Abstract

Circadian clocks coordinate behavioral and physiological processes with daily light-dark cycles by driving rhythmic transcription of thousands of genes. Whereas the master clock in the brain is set by light, pacemakers in peripheral organs, such as the liver, are reset by food availability, although the setting, or “entrainment,” mechanisms remain mysterious. Studying mouse fibroblasts, we demonstrated that the nutrient-responsive adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylates and destabilizes the clock component cryptochrome 1 (CRY1). In mouse livers, AMPK activity and nuclear localization were rhythmic and inversely correlated with CRY1 nuclear protein abundance. Stimulation of AMPK destabilized cryptochromes and altered circadian rhythms, and mice in which the AMPK pathway was genetically disrupted showed alterations in peripheral clocks. Thus, phosphorylation by AMPK enables cryptochrome to transduce nutrient signals to circadian clocks in mammalian peripheral organs.

The mammalian hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) acts as a master pacemaker, aligning behavioral and physiological rhythms to light-dark cycles (1). Initially, the SCN was thought to be the only site of self-sustaining molecular pacemakers in mammals, but subsequent reports have shown such clocks to be ubiquitous (2, 3). Unlike those in the SCN, clocks in non–light-sensitive organs are entrained by daily feeding (2, 4, 5), which theoretically allows peripheral tissues to anticipate food consumption and to optimize the timing of metabolic processes. Although nuclear receptors and other pathways have been suggested to provide input (6–8), the biochemical basis for non–light-dependent clock entrainment remains unclear.

The adenosine monophosphate (AMP)–activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a central mediator of metabolic signals (9). Nutrient-regulated diurnal phosphorylation of AMPK substrates in rat livers (10) makes AMPK an attractive candidate contributor to peripheral clock entrainment. AMPK is a heterotrimeric protein kinase consisting of a catalytic (α) subunit and two regulatory (β, γ) subunits. Activation of AMPK by liver kinase B1 (LKB1)–mediated (11) or calcium-calmodulin–dependent protein kinase kinase β (CAMKKβ)–mediated (12) phosphorylation is increased in the presence of high ratios of AMP to ATP (adenosine triphosphate) or elevated intracellular calcium, respectively. Biochemical and bioinformatic studies have established the optimal amino acid sequence context in which phosphorylation by AMPK is likely (13, 14), which has facilitated prediction of novel substrates.

Mammalian circadian clocks require alternating actions of activators and repressors of transcription (15). The transcriptional regulators BMAL1 (brain and muscle ARNT-like protein 1) and CLOCK (circadian locomotor output cycles kaput) activate expression of many transcripts including the period (Per1, Per2, and Per3) and cryptochrome (Cry1 and Cry2) genes, whose protein products inhibit CLOCK and BMAL1, which results in rhythmic expression. Posttranslational modification is required for resetting the clock mechanism (15), including ubiquitination of cryptochromes by F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 3 (FBXL3) (16), which leads to their subsequent degradation.

