Abstract

We examined potential neurocognitive mechanisms of indirect speech in support of face management in 28 patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) and 32 elderly controls with chronic disease. In experiment 1, we demonstrated automatic activation of indirect meanings of particularized implicatures in controls but not in PD patients. Failure to automatically engage comprehension of indirect meanings of indirect speech acts in PD patients was correlated with a measure of prefrontal dysfunction. In experiment 2, we showed that while PD patients and controls offered similar interpretations of indirect speech acts, PD participants were overly confident in their interpretations and unaware of errors of interpretation. Efficient reputational adjustment mechanisms apparently require intact striatal-prefrontal networks.

Keywords: evolution of cooperation, reputation, indirect speech, politeness conventions, face-saving, Parkinson's disease

1. Introduction

Innuendo, insinuation, politeness and other forms of indirect speech appear to be universally practiced across cultures (Brown & Levinson, 1987). In their theory of the functions of indirect speech, Pinker, Nowak and Lee (2008) emphasized that indirect speech allows for `plausible deniability” if an uncooperative interlocutor might react adversarially to an indirect suggestion. With plausible deniability a message can be retracted (I didn't mean it that way!) without losing face. Pinker et al. also pointed out that plausible deniability might also be selected in cases where speaker and hearer are mis-matched in terms of social status or relationship. Pinker et al also argued that while direct speech can create common knowledge among groups of people, indirect speech can create `shared individual knowledge' between individuals who would like to maintain, via plausible deniability, a relationship despite a rejected indirect request or suggestion. In short, indirect speech may constitute a mechanism that allows for `plausible deniability' and the protection of one's own and another's reputation as a reliable cooperator. Indirect speech in this case would function as a face-saving device in service to reputation, which in turn, is crucial for development of cooperative social interactions.

One form of indirect speech that is known to be used in face-saving maneuvers are `particularized implicatures' (Grice, 1975). Particularized implicatures are indirect meanings that are dependent on the context for their recognition (in contrast to generalized implicatures – speech acts, for example - that can be recognized independent of a discourse context). In this research we examined the particularized implicatures conveyed with indirect replies, that is, replies that convey an indirect meaning by subtly violating the relevance maxim.

Previous research has demonstrated that nonimpaired participants generate particularized implicatures for these types of replies, and that they do so based on their reasoning about the operation of face management in the situation. Specifically, they interpret relevance violations as conveying face-threatening (i.e., negative) information (Holtgraves, 1998).

In this project, we assessed the extent to which patients with impairment in striatal-prefrontal neurocognitive networks, patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) were sensitive to face saving linguistic processing routines. We chose to study these issues in patients with PD as an independent literature has indicated that brain systems activated during social interaction (e.g. games of social cooperation) include the striatal prefrontal dopaminergic networks that are known to be impaired in patients with PD. Specifically a number of recent reports have identified an association between the decision to cooperate with others and striatal-prefrontal dopaminergic activity (Blakemore, Winston, & Frith, 2004; de Quervain et al., 2004; Fehr & Gachter, 2002; Fehr & Rockenbach, 2004). Thus, this patient population appears to be ideal for the study of the potential brain correlates of reputational and cooperative dynamics.

In Experiment 1, we tested the hypothesis that automatic activation of face-saving meanings occurs in non-impaired individuals in a face-threatening situation (consistent with past research) but not in patients with PD and striatal-prefrontal dysfunction.

2.1. Experiment 1

In this experiment, we used a sentence verification task similar to that used in Holtgraves (1999). Participants read scenarios and subsequent utterances and then performed a sentence verification task (decide whether a string of words is a sentence). On some trials the presented word string represented an indirect interpretation of the immediately prior utterance. For the nonimpaired participants we expected decisions to be faster for these target strings when they followed an indirect reply (because the indirect meaning had been activated) than when they followed a reply that should be interpreted directly. In contrast, because of the general pragmatic deficits associated with PD (see Holtgraves, McNamara, Cappert, & Durso, in review), we did not expect people with PD to show this effect.

