Abstract

Rationale:

Recurrent ventricular arrhythmias after initial successful defibrillation are associated with poor clinical outcome.

Objective:

We tested the hypothesis that postshock arrhythmias occur due to spontaneous sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca release, delayed afterdepolarization (DAD), and triggered activity (TA) from tissues with high sensitivity of resting membrane voltage (Vm) to elevated intracellular Ca (Cai) (high diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gains).

Methods and Results:

We simultaneously mapped Cai and Vm on epicardial (n=14) or endocardial (n=14) surfaces of Langendorff-perfused rabbit ventricles. Spontaneous Cai elevation (SCaE) was noted after defibrillation in 32% of VT/VF at baseline and in 81% during isoproterenol infusion (0.01~1 μmol/L). SCaE was reproducibly induced by rapid ventricular pacing and inhibited by 3 μmol/L of ryanodine. The SCaE amplitude and slope increased with increasing pacing rate, duration, and dose of isoproterenol. We found TAs originating from 6 of 14 endocardial surfaces but none from epicardial surfaces, despite similar amplitudes and slopes of SCaEs between epicardial and endocardial surfaces. This was because DADs were larger on endocardial surfaces due to higher diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain, compared to those of epicardial surfaces. Purkinje-like potentials preceded TAs in all hearts studied (n=7). IK1 suppression with CsCl (5 mmol/L, n=3), BaCl2 (3 μmol/L, n=3), and low extracellular potassium (1 mmol/L, n=2) enhanced diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain and enabled epicardium to also generate TAs.

Conclusions:

Higher diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain is essential for genesis of TAs and may underlie postshock arrhythmias arising from Purkinje fibers. IK1 is a major factor that determines the diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain.

Keywords: intracellular Ca, delayed afterdepolarization, Purkinje fiber, inward rectifying K current, electrical defibrillation

Postshock arrhythmias, including ventricular tachycardia (VT) and ventricular fibrillation (VF), can occur after initial successful defibrillation shocks. During cardiopulmonary resuscitation, recurrent spontaneous VF occurred in over half of the patients after initial successful defibrillation, and was associated with poor outcomes.1 Electrical storm, a condition in which multiple temporally related episodes of spontaneous VT/VF occur, is known to be associated with high morbidity and mortality.2, 3 The mechanisms of postshock arrhythmias are unclear, although some reports implicate Purkinje fibers as sources of spontaneous VT/VF.2, 4 It is well established that delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) result from Ca-activated transient inward currents (Iti), which are induced by spontaneous sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca release.5 DADs can be induced in Purkinje fibers and atrial/ventricular myocytes.6 However, the vulnerability to DADs is higher in Purkinje fibers than other types of cardiac myocytes.7 Possible explanations for the greater vulnerability in Purkinje fibers to DADs include a higher propensity for SR Ca release than working myocardium, or a larger membrane potential (Vm) response to elevated intracellular Ca (Cai) during diastole (diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain). The differential coupling gain may produce differential vulnerability to DADs. The purpose of this study was to test the hypotheses that (1) DAD-mediated triggered activities (TAs) secondary to spontaneous SR Ca release underlie the mechanism of postshock arrhythmias, and (2) the high diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain in Purkinje fibers predisposes these cells to DADs which initiate TA after successful defibrillation.

Methods

An expanded Methods section is available in the online Data Supplement.

Hearts of New Zealand White rabbits (n=45) were perfused with 37°C oxygenated normal Tyrode's solution. We simultaneously mapped Cai and Vm using Rhod-2 AM and RH237 on epicardial (n=14) or endocardial (n=14) surface of ventricles. In additional hearts, we mapped epicardial surfaces to explore the effect of IK1 suppression (n=8), and endocardial surfaces to study the effect of ryanodine (n=3) and IKr blocker, E-4031(n=2). Transmembrane potential (TMP) was recorded in an additional 4 rabbits. Cytochalasin D (10 μmol/L, n=7) or blebbistatin (10 to 20 μmol/L, n=15) or both (n=23) was used to inhibit contraction during optical and TMP recordings (online Supplement Figure I).

Atrioventricular block was created in all hearts with cryoablation. VF was induced with burst ventricular pacing, and defibrillated with transvenous electrodes. To characterize spontaneous Cai elevation (SCaE), we performed ventricular pacing for 100 beats at a pacing cycle length (PCL) of 600, 500, 400, 300, 200 ms, and the minimum cycle length with 1:1 pacing capture. When substantial SCaEs emerged, pacing at the same PCL with different numbers of paced beats (50, 200, 300, and 400) were performed (n=6) to study a dependence of SCaE on the pacing duration. Isoproterenol at various concentrations (0.01 to 1.0 μmol/L) was administered, and defibrillation and pacing protocols were repeated. We defined the amplitude of baseline Vm and Cai transient as 1 arbitrary unit (AU). A focal ectopy with DAD at the earliest activation site (the onset of the optical action potential was required to precede the QRS onset of pseudo-ECG if it was available) was defined as TA.

