Abstract

Neurons in the lateral hypothalamus (LH) that synthesize hypocretins (Hcrt-1 and 2) are active during wakefulness and excite lumbar motoneurons. Because hypocretinergic cells also discharge during phasic periods of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, we sought to examine their action on the activity of motoneurons during this state. Accordingly, cat lumbar motoneurons were intracellularly recorded, under α-chloralose anesthesia, prior to (control) and during the carbachol-induced REM sleep-like atonia (REMc). During control conditions, LH stimulation induced excitatory postsynaptic potentials (composite EPSP) in motoneurons. In contrast, during REMc, identical LH stimulation induced inhibitory PSPs in motoneurons. We then tested the effects of LH stimulation on motoneuron responses following the stimulation of the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis (NRGc) which is part of a brainstem-spinal cord system that controls motoneuron excitability in a state-dependent manner. LH stimulation facilitated NRGc stimulation-induced composite EPSP during control conditions whereas it enhanced NRGc stimulation-induced IPSPs during REMc. These intriguing data indicate that the LH exerts a state-dependent control of motor activity. As a first step to understand these results, we examined whether hypocretinergic synaptic mechanisms in the spinal cord were state-dependent. We found that the juxtacellular application of Hcrt-1 induced motoneuron excitation during control conditions whereas motoneuron inhibition was enhanced during REMc. These data indicate that the hypocretinergic system acts on motoneurons in a state-dependent manner via spinal synaptic mechanisms. Thus, deficits in Hcrt-1 may cause the coexistence of incongruous motor signs in cataplectic patients, such as motor suppression during wakefulness and movement disorders during REM sleep.

Introduction

A half century of research has defined the lateral hypothalamus (LH) as the key site for initiating and maintaining survival behaviors, such as fight, flight and food consumption (Anand, et al., 1962, Bandler and Fatouris, 1978, Morgane, 1961, Nosaka, 1996). These emotional/motivational behaviors involve activation of the somatic motor system as well as the autonomic system. Hypocretinergic neurons are located in the LH and project widely to different regions in the neuraxis (de Lecea, et al., 1998, Peyron, et al., 1998, Sakurai, et al., 1998, van den Pol, 1999, Zhang, et al., 2002). They have been implicated in the control of waking behaviors that involve motor activity, such as feeding, reward seeking, and associated autonomic functions (Bourgin, et al., 2000, Boutrel, et al., 2005, Date, et al., 1999, Dube, et al., 1999, Dun, et al., 2000, Edwards, et al., 1999, Griffond, et al., 1999, Horvath, et al., 1999, Kilduff, 2005, Kiyashchenko, et al., 2001, Kuru, et al., 2000, Nakamura, et al., 2000, Sakurai, et al., 1998, Samson, et al., 1999, Sutcliffe and de Lecea, 2000, Thakkar, et al., 2001).

The hypocretinergic control of motoneuron activity can be mediated via direct projections to motoneurons (Fung, et al., 2001, van den Pol, 1999). We have reported that Hcrt-1 excites lumbar motoneurons and stimulation of the LH elicits EPSPs in motoneurons that are partially blocked by the Hcrt-1 receptor antagonist SB-334867 (Yamuy, et al., 2004). The hypocretinergic system could also influence motor activity through its actions on other descending systems. For example, it projects to the nucleus pontis oralis (NPO) and reticularis gigantocellularis (NRGc) which play a crucial role in motor control (Chase, et al., 1976, Chase and Morales, 2005, Jones, 2005, Lai, et al., 1999, Peyron, et al., 1998, Siegel, 2005, Siegel and McGinty, 1977, Siegel, et al., 1983, Zhang, et al., 2004). Stimulation of these nuclei excites motoneurons during wakefulness, whereas inhibition occurs following identical stimulation during REM sleep (Chase, et al., 1986, Fung, et al., 1982). This phenomenon, termed reticular response-reversal, demonstrates the existence, in the brainstem reticular formation, of state-dependent mechanisms for the control of motor activity (Chase, et al., 1976).

Hypocretinergic neurons are maximally active during wakefulness associated with movements (Lee, et al., 2005, Mileykovskiy, et al., 2005, Takahashi, et al., 2008, Torterolo, et al., 2003). Interestingly, it has also been reported that these cells are active during carbachol-induced REM sleep and show spike bursts during the phasic periods of naturally-occurring REM sleep (Mileykovskiy, et al., 2005, Takahashi, et al., 2008, Torterolo, et al., 2001). Whereas the hypocretinergic system enhances the excitability of motoneurons during wakefulness, its action during REM sleep has not been determined. Therefore, we examined the hypocretinergic control of lumbar motoneurons during this state using a classic model of REM sleep atonia, i.e., the motor suppression induced by the microinjection of carbachol into the NPO (Baghdoyan, et al., 1984, Lopez-Rodriguez, et al., 1995, Morales, et al., 1987, Yamuy, et al., 1993). Our study revealed that the hypocretinergic system promotes motoneuron excitation during control conditions and inhibition during carbachol-induced atonia.

Material and Methods

Experiments were performed on 8 adult cats. All animals were in good health and approved for research by the Department of Laboratory Animal Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. All of the experimental procedures were in accord with the guidelines as set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 1996. Details of the surgical procedures and experimental design have been described, in detail, in a previous report (Yamuy, et al., 2004). In the following paragraphs, we present a synopsis of the methods that were employed in the present study.

Surgical Procedures

Surgery was conducted under isoflurane anesthesia (4% in air). During deep anesthesia, a tracheostomy was performed and the right carotid artery and jugular vein were catheterized. Following laminectomy, spinal cord segments L4-S1 were exposed and their dorsal roots cut. The trunk of the following nerves were placed on silver hook electrodes: sciatic, hamstrings, tibial, common peroneal, and quadriceps. Two holes were drilled in the cranium to provide access for cannulae and stimulating electrodes in the LH and NRGc. After completion of surgery, isoflurane was discontinued and anesthesia was maintained with α-chloralose (60 mg/kg). We and others have extensively used α-chloralose anesthesia as a control, baseline condition in behavioral studies; it has been shown that the carbachol-induced REM sleep-like state can be reliably elicited under α-chloralose anesthesia (Dutschmann and Herbert, 1999, Lopez-Rodriguez, et al., 1995, Xi, et al., 1997, Yamuy, et al., 1999).

Stimulation and Recording Procedures

Stainless steel electrodes were used to stimulate the LH (A 10, L 1.5, H -2, (Berman and Jones, 1982) ipsilateral to the spinal cord site of motoneuron recording. The following stimulation parameters were employed: single pulses or trains of 4 pulses (at 300 Hz) of 0.2 to 1.0 mA in amplitude and 0.8 ms in duration were delivered at a frequency of 0.5 Hz. The NRGc (P 8.5, L 1.2, H −6.5 (Berman, 1968) was also stimulated ipsilaterally to the site of spinal cord recording at 0.5 Hz, using single pulses or trains of 4 pulses at 300 Hz, 0.8 ms pulse duration, and 20-100 μA intensity. To induce the state of carbachol-induced REM sleep atonia, the tip of a 1 μl Hamilton syringe was directed to the NPO contralateral to the side of recording in the spinal cord (P 2.5, L 2, H −3.5, according to Berman's atlas).

Intracellular recordings from lumbar motoneurons were obtained prior to and during the REM sleep-like atonic state induced by the microinjection of carbachol into the NPO (0.25 μl of a 2 μg/μl solution of carbachol diluted in saline). We will term this REM sleep-like atonic state REM-carbachol (REMc). This pharmacological model of REM sleep has been extensively used for several decades in order to determine the mechanisms responsible for the generation and maintenance of REM sleep (Amatruda, et al., 1975, Baghdoyan, et al., 1984, Baghdoyan, et al., 1987, Baghdoyan, et al., 1993, George, et al., 1964, Marks and Birabil, 1998, Morales, et al., 1987, Morales, et al., 2006, Shiromani, et al., 1992, Shiromani and McGinty, 1986, Vanni-Mercier, et al., 1989, Yamuy, et al., 1993). It is important to note that the glycine-mediated postsynaptic inhibition of motoneurons that occurs during natural REM sleep is also present during REMc in animals that are anesthetized with α-chloralose, i.e., membrane hyperpolarization and REM sleep specific IPSPs that are blocked by strychnine, decreased input resistance and membrane time constant, and the phenomenon of reticular response-reversal (Fung, et al., 2000, Kohlmeier, et al., 1997, Kohlmeier, et al., 1996, Lopez-Rodriguez, et al., 1995, Xi, et al., 1997, Yamuy, et al., 1999).

Motoneurons were identified by antidromic stimulation of their axons in the ventral roots or hindlimb nerves. Intracellular recordings were performed using broken-tip micropipettes filled with 3 M KC1 or 2 M K-citrate (tip resistances were 5–10 and 15–30 MΩ, respectively); these micropipettes were aligned and glued, under microscopic visualization, to a 5-barreled pipette array that was used for the pressure ejection of various substances (see below). The tip of the recording micropipette protruded 60–150 μm from the tip of the multibarrel assembly. The recording electrodes were connected to a high input impedance preamplifier with negative capacitance compensation (Axoclamp 2A; Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). Intracellular DC records were amplified (10× and 100×) and recorded on VHS tape using a PCM module (model 4000; Vetter, Rebersburg, PA).

