Abstract

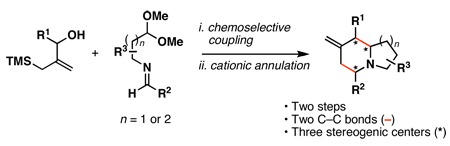

A convergent synthesis of stereodefined indolizidines and quinolizidines is described through chemoselective allyltransfer between 2-hydroxymethyl substituted allylic silanes and imines. Overall, highly substituted heterocycles that contain three stereogenic centers and up to four fused rings are accessed in two steps from relatively simple coupling partners.

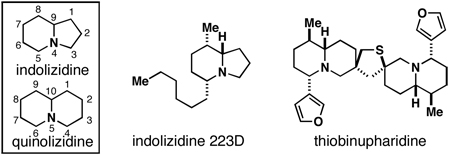

Substituted indolizidines and quinolizidines are heterocyclic motifs encountered in a range of bioactive natural products (Figure 1).1 As such, these heterocycles have been the topic of considerable interest in organic and medicinal chemistry. Successful strategies for the assembly of substituted indolizidines and quinolizidines embrace a large swath of chemical reactivity spanning simple nucleophilic addition to cycloaddition, sigmatropic rearrangement, radical cyclization, C–H activation, iminium ion-based cyclization and intramolecular reductive coupling.2 The great wealth of strategies reported to access these bicyclic heterocycles reflects the level of interest from the chemical community, and the challenges associated with the synthesis of these often highly substituted and stereodefined systems. Here, we report a convergent stereoselective synthesis of substituted indolizidines and quinolizidines (1) through a chemoselective coupling of functionalized allylsilanes with imines (2+3; Figure 2). This fragment union reaction, envisioned to proceed by chemoselective allyltransfer, was sought as a mechanism to deliver highly substituted and stereodefined allylsilanes (4).3 Subsequent acid-promoted cationic annulation4 was then anticipated to furnish substituted indolizidines and quinolizidines (1) in a stereoselective manner.5, 2i

Figure 1.

Introduction to indolizidines and quinolizidines.

Figure 2.

Indolizidine and quinolizidine synthesis by: 1) chemoselective allyltransfer, and 2) cationic annulation.

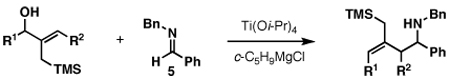

While allylic silanes of general structure 2 are useful for the synthesis of pyrans (via oxocarbenium ion chemistry6) and substituted five membered rings (via metal catalyzed TMM chemistry7), these substrates have not been described as allyltransfer reagents of the type required here (2+3→4). Nevertheless, we speculated that Ti-mediated chemoselective allyltransfer between hydroxymethyl substituted allylsilanes (2) and imines (3) has the potential to furnish homoallylic amines of general structure 4. Here, allylation would proceed by a mechanism that engages the unique reactivity of allylic alchohols,8 in preference to well-established allyltransfer chemistry associated with allylic silanes.3 Overall, the desired chemoselective coupling would deliver a product whereby the allylsilane moiety remains intact for subsequent heterocycle synthesis (4→1).

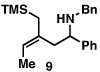

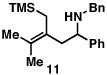

Our initial exploration of the required chemoselective coupling reaction is illustrated in Table 1. Overall, preformation of a Ti–imine complex (5, Ti(Oi-Pr)4, c-C5H9MgCl, Et2O, −78 to −30 °C),9 followed by addition of a preformed lithium alkoxide of the allylic alcohol leads to successful C–C bond formation. Interestingly, substitution at the allylic position plays an important role in regioselection. Coupling of the simple allylic silane 6 with aromatic imine 5 provides a 1,3-amino alcohol as the major product. Here, C–C bond formation occurs at C2 of the allylic alcohol and delivers a product containing a quaternary center (7). Moving to the secondary allyic alcohol 8, very high levels of chemo-and stereoselectivity are observed in reductive cross- coupling with imine 5. Here, allylsilane 9 is produced as a single isomer in 70% yield. As depicted in entry 3, this chemoselective coupling reaction is suitable for formation of allylsilanes bearing tetrasubstituted alkenes (11). Finally, use of allylic alcohols containing trisubstitued alkenes (12) is possible in this coupling reaction and provides allylic silanes (13) with very high levels of stereoselectivity (entry 4).

