Abstract

Dopamine-releasing neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta produce an extraordinarily dense and expansive plexus of innervation in the striatum converging with glutamatergic corticostriatal and thalamostriatal axon terminals at dendritic spines of medium spiny neurons. Here, we investigated whether glutamatergic signaling promotes arborization and growth of dopaminergic axons. In postnatal ventral midbrain cultures, dopaminergic axons rapidly responded to glutamate stimulation with accelerated growth and growth cone splitting when NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptors were activated. In contrast, when AMPA/kainate receptors were selectively activated, axon growth rate was decreased. To address whether this switch in axonal growth response was mediated by distinct calcium signals, we used calcium imaging. Combined NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptor activation elicited calcium signals in axonal growth cones that were mediated by calcium influx through L-type voltage-gated calcium channels and ryanodine receptor-induced calcium release from intracellular stores. AMPA/kainate receptor activation alone elicited calcium signals that were solely attributable to calcium influx through L-type calcium channels. We found that inhibitors of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases prevented the NMDA receptor-dependent axonal growth acceleration, whereas AMPA/kainate-induced axonal growth decrease was blocked by inhibitors of calcineurin and by increased cAMP levels. Our data suggest that the balance between NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptor activation regulates the axonal arborization pattern of dopamine axons through the activation of competing calcium-dependent signaling pathways. Understanding the mechanisms of dopaminergic axonal arborization is essential to the development of treatments that aim to restore dopaminergic innervation in Parkinson's disease.

Introduction

A relatively small number of nigrostriatal neurons provides a dense and fairly uniform dopaminergic innervation of the striatum (Smith et al., 1994; Gauthier et al., 1999; Moss and Bolam, 2008). Individual nigrostriatal neurons possess extraordinarily dense and widespread axonal arbors, covering ∼3% of the striatal volume, thereby reaching ∼75,000 striatal cells (Matsuda et al., 2009). Dopaminergic axon terminals converge with corticostriatal and thalamostriatal terminals onto spines of medium spiny neurons and are often in direct apposition to glutamatergic axons, so that >80% of glutamatergic terminals are within 1 μm of a dopaminergic axon and thus exposed to local dopamine release (Bouyer et al., 1984; Moss and Bolam, 2008). Reciprocally, dopaminergic axons express glutamate receptors both during development and in the adult brain (Tallaksen-Greene et al., 1992; Gracy and Pickel, 1996; Zhang and Sulzer, 2003), indicating that they potentially respond to glutamate input.

Although effects of neurotransmitters on neuronal morphology have been thought to occur mostly postsynaptically at dendritic spines, there is increasing evidence for a role of local neurotransmission in shaping axonal structures as well (De Paola et al., 2003; Muller and Nikonenko, 2003; Gogolla et al., 2007). Direct effects of glutamate on axonal growth have been mostly investigated in cultured neurons. Studies on hippocampal neurons reported that high levels of glutamate, quisqualate, and kainate inhibited axonal growth (Mattson et al., 1988; Brewer and Cotman, 1989; McKinney et al., 1999). In contrast, in dissociated embryonic Xenopus spinal neurons, newly formed neurites turned toward a local gradient of glutamate in a concentration-dependent manner (Zheng et al., 1996). Recent studies in hippocampal cell cultures and brain slices also reported concentration-dependent effects of local presynaptic AMPA/kainate receptor stimulation on the motility of axon terminals and growth cone filopodia (Chang and De Camilli, 2001; De Paola et al., 2003; Tashiro et al., 2003; Ibarretxe et al., 2007). Thus, the axonal growth response to glutamate may depend on the cell type, the age of the cell, the concentration of glutamate, and the glutamate receptor type.

We report here that postnatal dopaminergic neurons that were allowed to form axonal arbors for 5–9 d in culture responded rapidly to a short, global activation of NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptors with acceleration of axonal growth and growth cone splitting, and to AMPA/kainate receptor activation alone with a decrease of axonal growth rate, and that these different responses were mediated by different calcium-dependent second messenger systems.

Materials and Methods

TH-GFP mice and cell culture.

Ventral midbrain cultures (including substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area) were prepared from mice expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) under the promoter for tyrosine hydroxylase [TH-GFP mice, kindly provided by Kazuto Kobayashi, Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, Japan (Sawamoto et al., 2001)]. The handling, anesthesia, and killing of mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals guidelines. Cultures were prepared from 0 to 3 d old litters of TH-GFP +/−/wild-type mice crossings. Ventral midbrain neurons were dissociated and plated at a density of 80,000/cm2 onto a layer of rat cortical glial cells grown on round glass coverslips and maintained in culture medium without added GDNF (glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 5–9 d (Mena et al., 1997).

Experimental reagents.

Stock solutions were prepared by dissolving drugs in water or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (1‰ maximal, final concentration) according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. Stock solutions were then diluted in Tyrode's saline (in mm: 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 HEPES sodium salt, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 30 glucose, pH 7.5; osmolarity, 330 mOsm) immediately before the experiment. Stimulus medium contained 20 μm bicuculline to block GABAA currents. The following drugs were used: l-glutamate (200 μm) (Zheng et al., 1996), (−)-bicuculline methobromide (20 μm), AMPA (50 μm) (Paternain et al., 1995), (2R)-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate (AP-5) (50 μm) (Zheng et al., 1996), and cyclosporine A (cspA) (10 nm) and sp-cAMP (250 μm) (Wen et al., 2004) (Sigma-Aldrich); (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenyl-glycine (DHPG) (100 μm) (Zhang and Sulzer, 2003), (RS)-(tetrazol-5-yl)glycine (50 μm) (Schoepp et al., 1991), 1,1′-diheptyl-4,4′-bipyridinium dibromide (DHBP) (100 μm) (Paternain et al., 1995), nitrendipine (10 μm) (Mercuri et al., 1994) (Tocris); and KN-92 and KN-93 (5 μm) (Wen et al., 2004) (Calbiochem).

Imaging axonal growth.

For axonal growth imaging experiments, cultures grown on glass coverslips were mounted in a closed imaging chamber (volume, 260 μl; RC-21BRFS; Warner Instruments) and superfused with Tyrode's solution at a flow rate of 0.5–1 ml/min at 28°C. Solutions were switched with a perfusion valve control system (Warner Instruments). Cultures were imaged with an Olympus IX81 inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus) equipped with a digitized stage (ProScan; Prior Scientific). Images were acquired at a rate of one per 10 min with a 40× objective, a fluorescence filter set for GFP (41001; Chroma), and a 2.0 neutral density filter using a Cool Snap HQ camera (Roper Scientific/Photometrics) and MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). The low acquisition rate and the use of 2.0 neutral density filters served to minimize phototoxicity. All axons that were actively growing and appeared healthy were assessed: axons were only excluded from analysis if the growth cone collapsed (∼20%), if the axon showed membrane blebs (∼5%), or if their growth rate before treatment was <5 μm/h (∼30%). Several axons were typically monitored simultaneously in one culture dish: the number of axons and the number of culture dishes is indicated in the figure legends. Typically, four to five cultures derived from a single dissection were used. The growth rate was determined by measuring the axonal extension over 1 h using MetaMorph software. Measurements taken by two observers (one blind to the conditions) differed by no more than ±8%. Differences in the cumulative frequency distribution of growth rates were tested for significance with the nonparametric Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test (http://www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/KS-test.html).