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Participants

PD participants were 28 (2 female; 2 non-white) individuals diagnosed with idiopathic Parkinson's disease (M age = 66.5). The majority (> 90%) were either level two or three on the Hoehn and Yahr scale (M = 2.74). Most (93%) of the participants had completed high school with half (50%) having completed some college.

More advanced Stage III, IV, or V patients were excluded during the recruitment process. The patient's diagnosis was agreed upon by a specialist in PD (Dr. Durso) and at least one other neurologist. All patients were required to have had at least one CT- or MRI scan during their illness to rule out history of brain injury. Patients with Parkinsonism from known causes (e.g., encephalitis, trauma, carbon monoxide exposure, manganese poisoning, hypoparathyroidism, a multi-infarct state or medications (such as neuroleptics) interfering with dopaminergic functions) were excluded. Similarly, other degenerative diseases mimicking PD (e.g., striatonigral degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy or olivopontocerebellar degeneration) were excluded. PD patients with concurrent Alzheimer-like dementia were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included: 1) An abnormal CT or MRI scan showing basal ganglia atrophy or calcification and or stroke. 2) For patients who had received levodopa (LD) for more than 1 year, a history of no response to LD even in the initial stages of the disease, as this would be consistent with striatonigral degeneration rather than PD. 3) The presence of pyramidal, downward gaze or cerebellar dysfunction on examination, as these would be consistent with other diagnoses such as multi-infarct state, progressive supranuclear palsy or olivopontocerebellar degeneration respectively. 4) Other: (a) inability to obtain informed consent from patient due to an incapacity on the part of patient to understand purpose and risks of study, as these individuals are likely demented; (b) history of ongoing alcohol or drug abuse; (c) patients with a history of psychiatric or psychotic disorder and patients currently on anti-depressant or anti-psychotic medications as these medications may influence communication functions.

Medication information was obtained from each patient's records and levodopa equivalent dosages (LDE) were calculated with 100 mg levodopa=83 mg levodopa with a COMT inhibitor=1 mg Pramipexole=1 mg Pergolide. LDEs were later examined to assess the impact of medications on performance outcomes.

Nonimpaired participants were 32 (12 female; 7 non-white) individuals (M age = 56.3) recruited through the Movement Disorders Clinics of the VA New England Health Care System. All of these participants had completed high school with the majority (80%) having completed some college. Hence, relative to the PD participants, the control group had more females (37.5 % vs. 7.1%, χ2 = 7.69, p < .05), was younger (56.3 vs. 66.5, t(58) = −3.74, p < .05), more highly educated (15.27 years vs. 13.93 years, t(58) = 1.8, p < .1), more ethnically diverse (22% nonwhite vs. 7% nonwhite, χ2 = 5.28, p < .05), and scored higher on Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE: 28.27 vs. 26.57, t(58) = 4.17, p < .01). Participants also completed the Stroop test (Stroop, 1935) which served as a measure of Executive Cognitive Function.

2.2.2. Materials

The stimulus materials for this experiment were adopted from Holtgraves (1999) and consisted of a set of 24 scenarios (8 target scenarios and 16 filler scenarios). Each scenario (2–6 sentences) described a situation between two people and ended with a question that one person asked the other. The question was then followed by a reply. There were two versions of the scenario and question that preceded each reply. In the indirect meaning version the question always requested information that was potentially face-threatening for either the person asking the question (opinion situation) or the recipient (self-disclosure situation). The reply was a violation of the relevance maxim and hence likely to be interpreted as conveying a negative opinion or disclosure (Holtgraves, 1998). In the control version, the scenario and context supported a literal reading of the reply, and hence an indirect interpretation was not likely to be made. Following the reply was a target sentence that represented an indirect interpretation of the reply in the indirect version. An example is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Scenario used in Experiment 1

| Nick and Paul have been friends for many years. They decided to enroll together in a class on public speaking. Each week students in this class have to give a 20 minute presentation to the class on some topic. Nick gave his first presentation and then decided to ask Paul what he thought of it. (They were talking about the 20 minute presentation they had to make in this class). |

| Nick: What did you think of my presentation? (Don't you think it's hard to give a good presentation?) |

| Paul: It's hard to give a good presentation. |

| Target: I didn't like your presentation. |

Note: the control version is created by substituting the material in parentheses for the preceding italicized material.