Results

Electrophysiological Characteristics of SCaE

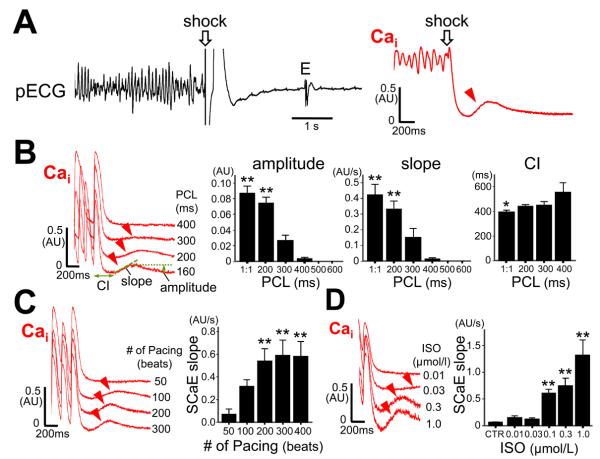

Figure 1A shows pseudo-ECG recording (left panel) and Cai optical signal (right panel) in a fibrillation-defibrillation episode. The red arrowhead indicates SCaE, which occurred 286 ms after the shock. We found SCaEs after successful defibrillation in 11/34 (32%) of induced VF episodes (VF duration: 25 ± 20 seconds, shock intensity: 153 ± 80 V). Postshock SCaEs were noted more frequently (38/47, or 81%) during isoproterenol infusion. SCaEs were also induced after cessation of rapid ventricular pacing, without defibrillation shocks. The amplitude and slope of SCaE and the coupling interval from the last paced beat to the onset of SCaE depended on the PCL (Figure 1B). Shorter PCL elicited higher amplitude and slope of SCaE with shorter coupling intervals. Longer pacing durations increased the amplitude and slope of SCaE (Figure 1C). The incidence of SCaE was 0%, 0%, 0%, 5%, 44%, and 61% at baseline and 0%, 0%, 37%, 72%, 98%, and 100% during isoproterenol infusion after 100-beat pacing at a PCL of 600, 500, 400, 300, 200 ms, and minimal 1:1 capture PCL (145 ± 22 ms), respectively. The magnitude of SCaE were enhanced by isoproterenol in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1D), and the coupling interval of SCaE was shortened with higher dose of isoproterenol (online Supplement Figure II). To determine whether defibrillation shocks affect SCaE, we compared SCaEs with or without S2 shock applied on the refractory period after 100-beat rapid S1 pacing (n=9). The SCaE magnitude was not changed by the S2 shock, indicating intracellular Ca accumulation during tachycardia (rather than shock itself) is responsible for SCaE (online Supplement Figure III). SCaEs were completely suppressed by 3 μmol/L of ryanodine (n=3, online Supplement Figure IV).

Figure 1.

Spontaneous Cai elevation (SCaE). The optical tracings in the figure were taken from a pixel where the maximal SCaE was recorded in the mapped region. A, Pseudo-ECG (pECG) recordings during successful defibrillation of VF. Optical tracing of intracellular Ca (Cai) revealed type A defibrillation, followed by SCaE (arrowhead). B, Dependence of SCaE on pacing cycle length (PCL). *P < 0.05 vs. 400 ms; **P <0.01 vs. 400 to 600 ms. “1:1” indicates the shortest PCL associated with 1:1 capture. C, Dependence of SCaE on pacing duration at a fixed PCL of 200ms. **P < 0.01 vs. 50 beats. D, A dose-dependent effect of isoproterenol (ISO) on SCaE. **P < 0.01 vs. control (CTR). Bar graphs represent means ± SEM; E = escape beat; CI = coupling interval from the last stimulus to the onset of SCaE.

SCaEs occurred in all preparations during isoproterenol infusion, and were present on both epicardial and endocardial surfaces. The amplitude, slope, and coupling interval of SCaE measured at the sites where the maximal SCaE was recorded were comparable between epicardial and endocardial preparations (amplitude: 0.16 ± 0.04 AU vs. 0.16 ± 0.71 AU, slope: 0.77 ± 0.44 AU/s vs. 0.96 ± 0.41 AU/s, coupling interval: 395 ± 83 ms vs. 345 ± 110 ms, P = NS for all).

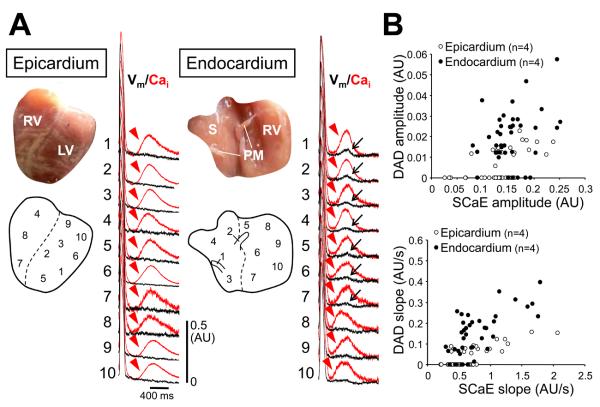

Differential Vm Responses to SCaE Between Epicardial and Endocardial Sites

Despite similar SCaEs on the epicardial and endocardial surfaces, changes in Vm accompanying SCaEs were significantly larger on endocardial surface. Figure 2 shows typical examples of Vm responses to SCaE. SCaEs occurred widely throughout the tissue after rapid pacing during isoproterenol infusion. We randomly selected 10 pixels with apparent SCaEs from each cardiac surface to compare Vm changes during the SCaEs (n=8). SCaEs were found on both cardiac surfaces (red arrowheads). However, there was little change in Vm on epicardial surface, while larger Vm elevations consistent with DADs (black arrows) were observed at some pixels on endocardial surface (Figure 2A). The relationship between the magnitude of SCaEs and DADs is shown in Figure 2B. Notably, for the same magnitude of SCaE, DADs were larger on endocardial surface than epicardial surface, although there were significant heterogeneous responses of Vm to SCaE on both surfaces. If we define “diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain” as the ratio of the DAD magnitude to SCaE magnitude, the gain was greater on the endocardial surface (0.13 ± 0.08 (calculated by amplitude) and 0.19 ± 0.13 (calculated by slope)) than the epicardial surface (0.04 ± 0.05 (by amplitude) and 0.05 ± 0.06 (by slope)) (P < 0.001 for both). At baseline, DADs were found in only 1 heart (4%), although SCaEs were noted in 61% of hearts. With beta-adrenergic stimulation, DADs appeared in 21% and 79% of epicardial and endocardial preparations, respectively (P = 0.004).

