alcoholics. This measure considers the adolescent's use of illegal drugs and alcohol over the course of his or her lifetime and in the past six months. We use the items measuring dependence in the most recent six months preceding each interview. Since it is a count score, no psychometrics were computed.

The self-report measure for dependency includes self-report items that describe symptoms including conflicts when intoxicated, failed efforts to stop, physical symptoms of withdrawal, and compulsion to get high or drunk (e.g., “Have you ever had problems or arguments with family or friends before because of your alcohol or drug use?” “Have you ever wanted a drink or drugs so badly that you could not think about anything else?” “Have there been times when you stopped, cut down, or went without drinking/using drugs and then experienced symptoms like fatigue, headaches, diarrhea, the shakes, or emotional problems?” “Have you tried to cut down on alcohol/drugs but found that you couldn't?”).

D. Analysis

We estimated individual growth curve models to identify the effects of the theoretical variables on patterns of self-reported offending over four years following the baseline assessment. Models were estimated using linear mixed models that contain both fixed and random effects (Singer 1998; Singer & Willett 2004; McCullough & Searle 2001; Raudenbush & Bryk 2002). To control for site differences, we nested subjects within sites and also controlled for sites.

We estimated models in two stages. First, to identify the relationships between legal socialization, rational choice, and procedural justice measures, we estimated models predicting, separately, legitimacy and legal cynicism. Predictors included rational choice (costs and rewards of offending) and procedural justice variables, and a set of control variables for individual differences (maturity, mental health, and substance dependency), as well as demographics and site. We use random intercepts to account for variations in starting points. We included both linear and quadratic terms for time (wave) to reflect the negative exponential distribution of the dependent variables over the five time points. Predicted values for each measure were then computed.

Next, we estimated models predicting three dimensions of self-reported offending from legal socialization (predicted values), rational choice (costs and rewards), and procedural justice. We included fixed effects both for the theoretical predictors (costs, rewards, legal socialization, procedural justice) and the same control variables. We again used random intercepts to account for variations in starting points. We again included both linear and quadratic terms for time (wave) to reflect the negative exponential distribution of the dependent variables over the time points.

In all models, we treat time as both a random and fixed effect, to explain specific time effects as well as change over time (Gelman & Hill 2007). Mixed models conceptualize growth curve models using two levels of analysis (Bryk & Raudenbush 1992; Singer & Willett 2004). The Level 1 model estimates within-person or intra-individual change over time, capturing person-specific (i.e., individual) growth rates. Here, time is treated as a random effect since we are generalizing individual effects across intervals of time. The Level 2 model estimates between-person or interindividual change in predictors that are estimated as fixed effects. This model captures between-person variability in the Level 1 predictors, or growth rates, as a function of Level 2 fixed effects predictors (see, e.g., DeLucia & Pitts 2006). To capture and estimate the effects of specific time-varying factors on the slope (or rate of change) in the dependent variable, we include an interaction of time with each predictor at each time (Singer & Willett 2004).

Following Singer and Willett (2004), we include interactions of the quadratic time measure with each of the theoretical predictors to determine the contributions of each predictor to the model. We use a quadratic measure of time (TIME2) since the distribution of the dependent variable is nonlinear. The general model form for the offending models is:

| (1) |

where LS represents each of the theoretical predictors, including legal socialization, procedural justice, and costs and rewards of offending. The cross-level interaction, LS*TIME2, identifies whether the effects of TIME differ by the levels of the theoretical predictors (LS). The model is specified with both linear and negative exponential terms for time. We estimated models with time-varying covariates for each of the theoretical measures and for the covariates, where both slopes and intercepts vary; residual observations within subjects are correlated through the within-tract error-covariance matrix. We use an autoregressive covariance structure to reflect the within-subject correlation in self-reported offending over time. We use REML methods to develop linear contrasts of the response variable that do not depend on the fixed effects but depend instead on the variance components to be estimated.

III. Results

A. Legal Socialization

In the integrated theory, we specify each dimension of legal socialization as the product of the interactions of individuals with law. That is, we hypothesize that perceptions of procedural justice in respondents’ direct and vicarious experiences with legal actors would influence the evaluation of the legal institutions those authorities represent, and the internalization of their underlying norms and law. We also assume that characteristics of the sanctioning context influence legal socialization. Since law and legal actors also influence the sanctioning environment, we hypothesize that perceived sanction risks and rewards would reflect the internalization of legal norms as expressed by legal actors. To examine these relationships, we began with models to assess the contributions of rational choice and procedural justice influences on two dimensions of legal socialization over time.

