Abstract

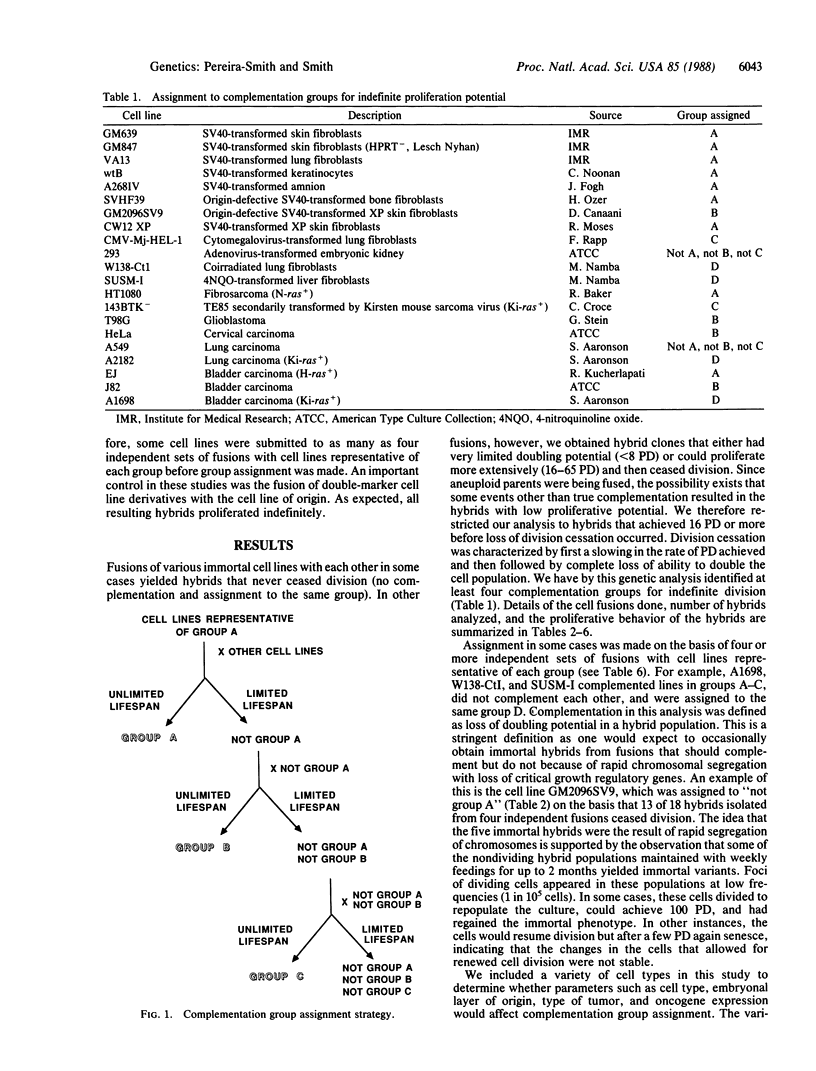

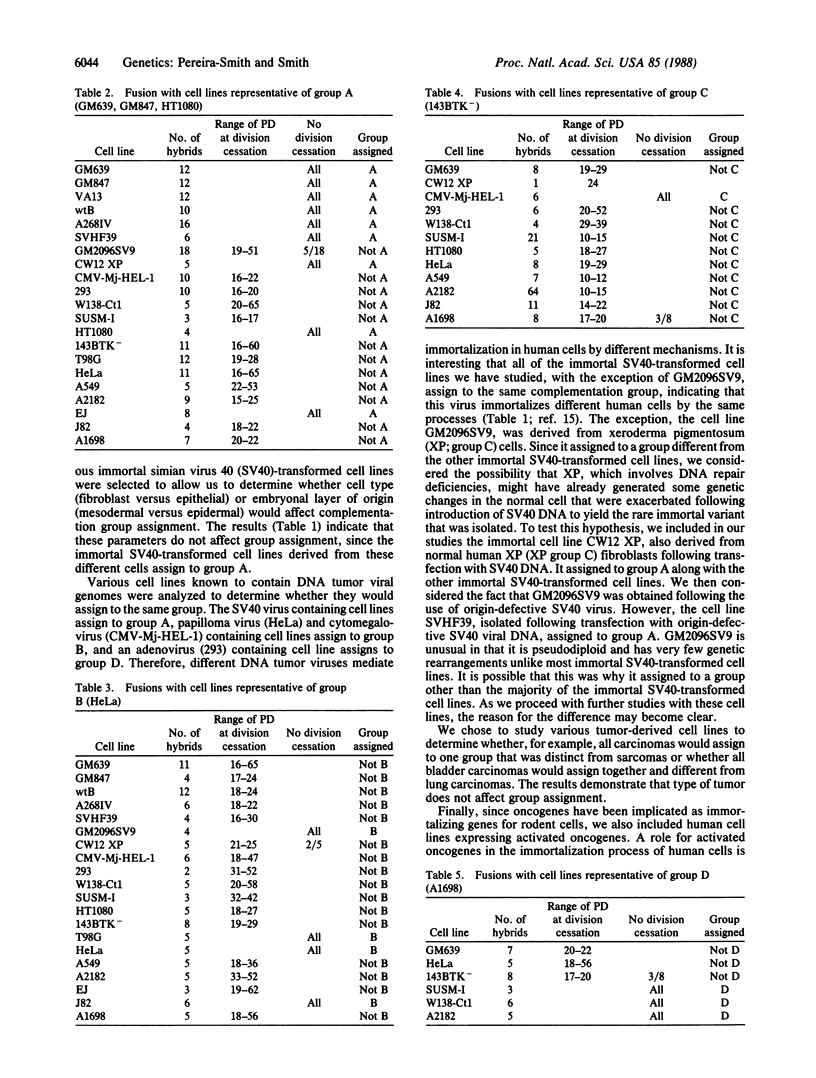

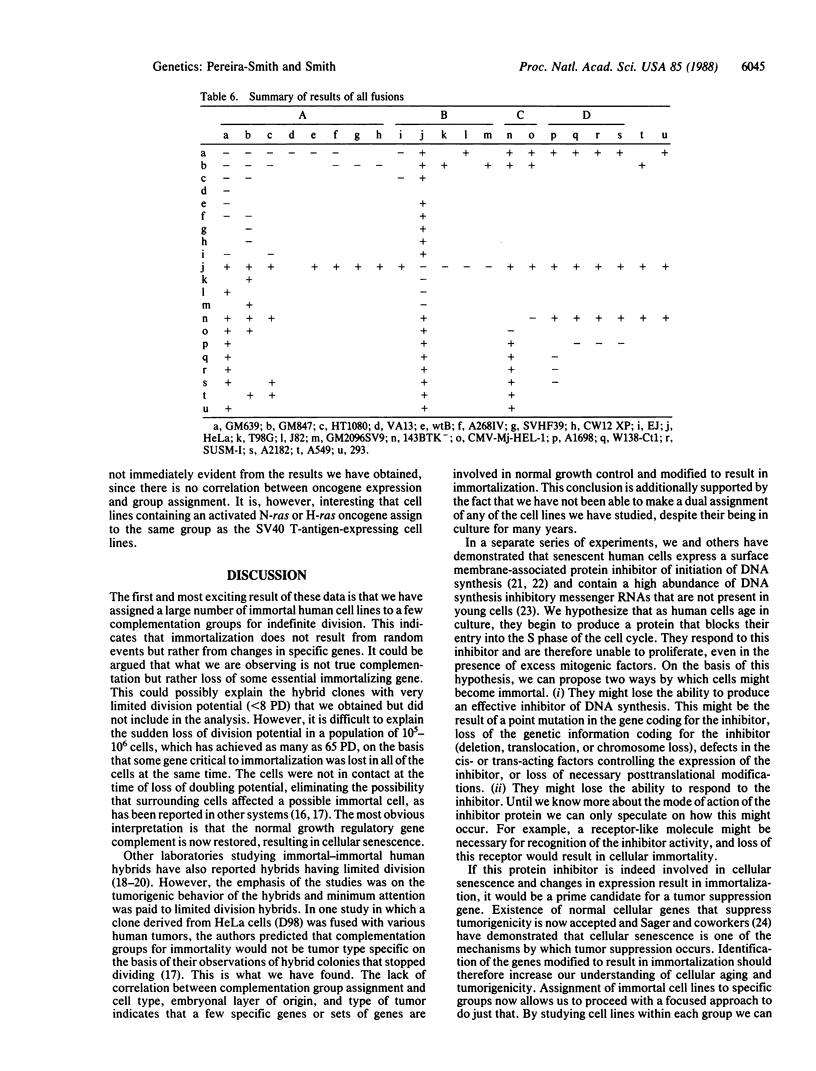

Hybrids obtained following fusion of normal human diploid fibroblasts with different immortal human cell lines exhibited limited division potential. This led to the conclusion that the phenotype of cellular senescence is dominant and that immortal cells arise as a result of recessive changes in the growth control mechanisms of the normal cell. We have exploited the fact that immortality is recessive and, by fusing immortal human cell lines with each other, assigned 21 cell lines to at least four complementation groups for indefinite division. A wide variety of cell lines was included in the study to determine what parameters, if any, would affect complementation group assignment. The results indicate that cell type, embryonal layer of origin, and type of tumor do not affect group assignment. There does not appear to be any correlation between expression of an activated oncogene and group assignment. However, all of the immortal simian virus 40-transformed cell lines studied (with the exception of one xerodermapigmentosum fibroblast-derived line) assign to the same group, indicating that this virus immortalizes various human cells by the same processes. The assignment of immortal human cells to distinct groups provides the basis for a focused approach to determine the genes important in normal growth regulation that have been modified in immortal cells.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blasi E., Mathieson B. J., Varesio L., Cleveland J. L., Borchert P. A., Rapp U. R. Selective immortalization of murine macrophages from fresh bone marrow by a raf/myc recombinant murine retrovirus. Nature. 1985 Dec 19;318(6047):667–670. doi: 10.1038/318667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn C. L., Tarrant G. M. Limited lifespan in somatic cell hybrids and cybrids. Exp Cell Res. 1980 Jun;127(2):385–396. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(80)90443-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forest C., Czerucka D., Negrel R., Ailhaud G. Establishment of a human cell line after transformation by a plasmid containing the early region of the SV40 genome. Cell Biol Int Rep. 1983 Jan;7(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(83)90106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIRARDI A. J., JENSEN F. C., KOPROWSKI H. SV40-INDUCED TRANFORMATION OF HUMAN DIPLOID CELLS: CRISIS AND RECOVERY. J Cell Physiol. 1965 Feb;65:69–83. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030650110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney E. V., Fogh J., Ramos L., Loveless J. D., Fogh H., Dowling A. M. Established lines of SV40-transformed human amnion cells. Cancer Res. 1970 Jun;30(6):1668–1676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh S., Gelb L., Schlessinger D. SV40-transformed human diploid cells that remain transformed throughout their limited lifespan. J Gen Virol. 1979 Feb;42(2):409–414. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-42-2-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYFLICK L. THE LIMITED IN VITRO LIFETIME OF HUMAN DIPLOID CELL STRAINS. Exp Cell Res. 1965 Mar;37:614–636. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide T., Tsuji Y., Ishibashi S., Mitsui Y. Reinitiation of host DNA synthesis in senescent human diploid cells by infection with Simian virus 40. Exp Cell Res. 1983 Feb;143(2):343–349. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(83)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood T. B., Holliday R. Commitment to senescence: a model for the finite and infinite growth of diploid and transformed human fibroblasts in culture. J Theor Biol. 1975 Sep;53(2):481–496. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(75)80018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LITTLEFIELD J. W. SELECTION OF HYBRIDS FROM MATINGS OF FIBROBLASTS IN VITRO AND THEIR PRESUMED RECOMBINANTS. Science. 1964 Aug 14;145(3633):709–710. doi: 10.1126/science.145.3633.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land H., Chen A. C., Morgenstern J. P., Parada L. F., Weinberg R. A. Behavior of myc and ras oncogenes in transformation of rat embryo fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Jun;6(6):1917–1925. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.6.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomax C. A., Bradley E., Weber J., Bourgaux P. Transformation of human cells by temperature-sensitive mutants of simian virus-40. Intervirology. 1978;9(1):28–38. doi: 10.1159/000148918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin C. K., Jr, McClung J. K., Pereira-Smith O. M., Smith J. R. Existence of high abundance antiproliferative mRNA's in senescent human diploid fibroblasts. Science. 1986 Apr 18;232(4748):393–395. doi: 10.1126/science.2421407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOYER A. W., WALLACE R., COX H. R. LIMITED GROWTH PERIOD OF HUMAN LUNG CELL LINES TRANSFORMED BY SIMIAN VIRUS 40. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1964 Aug;33:227–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G. M., Sprague C. A., Norwood T. H., Pendergrass W. R., Bornstein P., Hoehn H., Arend W. P. Do hyperplastoid cell lines "differentiate themselves to death"? Adv Exp Med Biol. 1975;53:67–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muggleton-Harris A. L., DeSimone D. W. Replicative potentials of various fusion products between WI-38 and SV40 transformed WI-38 cells and their components. Somatic Cell Genet. 1980 Nov;6(6):689–698. doi: 10.1007/BF01538968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien W., Stenman G., Sager R. Suppression of tumor growth by senescence in virally transformed human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Nov;83(22):8659–8663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell R. W., Leary J. F., Penney D. P., Budd H. S., Marquis D. M., Spennacchio J. L., Henshaw E. C., McCune C. S. Somatic cell hybridization of human tumor samples. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1984 Mar;10(2):195–204. doi: 10.1007/BF01534908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORGEL L. E. The maintenance of the accuracy of protein synthesis and its relevance to ageing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1963 Apr;49:517–521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.49.4.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S., Nagai Y. Genes in multiple copies as the primary cause of aging. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1978;14(1):501–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima R. G., Pellett O. L., Robb J. A., Schneider J. A. Transformation of human cystinotic fibroblasts by SV40: characteristics of transformed cells with limited and unlimited growth potential. J Cell Physiol. 1977 Oct;93(1):129–136. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040930116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Smith O. M., Fisher S. F., Smith J. R. Senescent and quiescent cell inhibitors of DNA synthesis. Membrane-associated proteins. Exp Cell Res. 1985 Oct;160(2):297–306. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(85)90177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Smith O. M., Smith J. R. Evidence for the recessive nature of cellular immortality. Science. 1983 Sep 2;221(4614):964–966. doi: 10.1126/science.6879195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Smith O. M., Smith J. R. Expression of SV40 T antigen in finite life-span hybrids of normal and SV40-transformed fibroblasts. Somatic Cell Genet. 