Abstract

Cells produce proteases as inactive zymogens. Herein, we demonstrate that this tactic can extend beyond proteases. By linking the N- and C-termini of ribonuclease A, we obstruct the active site with the amino acid sequence recognized by plasmepsin II, a highly specific protease from Plasmodium falciparum. We generate new N- and C-termini by circular permutation. In the presence of plasmepsin II, a ribonuclease zymogen gains nearly 103-fold in catalytic activity and maintains high conformational stability. We conclude that zymogen creation provides a new and versatile strategy for the control of enzymatic activity, as well as the potential development of chemotherapeutic agents.

The cleavage of target proteins by proteases is critical for many biological processes1,2. Yet, the unbridled enzymatic activity of proteases can inflict catastrophic damage. Accordingly, proteolytic activity is under strict spatial and temporal control. This control is achieved by the binding of protease-inhibitor proteins as well as the biosynthesis and transport of proteases as inactive zymogens3–6. These zymogens are activated upon cleavage by other proteases, or in an autocatalytic manner.

Like proteases, ribonucleases manifest an enzymatic activity that can be cytotoxic7. In analogy to the control of proteolytic activity by protease-inhibitor proteins, ribonucleolytic activity is controlled by ribonuclease-inhibitor proteins8. The resulting complexes can have Kd values in the fM range, indicative of an evolutionary imperative to control ribonucleolytic activity. Surprisingly, however, no zymogens are known for ribonucleases. Here, we demonstrate that a ribonuclease can be transformed into a zymogen that unleashes its enzymatic activity only in the presence of a highly specific protease.

Zymogen design

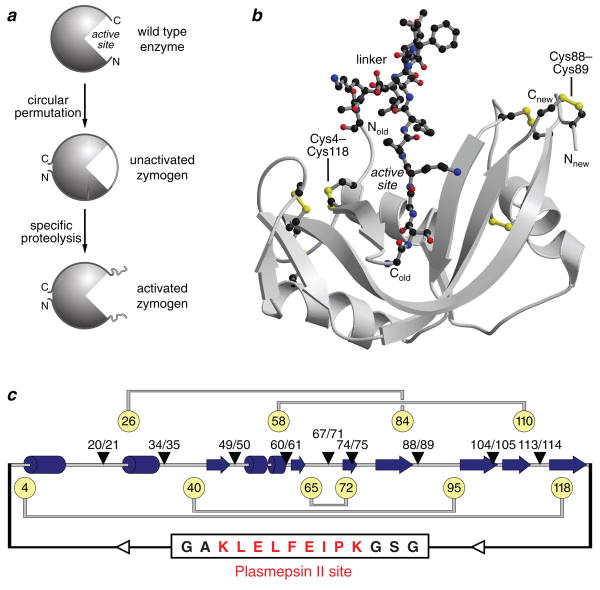

A functional zymogen must have two attributes. First, the enzymatic activity of the activated zymogen must be both high and much greater than that of the unactivated zymogen. Second, the zymogen must have high conformational stability, both before and after activation. We suspected that a zymogen of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease (RNase A9,10) could be both created and endowed with these attributes. Specifically, we envisioned that a bridge of amino acids connecting the original N- and C-termini would span the active site and interfere with the binding of substrate RNA (Fig. 1a,b). This bridge could contain the recognition sequence for a specific protease. New N- and C-termini could be created by circular permutation of the polypeptide chain11, which is a natural mechanism by which active sites migrate along a polypeptide chain12 and new protein folds evolve13.

Fig. 1.

Design of a ribonuclease zymogen. a, Scheme for creating a zymogen in which a circular permutation creates a steric block of the active site. b, Structural model of the unactivated ribonuclease A zymogen with 88/89 termini, 14-residue linker, and six disulfide bonds. The conformational energy of the non–wild-type residues was minimized with the program SYBYL. Atoms of the linker and cystines are shown explicitly, and the two nonnative cystines are labeled. c, Scheme of the primary sequence of ribonuclease A zymogens. The location of α-helices (cylinders) and β-strands (arrows) are indicated. The nine new termini, 14-residue linker, and four native and one nonnative (Cys4–Cys118) cystines are indicated.

