Abstract

Previous research on housing loss among severely mentally ill persons who have been placed in housing after being homeless has been largely atheoretical and has yielded inconsistent results. We develop a theory of housing loss based on identifying fundamental causes—problems in motives, means and social situation—and test these influences in a longitudinal, randomized comparison of housing alternatives. As hypothesized, individuals were more likely to lose housing if they had a history of alcohol or drug abuse, desired strongly to live independently contrary to clinician recommendations, or were African Americans placed in independent housing. Deficits in daily functioning did not explain these influences, but contributed to risk of housing loss. Our results demonstrate the importance of substance abuse, the value of distinguishing support preferences from support needs, and the necessity of explaining effects of race within a social context and thus should help to improve comparative research.

Keywords: Homelessness, substance abuse, insight, race/ethnicity, community functioning

Loss of housing represents a profound breach in the fabric of normative expectations and social structures that bind individuals to any society. Few situational changes connote so many interrelated losses—in physical security, personal identity, social status, and community connections—particularly among persons with a history of severe mental illness. Yet despite the prevalence of housing loss in this population and the identification of structural factors that increase individuals’ risk of housing loss (Clapham, 2003; Dworsky and Piliavin, 2000; Sosin et al., 1990; Wong and Piliavin, 1997), research focused on individual-level influences on housing loss has not been guided by a theoretical framework and has yielded inconsistent results (Calsyn and Winter, 2002; Kasprow et al., 2000).

Prior research indicates that placement in subsidized housing reduces but does not eliminate the risk of housing loss among homeless persons with mental illness: from 16% to 25% lose their housing one year after housing placement; 50% after five years (Kasprow et al., 2000; Lipton et al., 2000; Lipton, Nutt and Sabitini, 1988:43; Padgett, Gulcur and Tsemberis, 2006; and see Shern et al., 1997). We aim in this analysis to identify the bases of risk of housing loss for formerly homeless mentally ill persons during an extended follow-up period after housing placement. Based on relevant theory and prior research, we hypothesize three fundamental sources of this risk—substance abuse, rejection of needed support, and minority status contingent on housing type. We discuss the implications of our findings for comparative cross-national research and for the development of more powerful social theory.

1. Introduction

Individual behavior is a product of motivation to achieve particular outcomes, beliefs about means to achieve them, and structural constraints and opportunities that affect both motives and means (Lin, 2001: xi). What homeless persons with mental illness want, how they think they can obtain it, and the barriers and facilitators they encounter are the fundamental causes of behavior (Aneshensel, 1992).

1.1 Motives

Safety is a fundamental motivation in the human hierarchy of needs and is endangered by housing loss (Amaral 2003; Maslow, 1943). Yet it is clear that the priority accorded to safety can be overturned by addictive substances that dysregulate, or “hijack,” the brain’s dopamine-based endogenous reward systems (Dackis and O’Brien, 2005; Kalivas and Volkow, 2005:1408). Substance abuse thus involves a “pathology of motivation and choice” (Kalivas and Volkow, 2005; Khantzian et al., 1991; Velasquez et al., 2000) that is consistent with homelessness researchers’ conclusions that addiction is a “socio-economic leveler” (Devine and Wright, 1997) and a “devastating clinical co-morbidity” (Brunette, Mueser, and Drake, 2004).

Substance abuse is consistently the strongest predictor of housing loss (Gonzalez and Rosenheck, 2002; Hurlbut, Hough, and Wood, 1996; Lipton et al., 2000; Mares and Rosenheck, 2004; Tsemberis and Eisenberg, 2000), as well as the most common health problem among homeless individuals (Booth, Sullivan, and Koegel, 2002; Kasprow et al., 2000) and the most common co-morbidity among persons with severe mental illness (Brunette, Mueser and Drake, 2004)—although the rate of comorbidity varies between nations (Teeson 2004). Persons with schizophrenia who abuse substances have more psychotic symptoms and more violent incidents and homelessness and less treatment compliance than their counterparts who do not abuse substances (Dixon, 1999). Even after substance abuse treatment, the relation between substance abuse and housing loss remains (Gonzalez and Rosenheck, 2002; Olfson et al., 1999). Among homeless individuals who achieved stable housing after entering a substance abuse treatment program, only 50% were still stably housed two years later (Orwin, Scott, and Ariera, 2003).

1.2 Means

Social isolation undermines ability to cope with stress, maintain mental health and engage in recovery programs (Aneshensel, 1992; Hawkins and Abrams, 2007; Segal, Baumohl, and Johnson, 1977; Snow and Anderson, 1993; Thoits, 1983). Lower levels of social support are associated with more frequent psychiatric hospitalization, less use of mental health services, higher rates of depression, and less residential stability (Calsyn and Winter, 2002; Rogers et al., 2004). International data highlights the social vulnerability of persons with schizophrenia (Harrison, 2001).

