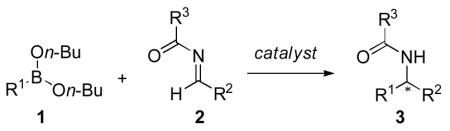

Chiral biphenols are privileged catalyst structures[1] utilized in a wide range of reactions that continues to expand.[2] The accessibility of the chiral framework and structural variants is a key aspect of the utility this class exhibits in asymmetric catalysis.[3] More recently, chiral biphenol catalysts have proven to be effective catalysts for asymmetric conjugate addition reactions, the asymmetric allylboration of ketones[4] and acyl imines,[5] as well as the asymmetric three component Petasis condensation reaction of secondary amines, glyoxylates, and alkenyl boronates.[6] An important mechanistic facet in each of the reactions is exchange of one of the boronate alkoxy groups with the biphenol to create a more reactive boronate species.[4,7] We sought to expand the repertoire of boronate nucleophiles that will react with acyl imines using chiral biphenol catalysts. Our approach towards the rapid identification of the optimal catalyst for each nucleophilic addition reaction was to screen a collection of chiral biphenols.[8] Screening chiral catalyst collections has proven to be an effective method for catalyst identification[9] and reaction discovery.[10] In this approach the efficient identification of the optimal catalyst is maximized and unexpected results or patterns in reactivity can be rapidly elucidated. Herein we describe the identification and application of chiral biphenol catalysts for the addition of aryl, vinyl and alkynyl boronates to acyl imines via a catalyst screening approach.

