Abstract

Background

Few studies have tested the effects of a depression intervention on the risk for death associated with depression.

Objective

To test whether an intervention to improve depression care can modify the risk for death.

Design

Practice-based, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting

20 primary care practices in New York, New York, and Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Patients

1226 randomly sampled patients identified through a 2-stage, age-stratified (60 to 74 years and ≥75 years) depression screening.

Intervention

Depression care manager working with primary care physicians to provide algorithm-based care.

Measurements

Depression status based on clinical interview and vital status at 5 years by using the National Death Index.

Results

At baseline, 396 patients met criteria for major depression and 203 patients met criteria for clinically significant minor depression. After a median follow-up of 52.8 months, 223 patients died. Patients with depression in intervention practices were less likely to have died than those in usual care practices (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.67 [95% CI, 0.44 to 1.00]). Risk for death was reduced in patients with major depression (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.55 [CI, 0.36 to 0.84]) but not in patients with clinically significant minor depression (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.97 [CI, 0.49 to 1.92]). The benefit seemed to be almost entirely attributable to a reduction in deaths due to cancer.

Limitations

The mechanism for an effect on deaths due to cancer is unclear. Depression status, cause of death, and vital status might have been misclassified.

Conclusions

Older primary care patients with major depression in practices that implemented depression care management were less likely to die over a 5-year period than were patients with major depression in usual care practices. The effect seemed to be limited to deaths due to cancer. The mechanism for such an effect is unclear and warrants further investigation.

Prospective, observational studies from many settings have shown that depression is independently associated with an increased risk for death (1–5). However, few studies have evaluated whether an intervention focused on depression can modify this risk. Intervention studies that have reported on death in patients with depression have serious limitations: They lacked randomization to the intervention condition (6–8), focused only on patients after cardiovascular events (9–12), or adjusted for treatment in examining the association of depression with death rather than studying the effect of treatment (6, 13).

In our study, we analyzed the relationship between a depression care management intervention and the risk for death among older primary care patients during a 5-year interval. We used data from the Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT), which we supplemented with data from the National Death Index (NDI). The PROSPECT was an effectiveness study designed to assess the effect of care management on reducing risk factors for late-life suicide (14). It integrated a randomized trial with a population-based, public health model. The study intervention was implemented at the practice level and involved a depression care manager working with physicians to provide algorithm-based care (14). The primary care practice was the unit of randomization, and practices that were not randomly assigned to the intervention were expected to provide usual care. Patients were not assigned to receive specific treatments, so patients and their physicians in the intervention and usual care practices decided whether patients would receive depression treatment. Our research question focused on whether this practice-level intervention influenced a patient-level outcome, namely survival. We hypothesized that older adults with depression in practices randomly assigned to a depression management intervention would experience an attenuated risk for death compared with those patients in usual care practices. Guided by published criteria for performing and reporting subgroup analyses (15, 16), we were particularly interested in whether the effects of care management were specific to patients meeting standard criteria for major depression (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, fourth edition [DSM-IV] [17]).

Context

Persons with depression are more likely to die, but studies have not shown that treatment of depression reduces mortality.

Contribution

Investigators observed a 45% reduction in the hazard of death among patients with major depression cared for in primary care practices that were randomly assigned to a depression care management program.

Cautions

The reduction in deaths occurred almost exclusively among patients who died of cancer. The mechanism for the effect is unclear and might be due to misclassification of cause of death or vital status.

Implication

A practice-level depression care management program seemed to reduce deaths due to cancer in older patients with major depression.

—The Editors

METHODS

Study Sample

The PROSPECT was conducted in 20 primary care practices located in greater New York, New York, and Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from May 1999 to August 2001, with individual patients followed for 2 years. After being paired by urban location, academic affiliation, size, and population type, practices were randomly assigned to the intervention or to usual care by coin flip (cluster randomization by practice). Patients were recruited from an age-stratified (60 to 74 years and ≥75 years), random sample of patients with upcoming appointments. Research associates confirmed study eligibility (age ≥60 years, Mini-Mental State Examination score ≥18 [18], and English-speaking) of consenting patients and screened patients for depression by using the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (19).

Eligibility Criteria

All patients scoring greater than 20 on the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale were invited to enroll. Patients from a 5% sample with lower scores were also invited for assessment of false-negative results on screening. To increase the sensitivity of screening, the PROSPECT investigators also recruited patients with scores less than 20 and positive responses to questions about previous depression episodes or treatment. Research associates met patients at the practice, obtained written consent, and administered a baseline interview (20). The sampling strategy yielded a cohort that approximated a representative sample of attendees of the PROSPECT practices, with oversampling of patients with depression symptoms.

Depression Assessment

We conducted a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders Axis I (SCID-I) and allowed for the full range of DSM-IV diagnoses for depression disorders (17, 21). Our investigation focused on patients targeted by the intervention, that is, patients who met DSM-IV criteria for major depression (17) or who had clinically significant minor depression, defined by DSM-IV criteria for minor depression that we modified by requiring 4 depression symptoms, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) score of 10 or more, and duration of 4 weeks or more (22). To minimize variation in applying criteria for depression, the Cornell Advanced Center for Intervention and Services Research, White Plains, New York, conducted regular teleconferences with research associates to review diagnostic practices and conduct reliability assessments. Ongoing monitoring indicated excellent reliability within and across sites for SCID-I assessments (intraclass correlation, 0.78 to 1.00).

