Abstract

Cationic nanoparticles are a promising class of transfection agents for oligonucleotide and gene delivery, but vary greatly in their effectiveness and cytotoxicity. Recently, we developed a new class of cationic transfection agents based on cationic shell-crosslinked nanoparticles (cSCKs) that efficiently transfect mammalian cells with both oligonucleotides and plasmid DNA. In an effort to further improve transfection efficiency without increasing cytotoxicity, we examined the effects of the composition of primary amine (pa), tertiary amine (ta) and carboxylic acid (ca) groups in the shell of these nanoparticles. A series of discrete complexes of the cSCKs with plasmid DNA (pDNA) or phosphorothioate 2′-OMe oliogonucleotides (ps-MeON) were prepared over a broad range of amine to phosphate ratios (N/P ratio) of 4:1 to 40:1. The sizes of the complexes and the ability of the nanoparticles to completely bind ODNs were found to depend on the cSCK amine to DNA phosphate (N/P) ratio and the cSCK buffering capacity. The cSCKs were then evaluated for their ability to transfect cells with plasmid DNA by monitoring fluorescence from an encoded EGFP, and for delivery of ps-MeON by monitoring luminescence from luciferase resulting from ps-MeON-mediated splicing correction. Whereas the cationic cSCK-pa25-ta75 was found to be best for transfecting plasmid DNA into HeLa cells at an N/P ratio of 20:1, cSCK-pa50-ta50, at an N/P ratio 10:1 was best for ps-MeON delivery. We also found that increasing the proportion of tertiary relative to primary amine reduced the cytotoxicity. These results demonstrate that a dramatic improvement in gene and oligonucleotide delivery efficiency with decreased cytotoxicity in HeLa cells can be achieved by incorporation of tertiary amines into the shells of cSCKs.

Keywords: nanoparticle, gene transfer, cytotoxicity, endocytosis, proton sponge effect, antisense

Introduction

Gene therapy and antisense and antigene agents are widely believed to have tremendous potential for the treatment of many diseases currently considered incurable. One major stumbling block in the implementation of these therapeutic strategies is the lack of a suitable method for efficient intracellular delivery of the nucleic acid-based agents. Compared with viral vectors, synthetic materials, such as cationic liposomes, polymers and nanoparticles, are spared from many biosafety issues inherent to viral systems, and are amenable to large scale production and chemical modifications [1-5]. Though progress has been made in the development of such non-viral vectors [6-9], the better transfection materials usually exhibit higher toxicities, and show high variation in effectiveness depending on cell type. Therefore, materials for efficient and non-cytotoxic transfection of nucleic acid-based agents is one of the most urgent and important issues in the field of biomedicine.

Current methods for effecting delivery of nucleic acid therapeutics are often based on liposome-or polymersome-mediated membrane fusion [10-12] and ligand-mediated endocytosis [13-14]. Cationic liposomes have been widely used to transfect DNA in cell culture but its use in vivo is oftentimes compromised by its cytotoxicity and poor biodistribution. Addition of polyethylene glycol (PEG) moieties to the transfection agents generally improves their biocompatibility but often leads to significantly reduced transfection efficiency [15]. Surface-conjugated PEG has also been found to hinder the ability of the cationic functional groups to interact with cell surface receptors [16-17]. Intricate designs are required to retain effectiveness in transfection while improving biodistribution [18]. Cationic peptides, polymers, and nanoparticles have been used to enhance endocytosis of nucleic acids through macropinocytosis, and various ligands have been used for receptor-mediated endocytosis. In all cases, the transfection agents must form stable complexes with the nucleic acid therapeutic to protect it from enzymatic degradation and ensure delivery to the target site. The complexes also need to be of appropriate size, shape, flexibility and surface composition for optimal biodistribution and efficient intracellular delivery. For complexes entering cells by endocytosis, a mechanism for endosome rupture or leakage is required to release the complexed nucleic acid therapeutic into the cytosol, such as membrane disruption by endosome disrupting peptides, or the proton sponge effect, which is triggered during endosomal acidification [19]. Each of the steps, if problematic, can lead to poor performance of the transfection agent. It is, therefore, not surprising that the structure and properties of the transfection agent play important roles in the formation and cell uptake of the complexes, and timely release of the nucleic acid therapeutic [20-21].

We have recently shown that cationic shell-crosslinked knedel-like nanoparticles (cSCKs) can form electrostatic complexes with plasmid DNA and antisense phosphorothioate 2′-OMe oligonucleotides (ps-MeON) and efficiently transfect them into cells [22]. Similar to the cationic micellar structures [6, 23-25] studied by Kataoka et al, the cSCKs represent an example of an emerging class of nanoscale materials composed of amphiphilic block copolymers, each consisting of a hydrophobic section linked to a hydrophilic section [26-31]. The block copolymers are first assembled into micelles and then crosslinked through chemical conjugation between functional groups in the shell. Compared to the dynamic assemblies of micellar structures, the cSCKs are rigid, robust nanoparticles and resemble natural histones in size and DNA packaging ability [32]. The particular cSCK used for the transfection experiments consisted of a hydrophobic polystyrene (PS) polymer joined to a polyacrylamidoethylamine (PAEA) that were subsequently micellized and then crosslinked through amide bond formation. The cationic nature of the cSCK, resulting from the protonated primary amines of the PAEA in the shell, facilitates electrostatic binding to negatively charged nucleic acids. The cationic shell is capable of enhancing endocytosis through electrostatic interaction with the membrane surface and subsequent macropinocytosis. The presence of amines is also likely to promote subsequent endosomal release through the proton-sponge effect, due to their ability to neutralize protons (buffering capacity) in the pH 5.5-7.0 range during endosomal acidification.

cSCKs of PAEA-b-PS composition were found to transfect plasmid DNA into HeLa cells efficiently. These same particles were also shown to deliver peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) with very high efficiency, through electrostatic binding to a partially complementary DNA, or with even greater efficiency through conjugation via a bioreductively cleavable linker [33]. The different efficiencies observed for transfection of the electrostatically and covalently bound PNAs suggested that it might still be possible to improve the DNA/ODN binding and release properties of the cSCK by manipulating the structures of the functional groups in the shell. We, therefore, synthesized a series of cSCKs with different shell compositions, and found that their binding capacity, transfection efficiency, and cytotoxicity could be manipulated and improved by varying the relative amounts of primary amines (pa), tertiary amines (ta) and carboxylic acids (ca).