Hcrt-1 (100 mM diluted in saline; obtained from American Peptide, Sunnyvale, CA) or its vehicle were applied via two micropipettes of the multibarrel array (15 to 20 μm in total diameter) which were connected to a two-channel picoinjector (model P100; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA); pressures of varying intensity and duration were used (2–50 psi, 0.5–40 sec) to juxtacellularly apply Hcrt-1 or vehicle. For glycine iontophoresis, two micropipettes of the multibarrel array were filled with a solution of glycine (0.5 M in saline, pH 4.0) and connected to a programmable current generator (Neurophore BH-2, Medical Systems). Currents of 100-400 nA were injected to promote the delivery of glycine.

The arterial blood pressure of the cats was constantly monitored; the systolic pressure was kept between 110 and 140 mmHg. Rectal temperature was maintained at 38.5 ± 0.5°C; pCO2 was kept at 4–5%. At the completion of the experiments, DC anodal current (100 μA, 30 sec) was injected at the site of hypothalamic stimulation for subsequent anatomical identification. An overdose of Nembutal (80–100 mg/kg, i.v.) was then administered and the animal was perfused through the aorta with a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde.

Analysis of Data

Data were analyzed from motoneurons that exhibited antidromic action potential amplitudes that were ≥ 55 mV. The following parameters were measured of the depolarizing and hyperpolarizing potentials that were evoked by the stimulation of the NRGc and LH, prior to and during carbachol-induced REM sleep atonia: peak amplitude, measured from baseline to peak; half-width duration, which is the duration of the PSP at half amplitude; half-rise time which is the time from the onset of the PSP to its half amplitude; half-decay time, measured from the peak of the PSP to the point where it repolarized to its half amplitude; decay time, measured from the peak to the point where the PSP returned to baseline; and total duration, measured from the foot of the PSP to the point where it returned to baseline. Changes in membrane potential were measured from baseline before Hcrt-1 ejection to the point of maximum depolarization after Hcrt-1 ejection. The responses of motoneurons to hypothalamic and NRGc stimulation were measured during control and REMc. As previously reported, we defined REMc by the de novo appearance of a large-amplitude IPSP in the response of motoneurons to NRGc stimulation; this IPSP is identical to that which is present uniquely during naturally-occurring REM sleep as well as carbachol-induced REM sleep in cats (Chase, et al., 1986, Fung, et al., 1982, Yamuy, et al., 1994).

The statistical level of significance for the difference between the mean value of each variable obtained from each motoneuron prior to Hcrt-1 application compared with those obtained after Hcrt-1 application was determined using the two-tailed paired Student's t test. For the comparison of data obtained prior to and during REMc, the level of significance was determined using the two-tailed unpaired Student's t test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. Because more than one ejection of Hcrt or vehicle was applied to some motoneurons, the sample numbers for the mean (± SEM) of each variable represent, unless indicated otherwise, the number of experimental trials.

Results

Response of lumbar motoneurons to the stimulation of the LH

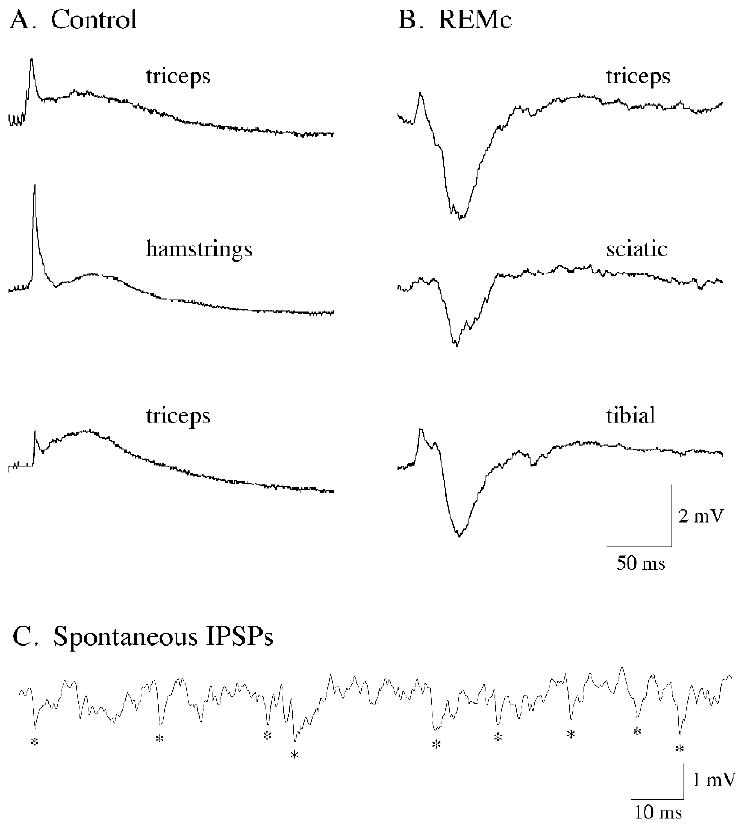

The synaptic response of lumbar motoneurons to hypothalamic stimulation was examined during control conditions and following the microinjection of carbachol into the NPO (i.e., REMc). In 25 motoneurons recorded during control conditions (a population of cells that is partially co-extensive with that used during control conditions in our previous report, Yamuy et al., 2004), the stimulation of the LH elicited depolarizing potentials in motoneurons (Fig. 1A). The excitatory response of these motoneurons consisted of a sequence of two EPSPs separated by a trough and a late, long-lasting hyperpolarization as we have previously described (Yamuy et al., 2004).

Figure 1.

Stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus (LH) promotes motoneuron responses that depend on the ongoing behavioral state. During control conditions, the electrical stimulation of the LH induced excitatory responses in three representative lumbar motoneurons (A; the motoneuron type is indicated in each trace). During the REM sleeplike state of carbachol-induced REM sleep, identical hypothalamic stimulation induced predominantly inhibitory responses in another three representative lumbar motoneurons in the same cats (B; the motoneuron type is indicated in each trace). The appearance of large-amplitude, spontaneous IPSPs in motoneurons was typical during carbachol-induced REM sleep atonia (C; recording obtained from a sciatic motoneuron). The traces in A and B are averages of 15 to 20 sweeps. In each row for panels A and B are responses from lumbar motoneurons that were recorded in the same animal. Hypothalamic stimulation consisted of a 10-ms train (delivered at 0.5 Hz) of four pulses of 0.8 ms duration, at intensities of 0.5 to 1.0 mA.

The response of motoneurons to LH stimulation was then conducted during REMc in the same animals. Stimulation of the identical hypothalamic site during REMc resulted in a remarkable qualitative change in the synaptic response of motoneurons (n = 5). The composite EPSP was suppressed or decreased in amplitude compared to the control state, and a large-amplitude IPSP appeared, de novo, in the response (Fig. 1B). The IPSP induced by hypothalamic stimulation was similar to that which was induced by NRGc stimulation during REMc (see Figs. 2B, 4A and B) (Chase, et al., 1986, Yamuy, et al., 1994). In conjunction with the changes in the motoneuron response following stimulation of the LH and NRGc during REMc, motoneurons exhibited spontaneous, large-amplitude IPSPs similar to those that are present in somatic motoneurons during naturally-occurring REM sleep (Chase and Morales, 2005, Morales and Chase, 1978, Morales, et al., 1981).

Figure 2.