Table 1.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | allylic silane | yield(%) | E:Z | dr | major producta |

| 1 |  |

75 | – | – |  |

| 2 |  |

70 | 20:1 | – |  |

| 3 |  |

70 | – | – |  |

| 4 |  |

51 | 20:1 | 20:1 |  |

Reaction conditions: Imine (1 equiv), Ti(Oi-Pr)4 (1.5 equiv), c-C5H9MgCl (3.0 equiv), allylic alkoxide (1.5 equiv), Et2O (−78 °C to rt).

The desired homomoallylic amine product was isolated in 18% yield.

The relative stereochemistry of 13 was assigned by analogy to previous examples.8

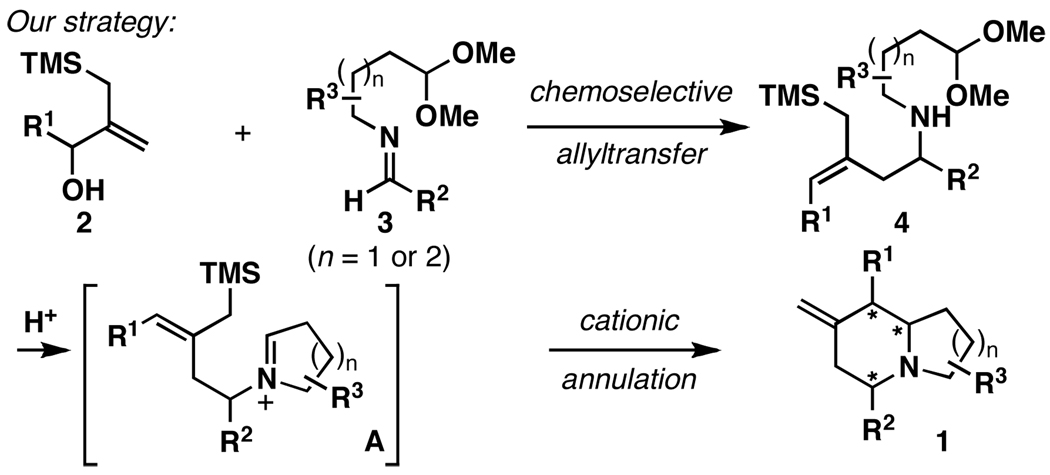

With a method in hand for chemoselective allyltransfer, we initiated studies aimed at application of this transformation to the synthesis of complex indolizidine and quinolizidine indolizidine systems (4→1). To accomplish this, our investigations began with the study of the simple aromatic imine 14 (Figure 3; eq 1). Gratifyingly, the reductive cross-coupling reaction with 8 defines an effective means of preparing the stereodefined acetal-containing allylsilane 15 (66%; E:Z ≥ 20:1). Acid-promoted cyclization then proceeds in good yield, and delivers the stereodefined trisubstituted indolizidine 16 in 88% (dr ≥ 20:1). As depicted in eq 2, use of imine 17 in this two-step annulation process provides a similarly facile and stereoselective pathway to the trisubstituted quinolizidine 19.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of complex heterocycles.

Applying a recently described procedure for the coupling of aliphatic imines with allylic alcohols,10 this convergent heterocycle-forming process can be used to prepare systems containing all-alkyl substitution (eq 3). Again, indolizidine formation occurs in high yield (95%), with superb stereoselection (dr ≥ 20:1) and furnishes 7-exo-methylene indolizidine 223D (22).11

Delighted that this synthetic strategy proved successful for the synthesis of simple indolizidine and quinolizidine architectures (16, 19, and 22), we questioned whether this process would be useful for the synthesis of more complex polycyclic systems. As depicted in eqs 4–6, use of substrates that contain additional functionality between the imine and acetal leads to the formation of complex stereodefined polycyclic heterocycles in a concise and stereoselective fashion.