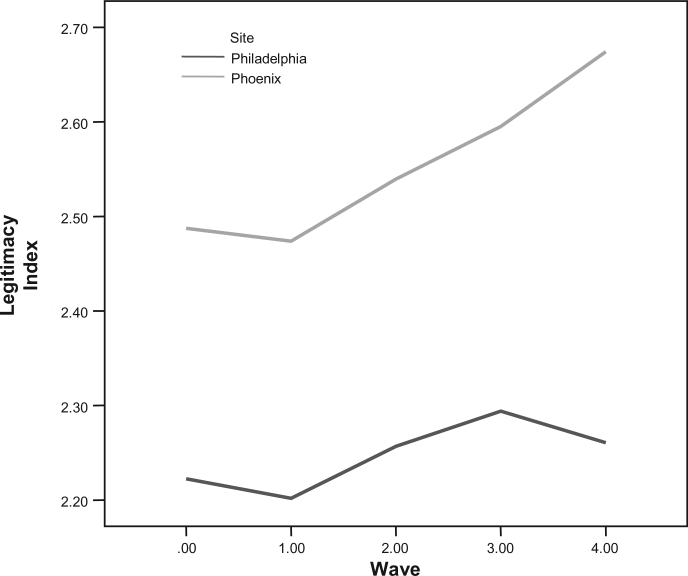

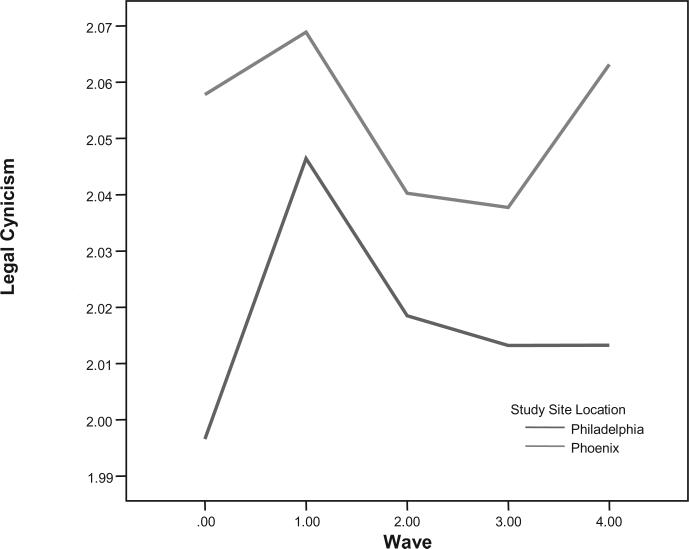

Figures 2 and 3 show the changes in each dimension of legal socialization over time. Changes are small and the patterns differ. Legitimacy declines slightly from the first to the second wave, but then increases steadily from Waves 2 through 6. The pattern of change in legal cynicism is inconsistent over time, and changes from one wave to the next, whether increasing or declining, are small. The differences over time in the trajectories of each dimension of legal socialization suggests that they be estimated as separate constructs, and included separately in the second stage models of offending.

Figure 2.

Legitimacy index by wave and study site.

Figure 3.

Legal cynicism by wave and study site.

Table 4 shows the results of the legal socialization models. Following Singer and Willett (2004), we focus on the interactions of each predictor with time (exponentiated) to identify significant predictors. For legitimacy, the first column of Table 4 shows that both rational choice and procedural justice components influence legitimacy over time, but the effects are in the opposite direction of the predictions. Punishment risk is a significant but negative influence on legitimacy: when punishment risks are higher, perceived legitimacy is lower over time. Similarly, social costs, or stigma costs, also are significant but negative predictors over time. Both dimensions of procedural justice are significant and positive predictors of legitimacy, as expected. So, too, is one of the dimensions of punishment costs. The contrasting influences of law show the importance of disaggregating evaluations of outcome- versus process-based dimensions of legal interactions.

Table 4.

Mixed Effects Regression of Theoretical Factors on Two Dimensions of Legal Socialization*

|

Legitimacy |

Legal Cynicism |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | t | p(t) | Estimate | t | p(t) |