Two sets of materials were created with each set containing four indirect meaning scenarios (two opinion and two self-disclosure) and four control scenarios (two opinion and two self-disclosure). If the control version of one scenario appeared in one set, the indirect meaning version appeared in the other set. Participants saw an equal number of indirect and control scenarios/dialogues, and across the experiment, an equal number of participants saw the control and indirect versions of each scenario.

2.2.3. Procedure

The experiment was conducted on a personal computer using the Eprime software. Participants read detailed instructions and then performed eight practice trials. They received feedback as they performed the practice trials. To begin a trial, participants pushed a button and the first sentence of the scenario then appeared on the screen. Participants read at their own pace and pushed a button to proceed through the material. After indicating comprehension of the question, a 500-Hz tone sounded for 250 ms. Two hundred fifty ms. after the tone terminated, the reply from the other interactant was then presented on the screen. Participants were instructed to read the reply and indicate, by pushing the button, that they understood the meaning of the reply. As soon as they indicated comprehension of the reply, a sequence of Xs appeared on the screen (the number of Xs equaled the number of letters in the subsequent target) and a 500-Hz tone sounded. Two hundred fifty ms. later the target appeared. The task for participants was to read the target and decide, as quickly as possible, whether the target was a grammatical sentence. They were instructed to push the button if the target was a sentence and to do nothing if it was not a sentence. If no response was made within 12,500 ms. the next trial was presented. Pretesting indicated that for PD participants, this single-button procedure was easier than a two-button (grammatical sentence – nongrammatical sentence) procedure. Sentence verification speed and judgment (correct/incorrect), as well as reading time for the reply, were automatically recorded. For the 8 critical trials the target was always a grammatical sentence and hence the correct answer was yes. To ensure that participants did not develop the expectation that the target string was always a sentence, 16 filler trials were included. In eight of the filler trials one speaker asked the other to provide an opinion (4) or a disclosure (4); hence, the format was identical to the critical trials. However, the presented target for these trials was clearly not grammatical and hence the correct response was to not push the button. In order to make the set of stimuli more variable, the remaining filler trials did not ask for an opinion or a disclosure. In these other filler trials one speaker made a request or an invitation to the other interactant. For four of these trials the target was grammatical and for four it was not grammatical. Immediately after making a judgment, feedback (correct/incorrect and response time) was provided on the screen for 1500 ms. Feedback was provided in order to increase participant task motivation. Presentation order was randomized for each participant.

2.3. Results

The data from three PD participants were incomplete (due either to an equipment malfunction or the Ps' inability to complete the task) and excluded from all analyses. Sentence verification accuracy, sentence verification speed, and reply reading times were analyzed with a 2 × 2 (Participant Classification: PD vs. Control X Reply Type: Indirect Meaning vs. Control) Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), with repeated measures on the second factor. For decision speed, only error-free trials were included. In addition, because of great variability in reading times, the time taken to read the replies was included as a covariate in analyses of decision speed. Response times greater than three standard deviations above the mean for a participant were treated as outliers and not included in the analyses. All analyses were conducted twice, once with participants as a random variable (F1), and once with stimuli as a random variable (F2). Note, however, that with only eight trials, analyses with stimuli as a random variable have very low power. Preliminary ANOVAs were conducted that included gender and ethnicity (white vs. nonwhite) as factors. Neither of these variables were significant (neither main effects nor interactions) and were dropped from subsequent analyses. In addition, preliminary Analyses of Covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted that included age and education as covariates. Neither of these variables interacted with the dependent measures (although age had a significant effect on overall response times) and were dropped from subsequent analyses. The repeated measures assumption regarding sphericity (Mauchly's test) was met (Chisquare approximation < 1). The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lexical Decision Times and Error Rates as a Function of Speech Act and Participant Classification: Experiment 1