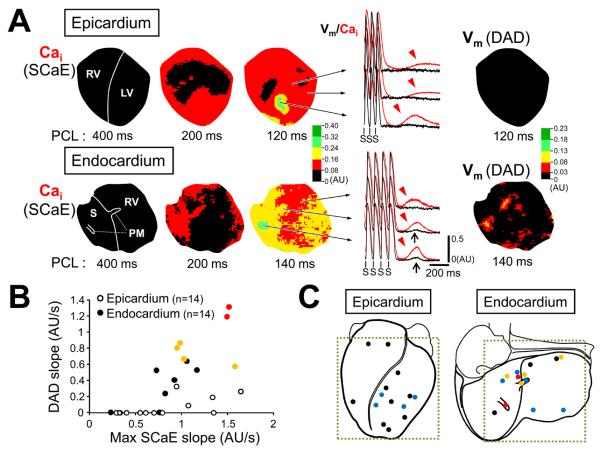

Figure 2.

Differential membrane potential (Vm) responses to Cai changes between epicardial and endocardial surfaces. The black and red lines indicate optical tracings for Vm and Cai, respectively. A, After rapid ventricular pacing, there were SCaEs (arrowheads) at multiple sites. Note that the SCaE at epicardium failed to induce significant changes of Vm. In contrast, the similar magnitude of SCaE resulted in delayed afterdepolarization (DAD, arrow) at endocardium. B, The relationship between the amplitude of DAD and SCaE (upper panel) and between the slope of DAD and SCaE (lower panel). RV = right ventricle; LV = left ventricle; S = interventricular septum; PM = papillary muscle.

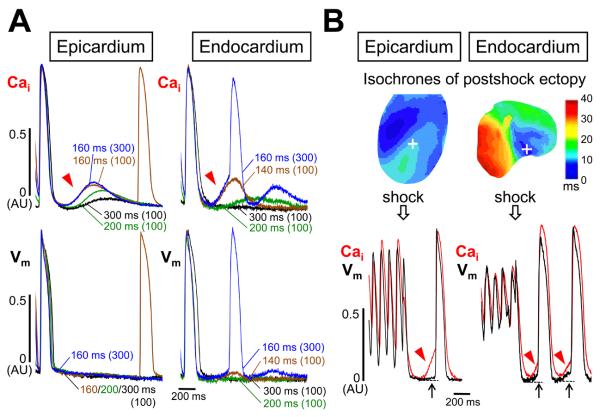

Figure 3 shows the effect of diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain on genesis of TA. In Figure 3A, SCaEs became progressively larger with progressively shorter PCLs on both cardiac surfaces, but rate-dependent increase in DAD amplitude was observed only on endocardial surface. When the number of paced beats was further increased at the PCL that maintained 1:1 capture, DAD reached an activation threshold and TA developed from endocardial surface. No ectopy occurred on epicardial surface, and an ectopic beat conducted from the outside of the mapped region was seen after the SCaE. Figure 3B illustrates SCaEs after defibrillation with postshock ectopic beats. At the early site in epicardium for the postshock beat (dark blue region), no SCaE occurred (not shown). However, a large SCaE (red arrowhead) was found at a site away from the early site (white cross) with only a tiny DAD (black arrow). Consequently, this site was passively activated. In contrast, postshock SCaE accompanied large DADs on endocardial surface, developing TAs. During isoproterenol infusion, TAs arose from the mapped field of endocardial surface in 6 of 14 hearts (43%), while none of 14 hearts showed TAs from epicardial surface (P = 0.008). In 2 of 6 hearts with TAs, VTs were reproducibly induced by rapid pacing. Figure 4A shows an example of triggered VT. Pacing at the PCL of 300 ms induced a single TA. The TA elicited another SCaE that was weaker than the first SCaE, and could not produce a large enough DAD to cause another TA. When the PCL was shortened to 200 ms, larger SCaEs continuously evoked TA, producing VT. The phase plot analysis of Cai against Vm displayed clockwise rotation exclusively at the VT origin (Figure 4B), indicating Cai event occurred before Vm event at the VT origin site. The activation propagated to the rest of ventricle where Cai elevation was secondary to Vm depolarization and the phase plot analyses showed counterclockwise rotations. Snapshots of ratio images during the VT confirmed this relationship between Cai and Vm (Figure 4C). Cai elevation was detected before Vm elevation (Cai prefluorescence, white arrow). Subsequently, the activation wavefront of Vm spread faster than that of Cai.

Figure 3.

Effect of diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain on genesis of triggered activity (TA). A, Simultaneous Vm and Cai optical tracings after pacing at various PCLs for the number of pacing beats indicated in parenthesis. Different line colors were used to mark different episodes. The optical tracings were obtained at the pixel where the maximal SCaE was recorded. On endocardial surface, this site coincided with the earliest site of the ectopic beat (PCL 160 ms for 300 beats). B, Cai and Vm optical tracings recorded at the maximal SCaE sites (white cross) after defibrillation.