Assessment of Patient Characteristics

We obtained baseline information on age, sex, marital status, self-reported ethnicity, educational attainment, and smoking status (according to tobacco use within the past 6 months). We included ethnicity in describing our sample because it has been associated with patterns of mental health service use (23, 24). Patients self-reported having a medical comorbid condition according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index (25). The 24-item HDRS measured depression severity (26), and the Scale for Suicidal Ideation indicated the presence of suicidal ideation (27).

Description of Usual Care and Intervention Groups

Practices randomly assigned to usual care received educational sessions for primary care physicians and notification of the depression status of their patients. No specific recommendations were given to physicians about individual patients, except for psychiatric emergencies. The following were made available to practices randomly assigned to the intervention: educational sessions for primary care physicians, education for patients’ families, and a depression care manager who worked within the practice. The care manager implemented the intervention by reviewing patients’ depression status, medical history, and medication use and subsequently worked with the primary care physician to recommend treatment according to standard guidelines.

Care managers had psychiatric backup, including on-demand consultation, weekly supervision by psychiatrist-investigators, and monthly interpersonal therapy cross-site supervision. They were introduced to patients by research associates immediately after the baseline interview. The 15 care managers included social workers, nurses, and psychologists who interacted with patients in person or by telephone at scheduled intervals and as necessary. Care managers focused efforts on depression treatment (not on care for medical conditions or preventive services) by monitoring symptoms, adverse effects of medications, and treatment adherence.

All patients with depression received citalopram for first-line treatment. Citalopram therapy was initiated at 10 mg before bedtime on the first day, 20 mg/d for the next 6 days, and 30 mg/d subsequently. After 6 weeks, the target dosage was maintained if the patient exhibited a substantial improvement (≥50% reduction in the HDRS score) (26) and was increased if the patient exhibited a partial improvement (30% to 50% reduction in the HDRS score). Nonresponders, for whom guidelines called for switching to another antidepressant, were defined as patients who did not demonstrate either minimal improvement after 6 weeks of treatment at the target dosage or substantial improvement after the dose was increased to the maximum recommended dose after 12 weeks of treatment (28). For patients who had not responded at 12 weeks, the health specialist followed guidelines for switching antidepressants (28). Health specialists informed patients and their family members about the possible occurrence of specific side effects and to contact them if side effects occurred. When side effects occurred, health specialists provided support and, if warranted, asked primary care physicians to adjust doses or time of administration or to institute symptomatic treatment (28). The PROSPECT treatment algorithm also took account whether patients were already being treated for depression. For example, for patients already receiving pharmacotherapy who remained symptomatic, the care manager optimized the current antidepressant before switching patients to another antidepressant (28).

Interpersonal therapy could be used alone or as an augmentation strategy, depending on whether the patient tolerated the antidepressant therapy and on the presence or absence of a partial response. Care managers from each site, all of whom had some experience in psychotherapy for depression, participated in interpersonal therapy training at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh. In both study groups, physicians were informed by letter if patients reported any suicidal ideation and immediately when patients were identified as being at high risk for suicide according to prespecified guidelines. Other sources detail the PROSPECT treatment algorithm and implementation, including the role of the care manager (29), strategy for pharmacotherapy (28), management of suicidal ideation (30, 31), and types and proportions of treatment received over time by patients in practices randomly assigned to the intervention or to usual care (14, 32).

Ascertainment of Vital Status

We used the National Center for Health Statistics NDI Plus (33) to assess vital status. The underlying causes of death that we obtained from NDI Plus are similar to codes assigned by trained nosologists (33, 34). Because querying the NDI required that we provide the National Center for Health Statistics with personal identifiers (for example, Social Security numbers), confidentiality safeguards warrant discussion. We did not transmit any study data along with identifying data or transmit identifying data via e-mail. The 3 PROSPECT sites verified the vital status information obtained from the NDI by physician report of death and match of identifying information for each individual and sent the final version, which was indexed by unique study identifier and stripped of personal identifiers, to the School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania Data Core, Philadelphia, for production of the analytic data set. We obtained written consent, including permission to obtain death certificate information, from each patient. Our study received approval from the institutional review boards at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; University of Pittsburgh Medical School, Pittsburgh; and Weill Medical College of Cornell University, White Plains, and from independent review at the National Center for Health Statistics.

Statistical Analysis

Our analysis involved sorting patients into 6 groups according to baseline depression status (major, minor, or nondepressed) and practice randomization assignment (intervention or usual care) to allow for examination of the main effects and the interaction of depression status and study group by using the mortality experience of each group. We compared baseline patient characteristics across the groups by using linear and logistic regression with random effects to account for patient clustering by practice. For the death outcome, we used the Cox model, adjusting SEs for within-practice clustering (35). We began by exploring potential confounding variables by using univariate models with baseline characteristics as predictors of time to death. Our final model included influential covariates identified by their association (P < 0.05) with the outcome of interest, time to death. The final adjusted model included terms for baseline age, sex, education, smoking status, cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, cognition, and suicidal ideation. We performed an additional analysis by using the Charlson score to adjust for medical comorbid conditions. We prepared survival curves by using the Kaplan–Meier method (36) to illustrate the mortality rate in each group.