Calcium imaging.

Fura-2 AM stock solution (5 μl; 1 μg/ml DMSO; Invitrogen) was mixed with 1 μl of pluronic-F-127 solution (20% in DMSO; Invitrogen) and added to the culture dish containing 2 ml of medium. Cultures were incubated for 30 min and transferred to the imaging chamber. Calcium imaging started after a 30 min washout in Tyrode's saline. Growth cone calcium levels were imaged using a filter wheel (Prior Scientific), switching between 387 and 340 nm excitation filters (emission, 510 nm; Semrock fura-2B filter set, plus a 1.3 neutral density filter). Images were acquired at 200–500 ms exposure time at a frequency of either 0.5 or 0.25 Hz. Relative calcium levels were determined by ratiometric measurement: the average pixel intensity in the central domain of the growth cone at 340 nm was divided by the pixel intensity at 387 nm (F340/F387). Background fluorescence was measured either in a cell-free region of the viewing field or in underlying glial cells depending on the location of the growth cone, and was subtracted from the growth cone fluorescence for each frame. The relative magnitude of the peak of spontaneous calcium transients and evoked calcium signals was determined by subtracting the baseline F340/F387 value before the calcium transient from the peak value. Calcium waves with a F340/F387 ratio <0.2 were not included in the analysis. Only one axonal growth cone per culture dish was monitored; thus, n equals the number of growth cones and the number of culture dishes. ANOVA with nonparametric post hoc Dunn's test was used for statistical analysis (Prism; GraphPad Software).

Immunostaining.

Cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature (RT) and double-labeled with primary antibodies against either NR1 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen; mouse monoclonal; 1:600), or GluR1 (BD Biosciences; mouse monoclonal; 1:200), or GluR2 subunit (BD Biosciences; mouse monoclonal; 1:200), and antibodies against either TH (Calbiochem; rabbit polyclonal; 1:1000), or dopamine transporter (DAT) (Millipore; rat monoclonal; 1:1000) at 4°C overnight. After three wash steps, cultures were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen), respectively, at 1:200 for 1 h at RT.

Results

Glutamate receptor-dependent axonal growth changes

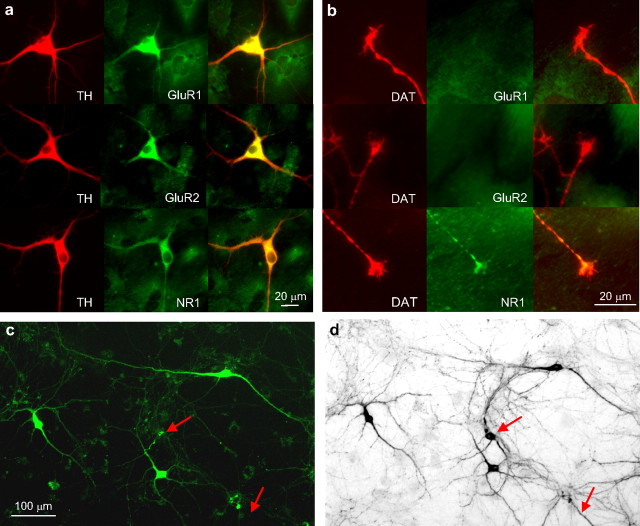

Dopaminergic midbrain neurons express ionotropic glutamate receptors in cell bodies, dendrites, and axons in the adult brain. We performed immunohistochemistry on midbrain cultures derived from postnatal day 1–3 mice, fixed after 5–7 d in cultures, to establish whether AMPA and NMDA glutamate receptors were expressed at this age under culture conditions. We used antibodies against the NR1 subunit, which is contained in all NMDA receptors, and antibodies against the AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2. Cell bodies and dendrites of TH-positive neurons were labeled with all three antibodies (Fig. 1a). Interestingly, there was clear label for the NR1 subunit in TH-positive axonal growth cones (in ∼80% of the growth cones), but no label was detected with antibodies against either GluR1 or GluR2 subunits (Fig. 1b), suggesting that effects of AMPA receptor activation on axonal growth may be mediated by somatodendritic receptors.

Figure 1.

a, b, Immunostaining of postnatal ventral midbrain cultures for TH (red), NR1, GluR1, and GluR2 (green). Cell bodies and dendrites of TH-positive neurons (a, left column) were labeled by the antibodies to all three subunits (a, middle column; right column, merge), whereas DAT-positive axonal growth cones (b, left column) were only labeled by antibodies against the NR1 subunit (b, middle column; right column, merge). c, d, Ventral midbrain cultures from TH-GPF mice. c, Fluorescence image of GFP-expressing ventral midbrain neurons in a living culture at 7 d after plating. d, Incandescence image of the same culture after fixation and immunostaining for TH (using DAB as chromophore). The arrows indicate a cell body and dendrite immunolabeled for TH that did not show detectable GFP expression before fixation.

Dissociated ventral midbrain cultures derived from mice expressing green fluorescent protein (eGFP) under the promoter for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH-GFP mice) were examined 5–9 d after plating for assessment of GFP expression. Immunostaining for TH revealed that, at this age, 60% of TH-positive neurons expressed detectable eGFP levels, whereas ectopic expression (i.e., detectable eGFP expression in TH-immunonegative neurons) was <3% (n = 3 cultures). A fluorescence image of a living culture of GFP-expressing neurons at 7 d in vitro is shown in Figure 1c, and an incandescence image of the same culture after fixation and immunostaining for TH is shown in Figure 1d.

To assess axonal growth rates in GFP-expressing neurons, axons were monitored for 1 h in control medium before and after a 3 min superfusion with stimulus medium. The median growth rate in control medium was 19.8 μm/h (excluding axons growing <5 μm/h), and the maximal growth rate was 53 μm/h.