Figure 4.

VT originating from endocardial surface. A, (Left panel) A single ectopy (VPC) induced by 100-beat pacing at a PCL of 300 ms. Optical tracings were obtained at the earliest site of the VPC. Preceding SCaEs (arrowheads) and DADs (upward arrows) suggest DAD-mediated TA as the mechanism of the VPC. (Right panel) At a PCL of 200 ms, VT was induced. The earliest activation occurred before the QRS onset of pseudo-ECG. All VT beats had the same origin as that of the VPC. Gradual disappearance of the VT confirms the mechanism is not reentry. Every SCaE accompanied DAD and TA during the VT, but not TA at the VT termination (asterisk). B, Cai elevation preceded Vm elevation only at the VT origin. C, Snapshots of Cai and Vm ratio maps at times from 10 ms before to 40 ms after the QRS onset of the VT beat. Note Cai prefluorescence at the VT origin (white arrow). E = escape beat.

Single or double ectopic beats were observed after successful defibrillation in 5/34 episodes (15%) at baseline, and 12/47 episodes (26%) with isoproterenol. Post-shock VTs (>3 consecutive beats) occurred during isoproterenol infusion in 13/47 episodes (28%) (VT duration: 5.1 ± 3.9 seconds, 3 monomorphic, 10 polymorphic). We found that at least one beat of the VT arose from the mapped region of endocardial surfaces in 4 episodes of post-shock VT but none from epicardial surfaces.

Heterogeneous Distribution of SCaEs, DADs and TAs

SCaEs were not a local phenomenon, but usually appeared over a large area. The area involving SCaE became larger as PCL was shortened. SCaEs might occupy the entire mapped field for short PCLs during isoproterenol infusion. The magnitude of SCaE varied depending on the site, resulting in a spatial heterogeneity of SCaE (Figure 5A). The spatial distribution of SCaE was independent of pacing site (online Supplement Figure V). DADs appeared in areas where large SCaEs were noted. DADs were more appreciable on endocardial surface than on epicardial surface. The maximal amplitude of DADs was significantly larger on endocardial surface (0.057 ± 0.037 AU) than epicardial surface (0.008 ± 0.014 AU, P<0.001). Figure 5B shows the relationship between the maximal SCaE in the mapped area and corresponding DADs. Note that TAs or VTs originated only from endocardial surface due to larger DADs resulting from a higher diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain (We did not use the amplitude of SCaE for these analyses because the occurrence of TAs prevented detection of the maximum SCaE). Figure 5C depicts the distribution of the maximal SCaE. The maximum SCaEs occurred at various sites, without apparently clustering. However, TAs arose frequently from the papillary muscle (PM) or near the summit of the interventricular septum, suggesting increased diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain at those sites.

Figure 5.

Heterogeneous distribution of SCaEs. A, The SCaE maps on epicardial and endocardial surfaces for different PCL. Note that SCaEs occupy nearly all mapped area on both surfaces after 100-beat pacing at the shortest PCL. DADs were evident in the DAD maps for the endocardial surface. B, DAD slopes as a function of SCaE slopes measured at the maximal SCaE in the epicardial (open circles) and endocardial (closed circles) surfaces. Note that TAs (yellow circles) or VTs (red circles) occurred only on endocardial surfaces. C, Distribution of the maximal points of SCaE for each rabbit heart. Black dots depict SCaE only, blue dots for SCaE with DAD, yellow dots for SCaE with TA, red dots for SCaE with VT.

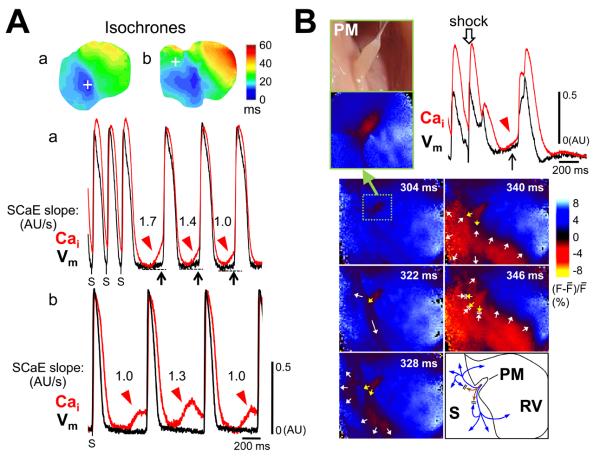

Figure 6A further illustrates the importance of diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain in arrhythmogenesis. Figure 6Aa shows SCaEs (red arrowheads) induced VT at a cycle length of 378 ms. DADs (black arrows) and TAs were present at the VT origin (white cross). The magnitudes of the slope of the SCaEs ranged from 1.7 to 1.0 AU/s in this example. Figure 6Ab shows an idioventricular rhythm with a cycle length of 632 ms observed on the endocardial surface of another rabbit. Of note, SCaEs were present at a site (white cross) away from the early site of the idioventricular rhythm (blue color on isochrones). At the former site, the SCaEs with a slope of 1.0-1.3 AU/s failed to induce any changes of Vm. These findings suggest spatial inhomogeneity of diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain was present within endocardial surface, and the differential coupling gain influenced genesis of ventricular arrhythmias.

Figure 6.