To evaluate our prespecified study hypothesis, we used a test for effect modification of intervention assignment on the risk for death by baseline depression status. The formal test for effect modification introduced terms representing interaction and main effects for depression status and intervention condition into the Cox model. We assessed the proportional hazards assumption by including time-dependent terms in the unadjusted model and measuring the global effect (37). We used SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina), for these analyses. We set an α level of 0.05 to denote statistical significance, recognizing that tests of statistical significance are approximations to aid interpretation and inference.

Role of the Funding Source

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

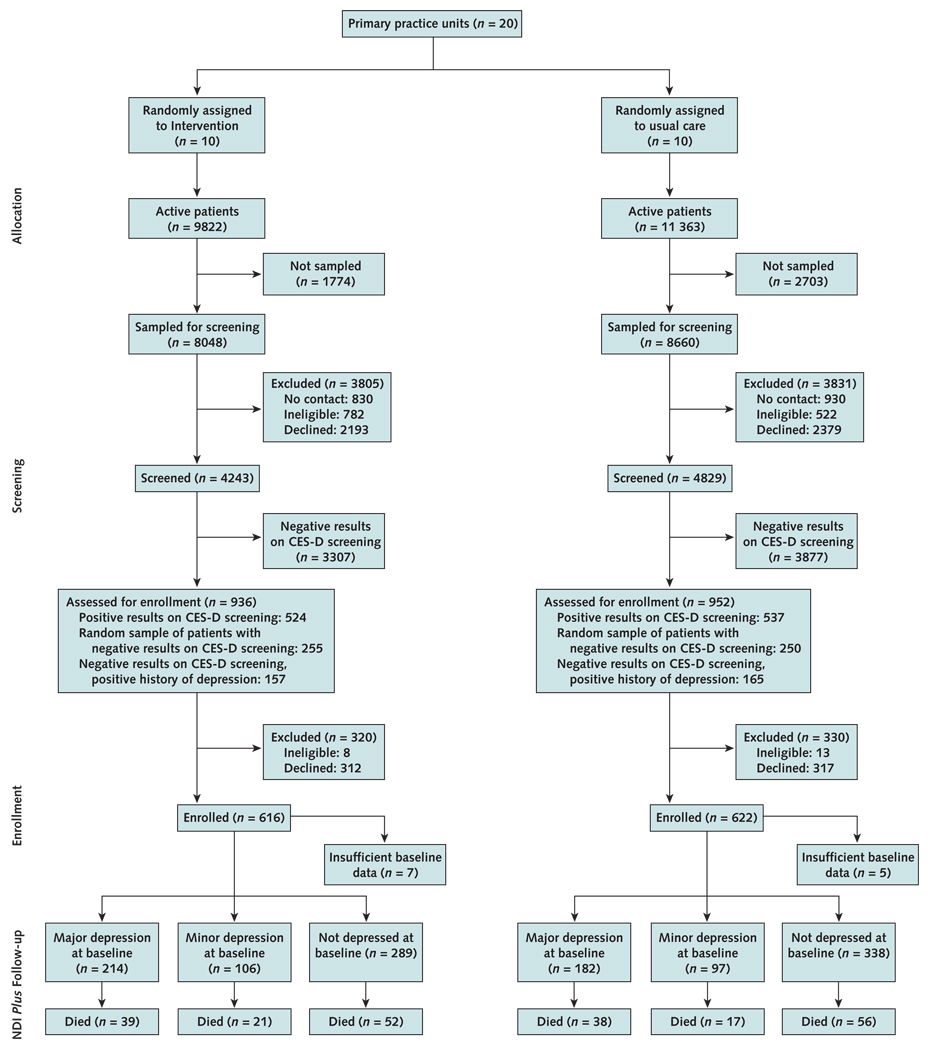

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for the PROSPECT trial has been published elsewhere (14). Figure 1 shows a flow diagram for our investigation. After 5 years, 223 patients had died: 108 patients without depression (17%) and 115 patients with depression (19%). The median length of follow-up in ascertainment of vital status was 52.8 months (range, 0.8 to 68.4 months). Table 1 shows baseline characteristics for all patients with depression in the intervention and usual care groups. Of the baseline characteristics, suicidal ideation statistically significantly differed across groups, with a higher proportion of patients in the intervention group having 1 or more symptoms on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

CES-D = Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; NDI = National Death Index.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics*

| Variable | Intervention Group (n = 320) | Usual Care Group (n = 279) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Mean age (SD), y | 71 (7.8) | 70 (8.1) | 0.144 |

| Women, n (%) | 221 (69) | 208 (75) | 0.139 |

| Ethnic minority, n (%)† | 93 (29) | 103 (37) | 0.69 |

| Mean education (SD), y | 13 (3.3) | 13 (5.1) | 0.37 |

| Married, n (%) | 116 (36) | 104 (38) | 0.53 |

| Habit, n (%) | |||

| Current smoker | 35 (11) | 15 (5) | 0.051 |

| Medical conditions, n (%) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 150 (48) | 115 (42) | 0.131 |