The distance between the original N- and C-termini of RNase A is ca. 30 Å, which could be spanned by as few as 8 residues. A linker connecting the original N- and C-termini must, however, be long enough to leave intact the structure of RNase A and to allow access by a protease, but short enough to prevent the binding of substrate RNA. Our molecular modeling suggested that a linker of 14 residues would meet these criteria (Fig. 1b).

As a protease, we chose plasmepsin II14,15. This highly specific, aspartyl protease is produced by Plasmodium falciparum, which is responsible for most cases of malaria. The protease catalyzes the hydrolysis of the α33Phe–34Leu peptide bond in human hemoglobin16,17. Plasmepsin II itself is biosynthesized as a zymogen that is activated in vivo by another protease18,19.

The location of the new termini is crucial to the properties of a circular permutation. We selected nine sites for new termini (Fig. 1c). Each of these sites lies between different cysteine residues, so that each permuted protein has a distinct disulfide-bonding pattern. In addition, most of the new termini are in β-turns or surface loops, which are likely to be more tolerant of change than are α-helices or β-strands. We used the most stable known variant of RNase A as a template for our zymogen. This variant, A4C/V118C RNasez A, has all four native disulfide bonds plus a nonnative, fifth disulfide bond between an N- and C-terminal residue20.

Zymogen optimization

We produced each ribonuclease zymogen in Escherichia coli as an inclusion body, and then subjected each to oxidative folding in vitro21,22. Most of the nine zymogens—those with termini at residues 20/21, 67/71, 88/89, 104/105, and 113/114—were able to fold properly. These zymogens were purified by gel filtration and cation–exchange chromatography.

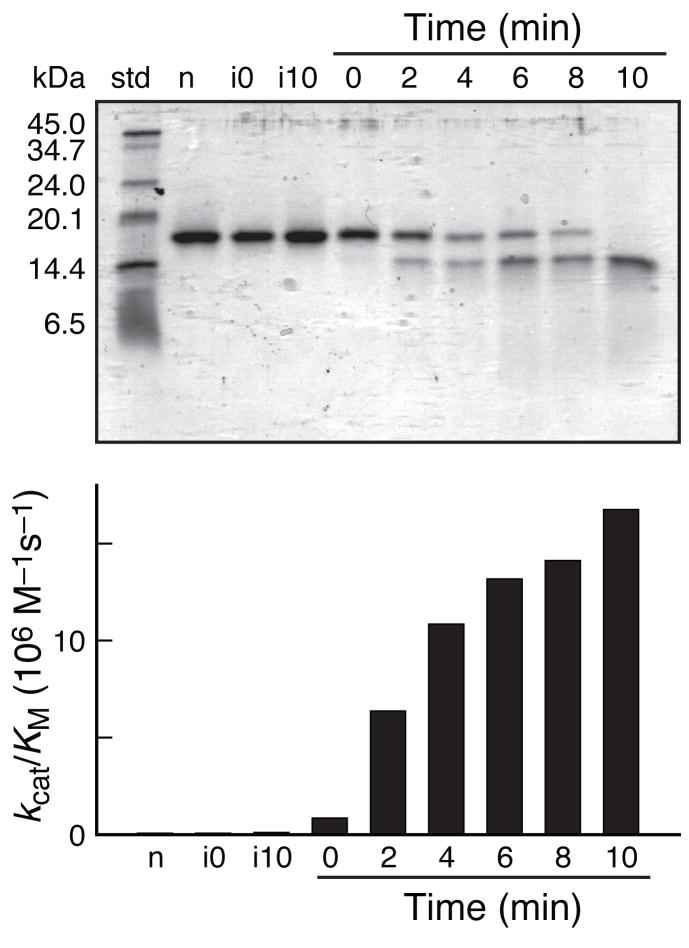

Treatment with plasmepsin II increased the ability of each ribonuclease zymogen to catalyze the cleavage of tetranucleotide substrate (Table 1). Apparently, the intact linker excludes even a small substrate from the active site. The relative activity of an activated and unactivated zymogen is likely to increase with a longer RNA substrate, or one with secondary structure. The increase in ribonucleolytic activity upon addition of plasmepsin II was rapid and catalytic (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Values of kcat/KM (103 M−1s−1) and Tm (°C) for wild-type ribonuclease A and zymogens with five disulfide bonds and various termini, before and after activation by plasmepsin II

Fig. 2.