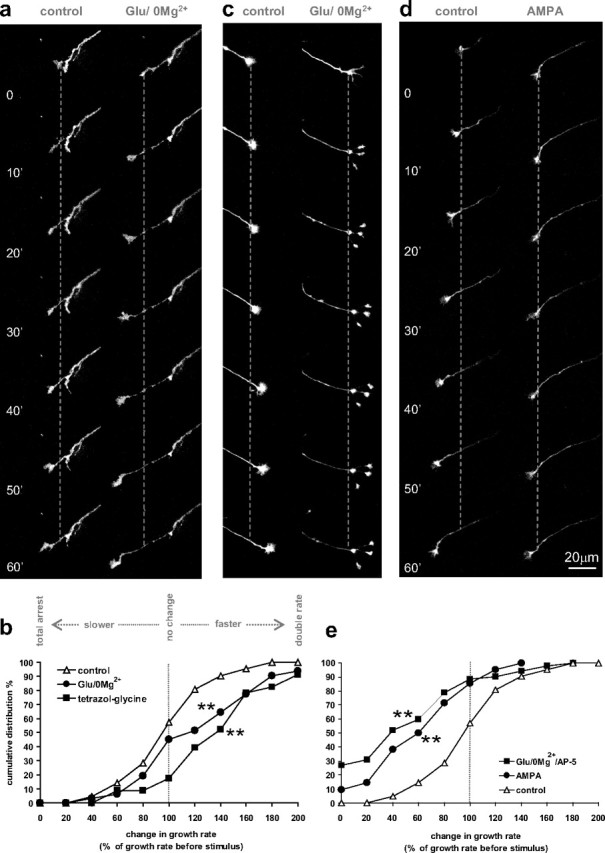

A 3 min stimulus of glutamate in Mg2+-free Tyrode's medium (glutamate/0 Mg2+) to relieve the Mg2+ block of NMDA receptors rapidly accelerated axonal growth as shown in a time series of a growing axon in the hour before and after the glutamate/0 Mg2+ stimulus (Fig. 2a). The median growth rate after glutamate/0 Mg2+ was 22.5 μm/h with a maximal rate of 80.5 μm/h. The cumulative distribution of growth rate changes after the glutamate/0 Mg2+ stimulus (as percentage of growth rate before the stimulus) is plotted compared with growth rate changes from 1 h to the next in nonstimulated axons (Fig. 2b). In control conditions (n = 23 axons, 6 cultures), axonal growth rates varied over the 2 h period, but 52% of axons remained within 80–120% of the first hour growth rate (fractions are read from the cumulative distribution graph). The glutamate/0 Mg2+ stimulus caused a clear shift toward faster growth rates with 48% of the axons increasing growth rates by >20% (n = 31 axons, 12 cultures; KS test, p < 0.01). Similarly, superfusion with the potent NMDA receptor agonist, d,l-(tetrazol-5-yl)glycine (tetrazol-glycine), shifted the distribution toward faster growth rates with 61% of the axons increasing growth rates by >20% (n = 23 axons, 13 cultures; KS test, p < 0.01). Interestingly, a splitting of the growth cone into two or three branches occurred in 18% of glutamate/0 Mg2+-stimulated axons within the first 20 min after the stimulus (Fig. 2c, example) (χ2 test, p < 0.001), and in 7% for tetrazol-glycine (p < 0.05), whereas under control conditions the incidence for spontaneous growth cone splitting during the same time interval was only 1.7%.

Figure 2.

Effects of glutamate on axonal growth in cultured dopaminergic neurons. a, c, d, Time series of axonal growth cones in cultures derived from TH-GFP mice, taken at 10 min intervals for 1 h before (left column) and after a 3 min stimulus (right column) with either 200 μm glutamate in medium lacking Mg2+ (Glu/0 Mg2+) (a, c) or 50 μm AMPA (d). The graph in b shows the cumulative frequency distribution of growth rate change from the first 1 h period before the stimulus to the second 1 h period after the Glu/0 Mg2+ stimulus (n = 31 axons, 12 dishes; black circles) and the NMDA receptor agonist tetrazol-glycine (50 μm) (n = 23 axons, 13 dishes; black squares) versus controls (white triangles; n = 23 axons, 6 dishes). In e, the growth rate change after AMPA (n = 42 axons, 9 dishes; black circles) and Glu/0 Mg2+/AP-5 (AP-5, 50 μm; n = 52 axons, 12 dishes; black squares) is plotted compared with controls (white triangles; n = 23 axons, 6 dishes). **Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, different from control, p < 0.01.

In contrast to glutamate/0 Mg2+, the AMPA/kainate receptor agonist AMPA reduced axonal growth, with the median growth rate decreasing to 10 μm/h. Figure 2d shows an example of a growth cone that advanced at the rate of 25 μm/h before the stimulus and slowed considerably to 5 μm/h after the 3 min AMPA stimulus. In the analysis of the cumulative frequency of growth rate changes in response to AMPA (Fig. 2e), a clear shift to slower growth rates is seen, with 71% of the axons decreasing growth rates by >20% (n = 42 axons, 9 cultures; KS test, p < 0.01). Similarly, superfusion with glutamate/0 Mg2+ in the presence of the NMDA receptor antagonist AP-5 (5 min before and during glutamate/0 Mg2+ superfusion) shifted the distribution to slower growth rates, with 79% of the axons decreasing growth rates by >20% (n = 52 axons, 12 cultures; KS test, p < 0.01). Growth cone splitting was never observed in response to AMPA or to glutamate/0 Mg2+ in the presence of AP-5. We also tested an agonist of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors, DHPG (100 μm), which had no effect on axonal growth rates (n = 12 axons, 4 cultures; KS test, p = 0.66) (data not shown).

These data demonstrate that axons of dopamine neurons respond to glutamate input with either growth acceleration/growth cone splitting or growth rate decrease depending on whether NMDA or AMPA/kainate receptors are activated.

Calcium signals evoked by glutamate in dopaminergic axonal growth cones

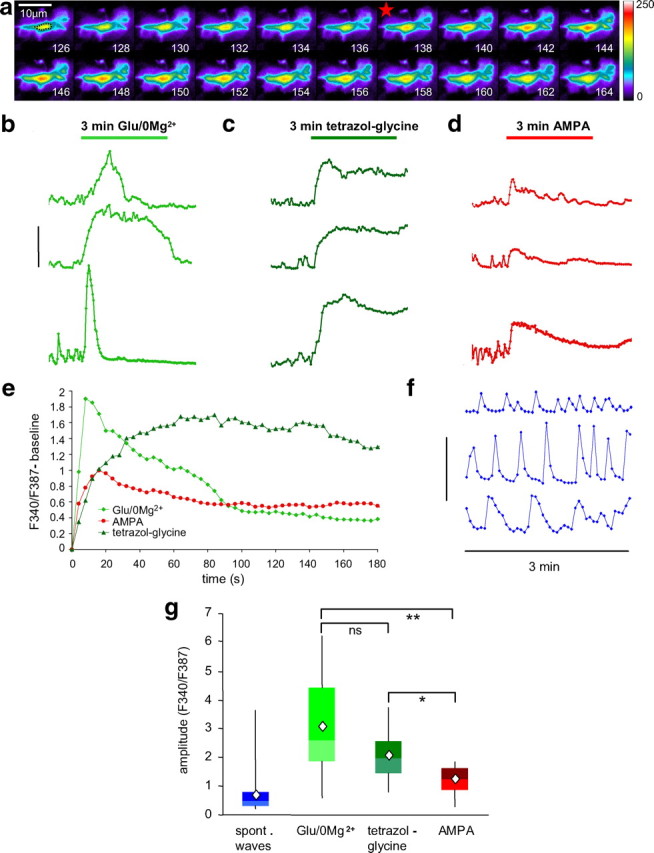

A likely candidate to mediate the glutamate receptor-dependent switch in growth activity is calcium signaling. We used the cell-permeable fluorescent calcium indicator fura-2 to evaluate the calcium signals in dopaminergic axonal growth cones in response to glutamate receptor activation. Fura-2 fluorescence was measured at a rate of 0.25–0.5 Hz in GFP-positive growth cones for 1–2 min before superfusion with stimulus medium, during (3 min), and after (2 min) the stimulus.