| Stroke | 78 (25) | 55 (20) | 0.164 |

| Diabetes | 70 (23) | 53 (19) | 0.40 |

| Gastrointestinal tract disease | 88 (28) | 74 (27) | 0.91 |

| Cancer | 41 (13) | 48 (17) | 0.068 |

| Respiratory diseases | 42 (14) | 43 (16) | 0.36 |

| Cognition and depression‡ | |||

| Mean MMSE score for cognitive function (SD) | 27 (2.9) | 27 (2.5) | 0.82 |

| Major depression disorder, n (%) | 214 (67) | 182 (65) | 0.74 |

| Mean HDRS score for depression severity (SD) | 19 (6.1) | 18 (5.8) | 0.22 |

| Suicidal ideation (SSI score >0), n (%) | 94 (29) | 56 (20) | 0.010 |

Data from the Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (1999 to 2004) (14). DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition; HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; SSI = Scale for Suicidal Ideation.

Defined as an ethnicity other than non-Hispanic white (total, n = 195; Hispanic, n = 26; non-Hispanic black, n = 159; Asian, n = 4; and other non-Hispanic, n = 6).

Major depression disorder defined as DSM-IV major depression in contrast to clinically significant minor depression (defined as 4 DSM-IV symptom groups, HDRS score ≥10, and ≥4-week duration). Score range for MMSE is 0 to 30 (inclusion criteria limited the range to 18 to 30), with high scores indicating less cognitive impairment. Score range for HDRS is 0 to 76, with high scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. Score range for SSI is 0 to 38, with high scores indicating greater suicidal ideation.

Mortality Rates

Table 2 shows the number of deaths due to specific medical conditions and mortality rates (with 95% CIs) by group assignment stratified by baseline depression status. One documented suicide during the study was identified in data obtained from NDI Plus (Table 2). Among patients with major depression, fewer deaths due to cancer occurred among patients in the intervention group.

Table 2.

Deaths and Mortality Rates from Specific Medical Conditions, by Practice Randomization Group Assignment and Stratified by Baseline Depression Status*

| Medical Condition | Intervention Group | Usual Care Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths, n |

Mortality Rate (95% CI), n/1000 person-years |

Deaths, n |

Mortality Rate (95% CI), n/1000 person-years |

|

| All patients with depression (n = 599) | 60 | 44.7 (34.1–57.6) | 55 | 49.7 (37.4–64.6) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 23 | 17.1 (10.9–25.7) | 15 | 13.5 (7.6–22.3) |

| Stroke | 3 | 2.2 (0.5–6.5) | 4 | 3.6 (1.0–9.2) |

| Cancer | 12 | 8.9 (4.6–15.6) | 18 | 16.3 (9.6–25.7) |

| Respiratory disease | 8 | 6.0 (2.6–11.7) | 3 | 2.7 (0.6–7.9) |

| Accident | 2 | 1.5 (0.2–5.4) | 2 | 1.8 (0.2–6.5) |

| Suicide | 1 | 0.7 (0.0–4.2) | 0 | 0.0 (0.0–3.3) |

| Other diseases | 11 | 8.2 (4.1–14.7) | 13 | 11.7 (6.3–20.1) |

| Patients with major depression disorder (n = 396) | 39 | 43.6 (31.0–59.6) | 38 | 52.3 (37.0–71.8) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 16 | 17.9 (10.2–29.1) | 8 | 11.0 (4.8–21.7) |

| Stroke | 2 | 2.2 (0.3–8.1) | 2 | 2.8 (0.3–9.9) |

| Cancer | 8 | 8.9 (3.9–17.6) | 15 | 20.6 (11.6–34.1) |

| Respiratory disease | 5 | 5.6 (1.8–13.0) | 2 | 2.8 (0.3–9.9) |

| Accident | 1 | 1.1 (0.0–6.2) | 1 | 1.4 (0.0–7.7) |

| Suicide | 0 | 0.0 (0.0–4.1) | 0 | 0.0 (0.0–5.1) |

| Other diseases | 7 | 7.8 (3.1–16.1) | 10 | 13.8 (6.6–25.3) |

| Patients with clinically significant minor depression (n = 203) | 21 | 46.9 (29.1–71.7) | 17 | 44.6 (26.0–71.4) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 7 | 15.6 (6.3–32.2) | 7 | 18.4 (7.4–37.9) |

| Stroke | 1 | 2.2 (0.1–12.5) | 2 | 5.2 (0.6–19.0) |

| Cancer | 4 | 8.9 (2.4–22.9) | 3 | 7.9 (1.6–23.0) |

| Respiratory disease | 3 | 6.7 (1.4–19.6) | 1 | 2.6 (0.1–14.6) |

| Accident | 1 | 2.2 (0.1–12.5) | 1 | 2.6 (0.1–14.6) |

| Suicide | 1 | 2.2 (0.1–12.5) | 0 | 0.0 (0.0–9.7) |

| Other diseases | 4 | 8.9 (2.4–22.9) | 3 | 7.9 (1.6–23.0) |

| Patients without depression (n = 627) | 52 | 41.7 (31.2–54.7) | 56 | 38.0 (28.7–49.3) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 20 | 16.1 (9.8–24.8) | 19 | 12.9 (7.8–20.1) |

| Stroke | 3 | 2.4 (0.5–7.0) | 4 | 2.7 (0.7–6.9) |

| Cancer | 12 | 9.6 (5.0–16.8) | 17 | 11.5 (6.7–18.4) |

| Respiratory disease | 4 | 3.2 (0.9–8.2) | 5 | 3.4 (1.1–7.9) |

| Accident | 3 | 2.4 (0.5–7.0) | 0 | 0.0 (0.0–2.5) |

| Suicide | 0 | 0.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0 | 0.0 (0.0–2.5) |

| Other diseases | 10 | 8.0 (3.8–14.8) | 11 | 7.5 (3.7–13.3) |

Data from the Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (1999 to 2004) (14).