Materials and Methods

Materials

All solvents and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification, unless otherwise indicated. N-hydroxybenzotriazole·H2O (HOBt) and 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1, 1, 3, 3-tetramethylaminium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) were purchased from EMD Chemicals, Inc. The amphiphilic block copolymer, PAA128-b-PS40, was prepared using atom transfer radical polymerization of (protected) monomer precursors followed by deprotection, according to literature reported methods [34]. A luciferase splice-correcting phosphorothioate 2′-O-methyl-oligoribonucleotide (ps-MeON, CCUCUUACCUCAGUUACA) was synthesized on an Expedite 8909 DNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) using standard solid phase phosphoramidite chemistry and purified by 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gels, followed by extraction with phenol/chloroform and ethanol precipitation. HeLa cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The pLuc705 Hela cell line was a generous gift from Dr. R. Kole (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC). Oligofectamine and Lipofectamine™ 2000 were obtained from Invitrogen Co. Polyfect® was purchased from Qiagen Inc. pEGFP-N1 was obtained from Clontech Laboratories, Inc. Steady-Glo® Luciferase Assay reagent and CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay Kit were purchased from Promega Co. All cell culture media was purchased from Invitrogen, Inc.

Measurements

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 300 MHz spectrometer interfaced to a UNIX computer using Mercury software. Chemical shifts were referenced to the solvent resonance signals. IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum BX FT-IR system, and data were analyzed using Spectrum v2.0 software. Samples for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements were diluted with a 1 % phosphotungstic acid (PTA) stain (v/v, 1:1). Micrographs were collected at 50,000 and 100,000 × magnifications on a Hitachi-600. Hydrodynamic diameters (Dh) and size distributions were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS). The DLS instrumentation consisted of a Brookhaven Instruments Limited (Worcestershire, U.K.) system, including a model BI-200SM goniometer, a model BI-9000AT digital correlator, a model EMI-9865 photomultiplier, and a model 95-2 argon ion laser (Lexel Corp.) operated at 514.5 nm. Measurements were made at 25 ± 1 °C. Scattered light was collected at a fixed angle of 90°. A photomulitplier aperture of 100 μm was used, and the incident laser intensity was adjusted to obtain a photon counting of between, 200 and 300 kcps. Only measurements in which the measured and calculated baselines of the intensity autocorrelation function agreed to within 0.1 % were used to calculate particle size. The calculations of the particle size distributions and distribution averages were performed with the ISDA software package (Brookhaven Instruments Company). All determinations were repeated 5 times and the standard deviations reported were calculated as the error between DLS runs. Zeta potential (ζ) values for the nanoparticle solution samples were determined with a Brookhaven Instrument Co. (Holtsville, NY) model Zeta Plus zeta potential analyzer. Data were acquired in the phase analysis light scattering (PALS) mode following solution equilibration at 25 °C. Potentiometric titration of various cSCKs was performed using a Brinkmann Bottletop Buret 25 and a Corning pH meter 440. cSCK solutions containing 0.5 μmol polymers were diluted in 20 mL 38.94 mM HCl and titrated with 0.010 M NaOH.

Poly(acrylamidoethylamine(Boc)-co-acrylamidoethyldimethylamine)-block-polystyrene (PAEA(Boc)-co-PAEDMA-b-PS)

PAA128-b-PS40 (100 mg, 7.4 μmol, 0.94 mmol carboxylic acid groups) was dissolved in DMF (8.0 mL) and stirred for 3 h. Aliquots (2.0 mL) of the solution containing 25 mg polymer were transferred to 3 flasks. Then, 2.0 mL DMF solution containing HOBt (44 mg, 0.33 mmol) and HBTU (125 mg, 0.330 mmol) was added to each flask. After 30 min, 2.0 mL DMF solution containing various molar ratios of tert-butyl 2-aminoethylcarbamate and N-(2-aminoethyl) acrylamide (1:3, 2:2 and 3:1, 1.5 eq. to COOH total) and diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, 35 μL, 0.20 mmol) was slowly added to each flask at 4.0 mL/h using a syringe pump. The reaction mixtures were then sealed, allowed to stir overnight, diluted by the addition of DMF (5.0 mL), transferred to pre-soaked dialysis tubing (MWCO = 6 - 8 kDa), and were dialyzed against 150 mM NaCl solution for 2 days, then against nanopure water (18.0 MΩ·cm) for 5 days. After the dialysis period, the polymers were collected by lyophilization. Characterization data shown below are for PAEA(Boc)64-co-PAEDMA64-b-PS40. IR (cm-1): 3281, 3060, 2931, 2685, 1660, 1538, 1392, 1366, 1273, 1252, 1170, 1026, 1005, 824, 759. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 1.05-2.30 (br, Boc protons and polymer backbone protons), 2.85-3.65 (br, NHCH2CH2NH, NHCH2CH2N(CH3)2), 6.35-6.80 and 6.88-7.40 (br, ArH), 7.50-9.00 (br, CONH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2, ppm): δ 28.9 (br), 31.8-46.0 (multiple overlapping br), 56.6 (br), 78.4 (br), 126.4 (br), 127.9 (br), 128.7 (br), 145.3 (br), 156.8 (br), 175.3 (br).

Poly((acrylic acid)-co-acrylamidoethylamine(Boc))-block-polystyrene (PAA-co-PAEA(Boc)-b-PS) and poly((acrylic acid)-co-acrylamidoethyldimethylamine)-block-polystyrene (PAA-co-PAEDMA-b-PS)

Steps leading to the formation of activated polymers were the same as above. Afterwards, 1.0 mL DMF solutions of tert-butyl 2-aminoethylcarbamate (180, 96 and 64 equivalents to polymer) and N-(2-aminoethyl) acrylamide (180, 96, 64, and 32 equivalents to polymer) were added to the polymer solutions. Following 24 h reaction time, the polymers were purified using above procedures. PAA64-co-PAEA(Boc)64-b-PS40. IR (cm-1): 3316, 2931, 1704, 1660, 1531, 1392, 1366, 1252, 1170, 823, 760, 668. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 1.05-2.30 (br, Boc protons and polymer backbone protons), 2.80-3.20 (br, NHCH2CH2NH), 6.22-6.83 and 6.83-7.27 (br, ArH), 7.40-8.00 (br, CONH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 28.3 (br), 31.8-44.0 (multiple overlapping br), 79.7 (br), 126.2 (br), 127.3 (br), 128.4 (br), 145.9 (br), 155.9 (br), 174.0 (br), 176.4 (br). PAA64-co-PAEDMA64-b-PS40. IR (cm-1): 3283, 3027, 2927, 2715, 2359, 1727, 1678, 1553, 1382, 1199, 1138, 799, 703. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6 with 1% TFA-d, ppm): δ 0.80-2.49 (br, polymer backbone protons), 2.52-4.20 (br, NHCH2CH2N(CH3)2), 6.35-6.80 and 6.88-7.40 (br, ArH), 8.18-8.84 (br, CONH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 28.8 (br), 31.9-48.0 (multiple overlapping br), 56.4 (br), 126.4 (br), 128.0 (br), 145.9 (br), 175.7 (br).