| Wave | 0.010 | 1.23 | –0.010 | –1.13 | ||

| Time2 | –1.009 | –6.80 | a | –0.274 | –1.95 | d |

| Legitimacy | –0.094 | –5.03 | a | |||

| Legal cynicism | –0.095 | –5.54 | a | |||

| Punishment risk | 0.113 | 11.10 | a | –0.053 | –4.90 | a |

| Personal rewards | –0.014 | –1.84 | d | –0.022 | –2.89 | b |

| Social rewards | –0.010 | –0.52 | 0.161 | 8.53 | ||

| Social costs | 0.007 | 1.46 | –0.002 | –0.44 | ||

| Punishment costs—freedom | 0.007 | 0.97 | 0.001 | 0.10 | ||

| Punishment costs—material | –0.009 | –3.18 | a | 0.001 | 0.26 | |

| Procedural justice—police | 0.151 | 7.57 | a | –0.050 | –2.40 | c |

| Procedural justice—court | 0.184 | 9.53 | a | –0.009 | –0.43 | |

| Interactions—Time2 with | 0.016 | 0.42 | ||||

| Legitimacy | ||||||

| Legal cynicism | 0.035 | 1.12 | ||||

| Punishment risk | –0.067 | –3.63 | a | –0.010 | –0.52 | |

| Social reward | –0.037 | –1.10 | 0.001 | 0.02 | ||

| Social cost | 0.055 | 3.13 | b | –0.025 | –1.29 | |

| Personal reward | 0.002 | 0.16 | 0.016 | 1.08 | ||

| Punishment costs—freedom | –0.018 | –1.47 | 0.015 | 1.17 | ||

| Punishment costs—material | 0.014 | 3.29 | a | –0.004 | –0.90 | |

| Procedural justice—police | 0.167 | 4.22 | a | 0.068 | 1.54 | |

| Procedural justice—judge | 0.095 | 2.51 | c | –0.011 | –0.26 | |

| –2LL | –7155.2 | –7781.3 | ||||

| BIC | –7180.8 | –7806.9 | ||||

All estimates controlled for site, demographic characteristics, prior court record, incarceration, psychosocial maturity, mental health symptoms, and drug dependence symptoms.

Significance:

p < 0.001

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

The right half of Table 4 suggests that neither rational choice nor procedural justice factors influence legal cynicism over time. The upper half of the column shows that while some components of risk, reward, and procedural justice explain differences averaged across waves, the lower half shows that there are few influences among the theoretical predictors that explain change over time. One reason might be that there is so little change to explain: Figure 3 shows little overall change over time, despite the incremental small increases and declines from one wave to the next.

B. Self-Reported Offending

Figure 1 suggests that rational choice and procedural justice factors are direct influences on self-reported offending, as well as indirect influences that are mediated by legal socialization. Accordingly, we estimated models for each of three types of self-reported offending that include the predicted values for legitimacy and legal cynicism from the models in Table 4, and direct influences of rational choice and procedural justice variables. Results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mixed Effects Regression of Theoretical Factors on Three Types of Self-Reported Offending*

|

SRO Variety |

Aggression |

Income |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | t | p(t) | Estimate | t | p(t) | Estimate | t | p(t) |

| Wave | 0.015 | 8.40 | a | 0.008 | 4.22 | a | 0.020 | 9.08 | a |

| Time2 | 0.264 | 6.16 | a | 0.210 | 4.71 | a | 0.304 | 5.89 | a |

| Legitimacy (predicted) | –0.039 | 1.37 | –0.036 | –3.71 | a | –0.040 | –3.55 | a | |

| Legal cynicism (predicted) | 0.020 | 8.40 | a | 0.019 | 2.14 | c | 0.017 | 1.73 | d |

| Punishment risk | 0.003 | 1.25 | 0.001 | 0.54 | 0.001 | 0.48 | |||

| Personal rewards | 0.000 | –4.08 | a | 0.002 | 1.35 | 0.000 | 0.09 | ||

| Social rewards | 0.007 | 2.33 | c | 0.004 | 1.01 | 0.008 | 1.63 | ||

| Social costs | –0.001 | 1.25 | –0.001 | –1.11 | 0.000 | –0.05 | |||

| Punishment costs—freedom | –0.001 | 0.14 | –0.002 | –0.90 | –0.001 | –0.57 | |||

| Punishment costs—material | 0.000 | 1.75 | d | 0.001 | 2.19 | c | 0.000 | –0.47 | |

| Procedural justice—police | 0.000 | –0.66 | 0.001 | 0.23 | –0.002 | –0.35 | |||

| Procedural justice—court | 0.002 | –0.79 | –0.001 | –0.22 | 0.004 | 0.63 | |||

| Interactions—Time2 with | |||||||||

| Legitimacy (predicted) | –0.031 | –1.86 | d | –0.034 | –1.93 | d | –0.034 | –1.68 | d |

| Legal cynicism (predicted) | 0.027 | 2.12 | b | 0.025 | 1.92 | d | 0.026 | 1.70 | d |

| Punishment risk | –0.043 | –9.33 | a | –0.036 | –7.48 | a | –0.044 | –7.91 | a |

| Social reward | 0.025 | 3.00 | b | 0.035 | 4.06 | a | 0.028 | 2.79 | b |

| Social cost | 0.005 | 1.10 | 0.006 | 1.34 | 0.006 | 1.12 | |||

| Personal reward | 0.009 | 2.72 | b | 0.003 | 1.04 | 0.010 | 2.52 | c | |

| Punishment costs—freedom | –0.003 | –0.95 | –0.001 | –0.46 | –0.004 | –1.26 | |||