A time series of fura-2 fluorescence images (excitation at 340 nm) of a growth cone at the onset of the response to glutamate/0 Mg2+ is shown in Figure 3a. Glutamate/0 Mg2+ elicited calcium signals of high amplitude that were often of shorter duration than the 3 min stimulation (Fig. 3b, examples; e, averaged traces; g, distribution of peak amplitudes). The NMDA agonist, tetrazol-glycine, elicited long-lasting calcium signals of intermediate amplitude (Fig. 3c,e,g), whereas AMPA evoked calcium signals of small amplitude that declined slowly (Fig. 3d,e,g). Spontaneous calcium transients were observed in 66% of the growth cones before the stimulation at an average frequency of two per minute (Fig. 3f, examples). The distribution of their amplitudes is plotted for comparison in Figure 3g. Calcium signals in response to glutamate/0 Mg2+ (n = 30 growth cones, 17 cultures) were not statistically significantly larger than tetrazol-glycine-evoked signals (n = 19 growth cones, 8 cultures), but were larger than AMPA-evoked signals (n = 21 growth cones, 11 cultures; Dunn's test, p < 0.001), and tetrazol-glycine-evoked signals were statistically significantly larger than AMPA-evoked signals (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Calcium imaging in dopaminergic growth cones. a, Time series (in seconds) of fura-2 fluorescence in a dopaminergic axonal growth cone at excitation wavelength of 340 nm, with fluorescence intensity coded in pseudocolor. The dotted line in the first frame indicates the central area of the growth cone for which measurements were taken. The red star indicates the beginning of the calcium signal that was elicited by superfusion with glutamate/0 Mg2+. b–d, Examples of growth cone calcium signals in response to a 3 min stimulus of glutamate/0 Mg2+ (b), tetrazol-glycine (c), or AMPA (d). Calibration: F340/F387 = 4. e, Averaged calcium traces for the three different stimuli (normalized to the baseline before the stimulus-induced calcium rise). No SEs are plotted for better clarity [also, data were not normally distributed (see g)]. Glutamate/0 Mg2+ (light green diamonds; n = 30, 17 cultures) evoked signals of high amplitude that declined relatively fast, tetrazol-glycine (dark green triangles; n = 19, 8 cultures) evoked signals of medium amplitude with slower onset and no decline, and AMPA (red circles; n = 21, 11 cultures) evoked the smallest amplitude signals that declined slowly. f, Examples of spontaneous calcium transients are shown, which occurred before the stimulus in 66% of the recorded growth cones (sampling frequency was 0.25 Hz; calibration: F340/F387 = 2). g, The distribution (in quartiles; diamond symbol, average) of calcium signal peak amplitudes is plotted for glutamate/0 Mg2+ (n = 30), tetrazol-glycine (n = 19), AMPA (n = 21), and, for comparison, spontaneous calcium transients (n = 191). Nonparametric ANOVA with Dunn's post hoc test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

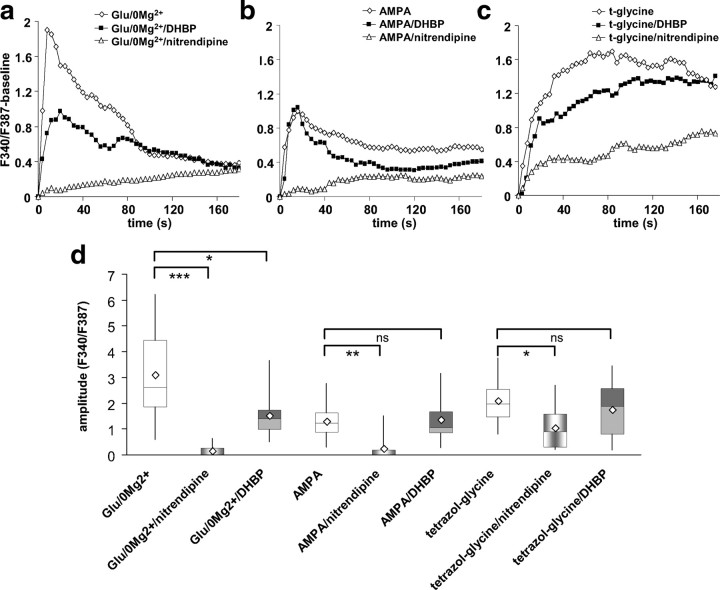

We next addressed possible sources for the calcium signals of different magnitudes: calcium influx through voltage-gated calcium channels, through NMDA receptors, and calcium release from intracellular calcium stores. As dopaminergic neurons express L-type calcium channels, we tested the antagonist nitrendipine. Superfusion with nitrendipine (15 min) abolished the occurrence of spontaneous calcium transients (0% compared with 66% incidence in controls). Subsequent stimulation with glutamate/0 Mg2+ in the presence of nitrendipine elicited no detectable calcium signal (Fig. 4a,d) (n = 16 growth cones, 6 cultures), indicating that glutamate/0 Mg2+-induced calcium influx was mediated exclusively by L-type calcium channels. We tested next whether calcium-induced calcium release from intracellular stores (CICR) contributed to the calcium signals by preincubating cultures with DHBP (100 μm), an antagonist of the ryanodine receptor that mediates CICR. Preincubation with DHBP for 15 min did not abolish spontaneous calcium waves in all cells, but reduced their incidence (32% of growth cones exhibited spontaneous waves compared with 66% in control medium). The calcium signal in response to glutamate/0 Mg2+ was reduced by approximately one-half in the presence of DHBP (Fig. 4a,d) (n = 14 growth cones, 8 cultures). Thus, calcium signals measured in dopaminergic axonal growth cones in response to glutamate/0 Mg2+ involved activation of voltage-gated L-type calcium channels and CICR from intracellular stores.

Figure 4.