Activation of ribonuclease A zymogen with 88/89 termini. Activation was monitored at different times after addition of plasmepsin II at a molar ratio of 1:100 (plasmepsin II:zymogen) by a, SDS–PAGE or b, ribonucleolytic activity. std, protein Mr standard; n, 0-min incubation without plasmepsin II; i0, 0-min incubation with unactivated plasmepsin II; i10, 10-min incubation with unactivated plasmepsin II.

The activated zymogens have dissimilar ribonucleolytic activity (Table 1), indicating that the location of the new termini can have a detrimental effect on catalysis. For example, the zymogen with 67/71 termini has a perturbation near a nucleobase-binding subsite10. The ribonucleolytic activity of that zymogen is low and increases by only 3-fold after activation by plasmepsin II. In contrast, the zymogen with 88/89 termini gains nearly 103-fold in activity, and has a kcat/KM value almost equal to that of wild-type RNase A. Residues 88 and 89 are remote from the active site (Fig. 1b) and have no known role in catalysis9,10. Moreover, the enzymatic activity of the zymogen with 88/89 termini did not increase in the presence of a HeLa cell extract (data not shown), which contains nonspecific proteases. Thus, activation requires specific proteolysis.

All of the ribonuclease zymogens had a Tm value that was greater than physiological temperature (37°C) but lower than that of the wild-type enzyme (62°C) (Table 1). Activation by plasmepsin II increased the value of Tm by 5–9°C. Such an increase in conformational stability after activation is a desirable characteristic. Less stable proteins are more susceptible to nonspecific proteolytic degradation23,20. Accordingly, the ribonuclease zymogens are likely to be degraded more quickly in the absence of their activating protease than in its presence.

The ideal zymogen should have low enzymatic activity before activation. All of the zymogens met this criterion (Table 1), as all have kcat/KM values <2 × 104 M−1s−1. Such low activity is of no known biological consequence for a variant of RNase A. For example, G88R RNase A has kcat/KM = 1.4 × 107 M−1s−1 and has well-characterized toxicity to human myelogenous leukemiacells22,24. In contrast, K41A/G88R RNase A has kcat/KM = 6.5 × 103 M−1s−1 and is not toxic to these cells24. Likewise, we find that the zymogen with 20/21 termini (which has kcat/KM = 1.02 × 104 M−1s−1 and Tm = 48°C Table 1) is not cytotoxic at concentrations up to 25 μM.

The ideal zymogen should also have high (that is, nearly wild-type) enzymatic activity after activation. The ribonuclease zymogen with 88/89 termini best met this criterion (Table 1). Hence, we subjected this zymogen to further modification.