Removal of Boc groups

Polymers containing Boc protecting groups (1.0 μmol) were dissolved in TFA (3 mL) and stirred for 6 h. The TFA was then removed in vacuo. 1H NMR and 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) confirmed the loss of Boc protons (1.42 ppm) and carbons (28.9 ppm, 79.7 ppm, 155.9 ppm), respectively. PAEA64-co-PAEDMA64-b-PS40. IR (cm-1): 3277, 3063, 2956, 2705, 1648, 1553, 1467, 1394, 1366, 1274, 1165, 1024, 748, 701, 660, 630. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 1.05-2.30 (polymer backbone protons), 2.85-3.65 (br, NHCH2CH2NH, NHCH2CH2NH+(CH3)2), 6.20-6.80 and 6.82-7.40 (br, ArH), 7.80-8.40 (br, CH2CH2NH3+, CONH), 9.70-10.20 (br, CH2CH2NH+(CH3)2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2, ppm): δ 31.8-46.0 (multiple overlapping br), 56.6 (br), 126.4 (br), 127.9 (br), 128.6 (br), 145.3 (br), 175.6 (br).

General procedure for the formation of primary-amine containing cSCK-pa-ta, and cSCK-pa-ca from PAEA-co-PAEDMA-b-PS and PAA-co-PAEA-b-PS, respectively

Each polymer (1.0 μmol) was dissolved in 7.0 mL dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and stirred for 2 h, before being transferred to a pre-soaked dialysis tube (8 kDa MWCO) and being allowed to dialyze against nanopure water (18.0 MΩ·cm) to remove organic solvent. After 4 days of dialysis, clear solutions containing the micelle precursors for the modified cSCKs were obtained. To crosslink each micelle sample, a diacid crosslinker (6.4 μmol, corresponding to 5% crosslinking) was activated by mixing with 2.2 equiv. of HOBt/HBTU (mole:mole) in DMF (400 μL) and allowing to stir for 1 h. This solution was then added slowly with stirring to the micelle solution, which had undergone adjustment of the pH to 8.0, using 1.0 M aqueous sodium carbonate, and reduction of the temperature to 0 °C, using an ice bath. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir overnight, and was then transferred to dialysis tubing (8 kDa MWCO) and dialyzed against nanopure water (18 MΩ·cm) for 3 days. All particles showed a mean hydrodynamic diameter (Dh) in the 14-18 nm range by DLS, and a mean dry-state diameter of 9 ± 3 nm, estimated from multiple (>3) TEM images.

General procedure for the formation of cSCK-ta-ca from PAA-co-PAEDMA-b-PS

PAA-co-PAEDMA-b-PS polymers (1.0 μmol) were assembled into micelles using the procedures above. To crosslink the micelles, O-bis-(aminoethyl)ethylene glycol (6.4 μmol, corresponding to 5% crosslinking) was added and the solution was allowed to stir at room temperature. After 30 min, an aqueous solution of 1-[3′-(dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI) (1.0 equiv., relative to the molar number of available COOH groups) was added. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir overnight before being transferred to presoaked and rinsed dialysis tubing (MWCO 3 kDa) and dialyzed against nanopure water (18.0 MΩ·cm) for 3 days.

Gel retardation assay

The oligodeoxynucleotide d(CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACA) was 5′-labeled by p32-γ-ATP with T4 Polynucleotide Kinase. Serial amounts of cSCKs were mixed with 0.5 μM radiolabeled ODN at N/P ratio of 0, 0.5:1, 1:1, 2:1, 4:1, 8:1, 16:1, 32:1, in PBS buffer for 30 min, which were then mixed with loading buffer (6 ×), and loaded to 15% native polyamide gel.

Cell culture

cSCKs mediated transfection was evaluated on HeLa cells (human cervical cancer cell line) by using the pEGFP-N1 as reporter gene or on pLuc705 Hela cells by luciferase expression. Cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and penicillin (100 units/mL) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. For pLuc705 HeLa cells, additional G418 (100 μg/mL) and hygromycin B (100 μg/mL) were also added.

Luciferase antisense splicing correction assay

pLuc705 HeLa cells were seeded in a 96-well microtiter plate at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and cultured for 24 h in 100 μL DMEM containing 10% FBS. ps-MeON (phosphorothioate 2′-O-methyl-oligoribonucleotide: CCUCUUACCUCAGUUACA) was complexed with cSCKs at predetermined N/P ratios in 20 μL opti-MEM solution and incubated for 30 min before use. At the time of the transfection experiment, the medium was replaced with 80 μL of fresh medium, to which the cSCK/ps-MeON complexes were added. Following 24 h incubation periods, 100 μL Steady-Glo® Luciferase assay reagent were added. The contents were mixed and the plate was shaken for 3 min at 600 rpm, and then allowed to incubate at room temperature for 10 min to stabilize the luminescence signal. Luminescence intensities were recorded on a Luminoskan Ascent® luminometer (Thermo Scientific) with an integration time of 1 second per well.

Fluorescence confocal microscopy

HeLa cells (5 × 105) were plated in 35 mm MatTek glass bottom microwell dishes (MatTek Co.) 24 h prior to transfection. pEGFP-N1 (5.0 μg) was complexed with cSCKs at predetermined N/P ratios in 500 μL opti-MEM solution and incubated for 30 min before use. Prior to transfection, the medium in each well was replaced with 2.0 mL of fresh DMEM, to which cSCK/pDNA complexes were added. 6h later, 10 % FBS was added. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for another 24. Each plate was washed 3 times with PBS buffer and viewed under bright field and fluorescent conditions using a Leica TCS SP2 inverted microscope, with excitation by an argon laser (488 nm).

Flow cytometry

The cell culture used for flow cytometry was the same as above. Prior to analysis, cells were washed 3 times with 2.0 mL PBS, collected by trypsinization, pelleted, and resuspended in 0.5 mL PBS. Flow cytometric analysis for the transfection using cSCKs was performed using an FACS-calibur (Becton Dickinson) equipped with an argon laser exciting at 488 nm. For each sample, 20,000 events were collected by list-mode data that consisted of side scatter, forward scatter, and fluorescence emission centered at 530 nm (FL1). The fluorescence was collected at a logarithmic scale with a 1024 channel-resolution. CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson) was applied for the analyses.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of the cSCKs was examined by CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega Co.). HeLa cells were each seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 2× 104 cells/well and cultured for 24 h in 100 μL DMEM containing 10% FBS. Thereafter, the medium was replaced with 100 μL of fresh medium containing various concentrations of cSCKs, Lipofectamine 2000, Polyfect (positive control), or no additive (negative control). After 24 h incubation at 37 °C, 100 μL CellTiter-Glo reagent was added. The contents were mixed and the plate was allowed to incubate at room temperature for 10 min to stabilize luminescence signals. Luminescence intensities were recorded on a Luminoskan Ascent® luminometer (Thermo Scientific) with an integration time of 1 second per well. The relative cell viability was calculated by the following equation:

Where luminescence(negative control) was obtained in the absence of particles and luminescence(sample) was obtained in the presence of cSCKs, Lipofectamine 2000, or Polyfect. The LC50 was determined by non-linear least squares fitting to a Hill Slope function % viability = % viabilitymax/(1+([NP]/LC50)ˆslope).

