Abstract

Purpose

Genomic complexity is present in ~15–30% of all CLL and has emerged as a strong independent predictor of rapid disease progression and short remission duration in CLL. We conducted this study to advance our understanding of the causes of genomic complexity in CLL.

Experimental design

We have obtained quantitative measurements of radiation-induced apoptosis and radiation-induced ATM auto-phosphorylation in purified CLL cells from 158 and 140 patients, respectively, and have employed multi variate analysis to identify independent contributions of various biological variables on genomic complexity in CLL.

Results

Here, we identify a strong independent effect of radiation resistance on elevated genomic complexity in CLL and describe radiation resistance as a predictor for shortened CLL survival. Further, using multivariate analysis, we identify del17p/p53 aberrations, del11q, del13q14 type II (invariably resulting in Rb loss) and CD38 expression as independent predictors of genomic complexity in CLL, with aberrant p53 as a predictor of ~50% of genomic complexity in CLL. Focusing on del11q, we determined that normalized ATM activity was a modest predictor of genomic complexity but was not independent of del11q. Through SNP array-based fine mapping of del11q, we identified frequent mono-allelic loss of Mre11 and H2AFX in addition to ATM, indicative of compound del11q-resident gene defects in the DNA-ds-break response.

Conclusions

Our quantitative analysis links multiple molecular defects, including for the first time del11q and large 13q14 deletions (type II), to elevated genomic complexity in CLL, thereby suggesting mechanisms for the observed clinical aggressiveness of CLL in patients with unstable genomes.

Keywords: CLL, genomic complexity, DNA double strand break response

INTRODUCTION

Genomic aberrations substantially influence the biology and clinical outcome of patients with CLL(1–3). Presence of specific chromosomal deletions, in particular del17p and del11q, allows for the identification of a subset of patients with shortened overall survival. Further, CLL patients with chromosomal translocations, complex aberrant karyotypes or elevated genomic complexity, as measured through SNP arrays, have recently been shown to have aggressive CLL that is characterized by rapid disease progression and short remission duration(4–9). An ad-hoc summary analysis of these published reports suggests that CLL cases with these latter genomic complexity characteristics are substantially more common than CLL with del17p or p53 mutations and that the overlap between these two groups of CLL is partial, thus implying existence of additional unidentified factors that cause genomic complexity in CLL.

Subchromosomal deletions, which are the quantitatively dominant genomic aberration in CLL, must have involved DNA-ds-breaks as intermediates. Given that the cellular response to DNA-ds-breaks comprises cell cycle arrest, repair pathway activation or alternatively, apoptotic cell death, it appears rational to assume that defects in DNA-ds-break repair/response pathways are causally linked to subchromosomal genomic complexity in CLL. The two most prominent examples of genes, mutated or defective in subsets of CLL, that are part of the DNA-ds-break repair/response pathways are p53 and ATM and both genes have been linked to more aggressive CLL(1, 10–15). Nonetheless, mutations or aberrations leading to reduced function of either gene are not routinely comprehensively measured in CLL and further, the relationship of aberrations in either gene to CLL with complex genomes has not been systematically investigated in large prospectively analyzed CLL cohorts.

One of the attractive features of genomic complexity assessments as a biomarker for aggressive CLL is the fact that establishing a link between the ineffectiveness of commonly used genotoxic drugs in CLL, an impaired DNA-ds-break apoptotic response and elevated genomic complexity would provide a firm rationale to target CLL with elevated genomic complexity with alternative or non-genotoxic therapies. As many of the most commonly used drugs in CLL therapy, including purine analogues and cyclophosphamide are genotoxic and in the case of fludarabine, have been shown to induce a p53-dependent transcriptional response in CLL cells, assessments of elevated genomic complexity could lead to the development of risk-adapted therapies akin to therapies developed for patients with del17p(16–18).

In addition to genomic aberrations, various biomarkers including ZAP70 expression, IgVH status, CD38 expression and others have been identified in CLL that can dichotomize CLL patient populations into lower and higher risk groups(19–30). However, little information is available regarding a possible link between these various biomarkers and genomic complexity in CLL.

In this study using multivariate analysis, we have comprehensively analyzed the effect of various measurable biomarkers on genomic complexity in CLL. Further, we discovered an impaired cellular apoptotic response to radiation as an independent strong predicting factor for complexity in CLL, thus providing direct experimental evidence for an involvement of an impaired cellular response to DNA damage in the acquisition of genomic lesions. From this data, we conclude that an impaired DNA-ds-break response and multiple genomic deletions, including del17p, del11q and del13q14 type II (Rb loss) are independent strong predictors of genomic complexity in CLL. Combined, this data suggests the existence of multiple independent gene defects in CLL that confer genomic instability. Among these defects, we identify a strong independent effect of aberrant p53 function on genomic complexity in CLL and surprisingly only a modest effect of ATM hypofunction. We identify multiple genes in the response pathway following DNA-ds-breaks (ATM, Mre11 and H2AFX) to be co-deleted through del11q, thus suggesting that the genomic complexity associated with del11q may be caused by compound gene defects(31). Finally, we report for the first time an independent strong effect of del13q14 type II deletions on genomic complexity(32) and have identified reduced Rb expression associated with these larger 13q14 subtypes.

METHODS

Patients

This study is based on CLL patient samples that were as described(6, 12). The trial was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRBMED #2004-0962) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment. Clinical outcome analysis followed previously published definitions(6).

Measurements of radiation-induced apoptosis in CLL

Cryopreserved CLL cells were thawed, washed, and depleted of CD3 and CD14-positive cells using negative selection over Miltenyi Biotec LS columns. Tumor cells thus purified were aliquoted into low-cell-binding tissue culture plates (Nunc #145385) at concentrations of 1.2×107 per ml for Western blotting and 3×106 per ml for apoptosis analysis by flow cytometry. Cells rested for 1 to 1.5 hours prior to treatment with 5 Gy of ionizing radiation (Philips 250 kV X-ray-emitting source). Apoptosis measurement by flow cytometry was carried out after cells had incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 40 to 42 hours post-irradiation, using Annexin V and PI staining and a Becton-Dickinson FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Duplicate measurements of remaining viable cells (Annexin V-negative/PI-negative) for irradiated and paired non-irradiated tumor samples were tabulated.

Detection of p53 aberrations

Sequence analysis of p53 exons 5–9 was available for all studied samples as previously described(12). In addition, p53 immunoblotting results from CLL cells treated with MDM2 inhibitors or solvent were available for 106/178 of the samples as previously described. Given that an aberrant p53 immunoblotting result was never found in the 106 tested samples in the absence of either known p53 sequence mutations, presence of del17p or copy-neutral LOH at 17p (all data available for the entire cohort), we grouped all remaining CLL (N=72) with wt p53 exon 5–9 and absence of either del17p or acquired copy-neutral LOH (aUPD) at 17p as p53 non-aberrant.

Exon resequencing of Mre11a and H2AFX

Primers to amplify and sequence all coding exons of human Mre11a and H2AFX and adjacent intronic sequences were designed using the primer 3 program (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_ www.cgi). The sequences of the primers used are tabulated in Supplementary Table 1. Conditions for PCR amplifications were optimized using gradient temperature PCR conditions and are available upon request. PCR products were generated using Repli-g (Qiagen)-amplified DNA from highly pure sorted CD19+ cells as templates and analyzed as described(12). Mutations were confirmed in unamplified genomic DNA and paired CD3+ cell derived DNA.