1981 Jul;7(4):411–421. doi: 10.1007/BF01542986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Smith O. M., Smith J. R. Functional simian virus 40 T antigen is expressed in hybrid cells having finite proliferative potential. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Apr;7(4):1541–1544. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.4.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Smith O. M., Smith J. R. Phenotype of low proliferative potential is dominant in hybrids of normal human fibroblasts. Somatic Cell Genet. 1982 Nov;8(6):731–742. doi: 10.1007/BF01543015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell W. C., Newman C., Williamson D. H. A simple cytochemical technique for demonstration of DNA in cells infected with mycoplasmas and viruses. Nature. 1975 Feb 6;253(5491):461–462. doi: 10.1038/253461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEIN H. M., ENDERS J. F., PALMER L., GROGAN E. FURTHER STUDIES ON SV40-INDUCED TRANSFORMATION IN HUMAN RENAL CELL CULTURES. I. EVENTUAL FAILURE OF SUBCULTIVATION DESPITE A CONTINUING HIGH RATE OF CELL DIVISION. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1964 Mar;115:618–621. doi: 10.3181/00379727-115-28986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. R., Lumpkin C. K., Jr Loss of gene repression activity: a theory of cellular senescence. Mech Ageing Dev. 1980;13(4):387–392. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(80)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanbridge E. J., Der C. J., Doersen C. J., Nishimi R. Y., Peehl D. M., Weissman B. E., Wilkinson J. E. Human cell hybrids: analysis of transformation and tumorigenicity. Science. 1982 Jan 15;215(4530):252–259. doi: 10.1126/science.7053574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein G. H., Atkins L. Membrane-associated inhibitor of DNA synthesis in senescent human diploid fibroblasts: characterization and comparison to quiescent cell inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Dec;83(23):9030–9034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.9030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg M. L., Defendi V. Altered pattern of growth and differentiation in human keratinocytes infected by simian virus 40. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Feb;76(2):801–805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.2.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman B. E., Stanbridge E. J. Complementation of the tumorigenic phenotype in human cell hybrids. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983 Apr;70(4):667–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]