Results and Discussion

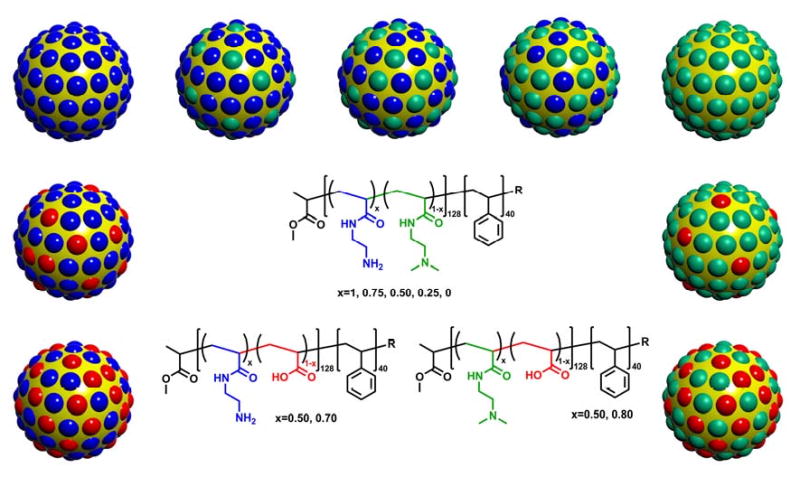

The cSCK that we had originally designed consisted of a shell bearing primary amines [22]. To determine the extent to which the structure and basicity of the amines, as well as the net charge and buffering capacity of the shell would affect nucleic acid binding and transfection, we prepared two general classes of modified cSCKs (Scheme 1). One class consisted of cSCKs with differing ratios of primary and tertiary amines, to maintain the same charge and the buffering capacity in the pH 5.5-7 range, but change the phosphate binding properties of the amines. The second class consisted of cSCKs with differing ratios of amines and carboxylic acids, to change the net charge of the cSCK as well as its buffering capacity. The required cSCKs were prepared by creating a library of modified precursor block copolymers, each of which was separately assembled into micelles and then chemically crosslinked. The particles were 9-11 nm in diameter, as observed by TEM, and 14-18 nm in hydrodynamic diameter, as measured by DLS. All particles were positively charged at pH 5.5 or pH 7.0, as determined by zeta potential measurements. The positively-charged nature of the cSCKs was utilized to form cSCK/DNA complexes through electrostatic interactions.

Scheme 1.

cSCKs with various shell compositions, including mixtures of primary/tertiary amines, mixtures of primary amines/carboxylic acids and mixtures of tertiary amines/carboxylic acids.

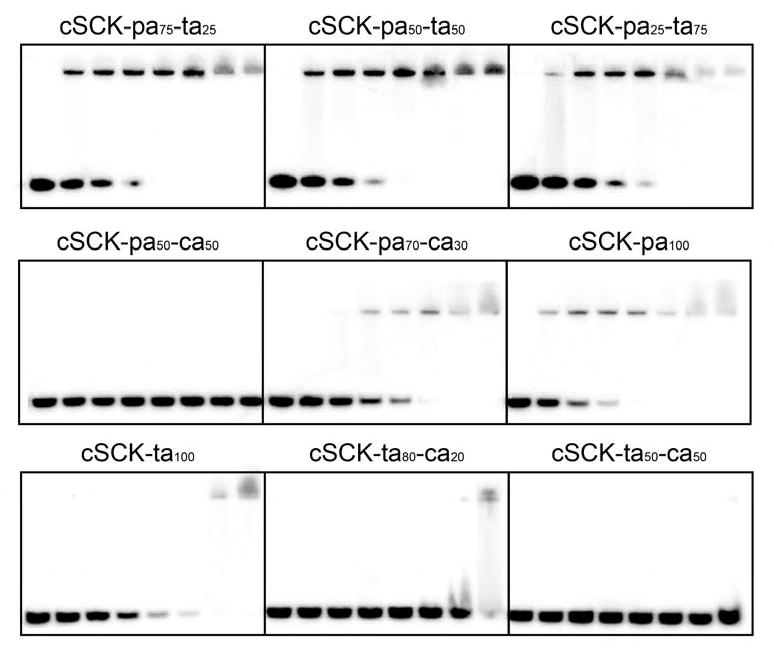

Binding affinity of the cSCKs for DNA

The binding affinity of the cSCKs for DNA was measured by a gel retardation assay with a 5′-32P-labeled oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) at increasing N/P (cSCK nitrogen to DNA phosphate) ratios (Figure 1). While complete binding of the ODN could be achieved at an N/P ratio of 4:1 with the primary amine modified cSCK-pa100 (100% primary amine), an N/P ratio of 16:1 was required for the tertiary amine-modified cSCK-ta100. The higher N/P ratio required for the tertiary amine-modified cSCK may result from steric hindrance to phosphate binding caused by the methyl groups. Increasing the fraction of tertiary amines from cSCK-pa100 to cSCK-ta100 caused an increase in the N/P ratio for complete binding. cSCKs containing carboxylic acids (cSCK-ca) required even higher N/P ratios for complete DNA binding. For example, cSCK-ta80-ca20 only showed a small degree of DNA binding at N/P of 32, while cSCK-pa50-ca50 showed no binding at all. This is perhaps due to intra-nanoparticle ammonium-carboxylate salt bridge interactions that reduced the availability of the ammonium ions for interacting with the DNA phosphates.

Figure 1.

Gel retardation essay of cSCKs/ODN complexes at different N/P ratios ranging from 0:1 to 32:1. Radioactively 5′-32P-labeled d(CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACA) (0.5 μM) was incubated with cSCK at N/P ratios of 0, 0.5:1, 1:1, 2:1, 4:1, 8:1, 16:1, 32:1 in PBS buffer for 30 min and then loaded to 15% native polyacrylamide gel. The band at the top is the ODN bound to the cSCK, and the band at the bottom is the free ODN. For N/P = 1:1, the concentrations of cSCK-pa100, cSCK-pa75-ta25, cSCK-pa50-ta50, cSCK-pa25-ta75, cSCK-ta100, cSCK-pa70-ca30, cSCK-pa50-ca50, cSCK-ta80-ca20 and cSCK-ta50-ca50 were 1.33, 1.54, 1.55, 1.52, 1.58, 2.77, 2.89, 1.82 and 2.53 μg/mL, respectively.