|

(1) |

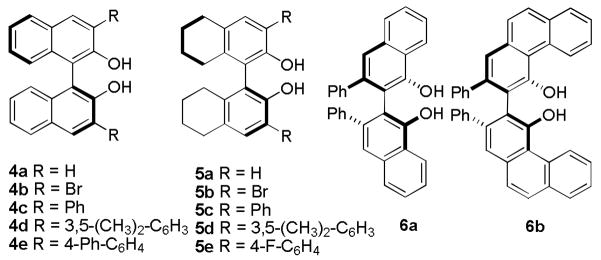

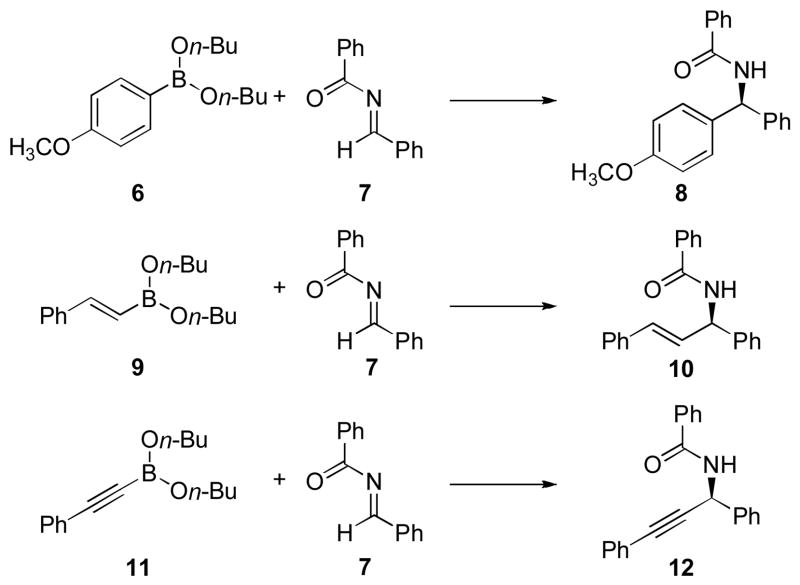

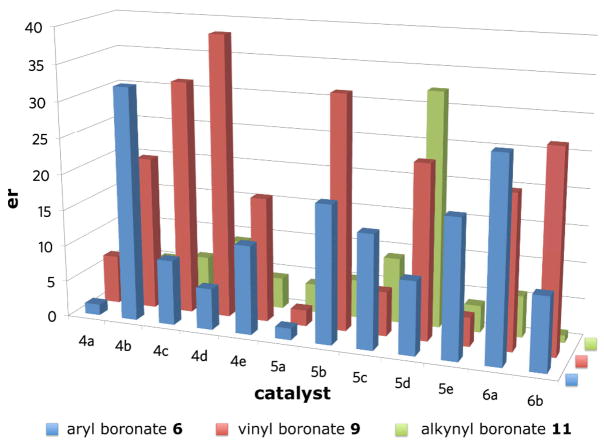

Our investigations began with the identification of reaction conditions that promote the addition of aryl, vinyl and alkynyl boronates to acyl imines (eq 1). For each boronate, the nucleophilic addition proceeded only by the inclusion of a biphenol catalyst, < 5% yield was obtained in the absence of any biphenol catalyst. In developing a general protocol for a catalyst screening process, the di-n-butyl boronate was determined to be optimal due to its hydrolytic stability. Good yields could be obtained for each of the nucleophiles using BINOL as the catalyst. The next step was to perform a screen using a collection of chiral biphenol catalysts in each of the boronate addition reactions. Twelve chiral biphenols were screened as catalysts (Figure 1) in the presence of benzoyl imine 7 and the aryl, alkenyl, and alkynyl boronates 6, 9, and 11 respectively (Scheme 1). Comparing the enantiomeric ratio of each nucleophile as a function of the catalyst employed illustrated notable trends (Figure 2). The use of catalyst 4b with aryl nucleophile 6 yielded the desired diaryl amide with excellent selectivity. Whereas use of catalyst 4b in the presence of alkenyl boronate 9 or alkynyl nucleophile 11 afforded the corresponding product in lower selectivities. In each case, a different BINOL catalyst structure proved to be the most effective for each boronate nucleophile. However, a catalyst was identified that afforded the addition product in >95:5 er for each of the boronate nucleophiles investigated.

Figure 1.

Chiral Biphenols

Scheme 1.

Nucleophilic Boronate Reactions Promoted by Chiral Biphenols.

Figure 2.

Catalyst Screen for Enantioselectivity

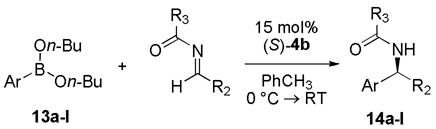

The scope of the reaction was investigated for each of the boronate nucleophiles. In general, the optimal catalyst identified in the screening experiments, 4b, proved effective for all of the aryl boronates evaluated in the reaction. Aryl boronates (entries 1 – 5, Table 1), aryl (entries 6 – 7) and aliphatic (entry 8) imines, as well as acyl imine substituents (entries 9 – 11) were found to be effective in the biphenol-catalyzed addition reaction each affording the corresponding amide in good yields (>70% isolated yield) and enantioselectivities (>95:5 er).

Table 1.

Asymmetric Arylboration of Acyl Iminesa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Ar | R2 | R3 | yieldb | erc |

| 1 | 4-CH3O-Ph | Ph | Ph | 80 | 98:2 |

| 2 | 4-CH3-Ph | Ph | Ph | 82 | 98:2 |

| 3 | 3,4-OCH2O-Ph | Ph | Ph | 91 | 96:4 |

| 4 | 4-Br-Ph | Ph | Ph | 95 | 99:1 |

| 5 | 2-Br-Ph | Ph | Ph | 72 | 97:3 |

| 6 | 4-Cl-Ph | Ph | Ph | 98 | 98:2 |

| 7 | 4-CH3O-Ph | 4-Br-Ph | Ph | 80 | 98.5:1.5 |

| 8 | 4-CH3O-Ph | 2-C4H3S | Ph | 89 | 96:4 |

| 9 | 4-CH3O-Ph | c-C6H11 | Ph | 70 | 95.5:4.5 |

| 10 | 4-CH3O-Ph | Ph | (E)-PhCH=CH | 87 | 98:2 |

| 11 | 4-CH3O-Ph | Ph | 83 | 98:2 | |

| 12 | 4-CH3O-Ph | Ph | c-C6H11 | 71 | 97.5:2.5 |

Reactions were run with 0.0375 mmol catalyst 4b, 0.25 mmol arylboronate, and 0.25 mmol acyl imine in 2.5 mL toluene for 18h at 0 °C → RT.