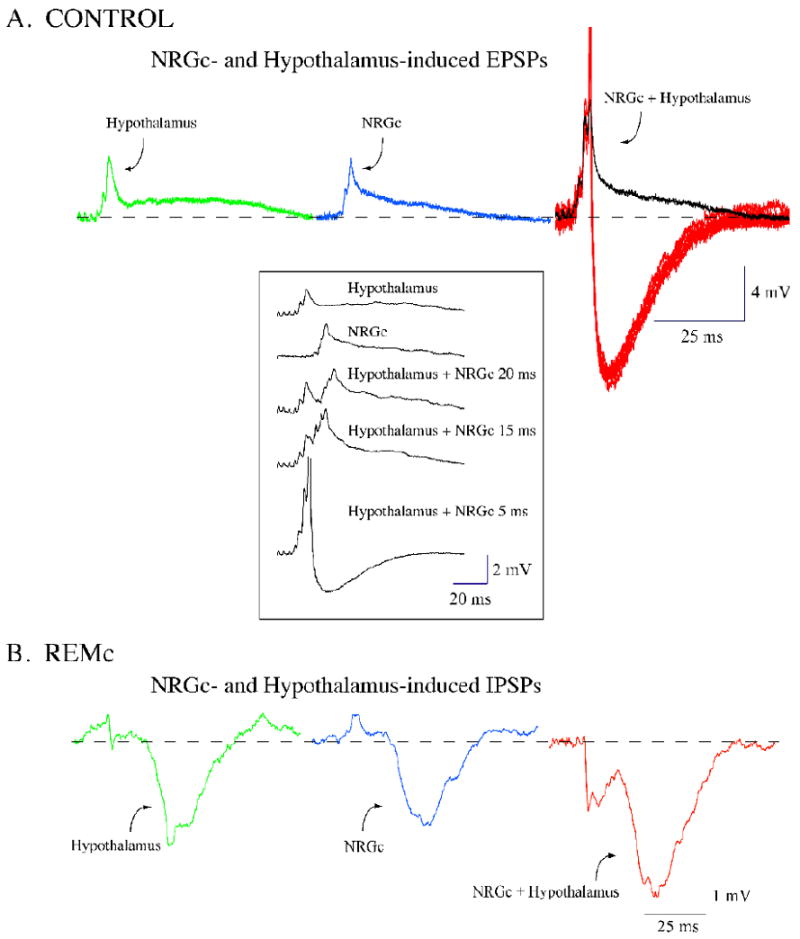

Stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus (LH) facilitates the response of lumbar motoneurons to the stimulation of the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis (NRGc). During control conditions, the motoneuron responses to the separate stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus and NRGc consisted of a sequence of EPSPs (green and blue traces, respectively, in A). The stimulation of the NRGc, with a 5-ms delay after that of the LH, promoted a larger motoneuron excitatory response (black trace in A) that included several spikes (red traces in A). During carbachol-induced REM sleep atonia, a representative motoneuron responded with a large-amplitude IPSP to the stimulation of the LH and NRGc (green and blue traces, respectively, in B). The stimulation of the NRGc with a 5-ms delay after that of the LH promoted a larger motoneuron inhibitory response (red trace in B). Facilitation of excitatory and inhibitory responses occurred at delays that ranged from 0 to 30 ms between hypothalamic and NRGc stimulation. Thus, both excitatory and inhibitory motoneuron responses to the NRGc are expected to be facilitated if neurons in the LH discharge concurrently. The traces are averages of 15 to 20 sweeps except for the spikes in the right-hand traces in A. Recordings in A and B were obtained from two different motoneurons (both responsive to the stimulation of the triceps nerve) in the same animal. Hypothalamic and NRGc stimulation consisted of a 10-ms train (delivered at 0.5 Hz) of four pulses of 0.8 ms duration, at intensities of 0.5 mA and 80 μA, respectively.

Figure 4.

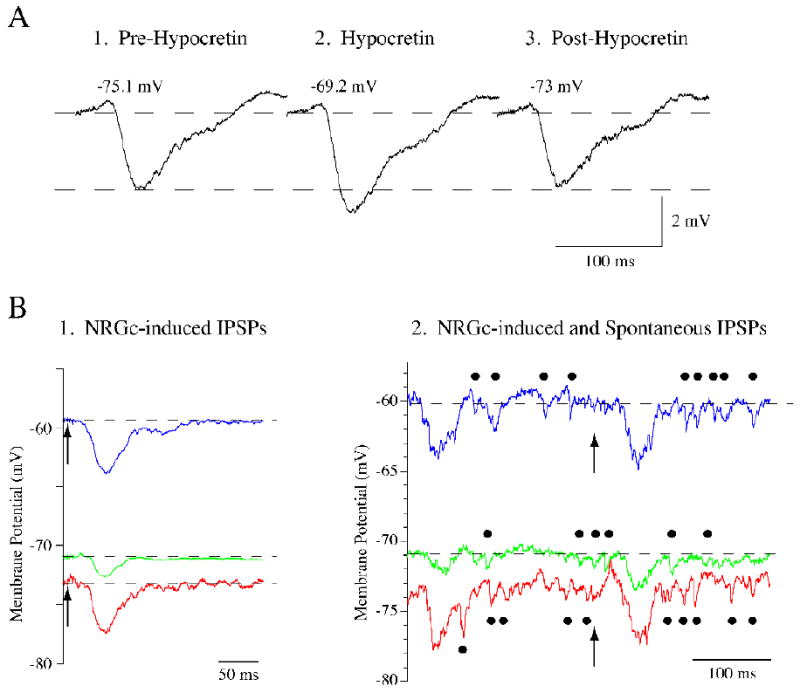

Hypocretin-1 (Hcrt-1) enhances the amplitude of spontaneous and nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis (NRGc)-induced IPSPs and depolarizes lumbar motoneurons during REMc. The NRGc stimulation-induced IPSP in a representative lumbar motoneuron prior to Hcrt-1 application (A1) increased in amplitude following the pressure ejection of Hcrt-1 (A2). After approximately 35 s, the IPSP amplitude returned to control levels (A3). The change in IPSP amplitude occurred in conjunction with membrane depolarization. Note, however, that the amount of depolarization observed in this motoneuron during REMc was considerably smaller than that observed in motoneurons during control conditions (see Fig. 3 and Table 1). NRGc stimulation consisted of a 10-ms train (delivered at 0.5 Hz) of four pulses of 0.8 ms duration, at intensities of 60 μA. Hcrt-1 was ejected at 5 PSI during 5 s. Another triceps motoneuron responded with an IPSP of approximately 1.5 mV to the stimulation of the NRGc (arrows in B1); its membrane potential was -71 mV (green trace in B1). Following the juxtacellular application of Hcrt-1, the cell depolarized approximately 11 mV and the NRGc-induced IPSP increased its amplitude to more than 4 mV (blue trace in B1). Hyperpolarizing current was then passed through the recording electrode to clamp the membrane potential to a level similar to that present prior to Hcrt-1 application. At a membrane potential of approximately −73 mV, the NRGc-induced IPSP was similar to that recorded at depolarized levels (4 mV in amplitude; red trace in B1). This triceps motoneuron showed spontaneous IPSPs during REMc (indicated by filled circles in the green trace in B2). These IPSPs, which also occur typically during natural REM sleep, increased their number and amplitude following the application of Hcrt-1 (indicated by filled circles in blue trace in B2). It can be seen that spontaneous IPSPs also maintained their increased amplitude when the membrane potential was clamped at hyperpolarized levels (indicated by filled circles in red trace in B2). The traces in B1 are averages of 10-20 sweeps whereas in B2 they are individual sweeps. The arrows in B1 and B2 indicate the onset of NRGc stimulation which consisted of a 10-ms train (delivered at 0.5 Hz) of four pulses of 0.8 ms duration, at intensities of 80 μA. Hcrt-1 was ejected at 12 PSI during 20 s.

Given the state-dependent nature of the motoneurons' response to LH and NRGc stimulation, interactions between the responses induced by stimulation of these structures were examined during control conditions and REMc. Using a conditioning-test stimulation paradigm, the composite EPSP induced by NRGc stimulation increased in amplitude with prior (0-30 ms delay) stimulation of the LH. This result is illustrated in Fig. 2A, wherein the response of the motoneuron to the sequential stimulation of the LH and NRGc (at 5 ms delay) is larger in amplitude than those observed following individual stimulation of each of these structures. Note that in six individual responses in Fig. 2A, action potentials were generated following the stimulation of both the LH and NRGc. Similar experiments, which were conducted during REMc, showed that the IPSP induced in motoneurons by NRGc stimulation was also facilitated when a conditioning stimulus was delivered to the LH at a 5 ms delay (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that neurons in the LH are capable of facilitating either excitatory or inhibitory NRGc drives to spinal motoneurons depending on the ongoing behavioral state. Because neurons in the perifornical hypothalamus, including hypocretinergic cells, project extensively to different structures that are involved in the control of motor activity (Date, et al., 2001, Peyron, et al., 1998), the hypothalamic control of motoneurons likely takes place at various levels along the neuraxis (suprasegmental and segmental structures) where feedforward or convergence of efferent pathways of hypothalamic and NRGc origin exist. In the present work, we focused on examining the possibility that the state-dependent effect of LH stimulation and its interaction with state-dependent descending drives on motoneurons from the NRGc, are mediated by the action of Hcrt-1 at the level of the spinal cord. Accordingly, the following experiments were undertaken.

Hcrt-1-induced changes in the motoneuron response to NRGc stimulation during control conditions

In order to test the effects of Hcrt-1 on the NRGc control of spinal motoneurons, we juxtacellularly applied Hcrt-1 onto motoneurons in conjunction with the stimulation of the NRGc. As previously reported, the application of Hcrt-1 during control conditions resulted in depolarization and generation of action potentials in lumbar motoneurons (Yamuy et al., 2004). Figure 3A illustrates the response of a representative lumbar motoneuron to subthreshold stimulation of the NRGc. At resting membrane potential, NRGc stimulation elicited a response that consisted principally of an EPSP with a latency-to-peak of approximately 18 ms (lower trace in A). After 3 s of the juxtacellular application of Hcrt-1, the motoneuron depolarized approximately 13 mV and discharged spontaneously (an example at a lower level of depolarization is depicted in the upper trace in Fig. 3A; the spikes are truncated). After approximately 25 s, the cell began to repolarize; note that while the motoneuron was still depolarized by Hcrt-1, the NRGc-induced EPSP was decreased in amplitude compared to preinjection conditions (Fig. 3A middle trace; see below). Figure 3B shows the averaged responses of this motoneuron during control (upper trace) and following Hcrt-1 application (lower trace), after its spontaneous discharges ceased. Note that both the amplitude and full duration in the motoneuron's excitatory response were reduced. Overall, the juxtacellular application of Hcrt-1 elicited discharges and membrane depolarization that were accompanied, during transient periods of their depolarized state that lacked action potentials, by statistically significant reductions in the amplitude, decay time, 10-90% duration, and full duration in the synaptic excitatory response to NRGc stimulation (Table 1). These data indicate that Hcrt-1 facilitates the excitatory drives of reticular origin and are consistent with the effects that were induced on motoneurons by the electrical stimulation of the LH during control conditions.