TA from papillary muscle (PM). A, Spatially heterogeneity of diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain. Isochronal maps and optical tracings during VT originating from the PM (panel a) and idioventricular rhythm (panel b). Optical tracings were obtained at the white cross on each isochronal image. SCaEs (red arrowheads) generated DADs (black arrows) and TAs at the VT origin site, while SCaEs were dissociated from the idioventricular rhythm at the non-origin site. B, TA originating from the PM studied with zoom lens (upper panels). Arrow points to large DAD on papillary muscle. Lower panels show snapshots of wavefront propagation with the time of shock as time 0. Schematic diagram shows propagation pattern of two wavefronts from the PM (fast: blue lines, slow: brown lines).

Contribution of Purkinje Fibers to TA Development

The occurrence of TAs on endocardial surface and spatial heterogeneity of diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain suggest Purkinje fibers may be the site of TA, since Purkinje fibers do not cover the endocardial surface uniformly (online Supplement Figure VI). Figure 6B shows optical tracings at the PM display SCaE and DAD. Note that there were two activation wavefronts arising from the PM. One was a fast wavefront conducting away along preferential pathways and reaching the distal part of the ventricle (white arrows). The other was a slow and centrifugally spreading wavefront (yellow arrows) that occurred later and failed to reach the distal area because it collided with the returning fast wavefront at the skirt area of the PM. The former and latter are consistent with wavefront propagation through the Purkinje fiber network and myocardium, respectively. These data are also shown in online Supplement Figure VII and Movies I and II. It is unlikely that this characteristic activation pattern resulted simply from anisotropic myocardial fiber orientation inserting into the PM, because pacing from the PM could not reproduce this pattern (online Supplement Figure VII and Movie III). To confirm the contribution of Purkinje cells on the optical signals, we used E-4031, a selective IKr blocker, in 2 additional hearts. E-4031 is known to prolong APDs more in Purkinje cells than in ventricular myocytes.8 The results (as shown in online Supplement Figure VIII) suggest that Purkinje fibers significantly contribute to the inscription of the endocardial optical tracings in our experimental conditions.

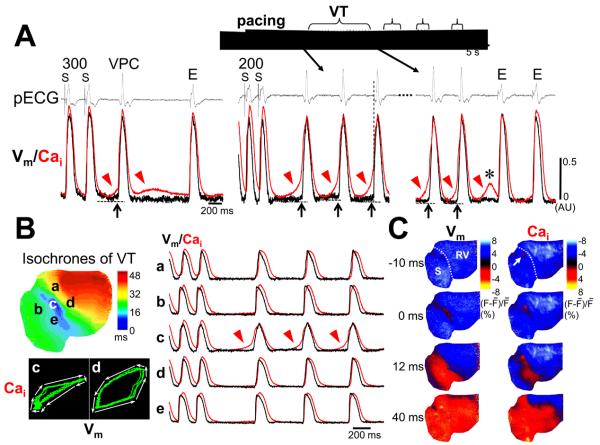

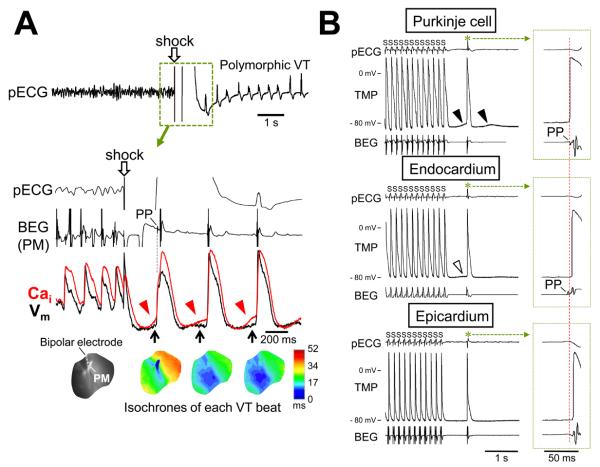

To further ascertain the role of Purkinje fibers in the generation of DADs and TAs, we performed simultaneous recordings of local bipolar electrograms and dual optical signals. Figure 7A shows a fibrillation-defibrillation episode followed by polymorphic VT. The first beat of the VT after defibrillation arose from the PM. Note that the upstroke of the optical action potential coincided with the timing of Purkinje-like potential (PP) recorded at the PM. When a bipolar electrode was placed on early sites of the TA beat (n=3) or the interventricular septum (n=4), the PPs preceding ventricular electrograms were found during TAs in all 7 hearts studied. The PPs were noted in 20/36 episodes (56%) after defibrillation and 70/96 episodes (73%) after pacing (online Supplement Figure IX).

Figure 7.

Role of Purkinje fibers. A, Polymorphic VT after defibrillation. Simultaneous recordings of local bipolar electrograms (BEG) and optical tracings at the PM are shown. The first DAD after defibrillation was large enough to generate TA at this site. Consequently, the first beat of the VT arose from the PM. PP = Purkinje-like potential. B, Simultaneous recordings of transmembrane potentials (TMP) and BEG during pacing-induced TA (asterisks). The top TMP tracing was from Purkinje cells because the phase zero of the action potential was coincidental with PP on BEG. Large DAD (filled arrowhead) was noted prior to the onset of action potential. The middle and bottom tracing shows action potentials with phase zero occurring at the timing of ventricular deflection on BEG. There was little (unfilled arrowhead) or no DADs on these TMP recordings. A red vertical line indicates the QRS onset.