Isolated yields.

Determined by chiral HPLC.

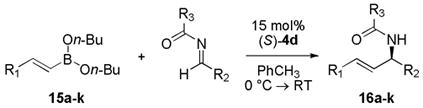

Vinyl boronates (entries 1–5, Table 2) also afforded the corresponding allylic amide products in high yield and selectivity. Catalyst 4d also promoted the vinyl addition to a series of substituted aryl, heteroaryl, and alkyl imines (entries 6–8) as well as substituted acyl imines (entries 9–11) in good yields and selectivities (>70% yield, >95:5 er).

Table 2.

Asymmetric Vinylboration of Acyl Iminesa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | yieldb | erc |

| 1 | Ph | Ph | Ph | 85 | 97.5:2.5 |

| 2 | 2-C4H3S | Ph | Ph | 88 | 99:1 |

| 3 | 3-F-Ph | Ph | Ph | 82 | 96.5:3.5 |

| 4 | 4-CH3O-Ph | Ph | Ph | 83 | 96:4 |

| 5 | c-C6H11 | Ph | Ph | 75 | 98:2 |

| 6 | Ph | 4-Br-Ph | Ph | 80 | 95.5:4.5 |

| 7 | Ph | 2-C4H3S | Ph | 91 | 95:5 |

| 8 | Ph | c-C6H11 | Ph | 74 | 95.5:4.5 |

| 9 | Ph | Ph | (E)-CH=CHPh | 87 | 98.5:1.5 |

| 10 | Ph | Ph | 83 | 97.5:2.5 | |

| 11 | Ph | Ph | c-C6H11 | 82 | 97.5:2.5 |

Reactions were set up with 0.0375 mmol catalyst 4d, 0.25 mmol alkenyl boronate, and 0.25 mmol acyl imine in 2.5 mL toluene for 18h at 0 °C → RT.

Isolated yields.

Determined by chiral HPLC.

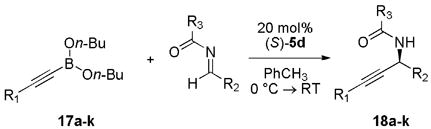

Similarly, substituted alkynyl boronates (entries 1–6, Table 3) also proved successful as the desired propargyl amides were isolated in high yield and selectivity. Aryl, heteroayl, aliphatic (entries 7–9) as well as acyl substituted imines (entries 10, 11) produced the desired products in good yields and slectivities using catalyst 5d.

Table 3.

Asymmetric Alkynylboration of Acyl Iminesa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | yieldb | erc |

| 1 | Ph | Ph | Ph | 99 | 96:4 |

| 2 | 4-F-Ph | Ph | Ph | 76 | 93:7 |

| 3 | 3-C4H3S | Ph | Ph | 72 | 94:6 |

| 4 | n-hexyl | Ph | Ph | 90 | 92:8 |

| 5 | Ph(CH2)2 | Ph | Ph | 71 | 97:3 |

| 6 | i-propenyl | Ph | Ph | 80 | 96:4 |

| 7 | Ph | 4-CH3O-Ph | Ph | 99 | 96:4 |

| 8 | Ph | 4-Br-Ph | Ph | 62 | 93:7 |

| 9d | Ph | 2-C3H4S | Ph | 80 | 97:3 |

| 10 | Ph | Ph | 4-Br-Ph | 70 | 97:3 |

| 11 | Ph | Ph | 4-OCH3-Ph | 69 | 95:5 |

Reactions were set up with 0.023 mmol catalyst 4d, 0.115 mmol alkynyl boronate, 0.115 mmol and acyl imine in 1 mL toluene for 36 h at 0 °C → RT.

Isolated yields.

Determined by chiral HPLC.