| Reply Type |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect | Direct | Mean | |

| Control Participants | |||

| Sentence Verification Speed | 1944 (122) | 2247 (106) | 2096 (101) |

| Error Rates | 6.2% (2.0) | 7.0% (1.8) | 6.6% (1.1) |

| Reply Reading Times | 2081 (2360 | 2098 (246) | 2089 (224) |

| PD Participants | |||

| Sentence Verification Speed | 2356 (139) | 2306 (121) | 2331 (115) |

| Error Rates | 8.0% (2.3) | 3.0% (2.0) | 5.5% (1.3) |

| Reply Reading Times | 3137 (267) | 3383 (279) | 3260 (253) |

Note: Standard errors are presented in parentheses.

2.3.1. Reply Reading Times

PD participants took significantly longer to read the replies (3260 ms) than did the control participants (2089 ms), F11,55 = 11.97, MSe = 3212820, p < .01, F21,14 = 34.57, MSe = 299002, p < .001. There was no difference in reading times between the indirect reply (2609 ms) and the control reply (2740 ms), F11,55 < 1, MSe = 516788, F21,14 < 1, MSe = 387892, The Participant Classification X Reply Type interaction was nonsignificant, F1(1,55) < 1, MSe = 516788, F21,14 < 1, MSe = 387892.

2.3.2. Error Rates

Error rates for verifying the target sentences were low and similar for PD (5.5%) and control participants (6.6%), F11,55 < 1, MSe = .004, F21,14 < 1, MSe = .001. Hence, PD participants were quite capable of performing this task. In addition, there was no difference in error rates between the indirect reply (7.1%) and the control reply (5.0%), F11,55 < 1, MSe = .015, F21,14 < 1, MSe = .001.

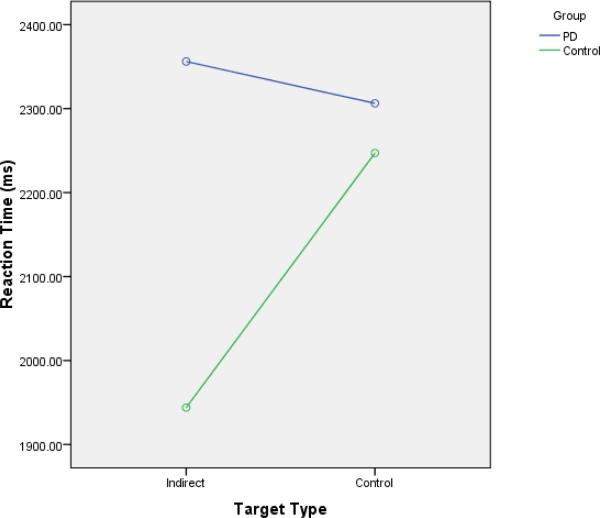

2.3.3. Sentence Verification Speed

Overall, PD participants were slower (2331 ms) than control participants (2096 ms) at verifying the target sentences. This difference only approached significance in the participant analysis, F11,54 = 2.15, p < .15, MSe = 593211, although it was significant in the item analysis, F21,12 = 6.58, MSe = 338913. The lack of significance in the participants analysis was due to the inclusion of reply reading time as a covariate. When reply reading time was not included in the model, the difference between PD and control participants was highly significant, F11,55 = 14.44, MSe = 2302195, p < . 01.