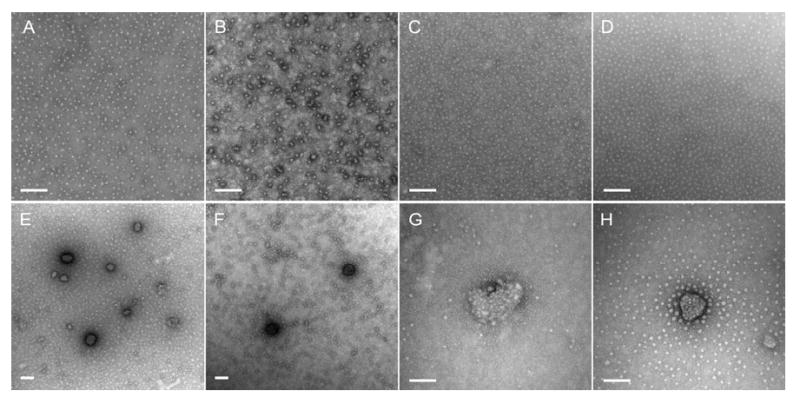

The binding of pDNA and ODN to various cSCKs was also visualized by TEM (Figure 2). Whereas cSCK-pa-ta, cSCK-ta and cSCK-pa all formed complexes with pDNA or ODN, the size of cSCK/ODN complexes were much smaller than were the cSCK/pDNA complexes. The larger size of the cSCK/pDNA complexes results from multiple cSCKs being required to bind to the large number of phosphates on the plasmid DNA. With an excess of cSCK (N/P>6), the complexes of cSCK/pDNA are generally 50-100 nm in diameter with irregular shapes, while the cSCK/ODN complexes are ca. 10 nm in diameter, appear circular in the two-dimensional TEM images, which suggests that the particles adopt a three-dimensional spherical morphology. Decreasing the N/P ratio below to 2 led to the formation of large aggregates (>800 nm) and further decrease resulted in macroscopic precipitation of the pDNA-cSCK complexes. These large aggregates have been shown to be inefficient for cell transfection, perhaps due to difficulty in endocytosing large structures [22].

Figure 2.

TEM images of cSCKs/ODN and cSCK/pDNA complexes at different N/P ratios. A) cSCK-pa100/ODN, N/P 6:1; B) cSCK-pa50-ta50/ODN, N/P 20:1; C) cSCK-ta100/ODN, N/P 20:1; D) cSCK-pa70-ca30/ODN, N/P 30:1; E) cSCK-pa100/pEGFP, N/P 6:1; F) cSCK-pa50-ta50 /pEGFP, N/P 20:1; G) cSCK-ta100/pEGFP, N/P 20:1; H) cSCK-pa70-ca30/pEGFP, N/P 30:1. The bar represents 100 nm.

Buffering capacity and charge of the cSCKs

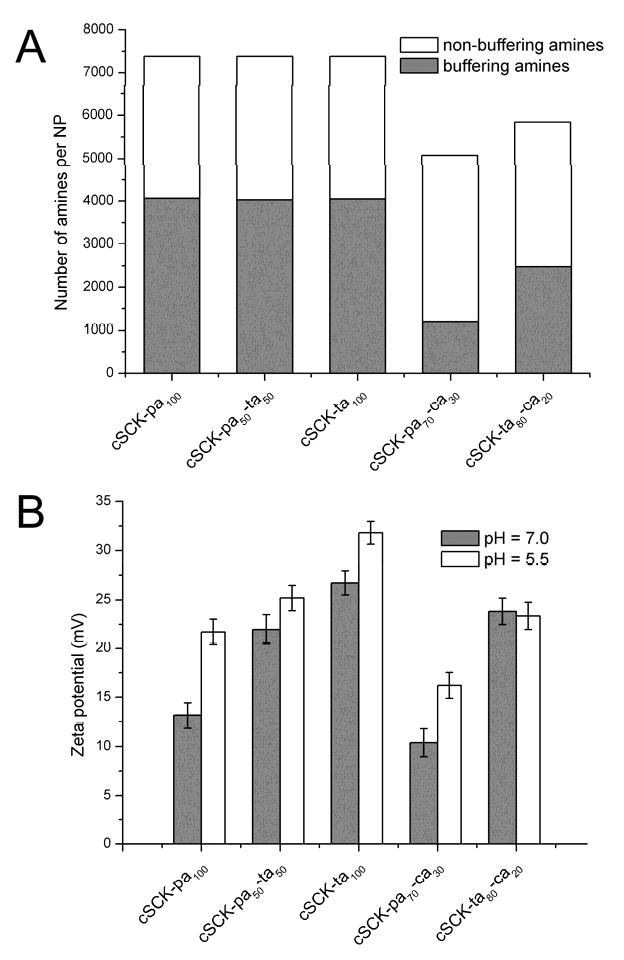

To determine the buffering capacity of the shells of each type of cSCK, potentiometric titration experiments were conducted. The particles were found to have buffering ability across a pH region of ca. 4-9, though only ability to absorb protons in the pH 5.5-7 range during endosomal acidification contributes to endosomal destabilization through the proton sponge effect. We calculated the total number of amines in the shell of each particle based on the particle size and composition, and the number of protons that each NP can absorb when pH is reduced from 7.0 to 5.5, using previously established methods (Figure 3A) [22, 35].1 The cSCKs with 100% amine modification (cSCK-pa100, cSCK-pa-ta and cSCK-ta100), showed almost equal buffering capacity over this pH range, taking up approx. 4000 protons per NP, while incorporation of carboxylic acids significantly decreased this number. For example, cSCK-pa70-ca30 could only capture ca. 1200 protons. Because all of the particles each have more than 5000 amines, those amines not participating in buffering could be either already protonated at pH 7.0, or unable to be protonated due to being close to the interior of the NP even at pH 5.5. Calculations based on the titration curves over the range of pH from 4-9 support the former explanation.

Figure 3.

A) Relative buffering capacity for the cSCKs. Each bar represents the number of amines per NP, as expected from the particle size and composition. Grey area represents the fraction of amines that absorb protons when pH is changed from 7.0 to 5.5, calculated from potentiometric titration. Other amines (white area) are either already protonated at pH 7.0, or are unable to be protonated at pH 5.5. B) Zeta potential of the particles at pH 7.0 and 5.5.

Zeta potential values of the cSCKs were obtained at pH 7.0 and pH 5.5 (Figure 3B). All particles were found to be positively charged at both pHs. However, at pH 5.5, the zeta potential was generally 5-10 mV above that at pH 7.0, except for cSCK-ta80-ca20, which showed very little difference (23.4 mV at pH 5.5 and 23.8 mV at pH 7.0). For the cSCK-pa-ta series, increasing zeta potential was observed with increasing tertiary amine content at both pH 5.5 and pH 7.0; cSCK-ta100 showed the highest charge (31.8 mV at pH 5.5 and 26.7 mV at pH 7.0), and cSCK-pa100 showed the lowest charge (21.7 mV at pH 5.5 and 13.2 mV at pH 7.0). Despite being more charged, cSCK-ta100 did not have higher binding affinity for DNA compared with cSCK-pa100, as evidenced in the gel retardation assay (vide supra), which is likely due to the steric hindrance of the N-methyl groups.