| Punishment costs—material | 0.003 | 3.35 | b | 0.001 | 1.17 | 0.005 | 3.88 | a | |

| Procedural justice—police | –0.008 | –0.77 | –0.008 | –0.69 | –0.008 | –0.59 | |||

| Procedural justice—judge | 0.013 | 1.21 | 0.022 | 2.04 | c | 0.014 | 1.08 | ||

| –2LL | –7554.6 | –7106.1 | –5620.5 | ||||||

| BIC | –7529.1 | –7080.4 | –5594.9 | ||||||

All estimates controlled for site, demographic characteristics, prior court record, incarceration, psychosocial maturity, mental health symptoms, and drug dependence symptoms.

Significance:

p < 0.001

p < 0.01

p < 0.05.

Results for total self-reported crimes appear in the first column in Table 5. Elements of each of the theoretical domains are significant predictors of each of the three different types of self-reported crime over time. Again, we focus on the interactions of each predictor with time (exponentiated) to identify influences on patterns of offending over time. Both legitimacy and legal cynicism are significant predictors of self-reported offending in the expected directions, but legitimacy only predicts at a less conservative threshold of p < 0.10. Sanction risk (punishment risk) and both personal and social rewards of crime also predict self-reported offending, again showing the tension between costs and rewards and hinting at a rational calculus of crime among young offenders. One of the two punishment cost factors—material costs—also predicts self-reported offending. Social costs are not significant in this model. Here, then, there is good support for rational choice elements predicting self-reported crime over time, but weaker support for legal socialization. The affective or experiential component of law, procedural justice, is not significant.

For aggressive offending, the second column in Table 4 shows a similar pattern. Both legal socialization variables are significant predictors of trajectories of aggressive offending, but at the less exacting threshold of p < 0.10. Punishment risk and social rewards are both significant predictors, showing that a strong tension between risk and reward exists for aggressive offending. Personal rewards, or “thrills,” is not significant in this model, indicating that perhaps the rewards of aggression derive from its functional benefits—especially status—rather than its visceral enjoyment. In this model, procedural justice is significant, but in a direction not predicted by theory. Fair and respectful treatment by judges predicts higher rates of aggressive offending. This might hint at the limits, if not the downside, of judicial philosophies that are oriented toward a therapeutic courtroom rather than a harsh procedural or sanctioning judicial process.

The results for income offending are similar to the results for total offending. Elements of risk (punishment risk), reward (social and personal rewards), and cost (material punishment costs) are significant predictors of self-reported income offending. Again, there is tension between elements of rational choice, with lesser but nevertheless important contributions of legal socialization processes. Procedural justice is not significant here, but may be doing its work through its contributions to legitimacy.

IV. Discussion

These results suggest that there are processes of legal socialization and rational choice that influence patterns and trajectories of self-reported offending among serious juvenile offenders. Legal socialization includes two distinct dimensions that reflect different perceptual frameworks for how adolescents evaluate law and legal institutions. Each component directly affects criminal behavior over a two-year period following a court appearance and sanction. We also observe direct effects of factors associated with rational choice theories. Both the perception of sanction risk and evaluations of experienced punishment compete with perceived and experienced rewards of crime to influence patterns of offending over time. These work both indirectly through legal socialization, especially through legitimacy, and directly on decisions to engage in or desist from crime.

Procedural justice also influences offending, but its effects are mediated by legitimacy. Evaluations of respondents’ interaction quality with police and judges influences legitimacy over time, although it has no influence on legal cynicism. Although legal cynicism directly influences offending, the factors that seem to shape its trajectory over time lie outside this theoretical framework, perhaps in other developmental domains that are more influenced by personality and other individual-level variables than the social interactionist constructs in this theoretical framework.

The process of legal socialization influences offending trajectories over a relatively short time period of two years following court appearance and sentence. Perhaps the experience of sanctions activates these processes, but we find little sanction sensitivity to specific types of punishment costs. Instead, we observe that perceptions of law and legal actors, and evaluations of the sanctioning environment that they create, contribute to variation in offending patterns over time. Evaluations of the legitimacy of law and legal authorities grow slowly but steadily over time, contributing to the decline in offending in the initial waves and to lower crime rates in later waves.

These findings comport well with those of studies of general population samples of adults (Sunshine & Tyler 2003; Tyler 1990; Tyler & Huo 2002), and community samples of adolescents (Fagan & Tyler 2005). Since most youth crime is committed by the types of adolescents in this study, the findings suggest the importance of focusing on socialization to better understand when and how values are acquired, even among active juvenile offenders. Theories of legitimacy and legitimation become more important if the values that are at their focus play an important role in the legal system. One way that they could do so is by shaping law-related behavior, since social order depends on widespread compliance with the law. This study supports general population studies of both juveniles and adults in suggesting that they do. This extension is important, since the vast majority of crimes are committed by adolescents. Based on the findings of this study, it can be argued that beginning in adolescence, legitimacy is an important value shaping law-related behavior.