Risk for Death

Table 3 shows the final adjusted and unadjusted Cox proportional hazards model in the variable-specific effects on time to death. We derived all adjusted hazard ratio estimates from models that included terms for potentially influential covariates, namely age, sex, educational attainment, smoking status, baseline comorbid conditions (cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer), baseline Mini-Mental State Examination score, and suicidal ideation. No statistically significant departure from the proportional hazards assumption occurred in the model (chi-square = 3.856; P = 0.28). Results were the same in models that adjusted for the Charlson score at baseline (not shown).

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios for Death, by Depression Status and Influential Covariates Assessed at Baseline*

| Baseline Covariate | Hazard Ratio for Death according to Baseline Covariate Status (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted† | |

| Any depression | 1.20 (0.96–1.51) | 1.65 (1.20–2.26) |

| Intervention practice | 1.00 (0.76–1.33) | 1.14 (0.84–1.53) |

|

Depression-by-intervention interaction |

– | 0.59 (0.36–0.95) |

| Demographic variables | ||

| Age | 1.08 (1.06–1.09) | 1.07 (1.05–1.09) |

| Women | 0.50 (0.38–0.65) | 0.49 (0.38–0.63) |

| Education | 0.94 (0.92–0.97) | 0.98 (0.95–1.00) |

| Habit | ||

| Current smoker | 2.11 (1.53–2.91) | 1.41 (0.91–2.18) |

| Medical conditions | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.51 (1.11–2.04) | 1.22 (0.90–1.66) |

| Stroke | 1.36 (0.96–1.92) | 1.10 (0.85–1.42) |

| Diabetes | 1.71 (1.37–2.12) | 1.67 (1.25–2.23) |

| Cancer | 1.53 (1.07–2.19) | 1.47 (1.02–2.11) |

| Cognition and depression | ||

| MMSE score | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | 0.94 (0.92–0.96) |

| Suicidal ideation (SSI score >0) | 1.39 (1.05–1.82) | 1.22 (0.93–1.60) |

Data from the Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (1999 to 2004) (14). MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; SSI = Scale for Suicidal Ideation.

Includes terms for all variables in the table, including intervention condition and depression-by-intervention interaction.

Effect of the Practice-Based Intervention on Death

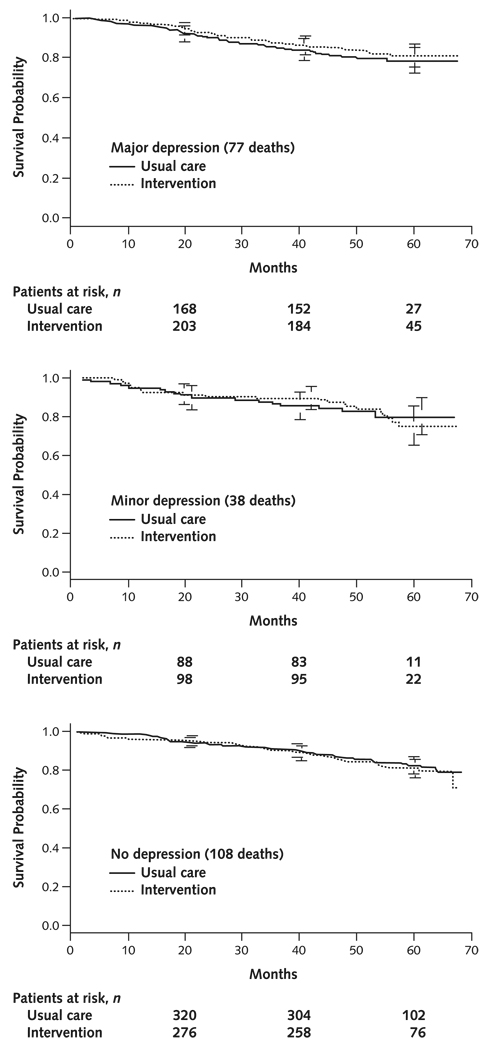

Because of the statistically significant interaction between depression status and the intervention (P = 0.031), we used unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for intervention effects stratified by baseline depression status (major, minor, and nondepressed) (Table 4). For patients with major depression, the intervention was associated with a reduction in deaths (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.36 to 0.84]). The intervention did not statistically significantly differ in deaths among patients with clinically significant minor depression (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.97 [CI, 0.49 to 1.92]) or among patients without depression (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.14 [CI, 0.84 to 1.53]). Figure 2 shows the Kaplan–Meier curves for randomization groups according to baseline depression status. Attrition due to dropout was reflected in the change in number of patients at risk over time (14).

Table 4.