Measurements of radiation-induced ATM autophosphorylation in CLL

Cells for Western blot were harvested 20 minutes after irradiation treatment, washed once with 1x PBS, and lysed on ice for 20 minutes with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 100mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 2mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 20mM NaF) supplemented with fresh protease and phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF, and 1X Sigma protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails). Western blots were carried out for both irradiated and non-irradiated CLL-derived tumor samples for phospho-ATM (Ser1981, Rockland Immunochemicals), total ATM (Santa Cruz Biotech), actin (Sigma) and alpha tubulin (Santa Cruz) for all patients. All Western blots included two pooled standard samples and uniform cell equivalent loading to enable quantitation across multiple blots.

Western blots for phospho-Ser-1981-ATM, ATM, and actin were subjected to densitometric quantitation using an Alpha Imager transilluminator (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA) and the SpotDenso feature of this company’s AlphaEaseFC software. An image of each blot film was captured using identical camera exposure settings for all films. For each blot image, identically-sized density measurement rectangles were placed around each protein band of interest, and local background was subtracted for each individual rectangle. Resulting band density values were imported into Microsoft Excel. For each film, the patient sample protein band density values were normalized to the mean value of two standards: pooled patient sample protein lysates run in the same positions in every blot used for the project. Finally, for each patient, the standard-normalized protein band density values for pATM were divided by the respective normalized values for ATM and for actin.

50K-SNP-array profiling of 178 CLL cases

Genomic profiling using SNP arrays was done as previously described(32).

Measurements of normalized Rb, Mre11a and H2AFX expression using Q-PCR

RNA was prepared from ~2×105–106 ultrapure CD19+ FACS sorted cells using the Trizol reagent and resuspended in 50µl DEPC-treated water. Complementary DNA was made from ~20ng of RNA using the Superscript III first strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen) and oligo-dT priming. Primers and TaqMan-based probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Primers-on-demand). Duplicate amplification reactions included primers/probes, TaqMan® 2x Universal PCR Master Mix, No AmpErase UNG and 1µl of cDNA in a 20ul reaction volume. Reactions were done on an ABI 7900HT machine. Normalization of relative copy number estimates for Rb, Mre11a or H2AFX RNA was done with the Ct values for PGK1 as reference (Ct mean gene of interest – Ct mean PGK1).

Statistical Methods

Genomic complexity was defined as ≥3 losses or ≥3 losses plus gains plus UPD=total complexity. Logistic regression was used to relate the presence of genomic complexity (a dichotomous response variable) to potential predictive factors of complexity. All factors of interest were considered in univariate analysis. ALL-FISH data categorize samples independent of degree of clonal involvement; FISH-25 data categorize samples only if ≥25% of nuclei carried the FISH finding as per routine clinical FISH reports from the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). Mean positive cell fraction for FISH categories in this cohort was: del17p (68%), del11q (59%) and del13q14 type II (75%). In multivariate analysis, all models we considered included a core set of four variables: CD38, ZAP-70, IGVH, and del13q type II. Three additional factors were then added to each model: one of the del11q measurements (FISH-25 or ALL-FISH), one of the phospho-ATM measurements, and one of the following four factors: p53 aberrancy status, percent of cells alive post-radiation, and del 17p either as FISH-25 or All-FISH. The latter four factors were grouped because they are mechanistically related. Patients with multiple genomic abnormalities were counted in each category without use of a hierarchical model. For both univariate and multivariate analysis, the relationship between genomic complexity and a given predictive factor was assessed by the odds ratio (conditional odds ratio in multivariate analysis) and its p-value. The polarity of each variable was assigned so that higher levels of coding corresponded to greater univariate risk of complexity. Thus higher risk is associated with greater CD38 and ZAP70 levels, unmutated IgVH, lower normalized phospho-ATM levels, higher percentages of cells alive post-radiation, p53 aberrations and the presence of del13q, del11q, and del17p deletions.

Survivor functions (TTFT, TTST and OS) for CLL subgroups defined by degree of radiation resistance or ATM activity (measured through p-ATM/ATM or p-ATM/actin ratios) are displayed using the method of Kaplan and Meier.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Included in this analysis are data from 178 patients that were previously analyzed for genomic complexity using 50KSNP arrays(6). Data on individual biomarkers including ZAP70 expression, IgVH status, CD38 expression, p53 mutations, CLL FISH, 50K SNP-array data and MDM2 SNP309 allele status were available for all of the 178 cases(6). Depending on availability of sufficient cryopreserved specimens for analysis, radiation-induced apoptosis data were available for 158 cases, normalized p-ATM data for 141 cases and normalized Rb mRNA data for 160 cases. This core dataset was supplemented with additional consecutively enrolled CLL cases specifically for del11q breakpoint mapping using 6.0 SNP array data (not shown) and Mre11a mRNA analysis using Q-PCR (N=220). All analysis described below is solely based on biological specimens collected at the time of study enrollment, thus minimizing bias introduced through CLL clonal evolution or biomarker instability.

Impaired radiation-induced apoptosis is a strong predictor of genomic complexity in CLL