In spite of their potential value as sources of support, homeless persons with severe mental illness mostly reject group living and support staff (Daniels and Carling, 1986). Herrman (2004) reported high rates of social withdrawal among homeless persons with psychotic disorders in Australia. Clinicians, by contrast, believe that most severely mentally ill persons need professional support and would benefit from roommates (Goldfinger and Schutt, 1996; Minsky et al., 1995). Outpatients with schizophrenia who assessed their own daily functioning skills much more positively than did their case managers actually performed more poorly than did those with more negative self-assessments (Bowie et al., 2007). Persons with schizophrenia (Amador et al., 1994) or bipolar disorder (Pini et al., 2001) who do not recognize illness-related impairments in their lives— who lack “insight” (Flashman, 2004)--are less likely to maintain treatment, adhere to prescribed medication (Kikkert et al., 2006), accept professionals’ or family members’ advice, or function well in the community (Haywood et al., 1995).

Of course there is no strictly objective way to measure support needed to achieve a specific goal such as maintaining housing. We operationalize lack of insight as mental health service consumers’ rejection of group support when a clinician rates them as needing support.

1.3 Situation

Economic influences (Hurlbut, Hough, and Wood, 1996; Mares et al., 2004) are held constant by our research design (Goldfinger et al., 1999), but situational barriers can still influence particular individuals’ risks of housing loss (Clapham, 2003). In particular, racial discrimination by housing providers, neighbors, or others can reduce housing opportunities (Takeuchi and Williams, 2003; Turner and Reed, 1990; Yanos et al., 2004), and elevated perceptions of discrimination among African Americans (Ross et al., 2001) are associated with higher levels of mistrust, anger, stress and depression (Banks et al., 2006; Kessler et al., 1999; Mobry and Kiecolt, 2005). There is some prior evidence of greater vulnerability to housing loss among homeless persons in the U. S. who are African American (Fischer and Massey, 2004; Folsom et al., 2005; Goldfinger et al., 1999; Lipton et al., 2000; Mares et al., 2004; Rosenheck et al., 2001; Rosenheck et al., 2006; Rosenheck and Seibyl, 1998; Tsemberis and Eisenberg, 2000; Uehara, 1994).

Can type of housing influence the likelihood of discriminatory processes in housing? There are different types of group homes (Greenfield 1992), but they share the potential for generating supportive social relations between staff and residents that can improve community functioning (Kruzich, 1985; Goering et al., 1992; Rahav et al., 1995). Because our ECH housing was designed to develop supportive relations among residents and with staff, we predict that the effect of race will be lessened among those assigned to group housing (Dayson et al., 1998; Hopper and Milburn, 1996).

1.4 Functional Ability

Although functional ability is a complex construct that spans multiple domains (Couture, Penn and Roberts, 2006), it may help to explain the influence of the three risk factors on housing loss (Arns and Linney, 1995; Bowie et al., 2006). In Phoenix, one-third of individuals rated as having more difficulty functioning became homeless one year after moving into independent apartments, compared to 9.5% of those with higher functioning (Franczak, 2002:14).

2. Methods

We investigated housing loss among homeless individuals with serious and persistent mental illnesses who were recruited from transitional shelters in Boston, screened for safety and randomized to either group homes or independent apartments.

2.1 Subjects

Potential participants were recruited from one of the three shelters in Boston that are funded by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health (DMH) for homeless persons with serious mental illness. Homeless persons are referred to these shelters by staff at the city’s generic shelters, by a DMH homeless outreach team that periodically visits the generic shelters, or from other programs; shelter guests are then moved into housing of varying types as it becomes available, but there is no fixed length of stay in the shelters. Each of 303 transitional shelter residents was screened for safety by a clinician to determine whether they would be at risk of harming themselves or others if they were randomized to live on their own. Approximately one-third of the shelter residents were declared ineligible on this basis; another one-third moved or found alternative accommodations prior to the availability of grant housing (Goldfinger et al., 1996a).

The remaining 118 participants were assigned randomly to live either in an independent apartment or in a group home. Of these, 112 were followed for up to 1.5 years, with a primary goal of testing the effect of these housing alternatives on housing retention and other outcomes. Of these participants, 40% were African American (52% were white), 71% were male, 63% had completed high school or a GED. Their average age was 37 and half were identified as substance abusers. Diagnoses were determined with a structured clinical interview (SCID) (Spitzer et al. 1989). Using DSM-IIIR criteria, 70.5% had a primary or secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective or other psychotic or delusional disorders, 17% had a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and 12.5% had a primary diagnosis of major affective disorder.

2.2 Housing Options

We provided two housing options: Independent Living (IL)—scattered site apartments and single room units in buildings with some communal space, and Evolving Consumer Households (ECH)—staffed group homes with 6 to 10 residents and private bedrooms, in which a residential coordinator led weekly tenant meetings and encouraged group decision-making and minimal reliance on staff. The independent living sites were those used by the Department of Mental Health for other clients in similar circumstances; our ECH model provided a more engaging management style and had higher expectations for tenant autonomy than is typical of other group homes in this service system. We assigned subjects randomly to these two housing alternatives (ECH N=63, IL N=55) after receiving their consent, and followed them for a total of eighteen months (and then checked their housing status at 36 months). Subjects paid 30% of their income for rent and utilities.

All subjects were provided an intensive clinical case manager (ICCM). Subjects retained their project-assigned housing, at least initially, after the project’s formal end at 18 months, but at this time the ICCM’s were replaced by intensive case management services.