Figure 7B shows TMPs obtained at the site as close to the recording bipolar electrode pair as possible. The top tracing of Figure 7B shows that the phase zero of the action potential occurred simultaneously with PP, indicating that this action potential originated from Purkinje fibers. A large DAD (filled arrowhead) preceded the onset of the action potential. TMP recorded in deeper layer of the endocardium or in the epicardium had little or no DADs, and the onset of action potential occurred at the time of ventricular electrogram. These findings indicate that Purkinje fibers are more prone to develop large DADs and TAs than ventricular myocytes on the endocardium or epicardium.

Role of IK1 for Determining Diastolic Cai-Voltage Coupling Gain

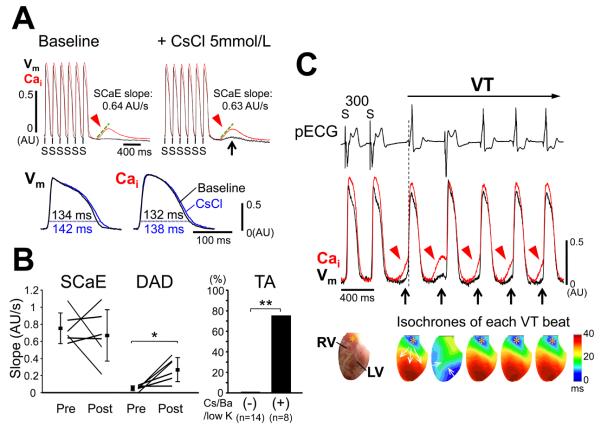

Although our data suggest Purkinje fibers are more susceptible to DADs than ventricular myocytes, the underlying mechanism is unclear. Since inward rectifying potassium current (IK1) is smaller in Purkinje fibers,9 an equivalent Iti will cause a larger amplitude of DAD with lower IK1.10 Therefore, we hypothesized that IK1 might play a key role in higher diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain in Purkinje fibers. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effect of IK1 suppression on SCaE and DAD on epicardium by cesium chloride (CsCl, 5 mmol/L, n=3), barium chloride (BaCl2, 3 μmol/L, n=3), and 1 mmol/L extracellular potassium (low [K+]o, n=2). CsCl or BaCl2 did not exert a significant effect on SCaEs but significantly increased DADs (DAD amplitude: 0.012 ± 0.008 AU to 0.042 ± 0.016 AU, P = 0.013, DAD slope: 0.05 ± 0.03 AU/s to 0.27 ± 0.14 AU/s, P = 0.018), indicating diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain was enhanced CsCl and BaCl2 (Figure 8). Low [K+]o enhanced SCaE, but diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain was also increased (online Supplement Figure X). Notably, TA was never observed from epicardium without IK1 suppression (n=14), while TA occurred from epicardium in 6 of 8 hearts (75%) after IK1 suppression (P <0.001). When we examined the overall incidence of VTs including VTs originating from the outside of the mapped area, VT was induced in 10/28 hearts (36%) with isoproterenol alone and in 6/8 hearts (75%) with isoproterenol and Ik1 suppression. Among 51 VT episodes after IK1 suppression, 9 episodes (24%) included at least one beat arising from epicardium.

Figure 8.

Effect of IK1 suppression. A, (Upper panels) Cai and Vm optical tracings at epicardium. IK1 suppression by CsCl (5 mmol/L) augmented the DAD despite little change in the SCaE. (Lower panels) Changes in optical action potential and Cai transient with CsCl (PCL 200 ms). B, the magnitude of SCaE and DAD before and after CsCl or BaCl2 (left panel) and incidence of TA at epicardium with or without IK1 suppression (right panel). *P < 0.05; **P <0.001. C, VT after IK1 suppression. All VT beats except 2nd beat arose from the epicardial surface of right ventricular outflow tract (asterisks) where SCaEs (arrowheads) and DADs (arrows) preceded the QRS onsets of the VT.

Discussion

SCaE

SCaEs were observed both after defibrillation shocks and after rapid ventricular pacing. The latter findings are consistent with that observed by Fujiwara et al.11 Cai signals obtained with our system represent averaged Cai from multiple myocytes. Faster Cai wave propagation and more synchronized Cai waves would produce more rapidly rising upstrokes of the averaged Cai signal, which is consistent with the PCL-dependent increase in the slope of SCaE. We propose that SCaEs at a tissue level correspond with Cai waves at a cellular level. In line with this proposal, SCaEs were eliminated by ryanodine treatment.

Katra et al12 reported similar spontaneous Cai elevations in a canine wedge model. They observed larger Cai elevations at endocardium than epicardium, whereas we found comparable SCaEs on both cardiac surfaces. This difference might be due to different species and/or experimental protocols. They used an IKs blocker to enhance Ca entry and removed Purkinje fibers to focus on the transmural difference in spontaneous Cai elevation. Rate of Ca uptake was slower in the endocardium than epicardium, which promoted Cai-overload more greatly at endocardium. We did not evaluate the difference in Ca uptake properties because our optical signals from endocardial surface include Cai transients from Purkinje as well as endocardial cells. Our findings indicate vulnerability to DAD and TA is higher in Purkinje fibers than ventricular myocardium in intact whole hearts. Katra et al12 also demonstrated that a sufficiently large spontaneous Cai elevation was necessary for genesis of TA. This holds true for our model, but it should be emphasized that diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain is another important factor for development of TAs.