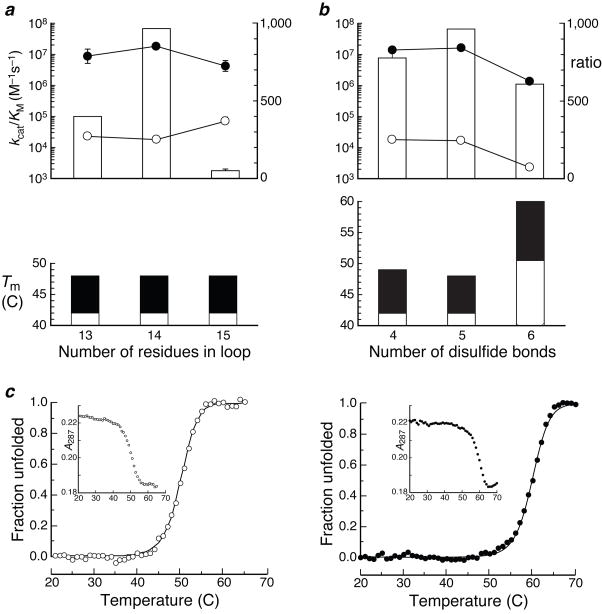

Decreasing the linker from 14 to 13 residues had little effect on the ribonucleolytic activity or conformational stability of the zymogen with 88/89 termini, either before or after activation (Fig. 3a). In contrast, increasing the linker from 14 to 15 residues had the undesirable effect of increasing the ribonucleolytic activity before plasmepsin II activation. This finding validates our concern that a long linker could allow a substrate greater access to the active site.

Fig. 3.

Optimization of ribonuclease A zymogen. a, Effect of linker length of ribonucleolytic activity and conformational stability of ribonuclease A zymogen with 88/89 termini, before (open) and after (filled) activation by plasmepsin II. Zymogens have linkers of 13 (GS–KPIEFLELK–AG), 14 (GSG–KPIEFLELK–AG), or 15 (GSG–KPIEFLELK–GAG) residues34. b, Effect of number of disulfide bonds on the ribonucleolytic activity and conformational stability of ribonuclease A zymogen with 88/89 termini, before (open) and after (filled) activation by plasmepsin II. Zymogens have four (native), five (native plus Cys4–Cys118), or six (native plus Cys4–Cys118 and Cys88–Cys89) disulfide bonds. c, Thermal unfolding of ribonuclease A zymogen with 88/89 termini and four native and two nonnative (Cys4–118 and Cys88–Cys89) disulfide bonds, before (left; Tm 50°C) and after (right; Tm 60°C) activation by plasmepsin II. Inserts: raw data from UV spectroscopy.

The introduction of a new disulfide bond that links the 88/89 termini increased the conformational stability of the zymogen. The Tm value of the zymogen with 88/89 termini and six disulfide bonds was 50°C before activation and 60°C after activation (Fig. 3b). This zymogen unfolded in a cooperative, two-state transition (Fig. 3c), as expected for a globular protein with a single domain. Accordingly, the protein depicted in Fig. 1b has all of the attributes associated with known zymogens, except that its activation yields a ribonuclease.

A zymogen as a precursor

Organisms could have created zymogens to control the activity of their non-proteolytic enzymes. The near absence of natural non-protease zymogens could indicate that creating a zymogen from an existing enzyme (Fig. 1a) is more difficult than evolving alternative mechanisms to control enzymatic activity. In addition, the unique ability of proteases to undergo autocatalytic activation could facilitate the evolution of protease zymogens, but not zymogens of other enzymes.

Zymogen creation provides a versatile option for the control of enzymatic activity. This strategy avails new applications for enzymes in biotechnology and medicine. For example, a “Trojan horse” based on a ribonuclease zymogen could have pharmacological utility. RNase A can enter human cells, and that process is enhanced by the fusion of a protein transduction domain25. Simple variants of both RNase A22,26 and its human homolog27 are toxic to cancer cells in vitro. An amphibian homolog, Onconase®, is now in Phase III clinical trials for the treatment of malignant mesothelioma7,28. RNase A zymogens activated by pathogenic proteases could extend the chemotherapeutic utility of ribonucleases to maladies other than cancer. Such a chemotherapeutic strategy, which relies on the function of an enzyme rather than its inhibition, could evade known mechanisms of microbial resistance.

Methods

Materials

E. coli strains BL21(DE3) and BL21(DE3) pLysS were from Novagen (Madison, WI). E. coli strain DH 5-αwas from Life Technologies. A plasmid encoding A4C/G88R/V118C RNase A was described previously20. All restriction endonucleases were from Promega (Madison, WI) or New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Pfu DNA polymerase was from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Taq DNA polymerase and RI were from Promega. A plasmid encoding plasmepsin II was a generous gift of B. M. Dunn (University of Florida, Gainesville, FL)29.