2.3 Measurement

Housing type was recorded at baseline, after randomization to an ECH or IL. (Goldfinger et al., 1999). A housing timeline was constructed using client self-report, project housing and DMH records, and weekly case manager logs. These data were compiled even for subjects who left project-sponsored housing or withdrew entirely from follow-up research, allowing an “intention-to-treat” analytic approach (Goldfinger et al., 1999). Any client who spent any nights on the streets or in shelters during the project is coded as having experienced housing loss (Lennon et al., 2005), thus maximizing identification of the risk of housing loss (Dworsky and Piliavin, 2000). Housing status was again assessed eighteen months after the project’s end for 81 (72%) of the original 112 project participants through contacts with housing, shelter and service providers.

Doctoral-level clinical psychologists used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R - Patient Edition (SCID-P, 9/1/89 Version) (Spitzer, 1989) to identify diagnoses and lifetime substance abuse (coded as abuse, some use, and nonuse) (validated against composite observer and self-report ratings) (Goldfinger et al., 1996b). Psychiatric diagnosis was dichotomized to distinguish schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders from other diagnoses (bipolar and major affective disorder).

We averaged responses to nine questions concerning residential preferences in an index of consumer housing preference (Cronbach’s α =.72) (Schutt and Goldfinger, 1996). Clinician recommendations were obtained by averaging responses by two experienced, blinded clinicians, after a records review and interview, to create an index of recommended level of support (Cronbach’s α =.84) (Goldfinger and Schutt, 1996). In order to operationalize consumer/clinician discrepancies for this analysis, we dichotomized both indexes at their median and distinguish only those who had a low preference for support but were rated by the clinicians as needing support.

We constructed an overall risk factor score for each subject based on the measures of substance abuse (“abuse”=1; else=0), correspondence of consumer and clinician housing preference (“1” if consumers sought a low level of support when the clinician support recommendations were above the scale median; others were coded as “0”), and being a racial or ethnic minority and living independently (=1, while others were coded as “0”). Thus, the overall risk factor scores ranged from 0 to 3.

Case managers completed Rosen’s (1989) Life Skills Profile (LSP) for each subject at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months after baseline. The total LSP score is the average of the five component index scores across the four followups (Cronbach’s α =.82).

2.4 Analyses

We first present the percentage experiencing homelessness by 18 and 36 months classified by total risk factor score. We then conduct separate logistic regression analyses of likelihood of housing loss by 18 and 36 months. All three risk indicators, their component variables and other controls are entered in a first step, and then the LSP index is entered. We also test for higher order interactions involving the three risk factors.

The loss of 31 cases (28% of 112) for analysis at 36 months creates the possibility that predictors of housing loss may differ from those identified at 18 months due solely to a change in sample composition. We therefore re-analyzed housing loss at 18 months with only the 81 cases having housing loss data at 36 months to see if omitting these cases would change the results. It did not. Sample attrition itself was not correlated with the composite risk factor score (r=.17, NS) nor with any of the individual predictors. We therefore think that the most appropriate assumption to make about the missing cases at 36 months is that their housing loss experience was similar to that for the cases we located. Some are likely not to have been found because they regained housing of some sort and left the service system, while others are likely to have not been found because they began a to live on the streets or in shelters outside of the area. We therefore believe the analysis of housing loss at 36 months would not have yielded different results if we had been able to locate the 31 missing cases and so we present the analysis at 36 months based only on the cases that could be located.

We also estimated the possible consequences of missing data for our 36 month results by re-estimating the regression coefficients for the total sample of 112 based on assuming that that all of those who could not be located had not experienced housing loss and that all of the missing cases had experienced housing loss. The supplementary analysis assuming no housing loss among the missing cases did not result in meaningful differences in the regression results, but the supplementary analysis assuming all the missing cases had lost housing reduced all effects other than substance abuse to non-significance. We discuss these results in our conclusions.

3. Results

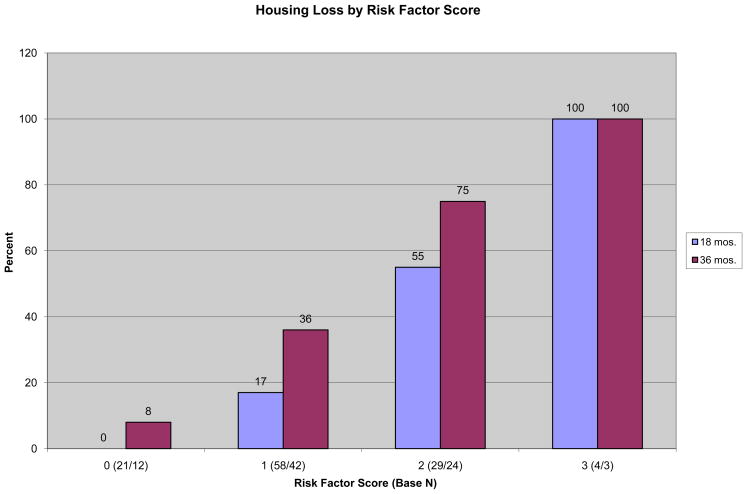

After 18 months, 27% of the 112 participants who been randomized to one of the two housing types had experienced at least one episode of homelessness, rising to 57% of the 81 participants with known housing status at 36 months. After 18 months, none of the 21 subjects with a risk score of zero had experienced homelessness, compared to 17% of those with a risk score of one, more than 50% of those with a risk score of two, and all four subjects with the maximum risk score of 3 (Figure 1). After 36 months, the experience of homelessness had become more common, but the relationship with the composite risk score was no less strong.