Figure 3.

The juxtacellular application of hypocretin-1 (Hcrt-1) induces motoneuron depolarization and facilitates the response to subthreshold stimulation of the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis (NRGc). A hamstrings motoneuron responded with a composite EPSP to the stimulation of the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis (NRGc; green trace in A). Following the juxtacellular pressure ejection of Hcrt-1 while stimulating the NRGc, this motoneuron depolarized approximately 14 mV and discharged action potentials to NRGc stimulation (black trace in A; note that the spikes are truncated). After a period of 25 s, the motoneuron ceased to discharge and, while still depolarized, showed a response to NRGc stimulation that was reduced in amplitude (blue trace in A). Compared to control conditions, the amplitude and duration of the NRGc-induced excitatory response decreased following Hcrt-1 application (traces in B). In another lumbar motoneuron that responded to sciatic nerve stimulation, the application of Hcrt-1 promoted a 16.5 mV depolarization (green and blue traces in C). The membrane potential was then clamped to a level slightly more hyperpolarized than control (red trace in C); note that the amplitude of the second peak of the NRGc-induced response was still reduced (the averaged responses are aligned in the inset in C). The traces in A are individual sweeps whereas in B and C they are averages of 15 to 20 sweeps. NRGc stimulation consisted of a 10-ms train (delivered at 0.5 Hz) of four pulses of 0.8 ms duration, at intensities of 60-100 μA. Hcrt-1 was ejected at 5 PSI during 5 s

Table 1.

Changes produced by hypocretin-1 on the waveform parameters of NRGc-induced synaptic potentials during control conditions and carbachol-induced REM sleep

| Control (EPSPs) | Carbachol-induced REM Sleep (IPSP) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Hcrt-1 | Hcrt-1 | Pre-Hcrt-1 | Hcrt-1 | |

| Amplitude (mV) | 2.43 ± 0.28 | 1.86 ± 0.24*** | -2.3 ± 0.47 | -3.2 ± 0.5** |

| Half-width (ms) | 38.3 ± 9.6 | 29.0 ± 7.4 | 26.4 ± 5.5 | 32.8 ±5.8** |

| Half-rise time (ms) | 9.8 ± 2.98 | 9.7 ± 2.53 | 13.4 ± 3.2 | 10.9 ±1.5 |

| Half-decay time (ms) | 28.6 ± 7.6 | 19.3 ± 5.1 | 16.9 ± 4.5 | 21.9 ± 4.6* |

| Decay time (ms) | 63.8 ± 11.1 | 48.3 ± 10.1* | 60.3 ± 20.0 | 65.8 ± 17.7 |

| 10-90% duration | 87.3 ± 13.9 | 70.7 ± 13.8* | 78.4 ± 21.3 | 86.9 ± 18.5 |

| full duration (ms) | 115.1 ± 16.1 | 86.1 ± 15.3* | 101.1 ± 24.9 | 123.7 ± 22.8* |

The numbers are means ± SE. Motoneuron count for control data is n = 15, whereas that for carbachol-induced REM sleep is 13.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.005;

P < 0.0005.

We next examined whether the decrease in amplitude of the NRGc-induced EPSP was dependent on the membrane depolarization induced by Hcrt-1. As illustrated in Fig. 3C, motoneurons depolarized and the synaptic response to NRGc stimulation was reduced in amplitude following the application of Hcrt-1 (upper trace in C). When the membrane potential was clamped at a level similar to that present prior to Hcrt-1 application, the decrease in amplitude of the NRGc-induced EPSP was maintained in spite of the fact that the membrane potential was significantly hyperpolarized (lower trace in C). This suggests that Hcrt-1 produced an increase in the membrane conductance of lumbar motoneurons.

Hcrt-1-induced changes in the motoneuron response to NRGc stimulation during REMc

We then explored whether Hcrt-1 was involved in the inhibitory response of lumbar motoneurons to stimulation of the LH during REMc. Figure 4A illustrates the typical change produced in a motoneuron by the juxtacellular application of Hcrt-1 during REMc; Hcrt-1 enhanced the amplitude of the NRGc stimulation-induced IPSP and depolarized the motoneuron. Hcrt-1 produced a significant increase in the amplitude, half-width, half-decay time, and full duration of the IPSP induced by NRGc stimulation during REMc. The mean values of these IPSPs prior to and following Hcrt-1 application are presented in Table 1. Overall, these data indicate that the effects on the NRGc stimulation-induced IPSP of the local application of Hcrt-1 onto motoneurons during REMc mimic those induced by LH stimulation.

In 4 lumbar motoneurons (three cats), we examined whether the increased amplitude of the NRGc stimulation-induced IPSP was caused by Hcrt-1-induced membrane depolarization. For this purpose, the membrane potential was clamped at values similar to those that were present prior to Hcrt-1 microapplication by passing hyperpolarizing current through the recording electrode. Under these conditions, the NRGc-induced IPSPs maintained their enhanced amplitude (Fig. 4B). In addition, the amplitude and frequency of the inhibitory synaptic noise (IPSPs) that is present in motoneurons selectively during naturally-occurring REM sleep and REMc also increased following the application of Hcrt-1 (indicated by solid circles in the traces in Fig. 4C); these spontaneous IPSPs maintained an increased amplitude when the membrane potential of the motoneuron was clamped at a hyperpolarized level (Fig. 4C).

The Hcrt-1 induced enhancement of NRGc stimulation-induced IPSPs during REMc was accompanied by motoneuron depolarization (the mean membrane potential changed from -59.9 mV ±3.1 prior to the application of Hcrt-1 to -52.4 mV ± 3.0, following Hcrt-1 application; P < 0.0005 according to the unpaired Student t test). However, Hcrt-1-induced depolarization during control conditions was significantly larger than that which was induced during REMc (11.0 ± 6.3, n = 13 versus 7.5 ± 4.5, n = 13, P < 0.0001, according to the unpaired Student t test).

Hcrt-1 interactions with glycine

The spontaneous and NRGc-induced IPSPs that are selectively present in motoneurons during naturally-occurring REM sleep as well as carbachol-induced REM sleep are known to be mediated by glycine acting postsynaptically on motoneurons (Chase, et al., 1989, Chirwa, et al., 1991, Soja, et al., 1991). Because Hcrt-1 enhanced the IPSPs during REMc, we sought to determine the effects of Hcrt-1 on glycine-mediated postsynaptic inhibition of motoneurons. For this purpose, we examined the interaction of Hcrt-1 and exogenous glycine following their juxtacellular application onto motoneurons during control conditions (n = 3).

Figure 6A illustrates that the application of Hcrt-1 alone promoted motoneuron depolarization and discharges in a representative motoneuron. On the other hand, the application of glycine alone hyperpolarized the membrane potential and decreased the amplitude of the NRGc-induced composite composite EPSP on the same lumbar motoneuron (Fig. 6B)(Chase, et al., 1989, Chirwa, et al., 1991, Soja, et al., 1991, Yamuy, et al., 1994). Finally, the pressure ejection of Hcrt-1 while this motoneuron was hyperpolarized by iontophorezed glycine produced depolarization, firing and increase in the depolarizing synaptic noise of the motoneuron (Fig. 6C). It is interesting to note that, at the doses used in these experiments, the excitatory effect of Hcrt-1 overrode the inhibitory effect of glycine (Fig. 6C). These data indicate that Hcrt-1 antagonizes the postsynaptic inhibition mediated by the application of glycine. Thus, the facilitation of the NRGc-induced and spontaneous, glycine-mediated IPSPs produced by Hcrt-1 is likely exerted via presynaptic mechanisms that result in the enhancement of the release of this inhibitory neurotransmitter.

Discussion

A bimodal action of Hcrt-1 was revealed using intracellular recording techniques in vivo, in combination with juxtacellular application of drugs and electrical stimulation. The integration of these methods in an established model of REM sleep atonia, i.e., REMc, unveiled synaptic processes that would not be apparent using in vitro preparations or unitary recording techniques in vivo. Specifically, we found that a) the stimulation of the LH elicited state-dependent effects on motoneurons, i.e., excitation during control conditions and inhibition during REMc, b) the juxtacellular application of Hcrt-1 onto motoneurons mimicked the effects of LH stimulation, and c) Hcrt-1-induced enhancement of lumbar motoneuron inhibition during REMc is likely mediated by Hcrt-1 acting at presynaptic sites. Overall, these results indicate that the hypocretinergic system controls the activity of spinal motoneurons in a state-dependent manner via synaptic mechanisms located in the spinal cord. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss the results after a brief consideration of the experimental design.

