Abstract

Objective

To determine the HIV prevalence rate among tuberculosis (TB) patients in Guangxi, China.

Methods

Stratified cluster sampling and systematic sampling methods were used to select 16 clinics from which pulmonary TB patients were recruited to participate in this study. 2,300 pulmonary TB patients provided information on socio-demographic characteristics, HIV related knowledge and high-risk behaviors, and method of TB diagnosis. Five milliliter blood sample from the regular TB check-up was retained and tested for HIV antibody.

Results

HIV prevalence among pulmonary TB patients was 0.5% (12/2,300). There was no statistical difference in HIV prevalence between urban and rural nor between male and female patients; however TB patients from higher HIV prevalence areas had a higher rate of HIV infection than TB patients from a lower HIV prevalence areas for both rural or urban areas (0.8% vs. 0, x2=7.49, P< 0.01).

Conclusions

HIV prevalence is higher among pulmonary TB patients than among the general population in Guangxi. Program to address the dual infections of HIV/TB are needed.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, HIV, co-infection, China

INTRODUCTION

Immunosuppression as a result of HIV infection increases the frequency and speed of progression from latent tuberculosis (TB) infection to active TB(1, 2). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), TB is one of the major causes of death among HIV infected people, and TB/HIV co-infection has been found to reduce the effectiveness of directly observed therapy (DOT) treatment of TB (3, 4). Concern over growing HIV-driven epidemics of TB has galvanized global consensus on this issue; however large scale implementation of public health strategy to jointly address HIV/TB coinfection(5,8).

China has been identified as one of the countries where a rapidly increasing HIV epidemic could fuel an epidemic of TB.(6,8) China is one of 22 countries with a high TB burden, and has a growing HIV epidemic. In 2000, it was estimated that approximately 9% (range: 7%–12%) of all new TB cases in adults worldwide (of which 31% were in Africa and 26% in the United States) were attributable to HIV infection, as were 12% of the 1.8 million deaths from TB, crippling already overburdened health care resources (7, 8).

A 2000 national TB epidemiology survey conducted in China reported overall TB prevalence of 367 cases per 100,000 (0.0036%), with an estimated 4.5 million active pulmonary TB patients and 1.5 million new infections a year (9, 10). At present, the HIV epidemic in China continues to gain momentum after the first detection of a group of infected injecting drug users (IDU) in southern China in 1989; by 1998 HIV infection had been detected in every province and by 2007 an estimated 700 000 people were thought to be living with HIV/AIDS (11). Although HIV in China disproportionately affects groups such as commercial sex workers (CSWs) and their clients, injecting drug users (IDUs) and men who have sex with men (MSM) (11), people infected with TB tend to be from poor socio-economic backgrounds with limited access to information and adequate health services, such as farmers or laborers.(12) The overlap among the populations vulnerable to HIV and TB infections points to the systematic challenges in controlling the twin epidemics, which must address issues of healthcare access and provision of information on prevention methods.

Should the TB/HIV co-infection rate increase, it is anticipated that providing comprehensive HIV/AIDS care and support to HIV-positive TB patients such as antiretroviral therapy (ART), and the monitoring and management co-infection cases, (14) will be made more difficult. On top of this, health care services in poor areas of China suffer from a lack of infrastructure, aging equipment and a shortage of adequately trained healthcare workers, resulting in additional overburdening of already strained health care institutions (13).

HIV prevalence in TB patients can be used as an indicator of the degree of spread of HIV into the general population. This information is also important for the provision of comprehensive HIV/AIDS care and support (14). A routine TB-HIV integrated surveillance system to monitor and evaluate the implementation of HIV testing and provision of HIV care to TB patients needs to be established. China does not have such surveillance and will require basic information in order to establish this system. As such, there is little published or existing data available on HIV infection rates among TB patients in China.