This study also helps us understand how legitimation occurs. Prior studies suggest that people's views about the legitimacy of authority are primarily linked to their evaluations of the procedures by which the police and courts operate. This study supports this procedural justice argument among adolescents. Like adults, adolescent views about the legitimacy of authority are influenced by procedural justice judgments about their own and others’ experiences with the police. The finding that procedural justice issues matter to adolescents is consistent with the results of several other recent studies. Fondacaro and his colleagues (1998) found that the procedural justice by which parents resolve family disputes influences rule following in both family and community contexts. Also, Otto and Dalbert (2005) found that whether incarcerated adolescents felt guilt over their crimes was shaped by whether they viewed their trial as fairly conducted.

Of course, the process of socialization involves the development and internalization of broader range of norms and values, including attitudes toward democracy, views about other social groups, and tolerance of diversity. Further, it leads to many forms of potentially important behavior. Engagement in communities and in the political process is important, and is linked to values learned in childhood (Flanagan & Sherrod 1998). Accordingly, it is important to emphasize that this study concerns only one aspect of the general process of value socialization, as well as speaking to only one form of socially relevant behavior.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by generous grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation through the MacArthur Research Network on Adolescent Development and Juvenile Justice. Additional major funding was provided by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Justice, the State of Arizona, and the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency. This study is part of a collaboration among investigators at the University of Pittsburgh, Columbia University, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, the University of South Carolina, Temple University, and Arizona State University, who have guided the development and execution of the study. We are grateful for the heroic efforts of the interviewers in Philadelphia and Phoenix, whose labors have produced the data infrastructure for this research. John Laub, Edward Mulvey, Carol Schubert, and participants at the First Annual Conference on Empirical Legal Studies at The University of Texas Law School provided helpful comments on earlier drafts. All opinions and errors are our own.

Appendix A.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients (Two-Tailed) for Predictors and Dependent Variables

| SRO— General |

SRO— Aggressive |

SRO— Income |

Legitimacy | Legal Cynicism |

Punishment Risk |

Personal Rewards |

Social Rewards |

Social Costs |

Punishment Costs— Freedom |

Punishment Costs— aterial |

Procedural Justice— Police |

Procedural Justice— Judge |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRO —General |

1.000 | 0.917 | 0.945 | –0.177 | 0.192 | –0.167 | 0.303 | 0.315 | –0.024 | 0.135 | 0.141 | –0.157 | –0.062 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.081 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| SRO —Aggressive |

0.917 | 1.000 | 0.792 | –0.172 | 0.187 | –0.154 | 0.298 | 0.309 | –0.027 | 0.126 | 0.137 | –0.151 | –0.067 |

| 0.000 | . | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| SRO —Income |

0.945 | 0.792 | 1.000 | –0.153 | 0.170 | –0.150 | 0.282 | 0.292 | –0.014 | 0.128 | 0.132 | –0.140 | –0.044 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | . | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.316 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | |

| Legitimacy | –0.177 | –0.172 | –0.153 | 1.000 | –0.220 | 0.296 | –0.070 | –0.113 | 0.116 | –0.067 | –0.106 | 0.396 | 0.415 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Legal cynicism |

0.192 | 0.187 | 0.170 | –0.220 | 1.000 | –0.160 | 0.245 | 0.335 | –0.053 | 0.064 | 0.049 | –0.140 | –0.110 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Punishment risk |

–0.167 | –0.154 | –0.150 | 0.296 | –0.160 | 1.000 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.092 | –0.024 | –0.057 | 0.177 | 0.143 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | 0.547 | 0.998 | 0.000 | 0.080 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Personal rewards |

0.303 | 0.298 | 0.282 | –0.070 | 0.245 | 0.008 | 1.000 | 0.835 | –0.019 | 0.062 | 0.006 | –0.055 | 0.000 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.547 | . | 0.000 | 0.163 | 0.000 | 0.646 | 0.000 | 0.991 | |

| Social rewards |

0.315 | 0.309 | 0.292 | –0.113 | 0.335 | 0.000 | 0.835 | 1.000 | –0.026 | 0.065 | 0.002 | –0.090 | –0.059 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.998 | 0.000 | . | 0.060 | 0.000 | 0.873 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Social costs | –0.024 | –0.027 | –0.014 | 0.116 | –0.053 | 0.092 | –0.019 | –0.026 | 1.000 | 0.000 | –0.017 | 0.025 | 0.044 |