Methodological considerations

The experiments were conducted in vivo and lumbar motoneurons were intracellularly recorded under α-chloralose anesthesia prior to and during REMc. This experimental paradigm poses the following advantages. In vivo experiments provide crucial information vis-á-vis the interaction among structures that comprise a functional network in the central nervous system. It is therefore evident that in vitro preparations would preclude attaining the data presented in this study. In addition, intracellular recordings are necessary in order to reveal the presence and nature of synaptic drives impinging on motoneurons. Synaptic processes, particularly inhibition, cannot be disclosed when extracellular methods of monitoring neuronal activity are employed. It is important to acknowledge, however, that our recordings were carried out during α-chloralose anesthesia which represented the baseline condition for the changes that occurred during REMc. In this respect, a wealth of published data demonstrates that α-chloralose anesthesia can be reliably employed as a control, basal state in order to determine changes that occur in the patterns of activity of neurons during REMc (Kohlmeier, et al., 1996, Kohlmeier, et al., 1998, Lopez-Rodriguez, et al., 1995, Xi, et al., 1997). Moreover, the use of anesthetized preparations as a basal condition for the study of neuronal patterns of activity is extensive (Fenik, et al., 2002, Horner and Kubin, 1999, Lu, et al., 2007). In addition, the membrane properties of motoneurons during this state (Kohlmeier, et al., 1996, Lopez-Rodriguez, et al., 1995, Xi, et al., 1997) are similar to those present during wakefulness as well as NREM sleep (Morales and Chase, 1981, Morales, et al., 1981), and the synaptic response of motoneurons to stimulation of the ponto-medullary reticular formation is virtually identical to that which occurs during the naturally-occurring states of wakefulness and NREM sleep in freely behaving animals (Chase, et al., 1986, Fung, et al., 1982).

Stimulation of the LH

Conditioning stimuli to the LH facilitated the NRGc stimulation-induced excitatory response that is present in motoneurons during control conditions (Chase, et al., 1986, Pereda, et al., 1990, Yamuy, et al., 1994). These data indicate that NRGc-induced excitation of spinal motoneurons is facilitated by the activation of neurons in the LH, including Hcrt-1-containing cells (see below). Given the extensive projections of hypocretinergic neurons throughout the neuraxis, their control of motor facilitation may take place at various levels wherein there is convergence of hypocretinergic and NRGc motor facilitatory drives. First, part of the interaction between the hypocretinergic cells and descending projections from the NRGc possibly occurs within the spinal cord where these systems may converge on excitatory interneurons and/or directly on motoneurons (Fung, et al., 1982, van den Pol, 1999, Wyzinski, et al., 1978, Yamuy, et al., 1994). The fact that the LH stimulation-induced excitatory response in motoneurons was partially blocked by the Hcrt-1 receptor antagonist SB-334867 (Yamuy, et al., 2004) supports the concept that the hypocretinergic system can facilitate NRGc motor drives at the level of the anterior horn in the spinal cord via pre- or postsynaptic mechanisms. Second, because hypocretinergic neurons project to cells in the NRGc (Peyron, et al., 1998, Zhang, et al., 2004), it is possible that NRGc excitatory drives to motoneurons are enhanced following the stimulation of the LH. Third, the NPO as well as the cholinergic and monoaminergic systems in the brainstem, which are known to receive numerous projections from hypocretinergic neurons, innervate cells in the NRGc; moreover, monoaminergic neurons in the raphe and locus coeruleus project to motoneurons (Fung and Barnes, 1987, Holmes and Jones, 1994, Holmes, et al., 1994, Jones, 1990, Jones, 1991, Rodrigo-Angulo, et al., 2000, Semba, 1993, Semba, et al., 1990, Shammah-Lagnado, et al., 1987). Thus, the mutually facilitatory interaction between the LH and NRGc may be integrated at diverse synaptic relays at suprasegmental and segmental levels.

The stimulation of the LH during REMc evoked a synaptic response in motoneurons characterized by the de novo appearance of a large-amplitude IPSP. Moreover, the IPSP induced by NRGc stimulation during REMc increased in amplitude when conditioning stimuli were applied to the LH. This mimics the phenomenon of reticular response-reversal wherein motor excitation is induced following the stimulation of the NPO and NRGc during wakefulness and NREM sleep and inhibition is produced following their stimulation during REMc and naturally-occurring REM sleep (Chase, et al., 1976, Chase, et al., 1986, Fung, et al., 1982, Yamuy, et al., 1994). Thus, the synaptic drive to motoneurons that originates in the LH is dependent on the animal's behavioral state which indicates that a gating mechanism that facilitates motor inhibition exists either in the hypothalamus or at a downstream synaptic relay along the LH motor pathway. In this regard, it has been proposed that glycinergic neurons located within the medullary reticular formation are responsible for the postsynaptic inhibition of somatic motoneurons during REM sleep (Morales, et al., 2006). It is therefore likely that, during REMc, stimulation of the LH directly or indirectly activated the glycinergic premotor neurons responsible for promoting motor inhibition during REM sleep.

Finally, it should be considered that other neuronal phenotypes, which are interspersed with hypocretinergic cells in the LH, were probably excited by electrical stimulation and may have contributed to the response of motoneurons. The LH is a heterogeneous region that contains various neuronal phenotypes, including hypocretin-, melanin concentrating hormone (MCH)-, and excitatory and inhibitory amino acid-containing cells. For example, it is possible that MCH-containing neurons contributed to the LH stimulation-induced IPSP. MCH-containing cells are active during REM sleep, project to motor nuclei and the neuropeptide has an inhibitory action (Gao and van den Pol, 2001, McGregor, et al., 2005, Modirrousta, et al., 2005, Torterolo, et al., 2006, Verret, et al., 2003). However, because MCH-induced inhibitory action is presynaptic (Gao and van den Pol, 2001, Zheng, et al., 2005), it is unlikely that the activation of MCH neurons results in enhancing the release of glycine at presynaptic sites in the motoneuron neuropil. Notwithstanding the possibility that MCH neurons may have contributed to the inhibition of motoneurons during REMc, here we sought to test the hypothesis that the state-dependent effect of LH stimulation and its interaction with state-dependent descending drives on motoneurons from the NRGc, are mediated, in part, by the action of Hcrt-1 at the level of the spinal cord. Accordingly, we examined the effects of juxtacellularly applied Hcrt-1 on lumbar motoneurons during control conditions and REMc.

Effects of juxtacellularly applied Hcrt-1 on the motoneuron response to NRGc stimulation

We first examined the effects of Hcrt-1 on the motoneuron synaptic response to NRGc stimulation during control conditions. The juxtacellular application of Hcrt-1 elicited motoneuron depolarization and action potentials following subthreshold NRGc stimulation. These data indicate that Hcrt-1 facilitated the excitatory effects induced by descending reticular pathways. The strong depolarization that followed Hcrt-1 was expected to result in a decreased amplitude of the NRGc-induced EPSP (Curro Dossi, et al., 1991). However, the Hcrt-1-induced decreased amplitude in this EPSP was maintained even though the membrane potential was clamped at hyperpolarized levels. Whereas adequate space clamping of the membrane potential is difficult in lumbar motoneurons with large dendritic arborizations, the maintained decrease in the EPSP amplitude together with the decrease in the duration and decay of the NRGc-induced EPSP following the application of Hcrt-1 are consistent with the concept that Hcrt-1 produced an increase in the membrane conductance of motoneurons (Fuentealba, et al., 2004). In this regard, we have previously reported that, during control conditions, Hcrt-1 decreases the rheobasic current of motoneurons in conjunction with a voltage-independent increase in their membrane conductance as indicated by a reduction in the membrane time constant (Yamuy et al., 2004); the motoneuron input resistance, measured by the “direct method” did not change (ibid.). These data are in agreement with the concept that Hcrt-1 induces an increase in the membrane conductance for Ca++ and the activation of the Na+/Ca++ exchanger (Burlet, et al., 2002, Eriksson, et al., 2001, Johansson, et al., 2007, Kohlmeier, et al., 2004, van den Pol, et al., 1998). Experiments conducted in vitro that allow for the control of the extracellular milieu and the use of pharmacological tools under current- and voltage-clamp conditions are necessary to identify the specific ion currents that are activated in lumbar motoneurons following juxtacellular application of Hcrt-1.

The foregoing data suggest that Hcrt-1 acted, in part, postsynaptically on lumbar motoneurons (ibid.). However, because in some motoneurons there was an increase in the depolarizing membrane noise following the application of Hcrt-1, it is likely that presynaptic mechanisms also contributed to the excitatory action of this peptide during control conditions. It has been reported that hypocretins are capable of enhancing the presynaptic release of excitatory neurotransmitters such as glutamate (Burlet, et al., 2002, Li, et al., 2002, Ono, et al., 2008, Peever, et al., 2003, Smith, et al., 2002, van den Pol, et al., 1998). Regardless of the synaptic mechanism involved, the data indicate that juxtacellular application of Hcrt-1 during control conditions produces effects that are similar to those obtained following the electrical stimulation of the LH, i.e., both depolarized the motoneurons during control conditions whereas they enhanced the NRGc stimulation-induced IPSP during REMc.