Most importantly, there was a reliable Reply Type X Participant Classification interaction in the participant analysis, F11,53 = 4.34, p < .05, MSe = 164471, although the effect was not significant in the item analysis, F21,12 = 1.25, p < .30, MSe = 89920 (observed power < .18). Simple effects tests indicated that for the indirect reply target, control participants were significantly faster than PD participants, F11,54 = 7.31, MSe = 492629, p < .01, F21,13 = 13.0, p < .01, MSe = 249829; in contrast, the difference between the PD and control participants was not significant for the control target in the participant analysis, F11,54 = 1.64, p > .20, MSe = 468123, although it was significant in the item analysis, F21,13 = 12.54, p < .01, MSe = 176361.

2.4. Subsidiary Analyses

Correlation analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between the activation of indirect meaning (sentence verification speed for the control targets minus sentence verification speed for the indirect reply targets) and disease severity, medication level, and executive cognitive function (Stroop test). The only reliable effects occurred for the Stroop test. The relationship between the Stroop test interference score and indirect meaning activation was marginally significant, r = −.23 (p < .10), a relationship that was greater for PD participants (r = −.34, p < .10) than for control participants (r = −.14, ns). Hence, high interference times on the Stroop test were associated with reduced indirect meaning activation. For PD participants, there was also a significant inverse relationship between Stroop test interference time and sentence verification accuracy for the indirect meaning targets (r = −.45; p < .01) but not for the control targets (r = .03, ns). The difference between PD and control participants in Stroop test performance was not significant, t(54) < 1.

In this experiment, then, non-impaired participants demonstrated automatic activation of the indirect meaning of indirect replies meant to `save face' or reputation. The speed with which they verified targets was enhanced when the target was an indirect interpretation of the preceding reply. PD participants, in contrast, did not show this effect. The inefficient activation of indirect meanings of indirect speech acts could lead to variable or even erroneous interpretations of indirect replies. This issue was explored in Experiment 2 (see Section 3.1.).

3.1. Experiment 2

In this experiment, an off-line task was used in order to examine whether PD participants would generate different interpretations of indirect replies than interpretations generated by controls. The procedure was similar to Holtgraves (1998). In that study, participants read scenarios describing situations (similar to those used in Experiment 1 in Section 2.1.) in which one person asked another person to make a disclosure or give an opinion. The context was manipulated so that the requested information was described as clearly negative, clearly positive, or there was no information provided. For the critical trials, the person's reply to the question was a relevance violation (a reason for why the requested information was negative). Participants were asked to write down how they would interpret the reply, and those interpretations were coded in terms of valence (whether they indicated that the reply should be interpreted as conveying an opinion or disclosure, and if so, whether the conveyed information was negative, positive, or neutral). Participants were given unlimited time to write their replies-thus eliminating the motor disadvantage of PD patients. The critical question is how participants interpret these replies when no context is provided. In Holtgraves (1998), participants overwhelmingly interpreted these types of replies as conveying negative information; in fact, there was no difference between the no context and the negative context condition. The purpose of the present study was to examine whether this pattern of interpretations would occur for PD participants.

3.2. Method

3.2.1. Participants

The participants were the same as in Experiment 1 (see Section 2.2.1.). The order with which participants completed Experiments 1 and 2 was counterbalanced.

3.2.2. Materials

Twelve scenarios (six opinion and six disclosure), similar to those used in Experiment 1 (but with different content; see Section 2.2.2.), were written specifically for this experiment. There were three versions of each scenario. In one version the requested information was described as clearly negative (negative context), in another version the requested information was described as clearly positive (positive context), and in another version no information was provided (neutral context). A sample scenario is presented in Table 3. In addition, there were eight filler scenarios. The fillers included scenarios in which the reply was not a relevance violation, but instead directly conveyed a negative or positive opinion or disclosure. Three sets of stimulus materials were created such that an equal number of participants saw the positive, negative, and no context version of each scenario, and each participant saw an equal number of positive, negative and no context scenarios.

Table 3.