Guangxi Autonomous Region bears an unusually high burden of pulmonary TB and HIV/AIDS in China. In 2000, Guangxi had a TB prevalence rate of 650/100,000 (15) and the HIV prevalence in 2003 was 0.1% of the general population (16). The purpose of this paper is to determine the HIV prevalence rate among TB patients in Guangxi.

METHODS

Data Collection

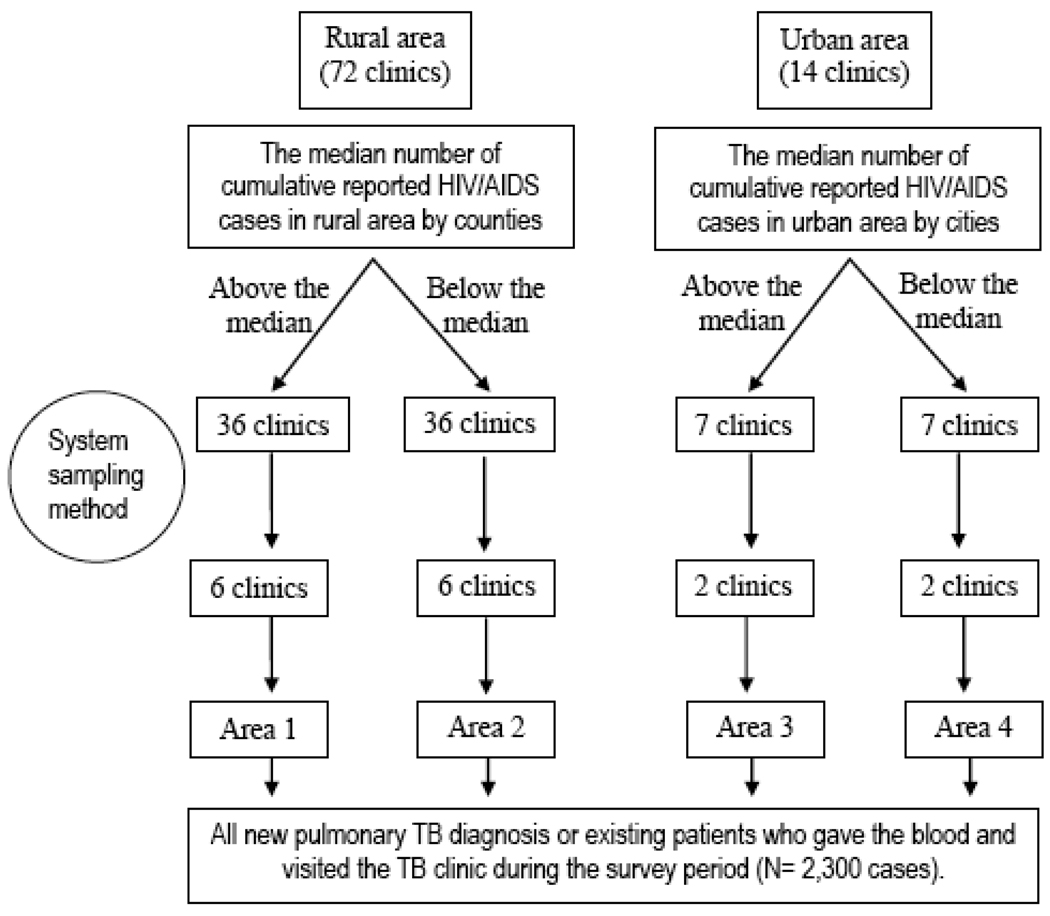

Data was collected between December 2005 and February 2006, and a total of 2,300 participants were recruited as study subjects. A stratified cluster sampling method was used for selecting pulmonary TB patients. Counties were stratified into four types according to whether an area was urban or rural, and whether the number of cumulative reported HIV/AIDS cases was above or below the 2004 provincial-wide by-county median figures for respective type of county (rural, urban). As can be seen in Figure 1, Area 1 sites were identified as rural with above average HIV; Area 2 sites were rural with below average HIV; Area 3 sites were urban with above average HIV; and Area 4 were urban areas with below average HIV (Fig. 1). Of a total of 86 TB treatment clinics administered by the Guangxi Center for TB Prevention and Control, 36 were identified in Area 1, 36 in Area 2, 7 in Area 3, and 7 in Area 4.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the sample selection process