We next examined the effects of Hcrt-1 on lumbar motoneurons during REMc. Following the juxtacellular application of Hcrt-1 during REMc, motoneurons depolarized. However, the amount of depolarization produced by the application of Hcrt-1 during REMc was significantly smaller than that which Hcrt-1 produced during control conditions. The reduction of the Hcrt-1-induced excitatory effect may be in part due to the fact that, during REMc and natural REM sleep, the motoneuron membrane conductance is increased due to the shunting effect produced by glycine-mediated postsynaptic inhibition (Chase, et al., 1989, Morales and Chase, 1981, Morales, et al., 1987, Morales, et al., 1987, Morales, et al., 1981, Soja, et al., 1987, Soja, et al., 1990). Therefore, our results indicate that the efficacy of Hcrt-1 excitatory action on motoneurons is diminished in the context of the motor suppression that occurs during REMc.

As previously reported, during REMc, the stimulation of the NRGc evoked large-amplitude IPSPs and spontaneous IPSPs bombarded motoneurons (Chase, et al., 1986, Morales and Chase, 1982, Morales, et al., 1981, Yamuy, et al., 1999). The application of Hcrt-1 onto motoneurons during REMc produced an increase in the amplitude of NRGc-induced IPSPs and the membrane synaptic inhibitory noise. Whereas the observed increase in IPSP amplitude may have been caused by motoneuron depolarization, the enhancement in the frequency of spontaneous inhibitory synaptic noise suggests that Hcrt-1 acted presynaptically. In addition, both NRGc stimulation-induced and spontaneous IPSPs were still enhanced when the membrane potential was clamped at a level equivalent to that which was present prior to Hcrt-1 application; this result indicates that the Hcrt-1-induced enhancement of the IPSPs did not depend on membrane depolarization. Moreover, the application of Hcrt-1 antagonized the motoneuron inhibition produced by glycine which indicates that Hcrt-1 does not play an agonistic action with glycine on motoneurons.

Taken together, the foregoing results indicate that Hcrt-1 facilitates the REMc-specific IPSPs through presynaptic mechanisms that result in an enhanced release of glycine. This concept is in agreement with previous studies that have reported that hypocretins enhance the release of inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitters in various sites in the central nervous system (Dergacheva, et al., 2005, Ma, et al., 2007, van den Pol, et al., 1998). Therefore, the present data indicate that the activation of hypocretinergic neurons during REMc (Torterolo, et al., 2001) and phasic periods of natural REM sleep (Mileykovskiy, et al., 2005) enhances the inhibition of lumbar motoneurons.

Regarding the contrasting effects of Hcrt-1 during control conditions and REMc, it is important to note that hypocretin-induced enhancement in the release of excitatory and/or inhibitory transmitters has been reported to occur at sites in the CNS that are involved in various physiologic processes (Acuna-Goycolea and van den Pol, 2009, Burlet, et al., 2002, Dergacheva, et al., 2005, van den Pol, et al., 1998). In this context, the present results obtained in vivo raise the possibility that a dual, state-dependent action on target neurons constitutes a distinctive role of hypocretins in the control of behavior.

Functional considerations

Multiple lines of evidence indicate that hypocretinergic neurons are maximally active during wakefulness associated with movements and show a lower level of activity during REM sleep and REMc (Kiyashchenko, et al., 2002, Lee, et al., 2005, Mileykovskiy, et al., 2005, Takahashi, et al., 2008, Torterolo, et al., 2001). Interestingly, Mileykovskiy et al. (2005) reported that hypocretinergic neurons discharge at low frequency during tonic periods of REM sleep and in bursts during phasic periods of REM sleep when twitches occur. On the other hand, our data indicate that a) the activation of neurons in the LH promotes excitation during control conditions and inhibition during REMc, i.e., it controls the excitability of spinal motoneurons in a state-dependent fashion, and b) that this bimodal action is, at least in part, integrated at segmental synaptic sites within the motoneuron neuropil and mediated by Hcrt-1, and c) Hcrt-1-induced effects on motoneurons are in part exerted by presynaptic mechanisms. It is therefore necessary to reconcile our results with a possible physiologic role played by hypocretins in the control of motor activity during wakefulness and REM sleep. The most parsimonious interpretation is that the hypocretinergic system acts on motoneurons to promote excitation or inhibition by enhancing the presynaptic release of excitatory or inhibitory neurotransmitters, i.e., glutamate and glycine. Thus, in addition to its postsynaptic action, hypocretin may modulate the excitability of motoneurons by facilitating the synaptic inputs that are preponderant in each behavioral state, i.e., excitatory during wakefulness or inhibitory during REM sleep. During phasic REM sleep myoclonic twitches, which are correlated with spikes that occur during transient motoneuron depolarization shifts mediated by non-NMDA receptors (Soja, et al., 1995), hypocretin synaptic release may limit the discharge of motoneurons due to the predominant glycinergic input throughout REM sleep (Chase and Morales, 1983). This action would reinforce coherence in the regulation of motoneuron excitability across behavioral states. In fact, dysregulation of motor activity is present in cataplectic patients; they show motor suppression during wakefulness and enhanced motor activity, i.e., persistent muscle tone and excessive muscle twitching, during REM sleep (Dauvilliers, et al., 2007, Kilduff, 2005, Schenck and Mahowald, 1992, Siegel, 2004). Our data indicate that the lack of hypocretin-induced, state-dependent modulation of motoneuron excitability may be the basis for the coexistence of these apparently incongruous motor signs in cataplexy.

Figure 5.