Sample Scenario used in Experiment 2

| Jack is talking with Mike, an old friend of his. Jack gave a party last week that Mike attended. (The party was a big success, and everyone had a great time.) (The party was boring, and no one had a good time.) () Jack wants to know what Mike thought of the party. |

| Jack: Did you enjoy yourself at my party? |

| Mike: It's hard to give a good party. |

| Mike most certainly meant: |

| Mike probably meant: |

| Mike might have meant: |

Note: The material in parentheses represents the context manipulation and illustrates the positive, negative, and no context conditions.

3.2.3. Procedure

Participants were asked to read a scenario and corresponding remarks, and to then write down how they would interpret the reply. Participants were asked to place their interpretations in one of three categories to indicate their degree of confidence in the reply (speaker most certainly meant = 1; speaker probably meant = 2; speaker might have meant = 3). Participants first performed one practice trial. Scenarios were presented two to a page, with pages randomized for each participant.

Participants' responses were coded as either literal or indirect, and if the latter, whether the interpretation was negative, positive or neutral. Two coders independently coded the responses. Their overall agreement rate was 84% and disagreements were resolved via discussion. The percentage of negative interpretation and degree of confidence were the primary dependent measures.

3.3. Results

Participants who failed to provide codeable responses for the 12 critical trials were excluded from the analyses leaving a final N of 43 (20 PD and 23 Control). Number of indirect interpretations and confidence ratings were analyzed with a 2 × 3 (Participant Classification × Context) ANOVA with repeated measures on the last factor. All analyses were conducted twice, once with participants as a random variable, and once with stimuli as a random variable. Preliminary ANOVAs were conducted that included gender and ethnicity (white vs. nonwhite) as factors. Neither of these variables were significant (neither main effects nor interactions) and were dropped from subsequent analyses. In addition, preliminary ANOCOVAs were conducted that included age and education as covariates. Neither of these variables qualified the effects we report below and were dropped from subsequent analyses. The repeated measures assumption regarding sphericity (Mauchly's test) was met (Chisquare approximation < 1).

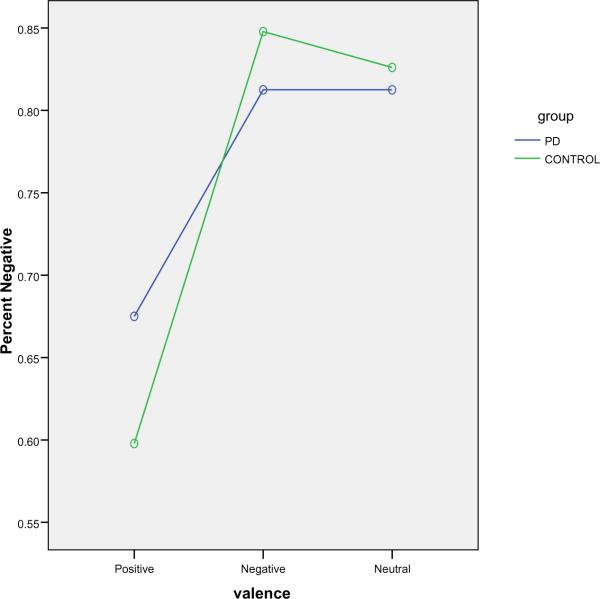

There was a significant effect for valence, F12,82 = 11.63, p < .01, MSe = .174, F22,44 = 9.0, p < .01, MSe = .23. Follow-up tests indicated that there was no difference in the number of negative interpretations for the no context and negative context scenarios (p > .4). The positive scenario resulted in significantly fewer negative interpretations than either the negative or no context versions (both ps < .001). Most importantly, this pattern of data was very similar for both PD and control participants (see figure 2), and the Participant Classification × Valence interaction was not significant, F2,82 = < 1, MSe = .174, F22,44 = 1.28, p > .2, MSe = 1.28.

Figure 2.