Purified oligonucleotides and the fluorogenic substrate 6-carboxyfluorescein–dArU(dA)2–6-TAMRA (6-FAM–dArU(dA)2–6-TAMRA) were from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). DNA sequences were determined with a Big Dye kit, FS from Perkin-Elmer (Foster City, CA), PTC-100 programmable thermal controller from MJ Research (Watertown, MA), and 373XL automated sequencer from Applied Biostystems (Foster City, CA) at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center.

Media were prepared in distilled water and autoclaved. Terrific broth medium contained (in 1 liter) Bacto tryptone (12 g), Bacto yeast extract (24 g), glycerol (4 ml), KH2PO4 (2.31 g), and K2HPO4 (12.54 g). M9 minimal medium contained (in 1 liter) Na2HPO4 · 7H2O (12.8 g), KH2PO4 (3.0 g), NaCl (12.8 g), NH4Cl (12.8 g), MgSO4 (0.5 g), and CaCl2 (0.5 g). PBS contained (in 1 liter) KCl (0.20 g), KH2PO4 (0.20 g), NaCl (8.0 g), and Na2HPO4 · 7H2O (2.16 g).

Instrumentation

UV absorbance measurements were made on a Cary Model 3 or 50 spectrophotometer from Varian (Palo Alto, CA) equipped with a Cary temperature controller. Fluorescence measurements were made on a QuantaMaster1 photon-counting fluorometer from Photon Technology International (South Brunswick, NJ) equipped with sample stirring.

Molecular modeling

The atomic coordinates of wild-type RNase A were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (accession code 7RSA30). A model of the structure of each RNase A zymogen was created by using the program SYBYL from Tripos (St. Louis, MO) on an Octane computer from Silicon Graphics (Mountain View, CA). The program was used to link the N- and C-termini by a bridge of 13–15 residues, replace residues (e.g., Ala4 and Val118 with a cystine), break the polypeptide chain in one of nine places, and minimize the conformational energy of the new residues in the resulting structures.

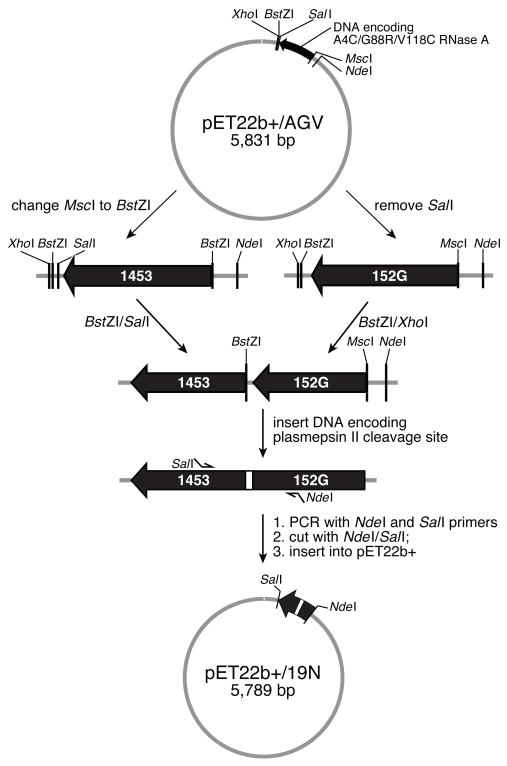

Preparation of zymogens

A scheme showing the construction of a plasmid pET22b+/19N, which directs the expression of an RNase A zymogen, is shown in Fig. 4. Plasmid pET22b+/AGV, which directs the expression of A4C/G88R/V118C RNase A20, served as the starting material. Hence, all of the RNase A zymogens (except those with termini at residues 88/89) had an arginine residue at position 88. G88R RNase A is able to manifest its ribonucleolytic activity in the presence of the cytosolic ribonuclease inhibitor protein22,20,26.

Fig. 4.