The second stage of sampling consisted of selecting clusters of patients from each area. Six clinics were systematically sampled from each of Areas 1 and 2, and two clinics were from each of Areas 3 and 4 (Fig. 1), for a total of 16 clinics. Consecutive sampling methods were used within the cluster to enroll patients. Trained clinicians at each selected clinic screened newly diagnosed as well as existing pulmonary TB patients for study eligibility. Eligible patients who consented to participate in the study answered questions regarding socio-demographic characteristics, medical history, and HIV/AIDS associated knowledge. Each subject also provided a blood sample for HIV testing.

Pulmonary TB patients were diagnosed in at least one of the following ways: (1) sputum TB tested positive (smear examination or bacillus incubation); (2) sputum tested TB negative, but active TB symptoms were identified through X-RAY; (3) pathological diagnosis of TB; (4) suspected pulmonary TB patient if other pulmonary diseases were ruled out after a follow up X-RAY; and (5) person suffered from TB-related pleuropneumonia (except for thorax hydrocele which can be caused by other infections) (17).

During a regular follow-up visit, blood specimen is taken to test hepatofunction and hemogram. The remainder of the blood sample was used to test for HIV. HIV-positive cases were confirmed by Western Blot method (Test kit made by Genelabs Technologies Inc., Singapore) after testing positive for HIV antibody using two different types of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (the first ELISA test kit was made by Beijing WANTAI Biological Pharmacy Company, Beijing, China, and the second was made by Livzon Group Reagent Factory, Zhuhai, China). All samples were prepared according to Genelabs Technologies Inc.’s instructions and blind-tested at the Guangxi Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, USA) for automated test result interpretation (18).

Data Analysis

All survey data were double-entered at the Guangxi CDC and validated using Epidata 3.0 (The EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark). Data analysis was conducted with SPSS10.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All descriptive data was described using frequencies and median values. Chi-square tests of association were conducted to compare categorical variables.

Quality Control

Standardized protocols and questionnaires were used in each study site by the interviewers to collect data during the survey period. The interviewers were TB clinic doctors and were given interview training by TB and HIV experts from the China CDC (National) and the Guangxi CDC (Provincial). During the survey, 2 supervisors from the China CDC and the Guangxi CDC periodically monitored data collection either in person or via the telephone.

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the institute review board at the National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic Characteristics

A total of 2,300 participants were recruited. The mean age was 41.8 (SD, 17.6) years (Table 1). The majority were male (68.7%), of Han ethnicity (69.2%), married or living with their regular partner (72.2%), and had at least nine years of schooling (72.3%). The most common occupations were farmers and laborers.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants by different areas among pulmonary TB patients, Guangxi, 2005

| Area 1 (%) |

Area 2 (%) |

Area 3 (%) |

Area 4 (%) |

Total (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 979 | 742 | 440 | 139 | 2300 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 71.1 | 69.5 | 64.1 | 62.6 | 68.7 |

| Female | 28.9 | 30.5 | 35.9 | 37.4 | 31.3 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| <15 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| 15–19 | 6.3 | 7.8 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 6.4 |

| 20–29 | 22.9 | 26.5 | 23.8 | 18.6 | 24.0 |

| 30–39 | 17.4 | 18.9 | 17.9 | 17.8 | 18.0 |

| 40–49 | 16.0 | 14.4 | 10.5 | 20.9 | 14.7 |

| 50–59 | 14.4 | 15.5 | 16.9 | 22.5 | 15.8 |

| 60–69 | 11.3 | 10.0 | 12.1 | 13.2 | 11.1 |

| 70- | 11.3 | 6.4 | 11.0 | 2.3 | 9.1 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 42.9 (18.0) |