Negative Interpretations of Replies as a Function of Context and Participant Classification

For confidence, there was a significant valence effect, F12,53 = 7.2, p < . 05, MSe = .135, F22,44 = 3.53, p = .05, MSe = .067, and participants were more confident of their interpretations in the negative and no context versions than in the positive scenarios (both ps < .01). Again, this pattern of data was very similar for both PD and control participants. However, there was a significant difference between the PD and control participants in terms of overall confidence, F11,55 = 4.57, MSe = .322, p < .01, F22,44 = 4.2, p < .05, MSe = .10. PD participants (M = 1.53) were more confident of their interpretations than the control participants (M = 1.72).

Correlation analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between interpretation and interpretation confidence and disease severity, medication level, and executive cognitive function (Stroop). No reliable effects emerged in this analysis.

In this experiment, both PD patients and controls offered similar interpretations of indirect replies but PD participants were significantly more confident in their interpretations than the control participants. Consistent with other research (McNamara & Durso, 2003; McNamara, Durso, Brown, & Lynch, 2003), this suggests that PD participants may be unaware of communicative problems or overconfident with respect to their ability to interpret veiled or indirect meanings of indirect speech acts.

4.1. Discussion

In a series of experiments on the abilities of patients with Parkinson's Disease (PD) and elderly controls to comprehend face-saving functions of indirect replies, we found that while elderly controls demonstrated automatic activation of the indirect meaning (face saving function) of indirect replies, PD patients did not demonstrate this priming effect. The speed with which elderly controls verified these indirect meanings was enhanced when the target was a face saving indirect interpretation of the preceding reply. PD participants did not show this effect, indicating an inability to rapidly grasp the face saving function of indirect replies. This insensitivity to indirect meanings was marginally related to a measure (Stroop interference task) of executive function indicating that the greater the impairment in striatal-prefrontal networks, the lesser the magnitude of the priming effect. In experiment 2, we showed that while PD and control participants did not differ in their interpretations of indirect replies, PD participants were unjustifiably more confident in their interpretations than the control participants, once again demonstrating an insensitivity of PD patients to indirect meanings of speech acts designed to preserve or adjust the reputation of an interlocutor or some other individual. We do not believe these results are due to a more fundamental sentence comprehension deficit because all PD patients understood all the language materials presented to them and they evidenced no short term memory deficits. Nor do we believe that PD patients were overconfident in their judgments/interpretations because fo their prefrontal dysfunction or attentional dysfunction since there was no correlation between their performance and the Stroop task. We cannot rule out emotional and motivational sources for their over confidence in their interpretations as we did not directly assess the impact of these factors on performance.

Our results demonstrate that the normal cognitive operating system identifies and favors face-saving information even when that information is embedded in indirect replies or meanings. We showed that elderly controls demonstrated an automatic priming effect for indirect meanings of speech acts designed to save face while PD patients with striatal-prefrontal dysfunction did not.

Our results are consistent with other studies that have focused on pragmatics and social cognition in Parkinson's Disease. Using the Prutting and Kirchener (1987) inventory of pragmatic language skills, McNamara and Durso (2003) found that patients with PD were significantly impaired on selected measures of pragmatic communication abilities, including the areas of conversational fluency/appropriateness, speech act production and comprehension, topic-coherence, prosodics and proxemics. This pragmatic impairment, furthermore, was significantly related to measures of frontal lobe function. Bhat et al. (2001) reported similar results in a series of case studies of PD patients who also evidenced deficits in contextual inferencing and in humor appreciation. Berg et al. (2003) reported `high-level' language dysfunction in PD including a significant inferencing deficit (i.e., drawing appropriate inferences from short narratives about social interactions) in mid-stage patients. Berg et al. reported that the language-related inference deficit occurred in individuals without significant cognitive impairment.