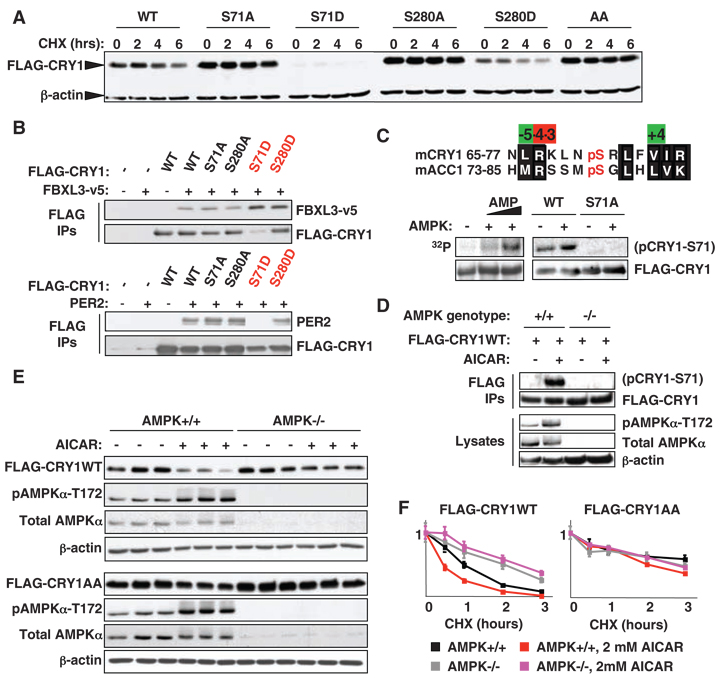

To explore the role of posttranslational modifications in nutrient-dependent signaling to mammalian peripheral clocks, we used mass spectrometry and bioinformatics to identify likely sites of regulated phosphorylation in mouse CRY1 (fig. S1, A to C). Preliminary biochemical characterization of several observed and predicted sites suggested that modification of serine 71 (S71) and, to a lesser extent, serine 280 (S280) alters the stability of CRY1, and the other mutants examined had less or no effect on stability (fig. S1) (17). Both CRY1 S71 and S280 conform well to the optimal sequence phosphorylated by AMPK (fig. S2).Mutation of either S71 or S280 to a nonphosphorylatable amino acid (alanine) was sufficient to stabilize CRY1, whereas mutation of either S71 or S280 to a phosphomimetic amino acid (aspartic acid) was sufficient to destabilize CRY1 (Fig. 1A). Mutation of S71, which is conserved in all non–light-sensitive insect cryptochromes (6) and higher organisms (fig. S2), to either alanine or to aspartic acid, had a stronger effect than the analogous mutation of S280 (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Phosphorylation of S71 or S280 by AMPK destabilizes CRY1. (A) Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells expressing WT or mutant FLAG-CRY1 were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) as indicated. AA denotes CRY1 with both S71A and S280A mutations. (B) FBXL3-v5 and PER2 bound to FLAG-CRY1 were detected by immunoblot (IB) following immunoprecipitation (IP) from HEK 293 cells. (C) (Top) Alignment of the regions surrounding mouse (m) CRY1-S71 and ACC1-S79. (Bottom) In vitro kinase assays using FLAG-CRY1 purified from HEK 293 cells and purified AMPK (6). Phosphorylated CRY1 was detected by radiography (left) or IB using an antibody against phosphoACC1-S79 (right). (D) Phosphorylation of stably expressed FLAG-CRY1 by endogenous AMPK was detected by IB following IP from MG132-treated MEFs. (E) MEFs were treated with vehicle (−) or 2 mMAICAR (+) for 2 hours. (F) MEFs were treated with CHX ± 2 mM AICAR as indicated. CRY1 was detected by IP and IB for the FLAG epitope in (C to F). Graphs in (F) represent the means ± SD of three quantified IB samples per condition.

To determine whether the instability of CRY1 phosphomimetic mutants reflects altered interaction with known binding partners, we expressed FLAG-tagged wild-type (WT) or mutant CRY1 with v5-tagged FBXL3 or untagged PER2 and analyzed their interactions by immunoprecipitation of the FLAG-tagged CRY1, followed by immunoblot. Mutation of S71 to aspartic acid (S71D) greatly increased the affinity ofCRY1 for FBXL3, in concert with destabilizing CRY1 in the context of FBXL3 overexpression (Fig. 1B and fig. S3A), which suggested that phosphorylation of S71 increases the interaction betweenCRY1 and FBXL3. CRY1 harboring an S280D mutation coprecipitated double the amount of FBXL3 relative to WT CRY1. In contrast, CRY1-S71D lost the ability to bind PER2, whereas CRY1-S280D retained PER2 binding, as did the other mutants examined (Fig. 1B and fig. S3B). Thus, CRY1-S71D exhibited decreased binding to PER2 and increased binding to FBXL3, each of which is expected to destabilize CRY1 and which together likely account for its instability.