Effects of L-type calcium channel blocker nitrendipine and ryanodine receptor inhibitor DHBP on glutamate receptor agonist-evoked growth cone calcium signals. a, Averaged traces of glutamate/0 Mg2+-evoked calcium signals (white diamonds; n = 30, 7 cultures) compared with calcium signals evoked by glutamate/0 Mg2+ in the presence of either nitrendipine (10 μm; white triangles; n = 16, 6 cultures) or DHBP (100 μm; dark squares; n = 14, 8 cultures). b, Averaged traces of AMPA-evoked calcium signals (white diamonds; n = 21, 11 cultures) compared with calcium signals evoked by AMPA in the presence of either nitrendipine (white triangles; n = 21, 5 cultures) or DHBP (black squares; n = 13, 5 cultures). c, Averaged traces of tetrazol-glycine-evoked calcium signals (white diamonds; n = 19, 8 cultures) compared with calcium signals evoked by tetrazol-glycine in the presence of either nitrendipine (white triangles; n = 10, 7 cultures) or DHBP (black squares; n = 12, 4 cultures). d, Distribution of calcium signal peak amplitudes for all the conditions in a–c. Nonparametric ANOVA with Dunn's post hoc test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

AMPA-induced calcium signals were solely attributable to calcium influx through L-type calcium channels, as they were completely blocked by nitrendipine (n = 14 growth cones, 5 cultures) and DHBP had no effect (Fig. 4b,d) (n = 14 growth cones, 5 cultures). The amplitude of calcium signals evoked by the NMDA agonist tetrazol-glycine was reduced by ∼50% in the presence of nitrendipine (n = 10 growth cones, 7 cultures). Calcium signals in DHBP-pretreated cultures tended to be reduced, but the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 4c,d) (n = 12 growth cones, 4 cultures). The data suggest that NMDA receptor activity alone can activate voltage-gated L-type calcium channels, but that in the case of tetrazol-glycine stimulation another source of calcium, likely influx through NMDA receptors, contributed to the recorded signal.

In summary, our data demonstrate that stimuli that activate AMPA/kainate and NMDA receptors evoke in dopamine axon growth cones calcium signals of high amplitude caused by calcium influx through L-type calcium channels and CICR, and accelerate axonal growth. In contrast, activation of AMPA/kainate receptors alone evokes lower amplitude calcium signals solely attributable to calcium influx through L-type calcium channels that lead to decreased axonal growth.

Calcium-dependent pathways involved in glutamate-evoked axonal growth changes

The glutamate receptor-dependent switch from axon growth acceleration to inhibition is reminiscent of the calcium-dependent switch from attraction to repulsion reported in the Xenopus growth cone turning assay (Wen et al., 2004). In that study, a local increase in calcium levels relative to varying basal levels activated either a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)-dependent pathway that led to attraction, or a calcineurin [serine/threonine PP2B (protein phosphatase 2B)]-dependent pathway that led to repulsion. We therefore tested whether these signaling pathways were involved in the NMDA receptor-dependent axonal growth acceleration and AMPA/kainate receptor-dependent growth inhibition in dopaminergic neurons.

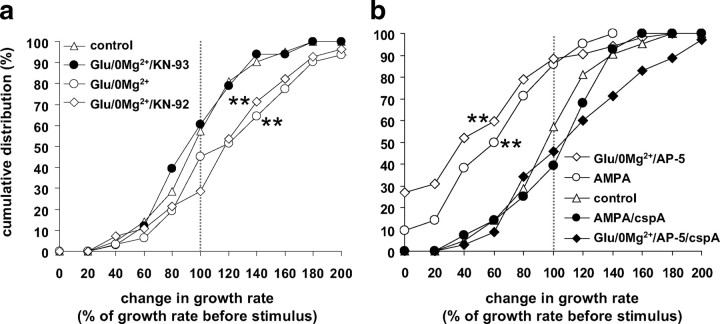

Preincubation with the CaMKI/II/IV inhibitor KN93 (5 min) blocked the glutamate/0 Mg2+-induced growth acceleration (Fig. 5a) (n = 33 axons, 9 cultures; p = 0.01) and completely prevented growth cone splitting. With the inactive analog KN92, growth acceleration by glutamate/0 Mg2+was unaffected (n = 28 axons, 9 cultures; p = 0.9) and growth cone splitting occurred with an incidence of 11% (p < 0.001, compared with control). Thus, the acceleration of axonal growth in response to glutamate/0 Mg2+ appeared to be mediated by a signaling pathway involving CaMKs. Importantly, axonal growth rates in the presence of KN93 followed the control distribution, indicating that the calcium influx induced by glutamate/0 Mg2+ did not activate pathways that lead to growth inhibition when CaMK-dependent pathways were blocked.

Figure 5.

Glutamate/0 Mg2+-induced growth acceleration was blocked by KN93, and AMPA-induced growth inhibition by cspA. a, Cumulative frequency distribution of growth rate change after a Glu/0 Mg2+ stimulus (n = 31, 12 dishes; white circles), Glu/0 Mg2+ in the presence of the CaMKI/II/IV inhibitor KN93 (5 μm; n = 33, 9 dishes; dark circles), and its inactive analog, KN-92 (5 μm; n = 28, 9 dishes; white diamonds), control data (no stimulus) are plotted for comparison (white triangles). b, Cumulative frequency distribution of growth rate change after AMPA (n = 42, 9 dishes; white circles) and Glu/0 Mg2+/AP-5 (n = 52, 12 dishes; white diamonds) compared with stimulation with AMPA (n = 28, 8 dishes; black circles) or Glu/0 Mg2+/AP-5 in the presence of the calcineurin inhibitor cspA (10 nm, n = 35, 7 dishes; black diamonds) and with control (no stimulus; n = 23, 6 dishes; white triangles). **Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, different from control, p < 0.01.

When cultures were superfused with the calcineurin inhibitor cspA for 20 min before and during an AMPA (n = 28 axons, 8 cultures) or glutamate/0 Mg2+/AP-5 stimulus (n = 35, 7 cultures), axons continued to grow (Fig. 5b) (p > 0.6), indicating that AMPA-induced growth inhibition is mediated by a calcineurin-dependent signaling pathway.

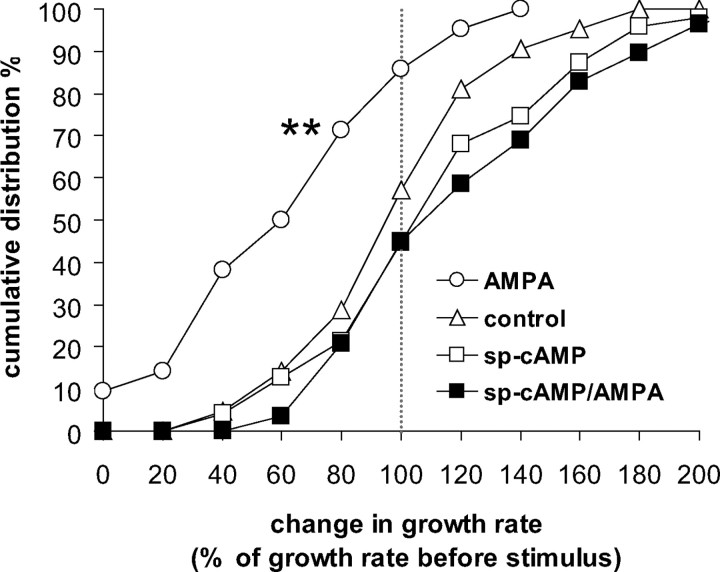

cAMP prevented AMPA-induced axon growth inhibition

The axonal response to many growth and guidance cues, for example, the guidance molecule netrin, can result in either stimulation or inhibition of growth depending on intracellular cyclic nucleotide levels. Furthermore cAMP may directly affect calcium signals and/or interfere with calcium-dependent pathways (Ming et al., 1997; Nishiyama et al., 2003; Ooashi et al., 2005). We tested whether intracellular cAMP levels per se affected axonal growth in dopaminergic neurons and whether cAMP levels affected the response to AMPA (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Increased intracellular cAMP levels prevented the AMPA-induced axon growth inhibition. Cumulative frequency distribution of growth rate change after AMPA (white circles), sp-cAMP (250 μm for 23 min; n = 47, 8 dishes; white squares), and AMPA plus sp-cAMP (black squares; n = 29, 7 dishes), compared with control (n = 23, 6 dishes; white triangles). **Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, different from control, p < 0.01.