Our data carry relevance for competing theoretical accounts of the nature of the deficit in pragmatic language disorders (Kasher, Batori, Soroker, Graves, & Zaidel, 1999; Leinonen & Kerbel, 1999; Martin & McDonald, 2003; Stemmer, 1999). The `social inference theory' account of pragmatic deficits emphasizes antecedent failures in `theory of Mind' functions that render the patient unable to accurately decipher social intentions of others. In PD patients, however, there is little or no evidence of ToM deficits in early stage PD patients who nevertheless evidence communication deficits. The `weak central coherence' or WCC hypothesis of pragmatic deficits points to a general failure to integrate disparate sources of information into a globally coherent picture of the intentions of others as key to pragmatic breakdown. While PD patients do evidence impairment on tasks involving social inferences (e.g., Berg et al., 2003) it is not clear how an inferencing deficit (global or otherwise) could account for the range of pragmatic difficulties seen in the extant disorders associated with pragmatic deficits. Instead we favor an interpretation of pragmatic deficit that respects the relative autonomy of the pragmatic level of linguistic processing and conclude that PD patients evidence a relatively selective linguistic deficit in pragmatic language functions.

On the face of it, PD patients are impaired in pragmatics, in processing indirect speech meanings because of their brain damage-namely damage in the dopaminergic striatal-prefrontal system. It may be that dopaminergic striatal and prefrontal neural networks—networks that have been independently implicated in decision-making processes in games of cooperation, particularly public goods games and games of indirect reciprocity, are crucial in evaluation of complex social cognitive operations involving identification of social standing in complex and dynamically evolving social networks.

Figure 1.

Sentence Verification Speed (ms) for Targets Following Indirect and Control Replies

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by a grant from NIDCD Grant no. 5R01DC007956-03 and is based upon work supported, in part, by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Blakemore SJ, Winston J, Frith U. Social cognitive neuroscience: Where are we heading? Trends in Cognitive Science. 2004;8:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, Levinson SC. Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- de Quervain DJ, Fischbacher U, Treyer V, Schellhammer M, Schnyder U, Buck A, et al. The neural basis of altruistic punishment. Science. 2004;305:1254–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.1100735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Gachter S. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature. 2002;415:137–140. doi: 10.1038/415137a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Rockenbach B. Human altruism: Economic, neural and evolutionary perspectives. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2004;14:784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice HP. Logic and conversation. In: Cole P, Morgan J, editors. Syntax and semantics 3: Speech acts. Academic Press; New York: 1975. pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Holtgraves TM. Interpreting indirect replies. Cognitive Psychology. 1998;37:1–27. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1998.0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtgraves TM. Comprehending indirect replies: When and how are their conveyed meanings activated? Journal of Memory and Language. 1999;41:519–540. [Google Scholar]

- Kasher A, Batori G, Soroker N, Graves D, Zaidel E. Effects of right- and left-hemisphere damage on understanding conversational implicatures. Brain and Language. 1999;68:566–590. doi: 10.1006/brln.1999.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen E, Kerbel D. Relevance theory and pragmatic impairment. International Journal of Language Communication Disorders. 1999;34:367–390. doi: 10.1080/136828299247342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin I, McDonald S. Weak coherence, no theory of mind, or executive dysfunction? Solving the puzzle of pragmatic language disorders. Brain and Language. 2003;85:451–466. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(03)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara P, Durso R. Pragmatic communication skills in Parkinson's disease. Brain and Language. 2003;84:414–423. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00558-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara P, Durso R, Brown A, Lynch A. Counterfactual cognitive deficit in patients with Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2003;74:1065–1070. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.8.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinker S, Nowak M, Lee JJ. The logic of indirect speech. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:833–838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707192105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prutting CA, Kirchner DM. A clinical appraisal of the pragmatic aspects of language. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1987;52:105–119. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5202.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmer B. Introduction to a special issue on pragmatics. Brain and Language. 1999;68:389–391. doi: 10.1006/brln.1999.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reaction. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1935;18:643–662. [Google Scholar]