Figure 1.

18 months: χ2 = 33.23, df=3, p<.001, η=.54, γ=.85, r=.53. N=112.

36 months: χ2 = 20.31, df=3, p<.001, η=.50, γ=.78, r=.50. N=81.

3.1 Multivariate analysis

The logistic regression of experiencing homelessness by 18 months identifies as significant predictors all three hypothesized risk factors as well as gender and clinician support recommendation (table 1). Poorer life skills, as measured, do not explain the other effects, but independently predict less likelihood of housing retention. Due to the reduced number of cases when the life skills index is included, the coefficient for the weakest of the three risk factor effects--seeking independence when clinicians recommend support--is statistically significant only using a 1-tailed test, but is not diminished in magnitude.

Table 1.

Predictors of Any Homelessness by 18 Mos., Logistic Regression Analysis

| Predictor | Model 1 (β) | Model 2 (β) |

|---|---|---|

| Substance Abuse | 4.025*** | 4.273*** |

| Independent Living preferred, Evolving Consumer Household recommended | 1.717* | 1.8091 |

| African American in Evolving Consumer Household (ECH) | −4.622** | −4.756** |

| Life Skills | ---- | 2.275* |

| ECH | .120 | .148 |

| Minority | 4.389*** | 4.221** |

| Age | −.012 | .002 |

| Gender (female) | 1.735* | 1.999* |

| Education | .196 | .248 |

| Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective | .374 | .279 |

| Prefer ECH | −.008 | .005 |

| ECH recommended | 2.548** | 2.031* |

| Cox & Snell R2, a | .39 | .42 |

| Nagelkerke R2, b | .57 | .62 |

| N | 107 | 105 |

Model 1 (basic model): χ2=53.06, df=11, p<.001.

Model 2 (Life Skills added): χ2=57.41, df=12, p<.001.

Analog of proportion of variance explained in multiple regression analysis.

Analog of proportion of variance explained in multiple regression analysis, adjusted so maximum possible value is 1.00..

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

p<.1 (.05 in 1-tailed test)

There are few differences between the predictors of experiencing homelessness by 36 months and at 18 months (table 2). All three risk factors are statistically significant, controlling for the LSP score. The only other independent predictor of homelessness by 36 months is female gender. In addition, black substance abusers assigned to ILs were much more likely to lose housing (73% compared to 28% in group housing)—a unique effect not apparent at 18 months.

Table 2.

Predictors of Any Homelessness by 36 Mos., Logistic Regression Analysis

| Predictor | Model 1 (β) | Model 2 (β) | Model 3(β) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substance Abuse | 3.423*** | 3.516*** | 5.544*** |

| Independent Living preferred, Evolving Consumer Household recommended | 2.382** | 2.646** | 2.495** |

| African American in Evolving Consumer Household (ECH) | −3.107* | −2.746* | −.732 |

| African American Substance Abuser in Evolving Consumer Household (ECH) | ---- | ---- | −4.632* |

| Life Skills | ---- | 1.678 | ---- |

| ECH | 1.292 | 1.285 | 1.498 |

| Minority | 2.821* | 2.422* | 4.450 |

| Age | .026 | .028 | .047 |

| Gender (female) | 1.734* | 1.893* | 1.908 |

| Education | −.074 | −.093 | −.049 |

| Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective | −.051 | −.253 | −.345 |

| Prefer ECH | .009 | .018 | .003 |

| ECH recommended | .749 | .229 | 1.486 |

| Cox & Snell R2, a | .36 | .38 | .41 |

| Nagelkerke R2, b | .48 | .51 | .55 |

| N | 77 | 77 | 77 |

Model 1 (basic model): χ2=34.01, df=11, p<.001.

Model 2 (Life Skills added): χ2=36.70, df=12, p<.001.

Model 3 (Race * Substance * Housing interaction added): χ2=40.35, df=12, p<.001.

Analog of proportion of variance explained in multiple regression analysis.

Analog of proportion of variance explained in multiple regression analysis, adjusted so maximum possible value is 1.00..

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

4. Discussion

Our theoretically guided investigation of housing loss confirms the importance of the three fundamental risk factors. A lifetime substance abuse diagnosis was a key predictor of housing loss. This key finding reinforces the large body of evidence, accumulated in research around the world, that dual diagnosis is associated with poor prognosis (Dixon, 1999; Teeson et al, 2003; Brunette et al., 2004). Our research provides particularly persuasive evidence of the risks associated with dual diagnosis, since all of our research participants moved into housing at the start of the project and only lost that housing when their behavior interfered with their own or others’ welfare.

Rejection of support that clinicians identified as necessary was also a consistent independent influence on housing loss. We interpret this “discrepancy” effect as reflecting the importance of insight about self-functioning and so as a contribution to the growing literature on the importance of motivation for treatment outcomes (Haywood et al., 1995; Flashman, 2004; Kikkert et al., 2006).