Superfusion with the active cAMP analog sp-cAMP alone (n = 47 axons, 8 cultures; p = 0.51) shifted the growth rate distribution slightly, but not significantly differently from controls, whereas preincubation with sp-cAMP completely prevented growth inhibition in response to AMPA (n = 47 axons, 8 cultures; control vs AMPA/sp-cAMP, p = 0.14; AMPA vs AMPA/sp-cAMP, p < 0.01).

Discussion

Glutamate and axonal growth

This investigation asked whether axonal arborization of dopaminergic neurons is regulated by glutamatergic input. Our data demonstrate that dopaminergic neurons respond to a combined AMPA/kainate and NMDA receptor activation with acceleration of axonal growth, and to AMPA/kainate receptor activation alone with growth inhibition. Such a glutamate-evoked effect on axonal growth rates and receptor-dependent switch between axonal growth acceleration and inhibition has not been previously reported. Moreover, we observed that the combined activation of AMPA/kainate and NMDA receptors induced the splitting of axonal growth cones into several branches.

Previous studies reported mostly inhibitory effects of a global glutamate stimulus on axon growth (Mattson et al., 1988; Brewer and Cotman, 1989; McKinney et al., 1999; Yamada et al., 2008), whereas a gradient of glutamate evoked a positive growth cone turning response dependent on NMDA receptor activation (Zheng et al., 1996). AMPA and kainate glutamate receptors have been shown to be involved in regulating growth cone filopodia motility in a dose-dependent manner (Chang and De Camilli, 2001; Tashiro et al., 2003). We found that NMDA receptor activation was required to induce axon growth acceleration in dopaminergic neurons, whereas the agonist AMPA evoked axon growth inhibition. As AMPA activates both AMPA and kainate receptors (Paternain et al., 1995) and NMDA receptor antagonists switched the glutamate/0 Mg2+-evoked response from acceleration to inhibition, we can assume that the combined activation of AMPA and kainate receptors induced growth inhibition. We did not find an effect of metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) agonists on axonal growth in dopaminergic neurons. In contrast, a study that used organotypic brain slice cocultures of cortex, striatum, and substantia nigra, reported that group I mGluR blockade prevented the dopaminergic innervation of the striatal slice (Plenz and Kitai, 1998). It could be that the relatively short time period in which we monitored axonal growth rates (1 h) was too short to detect effects of mGluR activation, which were observed over a period of 5–18 d in the slice cultures. Also, the target of the mGluR effect in the triple slice culture system is unknown, and the effect might be mediated by another cell type. Similarly, in our culture system indirect effects mediated by other cell types, especially astrocytes (Allen and Barres, 2005), which are required to successfully culture postnatal dopamine neurons, cannot be excluded.

An important question is when and how neurotransmission plays a role in shaping the axonal arborization of a cell. The general notion is that cues like axonal guidance molecules lead the axon to its target region and neurotransmission affects the specificity of the innervation pattern in the target. It has been recently suggested that, in glutamatergic neurons, glutamate released by the advancing growth cone itself may provide a feedback signal determining whether to grow or to halt based on developmental age and the glutamate concentration achieved (Chang and De Camilli, 2001; Tashiro et al., 2003; Ibarretxe et al., 2007). It is possible that such a mechanism also applies to dopamine neurons as they are known to be able to store and release glutamate in culture (Sulzer et al., 1998), during some developmental period in vivo (Mendez et al., 2008), and during recovery from toxin-induced lesions (Dal Bo et al., 2008). It is also possible that glutamate input at the cell body or dendrites regulates dopamine axon growth, as reported for cortical neurons in which AMPA receptor activation at the cell body induced calcium waves traveling down the axon, leading to growth cone collapse (Yamada et al., 2008). Our immunohistochemistry data similarly suggest that the AMPA effect we report may originate at somatodendritic receptors, as immunolabel for AMPA receptors was detectable in cell bodies and dendrites but not in axonal growth cones. In contrast, immunolabel for NMDA receptors was located in both cell bodies and growth cones. Thus, a third possibility is that locally spillover of glutamate released from nearby corticostriatal or thalamostriatal terminals (Zhang and Sulzer, 2003; Hires et al., 2008) could directly affect dopaminergic axons, providing a mechanism to encourage dopaminergic axonal growth in the vicinity of active corticostriatal and thalamostriatal terminals, with which they are in close contact in the adult brain (Bouyer et al., 1984; Moss and Bolam, 2008).

Calcium and axonal growth

The cellular response to neurotransmitters involves changes in intracellular calcium that has long been known to affect neurite growth (Gomez and Zheng, 2006). The “set point hypothesis” proposed that there is a narrow optimal range of calcium concentrations for neurite growth and if levels fall above or below that range growth is inhibited (Kater and Mills, 1991). This was confirmed by studies on Xenopus spinal neurons demonstrating that local calcium signals of small or large amplitude evoked repulsion, whereas calcium signals of moderate size evoked attraction of the growth cone (Hong et al., 2000; Robles et al., 2003; Wen et al., 2004). We also found a switch in response to differently sized calcium signals, but in our case axons responded to relatively large calcium signals that involved calcium influx through L-type calcium channels and CICR with accelerated growth and in some cases with growth cone splitting. It is possible that there is a calcium threshold for growth cone splitting so that splitting occurs only for the highest amplitude calcium transients. Indeed, the effect of netrin-1 on axonal branch formation in cortical neurons correlated with an increased frequency of calcium transients (Tang and Kalil, 2005).

We found that the glutamate-evoked calcium signals in dopaminergic axonal growth cones were completely blocked by inhibitors of L-type calcium channels. We cannot exclude, however, that other channels, for example voltage-gated T-type calcium channels, were also involved, as they may be affected by the relative high dihydropyridine concentration that we used (Bean, 1989). Dopaminergic neurons prominently express L-type calcium channels that are known to mediate oscillatory calcium waves in cell bodies and dendrites (Nedergaard et al., 1993; Mercuri et al., 1994; Puopolo et al., 2007) but are not involved in mediating evoked dopamine release from axon terminals in striatal slices (Phillips and Stamford, 2000). Our finding that calcium-influx through L-type calcium channels affects axonal growth is congruent with studies on cultured cortical neurons (Tang et al., 2003) and Xenopus spinal neurons (Nishiyama et al., 2003), which reported that L-type calcium channels mediated calcium influx into the growth cone.