Hazard Ratios for Intervention Effects (Intentionto-Treat Analyses) Stratified by Depression Status Assessed at Baseline*

| Baseline Depression Status | Hazard Ratio for Intervention Effects (95% CI)† |

|

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted‡ | |

| All patients with depression | 0.89 (0.59–1.34) | 0.67 (0.44–1.00) |

| Major depression disorder | 0.83 (0.53–1.29) | 0.55 (0.36–0.84) |

| Clinically significant minor depression | 1.03 (0.51–2.07) | 0.97 (0.49–1.92) |

| Patients without depression | 1.10 (0.81–1.50) | 1.14 (0.84–1.53) |

Data from the Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (1999 to 2004) (14).

Intervention versus usual care.

Includes terms for baseline age, sex, education, smoking, cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, cognition, and suicidal ideation.

Figure 2.

Survival curves and 95% CIs for patients with major depression (top), minor depression (middle), or no depression (bottom) in practices randomly assigned to the intervention or usual care group.

Data from Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (1999 to 2004) (14).

DISCUSSION

Depression has been linked to increased deaths, approximately doubling the risk for death in community samples across a wide range of depression assessment strategies (1–5). In our study, compared with older adults receiving usual care, older adults with depression in practices randomly assigned to an intervention consisting of a depression care manager working with primary care physicians to provide algorithm-based care were less likely to die. We found a statistically significant interaction between depression status and practice intervention assignment. Specifically, older adults in the intervention group who met standard criteria for major depression were less likely to die over the 5-year follow-up than were older adults who met criteria for major depression in the usual care group.

The reduction in death seemed to be almost entirely attributable to a reduction in deaths due to cancer. The mechanism for this effect is not apparent. Few investigators (we are aware of none from an intervention trial) have reported data pertaining to cause of death in association with depression assessed prospectively (see review [38]). By linking prospective New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area study interview data with the Connecticut Tumor Registry, Desai and colleagues (39) found that women with major depression were at increased risk for late-stage breast cancer diagnoses compared with women without major depression. Although this supports the plausibility that deaths due to cancer, for example, might be diminished if major depression were managed more appropriately, the potential for misclassification in cause of death derived from death certificates may be substantial and evidence of a potential association of practice intervention assignment and specific causes of death must be viewed as an opportunity for generation of hypotheses to be tested in future intervention research.

The PROSPECT intervention reduced hopelessness and depression (14, 40). Depression and hopelessness have been studied as independent predictors of increased deaths in observational studies, which have also drawn attention to the link among depression, cardiovascular disease, and death (1, 2). Intervention trials, such as the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) trial (9, 10) and the Sertraline Anti-Depressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART) (11), have focused on depression treatment for persons with advanced cardiovascular disease (7). The ENRICHD trial did not show any benefit on risk for death over a 40-month follow-up, and researchers did not report separate analyses for patients with major depression. Secondary analysis from ENRICHD showed that an antidepressant prescription (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) was associated with reduction in all-cause mortality (12). The SADHART reported a statistically nonsignificant beneficial trend after 24 weeks for a combined outcome of death and nonfatal cardiovascular events for patients with a major depression disorder after myocardial infarction (11). Perhaps the target population represented by the ENRICHD and SADHART samples were further along in the pathway between depression and death than were participants in PROSPECT, whose sample was derived from community practices. The focus of depression treatment in high-risk patients may need to be counterbalanced by attention to primary health care and other community settings to achieve maximum reductions in depression-related deaths (40).

We cannot rule out the possibility that the mortality rate reduction we observed among patients with depression in intervention practices may be due to factors other than the specific effects of a depression management program, such as the nonspecific effects of having an additional person in the practice. We found no evidence for a substantial effect of the intervention on survival for patients with clinically significant minor depression or among patients who did not meet criteria for depression. Rather, the effect of this practice-level intervention on patient-level outcomes depended on the baseline depression status of the patient, that is, the effect of the PROSPECT intervention on death was modified by major depression status. Unützer and colleagues (41) found that an intervention designed to test the cost-effectiveness of a targeted package of preventive services did not attenuate the risk for death associated with high depression symptoms. The beneficial effect of placing a depression care manager in practices seems to be specific to depression care and is not because of the general influence of an additional clinician in a practice on the medical care of other conditions that might affect death. Nevertheless, the specific mediators between practice intervention assignment and patient outcomes deserve further study, including patient adherence, patterns of long-term care for mental health and physical conditions, and improvement in depression.

Although our findings deserve attention, we recognize that our methods have limitations. Misclassification of depression status can result in misleading inference. Depression and other mental health problems may be underestimated in the elderly because stigma leads many elderly persons to minimize reports of sadness or anhedonia and to attribute other symptoms of depression to physical health causes (42, 43). On the other hand, the prevalence of psychopathology can be inflated by misattributing symptoms of medical illness, medication side effects, or treatment sequelae to depression. An advantage of PROSPECT was the use of sensitive instruments (that is, the SCID-I and HDRS, which are accepted semistructured clinical interviews) by trained research associates in conducting a thorough evaluation of depression diagnosis and severity. Research associates were expected to respond to visual cues (tearfulness, appearance, and demeanor), to challenge inconsistencies (patients who report no activities yet deny anhedonia), and to request clarification (for example, “Is sleep disturbance due to frequent awakening to use the bathroom or rumination that disturbs the ability to fall asleep after using the bathroom?”). This approach contrasts sharply with other studies that used survey instruments, retrospective recall, or nonstandardized clinical assessments.