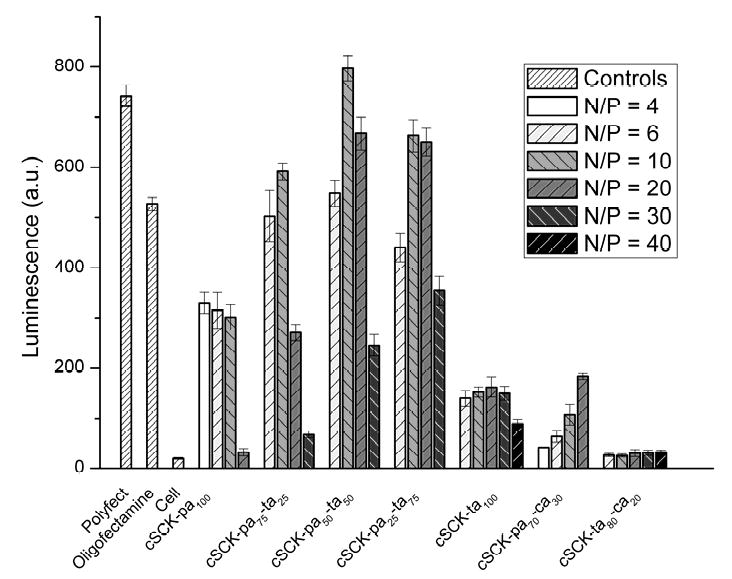

Transfection of ps-MeON by cSCKs

To rapidly and quantitatively compare the cell transfection efficiences of the modified cSCKS using ps-MeON, we adopted the luciferase splice correction assay developed by Kole and coworkers. This assay relies on a luciferase gene (pLuc705) that results in a longer, mis-spliced mRNA that encodes a defective luciferase. In the presence of a phosphorothioate 2′-O-methyl-oligodeoxyribonucleotide (ps-MeON) CCUCUUACCUCAGUUACA, complementary to the aberrant splice site, correct splicing is restored in a dose-dependent and sequence-specific manner, resulting in an active luciferase. To determine the optimal N/P ratio for a given type of cSCK, we tested the splice correcting efficiciency of a range of cSCK/ps-MeON ratios, using Oligofectamine and Polyfect as positive controls and cells with no additives as a negative control (Figure 4). The highest luciferase activities were observed for the 100% amine-containing cSCKs with 50:50 and 25:75 primary:tertiary amine ratios at N/P ratios of 10:1∼20:1. The best among these was cSCK-pa50-ta50 at an N/P 10:1 which gave higher levels of transfection than both Polyfect and Oligofectamine. The N/P ratio at which a given cSCK achieved its maximum luciferase activity coincided with the N/P ratio required to bind all the ps-ODN in the gel retardation assay. This indicates that to achieve maximum luciferase activity, all the ps-ODN must be bound to the cSCK. Differences in the maximum values suggest differences in endocytosis and/or endosomal release efficiencies, since the better-performing particles (cSCK-pa-ta) all have similar buffering capacities in the pH 5.5-7.0 range and, therefore, should all be able to disrupt the endosomes. It may be that the cSCK with a 50:50 mix of primary and tertiary amines has an optimal binding affinity for the ps-MeON for delivery and subsequent release from the cSCK. cSCKs with more tertiary amines may not bind the ps-MeON tightly enough for transport during endocytosis, or may not be endocytosed as efficiently. Conversely, cSCKs with more primary amine may be better at endocytosis and/or bind too tightly to the ps-MeON and prevent release during endosomal disruption. These results agree well with the finding that acetylation of polyethylenimine enhances gene delivery by weakening polymer/DNA interactions [36].

Figure 4.

Luciferase splice correction activity of cSCK-ps-MeON at different N/P ratios, compared to the commercially available transfection agents Oligofectamine and Polyfect, after 24 h incubations with 0.5 μM ps-MeON. Transfection agent concentrations used: Polyfect 20 μg/mL, Oligofectamine 5 μg/mL. For N/P = 1:1, the concentrations of cSCK-pa100, cSCK-pa75-ta25, cSCK-pa50-ta50, cSCK-pa25-ta75, cSCK-ta100, cSCK-pa70-ca30 and cSCK-ta80-ca20 were 1.33, 1.55, 1.56, 1.53, 1.58, 2.77 and 1.82 μg/mL, respectively.

Introduction of carboxylates into the shell greatly reduced luciferase activity at all N/P ratios. For cSCK-pa70-ca30 at an N/P ratio of 4:1, the luciferase activity was only 7% of the Oligofectamine control and only increased to about 25% at its maximum activity at an N/P ratio of 20:1. For cSCK-ta80-ca20, maximum luciferase activity occurred at an N/P ratio of 20:1 and was only about 5% compared with Oligofectamine. The poor efficiency of the particles containing carboxylic acids can be explained by their reduced buffering capacity in the pH 5.5-7.0 range, and lower affinity for binding the ps-MeON.