Downstream from the AMPA/NMDA and AMPA-evoked calcium signals, we found that growth acceleration was mediated by CaMKI/II/IV-dependent and growth inhibition by calcineurin-dependent pathways, respectively. (We cannot discern between CaMKI, II, and IV, as KN93, the used inhibitor, is nonspecific.) CaMKI/II/IV inhibitors were reported to affect the growth cone attraction response in Xenopus spinal neurons evoked by local high calcium signals (Wen et al., 2004), and netrin-1-evoked branching in cortical neurons (Tang and Kalil, 2005), which, similar to our findings, was dependent on calcium release from intracellular stores. Studies overexpressing specific CaMKs found evidence for a role of either CaMKI (Wayman et al., 2004) or αCaMKII (Tang and Kalil, 2005) in axonal extension and branching.

Similar to growth cone repulsion in Xenopus neurons (Wen et al., 2004), we found that AMPA-induced growth inhibition was blocked by inhibitors of the phosphatase calcineurin and was prevented by increased cAMP levels. Calcineurin was apparently not activated by the high calcium signals evoked by combined AMPA/NMDA receptor activation, as axonal growth was not inhibited while CaMKs were blocked. This is in accordance with findings on CaMKII/calcineurin-dependent long-term potentiation/long-term depression (LTD) induction, in which only modest calcium signals activate calcineurin and induce LTD (Hansel et al., 1996; Yang et al., 1999; Yasuda et al., 2003). The cAMP effect could be mediated by a cross talk between calcium- and cAMP-dependent pathways (Wen et al., 2004), or by a direct effect of cAMP on calcium channels (Nishiyama et al., 2003). Levels of cAMP are regulated by D2 autoreceptors in dopamine neurons (Picetti et al., 1997), so that dopamine release by the growth cone might feedback via D2 dopamine autoreceptors to modulate the response to glutamate input.

Factors that encourage directed dopaminergic sprouting might offset the loss of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson's disease or contribute to treatments intended to replace dopamine neurons, such as transplantation of stem cell-derived neurons. Several factors that promote dopaminergic sprouting and regeneration have been identified: neurotrophic factors (Date et al., 1993; Lin et al., 1993; Frim et al., 1994), and molecules of their signaling pathways (Ries et al., 2006), guidance molecules (Yue et al., 1999; Lin and Isacson, 2006; Cooper et al., 2009), and immunosuppressant drugs (Costantini et al., 2001). One of the challenges of such an approach is to not only induce but also direct neurite growth toward the appropriate target, and the effects of NMDA receptor activation reported here may provide such functional regeneration of the nigrostriatal projection.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the National Parkinson's Foundation (Y.S.). J.L. received a summer fellowship from Parkinson's Disease Foundation (PDF), and D.S. is supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, PDF, The Picower Foundation, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. We thank Ellen Kanter for excellent cell culturing. Dr. Kazuto Kobayashi generously provided TH-GFP mice. Drs. Daniela Pereira and Eugene Mosharov contributed valuable discussion and comments on this manuscript.