Misclassification of vital status was also a potential limitation of our study findings. However, our experience and that of others suggest a minimal likelihood of misclassification given our methods. For example, in the 9-year follow-up of the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (4), 1194 deaths were identified among a cohort of 3560 persons through a variety of sources, including the NDI. Survivors were confirmed through self-report, relatives, and medical records. National Death Index data confirmed 1187 of these deaths (99.4% correct classification of decedents) and correctly classified all survivors (that is, there were no false-negative results). The investigators obtained this high rate of coverage before implementation of the current computerized reporting system (NDI Plus) that includes cause of death and, unlike our study, did not benefit from the use of Social Security numbers in searching the NDI. Similarly, the overall sensitivity of the NDI for ascertainment of vital status was 98% in the Nurses’ Health Study (44) and has been much greater than 90% in most studies (see review [34]).

We believe that our investigation has implications for public health, primary care organization, and mental health services research methods. Mental health services research differs in design, implementation, and inference from other types of intervention research. The design of PROSPECT and our analytic strategy reflect the contrasts among an observational study of treatment received, a randomized trial with strictly prescribed treatment, and an effectiveness trial like PROSPECT that has features of both. In PROSPECT, adequacy of treatment of individuals can be thought of as independent from intervention assignment. Because PROSPECT was an effectiveness trial focused on how services were delivered, the intervention versus usual care assignment represented different probabilities that a patient with depression recruited into the study would receive adequate treatment. Inference from trials of practice-level interventions may require reasoning that differs from inference in observational studies or in patient-randomized clinical trials.

Depressed older adults are much more likely to present and be managed in primary care settings (23), and our study underscores the public health effect that could accrue by providing resources to help primary care clinicians better manage psychological distress and psychiatric disturbances. We need to avoid the temptation to apply simple fixes because patients and providers differ widely in expectations, beliefs, preferences, and experiences about mental health (45). The backdrop of varying patient and provider perspectives needs to be studied and considered in any redesign that seeks to mitigate system-level factors that currently discourage integration of mental health treatment into primary care settings—integrated care that is preferred by patients and providers (46). If we are to prepare for the increasing need for mental health services among older persons and to ease the burden of disability associated with depression, we must engage primary care practices as partners in developing services that interrupt the pathway from depression to death.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: The mortality follow-up of PROSPECT participants was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (principal investigator, Joseph J. Gallo, MD, MPH [R01 MH065539]). The PROSPECT was a collaborative research study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. The 3 groups included in the funded study were the Advanced Centers for Intervention and Services Research of Cornell University (coordinating center; principal investigator, George S. Alexo-poulos, MD, and co-principal investigators, Martha L. Bruce, PhD, MPH, and Herbert C. Schulberg, PhD [R01 MH59366, P30 MH68638]), University of Pennsylvania (principal investigator, Ira Katz, MD, PhD, and co-principal investigators, Thomas Ten Have, PhD, and Gregory K. Brown, PhD [R01 MH59380, P30 MH52129]), and University of Pittsburgh (principal investigator, Charles F. Reynolds III, MD, and co-principal investigator, Benoit H. Mulsant, MD [R01 MH59381, P30 MH52247]). Additional small grants came from Forest Laboratories and the John D. Hartford Foundation. Participation of Drs. Gallo, Bogner, Post, and Bruce was also supported by National Institute of Mental Health awards (K24 MH070407, K23 MH67671, K23 MH01879, and K02 MH01634). Dr. Bogner is a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar (2004 to 2008).

Footnotes

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: J.J. Gallo, H.R. Bogner, M.L. Bruce.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: J.J. Gallo, H.R. Bogner, K.H. Morales, J.Y. Lin, M.L. Bruce.

Drafting of the article: J.J. Gallo, H.R. Bogner, K.H. Morales, M.L. Bruce.

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: J.J. Gallo, H.R. Bogner, K.H. Morales, E.P. Post, M.L. Bruce.

Final approval of the article: J.J. Gallo, H.R. Bogner, K.H. Morales, E.P. Post, M.L. Bruce.

Statistical expertise: K.H. Morales, E.P. Post.

Obtaining of funding: J.J. Gallo, E.P. Post, M.L. Bruce.

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: E.P. Post.

Collection and assembly of data: J.J. Gallo, E.P. Post, M.L. Bruce.