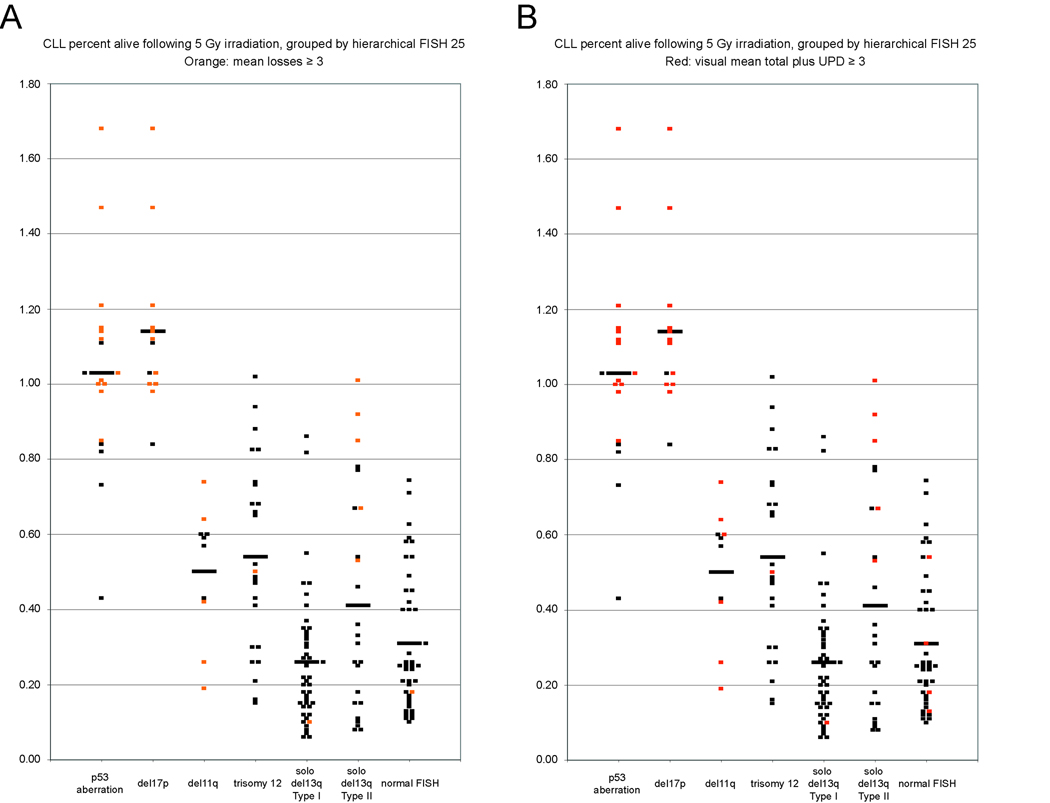

Based on unbiased measurements of subchromosomal lesion loads in CLL using 50K SNP-arrays (derived from pairwise analysis of CD19+ cells and paired buccal DNA), we had previously defined acquired genomic complexity in CLL as the sum of all subchromosomal losses (loss complexity) or the sum of subchromosomal losses, gains and UPD (total complexity) per CLL case, respectively(6). Given that molecular defects in genes involved in DNA-ds-break response and repair pathways are likely candidates for causing genomic complexity, we used external radiation to introduce DNA-ds-breaks into CLL cells from 158 patients and measured the cellular apoptotic response to radiation ~40–44h after the radiation insult. Data are summarized in Figure 1 with the normalized fraction of cells alive after radiation plotted against hierarchical CLL FISH data (all genomic categories other than p53 aberrant or del17p are p53 wildtype. Further, all del17p cases depicted were p53 aberrant, while a few p53 aberrant cases either lacked del17p or carried aUPD at 17p that is not detectable through FISH).

Figure 1. Measurements of the apoptotic response of CLL cells to radiation and the association with elevated genomic complexity.

Highly enriched CD19+ cells from 158 CLL patients were irradiated with 5Gy and the viable and apoptotic/necrotic cell populations measured for irradiated and non-irradiated samples using annexin V-PI FACS staining ~40 hours postirradiation. Each dot represents the mean normalized fraction of duplicate measurements of cells alive (%alive = % alive irradiated samples/% alive paired non-irradiated samples) for individual CLL samples categorized by hierarchical FISH (all depicted genomic categories other than p53 aberrant or del17p are p53 wild type). Colored dots represent cases with genomic complexity ≥3 lesions. Horizontal bars represent the mean of values within each genomic category. Panel A: loss complexity. Panel B: total complexity.

As can be seen in Figure 1, CLL cells from patients with either del17p or p53 aberrations (see methods) were resistant to radiation-induced apoptosis (mean normalized fraction of cells alive post-irradiation of 1.14 and 1.03, respectively), confirming the essential role that p53 serves in the apoptotic response to radiation-induced DNA-ds-breaks and providing confidence in our analytical conditions. Similar analysis for CLL cells with del11q, trisomy 12 or del13q14 type II identified intermediate radiation sensitivity (mean normalized fraction of cells alive post-irradiation of 0.5, 0.54 and 0.41, respectively) and analysis for isolated del13q14 type I or normal FISH identified substantial radiation sensitivity (mean normalized fraction of cells alive post-irradiation of 0.26 and 0.31, respectively). Compared with the CLL cases with isolated del13q14 type I, all genomic CLL categories, except for normal FISH, displayed highly significant radiation resistance. Interestingly, in addition to the CLL with del17p or p53 aberrations, each of the other five FISH-based CLL categories encompassed multiple cases that demonstrated profound radiation resistance even in the absence of p53 aberrations. Thus significant defects in the apoptotic response to DNA-ds-breaks other than p53 are present in a substantial fraction of CLL.

Next, we highlighted the subset of CLL cases with genomic complexity ≥3 lesions within the radiation resistance/sensitivity plots (Figure 1); Most CLL cases with elevated complexity and del17p/p53 aberrations or del13q14 type II were characterized by substantial or complete radiation resistance. Sporadic CLL cases with elevated genomic complexity in all other FISH categories (including del11q) demonstrated either partial radiation resistance or relative radiation sensitivity. Further, CLL cases with trisomy 12, isolated del13q14 type I or normal FISH were only rarely associated with elevated complexity. Finally, CLL cases with trisomy 12, despite being associated with substantial resistance to radiation-induced apoptosis, did not display genomic complexity, thus indicating that defects in radiation-induced apoptosis are heterogeneous and that some defects are not sufficient to cause unstable genomes in CLL.

Radiation resistance identifies aggressive CLL

Next we analyzed the prognostic effect of ex vivo radiation resistance on clinical outcome variables in CLL within the above-mentioned set of 158 CLL cases. Further, we separately analyzed the cases within this group that had wild type p53 (N=139) as defined above.

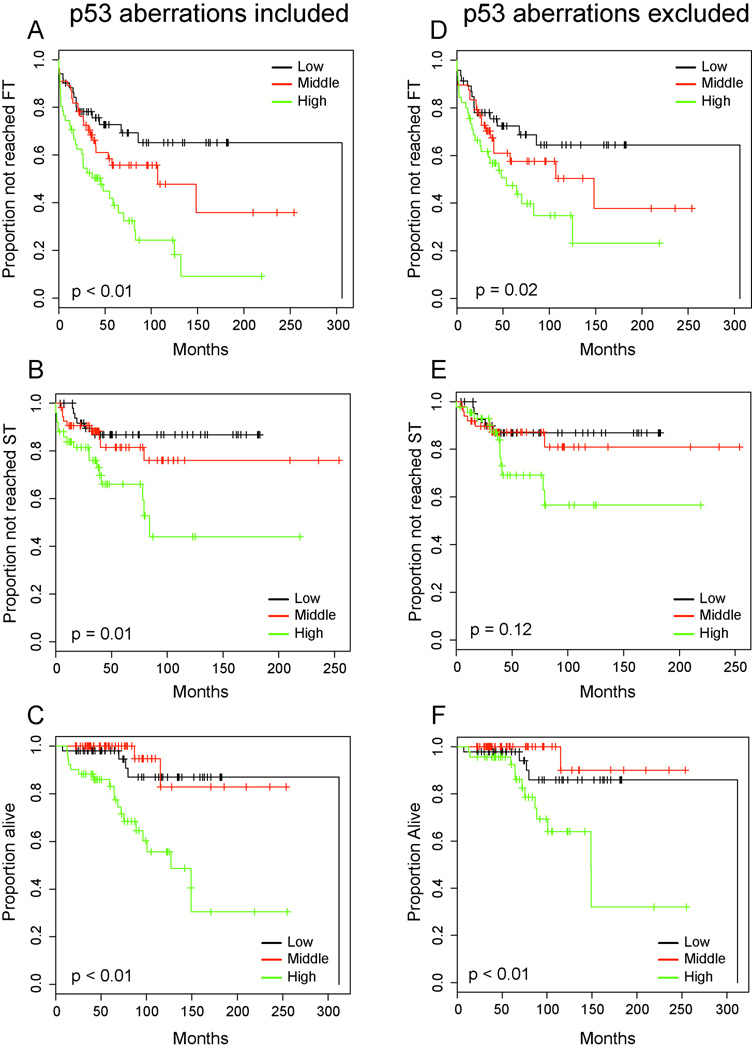

As can be seen in Figure 2A–F, ex vivo radiation resistance was an excellent predictor of aggressive CLL with shortened TTFT, TTST and OS when comparing three equal sized groups of CLL cases characterized by the lowest, intermediate or highest radiation resistance. Importantly, this remained true for the cohort that excluded p53 aberrations (Figure 2D–F).