Using purified components, we found that AMPK directly phosphorylates CRY1 in vitro (Fig. 1C). To examine CRY1 S71 phosphorylation in vivo, we tested several phospho-specific antibodies for the ability to recognize WT but not S71A CRY1 phosphorylated by AMPK. We found that an antibody against acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase 1 (ACC1) phosphorylated on S79 indeed specifically recognized CRY1 phosphorylated on S71 (Fig. 1C). To determine whether endogenous AMPK mediates this phosphorylation, we used retroviruses to stably express FLAG-CRY1 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) that were genetically wild-type (WT) or null (ampkα1−/−;ampkα2−/−) for the catalytic subunits of AMPK (AMPK−/−).We detected phosphorylation of purified FLAG-CRY1 after treatment with the AMPK agonist aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) only in the WT cells, which demonstrated that in vivo phosphorylation of S71 is mediated by AMPK (Fig. 1D).

To investigate whether AMPK regulates cryptochrome stability, we generated WT and AMPK−/− cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged WT or doubly nonphosphorylatable (AA) CRY1 and found that WT, but not AA, CRY1 is degraded after treatment with AICAR (Fig. 1E and figs. S3C and S4). The regulation of CRY1 stability by AMPK phosphorylation of S71 and S280 was confirmed by subjecting these cells to a time course of cyclo-heximide treatment in the presence or absence of AICAR (Fig. 1F and fig. S5). AICAR treatment of WT cells reduced the half-life of WT CRY1 from 45 min to less than 30 min, whereas the half-life of AA CRY1 exceeded 2 hours under all conditions. Genetic loss of AMPK stabilized WT CRY1 but did not affect the stability of the non-phosphorylatable AA mutant, which was more stable than WT CRY1 regardless of the presence or absence of AMPK.