Reaction run with 3 equiv alkynyl boronate

We continued our studies by characterizing the boronate species under the catalytic reaction conditions. Electron spray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) experiments were conducted at room temperature of reaction mixtures containing BINOL-derived diols and boronates in the presence and absence of benzoyl imine 7. ESI-MS is an effective process for the characterization of intermediates that are otherwise difficult to characterize via purification.[11,5] The mixture of BINOL 4b and boronate 9 was analyzed using a MicroMass ZQ 2000 mass spectrometer in positive electrospray ionization mode. Under these conditions the mass of a boronate resulting from exchange of one of the alkoxy groups with BINOL 4b was observed, without any detectable formation of the corresponding cyclic boronate, consistent with previous results obtained for the allylboration reaction. Furthermore, use of the chiral cyclic boronate derived from BINOL 4b and the boronate 9 resulted in low yield (< 20%) and low enantioselectivity (55:45 er) when reacted with imine 7 under the same reaction conditions. Although computational studies have implicated the formation of cyclic boronates under catalytic conditions,[12] the experimental results obtained to date demonstrate an acyclic boronate complex under catalytic conditions. The stereochemical model developed for the reaction of the boronate complex with acyl imines is consistent with the observed stereoinduction (Figure 3). The observed enantiofacial selectivity is the result of catalyst coordination to the Z-conformer of the acyl imine. The more reactive Z-conformer has been proposed by Corey[13] and others[14] in reactions involving imines due to steric interactions that arise from the metal reagent and the substituents of the imine. The hydrogen-bonding character of the biphenol activates the acyl imine towards nucleophilic attack and orients the boronate complex towards re enantiofacial selectivity in the addition reaction.[5]

Figure 3.

Proposed Transition State for Asymmetric Boronate Addition to Acyl Imines

Lastly, the methodology was utilized in the synthesis of the known antihistamine levocetirizine (Xyzal®). The construction of amine (R)-19 is a key step in the synthesis.[15,16,17] Our approach to this desired intermediate used (R)-4b as the catalyst and aryl boronate 13f to afford diaryl amide 14f in 98% isolated yield and 98:2 er. Deprotection of the amide was accomplished using a method recently described by Prati[18] resulting in the production of free amine 19 in 80% yield with complete retention of stereochemistry constituting a formal synthesis of Xyzal® 20.[19]

In summary, we have applied a chiral biphenol catalyst screening protocol for the rapid identification of enantioselective catalytic reactions. The approach successfully identified a unique catalyst that promoted the reaction enantioselectively for each of the boronates investigated. Furthermore, the optimal catalyst identified proved general for each class of boronate nucleophiles. Mechanistic studies demonstrate exchange between the boronate and catalyst giving rise to the active nucleophilic boronate reagent. The method was utilized in the enantioselective synthesis of the antihistamine Xyzal®. Continued investigations include use of the screening approach toward expansion of the scope and utility of the reaction, as well as detailed mechanistic studies.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of key intermediate in the formal synthesis of Xyzal®