Scheme for the creation of plasmid that directs the expression of a ribonuclease A zymogen.

The MscI site in plasmid pET22b+/AGV was replaced with a BstZI site (underlined) by single-stranded DNA mutagenesis using the oligonucleotide 5′CAC AAG TTT CCT TGC CGG CCG CCG GCT GGG CAG CGA G 3′, resulting in plasmid p1453. The SalI site was removed by using the oligonucleotide 5′CCG CAA GCT TGT CGA GGA TCC CAC TGA AGC ATC AAA 3′, resulting in plasmid p152G. Plasmid p1453 was subjected to digestion with BstZI and SalI endonucleases, and a 385-bp fragment was purified after electrophoresis in an agarose gel. Plasmid p152G was subjected to restriction enzyme digestion with BstZI and XhoI endonucleases, and a 5805-bp fragment was purified. The two DNA fragments were ligated (XhoI and SalI digestion yield compatible cohesive ends), resulting in plasmid pSMFII. Plasmid pSMFII was then subjected to digestion with the BamHI and BstZI endonucleases, and a 6190-base pair fragment was purified. A phosphorylated double-stranded oligonucleotide encoding a plasmepsin II cleavage sequence within 13, 14, or 15 amino acid residues and having BstZI (italics) and BamHI (bold) compatible cohesive ends was ligated to the pSMFII/BstZI/BamHI fragment (5′ GAT CTA AAC CGA TTG AAT TTC TGG AAC TGA A 3′ and 5′ GGC CTT CAG TTC CAG AAA TTC AAT CGG TTT A 3′ for the 13-residue linker, 5′ GAT CTG GCA AAC CGA TTG AAT TTC TGG AAC TGA A 3′ and 5′ GGC CTT CAG TTC CAG AAA TTC AAT CGG TTT GCC A 3′ for the 14-residue linker, and 5′ GAT CTG GCA AAC CGA TTG AAT TTC TGG AAC TGG GCA A 3′ and 5′GGC CTT GCC CAG TTC CAG AAA TTC AAT CGG TTT GCC A 3′ for the 15-residue linker). Oligonucleotide primers corresponding to different new N-termini were engineered to have an NdeI-compatible cohesive end, and those corresponding to different new C-termini were engineered to have a SalI-compatible cohesive end. These pairs of primers were used in the PCR, and the resulting products were purified and subjected to digestion with the NdeI and SalI endonucleases. The resulting fragments were inserted into the NdeI and SalI sites of plasmid pET22b+, to produce plasmid pET22b+/19N (Fig. 4).

The Cys4–Cys118 cystine was removed from the circularly permuted RNase A with 88/89 termini by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis using oligonucleotides 5′ AAG GAA ACT GCA GCA GCC AAG TTT GAG CGG CAG C 3′ and 5′ GCT GCC GCT CAA ACT TGG CTG CTG CAG TTT CCT T 3′ to replace Cys4 with an alanine residue and 5′ GCA TCA AAG TGG ACT GGC ACG TAC GGG TTT CCC 3′ and 5′ GGG AAA CCC GTA CGT GCC AGT CCA CTT TGA TGC 3′ to replace Cys118 with a valine residue. Digestion with PstI endonuclease (bold) was used to screen for the C4A substitution; digestion with BsiWI endonuclease (italic) was used to screen for the C118V substitution.

The permuted RNase A with 88/89 termini and a sixth disulfide bond was created by PCR of plasmid pSMFII using oligonucleotide primers 5′ CGT GAG CAT ATG TGT TCC AAG TAC CCC 3′ and 5′ GTT GGG GTC GAC CTA CTA GCA CGT CTC ACG GCA GTC 3′ with the NdeI (bold) and SalI (italics) restriction sites. The PCR product was purified, digested with the NdeI and SalI endonucleases, and inserted into the NdeI and SalI sites of plasmid pET22b+. The resulting plasmid encodes a permuted variant with the eight native cysteine residues plus Cys4, Cys88, Cys89, and Cys118.