In conclusion, we have defined a new convergent bond construction that serves as a powerful foundation for heterocycle synthesis. A unique chemoselective functionalization of hydroxymethyl-substituted allylic silanes provides a facile and stereoselective entry to the indolizidine and quinolizidine core. In addition to highlighting the utility of this heterocycle preparation in the synthesis of 7-exomethylene indolizidine 223D, we have demonstrated the basic coupling process for the assembly of complex polycyclic heterocycles containing furans, thiophenes and indoles. While the control of absolute stereochemistry in this annulations remains a challenge, the present contribution defines a reaction sequence of broad utility for heterocycle synthesis. Due to, 1) the ubiquitous nature of indolizidines and quinolizidines in natural products and small molecules of biomedical relevance, 2) the ready availability of the coupling partners, 3) the functional group compatibility of the chemoselective allyltransfer reaction, 4) the stereoselectivity of the cationic annulation, and 5) the inexpensive nature of the reductive cross-coupling process, we look forward to future developments that emerge from these initial findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge financial support of this work by the National Institutes of Health – NIGMS (GM80266 and GM80266-04S1).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and tabulated spectroscopic data for new compounds (PDF) are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/paragonplus/submission/jacsat/.

References

- 1.Michael JP. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:191. doi: 10.1039/b509525p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For selected examples, see: Overman LE. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:6432. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.05.067. Franklin AS, Overman LE. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:505. doi: 10.1021/cr950021p. Tang X-Q, Montgomery J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:6950. Denmark SE, Martinborough EA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:3046. Denmark SE, Cottel JJ. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006;348:2397. Padwa A. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:6421. doi: 10.1021/jo901300x. Chiacchio U, Padwa A, Romeo G. Curr. Org. Chem. 2009;13:422. Davis FA, Yang B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:8398. doi: 10.1021/ja051452k. Amorde SM, Judd AS, Martin SF. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2031. doi: 10.1021/ol050544b.

- 3.For recent reviews on the chemistry of allylic silanes, see: Chabaud L, James P, Landais Y. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004:3173. Masse CE, Panek JS. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:1293.

- 4.For recent reviews of N-acyliminium ion-based cyclization, see: Maryanoff BE, Zhang H-C, Cohen JH, Turchi IJ, Maryanoff CA. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:1431. doi: 10.1021/cr0306182. Speckamp WN, Hiemstra H. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:4367.

- 5.For examples of cationic cyclization of allylic silanes for the synthesis of heterocycles, see: Grieco PA, Fobare WF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:5067. Hiemstra H, Sno MHAM, Vijn RJ, Speckamp WN. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:4014. Gelas-Mialhe Y, Gramain J-C, Hajouji H, Remuson R. Heterocycles. 1992;34:37.

- 6. Mekhalfia A, Markó IE, Adams H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:4783. Markó IE, Bayston DJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:6595. Markó IE, Dumeunier R, Leclercq C, Leroy B, Plancher J-M, Mekhalfia A, Bayston DJ. Synthesis. 2002;958 For related reactions: Huang H, Panek JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:9836. Roush WR, Dilley GJ. Synlett. 2001:955. Semeyn C, Blaauw RH, Hiemstra H, Speckamp WN. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:3426. doi: 10.1021/jo971192s.

- 7.Yamago S, Nakamura E. Org. React. 2002;61:1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi M, McLaughlin M, Micalizio GC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3648. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For reviews on the use of Ti-alkoxides in reductive coupling chemistry, see: Kulinkovich OG, de Meijere A. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:2789. doi: 10.1021/cr980046z. Sato F, Urabe H, Okamoto S. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:2835. doi: 10.1021/cr990277l.

- 10.Tarselli MA, Micalizio GC. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4596. doi: 10.1021/ol901870n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daly JW, Garrafo HM, Spande TF, Yeh HJC, Peltzer PM, Cacivio PM, Baldo JD, Faivovich J. Toxicon. 2008;52:858. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.