Footnotes

This research was supported by the NIH (R01 GM078240 and P50 GM067041) and Amgen, Inc.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.Yoon TP, Jacobsen EN. Science. 2003;299:1691–1693. doi: 10.1126/science.1083622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Brunel MJ. Chem Rev. 2005;105:857–897. doi: 10.1021/cr040079g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Brunel MJ. Chem Rev. 2007;107:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y, Yekta S, Ydin AK. Chem Rev. 2003;103:3155–3211. doi: 10.1021/cr020025b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lou S, Moquist PN, Schaus SE. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12660–12662. doi: 10.1021/ja0651308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lou S, Moquist PN, Schaus SE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15398–15404. doi: 10.1021/ja075204v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lou S, Schaus SE. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6922–6923. doi: 10.1021/ja8018934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Chong MJ, Wu TR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3244–3245. doi: 10.1021/ja043001q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Goodman JM, Pellegrinet SC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;128:3116–3117. doi: 10.1021/ja056727a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Cook GR, Kargbo R, Maity B. Org Lett. 2005;7:2767–2770. doi: 10.1021/ol051160o. Jones. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shepperson IR. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3846–3847. doi: 10.1021/ja070742t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Francis MB, Finner NS, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8983–8984. [Google Scholar]; b) Jacobsen EN, Sigman MS. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:4901. [Google Scholar]; c) Porte AM, Reibenspies J, Burgess K. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:9180–9187. [Google Scholar]; d) Stambuli JP, Stauffer SR, Shaughnessy KH, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2677–2678. doi: 10.1021/ja0058435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Hoveyda AH, Murphy KE. In: Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis. Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto H, editors. Vol. 39. Springer; New York: 2004. pp. 171–189. [Google Scholar]; f) Ireland T, Fontanet F, Tchao G. Tet Lett. 2004;45:4383–4387. [Google Scholar]; g) Lee JY, Miller JJ, Hamilton SS, Sigman MS. Org Lett. 2005;7:1837–1840. doi: 10.1021/ol050528e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Taylor SJ, Morken JP. Science. 1998;280:267–271. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Copeland GT, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6496–6502. doi: 10.1021/ja0108584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ding K. Chem Comm. 2008:909–921. doi: 10.1039/b710668h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Colton R, Agostino AD, Traeger JC. Mass Spectrom Rev. 1995;14:79–106. [Google Scholar]; b) Cole RB. Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Wiley; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]; c) Henderson W, Nicholson BK, McCaffrey L. J Polyhedron. 1998;17:4291–4313. [Google Scholar]; d) Cech NB, Enke CG. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2001;20:362–387. doi: 10.1002/mas.10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Pellegrinet SC, Goodman JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3116–3117. doi: 10.1021/ja056727a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Raton RS, Goodman JM, Pellegrinet SC. J Org Chem. 2008;73:5078–5089. doi: 10.1021/jo8007463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corey EJ, Decicco CP, Newbold RC. Tet Lett. 1991;32:5287–5290. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Roush WR. Uncatalyzed Additions of Nucleophilic Alkenes to C=X. In: Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Vol. 2. Gamon; New York: 1991. p. 1. [Google Scholar]; b) Alvaro G, Boga C, Savoia D, Umano-Ronchi A. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1996:875–882. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opalka CJ, D’Ambra TE, Faccone JJ, Bodson G, Cossement E. Synthesis. 1995:766–768. [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Corey EJ, Helal CJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:4837–4840. [Google Scholar]; b) Katritzky AR, Xie L, Zhang G, Griggith M, Watson K, Kiely JS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:7011–7014. [Google Scholar]; c) Hermanns N, Dahmen S, Bolm C, Brase S. Angew Chem. 2002;114:3844–3846. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021004)41:19<3692::AID-ANIE3692>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hermanns N, Dahmen S, Bolm C, Brase S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:3692–3694. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021004)41:19<3692::AID-ANIE3692>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Plobeck N, Powell D. Tetrahedron: Asym. 2002;13:303–310. [Google Scholar]; e) Han Z, Krishnamurthy D, Grover P, Fang QK, Pflum DA, Senanayake CH. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:4195–4197. [Google Scholar]; f) Aggarwal VK, Fang GY, Schmidt AT. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1642–1643. doi: 10.1021/ja043632k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Tokunaga N, Otomaru Y, Okamoto K, Ueyama K, Shintani R, Hayashi TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13584–13585. doi: 10.1021/ja044790e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hayashi T, Kawai M, Tokunaga N. Angew Chem. 2004;116:6251–6254. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hayashi T, Kawai M, Tokunaga N. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:6125–6128. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bolshan Y, Batey RA. Org Lett. 2005;7:1481–1484. doi: 10.1021/ol050014f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Weix DJ, Shi Y, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1092–1093. doi: 10.1021/ja044003d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Jagt RBC, Toullec PY, Geerdink D, de Vries JG, Feringa BL, Minnaard AJ. Angew Chem. 2006;118:2855–2857. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jagt RBC, Toullec PY, Geerdink D, de Vries JG, Feringa BL, Minnaard AJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2789–2791. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prati F, Spaggiari A, Blaszczak LC. Org Lett. 2004;6:3885–3888. doi: 10.1021/ol048852h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senanayake CH, Pflum DA, Krishnamurthy D, Han Z, Wald SA. Tet Lett. 2002;43:923–926. doi: 10.1021/ol026699q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.