Hypocretin-1 antagonizes the postsynaptic inhibitory action of glycine on motoneurons. The subthreshold stimulation of the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis (NRGc) elicited a depolarizing synaptic response in a lumbar motoneuron (green trace in A); following the application of Hcrt-1, the motoneuron depolarized and responded with a train of action potentials to NRGc stimulation (red trace in A). In contrast, the NRGc-induced depolarizing potential in the same motoneuron (green trace in B) decreased three-fold in amplitude following the juxtacellular iontophoretic application of glycine (red trace in B). The iontophoresis of glycine onto the same lumbar motoneuron produced a hyperpolarization of approximately 3 mV (C, glycine application is indicated by the black-filled bar). After 21 s of glycine iontophoresis, Hcrt-1 was pressure-ejected (red bar in C); subsequently, the motoneuron depolarized, discharged action potentials, and an increase in synaptic noise appeared. Approximately 45 s after the application of Hcrt-1, while glycine was still being iontophorezed, the motoneuron began to hyperpolarize. The membrane potential returned to baseline levels after 8 s of discontinuing the application of glycine. The traces in A and B are averages of 10-20 sweeps except for the upper trace in A which is an individual sweep. All recordings in A and B were obtained from the same motoneuron which discharged antidromic spikes following the stimulation of the ventral root. NRGc stimulation consisted of a 10-ms train (delivered at 0.5 Hz) of four pulses of 0.8 ms duration, at an intensity of 100 μA. Hcrt-1 was ejected at 15 PSI during 20 s; glycine was iontophorezed from two barrels using a current of 400 nA for each barrel.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Oscar Ramos, Andrui Nazarian, and Matthew Fruzza for their valuable technical support and Trent Wenzel for his useful additions to the Axograph analysis package. Supported by USPHS grants MH 43362, NS 09999, NS 23426, AGO 4307, HL 60296.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Acuna-Goycolea C, van den Pol AN. Neuroendocrine proopiomelanocortin neurons are excited by hypocretin/orexin. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1503–1513. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5147-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amatruda TT, III, Black DA, McKenna TM, McCarley RW, Hobson JA. Sleep cycle control and cholinergic mechanisms: differential effects of carbachol injections at pontine brain stem sites. Brain Res. 1975;98:501–515. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90369-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anand BK, Chhina GS, Singh B. Effect of glucose on the activity of hypothalamic “feeding centers”. Science. 1962;138:597–598. doi: 10.1126/science.138.3540.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baghdoyan HA, Rodrigo-Angulo ML, McCarley RW, Hobson JA. Site-specific enhancement and suppression of desynchronized sleep signs following cholinergic stimulation of three brainstem regions. Brain Res. 1984;306:39–52. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baghdoyan HA, Rodrigo-Angulo ML, McCarley RW, Hobson JA. A neuroanatomical gradient in the pontine tegmentum for the cholinoceptive induction of desynchronized sleep signs. Brain Res. 1987;414:245–261. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baghdoyan HA, Spotts JL, Snyder SG. Simultaneous pontine and basal forebrain microinjections of carbachol suppress REM sleep. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:229–242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00229.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandler R, Fatouris D. Centrally elicited attack behavior in cats: post-stimulus excitability and midbrain-hypothalamic inter-relationships. Brain Res. 1978;153:427–433. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berman AL. The brainstem of the cat A cytoarchitectonic atlas with stereotaxic coordinates. The University of Wisconsin Press; Madison, Milwaukee: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman AL, Jones EG. The thalamus and basal telencephalon of the cat A cytoarchitectonic atlas with stereotaxic coordinates. The University of Wisconsin Press; Madison, Milwaukee: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourgin P, Huitron-Resendiz S, Spier AD, Fabre V, Morte B, Criado JR, Sutcliffe JG, Henriksen SJ, de Lecea L. Hypocretin-1 modulates rapid eye movement sleep through activation of locus coeruleus neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7760–7765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07760.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boutrel B, Kenny PJ, Specio SE, Martin-Fardon R, Markou A, Koob GF, de Lecea L. Role for hypocretin in mediating stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:19168–19173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507480102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burlet S, Tyler CJ, Leonard CS. Direct and indirect excitation of laterodorsal tegmental neurons by Hypocretin/Orexin peptides: implications for wakefulness and narcolepsy. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2862–2872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02862.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chase MH, Monoson R, Watanabe K, Babb MI. Somatic reflex response-reversal of reticular origin. Exp Neurol. 1976;50:561–567. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(76)90026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chase MH, Morales FR. Subthreshold excitatory activity and motoneuron discharge during REM periods of active sleep. Science. 1983;221:1195–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.6310749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chase MH, Morales FR. The control of motoneurons during sleep. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Saunders; New York: 2005. pp. 154–168. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chase MH, Morales FR, Boxer PA, Fung SJ, Soja PJ. Effect of stimulation of the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis on the membrane potential of cat lumbar motoneurons during sleep and wakefulness. Brain Res. 1986;386:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chase MH, Soja PJ, Morales FR. Evidence that glycine mediates the postsynaptic potentials that inhibit lumbar motoneurons during the atonia of active sleep. J Neurosci. 1989;9:743–751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-03-00743.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chirwa SS, Stafford-Segert I, Soja PJ, Chase MH. Strychnine antagonizes jaw-closer motoneuron IPSPs induced by reticular stimulation during active sleep. Brain Research. 1991;547:323–326. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90979-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curro Dossi R, Pare D, Steriade M. Short-lasting nicotinic and long-lasting muscarinic depolarizing responses of thalamocortical neurons to stimulation of mesopontine cholinergic nuclei. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65:393–406. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsukura S. A role for orexins and melanin-concentrating hormone in the central regulation of feeding behavior. Nippon Rinsho. 2001;59:427–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Date Y, Ueta Y, Yamashita H, Yamaguchi H, Matsukura S, Kangawa K, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Nakazato M. Orexins, orexigenic hypothalamic peptides, interact with autonomic, neuroendocrine and neuroregulatory systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:748–753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dauvilliers Y, Rompre S, Gagnon JF, Vendette M, Petit D, Montplaisir J. REM sleep characteristics in narcolepsy and REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2007;30:844–849. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.7.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, 2nd, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dergacheva O, Wang X, Huang ZG, Bouairi E, Stephens C, Gorini C, Mendelowitz D. Hypocretin-1 (orexin-A) facilitates inhibitory and diminishes excitatory synaptic pathways to cardiac vagal neurons in the nucleus ambiguus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1322–1327. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.086421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dube MG, Kalra SP, Kalra PS. Food intake elicited by central administration of orexins/hypocretins: identification of hypothalamic sites of action. Brain Res. 1999;842:473–477. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01824-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dun NJ, Le Dun S, Chen CT, Hwang LL, Kwok EH, Chang JK. Orexins: a role in medullary sympathetic outflow. Regul Pept. 2000;96:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dutschmann M, Herbert H. Pontine cholinergic mechanisms enhance trigeminally evoked respiratory suppression in the anesthetized rat. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1999;87:1059–1065. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.3.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards CM, Abusnana S, Sunter D, Murphy KG, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. The effect of the orexins on food intake: comparison with neuropeptide Y, melanin-concentrating hormone and galanin. J Endocrinol. 1999;160:R7–12. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.160r007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eriksson KS, Sergeeva O, Brown RE, Haas HL. Orexin/hypocretin excites the histaminergic neurons of the tuberomammillary nucleus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9273–9279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09273.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenik V, Marchenko V, Janssen P, Davies RO, Kubin L. A5 cells are silenced when REM sleep-like signs are elicited by pontine carbachol. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1448–1456. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00225.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuentealba P, Crochet S, Timofeev I, Steriade M. Synaptic interactions between thalamic and cortical inputs onto cortical neurons in vivo. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1990–1998. doi: 10.1152/jn.01105.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fung SJ, Barnes CD. Membrane excitability changes in hindlimb motoneurons induced by stimulation of the locus coeruleus in cats. Brain Research. 1987;402:230–242. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fung SJ, Boxer PA, Morales FR, Chase MH. Hyperpolarizing membrane responses induced in lumbar motoneurons by stimulation of the nucleus reticularis pontis oralis during active sleep. Brain Res. 1982;248:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fung SJ, Yamuy J, Sampogna S, Morales FR, Chase MH. Hypocretin (orexin) input to trigeminal and hypoglossal motoneurons in the cat: a double-labeling immunohistochemical study. Brain Res. 2001;903:257–262. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fung SJ, Yamuy J, Xi MC, Engelhardt JK, Morales FR, Chase MH. Changes in electrophysiological properties of cat hypoglossal motoneurons during carbachol-induced motor inhibition. Brain Res. 2000;885:262–272. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02955-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao XB, van den Pol AN. Melanin concentrating hormone depresses synaptic activity of glutamate and GABA neurons from rat lateral hypothalamus. J Physiol. 2001;533:237–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0237b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.George R, Haslett W, Jenden D. A cholinergic mechanism in the brainstem reticular formation: induction of paradoxical sleep. Int J Pharmacol. 1964;3:541–552. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(64)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffond B, Risold PY, Jacquemard C, Colard C, Fellmann D. Insulin-induced hypoglycemia increases preprohypocretin (orexin) mRNA in the rat lateral hypothalamic area. Neurosci Lett. 1999;262:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00976-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmes CJ, Jones BE. Importance of cholinergic, GABAergic, serotonergic and other neurons in the medial medullary reticular formation for sleep-wake states studied by cytotoxic lesions in the cat. Neuroscience. 1994;62:1179–1200. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmes CJ, Mainville LS, Jones BE. Distribution of cholinergic, GABAergic and serotonergic neurons in the medial medullary reticular formation and their projections studied by cytotoxic lesions in the cat. Neuroscience. 1994;62:1155–1178. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horner RL, Kubin L. Pontine carbachol elicits multiple rapid eye movement sleep-like neural events in urethane-anaesthetized rats. Neuroscience. 1999;93:215–226. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horvath TL, Diano S, van den Pol AN. Synaptic interaction between hypocretin (orexin) and neuropeptide Y cells in the rodent and primate hypothalamus: a novel circuit implicated in metabolic and endocrine regulations. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1072–1087. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-03-01072.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johansson L, Ekholm ME, Kukkonen JP. Regulation of OX1 orexin/hypocretin receptor-coupling to phospholipase C by Ca2+ influx. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:97–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones BE. Immunohistochemical study of choline acetyltransferase-immunoreactive processes and cells innervating the pontomedullary reticular formation in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;295:485–514. doi: 10.1002/cne.902950311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones BE. The role of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons and neighboring cholinergic neurons of the pontomesencephalic tegmentum in sleep-wake states. Prog Brain Res. 1991;88:533–543. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63832-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones BE. From waking to sleeping: neuronal and chemical substrates. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kilduff TS. Hypocretin/orexin: maintenance of wakefulness and a multiplicity of other roles. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kiyashchenko LI, Mileykovskiy BY, Lai YY, Siegel JM. Increased and decreased muscle tone with orexin (hypocretin) microinjections in the locus coeruleus and pontine inhibitory area. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2008–2016. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiyashchenko LI, Mileykovskiy BY, Maidment N, Lam HA, Wu MF, John J, Peever J, Siegel JM. Release of hypocretin (orexin) during waking and sleep states. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5282–5286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05282.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kohlmeier KA, Inoue T, Leonard CS. Hypocretin/orexin peptide signaling in the ascending arousal system: elevation of intracellular calcium in the mouse dorsal raphe and laterodorsal tegmentum. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:221–235. doi: 10.1152/jn.00076.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kohlmeier KA, Lopez-Rodriguez F, Chase MH. Strychnine blocks inhibitory postsynaptic potentials elicited in masseter motoneurons by sensory stimuli during carbachol-induced motor atonia. Neuroscience. 1997;78:1195–1202. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kohlmeier KA, Lopez-Rodriguez F, Liu RH, Morales FR, Chase MH. State-dependent phenomena in cat masseter motoneurons. Brain Res. 1996;722:30–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kohlmeier KA, Lopez-Rodriguez F, Morales FR, Chase MH. Effects of excitation of sensory pathways on the membrane potential of cat masseter motoneurons before and during cholinergically induced motor atonia. Neuroscience. 1998;86:557–569. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuru M, Ueta Y, Serino R, Nakazato M, Yamamoto Y, Shibuya I, Yamashita H. Centrally administered orexin/hypocretin activates HPA axis in rats. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1977–1980. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200006260-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lai YY, Clements JR, Wu XY, Shalita T, Wu JP, Kuo JS, Siegel JM. Brainstem projections to the ventromedial medulla in cat: retrograde transport horseradish peroxidase and immunohistochemical studies. J Comp Neurol. 1999;408:419–436. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990607)408:3<419::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee MG, Hassani OK, Jones BE. Discharge of identified orexin/hypocretin neurons across the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6716–6720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1887-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Y, Gao XB, Sakurai T, van den Pol AN. Hypocretin/Orexin excites hypocretin neurons via a local glutamate neuron-A potential mechanism for orchestrating the hypothalamic arousal system. Neuron. 2002;36:1169–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lopez-Rodriguez F, Kohlmeier KA, Yamuy J, Morales FR, Chase MH. Muscle atonia can be induced by carbachol injections into the nucleus pontis oralis in cats anesthetized with alpha-chloralose. Brain Res. 1995;699:201–207. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00899-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu JW, Fenik VB, Branconi JL, Mann GL, Rukhadze I, Kubin L. Disinhibition of perifornical hypothalamic neurones activates noradrenergic neurones and blocks pontine carbachol-induced REM sleep-like episodes in rats. J Physiol. 2007;582:553–567. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.127613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma X, Zubcevic L, Bruning JC, Ashcroft FM, Burdakov D. Electrical inhibition of identified anorexigenic POMC neurons by orexin/hypocretin. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1529–1533. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3583-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marks GA, Birabil CG. Enhancement of rapid eye movement sleep in the rat by cholinergic and adenosinergic agonists infused into the pontine reticular formation. Neuroscience. 1998;86:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McGregor R, Damian A, Fabbiani G, Torterolo P, Pose I, Chase M, Morales FR. Direct hypothalamic innervation of the trigeminal motor nucleus: a retrograde tracer study. Neuroscience. 2005;136:1073–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mileykovskiy BY, Kiyashchenko LI, Siegel JM. Behavioral correlates of activity in identified hypocretin/orexin neurons. Neuron. 2005;46:787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Modirrousta M, Mainville L, Jones BE. Orexin and MCH neurons express c-Fos differently after sleep deprivation vs. recovery and bear different adrenergic receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2807–2816. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morales F, Chase MH. Postsynaptic control of lumbar motoneuron excitability during active sleep in the chronic cat. Brain Res. 1981;225:279–295. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90836-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morales FR, Boxer P, Chase MH. Behavioral state-specific inhibitory postsynaptic potentials impinge on cat lumbar motoneurons during active sleep. Exp Neurol. 1987;98:418–435. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(87)90252-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morales FR, Chase MH. Intracellular recording of lumbar motoneuron membrane potential during sleep and wakefulness. Exp Neurol. 1978;62:821–827. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(78)90289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morales FR, Chase MH. Repetitive synaptic potentials responsible for inhibition of spinal cord motoneurons during active sleep. Exp Neurol. 1982;78:471–476. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(82)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morales FR, Engelhardt JK, Soja PJ, Pereda AE, Chase MH. Motoneuron properties during motor inhibition produced by microinjection of carbachol into the pontine reticular formation of the decerebrate cat. J Neurophysiol. 1987;57:1118–1129. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.57.4.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morales FR, Sampogna S, Rampon C, Luppi PH, Chase MH. Brainstem glycinergic neurons and their activation during active (rapid eye movement) sleep in the cat. Neuroscience. 2006;142:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morales FR, Schadt J, Chase MH. Intracellular recording from spinal cord motoneurons in the chronic cat. Physiol Behav. 1981;27:355–362. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90280-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morgane PJ. Distinct “feeding” and “hunger motivating” systems in the lateral hypothalamus of the rat. Science. 1961;133:887–888. doi: 10.1126/science.133.3456.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nakamura T, Uramura K, Nambu T, Yada T, Goto K, Yanagisawa M, Sakurai T. Orexin-induced hyperlocomotion and stereotypy are mediated by the dopaminergic system. Brain Res. 2000;873:181–187. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nosaka S. Modifications of arterial baroreflexes: obligatory roles in cardiovascular regulation in stress and poststress recovery. Jpn J Physiol. 1996;46:271–288. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.46.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ono K, Kai A, Honda E, Inenaga K. Hypocretin-1/orexin-A activates subfornical organ neurons of rats. Neuroreport. 2008;19:69–73. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f32d64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peever JH, Lai YY, Siegel JM. Excitatory effects of hypocretin-1 (orexin-A) in the trigeminal motor nucleus are reversed by NMDA antagonism. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2591–2600. doi: 10.1152/jn.00968.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pereda AE, Morales FR, Chase MH. Medullary control of lumbar motoneurons during carbachol-induced motor inhibition. Brain Res. 1990;514:175–179. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90455-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rodrigo-Angulo ML, Rodriguez-Veiga E, Reinoso-Suarez F. Serotonergic connections to the ventral oral pontine reticular nucleus: implication in paradoxical sleep modulation. J Comp Neurol. 2000;418:93–105. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000228)418:1<93::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richarson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:1–696. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)09256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Samson WK, Gosnell B, Chang JK, Resch ZT, Murphy TC. Cardiovascular regulatory actions of the hypocretins in brain. Brain Res. 1999;831:248–253. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. Motor dyscontrol in narcolepsy: rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep without atonia and REM sleep behavior disorder. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:3–10. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Semba K. Aminergic and cholinergic afferents to REM sleep induction regions of the pontine reticular formation in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;330:543–556. doi: 10.1002/cne.903300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Semba K, Reiner PB, Fibiger HC. Single cholinergic mesopontine tegmental neurons project to both the pontine reticular formation and the thalamus in the rat. Neuroscience. 1990;38:643–654. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90058-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shammah-Lagnado SJ, Negrao N, Silva BA, Ricardo JA. Afferent connections of the nuclei reticularis pontis oralis and caudalis: a horseradish peroxidase study in the rat. Neuroscience. 1987;20:961–989. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shiromani PJ, Kilduff TS, Bloom FE, McCarley RW. Cholinergically induced REM sleep triggers Fos-like immunoreactivity in dorsolateral pontine regions associated with REM sleep. Brain Research. 1992;580:351–357. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90968-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shiromani PJ, McGinty DJ. Pontine neuronal response to local cholinergic infusion: relation to REM sleep. Brain Res. 1986;386:20–31. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Siegel J. REM sleep. In: Kryger MK, TR, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Saunders; New York: 2005. pp. 120–135. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Siegel JM. Hypocretin (orexin): role in normal behavior and neuropathology. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:125–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Siegel JM, McGinty DJ. Pontine reticular formation neurons: relationship of discharge to motor activity. Science. 1977;196:678–680. doi: 10.1126/science.193185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Siegel JM, Nienhuis R, Tomaszewski KS. Rostral brainstem contributes to medullary inhibition of muscle tone. Brain Res. 1983;268:344–348. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90501-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Smith BN, Davis SF, Van Den Pol AN, Xu W. Selective enhancement of excitatory synaptic activity in the rat nucleus tractus solitarius by hypocretin 2. Neuroscience. 2002;115:707–714. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00488-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Soja PJ, Lopez-Rodriguez F, Morales FR, Chase MH. The postsynaptic inhibitory control of lumbar motoneurons during the atonia of active sleep: effect of strychnine on motoneuron properties. J Neurosci. 1991;11:2804–2811. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-09-02804.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Soja PJ, López-Rodríguez F, Morales FR, Chase MH. The postsynaptic inhibitory control of lumbar motoneurons during the atonia of active sleep: effect of strychnine on motoneuron properties. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:2804–2811. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-09-02804.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Soja PJ, López-Rodríguez F, Morales FR, Chase MH. Effects of excitatory amino acid antagonists on the phasic depolarizing events that occur in lumbar motoneurons during REM periods of active sleep. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:4068–4076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-04068.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Soja PJ, Morales FR, Baranyi A, Chase MH. Effect of inhibitory amino acid antagonists on IPSPs induced in lumbar motoneurons upon stimulation of the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis during active sleep. Brain Res. 1987;423:353–358. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90862-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Soja PJ, Morales FR, Chase MH. Postsynaptic control of lumbar motoneurons during the atonia of active sleep. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1990;345:9–21. discussion 21-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sutcliffe JG, de Lecea L. The hypocretins: excitatory neuromodulatory peptides for multiple homeostatic systems, including sleep and feeding. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:161–168. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001015)62:2<161::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Takahashi K, Lin JS, Sakai K. Neuronal activity of orexin and non-orexin waking-active neurons during wake-sleep states in the mouse. Neuroscience. 2008;153:860–870. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Thakkar MM, Ramesh V, Strecker RE, McCarley RW. Microdialysis perfusion of orexin-A in the basal forebrain increases wakefulness in freely behaving rats. Arch Ital Biol. 2001;139:313–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Torterolo P, Sampogna S, Morales FR, Chase MH. MCH-containing neurons in the hypothalamus of the cat: searching for a role in the control of sleep and wakefulness. Brain Res. 2006;1119:101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Torterolo P, Yamuy J, Sampogna S, Morales FR, Chase MH. Hypothalamic neurons that contain hypocretin (orexin) express c-fos during active wakefulness and carbachol-induced active sleep. Sleep Res Online. 2001:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Torterolo P, Yamuy J, Sampogna S, Morales FR, Chase MH. Hypocretinergic neurons are primarily involved in activation of the somatomotor system. Sleep. 2003;26:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.van den Pol AN. Hypothalamic hypocretin (orexin): robust innervation of the spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3171–3182. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-03171.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]