Figure 2. Ex vivo radiation resistance of CLL cells predicts for progressive and aggressive CLL (Kaplan-Meier plots).

CLL cases analyzed were grouped by tertiles. Panel A–C: N=158 inclusive of p53 aberrations, Panel D–F: N=139 exclusive of p53 aberrations. Panel A,D: TTFT estimates, Panel B,E: TTST estimates, Panel C,F: Overall survival. High: Highest radiation resistance.

CLL cases with elevated genomic complexity are identified across the spectrum of FISH-defined genomic subtypes

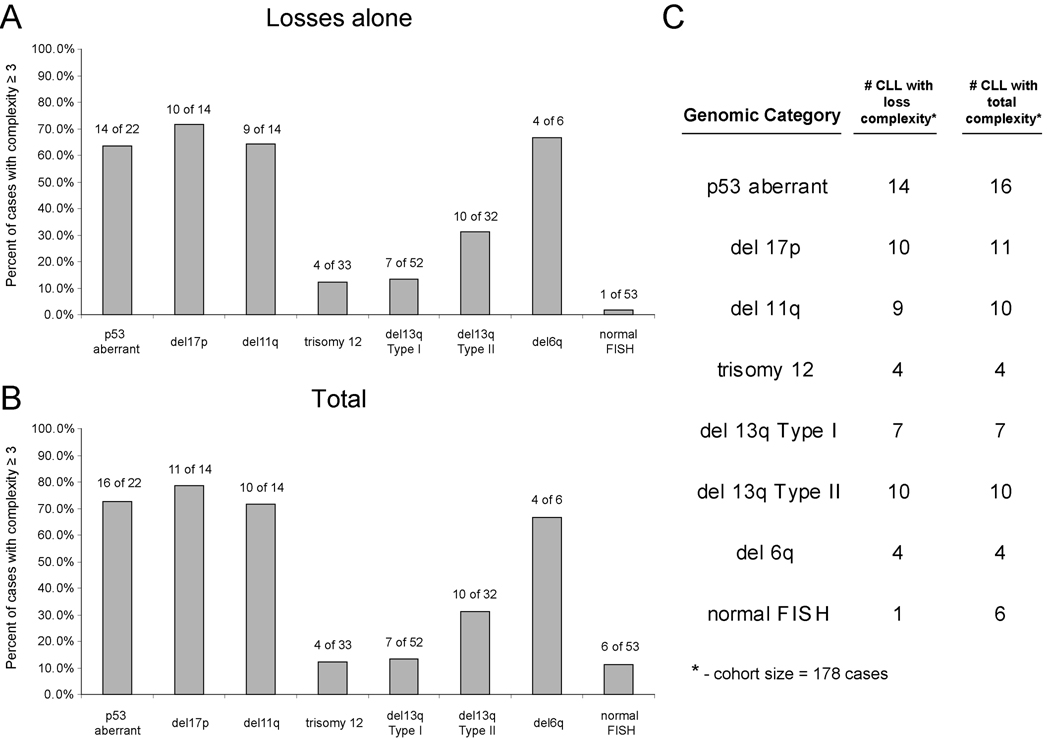

We analyzed the occurrence of elevated genomic complexity ≥3 lesions in all FISH25-defined genomic subgroups in our cohort of 178 CLL. As can be seen in Figure 3A–C, various genomic CLL subgroups (del17p/p53 aberrations, del11q, del13q14 type II and del6q) were characterized by a high proportion of cases with elevated complexity while conversely, CLL with trisomy 12, del13q14 type I or normal FISH were infrequently complex.

Figure 3. Elevated genomic complexity and relationship to CLL FISH categories.

Panel A–B: Frequency of elevated genomic complexity based on losses or total complexity in various genomic CLL categories. Panel C: Absolute number of CLL cases with specific genomic abnormalities and elevated genomic complexity out of a total of 178 patients (all non-hierarchical FISH 25 based).

Next we analyzed the sensitivity and specificity of a FISH result with ≥2 lesions (e.g. del17p/del13q14) for genomic complexity at either ≥2 or ≥3 lesions for both complexity based on losses or total complexity (FISH ≥3 had an incidence of only 2% in this cohort). As summarized in Supplementary Table 2, FISH ≥2 lesions was not sensitive (~45–50%) but quite specific (~90%) for genomic complexity.

Identification of predictors of genomic complexity in CLL using univariate analysis

Next we wished to determine the importance of various biomarkers, including the apoptotic response of CLL cells to radiation, as predictors of genomic complexity in CLL. Genomic complexity was dichotomized into <3 or ≥3 lesions, a cut-off that had previously allowed for the identification of a subset of CLL with aggressive disease. For the following univariate and multi variate analysis, none of the variables were subjected to a hierarchical model.

In univariate analysis, multiple factors emerged as significant predictors of genomic complexity in CLL (see Supplementary Table 3). For instance, in the analysis using complexity at ≥3 losses, p53 aberrations (OR=17.75, p<0.001), del17p (OR=23.62, p<0.0001), del11q (OR=7.42, p<0.0001), del6q (OR=12.33, p=0.005), the fraction of cells alive post-irradiation (OR=8.62 for any 50% increment in cells alive [for instance 75% alive versus 25% alive], p<0.0001), IgVH unmutated (OR=4.38, p=0.002), CD38 (OR=3.44, p=0.005), del13q14 type II (OR=2.92, p=0.018), ZAP70 (OR=3.92, p=0.003), and lower Rb mRNA levels (coded quantitatively with lower Rb mRNA levels reflected in higher delta Ct Rb-PGK1 levels and higher odds ratios for complexity) emerged as predictive factors. If only FISH25 results were considered, the corresponding results were: del17-FISH25 (OR=20.28, p<0.0001), del11q-FISH25 (OR=11.6, p<0.0001) and del6q FISH-25 (OR=12.33, p=0.005). The MDM2 SNP 309 allele status (TT versus either T/G or GG) and del13q14 type I did not emerge as significant risk factors(33). Presence of trisomy 12 or normal FISH was negatively associated with genomic complexity.