| 0.081 | 0.054 | 0.316 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.163 | 0.060 | . | 0.989 | 0.234 | 0.078 | 0.002 | |

| Freedom costs | 0.135 | 0.126 | 0.128 | –0.067 | 0.064 | –0.024 | 0.062 | 0.065 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.827 | –0.080 | –0.079 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.080 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.989 | . | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Material costs | 0.141 | 0.137 | 0.132 | –0.106 | 0.049 | –0.057 | 0.006 | 0.002 | –0.017 | 0.827 | 1.000 | –0.083 | –0.108 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.646 | 0.873 | 0.234 | 0.000 | . | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| PJ—Police | –0.157 | –0.151 | –0.140 | 0.396 | –0.140 | 0.177 | –0.055 | –0.090 | 0.025 | –0.080 | –0.083 | 1.000 | 0.541 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.078 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | 0.000 | |

| PJ—Judge | –0.062 | –0.067 | –0.044 | 0.415 | –0.110 | 0.143 | 0.000 | –0.059 | 0.044 | –0.079 | –0.108 | 0.541 | 1.000 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.991 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

Appendix B.

Pearson Correlations (Two-Tailed) of Covariates with Predictors and Dependent Variables

| Incarceration at Initial Disposition |

Total Prior Charges |

Gender | Age | African American |

Latino | Psychosocial Maturity Index |

BSI— Global Symptom Inventory |

Drug Dependence |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRO General | 0.089 | –0.080 | –0.122 | 0.059 | –0.106 | 0.080 | –0.104 | 0.241 | 0.390 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| SRO—Aggressive | 0.083 | –0.063 | –0.129 | 0.018 | –0.087 | 0.083 | –0.101 | 0.244 | 0.307 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.196 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| SRO—Income | 0.079 | –0.074 | –0.100 | 0.065 | –0.108 | 0.057 | –0.098 | 0.216 | 0.394 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Legitimacy | –0.106 | –0.147 | 0.063 | –0.121 | –0.216 | 0.123 | 0.018 | –0.058 | –0.021 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.207 | 0.000 | 0.143 | |

| Legal cynicism | 0.074 | –0.018 | –0.118 | 0.038 | –0.032 | 0.106 | –0.284 | 0.106 | 0.085 |

| 0.000 | 0.210 | 0.00 | 0.007 | 0.023 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Punishment risk | –0.127 | –0.115 | 0.151 | –0.130 | –0.122 | 0.041 | –0.049 | –0.014 | –0.005 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.306 | 0.701 | |

| Personal rewards | –0.016 | –0.202 | –0.079 | –0.024 | –0.245 | 0.133 | –0.208 | 0.144 | 0.202 |

| 0.253 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.088 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Social rewards | 0.003 | –0.110 | –0.111 | –0.015 | –0.143 | 0.093 | –0.301 | 0.187 | 0.189 |

| 0.809 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.282 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Social costs | –0.033 | –0.072 | 0.035 | 0.016 | –0.091 | 0.060 | –0.008 | 0.025 | 0.020 |

| 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.263 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.557 | 0.080 | 0.153 | |

| Punishment costs—Freedom | 0.221 | 0.020 | –0.076 | 0.053 | 0.018 | –0.016 | –0.040 | 0.130 | 0.087 |

| 0.000 | 0.147 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.211 | 0.266 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Punishment costs—Material | 0.348 | 0.091 | –0.101 | 0.094 | 0.097 | –0.052 | –0.014 | 0.126 | 0.047 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.304 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |

| Procedural justice—Police | –0.040 | –0.070 | 0.044 | –0.095 | –0.032 | 0.023 | 0.034 | –0.134 | –0.065 |

| 0.005 | 0.000 | .002 | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.109 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Procedural justice—Judge | –0.099 | –0.120 | 0.049 | –0.075 | –0.132 | 0.088 | 0.031 | –0.119 | –0.011 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.000 | 0.443 |

Footnotes

Under the gambler's fallacy, punished offenders reset their sanction risk estimate, apparently believing they would have to be exceedingly unlucky to be apprehended again (Pogarsky & Piquero 2003).

Though based on the same data set, our sample differs from Schubert et al. (2004) and Mulvey et al. (2004) in two ways. First, our sample includes 1,355 subjects, one more than in previous articles. The additional case was included when consent issues were resolved at one of the research sites for a specific subject. Second, the age range in the earlier articles is 14–17, but 14–18 in this analysis. The earlier papers reported age at the time of the offense that qualified the subject for the sample. This analysis uses the age at first interview, which was a few weeks later and hence spanned age years.