Oligonucleotides were annealed by dissolving them to 0.25 mM in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing NaCl (50 mM) and EDTA (1 mM). The resulting solution was heated to 95°C in a water bath and cooled slowly (over ≥4 h) to room temperature. The resulting double-stranded oligonucleotides were subjected to 5′-phosphorylation by treatment for 1 h with T4 polynucleotide kinase.

The production, folding, and purification of RNase A zymogens were done as described previously for other variants of RNase A22, except that the oxidative folding was done at pH 7.8 for at least 48 h.

Preparation of protease

The production, folding, and purification of proplasmepsin II were done as described previously31,21. Proplasmepsin II was activated by the addition of 1 μl of 1.0 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.7) to 9 μl of a solution of proplasmepsin II (10 μM in 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 8.0) and incubation of the resulting solution at 37°C for 45 min.

Activation of zymogens

RNase A zymogens were activated by mixing 19.5 μl of a solution of zymogen (25 μM) with 0.5 μl of a solution of activated plasmepsin II (10 μM), and incubating the resulting mixture at 37°C for 15 min. Activation was stopped by the addition of pepstatin A to a final concentration of 1 μM. To assess zymogen activation, reaction mixtures were subjected to electrophoresis in a 15% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; 1% w/v), and assayed for ribonucleolytic activity as described previously32.

Enzymatic activity of zymogens

The ribonucleolytic activity of RNase A zymogens was evaluated before and after activation with an assay based on a fluorogenic substrate32. Cleavage of 6-FAM–dArU(dA)2–6-TAMRA results in a nearly 200-fold increase in fluorescence intensity (excitation at 492 nm; emission at 515 nm). Assays were performed at 23 °C in 2.0 ml of 0.10 M MES–NaOH buffer (pH 6.0) containing NaCl (0.10 M), 6-FAM–dArU(dA)2–6-TAMRA (50 nM), and zymogen. Data were fitted to the equation: kcat/KM = (Δ I/Δ t)/{(If – I0)[E]} where ΔI/Δt is the initial velocity of the reaction, I0 is the fluorescence intensity prior to the addition of enzyme, If is the fluorescence intensity after complete hydrolysis with excess wild-type enzyme, and [E] is the ribonuclease concentration.

Cytotoxicity of zymogens

The toxicity of the unactivated zymogen with 20/21 termini to K-562 cells, which derive from a continuous human chronic myelogenous leukemia line, was assayed as described previously22.