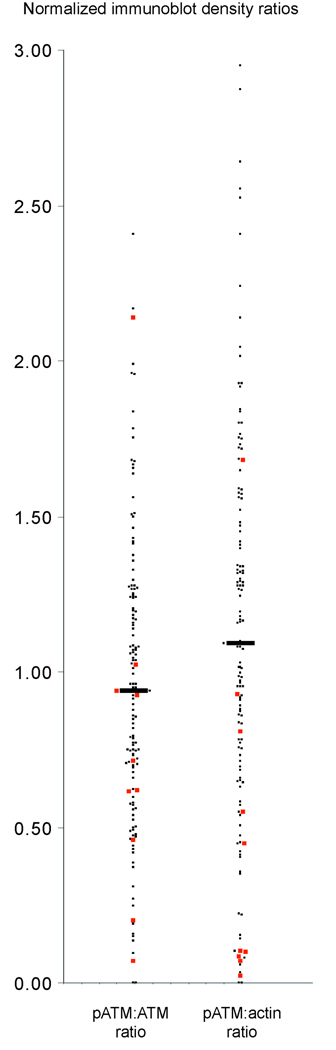

ATM activity is a modestly strong predictor of genomic complexity in CLL in univariate analysis

Given the strong effect of del11q on genomic complexity in CLL and the reported association of del11q with ATM mutations/dysfunction, we proceeded with measurements of normalized ATM activity in all studied CLL cases for which sufficient cryopreserved cells were available (N=141). ATM autophosphorylation on Ser-1981 was measured 20 minutes after 5 Gy of radiation and was normalized on each immunoblot to internal standards and subsequently to normalized levels of total ATM or actin. Normalization to both total ATM and actin, allowed further separation of ATM hypoactivity due to low ATM expression (p-ATM/ATM preserved, p-ATM/actin low) or dysfunctional ATM (p-ATM/ATM and p-ATM/actin both low). Representative immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Mean and median p-ATM/ATM and p-ATM/actin ratios were 0.93/0.92 and 1.13/1.08, respectively, with a range of measurements of 0.0 to 2.41 and 0.0 to 2.95, respectively. Of these measurements, 117/141=83% and 116/141=82% of p-ATM/ATM and p-ATM/actin ratios fell between 0.5 and 2 and 24/141=17% and 25/141=18% of p-ATM/ATM and p-ATM/actin ratios were <0.5. Furthermore, inspection of displays of p-ATM/ATM and p-ATM/actin ratios as in Figure 4, suggested ATM function in CLL to be a continuous variable without overt clustering, except for a small subset of CLL cases demonstrating profound loss of ATM activity and/or protein (only 8/141=6% and 14/141=10% of p-ATM/ATM and p-ATM/actin ratios were <0.2). Finally, of 10 CLL cases with del11q and available measurements, five had p-ATM/actin ratios of <0.1, providing additional confidence in our assay conditions.

Figure 4. ATM displays a continuum of activities across a large CLL cohort.

Highly enriched CD19+ cells from 141 CLL patients were rradiated with 5Gy and cellular lysates prepared after 20 minutes for immunoblotting with antibodies to ATM-ser-1981, ATM and actin. Band intensities were quantified and normalized against internal standards run on each gel (see methods). Displayed are normalized phospho-ATM/total ATM and phospho-ATM/actin ratios, respectively. CLL cases with del11q are indicated in red.

Next, we determined the predictive effect of p-ATM/ATM and p-ATM/actin ratios on genomic complexity in CLL using these ratios as a continuous variable. Using univariate analysis, low p-ATM/ATM and p-ATM/actin ratios demonstrated a modest predictive effect on genomic complexity (p-ATM/ATM OR=2.87, p=0.057 and p-ATM/actin OR=2.69, p=0.019 for ≥3 versus <3 losses and p-ATM/ATM OR=2.92, p=0.036 and p-ATM/actin OR=2.10, p=0.043 for ≥3 versus <3 total lesions) for any absolute decrease in the ratios of 1 (for instance, p-ATM/ATM ratios of 1.6 and 0.6, respectively).

ATM activity is not a predictor of outcome in CLL

We analyzed the effect of p-ATM/ATM and p-ATM/actin ratios in three equal sized groups of CLL (lowest, intermediate and highest ATM activity) on the outcome variables TTFT, TTST and OS in the cohort of cases with available measurements. As depicted in Supplementary Figures 2A–F, ATM activity was not a significant prognostic variable in CLL.

Del17p/p53 aberrations, del11q, del13q14 type II and CD38 expression are independent predictors of genomic complexity in CLL (multivariate analysis)

We proceeded with multivariate analysis to identify dependent and independent predictors of genomic complexity in CLL and included the following variables in parallel Cox-proportional hazard models: CD38, ZAP70, IgVH-status, del13q14 type II, del11q and alternatively either del17p, p53 aberrations or the fractions of cells alive post-irradiation as the latter three variables are directly linked mechanistically through p53. Data are summarized in Table 1, grouped by results for loss complexity (upper panels) and total complexity (lower panels).

Table 1.

Multivariate analysis results of the odds ratio of various markers/biomarkers as predictors of genomic complexity. Values for % cells alive post irradiation are for samples with any 50% absolute change in normalized viability. None of the variables included in the models were subjected to a hierarchical classification.

| Loss complexity ≥3 lesions |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarker/Variable N=172 | Odds ratio |

P-value | Biomarker/ Variable N=172 |

Odds ratio | P-value | Biomarker/ Variable N=156 |

Odds ratio |

P-value |

| P53 status | 21.64 | <0.01 | Del17p | 26.63 | <0.01 | Cells % alive post-irradiation | 7.02 | <0.01 |

| Del11q | 7.27 | 0.01 | Del11q | 5.66 | 0.01 | Del11q | 3.26 | 0.1 |

| Del13q14 type II | 6.93 | <0.01 | Del13q14 type II | 7.76 | <0.01 | Del13q14 type II | 4.16 | 0.04 |

| CD38 positive | 3.77 | 0.03 | CD38 positive | 3.55 | 0.04 | CD38 positive | 3.02 | 0.09 |

| IgVH unmutated | 1.46 | 0.6 | IgVH unmutated | 1.67 | 0.58 | IgVH unmutated | 1.79 | 0.45 |

| ZAP70 positive | 1.83 | 0.39 | ZAP70 positive | 1.25 | 0.74 | ZAP70 positive | 1.05 | 0.95 |

| Total complexity ≥3 lesions |

||||||||

| Biomarker/ Variable N=172 |

Odds ratio |

P-value | Biomarker/ Variable N=172 |

Odds ratio | P-value | Biomarker/ Variable N=156 |

Odds ratio |

P-value |

| P53 status | 19.55 | <0.01 | Del17p | 20.98 | <0.01 | Cells % alive post-irradiation | 5.69 | <0.01 |

| Del11q | 6.3 | <0.01 | Del11q | 5.02 | 0.01 | Del11q | 3.38 | 0.07 |

| Del13q14 type II | 3.06 | 0.05 | Del13q14 type II | 3.36 | 0.03 | Del13q14 type II | 2.39 | 0.17 |

| CD38 positive | 2.41 | 0.1 | CD38 positive | 2.27 | 0.12 | CD38 positive | 2.23 | 0.16 |

| IgVH unmutated | 1.45 | 0.54 | IgVH unmutated | 1.58 | 0.43 | IgVH unmutated | 1.93 | 0.34 |

| ZAP70 positive | 1.62 | 0.42 | ZAP70 positive | 1.2 | 0.75 | ZAP70 positive | 1.28 | 0.72 |

From these models, we identified p53 aberrations/del17p, del11q and del13q14 type II as strong independent predictors of elevated genomic complexity in CLL. In models including the variable % cells alive post-irradiation, del11q lost independence, consistent with the notion that the del11q effect is linked to a defective response to DNA double-strand breaks. Furthermore, CD38 expression in >30% of CLL cells was an independent complexity predictor, while ZAP70 expression and IgVH status were not.

Next, we added the variables p-ATM/ATM or p-ATM/Actin into the models. Data are summarized in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5. From these models it became clear that ATM activity was not independent of del11q, thus providing novel evidence for del11q-associated genes other than or in addition to ATM that confer genomic complexity on CLL cells.