SCaE and DAD

Despite large SCaEs, large DADs were not consistently observed. As compared with single cells, Cai waves were less likely to cause large DADs because neighboring cells act as an electrotonic current sink.11, 13, 14 A second explanation is that each optical pixel contains a large number of cells. If only Purkinje fibers develop substantial DADs, the DAD amplitude might be reduced artificially by spatial averaging. In the example shown in Figure 6B, we were able to zoom in the lens to obtain a greater spatial resolution of the TA. As expected, the amplitude of DAD was larger in Figure 6B than in other examples because there are fewer cells per pixel. In addition, when diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain was increased by IK1 suppression, DADs also became more apparent because more cells participated in developing DADs in that pixel.

Diastolic Cai-Voltage Coupling Gain

The “gain” in cardiac excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling is defined as the ratio of the total flux through the SR Ca release channels (ryanodine receptor) to that through ICa,L.15 However, reverse E-C coupling (i.e., spontaneous SR Ca release leading to Vm depolarization by Iti) also occurs to generate DADs.5,14 Based on our results, DAD amplitude is determined by at least two factors: the magnitude of the whole cell Cai transient during a diastolic Cai wave, and the sensitivity of resting Vm to the elevated whole cell Cai (diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain). Two major elements of the latter are the amplitude of Iti generating the depolarization and the strength of background outward potassium current opposing depolarization, primarily the IK1. Iti components such as the Na-Ca exchange current (INCX) and Ca-activated Cl current have a similar or lower expression levels and current density in Purkinje cells compared with ventricular myocytes,16, 17 whereas IK1 density is reduced in Purkinje cells.9 We found that, with comparable SCaE, IK1 suppression allowed DADs to occur in epicardial ventricular myocytes. Taken together, these findings suggest that reduced IK1, rather than augmented Cai release or increased INCX, accounts for the greater diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain in Purkinje cells than ventricular myocytes. Reducing IK1 with CsCl or BaCl2 both depolarizes resting Vm, and decreases outward current in the nonlinear negative slope region of IK1 conductance. The experiments with low [K+]o suggest that the latter effect is mainly responsible for increasing the Cai-voltage coupling gain, since low [K+]o, which decreases outward IK1 but hyperpolarizes resting Vm, similarly increased the Cai-voltage coupling gain.18

The importance of diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain is strengthened by the observation that procedures for enhancing Ca entry into myocytes (e.g. high dose of isoproterenol, aggressive pacing protocol) potentiated SCaEs, but did not induce TAs at epicardium without Ik1 suppression. This highlights the importance of diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain as a key contributor to the development of DADs.

Clinical Implications

Our observations show that DAD-mediated TAs in Purkinje fibers can cause recurrence of ventricular arrhythmias following successful defibrillation. While spontaneous VF was not observed in these normal hearts, our previous study showed that recurrent spontaneous VF can occur in failing hearts after successful defibrillation.19 Sympathetic blockade is the most effective medical treatment for electrical storm,3 and successful radiofrequency catheter ablation of VF can be achieved at the site with Purkinje-like potentials.2, 4 Our observations may explain why these treatments are effective.

Catecholaminergic polymorphic VT (CPVT) is an inherited disease characterized by adrenergically mediated VT and VF. Optical mapping study using intact RyR2R4496C+/−hearts revealed Purkinje system served as sources of focal arrhythmias in CPVT, albeit defective ryanodine receptors are present in all cardiac cells.20 These results can be explained by higher diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain of Purkinje cells than ventricular myocytes.

Study limitations

We created atrioventricular block because conducted sinus beats frequently prevented us from analyzing SCaEs, except at sites near the TA origin (online Supplement Figure XI).

In 23 rabbit ventricles, we used both cytochalasin D and blebbistatin to obtain sufficient suppression of contraction during isoproterenol infusion. Although blebbistatin had little effect on action potential morphology and Cai transients,21 cytochalasin D can prolong action potential duration and affect Cai transients.22 However, incidence and characteristics of SCaEs were comparable among experiments using cytochalasin D, blebbistatin, or both drugs.

We used CsCl and BaCl2 to inhibit IK1, but neither was a specific IK1 blocker. Yet, a major effect at the concentration of CsCl and BaCl2 used in this study was IK1 inhibition.23, 24 Because IK1 was crucial in not only stabilizing but also maintaining the resting Vm, abnormal automaticity would occur if the resting Vm of epicardium was depolarized to less than −60 mV.6 However, the concentrations of CsCl and BaCl2 in this study had little effect on the resting Vm,25, 26 and low [K+]o enhanced induction of TAs despite its hyperpolarizing effect on resting Vm.18 Therefore, DAD-mediated TA was a likely mechanism for emergence of the epicardial ectopic activities after IK1 suppression.

Conclusions

SCaEs can emerge in the ventricles after prolonged rapid ventricular pacing or after successful defibrillation. Higher diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain in Purkinje fibers is a likely mechanism underlying the spatial heterogeneity of susceptibility to DADs and TAs. IK1 is a key determinant for the diastolic Cai-voltage coupling gain, and genesis of DAD-mediated triggered arrhythmias. These findings indicate Purkinje fibers are important arrhythmogenic substrates after an initial successful defibrillation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Lei Lin, Jian Tan, and Stephanie Plummer for their assistance.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P01 HL78931, R01 HL78932, and 71140; a Nihon Kohden/St Jude Medical electrophysiology fellowship (Dr Maruyama); Kawata and Laubisch endowments (Dr Weiss), an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award (Dr Lin), and a Medtronic- Zipes endowments (Dr Chen).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Cai

intracellular calcium

- CPVT

catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

- DAD

delayed afterdepolarization

- E-C

excitation-contraction

- IK1

inward rectifying potassium current

- INCX

sodium-calcium exchange current

- Iti

Ca-activated transient inward currents

- [K+]o

extracellular potassium concentration

- PCL

pacing cycle length

- PM

papillary muscle

- SCaE

spontaneous intracellular calcium elevation

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- TA

triggered activity

- TMP

transmembrane potential

- VF

ventricular fibrillation

- Vm

membrane potential

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

Footnotes

Disclosures

CryoCath Technologies, Inc, provided the SurgiFrost probe.