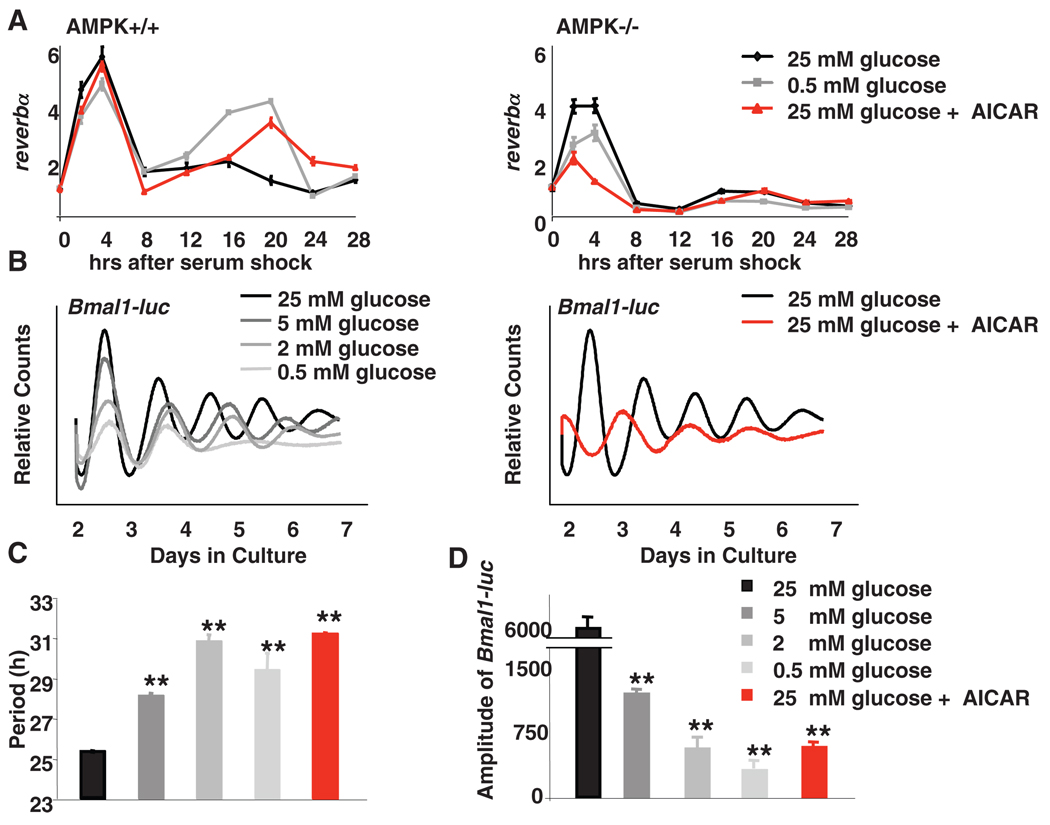

Given the importance of feeding-derived signals for circadian clock resetting, the regulation of AMPK by glucose availability, and the destabilization of cryptochromes by AMPK, we examined the effects of AMPK expression and glucose availability on circadian rhythmicity in fibroblasts (6). When WT fibroblasts were cultured in medium containing either limiting glucose or AICAR, the amplitude of circadian expression of REV-ERBalpha (reverbα, also known as nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 1, Nr1d1) and D-site albumin-binding protein (dbp) was enhanced (Fig. 2A and fig. S6), consistent with a model in which glucose deprivation activates AMPK and reduces CRY1 stability, leading to de-repression of CLOCK:BMAL1 targets. Notably, neither glucose deprivation nor AICAR affected the expression of reverbα and dbp in MEFs lacking either LKB1 or AMPK(Fig. 2A and fig. S6, B to D),which indicates that these effects of glucose limitation are mediated by AMPK, although other glucose-dependent signaling pathways may also affect circadian clocks (18).

Fig. 2.

Disruption of AMPK signaling alters circadian rhythms in MEFs. (A) MEFs were synchronized by serum shock and transferred to media containing glucose and AICAR as indicated. Quantitative PCR (QPCR) was performed by using cDNA from samples collected at the indicated times. Data are means ± SD of a representative experiment analyzed in triplicate. (B) Typical results of continuous monitoring of luciferase activity from U2OS cells stably expressing Bmal1-luciferase. (C and D) Quantification of the circadian period (C) and amplitude (D) of Bmal1-driven luciferase from experiments performed as described in (B). Data in (C) and (D) are means ± SD for four samples per condition. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated a significant difference between categories. **P < 0.01 versus samples cultured in 25 mM glucose.

The Bmal1 promoter is repressed by REV-ERBα. Therefore, we examined the effects of reducing glucose availability on circadian rhythms using fibroblasts stably expressing luciferase under the control of a Bmal1 promoter. In a standard (high-glucose) medium, Bmal1-luciferase exhibited a high-amplitude circadian rhythm with a period of 25.3 hours (Fig. 2, B and C). Decreasing the amount of glucose in the medium increased the circadian period up to 30.7 hours and decreased the amplitude of Bmal1-luciferase expression (Fig. 2D). AICAR treatment had similar effects on circadian period and amplitude (Fig. 2, B to D), which reinforced the idea that the circadian effects of glucose limitation are mediated by AMPK. We also found evidence to suggest that AMPK activation shifts the phase of entrainment in mouse fibroblasts and mouse livers (6) (figs. S7 and S8).