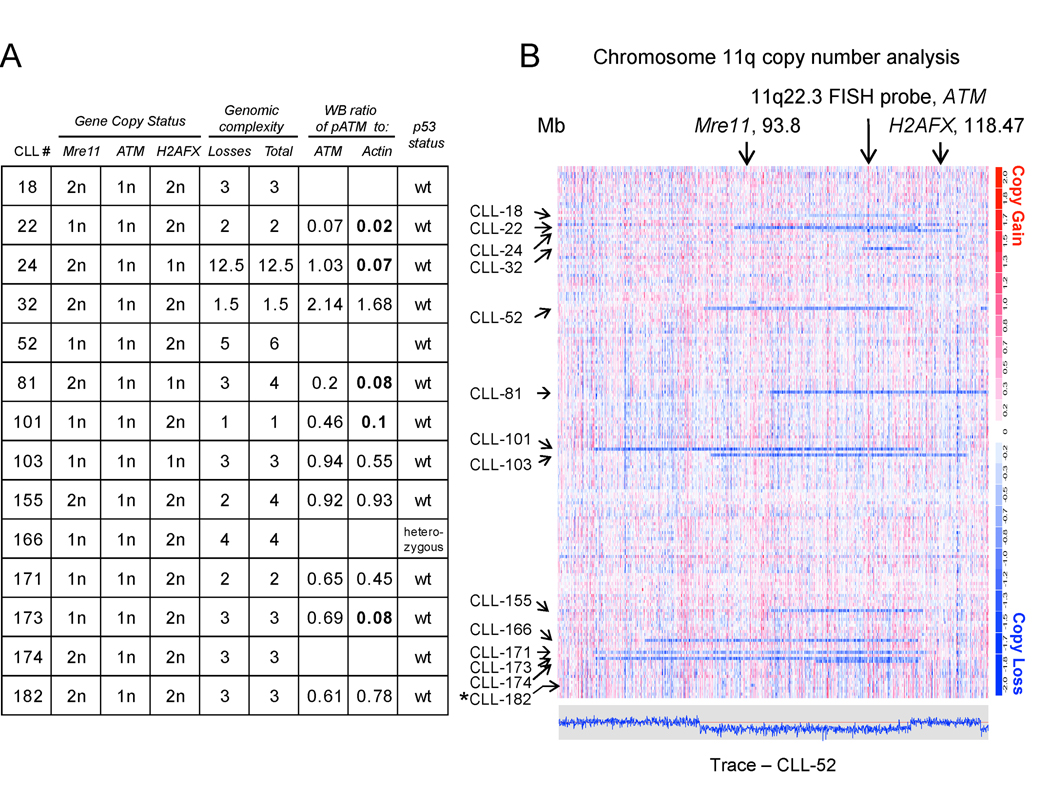

Del11q frequently results in mono-allelic deletions of Mre11 or H2AFX in addition to invariate mono-allelic ATM deletion

Most CLL cases with del11q had elevated genomic complexity but this was not strictly dependent on absent ATM activity. For instance, of the 10 CLL cases with del11q and available measurement of ATM activity and wt p53, 3/5 cases with complete loss of ATM activity had elevated genomic complexity, as opposed to 3/5 cases with essentially normal ATM activity (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Deletion 11q in CLL affects multiple critical genes involved in the response to double-strand DNA breaks.

High-resolution mapping of del11q in CLL using 50K SNP-arrays (CLL1-186). Copy number estimates for all SNP positions for all patients were generated through dChipSNP as described and are displayed across the length of the chromosomes. Copy losses are displayed with blue colors, copy gains with red colors. Fig. 5A, gene copy number status for Mre11, ATM and H2AFX and genomic complexity scores as measured through 50KSNP arrays, normalized p-ATM/ATM and p-ATM/actin ratios and p53 aberrancy status. Fig. 5B. genomic copy number display for a region of chromosome 11. The estimated copy numbers for all SNP positions for CLL # 52 are displayed along the chromosome below the chromosome 11 display, with the red line indicating the 2N state. Arrows mark the position of Mre11, ATM and H2AFX. CLL#182 has a del11q that is not readily visible at this resolution.

We therefore reviewed the anatomy of del11q as defined through SNP-array profiling of 232 CLL cases for additional complexity-causing candidate genes. Overall, SNP-array analysis detected 22/232 cases with del11q that spanned ATM. Of these, 22/22=100% resulted in loss of one copy of ATM, 11/22=50% included Mre11 and 4/22=18% included H2AFX and 14/22=64% cases including either Mre11 or H2AFX or both together with ATM loss (see Figure 5). Therefore, multiple genes with important roles in the response pathways activated by DNA-ds-breaks are mono-allelically co-deleted through del11q in the majority of CLL cases.

Next, we measured normalized Mre11a expression in RNA from FACS sorted CD19+ cells (N=220 CLL cases) and grouped resulting normalized values according to del11q status and Mre11a status. As can be seen in Supplementary Figure 3A, Mre11a mRNA levels were substantially and significantly lower in CLL with del11q that was inclusive of Mre11a than in CLL with del11q exclusive of Mre11a or all other non-del11q CLL cases.

To obtain additional evidence in support of a contributing role of Mre11a in del11q biology and genomic complexity in CLL, we sequenced all coding exons of Mre11a in all CLL that carried del11q and mono-allelic Mre11a loss (N=11). We identified two CLL cases with Mre11a nucleotide changes as a consequence of LOH at non-synonymous SNPs that predicted for amino acid changes in Mre11a (Supplementary Figure 3B) although effects of these changes on Mre11a remain undefined.

Sequencing of the H2AFX coding exon did not disclose mutations and too few cases had H2AFX +/− status to reliably detect mRNA expression differences. No case was found not to express H2AFX.

DISCUSSION

Genomic instability and elevated genomic complexity have been linked to poor outcome in multiple types of cancer(34, 35). In CLL, elevated genomic complexity exists in 15–30% of previously untreated patients and has identified a substantial disease subset with an aggressive disease course(6). It therefore appeared important to establish a link between the identification of aggressive CLL, molecular defects in the DNA-ds-break response and unbiased assessments of genomic complexity in CLL, all in the setting of prevailing therapies with genotoxic drugs as reported here for a large CLL cohort.

Using radiation as a relatively selective modality to introduce DNA double strand breaks into CLL cells, we confirmed that a substantial subset of CLL displays relative or absolute radiation resistance; this in the setting of p53 aberrations, as expected, as well as in CLL cases with wild type p53(36–38). Given our prior findings of general sensitivity of CLL with wild type p53 to p53-induced apoptosis following treatment with Nutlin3-type MDM2 inhibitors, together, this data provides evidence for proximal defects in CLL in the signaling cascade that originates with DNA breaks and culminates in p53 activation. Additionally, and not further investigated in this study, CLL with wild type p53 and radiation resistance may have elevated activity of NHEJ-pathways that repair DNA damage prior to the execution of p53-dependent apoptosis, thus potentially contributing to the observed radiation resistance(39).

Using multivariate analysis, we found that resistance to radiation-induced apoptosis was a very strong independent predictor of genomic complexity in CLL, thus directly linking defective apoptotic DNA-ds-break response with genomic complexity and aggressive CLL. Further, we report for the first time a strong negative effect of impaired radiation-induced apoptosis on survival in CLL even in a subset of cases with wild type p53.