References

- 1.van Alem AP, Post J, Koster RW. VF recurrence: characteristics and patient outcome in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2003;59:181–8. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bansch D, Oyang F, Antz M, Arentz T, Weber R, Val-Mejias JE, Ernst S, Kuck KH. Successful catheter ablation of electrical storm after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108:3011–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103701.30662.5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nademanee K, Taylor R, Bailey WE, Rieders DE, Kosar EM. Treating electrical storm : sympathetic blockade versus advanced cardiac life support-guided therapy. Circulation. 2000;102:742–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.7.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haissaguerre M, Shoda M, Jais P, Nogami A, Shah DC, Kautzner J, Arentz T, Kalushe D, Lamaison D, Griffith M, Cruz F, de Paola A, Gaita F, Hocini M, Garrigue S, Macle L, Weerasooriya R, Clementy J. Mapping and ablation of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 2002;106:962–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027564.55739.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bers DM. Calcium and cardiac rhythms: physiological and pathophysiological. Circ Res. 2002;90:14–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wit AL, Rosen MR. Pathophysiologic mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias. Am Heart J. 1983;106:798–811. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrier GR. Digitalis arrhythmias: role of oscillatory afterpotentials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1977;19:459–74. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(77)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burashnikov A, Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Fever accentuates transmural dispersion of repolarization and facilitates development of early afterdepolarizations and torsade de pointes under long-QT Conditions. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:202–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.691931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cordeiro JM, Spitzer KW, Giles WR. Repolarizing K+ currents in rabbit heart Purkinje cells. J Physiol. 1998;508(Pt 3):811–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.811bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: Roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res. 2001;88:1159–67. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara K, Tanaka H, Mani H, Nakagami T, Takamatsu T. Burst Emergence of Intracellular Ca2+ Waves Evokes Arrhythmogenic Oscillatory Depolarization via the Na+-Ca2+ Exchanger Simultaneous Confocal Recording of Membrane Potential and Intracellular Ca2+ in the Heart. Circ Res. 2008;103:509–18. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katra RP, Laurita KR. Cellular mechanism of calcium-mediated triggered activity in the heart. Circ Res. 2005;96:535–42. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000159387.00749.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houser SR. When does spontaneous sarcoplasmic reticulum CA(2+) release cause a triggered arrythmia? Cellular versus tissue requirements. Circ Res. 2000;87:725–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.9.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ter Keurs HE, Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:457–506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wier WG. Gain and cardiac E-C coupling: revisited and revised. Circ Res. 2007;101:533–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han W, Bao W, Wang Z, Nattel S. Comparison of ion-channel subunit expression in canine cardiac Purkinje fibers and ventricular muscle. Circ Res. 2002;91:790–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000039534.18114.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verkerk AO, Veldkamp MW, Bouman LN, Van Ginneken AC. Calcium-activated Cl(-) current contributes to delayed afterdepolarizations in single Purkinje and ventricular myocytes. Circulation. 2000;101:2639–44. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouchard R, Clark RB, Juhasz AE, Giles WR. Changes in extracellular K+ concentration modulate contractility of rat and rabbit cardiac myocytes via the inward rectifier K+ current IK1. J Physiol. 2004;556:773–90. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa M, Morita N, Tang L, Karagueuzian HS, Weiss JN, Lin SF, Chen PS. Mechanisms of recurrent ventricular fibrillation in a rabbit model of pacing-induced heart failure. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:784–92. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cerrone M, Noujaim SF, Tolkacheva EG, Talkachou A, O'Connell R, Berenfeld O, Anumonwo J, Pandit SV, Vikstrom K, Napolitano C, Priori SG, Jalife J. Arrhythmogenic mechanisms in a mouse model of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Res. 2007;101:1039–48. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fedorov VV, Lozinsky IT, Sosunov EA, Anyukhovsky EP, Rosen MR, Balke CW, Efimov IR. Application of blebbistatin as an excitation-contraction uncoupler for electrophysiologic study of rat and rabbit hearts. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:619–26. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi H, Miyauchi Y, Chou CC, Karagueuzian HS, Chen PS, Lin SF. Effects of cytochalasin D on electrical restitution and the dynamics of ventricular fibrillation in isolated rabbit heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:1077–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morita H, Zipes DP, Morita ST, Wu J. Mechanism of U wave and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in a canine tissue model of Andersen-Tawil syndrome. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:510–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuboi M, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for electrocardiographic and arrhythmic manifestations of Andersen-Tawil syndrome (LQT7) Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:328–35. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brachmann J, Scherlag BJ, Rosenshtraukh LV, Lazzara R. Bradycardia-dependent triggered activity: relevance to drug-induced multiform ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1983;68:846–56. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.68.4.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warren M, Guha PK, Berenfeld O, Zaitsev A, Anumonwo JM, Dhamoon AS, Bagwe S, Taffet SM, Jalife J. Blockade of the inward rectifying potassium current terminates ventricular fibrillation in the guinea pig heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:621–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.