African American residents were more vulnerable to housing loss compared to white residents—much more so if they were living in independent apartments and, by 36 months, if they were also substance abusers. This greater vulnerability of African American tenants is consistent with literature documenting greater structural vulnerability of African Americans at all levels of the housing market, particularly when they are substance abusers. The marked disproportionate risk of housing loss at 36 months for African American substance abusers living on their own was not apparent in this analysis during the 18 months the project was still funded. Perhaps during the funded 18 months, our clinical case management services or our intense focus on housing management lessened the vulnerability of these residents. We suggest that African Americans’ reduced vulnerability to housing loss when living in one of our group homes can be conceptualized as “structural deamplification,” as contrasted to the structural amplification described by Ross et al. (2001) in disadvantaged minority neighborhoods.

Clinician-assessed need for support at baseline had a strong additive effect on housing loss at 18 months, apart from the effect it had in interaction with consumers’ residential preferences. Clinicians were good predictors of living difficulties, but their ability to accurately predict consumer vulnerability to housing loss did not extend to the 36 month follow-up. This decline in the predictive power of clinician ratings suggests that client functioning varied with experience, rather than due to immutable personal attributes that clinicians could identify at one point in time.

Personal vulnerabilities can result in housing loss even after housing is provided. Substance abuse is a critical individual-level risk factor for housing loss, but our research indicates that many consumers with dual diagnoses can maintain housing with appropriate supports. This is consistent with prior research demonstrating the efficacy of multidisciplinary Assertive Community Treatment teams and substance abuse treatment-oriented housing in minimizing housing loss. It is important to note too the lack of importance of some potential predictors. Housing loss did not vary with age or education or diagnosis (even when we distinguished schizophrenia, bipolar illness and major affective disorder).

Our findings also indicate that among chronically homeless persons with severe and persistent mental illness, consumer preferences in themselves are not meaningful predictors of readiness for independent living. The most important concept to measure in order to maximize housing retention is not what people want, but rather how they understand their needs. Our findings also point to the ability of informed clinicians to estimate consumers’ need for support. Research that has attempted to test the value of preference-based housing assignments by using retrospective self-assessments of housing “choice” cannot provide a meaningful test (Greenwood et al., 2005; O’Hara, 2007). How best to develop housing programs that reduce the tradeoff between respecting consumer preferences and minimizing housing loss should be the focus of additional research.

The value of elaborating the process of “structural de-amplification” of the effect of race would be considerable (Ross et al., 2001). We imagine that roommates and live-in staff in the group homes mitigated problems that occurred in connection with the independent apartments—an explanation that is consistent with clinician notes that we have examined (see also Clark et al., 1999; Lincoln et al., 2003).

Functional ability (as measured with the Life Skills Profile) did not explain statistically much of the powerful impact of the fundamental causes on housing loss, although it had an independent effect. Explicit attention to functioning over time could increase identification of intervening processes, as could identification of other factors relevant to functioning. Research with more cases, other longitudinal measures of functioning and quality of life, and a priori causal modeling will be needed to identify fully these multiple pathways of influence.

The limitations of prior research have been both conceptual and methodological. Selection of predictors is often driven by data availability (Kasprow et al. 2000) or by a crude classification of influences as either personal disabilities or situational factors (Christian 2003; Wong and Piliavin 1997). The effects of particular types of housing are often confounded by processes of self-selection or eligibility requirements, so that the effects of disabilities, economic resources and housing type cannot be distinguished (Kasprow et al. 2000; Sosin 2003). Research designs often overlook potentially important process factors, such as social integration (Brunette, Mueser, and Drake 2004; Wong and Solomon 2002). Since the effects of strengths and vulnerabilities interact with each other, in a process that extends over time and is shaped by changes in social context, examining these factors in isolation inevitably understates their explanatory power. Differences in available services (McBride et al. 1998) and in subject characteristics also lead to variability in results.

By limiting our investigation to individuals diagnosed with serious and persistent mental illness and by providing all participants with case management support, we have removed the sources of much of the confounding in prior research of individual and structural risk factors. Housing loss did not occur in our project due to inadequate economic resources, incarceration, or unavailability of health services. Due to randomization to housing type, we know that housing loss did not occur at a differential rate between our group and independent living options because clinicians selected different types of persons for these accommodations or because different types of homeless persons preferred them.

Nonetheless, our research design has some important limitations. Our safety screening process imposed inclusion criteria that limit generalizability and should be assessed carefully in research in other countries and involving different ethnicities. Our research participants were not living on the streets when we recruited them and they had all accepted some services upon moving into the DMH shelters. The group housing that we offered included a sustained effort to empower residents through regular meetings and expectations of group decision-making, and therefore was not fully comparable to group housing that does not provide or encourage such independence. Our group homes also did not provide treatment for substance abuse and their policies about substance abuse varied over time. The replicability of our results must therefore be tested with equally sophisticated designs that involve other housing models, including those that provide a strong substance abuse treatment component, that vary in case management support, that serve even more diverse groups of persons, and that are offered in other national contexts (Brunette, Mueser, and Drake 2004; Christian et al. 2003; Clark and Rich 2003; Schutt et al. 2005). In addition, missing data for 28% of our cases at the 36 month followup leaves our conclusions about housing loss at this point only tentative.