The caps and quotas embedded in the sampling plan resulted in over- and undersampling of particular groups (see Schubert et al. (2004) for a discussion of the potential sample biases). For example, Schubert et al. (2004:247) report that “the imposition of a cap on the proportion of the sample adjudicated on drug charges probably affected. . . race proportionality, since in Philadelphia. . . African Americans were significantly more likely to be in the drug cap group than were other racial groups.” However, we did not assign sample weights in the analysis since we did not have complete information on the demographic, court history, and current charges of the group that was not sampled. Still, we did include the number of total charges and drug charges as covariates to capture some of the variance produced by the sampling procedure.

To avoid redundancy and multicollinearity, these three scales were combined into one. The reliability coefficients ranged from α = 0.752 to α = 0.829.

References

- Anderson E. Code of the Street. Norton; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Apospori A, Alpert GP, Paternoster R. The Effect of Involvement with the Criminal Justice System: A Neglected Dimension of the Relationship Between Experience and Perceptions. Justice Q. 1992;9(3):379. [Google Scholar]

- Beccaria C, Paolucci H. On Crimes and Punishments. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1963. [1764] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler Peter M. Comparative Fit Indexes in Structural Models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi A. Bridging Moral Cognition and Moral Action: A Critical Review of the Literature. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:1. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Application of Hierarchical Linear Models to Assessing Change. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;101:147. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Rogosch F, Barrera M. Substance Use and Symptomatology Among Adolescent Children of Alcoholics. J. of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):449. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke Ronald V., Cornish Derek B. Modeling Offenders’ Decisions: A Framework for Research and Policy. In: Tonry M, Morris N, editors. Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research. Vol. 4. Univ. of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn ES, White SO. Legal Socialization: A Study of Norms and Rules. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Decker SH, Wright RT, Logie R. Criminal Expertise and Offender Decision Making: An Experimental Study of the Target Selection Process in Residential Burglary. J. of Research in Crime & Delinquency. 1995;32(1):39. [Google Scholar]

- DeLucia C, Pitts Steven C. Applications of Individual Growth Curve Modeling for Pediatric Psychology Research. J. of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31(6):1002. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L, Melisara N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An Introductory Report. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13(3):595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton D. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. Univ. of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Easton D, Dennis J. Children in the Political System. Univ. of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J. Do Criminal Sanctions Deter Drug Offenders? In: MacKenzie D, Uchida C, editors. Drugs and Criminal Justice: Evaluating Public Policy Initiatives. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1994. pp. 188–214. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Freeman RB. Crime and Work. Crime & Justice: A Rev. of Research. 1999;25:113. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Tyler TR. Legal Socialization of Children and Adolescents. Social Justice Research. 2005;18(2):217. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Wilkinson DL. Guns, Youth Violence and Social Identity. In: Tonry M, Moore MH, editors. Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research. Vol. 24. Univ. of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1998a. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Wilkinson DL. The Social Contexts and Developmental Functions of Adolescent Violence. In: Elliott DS, Hamburg BA, Williams KR, editors. Violence in American Schools. Cambridge Univ. Press; New York: 1998b. pp. 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan CA, Sherrod LR. Youth Political Development: An Introduction. J. of Social Issues. 1998;54(3):447. [Google Scholar]

- Fondacaro MR, Dunkle M, Pathak MK. Procedural Justice in Resolving Family Disputes: A Psychosocial Analysis of Individual and Family Functioning in Late Adolescence. J. of Youth & Adolescence. 1998;27(1):101. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman Andrew, Hill Jennifer. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge Univ. Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs JP. Crime, Punishment, and Deterrence. Elsevier Scientific Publishing Co.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein PJ. The Drugs-Violence Nexus: A Tri-Partite Conceptual Framework. J. of Drug Issues. 1985;15:493. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein PJ. Drugs and Violent Crime. In: Weiner NA, Wolfgang ME, editors. Pathways to Criminal Violence. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1989. pp. 16–48. [Google Scholar]

- Grasmick HG, Bursik RJ., Jr. Conscience, Significant Others, and Rational Choice: Extending the Deterrence Model. Law & Society Rev. 1990;24(3):837. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Bond L. Technical Manual for the Psychosocial Maturity Inventory. Program in Social Ecology, University of California; Irvine, CA: Irvine: 1976. unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Josselson R, Knerr C, Knerr B. The Measurement and Structure of Psychosocial Maturity. J. of Youth & Adolescence. 1974;4:127. doi: 10.1007/BF01537437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein F. Children and Politics. Yale; New Haven, CT: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Hess Robert D., Torney Judith V. The Development of Political Attitudes in Children. Aldine; Chicago, IL: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman M. Empathy and Moral Development. Cambridge Univ. Press; Cambridge: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Esbensen Finn-Aage, Weiher Anne. Are There Multiple Paths to Delinquency? J. of Criminal Law & Criminology. 1991;82(1):83. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Jakob-Chien C. The Contemporaneous Co-Occurrence of Serious and Violent Juvenile Offending and Other Problem Dehaviors. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1999. pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman H. Political Socialization. Free Press; New York: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Katz J. Seductions of Crime. Basic Books; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of DSM-III-R Psychiatric Disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Krislov S, Boyum KO, Clark JN, Shaefer RC, White SO. Compliance and the Law. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Laub JH, Sampson RJ. Understanding Desistance from Crime. Crime & Justice. 2001;28:1. [Google Scholar]