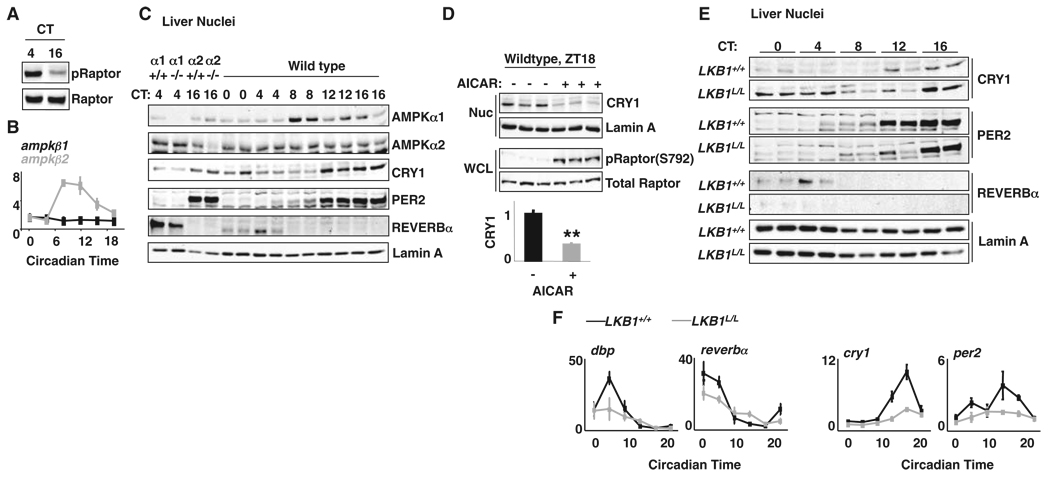

If AMPK-directed cryptochrome phosphorylation regulates the phase of peripheral clocks, the activity, expression, and/or localization of AMPK must be subject to diurnal regulation. Studying mouse liver, we found that the phosphorylation of AMPK substrates Raptor-Ser792 and ACC1-Ser79 was reproducibly higher during the subjective day than at night (Fig. 3A and fig. S9). We also observed circadian expression of the mRNA encoding the regulatory AMPKβ2 subunit (Fig. 3B and fig. S10). Because the subunit composition of AMPK complexes regulates its localization (19), oscillating AMPKβ2 could diurnally regulate the nuclear import of AMPK. Indeed, AMPKα1 exhibited a robust circadian rhythm of nuclear localization (Fig. 3C and fig. S11A), peaking synchronously with ampkβ2 expression. The time of peak AMPKα1 nuclear localization coincides with minimum nuclear CRY1 (Fig. 3C), which suggests that rhythmic nuclear import of AMPK may contribute to the AMPK-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of cryptochromes.

Fig. 3.

AMPK is rhythmic and regulates CRY1 stability in mouse livers. (A) IB for phospho-Raptor-S792 (pRaptor) and Raptor in mouse liver lysates. CT, circadian time. (B) QPCR analysis of cDNA prepared from mouse livers. (C) IB for AMPKα1, AMPKα2, CRY1, PER2, REV-ERBα, and Lamin A in liver nuclei from two mice at each indicated circadian time (CT). WT (α1+/+ or α2+/+) and ampkα1−/− (α1−/−) or ampkα2−/− (α2−/−) samples demonstrate antibody specificity. (D) Mice were injected with saline or AICAR, and liver samples were collected 1 hour later at zeitgeber time (hours after lights on, ZT) ZT18. (Top) CRY1 in liver nuclei (Nuc) and phospho-Raptor in whole-cell lysates (WCL). (Bottom) Means ± SD of the relative amount of CRY1. **P<0.01 versus saline-treated samples. (E) CRY1, PER2, REV-ERBα, and Lamin A detected by IB in liver nuclei from LKB1+/+ and LKB1L/L mice. (F) QPCR for dbp, reverbα, cry1, and per2 in mouse liver. All transcripts were normalized to u36b4.

To determine whether AMPK affects circadian clocks in vivo, we measured CRY1 protein in liver nuclei from mice injected with either saline or AICAR during the early nighttime hours. AMPK activation reduced endogenous CRY1 by an average of 67% in vivo (Fig. 3D). To specifically examine AMPK’s role in the liver, we studied circadian proteins and transcripts in the livers of control mice (LKB1+/+) or littermates harboring loss of lkb1 in hepatocytes (LKB1L/L). Liver-specific deletion of lkb1 abolished AMPK activation in that organ (20) and significantly increased the amount of CRY1 present in liver nuclei across the circadian cycle, particularly during the day-time hours when AMPK was most active in control mice (Fig. 3E and fig. S11B). This increase was associated with decreased REV-ERBα and decreased amplitude of circadian transcripts throughout the circadian cycle (Fig. 3F). Thus, loss of AMPK signaling in vivo stabilizes cryptochromes and disrupts circadian rhythms, consistent with the hypothesis that this pathway contributes to the metabolic control of light-independent peripheral circadian clocks.