With these cautions in mind, we believe that our research suggests that identification of individuals’ goals and of the means they choose to achieve them should be the starting point for explaining behavior at the individual level. Specification of the particular structural constraints and opportunities faced by different individuals in diverse circumstances will allow more meaningful identification of situational influences. Careful ethnographic investigation can elaborate the process through which people construct meaning in difficult circumstances (Cohen, 2001). Such comparative, mixed method research will allow future investigations of housing loss to contribute to a more general theory of human behavior that can be applied across contexts and cultures.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by National Institute of Mental Health McKinney Research Demonstration Grant #1R18MH4808001, Stephen M. Goldfinger, M.D., Principal Investigator; by the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston; and with the support of the Commonwealth Research Center, Larry J. Seidman, Ph.D., Principal Investigator. We are grateful for the special research assistance provided for this article by Susan So-Young Lee, Megan Reynolds and James C. Beck, M.D. We also thank Carol Caton, Ph.D., Charles Drebing, Ph.D., Anthony Guiliano, Ph.D., Bernice Pescosolido, Ph.D., Robert A. Rosenheck, MD, Ezra Susser, M.D., Mildred A. Schwartz, Ph.D. and the anonymous AJP reviewers for their comments.

Role of Funding Source. Funding for this study was provided by National Institute of Mental Health McKinney Research Demonstration Grant #1R18MH4808001. NIMH staff assisted in the selection of common instruments for a multi-site comparison, but had no further role in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data from this project, in the writing of this report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Follow-up data was collected with the support of the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston and with the support of the Commonwealth Research Center, Harvard Medical School.

Footnotes

Contributors. Authors Stephen M. Goldfinger and Russell K. Schutt designed the study and wrote its protocol with other co-investigators. Author Russell K. Schutt managed the literature searches and analyses for this paper, undertook the statistical analysis for this paper, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to and approved the complete manuscript.

Conflict of Interest. Both authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amador XF, Flaum MM, Andreasen NC, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Clark SC, Gorman JM. Awareness of illness in schizoaffective and mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:826–836. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950100074007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG. The amygdala, social behavior, and danger detection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1000:337–347. doi: 10.1196/annals.1280.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS. Social stress: Theory and research. 1992;18:15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Arns PG, Linney JA. Relating functional skills of severely mentally ill clients to subjective and societal benefits. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:260–265. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M. Social support in the adjustment of pregnant adolescents: Assessment issues. In: Gottlieb Benjamin H., editor. Social Networks and Social Support. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1981. pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Booth BM, Sullivan G, Koegel P. Vulnerability factors for homelessness associated with substance dependence in a community sample of homeless adults. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:429–452. doi: 10.1081/ada-120006735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Determinants of real-world functional performance in schizophrenia subjects: Correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:418–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Twamley EW, Anderson H, Halpern B, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. Self-assessment of functional status in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:1012–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunette MF, Mueser KY, Drake RE. A review of research on residential programs for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2004;23:471–481. doi: 10.1080/09595230412331324590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calsyn RJ, Winter JP. Social support, psychiatric symptoms, and housing: A causal analysis. J Community Psychol. 2002;30:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Christian J. Homelessness: Integrating international perspectives. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2003;13:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Clapham D. Pathways approaches to homelessness research. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2003;13:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Clark C, Rich AR. Outcomes of homeless adults with mental illness in a housing program and in case management only. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:78–83. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. Am Psychol. 1999;54:805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. The search for meaning: Eventfulness in the lives of homeless mentally ill persons in the Skid Row District of Los Angeles. Cult, Med Psychiatry. 2001;25:277–296. doi: 10.1023/a:1011825327636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL. The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: A review. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:S44–S63. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culhane D, Metraux S, Hadley T. Public service reductions associated with placement of homeless persons with serious mental illness in supportive housing. Housing Policy Debate. 2002;13:107–163. [Google Scholar]

- Dackis C, O’Brien C. Neurobiology of addiction: Treatment and public policy ramifications. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1431–1436. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels LV, Carling PJ. Community Residential Rehabilitation Services for Psychiatrically Disabled Persons in Kitsap County, Washington. Boston: Boston University Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation; 1986. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Dayson D, Lee-Jones R, Chahal KK, Leff J. The TAPS Project 32: Social networks of two group homes … 5 years on. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:438–444. doi: 10.1007/s001270050077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine JA, Wright JD. Losing the housing game: The leveling effect of substance abuse. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67:618–633. doi: 10.1037/h0080259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance abuse in schizophrenia: Prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophr Res. 1999;35:S93–S100. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworsky AL, Piliavin I. Homeless spell exits and returns: Substantive and methodological elaborations on recent studies. Soc Serv Rev. 2000;74:193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhoury WKH, Murray A, Shepherd G, Priebe S. Research in supported housing. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:301–305. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0549-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer MJ, Massey DS. The ecology of racial discrimination. City & Community. 2004;3:221–241. [Google Scholar]