Data presented here provide evidence for a strong effect of p53 aberrations on genomic complexity in CLL. This therefore corroborates findings of the negative prognostic impact of del17p (always associated with p53 aberrations) or rare isolated p53 mutations on CLL and explains why unbiased genomic complexity assessments completely capture the risk imparted on CLL through del17p(1, 6, 40). Our data furthermore identify del11q and the recently identified del13q14 type II deletions (Rb loss) as independent predictors of genomic complexity in CLL, providing independent evidence for the existence of additional defects in genes with effects on genomic stability in CLL.

Attempting to deconvolute the effect of del11q on genomic complexity, we measured ATM activity through ATM autophosphorylation postirradiation in ~140 CLL cases(41). To our knowledge, such an unbiased, comprehensive assessment of ATM activity in CLL has not been previously performed. Measuring ATM activity as a variable in our genomic complexity analysis, rather than ATM mutations, appeared to be a more direct and specific way of interrogating ATM dysfunction as i) the effect of individual mutations in large proteins are not always readily predictable, and ii) mutations and hypofunction in ATM can be dissociate. Multiple interesting findings emerged: i) true functional ATM null states are rare in CLL, as suggested in prior studies(11), ii) ATM kinase displayed a continuum of activities across this large CLL cohort rather than discrete activity clusters, as exists for p53 (wild type versus aberrant), iii) importantly, reduced ATM activity alone did not account for the effects of del11q on genomic complexity in CLL, iv) ATM activity, across the entire CLL cohort, was a modest predictor of genomic complexity and not independent of other dominant predictive factors as outlined above and v) ATM activity was not prognostic for CLL outcome. Together, these data based on a large CLL cohort are consistent with prior observations that mono-allelic ATM states are sufficient to support a functional response to DNA-ds-breaks(11, 42). What remains unclear from this analysis is a mechanism for the reported moderately negative prognostic impact of ATM mutations in CLL, given our observation reported here that ATM hypoactivity appears to be only a minor contributor to genomic complexity in CLL and not predictive of outcome in CLL. One hypothesis is that a negative prognostic ATM effect is mostly driven by rare CLL cases with complete loss of ATM activity as suggested(10) (which were rare in this cohort), or by compound defects in multiple closely linked pathogenetic genes on 11q as analyzed in this report (in the setting of low ATR expression)(43). Finally, it remains formally possible that ATM autophosphorylation does not measure all critical ATM functions that are important to CLL biology.

Through analysis of precise boundaries of the deleted genomic regions as part of various interstitial 11q deletions, we quantify for the first time frequent loss of either Mre11 or H2AFX in addition to invariate loss of ATM through del11q in CLL. Given data from mouse models indicating effects on genomic instability of each of these genes (although not yet fully explored in the case of Mre11a single copy loss), and data for strong synergistic effects on genomic instability of combined ATM and H2AFX defects, we surmise that del11q affects genomic stability in CLL through compound defects in genes important to genomic stability(44–47). These data therefore offer a possible explanation for the observed imperfect correlation between p53 dysfunction and ATM mutation rates in patients with del11q(48).

In this study we have identified for the first time an independent contribution of del13q14 type II lesions on genomic complexity in CLL. Recent data have suggested the existence of del13q14 subtypes, initially categorized as del13q14 type I (exclusive of Rb) and del13q14 type II (inclusive of Rb)(32). Given the known effect of Rb null states on genomic instability in mouse models(49), Rb emerges as a candidate gene for genomic complexity in CLL and we note that i) lower Rb mRNA levels were predictive of genomic complexity in CLL in univariate analysis(49), ii) that del13q14 type II lesions are associated with ~2.5-fold lower Rb mRNA levels than all other CLL cases, and iii) that lower Rb mRNA levels were weak (OR ~1.5) but independent predictors of genomic complexity in models that did not include del13q14 type II lesions.

While multiple other markers were predictors of genomic complexity in univariate analysis, only CD38 expression retained independent value in multivariate models. Given that a CD38 polymorphisms and presumably increased CD38 expression has recently been linked to CLL transformation to large cell lymphoma (Richter’s transformation) it will be interesting to determine whether elevated genomic complexity constitutes a risk factor for transformation as well(50).

In summary, our data provide solid support to the hypothesis that an impaired DNA-ds-break response due to multiple gene defects on multiple chromosomes is a major contributor to elevated genomic complexity in CLL, thus adding additional justification for the introduction of this novel biomarker into clinical practice and for the development of therapies not reliant on genotoxicity.

Translational Relevance

CLL has a varied clinical course. The identification of genomic markers that predict for CLL survival has motivated interests in genomic predictors of outcome. Genomic complexity that exists in 15–30% of untreated CLL patients is a strong independent negative prognostic marker in CLL. In this manuscript, we have comprehensively analyzed genomic complexity determinants and results from this work further strengthen the concept of impaired DNA-ds-break response/repair pathways in CLL and further, identify genomic complexity as the product of multiple gene alterations in CLL. This data further motivate development of diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to incorporate this knowledge into CLL clinical care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health through 1 R21 CA124420-01A1 (SM) and 1R01 CA136537-01 (SM). Supported through the translational research program of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America (SM). This research is supported (in part) by the National Institutes of Health through the University of Michigan's Cancer Center Support Grant (5 P30 CA46592). We are grateful for services provided by the microarray core of the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Individual contributions

Peter Ouillette, Sam Fossum, Li Ding and Sami Malek performed the laboratory research. Kerby Shedden assisted with statistical methods.

Paula Bockenstedt, Ammar Al-Zoubi, Brian Parkin and Sami Malek enrolled patients and analyzed clinical data.