References

- Allen NJ, Barres BA. Signaling between glia and neurons: focus on synaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP. Multiple types of calcium channels in heart muscle and neurons. Modulation by drugs and neurotransmitters. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;560:334–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb24113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer JJ, Park DH, Joh TH, Pickel VM. Chemical and structural analysis of the relation between cortical inputs and tyrosine hydroxylase-containing terminals in rat neostriatum. Brain Res. 1984;302:267–275. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Cotman CW. NMDA receptor regulation of neuronal morphology in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 1989;99:268–273. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, De Camilli P. Glutamate regulates actin-based motility in axonal filopodia. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:787–793. doi: 10.1038/90489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MA, Kobayashi K, Zhou R. Ephrin-A5 regulates the formation of the ascending midbrain dopaminergic pathways. Dev Neurobiol. 2009;69:36–46. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini LC, Cole D, Chaturvedi P, Isacson O. Immunophilin ligands can prevent progressive dopaminergic degeneration in animal models of Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1085–1092. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Bo G, Bérubé-Carrière N, Mendez JA, Leo D, Riad M, Descarries L, Lévesque D, Trudeau LE. Enhanced glutamatergic phenotype of mesencephalic dopamine neurons after neonatal 6-hydroxydopamine lesion. Neuroscience. 2008;156:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date I, Yoshimoto Y, Imaoka T, Miyoshi Y, Gohda Y, Furuta T, Asari S, Ohmoto T. Enhanced recovery of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system in MPTP-treated mice following intrastriatal injection of basic fibroblast growth factor in relation to aging. Brain Res. 1993;621:150–154. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90312-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paola V, Arber S, Caroni P. AMPA receptors regulate dynamic equilibrium of presynaptic terminals in mature hippocampal networks. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:491–500. doi: 10.1038/nn1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frim DM, Uhler TA, Galpern WR, Beal MF, Breakefield XO, Isacson O. Implanted fibroblasts genetically engineered to produce brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevent 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium toxicity to dopaminergic neurons in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:5104–5108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier J, Parent M, Lévesque M, Parent A. The axonal arborization of single nigrostriatal neurons in rats. Brain Res. 1999;834:228–232. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01573-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogolla N, Galimberti I, Caroni P. Structural plasticity of axon terminals in the adult. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez TM, Zheng JQ. The molecular basis for calcium-dependent axon pathfinding. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:115–125. doi: 10.1038/nrn1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracy KN, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural immunocytochemical localization of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor and tyrosine hydroxylase in the shell of the rat nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 1996;739:169–181. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00822-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel C, Artola A, Singer W. Different threshold levels of postsynaptic [Ca2+]i have to be reached to induce LTP and LTD in neocortical pyramidal cells. J Physiol Paris. 1996;90:317–319. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(97)87906-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hires SA, Zhu Y, Tsien RY. Optical measurement of synaptic glutamate spillover and reuptake by linker optimized glutamate-sensitive fluorescent reporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4411–4416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712008105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K, Nishiyama M, Henley J, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo M. Calcium signalling in the guidance of nerve growth by netrin-1. Nature. 2000;403:93–98. doi: 10.1038/47507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibarretxe G, Perrais D, Jaskolski F, Vimeney A, Mulle C. Fast regulation of axonal growth cone motility by electrical activity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7684–7695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1070-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kater SB, Mills LR. Regulation of growth cone behavior by calcium. J Neurosci. 1991;11:891–899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-04-00891.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Isacson O. Axonal growth regulation of fetal and embryonic stem cell-derived dopaminergic neurons by Netrin-1 and Slits. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2504–2513. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LF, Doherty DH, Lile JD, Bektesh S, Collins F. GDNF: a glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor for midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Science. 1993;260:1130–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.8493557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda W, Furuta T, Nakamura KC, Hioki H, Fujiyama F, Arai R, Kaneko T. Single nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons form widely spread and highly dense axonal arborizations in the neostriatum. J Neurosci. 2009;29:444–453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4029-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Dou P, Kater SB. Outgrowth-regulating actions of glutamate in isolated hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2087–2100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-06-02087.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney RA, Lüthi A, Bandtlow CE, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Selective glutamate receptor antagonists can induce or prevent axonal sprouting in rat hippocampal slice cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11631–11636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena MA, Khan U, Togasaki DM, Sulzer D, Epstein CJ, Przedborski S. Effects of wild-type and mutated copper/zinc superoxide dismutase on neuronal survival and l-DOPA-induced toxicity in postnatal midbrain culture. J Neurochem. 1997;69:21–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez JA, Bourque MJ, Dal Bo G, Bourdeau ML, Danik M, Williams S, Lacaille JC, Trudeau LE. Developmental and target-dependent regulation of vesicular glutamate transporter expression by dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6309–6318. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1331-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercuri NB, Bonci A, Calabresi P, Stratta F, Stefani A, Bernardi G. Effects of dihydropyridine calcium antagonists on rat midbrain dopaminergic neurones. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:831–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming GL, Song HJ, Berninger B, Holt CE, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo MM. cAMP-dependent growth cone guidance by netrin-1. Neuron. 1997;19:1225–1235. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss J, Bolam JP. A dopaminergic axon lattice in the striatum and its relationship with cortical and thalamic terminals. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11221–11230. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2780-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Nikonenko I. Dynamic presynaptic varicosities: a role in activity-dependent synaptogenesis. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:573–575. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard S, Flatman JA, Engberg I. Nifedipine- and omega-conotoxin-sensitive Ca2+ conductances in guinea-pig substantia nigra pars compacta neurones. J Physiol. 1993;466:727–747. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama M, Hoshino A, Tsai L, Henley JR, Goshima Y, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo MM, Hong K. Cyclic AMP/GMP-dependent modulation of Ca2+ channels sets the polarity of nerve growth-cone turning. Nature. 2003;423:990–995. doi: 10.1038/nature01751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooashi N, Futatsugi A, Yoshihara F, Mikoshiba K, Kamiguchi H. Cell adhesion molecules regulate Ca2+-mediated steering of growth cones via cyclic AMP and ryanodine receptor type 3. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:1159–1167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paternain AV, Morales M, Lerma J. Selective antagonism of AMPA receptors unmasks kainate receptor-mediated responses in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips PE, Stamford JA. Differential recruitment of N-, P- and Q-type voltage-operated calcium channels in striatal dopamine release evoked by “regular” and “burst” firing. Brain Res. 2000;884:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02958-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picetti R, Saiardi A, Abdel Samad T, Bozzi Y, Baik JH, Borrelli E. Dopamine D2 receptors in signal transduction and behavior. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1997;11:121–142. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v11.i2-3.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plenz D, Kitai ST. Regulation of the nigrostriatal pathway by metabotropic glutamate receptors during development. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4133–4144. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-11-04133.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puopolo M, Raviola E, Bean BP. Roles of subthreshold calcium current and sodium current in spontaneous firing of mouse midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:645–656. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4341-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries V, Henchcliffe C, Kareva T, Rzhetskaya M, Bland R, During MJ, Kholodilov N, Burke RE. Oncoprotein Akt/PKB induces trophic effects in murine models of Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18757–18762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606401103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles E, Huttenlocher A, Gomez TM. Filopodial calcium transients regulate growth cone motility and guidance through local activation of calpain. Neuron. 2003;38:597–609. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamoto K, Nakao N, Kobayashi K, Matsushita N, Takahashi H, Kakishita K, Yamamoto A, Yoshizaki T, Terashima T, Murakami F, Itakura T, Okano H. Visualization, direct isolation, and transplantation of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6423–6428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111152398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepp DD, Smith CL, Lodge D, Millar JD, Leander JD, Sacaan AI, Lunn WH. d,l-(tetrazol-5-yl) glycine: a novel and highly potent NMDA receptor agonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;203:237–243. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y, Bennett BD, Bolam JP, Parent A, Sadikot AF. Synaptic relationships between dopaminergic afferents and cortical or thalamic input in the sensorimotor territory of the striatum in monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1994;344:1–19. doi: 10.1002/cne.903440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Joyce MP, Lin L, Geldwert D, Haber SN, Hattori T, Rayport S. Dopamine neurons make glutamatergic synapses in vitro. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4588–4602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04588.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallaksen-Greene SJ, Wiley RG, Albin RL. Localization of striatal excitatory amino acid binding site subtypes to striatonigral projection neurons. Brain Res. 1992;594:165–170. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91044-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang F, Kalil K. Netrin-1 induces axon branching in developing cortical neurons by frequency-dependent calcium signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6702–6715. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0871-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang F, Dent EW, Kalil K. Spontaneous calcium transients in developing cortical neurons regulate axon outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2003;23:927–936. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00927.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro A, Dunaevsky A, Blazeski R, Mason CA, Yuste R. Bidirectional regulation of hippocampal mossy fiber filopodial motility by kainate receptors: a two-step model of synaptogenesis. Neuron. 2003;38:773–784. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman GA, Kaech S, Grant WF, Davare M, Impey S, Tokumitsu H, Nozaki N, Banker G, Soderling TR. Regulation of axonal extension and growth cone motility by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3786–3794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3294-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, Guirland C, Ming GL, Zheng JQ. A CaMKII/calcineurin switch controls the direction of Ca2+-dependent growth cone guidance. Neuron. 2004;43:835–846. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada RX, Sasaki T, Ichikawa J, Koyama R, Matsuki N, Ikegaya Y. Long-range axonal calcium sweep induces axon retraction. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4613–4618. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0019-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SN, Tang YG, Zucker RS. Selective induction of LTP and LTD by postsynaptic [Ca2+]i elevation. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:781–787. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda H, Higashi H, Kudo Y, Inoue T, Hata Y, Mikoshiba K, Tsumoto T. Imaging of calcineurin activated by long-term depression-inducing synaptic inputs in living neurons of rat visual cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:287–297. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y, Widmer DA, Halladay AK, Cerretti DP, Wagner GC, Dreyer JL, Zhou R. Specification of distinct dopaminergic neural pathways: roles of the Eph family receptor EphB1 and ligand ephrin-B2. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2090–2101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02090.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Sulzer D. Glutamate spillover in the striatum depresses dopaminergic transmission by activating group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10585–10592. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10585.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng JQ, Wan JJ, Poo MM. Essential role of filopodia in chemotropic turning of nerve growth cone induced by a glutamate gradient. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1140–1149. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01140.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]