- Lind EA, Kanfer R, Earley PC. Voice, Control, and Procedural Justice: Instrumental and Noninstrumental Concerns in Fairness Judgments. J. of Personality & Social Psychology. 1990;59:952. [Google Scholar]

- Lind EA, MacCoun RJ, Enener PA, Felstiner WLF, Hensler DR, Resnik J, Tyler TR. In the Eyes of the Beholder: Tort Litigants’ Evaluations of Their Experiences in the Civil Justice System. Law & Society Rev. 1990;24(4):953. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Monahan J, Stueve A, Cullen FT. Real in Their Consequences: A Sociological Approach to Understanding the Association Between Psychotic Symptoms and Violence. American Sociological Rev. 1999;64:316. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Stueve A, Phelan J. Psychotic Symptoms and Violent Behaviors: Probing the Components of ‘Threat/Control-Override’ Symptoms. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33:S55. doi: 10.1007/s001270050210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner L. Individual Perceptions of the Criminal Justice System. 2005. unpublished manuscript. NBER.

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB. Multiple Risk Factors for Multi-Problem Boys: Co-Occurrence of Delinquency, Substance Use, Attention Deficit, Conduct Problems, Physical Aggression, Covert Behavior, Depressed Mood, and Shy/Withdrawn Behavior. In: Jessor R, editor. New Perspectives on Adolescent Risk Behavior. Cambridge Univ. Press; New York: 1998. pp. 90–149. [Google Scholar]

- Maroney Terry A. USC Legal Studies Research Paper 06-3. University of Southern California Law School; 2006. Emotional Competence, ‘Rational Understanding’, and the Criminal Defendant. [Google Scholar]

- Matsueda RL, Kreiger DA, Huizinga D. Deterring Delinquents: A Rational Choice Model of Theft and Violence. American Sociological Rev. 2006;71:95. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy B. New Economics of Sociological Criminology. Annual Rev. of Sociology. 2002;28:417. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough CE, Searle SR. Generalized, Linear and Mixed Models. Wiley; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Melton GB. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Vol. 33. Univ. of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, NE: 1985. The Law as a Behavioral Instrument. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merelman RJ. Revitalizing Political Socialization. In: Herman HG, editor. Political Psychology: Contemporary Problems and Issues. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey EP, Steinberg L, Fagan J, Cauffman E, Piquero AR, Chassin L, et al. Theory and Research on Desistance from Antisocial Activity Among Serious Adolescent Offenders. Youth Violence & Juvenile Justice. 2004;2(3):213. doi: 10.1177/1541204004265864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussen P, Eisenberg-Berg Nancy. Roots of Caring, Sharing, and Helping. Freeman; San Francisco, CA: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Criminal Deterrence Research at the Outset of the Twenty-First Century. In: Tonry M, editor. Crime and Justice: A Review of Research. Vol. 23. Univ. of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Paternoster R. Enduring Individual Differences and Rational Choice Theories of Crime. Law & Society Rev. 1993;27:467. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Pogarsky G. Integrating Celerity, Impulsivity, and Extralegal Sanction Threats into a Model of General Deterrence: Theory and Evidence. Criminology. 2001;39(4):404. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Pogarsky G. An Experimental Investigation of Deterrence: Cheating, Self-Serving Bias, & Impulsivity. Criminology. 2003;41(3):501. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Pogarsky G. Time and Punishment: Delayed Consequences and Criminal Behavior. J. of Quantitative Criminology. 2004;20(3):295. [Google Scholar]

- Niemi RG. Political Socialization. In: Knutson JN, editor. Political Psychology. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Otto K, Dalbert C. Belief in a Just World and its Functions for Young Prisoners. J. of Research in Personality. 2005;6(4):559. [Google Scholar]

- Paternoster R. The Deterrent Effect of the Perceived Certainty and Severity of Punishment: A Review of the Evidence and Issues. Justice Q. 1987;4(2):173. [Google Scholar]

- Paternoster R, Brame R, Bachman R, Sherman LW. Do Fair Procedures Matter? The Effect of Procedural Justice on Spouse Assault. Law & Society Rev. 1997;31:163. [Google Scholar]