Sami Malek conceived the study and Peter Ouillette and Sami Malek wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1910–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shanafelt TD, Witzig TE, Fink SR, et al. Prospective evaluation of clonal evolution during long-term follow-up of patients with untreated early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4634–4641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grever MR, Lucas DM, Dewald GW, et al. Comprehensive assessment of genetic and molecular features predicting outcome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from the US Intergroup Phase III Trial E2997. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:799–804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayr C, Speicher MR, Kofler DM, et al. Chromosomal translocations are associated with poor prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:742–751. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanafelt TD, Hanson C, Dewald GW, et al. Karyotype evolution on fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis is associated with short survival in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is related to CD49d expression. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:e5–e6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.7874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kujawski L, Ouillette P, Erba H, et al. Genomic complexity identifies patients with aggressive chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:1993–2003. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Den Neste E, Robin V, Francart J, et al. Chromosomal translocations independently predict treatment failure, treatment-free survival and overall survival in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with cladribine. Leukemia. 2007;21:1715–1722. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haferlach C, Dicker F, Schnittger S, Kern W, Haferlach T. Comprehensive genetic characterization of CLL: a study on 506 cases analysed with chromosome banding analysis, interphase FISH, IgV(H) status and immunophenotyping. Leukemia. 2007;21:2442–2451. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dicker F, Schnittger S, Haferlach T, Kern W, Schoch C. Immunostimulatory oligonucleotide-induced metaphase cytogenetics detect chromosomal aberrations in 80% of CLL patients: A study of 132 CLL cases with correlation to FISH, IgVH status, and CD38 expression. Blood. 2006;108:3152–3160. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austen B, Skowronska A, Baker C, et al. Mutation Status of the Residual ATM Allele Is an Important Determinant of the Cellular Response to Chemotherapy and Survival in Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Containing an 11q Deletion. J Clin Oncol. 2007 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austen B, Powell JE, Alvi A, et al. Mutations in the ATM gene lead to impaired overall and treatment-free survival that is independent of IGVH mutation status in patients with B-CLL. Blood. 2005;106:3175–3182. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saddler C, Ouillette P, Kujawski L, et al. Comprehensive biomarker and genomic analysis identifies p53 status as the major determinant of response to MDM2 inhibitors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:1584–1593. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zenz T, Krober A, Scherer K, et al. Monoallelic TP53 inactivation is associated with poor prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from a detailed genetic characterization with long-term follow-up. Blood. 2008;112:3322–3329. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-154070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dicker F, Herholz H, Schnittger S, et al. The detection of TP53 mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia independently predicts rapid disease progression and is highly correlated with a complex aberrant karyotype. Leukemia. 2009;23:117–124. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starostik P, Manshouri T, O'Brien S, et al. Deficiency of the ATM protein expression defines an aggressive subgroup of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4552–4557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenwald A, Chuang EY, Davis RE, et al. Fludarabine treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia induces a p53-dependent gene expression response. Blood. 2004;104:1428–1434. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byrd JC, Lin TS, Dalton JT, et al. Flavopiridol administered using a pharmacologically derived schedule is associated with marked clinical efficacy in refractory, genetically high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:399–404. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-020735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvi AJ, Austen B, Weston VJ, et al. A novel CDK inhibitor, CYC202 (R-roscovitine), overcomes the defect in p53-dependent apoptosis in B-CLL by down-regulation of genes involved in transcription regulation and survival. Blood. 2005;105:4484–4491. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamblin TJ, Davis Z, Gardiner A, Oscier DG, Stevenson FK. Unmutated Ig V(H) genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1848–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Damle RN, Wasil T, Fais F, et al. Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1840–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiestner A, Rosenwald A, Barry TS, et al. ZAP-70 expression identifies a chronic lymphocytic leukemia subtype with unmutated immunoglobulin genes, inferior clinical outcome, and distinct gene expression profile. Blood. 2003;101:4944–4951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rassenti LZ, Huynh L, Toy TL, et al. ZAP-70 compared with immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene mutation status as a predictor of disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:893–901. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Del Poeta G, Maurillo L, Venditti A, et al. Clinical significance of CD38 expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2001;98:2633–2639. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibrahim S, Keating M, Do KA, et al. CD38 expression as an important prognostic factor in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2001;98:181–186. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, Widhopf G, Huynh L, et al. Expression of ZAP-70 is associated with increased B-cell receptor signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:4609–4614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krober A, Seiler T, Benner A, et al. V(H) mutation status, CD38 expression level, genomic aberrations, and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:1410–1416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin K, Sherrington PD, Dennis M, Matrai Z, Cawley JC, Pettitt AR. Relationship between p53 dysfunction, CD38 expression, and IgV(H) mutation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:1404–1409. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oscier DG, Gardiner AC, Mould SJ, et al. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in CLL: clinical stage, IGVH gene mutational status, and loss or mutation of the p53 gene are independent prognostic factors. Blood. 2002;100:1177–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crespo M, Bosch F, Villamor N, et al. ZAP-70 expression as a surrogate for immunoglobulin-variable-region mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1764–1775. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa023143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orchard JA, Ibbotson RE, Davis Z, et al. ZAP-70 expression and prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Lancet. 2004;363:105–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lavin MF. ATM and the Mre11 complex combine to recognize and signal DNA double-strand breaks. Oncogene. 2007;26:7749–7758. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouillette P, Erba H, Kujawski L, Kaminski M, Shedden K, Malek SN. Integrated genomic profiling of chronic lymphocytic leukemia identifies subtypes of deletion 13q14. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1012–1021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bond GL, Hu W, Bond EE, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 promoter attenuates the p53 tumor suppressor pathway and accelerates tumor formation in humans. Cell. 2004;119:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Kern SE, et al. Science. Vol. 244. New York, NY: 1989. Allelotype of colorectal carcinomas; pp. 207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carter SL, Eklund AC, Kohane IS, Harris LN, Szallasi Z. A signature of chromosomal instability inferred from gene expression profiles predicts clinical outcome in multiple human cancers.[see comment] Nature Genetics. 2006;38:1043–1048. doi: 10.1038/ng1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pettitt AR, Sherrington PD, Stewart G, Cawley JC, Taylor AM, Stankovic T. p53 dysfunction in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: inactivation of ATM as an alternative to TP53 mutation. Blood. 2001;98:814–822. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blaise R, Alapetite C, Masdehors P, et al. High levels of chromosome aberrations correlate with impaired in vitro radiation-induced apoptosis and DNA repair in human B-chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 2002;78:671–679. doi: 10.1080/09553000110120364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salin H, Ricoul M, Morat L, Sabatier L. Increased genomic alteration complexity and telomere shortening in B-CLL cells resistant to radiation-induced apoptosis. Cytogenetic and genome research. 2008;122:343–349. doi: 10.1159/000167821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deriano L, Guipaud O, Merle-Beral H, et al. Human chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells can escape DNA damage-induced apoptosis through the non-homologous end-joining DNA repair pathway. Blood. 2005 doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wattel E, Preudhomme C, Hecquet B, et al. p53 mutations are associated with resistance to chemotherapy and short survival in hematologic malignancies. Blood. 1994;84:3148–3157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cejkova S, Rocnova L, Potesil D, et al. Presence of heterozygous ATM deletion may not be critical in the primary response of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells to fludarabine. European journal of haematology. 2009;82:133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2008.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones GG, Reaper PM, Pettitt AR, Sherrington PD. The ATR-p53 pathway is suppressed in noncycling normal and malignant lymphocytes. Oncogene. 2004;23:1911–1921. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buis J, Wu Y, Deng Y, et al. Mre11 nuclease activity has essential roles in DNA repair and genomic stability distinct from ATM activation. Cell. 2008;135:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zha S, Sekiguchi J, Brush JW, Bassing CH, Alt FW. Complementary functions of ATM and H2AX in development and suppression of genomic instability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9302–9306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803520105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Callen E, Jankovic M, Difilippantonio S, et al. ATM prevents the persistence and propagation of chromosome breaks in lymphocytes. Cell. 2007;130:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bassing CH, Suh H, Ferguson DO, et al. Histone H2AX: a dosage-dependent suppressor of oncogenic translocations and tumors. Cell. 2003;114:359–370. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carter A, Lin K, Sherrington PD, et al. Imperfect correlation between p53 dysfunction and deletion of TP53 and ATM in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:737–740. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hernando E, Nahle Z, Juan G, et al. Rb inactivation promotes genomic instability by uncoupling cell cycle progression from mitotic control. Nature. 2004;430:797–802. doi: 10.1038/nature02820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aydin S, Rossi D, Bergui L, et al. CD38 gene polymorphism and chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a role in transformation to Richter syndrome? Blood. 2008;111:5646–5653. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-129726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.