In summary, we provide evidence that mammalian cryptochromes, which evolved from blue light photoreceptors, have been repurposed by AMPK to act as chemical energy sensors and can transduce nutrient signals to clocks (fig. S12). Although our data suggest that AMPK phosphorylation of cryptochromes contributes to metabolic entrainment of peripheral clocks, we expect that the communication of nutritional status to clocks is complex and that additional pathways contribute in vivo (6). Given that AMPK is a central regulator of metabolic processes, the rhythmic regulation of AMPK has implications for the circadian regulation of metabolism. Genetic alteration of circadian clocks either ubiquitously (21, 22) or in a tissue-specific manner (23, 24) elicits dramatic changes in feeding behavior, body weight, running endurance, and glucose homeostasis, each of which is also altered by manipulation of AMPK (25–30). The abilities of AMPK to mediate circadian regulation and of CRY1 to function as a chemical energy sensor suggest a close relation between metabolic and circadian rhythms.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Information about obtaining reprints of this article or about obtaining permission to reproduce this article in whole or in part can be found at: http://www.sciencemag.org/about/permissions.dtl

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/326/5951/437/DC1

Materials and Methods

SOM Text

Figs. S1 to S9

Tables S1 to S3

References

References and Notes

- 1.Stephan FK, Zucker I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1972;69:1583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.6.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damiola F, et al. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2950. doi: 10.1101/gad.183500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamazaki S, et al. Science. 2000;288:682. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stokkan KA, Yamazaki S, Tei H, Sakaki Y, Menaker M. Science. 2001;291:490. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schibler U, Ripperger J, Brown SA. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2003;18:250. doi: 10.1177/0748730403018003007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Materials and methods and additional text and figures are available as supporting information on Science Online.

- 7.Yang X, et al. Cell. 2006;126:801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang X, Lamia KA, Evans RM. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2007;72:387. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardie DG. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:774. doi: 10.1038/nrm2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies SP, Carling D, Munday MR, Hardie DG. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;203:615. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardie DG. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:5479. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witters LA, Kemp BE, Means AR. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:13. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott JW, Norman DG, Hawley SA, Kontogiannis L, Hardie DG. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:309. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gwinn DM, et al. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:214. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green CB, Takahashi JS, Bass J. Cell. 2008;134:728. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gatfield D, Schibler U. Science. 2007;316:1135. doi: 10.1126/science.1144165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Single-letter abbreviations for the amino acid residues are as follows: A, Ala; C, Cys; D, Asp; E, Glu; F, Phe; G, Gly; H, His; I, Ile; K, Lys; L, Leu; M, Met; N, Asn; P, Pro; Q, Gln; R, Arg; S, Ser; T, Thr; V, Val; W, Trp; and Y, Tyr.

- 18.Hirota T, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:44244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki A, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:4317. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02222-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw RJ, et al. Science. 2005;310:1642. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudic RD, et al. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turek FW, et al. Science. 2005;308:1043. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDearmon EL, et al. Science. 2006;314:1304. doi: 10.1126/science.1132430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamia KA, Storch KF, Weitz CJ. Proc. Natl. Acad.Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:15172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minokoshi Y, et al. Nature. 2004;428:569. doi: 10.1038/nature02440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersson U, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foretz M, et al. Diabetes. 2005;54:1331. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villena JA, et al. Diabetes. 2004;53:2242. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viollet B, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:91. doi: 10.1172/JCI16567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narkar VA, et al. Cell. 2008;134:405. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.We thank J. Asara and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Mass Spectrometry facility for phosphopeptide detection; A. Sancar for mouse strains; C. Weitz and S. Reppert for clock gene expression plasmids; and M. Downes and R. Yu for critical reading of the manuscript. Supported by NIH grants DK057978 and DK062434 (R.M.E.), CA104838 (C.B.T.), DK080425 (R.J.S.), EY016807 (S.P.), and T32-HL07439-27 (U.M.S.) and by the Pew Charitable Trust (S.P.). K.A.L. is a Merck fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation. Several of the authors (K.A.L., U.M.S., L.D., S.P., R.J.S., C.B.T., and R.M.E.) have filed preliminary patent applications related to this work.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.