40.0 (16.7) |

42.3 (18.8) |

42.5 (14.7) |

41.8 (17.6) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Han | 81.4 | 55.4 | 71.8 | 48.2 | 69.2 |

| Zhuang | 17.9 | 41.4 | 25.7 | 49.6 | 28.9 |

| Others | 0.7 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.0 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 25.5 | 27.1 | 23.6 | 16.5 | 25.1 |

| Regular partner | 0.8 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Married | 71.4 | 71.4 | 66.8 | 82.0 | 71.2 |

| Divorced/separated | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Widowed | 1.8 | 0.7 | 6.4 | 1.4 | 2.3 |

| Occupation | 4.0 | 2.7 | 8.8 | 11.5 | 4.9 |

| Agriculture worker | 77.0 | 84.5 | 49.5 | 44.6 | 72.2 |

| Laborer | 2.5 | 2.2 | 6.2 | 10.1 | 3.5 |

| Public servant | 3.3 | 3.9 | 8.8 | 5.0 | 4.6 |

| Student | 6.4 | 2.7 | 12.9 | 20.1 | 7.3 |

| Merchant/business-owner | 6.9 | 4.1 | 13.8 | 8.6 | 7.4 |

| Others | 4.0 | 2.7 | 8.8 | 11.5 | 4.9 |

| Education | |||||

| Never attended school | 10.3 | 12.8 | 21.6 | 9.4 | 13.2 |

| Primary (5–6 years) | 35.4 | 38.0 | 26.8 | 25.2 | 34.0 |

| Secondary (8–9 years) | 40.9 | 41.2 | 29.1 | 33.1 | 38.3 |

| Secondary (11–12 years) | 11.2 | 6.3 | 15.9 | 23.0 | 11.3 |

| College degree or more | 2.1 | 1.6 | 6.6 | 9.4 | 3.3 |

Note: Area 1; rural, above the median; Area 2: rural, below the median; Area 3: urban, above the median; Area 4: urban, below the median. The median is based on the number of cumulative reported HIV/AIDS cases above or below the 2004 Guangxi county median figures.

HIV/AIDS Related Behaviors and Knowledge

Among the 2,300 subjects, 17 (0.7%, 95% CI: 0.4%–1.2%) participants reported a history of injecting drug use, and 53 (2.3%, 95% CI: 1.7%–3.0%) participants reported at least one lifetime commercial sex experience (either as a sex worker or a client). Sixty-nine (3.0%, 95% CI: 2.3%–3.8%) participants had ever received blood transfusions and 57 (2.5%, 95% CI: 1.9%–3.2%) had ever received blood products. Five (0.3%, 95%CI: 0.1%–0.7%) men reported sex with other men.

The United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS (UNGASS) indicators were used to test knowledge of HIV prevention methods. Participants were assigned a score based on the percentage of questions answered correctly. Using this composite indicator, 39 (1.7%) received a score of 100% and the percentage of respondents with perfect scores for Areas 1, 2, 3 and 4, were 1.4%, 1.1%, 3.4% and 1.4%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

HIV Related high-risk behaviors and knowledge among pulmonary TB patients, Guangxi, 2005

| Area 1 |

Area 2 |

Area 3 |

Area 4 |

total |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | %(95%CI) | No. | %(95%CI) | No. | %(95%CI) | No. | %(95%CI) | No. | %(95%CI) | |

| No. of people | 979 | 742 | 440 | 139 | 2300 | |||||

| HIV Knowledge* | 14 | 1.4(0.8–2.4) | 8 | 1.1(0.5–2.0) | 15 | 3.4(1.9–5.6) | 2 | 1.4(0.2–5.1) | 39 | 1.7(1.2–2.3) |