References

- 1.Schulz R, Drayer RA, Rollman BL. Depression as a risk factor for non-suicide mortality in the elderly. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:205–225. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, Ten Have T, Bruce ML. Depression, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and two-year mortality among older, primary-care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:748–755. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.9.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruce ML, Leaf PJ. Psychiatric disorders and 15-month mortality in a community sample of older adults. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:727–730. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, Rozal GP, Florio L, Hoff RA. Psychiatric status and 9-year mortality data in the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:716–721. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penninx BW, Geerlings SW, Deeg DJ, van Eijk JT, van Tilburg W, Beek-man AT. Minor and major depression and the risk of death in older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:889–895. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rovner BW, German PS, Brant LJ, Clark R, Burton L, Folstein MF. Depression and mortality in nursing homes. JAMA. 1991;265:993–996. doi: 10.1001/jama.265.8.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Talajic M. Depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;91:999–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy GJ, Kelman HR, Thomas C. Persistence and remission of depressive symptoms in late life. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:174–178. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, Carney RM, Catellier D, Cowan MJ, et al. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3106–3116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Freedland KE, Youngblood M, Veith RC, Burg MM, et al. Depression and late mortality after myocardial infarction in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:466–474. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000133362.75075.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glassman AH, O’Connor CM, Califf RM, Swedberg K, Schwartz P, Bigger JT, Jr, et al. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288:701–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor CB, Youngblood ME, Catellier D, Veith RC, Carney RM, Burg MM, et al. Effects of antidepressant medication on morbidity and mortality in depressed patients after myocardial infarction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:792–798. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kouzis A, Eaton WW, Leaf PJ. Psychopathology and mortality in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30:165–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00790655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Katz II, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothwell PM. Treating individuals 2. Subgroup analysis in randomised controlled trials: importance, indications, and interpretation. Lancet. 2005;365:176–186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oxman AD, Guyatt GH. A consumer’s guide to subgroup analyses. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:78–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-1-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Assoc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raue PJ, Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML, Klimstra S, Mulsant BH, Gallo JJ. The systematic assessment of depressed elderly primary care patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:560–569. doi: 10.1002/gps.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured clinical interview for Axis I DSM-IV disorders (SCID) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Assoc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams JW, Jr, Barrett J, Oxman T, Frank E, Katon W, Sullivan M, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: A randomized controlled trial in older adults. JAMA. 2000;284:1519–1526. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallo JJ, Marino S, Ford D, Anthony JC. Filters on the pathway to mental health care, II. Sociodemographic factors. Psychol Med. 1995;25:1149–1160. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, Ford DE. Patient ethnicity and the identification and active management of depression in late life. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1962–1968. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA. Psychometric characteristics of the Scale for Suicide Ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:1039–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulsant BH, Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Katz IR, Abrams R, Oslin D, et al. Pharmacological treatment of depression in older primary care patients: the PROSPECT algorithm. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:585–592. doi: 10.1002/gps.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulberg HC, Bryce C, Chism K, Mulsant BH, Rollman B, Bruce M, et al. Managing late-life depression in primary care practice: a case study of the Health Specialist’s role. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:577–584. doi: 10.1002/gps.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown GK, Bruce ML, Pearson JL. High-risk management guidelines for elderly suicidal patients in primary care settings. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:593–601. doi: 10.1002/gps.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Degenholtz H, Parker LS, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Post E, et al. Treatment as usual (TAU) control practices in the PROSPECT Study: managing the interaction and tension between research design and ethics. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:602–608. doi: 10.1002/gps.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulberg HC, Post EP, Raue PJ, Have TT, Miller M, Bruce ML. Treating late-life depression with interpersonal psychotherapy in the primary care sector. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:106–114. doi: 10.1002/gps.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doody MM, Hayes HM, Bilgrad R. Comparability of national death index plus and standard procedures for determining causes of death in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11:46–50. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sathiakumar N, Delzell E, Abdalla O. Using the National Death Index to obtain underlying cause of death codes. J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40:808–813. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199809000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee E, Wei L, Amato D. Cox-type regression analysis for large numbers of small groups of correlated failure time observations. In: Klein JP, Goel PK, editors. Survival Analysis: State of the Art. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. pp. 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collett D. Modelling Survival Data in Medical Research. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallo JJ, Armenian HK, Ford DE, Eaton WW, Khachaturian AS. Major depression and cancer: the 13-year follow-up of the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area sample (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:751–758. doi: 10.1023/a:1008987409499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Desai MM, Bruce ML, Kasl SV. The effects of major depression and phobia on stage at diagnosis of breast cancer. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1999;29:29–45. doi: 10.2190/0C63-U15V-5NUR-TVXE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bogner HR, Cary MS, Bruce ML, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Mulsant B, Ten Have T, et al. The role of medical comorbidity in outcome of major depression in primary care: the PROSPECT study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:861–868. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.10.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Unützer J, Patrick DL, Marmon T, Simon GE, Katon WJ. Depressive symptoms and mortality in a prospective study of 2, 558 older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:521–530. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200209000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallo JJ, Anthony JC, Muthén BO. Age differences in the symptoms of depression: a latent trait analysis. J Gerontol. 1994;49:P251–P264. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.6.p251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knäuper B, Wittchen HU. Diagnosing major depression in the elderly: evidence for response bias in standardized diagnostic interviews? J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:147–164. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rich-Edwards JW, Corsano KA, Stampfer MJ. Test of the National Death Index and Equifax Nationwide Death Search. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:1016–1019. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wittink MN, Oslin D, Knott KA, Coyne JC, Gallo JJ, Zubritsky C. Personal characteristics and depression-related attitudes of older adults and participation in stages of implementation of a multi-site effectiveness trial (PRISM-E) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:927–937. doi: 10.1002/gps.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gallo JJ, Zubritsky C, Maxwell J, Nazar M, Bogner HR, Quijano LM, et al. Primary care clinicians evaluate integrated and referral models of behavioral health care for older adults: results from a multisite effectiveness trial (PRISM-e) Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:305–309. doi: 10.1370/afm.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]