Conformational stability of zymogens

The conformational stability of RNase A zymogens was assessed before and after activation by recording the change in absorbance at 287 nm with increasing temperature33. The temperature of a solution of RNase A zymogen (0.15–0.25 mg ml−1) in PBS was increased continuously from 20 to 70°C at 0.15°C min−1. The absorbance was recorded at 1-°C intervals and fitted to a two-state model for denaturation. The temperature at the midpoint of the transition is defined as Tm.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Park and D. H. Rich for contributive discussions, and B. M. Dunn for a plasmpesin II expression system. P. P. was supported by the Asian Partnership Initiative of Mahidol University and the University of Wisconsin–Madison. S. M. F. was supported by a Biotechnology Training Grant from the NIH. This work was supported by a grant to R. T. R. from the NIH.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Von Der Helm K, Korant BD, Cheronis JC, editors. Proteases as Targets for Therapy. Springer–Verlag; Heidelberg, Germany: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith J, Simons C. Proteinase and Peptidase Inhibition: Recent Potential Targets for Drug Development. Taylor & Francis; London, UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kühne W. Ueber die Verdauung der Eiweissstoffe durch den Pankreassaft. Virchows Arch. 1867;39:130–174. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan AR, James MNG. Molecular mechanisms for the conversion of zymogens to active proteolytic enzymes. Protein Sci. 1998;7:815–836. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laskowski M, Jr, Qasim MA, Lu SM. In: Protein–Protein Recognition. Kleanthous C, editor. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2000. pp. 228–279. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazure C. The peptidase zymogen proregions: Nature’s way of preventing undesired activation and proteolysis. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:509–529. doi: 10.2174/1381612023395691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leland PA, Raines RT. Cancer chemotherapy—ribonucleases to the rescue. Chem Biol. 2001;8:405–413. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00030-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleanthous C, Pommer AJ. In: Protein–Protein Recognition. Kleanthous C, editor. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2000. pp. 280–311. [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Alessio G, Riordan JF, editors. Ribonucleases: Structures and Functions. Academic Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raines RT. Ribonuclease A. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1045–1065. doi: 10.1021/cr960427h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldenberg DP, Creighton TE. Circular and circularly permuted forms of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor. J Mol Biol. 1983;165:407–413. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Todd AE, Orengo CA, Thornton JM. Plasticity of enzyme active sites. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:419–426. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grishin NV. Fold change in evolution of protein structures. J Struct Biol. 2001;134:167–185. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva AM, et al. Structure and inhibition of plasmepsin II, a hemoglobin-degrading enzyme from Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10034–10039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klemba M, Goldberg DE. Biological roles of proteases in parasitic protozoa. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;7:275–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.090501.145453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg DE, et al. Hemoglobin degradation in the human malaria pathogen Plasmodium falciparum: A catabolic pathway initiated by a specific aspartic protease. J Exp Med. 1991;173:961–969. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francis SE, Sullivan DJ, Jr, Goldberg DE. Hemoglobin metabolism in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:97–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francis SE, Banerjee R, Goldberg DE. Biosynthesis and maturation of the malaria aspartic hemoglobinases plasmepsins I and II. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14961–14968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernstein NK, Cherney MM, Loetscher H, Ridley RG, James MN. Crystal structure of the novel aspartic proteinase zymogen proplasmepsin II from Plasmodium falciparum. Nature Struct Biol. 1999;6:32–37. doi: 10.1038/4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klink TA, Raines RT. Conformational stability is a determinant of ribonuclease A cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17463–17467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001132200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.delCardayré SB, et al. Engineering ribonuclease A: Production, purification, and characterization of wild-type enzyme and mutants at Gln11. Protein Eng. 1995;8:261–273. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leland PA, Schultz LW, Kim BM, Raines RT. Ribonuclease A variants with potent cytotoxic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10407–10412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parsell DA, Sauer RT. The structural stability of a protein is an important determinant of its proteolytic susceptibility in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7590–7595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bretscher LE, Abel RL, Raines RT. A ribonuclease A variant with low catalytic activity but high cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9893–9896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.9893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fawell S, et al. Tat-mediated delivery of heterologous proteins into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:664–668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haigis MC, Kurten EL, Abel RL, Raines RT. KFERQ sequence in ribonuclease A-mediated cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11576–11581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leland PA, Staniszewski KE, Kim BM, Raines RT. Endowing human pancreatic ribonuclease with toxicity for cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43095–43102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mikulski SM, et al. Phase II trial of a single weekly intravenous does of ranpirnase in patients with unresectable malignant mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:274–281. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westling J, et al. Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, and P. malariae: A comparison of the active site properties of plasmepsins cloned and expressed from three different species of the malaria parasite. Exp Parasitol. 1997;87:185–193. doi: 10.1006/expr.1997.4225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wlodawer A, Anders LA, Sjölin L, Gilliland GL. Structure of phosphate-free ribonuclease A refined at 1.26 Å. Biochemistry. 1988;27:2705–2717. doi: 10.1021/bi00408a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill J, et al. High level expression and characterisation of Plasmepsin II, an aspartic proteinase from Plasmodium falciparum. FEBS Lett. 1994;352:155–158. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00940-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelemen BR, et al. Hypersensitive substrate for ribonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3696–3701. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.18.3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klink TA, Woycechowsky KJ, Taylor KM, Raines RT. Contribution of disulfide bonds to the conformational stability and catalytic activity of ribonuclease A. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:566–572. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Westling J, et al. Active site specificity of plasmepsin II. Protein Sci. 1999;8:2001–2009. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.10.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]