| HIV high-risk behaviors | ||||||||||

| IDU | 14 | 1.4(0.8–2.4) | 0 | - | 1 | 0.2(0.006–1.3) | 2 | 1.4(0.2–5.1) | 17 | 0.7(0.4–1.2) |

| Commercial sex | 41 | 4.2(3.0–5.6) | 8 | 1.1(0.5–2.0) | 2 | 0.5(0.06–1.6) | 2 | 1.4(0.2–5.1) | 53 | 2.3(1.7–3.0) |

| Blood transfusion | 29 | 3.0(2.0–4.2) | 20 | 2.7(1.6–4.1) | 14 | 3.2(1.8–5.3) | 6 | 4.3(1.6–9.2) | 69 | 3.0(2.3–3.8) |

| Blood product use | 28 | 2.9(2.0–4.1) | 18 | 2.4(1.4–3.8) | 1 | 0.2(0.006–1.3) | 9 | 6.5(3.0–11.9) | 57 | 2.5(1.9–3.2) |

| MSM | 2 | 0.3(0.03–1.0) | 1 | 0.2(0.005–1.0) | 2 | 0.7(0.09–2.5) | 0 | - | 5 | 0.3(0.1–0.7) |

Note: Area 1: rural, above the median; Area 2: rural, below the median; Area 3: urban, above the median; Area 4: urban, below the median.

UNGUASS indicator

HIV Prevalence

Twelve participants tested positive for HIV, for a study sample prevalence rate of 0.5% (95% CI: 0.3%~0.9%). There was no significant difference in HIV prevalence between urban (0.5%, 95% CI: 0.1~1.5%) and rural (0.5%, 95% CI: 0.2–1.0%) participants. However, HIV prevalence among pulmonary TB cases selected in the two areas where the cumulative number of HIV/AIDS cases was above the provincial median (0.8%, 95% CI: 0.4~1.5%) was higher than the cases selected from the areas where the cumulative number of HIV/AIDS cases was below the provincial median (0, one-sided 97.5% CI: 0–0.4%), X2 = 7.49, P < 0.01). This finding indicates that TB patients in high HIV settings are more likely to have HIV than TB patients in low HIV settings. No significant difference was found with regard to other variables, including ethnicity, gender, age or occupation (Table 3).

Table 3.

HIV prevalence among Pulmonary TB by different categories, Guangxi, 2005

| No. of Pulmonary TB cases |

No. of HIV- positive |

HIV (%) (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | |||

| <50 | 1496 | 11 | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) |

| 50- | 804 | 1 | 0.1 (0.003–0.7) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1581 | 11 | 0.7 (0.3–1.2) |

| Female | 719 | 1 | 0.1 (0.003–0.8) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Han | 1581 | 10 | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) |

| Zhuang | 662 | 2 | 0.3 (0.04–1.1) |

| Occupation | |||

| Merchant/ business-owner | 165 | 2 | 1.2 (0.1–4.3) |

| Agriculture | 1645 | 10 | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) |

| Others# | 490 | 0 | 0.0 (0–0.8)$ |

| Area type | |||

| Urban | 579 | 3 | 0.5 (0.1–1.5) |

| Rural | 1721 | 9 | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) |

| Reported HIV/AIDS cases over median* | 1419 | 12 | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) |

| Reported HIV/AIDS cases below median | 881 | 0 | 0.0 (0–0.4)$ |

| Area 1 | 979 | 9 | 0.9 (0.4–1.7) |

| Area 2 | 742 | 0 | 0.0 (0–0.5)$ |

| Area 3 | 440 | 3 | 0.7 (0.1–1.2) |

| Area 4 | 139 | 0 | 0.0 (0–2.6)$ |

| Diagnosis methods | |||

| Sputum positive | 971 | 3 | 0.3 (0.06–0.9) |

| Sputum negative | 1 231 | 8 | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) |

| No sputum | 98 | 1 | 1.0 (0.03–5.6) |

| Guangxi Total | 2300 | 12 | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) |

Note: includes labor, student, government staff and

test difference between two groups with cumulative HIV cases over or below the provincial median using chi-square test, χ2=7.49

P<0.01, $ is one sided, 97.5% confidence interval.