- Flashman LA. Disorders of insight, self-awareness, and attribution in schizophrenia. In: Beitman Bernard D, Nair Jyotsna., editors. Self-Awareness Deficits in Psychiatric Patients: Neurobiology, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: W.W. Norton & Co; 2004. pp. 129–158. [Google Scholar]

- Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, Gilmer T, Bailey A, Golshan S, Garcia P, Unützer J, Hough R, Jeste DV. Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:370–376. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franczak MJ. Final Report: Housing Approaches for Persons with Serious Mental Illness. Tucson: Community Rehabilitation Division, School of Public Administration & Policy, University of Arizona; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Goering P, Durbin J, Foster R, Boyles S, Babiak T, Lancee B. Social networks of residents in supportive housing, Community Ment. Health J. 1992;28:199–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00756817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK. Comparison of clinicians’ housing recommendations and preferences of homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:413–415. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK, Seidman LJ, Turner WM, Penk WE, Tolomiczenko G. Self-report and observer measures of substance abuse among Homeless mentally ill persons, in the cross section and over time. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996b;184:667–672. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199611000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK, Turner WM, Tolomiczenko G, Abelman M. Assessing homeless mentally ill persons for permanent housing: Screening for safety. Community Ment Health J. 1996a;32:275–288. doi: 10.1007/BF02249428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK, Tolomiczenko GS, Seidman LJ, Penk WE, Turner WM, Caplan B. Predicting homelessness after rehousing: A longitudinal study of mentally ill adults. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:674–679. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.5.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez G, Rosenheck RA. Outcomes and service use among homeless persons with serious mental illness and substance abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:437–446. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CA, Vuckovic NH, Firemark AJ. Adapting to psychiatric disability and needs for home- and community-based care. Ment Health Serv Res. 2002;4:29–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1014045125695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield AL. Evaluating the quality of care in supervised group homes for persons with mental illness. Adult Res Care J. 1992;6:103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood RM, Schaefer-McDaniel NJ, Winkel G, Tsemberis SJ. Decreasing psychiatric symptoms by increasing choice in services for adults with histories of homelessness. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;36:223–238. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8617-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, Laska E, Siegel C, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: A 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–517. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins RL, Abrams C. Disappearing acts: The social networks of formerly homeless individuals with co-occurring disorders. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:2031–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS. Predicting the ‘revolving door’ phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:856–861. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrman H, Evert H, Harvey C, Gureje O, Pinzone T, Gordon I. Disability and service use among homeless people living with psychotic disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:965–974. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper K, Milburn NG. Homelessness among African Americans: A historical and contemporary perspective. In: Baumohl Jim., editor. Homelessness in America. Phoenix: Oryx Press; 1996. pp. 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Hurlburt MS, Hough RL, Wood PA. Effects of substance abuse on housing stability of homeless mentally ill persons in supported housing. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:731–736. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.7.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C. The Homeless. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TP, Freels SA, Parsons JA, Vongeest JB. Substance abuse and homelessness: Social selection or social adaptation? Addiction. 1997;92:437–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. The neural basis of addiction: A pathology of motivation and choice. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1403–1413. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprow WJ, Rosenheck RA, Frisman L, DiLella D. Referral and housing processes in a long-term supported housing program for homeless veterans. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:1017–1023. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.8.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ, Bean-Bayog M, Blumenthal S, et al. Substance abuse disorders: A psychiatric priority. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1291–1300. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkert MJ, Schene AH, Koeter MWJ, Robson D, Born A, Helm H, Nose M, Goss C, Thornicroft G, Gray RJ. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: Exploring patients’, carers’ and professionals’ views. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:786–794. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruzich JM. Community integration of the mentally ill in residential facilities. Am J Community Psychol. 1985;13:553–564. doi: 10.1007/BF00923267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon MC, McAllister W, Kuang L, Herman DB. Capturing intervention effects over time: Reanalysis of a critical time intervention for homeless mentally ill men. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1760–1776. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Psychological distress among Black and White Americans: Differential effects of social support, negative interaction and personal control. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:390–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton FR, Siegel C, Hannigen A, Samuels J, Baker S. Tenure in supportive housing for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:479–486. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton FR, Nutt S, Sabatini A. Housing the homeless mentally ill: A longitudinal study of a treatment approach. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39:40–45. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabry JB, Kiecolt KJ. Anger in black and white: Race, alienation, and anger. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46:85–101. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares AS, Rosenheck RA. One-year housing arrangements among homeless adults with serious mental illness in the ACCESS program. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:566–574. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares AS, Kasprow WJ, Rosenheck RA. Outcomes of supported housing for homeless veterans with psychiatric and substance abuse problems. Ment Health Serv Res. 2004;6:199–211. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000044746.47589.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow A. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol Rev. 1943;50:370–396. [Google Scholar]

- McBride TD, Calsyn RJ, Morse GA. Duration of homeless spells among severely mentally ill individuals: A survival analysis. Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26:473–490. [Google Scholar]