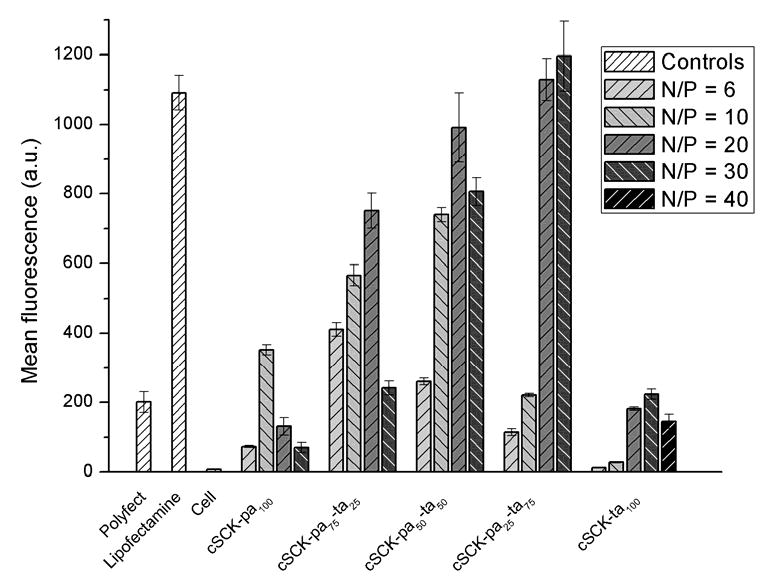

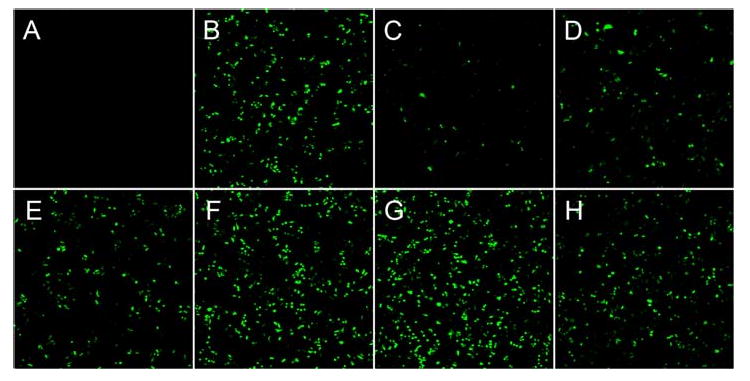

Transfection of plasmid DNA by cSCKs

To quantify the delivery of plasmid DNA by the cSCKs, we assayed the fluorescence of HeLa cells transfected with the EGFP expressing plasmid pEGFP-N1 by flow cytometry (Figure 5). In general, the higher the percentage of tertiary amine in the cSCK, the higher the EGFP expression level. The highest level of EGFP expression was observed for cSCK-pa25-ta75 at N/P of 20:1 to 30:1, which exceeded that for Lipofectamine 2000 and Polyfect, and the lowest level for cSCK-ta100 and cSCK-pa100. The trend paralleled what was observed for ps-ODN delivery. Confocal microscopy showed similar results with cSCK-pa50-ta50 and cSCK-pa25-ta75 at N/P ratios of 20:1 producing the highest numbers of transfected cells (Figure 6). The number of transfected cells appeared higher with the cSCKs than with Liopfoectamine 2000, although the mean of fluorescence of the cells is almost same. We attribute this effect to the increased cytotoxicity of Lipofectamine 2000 (vide infra). Compared with Lipofectamine 2000, Polyfect showed low plasmid delivery, giving ca. 20% mean fluorescence, although it outperformed Lipofectamine 2000 in oligo delivery. It is worth noting that the cSCKs with 50-75% tertiary amines gave higher transfection than both Polyfect and Lipofectamine 2000, in both oligo and plasmid delivery experiments.

Figure 5.

Flow cytometry analysis of transfection of plasmid DNA by the cSCKs. The green fluorescent protein encoding pEGFP-N1 (1.0 μg) was transfected into HeLa cells with various N/P ratios. Transfection agent concentrations used: Polyfect 6.67 μg/mL, Lipofectamine 2000 3.33 μg/mL. For N/P = 1:1, the concentrations of cSCK-pa100, cSCK-pa75-ta25, cSCK-pa50-ta50, cSCK-pa25-ta75 and cSCK-ta100 were 0.78, 0.87, 0.88, 0.85 and 0.88 μg/mL, respectively.

Figure 6.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy of HeLa cells transfected with pEGFP-N1 (4.0 μg) by cSCKs at specific N/P ratios. A) No transfection agent, B) Lipofectamine 2000 (4 μg/mL), C) Polyfect (8 μg/mL), D) cSCK-pa100 (7.52 μg/mL, N/P = 10:1), E) cSCK-pa75-ta25 (8.32 μg/mL, N/P = 10:1), F) cSCK-pa50-ta50 (17.0 μg/mL, N/P = 20:1), G) cSCK-pa25-ta75 (16.3 μg/mL, N/P=20:1), H) cSCK-ta100 (17.0 μg/mL, N/P = 20:1).

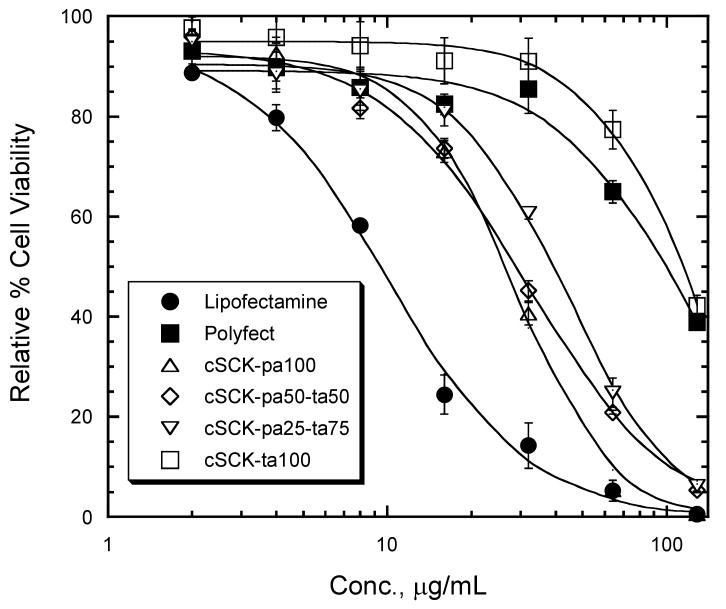

cSCK cytotoxicity

We evaluated the cytotoxicity of the modified cSCK in HeLa cells by a fluorescence assay for measuring cellular ATP concentration (Figure 7). All of the cSCKs were less toxic than Lipofectamine 2000 (LC50 = 10 ± 1 μg/mL), with the cSCK bearing all primary amines (cSCK-pa100) being the most toxic (28 ± 1.5 μg/mL). In contrast the cSCK bearing all tertiary amines (cSCK-ta100) was the least toxic (117 ± 4 μg/mL) and was similar in toxicity to Polyfect (111 ± 9 μg/mL). The cSCKs that showed the best transfection efficiencies for ps-ON and plasmid (cSCK-pa50-ta50 and cSCK-pa25-ta75) were of similar or slightly less cytotoxicity (31 ± 2 and 42 ± 2 μg/mL respectively) to cSCK-pa100. All cSCKs showed better than about a 25% loss in viability at 20 μg/mL compared to a 75% loss of viability with the same concentration of Lipofectamine 2000. The results clearly show that the tertiary amines confer less cytotoxicity than the primary amines.

Figure 7.

Relative cell viability of HeLa cells in the presence of cSCKs and commercial transfection agents.

Conclusions

We have been able to increase the plasmid DNA- and ps-MeON-transfection efficiency and minimize the cytotoxicity of cSCKs by introducing tertiary amines into the shell by chemical modification of the precursor block copolymer. cSCKs with tertiary/primary amine ratios of 50:50 and 75:25 achieved equal or better transfection efficiency for ps-MeON at N/P ratios of ∼10:1 - 20:1 compared to Oligofectamie or Polyfect, the current gold standards, with lower cytotoxicity than Lipofectamine 2000. These same cSCKs also showed high plasmid transfection efficiencies, comparable to Lipofectamine 2000, at N/P ratios of ∼20:1 - 30:1. We ascribe the high efficiency of these particles to an optimum nucleic acid binding affinity, required to transport the pDNA or ps-MeON into the cell through endocytosis, and buffering capacity in the pH 5.5-7 range, to achieve endosomal disruption and subsequent release of nucleic acid. These modifications and the resulting changes in transfection efficiency have also helped to better elucidate the structure-activity relationships of the cSCKs. Even higher efficiencies are expected when the particles are conjugated with appropriate ligands for receptor-mediated endocytosis such as the tripeptide RGD for integrin receptors, and moieties for enhancing endosomal release, which are currently under study.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health as a Program of Excellence in Nanotechnology (NHLBI-PEN HL080729). We thank Dr. R. Kole (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) for the pLuc705 HeLa cell line. We also thank Professor Donald Elbert for use of the Brookhaven Zeta Plus zeta potential analyzer.