CI indicates confidence interval

Among the 12 co-infection cases, 11 were males with ages ranging 20–49. Ten of the cases were either from the Han ethnic group, had completed less than nine years of education or were farmers. Seven of the cases (58.3%) were married. Nine co-infected participants (75%) were diagnosed with pulmonary TB with sputum negative or no sputum tests (Table 3). This result implies that when HIV-positive people are screened for pulmonary TB, diagnosis should not focus solely on sputum positive or incubation positive methods of diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

The 0.5% HIV prevalence found among pulmonary TB patients is markedly higher than the provincial average of 0.1% in Guangxi. This finding is consistent with results reported in African countries (19, 20). The HIV/TB coinfection rate in our study is lower than the national HIV/TB coinfection rate of 4.3% in Vietnam, a neighboring country with a similar national HIV prevalence rate as China but with a higher TB rate. The same rate was even higher in the capital of Ho Chi Minh City: TB patients were found to have HIV prevalence of 9.8% in 2005 (21, 22).

The finding of 0.5% HIV prevalence among TB patients is comparable to similar surveys conducted among TB patients in Hunan and Henan, where HIV/TB co-infection rates of 0.96% and 0.39% respectively were found among TB patients (23, 24). A study conducted in 4 counties of Hebei, a province with lower HIV but high TB prevalence, found 0% HIV infection among its TB patients. while another conducted in a county in Henan found this same rate to be 5.1% (25, 26).

According to the results of this study, HIV/TB co-infection prevalence is 0% in Guangxi in areas with a HIV prevalence rate below the provincial median for rural and urban areas. This suggests the most efficient use of resources would be to establish TB/HIV co-infection sentinel surveillance sites in high HIV prevalence areas, as such sites will be more efficient at finding co-infections.

This study had several limitations. First, the non-probability sampling methods may have resulted in a biased sample; however some researchers have found bias from cluster sampling to be minor compared to estimates derived using simple random sampling (27, 28). Second, ‘self-reporting’ bias may have underestimated more sensitive information such as drug use and commercial sex.

HIV-related TB not only fuels the worldwide TB epidemic and increases the burden of TB control and prevention, but TB has also become the leading cause of death in people living with HIV/AIDS. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests countries with limited resources and in the planning stages of establishing a HIV/TB sentinel surveillance system should periodically conduct HIV screening among pulmonary TB patients (3). However, this study suggests the co-infection prevalence of TB and HIV in Guangxi is not as high as other countries with high HIV and TB burdens where co-infection rates between 1.5–9% have been reported (29). Our study findings suggest TB/HIV co-infection sentinel surveillance sites among pulmonary TB patients should be limited to the areas with a high HIV prevalence in China.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of Qiuying Zhu, Weijiang Lu and all the other public health officers in Guangxi CDC participated in this survey and the doctors in 16 tuberculosis clinics for assist in collecting the data. We also would like to thank. Naomi Juniper and Adrian Liau for reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Source of Funding

This survey was funded by the National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the first author was supported by the China Multidisciplinary AIDS Prevention Training Program with NIH Research Grant # U2R TW06918 funded by the Fogarty International Center, National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Mental Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes PF, Block AB, Davidson PT, et al. Tuberculosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(5):1644–1650. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106063242307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection: recommendations of the Advisory Committee for Elimination of Tuberculosis (ACET) Advisory Committee for the Elimination of Tuberculosis. 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anti tuberculosis drug resistance in the world. Geneva, Switzerland: The WHO/IUATLD global project on antituberculosis surveillance. 1997 WHO/TB/97.

- 4.Anti tuberculosis drug resistance in the world. 2000 Report No.2. WHO/CDS/TB/2000.