- McHugo GJ, Bebout RR, Harris M. A randomized controlled trial of integrated versus parallel housing services for homeless adults with severe mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:969–982. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minsky S, Riesser GG, Duffy M. The eye of the beholder: Housing preferences of inpatients and their treatment teams. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:173–176. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara A. Housing for people with mental illness: Update of a report to the President’s New Freedom Commission. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:907–913. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.7.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Mechanic D, Hansell S. Prediction of homelessness within three months of discharge among inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:667–673. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.5.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orwin RG, Scott CK, Arieira CR. Eval Program Plann. Vol. 26. 2003. Transitions through homelessness and factors that predict them: Residential outcomes in the Chicago target cities treatment sample; pp. 379–392. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK, Gulcur L, Tsemberis S. Housing First services for people who are homeless with co-occurring serious mental illness and substance abuse. Res Soc Work Pract. 2006;16:74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pini S, Cassano GB, Dell’Osso L. Insight into illness in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and mood disorders with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:122–125. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahav M, Rivera JJ, Nuttbrock L, Ng-Mak D, Sturz EL, Link BG, Struening EL, Pepper B, Gross B. Characteristics and treatment of homeless, mentally ill, chemical-abusing men. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1995;27:93–103. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1995.10471677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ES, Anthony W, Lyass A. The nature and dimensions of social support among individuals with severe mental illnesses. Community Ment Health J. 2004;40:437–450. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000040657.48759.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen A, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Parker G. The Life Skills Profile: A measure assessing function and disability in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1989;15:325–37. doi: 10.1093/schbul/15.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Fontana A. A model of homelessness among male veterans of the Vietnam War generation. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:421–427. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck RA, Seibyl CL. Participation and outcome in a residential treatment and work therapy program for addictive disorders: The effects of race. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1029–1034. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck RA, Lam J, Morrissey JP, Calloway MO, Stolar M, Randolph F the ACCESS National Evaluation Team. Service systems integration and outcomes for mentally ill homeless persons in the ACCESS program. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:958–966. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Keefe R, McEvoy J, Swartz M, Perkins D, Stroup S, Hsiao JK, Lieberman J. Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:411–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Pribesh S. Powerlessness and the amplification of threat: Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and mistrust. Am Sociol Rev. 2001;66:568–591. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi PH. Down and Out in America: The Origins of Homelessness. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schutt RK, Goldfinger SM. Housing preferences and perceptions of health and functioning among homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:381–386. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutt RK, Goldfinger SM, Penk WE. Satisfaction with residence and with life: When homeless mentally ill persons are housed. Eval Program Plann. 1997;20:185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Schutt RK, Rosenheck RE, Penk WE, Drebing CE, Seibyl CL. The social environment of transitional work and residence programs: Influences on health and functioning. Eval Program Plann. 2005;28:291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Shern DL, Felton CJ, Hough RL, Lehman AF, Goldfinger SM, Valencia E, Dennis D, Straw R, Wood PA. Housing outcomes for homeless adults with mental illness: Results from the Second-Round McKinney Program. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:239–241. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M, Baumohl J, Hopper K. The prevention of homelessness revisited. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. 2001;1:95–127. [Google Scholar]

- Snow DA, Anderson L. Down on Their Luck: A Study of Homeless Street People. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sosin MR. Explaining adult homelessness in the US by stratification or situation. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2003;13:91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Sosin MR, Grossman SF. The individual and beyond: A socio-rational choice model of service participation among homeless adults with substance abuse problems. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38:503–549. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosin MR, Piliavin I, Westerfelt H. Toward a longitudinal analysis of homelessness. J Soc Issues. 1990;46:157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IIIR - Patient Version (SCID-P) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, Felix A, Tsai W, Wyatt RJ. Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: A “critical time” intervention after discharge from a shelter. Am J Pub Health. 1997;87:257–262. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi D, Williams DR. Race, ethnicity and mental health: Introduction to the special issue. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Teeson M, Hodder T, Buhrich N. Alcohol and other drug use disorders among homeless people in Australia. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38:463–474. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeson M, Hodder T, Buhrich N. Psychiatric disorders in homeless men and women in inner Sydney. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:162–168. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Multiple identities and psychological well-being: A reformulation and test of the social isolation hypothesis. Am Sociol Rev. 1983;48:174–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am J Pub Health. 2004;94:651–656. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsemberis S, Eisenberg RF. Pathways to housing: Supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:487–493. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner MA, Reed VM. Housing America: Learning from the Past, Planning for the Future. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Uehara ES. Race, gender, and housing inequality: An exploration of the correlates of low-quality housing among clients diagnosed with severe and persistent mental illness. J Health Soc Behav. 1994;35:309–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez MM, Crouch C, von Sternberg K, Grosdanis I. Motivation for change and psychological distress in homeless substance abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;19:395–401. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YI, Piliavin I. A dynamic analysis of homeless-domicile transitions. Soc Probl. 1997;44:408–423. [Google Scholar]

- Wong YI, Solomon PL. Community integration of persons with psychiatric disabilities is supportive independent housing: A conceptual model and methodological considerations. Ment Health Serv Res. 2002;4:13–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1014093008857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanos PT, Barrow SM, Tsemberis S. Community integration in the early phase of housing among homeless persons diagnosed with severe mental illness: Successes and challenges. Community Ment Health J. 2004;40:133–150. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000022733.12858.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]