Footnotes

The total number of amines per particle is estimated based on the mean core size of the particles as measured from TEM images. The number of protontated amines is calculated from the potentiometric titration curve.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pack DW, Hoffman AS, Pun S, Stayton PS. Design and development of polymers for gene delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2005;4:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nrd1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reineke TM, Grinstaff MW. Designer materials for nucleic acid delivery. MRS Bull. 2005;30(9):635–638. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verma IM, Somia N. Gene therapy - promises, problems and prospects. Nature. 1997;389:239–242. doi: 10.1038/38410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taira K, Kataoka K, Niidome T. Non-Viral Gene Therapy. Tokyo, Japan: Springer Tokyo; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raper SE, Yadkoff M, Chirmule N, Gao GP, Nunes F, Haskal ZJ, et al. A pilot study of in vivo liver-directed gene transfer with adenoviral vector in partial ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:163–175. doi: 10.1089/10430340152712719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y, Ishii T, Cabral H, Kim HJ, Seo JH, Nishiyama N, et al. Charge-conversion polyionic complex micelles - efficient nanocarriers for protein delivery into cytoplasm. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48(29):5309–5312. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green JJ, Langer R, Anderson DG. A combinatorial polymer library approach yields Insight into nonviral gene delivery. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41(6):749–759. doi: 10.1021/ar7002336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peer D, Jeffery MK, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. NatNanotechnol. 2007;2:751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Huang L. Nonviral gene therapy: promises and challenges. Gene Ther. 2000;7:31–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lomas H, Canton I, MacNeil S, Du J, Armes SP, Ryan AJ, et al. Biomimetic pH sensitive polymersomes for efficient DNA encapsulation and delivery. Adv Mater. 2007;19:4238–4243. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewert KK, Ahmad A, Bouxsein NF, Evans HM, Safinya CR. Methods in molecular biology. Totowa, NJ United States: Humana Press Inc.; 2008. Non-viral gene delivery with cationic liposome-DNA complexes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanazs A, Armes SP, Ryan AJ. Self-assembled block copolymer aggregates: from micelles to vesicles and their biological applications. Macromol Rapid Comm. 2009;30:267–277. doi: 10.1002/marc.200800713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kichler A, Frisch B, Lima de Souza D, Schuber F. Receptor-mediated gene delivery with non-viral DNA carriers. J Liposome Res. 2000;10(4):443–460. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guy J, Drabek D, Antoniou M. Delivery of DNA into mammalian cells by receptor-mediated endocytosis and gene therapy. Mol Biotechnol. 1995;3:237–248. doi: 10.1007/BF02789334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malek A, Czubayko F, Aigner A. PEG grafting of polyethylenimine (PEI) exerts different effects on DNA transfection and siRNA-induced gene targeting efficacy. J Drug Target. 2008:124–139. doi: 10.1080/10611860701849058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sung SJ, Min SH, Cho KY, Lee S, Min YJ, Yeom YI, et al. Effect of polyethylene glycol on gene delivery of polyethylenimine. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26(4):492–500. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mishra S, Webster P, Davis ME. PEGylation significantly affects cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of non-viral gene delivery particles. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83(3):492–500. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han M, Oba M, Nishiyama N, Kano MR, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Kataoka K. Enhanced percolation and gene expression in tumor hypoxia by PEGylated polyplex micelles. Mol Ther. 2009;17(8):1404–1410. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho YW, Kim JD, Park K. Polycation gene delivery systems: escape from endosomes to cytosol. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2003;55:721–734. doi: 10.1211/002235703765951311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee CC, Liu Y, Reineke TM. General structure-activity relationship for poly(glycoamidoamine)s: the effect of amine density on cytotoxicity and DNA delivery efficiency. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:428–440. doi: 10.1021/bc7001659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yezhelyev MV, Qi L, O'Regan RM, Nie S, Gao X. Proton-sponge coated quantum dots for siRNA delivery and intracellular imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(28):9006–9012. doi: 10.1021/ja800086u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang K, Fang H, Wang Z, Taylor JSA, Wooley KL. Cationic shell-crosslinked knedel-like nanoparticles for highly efficient gene and oligonucleotide transfection of mammalian cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30:968–977. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee Y, Miyata K, Oba M, Ishii T, Fukushima S, Han M, et al. Charge-conversion ternary polyplex with endosome disruption moiety: A technique for efficient and safe gene delivery. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2008;47(28):5163–5166. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honda M, Kataoka K, Seki T, Takeoka Y. Intelligent polymeric micelles from functional poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(amino acid) block copolymers. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2009;61(10):768–784. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oba M, Aoyagi K, Miyata K, Matsumoto Y, Itaka K, Nishiyama N, et al. Polyplex micelles with cyclic RGD peptide ligands and disulfide cross-links directing to the enhanced transfection via controlled intracellular trafficking. Mol Pharmaceutics ASAP. doi: 10.1021/mp800070s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang H, Remsen EE, Wooley KL. Amphiphilic core-shell nanospheres obtained by intramicellar shell crosslinking of polymer micelles with poly(ethylene oxide) linkers. Chem Commun. 1998;13:1415–1416. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thurmond KBI, Remsen EE, Kowalewski T, Wooley KL. Packaging of DNA by shell crosslinked nanoparticles. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(14):2966–2971. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.14.2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Read ES, Armes SP. Recent advances in shell cross-linked micelles. Chem Commun. 2007;29:3021–3035. doi: 10.1039/b701217a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang K, Fang H, Chen Z, Taylor JSA, Wooley KL. Shape effects of nanoparticles conjugated with cell-penetrating peptides (HIV Tat PTD) on CHO cell uptake. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1021/bc800160b. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pochan DJ, Chen Z, Cui H, Hales K, Qi K, Wooley KL. Toroidal triblock copolymer assemblies. Science. 2004;306:94–97. doi: 10.1126/science.1102866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang K, Rossin R, Hagooly A, Chen Z, Welch MJ, Wooley KL. Folate-mediated cell uptake of shell-crosslinked spheres and cylinders. J Polym Sci, Part A: Polym Chem. 2008;46:7578–7583. doi: 10.1002/pola.23020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luger K, Mäder AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang H, Zhang K, Shen G, Taylor JSA, Wooley KL. Cationic shell-crosslinked knedel-like (cSCK) nanoparticles for highly efficient PNA delivery. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2009;6:615–626. doi: 10.1021/mp800199w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma Q, Wooley KL. The preparation of tbutyl acrylate, methyl acrylate, and styrene block copolymers by atom transfer radical polymerization: precursors to amphiphilic and hydrophilic block copolymers and conversion to complex nanostructured materials. J Polym Sci, Part A: Polym Chem. 2000;38:4805–4820. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun G, Hagooly A, Xu J, Nyström AM, Li Z, Rossin R, et al. Facile, efficient approach to accomplish tunable chemistries and variable biodistributions for shell cross-linked nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9(7):1997–2006. doi: 10.1021/bm800246x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabrielson NP, Pack DW. Acetylation of polyethylenimine enhances gene delivery via weakened polymer/DNA interactions. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(8):2427–2435. doi: 10.1021/bm060300u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]