- 5.Narain JP, Lo YR. Epidemiology of HIV-TB in Asia. Indian J Med Res. 2004 Oct;120(4):277–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weili A. An overview of the studies on HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis co-infection. Internal Medicine of China. 2007;2(4):604–606. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbett EL, Watt CJ, Walker N, et al. The growing burden of tuberculosis: global trends and interactions with the HIV epidemic. Arch Intern Med. 2003 May 12;163(9):1009–1021. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.9.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.TB/HIV research priorities in resource-limited settings WHO Geneva. 2005

- 9.National tuberculosis epidemiology sample survey office. The report of national tuberculosis sampling epidemiology survey. The Journal of the Chinese Antituberculosis Association. 2002;24(2):65–67. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guiying W, Youlong G, Yumei L, et al. A study of the effect of TB control programs on disease burden. Chin J Hosp Admin. 2001;17(12):717–720. [Google Scholar]

- 11.A Joint Assessment of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Treatment and Care in China (2007) State council AIDS working committee office and UN theme group on AIDS. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Incidence and Death Report of Notifiable Infectious Deasese in CHINA, in 2006. Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lusheng W, Jin M, Yuying X. The Changing Trend and Characteristics of Rural Resident's Needs and Demands of Health Service: one of the reports about studies between situation of Rural Resident's Needs and supply of Health Service and strategy on the resources arrangement. Chinese Health Economics Magazine. 2004;123(1):21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geneva: World Health Organization; Guidelines for HIV surveillance among tuberculosis patients second edition. 2004

- 15.Fang D, Wenhui G. Basic siltuation and influence factor of implementation on tuberculosis DOTS strategy in Guangxi. J of Chinese modern medicine. 2007;4:598–201. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiuying Z, Wei L, Jie C, et al. Analysis of data of AIDS sentinel surveillance from 1996 to 2003 in Guangxi province. Chinese J of AIDS & STD. 2006;12(5):429–432. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The standards of Infectious Diseases diagnosis prescribed in Law of the PRC on the Prevention and Treatment of Infectious Diseases (For Trial Implementation) 900804.

- 18.Chinese National Guideline for Detection of HIV/AIDS (2004 version).

- 19.Daniel OJ, Ogunfowora OB, Oladapo OT. HIV sero-prevalence among children diagnosed with TB in Nigeria. Trop Doct. 2007 Oct;37(4):268–269. doi: 10.1258/004947507782333080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. [2005 October 05];USAIDS'work on tuberculosis in Tanzania. 2006 [cited; Available from: http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/id/tuberculosis/countries/africa/tanzania_profile.html.

- 21.Trinh TT, Shah NS, Mai HA, et al. HIV-associated TB in An Giang Province, Vietnam, 2001–2004: epidemiology and TB treatment outcomes. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(6):e507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran NB, Rein MGJH, Hoang TQ, et al. HIV and Tuberculosis in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam, 1997–2002. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2007. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.060774. [cited; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/eid/content/13/10/pdfs/1463.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Fengping LIU, Hui O. HIV Prevalence Survey among Tuberculosis Patients in Hunan province. Practical Prevention Medicine. 2005;12:115. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xinan Z. Primary analysis of HIV infection in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Chinese J AIDS/STD. 2004;10(5):354–355. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L, Lianying Z, Shuhua Y. Research on Cooperation Mode between TB/HIV Infection Prevention and Control Organizations. Med Anti Prev. 2008;24(2):100–101. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu Y, Erjun F, Shunchen X. Surveillance Method investigation on HIV/TB coinfection. Jounal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2007;6(8):105. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henderson RH, Sundaresan T. Cluster sampling to assess immunization coverage: a review of experience with a simplified sampling method. Bull World Health Organ. 1982;60(2):253–260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemeshow S, Robinson D. Surveys to measure program coverage and impact: a review of the methodology used by the expanded Program on Immunization. World Health Stat Q. 1985;38:65–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Range N, Magnussen P, Mugomela A, et al. HIV and parasitic co-infections in tuberculosis patients: a cross-sectional study in Mwanza, Tanzania. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2007 Jun;101(4):343–351. doi: 10.1179/136485907X176373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]